1. Introduction

Crossflow instability (CFI) is one of the dominant instability mechanisms in a subsonic three-dimensional boundary layer over swept wings. Such CFI arises due to the inflection point in the velocity profile of the crossflow (CF) component and can have a stationary or travelling nature, depending on the receptivity process, the level of free-stream turbulence and surface roughness. In low-free-stream-turbulence environments, such as free flight conditions of commercial airliners, the stationary CFI becomes dominant, while the travelling CFI becomes dominant when the level of free-stream turbulence is high (Deyhle & Bippes Reference Deyhle and Bippes1996). The stationary CFI manifests itself as co-rotating vortices that develop in a direction closely aligned with the inviscid external streamline (Saric, Reed & White Reference Saric, Reed and White2003).

The CFI-dominated laminar–turbulent transition on a smooth swept wing (i.e. without surface irregularities or enhanced roughness) commonly occurs due to the development of type I, type II or type III secondary instabilities. Type I secondary instability, also known as the

![]() $z$

mode, originates in the outer part of the CF vortex (CFV) upwelling region, where the spanwise shear reaches its local minimum (Malik et al. Reference Malik, Li and Chang1996, Reference Malik, Li, Choudhari and Chang1999; Wassermann & Kloker Reference Wassermann and Kloker2002). Type II secondary instability (

$z$

mode, originates in the outer part of the CF vortex (CFV) upwelling region, where the spanwise shear reaches its local minimum (Malik et al. Reference Malik, Li and Chang1996, Reference Malik, Li, Choudhari and Chang1999; Wassermann & Kloker Reference Wassermann and Kloker2002). Type II secondary instability (

![]() $y$

mode) originates at the top of the CFV and away from the wall, where wall-normal shear has its local maximum (Malik et al. Reference Malik, Li and Chang1996, Reference Malik, Li, Choudhari and Chang1999; Wassermann & Kloker Reference Wassermann and Kloker2002). Lastly, the so-called type III mode describes the interaction between stationary and travelling primary CFI modes. It is located in the inner part of the upwelling region of the CFV, and coincides with the local maximum of spanwise shear (Bonfigli & Kloker Reference Bonfigli and Kloker2007).

$y$

mode) originates at the top of the CFV and away from the wall, where wall-normal shear has its local maximum (Malik et al. Reference Malik, Li and Chang1996, Reference Malik, Li, Choudhari and Chang1999; Wassermann & Kloker Reference Wassermann and Kloker2002). Lastly, the so-called type III mode describes the interaction between stationary and travelling primary CFI modes. It is located in the inner part of the upwelling region of the CFV, and coincides with the local maximum of spanwise shear (Bonfigli & Kloker Reference Bonfigli and Kloker2007).

Reducing the growth of stationary CFVs, and consequently reducing the growth of secondary instabilities to extend the laminar region through laminar flow control (LFC) techniques, has been the topic of research for several decades. Two broad and important categories of LFC strategies are upstream flow deformation (UFD) (Wassermann & Kloker Reference Wassermann and Kloker2002) and base flow modification. While UFD techniques directly target the critical instability mode, base flow modification alters the velocity profile where instabilities develop, aiming to reduce the strength of the inflectional CF velocity component in the base flow.

One of the successful UFD strategies is the use of micron-sized discrete roughness elements (DREs) positioned at a spacing smaller than the wavelength of the naturally most amplified CF mode (Reibert et al. Reference Reibert, Saric, Carrillo and Chapman1996; Saric et al. Reference Saric, Carrillo and Reibert1998b ). The effectiveness of this approach has been demonstrated in both wind-tunnel experiments (Saric et al. Reference Saric, Carrillo and Reibert1998a ; Kachanov, Borodulin & Ivanov Reference Kachanov, Borodulin and Ivanov2015) and numerical simulations (Wassermann & Kloker Reference Wassermann and Kloker2002; Rhodes et al. Reference Rhodes, Reed, Saric, Carpenter and Neale2010; Rizzetta et al. Reference Rizzetta, Visbal, Reed and Saric2010; Hosseini et al. Reference Hosseini, Tempelmann, Hanifi and Henningson2013). However, this method is highly sensitive to background roughness and to the baseline transition location (Lovig, Downs & White Reference Lovig, Downs and White2014; Saric et al. Reference Saric, West, Tufts and Reed2019). Another UFD-based approach employs spanwise-modulated plasma actuators to influence the most amplified CF mode (Dörr & Kloker Reference Dörr and Kloker2017; Serpieri, Venkata & Kotsonis Reference Serpieri, Venkata and Kotsonis2017; Shahriari, Kollert & Hanifi Reference Shahriari, Kollert and Hanifi2018). Examples of base flow modification techniques include wall suction/blowing (Messing & Kloker Reference Messing and Kloker2010) and the use of plasma actuators to induce a two-dimensional volume forcing against the local CF velocity component (Dörr & Kloker Reference Dörr and Kloker2015; Yadala et al. Reference Yadala, Hehner, Serpieri, Benard, Dörr, Kloker and Kotsonis2018), both of which have been shown to delay transition. A review of LFC techniques for CFI-dominated boundary layers can be found in Messing & Kloker (Reference Messing and Kloker2010) and Saric, Carpenter & Reed (Reference Saric, Carpenter and Reed2011).

While LFC techniques aim to delay transition, real-world surface irregularities can either hinder or enhance these efforts, depending on their interaction with CFVs. Understanding the interactions between CFVs and unavoidable surface features on real wings, such as gaps, steps, waviness and smooth humps, is therefore crucial for practical LFC applications. Such understanding helps to identify the surface features that degrade the effectiveness of LFC by advancing the onset of transition (compared with an ideal smooth design), and those that potentially delay the transition by suppressing instability growth, thereby suggesting novel LFC techniques. The following provides a brief overview of previous studies examining the interaction between CFVs and surface irregularities, and how this interaction influences instability growth and the transition to turbulence.

The interactions between CFVs and forward-facing (FFS) and backward-facing (BFS) steps have been studied extensively. Many studies have shown that both FFS and BFS enhance the growth of CFVs downstream of the step location and shift the transition location upstream compared with a scenario in which no geometrical feature is present on the surface (e.g. Tufts et al. Reference Tufts, Reed, Crawford, Duncan and Saric2017; Eppink Reference Eppink2020, Reference Eppink2022; Rius-Vidales & Kotsonis Reference Rius-Vidales and Kotsonis2020, Reference Rius-Vidales and Kotsonis2021, Reference Rius-Vidales and Kotsonis2022). Moreover, Eppink (Reference Eppink2020) and Rius-Vidales & Kotsonis (Reference Rius-Vidales and Kotsonis2022) showed that, if the height of the FFS is larger than a given threshold, the step can even trip the boundary layer, and transition occurs at the step location. This critical threshold, however, depends on the amplitude of the incoming CFVs (Eppink Reference Eppink2020; Rius-Vidales & Kotsonis Reference Rius-Vidales and Kotsonis2020). For such conditions, Rius-Vidales & Kotsonis (Reference Rius-Vidales and Kotsonis2022) showed that the laminar–turbulent transition does not occur due to the onset of classic type I/II/III secondary CFI modes. Instead, it is driven by a distinct unsteady mechanism caused by locally enhanced spanwise-modulated shears and the recirculation region in the immediate downstream vicinity of the FFS. This finding emphasises the need for a more detailed analysis of CFV breakdown in the presence of surface irregularities. Despite the general consensus that FFS have a detrimental effect on the breakdown of CFVs, Rius-Vidales & Kotsonis (Reference Rius-Vidales and Kotsonis2021) showed that swept-wing transition delay can be achieved using a FFS of sufficiently small height. Furthermore, steady-state direct numerical simulations (DNS) by Casacuberta et al. (Reference Casacuberta, Hickel, Westerbeek and Kotsonis2022) attributed the stabilising effect of FFS on the CFI to the way energy is transferred between the base flow and the primary CF perturbations. Recently, Casacuberta, Hickel & Kotsonis (Reference Casacuberta, Hickel and Kotsonis2024) showed that a reverse lift-up effect might be one of the dominant mechanisms behind the observed primary CFI stabilisation effect.

Beyond nominal geometries such as FFS and BFS, the interactions between CFVs and more general smooth surface protrusions have not been studied extensively. Cooke et al. (Reference Cooke, Mughal, Sherwin, Ashworth and Rolston2019) studied the effect of localised bumps (i.e. combination of an FFS with BFS) on both stationary and travelling CFIs. They used the linearised harmonic Navier–Stokes method for their study and showed that the localised bumps, in general, enhance the growth of CFIs. However, they showed that for small height of the bumps, travelling CFI can become more stable. Thomas et al. (Reference Thomas, Mughal, Gipon, Ashworth and Martinez-Cava2016) studied the interaction between surface waviness and CFIs, using linear parabolised stability equations and linearised Navier–Stokes equations. They showed that whether surface waviness stabilises or destabilises the CFI depends on the spatial phase of the waviness. Westerbeek & Kotsonis (Reference Westerbeek and Kotsonis2022) studied the effect of surface waviness on the growth of primary CFI using nonlinear parabolised stability equations (NPSEs). For the particular shape of waviness they considered, the results showed destabilisation of primary CFI.

Westerbeek et al. (Reference Westerbeek, Sumariva, Alberto, Michelis, Hein and Kotsonis2023) studied the interaction between a smooth surface hump (with a concave–convex–concave shape) and stationary CFI by solving linear and nonlinear harmonic Navier–Stokes equations. For specific conditions, their results showed a stabilisation of the primary CFI mode downstream of the surface hump with respect to the clean flat plate case. A local destabilisation of higher harmonics of the primary CFI mode was also observed downstream of the hump, relative to the clean configuration.

More recently, Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025) have experimentally investigated the interactions between a smooth surface hump and stationary CFVs at low and high initial amplitudes, preconditioned by discrete roughness elements close to the leading edge. In the high-amplitude case, the amplitude of the stationary CF perturbation measured at 13 % of the chord was approximately 2.6 times larger than in the low-amplitude case. In the high-amplitude case of their experiments, abrupt transition to turbulence slightly downstream of the hump was observed. However, in the low-amplitude case of the experiments, stabilisation of stationary CF perturbations occurred downstream of the hump. This stabilisation resulted in a significant transition delay of about

![]() $ 14 \,\%$

of the chord compared with the reference (i.e. without hump) case. Detailed boundary-layer flow measurements showed a change in the orientation of CFVs downstream of the hump, which they related to a possible weakening or reversal of CF velocity component due to local pressure gradient changes by the hump geometry. Moreover, they observed that a notable change in the orientation of CF perturbations contributed to the stabilisation of the primary stationary CFI mode. This led to the eventual delay of transition to turbulence through the weakening of spanwise shears which affect the development of type I secondary CFI modes.

$ 14 \,\%$

of the chord compared with the reference (i.e. without hump) case. Detailed boundary-layer flow measurements showed a change in the orientation of CFVs downstream of the hump, which they related to a possible weakening or reversal of CF velocity component due to local pressure gradient changes by the hump geometry. Moreover, they observed that a notable change in the orientation of CF perturbations contributed to the stabilisation of the primary stationary CFI mode. This led to the eventual delay of transition to turbulence through the weakening of spanwise shears which affect the development of type I secondary CFI modes.

Westerbeek, Casacuberta & Kotsonis (Reference Westerbeek, Casacuberta and Kotsonis2026) studied the linear and nonlinear interactions between stationary CFVs and a smooth hump for various amplitudes of CF perturbations, using the steady harmonic Navier–Stokes method. They observed stabilisation of CFI when the amplitude of incoming CF perturbation is low. In agreement with Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025), they showed that the tilting of CF perturbations downstream of the hump is followed by their stabilisation.

The experiments of Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025) highlight the potential of using smooth surface humps as a practical passive control device to delay laminar–turbulent transition, which merits detailed analysis and understanding of both steady and unsteady mechanisms leading to transition delay or advancement. Currently available numerical works exploring these interactions have been limited to analysis of the flow from a steady-state point of view, which shed light on some of the steady mechanisms underlying the stabilising effect of the hump. However, development of unsteady secondary CFI modes determines the eventual delay/advancement of the transition location. Consequently, through DNS, this work aims to present an in-depth analysis of both the steady and unsteady mechanisms responsible for delaying or advancing the laminar–turbulent transition when the surface of a swept wing features a smooth hump at flow conditions comparable to those of the experiments of Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025). Regarding the low-amplitude perturbation case, the key question is why and how the interaction between the hump and the CFVs leads to the stabilisation of the stationary primary CFI. The impact of this stabilisation on the evolution of secondary CFI modes and the link to transition delay is also examined. In the high-amplitude perturbation case, the main objective is to understand the mechanisms responsible for the abrupt transition downstream of the hump observed in the experiment.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 presents the flow case and computational approach. Section 3 presents the base flow modifications induced by the hump. Section 4 presents the analysis of the mechanisms of the transition delay by the hump, while § 5 presents the mechanisms of transition advancement by the hump. Finally, § 6 presents the conclusions of this work.

2. Methodology

2.1. Coordinate systems and velocity components

Figure 1(a) shows the two main coordinate systems used in this study and their corresponding velocity components. The grey and orange areas represent the swept-wing model and the surface hump which will be introduced in the next section. Specifically, a wind-tunnel-attached coordinate system is defined in the

![]() $(X,Y,Z)$

directions with

$(X,Y,Z)$

directions with

![]() $(U,V,W)$

as velocity components, respectively. A normal to the leading-edge coordinate system is defined in

$(U,V,W)$

as velocity components, respectively. A normal to the leading-edge coordinate system is defined in

![]() $(x,y,z)$

with

$(x,y,z)$

with

![]() $(u,v,w)$

as velocity components, respectively. Chordwise (

$(u,v,w)$

as velocity components, respectively. Chordwise (

![]() $u_\xi$

) and wall-normal (

$u_\xi$

) and wall-normal (

![]() $v_{\eta '}$

) velocity components in a body-fitted coordinate system

$v_{\eta '}$

) velocity components in a body-fitted coordinate system

![]() $(\xi ,\eta ',z)$

, as shown in figure 1(b), can be calculated using

$(\xi ,\eta ',z)$

, as shown in figure 1(b), can be calculated using

![]() $u$

and

$u$

and

![]() $v$

as

$v$

as

where

![]() $\theta$

is the angle between local wall-normal (

$\theta$

is the angle between local wall-normal (

![]() $\eta '$

direction) and

$\eta '$

direction) and

![]() $y$

directions, as shown in figure 1(b).

$y$

directions, as shown in figure 1(b).

Figure 1. (a) Schematic depicting the swept-wing model, showing the wind-tunnel-attached

![]() $(X,Y,Z)$

and normal-to-the-leading-edge

$(X,Y,Z)$

and normal-to-the-leading-edge

![]() $(x,y,z)$

coordinate systems. The orange shaded region indicates the hump location, and the hump’s apex at

$(x,y,z)$

coordinate systems. The orange shaded region indicates the hump location, and the hump’s apex at

![]() $x/c_x=0.15$

is marked with the solid orange line. Note that the inviscid streamline shown in the figure is representative of the reference case. (b) The modified NACA 66018 aerofoil shape with (solid black line) and without (dashed grey line) the hump. Note that (b) is drawn to scale; however, the inset is not drawn to scale for visibility. (c) Nominal (blue) and projected (orange) shape of the hump on the aerofoil surface (not to scale).

$x/c_x=0.15$

is marked with the solid orange line. Note that the inviscid streamline shown in the figure is representative of the reference case. (b) The modified NACA 66018 aerofoil shape with (solid black line) and without (dashed grey line) the hump. Note that (b) is drawn to scale; however, the inset is not drawn to scale for visibility. (c) Nominal (blue) and projected (orange) shape of the hump on the aerofoil surface (not to scale).

The total velocity magnitude field, denoted as

![]() $Q$

, is computed as

$Q$

, is computed as

An auxiliary coordinate system that is used in this work is a rotated coordinate system aligned with the local direction of the external inviscid streamline. The local deflection of the inviscid streamline can be computed as

where subscript ‘

![]() $e$

’ indicates the local values at the boundary layer edge, i.e.

$e$

’ indicates the local values at the boundary layer edge, i.e.

![]() $\delta _{99}$

. The velocity component tangent to the local inviscid streamline is denoted by

$\delta _{99}$

. The velocity component tangent to the local inviscid streamline is denoted by

![]() $U_{t}$

, and the velocity component normal to this streamline (i.e. the CF velocity component) is denoted by

$U_{t}$

, and the velocity component normal to this streamline (i.e. the CF velocity component) is denoted by

![]() $W_{\textit{cf}}$

. These velocity components are shown schematically in figure 1(a), and can be computed as

$W_{\textit{cf}}$

. These velocity components are shown schematically in figure 1(a), and can be computed as

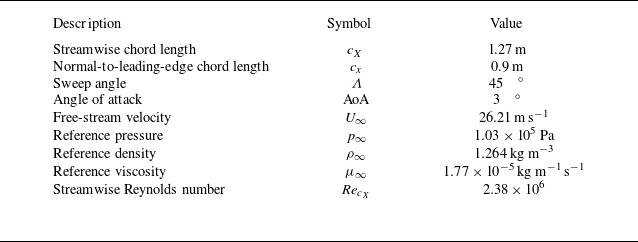

2.2. Reference flow conditions, swept wing and hump geometry

The flow reference conditions for the simulations are selected to replicate as closely as possible the experiments carried out by Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025) on the M3J swept-wing model at the Low Turbulence Tunnel (LTT) of the Delft University of Technology. A schematic of the problem set-up is shown in figure 1(a). The set-up consists of a

![]() $\varLambda = 45^\circ$

swept-wing model and features a

$\varLambda = 45^\circ$

swept-wing model and features a

![]() $3^\circ$

angle of attack (in the

$3^\circ$

angle of attack (in the

![]() $XY$

plane) with respect to the incoming flow

$XY$

plane) with respect to the incoming flow

![]() $U_\infty$

. Note that the axis of rotation is aligned with the vertical

$U_\infty$

. Note that the axis of rotation is aligned with the vertical

![]() $Z$

axis and passes through the model midspan at

$Z$

axis and passes through the model midspan at

![]() $x/c_x=0.5$

. Measurements were performed on the pressure side of the wing, which is mounted vertically in the wind tunnel. The symmetric aerofoil used in the swept-wing model is a modified version of the NACA 66018 geometry. For details, see Serpieri (Reference Serpieri2018, pp. 28−29). The swept wing has a streamwise chord length of

$x/c_x=0.5$

. Measurements were performed on the pressure side of the wing, which is mounted vertically in the wind tunnel. The symmetric aerofoil used in the swept-wing model is a modified version of the NACA 66018 geometry. For details, see Serpieri (Reference Serpieri2018, pp. 28−29). The swept wing has a streamwise chord length of

![]() $c_X=1.27$

m, and a normal-to-the-leading-edge chord length of

$c_X=1.27$

m, and a normal-to-the-leading-edge chord length of

![]() $c_x=0.9$

m (see figure 1). Note that to closely replicate the experimental conditions, the simulation parameters were adjusted to match the experimental Reynolds number,

$c_x=0.9$

m (see figure 1). Note that to closely replicate the experimental conditions, the simulation parameters were adjusted to match the experimental Reynolds number,

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{c_X,U_p} = 2.38 \times 10^6$

, based on the streamwise chord length

${\textit{Re}}_{c_X,U_p} = 2.38 \times 10^6$

, based on the streamwise chord length

![]() $c_X$

and the velocity

$c_X$

and the velocity

![]() $U_p\approx 26.1\,{\rm m\,s^{-1}}$

. The latter was measured in the experiments using a Pitot-static tube positioned just upstream of the model, and influenced by wind tunnel blockage effects. For further details, see Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025). The simulation reference values for velocity, pressure, density and viscosity are summarised in table 1, and are used to calculate the pressure

$U_p\approx 26.1\,{\rm m\,s^{-1}}$

. The latter was measured in the experiments using a Pitot-static tube positioned just upstream of the model, and influenced by wind tunnel blockage effects. For further details, see Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025). The simulation reference values for velocity, pressure, density and viscosity are summarised in table 1, and are used to calculate the pressure

![]() $(C_p)$

and skin-friction (

$(C_p)$

and skin-friction (

![]() $C_{\kern-1.5pt f}$

) coefficients.

$C_{\kern-1.5pt f}$

) coefficients.

Table 1. Flow and geometric parameters used in simulations.

The smooth surface hump is located on the wing such that its apex is at

![]() $x/c_x=0.15$

, as shown schematically in orange in figure 1(a). The shape of the aerofoil with the hump (scale 1:1) is shown in figure 1(b). The inset in figure 1(b) shows the proximity of the hump, where the solid black and dashed grey lines show the aerofoil surface with and without the hump, respectively. Note that the inset is not drawn to scale for visibility. The nominal shape of the hump before projecting it on the aerofoil is shown in figure 1(c) in blue. In the simulations, the hump is spanwise homogeneous (i.e. invariant in the

$x/c_x=0.15$

, as shown schematically in orange in figure 1(a). The shape of the aerofoil with the hump (scale 1:1) is shown in figure 1(b). The inset in figure 1(b) shows the proximity of the hump, where the solid black and dashed grey lines show the aerofoil surface with and without the hump, respectively. Note that the inset is not drawn to scale for visibility. The nominal shape of the hump before projecting it on the aerofoil is shown in figure 1(c) in blue. In the simulations, the hump is spanwise homogeneous (i.e. invariant in the

![]() $z$

direction) and has a symmetric concave–convex–concave shape, with a dimensional maximum height of

$z$

direction) and has a symmetric concave–convex–concave shape, with a dimensional maximum height of

![]() $h = 1$

mm, equivalent to a non-dimensional height of

$h = 1$

mm, equivalent to a non-dimensional height of

![]() $h/\delta ^*_{w,h} \approx 2.1$

, and a height-to-width aspect ratio of 1:50. The displacement thickness

$h/\delta ^*_{w,h} \approx 2.1$

, and a height-to-width aspect ratio of 1:50. The displacement thickness

![]() $\delta ^*_{w,h}$

is calculated from the spanwise velocity profile at the location of apex of the hump from the base flow (

$\delta ^*_{w,h}$

is calculated from the spanwise velocity profile at the location of apex of the hump from the base flow (

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_0$

) solution obtained for the reference clean case, i.e. without hump (see § 2.5 for the definition of

$\boldsymbol{u}_0$

) solution obtained for the reference clean case, i.e. without hump (see § 2.5 for the definition of

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_0$

). Constructing the aerofoil shape with hump for simulations is performed in two steps, shown in figure 1(c). First, the aerofoil is rotated to make the tangent line to the aerofoil at

$\boldsymbol{u}_0$

). Constructing the aerofoil shape with hump for simulations is performed in two steps, shown in figure 1(c). First, the aerofoil is rotated to make the tangent line to the aerofoil at

![]() $x/c_x=0.15$

horizontal. Then, each point of the hump is shifted vertically downward equal to the vertical distance between the clean aerofoil and the tangent line, i.e.

$x/c_x=0.15$

horizontal. Then, each point of the hump is shifted vertically downward equal to the vertical distance between the clean aerofoil and the tangent line, i.e.

![]() $\Delta y_p (x)=-\Delta y(x)$

. The hump denoted in orange in figure 1(c) shows the final projected shape of the hump on the aerofoil. Note that the nominal hump shape used for the simulations is an idealised shape of the one presented in Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025), leading to slightly different relative heights and geometry at the leading and trailing edge parts of the hump (see figure 1b of Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025)). These differences were found to have a negligible influence on the results of this work.

$\Delta y_p (x)=-\Delta y(x)$

. The hump denoted in orange in figure 1(c) shows the final projected shape of the hump on the aerofoil. Note that the nominal hump shape used for the simulations is an idealised shape of the one presented in Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025), leading to slightly different relative heights and geometry at the leading and trailing edge parts of the hump (see figure 1b of Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025)). These differences were found to have a negligible influence on the results of this work.

2.3. Computational approach

The DNS are performed in the normal-to-the-leading-edge coordinate system, using Nek5000 code (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer2008), solving the conservation equations for an incompressible fluid.

Performing DNS on a domain that contains the entire wing and wind tunnel walls is impractical. Thus, the final three-dimensional DNS is performed on a smaller section of the wing, with appropriate boundary conditions applied. To obtain the boundary conditions, two precursor simulations are performed on larger domains. In total, the three different domains used for these three simulations are shown in figure 2(a).

Figure 2. (a) Computational domains used in this work shown in the

![]() $XY$

coordinate system. In (a), the RANS domain is coloured in grey, while the domains for 2.5-dimensional and three-dimensional DNS are enclosed by solid red and blue lines, respectively. (b) The 2.5-dimensional (grey) and three-dimensional (coloured by

$XY$

coordinate system. In (a), the RANS domain is coloured in grey, while the domains for 2.5-dimensional and three-dimensional DNS are enclosed by solid red and blue lines, respectively. (b) The 2.5-dimensional (grey) and three-dimensional (coloured by

![]() $u$

velocity) domains in the

$u$

velocity) domains in the

![]() $xy$

coordinate system. The inset in (b) shows the generated high-order mesh close to the wall in case A1-C. The black and grey lines in the inset mark the element boundaries and internal grids, respectively.

$xy$

coordinate system. The inset in (b) shows the generated high-order mesh close to the wall in case A1-C. The black and grey lines in the inset mark the element boundaries and internal grids, respectively.

First, a spanwise-invariant 2.5-dimensional Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) simulation of the aerofoil section placed inside the wind tunnel is performed. This simulation is performed with the M-Edge code (Eliasson Reference Eliasson2001) using the Spalart–Allmaras one-equation model (Spalart & Allmaras Reference Spalart and Allmaras1992). Laminar–turbulent transition is artificially triggered at

![]() $x/c_x=0.17$

on the suction side of the aerofoil, which corresponds to the location of a zigzag tape used in the wind tunnel model of Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025). On the pressure side, transition is triggered at

$x/c_x=0.17$

on the suction side of the aerofoil, which corresponds to the location of a zigzag tape used in the wind tunnel model of Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025). On the pressure side, transition is triggered at

![]() $x/c_x=0.6$

, which is close to the location of the minimum pressure. This is done to avoid unsteady RANS solutions due to laminar separation. Then, the resulting meanflow velocity field is used to obtain boundary conditions for a 2.5-dimensional DNS on a smaller domain (enclosed by the red lines in figure 2

a), as is discussed in § 2.4. The 2.5-dimensional simulations are performed under the infinite swept-wing assumption. In this set-up, the spanwise velocity component

$x/c_x=0.6$

, which is close to the location of the minimum pressure. This is done to avoid unsteady RANS solutions due to laminar separation. Then, the resulting meanflow velocity field is used to obtain boundary conditions for a 2.5-dimensional DNS on a smaller domain (enclosed by the red lines in figure 2

a), as is discussed in § 2.4. The 2.5-dimensional simulations are performed under the infinite swept-wing assumption. In this set-up, the spanwise velocity component

![]() $w$

is considered as a passive scalar, and can be decoupled from

$w$

is considered as a passive scalar, and can be decoupled from

![]() $u$

and

$u$

and

![]() $v$

velocity components. The resulting flow field is used to obtain the boundary conditions for the final three-dimensional DNS performed on the pressure side of the wing (in agreement with the experiments), and over

$v$

velocity components. The resulting flow field is used to obtain the boundary conditions for the final three-dimensional DNS performed on the pressure side of the wing (in agreement with the experiments), and over

![]() $0.055\lt x/c_x\lt 0.69$

(enclosed by blue lines in figure 2

a). The 2.5-dimensional (grey area) and three-dimensional (coloured by

$0.055\lt x/c_x\lt 0.69$

(enclosed by blue lines in figure 2

a). The 2.5-dimensional (grey area) and three-dimensional (coloured by

![]() $u$

velocity) domains in the normal-to-leading-edge coordinate system are shown in figure 2(b). The distance between the horizontal top boundary and wall in the three-dimensional DNS is

$u$

velocity) domains in the normal-to-leading-edge coordinate system are shown in figure 2(b). The distance between the horizontal top boundary and wall in the three-dimensional DNS is

![]() ${\approx} 20 \,\%$

of the chord at the inlet, and

${\approx} 20 \,\%$

of the chord at the inlet, and

![]() ${\approx} 12 \,\%$

of the chord at the outlet.

${\approx} 12 \,\%$

of the chord at the outlet.

2.3.1. Generation of stationary CF modes

In the experiments of Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025), the wavelength and amplitude of stationary CF perturbations are conditioned through DREs with a nominal height of 25 μm and a spanwise spacing of

![]() $\lambda _z=7.5$

mm, identified as a part of the critical and dangerous CFI modes reaching high levels of amplification prior to natural transition. To adjust the amplitude of CFVs, the DREs are placed at two different chordwise locations, i.e.

$\lambda _z=7.5$

mm, identified as a part of the critical and dangerous CFI modes reaching high levels of amplification prior to natural transition. To adjust the amplitude of CFVs, the DREs are placed at two different chordwise locations, i.e.

![]() $x/c_x=0.05$

and

$x/c_x=0.05$

and

![]() $x/c_x=0.02$

, resulting in excitation of stationary CF perturbations with relatively low and high amplitudes, respectively.

$x/c_x=0.02$

, resulting in excitation of stationary CF perturbations with relatively low and high amplitudes, respectively.

Both low and high perturbation amplitudes for reference clean (i.e. aerofoil without hump) and hump cases are considered in this work. Four cases are coded as follows: A1 denotes low amplitude and A2 denotes high amplitude; the suffix -C refers to the reference clean configuration and -H refers to the hump case. Cases A1-C and A1-H are introduced in § 4.1 and cases A2-C and A2-H are introduced in § 5.1.

Nonlinear parabolised stability equations implemented in the nonlinear version of the NoLoT framework (Hanifi et al. Reference Hanifi, Henningson, Hein, Bertolotti and Simen1995; Hein et al. Reference Hein, Bertolotti, Simen, Hanifi and Henningson1995) are used to find the shape of the stationary CF perturbations at the inlet of the DNS domain. The base flow for NPSEs is calculated using an in-house solver for the boundary-layer equations. The fundamental and first harmonic modes obtained by NPSEs at the location of the inlet of the three-dimensional DNS domain are superimposed on the inlet velocity profiles as a boundary condition. The initial amplitude of perturbations in NPSEs is iteratively varied until a good match between the downstream perturbations in three-dimensional DNS (both shape and amplitude) and the corresponding measurements from the experiments of Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025) is found for both cases A1-C and A2-C, as shown in §§ 4.1 and 5.1, respectively. The same perturbation profiles obtained for the reference cases are used for the corresponding hump cases A1-H and A2-H. Note that, based on the NPSE calculations, the initial amplitude of the spanwise velocity component of stationary CF perturbation in case A2 is approximately 3.52 times larger than in case A1.

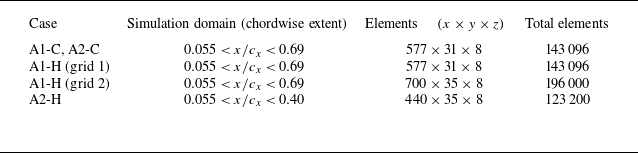

Table 2. Number of elements and simulation domains (chordwise extent) used in the simulations.

2.3.2. Generation of unsteady noise

Due to the low level of numerical noise in the DNS, transition to turbulence typically does not occur in the absence of externally introduced unsteady disturbances. Thus, to effectively model natural transition, the method used by Tocci et al. (Reference Tocci, Chauvat, Rius-Vidales, Kotsonis, Hanifi and Hein2024) is used. Specifically, artificially generated random noise with flat temporal amplitude is introduced through a volume forcing of the

![]() $x$

- and

$x$

- and

![]() $y$

-momentum equations just downstream of the three-dimensional DNS inlet and inside the boundary layer. The spectrum of the noise is comprised of 400 equidistant frequencies within

$y$

-momentum equations just downstream of the three-dimensional DNS inlet and inside the boundary layer. The spectrum of the noise is comprised of 400 equidistant frequencies within

![]() $f_{noise}\in [1100,10\,000]$

Hz, and acts on 16 Fourier modes in the spanwise (

$f_{noise}\in [1100,10\,000]$

Hz, and acts on 16 Fourier modes in the spanwise (

![]() $z$

) direction. The amplitude of the total forcing is adjusted to closely recover the experimentally observed transition location for case A1-C, and the same noise is used for all other simulations (i.e. cases A1-H, A2-C and A2-H). The lower bound of the temporal spectrum of the noise (1100

$z$

) direction. The amplitude of the total forcing is adjusted to closely recover the experimentally observed transition location for case A1-C, and the same noise is used for all other simulations (i.e. cases A1-H, A2-C and A2-H). The lower bound of the temporal spectrum of the noise (1100

![]() $\rm Hz$

) is chosen to avoid transition due to travelling CFIs, in agreement with experiments using the M3J swept-wing model at the TU Delft LTT wind tunnel (e.g. Serpieri & Kotsonis Reference Serpieri and Kotsonis2016; Rius-Vidales et al. Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025).

$\rm Hz$

) is chosen to avoid transition due to travelling CFIs, in agreement with experiments using the M3J swept-wing model at the TU Delft LTT wind tunnel (e.g. Serpieri & Kotsonis Reference Serpieri and Kotsonis2016; Rius-Vidales et al. Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025).

2.3.3. Numerical set-up and grid

To solve the governing equations, the

![]() $\mathbb{P}_N-\mathbb{P}_{N-2}$

formulation (Maday & Patera Reference Maday and Patera1989) in Nek5000 is used with a polynomial order of seven for velocity (

$\mathbb{P}_N-\mathbb{P}_{N-2}$

formulation (Maday & Patera Reference Maday and Patera1989) in Nek5000 is used with a polynomial order of seven for velocity (

![]() $N=7$

) and five for pressure. The number of elements and the chordwise extent of the simulation domain for different cases are summarised in table 2. In the simulations of cases A1-C and A2-C, 143 096 spectral elements are used leading to a total of

$N=7$

) and five for pressure. The number of elements and the chordwise extent of the simulation domain for different cases are summarised in table 2. In the simulations of cases A1-C and A2-C, 143 096 spectral elements are used leading to a total of

![]() $577 \times 31 \times 8 \times 8^3\approx 73.2$

million grid points, where 577, 31 and 8 are the number of elements in

$577 \times 31 \times 8 \times 8^3\approx 73.2$

million grid points, where 577, 31 and 8 are the number of elements in

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

directions, respectively, with

$z$

directions, respectively, with

![]() $8^3$

Gauss–Lobatto–Legendre points within each element. For the convergence test, simulations were also performed using a polynomial order of nine (

$8^3$

Gauss–Lobatto–Legendre points within each element. For the convergence test, simulations were also performed using a polynomial order of nine (

![]() $N=9$

). However, no significant differences were observed in base flows (in the presence of stationary CFVs) compared with the reference grid. The inset in figure 2(b) shows a close-up view of the mesh near the wall for case A1-C, where the black lines mark the boundary of elements and thin grey lines mark the internal grids within each element. For simulations of case A1-H, the same grid resolution as for case A1-C (grid 1 in table 2) and a higher grid resolution (grid 2 in table 2) were used. No significant differences were observed between the base flow solutions obtained with both grids; however, the finer grid was used for simulations with unsteady noise inside the boundary layer. For case A2-H, as is explained in § 5, the outlet of the domain is set at

$N=9$

). However, no significant differences were observed in base flows (in the presence of stationary CFVs) compared with the reference grid. The inset in figure 2(b) shows a close-up view of the mesh near the wall for case A1-C, where the black lines mark the boundary of elements and thin grey lines mark the internal grids within each element. For simulations of case A1-H, the same grid resolution as for case A1-C (grid 1 in table 2) and a higher grid resolution (grid 2 in table 2) were used. No significant differences were observed between the base flow solutions obtained with both grids; however, the finer grid was used for simulations with unsteady noise inside the boundary layer. For case A2-H, as is explained in § 5, the outlet of the domain is set at

![]() $x/c_x \approx 0.4$

. The same grid resolution as the finer grid for case A1-H is used for case A2-H, which results in

$x/c_x \approx 0.4$

. The same grid resolution as the finer grid for case A1-H is used for case A2-H, which results in

![]() $440 \times 35 \times 8$

elements. Note that in all cases, the grid in the

$440 \times 35 \times 8$

elements. Note that in all cases, the grid in the

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $z$

directions is uniform; however, in the

$z$

directions is uniform; however, in the

![]() $y$

direction the grid is clustered near the wall, as depicted in the inset of figure 2(b).

$y$

direction the grid is clustered near the wall, as depicted in the inset of figure 2(b).

2.4. Boundary conditions

For all simulations, the no-slip wall boundary condition on the wing model is imposed. Additionally, for the RANS simulations the no-slip wall boundary condition is used at the top and bottom boundaries (corresponding to the wind tunnel sidewalls; see figure 2), and uniform velocity and standard pressure outlet boundary conditions are imposed at the inlet and outlet of the domain, respectively. At the inlet of the DNS domains, Dirichlet boundary condition is imposed. The inlet velocity profiles for the 2.5-dimensional DNS are interpolated from the solution of the 2.5-dimensional RANS, and those for three-dimensional DNS are interpolated from the flow field obtained by 2.5-dimensional DNS. In addition, for the final three-dimensional DNS, the stationary CF perturbations (estimated through a NPSE stability analysis) are superimposed on the inlet velocity profiles. For the outlet boundary conditions in the DNS domains, a modified version of the natural outflow boundary condition is used, similar to the formulation used by Shahriari (Reference Shahriari2016). This boundary condition is expressed as

where

![]() $p_a$

is the ambient pressure obtained from the precursor simulations as described above. Moreover, to prevent reflections at the outlet boundary condition in the three-dimensional DNS, a sponge region with a width of

$p_a$

is the ambient pressure obtained from the precursor simulations as described above. Moreover, to prevent reflections at the outlet boundary condition in the three-dimensional DNS, a sponge region with a width of

![]() $\Delta x / c_x=0.03$

, which forces the solution to the one obtained from 2.5-dimensional DNS, is used.

$\Delta x / c_x=0.03$

, which forces the solution to the one obtained from 2.5-dimensional DNS, is used.

For the horizontal top boundary in DNS, the same free-stream boundary condition as used by Chauvat (Reference Chauvat2020) and Tocci et al. (Reference Tocci, Chauvat, Rius-Vidales, Kotsonis, Hanifi and Hein2024) is utilised. This reads

Here,

![]() $u_0$

,

$u_0$

,

![]() $v_0$

and

$v_0$

and

![]() $w_0$

are the 2.5-dimensional base flow velocity components, interpolated from the precursor RANS for the 2.5-dimensional DNS, and from the 2.5-dimensional DNS for the three-dimensional DNS. Finally, for the final three-dimensional DNS, periodic boundary conditions are set in the spanwise (

$w_0$

are the 2.5-dimensional base flow velocity components, interpolated from the precursor RANS for the 2.5-dimensional DNS, and from the 2.5-dimensional DNS for the three-dimensional DNS. Finally, for the final three-dimensional DNS, periodic boundary conditions are set in the spanwise (

![]() $z$

) direction, with the spanwise size of the domain chosen to be equal to the nominal spacing of

$z$

) direction, with the spanwise size of the domain chosen to be equal to the nominal spacing of

![]() $\lambda _z = 7.5$

mm between the DREs in the experiment of Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025).

$\lambda _z = 7.5$

mm between the DREs in the experiment of Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025).

2.5. Estimation of stationary perturbation fields and stability metrics

In this work, the spanwise-invariant steady flow obtained in the absence of stationary CF perturbations is referred to as the base flow

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_{0}=[u_{\xi ,0},v_{\eta ',0},w_{0}]^T$

. The stationary primary CF perturbations, i.e.

$\boldsymbol{u}_{0}=[u_{\xi ,0},v_{\eta ',0},w_{0}]^T$

. The stationary primary CF perturbations, i.e.

![]() $ \boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}_s=[u^{\prime}_{\xi ,s},v^{\prime}_{\eta ',s},w^{\prime}_s]^T$

, are calculated based on time-averaged flow, i.e.

$ \boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}_s=[u^{\prime}_{\xi ,s},v^{\prime}_{\eta ',s},w^{\prime}_s]^T$

, are calculated based on time-averaged flow, i.e.

![]() $\bar {\boldsymbol{u}}=[\bar {u}_{\xi },\bar {v}_{\eta '},\bar {w} ]^T$

, and base flow

$\bar {\boldsymbol{u}}=[\bar {u}_{\xi },\bar {v}_{\eta '},\bar {w} ]^T$

, and base flow

![]() $\boldsymbol{u_0}$

as

$\boldsymbol{u_0}$

as

where subscript ‘

![]() $s$

‘ denotes stationary perturbations.

$s$

‘ denotes stationary perturbations.

Stationary CF perturbation spanwise harmonic modes,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\hat {u}}_{n\beta _0}=[\hat {u}_{\xi ,n\beta _0},\hat {v}_{\eta ',n\beta _0},\hat {w}_{n\beta _0}]^T$

, are calculated using a spanwise Fourier transform of

$\boldsymbol{\hat {u}}_{n\beta _0}=[\hat {u}_{\xi ,n\beta _0},\hat {v}_{\eta ',n\beta _0},\hat {w}_{n\beta _0}]^T$

, are calculated using a spanwise Fourier transform of

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_s'$

. Here,

$\boldsymbol{u}_s'$

. Here,

![]() $n$

indicates the harmonic mode with corresponding spanwise wavenumber

$n$

indicates the harmonic mode with corresponding spanwise wavenumber

![]() $n\beta _0$

, with

$n\beta _0$

, with

![]() $\beta _0=2\pi / \lambda _z$

defined as the fundamental spanwise wavenumber (

$\beta _0=2\pi / \lambda _z$

defined as the fundamental spanwise wavenumber (

![]() $\lambda _z=7.5$

mm). This reads

$\lambda _z=7.5$

mm). This reads

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}_s(\xi ,\eta ',z)\approx \sum _{n=-N_z}^{N_z} \boldsymbol{\hat {u}}_{n \beta _0}(\xi , \eta ', z) =\sum _{n=-N_z}^{N_z} \tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}_{n\beta _0}(\xi ,\eta ')\exp {({\rm i}n\beta _0 z)}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}_s(\xi ,\eta ',z)\approx \sum _{n=-N_z}^{N_z} \boldsymbol{\hat {u}}_{n \beta _0}(\xi , \eta ', z) =\sum _{n=-N_z}^{N_z} \tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}_{n\beta _0}(\xi ,\eta ')\exp {({\rm i}n\beta _0 z)}, \end{equation}

where

![]() ${\rm i}=\sqrt {-1}$

and

${\rm i}=\sqrt {-1}$

and

![]() $\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}=[\tilde {u}_{\xi },\tilde {v}_{\eta '},\tilde {w}]^T$

denotes the complex-valued Fourier coefficients. The amplitude of the

$\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}=[\tilde {u}_{\xi },\tilde {v}_{\eta '},\tilde {w}]^T$

denotes the complex-valued Fourier coefficients. The amplitude of the

![]() $n{\rm th}$

-harmonic spanwise Fourier mode, i.e.

$n{\rm th}$

-harmonic spanwise Fourier mode, i.e.

![]() $A_{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}_{n\beta _0}}=[A_{\tilde {u}_{\xi }}, A_{\tilde {v}_{\eta '}}, A_{\tilde {w}} ]_{n\beta _0}^T$

, is defined as

$A_{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}_{n\beta _0}}=[A_{\tilde {u}_{\xi }}, A_{\tilde {v}_{\eta '}}, A_{\tilde {w}} ]_{n\beta _0}^T$

, is defined as

where

![]() $Q_{{\textit{ref}}}$

is the reference velocity (see § 2.7) and

$Q_{{\textit{ref}}}$

is the reference velocity (see § 2.7) and

![]() $n=1$

specifies the fundamental mode. Note that the coefficient 2 accounts for the contribution of both the positive and negative wavenumber components in the real-valued physical field. Furthermore, the spatial (i.e. along

$n=1$

specifies the fundamental mode. Note that the coefficient 2 accounts for the contribution of both the positive and negative wavenumber components in the real-valued physical field. Furthermore, the spatial (i.e. along

![]() $\xi$

) growth rate of each spanwise mode, i.e.

$\xi$

) growth rate of each spanwise mode, i.e.

![]() $\boldsymbol{\sigma }_{n\beta _0}=[\sigma _{\tilde {u}_\xi },\sigma _{\tilde {v}_{\eta '}},\sigma _{\tilde {w}}]_{n\beta _0}^T$

, can be calculated based on the amplitude of that mode, i.e.

$\boldsymbol{\sigma }_{n\beta _0}=[\sigma _{\tilde {u}_\xi },\sigma _{\tilde {v}_{\eta '}},\sigma _{\tilde {w}}]_{n\beta _0}^T$

, can be calculated based on the amplitude of that mode, i.e.

![]() $A_{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}_{n\beta _0}}$

, as

$A_{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}_{n\beta _0}}$

, as

where a central finite difference scheme is used to calculate the derivative.

Following Downs & White (Reference Downs and White2013), the steady CF disturbance profile

![]() $\langle \boldsymbol{\bar {u}}\rangle _z(\eta ')=[{\langle \bar {u}_{\xi } \rangle }_z , {\langle \bar {v}_{\eta '} \rangle }_z , {\langle \bar {w} \rangle }_z]^T$

at each

$\langle \boldsymbol{\bar {u}}\rangle _z(\eta ')=[{\langle \bar {u}_{\xi } \rangle }_z , {\langle \bar {v}_{\eta '} \rangle }_z , {\langle \bar {w} \rangle }_z]^T$

at each

![]() $z{-}\eta '$

plane is calculated as the spanwise standard deviation of time-averaged velocity profiles

$z{-}\eta '$

plane is calculated as the spanwise standard deviation of time-averaged velocity profiles

![]() $\bar {\boldsymbol{u}}$

. This reads as

$\bar {\boldsymbol{u}}$

. This reads as

\begin{equation} \langle {\boldsymbol{\bar {u}}} \rangle _z=\sqrt {\frac {1}{n_z}\sum _{k=1}^{n_z}{[\bar {\boldsymbol{u}}(\eta ',z_k)-{\bar {{\bar {\boldsymbol{u}}}}} (\eta ')]^2 }}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \langle {\boldsymbol{\bar {u}}} \rangle _z=\sqrt {\frac {1}{n_z}\sum _{k=1}^{n_z}{[\bar {\boldsymbol{u}}(\eta ',z_k)-{\bar {{\bar {\boldsymbol{u}}}}} (\eta ')]^2 }}, \end{equation}

where

![]() $\bar {{\bar {\boldsymbol{u}}}}$

are the time- and spanwise-averaged velocity profiles and

$\bar {{\bar {\boldsymbol{u}}}}$

are the time- and spanwise-averaged velocity profiles and

![]() $n_z$

is the number of sampling points in the spanwise (

$n_z$

is the number of sampling points in the spanwise (

![]() $z$

) direction. Note that steady disturbance profiles can also be calculated as the spanwise root mean square of the stationary perturbations (i.e.

$z$

) direction. Note that steady disturbance profiles can also be calculated as the spanwise root mean square of the stationary perturbations (i.e.

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}_s$

, defined by (2.7)). In this case, they are denoted as

$\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}_s$

, defined by (2.7)). In this case, they are denoted as

![]() $\langle \boldsymbol{{u}}^{\prime}_s\rangle _z(\eta ')=[{\langle {u}^{\prime}_{\xi ,s} \rangle }_z , {\langle {v}^{\prime}_{\eta ',s} \rangle }_z , {\langle {w}^{\prime}_s \rangle }_z]^T$

. This metric is used in §§ 4.1 and 5.1 when the analysis is based on the DNS data. However, to enable comparison with the experimental data, they are calculated based on (2.11), since it is not possible to obtain the base flow in the experiments. Note that the other stability metrics defined above are still calculated based on the stationary perturbations

$\langle \boldsymbol{{u}}^{\prime}_s\rangle _z(\eta ')=[{\langle {u}^{\prime}_{\xi ,s} \rangle }_z , {\langle {v}^{\prime}_{\eta ',s} \rangle }_z , {\langle {w}^{\prime}_s \rangle }_z]^T$

. This metric is used in §§ 4.1 and 5.1 when the analysis is based on the DNS data. However, to enable comparison with the experimental data, they are calculated based on (2.11), since it is not possible to obtain the base flow in the experiments. Note that the other stability metrics defined above are still calculated based on the stationary perturbations

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}_s$

.

$\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}_s$

.

2.6. Energy budget analysis

In § 4.2.2, the transfer of energy between base flow

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_0$

and CF perturbations is studied using the Reynolds–Orr equation, which governs the transfer of perturbation kinetic energy (Schmid & Henningson Reference Schmid and Henningson2001). The analysis here is restricted to the fundamental primary CFI stationary mode (i.e.

$\boldsymbol{u}_0$

and CF perturbations is studied using the Reynolds–Orr equation, which governs the transfer of perturbation kinetic energy (Schmid & Henningson Reference Schmid and Henningson2001). The analysis here is restricted to the fundamental primary CFI stationary mode (i.e.

![]() $1\beta _0$

) and production term

$1\beta _0$

) and production term

![]() $\mathcal{P}$

, which explains the kinetic energy exchange between the base flow

$\mathcal{P}$

, which explains the kinetic energy exchange between the base flow

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_0$

and the fundamental primary CFI stationary mode

$\boldsymbol{u}_0$

and the fundamental primary CFI stationary mode

![]() $\boldsymbol{\tilde {u}}_{1\beta _0}$

. Following Casacuberta et al. (Reference Casacuberta, Hickel, Westerbeek and Kotsonis2022), the total production term using complex-valued Fourier coefficients

$\boldsymbol{\tilde {u}}_{1\beta _0}$

. Following Casacuberta et al. (Reference Casacuberta, Hickel, Westerbeek and Kotsonis2022), the total production term using complex-valued Fourier coefficients

![]() $(\tilde {u}_{\xi },\tilde {v}_{\eta '},\tilde {w})$

can be written as

$(\tilde {u}_{\xi },\tilde {v}_{\eta '},\tilde {w})$

can be written as

with

\begin{align} \varLambda _{1\beta _0}(\xi ,\eta ') &= ( \tilde {u}_{\xi ,1\beta _0} {\tilde {u}^\dagger }_{\xi ,1\beta _0} + {\rm c.c.} ) \frac {\partial u_{\xi ,0}}{\partial \xi } + ( \tilde {u}_{\xi ,1\beta _0} {\tilde {v}^\dagger }_{\eta ',1\beta _0} + {\rm c.c.} ) \frac {\partial u_{\xi ,0}}{\partial \eta '} \notag \\[3pt] &\quad + ( \tilde {v}_{\eta ',1\beta _0} {\tilde {u}^\dagger }_{\xi ,1\beta _0} + {\rm c.c.} ) \frac {\partial v_{\eta ',0}}{\partial \xi } + ( \tilde {v}_{\eta ',1\beta _0} {\tilde {v}^\dagger }_{\eta ',1\beta _0} + {\rm c.c.} ) \frac {\partial v_{\eta ',0}}{\partial \eta '} \notag \\[3pt] &\quad + ( \tilde {w}_{1\beta _0} {\tilde {u}^\dagger }_{\xi ,1\beta _0} + {\rm c.c.} ) \frac {\partial w_0}{\partial \xi } + ( \tilde {w}_{1\beta _0} {\tilde {v}^\dagger }_{\eta ',1\beta _0} + {\rm c.c.} ) \frac {\partial w_0}{\partial \eta '}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \varLambda _{1\beta _0}(\xi ,\eta ') &= ( \tilde {u}_{\xi ,1\beta _0} {\tilde {u}^\dagger }_{\xi ,1\beta _0} + {\rm c.c.} ) \frac {\partial u_{\xi ,0}}{\partial \xi } + ( \tilde {u}_{\xi ,1\beta _0} {\tilde {v}^\dagger }_{\eta ',1\beta _0} + {\rm c.c.} ) \frac {\partial u_{\xi ,0}}{\partial \eta '} \notag \\[3pt] &\quad + ( \tilde {v}_{\eta ',1\beta _0} {\tilde {u}^\dagger }_{\xi ,1\beta _0} + {\rm c.c.} ) \frac {\partial v_{\eta ',0}}{\partial \xi } + ( \tilde {v}_{\eta ',1\beta _0} {\tilde {v}^\dagger }_{\eta ',1\beta _0} + {\rm c.c.} ) \frac {\partial v_{\eta ',0}}{\partial \eta '} \notag \\[3pt] &\quad + ( \tilde {w}_{1\beta _0} {\tilde {u}^\dagger }_{\xi ,1\beta _0} + {\rm c.c.} ) \frac {\partial w_0}{\partial \xi } + ( \tilde {w}_{1\beta _0} {\tilde {v}^\dagger }_{\eta ',1\beta _0} + {\rm c.c.} ) \frac {\partial w_0}{\partial \eta '}. \end{align}

Here, superscript

![]() $\dagger$

and

$\dagger$

and

![]() ${\rm c.c.}$

stand for complex conjugate, and

${\rm c.c.}$

stand for complex conjugate, and

![]() $\mathcal{I}_{\mathcal{P}_{1\beta _0}}=(-2\pi / \beta _0)\varLambda _{1\beta _0}$

. If

$\mathcal{I}_{\mathcal{P}_{1\beta _0}}=(-2\pi / \beta _0)\varLambda _{1\beta _0}$

. If

![]() $\mathcal{P}_{1\beta _0}\gt 0$

, the transfer of kinetic energy is from the base flow to the perturbation field, which has a destabilising effect on perturbations. However, if

$\mathcal{P}_{1\beta _0}\gt 0$

, the transfer of kinetic energy is from the base flow to the perturbation field, which has a destabilising effect on perturbations. However, if

![]() $\mathcal{P}_{1\beta _0}\lt 0$

, kinetic energy is transferred from the perturbation field to the base flow, which has a stabilising effect. The production term itself can be further decomposed into four components (Albensoeder, Kuhlmann & Rath Reference Albensoeder, Kuhlmann and Rath2001):

$\mathcal{P}_{1\beta _0}\lt 0$

, kinetic energy is transferred from the perturbation field to the base flow, which has a stabilising effect. The production term itself can be further decomposed into four components (Albensoeder, Kuhlmann & Rath Reference Albensoeder, Kuhlmann and Rath2001):

each of which expresses a particular energy transfer mechanism between the base flow and the perturbation field. Of particular interest here is the term

![]() $I_2$

, which characterises the lift-up effect (Ellingsen & Palm Reference Ellingsen and Palm1975; Landahl Reference Landahl1975, Reference Landahl1980), i.e. the kinetic energy transfer from the base flow to the streamwise velocity perturbations, through the action of the cross-stream velocity perturbations on the base flow shear. The terms

$I_2$

, which characterises the lift-up effect (Ellingsen & Palm Reference Ellingsen and Palm1975; Landahl Reference Landahl1975, Reference Landahl1980), i.e. the kinetic energy transfer from the base flow to the streamwise velocity perturbations, through the action of the cross-stream velocity perturbations on the base flow shear. The terms

![]() $I_1$

and

$I_1$

and

![]() $I_4$

respectively characterise the self-induction mechanisms of the cross-stream and streamwise perturbations, while the term

$I_4$

respectively characterise the self-induction mechanisms of the cross-stream and streamwise perturbations, while the term

![]() $I_3$

represents an effect opposite to the lift-up mechanism (Antkowiak & Brancher Reference Antkowiak and Brancher2007). The reader is referred to Casacuberta et al. (Reference Casacuberta, Hickel and Kotsonis2024) for the explicit definition of each term.

$I_3$

represents an effect opposite to the lift-up mechanism (Antkowiak & Brancher Reference Antkowiak and Brancher2007). The reader is referred to Casacuberta et al. (Reference Casacuberta, Hickel and Kotsonis2024) for the explicit definition of each term.

2.7. Reference values

The boundary-layer edge velocity magnitude (

![]() $Q_{{\textit{ref}}}=23.496$

m s−1) and displacement thickness (

$Q_{{\textit{ref}}}=23.496$

m s−1) and displacement thickness (

![]() $\delta ^*_{{\textit{ref}}}=2.687 \times 10^{-4}$

m) at the inlet location of the three-dimensional DNS domain (i.e.

$\delta ^*_{{\textit{ref}}}=2.687 \times 10^{-4}$

m) at the inlet location of the three-dimensional DNS domain (i.e.

![]() $x/c_x=0.055$

) are obtained from the base flow

$x/c_x=0.055$

) are obtained from the base flow

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_0$

for the reference case (see figure 2

b), and are used as reference velocity and wall-normal length scales. Throughout the work, velocity fields along the span are displayed in a wall-normal

$\boldsymbol{u}_0$

for the reference case (see figure 2

b), and are used as reference velocity and wall-normal length scales. Throughout the work, velocity fields along the span are displayed in a wall-normal

![]() $z/\lambda {-}\eta$

plane, where

$z/\lambda {-}\eta$

plane, where

![]() $\lambda =7.5\,\textrm {mm}$

is the spanwise wavelength of the primary CFI and

$\lambda =7.5\,\textrm {mm}$

is the spanwise wavelength of the primary CFI and

![]() $\eta$

is the wall-normal distance from the wall, non-dimensionalised by

$\eta$

is the wall-normal distance from the wall, non-dimensionalised by

![]() $\delta ^*_{{\textit{ref}}}$

, i.e.

$\delta ^*_{{\textit{ref}}}$

, i.e.

![]() $\eta =\eta '/\delta ^*_{{\textit{ref}}}$

. Instead, velocity fields along the chord are visualised in

$\eta =\eta '/\delta ^*_{{\textit{ref}}}$

. Instead, velocity fields along the chord are visualised in

![]() $x/c_x{-}y^*$

planes, where

$x/c_x{-}y^*$

planes, where

![]() $y^*=(y-y_{w,c})/\delta ^*_{{\textit{ref}}}$

, and

$y^*=(y-y_{w,c})/\delta ^*_{{\textit{ref}}}$

, and

![]() $y_{w,c}$

is the

$y_{w,c}$

is the

![]() $y$

coordinate of the wing wall in the reference clean case.

$y$

coordinate of the wing wall in the reference clean case.

3. Base flow modifications induced by the hump

In this section, the effects of the hump on the base flow are investigated. The pressure coefficient (

![]() $-C_p$

) and the pressure gradient

$-C_p$

) and the pressure gradient

![]() $ (c_x(\partial C_p/\partial x) )$

from DNS (for both reference and hump cases) and the experiment of Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025) (for the reference case) are compared in figure 3(a,b). In the experiment, two streamwise rows of pressure taps located at

$ (c_x(\partial C_p/\partial x) )$

from DNS (for both reference and hump cases) and the experiment of Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025) (for the reference case) are compared in figure 3(a,b). In the experiment, two streamwise rows of pressure taps located at

![]() $24\,\%$

and

$24\,\%$

and

![]() $76 \,\%$

of the wing model span were used to measure the pressure. These are denoted by the lower (blue cross) and upper (red circle) rows, referring to their spanwise positions, i.e. closer to the wind tunnel bottom wall and wind tunnel top wall, respectively, not to the lower and upper wing surfaces. Note that, all panels in figure 3 are plotted based on the base flow solution

$76 \,\%$

of the wing model span were used to measure the pressure. These are denoted by the lower (blue cross) and upper (red circle) rows, referring to their spanwise positions, i.e. closer to the wind tunnel bottom wall and wind tunnel top wall, respectively, not to the lower and upper wing surfaces. Note that, all panels in figure 3 are plotted based on the base flow solution

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_0$

for both reference and hump cases. The agreement of

$\boldsymbol{u}_0$

for both reference and hump cases. The agreement of

![]() $C_p$

and

$C_p$

and

![]() $\partial C_p/\partial x$

between DNS and experiment for the reference case is good. Figure 3(a,b) shows that, in the presence of the hump, the pressure is locally modified by the hump, and recovers to the reference case values rapidly downstream of the hump. Therefore, the boundary-layer flow experiences successive pressure-gradient changeovers from favourable pressure gradient (FPG;

$\partial C_p/\partial x$

between DNS and experiment for the reference case is good. Figure 3(a,b) shows that, in the presence of the hump, the pressure is locally modified by the hump, and recovers to the reference case values rapidly downstream of the hump. Therefore, the boundary-layer flow experiences successive pressure-gradient changeovers from favourable pressure gradient (FPG;

![]() $\partial C_p/\partial x\lt 0$

) to adverse pressure gradient (APG;

$\partial C_p/\partial x\lt 0$

) to adverse pressure gradient (APG;

![]() $\partial C_p/\partial x\gt 0$

) and from APG to FPG, until it recovers to the reference case pressure distribution at

$\partial C_p/\partial x\gt 0$

) and from APG to FPG, until it recovers to the reference case pressure distribution at

![]() $x/c_x \approx 0.2$

.

$x/c_x \approx 0.2$

.

Figure 3. Comparison of (a) pressure coefficient

![]() $(-C_p)$

and (b) pressure gradient

$(-C_p)$

and (b) pressure gradient

![]() $(c_x(\partial C_p/\partial x))$

between DNS (reference clean and hump cases) and the experiment of Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025). (c) Displacement thickness (

$(c_x(\partial C_p/\partial x))$

between DNS (reference clean and hump cases) and the experiment of Rius-Vidales et al. (Reference Rius-Vidales, Morais, Westerbeek, Casacuberta, Soyler and Kotsonis2025). (c) Displacement thickness (

![]() $\delta ^*$

) and momentum thickness (

$\delta ^*$

) and momentum thickness (

![]() $\theta \times 5$

). (d) Skin-friction coefficient in direction of

$\theta \times 5$

). (d) Skin-friction coefficient in direction of

![]() $U_t$

and

$U_t$

and

![]() $W_{\textit{cf}}$

. The extent of the hump is highlighted in orange and the location of its apex is marked by the vertical solid orange line at

$W_{\textit{cf}}$

. The extent of the hump is highlighted in orange and the location of its apex is marked by the vertical solid orange line at

![]() $x/c_x=0.15$

. The vertical black dashed lines indicate the beginning and end of the CF reversal region.

$x/c_x=0.15$

. The vertical black dashed lines indicate the beginning and end of the CF reversal region.

The effect of the hump on the boundary-layer displacement thickness

![]() $\delta ^*$

and momentum thickness

$\delta ^*$

and momentum thickness

![]() $\theta$

is shown in figure 3(c). Both

$\theta$

is shown in figure 3(c). Both

![]() $\delta ^*$

and

$\delta ^*$

and

![]() $\theta$

are mostly affected in the region where the pressure gradient is altered by the hump. Overall,

$\theta$

are mostly affected in the region where the pressure gradient is altered by the hump. Overall,

![]() $\delta ^*$

and

$\delta ^*$

and

![]() $\theta$

decrease (compared to reference case values) as the boundary layer flow accelerates over the initial part of the hump, and increase as it decelerates downstream of the hump’s apex. The boundary-layer integral quantities in the presence of the hump recover their values as for the reference case for

$\theta$

decrease (compared to reference case values) as the boundary layer flow accelerates over the initial part of the hump, and increase as it decelerates downstream of the hump’s apex. The boundary-layer integral quantities in the presence of the hump recover their values as for the reference case for

![]() $x/c_x \gtrsim 0.2$

.

$x/c_x \gtrsim 0.2$

.

Figure 3(d) depicts the wall skin-friction coefficient (

![]() $C_{\kern-1.5pt f}$

) calculated from the wall-normal shear of different velocity components. The skin friction in the direction of the outer inviscid streamline (

$C_{\kern-1.5pt f}$

) calculated from the wall-normal shear of different velocity components. The skin friction in the direction of the outer inviscid streamline (

![]() $C_{f,U_{t}}=( {\mu _{\infty }}/({0.5 \rho _{\infty }U_{\infty }^2}))\partial U_{t} / \partial \eta '$

, solid line) remains positive downstream of the hump. This confirms that the flow remains fully attached, and flow separation does not occur downstream of the hump. However, the skin friction in the direction of the CF velocity component (

$C_{f,U_{t}}=( {\mu _{\infty }}/({0.5 \rho _{\infty }U_{\infty }^2}))\partial U_{t} / \partial \eta '$

, solid line) remains positive downstream of the hump. This confirms that the flow remains fully attached, and flow separation does not occur downstream of the hump. However, the skin friction in the direction of the CF velocity component (

![]() $C_{f,W_{\textit{cf}}}=( {\mu _{\infty }}/({0.5 \rho _{\infty }U_{\infty }^2}))\partial W_{\textit{cf}} / \partial \eta '$

, dashed line) becomes negative for

$C_{f,W_{\textit{cf}}}=( {\mu _{\infty }}/({0.5 \rho _{\infty }U_{\infty }^2}))\partial W_{\textit{cf}} / \partial \eta '$

, dashed line) becomes negative for

![]() $0.155\lt x/c_x\lt 0.178$

, suggesting that the CF velocity component reverses its direction (i.e. CF reversal). The inception of the CF reversal region at

$0.155\lt x/c_x\lt 0.178$

, suggesting that the CF velocity component reverses its direction (i.e. CF reversal). The inception of the CF reversal region at

![]() $x/c_x=0.155$

(marked by the vertical black dashed line in figure 3

a–c) corresponds to where the boundary-layer flow begins to accelerate again after encountering the peak APG over the hump. This reversal extends almost to the aft end of the hump, as can be seen in figure 3(d).

$x/c_x=0.155$

(marked by the vertical black dashed line in figure 3

a–c) corresponds to where the boundary-layer flow begins to accelerate again after encountering the peak APG over the hump. This reversal extends almost to the aft end of the hump, as can be seen in figure 3(d).

The inviscid streamline angle

![]() $(\psi _s)$

for the reference and hump cases along the chord (see (2.3) for its definition) is shown in figure 4(a). Modifications of

$(\psi _s)$

for the reference and hump cases along the chord (see (2.3) for its definition) is shown in figure 4(a). Modifications of

![]() $\psi _s$

are mostly evident in the vicinity of the hump, specifically downstream of the apex of the hump and within the CF reversal region. The velocity magnitude at the boundary-layer edge (dashed lines, figure 4

a) shows the acceleration of the boundary-layer flow as it advects over the hump. The evolution of the wall-normal peak of the CF velocity component (in its nominal direction for the reference case, i.e. from

$\psi _s$

are mostly evident in the vicinity of the hump, specifically downstream of the apex of the hump and within the CF reversal region. The velocity magnitude at the boundary-layer edge (dashed lines, figure 4

a) shows the acceleration of the boundary-layer flow as it advects over the hump. The evolution of the wall-normal peak of the CF velocity component (in its nominal direction for the reference case, i.e. from

![]() $+z$

to

$+z$

to

![]() $-z$

) is shown by the solid lines in figure 4(b). The CF component experiences a significant increase in the hump case (compared with the reference case) close to the apex of the hump, which is followed by a weakening of

$-z$

) is shown by the solid lines in figure 4(b). The CF component experiences a significant increase in the hump case (compared with the reference case) close to the apex of the hump, which is followed by a weakening of

![]() $W_{\textit{cf}}$

in the aft part of the hump. The wall-normal peak of the CF reversal is also shown by dashed lines in the same figure. Finally, the spatial development of

$W_{\textit{cf}}$

in the aft part of the hump. The wall-normal peak of the CF reversal is also shown by dashed lines in the same figure. Finally, the spatial development of

![]() $U_t$

and

$U_t$

and

![]() $W_{\textit{cf}}$

is depicted in figure 4(c–f) for reference and hump cases. The region of reversal of CF velocity component is enclosed within the loci of

$W_{\textit{cf}}$

is depicted in figure 4(c–f) for reference and hump cases. The region of reversal of CF velocity component is enclosed within the loci of

![]() $W_{\textit{cf}}=0$

(white-dashed contour line). Evidently, the reversal of

$W_{\textit{cf}}=0$

(white-dashed contour line). Evidently, the reversal of

![]() $W_{\textit{cf}}$

occurs only in a region close to the wall.

$W_{\textit{cf}}$

occurs only in a region close to the wall.

Figure 4. (a) The inviscid streamline angle

![]() $\psi _s$

(solid lines) and velocity magnitude at the inviscid boundary-layer edge

$\psi _s$

(solid lines) and velocity magnitude at the inviscid boundary-layer edge

![]() $Q_e$

(dashed lines). (b) Wall-normal peak of the CF velocity component (solid lines) and reversed CF velocity component (dashed lines). Contour of

$Q_e$

(dashed lines). (b) Wall-normal peak of the CF velocity component (solid lines) and reversed CF velocity component (dashed lines). Contour of

![]() $U_t$

and

$U_t$

and

![]() $W_{\textit{cf}}$

for reference (c,e) and hump (d,f) cases. The white dashed line in (f) indicates

$W_{\textit{cf}}$

for reference (c,e) and hump (d,f) cases. The white dashed line in (f) indicates

![]() $W_{\textit{cf}}=0$

. In (a,b), the extent of the hump is highlighted in orange and the location of its apex is marked by the vertical orange solid line. The vertical black dashed lines in (a,b) indicate the beginning and end of the CF reversal region.

$W_{\textit{cf}}=0$

. In (a,b), the extent of the hump is highlighted in orange and the location of its apex is marked by the vertical orange solid line. The vertical black dashed lines in (a,b) indicate the beginning and end of the CF reversal region.

In figure 5, the

![]() $U_{t}$

and

$U_{t}$

and

![]() $W_{\textit{cf}}$

profiles from the reference clean and hump cases are compared at five locations along the chord. At the apex of the hump and slightly upstream, the magnitude of the CF velocity component is increased due to the presence of the hump, and the wall-normal location of its peak value is moved closer to the wall. However, just downstream of the apex of the hump, the CF velocity component profile is distorted and its direction reverses close to the wall, which causes an additional inflection point in the profile of

$W_{\textit{cf}}$

profiles from the reference clean and hump cases are compared at five locations along the chord. At the apex of the hump and slightly upstream, the magnitude of the CF velocity component is increased due to the presence of the hump, and the wall-normal location of its peak value is moved closer to the wall. However, just downstream of the apex of the hump, the CF velocity component profile is distorted and its direction reverses close to the wall, which causes an additional inflection point in the profile of

![]() $W_{\textit{cf}}$

in that region. Farther downstream (i.e. at

$W_{\textit{cf}}$

in that region. Farther downstream (i.e. at

![]() $x/c_x=0.19$

), although the CF velocity component recovers its nominal direction, its shape differs significantly compared with the reference case. However,

$x/c_x=0.19$

), although the CF velocity component recovers its nominal direction, its shape differs significantly compared with the reference case. However,

![]() $U_{t}$

shows a similar profile to that of the reference case at this location. Finally, for

$U_{t}$

shows a similar profile to that of the reference case at this location. Finally, for

![]() $x/c_x \gtrsim 0.25$

, the CF velocity component almost recovers fully to the shape corresponding to the reference case.

$x/c_x \gtrsim 0.25$

, the CF velocity component almost recovers fully to the shape corresponding to the reference case.

Figure 5. Profiles of

![]() $U_{t}$

and

$U_{t}$

and

![]() $W_{\textit{cf}}$

for the reference clean (black) and hump (red) cases. The profiles are obtained from the base flow

$W_{\textit{cf}}$

for the reference clean (black) and hump (red) cases. The profiles are obtained from the base flow

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_0$

. Note that CF velocity component profiles are multiplied by a factor of 5 for visibility.

$\boldsymbol{u}_0$

. Note that CF velocity component profiles are multiplied by a factor of 5 for visibility.

4. Transition delay by the hump