In the United States today, it is generally accepted that all citizens of the country have a right and even a duty to take part in politics regardless of race, gender, religion, level of education, and age, among other traits (Schildkraut Reference Schildkraut2006). It was not until 1975, however, that the right of US citizens residing outside of the country to participate in federal elections was codified into federal law. Despite this legal inclusion, normative support for overseas Americans’ voting rights is not as solidly embedded in the United States as the inclusion of domestic citizens (Klekowski von Koppenfels Reference Klekowski von Koppenfels, Alonso and Mylonas2021).Footnote 1 This disjuncture between legal inclusion and normative indecision results in an uncertain and uneven approach to overseas voting rights in both policy and practice, with consequences for overseas Americans’ level of engagement.

Along similar lines, the two major American parties also wrestle with questions of permeability and standing as political climates change and new opportunities for growth arise. In the 1970s, both parties sought to be more accessible to the public and to reduce barriers to engagement. More presidential primary elections were held (replacing sparsely attended party-elite–dominated local caucuses); participation in these primaries often was not restricted to registered party members; and the number of delegates representing candidates at conventions was tied more directly to the candidates’ showing in these primaries. The Democrats further extended these reforms by increasing the representation of women, minorities, and younger people at their conventions.

In the same period, the Democrats started building a transnational partisan network to incorporate supporters who were living abroad. In 1972, the organization Democratic Party Committee Abroad (also called Democrats Abroad) sent nine nonvoting delegates to the Democratic National Convention (DNC); in 1976, it was granted the status of a state committee. This meant that convention delegates from abroad could vote on presidential nominations and other party business and also contribute to the party platform. There are officially recognized committees of Democrats Abroad in almost 60 countries. These committees engage in the types of activities sponsored by state and local Democratic Party organizations in the United States, including get-out-the-vote drives, campaign fundraising, and hosting candidate forums (albeit usually through online teleconferencing). Their focus is to ensure that overseas Americans request an overseas absentee ballot. Since 2008, Democrats Abroad has conducted a global presidential primary for Americans abroad who do not vote by absentee ballot in a state-level Democratic primary; the organization caucused through 2004. Democrats Abroad is recognized by the Democratic Party through the seating at the DNC of delegates who reside abroad, after Delaware and before Florida. In 2024, the organization had more delegate votes than Alaska, Wyoming, North Dakota, or South Dakota. Within the DNC, Democrats Abroad has more members than 12 states. The Republican Party does not have an equivalent emigrant party branch because the Republican National Committee voted several times against establishing a formal overseas branch (Dark Reference Dark2003a; Klekowski von Koppenfels Reference Klekowski von Koppenfels, Kernalegenn and van Haute2020). Republicans Overseas was founded in 2013 and is registered in the United States as a political action committee under Section 527 of the Internal Revenue Code rather than as a partisan entity (Klekowski von Koppenfels Reference Klekowski von Koppenfels, Kernalegenn and van Haute2020; Scarrow Reference Scarrow2021).

This article reports on a first-ever worldwide panel survey of Democrats Abroad members that was administered in two waves (i.e., summer and fall of 2024).

This article reports on a first-ever worldwide panel survey of Democrats Abroad members that was administered in two waves (i.e., summer and fall of 2024).

Our goal was to focus on an emerging phenomenon in contemporary party politics: emigrant party branches, which are the extraterritorial arms of a central home-country party (Kernalegenn and Van Haute Reference Kernalegenn and van Haute2020; Van Haute and Kernalegenn Reference Van Haute and Kernalegenn2021). This analysis addresses the factors that promoted or impeded transnational engagement in the 2024 US campaigns. We give particularly close attention to how political integration in another country as an immigrant shapes emigrant involvement in American elections (i.e., political transnational engagement). The following section provides further theoretical background, focusing exclusively on Democrats Abroad because the Republican Party does not have a comparable emigrant party branch.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Although in principle all citizens in a liberal democratic system are free to join a political party or participate in a campaign, researchers have long recognized that only a fraction of the public heeds the call and becomes active in partisan campaigning during elections. In their classic work on political equality and voice, Verba, Schlozman, and Brady (Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995) highlighted the key barriers to involvement in party politics: a lack of personal resources that facilitate engagement; a lack of motivation, confidence, and personal commitment to a cause; and a lack of contacting and networking with party leaders, campaign organizers, and other mobilizing agents. These factors can lead to biases within any party system. Citizens who opt to join and become active in campaigns may be atypical—for example, more educated; more polarized in their preferences, evaluations, and identifications; and more connected to party elites. Such biases in party membership are theoretically important to track in that they can diminish the party’s representativeness and legitimacy.

When parties establish organizations abroad, we expect that some of these biases in activism could emerge as well. However, unique to this context, we might further expect that a party member’s integration into the political system where one has settled affects levels of remote engagement in native-country campaigns—or “political transnationalism” (Itzigsohn Reference Itzigsohn2000; Vertovec Reference Vertovec1999). Three broad bodies of literature around such transnational political engagement (1) examine migrants’ political engagement in the country of origin; (2) study the relationship between migrants’ activities in host-country politics and activism in home-country politicsFootnote 2; and (3) review the role of emigrant party branches in encouraging emigrants’ activism.

In the first body of literature, scholars consider the impact of country of origin on political engagement in a host country. Okundaye, Ishiyama, and Silva (Reference Okundaye, Ishiyama and Silva2022), for example, found that coming from an authoritarian regime has no impact on whether a migrant engages politically in a host country but that coming from a country with high levels of conflict positively affects political engagement. Wals and Rudolph (Reference Wals and Rudolph2019) similarly found that migrants to the United States who were exposed to democracy before immigrating are less likely to trust the US government than those who were socialized under an authoritarian regime. Lazarova et al. (Reference Lazarova, Saalfeld and Seifert2024) noted that coming from an authoritarian government reduces engagement but that the openness of a host country’s integration policies positively affects engagement, thereby moderating the country-of-origin effect.

Along different lines within this first body of literature, Staton, Jackson, and Canache (Reference Staton, Jackson and Canache2007) showed that dual nationality has a negative impact on political engagement among migrants in the United States, whereas Schildkraut (Reference Schildkraut2006) demonstrated that US citizens who do not identify as American are more likely to be engaged civically if they experience individual-level discrimination. Wong et al. (Reference Wong, Ramakrishnan, Lee and Junn2011, 299) concluded that US-born Asian Americans were 22% more likely than foreign-born Asian American respondents to vote in past election cycles. Mügge et al. (Reference Mügge, Kranendonk, Vermeulen and Aydemir2021) further demonstrated a nuanced interaction between politics “at home” and in the host country; those who voiced political interest “at home” tend to also be interested in host-country politics.

The second body of scholarly research concerns transnationalism, or the ties that migrants maintain with their home country—whether socioeconomic, cultural, or political—with “simultaneity” being a defining feature (Goldring Reference Goldring2002; Itzigsohn Reference Itzigsohn2000; Schiller, Basch, and Blanc‐Szanton Reference Schiller, Basch and Blanc‐Szanton1992; Vertovec Reference Vertovec1999). A key question within the literature on transnationalism is the nature of the relationship between engagement in the host country versus the home country. Is there any relationship at all? If so, is there a positive or a negative correlation? Some scholars have posited a zero-sum scenario—namely, that there is a tradeoff between integration and transnationalism: migrants engage in one or the other but not both (Peltoniemi Reference Peltoniemi2018; Tsuda Reference Tsuda2012). Many other scholars, however, now agree that the relationship is more nuanced, where different elements of home-country engagement interact in varied ways with host-country integration (Bilgili Reference Bilgili2014; Bilgili and Erdal Reference Bilgili and Erdal2025; McCann and Rapoport Reference McCann and Rapoport2024; Tsuda Reference Tsuda2012). Ahmadov and Sasse (Reference Ahmadov and Sasse2016) showed that whereas integration in the host-country society has a dampening effect on home-country political engagement, emigrant networks have a positive effect.

In the area of political transnationalism, the nuance of relationships emerges more concretely, with some countries (e.g., Mexico) being outliers with low emigrant participation (Finn and Besserer Rayas Reference Finn and Rayas2024) and high political interest (McCann, Escobar, and Arana Reference McCann, Escobar and Arana2019). Drawing on the case of Romanian migrants, Gherghina and Basarabǎ (Reference Gherghina and Basarabă2024) demonstrated that three factors are key for higher home-country electoral turnout: maintaining ties to the home country, social engagement in the host country, and high political interest.

The political parties and the migrants themselves are not the only actors playing a role in home-country political engagement. The host-country environment has a key role as well—in particular, “reactive ethnicity” (Portes and Rumbaut Reference Portes and Rumbaut2001) or “reactive transnationalism,” which is a retreat to home-country engagement because of (perceived) discrimination or marginalization in the host country (Itzigsohn and Giorguli-Saucedo Reference Itzigsohn and Giorguli-Saucedo2002). There is evidence of this involving US citizens living abroad (Klekowski von Koppenfels Reference Klekowski von Koppenfels2025), and Castañeda, Morales, and Ochoa (Reference Castañeda, Morales and Ochoa2014) found stronger evidence for reactive transnationalism among North African migrants in Paris than among Latine migrants in New York. Other studies have revealed similar findings among migrants living in the Netherlands (Snel, Faber, and Engbersen Reference Snel, Faber and Engbersen2015), Muslim migrants in five European cities (Fleischmann, Phalet, and Klein Reference Fleischmann, Phalet and Klein2011), and Senegalese migrants in Paris (Green, Sarrasin, and Maggi Reference Green, Sarrasin and Maggi2014).

The third body of literature—scholarly inquiry into the establishment of emigrant party branches—is an emerging field, with various studies demonstrating that political-party outreach to citizens outside of the country can have a positive impact on electoral engagement. Van Haute and Kernalegenn (Reference Van Haute and Kernalegenn2021) illustrated how parties might be present abroad and concluded that these party branches are more focused on grassroots and local activities than institutional development. Burgess and Tyburski (Reference Burgess and Tyburski2020) argued that by discovering the potential value of voters abroad, political parties have reduced barriers to registration. In their study of Spain, Vintila, Pamies, and Paradés (Reference Vintila, Pamies and Paradés2023) similarly found that increased barriers to registration reduce engagement. Klekowski von Koppenfels (Reference Klekowski von Koppenfels, Kernalegenn and van Haute2020) argued that due at least in part to the US lack of self-perception as an “emigration state” (Gamlen Reference Gamlen2008), government outreach is limited and political parties have more impact. Soare (Reference Soare2024) mapped four different configurations of parties abroad, and Von Nostitz (Reference Von Nostitz2021) demonstrated that—much as might be expected domestically—parties are most organized where they have the most votes to gain. Yener‐Roderburg and Yetiş (Reference Yener-Roderburg and Yetiş2024) showed that the presence of diaspora organizations has a positive impact on emigrants’ electoral turnout.

For the most part, the literature on political transnationalism focuses on what may be considered more traditional migrant-sending countries, such as the Dominican Republic, the Philippines, Mexico, and Turkey (Burgess Reference Burgess2018; Leal, Lee, and McCann Reference Leal, Lee and McCann2012; Østergaard-Nielsen Reference Østergaard‐Nielsen2003; Yener-Roderburg Reference Yener-Roderburg2022). Comparatively little research has been conducted on engagement with migrant-sending countries from the Global North—and much less the country that is perceived to be the key immigration country: the United States (for exceptions, see Dark III Reference Dark2003a, Reference Dark2003b; and Klekowski von Koppenfels Reference Klekowski von Koppenfels, Kernalegenn and van Haute2020). Because of the different demographic backgrounds and political experiences of American emigrants, we expected to find different determinants of transnational participation. Focusing on transnational electoral campaigning in the American context, this analysis addresses this gap.

Against the backdrop of the many studies referenced previously, we considered two questions. First, to what extent is Democratic Party activism from abroad shaped by variables that reliably influence involvement within the United States (cf. Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995)? We focused on several key attitudinal items (i.e., party identification, ideological position, presidential approval, and confidence in a person’s understanding of US politics); several sociodemographic variables that often are linked to involvement (i.e., education level, age, gender, and childhood political socialization); and outreach from Democratic candidates and campaign organizations.

Second, after taking these factors into account, we asked how variables related to migration and settlement abroad influence transnational campaign activism. We focused specifically on the extent to which a Democratic partisan living abroad identifies as an “expatriate American” (a term that connotes separation from the United States while also affirming national identity and membership); whether a person is a dual-national citizen of the residential country; the likelihood of remaining in that country indefinitely rather than returning to the United States; time spent in the residential country; and incorporation into the party system of the residential country, as indicated by attendance at local party meetings and identification with a party in that country.

The literature on transnationalism suggests that time away from the United States and integration into the residential country as a dual national could undercut involvement in American politics from that distance (Staton, Jackson, and Canache Reference Staton, Jackson and Canache2007). The same could be said about people intending to remain in the residential country throughout their life; however, identifying as an “American expatriate” could signal a willingness to remain an active participant in US campaign politics. A zero-sum view of partisan integration suggests that as Americans living overseas adapt to a new political system, they tend to lose their capacity and enthusiasm to take part in American party politics (McCann and Rapoport Reference McCann and Rapoport2024; Tsuda Reference Tsuda2012).

Conversely, research on party activism within the United States provides clear evidence that activity in one electoral context (e.g., a primary election or attendance at a local caucus meeting) can prompt future activity in different but related contexts. This generally is known as a “spillover effect” in party activism (see, e.g., Foos and De Rooij Reference Foos and De Rooij2017; McCann et al. Reference McCann, Partin, Rapoport and Stone1996; Pastor, Stone, and Rapoport Reference Pastor, Stone and Rapoport1999; Stone, Atkeson, and Rapoport Reference Stone, Atkeson and Rapoport1992; Stone and Rapoport Reference Stone and Rapoport2008). These spillover effects may persist for years, resulting in a spiral of political mobilization. In the case of Democratic Party members living overseas, this literature points toward a positive-sum view of incorporation into a party system abroad; these connections may sustain transnational campaign activism in the American context. We examined these various roots of transnational campaign involvement through a global survey of Democratic Party members, the details of which are discussed in the following section.

RESEARCH DESIGN

Beginning in late June 2024 and continuing for approximately six weeks, we surveyed members of Democrats Abroad around the world. Campaigning in the United States at this time already had commenced, although our data collection ended weeks before Vice President Kamala Harris became the de facto presidential nominee. Per an agreement with the International Executive Committee of Democrats Abroad and our own Institutional Review Boards, anonymous survey links were circulated to party members through a central email list. This list included at least 100,000 email addresses. In total, 2,726 questionnaires were completed (McCann, Klekowski von Koppenfels, and Rapoport Reference McCann, von Koppenfels and Rapoport2025). Because we did not have direct control over the dissemination of survey invitations, exact response rates could not be gauged.Footnote 3

Barriers to entry for Democrats Abroad are low. To join, Americans living overseas need only to register their affiliation through an online portal. There are no membership dues or obligations. However, members are expected to be registered to vote in the United States, and the organization’s website provides a registration link. Consequently, recruitment into Democrats Abroad is broadly comparable to party-registration procedures in the 31 US states that allow voters to declare membership in the Democratic or Republican Party when they register to vote. Joining the Democratic Party abroad is somewhat more demanding, however, in that party registration in this context (i.e., membership in Democrats Abroad) is not coterminous with voter registration. We do not have demographic data on all Americans living outside of the United States to examine biases in recruitment into Democrats Abroad. However, prior research in Canada—the leading destination for American emigrants—suggests that relative to the population of Democratic Party identifiers in that country, members of Democrats Abroad tend to be somewhat older and better educated. Such biases in membership are similarly apparent within the United States proper (McCann and Rapoport Reference McCann and Rapoport2023).

The survey instrument, administered online through the Qualtrics platform, included a wide range of demographic, attitudinal, and behavioral items, many of which are analyzed here. Near the end of the questionnaire, respondents were invited to provide an email address to receive a report on the findings and participate in a subsequent follow-up survey. Remarkably, 75% of respondents (N=1,991) supplied email addresses. Because this survey was conducted less than a month before Joe Biden withdrew from the race, the fortuitous timing allowed us to examine variables of interest in two extraordinarily different political contexts. On October 15, 2024, a second-wave survey was administered, with data collection continuing until the election on November 5.

Between October 15 and November 4, 2024, 1,145 questionnaires were completed and returned (i.e., 58% of those who had provided email addresses and 43% of the original respondents). Although the follow-up survey received a high response rate, there still was concern about bias. Respondents to the second-wave survey were not significantly different from nonrespondents on age, gender, education, ideology, or attitudes toward leaders of the Democratic Party. However, there were moderate (p<0.10) differences on level of activism in 2024, involvement in politics in country of residence, time in that country, likelihood of returning to the United States, and partisanship. As a result, we restricted our analysis to those who responded to both survey waves. This ensured comparability of samples across time, even if the sample size for the first survey wave was somewhat reduced and findings were generalized to a slightly more engaged and rooted population of Democratic partisans.

FINDINGS

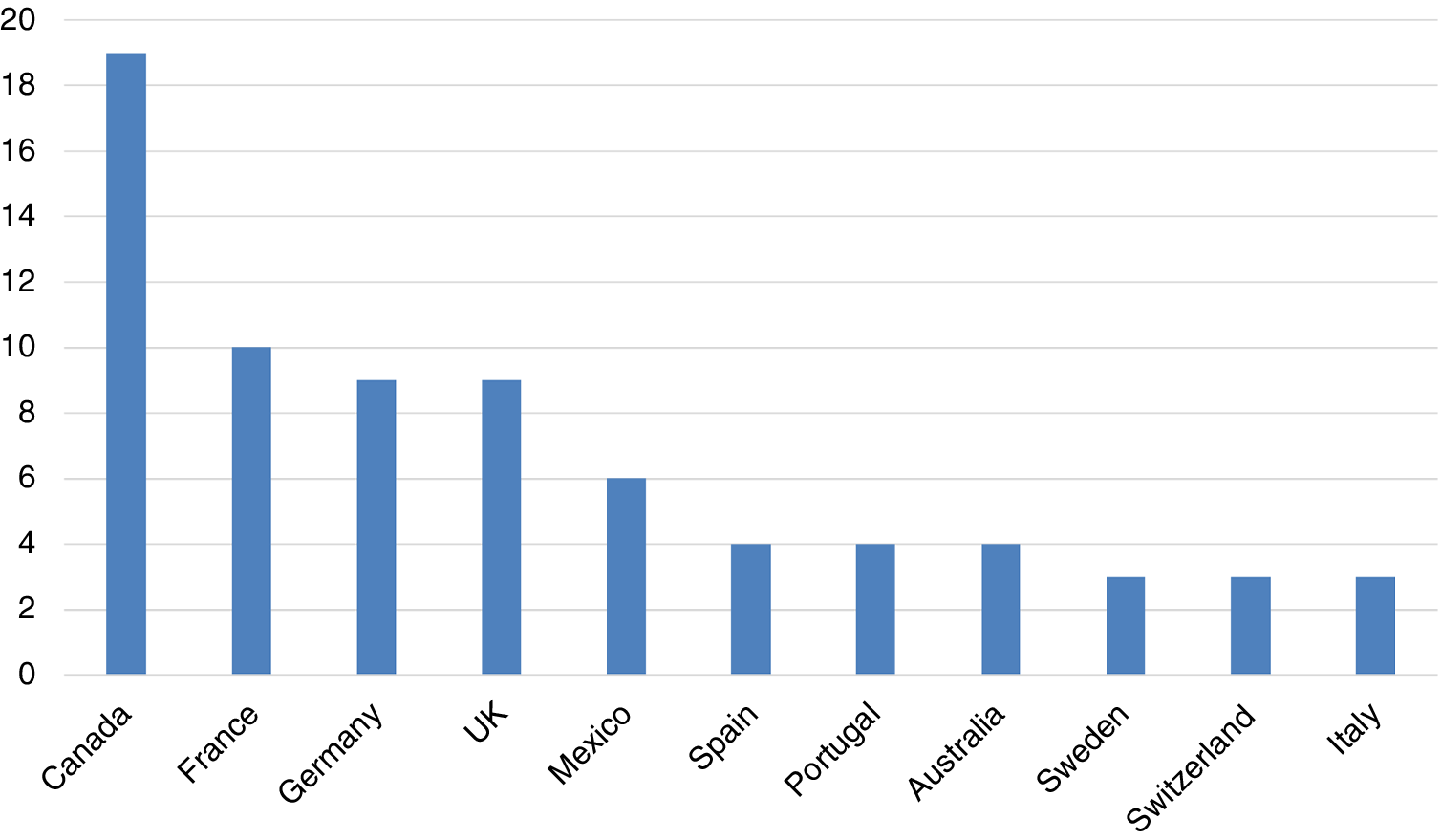

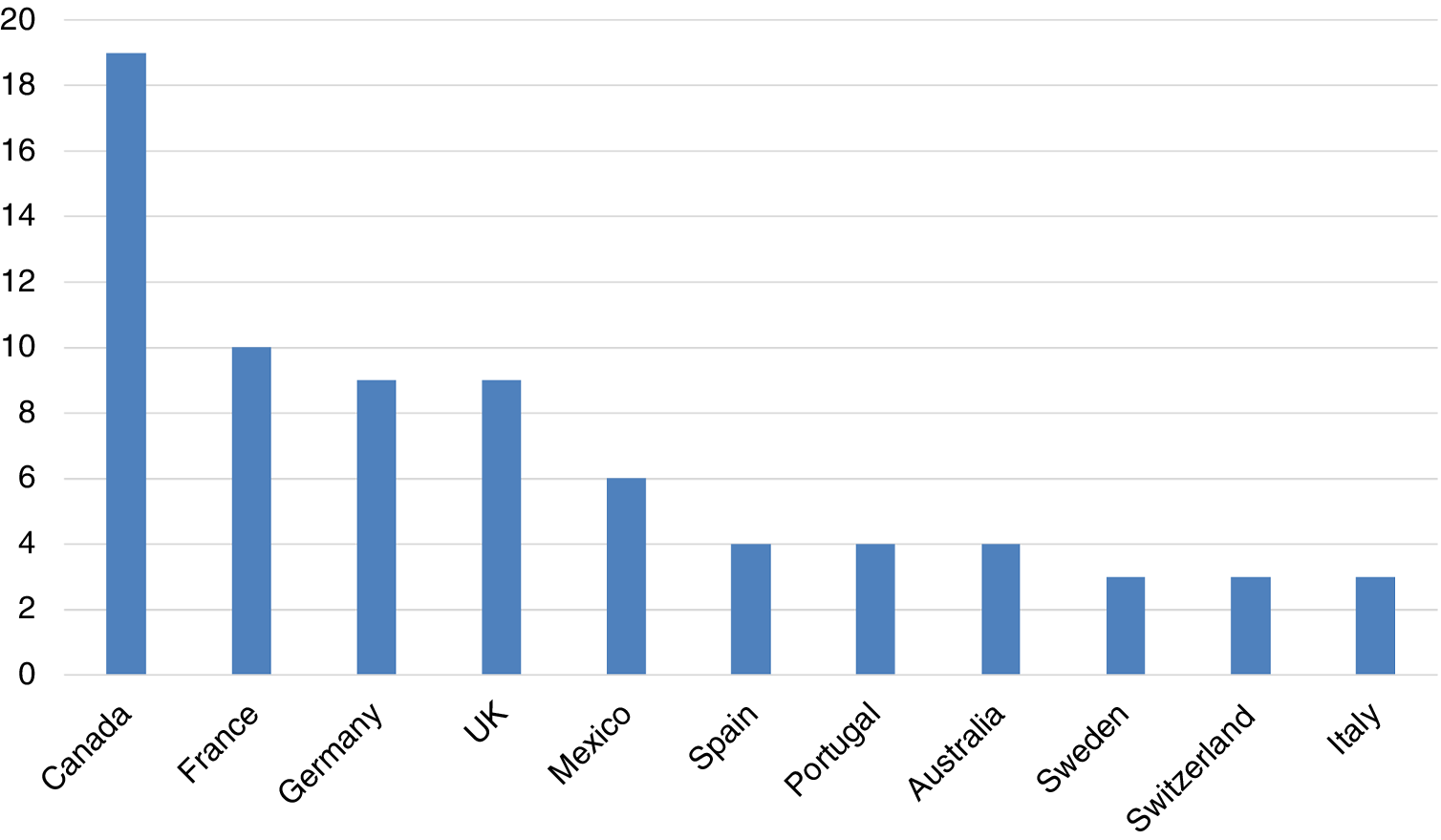

As shown in figure 1, the countries with the most Democratic partisans in our sample were Canada, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Fairly substantial numbers of Democrats also lived in Mexico, Spain, Portugal, and Italy. This distribution across countries broadly aligns with estimates of where Americans settle when they move abroad (Speer Reference Speer2023). The distribution also generally tracks with the count of voting ballots submitted to the United States from abroad in recent election cycles (Federal Voting Assistance Program 2021, 2023).

Figure 1 Major Residential Countries for Respondents in the 2024 Democrats Abroad Study

In the following regression analyses, the forces that prompted transnational campaign involvement are examined in the two distinct phases of the 2024 election: (1) the summertime early-campaign period when Joe Biden headed the ticket; and (2) the late-campaign period when Kamala Harris was the Democratic standard bearer following a divisive intraparty conflict over whether and how to replace Biden. Random effects for the countries in figure 1 and other settlement countries initially were part of these models but then were dropped because of their collective statistical insignificance. Substantively, this lack of significance implies that the features that make residential countries distinctive—political culture and governing systems, for example—did little to raise or lower enthusiasm for remote activism in the US context.Footnote 4

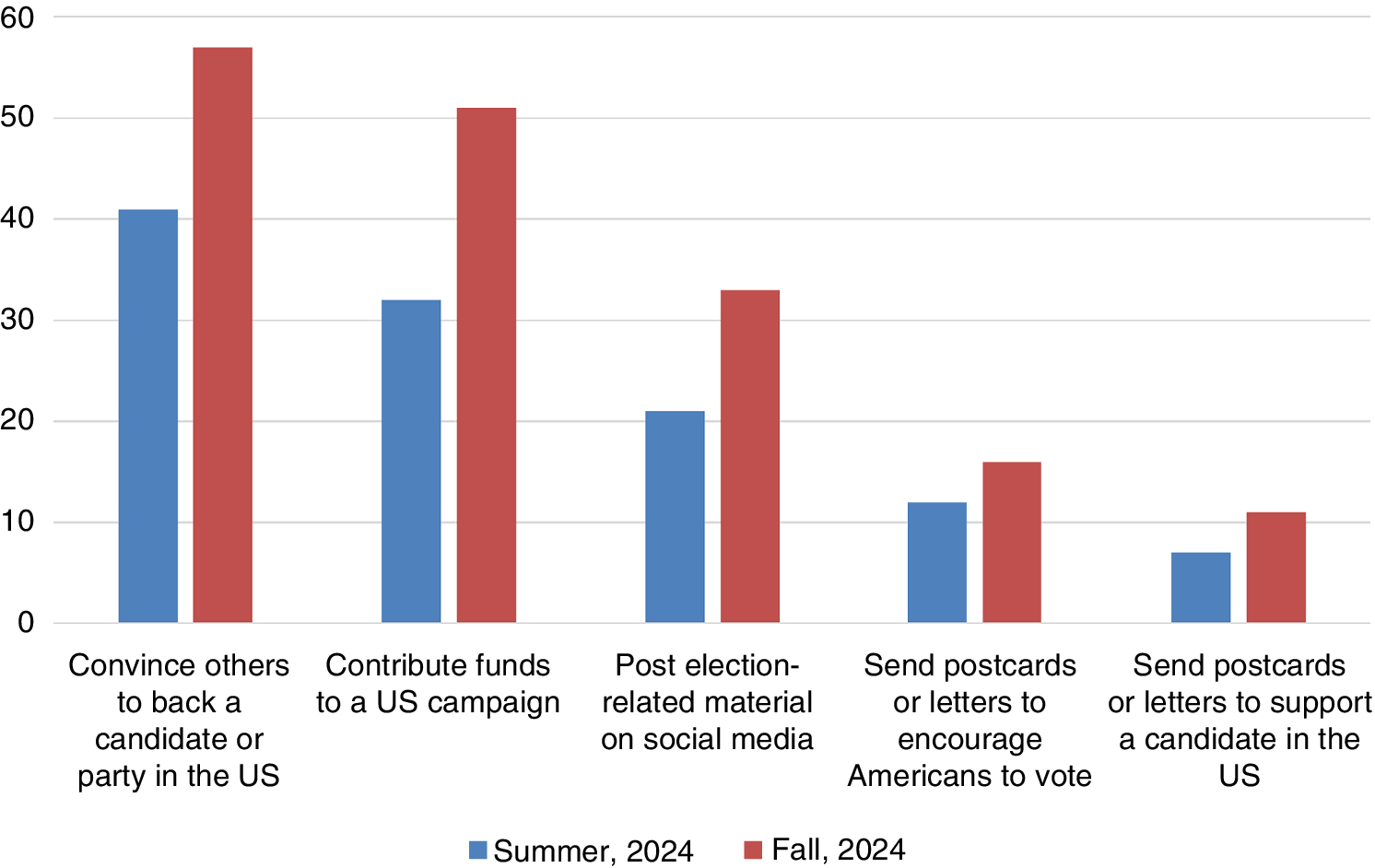

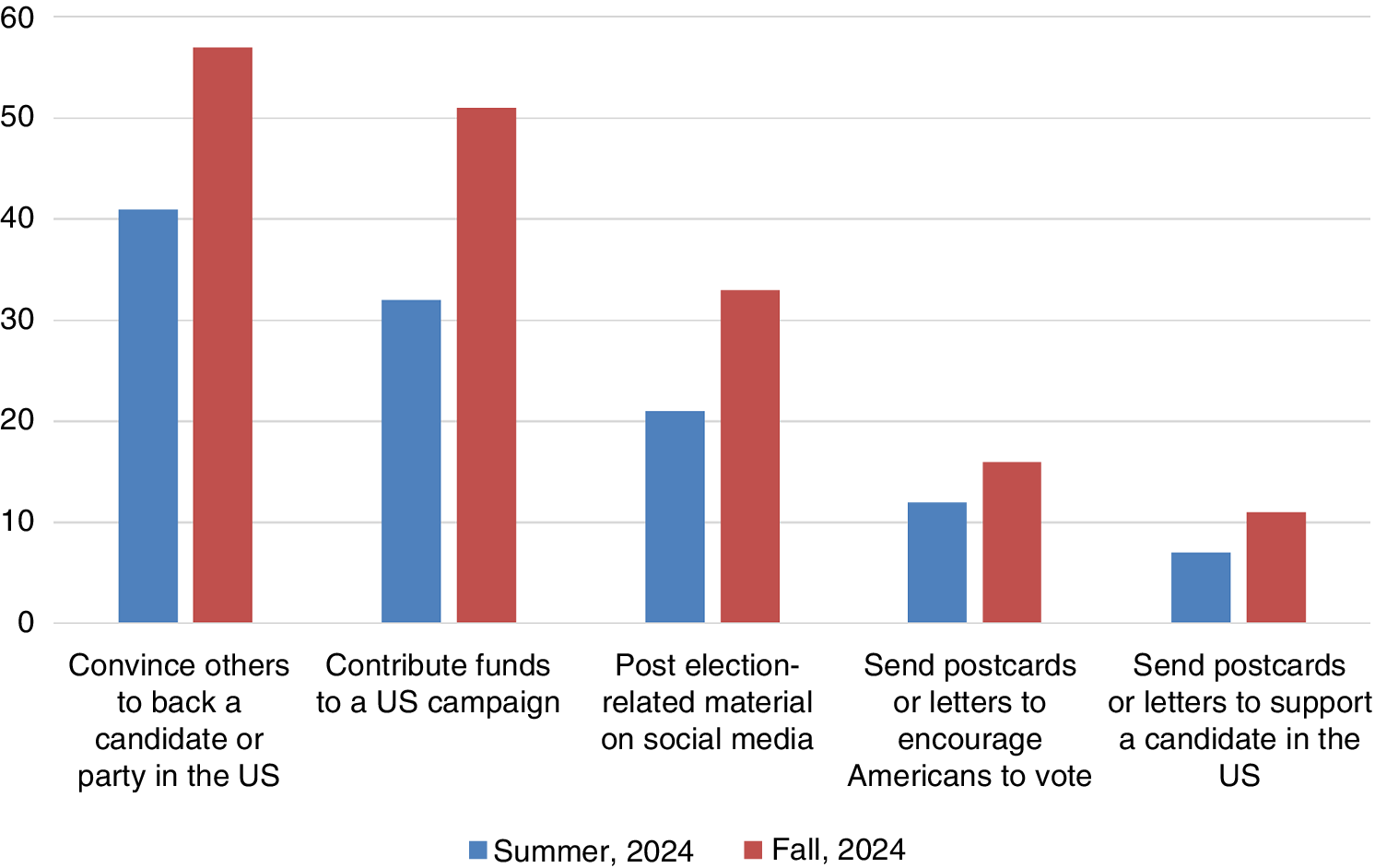

Turning to the dependent variables for analysis, figure 2 presents the distribution of responses to several items on American campaign involvement in both the summer and fall of 2024. In both surveys, Democrats Abroad members indicated whether they had participated in a wide range of activities and, if not, whether they were very likely to do so, only somewhat likely, or not at all likely. To gauge participation, we combined respondents who had participated in an activity with those who stated that they were very likely to do so. These activities were convincing other Americans to back a candidate or party in the United States; contributing funds to a US campaign; posting election-related material on social media; sending postcards or letters to encourage Americans to vote; and sending postcards or letters to support a candidate in the United States. With few exceptions, participating in these activities, in principle, would be feasible no matter where an American citizen had settled; only an Internet or cellular telephone connection is needed. Other items on political participation in neighborhood settings that often appear on election-year questionnaires (e.g., door-to-door canvassing for the party or attending rallies for US candidates) were not included in this battery because they generally would not be feasible activities for Americans living abroad.

Figure 2 Transnational Campaign Engagement: Percentage Reporting Having Done an Activity or Being Very Likely to Do It

Within this sample, a relatively large percentage of respondents—approximately 40%—reported in the first-wave survey that they had convinced others to support an American candidate or party or were very likely to do so. Three months later in the homestretch of the campaign, this percentage increased to 56%. The significant increase in convincing others from summer to fall is understandable given the rising salience of US electoral politics during this period. These rates of persuading others to support a candidate or party are comparable to what might be found among Democrats living in the United States. For example, among respondents in the 2020 American National Election Study who identified as Democrats, 44% indicated that they had convinced others to vote for a candidate; in the 2016 study, 53% reported doing so.

Substantial numbers of Democrats living abroad also reported making campaign contributions or being very likely to contribute.Footnote 5 Fewer Democrats living abroad posted election-related material online or sent postcards or letters on behalf of a candidate. These lower percentages were not surprising given the effort needed to participate in these activities. Summing across these activity measures, we found that in the summer survey wave, 56% of respondents were engaged in some way; 15% indicated two or more activities. In October, 87% reported being engaged with 24% mentioning two or more activities—a remarkable degree of transnational attention to US campaigns.

What prompts political engagement among Democrats living abroad? As previously noted, the main predictors of interest are: items related to the social and demographic profile of partisans; attitudes that have long been linked to campaign involvement in the United States; contacts through telephone calls, emails, texts, postal correspondence, or another way with Democratic Party campaign organizations based in the United States; and variables that pertain to emigration and settlement in another country.

What prompts political engagement among Democrats living abroad? As previously noted, the main predictors of interest are: items related to the social and demographic profile of partisans; attitudes that have long been linked to campaign involvement in the United States; contacts through telephone calls, emails, texts, postal correspondence, or another way with Democratic Party campaign organizations based in the United States; and variables that pertain to emigration and settlement in another country.

These latter factors include the number of years spent in the residential country, likelihood of returning to the United States, strength of identification as an expatriate, dual citizenship, and level of partisan incorporation in the residential country—a three-point scale coded zero for respondents who neither identified with a party in that country nor ever attended a local meeting of a political party, one for respondents who did either, and two for those who did both.

The online appendix table lists the coding and distributions for these items. Respondents generally espoused a strong sense of identification as a Democrat, positioned themselves on the left of the ideological scale, and had favorable views of President Biden and Vice President Harris. These attitudes were not surprising, although members of Democrats Abroad were not all of one mind. For example, 13% only weakly identified with the party and 10% just leaned toward the Democrats, were independent, or considered themselves Republican. Whereas most respondents were on the ideological left, only 14% opted for the leftmost point on the scale. Regarding demographic background variables, respondents tended to be older, with an average age of 66. This also was a well-educated group; almost 66% had a postgraduate education. Such skewed distributions with limited variance imply that these variables may not differentiate transnational campaign activists from nonactivists. Women also outnumbered men, which aligns with a long-standing gender distribution within the Democratic Party in the United States (Gilens Reference Gilens2023).

Our sample respondents also tended to be well rooted in their residential country. Approximately 50% reported living in that country more than 20 years and almost 50% had become citizens there. Less than 25% anticipated returning someday to the United States, and only 33% “strongly” identified as an American expatriate. Regarding partisan incorporation in the settlement country, 46% either identified as a partisan in that context or had gone to a local meeting of any party; 25% considered themselves partisans and reported attending party meetings.

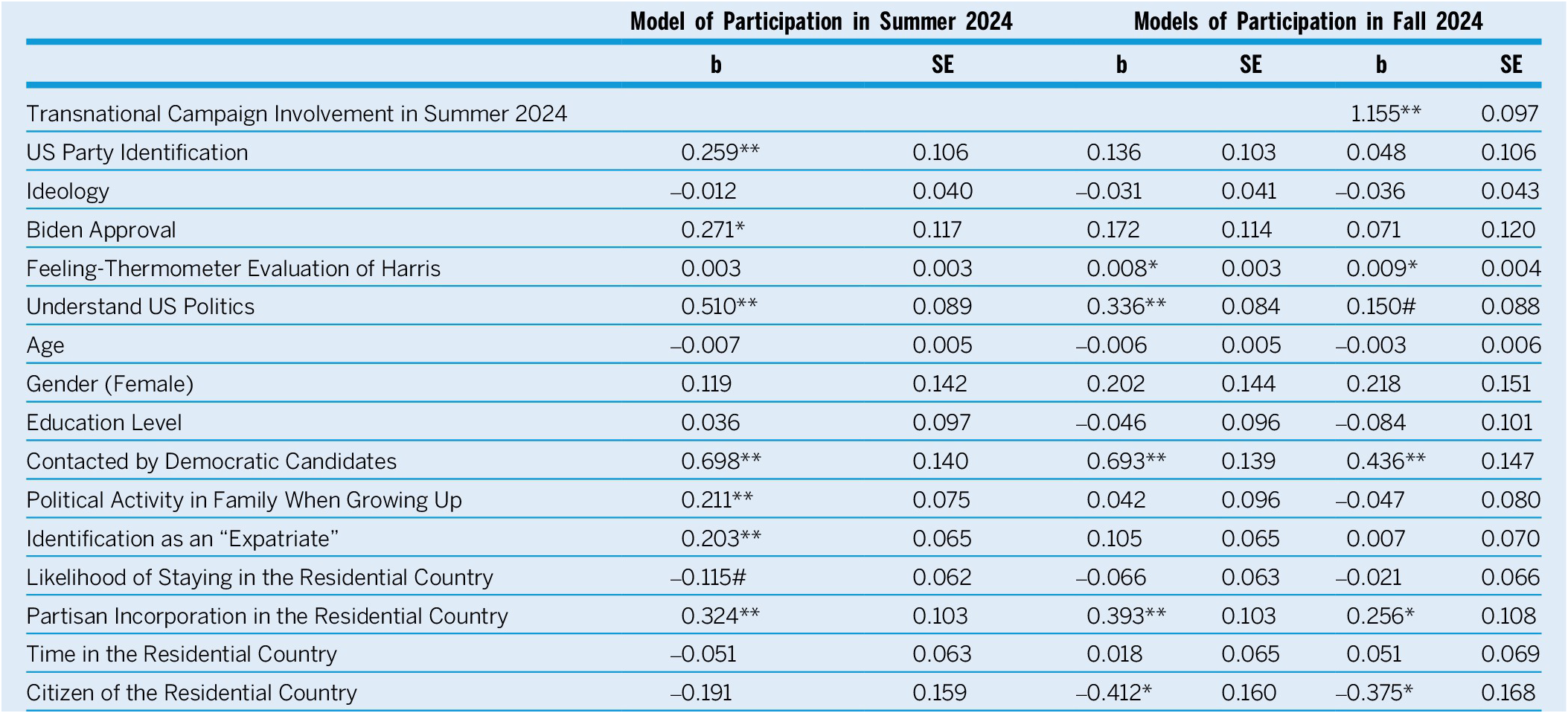

To what extent did these variables shape transnational campaign engagement? Estimates from the ordered logistic regression models in table 1 list many significant predictors of engagement in the summer of 2024. The dependent variable is an ordered three-category indicator of the number of campaign activities in which a respondent had engaged or was very likely to engage—none, one, or more than one. Strength of attachment to the Democratic Party led to campaign activism, as did a more positive assessment of President Biden. Believing that one had a good understanding of American politics also prompted involvement. In contrast to much of the literature on party activism in the United States and other democracies, education level and age did not predict transnational involvement in Democratic Party campaigns. This lack of significance likely is due in part to the limited variation for these items; respondents tended to be well educated and older. As expected, the mobilizing effect of contacts with partisan organizations from the United States had a highly significant effect as well, much as it would for partisans within the United States (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995).

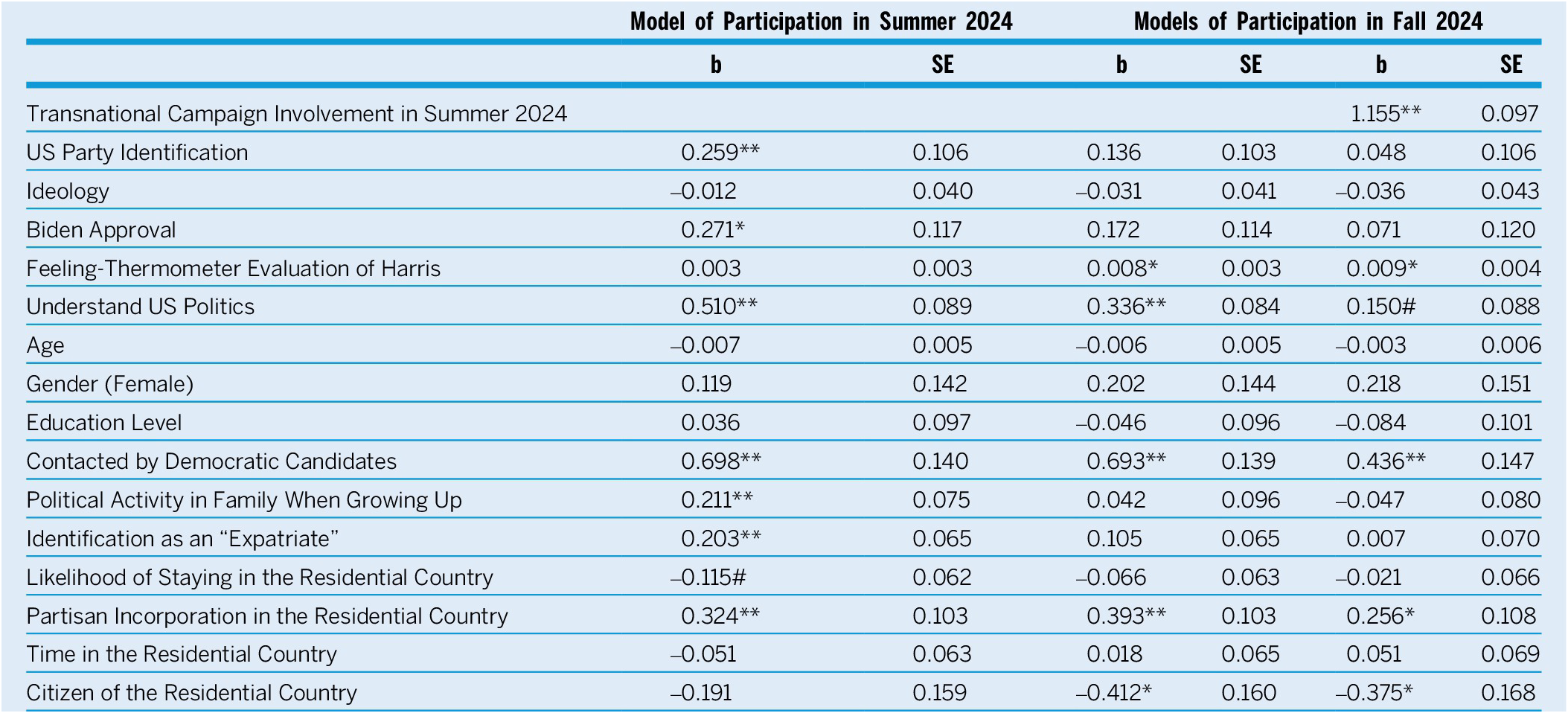

Table 1 Ordered Logistic Regression Models of Transnational Campaign Participation

Notes: In each model, the dependent variable is a three-point ordinal indicator of transnational campaign involvement (0=no activities; 1=one activity; 2=two or more activities). #=p<0.10; *=p<0.05; **=p<0.01. Cut points are not reported for ease of presentation.

Considering the items on incorporation in the settlement country, a mixed pattern of effects emerges. There is evidence that becoming a citizen of the country limits involvement in American campaigns, whereas seeing oneself as an emigrant significantly predicts participation (Staton, Jackson, and Canache Reference Staton, Jackson and Canache2007). At the same time, we found a strong and significant positive effect of integration into the party system of the residential country; partisanship in this context shapes transnational campaigning. For Democrats living outside of the United States, there clearly is no tension between partisan incorporation as an immigrant versus an emigrant.

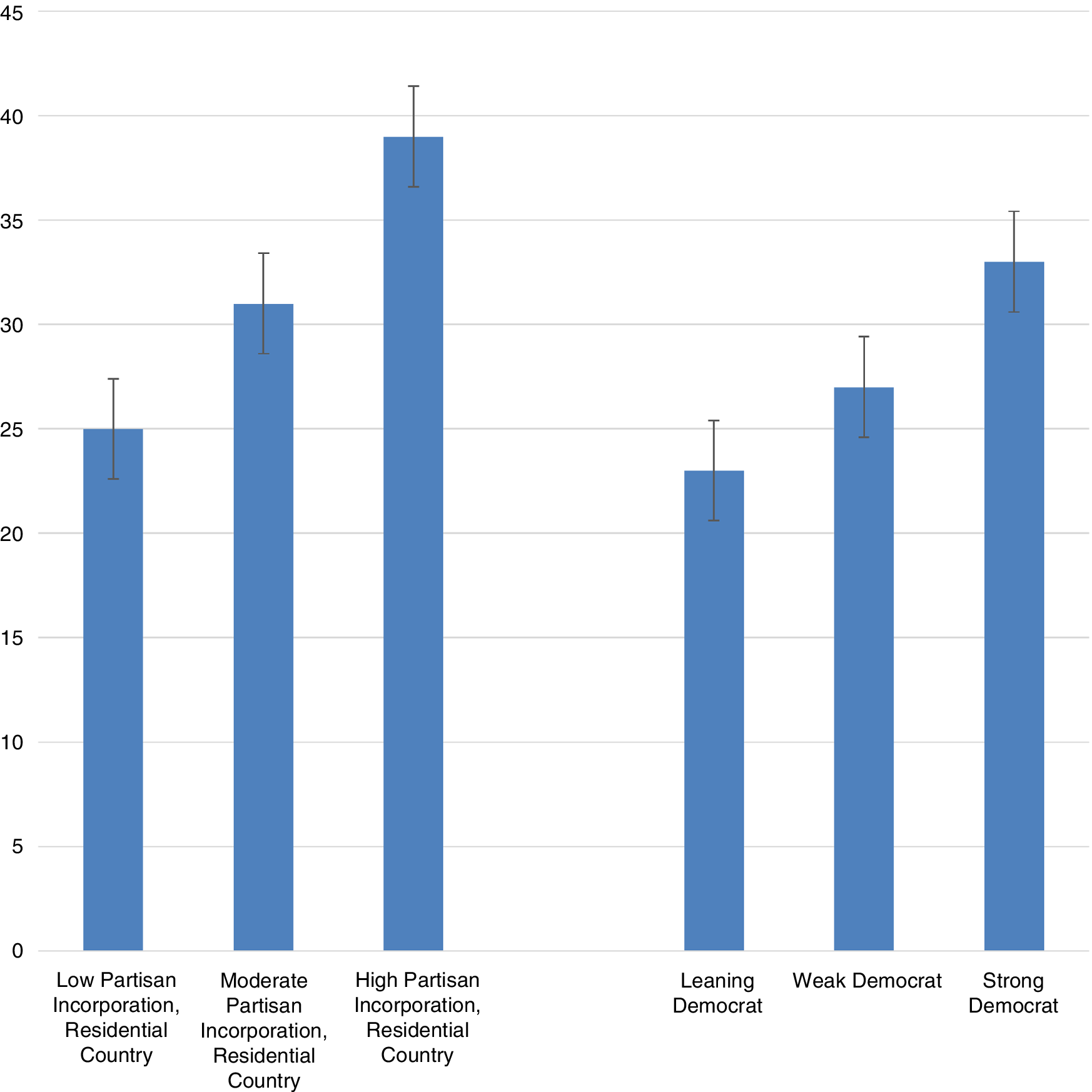

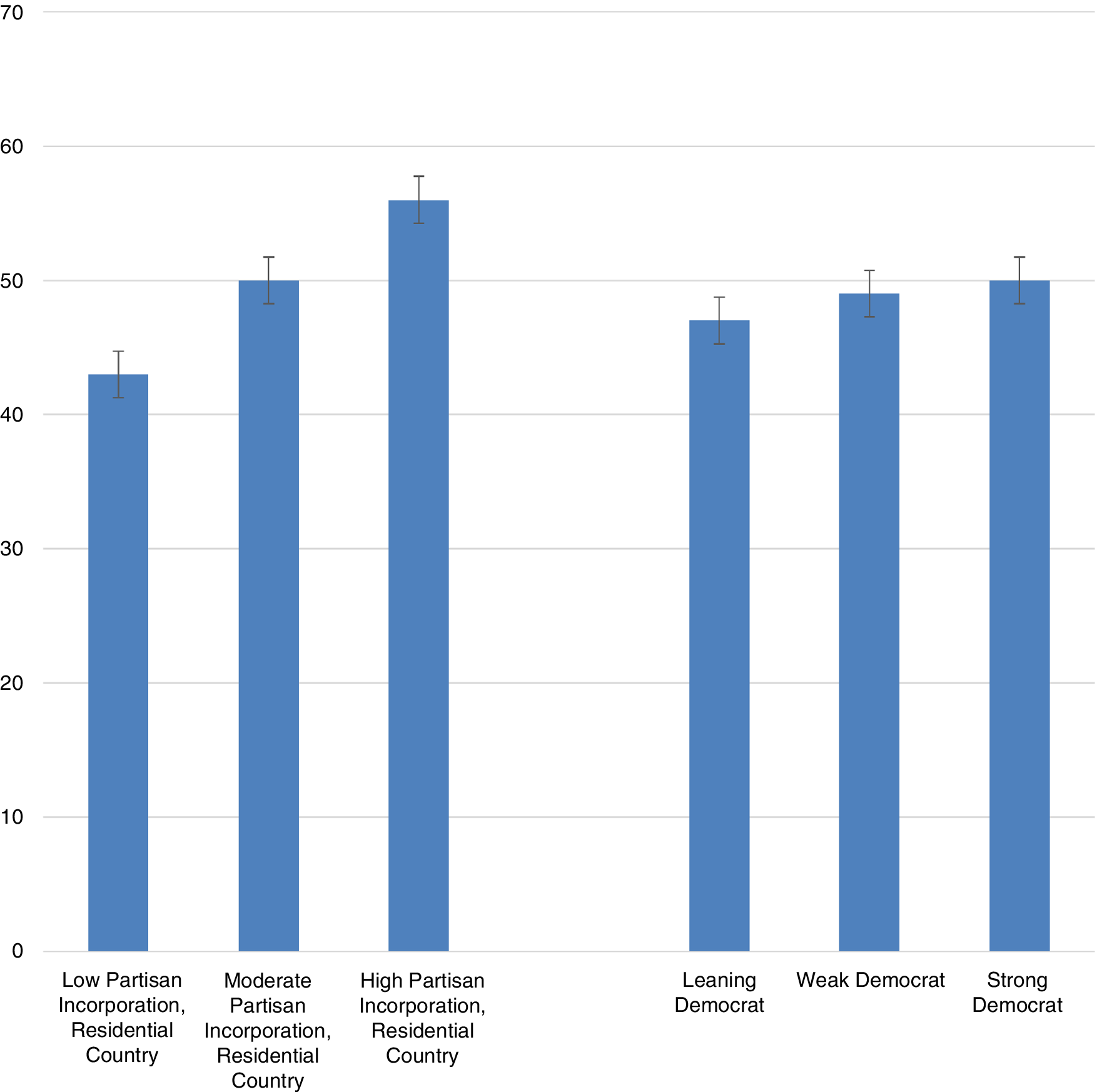

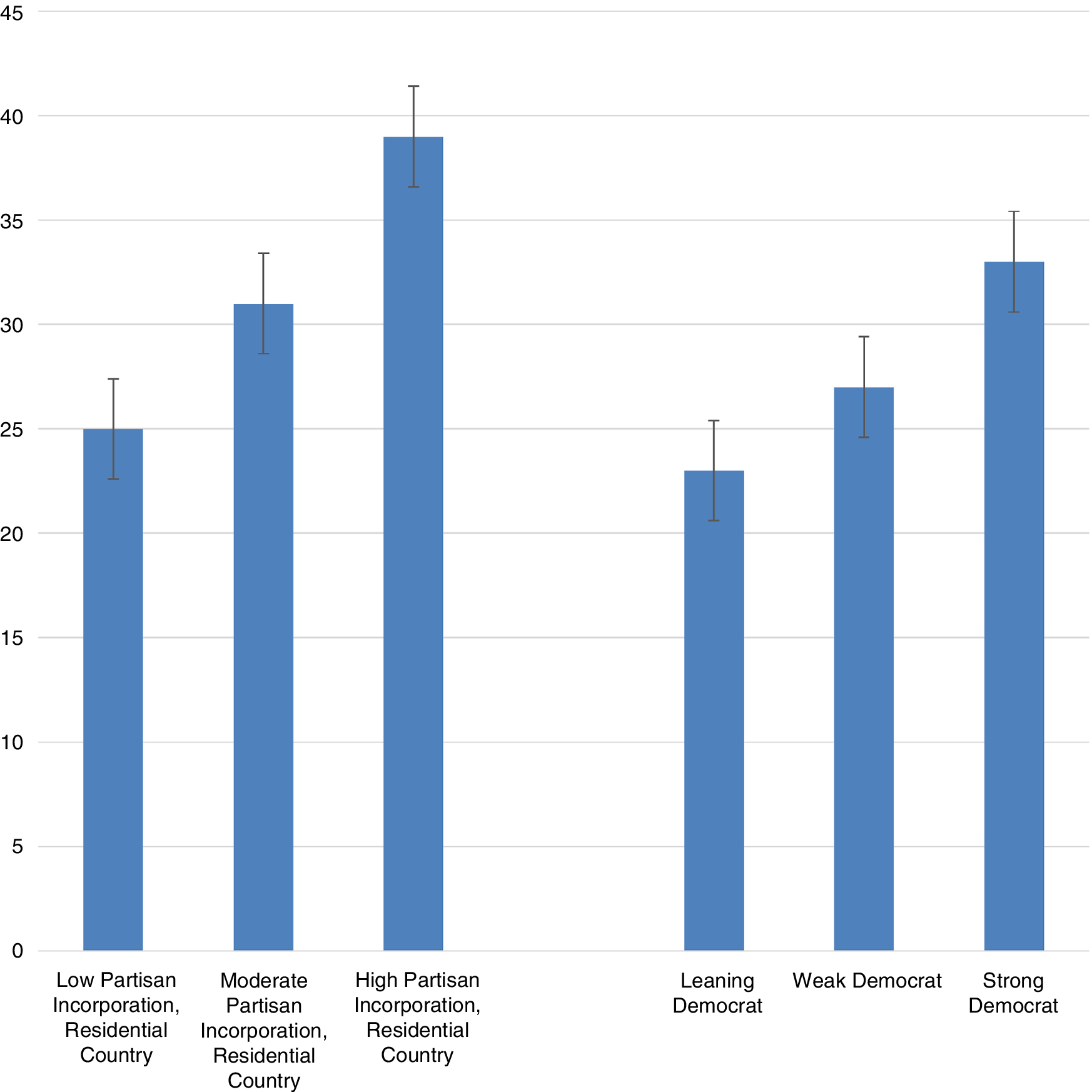

Figure 3 illustrates the effect of partisanship in the settlement country on the probability of being highly engaged in American campaigns during the summer of 2024. After controlling for all of the other predictors in the model, the estimated probability of participating in two or more activities was 0.25 for Democrats who did not identify with a party in their residential country and had not attended local party meetings. This estimate increased to almost 0.40 for overseas Democrats who were highly integrated into the political party system where they live. To benchmark the effect of partisan incorporation in the receiving country, figure 3 also presents predicted probabilities of summertime campaign activism categorized by the level of identification with the Democratic Party. As expected given the positive and significant coefficient for party identification in the regression model, strong Democrats were appreciably more likely to report a high level of activism relative to weak identifiers and leaners. Yet, this trajectory of predicted probabilities is slightly less steep compared to that for partisan incorporation in the country of residence. Integration into a party system abroad emerged as one of the strongest predictors of transnational activist participation.

Figure 3 Predicted Probability of a High Level of Transnational Campaign Activism in Summer 2024, by Level of Partisan Incorporation in the Residential Country and Strength of Democratic Party Identification

Predicted probabilities for scoring “2” on the dependent variable are estimated based on the ordered logistic regression model in table 1 (first column). When calculating a given probability, all other predictors in the model were fixed to their respective mean value. Respondents who neither identified with a party in the residential country nor had attended a local party meeting were placed in the “low partisan incorporation” category; those who either identified with a party or had attended a meeting were in the “moderate” category; and those who both identified with a party and had attended partisan meetings were in the “high” category.

The second set of findings in table 1 shows the effects of these predictors on engagement in transnational campaign politics as measured in the October 2024 survey wave. The logistic regression coefficients in this case were somewhat different than the first model, reflecting the major shift in the mobilization climate at that time. With Harris leading the ticket, the effects of Biden’s approval ratings and party identification were diminished, and feeling-thermometer evaluations of Harris became a more relevant conduit for campaign engagement. Respondents’ confidence that they could understand American politics continued to shape activism in this second-wave survey as did contacts with Democratic Party campaign organizations. This model also shows the continued impact that incorporation in a residential country can have on transnational activism. Democrats who had become dual nationals evidenced somewhat less activity as measured in the fall survey wave (p<0.05) (cf. Staton, Jackson, and Canache Reference Staton, Jackson and Canache2007). At the same time, incorporation into the party system of that country continued to have a highly significant positive effect (p<0.01).

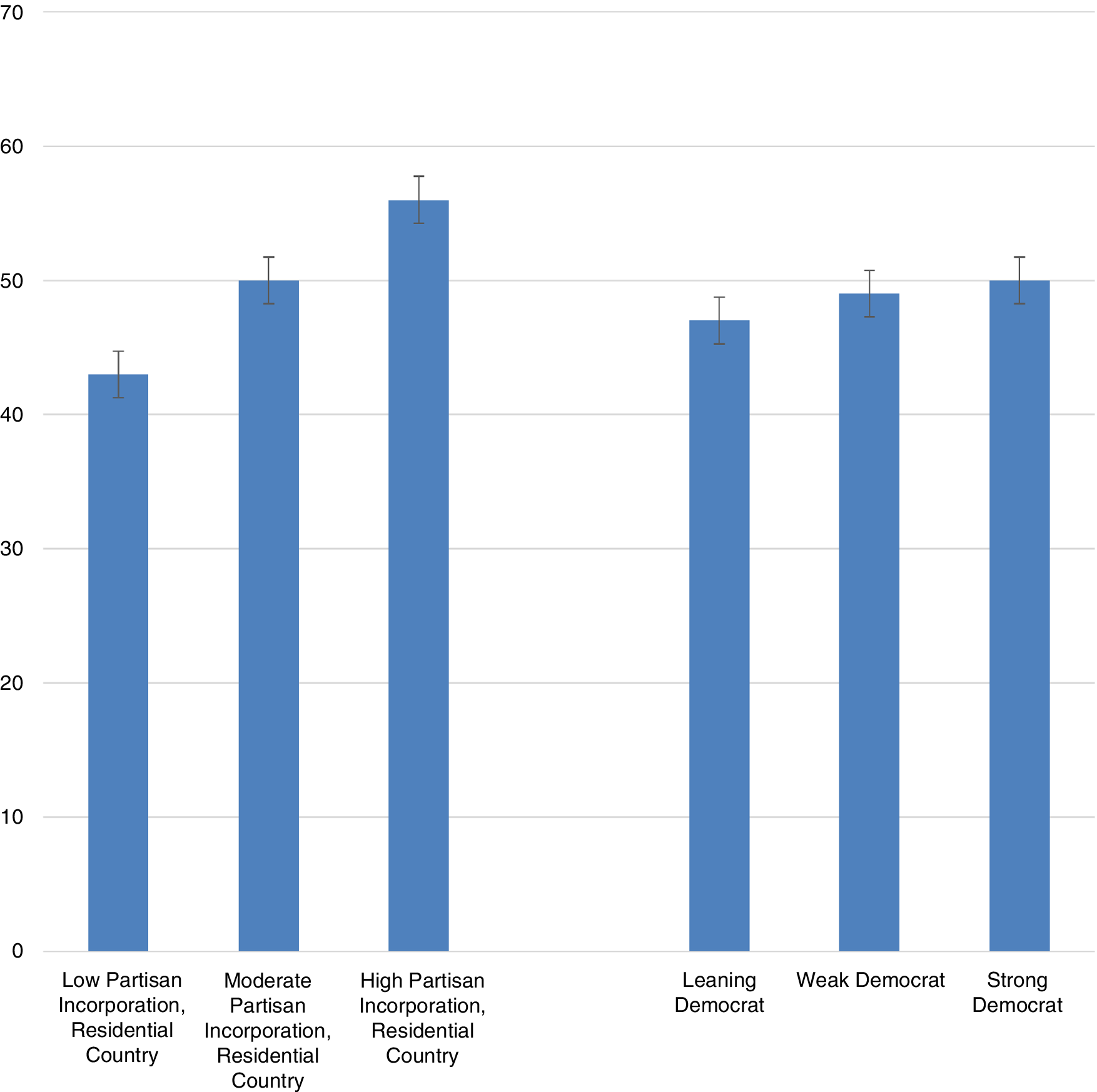

The third model in table 1 includes the measure of campaign involvement from the first-wave survey as a predictor. Including this item made the specification dynamic and allowed for firmer causal inferences (Prior Reference Prior2018, ch. 9). The coefficients for the other predictors indicate how those variables prompted increases in campaign involvement between periods. Evaluations of Harris remain significant in this model, as does the level of confidence in understanding US politics. The impact of partisan incorporation in the residential country is evident as well, and dual nationals are shown to have participated less relative to Democrats whose citizenship was solely with the United States. To clarify the effects of partisanship in both the domestic and emigrant contexts at this stage in the 2024 campaign, figure 4 presents predicted probabilities of active campaign involvement.Footnote 6

Figure 4 Predicted Probability of a High Level of Transnational Campaign Activism in Fall 2024, by Level of Partisan Incorporation in the Residential Country and Strength of Democratic Party Identification

Predicted probabilities for scoring “2” on the dependent variable are estimated based on the ordered logistic regression model in table 1 (third column). When calculating a given probability, all other predictors in the model were fixed to their respective mean value.

After controlling for the other predictors in the model, Americans living abroad who had not become connected to a party in the settlement country had a probability of 0.43 of participating in the US elections in two or more ways. This probability increased to 0.56 among those who identified with a political party abroad and had attended a local partisan meeting. In contrast to this significant difference, the degree to which a respondent identified as a Democrat mattered relatively little in shaping engagement at this stage of the campaign.

CONCLUSION

The United States has long been considered a nation of immigrants. With approximately 51 million foreign-born residents currently living in the country (Kramer and Passel Reference Kramer and Passel2025), this label aptly applies. At the same time, the United States is a nation of emigrants. Although the exact number of Americans living outside of the territorial boundaries of the country is not known, reasonable estimates suggest that 4 million to 5 million citizens reside abroad—a number that is larger than the population of 20 or more American states (Federal Voting Assistance Program 2023). These citizens retain the right to vote in federal-level US elections in perpetuity.

Compared to the voluminous scholarly literature on voter turnout in the United States, relatively little is known about the factors that prompt overseas Americans to vote by absentee ballot. We know even less about transnational partisan campaign activism: who takes part, the types of activities that take place from the distance, and how political incorporation where someone has settled shapes involvement in American campaigns. Findings from this first-ever panel survey of Democratic partisans living abroad suggest that some of the forces that shape campaign activism in the United States hold overseas.

Findings from this first-ever panel survey of Democratic partisans living abroad suggest that some of the forces that shape campaign activism in the United States hold overseas.

Democrats who strongly identify with the party, feel confident in their understanding of American politics, have favorable impressions of party leaders, grew up in households that were politically active, and are in contact with party organizers are much more likely to participate remotely in US campaigns—at least in the early stage of a campaign. The same generally can be said about Democratic partisans within the United States (Rapoport, Abramowitz, and McGlennon Reference Rapoport, Abramowitz and McGlennon1986). The Democratic partisans who participated in this study, however, were responsive to the changing political climate during the course of the 2024 election cycle. In the later phase of the campaign, following President Biden’s disastrous debate performance and the placement of Vice President Harris at the top of the ticket, personal appraisals of the new nominee became significant predictors of transnational engagement, overshadowing presidential approval and partisan identification, among other predictors.

This study contributes to the literature on political transnationalism with our focus on Americans living abroad—a migrant population that has received little previous attention—from a home-country perspective. We find that becoming a citizen of the residential country has a dampening effect on US political engagement. Conversely, we also find a positive correlation between home-country and residential-country political engagement, with greater campaign involvement in the United States predicted by integration into the residential-country political system. This result comports with prior research on party activism in the United States that shows that political participation in one context (e.g., a nomination-stage presidential campaign) can spur activists toward further involvement in subsequent campaigns (e.g., congressional campaigns) (McCann et al. Reference McCann, Partin, Rapoport and Stone1996). Moreover, our analysis extends this dynamic far beyond the territorial boundaries of the United States. Following previous studies of the political transnationalism of migrants, we find that there is no inherent conflict between integration into a political party system as an immigrant and remaining engaged in partisan campaigns as an emigrant (Tsuda Reference Tsuda2012; Van Haute and Kernalegenn Reference Van Haute and Kernalegenn2021). Our evidence instead suggests that the two modes of partisan engagement—political integration in a country of residence and political transnational engagement in the home country—can be complementary.

…there is no inherent conflict between integration into a political party system as an immigrant and remaining engaged in partisan campaigns as an emigrant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096525101728.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JNETFS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Betina Cutaia Wilkinson and two anonymous readers for helpful feedback.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.