Introduction

The study of political (in)equality plays a central role in political science. A core democratic principle is that the preferences of each citizen will be given equal weight when political decisions are made (e.g., Dahl, Reference Dahl1989). Thus, it is critically important to understand whether that ideal is being met. Since political engagement is how citizens communicate their preferences to political leaders, it is not surprising that scholars have devoted considerable attention to potential inequalities in political participation (Leighley & Nagler, Reference Leighley and Nagler2013; Schlozman, Verba, & Brady, Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012; Verba, Schlozman, & Brady, Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). A long-standing body of research has focused on the impact of parents on the political habits of their children. Studies in the realm of political socialization consistently show that children who have politically engaged parents tend to be much more active in politics when they grow up than those whose parents were not engaged in political life (Beck & Jennings, Reference Beck and Jennings1982; Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1981; Jennings, Stoker, & Bowers, Reference Jennings, Stoker and Bowers2009; Kudrnáč & Lyons, Reference Kudrnáč and Lyons2017; McIntosh, Hart, & Youniss, Reference McIntosh, Hart and Youniss2007; Plutzer, Reference Plutzer2002).Footnote 1 It is important to note that parents can influence the political habits of their children through other pathways as well. Much research, for example, has shown that political engagement is partly heritable (Dawes, Settle, Loewen, McGue, & Iacono, Reference Dawes, Settle, Loewen, McGue and Iacono2015; Fowler, Baker, & Dawes, Reference Fowler, Baker and Dawes2008; Klemmensen et al., Reference Klemmensen, Hatemi, Hobolt, Petersen, Skytthe and Nørgaard2012; Weinschenk, Dawes, Kandler, Bell, & Riemann, Reference Weinschenk, Dawes, Kandler, Bell and Riemann2019; Weinschenk, Dawes, Klemmensen, & Rasmussen, Reference Weinschenk, Dawes, Klemmensen and Rasmussen2023). In short, advantages or disadvantages in political engagement can be influenced by factors that occur both before and after birth. One important implication of these lines of research is that political (dis)advantages that occur in one generation can be passed on to future generations. As Oskarsson, Ahlskog, Dawes, and Lindgren (Reference Oskarsson, Ahlskog, Dawes and Lindgren2022) note, “To be able to take effective measures to combat the reproduction of political inequality across generations, we must first have a good understanding of its underpinnings. Different sources of intergenerational persistence can require very different types of actions” (1337).

Scholars are only just starting to understand how pre- and post-birth factors come together to generate parent–child similarity in political behavior. To date, much of the work on the pre- and post-birth transmission of political behavior has focused on voter turnout and has made use of adoption studies. As a quick overview, adoption studies are a useful tool for separating out the genetic and social influences on an outcome of interest. Such studies leverage the fact that in adoptive families, children are raised in a different environment than they were born and are biologically unrelated to their adoptive parents. Thus, adoption studies help address the fact that genetic and social factors would be confounded if a researcher focused only on children who were raised by their birth parents (i.e., since such parents transmit a rearing environment and genes to their children). In the context of political engagement, Cesarini, Johannesson and Oskarsson (Reference Cesarini, Johannesson and Oskarsson2014) used data from a sample of Swedish adoptees, their adoptive parents, and their biological parents to examine the influence of pre- (measured by biological parents’ voting) and post-birth (measured by adoptive parents’ voting) factors on voter turnout. They found that both social and genetic mechanisms contribute to the parent–child resemblance in turnout. According to Cesarini, Johannesson, and Oskarsson (Reference Cesarini, Johannesson and Oskarsson2014)), “despite the fact that all formal ties between biological parents and adoptees were cut at adoption, and that a large majority of the children in the sample have no information about their biological parents…the voting behavior of adoptees around the age of 40 can still be predicted by the voting behavior of their biological parents” (14). In a follow-up study, Oskarsson et al. (Reference Oskarsson, Ahlskog, Dawes and Lindgren2022) also found that both pre-birth factors and post-birth socialization factors play a role in the intergenerational transmission of voter turnout. Interestingly, they found that the effect of post-birth factors, such as parental socialization, is approximately twice the size of the effect of pre-birth factors (i.e., genes and the prenatal environment). Some scholars have also examined whether pre- and post-birth factors influence the propensity to run for office. Using an adoption study, Oskarsson, Dawes, and Lindgren (Reference Oskarsson, Dawes and Lindgren2018)) found that both post-birth, measured by adoptive parents’ tendency to run for office, and pre-birth factors, measured by biological parents’ tendency to run for office, were important predictors of standing as a candidate, and the effects were roughly equal in size.

Although the studies outlined earlier have shed important light on the ways in which some political activities can be transmitted across generations, it is unclear how much of a role pre- and post-birth factors play in the transmission of other acts of political engagement. While voting and running for office are important political activities, they are among the most and least common political acts that people engage in, respectively.Footnote 2 Although the research highlighted above indicates that these acts are influenced by factors that occur both before and after birth, it is important to understand the role of pre- and post-birth factors in shaping the propensity to engage in the wide range of other types of political activities that exist.

The rest of this paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, we provide an overview of our data, measures, and methodological approach. As a brief overview, we make use of the sibling interaction and behavior study (SIBS), which was gathered by the Minnesota Center for Twin and Family Research. SIBS is a study of adoptive and biological children and their parents and recently asked participants a series of questions about participation in various political activities. By examining the impact of parental political engagement on the political engagement of adoptees and nonadopted children, we are able to get a sense of the role of pre-birth factors (i.e., the impact of parent participation on the participation of their biological children) and post-birth factors (i.e., the impact of parental participation on the participation of their adopted children) in shaping political engagement. Next, we turn to an overview of our results. As a quick preview, we find that in our sample, pre-birth factors seem to have a more pronounced impact on political engagement than post-birth factors. We conclude with ideas for future research.

Data and method

The SIBS is a study of adoptive and biological siblings and their parents. Participating families were originally recruited and assessed through the SIBS between 1998 and 2004 (McGue et al., Reference McGue, Keyes, Sharma, Elkins, Legrand, Johnson and Iacono2007). A representative sample of adoptive and biological families were identified from records of large adoption agencies and state birth records. Study eligibility was limited to families composed of at least one parent and two adolescent offspring within 5 years of one another in age (mean age of offspring at the first assessment = 14.9 years, SD = 1.6) and to families living within driving distance of the Twin Cities research laboratory. Additionally, adopted adolescent offspring were required to have been placed for adoption prior to turning 2 years old (M = 4.7 months, SD = 3.4 months). After parents were interviewed to establish eligibility, a majority of families agreed to participate (63% of the adoptive families and 57% of the biological families). The SIBS sample has been followed up every three to four years. In the most recent follow-up (the sixth SIBS follow-up), the study asked parents and their children (now in adulthood) a number of questions about political engagement. We use the following questions to measure political engagement: (1) I believe it is every citizen’s responsibility to stay politically informed and vote (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” 1–5 scale where higher indicates more agreement), (2) I voted in local and national elections (“never” to “always,” 1–5 scale where higher indicates more engagement), (3) I have contacted a local or national politician to encourage their support on an issue of importance to me (“never” to “always,” 1–5 scale where higher indicates more engagement), and (4) I have attended a town hall or city council meeting in my community (“never” to “always,” 1–5 scale where higher indicates more engagement). There are a few things to note about our measures. First, although item one captures an attitude rather than a political act, we believe that it is worthwhile to include in this study since it focuses on political engagement. Second, although, as we noted earlier, several previous studies have focused on voter turnout, we include this measure because it allows us to compare our findings to past studies (e.g., Cesarini et al., Reference Cesarini, Johannesson and Oskarsson2014; Oskarsson et al., Reference Oskarsson, Ahlskog, Dawes and Lindgren2022) to see if results are similar across different samples.

We follow Oskarsson et al. (Reference Oskarsson, Ahlskog, Dawes and Lindgren2022) and use a very simple method to assess the impact of pre- and post-birth factors on political engagement. This approach can be represented by the following regression model:

where superscripts c and p denote the child and parent, respectively,

![]() $ {y}_j^c $

is the child’s self-reported political engagement (estimated separately for voting, staying informed, contacting politicians, and attending community meetings),

$ {y}_j^c $

is the child’s self-reported political engagement (estimated separately for voting, staying informed, contacting politicians, and attending community meetings),

![]() $ {Bio}_j^c $

is an indicator variable equal to 1 if a child was raised by their biological parents and 0 if they are adopted,

$ {Bio}_j^c $

is an indicator variable equal to 1 if a child was raised by their biological parents and 0 if they are adopted,

![]() $ {y}_j^p $

is an average of the parents’ self-reported political engagement for the same mode of political participation, and

$ {y}_j^p $

is an average of the parents’ self-reported political engagement for the same mode of political participation, and

![]() $ {Bio}_j^c\times {y}_j^p $

is the interaction between parent type (adoptive or biological) and parental participation. In this interaction model,

$ {Bio}_j^c\times {y}_j^p $

is the interaction between parent type (adoptive or biological) and parental participation. In this interaction model,

![]() $ {\beta}_2 $

represents the transmission of political engagement among adoptive families, directly estimating the post-birth effect, and

$ {\beta}_2 $

represents the transmission of political engagement among adoptive families, directly estimating the post-birth effect, and

![]() $ {\beta}_3 $

represents the difference in transmission rates among adoptive and biological families, which is an indirect estimate of the pre-birth effect.Footnote 3 We include in all models fixed effects for child birth year, sex (coded 1 for male and 0 for female), and parental birth year (since we are using the average of mother and father political engagement for our parental political engagement measure, we calculate parental birth year as simply the average of parent birth years).Footnote 4 Standard errors are clustered by family.

$ {\beta}_3 $

represents the difference in transmission rates among adoptive and biological families, which is an indirect estimate of the pre-birth effect.Footnote 3 We include in all models fixed effects for child birth year, sex (coded 1 for male and 0 for female), and parental birth year (since we are using the average of mother and father political engagement for our parental political engagement measure, we calculate parental birth year as simply the average of parent birth years).Footnote 4 Standard errors are clustered by family.

There are three primary assumptions that are required to interpret

![]() $ {\beta}_2 $

and

$ {\beta}_2 $

and

![]() $ {\beta}_3 $

as measures of the pre- and post-birth effects (Cesarini et al., Reference Cesarini, Johannesson and Oskarsson2014; Oskarsson et al., Reference Oskarsson, Dawes and Lindgren2018; Oskarsson et al., Reference Oskarsson, Ahlskog, Dawes and Lindgren2022). The first is that adopted children are placed with their adoptive parents at birth. While this is not the case for our sample, to be eligible to participate in SIBS, children had to be placed in their adoptive home before the age of two and the sample average is 4.7 months of age (SD 3.4 months) (McGue et al., Reference McGue, Keyes, Sharma, Elkins, Legrand, Johnson and Iacono2007). The second and third assumptions require that adoptees are randomly assigned to families and that adoptees have no contact with, or information about, their biological parents. If Minnesota adoptions agencies placed children into adoptive homes based on similarities between biological and adoptive parents (e.g., placing children of politically active parents into politically active adoptive homes), it could lead to upward bias in the post-birth estimate. In contrast, if SIBS adoptees had knowledge of their biological parents’ civic and political engagement, it could lead to an upward bias in the pre-birth effect. While we are not able to know the placement process Minnesota adoption agencies followed and lack any information about biological parents of the adopted children that could be used to test for nonrandom placement based on observable factors, SIBS adoptees tended to be international placements with limited information regarding their birth background (McGue et al., Reference McGue, Keyes, Sharma, Elkins, Legrand, Johnson and Iacono2007). This would make it difficult for adoption agencies to engage in selective placement and also makes it unlikely that SIBS adoptees were knowledgable of their biological parents’ civic and political engagement.Footnote 5

$ {\beta}_3 $

as measures of the pre- and post-birth effects (Cesarini et al., Reference Cesarini, Johannesson and Oskarsson2014; Oskarsson et al., Reference Oskarsson, Dawes and Lindgren2018; Oskarsson et al., Reference Oskarsson, Ahlskog, Dawes and Lindgren2022). The first is that adopted children are placed with their adoptive parents at birth. While this is not the case for our sample, to be eligible to participate in SIBS, children had to be placed in their adoptive home before the age of two and the sample average is 4.7 months of age (SD 3.4 months) (McGue et al., Reference McGue, Keyes, Sharma, Elkins, Legrand, Johnson and Iacono2007). The second and third assumptions require that adoptees are randomly assigned to families and that adoptees have no contact with, or information about, their biological parents. If Minnesota adoptions agencies placed children into adoptive homes based on similarities between biological and adoptive parents (e.g., placing children of politically active parents into politically active adoptive homes), it could lead to upward bias in the post-birth estimate. In contrast, if SIBS adoptees had knowledge of their biological parents’ civic and political engagement, it could lead to an upward bias in the pre-birth effect. While we are not able to know the placement process Minnesota adoption agencies followed and lack any information about biological parents of the adopted children that could be used to test for nonrandom placement based on observable factors, SIBS adoptees tended to be international placements with limited information regarding their birth background (McGue et al., Reference McGue, Keyes, Sharma, Elkins, Legrand, Johnson and Iacono2007). This would make it difficult for adoption agencies to engage in selective placement and also makes it unlikely that SIBS adoptees were knowledgable of their biological parents’ civic and political engagement.Footnote 5

Results

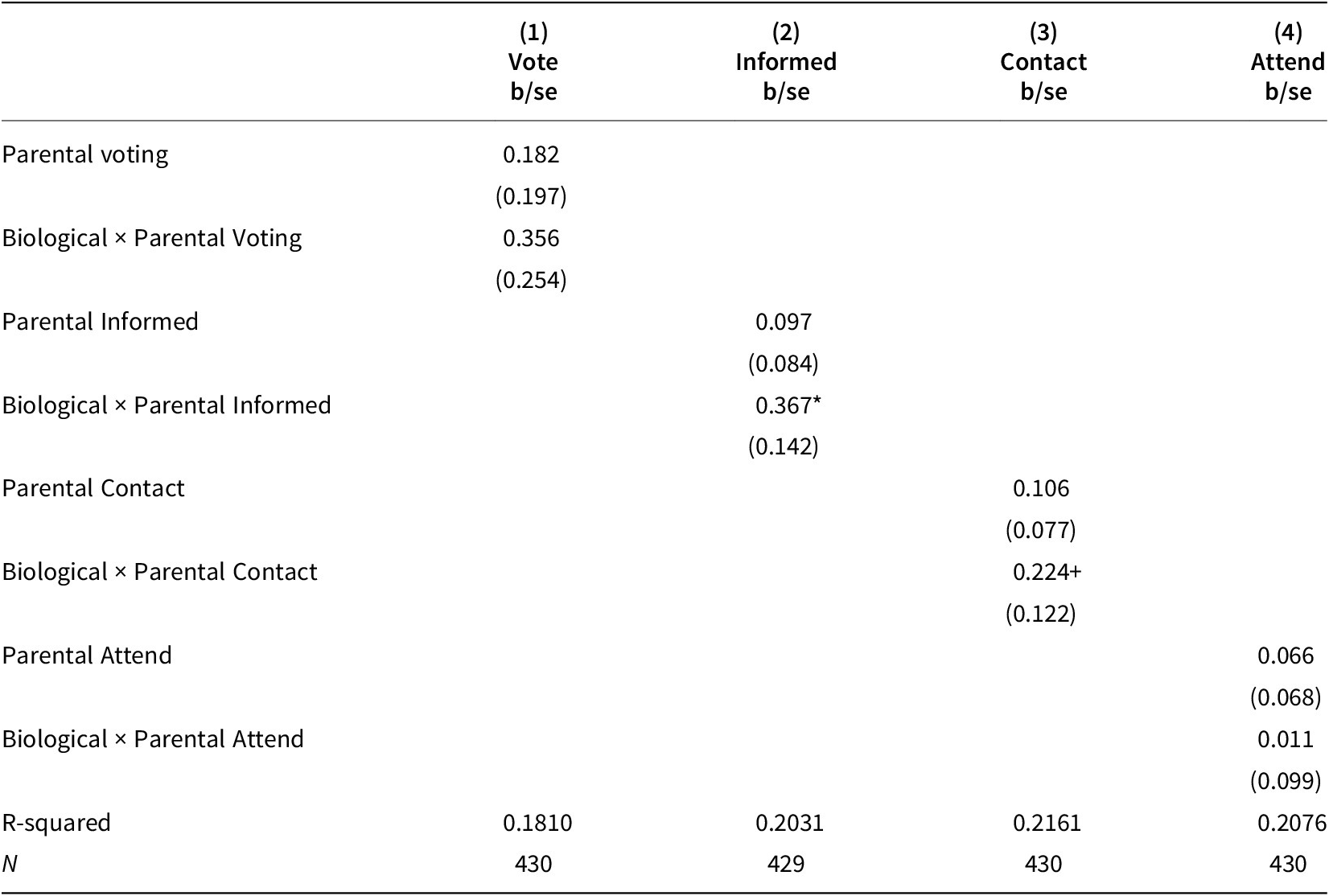

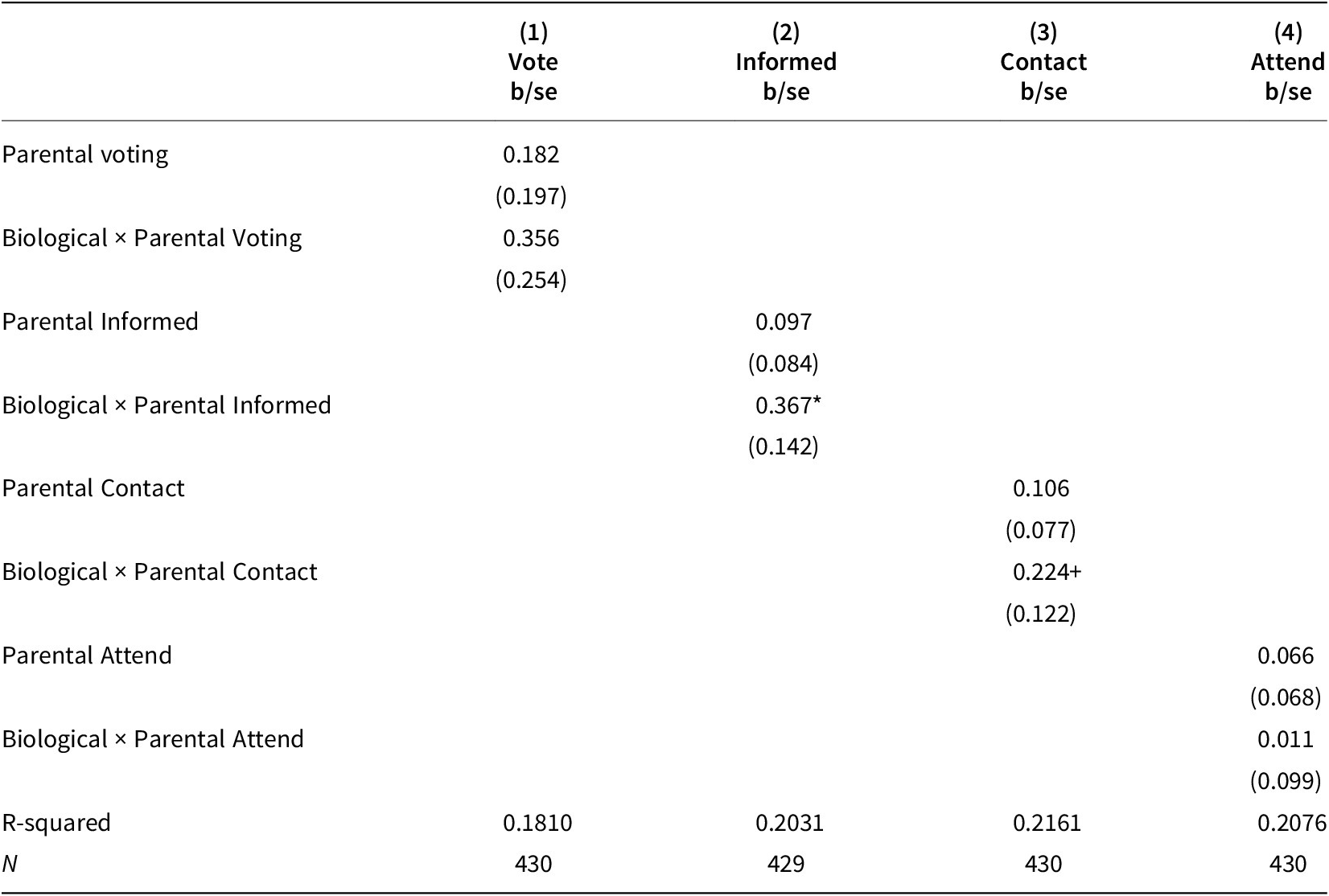

The results from our regression models are shown in Table 1 and presented in Figure 1. Turning first to the self-reported measure of voter turnout, we see that the coefficient on parental turnout, which is a direct estimate of the effect of post-birth factors, is not statistically significant. The coefficient on the interaction represents an indirect estimate of the effect of pre-birth factors (i.e., it captures the difference between the overall transmission rate and the effect of post-birth factors). Here, we see that the interaction is positively signed but not statistically significant effect. As we noted earlier, since voter turnout has been used as a dependent variable in several previous studies, we are able to compare our results to past findings. Analyzing a large sample of Swedish adoptees and their adoptive as well as biological parents, Cesarini et al. (Reference Cesarini, Johannesson and Oskarsson2014)) found that both pre- and post-birth factors accounted for a large and approximately equal share of the parent–child resemblance in validated voter turnout in a single national election. Based on a similar Swedish sample, Oskarsson et al. (Reference Oskarsson, Ahlskog, Dawes and Lindgren2022) reported that while both pre-and post-birth factors matter in shaping validated voting in three Swedish national elections, the effect of post-birth factors was about twice the size of the effects of pre-birth factors.Footnote 6 It is not immediately clear to us why the influence of pre- and post-birth effects would vary across different samples (and contexts), but we believe that this is something worth paying attention to as more adoption studies on political engagement emerge. There has been some evidence that biological influences vary considerably across political contexts (e.g., Fazekas & Littvay, Reference Fazekas and Littvay2015), so it is quite possible that pre- and post-birth effects will be of different magnitudes across, for example, countries.

Table 1. Pre- and post-birth factors and political engagement

Notes: +p

![]() $ \le $

0.10, *p

$ \le $

0.10, *p

![]() $ \le $

0.05, two-tailed.

$ \le $

0.05, two-tailed.

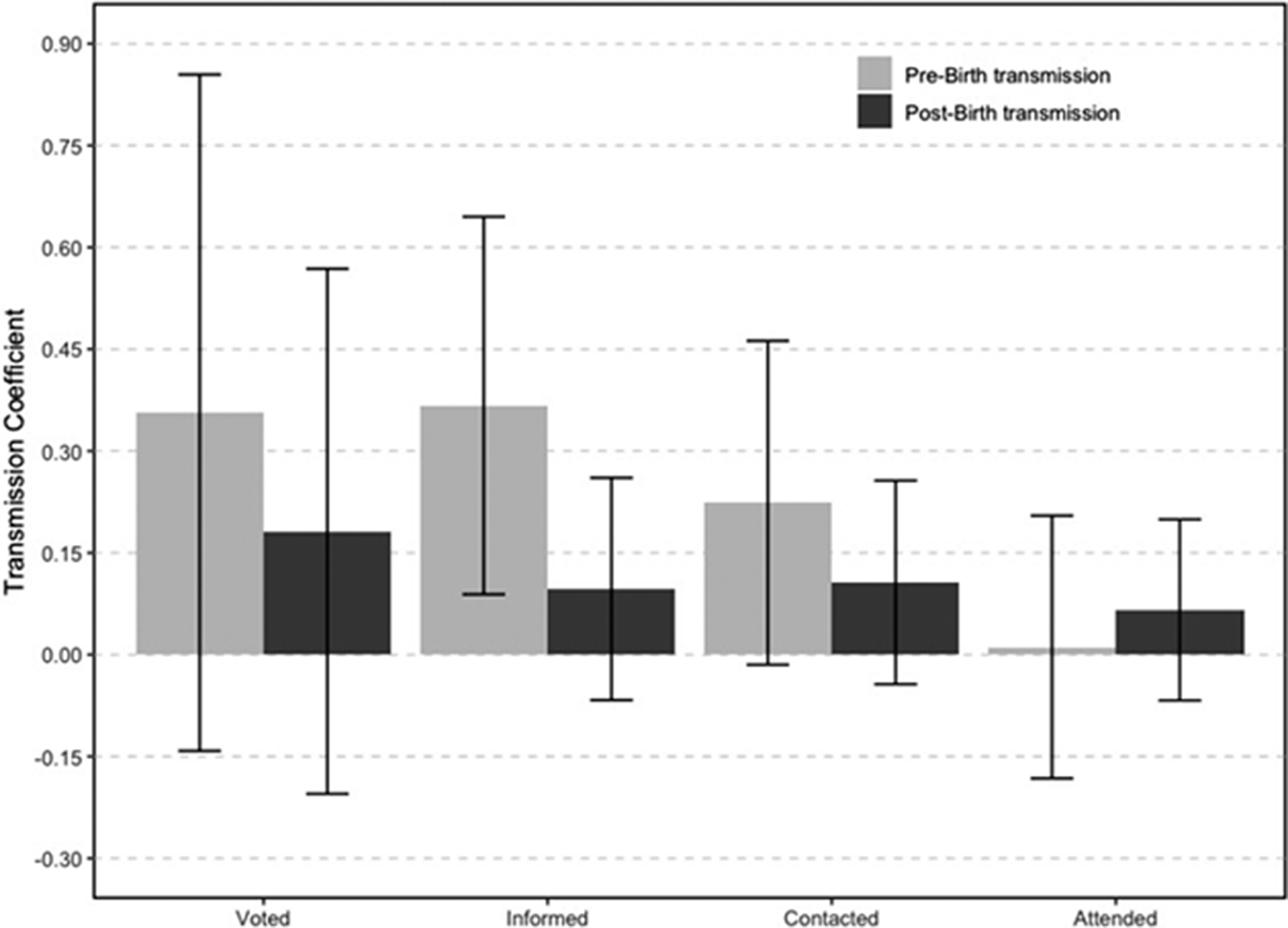

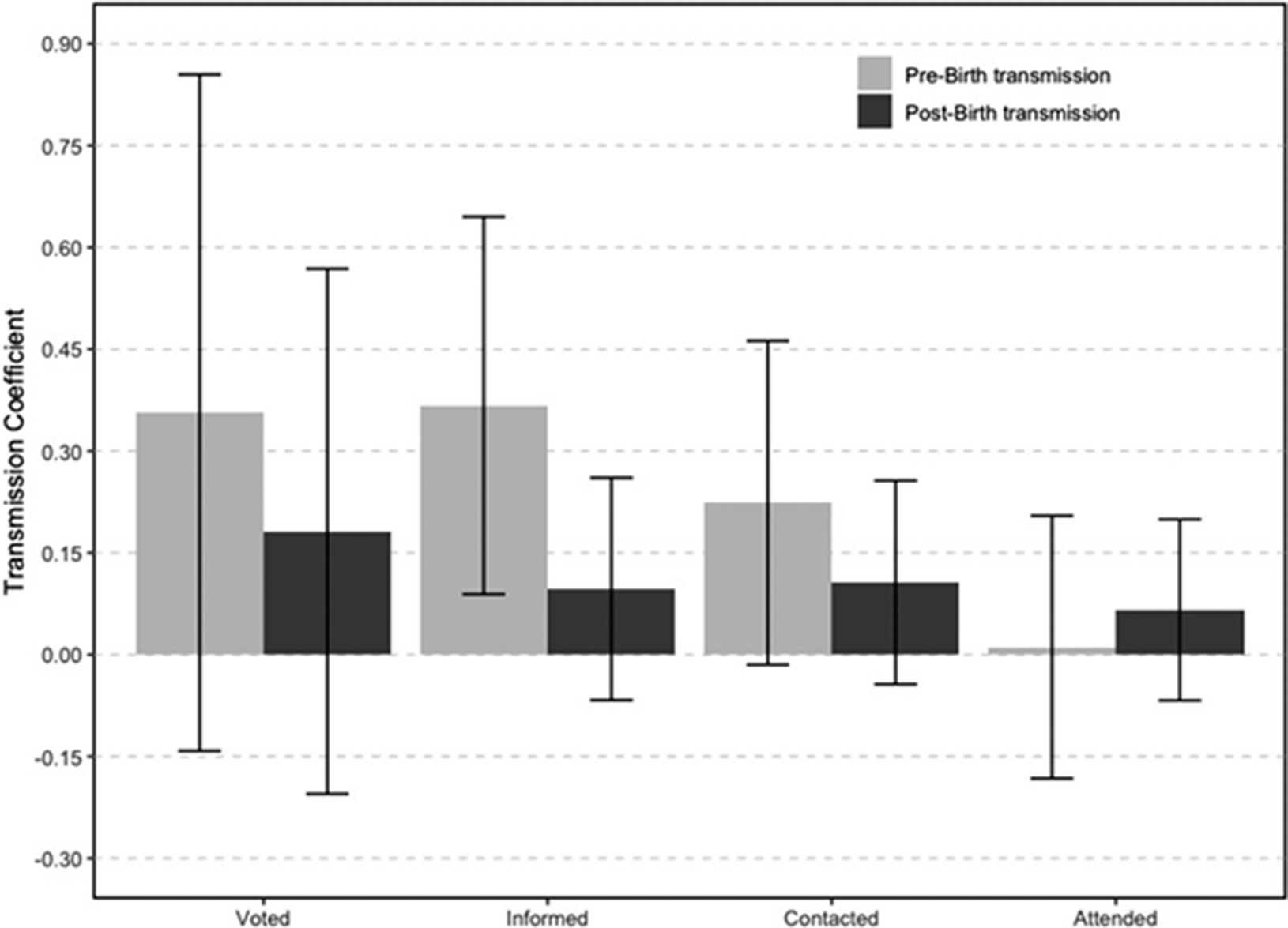

Figure 1. Pre- and post-birth transmission coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (from two-tailed t-tests).

In Model 2, we examine the impact of pre- and post-birth factors on our measure of the extent to which the children in our sample believe it is every citizen’s responsibility to stay politically informed and vote. Overall, the coefficient on the parental measure is not statistically significant. Thus, post-birth factors do not seem to play an important role in shaping attitudes about civic responsibility. On the other hand, the interaction coefficient is statistically significant at the 5% level, and it is positively signed. Thus, pre-birth factors seem to influence beliefs about civic responsibilities. The results in Model 3 mirror those in Model 2. Again, we see that the coefficient on the parental measure is not statistically significant at conventional levels, which indicates that post-birth factors are not important in predicting a child’s propensity to contact politicians about issues of importance. When it comes to pre-birth factors, however, we see that there is a statistically significant effect (at the 0.10 level). The final model in Table 1 shows the impact of pre- and post-birth factors on attending government meetings. Here, we see that both pre- and post-birth factors are positively related to the dependent variable, but neither are statistically significant at conventional levels.

Since our sample is a relatively small, our transmission coefficient estimates are too noisy to definitively establish that pre-birth effects are larger than post-birth effects (at conventional levels of significance). However, we find much larger pre-birth effects for 3 of the 4 measures of political participation (self-reported voting, the belief that citizens should stay informed in order to vote, and self-reported contact with elected officials), which is an interesting pattern and one that should be examined in future studies.Footnote 7. Although we can only speculate at this point (given the small sample size here), the fact that our sample is in their 30s, on average, could perhaps help explain the shift from post-birth to pre-birth influence over the lifespan. In work by Oskarsson et al. (Reference Oskarsson, Ahlskog, Dawes and Lindgren2022), which focused on voter turnout, post-birth effects were the largest for voters aged 18 and pre-birth effects were largest for those at age 50. It is possible that post-birth effects dominate in the 30s and then wane after that. This is something that we believe future researchers should explore in more detail.

Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, we used the SIBS, which focuses on adoptive and biological children and their parents, to examine the impact of parental political engagement on the political engagement of adoptees and nonadopted children. This provided us with a sense of the role of pre-birth factors (e.g., genetics) and post-birth factors (e.g., family socialization) in shaping political engagement. While several previous studies have looked at the influence of pre- and post-birth factors on voter turnout in the Swedish context (where rich registry data are available), we were able to compare our results to these studies using a self-reported measure, which, to our knowledge, has not been done. Additionally, because we had multiple measures of political engagement, we were able to compare the influence of pre- and post-birth factors on different types of engagement. Our results provide suggestive evidence that pre-birth factors are more important to voter turnout than post-birth factors, and we found similar results for two related self-report measures that have not been studied before in the context of an adoption design (sense of civic responsibility and contacting a politician). It is essential to note that because of the small sample size used in this study, our estimates are noisy (it is very difficulty to find a large sample with the necessary properties in the U.S. context). Thus, it is critical that our findings be taken only as suggestive at this point and that our results be replicated in future studies. We would note that even if one prefers to interpret our results as mostly null (since only one coefficient is statistically significant at the p

![]() $ < $

0.05 level), we still see these findings as useful and worth reporting. Our hope is that scholars will eventually be able to conduct a meta-analysis in this area, and it is important that we have results from a wide range of studies (not just those where findings are statistically significant at the conventional level) and contexts.

$ < $

0.05 level), we still see these findings as useful and worth reporting. Our hope is that scholars will eventually be able to conduct a meta-analysis in this area, and it is important that we have results from a wide range of studies (not just those where findings are statistically significant at the conventional level) and contexts.

We believe that our study provides several ideas for future research. First, as noted earlier, replication will be critically important. We encourage scholars to reexamine our findings in the context of larger samples, although we are not aware of other U.S. samples with the necessary properties and relevant measures. Second, it would be valuable to expand the study of pre- and post-birth factors to other acts of political engagement beyond the four examined here. There are many other tools of political engagement available to people, and it will be important to better understand the relative influence of pre- and post-birth factors in shaping each one. Finally, it would be worthwhile to examine not just acts of political engagement but also political attitudes (e.g., political interest or knowledge) in the context of adoption designs. If scholars are interested in ways to get people more interested in politics or increase levels of political knowledge, it would be helpful to better understand the role of pre- and post-birth factors in fostering such attitudes.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/pls.2025.10017.