Introduction

The Fens of eastern England—once the UK’s largest lowland wetland—are characterised by expansive, low topography adjacent to the Wash and the North Sea (Figure 1). Today, the Fens encompass some of the most productive agricultural land in the UK and are among the areas most threatened by present and future environmental change (Water Resources East 2021). Archaeology in the Fens is defined by contradictions, with peats and water-lain sediments both preserving and obscuring the region’s rich archaeoenvironmental record.

Figure 1. The Fens in eastern England, with present-day topography (figure by authors).

The Fens have a long history of landscape-scale investigation, including the 1930s Fenland Research Committee, which sought to explore long-term relationships between culture and environmental change (Smith Reference Smith1997), and the 1980s Fenland Survey where extensive fieldwalking identified more than 2000 sites (Coles & Hall Reference Coles and Hall1994). The past 35 years have been dominated by development-led archaeology, as exemplified by the spectacular later prehistoric sites uncovered at Must Farm (Knight et al. Reference Knight, Ballantyne, Brudenell, Cooper, Gibson and Robinson Zeki2024) and Flag Fen (Pryor Reference Pryor2001). Fenscapes builds uniquely upon this rich body of research, by synthesising the diverse landscape archaeology, palaeoecology and environmental archaeology of the Fens, responding to calls for greater national and regional archaeological data synthesis (Society of Antiquaries of London 2020).

Wetland regions are especially sensitive to change (Matthiesen et al. Reference Matthiesen, Brunning, Carmichael and Hollesen2022), but also pose methodological and interpretive challenges, such as deep burial that limits the visibility of remains. The Fens therefore offer a valuable case study for integrated heritage and environmental management in similarly sensitive lowland wetlands elsewhere. Our aim is to build an archaeological understanding of the Fens that integrates the wealth of previous research, while also critically reviewing biases inherent to that knowledge. Here, we present a case study using three of the diverse datasets newly collated by the Fenscapes project: archaeological events, regional deposit modelling, and plant and animal records.

Archaeological events

Previous archaeological fieldwork ‘events’ in the Fens are archived across the Historic Environment Records (HERs) of Cambridgeshire, Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Suffolk and the City of Peterborough (Figure 2). To quantify these previous investigations, we identified and processed data from excavations and evaluations, which cluster especially around the margins of the Fens where sediment overburden is thinner (Figure 3). The correlation of these data with deposit modelling provides further insight into the nature of this distribution.

Figure 2. HER event data (figure by authors).

Figure 3. Quantified HER event data (figure by authors).

Deposit modelling

The Fens are underlain by a complex of interbedded Holocene strata, locally several metres thick, formed in a variety of diachronous habitats and burying earlier land-surfaces. Sedimentary overburden has an important effect on archaeological visibility, thus making deposit-modelling approaches particularly relevant (Carey et al. Reference Carey, Howard, Knight, Corcoran and Heathcote2018). From a sample of more than 2700 open-source British Geological Survey borehole logs, we generated models of the Early Holocene surface (representing the underlying prehistoric topography that shaped subsequent peat and sediment formation) and the total thickness of Holocene sediments (indicating maximum potential burial depth of archaeological remains) to contextualise other data (Figure 4A & B, respectively).

Figure 4. A) Modelled early Holocene surface; B) modelled total thickness of Holocene sediment and peat; with kernel density estimates of excavations (C) and plant and animal assemblages (D) illustrating the clustered nature of these data (figure by authors).

Spatial cross-comparisons show that excavations have a significant positive correlation with the Early Holocene surface (rs = 0.44) and a negative correlation with the thickness of Holocene sediment (rs = −0.5). These data demonstrate bias in archaeological investigations towards areas that are topographically higher and where Holocene sediment thickness is relatively thin, in turn likely constraining and biasing data from earlier periods. The density of collated plant and animal assemblages (Figure 4D; see below) also strongly correlates with that of excavation events (Figure 4C; rs = 0.73), suggesting the former dataset is broadly representative of the region’s excavation record.

Plants and animals

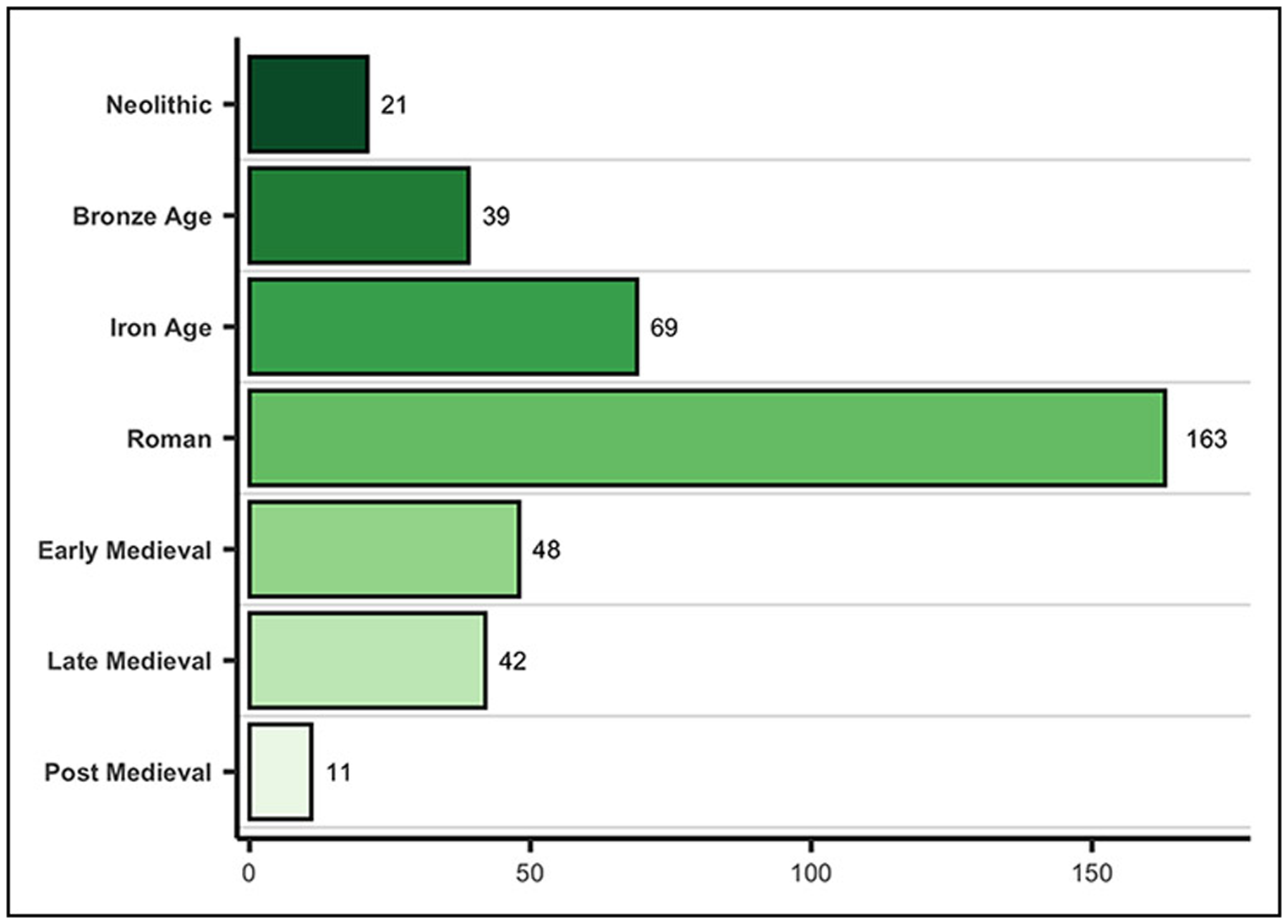

We collated previous syntheses of plant and animal assemblages from the Fens using a systematic inductive approach (Tomlinson & Hall Reference Tomlinson and Hall1996; University of York 2008; Parks Reference Parks2013; Allen et al. Reference Allen2015; Albarella Reference Albarella2019; McKerracher Reference McKerracher2019; Carruthers & Hunter Dowse Reference Carruthers and Hunter Dowse2019; McKerracher et al. Reference McKerracher2023). This produced a consolidated dataset of 393 assemblages, for which the Roman period is by far the best represented (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Number of robust plant and/or animal assemblages by period (figure by authors).

An integrated approach

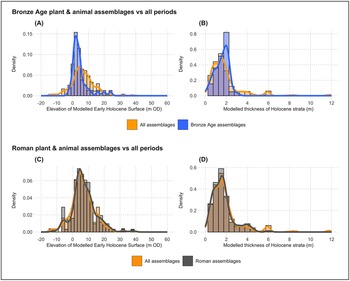

The integrative value of this multiproxy approach is shown by two synthetic examples. Firstly, Bronze Age plant and animal assemblages skew towards lower-lying (Figure 6A) and more deeply buried (Figure 6B) locations typically under-sampled by excavations. These traits cannot guarantee there are undiscovered sites with the richness of Flag Fen and Must Farm, but rather indicate that, despite the fame of the region’s Bronze Age archaeology, its true spatial distribution remains underdetermined. Secondly, and conversely, the relationship between sedimentary overburden and Roman period plant and/or animal assemblages closely resembles that of the full plant and animal dataset (Figure 6C & D), suggesting that the distribution of Roman data may be a truer reflection of activity during this period.

Figure 6. Histograms illustrating the relative density of plant and animal assemblages in relation to the elevation of the early Holocene surface (A & C) and sediment thickness (B & D) (figure by authors).

Towards a new understanding

As awareness grows of the sensitivity and value of wetlands as both cultural and ecological heritage archives (e.g. Hazell et al. Reference Hazell, Last, Campbell, Corcoran and Fluck2023), our preliminary analyses already show the critical importance of underpinning decision-making with multiproxy data synthesis. Biases in the archaeological resource, and their causes, must be fully understood as both human action and climate change drive profound alterations to wetlands. Despite well-known and internationally significant Bronze Age archaeology in the Fens, our results demonstrate that substantial knowledge gaps remain. Notably, the deep sediment overburden common to many wetland regions has a significant, non-random impact on our understanding of the archaeological record.

In lowland wetlands, prioritisation of the most vulnerable and distinctive settings for natural environmental and cultural heritage preservation requires self-critical and synthetic use of existing datasets, which we aim to catalyse through the Fenscapes project.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Cambridgeshire, Lincolnshire, Norfolk and Suffolk County Councils, and Peterborough City Council for providing Historic Environment Record data.

Funding statement

Fenscapes is funded by the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge, as the core research project of the Fenland Futures Archaeological and Heritage Research Initiative (FFAHRI).