I Introduction

In its twenty years of participation in the multilateral trading system, the People’s Republic of China (China) has been using various types of export restrictions. Some of these policies were brought to the attention of the WTO dispute settlement system and provoked heated scholarly debates.

However, recent amendments to Chinese laws and regulations represent a major shift: even a shallow analysis is indicative of a new role that China ascribes to the use of unilateral economic sanctions in general and export restraints in particular. These actions were most likely instigated by the US-China trade war, tightening of US export control regulations, economic sanctions against Chinese technology companies, and a looming US-China “technological de-coupling.”

Given the recency of this policy shift, it has not been a subject of thorough academic scrutiny yet. Notwithstanding this, its potentially significant implications for both China-US bilateral relations and the multilateral trading system make it worthy of a detailed academic inquiry.

The working hypothesis of this paper is that China’s use of export restraints has been traditionally heavily dependent on domestic factors, yet the recent changes signal the shift towards the use of export restrictions as a strategic geopolitical tool, thus reinforcing the role of external factors. To test the accuracy of this assumption, we analyze China’s use of export restrictions in the period from 2001 to 2021. In particular, we suggest that three distinct phases can be discerned along this period: (i) elimination of export restrictions before and after joining the WTO; (ii) selective use of export restrictions mostly for domestic policy reasons till 2016; (iii) shift towards strategic use of export restrictions as an instrument of geopolitical competition since 2017. The latest stage has evolved as a response to the ongoing trade and technological wars waged by the United States against China and economic sanctions against China and its technology companies, as well as a reflection of China’s growing assertiveness in its use of economic coercion.

The paper proceeds in five parts. This introduction sets the stage for a subsequent discussion. The analysis in the following three parts covers the abovementioned three periods of China’s use of export restrictions with the identification of the rationales behind their use. Furthermore, the WTO consistency of these export restraints is briefly examined. The last – the fifth part – presents a forward-looking discussion of the recent changes in China’s laws and regulations, their expected operation and WTO consistency, as well as their potential to disrupt existing global value chains, in particular in the technology sector.

One more clarification is warranted here. In the WTO context, the term export restriction may encompass various types of measures such as export duties (tariffs) and export taxes, export quotas, export licenses, export prohibitions, and minimum export prices (Marceau, Reference Marceau2016). Our analysis in Parts I and II considers diverse types of export restrictions, while our subsequent inquiry in Part IV examines export prohibitions and non-automatic export licenses, that is, instruments that aim at restricting exports as a part of broader economic coercive efforts.

II Elimination of Export Restrictions before and after Acceding to the WTO

China’s economic strategy of gradual opening declared by Deng Xiaoping in 1978 and described as “crossing the river by touching the stones” (Morrison, Reference Morrison2019, p. 5) culminated in China’s accession to the WTO in late 2001 and the subsequent comprehensive liberalization.

Before the economic reforms of the late 1970s, China’s participation in international trade was controlled by a small number of foreign trade corporations, which held monopolies in diverse categories of goods (Ianchovichina & Martin, Reference Ianchovichina and Martin2001). At that time, export volumes were defined by planned levels of imports, that is, imports were financed by export earnings, thus allowing the country to pursue its policy of self-sufficiency (Ianchovichina & Martin, Reference Ianchovichina and Martin2001). A drastic increase in the number of foreign trade corporations from twelve national monopolies to many thousands was among the early reforms put in place by the Chinese government (Harrison, Reference Harrison, Shenggen Fan, Wei and Zhang2014). Li and Jiang (Reference Li, Jiang, Garnaut, Song and Fang2018, p. 576) provide the following numbers: “export trade companies increased from 12 in 1978 to about 1,200 in 1986, reaching a peak of 5,075 in 1988.” This and other economic reforms of 1978–1991 aspired to raise the role of exports in the country’s economic development (Li & Jiang, Reference Li, Jiang, Garnaut, Song and Fang2018).

Later, in the 1990s, as a part of the efforts to liberalize its international trade regime, China significantly reduced categories of products subject to export licensing from 143 categories (48.3% of total exports) in 1992 to 58 categories constituting 9.5% of total exports in 1999 (WTO, 2001b, p. 32). After becoming a WTO Member, China further shortened the list of items subject to export licensing and the WTO Secretariat reported that in 2004 the value of Chinese exports subject to licensing requirement was equal to 4.1% of total exports (WTO, 2006, p. 104).

Thus, in the period leading to the WTO accession, China was pursuing the strategy of export-led growth, and exports were aimed at contributing to the country’s economic development. Despite this, various forms of export restrictions were occasionally employed. The process of China’s WTO accession demonstrated that other WTO Members had serious concerns in this regard. In particular, WTO Members drew attention to the use of non-automatic export licenses, the use of export restrictions on raw materials and intermediate products such as tungsten ore concentrates, rare earths, and other metals, and restrictions on the export of silk (WTO, 2001b). China confirmed its intention to gradually eliminate these restrictions (WTO, 2001b).

Furthermore, in its Accession Protocol, China agreed to eliminate “all taxes and charges applied to exports” with the exception of the fees “specifically provided for in Annex 6 of this Protocol” or “applied in conformity with the provisions of Article VIII of the GATT 1994” (WTO, 2001a). As a matter of law, export duties (tariffs) are permitted under WTO law unless a WTO Member included relevant commitments in its schedule (Marceau, Reference Marceau2016). Since China explicitly included the relevant commitment in its Accession Protocol, it bound itself and agreed to additional WTO obligations not incumbent on other WTO Members, apart from several recently acceded states. In this regard, the panel in China – Raw Materials reiterated that China’s Accession Protocol is an integral part of the WTO Agreement and therefore can be enforced in dispute settlement proceedings.

After its accession to the WTO in 2001, China abolished export quotas and export licences on certain categories of goods (WTO, 2006).

III China’s Use of Export Restrictions for Domestic Policy Reasons in 2001–2016

According to the TPR Report issued in 2006, China had used export taxes, including interim duties that were defined on an annual basis; tax rebates on exports, some of which were paid at a lower rate and thus constituted an export levy; export prohibitions “to avoid shortages in domestic supply, conserve exhaustible natural resources, or in accordance with international obligations” as well as “to meet industry development requirements”; export quotas, which China believed it can justify under Articles XI, XVII, and XX of the GATT 1994 and Annex 2A2 of its Accession Protocol; automatic and non-automatic export licensing (WTO, 2006). Already in this first TPR Report the WTO Secretariat noted that China was purposefully using export restrictions to subsidize downstream industries: “With regard to its trade policy objectives, China is currently aiming to increase its exports of value added products. To this end, China continues to use trade and other measures, to promote local production in certain sectors, either for export, or as inputs for producers in China. The measures include: export taxes, reduced VAT rebate rates, and export licensing to deter exports of some products” (WTO, 2006, p. 44).

The next TPR Report issued in 2008 emphasized China’s increasing use of various types of export restrictions: “the number of tariff lines subject to interim export duties was almost doubled in the last two years, VAT rebate rates on exports of some 2,800 lines (HS 8-digit) were eliminated or lowered in July 2007, and the number of lines subject to export quotas and licensing requirements has increased” (WTO, 2008, p. xi). The subsequent Report of 2010 confirmed that China continued to use various export restrictions (WTO, 2010), while the Report prepared in 2012 documented that export duties were eliminated and interim export duty rates were reduced although the total number of tariff lines subject to export quotas increased, and seasonal special export taxes were adopted (WTO, 2012). The 2014 TPR Report mentioned China’s application of diverse export restrictions and underlined that China’s position of the leading world exporter of certain products, which are subject to its export taxes, may have an impact on the world price of these products (WTO, 2014). The next TPR Report demonstrated that China eliminated or reduced some export restrictions, while tightening others (WTO, 2016).

The World Bank analysts in their 2011 study identified Chinese export restrictions as one of the four issues of significant concern for other WTO Members (Mattoo & Subramanian, Reference Mattoo and Subramanian2011). It comes as no surprise since the economic repercussions of those export restrictions were felt acutely: according to some estimates, a reduction in Chinese export quotas in rare earth resulted in more than a seven-fold increase in world prices (Bond & Trachtman, Reference Bond and Trachtman2016).

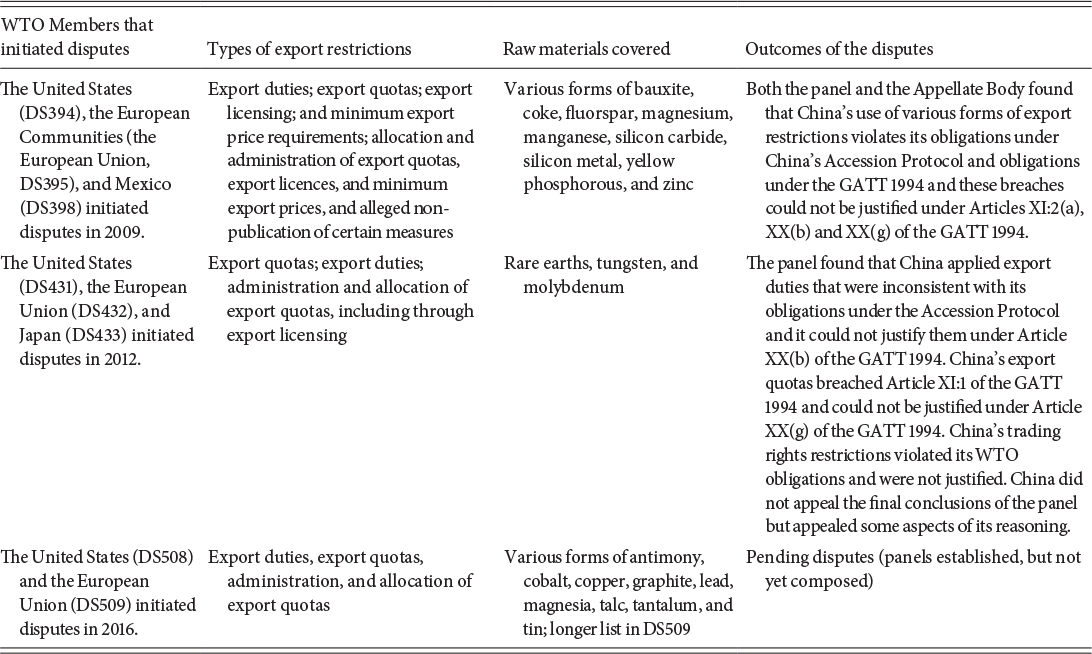

Several WTO Members questioned the compatibility of Chinese export restrictions with its WTO commitments. Table 7.1 presents a short summary of these disputes.

Table 7.1 WTO disputes, wherein the WTO compatibility of Chinese export restrictions was questioned

| WTO Members that initiated disputes | Types of export restrictions | Raw materials covered | Outcomes of the disputes |

|---|---|---|---|

| The United States (DS394), the European Communities (the European Union, DS395), and Mexico (DS398) initiated disputes in 2009. | Export duties; export quotas; export licensing; and minimum export price requirements; allocation and administration of export quotas, export licences, and minimum export prices, and alleged non-publication of certain measures | Various forms of bauxite, coke, fluorspar, magnesium, manganese, silicon carbide, silicon metal, yellow phosphorous, and zinc | Both the panel and the Appellate Body found that China’s use of various forms of export restrictions violates its obligations under China’s Accession Protocol and obligations under the GATT 1994 and these breaches could not be justified under Articles XI:2(a), XX(b) and XX(g) of the GATT 1994. |

| The United States (DS431), the European Union (DS432), and Japan (DS433) initiated disputes in 2012. | Export quotas; export duties; administration and allocation of export quotas, including through export licensing | Rare earths, tungsten, and molybdenum | The panel found that China applied export duties that were inconsistent with its obligations under the Accession Protocol and it could not justify them under Article XX(b) of the GATT 1994. China’s export quotas breached Article XI:1 of the GATT 1994 and could not be justified under Article XX(g) of the GATT 1994. China’s trading rights restrictions violated its WTO obligations and were not justified. China did not appeal the final conclusions of the panel but appealed some aspects of its reasoning. |

| The United States (DS508) and the European Union (DS509) initiated disputes in 2016. | Export duties, export quotas, administration, and allocation of export quotas | Various forms of antimony, cobalt, copper, graphite, lead, magnesia, talc, tantalum, and tin; longer list in DS509 | Pending disputes (panels established, but not yet composed) |

The legal discussions in these disputes revolved around two core issues: first, the application of general exceptions prescribed by Article XX of the GATT 1994 to China’s commitment to eliminate export duties enshrined in its Protocol of Accession; and second, the possibility to justify export restrictions inconsistent with Article XI:1 of the GATT 1994 under Articles XI:2(a), XX(b) and XX(g) of the GATT 1994. To be more specific, China claimed that its diverse export restrictions were aimed at the conservation of exhaustible natural resources as well as the prevention of environmental pollution and thus, protection of human life and health,Footnote 1 while the WTO Members that initiated these disputes contended that the subsidization of downstream industriesFootnote 2 and the relocation of foreign firms to ChinaFootnote 3 were the main objectives. China, in an attempt to justify its export restrictions as “related to” the conservation of exhaustible natural resources, emphasized their “signalling” function,Footnote 4 a point to which we will return in the next section.

Discussing the veracity of China’s assertion that export restrictions, in particular export quotas, were implemented to conserve natural resources, commentators point out that the efficiency of export restraints in contributing to the declared goal of conserving exhaustible natural resources and reducing pollution could be undermined by the growing domestic consumption (Pothen & Fink, Reference Pothen and Fink2015; Bond & Trachtman, Reference Bond and Trachtman2016).

The WTO rulings in these disputes were vehemently criticized. For example, Qin (Reference Qin2012) contends that the AB in China – Raw Materials dispute misinterpreted China’s commitments under its Accession Protocol. In particular, she concludes that the correct application of the rules of treaty interpretation enshrined in the VCLT would allow exceptions under Article XX of the GATT 1994 to serve as exceptions to China’s additional commitments to eliminate export tariffs (Qin, Reference Qin2012). Gao (Reference Gao, Gao, Raess and Zeng2023) argues in this volume that the flawed legal reasoning followed by the WTO adjudicators not only downgraded China to a “second-class citizen” but also led to China’s growing disillusionment with the multilateral trading system. This disillusionment has been strongly reinforced by the recent unilateral, plurilateral, and multilateral attacks carried out by the United States and its allies against China and resulting in what Gao (Reference Gao, Gao, Raess and Zeng2023) calls China’s “alienation” from the WTO and its core principles. Echoing our assertion that since recently China is more willing to use trade policy as a weapon, Gao (Reference Gao, Gao, Raess and Zeng2023) observes that “the US has effectively taught China that WTO rules could be just ignored, especially as it gets in the way.”

Economic studies reveal that Chinese export restrictions pursued diverse policy goals. The empirical study by Gourdon, Monjon, and Poncet (Reference Gourdon, Monjon and Poncet2016) analyzed the rationales behind the Chinese fiscal policies aimed at curtailing exports (export taxes and VAT rebates) in the period of 2004–2012. They conclude that these fiscal tools were employed for a number of reasons: to support sophisticated high-technology products, to curb exports of water polluting sectors and air polluting products, to benefit upstream industries and to limit the cost of the application of antidumping measures by trade partners (Gourdon et al., Reference Gourdon, Monjon and Poncet2016). Another study by Pothen and Fink (Reference Pothen and Fink2015) conclude that China’s export restrictions on rare earth pursued three main objectives: to create incentives for foreign industries to relocate to China, to conserve exhaustible natural resources and to reduce pollution. Chad Bown (Reference Bown2020) draws a similar conclusion that China’s export restrictions provided unfair advantages to Chinese manufacturers and enabled them to use cheap local inputs. In view of this, it is reasonable to assume that Chinese export restrictions, among other things, pursued environmental objectives as well.

Legal scholars echo some of the abovementioned views. For example, Wu (Reference Wu2017) asserted that Chinese policies of curtailing exports of critical minerals pursued multiple economic goals: (i) to entice foreign producers to relocate to China; (ii) to instigate the transfer of foreign technologies that would occur as a result of the relocation of foreign producers combined with investment restrictions, thus requiring foreign producers to partner with Chinese firms; and (iii) to promote a “cluster effect” enabling China to dominate in manufacturing in new industries. Writing in 2017, Mark Wu argued that the Chinese practice of using export restrictions still persists. In his view, China takes advantage of a “free pass” – the lack of retrospective remedies in the WTO dispute settlement system – to bolster its industrial policy through export restrictions (Wu, Reference Wu2017). In this regard, it should be noted that not only China takes advantage of systemic loopholes in the WTO dispute settlement system but, as Zhou (Reference Zhou, Gao, Raess and Zeng2023) accurately observes in this volume, other WTO Members also use these systemic constraints and loopholes and do it even more frequently.

In this period, China at least once employed export restrictions as an instrument of economic coercion, when it targeted Japan in 2010 after the accident in the disputed waters near the Senkaku (Diaoyu) islands in the East China Sea (Bradsher, Reference Bradsher2010; Tabuchi, Reference Tabuchi2010; Poh, Reference Poh2021).

IV Strategic Use of Export Restrictions as an Instrument of Geopolitical Competition

In this section, we analyze China’s shift towards the explicit use of export restrictions as a tool of unilateral economic coercion, which contradicts its prior long-standing practice.

(i) China’s Attitude towards Unilateral Economic Sanctions (Non-UN Sanctions) and Its Practice

China has traditionally generated strong headwinds against economic coercion in the form of unilateral economic sanctions (non-UN sanctions).Footnote 5 In particular, it opposes the recognition of unilateral economic sanctions’ legality in international law (Hofer, Reference Hofer2017; Poh, Reference Poh2021). Although this position may rest on shaky legal ground – international law scholars refuse to acknowledge the existence of the right to be free from economic coercion (Tzanakopoulos, Reference Tzanakopoulos2015), China’s vehement opposition to unilateral sanctions is reflected in its persistent anti-sanctions rhetoric, which depicts Western sanctions as imperialist and interventionist (Poh, Reference Poh2021). According to some commentators, this rhetoric has a constraining effect on China’s use of unilateral economic coercion (Poh, Reference Poh2021).

Until recently China’s use of unilateral economic coercion was of a limited nature and was confined to consumer boycotts silently supported by the government (Kashin et al., Reference Kashin, Piatachkova and Krasheninnikova2020). Yet a decade ago, the tide has slowly begun to shift: commentators took note of an increasing Chinese “assertiveness” in deploying not only economic inducements but also unilateral economic sanctions for geopolitical objectives (Glaser, Reference Glaser2012; Reilly, Reference Reilly2013).

Distinctive features that characterize Chinese unilateral sanctions are their unofficial and undocumented application as well as their narrow scope that is, only specific sectors were targeted, while the existing trade and investment patterns were preserved (Poh, Reference Poh2021). Scholars also point out China’s ability to deftly combine instruments of economic coercion with economic inducements and diplomatic negotiations (Harrell et al., Reference Harrell, Rosenberg and Saravalle2018).

The literature on China’s use of unilateral economic sanctions highlights their signaling function (Poh, Reference Poh2021). This signaling function is of a dualistic nature: it sends a signal to sanctioned states and other states (Blackwill & Harris, Reference Blackwill and Harris2016; Poh, Reference Poh2021), as well as to domestic audiences, thus serving domestic political purposes (Harrell et al., Reference Harrell, Rosenberg and Saravalle2018). Concerning the former aspect, Robert Blackwill and Jennifer Harris (Reference Blackwill and Harris2016, p. 120) observe: “[…] China has merely signaled to its neighbors the costs of risking geopolitical daylight between it and them, making those governments less inclined to act in ways that would run counter to China’s strategic objectives.”

China’s growing assertiveness, which has been observed in the past decade, encompasses the use of various forms of restrictions, yet export restrictions have been the least employed ones (Harrell et al., Reference Harrell, Rosenberg and Saravalle2018). This hesitation could be explained by the following factors: (i) China’s reliance on its exports and its desire to maintain its status as a reliable supplier, hence securing its place in the existing supply chains; (ii) the previous rulings of the WTO adjudicators, wherein Chinese export restrictions were recognized as inconsistent with its obligations under WTO law (Harrell et al., Reference Harrell, Rosenberg and Saravalle2018). Notwithstanding this, the recent shift towards a new geo-economic global order characterized by “securitisation of economic policy and economisation of strategic policy” (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Moraes and Ferguson2019) and the “weaponization” of export restrictions by the United States (Fuller, Reference Fuller2021) paved the way for new Chinese laws that establish a framework for using unilateral economic sanctions, including targeted export restrictions. Talking about “weaponization” of export restrictions by the United States, the US export regulations were vastly expanded to prohibit exports of inputs crucial for the integrated circuit industry, in particular design and fabrication of chips, to Huawei and its subsidiaries and thus, undermining company’s growth and its capacity to provide competitive 5G equipment (Fuller, Reference Fuller2021). Those US unilateral sanctions crippling Huawei’s potential to compete globally reinvigorated the ambitious technonationalist agenda in China – China’s attempts to promote self-sufficiency in strategic technologies, which are deeply rooted in the Chinese national development strategy (Feigenbaum, Reference Feigenbaum2017), as well as spurred retaliatory moves (Fuller, Reference Fuller2021).

(ii) Recent Changes in China’s Laws and Regulations

Even before the WTO accession, Article 7 of China’s Foreign Trade Law allowed retaliation in the form of economic sanctions against any other country if it takes “discriminatory, prohibitive, or restrictive trade measures.” The law does not define what measures constitute “discriminatory, prohibitive, or restrictive trade measures”; thus, enabling its ambiguous application. It is noteworthy that similar provisions in the US legislation – Sections 301–310 of the Trade Act of 1974 – were ruled to be inconsistent with WTO obligations (Panel Report, US – Section 301 Trade Act).

Trade and tech wars between the United States and China instigated major revisions to China’s laws and regulations. To be more specific, China started to pursue more advanced economic statecraft, emulating Western tools used for this purpose. In May 2019, China announced the creation of the Unreliable Entities List (UEL) and the later adopted regulation defines “unreliable entity” as a foreign legal entity, organization, or an individual that boycotts or cuts off supplies to Chinese entities for non-commercial reasons, takes discriminatory measures against Chinese companies, and, as a result, causes material damage to Chinese companies or related industries and threatens or potentially threatens China’s national security (MOFCOM, 2020). According to Article 10 of the relevant regulation, blacklisted entities are subject to import and export restrictions (MOFCOM, 2020). The US commentators have compared this new Chinese regulation with similar US procedures and concluded as follows: “While the list triggers export control action similar to the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Entity List, China’s justifications for including an entity on the list appear to be much broader” (Sutter, Reference Sutter2020, pp. 2–3).

Attempts to unify previously fragmented export control regimes into a single and comprehensive framework culminated in the enactment of the Export Control Law (ECL) in 2020. This law aims to protect China’s national security and to provide a basis for export restrictions that exceed the typical remit of security and defense measures, that is, it gives the Chinese government a toehold to enact retaliatory measures against other states and their entities (PRC Export Control Law, 2020). The ECL (2020) regulates exports of dual-use, military and nuclear items, as well as other goods, technologies, and services related to national security and national interests. The law uses ambiguous language that leaves ample room for further interpretations (Zhu, Reference Zhu2020). Article 48 of the ECL is of importance for our analysis: it stipulates specific rules authorizing reciprocal measures to be taken in response to export controls implemented by other states.

This new statutory power comes at a time when the US Export Controls Act of 2018 introduced major changes to US export control regulations by expanding the scope of technologies subject to export controls to include a new category called “emerging and foundational technologies” (John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act, Reference John2018). This development has been described by Whang (Reference Whang2019, p. 598) as: “Export control regimes have now been incorporated to also reflect a country’s economic policies.” In other words, the United States can use export control regulations to implement additional restrictions against China by making exports of “emerging and foundational technologies” subject to such regulations.

Furthermore, in 2019, the US Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) included Huawei and its non-US subsidiaries in the so-called Entity List, making all exports, re-exports, and in-country transfers subject to a license requirement issued under the presumption of denial (US Department of Commerce, 2019a, 2019b). Later, the BIS further tightened these export restrictions to practically deprive Huawei and any of its affiliated entities from accessing integrated circuits (chips) either produced in the United States or produced with the use of US technologies or equipment (US Department of Commerce, 2020). In view of this, the powers granted under Article 48 of the ECL seem to carry not only political overtones but also to enable Chinese retaliatory actions.

Commentators have already noted this shift in Chinese policy: “This law [ECL] helps China to align its export control practices with those of the United States, giving it legal grounds to apply similar tactics in their growing technology war” (Zhu, Reference Zhu2020). The US analysts have observed that: “The final language [of the ECL] includes several new provisions that appear aimed at creating a Chinese policy counterweight to the U.S. government’s use of export control authorities to restrict the transfer of U.S. dual-use technology to China, including provisions for retaliatory action and extraterritorial jurisdiction” (Sutter, Reference Sutter2020, p. 1).

China issued its first control list under the ECL, which includes encryption technology and data security chips as the first subjects of its new export control regime (Kawate, Reference Kawate2020). According to Article 12 of the ECL, Chinese companies seeking to export products on the control list must obtain prior approval from the export control administrations.

Apart from enacting the ECL, China engaged in international efforts to build a coalition of like-minded states in order to counterweight the US policy of adding “emerging and foundational technologies” to the list of items subject to export control regulations. In particular, China sponsored the UN General Assembly resolution “Promoting International Cooperation on Peaceful Uses in the Context of International Security” that was adopted in December 2021. This resolution not only emphasizes the significance of international cooperation on materials, equipment, and technology for peaceful purposes but also urges all UN Members to lift undue restrictions on the exports of technology to developing countries if it is used for peaceful purposes (UN General Assembly, 2021). Furthermore, in late December 2021, the State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China issued a white paper on China’s export controls, which criticizes abuse of export control regulations by saying: “No country or region should abuse export control measures, gratuitously impose discriminatory restrictions, apply double standards to matters related to non-proliferation, or abuse multilateral mechanisms related to export controls for the purposes of discrimination and exclusion.”

This move – China’s active engagement in setting new global rules – is not a new development. In this regard, Gao (Reference Gao and Deere-Birkbeck2011) has already contended that China has emerged as an international rule-maker contrary to its earlier role as a rule-taker.

In April 2021, China’s Ministry of Commerce released an updated version of the Guiding Opinion of the Ministry of Commerce on the Establishment of Internal Compliance Mechanism for Export Controls on Exporters of Dual-Use Items (Guidelines). The Guidelines are the latest substantive effort to expand export controls since the ECL was adopted. As an implementing regulation of the ECL, the Guidelines aim to provide companies with the guidance on establishment and enhancement of internal export compliance programs and in such a way promote compliance with the new export control regime (Crowell & Moring, 2021). To this end, companies are encouraged to set up an export control compliance committee and an export control compliance department (Crowell & Moring, 2021).

Another pertinent development in this regard is the second update of the Catalogue of Technologies Prohibited or Restricted from Export (Catalogue) published in August 2020, which resulted in an addition of 23 new items to the export-restricted technologies. The newly added technologies are those related to encryption, cyber defense, metal 3D printing, aero remote sensors, and unmanned aerial vehicles (Catalogue, 2020). These technologies are subject to a license requirement, and they cannot be exported without approval from the Chinese commerce authorities (Yunfeng, Reference Yunfeng2020). In September 2020, Beijing Commerce Bureau made a public announcement that it would strictly enforce the Catalogue, and if technology falls into the restricted category, it would demand that business operators file an application for approval before they enter into any negotiations for the export of such technology (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Zhang, Zhang and Li2020).

These recent developments attest to the accuracy of our assertion that China modifies its policy and is willing to use its export restrictions as a geopolitical tool.

Two other laws deserve our attention as well. These laws are the Data Security Law and the Anti-foreign Sanctions Law. In June 2021, China adopted its Data Security Law, which enhances the state’s authority over the collection, use, and protection of data. Article 26 of the law allows for “equal countermeasures” to be taken if another state enacts any “discriminatory” or “restrictive” investment or trade measure related to data or technology for data development and utilization (Data Security Law, 2021). By enacting this law, Beijing establishes statutory power to retaliate against foreign restrictions on Chinese technology firms.

Furthermore, in June 2021, China passed Anti-foreign Sanctions Law (AFSL). This law empowers competent Chinese authorities to sanction persons and organizations that are directly or indirectly involved in the formulation, decision-making, or implementation of discriminatory restrictive measures directed against China (Anti-foreign Sanctions Law, 2021). According to Articles 4 and 5 of the law, these sanctions may also be extended to spouses and immediate family members of the sanctioned persons and to the managers of the listed organizations (Anti-foreign Sanctions Law, 2021). Article 6 of this law specifies restrictive measures that could be used against sanctioned individuals and organizations, and they include denial of visa issuance, denial of entry, deportation, prohibition or restriction to conduct transactions, to cooperate or engage in other activities with Chinese individuals or organizations, and other necessary measures (Anti-foreign Sanctions Law, 2021). Pursuant to Article 6(3) of the AFSL sanctioned individuals and organizations are prohibited from having any transaction with organizations and individuals on the territory of China, and consequently, Chinese entities and individuals are prevented from engaging in exporting to sanctioned persons and entities (Anti-foreign Sanctions Law, 2021). The AFSL laid the groundwork for China’s efforts to expand its retaliatory toolkit, to establish the application of its laws extraterritorially,Footnote 6 and to police behavior beyond the Chinese border (Drinhausen & Legarda, Reference Drinhausen and Legarda2021).

(iii) Are We Heading towards “Weaponization” of Exports by China?

While in the past Chinese economic sanctions played second fiddle to economic inducements, the recent changes in China’s regulatory framework are reflective of its willingness to be more assertive in employing economic coercion. In this regard, Mingjiang Li (Reference Li2017, p. xxv) observes that “China is gradually becoming more prepared to use its economic power for coercive purposes.”

This growing assertiveness is further fuelled by several contributory factors. First, the abovementioned Chinese laws have been introduced against the background of the US-China trade and tech wars and the US efforts to tighten its export controls by empowering the Bureau of Industry and Security to update export control regulations to include “emerging and foundational technologies” that are “essential to the national security” (Bown, Reference Bown2020). Second, China’s ambition to become a global leader in innovative technologies is grounded not only in its desire to become technologically self-sufficient but also in its intention to use this leverage against its adversaries. Commentators posit that “China’s efforts to move up in the value chain and to master the transformative technologies of the future – from robotics to electric vehicles – may not only protect Beijing from foreign attempts to coerce it but may also give it new export restriction levers to pull to coerce adversaries” (Harrell et al., Reference Harrell, Rosenberg and Saravalle2018, p. 17).

This shift contrasts with the previous instances of Chinese economic coercion in one essential element – more open and transparent use of economic coercion – that is achieved through the revision of the existing laws and regulations as well as through the enactment of the new ones. Put it differently, the process of economic sanctions formalization, which has been achieved through the establishment of a formal legal regulatory framework, is a core element in a new China sanctions policy.

V What Are the Broader Implications of China’s Shift in Use of Export Restrictions?

These new laws and regulations herald a departure from China’s traditional policy of avoiding unilateral economic sanctions. What would these new legislations portend for multinational corporations and existing supply chains? The implications of the new Chinese assertiveness in using economic coercion may be felt acutely by multinational businesses. Lovely and Schott (Reference Lovely and Schott2021) predict that these new rules would force companies to choose between access to the Chinese market and access to the US market, and this choice may also entail penalties that might be imposed by both sides. Discussing China’s new policy Greg Gilligan, chairman of the American Chamber of Commerce in China, has already warned that the recent developments may present “potentially irreconcilable compliance problems” (Bloomberg News, 2021).

Even if China never invokes its new regulations, their existence creates new risks for multinational corporations doing business either in China or with their Chinese counterparts. Furthermore, these new regulations add pressure to the growing US-China trade frictions and may, in the long run, result in the restructuring of the global supply chains. Concerns have been already expressed that the US sanctions against Chinese tech companies would create a risk of a “divided tech world,” in particular by undermining trust in the existing global supply chains (Knight, Reference Knight2019).

If China begins to erect technology transfer controls as a part of its economic coercive strategy, such export restrictions may play a growing role as implements of the tech war between the United States and China. Discussing this possibility, one more peculiarity of Chinese unilateral sanctions should be noted. As a rule, China targets politically and economically sensitive foreign constituencies irrespective of their connection to the sanctionable conduct (Harrell et al., Reference Harrell, Rosenberg and Saravalle2018). Thus, from a global perspective, these actions may further bifurcate the global economy and lead to a full-scale “technological de-coupling” (Webster et al., Reference Webster, Luo, Sacks, Wilson and Coplin2020).

The new Chinese laws prescribe the use of the two types of export restrictions as potential sanctions: either a complete prohibition of exports or an export license requirement as a precondition for exports. It is worth observing that export prohibitions (bans) as well as non-automatic export licensing schemes, especially if they are administered in a non-transparent and discriminatory way, run afoul of the WTO commitments (Bogdanova, Reference Bogdanova2021). To be more specific, export bans on goods are inconsistent with the prohibition of quantitative restrictions enshrined in Article XI:1 of the GATT 1994, which has been interpreted broadly: “[T]he text of Article XI:1 is very broad in scope, providing for a general ban on import or export restrictions or prohibitions ‘other than duties, taxes or other charges’” (Panel Report, India – Quantitative Restrictions). Restrictions on the exportation of services may be GATS-incompatible only if a WTO Member has undertaken market access commitments in a specific services sector and under mode 3, which also covers the right to export services to recipients abroad (Bogdanova, Reference Bogdanova2021). Regarding export license schemes, the panel in China – Raw Materials concluded that: “a licence requirement that results in a restriction […] would be inconsistent with GATT Article XI:1. Such restriction may arise in cases where licensing agencies have unfettered or undefined discretion to reject a licence application.” Thus, depending on the administration of export license schemes, such measures might breach an obligation to eliminate quantitative restrictions of Article XI:1 of the GATT 1994.

Wu (Reference Wu2017) has already pointed out that the lack of retrospective remedies in the WTO dispute settlement system ought to be blamed for China’s willingness to temporary free-ride and enact export restrictions to the benefit of its domestic downstream industries. The same logic may be used for its strategic export restrictions. Foreign producers, faced with the need to respond to such Chinese policies, could not hold back and thus risk jeopardizing their supply chain and damaging their economic interests. In such circumstances, some companies may decide to relocate to China,Footnote 7 while others might restructure their supply chains. This development may further erode the multilateral trading system as well as undermine its credibility for WTO Members and for private businesses.

VI Concluding Remarks

This chapter argues that China is more willing than before to use instruments of economic coercion such as unilateral economic sanctions for its political goals. Several implications flow from this new development. First, it may have a bearing on the existing global supply chains. In particular, the use of various export restrictions, especially those related to novel and emerging technologies, by the two leading tech powerhouses – the United States and China – may result in a de-globalization of the technology supply chains. Second, China’s strategic use of export restrictions, especially in the tech industry, may bifurcate the global economy resulting in what has been dubbed a “technological de-coupling” and sapping the potential growth performance of the global economy. This possibility looms large on the horizon. Third, export bans and ambiguous and non-transparent export licensing requirements are incompatible with WTO obligations. However, the duration of the WTO dispute settlement procedures and the lack of retrospective remedies significantly undermine the ability to provide an effective remedy for multinational businesses that operate in a globally interdependent environment, thus further contributing to the erosion of the multilateral trading system and the WTO as an institution.