In response to Bailey (Reference Bailey2025), we revisited the subgroup classification of the treatment specificity variable, that is, whether a treatment was considered specialized for repetitive negative thinking (RNT) or general. We considered the critique of a potential misclassification of treatments and repeated our classification procedure arriving at a plausibly more consistent solution. Specifically, we reassigned meta-cognitive therapy treatments, Applied Relaxation treatments, and one Emotion Regulation Therapy treatment to the specialized (RNT-specific) group. For a more detailed discussion, please refer to our response letter (Stenzel et al., Reference Stenzel, Keller, Kirchner, Rief and Berg2026) to the letter by Bailey (Reference Bailey2025). Most importantly, no conclusions were affected by this. However, after reclassifying the treatments and the reanalysis, the following statistical values (in bold) have changed and should be substituted. Also, the Table 1 and the Figure 2 have changed and should be updated.

p. 1: Abstract

RNT-specific interventions ( g = −0.87) were significantly more efficacious in reducing RNT than less specific approaches ( g = −0.48).

p. 6: Meta-regressions and subgroup analyses

Subgroup analysis suggested a significant differential effect of treatment specificity Q(1) = 8.05, p = 0.005, such that general approaches yield smaller effect sizes ( g = −0.48) than RNT-specific interventions ( g = −0.87).

p. 9: Efficacy of RNT-specific interventions

RNT-specific interventions seemed to outperform general approaches significantly ( Δg = 0.39).

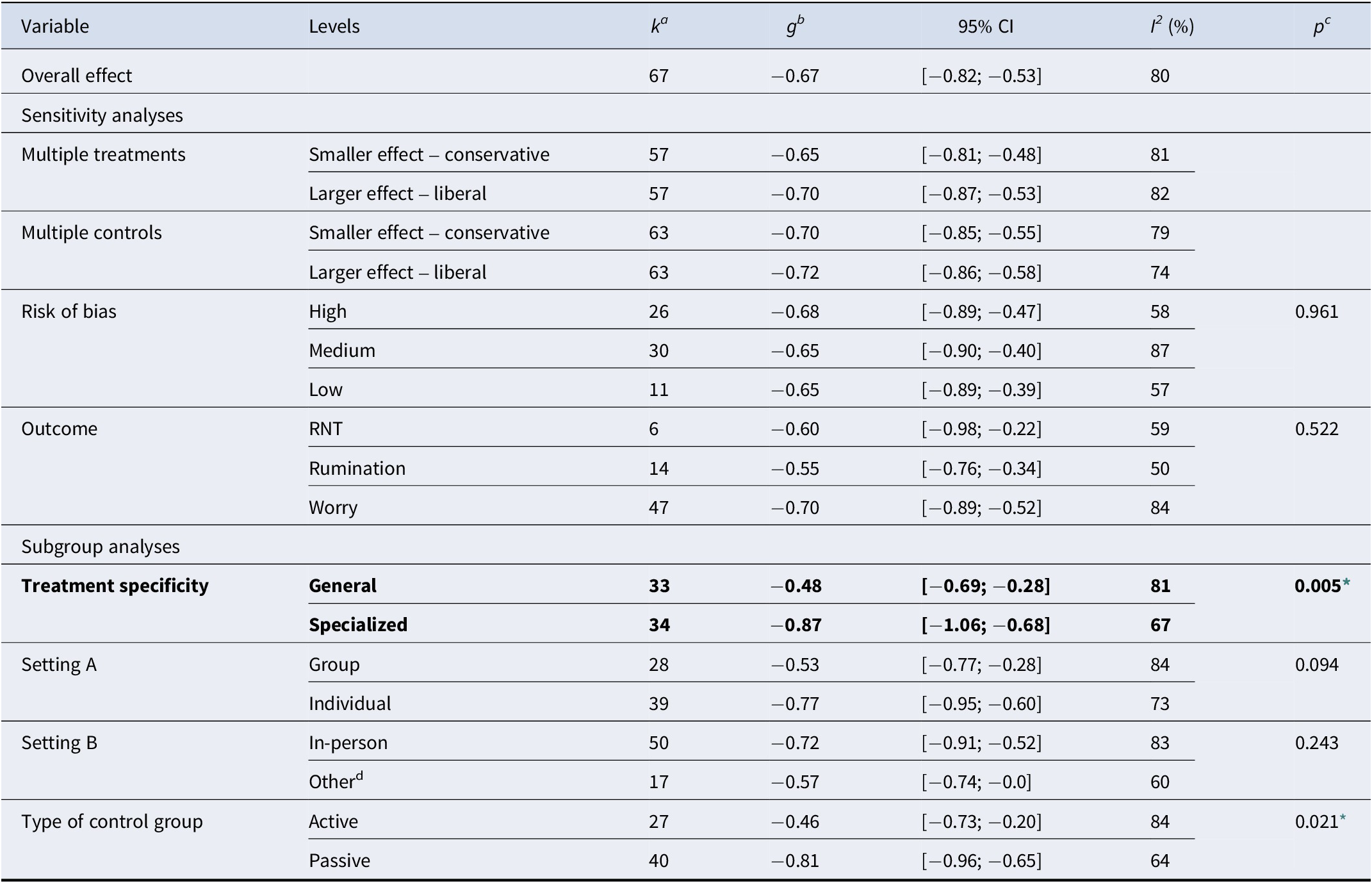

p. 4:

Table 1. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on repetitive negative thinking compared with control groups at post-treatment

Note: ak indicates the number of comparisons for each level. bg indicates Hedge’s g. cp indicates whether the effect sizes of subgroups differed significantly from each other based on a Q-test. dOther indicates internet-based therapy with or without in-person support, phone call, video call, or mixed therapy (in-person and phone call).

* p < 0.05.

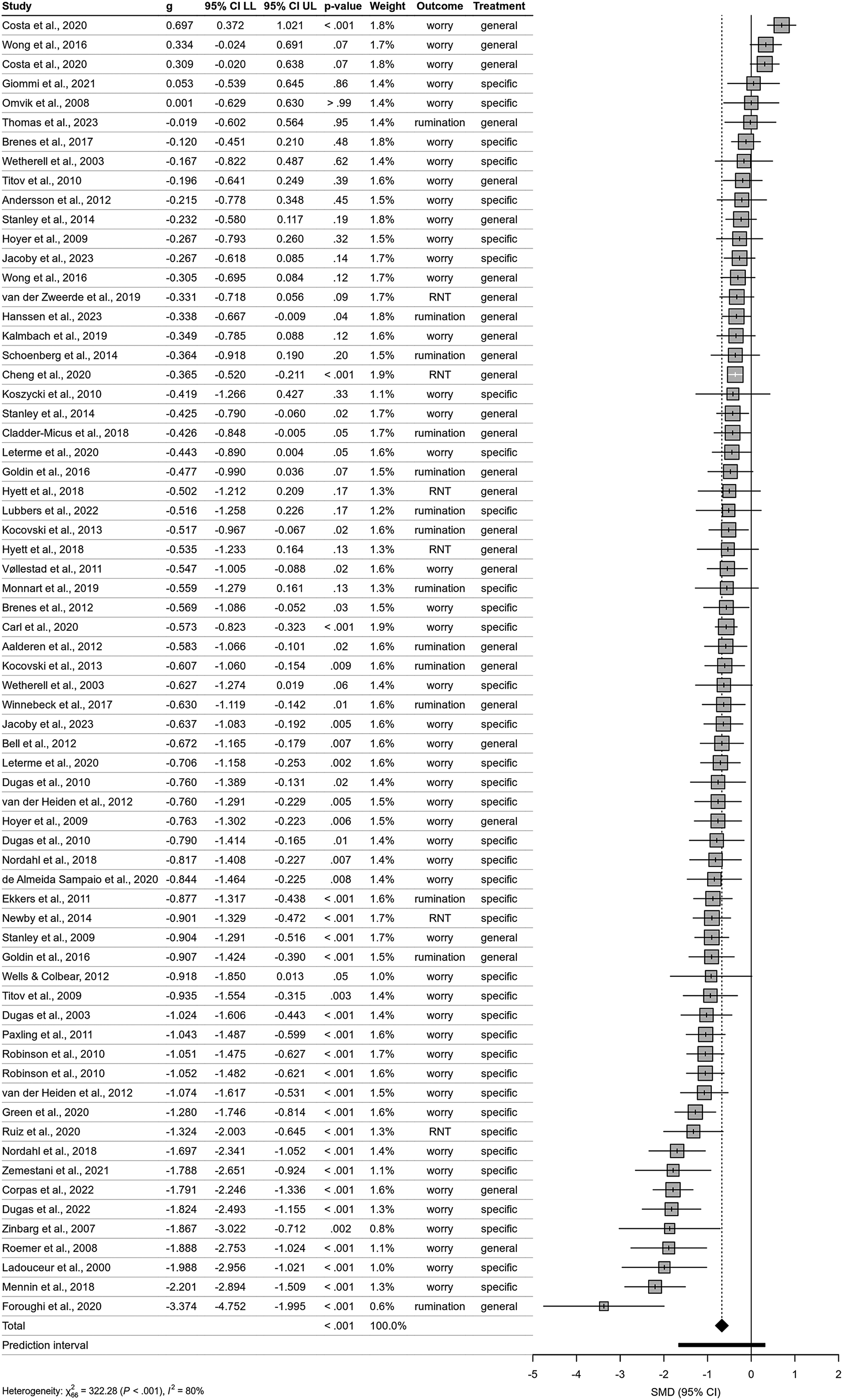

p. 7:

Figure 2. Forest plot of included studies examining the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy compared with control group on repetitive negative thinking (RNT) at post-treatment. Note: Negative values indicate improvement in RNT. The position of the diamond shape indicates the average effect and its width indicates the confidence interval of the pooled result. The horizontal bar indicates the prediction interval – a range into which the effects of future studies may fall based on present evidence. g, Hedge’s g; CI, confidence interval; LL, lower level; UL, upper level; Treatment, treatment specificity with regard to RNT; X2, chi-square test of heterogeneity – higher values indicate that observed differences can less likely be explained by chance alone; I 2, measure of between-study heterogeneity; SMD, Standardized Mean Difference.

Competing interests

W.R. declares to have received honoraria for scientific talks from Boehringer Ingelheim and to receive royalties for book publications. K.L.S., J.K., L.K., and M.B. declare no competing interests, neither financial nor otherwise.