When I’m through, about everybody will have one.

In wealth, we have come far, when few have too much and few too little.

This chapter offers key historical glimpses into the parallel development of American and Nordic capitalisms, illuminating how their distinct historical paths shaped their modern forms. For comprehensive historical analyses, readers are encouraged to consult Ages of American Capitalism, Creating Nordic Capitalism, Nordic Capitalisms and Globalization, and Politics against Markets.Footnote 1

This chapter examines two transformative figures who embodied and shaped their respective capitalist systems: Henry T. Ford, whose efficiency-driven approach epitomized American capitalism, and N. F. S. Grundtvig, whose democratic vision helped forge Nordic capitalism.

Ford’s innovations in production efficiency revolutionized the automobile industry, making cars accessible to a broader population and fueling mass consumerism. The profits generated by Ford Motor Company created immense personal wealth for Ford, which he used to establish the Ford Foundation, illustrating a key feature of American capitalism where a portion of private wealth is directed toward public needs through philanthropy. In contrast, Grundtvig’s contributions to Nordic capitalism emphasize democratic values and more equitable wealth distribution, balancing private sector profit-making with broader stakeholder interests. Grundtvig’s influence helped lay the groundwork for a democratically accountable state that guarantees universal access to essential services like education and healthcare, funded by taxes. These contrasting approaches provide valuable insights into the fundamental differences between American and Nordic varieties of capitalism.

American Capitalism: History Glimpses

Carl Degler aptly remarked, “Capitalism arrived in the first ships,” capturing capitalism’s intrinsic role in shaping the US.Footnote 2 A key feature of capitalism is private ownership of capital. American capitalism adopted European property rights concepts, significantly influenced by Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke.

Degler’s metaphor of the arriving ships alludes, in part, to the slave ships that underscored the darkest aspect of early American capitalism – where property rights extended to the ownership of human beings. American capitalism is rooted in a proprietarian ideology, as described by Thomas Piketty, wherein political power and liberties are disproportionately granted to property owners. American capitalism in all its eras could be rightfully described as tethered to a proprietarian ideology.Footnote 3

American Property Rights and John Locke

John Locke profoundly shaped American property rights through his emphasis on individual ownership, views reflected in the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. His Two Treatises of Government (1689) argued that Native Americans lacked legal claims to land ownership due to the absence of European-style boundaries – a mistaken view that nonetheless became foundational to US law.Footnote 4

According to Locke, the fundamental natural rights consist of “life, liberty, and property.” Thomas Jefferson echoed Locke in drafting the second paragraph of the US Declaration of Independence, with a crucial substitution: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Here, Jefferson deliberately replaced “property” with “the pursuit of happiness.”Footnote 5

American Property Rights … for Whom?

French observer Alexis de Tocqueville, during the early 1800s, was astounded by the American ethos of granting individuals more freedom and opportunities than Europe’s aristocracies. In his seminal work, Democracy in America, he noted the incredible opportunity for European immigrants to enjoy greater freedom and obtain property in the US. Long before the phrase “‘American Dream’” was coined, the US embodied its core principles of freedom and opportunity for many.Footnote 6

In the early stages of American capitalism, property ownership was restricted mainly to white adult males, excluding other groups from the benefits of economic opportunity.Footnote 7 Using my family history as an example, my great-great-grandfather, Knut Strand, migrated from Norway and arrived in the US in 1861. Shortly after that, he was given a large plot of land in Wisconsin following the passing of the Homestead Act of 1862, which the Strand family would farm for generations. Knut was a peasant in Norway with no prospects of acquiring land, but in the US, he received land based on his status as a white adult male. James Baldwin observed that immigrants like my great-great-grandfather “became white upon their arrival to America,” and white was power.Footnote 8

Historian Moses Finley characterized the US South as a “genuine slave society,” meaning the institution of slavery profoundly impacted virtually all aspects of society. But what set the young US apart from previous slave societies, like ancient Greece and ancient Rome, was the newfound marriage between the process of racialization and the institution of slavery. The racialization of who was classified as white or black took shape during the era of the transatlantic slave trade. European colonizers developed racial categories to legitimize and perpetuate the enslavement of Africans, creating a hierarchy where whiteness was associated with power and freedom. At the same time, blackness was linked to subordination and enslavement. The comingling of racialization with the institution of slavery had long-term impacts on African Americans’ social and legal rights, continuing post-abolition.Footnote 9

To many Europeans, the US symbolized the promise of expanded freedoms and opportunities for immigrants like my Norwegian ancestors. However, racial categorization significantly influenced those who enjoyed expanded freedoms in the US, including the freedom to own property, and those who did not.

1800s: American Industrial Revolution – Efficiency 1.0

The American Industrial Revolution began with the US’s first industrial factory in 1790, a water-powered textile mill in Webster, Massachusetts. This transformation drove rapid factory expansion and migration from rural to urban areas. While innovations like the cotton gin (1794) revolutionized production and boosted economic output, these advances came with stark social costs: brutal conditions for enslaved people in the South that Frederick Douglass described as nothing short of hell,Footnote 10 and factory workers labored in unsafe conditions for long hours, six days a week. Child labor was rampant, and the wages were meager, highlighting capitalism’s dual nature of wealth creation and inequality.

1870–1914: Second American Industrial Revolution – Efficiency 2.0

A wave of progress swept across America in the wake of the Civil War, spanning from 1870 to 1914. The Second American Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, brought remarkable economic advancements and significant efficiency improvements. The culmination of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, a feat of human engineering, knitted together the East and West coasts and opened new doors for trade.

Iron and steel production spiked, providing the sinews for the growing skeletal frames of ever-larger factories. Steam power proliferated. Ground-breaking strides in energy sources – petroleum and widespread electrification – breathed life into the American behemoth. Coupled with leaps in real-time communication, facilitated by telegraphs and telephones, the pace of life quickened.

Dubbed the “Gilded Age,” the period from 1870 to 1900, this period in American history showcased dazzling economic growth that masked deep societal fractures. The fledgling nation was churning out wealth, growing in influence, and earning a place on the global stage. But beneath the glittering surface, gross inequalities festered.Footnote 11 In 1890, the Danish-born Jacob Riis unveiled this stark contrast in his illuminating work, How the Other Half Lives. Riis lifted the veil on the burgeoning slums of New York City, exposing the dire conditions where countless laborers eked out their existence.Footnote 12

Henry T. Ford

In 1913, Henry T. Ford (1863–1947) revolutionized industrial efficiency by introducing the moving assembly line for mass automobile production. Inspired by Chicago’s meatpacking plants’ continuous flow of disassembling carcasses, Ford created a system that reduced automobile build time from twelve hours to just three. This era marked efficiency’s emergence as a profession, exemplified by Harvard’s first MBA program and Penn State’s industrial engineering program (both 1908). Frederick Taylor’s influential 1909 book, The Principles of Scientific Management, provided the theoretical foundation for this new approach to workplace efficiency.

Ford’s success demonstrated how private property rights and market incentives could drive innovation and efficiency in ways that centrally planned economies, like the Soviet Union, struggled to match in consumer goods manufacturing.Footnote 13

Ford’s success exemplified how private property rights and market incentives could drive innovation and efficiency. From less than half a million automobiles in 1910, ownership soared to 8 million by 1920, and the automobile would become a symbol of American freedom.Footnote 14 “Fordism” emerged as a term describing the marriage of mass production and consumption, including wage increases and broader prosperity.Footnote 15

Ford’s success embodied a core principle of American capitalism: the pursuit and accumulation of immense personal wealth. He ranked #8 on Forbes’s 1918 first-ever list of wealthiest Americans, just after J. Ogden Armour, owner of one of the Chicago meatpacking firms he benchmarked.Footnote 16

Ford’s legacy is also synonymous with American corporate social responsibility. In 1914, Ford Motor Company introduced an eight-hour workday and wages significantly above market rates,Footnote 17 two decades before the introduction of federally mandated minimum wages.Footnote 18 In contrast to the hazardous conditions prevalent in contemporary meatpacking plants, famously depicted in Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle, Ford’s factories were relatively safer work environments, reflecting a commitment to better labor conditions. Furthermore, Ford became one of the first American companies to offer partially paid health insurance in the 1930s, setting a precedent for employer-secured healthcare coverage, a unique attribute of American capitalism.Footnote 19 Ford’s financial success led to the establishment of the Ford Foundation in 1936 and serves to highlight how American capitalism commonly relies on philanthropy to address societal issues.

Ford epitomizes another aspect of American capitalism: big industry, big money, and public office intertwinement. His unsuccessful 1918 US Senate campaign, funded by vast wealth, spurred discussions on regulating political campaign financing. The preservation of wealth within families in America has led to the emergence of powerful dynasties like the Fords and the Rockefellers, and so many other names that appeared on that initial list of Forbes wealthiest individuals, the ballot box over the years, and many of which remain dynasties to this day.Footnote 20

1930s and Beyond: The New Deal – Advances in Equality

The New Deal, initiated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in response to the Great Depression following the 1929 stock market crash, marked a profound shift in American government policy toward a more active role in economic stabilization and social welfare. Key programs like the Social Security Act provided immediate economic relief and redefined the social contract between the government and its citizens, paving the way for a more inclusive approach to prosperity.

World War II dramatically reshaped American industrial capacity. The war effort created unprecedented public-private partnerships and government coordination of industry, laying the groundwork for what President Eisenhower would later term the “military-industrial complex.” This wartime experience fundamentally altered the relationship between American government and industry, with many of these coordination mechanisms persisting into peacetime and influencing Cold War industrial policy.

As World War II was nearing its brutal end, the New Deal programs were later expanded to encompass the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, popularly known as the G.I. Bill. This act extended a lifeline to returning World War II veterans, providing benefits such as tuition and living expenses for further education, medical coverage, a year’s unemployment compensation, and concessional rates for home mortgages and business loans.

These measures provided numerous Americans born into poverty in the 1920s with a real opportunity for upward mobility in the 1940s and 1950s. The prospect of higher education, business ownership, and homeownership was no longer a distant dream. With the safety net of medical coverage and unemployment insurance, many G.I.s climbed the corporate ladder or successfully ventured into politics, fueling the growth of a prosperous middle class.

In the 1940s, American capitalism underwent a moderate shift toward stakeholder capitalism. A prominent example is the Johnson & Johnson corporation, commonly known as J&J. Robert Wood Johnson, chair of J&J, crafted the “J&J Credo” in 1943. This credo delineated a commitment to stakeholders, prioritizing the needs of patients, doctors, nurses, parents, employees, and communities while acknowledging the responsibility to pay a fair share of taxes and safeguard natural resources. The concluding line signified a balance in corporate ethics. It read, “Our final responsibility is to our stockholders” and “when we operate according to these principles, the stockholders should realize a fair return.”Footnote 21

Equality … for Whom?

However, despite these advances, racial inequalities remained deeply entrenched, as many programs did not equally benefit all Americans.Footnote 22 People of color, particularly Black Americans, were too often excluded from the US’s progress. Structural barriers remained formidable, inhibiting equal access to resources like the G.I. Bill.Footnote 23 Racist practices like redlining systematically denied Black Americans the chance to own property and secure loans or insurance.Footnote 24

Slavery had been abolished a century prior but structural racism was stubbornly persistent. Gunnar Myrdal, the Swedish Nobel-laureate economist, meticulously documented this phenomenon in his 1944 account. Black Americans were caught in a vicious cycle of being systematically subjugated, often contributing to assessments of poorer performances and subsequently used as a rationale for further subjugation.Footnote 25

Violence against Black Americans was another grim reality of the time, especially for those who dared to succeed. The horrific 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre bore witness to this. In the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, known as Black Wall Street, mobs of white residents – many deputized and armed by city officials – unleashed a reign of terror on prosperous Black residents and businesses. This racially motivated violence resulted in hundreds of Black Americans being killed, many more injured, and thousands left economically devastated. This massacre was a harrowing reminder of brutal efforts to keep Black Americans “in their place.”Footnote 26

While the US was making greater strides towards equality at the aggregate level, it was a progress marred by persisting disparities along racialized lines.

1950s: American Boom, Wealth Dispersal

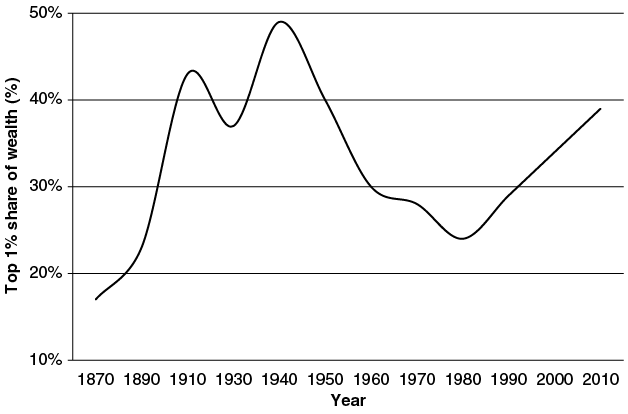

In the prosperous era of the 1950s, the US witnessed an expanding middle class, courtesy of the New Deal policies and the G.I. Bill. Wealth concentration in the US declined from just under 45 percent of total wealth held by the top 1 percent in the 1930s to below 30 percent by the 1950s, reflecting a more equitable distribution, as illustrated in Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1 Wealth inequality in the US: Share of wealth held by the top 1%.

Figure 4.1Long description

Line graph shows the share of wealth held by the top 1% of Americans from 1870 to 2010. The vertical axis ranges from 10% to 50%, while the horizontal axis spans from 1870 to 2010 in decade increments. The line starts under 20% in 1870, rises steeply through the early 20th century, peaking near 50% around 1930. It dips slightly, then peaks again in the late 1930s or early 1940s. After 1945, the line declines steadily, reaching a low around 1980, below 25%. From the 1980s onward, the line trends upward, reaching close to 40% by 2010. The overall pattern is a rise, fall, and then rise again in the top 1% share of U.S. wealth.

The ensuing era, characterized by reduced inequalities, fueled consumerism as a rising middle class yearned for modern conveniences. Technological advancements led to the production of increasingly affordable products. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 was the most significant American public works project to date, and the US Interstate Highway System further facilitated commerce and increased automobile transportation. The automobile became a potent symbol of American prosperity and freedom.

1960s–1970s: Sustainability Problems Emerge … and Denial

By the 1960s, the environmental costs of economic growth became undeniable. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring exposed both sustainability issues and the industry’s prioritization of profits over environmental concerns.Footnote 27 A New York Times review characterized Carson as “crying wolf” and engaging in “public-relations stunts,” arguing that “rising prices act as an economic signal to conserve scarce resources, providing incentives to use cheaper materials in their place, stimulating research efforts on new ways to save on resource inputs.”Footnote 28 In short, markets will solve it.

In response to Silent Spring, the chemical industry deployed the first known industry-wide coordinated denial campaign. These efforts included public relations campaigns portraying Carson as a hysterical woman and “cat-loving spinster.”Footnote 29 Strategic denial and personal attacks would become the template that the tobacco and fossil fuel industries would later follow.

The 1972 Limits to Growth by Donella Meadows and colleagues employed sophisticated computer modeling that demonstrated continued industrial growth would soon exceed Earth’s regenerative capacity for renewal (Chapter 2).Footnote 30

1980s–1990s: Market Triumph and Growing Concerns

The 1980s saw neoliberalism and its market ideology triumph globally, while environmental degradation accelerated. By the 1990s, evidence was clear that market mechanisms alone were not addressing sustainability challenges. Climate change emerged as a crucial concern, but economies were booming and corporate denial campaigns continued to delay meaningful sustainability action.

2000s: American Shareholder Capitalism in Trouble

The 2001 Enron scandal exposed the fundamental flaws of shareholder-driven American capitalism, where the pursuit of short-term profits led to corporate fraud, destroyed careers, and erased retirements, highlighting the urgent need for more responsible corporate governance.

The 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers marked a pivotal moment in the global financial crisis, triggering a severe liquidity crisis that extended far beyond Wall Street. Excessive leverage and unchecked financial speculation had created systemic risks that threatened the entire financial system. Jonathan Levy succinctly captured the severity of the situation: “In 2008, capitalism nearly collapsed.”Footnote 31

However, the American capitalist system was preserved through substantial governmental action, including injecting billions of taxpayer dollars into Wall Street institutions, banks, and other crucial sectors of the economy. Some criticized the rescue efforts as “socialism for the rich, capitalism for the poor,” harkening to Martin Luther King Jr.’s critique of American capitalism decades before. The intervention revealed the self-destructive nature of unchecked capitalism and the state’s vital role in preserving it.

Concurrently, the escalating impacts of climate change and growing inequalities have heightened scrutiny of American capitalism in practice. As American corporations grow increasingly powerful and influential, a critical reassessment of the business role in these challenges is reflected in public discourse. This reassessment found support from Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, who has advocated for stakeholder capitalism in his influential annual letters since the early 2010s. Fink’s call for balancing shareholder interests with those of other stakeholders marks a significant shift from the shareholder-centric doctrine championed by Milton Friedman. By 2019, the Business Roundtable, which includes leading US CEOs, formally embraced stakeholder capitalism, committing to prioritize broader societal interests alongside shareholder returns.Footnote 32

In 2023, California launched a landmark lawsuit against major oil companies – including ExxonMobil, BP, Chevron, Shell, and ConocoPhillips – for systematically downplaying climate change risks. This legal action, seeking compensation for future climate-related damages, signaled a broader push to hold corporations financially accountable for environmental impacts, challenging the traditional focus on shareholder value maximization.

That same year, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink’s retreat from “ESG” terminology amid accusations of promoting a “woke” agenda revealed mounting resistance to stakeholder capitalism. By 2024, this ideological conflict escalated as several US states, including Texas and Florida, sued major asset managers over their ESG strategies’ alleged impact on energy prices.

In December 2024, the underlying tensions of American capitalism erupted when the murder of UnitedHealthcare’s CEO was met with a disturbing level of public approval. The response revealed a deep erosion of public trust in American capitalism, which many had come to view as an oligarchic system protecting corporations and wealthy elites at the expense of ordinary people.Footnote 33

The erosion of American capitalism into oligarchy was laid bare at the January 2025 Trump inauguration. The world’s three wealthiest individuals – Bezos, Zuckerberg, and Musk – were seated ahead of elected officials and cabinet nominees, a striking visual cue of economic power eclipsing democratic norms. Musk’s subsequent appointment to lead the newly created Department of Government Efficiency – following a $250 million campaign contribution – underscored the consolidation of political authority by private wealth.Footnote 34 In political theory terms, this moment reflected the shift away from Madisonian principles of distributed power and checks and balances central to American democracy,Footnote 35 toward a fusion of power emblematic of oligarchic rule.Footnote 36

Nordic Capitalism: History Glimpses

The Nordic countries, though among the poorest in Europe throughout the 1700s into the 1800s, were busy laying the foundation that would enable stakeholder capitalism to flourish in the period to follow.

1800s: Nordic Property Rights and Markets

In the 1800s, the Nordics implemented a comprehensive system of property rights. By the early part of the century, land ownership extended to peasants in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Such rights to property set in motion a significant shift in agriculture in Sweden, where the newly anointed landowners utilized various means like crop rotation, trenching, and stone removal to enhance productivity.Footnote 37

Unlike American capitalism, the Nordic model was not significantly shaped by the institution of slavery on domestic soils. As noted by Líndal Sigurður, the Nordic nations largely eradicated slavery by the thirteenth century.Footnote 38 Nevertheless, the Nordic nations still played a role in the grim history of slavery, as exemplified by Denmark’s colonization of the former Danish West Indies and benefiting from trading in goods derived from the labor of enslaved people.Footnote 39

By the 1840s, Sweden sold timber-rich land to private entities, boosting tax revenue.Footnote 40 Rising foreign interest in Nordic natural resources, especially from the US, significantly fueled economic growth through burgeoning trade relationships. Concurrently, robust patent laws were being established and anti-corruption measures were enforced, further strengthening the Nordic economic foundation.

The expansion of financial institutions and liberal lending practices in the 1800s marked a critical step in Nordic capitalism’s evolution. More individuals were able to participate in market activities, secure credit, and invest in real estate and businesses.Footnote 41

1800s Nordic Education, Folk Schools, and Bildung

Despite relative poverty, the Nordic countries were pioneers in education during the 1800s. As early as 1814, Denmark introduced compulsory elementary education, a practice soon adopted by Norway and Sweden. This Nordic commitment to universal education played an instrumental role in shaping their modern societies.

Central to their educational philosophy were folk schools, underpinned by the German concept of “Bildung.” Bildung, a term with no direct English translation, encompasses the idea of personal growth combined with social responsibility to oneself, the community, and the world. The ethos of Bildung would prove to be a moral compass guiding the pragmatic development of Nordic capitalism in the century-plus to follow, giving rise to a version of democratic capitalism, commonly called stakeholder capitalism, we recognize in practice in the Nordics today.

N. F. S. Grundtvig

Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig (1783–1872), a Danish philosopher and pastor, is as pivotal to Nordic capitalism as Henry Ford is to the American variety. Grundtvig’s philosophy and vision for education helped transform Denmark from an oligarchic monarchy into a dynamic democracy, embedding democratic principles at the core of Nordic capitalism.

Central to Grundtvig’s philosophy was establishing “folk schools” – educational institutions for the many people, the peasants. Frustrated with the elitism of classical education, which he viewed as alienating and impractical, Grundtvig revolutionized education in Denmark, promoting an egalitarian path crucial in shaping democratic practices in Nordic capitalism. He aimed to cultivate an informed and engaged citizenry capable of wielding their newfound democratic powers responsibly.Footnote 42

Grundtvig’s educational philosophy, centered on the concept of “Bildung,” emphasized individual growth in service to the community and society. Bildung’s holistic approach to learning underpins many of the cooperative and democratic institutions in modern Nordic capitalism. As Lene Rachel Andersen explained in The Nordic Secret, Bildung is about “maturing and taking upon oneself ever-bigger personal responsibility,” and it “forces us to grow and change … it is being an active citizen in adulthood.”Footnote 43

Grundtvig’s educational vision first materialized in 1844 with the establishment of Rødding Folkehøjskole, inaugurating an institutional model that would transform Nordic civil society. The folk schools created unprecedented spaces for adult education that transcended traditional class boundaries, particularly significant in rural communities. Typically organized around four six-month terms, these institutions proved instrumental in cultivating democratic competencies among populations previously excluded from formal education, that is to say, peasants, effectively bridging the gap between theoretical democratic rights and meaningful democratic participation.Footnote 44

Grundtvig’s humanistic philosophy emphasized democratic problem-solving and human potential. His belief in the inherent goodness of people is encapsulated in his 1837 poem, “Human First” (“Menneske Først”).Footnote 45 This humanistic perspective has profoundly impacted the region’s approach to capitalism, as seen in the cooperative movement. Cooperatives are for-profit organizational structures founded on democratic principles that have further diffused power across Nordic societies.

The lasting influence of Grundtvig’s philosophy is evident in contemporary Nordic society. Take, for instance, Lars Rebien Sørensen, former CEO of Novo Nordisk. In response to being named the Best-Performing CEO of the Year in 2015 by the Harvard Business Review, Sørensen’s comments mirror Grundtvig’s offerings. When the magazine asked, “Scandinavian CEOs are paid much less than US CEOs. Does that influence how you lead?” Sørensen responded, “I saw that in last year’s list of best-performing CEOs, I was one of the lowest paid. My pay is a reflection of our company’s desire to have internal cohesion. When we make decisions, the employees should be part of the journey and should know they’re not just filling my pockets.”Footnote 46

When Sørensen was asked for further lessons to share as the newly minted CEO of the Year, he responded in a manner consistent with Grundtvig’s offerings, eschewing individualistic praise while emphasizing the importance of fostering shared prosperity. He stated:

I should have said at the beginning that I don’t like this notion of the “best-performing CEO in the world.” That’s an American perspective – you lionize individuals. I would say I’m leading a team that is collectively creating one of the world’s best-performing companies.Footnote 47

US President Barack Obama acknowledged Grundtvig’s legacy, citing its influence on the American Civil Rights Movement through the folk school movement in the United States. At the Nordic Summit convened in Washington, DC, with Nordic heads of state in 2016, Obama offered, “Many of our Nordic friends are familiar with the great Danish pastor and philosopher Grundtvig. And among other causes, he championed the idea of the folk school – education that was not just made available to the elite but for the many; training that prepared a person for active citizenship that improves society.”Footnote 48 Obama pointed out that notable civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., were influenced by the teachings of Grundtvig, and offered:

Over time, the folk school movement spread, including here to the United States. And one of those schools was in the state of Tennessee – it was called the Highlander Folk School. At Highlander, especially during the 1950s, a new generation of Americans came together to share their ideas and strategies for advancing civil rights, for advancing equality, and for advancing justice. We know the names of some of those who were trained or participated in the Highlander School. Ralph Abernathy. John Lewis. [Rosa Parks.] Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.Footnote 49

Grundtvig’s folk schools helped spark a cooperative movement that would fundamentally reshape Nordic societies. By diffusing ownership and power across societies, cooperatives have played a key role in fostering stakeholder capitalism in the region.Footnote 50 As Danish scholar Anders Holm put it, Grundtvig’s influence on Denmark is unparalleled. He likened him to a combination of George Washington, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Benjamin Franklin, and Martin Luther King Jr., underscoring Grundtvig’s lasting impact on Danish society.Footnote 51

1870s–1900: Nordic Industrial Revolution and the Seeds of the Nordic Social Democracies

The Industrial Revolution is commonly described as having arrived in the Nordic region around 1870, lagging England by over a century, the US by about eighty years, and Germany by some 40 years or so. The Nordic nations proved themselves attentive benchmarkers, learning from the successes and failures of industrialization elsewhere and corresponding developments.Footnote 52

In the 1880s, Germany introduced pioneering social insurance laws under Otto von Bismarck that have proven foundational to the concept of the modern welfare state. Legislation included national sickness, accident, and old-age insurance (pension).Footnote 53 These reforms were significant because they represented one of the first systematic efforts by a state to provide social protection to its citizens on a national scale, thereby setting precedents for what would later be recognized as key components of welfare states. The Nordic nations were closely watching.

From the 1890s to the early 1900s, the Nordics followed Germany’s lead and began establishing social security systems for accident, sickness, unemployment, and old-age insurance (pension) to mitigate risk at the societal scale. Although these programs were not universally accessible, they marked a crucial step towards creating a more comprehensive social safety net.Footnote 54

Reading Marx but (Eventually) Rejecting Marxism

By 1870, Nordic citizens had more than two decades to digest Marx and Engels’ ideas presented in their 1848 work, The Communist Manifesto, and to consider and critique the varieties of capitalism developing in England and the US. While the monumental strides in efficiency seen in the US and England during the Industrial Revolution were compelling, the corresponding social dilemmas and unequal distribution of wealth were undeniable. As Marx’s influence burgeoned across Europe, labor was organizing itself, and the Nordics were attentive observers.

From 1870 onwards, many Nordics self-identified as socialists or social democrats, ideologies rooted in Marx and Engels’s assertion that industrialization engenders enormous wealth for capitalists at the potential cost of labor exploitation. However, a notable divergence existed between socialists and social democrats. While the former adhered to Marx’s call for a violent revolution to seize control of the means of production, the latter espoused a more cooperative, consensus-based approach, seeking system reform without eradicating private ownership.

The labor movement gained considerable momentum across the Nordics in the late 1800s. The elite capitalist class grew anxious about possible labor radicalization as union membership burgeoned. Like their American counterparts, Nordic capitalists initially sought to assuage these fears through philanthropy. However, as Brandal, Bratberg, and Thorsen stated, the philanthropic organizations established in the early 1870s aimed to improve working-class conditions and distance workers from political radicalism had largely vanished by 1900.Footnote 55

Under mounting pressure from socialists and the looming threat of a socialist revolution, Nordic capitalists became increasingly compelled to engage with the reform-minded, consensus-oriented social democrats. During the 1890s, labor unions and the social democratic movement formed a powerful alliance, gaining political sway across the Nordics.Footnote 56 Socialists played a crucial role in applying the pressure needed for Nordic capitalists to compromise and engage constructively with social democratic elements of the labor movement.

A pivotal moment arrived in 1896 when Niels Andersen, a Danish Member of Parliament and railroad entrepreneur, founded the Confederation of Danish Employers (DA). The DA both counteracted the growing power of labor unions and served as a centralized entity for potential national collective bargaining. By 1907, a national collective bargaining arrangement was established, ensuring fair profit distribution to labor (and negating the need for minimum wage laws).Footnote 57

It may appear counterintuitive that capitalists would support robust collective bargaining, yet this cooperation has fostered social stability and economic efficiency in the Nordic context. The capitalist ethos, after all, revolves around maximizing profits, which might involve paying laborers lower wages. In the Nordic countries, a unique consensus emerged between capitalists and laborers on the mutual benefits of collaboration, fostering a more stable and inclusive economic environment. They saw the value in instituting structures and norms that would circumvent costly conflicts and better ensure shared societal prosperity. This led to the development of robust consensus-building mechanisms.Footnote 58

1900–1930s: Social Democrats Gaining Power

During this era, social democrats steadily amassed power across the Nordics, while navigating pressure from revolutionary socialist factions. By the dawn of the twentieth century, the social democrats had secured a relatively robust footing, their cause fortified by influential pioneers like P. Knudsen of Denmark, Sweden’s Hjalmar Branting, and Christian Holtermann Knudsen from Norway. The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia heightened concerns among Nordic capitalists about the spread of revolutionary socialism.Footnote 59

The journey to democratic stability in the Nordic nations was marked by considerable turbulence in the early twentieth century. In 1920. Denmark experienced a serious constitutional crisis known as the Easter Crisis (Påskekrisen), when King Christian X attempted to dismiss the democratically elected government and install a conservative government aligned with his preferences. This last-ditch effort by the monarchy to reassert control was met with strong popular resistance, including threats of a general strike. The crisis represented a crucial test of Denmark’s democratic institutions. When the king backed down, it marked a decisive victory for the principle of parliamentary democracy.Footnote 60

Finland faced the most severe democratic test during the Finnish Civil War of 1918, shortly after declaring independence from Russia. The conflict between socialist “Reds” and conservative “Whites” ended in a White victory that consolidated parliamentary democracy but exposed deep societal divisions. Sweden’s transition to democracy, while relatively peaceful, involved significant political struggles before universal suffrage was finally achieved in 1921. Norway’s democratic institutions were tested during its 1905 separation from Sweden, though the transition was ultimately peaceful and resulted in a stable constitutional monarchy. Iceland’s path to democracy was comparatively smooth, achieved through gradual independence from Denmark (sovereign state in 1918, full independence in 1944).Footnote 61

The influence of the Soviet Union cast a long shadow across the region during this period. In 1919, Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin convened the third annual Communist International (Comintern) organization gathering in Moscow. During this assembly, attended by the Norwegian Labor Party, Lenin declared social democrats to be strategic adversaries to socialists, given their willingness to cooperate with capitalist forces. He argued that nothing short of a socialist revolution, as outlined by Marx, would suffice in overthrowing capitalist structures.Footnote 62 Ironically, the threat of revolutionary socialism ultimately encouraged more constructive engagement between Nordic capitalists and reform-minded social democrats.

Amid ongoing pressure from more radical socialist elements, the Nordic region remained steadfast in its commitment to social democracy and democratic means, increasingly distancing itself from the Soviet Union’s authoritarian path.

In Denmark, social democrats had garnered 37 percent of the vote by 1924, becoming the largest party in parliament for the first time.Footnote 63 This electoral success owed much to the leadership of Thorvald Stauning, who served as prime minister from 1924 to 1942, making him Denmark’s longest-serving prime minister. Stauning’s political acumen proved crucial in building the foundations of Danish social democracy, particularly evident in the landmark Kanslergade Agreement (Kanslergadeforliget) of 1933. Named after Stauning’s apartment in Copenhagen, where the negotiations took place (allegedly over copious amounts of beer into the early morning), this agreement brought together Social Democrats, liberals, and conservatives to establish comprehensive social reforms during the Great Depression.Footnote 64 The agreement exemplified the cross-party cooperation necessary to serve broader societal interests, a distinctive feature that would come to characterize Nordic social democracies.

Sweden was also gaining recognition as a leader within the burgeoning social democracy movement.Footnote 65 The economist Thomas Piketty referred to Sweden as “the quintessential social democracy,” lauding its commitment to equitable prosperity. He described this as a compelling case study in rapid societal change, noting that a mere decade before its transformative reforms of 1910–1911, Sweden was one of the world’s most inegalitarian societies.Footnote 66 These reforms demonstrated a stark turnaround, making Sweden an emblematic figure in the social democracy landscape.

1930s–1950s: Nordic Model Taking Shape

The Nordic model began to take its modern form in the 1930s, gradually growing over the years to include state-supported healthcare, old-age and disability pensions, income maintenance during occupational injury, sickness, and unemployment, and mechanisms to ensure fair wages, such as collective bargaining structures.Footnote 67 Referred to interchangeably as the “welfare state” or the “well-being state,”Footnote 68 the Nordic Model’s primary goal, as argued by Brandal and his colleagues in The Nordic Model of Social Democracy, is to promote individual freedom.Footnote 69

The People’s Home

At the heart of Sweden’s social democratic movement lies the concept of “People’s Home” or folkhemmet. In a pivotal speech in 1928, Swedish social democrat Per Albin Hansson, who would assume the prime minister’s role from 1932 to 1946, introduced this metaphor, sketching a vision that would shape the decades to come.

In his vision, Hansson imagined Swedish society as an inclusive “home,” where everyone had a place and contributed productively. In this “home,” class and economic disparities were minimized, and social care services, such as disability and unemployment insurance, were accessible to all. It was a family-like society, where individual work ethic intertwined with collective responsibility.

Social democrats championed the integration of democratic principles in many aspects of life, particularly through industrial democracy, which empowered workers to share in decision-making and governance. Hansson proposed a policy of cooperation and mutual understanding as a key to a better society.Footnote 70 In his People’s Home speech, he asserted that workers should have an increased role in decision-making processes in cooperation with capital owners:

If one obstinately perceives the worker merely as a rented creature from whom to extract as much as possible with the least possible compensation, no progress towards a better order can be achieved. But, if one recognizes the worker as a valuable colleague and participant, not only in work but also in administration, management, and profit, it’s worth investigating how far consensus, common interests, and cooperation can take us.Footnote 71

Hansson advocated for respect, dignity, and power-sharing between capitalists and workers. During this time, the influence of the Soviet Union and socialist movements was considerable. The tension was palpable, highlighted by the tragic incident in 1931 when Swedish military forces opened fire on labor demonstrators in Ådalen, leading to five casualties.Footnote 72 Despite a history punctuated by significant conflicts and struggles, political leaders and Nordic capitalists recognized the urgency to foster a culture of consensus-building and establish power-sharing structures between capitalists and labor. This was not only to mitigate the brewing tensions but also to prevent further fueling of Marxist socialism.

The Middle Way?

US journalist Marquis W. Childs, in his seminal 1936 work Sweden: The Middle Way on Trial, introduced a global audience to Nordic capitalism (Prologue). Within it, Childs lauded Sweden and Denmark for their remarkable ability to temper “the rapacity of big business,” whilst ensuring “decent living conditions for the working population,” and fostering an innovative and efficient environment for industry.Footnote 73

What particularly intrigued Childs was the democratic foundation of the Nordic variant of capitalism, exemplified in the flourishing cooperative movement where organizational structures for commerce were built upon democratic principles. His admiration extended to Danish educator and religious leader Grundtvig. In Childs’s eyes, Grundtvig was “that extraordinary national hero” who had not only “taught the Danes cooperation,” but had also “schooled them in the use of the instruments of democracy, both political and economic.”Footnote 74

After closely observing and understanding the Nordic model, Childs contrasted it with American capitalism. The latter, he felt, suffered from an overemphasis on the profit motive, that would eventually lead to “blind self-destruction.”Footnote 75 By contrast, the Nordics offered a sense of balance and harmony. Childs observed that the state in Sweden was far more active than in the US, yet less invasive than Soviet socialism. This balanced approach earned Sweden the title of “the middle way” in his view.

World War II’s impact on the Nordic region varied significantly, with Denmark and Norway under German occupation while Sweden maintained neutrality. The post-war reconstruction period saw these nations channel the lessons of wartime economic coordination toward civilian production and social welfare programs. Unlike America’s maintained military-industrial focus, the Nordic countries developed robust public–private partnerships focused on domestic social development and civilian industrial policy.

1950s–1970: Commitment to Universalism

In the aftermath of Childs directing the global spotlight onto Nordic capitalism, a fascinating “second wave of Nordic welfare legislation” began to unfurl characterized by universalism. As Mary Hilson outlines in her book The Nordic Model, prior welfare expansions, while ambitious, were not always universal. The “wage-earner” model prevalent before the 1950s, tied social insurance eligibility to wage-earning employment, leaving many, such as home workers, small-business owners, seasonal workers, and numerous farmers, out in the cold.Footnote 76

From the 1950s, the Nordic model underwent a significant shift, with universalism becoming the default. Universalism is today widely recognized as a defining characteristic of the Nordic model, credited with fostering social cohesion. Importantly, universal social programs avoided divisive “othering,” such as the portrayal of one group burdened by another – think “rich paying for the poor.” In this way, universalism reduced the impact of political whims on social programs, creating a shared project that all political parties and citizens could embrace.

The 1950s also saw the implementation of robust data-collection systems, which served as the keystone for evidence-based decision-making. Nordic healthcare systems provide a vivid example of individual-level data collection ensuring the quality and efficiency of care. This has led to the creation of high-quality longitudinal datasets dating back to the 1950s for every citizen, making Nordic societies known as an epidemiologist’s dream.Footnote 77

Over the decades, Nordic model builders proved themselves to be pragmatic above all else. Hugh Heclo and Henrik Madsen captured this essence with their characterization of the Swedish approach as “principled pragmatism.”Footnote 78 This pragmatism shaped their approach to capitalism, pragmatically using markets where effective, but seeking alternatives where markets failed. It was evident in their approach to healthcare, where they opted for efficient, universal healthcare systems and education when market solutions fell short.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, in the US an ideological discourse around universal healthcare was emerging. In the 1960s, Ronald Reagan famously argued against the adoption of universal healthcare, claiming it would lead toward Soviet-style socialism and erode personal freedoms, reflecting the intense ideological debates of the period. Reagan offered a radio address in 1961 as a spokesperson for the American Medical Association, stating, “One of the traditional methods of imposing statism, or socialism, on a people has been by way of medicine.”Footnote 79 He added, if universal healthcare became policy, “we will awake to find that we have socialism … and you and I are going to spend our sunset years telling our children, and our children’s children, what it once was like in America when men were free.”Footnote 80

Nordic societies largely avoided ideological labeling, instead pragmatically evaluating policies and programs based on their effectiveness. The Nordic model’s benefits were acknowledged across the political spectrum, with even Danish conservatives boasting about their role in the welfare state’s expansion during the 1960s.Footnote 81 Although debates were common, the broad support for universal safety nets underscored the welfare state’s practical benefits to Nordic societies. This pragmatic approach has been seen as a key factor in their success in recent generations.

1970s–1980s: The Nordic Model on Trial

By the 1970s, the mounting environmental costs of industrialization were too conspicuous to ignore in the Nordics, similar to elsewhere. Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss led a burgeoning environmental movement in the Nordics rooted in the concept of Deep Ecology,Footnote 82 and the Nordic nations established national environmental protection agencies to address the mounting environmental crises (Chapter 2).Footnote 83

The 1973–1974 oil crisis severely tested the Nordic model, particularly in Sweden. The country’s response of raising tax rates to extreme levels (Astrid Lindgren famously faced a 102 percent rate) triggered high-profile exits, including IKEA founder Ingvar Kamprad, filmmaker Ingmar Bergman, tennis star Björn Borg, and members of the celebrated Swedish musical group ABBA.

In 1980, Childs authored Sweden: The Middle Way on Trial, revisiting the Nordic model as its imperfections were on full global display and leveraging the publicity of prominent figures like Astrid Lindgren and Ingmar Bergman. Childs critically addressed the stifling tax rates that undermined economic efficiency.Footnote 84 Like Childs, Staffan Marklund’s Paradise Lost scrutinizes the Nordic region from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, charting its shift from an idealized beacon to a region grappling with real challenges. Marklund portrays not a collapse but a tempered view, recognizing significant flaws and the ongoing necessity for adaptation.Footnote 85

Childs, revising his earlier, at times utopian portrayal of the Nordic model, adopts a more critical yet hopeful stance. While acknowledging issues, he remained optimistic about Sweden’s capacity to address contemporary challenges. This sentiment is echoed in a contemporary review, suggesting, “if any country can solve these modern problems…then it will be Sweden.”Footnote 86 The period invited more nuanced discussions of the Nordics, highlighting the achievements and the trials of the Nordic model.

1990s: Continued Challenges but Nordics Emerging Stronger

After recalibrating its tax levels to a more reasonable level, Sweden eventually bounced back in the 1990s to again be considered a successful system. However, it was not without a financial crisis, first coming in the early 1990s. The largest Nordic banks were shaken by a fundamental financial crisis, and Sweden and Finland were hit particularly hard, experiencing consecutive years of negative economic growth.

Nevertheless, by the mid 1990s, the Nordic model, although shaken, found its footing again and was increasingly hailed as a model of success. The continued strength of Nordic democracies has proven effective in recalibrating to achieve a “democratic balance of opinion,” according to Peter Linder, after periods of disagreement and discontent.Footnote 87

Flexicurity

“Flexicurity” – a term coined by Danish Prime Minister Poul Nyrup Rasmussen in the 1990s – represents a crucial innovation in democratic capitalism that directly supports sustainability transitions. The system combines labor market flexibility with comprehensive social security.

Flexicurity captures citizens’ sense of security due to their ability to navigate the capricious global landscape. With universally available services such as lifelong education, training, and safety nets like universal healthcare, the fear of losing everything due to job loss is significantly mitigated. Flexicurity promotes adaptability and resilience, resulting in a broad sense of societal security. As market dynamics shift in Denmark, workers can easily enter or exit jobs. But, crucially, retraining and education are always there to prepare them for new opportunities.

While each Nordic nation has its unique set of policies, the overarching philosophy of flexicurity is common to all. This means people are less inclined to hold onto outdated jobs or succumb to anxiety about change. Instead, change is met with optimism, fostering a societal-level growth mindset.Footnote 88

A central tenet of flexicurity, and the Nordic model as a whole, is the high labor participation rate. As economist Torben Andersen succinctly puts it, “The Nordic model can also be characterized as an employment model.” The financial stability of this system hinges upon people’s ability to pay taxes, which in turn supports education, retraining programs, and social safety nets. This active labor policy helps create good jobs that pay well, reducing the prevalence of the working poor and fortifying the middle class.Footnote 89

2000s On: The Next Supermodel

By the early 2000s, the Nordic model reemerged as a widely regarded example of economic and social success. In 2013, The Economist featured a special issue titled “The Nordic Countries: The Next Supermodel,” underscoring how Nordic capitalism, deeply rooted in democratic principles, continues to promote shared prosperity.

Americans were introduced to the democratic underpinnings of Nordic capitalism as early as the mid twentieth century through Childs’ seminal work, Sweden: The Middle Way on Trial. However, Childs’ portrayal of Sweden as a compromise between American capitalism and Soviet socialism unintentionally reinforced a misconception that Nordic capitalism was merely a step toward Soviet-style centralization. This mischaracterization persists in some contemporary discussions, where Nordic countries are mistakenly labeled socialist states. In contrast, the role of the State in the Nordics is characterized by transparency, efficiency, and democratic accountability – distinct from the authoritarianism associated with the Soviet model.

Nordic capitalism exemplifies democratic principles through institutions designed to distribute power across society. Strong labor unions, robust cooperative movements, and inclusive social policies ensure that the state remains responsive to the democratic will of its citizens. However, this model did not emerge without tension. Facing the specter of socialist revolution, the Nordic economic elite was compelled to cede some of their power. Today, their descendants benefit from a more equitable and cohesive society – a testament to the strength of democratic capitalism in the Nordic context.Footnote 90

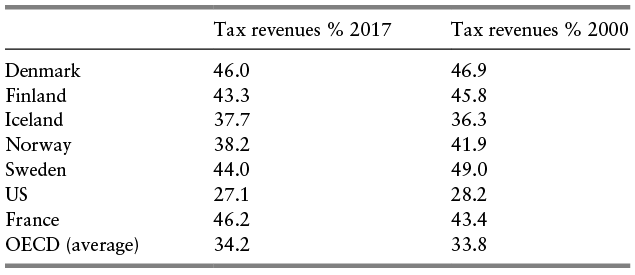

American Philanthropy and Nordic Taxes

The US and Nordic approaches to addressing societal issues reflect fundamentally different paradigms. The US system, through tax deductions for charitable giving, empowers private property owners to address social needs through philanthropy – exemplified by institutions like the Ford Foundation. Nordic societies, by contrast, fund comprehensive public services through higher taxation, as shown in Table 4.1. When these taxes deliver efficient services, Nordic citizens generally view them as worthwhile investments.Footnote 91

| Tax revenues % 2017 | Tax revenues % 2000 | |

|---|---|---|

| Denmark | 46.0 | 46.9 |

| Finland | 43.3 | 45.8 |

| Iceland | 37.7 | 36.3 |

| Norway | 38.2 | 41.9 |

| Sweden | 44.0 | 49.0 |

| US | 27.1 | 28.2 |

| France | 46.2 | 43.4 |

| OECD (average) | 34.2 | 33.8 |

Critics of capitalism, from Oscar Wilde to Martin Luther King Jr., have argued that philanthropy represents a fundamental flaw in capitalism rather than a virtue. Wilde contended that philanthropic remedies “merely prolong” rather than cure societal ills,Footnote 92 while King warned that philanthropy must not obscure “the circumstances of economic injustice which make philanthropy necessary.”Footnote 93

Policies and Stakeholder Capitalism

The call for stakeholder capitalism by the US CEOs of the Business Roundtable American business leaders is laudable but remains largely unsupported by necessary policy changes. As Anu Partanen suggested in her 2019 New York Times feature, Nordic business leaders have long embraced a stakeholder view of the firm that includes their longstanding support of policies related to robust universal public services. “What Nordic businesses do is focus on business – including good-faith negotiations with their unions – while letting citizens vote for politicians who use government to deliver a set of robust universal public services,” Partanen wrote.Footnote 94

In 2019, I was invited to testify at a US congressional hearing hosted by the Small and Medium-Sized Business Committee. The hearing centered on the Business Roundtable’s recent endorsement of a stakeholder view of the corporation, signaling a departure from Milton Friedman’s doctrine of corporate purpose as profit maximization for shareholders.

I recognized the promising change in the discourse by American business leaders. Yet, I stressed the need for impactful policy and practice changes to make the stakeholder concept a reality. Drawing upon Nordic nations’ comprehensive social policies, including paid parental leave and accessible quality healthcare, and the Nordic business community’s widespread support for them, I argued these Nordic policies could provide inspiration and good examples for successfully implementing a version of stakeholder capitalism in the US. This approach could allow US businesses, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises, to focus on their core activities without the burden of providing extensive employee benefits.Footnote 95

My proposals, however, faced resistance. For instance, Representative Jim Hagedorn championed American capitalism as unrivaled, viewing any deviation as anti-capitalistic. “Now, Mr. Strand,” he began, “I wanted to talk with you about your testimony because I was concerned that it was going against capitalism and undercutting some of the things that we’ve proven in the United States with our free enterprise capitalist system that really is – there is no better system.” His counterpoint lauded American capitalism as superior on the global stage and crediting it for the majority of all global innovation and providing American citizens with cheap energy. He concluded, “If it weren’t for the United States, which I would subscribe that we’ve done more for the world than the world has done for us, where would we be? And I think it’s most all because of our system of free enterprise capitalism.”Footnote 96

Such viewpoints tend to disregard certain facts, such as the heavy subsidies granted to fossil fuel corporations in the US who also frequently pay no federal taxes,Footnote 97 and the significant negative externalities related to the production and consumption of fossil fuels that go uninternalized in the prices, making fossil fuel prices cheaper than the costs fossil fuels inflict on society and future generations of people not yet born.Footnote 98 It also overlooks the energy innovations from Nordic countries like Denmark, which has become a global leader in wind energy production.Footnote 99

Despite these diverse perspectives, our shared global challenges provide a potential platform for unity. In retrospect, during my testimony, none of us could have predicted the imminent global Covid-19 pandemic or its potent demonstration of our global interdependence, and a Nordic innovation would prove central to saving millions of lives in the US and worldwide. The modern ventilator resulted from a series of Nordic innovations involving the medical innovation of pressure ventilation by Danish physician Bjørn Ibsen and its mechanization by the Swedish company Engström.Footnote 100 This case exemplifies how we benefit from innovations, regardless of their origin.

As debates around the future of capitalism evolve, Danish political leader Peter Hummelgaard’s book Den Syge Kapitalisme (The Sick Capitalism) critically reflects on changes in the Nordic landscape. Hummelgaard offers a stark warning about the gradual adoption of American-style neoliberal policies that amount to what he terms “sick capitalism.” He cautions that capitalism in Denmark is increasingly taking on the appearance of American capitalism with market deregulation and firms discussing profit maximization. This shift, he argues, poses significant risks to Denmark’s traditionally inclusive and cooperative economic practices rooted in democratic principles. Hummelgaard emphasizes that a continued neoliberal trajectory could exacerbate socioeconomic inequality and concentrate power among a wealthy elite, thereby undermining the democratic foundations of Danish society that have been integral to the success of the Nordic model. His offerings align with broader concerns associated with oligarchic capitalism and advocate for a focus on strengthening democratic capitalism.Footnote 101

The varieties of capitalism in practice throughout the world present a rich opportunity to learn from policy innovations irrespective of their origins. The rising interest in stakeholder capitalism in the US logically leads us to study the experiences of regions that have practiced stakeholder capitalism, like the Nordics.

Democracy: The Essential Foundation for Capitalism

The parallel histories of American and Nordic capitalism reveal a crucial lesson: capitalism requires robust democratic institutions and public accountability to function well. When democratic oversight erodes, capitalism often veers into dangerous territory – undermining human welfare, public trust, social stability, and the efficient functioning of markets.

Early American capitalism offers stark examples. Before democratic pressure led to federal regulation, profit-seeking behavior frequently endangered public health. In the late nineteenth century, milk sellers commonly adulterated spoiled milk with chalk or plaster of Paris to mask its condition – contributing to alarmingly high infant mortality rates in American cities. The horrific conditions in Chicago’s meatpacking industry, exposed in Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle (1906), revealed how unregulated capitalism prioritized profits over basic food safety. Public outrage prompted Congress to enact the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act in 1906, establishing the Food and Drug Administration – an institution born from democratic demands to hold markets accountable.

The tragedy of the Radium Girls in the 1920s further illustrates this dynamic. Factory workers who painted watch dials with radioactive paint were falsely assured the substance was safe, leading to devastating health consequences, including painful bone deterioration and fatal cancers. It was only through democratic action – spurred by investigative journalism, public outcry, and legislative intervention – that occupational safety standards were strengthened. In each case, it was not market forces but democratic institutions that corrected course. Significantly, these reforms did not impede capitalism but rather legitimized and stabilized it by aligning market activity with public welfare.

The Nordic countries, by contrast, embedded democratic accountability into their economic framework from the outset. Their experience demonstrates that capitalism need not be predatory when constrained and guided by democratic institutions. Strong labor unions, universal social systems, and stakeholder-oriented governance structures help ensure that market outcomes reflect broader societal interests. This democratic foundation has made Nordic capitalism both resilient and equitable, while still fostering economic dynamism.

Recent trends in American capitalism – marked by the oligarchic concentration of wealth and corporate power – underscore the ongoing importance of democratic guardrails. As public accountability weakens, familiar problems resurface: environmental degradation, unequal access to healthcare, and exploitative labor practices. The Nordic experience offers compelling evidence that capitalism functions best when tethered to democratic institutions capable of checking concentrated power and protecting the public interest.

Parting Reflections

American and Nordic capitalisms have distinct histories, illustrating the broad spectrum of possible capitalist systems. While both systems recognize private property rights as fundamental, they differ markedly in how these rights are balanced against broader societal interests. American capitalism has demonstrated a remarkable capacity for innovation and economic growth, but its tendency toward concentrated power and wealth increasingly threatens its democratic foundations. In contrast, Nordic capitalism disperses power more consistently with democratic ideals through structures like strong unions and universal social systems, exemplifying democratic capitalism.

A key lesson from Nordic capitalism is how it combines democratic deliberation with practical problem-solving: Government policies emerge through democratically rooted dialogue between diverse stakeholders and are continuously refined with attention to efficiency based on evidence rather than ideology. As The Economist emphasized in its 2013 special issue on the Nordics, “The main lesson to learn from the Nordics is not ideological but practical. The state is popular not because it is big, but because it works. A Swede pays taxes more willingly than a Californian because he gets decent schools and free health care.”Footnote 102 This pragmatism has helped the Nordic nations consistently top global rankings, including the SDG Index. Though Nordic capitalism has faced challenges, its democratic foundations – built on structures and norms of cooperation and consensus-building – have repeatedly enabled successful adaptation to changing circumstances.

While Nordic capitalism is not yet sustainable, it possesses the essential ingredient to realize sustainable capitalism: a strong democratic foundation.