Introduction

Effective early season weed control is necessary for maximizing soybean yield, and residual herbicides are essential to achieving this goal by limiting weed interference during early crop development (DeWerff et al. Reference DeWerff, Conley, Colquhoun and Davis2015; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Landau, Williams and Hager2025). This early season weed control is essential for soybean yield, because a delayed application of postemergence herbicides could result in yield losses as early as 6 d after emergence, with declines ranging from 1% to 50%, depending on delays in weed removal occurring between 6 and 41 d after emergence (Soltani et al. Reference Soltani, Shropshire and Sikkema2022). When applied at planting, residual herbicides can significantly limit early season weed interference, providing critical control that reduces exclusive reliance on postemergence options (de Sanctis et al. Reference de Sanctis, Barnes, Knezevic, Kumar and Jhala2021). However, the duration and effectiveness of this control depend not only on the herbicide’s persistence in the soil but also on the composition of the weed community and the susceptibility of dominant species to the active ingredients applied (Shaner Reference Shaner2012). Residual herbicides gradually dissipate, reducing their weed-suppressing activity over time (Bedmar et al. Reference Bedmar, Gimenez, Costa and Daniel2017). The rate and extent of this dissipation will determine how long effective weed control will last, which can affect season-long weed management success (Ribeiro et al. Reference Ribeiro, Oliveira, Smith, Santos and Werle2021).

Herbicide dissipation encompasses all processes that reduce soil herbicide concentration, including degradation, volatilization, leaching, and surface runoff. Whereas degradation involves a structural transformation of the herbicide molecule into metabolites through chemical or microbial processes, dissipation also includes physical transport mechanisms that relocate the herbicide without altering its chemical form (Mueller and Senseman Reference Mueller and Senseman2015). Herbicide persistence, the inverse of dissipation, indicates how long a molecule remains in the soil, and it is determined by sorption, volatilization, leaching, and degradation processes that regulate its concentration and movement within the soil solution (Mueller and Senseman Reference Mueller and Senseman2015; Taylor-Lovell et al. Reference Taylor-Lovell, Sims and Wax2002). In summary, a dynamic interaction between soil characteristics and environmental factors influences herbicide behavior and persistence (Eason et al. Reference Eason, Grey, Cabrera, Basinger and Hurdle2022). These environmental shifts are particularly important given recent changes in soybean production practices driven by climate trends and advances in planting technology, including ultra-early planting dates (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Landau, Williams and Hager2025).

Imazethapyr is an acetolactate synthase inhibitor (categorized as a Group 2 herbicide by the Herbicide Resistance Action Network and Weed Science Society of America [WSSA]) used to control annual broadleaf and grass weeds (Shaner Reference Shaner2014). Binding of imazethapyr to soil is generally weak, although adsorption increases with higher organic matter and clay content. Adsorption also increases over time and as the soil dries, although sorption remains reversible (Shaner Reference Shaner2014). Its persistence is highly influenced by environmental factors such as soil moisture and microbial activity (Cantwell et al. Reference Cantwell, Liebl and Slife1989), with a half-life ranging from approximately 56 to 100 d under field conditions (Curran et al. Reference Curran, Liebl and Simmons1992).

S-metolachlor (WSSA Group 15) inhibits very-long-chain fatty acids and is an important selective residual herbicide used for control of annual grass and small-seeded broadleaf weeds in a wide range of crops (Shaner et al. Reference Shaner, Brunk, Belles, Westra and Nissen2006).The half-life of S-metolachlor in soil varies from 15 to 50 d and tends to bind more strongly in clay and organic-rich soils and is more likely to leach out of the weed-seed zone in sandy soils with low organic matter (Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Tzilivakis, Warner and Green2016; Westra et al. Reference Westra, Shaner, Barbarick and Khosla2015). It primarily degrades through microbial activity, and degradation rates are affected by temperature and moisture, with warmer and wetter soils promoting faster degradation (Long et al. Reference Long, Li and Wu2014).

Fomesafen (WSSA Group 14) inhibits protoporphyrinogen oxidase. The herbicide gained importance because of its control of glyphosate-resistant broadleaf species (Knezevic et al. Reference Knezevic, Darta, Scott, Klein and Golus2009; Werle et al. Reference Werle, Mobli, DeWerff and Arneson2023). Its half-life ranges from 23 to 73 d under field conditions, although half-lives of up to 12 mo have been reported depending on weather and soil characteristics (Mueller et al. Reference Mueller, Boswell, Mueller and Steckel2014; Rauch et al. Reference Rauch, Bellinder, Brainard, Lane and Thies2007; Shaner Reference Shaner2014). Microbial degradation plays an important role in fomesafen degradation (Feng et al. Reference Feng, Li, Zhang, Zhang, Huang, Lu and Li2012), and higher mobility in the soil occurs when sand content is greater (Weber Reference Weber1993).

Although imazethapyr and fomesafen provide postemergence weed control, all three herbicides in this study offer residual weed control. S-metolachlor, imazethapyr, and fomesafen are all labeled for postemergence application to soybean, providing flexibility in application time that allows growers to adapt their herbicide programs based on field conditions and weed emergence patterns (BASF 2017; Syngenta 2019).

The length of the growing season in the northern U.S. Corn Belt has increased by 5 to 20 d over the past 50 yr (Kucharik et al. Reference Kucharik, Serbin, Vavrus, Hopkins and Motew2010). Before studies identified this shift in weather patterns, researchers had already recognized the importance of planting date for soybean production. Cartter and Hartwig (Reference Cartter and Hartwig1962) identified planting date as the most critical cultural factor influencing soybean production. Egli and Cornelius (Reference Egli and Cornelius2009) reported that after May 30, each day of planting delay resulted in a 0.7% decline in soybean yield in the Midwest. More recently, Malcomson et al. (Reference Malcomson, Mourtzinis, Gaska, Roth, Silva and Conley2024) found that optimal soybean yield in Wisconsin was achieved when planting occurred before May 20, with a consistent decline in yield with later planting dates. As planting dates continue to be pushed earlier, determining the optimal time for residual herbicide application is necessary for effective weed control. For complete control of summer annual species, delayed applications may be the most effective strategy for early planted soybean, particularly in areas where late-emerging weeds are prevalent, provided timely rainfall occurs for herbicide activation (Vollmer et al. Reference Vollmer, VanGessel, Johnson and Scott2019; Werle et al. Reference Werle, Sandell, Buhler, Hartzler and Lindquist2014).

With the trend in earlier soybean planting in the northern U.S. Corn Belt, a growing need exists for information on how this shift influences soil residual herbicide persistence, herbicide efficacy, and soybean yield to support weed management practices that are undergoing this major change in planting time. Thus, the objective of this study was to evaluate the fate and efficacy of S-metolachlor, imazethapyr, and fomesafen applied at different times to early planted soybean under no-till and tillage conditions, across two contrasting soils in southern Wisconsin. Herbicide concentration data collected for this study were compared across application times and treatments to determine the herbicide persistence in the soil.

Materials and Methods

Field Characteristics and Procedures

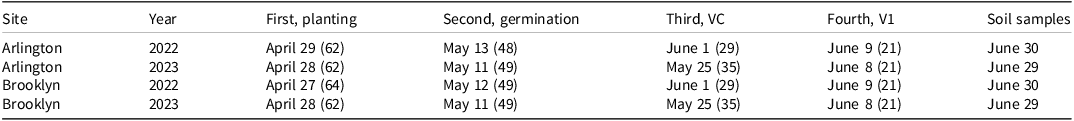

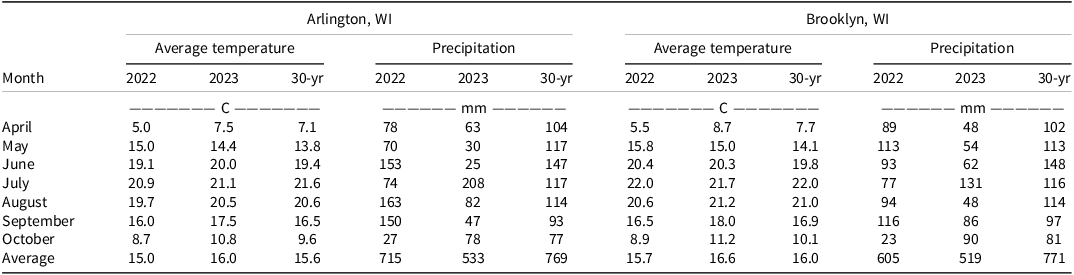

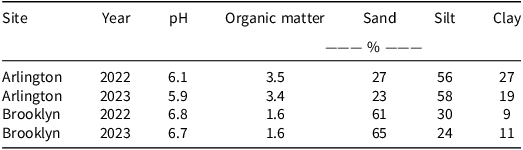

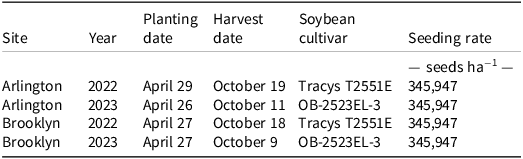

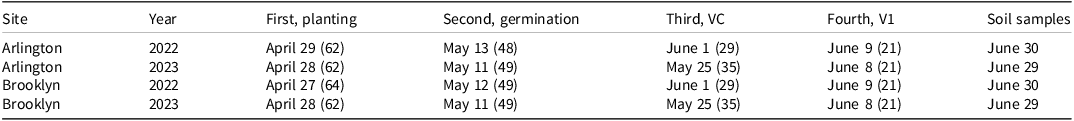

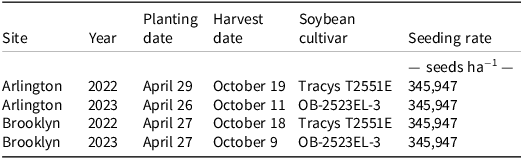

The soybean field experiments were established in 2022 and 2023 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Arlington Agricultural Research Station near Arlington, Wisconsin (43.309564°N, 89.345927°W), and at the O’Brien family farm near Brooklyn, Wisconsin (42.871172°N, 89.398500°W), in fields with a history of corn-soybean rotation, where corn was planted the year prior to the study. The two sites differed in soil characteristics, with Arlington having a silt loam soil and Brooklyn a sandy loam soil (Table 1), which could influence herbicide behavior. Plot dimensions were 9.1 m long by 3 m wide, consisting of four rows of soybean (row spacing of 76 cm). Soybean cultivars, seeding rates, and timing of field operations are shown in Table 2. The experimental design was a two-factor, randomized complete block design with four replications. Factor A consisted of two soil management treatments: chisel-plow in the fall followed by field cultivator within a week of planting (hereafter referred to as tillage), and no-till. Factor B consisted of four herbicide application times, at planting, 14, 28, and 42 d after planting, and the nontreated control. Time of herbicide applications and crop stage at each application time are shown in Table 3.

Table 1. Soil information.

Table 2. Soybean cultivar, seeding rates, and timing of soybean field.

Herbicide Applications

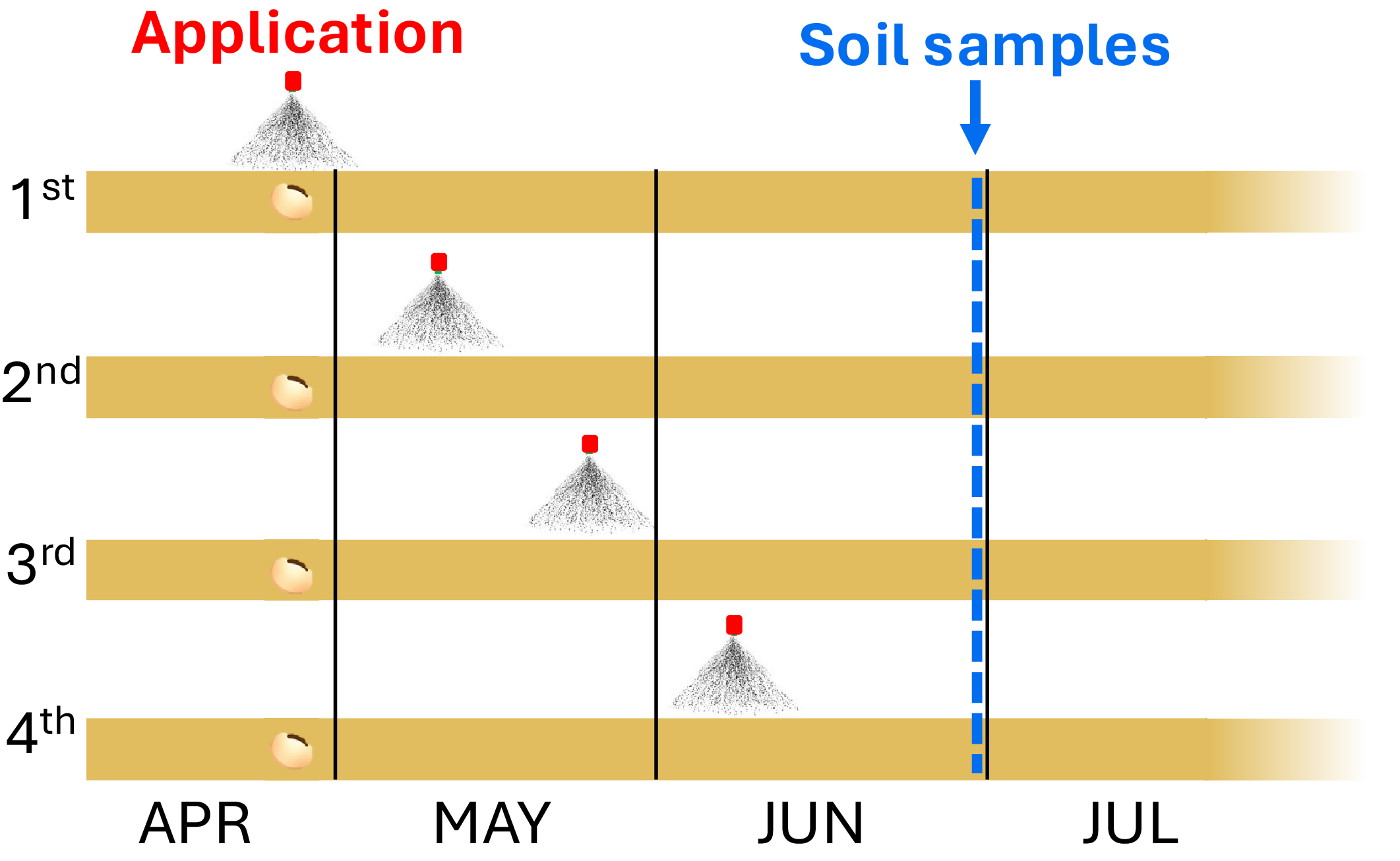

Herbicide treatments consisted of imazethapyr (70 g ai ha−1, Pursuit; BASF, Research Triangle Park, NC), a commercial premix (Prefix; Syngenta Crop Protection, Greensboro, NC) of S-metolachlor (1,216 g ai ha−1) and fomesafen (266 g ai ha−1). These herbicides were selected because they are commonly used in U.S. soybean production (Cornelius and Bradley Reference Cornelius and Bradley2017), represent multiple sites of action, and offer flexibility in application timing (preemergence and postemergence). S-metolachlor, fomesafen, and imazethapyr were selected for their soil residual activity, which was the focus of the persistence and efficacy evaluation in this study. Glufosinate (657 g ha−1, Liberty; BASF), a nonresidual postemergence herbicide (BASF 2022), and ammonium sulfate (AMS) at 1,400 g ha−1, were included in all treatments to ensure control of already emerged weeds at each application timing. Herbicide application dates for each application treatment time are shown in Table 3, and illustration for clarity is shown in Figure 1. The first through fourth applications coincided with planting, germination, VC–V1, and V1–V2 soybean growth stages, respectively.

Figure 1. Timeline of herbicide application times and soil sampling. All soybean were planted at the same time immediately before the first application. Red nozzle icons represent the four sequential herbicide applications. The blue arrow and dashed line indicate the soil sampling date, which occurred 21 d after the fourth application.

Glyphosate (1,345 g ae ha−1, Roundup PowerMAX; Bayer Crop Science, St. Louis, MO) plus AMS were applied to all no-till treatments at planting time to control emerged weeds with the aim of creating the same weed-free conditions for all treatments at crop establishment. Postemergence application took place when ∼20% of weeds within each treatment reached 10 cm in height or soybean reached the R1 growth stage, whichever happened first, and consisted of glyphosate (1,345 g ae ha−1) plus 2,4-D (1,065 g ae ha−1, Enlist One; Corteva Agriscience, Indianapolis, IN), plus acetochlor (1,261 g ai ha−1, Warrant; Bayer Crop Science) plus AMS. If weeds emerged after postemergence and before soybean reached the R1 growth stage, a late postemergence application consisting of glyphosate (1,345 g ae ha−1) plus glufosinate (657 g ha−1) plus AMS was deployed. Herbicides were applied using a CO2-pressurized backpack sprayer with six nozzles spaced 50.8 cm apart at a boom height of 50 cm from the soil surface. For preemergence and postemergence applications, TeeJet TTI110015 and TeeJet AIXR110015 nozzles were used, respectively (TeeJet, Glendale Heights, IL). The sprayers were calibrated to deliver 140 L ha−1.

Soil Sampling

Soil samples were collected 21 d after the fourth and last herbicide application treatment time to quantify concentrations of fomesafen, imazethapyr, and S-metolachlor in the soil, which served as indicators of herbicide dissipation in this study (Figure 1). Because treatments were applied sequentially, the interval between each herbicide application and the soil sampling date varied. Specifically, the number of days from application to soil sampling ranged from 21 d (from the fourth and last application time treatment) to 62 d (from the first application time treatment; Table 3). Soil sampling, processing, and analysis followed the procedures recommended by Mueller and Senseman (Reference Mueller and Senseman2015). Three soil subsamples (cores measuring 0 to 7.6 cm in depth and 10 cm in diameter) were collected from each plot using a golf cup cutter (Par Aide Products, St. Paul, MN). Subsamples were thoroughly homogenized in individual buckets, combined into one sample per plot, placed in plastic bags, sealed, and immediately stored in a cooler before being transferred to a freezer (−10 C).

Before extraction, soil samples were thawed at room temperature for 60 min and manually homogenized within their respective bags. A 15 ± 0.5 g portion of homogenized soil was placed in a 50-mL conical polypropylene tube (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), followed by the addition of 30 mL of methanol (RPI Research Products, Mount Prospect, IL). The tubes were sealed and subjected to horizontal reciprocating shaking for 14 h. After shaking, samples were allowed to equilibrate statically for 30 min to facilitate separation of the methanol solution from soil particles. A 10-mL syringe was used to extract 5 mL of the supernatant, and 2 mL were filtered through a 0.45-µm membrane (Fisher Scientific) into a liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry vial. Vials were stored in a freezer until overnight shipment on dry ice to the Department of Plant Sciences at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, for analysis.

To quantify herbicide concentrations, tubes containing the remaining soil and solution were dried at 65 C until a constant weight was achieved, allowing for dry soil weight determination. Samples were corrected for antecedent soil moisture and dilution during analysis. Herbicide quantification was conducted using an Agilent 1260 liquid chromatograph coupled with a 6470 mass spectrometry detector. A phenyl-hexyl analytical column (3.0 × 100 mm, 2.7 µm particle size; Agilent Technologies, Savage, MD) was used, preceded by a guard column of the same stationary phase (3.0 × 5 mm). All separations used a gradient mobile phase of acetonitrile and water, both fortified with 0.1% formic acid (mass spectrometry grade). The gradient started at 50% aqueous phase with linear gradient to 90% organic phase over 4 min, with appropriate equilibration times included between runs to ensure column stability. Parent and confirmatory ion masses for fomesafen were 437 and 286, for imazethapyr they were 290.2 and 245.1/177, and those for S-metolachlor were 284.1 and 252.1/176.1, respectively. The detection limit for both herbicides was 1.0 ng g−1 dry soil, with recovery rates exceeding 85% across all soil samples. Recovery corrections were not applied.

Data Collection

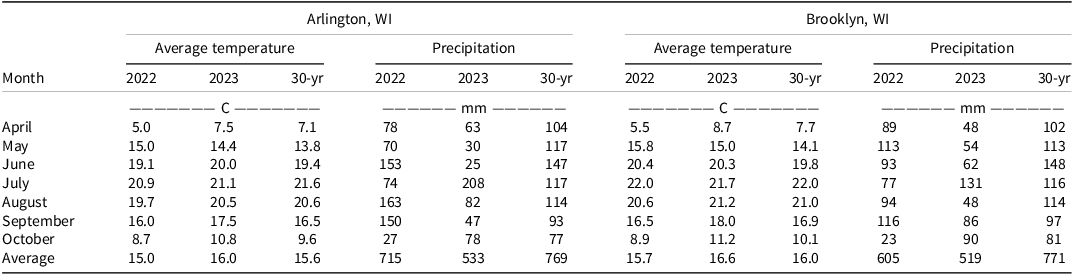

Weather data were collected with onsite Watchdog 2700 weather stations (Spectrum Technologies, Aurora, IL). The 30-yr average (1991 to 2020), and temperature and rainfall data, were obtained using Daymet weather data for 1-km grids (Thornton et al. 2024). Monthly temperature and precipitation for 2022, 2023, and 30-yr normal were summarized using R statistical software (v. 4.3.1; R Core Team 2024).

The weed species present in the field for this study included giant foxtail (Setaria faberi Herrm.), green foxtail [Setaria viridis (L.) P. Beauv.], common lambsquarters (Chenopodium album L.), common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.), and waterhemp [Amaranthus tuberculatus (Moq.) J.D. Sauer]. At Arlington, weed density composition at the time of postemergence herbicide application in the nontreated check consisted of foxtail species 76% to 82%, followed by 10% to 15% of common ragweed, and 7% to 8% of common lambsquarters. At Brooklyn, waterhemp was the only weed species present. These species represent some of the most common important weeds in Wisconsin and across the U.S. Midwest (Chudzik et al. Reference Chudzik, Nunes, Arneson, Arneson, Conley and Werle2024; Ugljic et al. Reference Ugljic, Mobli, Oliveira, Proctor, Dille and Werle2025).

When postemergence herbicides were applied, two 0.25-m2 quadrats (50 by 50 cm) were randomly placed in the center row of treated plots to determine weed plant density and the height of five randomly selected plants immediately before application. When soybean reached maturity, weeds were clipped at the soil level using two 0.25-m2 quadrats, and the fresh biomass was dried at 60 C until a constant weight was obtained. The center two soybean rows of each plot were harvested using an Almaco (Nevada, IA) plot combine. The combine was equipped with a Seed Spector LRX (Almaco) grain gauge. Soybean yield data were adjusted to 13% moisture.

Data Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software (v. 4.3.1). Before analyses, model assumptions were visually assessed for normal distribution and homogeneity of variance. A square root transformation was needed for herbicide concentration, weed density at postemergence, and soybean yield; back-transformed means are presented. Analysis of variance was conducted for each response variable to assess differences among treatments. Fixed effects included soil management, application time, site, and year, whereas replications were treated as a random effect. Means were separated using a Fisher protected LSD test with the emmeans package (P ≤ 0.05; Lenth Reference Lenth2024). Significant interactions were observed between treatments and years for all response variables (P < 0.05; data not shown). Therefore, each response variable was analyzed independently and is presented and discussed separately for each site-year.

Results and Discussion

Weather

The accumulated precipitation during the growing season (April–October) was below the 30-yr average for all site-years (Table 4). The 2023 growing season was characterized by drought conditions across the Midwest, with the first 3 mo (April–June) being particularly dry at both experimental locations.

Imazethapyr Fate in the Soil

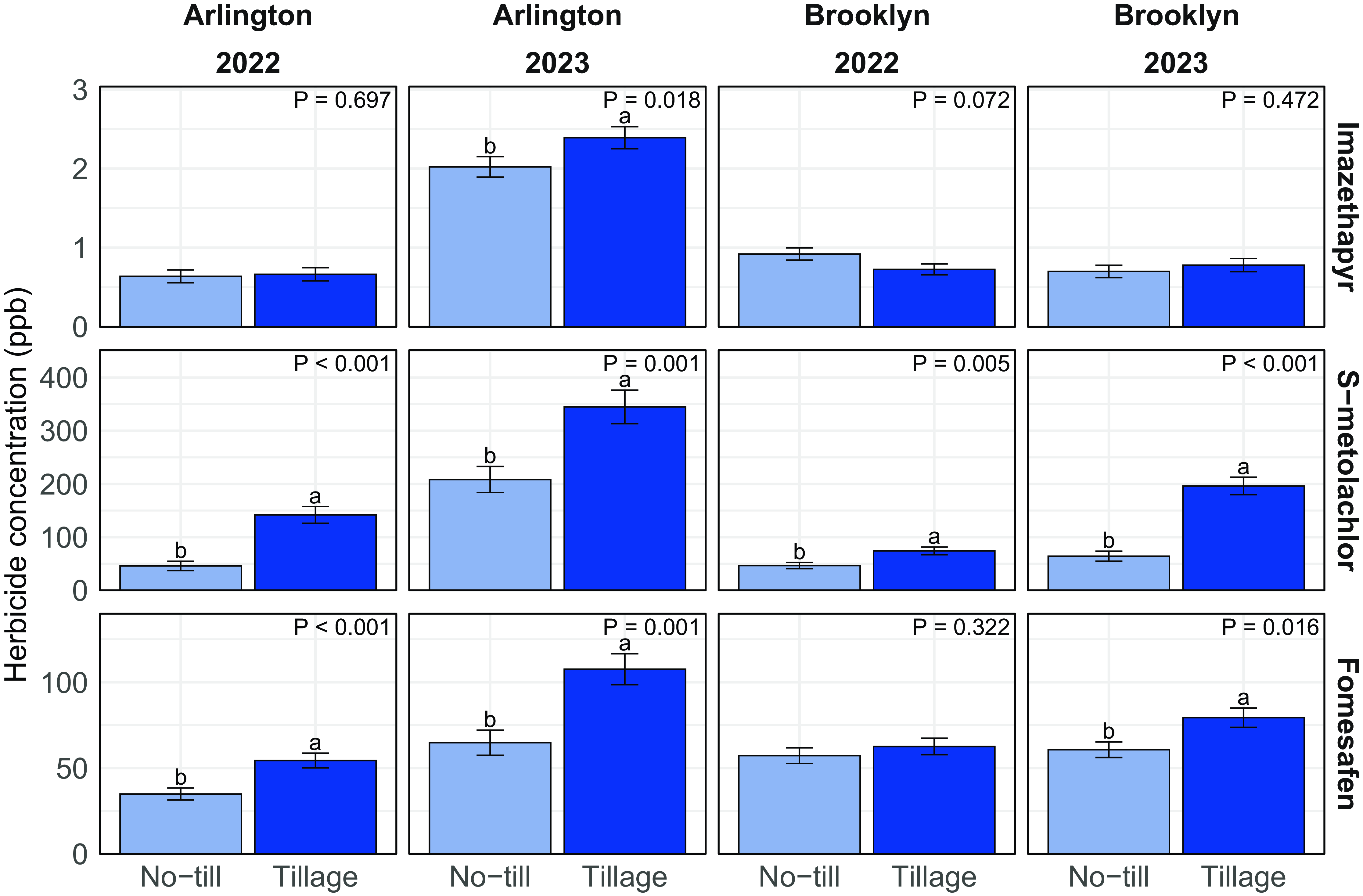

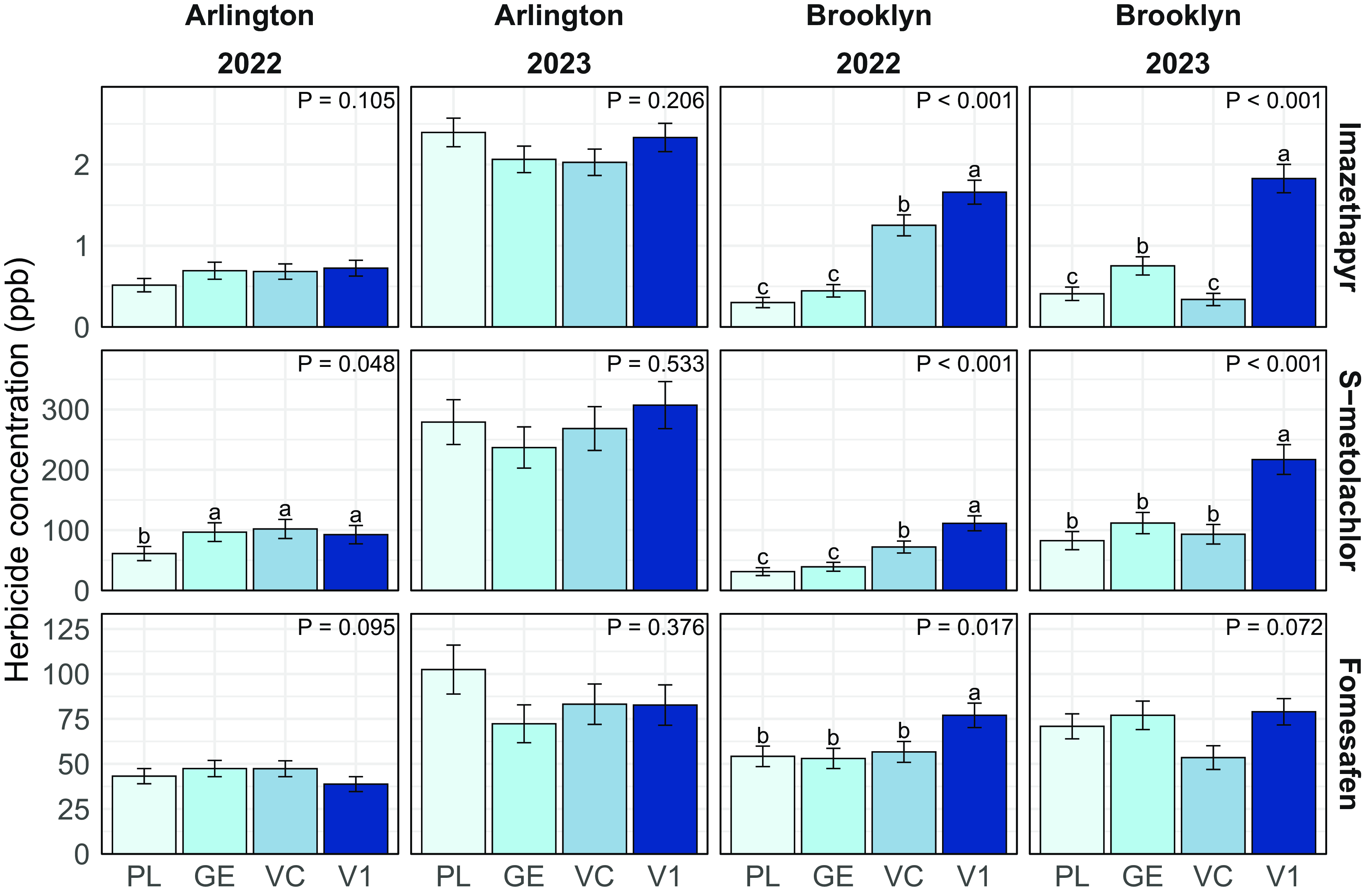

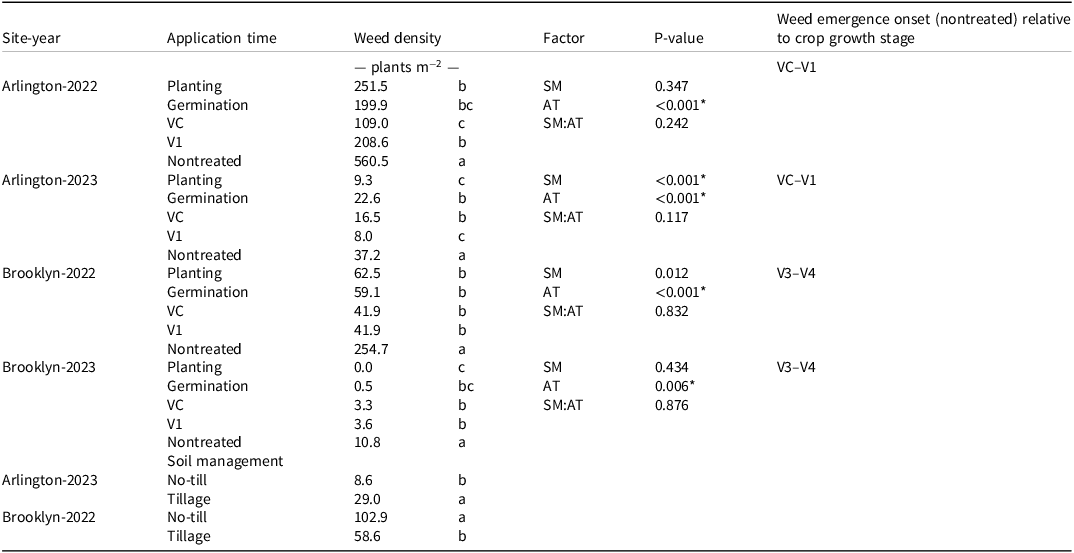

The application time × soil management interaction was not significant (P > 0.05; Table S3). Arlington-2023 was the only site-year to exhibit different imazethapyr concentrations between tillage and no-till. No-till exhibited 15% lower imazethapyr when compared to tillage (Figure 2). No differences in imazethapyr concentration were observed across different application times at the Arlington location in both years. At Brooklyn-2022, the first two application times averaged 69% and 77% lower imazethapyr concentration when compared with the third and fourth application times, respectively (Figure 3). At Brooklyn-2023, the imazethapyr concentration in the first three applications was at least 58% lower than the last application time. These results suggest that application time had a greater effect on imazethapyr persistence in sandy loam soil at Brooklyn, while no difference was observed in the silt loam soil at Arlington.

Figure 2. Soil concentration of imazethapyr, S-metolachlor, and fomesafen in the 0- to 7.6-cm depth at 21 d after the last application in 2022 and 2023 as affected by soil management. No significant application time × soil management interaction was detected. Bars represent mean values and error bars indicate standard error of the mean. Mean values followed by the same lowercase letter within a site-year for each herbicide are not significantly different according to the Fisher LSD test (α = 0.05). Corresponding means and standard errors are provided in Supplemental Table S3. Abbreviation: ppb, parts per billion.

Figure 3. Soil concentration of imazethapyr, S-metolachlor, and fomesafen in the 0- to 7.6-cm depth at 21 d after the last application in 2022 and 2023 as affected by application time. No significant application time × soil management interaction was detected. Bars represent mean values and error bars indicate standard error of the mean. Mean values followed by the same lowercase letter within a site-year for each herbicide are not significantly different according to the Fisher LSD test (α = 0.05). Corresponding means and standard errors are provided in Supplemental Table S3. Abbreviations: GE, germination; PL, planting; VC, soybean cotyledon stage; V1, soybean first trifoliolate stage.

Imazethapyr persistence is affected by soil temperature, soil characteristics, moisture content, and sorption (Cantwell et al. Reference Cantwell, Liebl and Slife1989; Loux et al. Reference Loux, Liebl and Slife1989). Cantwell et al. (Reference Cantwell, Liebl and Slife1989) demonstrated that microbial degradation of imazethapyr was substantially higher in soils with lower organic matter and clay content (e.g., Cisne silt loam) than in fine-textured soils like the Drummer silty clay loam. They attributed this difference to greater herbicide adsorption in the finer-textured soil, which reduced bioavailability and limited microbial degradation. Field studies suggest that imazethapyr movement in the soil profile is limited to the top 30 cm, despite its limited sorption to soil colloids (Jourdan et al. Reference Jourdan, Majek and Ayeni1998). These results demonstrate how application time can strongly influence imazethapyr persistence in coarse-textured soils, where herbicide dissipation can occur rapidly, while imazethapyr persistence may be prolonged in finer-textured soils, providing greater flexibility in application windows. Moreover, Cantwell et al. (Reference Cantwell, Liebl and Slife1989) noted that soil moisture is essential for imazethapyr to be bioavailable in solution for eventual microbial breakdown, and Loux and Reese (Reference Loux and Reese1993) reported greater imazethapyr persistence in dry years due to reduced soil moisture and slower dissipation.

Loux et al. (Reference Loux, Liebl and Slife1989) observed a biphasic degradation pattern, with most dissipation occurring within the first 60 d in the upper 7.6 cm of soil. However, our results suggest that substantial imazethapyr reduction occurred even within 29 to 35 d after application (Table 3; Figure 3), that is our third application time, in the sandy loam soils of Brooklyn. Stougaard et al. (Reference Stougaard, Shea and Martin1990) found that adsorption of imazethapyr increases at lower pH, which limits its availability. Similarly, Loux and Reese (Reference Loux and Reese1993) found that soil pH had a greater effect on imazethapyr persistence in low-clay soils, with persistence increasing as pH decreased from 6.7 to 4.6 in a medium-textured silt loam, but no clear pH effect in high-clay soil. This supports our findings at Brooklyn, where higher pH (approximately 6.7 to 6.8; Table 1) and low clay and organic matter, compared to the soil at Arlington, likely increased imazethapyr bioavailability thus accelerated dissipation.

Collectively, these results reinforce that soil pH, texture, and organic matter strongly influence imazethapyr fate, with faster dissipation in coarse-textured, higher pH, low organic matter soils like Brooklyn. While soil management showed limited influence, application time and soil characteristics had a stronger effect on imazethapyr persistence.

S-Metolachlor Fate in the Soil

The application time × soil management interaction was not significant (P > 0.05; Table S3). Across all 4 site-years tillage exhibited higher S-metolachlor concentrations compared to no-till systems (Figure 2), with an average of 52% higher concentration. At Arlington, application time was not different among the three latest application times in 2022, averaging 36% higher concentration than the first application time, while no difference among application time was observed in 2023 (Figure 3). At Brooklyn, the last application consistently had at least 35% and 57% higher concentrations in 2022 and 2023, respectively, relative to earlier applications.

Under no-till systems, the presence of crop residues can intercept spray droplets, limiting herbicide contact with the soil. Nunes et al. (Reference Nunes, Arneson, DeWerff, Ruark, Conley, Smith and Werle2023) found lower S-metolachlor concentrations in cover crop systems compared to tillage, with a negative correlation between residue biomass and soil herbicide levels. If intercepted, S-metolachlor is susceptible to volatilization and photodegradation, especially under dry, warm conditions. Bedos et al. (Reference Bedos, Alletto, Durand, Fanucci, Brut, Bourdat-Deschamps, Giuliano, Loubet, Ceschia and Benoit2017) found that higher S-metolachlor volatilization occurred in fields where crop residue was present, where the surface residue exposes the herbicide to higher volatilization losses. Photodegradation is also a contributor to S-metolachlor dissipation in the field, particularly during prolonged dry periods when the herbicide remains on the soil surface or crop residue; however, to a lesser extent than volatilization (Kochany and Maguire Reference Kochany and Maguire1994; Shaner Reference Shaner2014; Zemolin et al. Reference Zemolin, Avila, Cassol, Massey and Camargo2014).

Shaner et al. (Reference Shaner, Brunk, Belles, Westra and Nissen2006) confirmed that the dissipation of S-metolachlor is significantly influenced by soil characteristics, including organic matter and clay content. Similarly, Peter and Weber (Reference Peter and Weber1985) found that organic matter was the soil property with the highest correlation with metolachlor adsorption, while clay content also contributed, but to a lesser extent. Gannon et al. (Reference Gannon, Hixson, Weber, Shi, Yelverton and Rufty2013) found that S-metolachlor sorption increases with organic matter, which reduces leaching potential but may also reduce bioavailability for degradation. Kouame et al. (Reference Kouame, Savin, Willett, Bertucci, Butts, Grantz and Roma-Burgos2022) showed that dissipation was faster earlier in the season, likely due to higher microbial activity and favorable moisture conditions, while hot and dry conditions later in the season slowed degradation.

Higher herbicide concentrations under tillage were likely due to the absence of crop residue, allowing for more herbicide to reach the soil, while in no-till treatments, crop residue intercepted S-metolachor, and rainfall was required to wash the herbicide from the residue into the soil, and during this process, some herbicide may have been lost, resulting in lower concentrations detected in the soil. Application time had a stronger influence on the sandy loam soil at Brooklyn, where later applications consistently resulted in greater herbicide persistence, while with the silt loam soil at Arlington, lower concentrations were observed only more than 60 d after application (Table 3; Figure 3). At Brooklyn, five out of the six herbicide-by-year combinations (three herbicides over 2 yr) exhibited significant differences in herbicide concentration over different application times (Figures 2 and 3). In contrast, at Arlington, only one out of six herbicide-by-year combinations exhibited differences.

Fomesafen Fate in the Soil

The application time × soil management interaction was not significant (P > 0.05; Table S3). No-till treatments resulted in lower fomesafen concentrations in the soil compared to tillage, with reductions of 35%, 39%, and 23% at Arlington in 2022 and 2023, and Brooklyn in 2023, respectively (Figure 2). Brooklyn in 2022 was the only site-year with no difference between soil management but different fomesafen concentrations between application times, with the latest application retaining on average 30% more than the remaining application times, the remaining site-years exhibited no difference in concentration among application times.

Li et al. (Reference Li, Grey, Price, Vencill and Webster2019) also noted that fomesafen may have greater mobility and bioavailability in soils with high sand content, high pH, and low organic matter, conditions similar to those observed at the Brooklyn site. Mueller et al. (Reference Mueller, Boswell, Mueller and Steckel2014) found that greater rainfall accelerated fomesafen degradation, while dry periods delayed dissipation, and Feng et al. (Reference Feng, Li, Zhang, Zhang, Huang, Lu and Li2012) confirmed that microbial degradation is the primary breakdown pathway for fomesafen in soil. Together, these findings suggest that the higher pH and sandy texture at Brooklyn may have enhanced herbicide dissipation in 2022, while Arlington’s more acidic, finer-textured silt loam soils likely promoted greater herbicide retention.

Overall Herbicide Fate in the Soil

The species evaluated in this study predominantly germinate and emerge from the top 5 cm of soil (Kegode and Pearce Reference Kegode and Pearce1998; Leon and Owen Reference Leon and Owen2004; Mohler and Galford Reference Mohler and Galford1997). Since herbicide samples were collected from the top 0 to 7.6 cm, variations in herbicide concentration may occur due to factors such as chemical degradation, microbial degradation, and leaching to deeper soil layers (>7.6 cm). Therefore, we hypothesize that the herbicide concentrations observed in this study can serve as a reference for comparing different management strategies because they reflect the amount of herbicide present in the weed seed zone.

The presence of residue in no-till systems appeared to affect S-metolachlor and fomesafen concentrations more than imazethapyr, likely due to differences in their physicochemical properties. Both S-metolachlor and fomesafen have lower water solubility (488 and 50 mg/L, respectively) compared to imazethapyr (1,400 mg/L), which limits their movement into the soil when intercepted by residue (Shaner Reference Shaner2014). The organic carbon–water partition coefficient (Koc) is a measure of the tendency of a compound to partition into soil organic carbon from aqueous solution, and S-metolachlor has the highest Koc (269 mL g−1) compared to imazethapyr (52 mL g−1) and fomesafen (50 mL g−1), indicating a stronger affinity for binding to organic matter, and since crop residues are high in organic carbon, it is reasonable to extend these findings to suggest that S-metolachlor may bind significantly to corn residue as well, which likely contributes to its reduced availability under no-till conditions (Cooke et al. Reference Cooke, Shaw and Collins2004; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Tzilivakis, Warner and Green2016, Westra et al. Reference Westra, Shaner, Barbarick and Khosla2015). In contrast, the higher solubility and lower Koc of imazethapyr make it less likely to bind to crop residue and more mobile through it, potentially explaining the smaller differences observed between tillage systems for this herbicide.

Environmental factors such as rainfall directly and indirectly influence herbicide behavior after application. Rainfall can potentially move herbicides into and/or beyond the sampled 0- to 7.6-cm zone and indirectly affect dissipation by altering soil moisture which impacts microbial degradation (Mueller et al. Reference Mueller, Boswell, Mueller and Steckel2014). Even though delaying application times increased herbicides concentrations in our study, particularly at the Brooklyn location, the highest concentration differences were observed when comparing treatments with the fourth and last application time. Differences were smaller when comparing only the first three applications times. This observation highlights that sandy loam soils, such as those at Brooklyn, allow for faster dissipation shortly after herbicide application due to lower sorption. In contrast, silt loam soils, like those at Arlington, can be more forgiving, with slower and more gradual dissipation over time, likely due to stronger herbicide binding and reduced bioavailability for degradation.

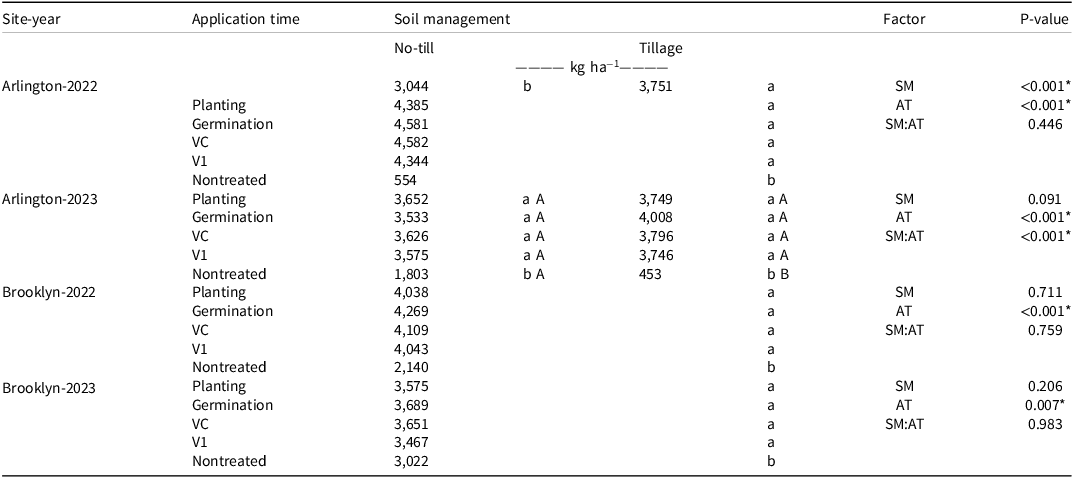

Weed Density at the Time of Postemergence

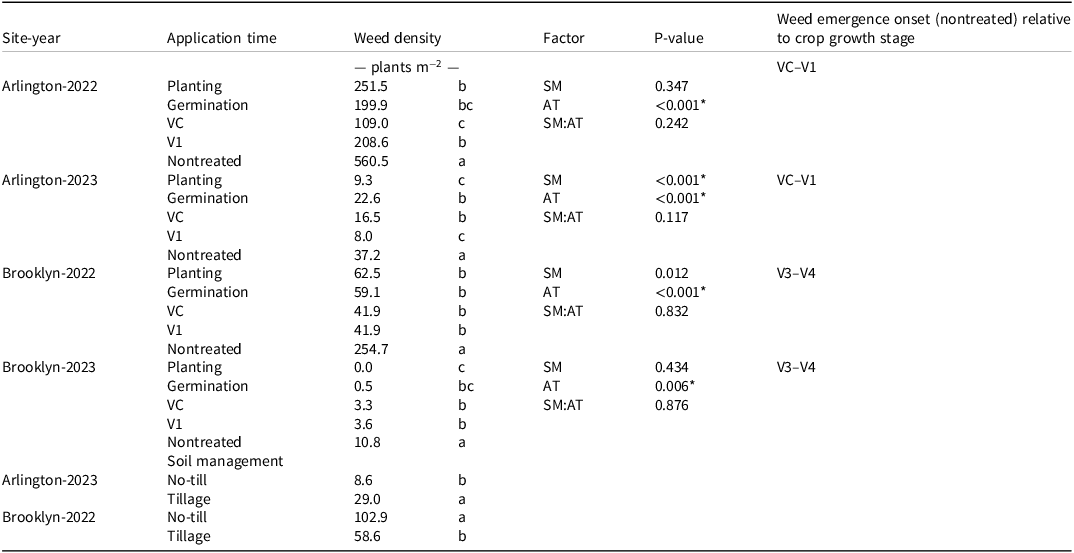

Across all site-years, the main effect of application time was significant, primarily driven by the consistently higher weed densities observed in the nontreated (no preemergence and no postemergence herbicide applications) control at the time of postemergence (Table 5). Plots that received a preemergence herbicide application had significantly lower weed densities, although differences among application timings were not consistent across years or locations. The overall trend confirms the expected benefit of preemergence herbicides in suppressing early season weed emergence. At the end of the season all treatments where a herbicide was applied showed >99% density reduction compared with nontreated control plots (data not shown).

a Abbreviations: AT, application time; SM, soil management; VC, cotyledon stage (soybean growth stage); V1, one open trifoliolate (soybean growth stage). P-values followed by an asterisk (*) indicate statistical significance at P ≤ 0.05.

b No Application time × soil management interaction was observed. P-values followed by an asterisk (*) indicate statistical significance at P ≤ 0.05.

c Mean values followed by the same lowercase letter within a site-year are not different according to the Fisher LSD test (α = 0.05).

d Treatment list and date of postemergence applications are provided in Supplemental Table S2.

At Brooklyn-2022, a significant main effect of soil management was observed; no-till plots had higher weed density than tilled plots. In contrast, at Arlington-2023, tilled plots had greater weed density than no-till plots. The higher waterhemp density observed in no-till plots at Brooklyn-2022 aligns with previous studies, which suggest that a greater number of seeds present in the upper soil layer in a no-till system lead to increased waterhemp emergence and density (Govindasamy et al. Reference Govindasamy, Sarangi, Provin, Hons and Bagavathiannan2021; Refsell and Hartzler Reference Refsell and Hartzler2009). Additionally, Farmer et al. (Reference Farmer, Bradley, Young, Steckel, Johnson, Norsworthy, Davis and Loux2017) reported that conventional tillage alone did not reduce Amaranthus spp. density in the absence of a soil residual herbicide, however, once a soil residual herbicide was applied, as in the present study, lower Amaranthus spp. density was observed under conventional tillage. For the species observed at the Arlington site, Mulugeta and Stoltenberg (Reference Mulugeta and Stoltenberg1997) found that soil disturbance increased seedling emergence by placing seeds near the surface, where greater moisture fluctuation occurred. In contrast, Buhler and Mester (Reference Buhler and Mester1991) observed higher weed density under no-till compared to conventional tillage systems. Buhler et al. (Reference Buhler, Mester and Kohler1996) further suggested that surface residues in no-till systems can reduce soil temperatures and delay seedling emergence. Moreover, the influence of tillage on weed emergence is largely driven by environmental conditions and by its interaction with surface residues and seed distribution in the soil (Buhler et al. Reference Buhler, Mester and Kohler1996, Roman et al Reference Roman, Murphy and Swanton1999). At Arlington-2023, a high amount of corn residue was present on the soil surface. Additionally, the fields were under a long-term corn-soybean rotation, and tillage may have brought previously buried weed seeds to the soil surface, potentially favoring their germination and establishment.

A late postemergence application was needed only for the first two application times at both no-till and tillage soil managements at Brooklyn-2022, likely due to lower residual herbicide concentration in the soil given that these two times had residual herbicide application sprayed 4 wk before the onset of waterhemp emergence in the study (Chudzik, personal observation). Emphasizing the need to synchronize residual herbicide applications with the expected time of weed emergence, particularly for late-emerging species such as waterhemp (Striegel et al. Reference Striegel, Oliveira, DeWerff, Stoltenberg, Conley and Werle2021; Vollmer et al. Reference Vollmer, VanGessel, Johnson and Scott2019), and especially in soils that allow for faster herbicide dissipation, such as the sandy loam soil observed in this study.

This study was conducted using a two-pass herbicide program, which has been shown to have more consistent weed control than a single-pass program in the U.S. Midwest (Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Liu, Peterson and Stahlman2021; Mobli et al. Reference Mobli, DeWerff, Arneson and Werle2023; Striegel et al. Reference Striegel, Oliveira, DeWerff, Stoltenberg, Conley and Werle2021). However, a third postemergence application was required for the first two application times at Brooklyn in 2022 due to early dissipation of the residual herbicide. Despite this, all treatments that received a herbicide application exhibited reduced weed density at the time of postemergence herbicide application compared to the nontreated check. Since resistance development is proportional to the size of the weed population exposed to selection, minimizing escapes is essential to delay resistance evolution. Efforts to minimize the number of plants exposed to postemergence herbicides are a key component of herbicide stewardship programs to preserve the effectiveness of the currently limited effective postemergence options (Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Ward, Shaw, Llewellyn, Nichols, Webster, Bradley, Frisvold, Powles and Burgos2012).

Soybean Yield

No soybean yield differences were observed among herbicide treatments across all site-years. However, the nontreated control consistently produced reduced yield compared with the herbicide treatments (Table 6). At Arlington-2022, a main effect of soil management was significant, and no-till plots yielded 18% less than tilled plots, and the nontreated (no preemergence and no postemergence) control had an 87% yield reduction compared with treated plots. In 2023, a significant soil management × application time interaction was observed, with the nontreated control having 51% yield reduction in no-till and 88% in tilled plots compared with plots that received preemergence and postemergence applications, likely due to three times higher weed density in tilled plots (Table 5). Yield losses due to high interference from giant foxtail and common lambsquarters have been reported to reduce soybean yield by up to 86%, depending on weed density and environment (Conley et al. Reference Conley, Stoltenberg, Boerboom and Binning2003), while common ragweed has been shown to cause yield losses exceeding 80% (Barnes et al. Reference Barnes, Jhala, Knezevic, Sikkema and Lindquist2018).

a Abbreviations: AT, application time; SM, soil management.

b Mean values followed by the same lowercase letter within a site-year are not different according to the Fisher LSD test (α = 0.05). Mean values followed by the same uppercase letter within an application time are not different according to the Fisher LSD test (α = 0.05).

At Brooklyn, results were similar across years, with consistent yield across all treated plots regardless of herbicide application time, and yield reductions of 47% in 2022 and 16% in 2023 for nontreated controls. This difference can be attributed to lower weed density in 2023 (10.8 waterhemp plants m−2) due to drier conditions, compared with 254 plants m−2 in 2022. Soltani et al. (Reference Soltani, Shropshire and Sikkema2022) found that soybean yield reduction was highly influenced by weed density, with higher weed densities causing weed reductions shortly after soybean emergence, while lower densities delayed yield losses until approximately the V4 growth stage. These findings highlight the importance of timely herbicide applications in preventing weed competition and maintaining soybean yield, regardless of soil management.

It is worth noting that the herbicide program consisted of a two-pass system for most treatments across site-years, which consistently maintained yield across plots sprayed at different times. The two earliest application times at Brooklyn-2022 required a total of three herbicide applications to achieve complete season-long weed control, resulting in similar yields compared to the other treatments. This highlights the potential need of additional inputs when residual herbicides are applied very early, potentially not synchronized with weed emergence patterns, particularly in lighter soils.

Practical Implications

Differences in herbicide concentration at a common sampling point indicate that herbicide dissipation was slower in the silt loam soil, while the sandy loam soil exhibited more rapid dissipation across application times. These differences suggest that in coarse-textured soils, earlier applications may have less effective soil residual activity due to shorter herbicide persistence, increasing the risk of weed escapes if residuals are not well timed with emergence time of target weed species. In contrast, finer-textured soils may offer more flexibility in application timing, because slower dissipation helps maintain effective herbicide concentrations for a longer period, which may help applicators spread their workload and choose application times under more favorable weather conditions. Understanding the ecology and emergence patterns of the weed community at the field scale will support more informed decision-making, particularly in coarse-textured soils where residual activity may be shorter. While herbicide combinations can improve control under variable conditions (Landau et al. Reference Landau, Hager, Tranel, Davis, Martin and Williams2021; Silva et al. Reference Silva, Arneson, DeWerff, Smith, Silva and Werle2023), further research is needed to understand the individual contributions of active ingredients under different soil types and weed emergence scenarios, a deeper understanding that could also help predict and mitigate potential carryover effects. Ultimately, this knowledge will support the development of more reliable herbicide combinations optimized for different soil types and environmental conditions.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/wet.2025.10076

Acknowledgments

We thank Arthur Franco Teodoro Duarte, Felipe Faleco, Jacob Felsman, Jose Jr Nunes, Laura Rodriguez Baquero, Meghan Baker, Nikola Arsenijevic, Shelby Lanz, Tatiane Severo Silva, and Zaim Ugljic, for their valuable contributions across all phases of this project from planting to harvest, sample processing, and data interpretation.

Funding

This project was partially funded by the United Soybean Marketing Board.

Competing Interests

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.