Introduction

Weed resistance to herbicides poses a substantial threat to agricultural productivity by limiting the number of herbicides available for effective weed control (Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Ward, Shaw, Llewellyn, Nichols, Webster, Bradley, Frisvold, Powles, Burgos and Witt2012). Without effective management strategies, herbicide-resistant weeds can spread in fields, resulting in diminished yields and compromised agricultural sustainability. Among the major crops produced worldwide, rice ranks third in having the greatest number of weeds that have evolved resistance to herbicides, with 57 species documented globally, trailing only wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and corn (Zea mays L.) (Heap Reference Heap2025).

One weed that is troublesome in furrow-irrigated rice in Arkansas is Palmer amaranth (Butts et al. Reference Butts, Kouame, Norsworthy and Barber2022). Palmer amaranth is a dioecious summer annual weed (Sauer Reference Sauer1957; Steckel Reference Steckel2007) that has evolved resistance to herbicides that target nine sites of action (SOAs) (Carvalho-Moore Reference Carvalho-Moore, Norsworthy, Souza, Barber, Piveta and Meiners2025; Heap Reference Heap2025). This extensive resistance profile is partially attributed to its reproductive biology, which relies on outcrossing that promotes high genetic diversity (Ward et al. Reference Ward, Webster and Steckel2013). Moreover, Palmer amaranth is pollinated via wind, and its pollen can travel extended distances. Consequently, herbicide resistance can spread extensively within fields (Chandi et al. Reference Chandi, Milla-Lewis, Jordan, York, Burton, Zuleta, Whitaker and Culpepper2013; Sosnoskie et al. Reference Sosnoskie, Webster, Kichler, MacRae, Grey and Culpepper2012).

Palmer amaranth can impact crop yields depending on when it emerges and its density. In corn, at 8 plants m−1 of row, Palmer amaranth caused 91% yield loss compared to weed-free plots (Massinga et al. Reference Massinga, Currie, Horak and Boyer2001). Similarly, cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) lint yield was reduced by 57% and 60% at 1.1 and 1.6 plants m−1 of row, respectively, when compared with a weed-free treatment (MacRae et al. Reference MacRae, Webster, Sosnoskie, Culpepper and Kichler2013; Morgan et al. Reference Morgan, Baumann and Chandler2001). Palmer amaranth plants that emerged 1 wk before rice led to a 50% yield loss within 0.4 m of the weed in a furrow-irrigated system (King et al. Reference King, Norsworthy, Butts, Fernandes, Drescher and Avent2024a).

In Arkansas, rice cultivation predominantly entails dry-seeding followed by establishing a continuous flood at the 4- to 6-leaf growth stage (Hardke Reference Hardke2023; Henry et al. Reference Henry, Daniels, Hamilton, Hardke and Hardke2021). The continuous flood conditions suppress a broad spectrum of terrestrial weeds that require aerobic conditions to germinate and grow (Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Scott, Bangarwa, Griffith, Wilson and McCelland2011). Typically, Palmer amaranth poses a problem only before a field is flooded or on nearby levees (Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Bangarwa, Scott, Still and Griffith2010; Reference Norsworthy, Bond and Scott2013). However, the increased adoption of furrow-irrigated rice in Arkansas has altered this dynamic. Furrow-irrigated rice is characterized by three distinct soil moisture zones (upper aerobic, mid-field, and lower flooded). The absence of a continuous flood in the upper and middle portions of the field, combined with limited chemical options, makes Palmer amaranth management difficult (Bagavathiannan et al. Reference Bagavathiannan, Norsworthy and Scott2011; Hardke Reference Hardke2021, Reference Hardke2023; Massey et al. Reference Massey, Reba, Adviento-Borbe, Chiu and Payne2022).

Successful control of Palmer amaranth requires multiple residual and postemergence herbicide applications (Beesinger et al. Reference Beesinger, Norsworthy, Butts and Roberts2022a; Hill et al. Reference Hill, Norsworthy, Barber and Gbur2016; King et al. Reference King, Norsworthy, Butts, Barber, Drescher and Godar2024b). Using effective residual herbicides reduces reliance on postemergence applications and, therefore, decreases the risk of resistance evolution (Neve et al. Reference Neve, Norsworthy, Smith and Zelaya2011a, Reference Neve, Norsworthy, Smith and Zelaya2011b). Pendimethalin and saflufenacil are two residual herbicides used for controlling Palmer amaranth in rice (Barber et al. Reference Barber, Scott, Wright-Smith, Jones, Norsworthy, Burgos and Bertucci2025). However, resistance of Palmer amaranth to the SOAs of these herbicides has been documented (Heap Reference Heap2025). Thus, new residual chemical options are needed with the rise in Palmer amaranth occurrence in rice fields and its increasing resistance to herbicides.

The Herbicide Resistance Action Committee (HRAC) and Weed Science Society of America (WSSA) classify fluridone as a Group 12 herbicide. When used in cotton production, fluridone is applied preemergence and effectively controls Palmer amaranth (Grichar et al. Reference Grichar, Dotray and McGinty2020; Hill et al. Reference Hill, Norsworthy, Barber and Gbur2016). Fluridone was also recently registered for use on rice as an alternative option for Palmer amaranth control, offering a new SOA (Anonymous 2023a). Fluridone inhibits the phytoene desaturase enzyme, a component of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway (Bartels and Watson Reference Bartels and Watson1978; Sandmann and Böger Reference Sandmann, Böger, Roe, Burton and Kuhr1997; Sandmann et al. Reference Sandmann, Schmidt, Linden and Böger1991). Inhibition of this enzyme interrupts carotenoid synthesis, leading to the depletion of colored plastidic pigments, resulting in bleaching and death in susceptible plants (Chammovitz et al. Reference Chamovitz, Pecker and Hirschberg1991; Sandmann et al. Reference Sandmann, Schmidt, Linden and Böger1991).

The effectiveness of fluridone is influenced by soil moisture, with higher soil moisture increasing both weed control efficacy and the potential for crop injury (Butts et al. Reference Butts, Souza, Norsworthy, Barber and Hardke2024; Hill et al. Reference Hill, Norsworthy, Barber and Gbur2016; Martin et al. Reference Martin, Norsworthy, Scott, Hardke and Lorenz2018; Souza et al. Reference Souza, Norsworthy, Carvalho-Moore, Godar, Fernandes and Butts2025a). Souza et al. (Reference Souza, Norsworthy, Carvalho-Moore, Godar, Fernandes and Butts2025a) reported that injury from fluridone applied to 3-leaf rice at 168 and 336 g ai ha−1 increased from ≤6% 2 wk after treatment (WAT) to more than 25% 4 WAT in two rice cultivars following irrigation. Similarly, when applied to the same rice growth stage at 170 g ai ha−1 grown in a precision-leveled Sharkey-Steele clay soil, fluridone caused approximately 30% visual injury 8 WAT; however, the injury did not translate to grain yield loss (Butts et al. Reference Butts, Souza, Norsworthy, Barber and Hardke2024).

Given the need for better management strategies for Palmer amaranth control in rice, fluridone emerges as an effective option for controlling this weed. However, fluridone applications are restricted to rice at the 3-leaf growth stage or later due to potential crop injury with applications closer to planting (Souza et al. Reference Souza, Norsworthy, Carvalho-Moore, Godar, Fernandes and Butts2025a, Reference Souza, Norsworthy, Butts and Scott2025b). This restriction complicates Palmer amaranth management because weeds emerging before this stage would not be effectively controlled because fluridone lacks effective postemergence activity (Anonymous 2023a; Waldrep and Taylor Reference Waldrep and Taylor1976). Further research is needed to assess rice response to preemergence fluridone applications to determine whether the herbicide is suitable for being applied earlier in the season. Therefore, this study evaluated rice tolerance in a furrow-irrigated system, and the length of Palmer amaranth control offered by a range of fluridone rates applied preemergence at planting and when followed by a postemergence application of florpyrauxifen-benzyl, a herbicide that effectively controls the emerged weed (Beesinger et al. Reference Beesinger, Norsworthy, Butts and Roberts2022a; Miller and Norsworthy Reference Miller and Norsworthy2018; Wright et al. Reference Wright, Norsworthy, Roberts, Scott, Hardke and Gbur2021).

Materials and Methods

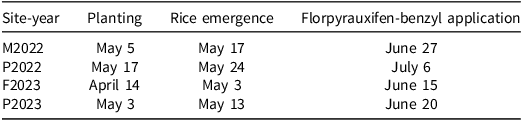

A field experiment was conducted in 2022 at the Lon Mann Cotton Research Station near Marianna, Arkansas (M2022) (34.732979°N, 90.766371°W), in 2022 and 2023 at the Pine Tree Research Station near Colt, Arkansas (P2022 and P2023, respectively; 35.123299°N, 90.930369°W), and at the Milo J. Shult Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Fayetteville, Arkansas (36.099631°N, 94.179310°W) in 2023 (F2023). The soil near Marianna is a Convent silt loam (9% sand, 80% silt, and 11% clay) with 1.8% organic matter, pH 6.5. The soil at the Colt site is a Calhoun silt loam (11% sand, 68% silt, and 21% clay) with 1.6% organic matter, pH 7.2. In Fayetteville, the soil is a Leaf silt loam (18% sand, 69% silt, and 13% clay) with 1.6% organic matter, pH 6.7. Fields were tilled in the spring before raised beds were formed at all locations, and the study was conducted in the higher, drier zone of the field. Glyphosate (1,262 g ae ha−1, Roundup PowerMAX3; Bayer CropScience, St. Louis, MO) was applied in all locations prior to planting. The rice hybrid RT 7321 FP (RiceTec, Alvin, TX) was drill-seeded into raised beds and furrows at all sites at 36 seeds m−1 of row at a depth of 1.3 cm using a nine-row, small-plot drill with 19 cm between rows. Planting and emergence dates are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Planting, rice emergence, and florpyrauxifen-benzyl application dates. a

a Abbreviations: M2022, Lon Mann Cotton Research Station near Marianna, Arkansas, 2022; P2022, Pine Tree Research Station near Colt, Arkansas, 2022; F2023, Milo J. Shult Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Fayetteville, Arkansas, 2023; P2023, Pine Tree Research Station near Colt, Arkansas, 2023.

The experimental design was a randomized complete block with a split-plot arrangement and four replications. A split-plot structure was implemented to minimize the risk of contamination from postemergence herbicide applications in adjacent plots. The whole-plot factor was the postemergence treatment, and the subplot factor was the fluridone (Brake; SePRO Corporation, Carmel, IN) rate. The postemergence treatments included 1) no herbicide applied postemergence (labeled as “None” in Tables 2–5), 2) a single application of florpyrauxifen-benzyl (15 g ai ha−1, Loyant; Corteva Agriscience, Indianapolis, IN with methylated seed oil, 0.6 L ha−1, MES-100; Drexel Chemical Company, Memphis, TN) at approximately 6 wk after rice emergence), and 3) plots maintained weed-free using herbicides commonly applied to rice and hand-weeded as needed. All fluridone treatments were applied preemergence on the day of planting. Florpyrauxifen-benzyl application dates are displayed in Table 1. Palmer amaranth average size at the time of florpyrauxifen-benzyl application was 20 cm at all locations. Fluridone rates were 0 (nontreated), 84 (0.5× label rate), 168 (1× label rate), and 336 (2× label rate) g ai ha−1. The subplots were 1.9 wide m by 5.2 m long (two beds) at the Marianna site, 3.1 m wide by 5.2 m long (four beds) at the Colt site, and 3.7 wide m by 5.2 m (four beds) at the Fayetteville site.

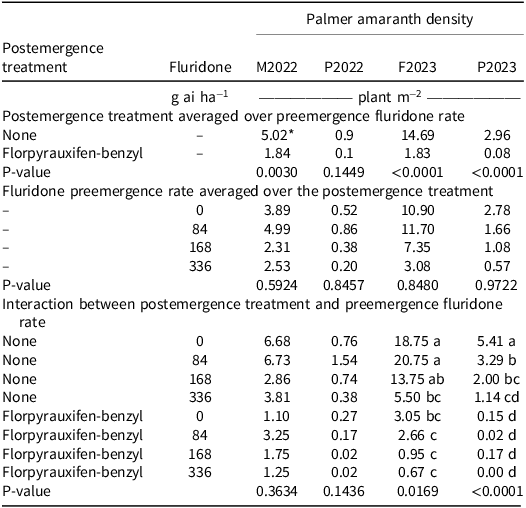

Table 2. Palmer amaranth density at harvest as influenced by postemergence treatment, preemergence applications of fluridone, and their interaction.a–f

a Abbreviations: M2022, Lon Mann Cotton Research Station near Marianna, Arkansas, 2022; P2022 and P2023, Pine Tree Research Station near Colt, Arkansas, 2022 and 2023, respectively; F2023, Milo J. Shult Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Fayetteville, Arkansas, 2023.

b Florpyrauxifen-benzyl (15 g ai ha−1) was applied approximately 6 wk after rice emergence.

c Male/female ratios were 1.11, 1.47, 1.17, and 0.83 for M2022, P2022, F2023, and P2023, respectively.

d Means within the same column are not different according to Tukey’s HSD (α = 0.05).

e Asterisks (*) indicate statistical significance (α = 0.05) between postemergence treatments averaged over fluridone rates for each site-year when interaction is not present.

f Dashes (–) represent treatments that were averaged over either the postemergence treatment or the fluridone rate, and therefore, no specific treatment applies.

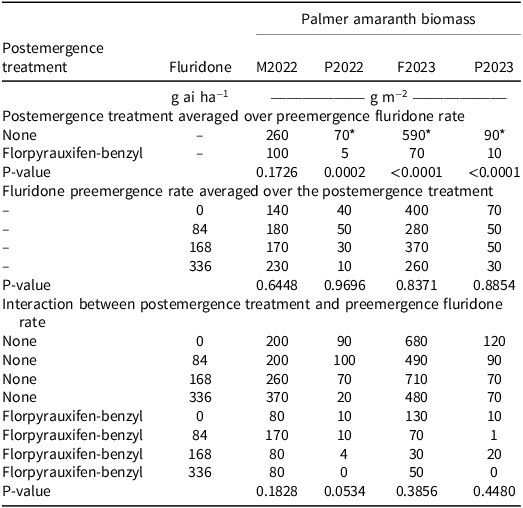

Table 3. Palmer amaranth biomass at harvest as influenced by postemergence treatment, preemergence applications of fluridone, and their interaction.a–c

a Abbreviations: M2022, Lon Mann Cotton Research Station near Marianna, AR, 2022; P2022 and P2023, Pine Tree Research Station near Colt, AR, 2022 and 2023, respectively; F2023, Milo J. Shult Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Fayetteville, AR, 2023.

b Florpyrauxifen-benzyl was applied approximately 6 wk after rice emergence at 15 g ai ha−1.

c Asterisks (*) indicate statistical significance (α = 0.05) between postemergence treatments averaged over fluridone rates for each site-year when interaction is not present.

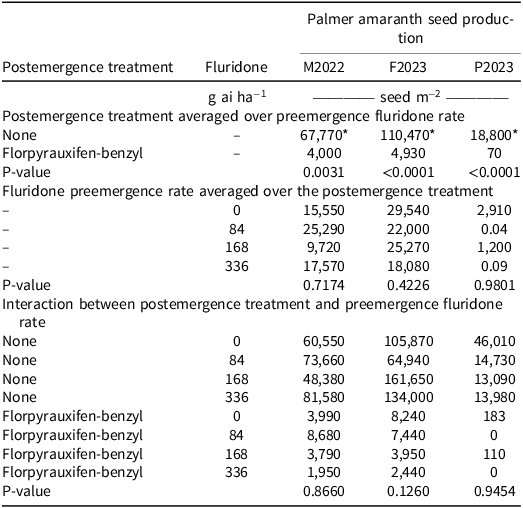

Table 4. Palmer amaranth seed production as influenced by postemergence treatment, preemergence applications of fluridone, and their interaction.a–d

a Abbreviations: M2022, Lon Mann Cotton Research Station near Marianna, AR, 2022; F2023, Milo J. Shult Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Fayetteville, AR, 2023; P2023, Pine Tree Research Station near Colt, AR, 2023.

b Florpyrauxifen-benzyl was applied approximately 6 wk after rice emergence at 15 g ai ha−1.

c Asterisks (*) indicate statistical significance (α = 0.05) between postemergence treatments averaged over fluridone rates for each site-year when interaction is not present.

d Seed production data are not presented for the Pine Tree Research Station site near Colt, Arkansas, 2022 (P2022) due to the lack of female plants across treatments.

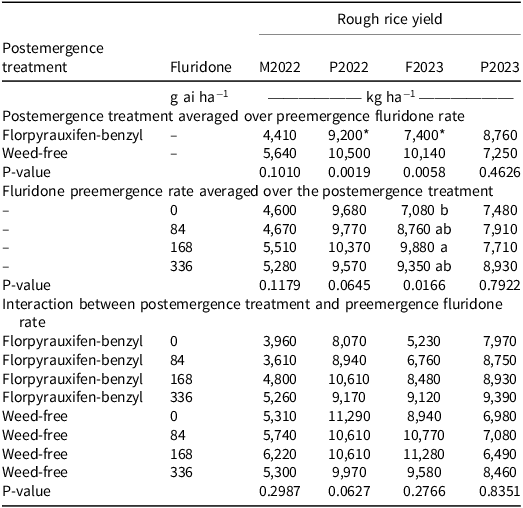

Table 5. Rough rice yield as influenced by postemergence treatment, preemergence applications of fluridone, and their interaction.a–d

a Abbreviations: M2022, Lon Mann Cotton Research Station near Marianna, Arkansas, 2022; P2022 and P0223, Pine Tree Research Station near Colt, Arkansas, 2022 and 2023, respectively; F2023, Milo J. Shult Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Fayetteville, Arkansas, 2023.

b Florpyrauxifen-benzyl was applied approximately 6 wk after rice emergence at 15 g ai ha−1.

c Means within the same column are not different according to Tukey’s HSD test (α = 0.05).

d Asterisks (*) indicate statistical significance (α = 0.05) between postemergence treatments averaged over fluridone rates for each site-year when interaction is not present.

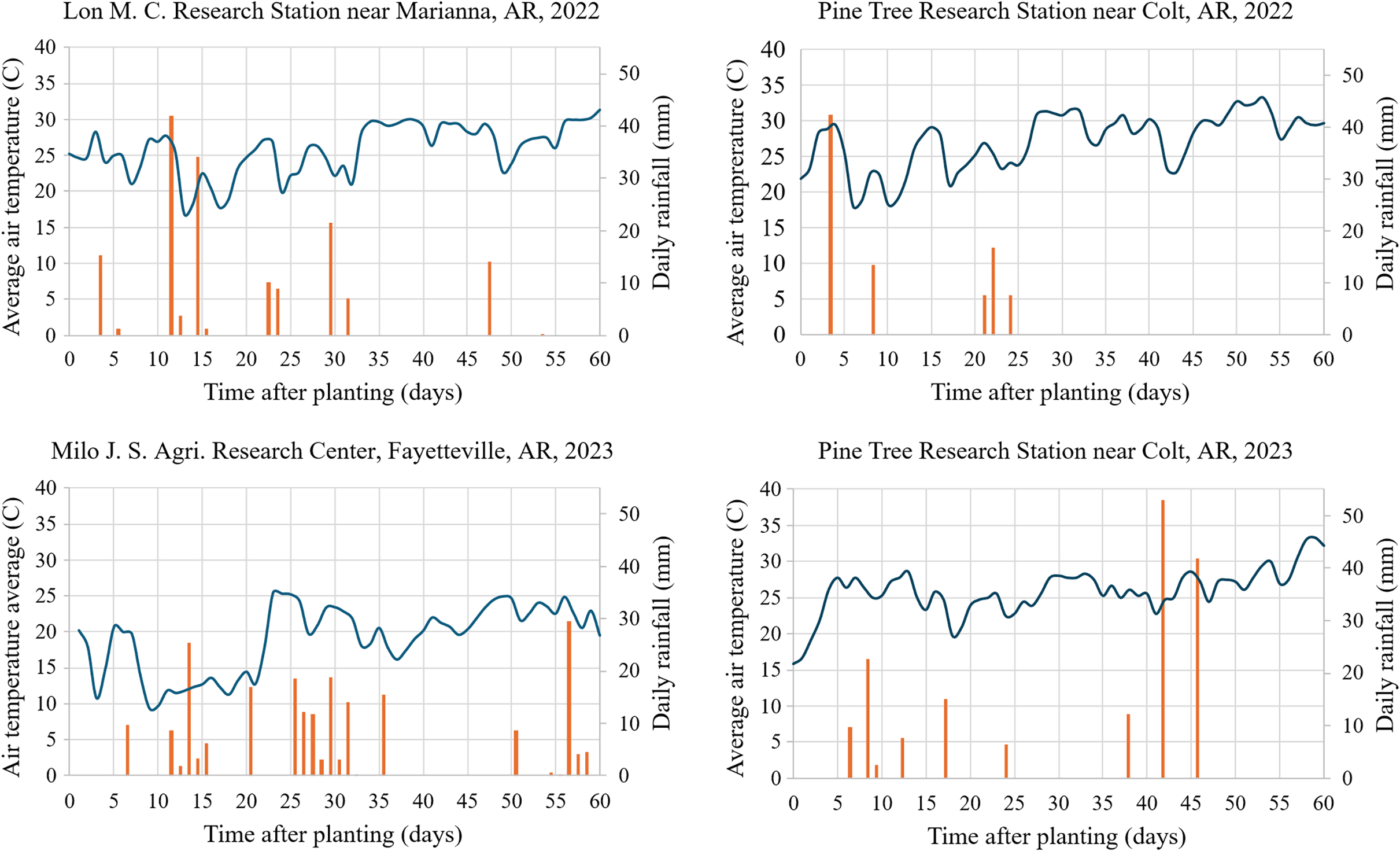

The fields were irrigated twice weekly starting when rice was at the 5-leaf stage, except when 2.5 cm or more of rain occurred. Soil fertility at each experimental site was managed following the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture recommendations based on soil test values (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Slaton, Wilson and Norman2016). Natural Palmer amaranth populations were allowed to germinate following rice planting, and no other management efforts (excluding the fluridone treatments) were used prior to postemergence treatments. Nontarget weeds were controlled using fenoxaprop (Ricestar HT; Bayer CropScience) and halosulfuron + thifensulfuron (PermitPlus; Gowan Company, Yuma, AZ) in the entire experiment. Additionally, pendimethalin (Prowl H2O; BASF Corporation, Research Triangle Park, NC), quinclorac (Facet L; BASF), and propanil (Stam; UPL Limited, King of Prussia, PA) were used in the weed-free plots. Herbicides were applied using a CO2-pressurized hand-held backpack sprayer calibrated to deliver 140 L ha−1 at 4.8 kph equipped with AIXR 110015 nozzles (TeeJet Technologies, Glendale Heights, IL). Air temperature and precipitation data were monitored daily using a weather station within 1 km of each experimental site, except for P2022 and P2023 (Figure 1). For those two sites, daily rain amounts were measured with a gauge located 1 km away, while temperature data were obtained from a weather station located 20 km from each site.

Figure 1. Daily recorded air temperature (C) and rain amounts (mm) over a 24-h period, from the planting until the last day of Palmer amaranth cumulative density and control evaluations. The blue line represents the daily average air temperature, and the orange bars indicate daily rainfall.

Visible crop injury was evaluated at 2 and 5 wk after emergence (WAE) using a scale from 0 to 100, with 0% indicating no injury and 100% representing plant death (Frans et al. Reference Frans, Talbert, Marx, Crowley and Camper1986). Palmer amaranth control was visually assessed 4 and 8 WAT using a scale from 0% to 100%, with 0% representing no control and 100% indicating complete control. Palmer amaranth cumulative density was assessed at 4 and 8 WAT using two 1-m−2 quadrants randomly placed in each subplot. Before rice harvest, Palmer amaranth male and female densities were recorded, and aboveground biomass was collected from two 1-m−2 quadrants. If only a few plants remained in the plot, all were collected, and the density was reported per square meter, considering the entire plot size. All biomass was dried in an oven at 66 C until constant mass, and the final weight was recorded. Subsequently, each Palmer amaranth female plant was threshed, and the ground plant material was separated from the seeds using a 20-mesh sieve followed by a vertical air column seed cleaner (King Reference King, Norsworthy, Butts, Barber, Drescher and Godar2024a, Reference King, Norsworthy, Butts, Fernandes, Drescher and Avent2024b; Miranda et al. Reference Miranda, Jhala, Bradshaw and Lawrence2021; Woolard et al. Reference Woolard, Norsworthy, Roberts, Barber, Thrash, Sprague and Godar2024). After cleaning, a 200-seed subsample from three random subplots per site-year was weighed, and the average weight was used to calculate the number of seeds per square meter. Seed production for P2022 was not assessed because there were too few female plants. Rough rice yield was collected at maturity using a small-plot combine that harvested the middle four rows of each subplot. Grain yield moisture was adjusted to 12%. Harvest was not possible in the plots with no postemergence herbicide application because the high Palmer amaranth infestation prevented the combine from operating; therefore, rough rice yield was not reported for that postemergence treatment.

Data Analysis

All data were analyzed using R statistical software (v.4.3.3; R Core Team 2023) and all data were fit to a generalized linear mixed model using the glmmTMB function (glmmTMB package; Brooks et al. Reference Brooks, Kristensen, van Benthem, Magnusson, Berg, Nielsen, Skaug, Mächler and Bolker2017). The postemergence programs none and single application were identical until florpyrauxifen-benzyl was applied 6 wk after emergence in the single application treatment, which occurred after all rice injury evaluation assessments. Moreover, there were no differences in rice injury among these postemergence treatments compared to the weed-free plots (P > 0.05). Therefore, injury at each evaluation time was averaged across postemergence treatments by fluridone rate. For Palmer amaranth control and its cumulative density at 4 and 8 WAT, only the no-postemergence treatment was included in the analysis because the goal was to evaluate the length of Palmer amaranth control achieved with fluridone treatments only.

Cumulative Palmer amaranth density was fit to a generalized linear mixed model, with fluridone rate and site-year as fixed effects and block as a random effect. At each evaluation, the interaction of fluridone rate and site-year was significant (P < 0.05), which can be partially attributed to the drastic differences in Palmer amaranth density among site-years. Therefore, all variables were analyzed by site-year because Palmer amaranth density can strongly influence the response of the other variables. For rice injury, Palmer amaranth control, and cumulative density, fluridone rate was treated as a fixed effect, and block was considered a random effect. All data were analyzed to assess whether the assumptions of normality were satisfied using the Shapiro-Wilk and Levene tests. A beta distribution was used to analyze rice injury and Palmer amaranth control, and a Poisson distribution was used for cumulative Palmer amaranth density if the data did not meet the assumptions of normality (Gbur et al. Reference Gbur, Stroup, McCarter, Durham, Young, Christman, West and Kramer2012; Stroup Reference Stroup2015).

Variables assessed at rice harvest (Palmer amaranth density, biomass, seed production, and rough rice yield) were analyzed in accordance with the split-plot arrangement. The weed-free postemergence treatment was excluded from the analysis of all Palmer amaranth assessments because no weeds were present. In the rough rice yield analysis, the no-postemergence-treatment was removed from the analysis because rice harvest was not feasible due to the high Palmer amaranth infestation. Postemergence treatment and fluridone rate were considered fixed effects, and postemergence treatment and fluridone rate were nested within block, which was considered a random effect. A negative binomial distribution was used for all seed production data analysis, and a log transformation was used for Palmer amaranth biomass whenever the data did not meet the assumptions of normality. For such data, back-transformed values are presented.

Analysis of variance was conducted using Type III Wald chi-square tests with the car package (Fox and Weisberg Reference Fox J2019). Treatment-estimated marginal means (Searle et al. Reference Searle, Speed and Milliken1980) were calculated using the emmeans package (Lenth Reference Lenth2022) following analysis of variance. Significant differences among treatments were identified with a compact letter display generated by the multcomp package (Hothorn et al. Reference Hothorn, Bretz and Westfall2008). Estimated marginal means included post hoc Tukey HSD (α = 0.05) adjustments, and the compact letter display was obtained with the multcomp:cld function.

Results and Discussion

In-season Rice Response and Palmer Amaranth Control with Fluridone Applied Preemergence Without Postemergence Herbicides

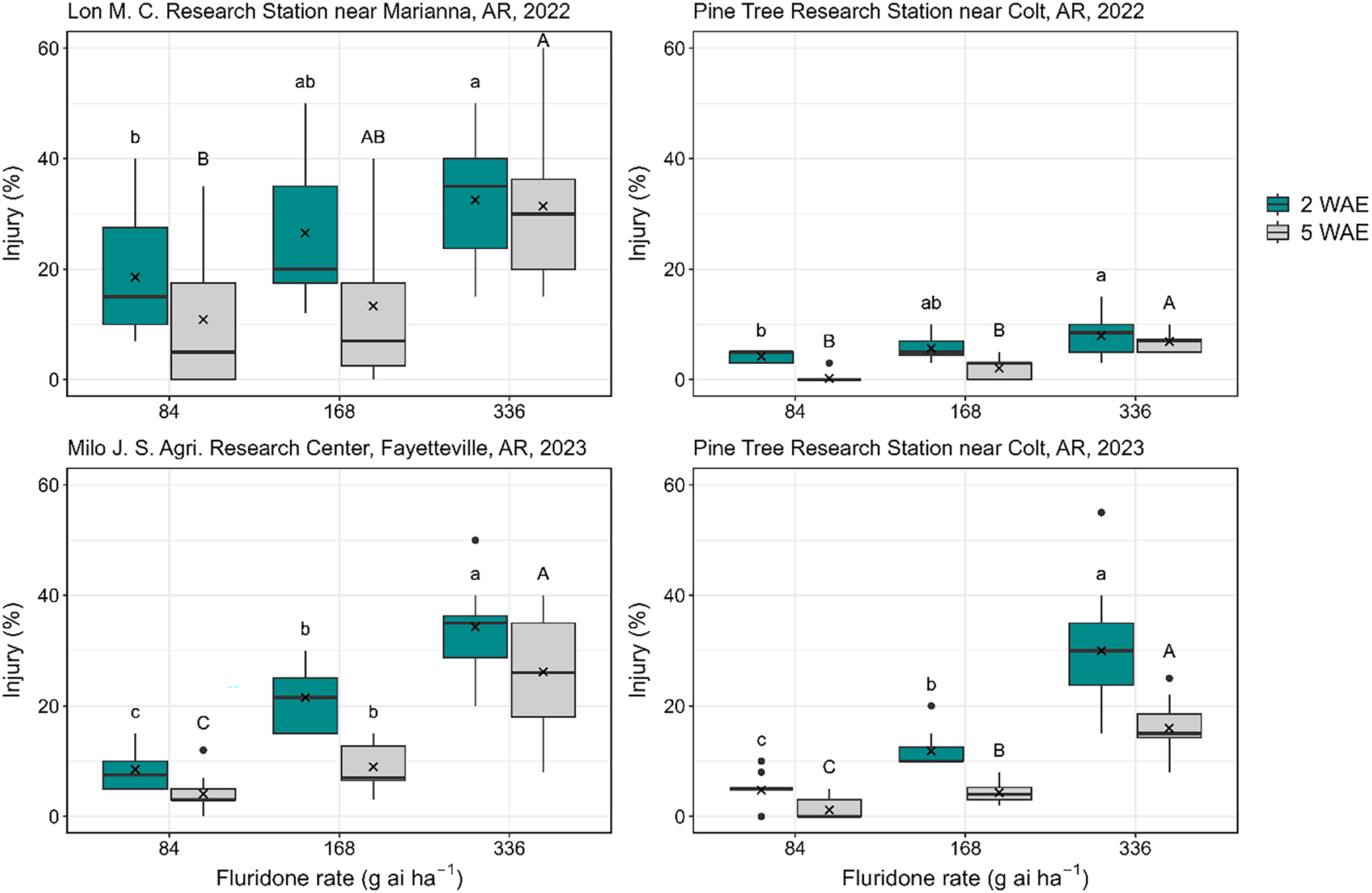

Rice injury varied across site-years in response to fluridone rate (Figure 2) with characteristic symptomology that included bleached and chlorotic plants (Sandmann et al. Reference Sandmann, Schmidt, Linden and Böger1991; Waldrep and Taylor Reference Waldrep and Taylor1976). At P2022, injury was minimal (<8%) at all fluridone rates. Regardless of the site-year, the 2× label rate caused the greatest injury (7% to 34%) at both evaluations. Injury from the 1× rate reached 27% at 2 WAE but did not exceed 11% in any site-year at 5 WAE, indicating crop recovery over time. Similarly, in other research, a preemergence application of fluridone at 224 g ai ha−1 caused 32% rice injury at 1 WAE and dropped to 18% by 3 WAE on Dewitt and Calhoun silt loam soils prior to flood establishment (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Norsworthy, Scott, Hardke and Lorenz2018). In Calhoun silt loam soil, fluridone caused ≤42% to the RT7321 FP hybrid at 6 WAE following a preemergence application of the 1× rate in a paddy system (Souza et al. Reference Souza, Norsworthy, Carvalho-Moore, Godar, Fernandes and Butts2025a). Although rice injury from the 1× rate was no more than 11% at 5 WAE, fluridone should not be applied before the 3-leaf rice growth stage, according to the product label (Anonymous 2023a). Additionally, this study was conducted in the higher, drier portion of the field, and results could differ if the herbicide was applied to the bottom of the field, where flooding can occur.

Figure 2. Distribution of rice injury (%) in response to fluridone treatments at 2 and 5 wk after emergence (gray and green bars, respectively). Boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR), with the lower edge indicating the 25th percentile and the upper edge denoting the 75th percentile. The horizontal line within the box denotes the median, and × indicates the mean. Vertical lines (whiskers) extend to 1.5 times the IQR, and dots represent the outliers. Means followed by the same lowercase letter 2 wk after emergence and means followed by the same uppercase letter 5 wk after emergence are not different within the same evaluation time at each site-year according to Tukey’s HSD (α = 0.05). Abbreviation: WAE, weeks after emergence.

Environmental conditions play a major role in crop response to herbicides (Beesinger et al. Reference Beesinger, Norsworthy, Butts and Roberts2022b; Bond and Walker Reference Bond and Walker2011; Godara et al. Reference Godara, Norsworthy, Butts, Roberts and Gbur2022; Hammerton Reference Hammerton1967). For instance, rice plants treated with quizalofop and maintained under low temperatures experienced greater injury than those kept under warmer conditions (Godara et al. Reference Godara, Norsworthy, Butts, Roberts and Gbur2022). Soil moisture also affects crop response to herbicides; for example, elevated soil moisture following fluridone application can result in greater visible rice injury (Butts et al. Reference Butts, Souza, Norsworthy, Barber and Hardke2024; Martin et al. Reference Martin, Norsworthy, Scott, Hardke and Lorenz2018). Thus, variations in rice response to fluridone across site-years might have been influenced by differences in temperature and rainfall before irrigation began at each location (Figure 1).

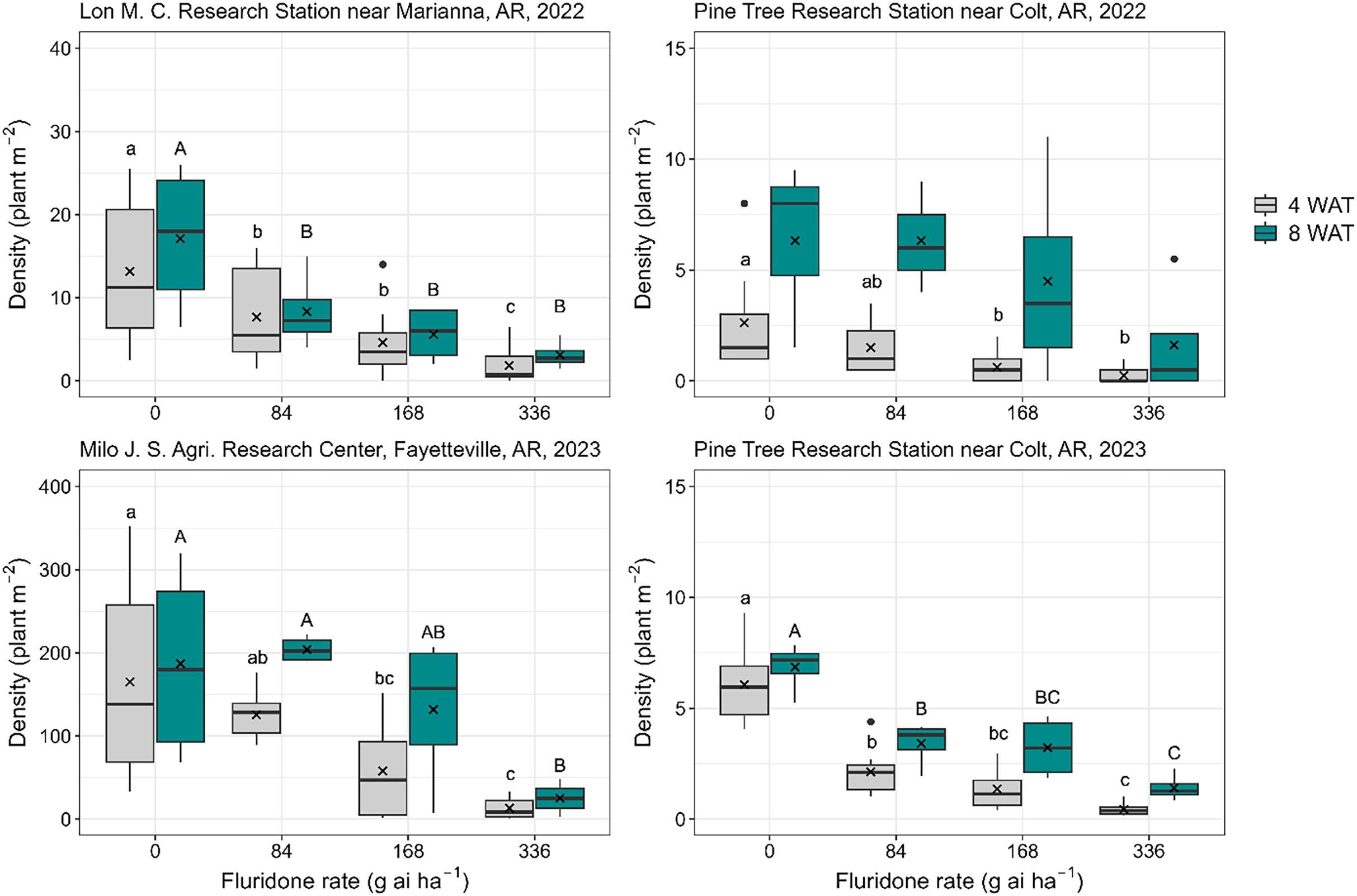

Palmer amaranth density was decreased when the 1× and 2× rates of fluridone were applied compared with the nontreated control in all site-years at 4 WAT, with reductions ranging from 65% to 78% when the 1× rate was applied and 88% to 93% when the 2× rate was applied (Figure 3). Although there was an increase in the number of plants across treatments at 8 WAT, the 2× rate of fluridone continued to suppress Palmer amaranth emergence compared to the nontreated control in 3 of the 4 site-years. The number of Palmer amaranth plants after applications of 0.5× and 1× rates of fluridone differed from the nontreated control only at M2022 and P2023. The decrease in fluridone efficacy at 8 WAT was expected because the amount of fluridone remaining in the soil diminishes over time (Banks et al. Reference Banks, Ketchersid and Merkle1979; Schroeder and Banks Reference Schroeder and Banks1986).

Figure 3. Distribution of Palmer amaranth cumulative density (plants m−2) in response to fluridone at 4 and 8 wk after treatment (gray and green bars, respectively). Boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR), with the lower edge indicating the 25th percentile and the upper edge denoting the 75th percentile. The horizontal line within the box denotes the median, and × indicates the mean. Vertical lines (whiskers) extend to 1.5 times the IQR, and dots represent the outliers. Means followed by the same lowercase letter 1 mo after treatment and means followed by the same uppercase letter 2 mo after treatment are not different within the same evaluation time at each site-year according to Tukey’s HSD (α = 0.05). If P > 0.05, letters are not present. Abbreviation: WAT, weeks after treatment.

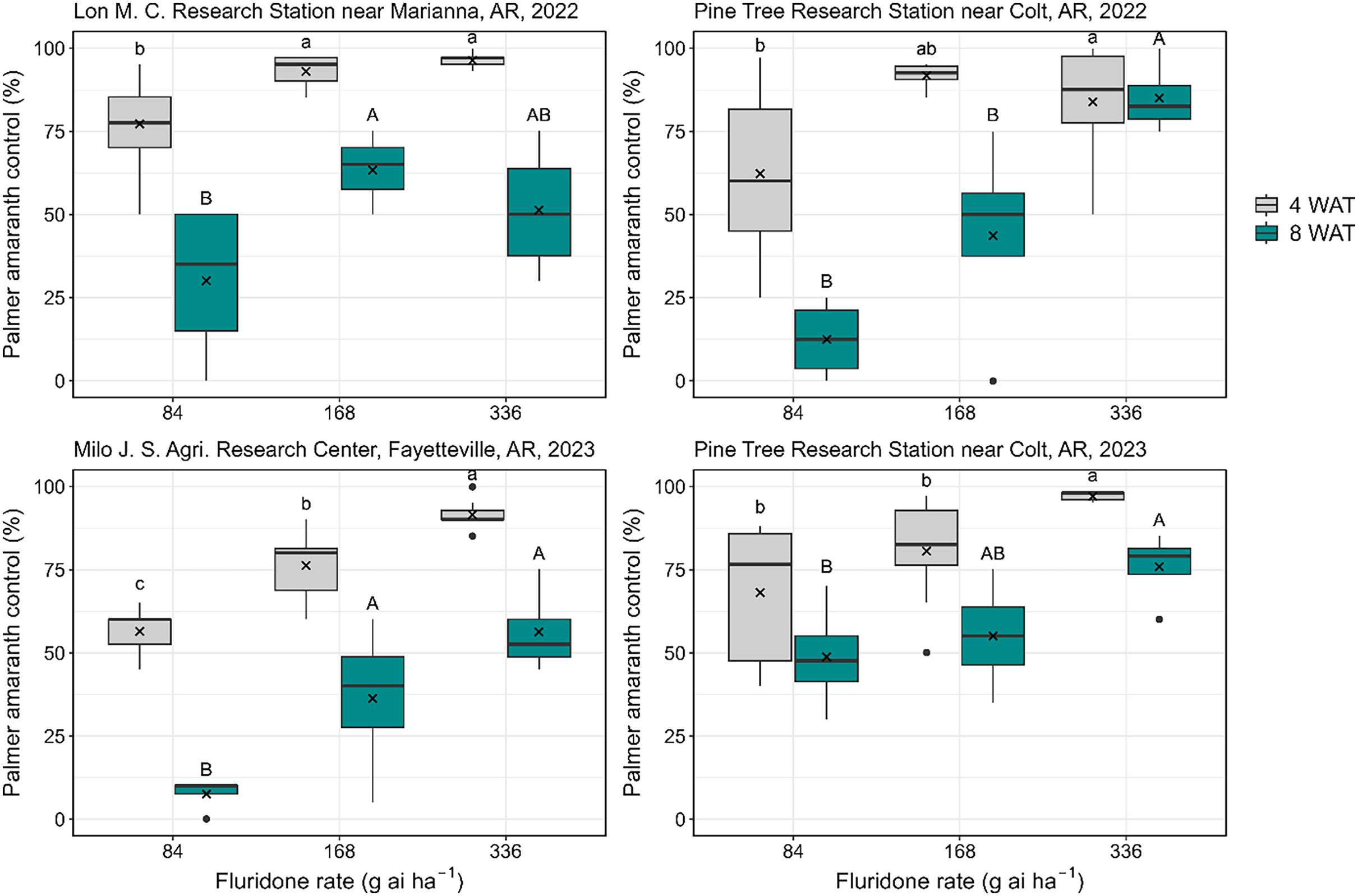

Of the 4 site-years, fluridone applied at the 1× and 2× rates provided similar Palmer amaranth control in 2 site-years (M2022 and P2022) at 4 WAT, ranging from 85% to 95% control, whereas in the other 2 site-years, the 2× rate resulted in the greatest control (Figure 4). These results suggest that fluridone applied at the 1× rate may be less effective in controlling Palmer amaranth than the 2× rate. When used at 168 g ai ha−1 for weed control in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) and cotton, the label requires tank-mixing it with another residual herbicide (Anonymous 2023a). Based on the results presented here, a similar approach may be recommended for rice for successful Palmer amaranth control.

Figure 4. Distribution of Palmer amaranth visual control (%) in response to fluridone at 4 and 8 wk after treatment (gray and green bars, respectively). Boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR), with the lower edge indicating the 25th percentile and the upper edge denoting the 75th percentile. The horizontal line within the box denotes the median, and × indicates the mean. Vertical lines (whiskers) extend to 1.5 times the IQR, and dots represent the outliers. Means followed by the same lowercase letter 1 mo after treatment and means followed by the same uppercase letter 2 mo after treatment are not different within the same evaluation time at each site-year according to Tukey’s HSD (α = 0.05). Abbreviation: WAT, weeks after treatment.

By 8 WAT, Palmer amaranth density increased (Figure 3), and consequently, control dropped across all treatments and site-years. At this evaluation, the 2× rate resulted in greater Palmer amaranth control than the 0.5× rate in 3 site-years, and was comparable to that of the 1× rate at M2022, F2023, and P2023 (Figure 4). Similarly, fluridone applied preemergence to a Zachary silt loam soil at the 2× rate resulted in a decrease in Palmer amaranth control from 96% at 4 WAT to 87% by 7 WAT when rain was adequate (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Norsworthy, Barber and Gbur2016). In the same study, when moisture was insufficient, only 43% control was observed 4 WAT, and Palmer amaranth overtook the crop in the plots 7 WAT at one of the locations where testing occurred.

At-harvest Palmer Amaranth Assessments and Rough Rice Yield with Fluridone Applied Preemergence and Various Postemergence Treatments

The interaction of postemergence treatment and fluridone rate applied preemergence was significant for the F2023 and P2023 site-years for Palmer amaranth density at rice harvest (Table 2). Applying florpyrauxifen-benzyl at 6 wk after rice emergence after fluridone had been applied preemergence, regardless of the preemergence rate, resulted in the greatest reduction in Palmer amaranth in most instances at both site-years. At F2023, no fluridone applied preemergence followed by a postemergence application of florpyrauxifen-benzyl provided results that were comparable to when fluridone was applied alone at the 1× and 2× rates. Similarly, at P2023, all treatments that contained florpyrauxifen-benzyl were comparable to those with fluridone applied alone at the 2× rate. Averaged across fluridone rates, a single postemergence application of florpyrauxifen-benzyl resulted in the fewest Palmer amaranth escapes at the end of the season compared to no postemergence treatment at the M2022 site. No differences in male:female ratios were observed among treatments across site-years (data not shown).

Florpyrauxifen-benzyl is an effective option for postemergence control of Palmer amaranth in rice when applied at the appropriate rate and weed size, and especially when applied sequentially (Beesinger et al. Reference Beesinger, Norsworthy, Butts and Roberts2022a; Wright et al. Reference Wright, Norsworthy, Roberts, Scott, Hardke and Gbur2021). In this study, however, florpyrauxifen-benzyl was applied at the 0.5× labeled rate, and several Palmer amaranth plants exceeded the weed size recommended by the label at the time of application (≤20 cm; Anonymous 2023b), which likely led to Palmer amaranth escapes at the end of the season. These results suggest that florpyrauxifen-benzyl should be applied earlier and at the label-recommended rate for enhanced Palmer amaranth control.

Furthermore, sequential applications of florpyrauxifen-benzyl or other effective herbicides with postemergence activity are necessary to achieve season-long control of Palmer amaranth because fluridone exhibits minimal postemergence activity (Beesinger et al. Reference Beesinger, Norsworthy, Butts and Roberts2022a; Miller and Norsworthy Reference Miller and Norsworthy2018; Waldrep and Taylor Reference Waldrep and Taylor1976). Unlike the present study, King et al. (Reference King, Norsworthy, Butts, Barber, Drescher and Godar2024b) examined a full herbicide program that employed preemergence herbicides (fluridone + clomazone at 84 and 336 g ai ha−1, respectively) followed by sequential applications of a residual herbicide (fluridone at 84 g ai ha−1) and a postemergence herbicide (florpyrauxifen-benzyl at 15 g ai ha−1), which resulted in complete Palmer amaranth control at rice maturity in most instances. No Palmer amaranth control was evaluated using fluridone alone in the research by King et al. (Reference King, Norsworthy, Butts, Barber, Drescher and Godar2024b).

Regarding Palmer amaranth biomass at rice harvest, the main effect of the postemergence program was significant for P2022, F2023, and P2023 (Table 3). In all 3 site-years, a single application of florpyrauxifen-benzyl resulted in the greatest reduction in Palmer amaranth biomass. No effect of fluridone rate was observed on Palmer amaranth biomass. Likewise, King et al. (Reference King, Norsworthy, Butts, Barber, Drescher and Godar2024b) reported that treatments combining clomazone (336 g ai ha−1) and fluridone (1× rate) applied preemergence and florpyrauxifen-benzyl applied mid-season (at the same rate used in this study) resulted in almost 96% reduction in Palmer amaranth biomass compared to a treatment without florpyrauxifen-benzyl. Furthermore, the same research reported a 95% reduction in seed production for plants that remained in the field following treatments that contained florpyrauxifen-benzyl.

All treatments with florpyrauxifen-benzyl resulted in a reduction of at least 94% in Palmer amaranth seed production compared to no herbicides applied postemergence (Table 4). Conversely, Palmer amaranth seed production was never reduced when fluridone by itself was applied preemergence, regardless of rate, which points to the need for an effective postemergence herbicide. In other research, an average of 350 to 900 Palmer amaranth seeds per square meter were produced when research plots were treated with florpyrauxifen-benzyl at 15 g ai ha−1, averaged across both single and sequential applications and different weed sizes (Beesinger et al. Reference Beesinger, Norsworthy, Butts and Roberts2022a). When growing without competition and emerging earlier in the season, Palmer amaranth can produce up to 600,000 seeds per plant (Keeley et al. Reference Keeley, Carter and Thullen1987). The crop being grown can also influence Palmer amaranth seed production (Burke et al. Reference Burke, Schroeder, Thomas and Wilcut2007; Jha et al. Reference Jha, Norsworthy, Bridges and Riley2008; Massinga et al. Reference Massinga, Currie, Horak and Boyer2001; Webster and Grey Reference Webster2015). For example, in furrow-irrigated rice, Palmer amaranth produced 115,000 seeds plant−1 when it emerged with the crop (King et al. Reference King, Norsworthy, Butts, Fernandes, Drescher and Avent2024a). Moreover, Beesinger et al. (Reference Beesinger, Norsworthy, Butts and Roberts2022a) reported that Palmer amaranth survivors from early-season florpyrauxifen-benzyl applications produced more seeds than those treated later in the season, likely due to the extended recovery time. Although fluridone did not reduce Palmer amaranth seed production at rice harvest, its residual activity is crucial for reducing the number of Palmer amaranth plants requiring postemergence control, thereby decreasing pressure on postemergence herbicides, ultimately delaying resistance (Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Ward, Shaw, Llewellyn, Nichols, Webster, Bradley, Frisvold, Powles, Burgos and Witt2012). Combined with postemergence applications applied at the proper weed size, herbicide programs incorporating fluridone can successfully manage Palmer amaranth, ultimately preventing soil seedbank replenishment (King et al. Reference King, Norsworthy, Butts, Barber, Drescher and Godar2024b; Hill et al. Reference Hill, Norsworthy, Barber and Gbur2016).

Rough rice yield differed among postemergence treatments at P2022 and F2023 (Table 5). At both locations, the weed-free postemergence treatment resulted in a greater rough rice yield than the treatment containing a single application of florpyrauxifen-benzyl. As previously discussed, when florpyrauxifen-benzyl was applied postemergence, some plants remained when the rice was harvested (Table 2), which likely contributed to the lower yield. According to King et al. (Reference King, Norsworthy, Butts, Fernandes, Drescher and Avent2024a), Palmer amaranth that emerges 3.5 wk after the crop emerges can cause up to 50% reduction in rough rice yield when the crop is located 0.2 to 0.6 m from the weed in furrow-irrigated rice. When averaged across postemergence treatment, no yield loss was observed as a function of fluridone rate applied preemergence. These findings differ from those reported by Butts et al. (Reference Butts, Souza, Norsworthy, Barber and Hardke2024), that the 2× rate of fluridone applied at the 3-leaf rice stage resulted in a rough rice yield penalty under weed-free conditions in a field in which the topsoil had been removed. Moreover, King et al. (Reference King, Norsworthy, Butts, Barber, Drescher and Godar2024b) reported rice yield loss in fields under weedy conditions only in the nontreated control compared to other treatments containing clomazone with single or sequential applications of florpyrauxifen-benzyl and/or fluridone at different rates.

Practical Implications

Injury to rice from fluridone applied preemergence in the upper portion of a furrow-irrigated field did not translate to yield loss. However, previous research has indicated that injury increases with higher moisture content, thus results may be different if fluridone is applied to the lower, flooded part of the field (Butts et al. Reference Butts, Souza, Norsworthy, Barber and Hardke2024; Martin et al. Reference Martin, Norsworthy, Scott, Hardke and Lorenz2018; Souza et al. Reference Souza, Norsworthy, Carvalho-Moore, Godar, Fernandes and Butts2025a). Therefore, to minimize the risk of crop injury, fluridone should not be applied before rice reaches the 3-leaf growth stage (Anonymous 2023a).

Fluridone at 1× and 2× rates reduced Palmer amaranth density in all site-years compared to the nontreated control at 4 WAT; however, using fluridone alone does not fully achieve the management goal of Palmer amaranth. Additionally, growers should be aware that fluridone efficacy may decline in soils with higher contents of clay or organic matter than those in the present study (Anonymous 2023a). Including a postemergence application of florpyrauxifen-benzyl improved Palmer amaranth control, resulting in fewer escapes in the field at rice maturity and lowering seed production, aiding weed management in subsequent years by limiting soil seedbank replenishment. However, Palmer amaranth plants remained in the field and likely reduced rough rice yield. Therefore, overlapping postemergence herbicides applied at the appropriate weed growth stage with fluridone and/or other soil residual herbicides is paramount for achieving optimal season-long control, minimizing seed return to the soil seedbank, and thereby delaying the development of herbicide resistance (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Norsworthy, Barber and Gbur2016; King et al. Reference King, Norsworthy, Butts, Barber, Drescher and Godar2024b; Kouame et al. Reference Kouame, Butts, Norsworthy, Davis and Piveta2024; Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Ward, Shaw, Llewellyn, Nichols, Webster, Bradley, Frisvold, Powles, Burgos and Witt2012).

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the support of SePRO Corporation and the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture. The authors also acknowledge the valuable contributions of graduate students, faculty, and staff at the University of Arkansas.

Funding

SePRO Corporation and the Arkansas Rice Research and Promotion Board provided partial support for this research.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.