In November 2022, shortly before the United States midterm elections, President Joe Biden urged voters to support Democratic candidates, warning that Republicans imperiled American democracy and declaring that “democracy was on the ballot” (quoted in Baker Reference Baker2022). This moment highlighted an important milestone in American political discourse. While Biden continued to frame democracy as the central issue facing voters, polling data from October 2024 show that Americans’ primary concerns were more concrete: economic stability, healthcare access, and Supreme Court appointments (Brenan Reference Brenan2024; Pew Research Center 2024). This gap between political rhetoric and voter priorities raises important questions: What does democracy mean to the American electorate? Are Americans fundamentally principle holders when it comes to democracy, or benefit seekers willing to trade democratic principles for economic well-being? Research suggests that while democracy remains a widely embraced ideal (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2003), its interpretation varies significantly among voters (Ariely and Davidov Reference Ariely and Davidov2011; Schedler and Sarsfield Reference Schedler and Sarsfield2007), making it a powerful but ambiguous rallying cry for political mobilization.

In an era of political tension and democratic backsliding, understanding how citizens conceptualize democracy is crucial. Traditional surveys ask participants about their satisfaction with democracy and their perception of their country’s democratic status without providing a clear definition of democratic government (Haerpfer et al. Reference Haerpfer, Inglehart, Moreno, Welzel, Kizilova, Diez-Medrano, Pippa Norris and Puranen2022). This approach raises significant concerns about data validity, as democracy is a complex and multifaceted concept (Osterberg-Kaufmann, Stark, and Mohamad-Klotzbach Reference Osterberg-Kaufmann, Stark and Mohamad-Klotzbach2020). The issue of measuring attitudes toward democracy has become hotly debated in the literature. Recent scholarship highlights the inconsistencies in these subjective measures (Adserà, Arenas, and Boix Reference Adserà, Arenas and Boix2023; Møller and Skaaning Reference Møller and Skaaning2010; Osterberg-Kaufmann, Stark, and Mohamad-Klotzbach Reference Osterberg-Kaufmann, Stark and Mohamad-Klotzbach2020), leading some researchers to shift toward more objective indicators such as electoral competitiveness, executive constraints, and media freedom (Little and Meng Reference Little and Meng2023). While these macrolevel measures offer valuable insights, they fail to capture the nuanced ways that citizens understand and value democratic principles. Political theorists and scholars have long argued that democracy requires democrats to be successful (e.g., Diamond Reference Diamond1999; Linz and Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1996; Mattes and Bratton Reference Mattes and Bratton2007; Nisbet, Stoycheff, and Pearce Reference Nisbet, Stoycheff and Pearce2012). To fully grasp democracy’s role in society, therefore, objective macrolevel indexes must be complemented with subjective citizen-level measures (Fuchs and Roller Reference Fuchs and Roller2018), as citizens’ conceptualization of democratic governance influences whether they promote democracy or deviate from democratic norms (Adserà, Arenas, and Boix Reference Adserà, Arenas and Boix2023; Cho Reference Cho2014; Oser and Hooghe Reference Oser and Hooghe2018).

This project provides several key contributions to the understanding of democratic attitudes. First, it offers an empirical examination of the current debate on the conceptualization of democracy and the measurement of democratic preferences (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Hicken and Kroenig2011; Little and Meng Reference Little and Meng2023; Lu and Chu Reference Lu and Chu2021). Second, rather than relying on self-report survey items, this project tests how citizens navigate trade-offs between different aspects of democracy using a conjoint experimental design. While previous work has examined democratic attitudes in isolation, this study forces participants to choose between competing democratic goods, revealing their true preferences and priorities. Unlike traditional survey research using self-report items, our approach allows participants to compare different aspects of democracy and choose which are most important based on hypothetical profiles. This method allows a more accurate assessment of the relationship between political predispositions and democratic preferences, illuminating potential cleavages within the US public. Third, this research breaks new ground by incorporating preferences for distributive democracy alongside more traditional concepts of procedural and liberal democracy. The finding that preferred economic conditions—when not tied to a specific candidate or party policy—generally moderate support for other democratic principles is another significant contribution to the literature.

Conceptualization of Democracy: A Social Constructionist Approach

Several challenges complicate conceptualizing a multifaceted idea like democracy. First, there is the constructionist-versus-positivist debate surrounding the concept of democracy; social constructionists argue there are many versions of reality and therefore there is not “one” idea of democracy but many interpretations (Adler Reference Adler1997). Then there is the competing view of positivism, which has constraints that allow questions about truth and verifiable answers (Dessler Reference Dessler1999). This implies there is a verifiable understanding of democracy that can be empirically tested. Osterberg-Kaufmann, Stark, and Mohamad-Klotzbach (Reference Osterberg-Kaufmann, Stark and Mohamad-Klotzbach2020) distinguish meanings of democracy from understandings of democracy by arguing that understandings of democracy consist of different representations of an identical object and allow uniform measurement, whereas meanings imply conceptual ambiguity and contestation.

The tension between these two approaches is then further complicated by the debate between a universalist approach toward democracy versus a relativistic approach (Osterberg-Kaufmann, Stark, and Mohamad-Klotzbach Reference Osterberg-Kaufmann, Stark and Mohamad-Klotzbach2020; Reference Osterberg-Kaufmann, Stark and Mohamad-Klotzbach2023). The universalist approach argues that there is one understanding of democracy that can be understood by all people in all nations, since they all have similar reasoning capabilities (Zapf Reference Zapf, Da Rosa, Schubert and Zapf2016). Whereas the relativist approach argues that individuals understand democracy through the lens of culture, so there will be many varying interpretations of what democracy means because not all cultures agree on the same norms being “correct” (Zapf Reference Zapf, Da Rosa, Schubert and Zapf2016).

Newer approaches, such as the Varieties of Democracy (V-DEM) project, use expert ratings to create composite definitions of democracy that span across several interconnecting conceptualizations (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Hicken and Kroenig2011), a process that draws from a social constructionist idea of democracy that allows for several definitions but uses positivist methods to measure them. To understand how citizens conceptualize democracy, we adopt V-DEM’s approach of providing several meanings of democracy and focusing on three specific understandings.

The tension between these two debates has led to a myriad of approaches to understanding democracy from the macro to the micro level. By providing richer scenarios for participants to choose from, this study increases the intension of the concept of democracy—that is, the set of defining attributes or properties it encompasses—while also prioritizing its extension, meaning the breadth of its application across participants’ understandings (Osterberg-Kaufmann, Stark, and Mohamad-Klotzbach Reference Osterberg-Kaufmann, Stark and Mohamad-Klotzbach2020; Reference Osterberg-Kaufmann, Stark and Mohamad-Klotzbach2023). The goal of this project is to identify patterns in which conceptualizations of democracy form at the citizen level. To do this, we will be taking a moderate social constructionist perspective.

Dimensions of Democracy: Processes, Protections, and Outcomes

To understand how Americans conceptualize democracy, we must first unpack it as a concept. Democracy is a nuanced idea with many competing scholastic definitions. The most widely used definition is the minimalist approach, which emphasizes democracy as a process centered on elections (Schumpeter [1942] Reference Schumpeter2013). However, this narrow focus overlooks other essential qualities of democratic governance, such as protections against discrimination and freedom to criticize the government. To address these gaps, scholars have broadened their definitions to combine democratic procedures with liberal democratic principles, emphasizing civil liberties and individual freedoms (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Hicken and Kroenig2011). Additional frameworks include deliberative democracy, which focuses on mutual communication and reflection on common issues (Bächtiger et al. Reference Bächtiger, Dryzek, Mansbridge and Warren2018; Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Hicken and Kroenig2011), and egalitarian democracy, which highlights economic equality within a democratic society (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Hicken and Kroenig2011). Each of these definitions captures necessary but individually insufficient aspects of democratic governance.

Monolithic definitions of democracy fail to capture how understanding of democratic governance varies both across and within nations. Research reveals stark differences between democratic and nondemocratic societies: citizens in nondemocratic nations tend to associate democracy with economic prosperity, obedience, and populist leadership, while those in democratic nations emphasize elections and rights protections (Kirsch and Welzel Reference Kirsch and Welzel2019; Zagrebina Reference Zagrebina2020). Even within established democracies, citizens differ in how they prioritize democratic components: while free and fair elections are broadly recognized as essential, the perceived importance of procedural elements varies significantly (Davis, Goidel, and Zhao Reference Davis, Goidel and Zhao2021). These multiple, often conflicting conceptualizations of democracy across and within nations challenge the validity of existing research on democratic support.

Thriving democracies must ensure citizens have equal access to political decision making and receive fair societal outcomes. Failure to do so results in a crisis of regime legitimacy, and citizens are less likely to trust the government and comply with its decisions (Tyler Reference Tyler2006). However, citizens are often willing to prioritize some goods over others. Lu and Chu (Reference Lu and Chu2021) identify three categories of citizens: those who believe democratic principles are essential regardless of circumstances (principle holders), those who are willing to trade those principles for more favorable outcomes (benefit seekers), and those who are unsure (fence sitters). Depending on whether one’s favored party is in power and how democracy is understood, Americans may shift between these roles (Krishnarajan Reference Krishnarajan2023). To observe this process of trade-offs, we need to split our overall conceptual definition of democracy into more distinct categories.

To simplify the concept of democracy and better observe trade-offs between principles and outcomes, we assert that democratic governance from a citizen perspective should be divided into three components: procedural democracy, distributive democracy, and liberal democracy. These three concepts represent separate dimensions of democracy that can often be conflated by the public: processes, outcomes, and protections. By separating these attributes of democracy, we can test whether participants value some aspects of democratic government over others, and whether voters believe “the ends justify the means.”

We draw inspiration for this structure from Pippa Norris, Sarah Cameron, and Thomas Wynter (Reference Norris, Cameron and Wynter2018) who employ a similar categorization when examining electoral integrity. Norris, Cameron, and Wynter distinguish between confidence in political institutions, regime performance, and regime principles. They define regime principles as reflecting the core procedures and institutions that are at the heart of functioning democracies, whereas they define regime performance as system “outputs” such as economic growth. These factors represent distinct priorities that citizens may emphasize when conceptualizing democratic government. More recent work has used a similar strategy to disentangle the effects of collinear concepts, identifying the defining features of a political system as access to power, the policy-making process, and performance (Papp et al. Reference Papp, Navarro, Russo and Nagy2024). We adopt a similar approach for parsimony but adapt these three categories to fit specific understandings of democracy.

Procedural and distributive democracy extend the concepts of procedural and distributive fairness to the broader framework of governance, highlighting the trade-off between democratic principles and outcomes. Procedural justice suggests that involving citizens in the decision-making process makes the outcome more acceptable (Lind and Tyler Reference Lind and Tyler1988), emphasizing individual participation and control over results (Thibaut et al. Reference Thibaut and Walker1975). Similarly, procedural democracy focuses on adherence to democratic processes and legal norms. What sets democratic leaders apart from nondemocratic ones are the norms guiding their acquisition of power and the laws holding them accountable (Schmitter and Karl Reference Schmitter and Karl1991). Thus, procedural democracy draws from this literature, defining democracy as a free and fair system in which decisions are made and power is equally distributed with citizens’ input.

Distributive fairness concerns the allocation of resources and opportunities within a country (Schnaudt, Hahn, and Heppner Reference Schnaudt, Hahn and Heppner2021). Applying this concept, a distributive view of democracy prioritizes positive social and economic outcomes over adherence to a free and fair process. For example, researchers suggest that socioeconomic status affects regime support: those in higher socioeconomic positions tend to support the status quo, while those in lower positions often oppose it, even if the status quo is democratic (Ceka and Magalhães Reference Ceka and Magalhães2020). This pattern also appears in how perceived levels of economic inequality correlate with support for democracy in East Asia and Latin America (Wu and Chang Reference Wu and Chang2019). Whether individuals have their economic needs met influences their evaluation of democracy and affects whether they view a regime as democratically legitimate (Ceka and Magalhães Reference Ceka and Magalhães2020).

Chu, Williamson, and Yeung (Reference Chu, Williamson and Eddy2024) identify that some citizens have a “substantive” view of democracy, where democracy is conceptualized in terms of tangible outcomes like economic benefits. This idea of distributive democracy has been supported by other recent survey work. When Pew asked 30,000 people across 24 countries how democracy could be improved, addressing basic needs like jobs, rising prices, and livable wages emerged as a key theme (Silver et al. Reference Silver, Fagan, Huang, Clancy, Chavda, Baronavski and Mandapat2024). Moreover, this tension between procedural democratic principles and socioeconomic benefits underpins populist movements throughout Latin America, where maintaining democratic processes often necessitates addressing inequality (Saffon and González‐Bertomeu Reference Saffon and González‐Bertomeu2017). Citizens may value ensuring economic prosperity and quality public goods such as education and infrastructure over competitive elections.

Finally, the concept of liberal democracy addresses civil liberties, such as the protection of human rights. It is distinct from both democratic processes and the distribution of social and economic benefits. For this concept, we draw on work by Dahl (Reference Dahl1983), who incorporates liberal democracy into his concept of polyarchy when he details the right to freedom of expression, the right to seek out alternative sources of information, and the right to organize as necessary freedoms in a democracy. Liberal democracy emphasizes the critical need to safeguard individuals and minority groups from oppression, whether by government power or majority rule (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Hicken and Kroenig2011). This can be understood as a “negative” view of power—that is, liberal democracy represents protections, a “freedom from” discrimination and targeting.

These three dimensions of democracy are not mutually exclusive; it is possible to have democratic governance integrating all three dimensions. However, even if procedural democracy emphasizes including citizens in the democratic process, citizens may be willing to trade democratic principles for better distributive democracy if a regime fails to deliver favorable outcomes (Saffon and González‐Bertomeu Reference Saffon and González‐Bertomeu2017). To understand what prompts citizens to prioritize certain aspects of democracy above others, we employ a conjoint experiment that randomizes characteristics of these democratic categories and identify what individual-level characteristics correspond with these trade-offs.

The relationship between democratic performance and democratic principles also deserves careful examination, particularly the question of how economic outcomes might moderate citizens’ commitment to democratic values when faced with trade-offs (Saffon and González‐Bertomeu Reference Saffon and González‐Bertomeu2017). For instance, individuals are more likely to justify undemocratic actions from politicians when policies like healthcare and social spending align with their political interests (Krishnarajan Reference Krishnarajan2023), suggesting that some Americans consider democratic principles worth sacrificing for the sake of certain outcomes.

Building on this understanding, research shows that socioeconomic status further influences regime support: Ceka and Magalhães (Reference Ceka and Magalhães2020) argue that in democratic societies with widening income gaps, those in poverty are likely to be less committed to democracy than their well-off counterparts, indicating that economic well-being moderates attitudes toward democracy. Supporting evidence for this relationship extends globally: a 2021 Pew survey of 17 advanced economies—of which 16 were democracies—found that economic pessimists were more likely to desire significant political change (Wike and Fetterolf Reference Wike and Fetterolf2021). Taken together, these findings suggest that the distributive aspects of democracy, particularly economic well-being, may significantly condition individuals’ commitment to other procedural or liberal attributes of democracy against potential alternatives. Given this, we expect that preferences for normative levels of procedural and liberal democracy are highest when there is broad economic prosperity in which everyone’s needs are met, and housing and healthcare are affordable. In turn, preferences for normative levels of procedural and liberal democracy are lowest when people feel economically insecure and basic needs like housing and healthcare are economically challenging.

Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H1: individual preferences for normative levels of procedural and liberal democracy are contingent on the level of economic well-being provided by democracy.

Defining Democracy: Existing Work and Methods

Accurate measurement of citizens’ democratic preferences is important, because this influences whether they view democratic principles as fundamental or negotiable in exchange for preferred outcomes (Lu and Chu Reference Lu and Chu2021). However, though current projects like V-DEM can provide rich expert-level opinions, they cannot provide insights into “bottom-up” citizen-level support. Likewise, while large-scale surveys such as the World Values Survey, Eurobarometer, and other national barometers give us valuable breadth across nations, these datasets can only provide self-report information at the individual level.

For instance, Cho (Reference Cho2014) finds that individuals who understand liberal principles as core democratic elements are more likely to support liberal democratic governance. However, Cho’s study was limited to World Values Survey data, and the metric used to measure understanding of democracy evaluated whether participants defined democracy in terms of popular elections and civil liberties in contrast to a military takeover or a religious interpretation of the law. Understanding democracy in terms of popular elections and civil liberties is not incorrect but is also not comprehensive, as it does not leave room for distributive interpretations of democracy that can drive democratic satisfaction (Wike and Fetterolf Reference Wike and Fetterolf2021).

Additionally, the dependent variable for Cho’s study involved the explicit acceptance of democratic government compared with the rejection of authoritarian government. Acceptance of democracy as opposed to other systems of government does not isolate what individuals value about democracy; instead, it mainly quantifies relative dislike of authoritarian governance. Relying on self-reported understandings of democracy, therefore, does not necessarily reveal true preferences and predict what principles matter most to individuals.

This project diverges from previous studies by not attempting to assess the extent to which people hold a “correct” understanding of democracy. Democracy is a multifaceted concept that may vary both within and between nations according to sociocultural context (Davis, Goidel, and Zhao Reference Davis, Goidel and Zhao2021). Instead, we seek to introduce multiple conceptions to identify which are most preferred among the public. This helps us to draw out Americans’ tendencies to be principle holders or benefit seekers. Drawing on prior research and the three dimensions of democracy outlined above (Lu and Chu Reference Lu and Chu2021; Norris, Cameron, and Wynter Reference Norris, Cameron and Wynter2018), we break down democracy into four attributes: political equality, rule of law, freedom of expression, and economic well-being. These four attributes are manifestations of our three overarching understandings of democracy: political equality and rule of law represent the concept of procedural democracy, economic well-being represents the idea of distributive democracy, and freedom of expression represents liberal democracy.

These attributes of democracy improve upon past measures because they differentiate between democratic outcomes and processes. This is an important distinction because these conceptualizations of democracy are not inherently dependent on one another; each concept on its own is a necessary but individually insufficient condition for a democratic society. For instance, it is possible to have a nation that fairly votes in an illiberal candidate who does not value civil liberties or violates democratic norms, as seen in the 2018 presidential election in Brazil and the 2016 and 2024 presidential elections in the US.

To leverage individual-level data and evaluate citizens’ preferences for democracy, it is necessary to provide multiple conceptualizations of democracy and acquire individuals’ revealed preferences rather than their self-reported understanding of democracy. We address this open conceptual and methodological question of alignment between self-reported procedural, liberal, and distributive understandings of democracy and individuals’ revealed preferences for normative democratic governance by testing the following hypothesis in our study:

H2: the effect of democratic attributes on participant choice varies significantly by self-reported understanding of democracy.

Research Design

Our central motivating questions are as follows: What are the attributes of the “ideal” democracy in which Americans wish to live? Do distributive outcomes of democratic governance condition preferences for normative procedural and liberal democracy? And do American’s self-reported beliefs align with their revealed preferences when they are forced to make choices and trade-offs? To answer the first question, we use a question format commonly employed on cross-national surveys such as the World Values Survey (Haerpfer et al. Reference Haerpfer, Inglehart, Moreno, Welzel, Kizilova, Diez-Medrano, Pippa Norris and Puranen2022) and the European Social Survey (Ferrín Pereira, Hernández, and Landwehr Reference Ferrín Pereira, Hernández and Landwehr2023; Quaranta Reference Quaranta2018) that asks respondents about the importance of different attributes of democracy. We answer the second and third questions by leveraging a conjoint experiment conducted with the same national sample of participants. Employing a framework developed by Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto (Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014), we generated randomized country profiles with four attributes and three levels. These four attributes—political equality, rule of law, freedom of speech, and economic well-being—represent our three dimensions of democracy.

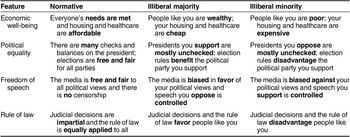

We also provide different levels of our four democratic attributes, which represent different situations for our respondents. Two of our levels are illiberal majority and illiberal minority in reference to Zakaria’s (Reference Zakaria1997) definition of illiberal democracy: systems with competitive elections that fail to protect civil liberties and minority rights while disregarding constitutional constraints on executive power. We chose these varying levels of each attribute because individuals’ perspectives on democracy can be skewed by their subjective experience of it (Burger and Eiselt Reference Burger and Eiselt2023; Lindholm and Rapeli Reference Lindholm and Rapeli2023; Lindholm, Lutz, and Green Reference Lindholm, Lutz and Eva2024). Drawing on the emerging literature on illiberalism and majoritarian understandings of democracy, we define a core dimension of illiberal democracy as electoral majoritarianism—the rejection of limitations and rights-based constraints on political power (e.g., Enyedi Reference Enyedi2024; Laruelle Reference Laruelle and Laruelle2024; Scheiring Reference Scheiring, Sajó, Uitz and Holmes2021; Wunsch, Jacob, and Derksen Reference Wunsch, Jacob and Derksen2025). Both illiberal levels for each attribute in our experiment reflect this conceptualization, as they violate the principles of equal treatment and minority protection but differ in the participants’ perspectives. Thus, by varying the relationship of participants to liberal and illiberal democracy in each country profile, our design induces their subjective experience, much like real-world elections, prompting them to weigh certain democratic attributes over others and to reveal whether they prioritize self-interest and political positionality over liberal democratic norms. This will allow us to determine whether some Americans are benefit seekers or principle holders (Lu and Chu Reference Lu and Chu2021).

Participants viewed two country profiles at a time and were asked to choose the country that represented their ideal version of democracy for five rounds. This structure allows complete randomization of our profiles. Table 1 provides all attributes and levels used. We measure participants’ revealed preferences on these dimensions through their choice of country profiles and measure their self-reported understanding of democracy via survey items asked after the conjoint experiment section. An example of possible country profiles is included in figure 1.

Table 1 Attributes and Levels Included in Conjoint Experiment

Figure 1 Example Profiles for Conjoint Experiment

Item Batteries

The individual-level covariates we include in this study focus on political attitudes and predispositions. Our covariate for understanding of democracy was asked in a ranked-choice question, which asked participants to order nine attributes they believed were most essential to democracy from one to nine. The nine items reflected our three theoretical conceptualizations of democracy outlined above, with three items per conceptualization. Procedural understanding of democracy was composed of the following items: (1) people choose government leaders in free and fair elections, (2) multiple parties compete fairly in elections, and (3) courts protect ordinary people from the abuse of government power. Distributive understanding of democracy was composed of the following items: (1) democracy narrows the gap between rich and poor, (2) basic necessities like food, clothes, and shelter are provided for all, and (3) democracy ensures job opportunities for all. Liberal understanding of democracy was composed of the following: (1) people are free to express their political views openly, (2) media is free to criticize the government, and (3) people have the freedom to take part in protests and demonstrations.

These items were then grouped into liberal, procedural, and distributive dimensions of democracy using the Thurstone Case V approach. This method, commonly applied to ranked-choice questions, involves collecting paired comparison judgments from subjects and then constructing a psychological scale based on the proportion of times each stimulus is judged to be greater than others (Jackson and Fleckenstein Reference Jackson and Fleckenstein1957; Krabbe Reference Krabbe2008). The approach transforms these proportions into z-scores (standard normal deviates) to establish interval-scale measurements and determine psychological distances between the items. We calculated Thurstone Case V scores with a function similar to the “thurstone()” function from the psych package (Revelle Reference Revelle2024). However, because our scale data included a high level of unanimous agreement, we capped infinite z-scores at ±4.0 and implemented Laplace smoothing to handle cases with extreme values.

Though the internal reliability of each dimension using Kendall’s W was weak to moderate (see table S3 in the supplementary materials), the root mean square error (RMSE) scores for all three dimensions indicated a high level of validity: the RMSEs for liberal, procedural, and distributive democracy were 0.0061, 0.0014, and 0.0047, respectively. In other words, the items loaded on our three latent conceptualizations of democracy as expected, but the measurement of these concepts was less reliable across respondents—consistent with previous survey research reporting uneven measurement of self-reported understandings of democracy (Quaranta Reference Quaranta2018). However, even within the same nation, conceptualizations of democracy can be broad and complex (Ariely and Davidov Reference Ariely and Davidov2011; Davis, Goidel, and Zhao Reference Davis, Goidel and Zhao2021; Osterberg-Kaufmann, Stark, and Mohamad-Klotzbach Reference Osterberg-Kaufmann, Stark and Mohamad-Klotzbach2020), and we interpret the low agreement as evidence that citizens do not hold uniformly structured or tightly integrated conceptions of democracy—a key finding. This limitation of self-report measures serves as motivation to use a conjoint experiment to capture revealed preferences rather than rely on self-reports. Thurstone Case V scale scores for all items are included in table S4 in the supplementary materials.

Finally, participants were asked their gender (male, female, neither, or both) age, level of education attainment (from some high school or less [one] to graduate degree [six]), their race, and their political ideology. Wording for these items is included in table S1, descriptive statistics for these items are included in table S2, and reliability and validity scores for our dimensions of democracy are reported in table S3 in the supplementary materials.

Case Selection, Samples, and Implementation

The sample for this project consists of 623 participants, drawn from an opt-in online panel in August 2024. Quota sampling was employed to ensure the sample was comparable to the US population on race, age, gender, and educational attainment. We chose a US sample because it presented a unique case study of a society with an increasing income gap (Muczyk, Nance, and Coccari Reference Muczyk, Nance and Coccari2009) and a national election in 2024. The existing political tension and economic climate during this period in the US gave us a salient test of whether individuals in an established democracy remain principle holders in unfavorable conditions or switch to being benefit seekers.

Revealed Preferences for Attributes of Democracy

Analysis Strategy

To analyze individuals’ revealed preferences for democracy, we started with a frequentist (as opposed to Bayesian) analysis of our conjoint data using marginal means and conditional marginal means based on the recommendation of Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley (Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020). A frequentist approach treats probabilities as long-run frequencies of events in repeated experiments, while a Bayesian approach treats probabilities as degrees of belief that can be updated with new evidence. In this experiment we use both approaches to answer different questions.

In our power analysis, we found that with 623 respondents, five tasks, three levels for our attributes, and looking for a 0.05 effect size, we had 92% power, which was sufficient for looking at our main effects and conditional marginal means. However, to conduct our post hoc exploratory analyses and investigate heterogeneity in our data, we used the cjbart model (Robinson and Duch Reference Robinson and Duch2024). Conceptually, cjbart goes one step beyond traditional conjoint analyses—which focus on average marginal component effects—and estimates individual-level effects with a Bayesian approach, as well as identifying which respondent characteristics drive differences in conjoint treatment effects.

In more technical terms, cjbart uses Bayesian additive regression trees (BART) and machine learning to leverage the full conjoint experiment dataset and create a model that estimates the relationship between the forced-choice outcome, the conjoint experiment levels and attributes, and the subject-level covariates, capturing heterogeneous relationships. We chose to use the cjbart model to model our individual-level heterogeneity because it captures more detailed relationships in the data than average marginal component effect analyses, allowing us to explore individual marginal component effects with a smaller sample size and investigate nonlinear relationships in the data (Robinson and Duch Reference Robinson and Duch2024).Footnote 1

Using the cjbart package, we aggregate the observation-level marginal component effects from each round to get the individual marginal component effects (IMCEs), which indicate how each participant valued each attribute when selecting a country profile as an ideal democracy. Unlike average marginal component effects, IMCEs consider the impact of individual-level attributes on profile choice. Since our estimation strategy is Bayesian, we use a credible interval approach to address uncertainty estimation. This is done with posterior samples drawn with Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling.

Bayesian methods treat parameters as having probability distributions rather than fixed values, allowing direct quantification of uncertainty for estimates. Instead of traditional confidence intervals, we get credible intervals that have intuitive interpretations: a 95% credible interval means there is a 95% probability the true parameter falls within that range. Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling is a computational technique that draws thousands of plausible parameter values from this probability distribution when the math is too complex to solve directly. These posterior samples let us easily calculate credible intervals and propagate uncertainty through complex models.

Our cjbart model involved five hundred trees and took ten thousand draws from the posterior distribution. To verify model convergence and mixing quality, we used Geweke’s convergence diagnostic and found a z-score of 0.95, which is well below the threshold of 1.96 for 95% confidence. The model therefore demonstrated adequate convergence, and the output shows good mixing (see figure S1 in the supplementary materials). Replication data for our analysis is available in Harvard Dataverse (Mortenson and Nisbet Reference Mortenson and Nisbet2025).

Results

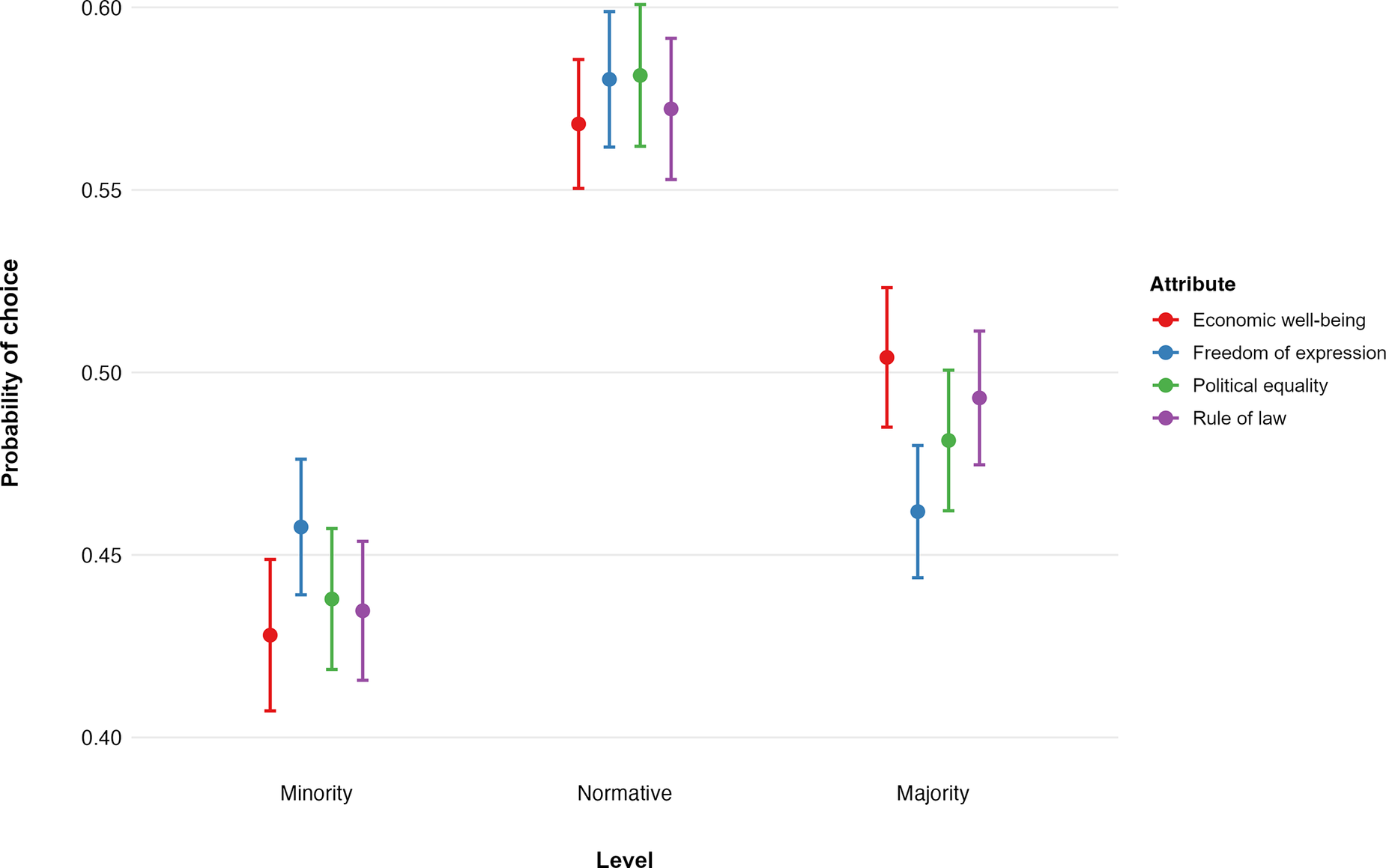

The main effects of the conjoint experiment show sizable differences in preferences between the normative condition of our democratic attributes versus the minority and majority levels. Figure 2 shows marginal means that indicate that on average, the normative condition of all attributes of democracy are preferred, the next most favorable condition is the majority condition, and the least favorable condition is the minority condition. Overall importance scores for each attribute are included in the supplementary materials (figure S2).

Figure 2 Marginal Means for Attributes of Democracy

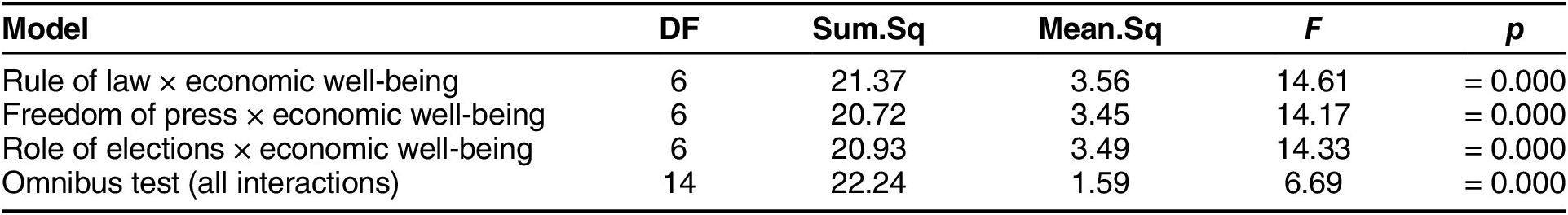

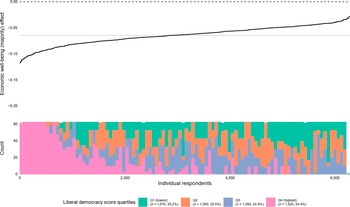

However, though the normative profile is preferred on average across attributes, we predicted that preferences toward democratic profile choice would be conditioned based on economic well-being. We conducted an F-test for each attribute of democracy contrasted with level of economic well-being. Our results, shown in table 2, indicate that preferences for political equality, rule of law, and freedom of expression significantly vary based on the level of economic well-being (p = 0.000). This implies that the value that Americans place on different attributes of democracy is not zero sum; instead, attributes of democracy are evaluated relative to one another. Specifically, economic circumstances introduce variance in how Americans evaluate other attributes of democracy.

Table 2 Nested Model Comparisons Testing Economic Well-Being Interaction Effects

Note: DF = degrees of freedom; Sum.Sq = sum of squares; Mean.Sq = mean square. All models compare restricted (main effects only) models to unrestricted (with interaction) models.

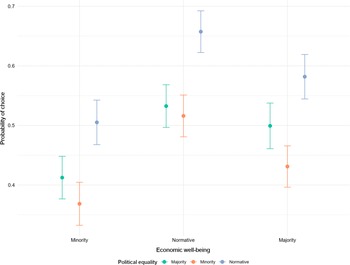

The direction of this pattern is confirmed when comparing conditional marginal means in figure 3. We find that normative rule of law is the most preferred condition, but that the strength of rule of law on the probability of choosing a country profile varies based on the level of economic well-being. For instance, under normative economic conditions, all three rule-of-law categories show probabilities above 0.50 for country choice. However, in minority economic conditions, the probabilities for country choice remain below 0.55 for all rule-of-law levels. This decline in support for equal treatment under the law in minority economic conditions provides support for H1, reinforcing our argument that commitments to liberal democratic principles are contingent on material well-being.

Figure 3 Marginal Means: Rule of Law Compared by Level of Economic Well-Being

A similar relationship is shown in figures 4 and 5. The normative condition of political equality and freedom of expression are preferred overall. However, the probability of a profile being chosen is higher for all three levels of political equality when economic well-being is normative, and significantly lower when economic well-being is in the minority condition. Similarly, when economic well-being is normative, all three levels of freedom of expression are more likely to lead to profile choice than when economic well-being is in the minority condition. The reduced likelihood of supporting the normative condition of political equality and freedom of expression when economic conditions are unfavorable further reinforces H1, supporting our argument that economic well-being plays a role in whether citizens decide to be principle holders or benefit seekers. Though we cannot statistically demonstrate which of our democratic attributes are moderating the other, we consistently see a similar pattern of variation among levels of economic well-being across all the different attributes of democracy, consistent with our hypothesis.

Figure 4 Marginal Means: Role of Political Equality Compared by Level of Economic Well-Being

Figure 5 Marginal Means: Freedom of Expression Compared by Level of Economic Well-Being

Post Hoc Heterogeneity Analysis

Next, we calculated IMCEs using the “IMCE” function in the cjbart package and used these scores to understand individual-level variance in revealed preference for democracy. Compared with average marginal component effect, which shows the average preference for an attribute over the whole sample (see figure S3 in the supplementary materials), the IMCEs show each participant’s score for both the majority and minority conditions of an attribute compared with the normative. Like the marginal means (see figure 2), individual participants tend to prefer the normative condition of all democratic attributes compared with the majority condition and minority condition (see figure 6). This is as expected, given that the average for the sample should reflect individual preferences. Interestingly, while the majority and minority conditions significantly overlap for other attributes of democracy, economic well-being has a more bimodal distribution that shows significant preference for the majority over the minority at the individual level, despite overall preference for the normative. This pattern bolsters our argument of latent heterogeneity in commitment to democracy, indicating that there are distinct subgroups in the population—those who favor distributive outcomes more consistently and those who do not—illustrating that democratic preferences are not uniform but contingent on economic self-interest.

Figure 6 Revealed Preferences for Democracy: Individual Marginal Component Effect

Note: Normative is the reference group.

To examine how IMCEs vary by individual characteristics and assess potential heterogeneity (figure 6), we used the “variable importance” (VIMP) function in the cjbart package to estimate importance scores and calculate interactions for our covariates. We focus on selected individual characteristics—self-reported measures of understanding of democracy, as well as demographic factors such as age, education, ideology, and political interest—that may condition the impact of democracy attributes on preferences. These importance scores, ranging from zero (lightest shade) to one hundred (darkest shade), are visualized in the heatmap in figure 7. A high importance score indicates substantial heterogeneity in IMCEs based on variance in the given characteristic, whereas a low importance score suggests minimal heterogeneity. To guide our analysis, we focus on variables that account for at least one-half of the model’s total variance, as well as those exceeding half of the maximum possible importance in the model. Based on this criterion, we classify importance scores at or above 50 as highly important, forming the basis for further examination.

Figure 7 Importance Score Interaction Heatmap

Our analysis shows that the relationships between the democracy attributes in the conjoint experiment and overall country preferences do not align with their corresponding self-reported measures, failing to support H2. In fact, age and education are more important variables for explaining heterogeneity in freedom of expression, political equality, and rule of law than self-reported prioritization of these democratic dimensions. The weak association between self-reported understandings of democracy and revealed preferences suggests that such beliefs do not drive political behavior, reinforcing our finding that Americans, under certain conditions, are willing to trade liberal democratic principles for material benefits.

There was spillover, however, between high scores on liberal democracy and preference for economic equality over being wealthy, as the exploratory post hoc results in figure 7 show that the impact of economic well-being on country choice varies substantially based on the priority that respondents place on the liberal dimension of democracy.Footnote 2 This suggests that there is a subset of extreme liberal democrats who integrate their self-reported preference for civil liberties in democracy into their revealed preferences for levels of economic well-being.

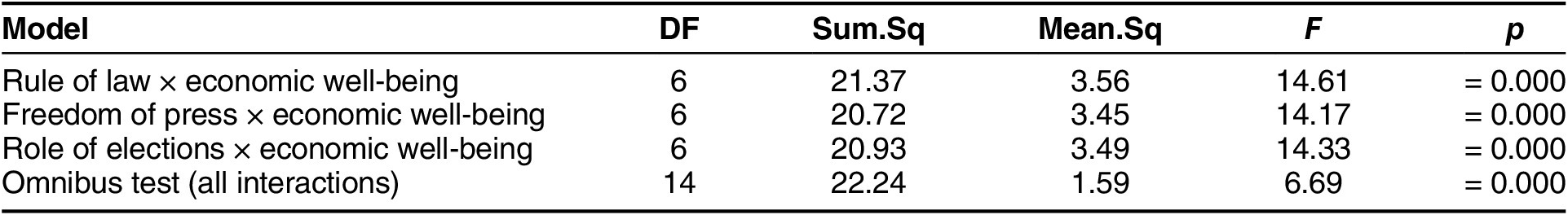

The relationship between liberal democracy and economic well-being, graphed in figures 8 and 9, reveals an interesting pattern. In figure 8, individuals who score in the highest quartile for liberal democracy show distinctly different preferences compared with those in other quartiles. Rather than favoring the condition where they are wealthy, these strong liberal democracy supporters prefer an economic system where everyone’s needs are met, indicating that they prioritize equality over personal wealth. However, these same individuals also accept the minority condition of economic well-being, preferring that individuals like them are poor.

Figure 8 Relationship between Liberal Democracy Score and Economic Well-Being (Majority)

Note: Normative economic well-being is the reference group.

Figure 9 Relationship between Liberal Democracy Score and Economic Well-Being (Minority)

Note: Normative economic well-being is the reference group.

These exploratory findings are consistent with the scholarship on inequality aversion (Fehr and Schmidt Reference Fehr and Schmidt1999) and moral identity centrality (Aquino and Reed Reference Aquino and Reed2002), which demonstrate that individuals sacrifice personal gain to uphold deeply held values or beliefs. They are also consistent with research on moral conviction (Brandt, Wisneski, and Skitka Reference Brandt, Wisneski and Skitka2015), showing that when equality is deeply moralized, people may willingly accept personal hardship to affirm their principles. The implications are that for those who prioritize liberal democracy, their egalitarian understanding of democracy is deeply intertwined with their beliefs about economic fairness and equality.

To test whether the impact of age and education on our IMCEs was an artifact of which variables were included in the VIMP analysis, we tested another set of controls without the self-report preference for democracy measures and included race. We find that age and education both remain a substantial source of heterogeneity in the data and influence revealed preferences about democracy even when race is included (results are included in figure S4 in the supplementary materials).

Discussion

The presidential results from the 2024 national election highlight a crucial disconnect in American political discourse. Although the Democratic Party argued that democracy was on the ballot, NBC’s 2024 exit poll showed that Donald Trump won most voters who believed “democracy was threatened” by five percentage points (47% versus 52%) (NBC News 2024). Our experimental results provide insights into why such political framing about democracy being under threat proved ineffective against a presidential candidate widely criticized for violating democratic norms. Employing a conjoint experiment, our study provides empirical evidence to advance the theoretical debate about democratic preferences. This methodological approach not only addresses critiques of traditional survey instruments but also reveals how Americans understand democracy: namely, that preferences toward democracy are contextual rather than one dimensional.

Our analysis reveals a complex relationship between democratic attributes. Though respondents appeared to be principle holders with an average preference for normative democratic ideals across all attributes (political equality, rule of law, freedom of expression, and economic well-being), this changes when average preference for the sample is broken down based on the levels of economic well-being. Our marginal means indicate that one’s economic status significantly moderates revealed preferences toward democracy. When profiles featured normative levels of economic well-being, respondents were more likely to accept the normative level for rule of law, political equality, or freedom of expression. However, if economic well-being was in the minority condition, support for the normative condition for political equality, rule of law, and freedom of expression was less likely. This suggests the level of economic well-being has a role in whether Americans choose to be principle holders or benefit seekers when forced to make a choice. We see this reflected in prior work, where Americans were more likely to excuse undemocratic behavior from candidates to gain preferred policy outcomes (Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik2020). Our study extends this work to show that economic conditions not only influence Americans’ policy and candidate preferences, but also their preferences for the type of “democracy” in which they wish to reside.

Rather than evaluating democratic attributes in isolation through a zero-sum framework, the evidence suggests these attributes function as interdependent components, where their relative significance emerges from their collective interaction. This highlights the complex factors that influence whether citizens remain principle holders or become benefit seekers. Our findings challenge the notion that democracy exists as an isolated political concern for American voters. Instead, the way Americans value democratic principles appears to be fundamentally intertwined with their economic well-being, suggesting that “democracy on the ballot” appeals to counter illiberal political candidates may miss how voters experience and evaluate democratic governance.

The importance of economic conditions in shaping political preferences is well established. In American politics, the public has consistently judged incumbent candidates based on economic performance (Guntermann, Lenz, and Myers Reference Guntermann, Lenz and Myers2021), making it a decisive factor in electoral outcomes (Vavreck Reference Vavreck2009). Indeed, Vavreck (Reference Vavreck2009) notes that candidates who campaign without emphasizing the economy often face an uphill battle, as demonstrated in Vice-President Kamala Harris’s 2024 presidential campaign.

While the Biden and Harris campaigns highlighted declining overall inflation ahead of the 2024 presidential election, American families continued to face rising grocery costs. Food prices climbed between November 2023 and November 2024, standing 2.4% higher than the previous year (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2024). These seemingly modest percentage increases can have a profound impact on middle-class households’ daily budgets. Unlike abstract democratic principles such as freedom of expression and the rule of law—however vital they may be—the cost of feeding one’s family is an immediate, tangible reality that Americans confront every time they walk into a grocery store.

Economic shocks and stressors can increase norm violations at the individual level (Bogliacino et al. Reference Bogliacino, Charris, Gómez and Montealegre2024), mirroring our finding that economic well-being moderates support for other democratic norms. At the macro level, cross-national evidence indicates that economic inequality is a powerful predictor of democratic erosion—even in wealthy, long-standing democracies (Rau and Stokes Reference Rau and Stokes2025). This implies two concerning developments. First, appeals to liberal democratic norms can prove ineffective during periods of economic uncertainty, when citizens prioritize material security over procedural integrity. Second, even established democracies are not immune to the gradual erosion of foundational principles when economic stress persists. Relatedly, recent experimental work suggests that in countries with more democratic experience, voters may be less likely to punish incumbents who behave undemocratically (Frederiksen Reference Frederiksen2022).

Although political identity could plausibly influence the relationship between economic uncertainty and democratic norms, our heterogeneity analysis in figure 7 indicates that ideology is not the main driver. Future research should examine whether this conditionality in democratic support holds across other established democracies during episodes of economic stress, and whether different institutional designs or communication strategies can buffer democratic norms against such pressures.

Another striking finding is the divergence between participants’ self-reported understandings of democracy and their revealed preferences, casting doubt on traditional survey methodologies. When asked directly about essential democratic features, participants endorsed traditional, procedural, and liberal ideas of democracy. However, these stated preferences did not correspond with their revealed preferences. For example, participants who self-reported strong preferences for liberal democracy also demonstrated revealed preferences favoring normative economic well-being, suggesting an overlap between these value systems. Notably, participants scoring in the top 25% for liberal democracy were more likely to reject the majority condition regarding economic well-being and prioritize overall economic equality instead, and did not reject being poor themselves. We suggest that individuals who identify as advocates for civil liberties may naturally extend these values to embrace economic equality in areas like healthcare and housing.

The relationship between economic well-being and civil liberties can be seen in populist progressive policy. In 2020 Bernie Sanders ran on a “21st Century Economic Bill of Rights” platform, arguing that regardless of their income level, Americans should be entitled to a job that pays a living wage, to quality healthcare, and to affordable housing. Historically, Sanders has also championed civil liberties. For instance, he introduced a resolution to protect students’ free speech on college campuses (Sanders Reference Sanders2024) and supports the free press (Sanders Reference Sanders2020; Reference Sanders2022). However, we can also see the linking of freedom of speech and economic well-being on the populist Right. President Trump ran on a platform in 2024 that pledged he would “make America affordable again,” reduce inflation, and protect First Amendment rights (Trump Reference Trump2024). Populists on both ends of the political spectrum may therefore associate civil liberties with economic equality.

The overall gap between stated beliefs and revealed preferences challenges the validity of conventional survey measures of democratic attitudes. We see incongruence between support for democracy and undemocratic action in prior work as well: though there is strong evidence for global support for democracy, there is also growing support for alternative styles of government (Wuttke, Gavras, and Schoen Reference Wuttke, Gavras and Schoen2022), and in polarized nations voters are willing to trade off democratic principles for partisan interests (Svolik Reference Svolik2018). Rather than reflecting voters’ actual priorities, survey responses about support for democracy may instead capture socially desirable answers that do not align with real-world decision making.

A conjoint experiment approach offers several advantages for studying democratic attitudes and can be extended to comparative work beyond the US (Christensen and Saikkonen Reference Christensen and Inga2025; Hedegaard and Larsen Reference Hedegaard and Larsen2023; Papp et al. Reference Papp, Navarro, Russo and Nagy2024; Saikkonen and Christensen Reference Saikkonen and Christensen2023). Using a conjoint experiment in Finland, Saikkonen and Christensen (Reference Saikkonen and Christensen2023) find that certain subgroups of the population are willing to excuse undemocratic behavior if they gain political benefits. The same authors leverage another conjoint experiment and find that Finnish citizens are willing to choose issue positions over liberal democratic principles, consistent with our results (Christensen and Saikkonen Reference Christensen and Inga2025). The conjoint design, combined with BART analysis, allows us to move beyond traditional survey limitations to examine how citizens navigate trade-offs between different aspects of democracy. This advances existing theoretical frameworks by demonstrating that political equality, rule of law, and freedom of expression are not evaluated independently, but rather through complex interactions shaped by economic circumstances. Our second hypothesis speculated that self-reported understanding of democracy would explain some variance for revealed preferences, but the relationship between economic conditions and democratic values proved more nuanced than initially theorized. These results contribute to ongoing debates about measuring democratic support by suggesting that current survey-based approaches may not fully capture how citizens conceptualize and value democracy in practice.

For future research focused on support for democratic government, these findings suggest attitudes toward both processes and outcomes of democracy should be included as indicators of democratic support. Additionally, when evaluating public support for democracy, narrow definitions of democracy should be avoided since they often measure different constructs and citizens often hold contradictory views (Ariely and Davidov Reference Ariely and Davidov2011; Schedler and Sarsfield Reference Schedler and Sarsfield2007). Providing more direct comparisons between several democratic attributes allows us to understand participants’ revealed preferences toward democracy, which are often contextual, rather than their self-reported attitudes, which can be influenced by social desirability toward democracy (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2003).

Overall, our research demonstrates that democracy operates through a sophisticated interplay of processes, outcomes, and protections. While scholarly discourse often focuses on electoral systems and civil liberties, regime performance significantly shapes how Americans value democratic principles. Specifically, economic well-being—a key factor in democratic outcomes—conditions support for fundamental democratic norms like political equality, rule of law, and freedom of expression. As populist movements gain momentum and illiberal leaders are elected to office, understanding the role of democratic outcomes in maintaining support for democratic governance becomes increasingly important. This study’s results underscore that democratic outcomes cannot be separated from democratic processes. While individuals may idealize normative democracy, this vision often conflicts with material concerns and their lived experience of democracy. Consequently, within the context of understanding the political psychology of political backsliding (e.g., Druckman Reference Druckman2024), we need to more deeply examine the relationship between antidemocratic attitudes and adverse democratic outcomes.

Limitations and Generalizability

For this study we combined Bayesian and frequentist analysis strategies. Our main effects and attribute interactions derive from experimental data, but importance measures were generated using cjbart’s trained models to predict distributions across all possible conjoint profiles. The cjbart package employs robust Bayesian statistics and machine learning, allowing us to more accurately capture heterogeneity. However, despite the robustness of the analyses, the study had some constraints. For instance, we rely on cjbart’s model assumptions and accept its limitations. Though the cjbart model can handle any number of covariates with its use of Bayesian methods and machine learning, the VIMP process requires more traditional frequentist power analyses and therefore reduced our power for the importance heatmap. Additionally, IMCEs in this project shown in the importance heatmap and subsequent graphs demonstrate correlational relationships and descriptive patterns but are unable to prove causality.

Furthermore, though our self-report measures for liberal (RMSE = 0.0061), procedural (RMSE = 0.0014), and distributive democracy (RMSE = 0.0047) had good fit, our measures had weak internal consistency. Kendall’s W for all three measures was below 0.3873 (see table S3 in the supplementary materials), indicating a weak to moderate level of reliability. This presents a constraint for our analyses but also reinforces the fact that self-report measures are often insufficient for measuring abstract concepts like understandings of, or preferences for, democracy. We believe this is consistent with prior research highlighting the conceptual ambiguity and multidimensional nature of public understandings of democracy (e.g., Ariely and Davidov Reference Ariely and Davidov2011; Davis, Goidel, and Zhao Reference Davis, Goidel and Zhao2021; Quaranta Reference Quaranta2018). We interpret the low agreement as evidence that citizens do not hold uniformly structured or tightly integrated conceptions of democracy, and thus treat it as a key finding rather than as only a limitation.

Additionally, for our conjoint experiment we provided four conceptualizations of democracy for our participants to weigh. However, there are other attributes of democracy beyond political equality, rule of law, freedom of expression, and economic well-being that our participants may consider when deciding to be principle holders or benefit seekers. For instance, they may consider separation of powers to be distinct from political equality or rule of law, or may value concepts associated with deliberative democracy. Likewise, future research should consider aspects of distributive democracy other than the economy, such as education and job opportunities.

Moreover, we cannot generalize our results to past or future events given that our data are cross-sectional. Since our data were collected three months before a polarizing national election in the US, it is possible that the idea of democracy was more salient than in other years. We also encourage future research extending to both democratic and nondemocratic contexts, since individuals from other established democracies and different regime types likely experience democracy differently than Americans (Lu and Chu Reference Lu and Chu2021; Zagrebina Reference Zagrebina2020). However, our study’s approach and outcomes still offer a framework for similar investigations in other political settings. Our results suggest that there is a disconnect between self-reported understanding of democracy and revealed preferences for democratic government, which should be considered for nations beyond the US.

Our statistical analysis cannot conclusively determine the directionality of the moderation observed in our results. However, our findings align with our theoretical framework, suggesting that economic well-being is the most likely moderating variable. Prior research has shown that socioeconomic status influences the strength of individuals’ commitment to democratic principles (Ceka and Magalhães Reference Ceka and Magalhães2020). The variance pattern for economic well-being remains consistent when interacted separately with each democratic attribute. Additionally, economic circumstances—and by extension, economic well-being—tend to exhibit greater variance (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2025) than political equality, rule of law, and freedom of expression, which generally shift with election cycles, at least within the US. This aligns with historical patterns showing that incumbent candidates’ success fluctuates with the state of the US economy during election years (Guntermann, Lenz, and Myers Reference Guntermann, Lenz and Myers2021), reinforcing the idea that economic well-being is a consistent and influential factor in Americans’ political preferences and priorities.

Furthermore, the wording of the levels in our conjoint experiment differs from most designs in that we purposefully invoke the participant’s identity as part of the group involved in the profiles. Diverging from prior work, we sought to mitigate the potential influence of social desirability in our conjoint experiment by framing attribute levels to evoke respondents’ subjective experiences—much like real-world electoral events. This design more realistically simulates how individuals weigh normative democratic principles against potential economic or political benefits for their own group.

At the same time, we acknowledge that this approach may introduce some degree of social desirability bias, as respondents may hesitate to select profiles that appear self-serving or illiberal. We believe this bias would work against our findings. Social desirability would likely inflate support for normative democratic principles and suppress the selection of illiberal or self-interested profiles, making it less likely that respondents would appear willing to trade procedural or liberal democracy for distributive gains. The fact that we still observe meaningful variation in revealed preferences, especially the decline in support for political equality, rule of law, and freedom of expression under economic insecurity, suggests that our results are conservative estimates. In short, the true extent of benefit-seeking behavior may be greater than what we find here. Finally, though our analysis primarily focuses on the US, supporting evidence for the relationship between economic well-being and democratic preferences extends globally. For instance, a 2024 conjoint experiment across France, Hungary, and Italy found that respondents identify good economic performance as an important feature of a well-performing democracy. Critically, the authors note that the state of the economy had the largest impact on satisfaction with democracy across all three nations (Papp et al. Reference Papp, Navarro, Russo and Nagy2024).

This connection between economic well-being and democratic preference also manifests in recent studies on democratic backsliding. Rau and Stokes (Reference Rau and Stokes2025) find that cross-nationally, economic inequality is one of the strongest predictors of where and when democracy erodes. The prioritization of outcomes over democratic principles enables illiberal leaders to frame themselves as democratic by emphasizing their advancement of social and economic conditions (Chu, Williamson, and Yeung Reference Chu, Williamson and Eddy2024). In conjunction, individuals often rationalize undemocratic behavior from politicians when it serves policies they support (Krishnarajan Reference Krishnarajan2023; Saikkonen and Christensen Reference Saikkonen and Christensen2023). Taken together, these findings suggest that the distributive aspects of democracy, particularly economic well-being, may significantly condition individuals’ commitment to other procedural or liberal attributes of democracy against potential alternatives. Without considering how a nation distributes economic opportunities and social welfare—key decision factors for citizens—we are unable to capture the full scope of democratic support in a nation.

Conclusion

This study contributes to ongoing debates about democratic beliefs and attitudes by demonstrating that Americans’ support for democratic principles is context dependent and moderated by economic well-being. While participants generally favored normative democratic ideals such as political equality, rule of law, and freedom of expression, these preferences weakened when respondents were presented with scenarios in which people like them experienced economic hardship. These findings challenge the idea that democratic principles are universally held across contexts, revealing instead that support for democracy is conditional and often shaped by lived material realities. In particular, the results suggest that appeals to abstract democratic values—such as “Democracy is on the ballot”—may be ineffective when voters face tangible economic stressors.

Our findings also underscore a disconnect between self-reported understandings of democracy and revealed preferences. Participants who claimed strong support for liberal democracy often prioritized economic equality when forced to make trade-offs, indicating that citizens’ conceptions of democracy may implicitly include distributive dimensions even when they do not explicitly endorse them. As Americans navigate an increasingly polarized political landscape, their support for democracy appears to operate through an interplay of normative ideals and material outcomes. Understanding this dynamic is essential for diagnosing the challenges facing democratic stability and for creating more resonant democratic appeals. Future work should continue to explore how economic experiences shape democratic commitments, particularly in contexts marked by inequality, polarization, and institutional distrust.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592725104052.

Data replication

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YPNPMA.