Background

Exoplanetary research has discovered several Earth-like planets in our galaxy (Carré et al., Reference Carré, Zaccai, Delfosse, Girard and Franzetti2022). This has increased our awareness on the possibility of potential habitable bodies beyond the Solar System and in the identification of several environments that could be locally conducive to the origin and evolution of life (Malaterre et al., Reference Malaterre, Ten Kate, Baqué, Debaille, Grenfell, Javaux, Khawaja, Klenner, Lara, McMahon and Moore2023). Mars still remains one of the primary astrobiological targets to date (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Merrison, Nørnberg, Lomstein and Finster2005) and certain terrestrial areas, known as “Martian analogues on Earth” (Cary et al., Reference Cary, McDonald, Barrett and Cowan2010), are characterised by such extreme environmental conditions (Rothschild and Mancinelli, Reference Rothschild and Mancinelli2001) that they are referred to as “Planetary Field Analogues” (PFAs) (Cassaro et al., Reference Cassaro, Pacelli, Aureli, Catanzaro, Leo and Onofri2021). Most of these were previously thought to be uninhabitable, but recent progresses have contrarily shown that life could exist there albeit in a limited way (Yin et al., Reference Yin, Wang, Liu and He2019). This redefines these environments as ‘habitable’ and offers new perspectives in developing strategies for astrobiological research (Cockell, Reference Cockell2014; Reference Cockell2021; Raulin-Cerceau, Reference Raulin-Cerceau2004). Under this perspective, some extremophilic and extremotolerant organisms are a key focus in the search for life on other planets (Merino et al., Reference Merino, Aronson, Bojanova, Feyhl-Buska, Wong, Zhang and Giovannelli2019). Among these, endolithic microorganisms inhabiting the interiors of rocks display exceptional adaptation capacity to exploit the ice-free areas of Continental Antarctica (Friedmann et al., Reference Friedmann1982, Reference Friedmann1986; Selbmann et al., Reference Selbmann, Isola, Egidi, Zucconi, Gueidan, De Hoog and Onofri2014; Stoppiello et al., Reference Stoppiello, Muggia, De Carolis, Coleine and Selbmann2025), accounted as one of the closest Mars-like environments on Earth (Cassaro et al., Reference Cassaro, Pacelli, Aureli, Catanzaro, Leo and Onofri2021; Scalzi et al., Reference Scalzi, Selbmann, Zucconi, Rabbow, Horneck, Albertano and Onofri2012). They are almost the only life-forms able to survive in these harsh environments (de Los Ríos et al. Reference De Los Ríos, Wierzchos and Ascaso2014), finding refuge in the endolithic niche (Aureli et al., Reference Aureli, Pacelli, Cassaro, Fujimori, Moeller and Onofri2020). In sedimentary and translucent rocks, such as sandstone, they inhabit the airspaces among the quartzite grains (Nienow, Reference Nienow1993), forming cryptoendolithic communities (de la Torre et al., Reference de la Torre, Goebel, Friedmann and Pace2003; Ruisi et al., Reference Ruisi, Barreca, Selbmann, Zucconi and Onofri2007; Meslier and DiRuggiero, Reference Meslier and DiRuggiero2019). The most widespread and complex in these areas are the lichen-dominated ones, forming a typical stratification of different coloured, biologically distinct bands within 1 cm below the rock surface (Figure 1) (Friedmann and Ocampo, Reference Friedmann and Ocampo1976; Friedmann et al., Reference Friedmann1982). The microorganisms in these communities display remarkable resistance: for example, the black fungus Cryomyces antarcticus survived exposure to space and Mars conditions for 18 months (Onofri et al., Reference Onofri, Pacelli, Selbmann and Zucconi2020), maintaining its DNA integrity (Pacelli et al., Reference Pacelli, Selbmann, Zucconi, Coleine, de Vera, Rabbow, Böttger, Dadachova and Onofri2019), cellular stability and ability to recover metabolic activity (Onofri et al., Reference Onofri, Pacelli, Selbmann and Zucconi2020). The rock itself not only protects microorganisms from the extreme environmental conditions but also provides them with the necessary mineral nutrients (Sajjad et al., Reference Sajjad, Ilahi, Kang, Bahadur, Zada and Iqbal2022).

Figure 1. Antarctic cryptoendolithic community colonising sandstones collected in Linnaeus Terrace by Laura Selbmann during the XXXI Italian Antarctic expedition (PNRA, 2015–2016) showing the typical stratification: (a) crust, (b) black fungi layer, (c) lichenised and non-lichenised algae and (d) red accumulation zone.

The environmental conditions in the ice-free areas of Continental Antarctica are very similar to those described on early Mars (Preston and Dartnell, Reference Preston and Dartnell2014). This makes these niches an optimal astrobiological model for understanding the characteristics and adaptations of putative Martian life (Martins et al., Reference Martins, Cottin, Kotler, Carrasco, Cockell, de la Torre Noetzel, Demets, de Vera, d’Hendecourt, Ehrenfreund and Elsaesser2017). Microbial life in the harsh conditions of this cold, dry desert could also provide new insights into the possibility of past or present life on Mars (Ascaso and Wierzchos, Reference Ascaso and Wierzchos2002). In fact, if life ever evolved on Mars, it may have adopted similar strategies, seeking refuge in Martian rocks before becoming extinct during the planet’s cooling and drying processes (Selbmann et al., Reference Selbmann, De Hoog, Mazzaglia, Friedmann and Onofri2005).

In this context, the CRYPTOMARS project aims to outline the bulk of characteristics that a putative microbial community would need to survive present or past Mars conditions (Selbmann et al., Reference Selbmann, Del Franco, Stoppiello, Ripa, Lopes, Donati, Franceschi, Garcia-Aloy, Cemmi, Di Sarcina and Bazzano2025).

On behalf of this project, this pilot study aimed at establishing effective, rapid and comparable experimental approaches to detect the viability of the cryptoendolithic communities after treatment with extreme stresses.

A rapid polyphasic method was adopted to study all community components simultaneously, including both eukaryotic and prokaryotic elements. The following methodologies have been chosen: i) the propidium monoazide (PMA)-qPCR coupled assay, to verify the presence of LIVE/DEAD cells depending on membrane integrity; PMA is a photoreactive compound unable to penetrate cells with intact membranes. When exposed to light, it intercalates and binds DNA of damaged cells preventing its amplification in subsequent qPCR (Chiang et al., Reference Chiang, Lee, Medriano, Li and Bae2022). This approach has been successfully applied for assessing viability in soil samples (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Ye, Jia, Fan, Hashmi and Shen2020; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Li, Xie, Chai, Shi, Fan, Xie and Li2022) and on Antarctic fungal colonies exposed to space conditions (Pacelli et al., Reference Pacelli, Selbmann, Zucconi, De Vera, Rabbow, Horneck, de la Torre and Onofri2017), allowing also to target specific microbial compartments; moreover, the approach consents to avoid overestimation of microbial presence due to the relic DNA (Carini et al., Reference Carini, Marsden, Leff, Morgan, Strickland and Fierer2016). ii) the Fluorescein diacetate assay (FDA) allows the detection of cell metabolic activity and is based on the determination of the hydrolysis reaction, due to cellular esterases, converting fluorescein diacetate to fluorescein (Schnürer and Rosswall, Reference Schnürer and Rosswall1982; Dzionek et al., Reference Dzionek, Dzik, Wojcieszyńska and Guzik2018); it is widely employed in the detection of the microbial metabolic activity in a variety of environmental samples, including coastal sediments and terrestrial soils. It is also applicable for organisms equipped with cell walls as fungi and algae (Adam et al., Reference Adam and Duncan2001; Li et al., Reference Li, Ou, Zheng, Gan and Song2011; Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Eynard and Chintala2015; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Huang, Lu, Liu and Yan2016). iii) The Adenosine 5’-TriPhosphate (ATP) assay was chosen to detect the presence even of very low levels of activity that would not be revealed with other tests (Schuerger et al., Reference Schuerger, Fajardo-Cavazos, Clausen, Moores, Smith and Nicholson2008; Dragone et al., Reference Dragone, Diaz, Hogg, Lyons, Jackson, Wall, Adams and Fierer2021). ATP is considered to be a biomarker of microbial viability (Venkateswaran et al., Reference Venkateswaran, Hattori, La Duc and Kern2003), so the ATP assay is commonly used to reveal reactions and processes occurring in living cells (Mempin et al., Reference Mempin, Tran, Chen, Gong, Kim Ho and Lu2013; Morciano et al., Reference Morciano, Sarti, Marchi, Missiroli, Falzoni, Raffaghello, Pistoia, Giorgi, Di Virgilio and Pinton2017); thus, this method is widely recognised as useful for analysing mineral soils in the Antarctic Dry Valleys (Cowan et al., Reference Cowan, Russell, Mamais and Sheppard2002) and has already been successfully applied on Martian-analogue soils (Moores et al., Reference Moores, Smith, Tanner, Schuerger and Venkateswaran2007) and in long-term stability experiments under simulated Martian conditions (Schuerger et al., Reference Schuerger, Fajardo-Cavazos, Clausen, Moores, Smith and Nicholson2008).

Materials and methods

Samples and studying area

Experiments were carried out on sandstones from two sites that were selected for their location and the varying degree of colonisation.

The rock substrates were collected by Laura Selbmann during the XXXI Antarctic Expedition (2015/2016) from Finger Mountain (Finger Mt) (2,133 m asl, 77° 44′ S 160° 40′ E) and Knobhead (2,450 m asl, 77° 54′ S 161° 31′ E), in the McMurdo Dry Valleys of Antarctica (Figure 2).

Figure 2. (a) map of the studied sites: magnification of the McMurdo Dry Valleys and (b) their localisation in the Continental Antarctica; (c) panoramic view of the McMurdo Dry Valleys; (d) Finger Mt; (e) Knobhead.

The rocks were excised using a geological hammer, placed in sterile bags and shipped to the University of Tuscia in Italy, where they were preserved at −20 ˚C in the Mycological Section of the Italian National Museum of Antarctica (MNA) until processing.

First, a macroscopic selection of a visibly colonised rock was made, based on recognition of layers that are typical of a cryptoendolithic community (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Example of the rocky samples. (a) Sandstone from Knobhead; (b) sandstone from Finger Mt; (c–d) magnification of cryptoendolithic communities in rocks from Knobhead and Finger Mt, respectively.

At each site, ten small discs with a diameter of 2 cm were then obtained by crushing the rock. These were prepared using a drill with tips that were sterilised using both UVC and flame. The endolithic communities were reactivated by hydration with 3 mL of sterile water, and the discs were then incubated for 96 h at 15 °C in an incubator equipped with a white light lamp (Fanelli et al., Reference Fanelli, Coleine, Gevi, Onofri, Selbmann and Timperio2021).

Treatments with lethal and sub-lethal thermal stress

Treatments were conducted on reactivated rock discs. To optimise and evaluate the feasibility of the selected viability/metabolic activity tests, the samples were appropriately divided into three portions. One portion, named ‘ht2’, was exposed to a dry temperature of 170 °C for 60 min to induce total mortality by applying a lethal stress almost equivalent to total sterilisation. To determine the effects of a putative non-mortal stress, a second portion, named ‘ht1’, was treated for 60 min at a lower dry temperature of 120 °C. The third portion, named ‘unt’, was left untreated and used as positive control. To account for the heterogeneity of endolithic rock colonisation, four replicates of crushed rock were used for each site and merged.

Viability tests

Cultivation on solid medium

To evaluate the viability of culturable microorganisms, in terms of Colony Forming Units (CFU), samples were grown under optimal conditions. One gram of powdered rock from Finger Mt (both untreated and heat-treated samples) was inoculated, in triplicate, onto Petri dishes containing Malt Extract Agar (MEA) (3% malt extract, 1.5% agar – VWR International bvba, Geldenaaksebaan, Leuven, Belgium); the dishes were incubated at 15 °C and inspected weekly (Onofri et al., Reference Onofri, Barreca, Selbmann, Isola, Rabbow, Horneck, De Vera, Hatton and Zucconi2008; Selbmann et al., Reference Selbmann, Stoppiello, Onofri, Stajich and Coleine2021).

The same experiment was set also preparing the same culture medium (MEA) amended with distilled water, into which sterilised Antarctic sandstone was rinsed for 1 week, and equally seeded; this to highlight the potential impact on colony growth of elements present in the natural substrate.

The propidium monoazide assay: treatment, DNA extraction and quantitative PCR

Modifying the method described in Canini et al. (Reference Canini, Adams, D’Acqui, D’Alò and Zucconi2024), aliquots of 0.5 g of powdered rock were collected and then suspended in 1.5 mL of phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS, pH 7.4); half of the samples were treated with propidium monoazide (PMA; Biotium, Inc., Fremont, CA, USA) at a final concentration of 40 μM and incubated in the dark for 30 min, under gentle agitation. The samples were then exposed to light in an ice bath 20 cm from a 650 W halogen lamp for five consecutive cycles of two min of light exposure followed by gentle agitation, to be then centrifuged at 16,100 g at 4 °C for 30 min. Finally, the samples were washed with PBS and stored at −20 °C until extraction. Following the manufacturer’s protocol for the DNeasy PowerSoil kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), DNA was obtained and quantified using the Qubit fluorometer system. It was then diluted in sterile water to achieve the same DNA concentration in each sample.

The extracted DNA was analysed by using a quantitative PCR assay. Quantification of both fungal and bacterial DNA was estimated using two different sets of primers: NS91F “5′-GTCCCTGCCCTTTGTACACAC-3′” and ITS51R “5′-ACCTTGTTACGACTT TTACTTCCT C-3′” for fungi (Sannino et al., Reference Sannino, Cannone, D’Alò, Franzetti, Gandolfi, Pittino, Turchetti, Mezzasoma, Zucconi, Buzzini and Guglielmin2022); Eub338 “5’-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3’” (Amann et al., Reference Amann, Binder, Olson, Chisholm, Devereux and Stahl1990) and Eub518 “5’-ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG-3’” for bacteria (Muyzer et al., Reference Muyzer, De Waal and Uitterlinden1993). Minimal modifications were made to the manufacturer’s instructions due to the low concentration (ng/uL) of some of the samples. Amplicons were generated in 25 μL reactions consisting in 12.5 μL of iQ™ SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, US), 1 μL of both forward and reverse primers, 5 μL of the extracted DNA and 5.5 μL of nuclease-free water. To obtain the standard curves, four different dilutions (from 102 to 105) of a solution containing plasmid pGEM® Easy Vector System and JM109 Competent Cells (Promega, Milan, Italy) were used. Finally, the reactions were performed using the BioRad CFX96™ detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, US).

The following amplification parameters were used: for the ITS region, 5 min at 95 °C and 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C followed by annealing at 58 °C for 20 s, with final extension of 15 s at 72 °C and 80° for 5s (Kwan et al., Reference Kwan, Cooper, La Duc, Vaishampayan, Stam, Benardini, Scalzi, Moissl-Eichinger and Venkateswaran2011); for the 16S, 5 min at 95 °C, 40 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C and annealing at 53 °C for 15 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 s (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Li, Li, Jiang, Han, Wu and Li2014).

Detection of metabolic activity: the fluorescein diacetate (FDA) and the ATP assays

The protocol for FDA was optimised for small quantities of rocks by modifying the method described by Green et al. (Reference Green, Stott and Diack2006).

Aliquots of 0.5 g of powdered rock were collected in 15 mL tubes and then suspended in 6.25 mL of 60 mM trisodium phosphate-Na3PO4 (pH 7.6). Subsequently, 62.5 μL of 9 μM FDA (© 2024 Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) were added. The tubes were then gently shaken and incubated in the dark at 15 °C for 3 h. After incubation, the reaction was stopped by adding 250 μL of acetone. Finally, 1.5 mL of the solution was transferred to a 2 mL tube, centrifuged at 16,000 g for 2 min and 1 mL of the resulting supernatant was read at 490 nm.

For the ATP assay, the method described by Dragone et al. (Reference Dragone, Diaz, Hogg, Lyons, Jackson, Wall, Adams and Fierer2021) was modified as follows: 0.5 g of powdered rock was collected in 1.5 mL tubes and then suspended in 0.5 mL of PBS 1X. Three 100 μL aliquots of the suspension were transferred to a 96-well plate (VWR International, LLC, Matsonford Rd. Radnor, USA), and three replicates of PBS alone were prepared as a negative control. After 15 min at room temperature (between 20 and 22 °C), 100 μL of Promega BacTiter-GloTM Microbial Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) were added to each replicate, and the plate was gently vortexed for 5 min, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence readings were recorded using a Heales MB-580 microplate reader (Heales, Shenzhen, China). The analysed samples were compared with a soil sample (referred to as DEB-S) collected near the University of Tuscia campus as a positive control.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.4.3).

The normal distribution of PMA-assay data was verified using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The data were normalised to a logarithmic scale, and the DNA amplification was considered both in presence and absence PMA and normalised to the control. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was performed (Onofri et al., Reference Onofri, de la Torre, de Vera, Ott, Zucconi, Selbmann, Scalzi, Venkateswaran, Rabbow, Sánchez Iñigo and Horneck2012; Reference Onofri, de Vera, Zucconi, Selbmann, Scalzi, Venkateswaran, Rabbow, de la Torre and Horneck2015; Pacelli et al., Reference Pacelli, Selbmann, Zucconi, Coleine, de Vera, Rabbow, Böttger, Dadachova and Onofri2019).

The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated for the FDA and ATP assays. For these, as well as for the cultivation test, a 2-sample unpaired t-test (Armour et al., Reference Armour, Powell and Boyce2008) was performed instead, since this is commonly used to compare two independent groups (Schober and Vetter, Reference Schober and Vetter2019), provided that the difference between the two means and their pooled standard error is assumed to be zero (Cleophas et al., Reference Cleophas and Zwinderman2018).

P-values equal to or less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Cultivation on solid medium

No significant differences in CFU count were detected when using a culture medium prepared with either pure distilled water or water that had been rinsed with sterilised Antarctic sandstone. For this reason, only the results obtained using the former are reported.

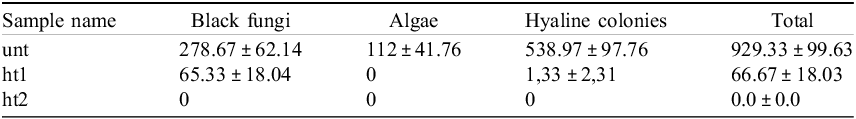

MEA as a culture medium enables different microbial populations to grow. Following a three-month incubation at 15 °C, a total count of CFU was performed, which revealed a statistically significant decrease (p-value < 0.0001) in both the heat-treated samples with respect to the untreated one (Figure 4). More specifically, a decrease of ∼89% in the total amount of CFU was observed in ht1, of which ∼95% were black fungi and the remaining 5% other hyaline colonies; no algae were detected. In contrast, no growth was detected in plates containing samples subjected to the lethal stress. Details are in Table 1.

Figure 4. Microbial growth in solid medium seeded with (a) untreated samples, (b) heat-treated samples ht1 (60 mins at 120 °C), and (c) heat-treated samples ht2 (60 mins at 170 °C). (d–h) Magnification of the microbial growth observed after three months of incubation for the untreated sample. (e) lichens, with black fungi and yeasts (black arrows); (f) yeast; (g) lichens with algae (green arrow); (h) black fungus.

Table 1. Results (mean ± SD) of the CFU count in untreated and heat-treated samples

Propidium monoazide assay

The amplification in untreated samples at each site, for both fungi and bacteria, was not significantly different in the presence of PMA. In fact, when the total DNA was compared with the DNA of cells with intact membranes, the magnitude of the amplification remained the same. However, a statistically significant progressive reduction in the amplification of DNA was observed in both heat-treated samples. Specifically, the decrease in the presence of PMA in ht1 and ht2 was of one order magnitude both for fungi and bacteria (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Results of PMA coupled with qPCR for untreated and heat-treated samples, both for fungi (ITS) and bacteria (EUB); statistical significance was assessed for each group, with ‘*’ referring to p-values < 0.05.

Moreover, in ht2 the amplification never exceeded a magnitude of 102, even in absence of PMA. Statistical analyses were performed also comparing three different groups: unt vs ht1, unt vs ht2 and ht1 vs ht2. A statistically significant difference was observed also in all the three groups. In terms of percentage, the damaged cells were around 30% for fungi and around 20% for bacteria in the untreated samples at both sites, whereas in the samples treated with heat stress were higher than 60%.

Detection of metabolic activity

The results of the FDA assay showed a statistically significant difference in the FDA absorbance between untreated and heat-treated samples (Figure 6).

Figure 6. FDA assay results for untreated and heat-treated samples; statistical significance was assessed for each group, with ‘*’ referring to p-values < 0.05.

With respect to the samples treated at 120 °C for 60 min, the absorbance resulted in a statistically significant decrease, while for samples treated at 170 °C for 60 min the absorbance value was less than 0.001, suggesting lack of metabolic activity.

For ATP assay the results showed a statistically significant difference in the absorbance between untreated and samples treated with the sub-lethal stress; more specifically, the untreated ones were around 0.35 for Finger Mt and 0.32 for Knobhead, while in heat-treated samples was around 0.19 for both sites. An important reduction was instead recorded in samples treated with the lethal stress, whose absorbance, around 0.13, was comparable to the one registered for the blank, around 0.12, containing only PBS (Figure 7).

Figure 7. ATP-assay results for untreated and heat-treated samples; statistical significance was assessed for each group, with ‘*’ referring to p-values < 0.05.

Discussion

Studying entire microbial communities is an extraordinary and delicate process, and the samples from planetary analogues are rare and precious.

Previous studies on the survival capabilities of microbial assemblages associated to epilithic and endolithic lichens of granites exposed to space conditions have involved techniques such as fluorescence measurements combined with viability kits (De la Torre et al., Reference de La Torre, Sancho, Horneck, de los Ríos, Wierzchos, Olsson-Francis, Cockell, Rettberg, Berger, de Vera and Ott2010; Wierzchos et al., Reference Wierzchos, De Los Ríos, Sancho and Ascaso2004) and microscopy analyses, including confocal scanning laser microscopy (CSLM), low-temperature scanning electron microscopy (LT-SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), as well as analyses of ascospores gemination to determine cell viability (de Vera et al., Reference De Vera, Horneck, Rettberg and Ott2002). In these studies, the use of fluorescence method consented to evaluate the photosynthetic activity of the lichens exposed to solar UV and VIS radiation, while the multimicroscopic approach revealed the survival of different lichenised algal and fungal cells after exposure (Sancho et al., Reference Sancho, De la Torre, Horneck, Ascaso, de Los Rios, Pintado, Wierzchos and Schuster2007; Raggio et al., Reference Raggio, Pintado, Ascaso, De La Torre, De Los Ríos, Wierzchos, Horneck and Sancho2011).

This pilot study aimed to develop a rapid, efficient experimental approach that would be accurate enough to be used in a variety of astrobiological analyses. The results here obtained, when compared with each other, revealed the presence of living microorganisms following extreme treatments or the absence of living cells in case of treatments with lethal stresses. This enables us to recognise and describe how the samples behaved differently depending on the stress applied, and additionally to identify a survival trend.

Cultivation on solid medium may give a direct observation of the viable and culturable organisms. Although non-culturable species remain not visible, the results obtained here clearly show a proportional decrease in viability according to the intensity of the stress applied, as well as the effect and responses of different microbial compartments to sub-lethal and lethal stresses. Exposure to the highest temperatures resulted in the complete inhibition of microbial growth in Finger Mt rocks, suggesting that treatment at 170 °C was lethal for the 100% of culturable microbes of the community. A proportional decrease in viability was observed in samples treated at 120 °C (above 89%), with black fungi showing significantly higher resistance. This result is not unexpected due to the known extreme tolerance of these Antarctic specimens, able to survive even high doses of ionising radiation and space conditions (Onofri et al., Reference Onofri, de la Torre, de Vera, Ott, Zucconi, Selbmann, Scalzi, Venkateswaran, Rabbow, Sánchez Iñigo and Horneck2012, Reference Onofri, de Vera, Zucconi, Selbmann, Scalzi, Venkateswaran, Rabbow, de la Torre and Horneck2015; Selbmann et al., Reference Selbmann, Zucconi, Isola and Onofri2015; Aureli et al., Reference Aureli, Coleine, Delgado-Baquerizo, Ahren, Cemmi, Di Sarcina, Onofri and Selbmann2023). Antarctic black fungi like Cryomyces antarcticus (Pacelli et al., Reference Pacelli, Selbmann, Zucconi, Coleine, de Vera, Rabbow, Böttger, Dadachova and Onofri2019) and Friedmanniomyces endolithicus (Pacelli et al., Reference Pacelli, Bryan, Onofri, Selbmann, Zucconi, Shuryak and Dadachova2018), in fact, are among the most resistant terrestrial life forms and the best target for astrobiological studies (Selbmann et al., Reference Selbmann, Pacelli, Zucconi, Dadachova, Moeller, de Vera and Onofri2018).

Other organisms, presumably lichens, also displayed resistance to the stress applied, confirming previous studies conducted on the International Space Station (ISS), where lichen surviving species were isolated and identified (Scalzi et al., Reference Scalzi, Selbmann, Zucconi, Rabbow, Horneck, Albertano and Onofri2012). Conversely, algae are the most susceptible with no growth even at the lowest stress applied; this is also not surprising, since photosystems and photosynthetic membranes are highly damaged by heat (Mathur et al., Reference Mathur, Agrawal and Jajoo2014).

For the analysis of non-culturable species, the PMA-qPCR coupled, the FDA and the ATP assays, normally applied on microbes in pure cultures, here were applied and optimised for our peculiar specimens of microbial communities. The PMA-qPCR assay allows specifically the detection of the proportion of death/alive cells based on the integrity of the cell membrane and is, therefore, an indirect assessment of the viability. The experiment has been set appropriately to detect viable cells of fungi and bacteria inhabiting the rock substratum examined. The results clearly show a significant decrease in viability of both microbial compartments according to the intensity of the stress applied with a more pronounced effect on fungi in rocks collected in both the localities. The decrease was detectable also after the lethal treatment with e difference of an order of magnitude in the amplification in the samples added with PMA; yet the amplification never exceeded a magnitude of 102 also in samples without PMA, revealing a high level of DNA alteration due to strong heating. According to these results, the test here optimised is promising to be applied even to reveal the effect of treatments simulating Mars conditions that will be performed in the frame of the CRYPTOMARS project, since it may enlighten the responses even in difficult samples such as already environmentally stressed or poorly colonised ones.

The detection of active metabolism was successfully assessed with the FDA and the ATP assays, both known as valid tools for measuring microbial activity in soils.

Differently from the PMA assay, the FDA and ATP tests do not consent to distinguish the viability or resistance to specific stress of each single microbial compartment (e.g. fungi and bacteria), but they both give an indication of the vigour and resistance of the whole community before and after treatments.

In conclusion, this study has provided a robust toolkit for assessing microbial resilience under extreme conditions. The polyphasic approach here optimised resulted to be systematic, comprehensive, easy to apply and reproducible.

Given the paucity of viability and metabolic assays available for studying environmental samples, it can be an appropriate groundwork not only for astrobiological investigations but can also represent a valid tool for microbial ecologists to be applied to reveal how, in an era of global changes, other peculiar microbial assemblages from extreme ecosystems respond to perturbations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Italian Space Agency (ASI) for coordination and financial support of the CRYPTOMARS project, under the contract n. 2023-12-U.0.; the Italian National Program for Antarctic Research (PNRA) for supporting sampling campaigns and providing the rock samples used in this study. Personal thanks to Dr. R. Mancinelli (NASA) for his precious suggestions in the cultivation experimental setting, Prof. S. Onofri for sharing several enlightening anecdotes about experiences in Antarctica, Prof. A. M. Vettraino for supplying the instruments for the ATP analyses and Dr. B. Bellisario for his precious support in the use of tools for statistical analyses (University of Tuscia). Finally, special thanks to Dr. F. Canini (University of Tuscia) for supporting the activities and improvement of the PMA protocol.