Non-technical Summary

A well-preserved frontal appendage of an early fossil arthropod, about 512 million years old, is described as a new radiodont species. Long, slender spines attached to most of its segments, together with other features, are inconsistent with combinations of characters expected of existing genera of radiodonts to which the new species might have belonged. It is assigned to a new genus, prompting discussion of relationships among these groups, including consideration of different patterns of modular development that are expressed in the four radiodont families currently recognized. The new species, with spines adapted neither for grasping nor for filtering, is inferred to have sought its prey by sweeping loose sediment on the seafloor and engulfing mainly worms by suction.

Introduction

Anomalocaris has been known since the late nineteenth century from isolated frontal appendages that were initially described as bodies of a shrimp-like crustacean (Whiteaves, Reference Whiteaves1892). Much later, Whittington and Briggs (Reference Whittington and Briggs1985) showed that body parts previously assigned to unrelated organisms constituted anterior “great appendages” and a radial mouth, associated with a specimen newly recognized as representing the trunk of the same animal. Subsequently, detailed reconstructions of Anomalocaris and Peytoia from the Burgess Shale by Collins (Reference Collins1996) led him to assign these anomalocaridids, together with Hurdia, to the newly defined arthropod order Radiodonta. Soon, 13 species of anomalocaridids grouped in seven genera were known (Daley, Reference Daley2013), constituting a substantial evolutionary radiation of early Cambrian predators with large anterior feeding appendages and circular jaws equipped with varying arrangements of inwardly facing gripping or shearing teeth.

Thereafter, the rate of discovery of new radiodonts further accelerated, soon yielding more than 40 described species that range up into the Early Ordovician, and possibly even later (Potin and Daley, Reference Potin and Daley2023; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Pates, Zhang, Lin, Ma, Liu, Wu, Zhang and Fu2024b). The already well-known rapid diversification of “worms” and other potential prey on the seafloor was hence shown to have been accompanied by the simultaneous evolution of varied arthropod predators with lightly sclerotized exoskeletons. Their success at that time is inferred to have been uninhibited by competition with cephalopods, fishes, and more heavily armed arthropods that would later contribute to their demise (Bicknell et al., Reference Bicknell, Ledogar, Wroe, Gutzle, Watson and Paterson2018). Early in this quick establishment of increasingly complex ecosystems, some radiodonts even evolved to become nektonic suspension feeders. Tamisiocaris borealis Vinther et al., Reference Vinther, Stein, Longrich and Harper2014 appeared first, in Cambrian Stage 3, and this role would later be taken up by early Ordovician hurdiids, two species of Pseudoangustidontus (Potin et al., Reference Potin, Gueriau and Daley2023), and the giant Aegirocassis benmoulae Van Roy, Daley, and Briggs, Reference Van Roy, Daley and Briggs2015 (see also Van Roy and Briggs, Reference Van Roy and Briggs2011), all pre-figuring in miniature much later basking sharks and whales.

Isolated frontal appendages of anomalocaridids were first described from the Kinzers Formation by Resser (Reference Resser1929) and by Resser and Howell (Reference Resser and Howell1938). This and additional material in the collection of the U.S. National Museum and that of the North Museum in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, were reassessed by Briggs (Reference Briggs1979). He observed only modest differences between the species then known as Anomalocaris pennsylvanica Resser, Reference Resser1929 and the type species, A. canadensis Whiteaves, Reference Whiteaves1892, from the Burgess Shale. More recently, all then-available specimens were further reassessed by Pates and Daley (Reference Pates and Daley2018). They reaffirmed the differentiation from A. canadensis of specimens they accepted as A. pennsylvanica, mainly on the forms of their ventral endites. However, they assigned other specimens to species of Amplectobelula, Tamisiocaris, and ?Laminacaris, thereby recognizing a relatively diverse assemblage of radiodonts. Since then, A. pennsylvanica has itself been reassigned by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Ma, Lin, Sun, Zhang and Fu2021b) to the newly defined anomalocaridid genus Lenisicaris, differentiated from Anomalocaris mainly by its relatively short endites lacking auxiliary spines.

Meanwhile, a relatively well-preserved single frontal appendage of another anomalocaridid, distinguished from any species so far found in the Kinzers Formation or elsewhere by the number of its podomeres and its long, knitting-needle-like endites without auxiliary spines, had been discovered (Fig. 1). The purpose of this paper is to describe this species; to draw attention to its implications bearing on patterns of development, adaptation, and the emerging classification of radiodont families; and to note that comparison with other taxa sets up a plausible hypothesis bearing on transitions in the range of feeding habits of anomalocaridids and other most closely related radiodonts.

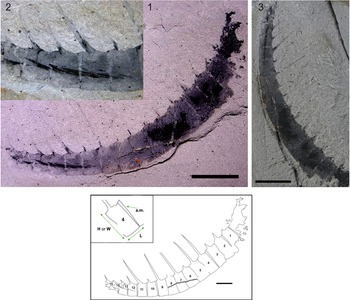

Figure 1. Frontal appendage of the holotype specimen of Verrocaris kerrymatti n. gen. n. sp., NMNS P–A 2300, from the Kinzers Formation (Cambrian, Series 2, Stage 4) at locality SB in Manheim Township, Pennsylvania. (1) Ventral view; photograph by Kerry Matt. (2) Podomeres 10–14, enlarged to highlight the nature and marginal positions of attachment of the endites. (3) Contrast enhanced to emphasize the impressions of long endites without auxiliary spines, beyond their preserved bases; photograph by Connor Hollinger. (4) Line drawing of the holotype frontal appendage. Key to inset: H, height, W, width, L, length of podomeres; a.m., arthrodial membrane. (1, 3) Scale bars = 1 cm; (4) scale bar = 5 mm.

Geological setting

The new anomalocaridid was found in the Emigsville Member of the Kinzers Formation (Cambrian, Stage 4, Dyeran), in Manheim Township, 6 km north of the city of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. In early Cambrian time, the edge of the continental shelf of Laurentia ran parallel to the trend of later Appalachian mountain building, through what is now southeastern Pennsylvania (Fig. 2). Here the Kinzers Formation conformably overlies the Vintage Formation, consisting largely of dolomite with occasional beds of carbonate breccia, accumulated on a deeper water ramp (Rogers, Reference Rogers, Zen, White, Hadley and Thompson1968; Read, Reference Read, Crevello, Read, Sarg and Wilson1989). The Kinzers Formation itself consists of a basal shale and otherwise mainly of limestones deposited in open-shelf and upper continental-slope environments. It is overlain by massive crystalline dolomite of the Ledger Formation, well established as having been deposited along the Appalachian shelf-edge margin of what has come to be known as the Great American Bank (Gohn, Reference Gohn1976; Barnaby and Read, Reference Barnaby and Read1990; Brezinski et al., Reference Brezinski, Taylor, Repetski, Derby, Fritz, Longacre, Morgan and Sternbach2012; de Wet et al., Reference de Wet, Rahnis, Hopkins, Murphy, Dvoretsky, Derby, Fritz, Longacre, Morgan and Sternbach2012).

Figure 2. Site of temporary excavation SB, holotype locality for Verrocaris kerrymatti n. gen. n. sp., in proximity to former classic exposures of Lagerstätten at site 22L, in the Emigsville Member of the Kinzers Formation, north and north-northwest of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Map courtesy of A. de Wet. For the broader geologic context of these sites, see Thomas et al. (Reference Thomas, Runnegar and Matt2020, fig. 3 and text).

Three members of the Kinzers Formation differ substantially in their development along strike. Around York, Pennsylvania, the Emigsville shale and the York (including massive carbonate slump breccias) and the Greenmount members all accumulated within the Bonnia–Olenellus Zone of Cambrian Series 2, Stage 4 (Taylor and Durika, Reference Taylor, Durika and Scharnberger1990). To the east, in the Lancaster area, and beyond, the Emigsville Member is overlain successively by an unnamed unit consisting mainly of shelf/slope limestones of latest early Cambrian age and the Longs Park Member, consisting of deeper water limestone, siltstone, and black shale that has yielded fossils comparable to those of the middle Cambrian “Ogygopsis Shale” fauna of British Columbia (Campbell, Reference Campbell1971).

The Emigsville Member varies from 30 to 70 m in thickness. Three facies were recognized by Skinner (Reference Skinner2005). His impure carbonate facies is represented by thickly bedded originally calcareous (since almost entirely leached) shales and siltstones, locally bearing abundant shelly fossils. Evidence of disturbance by winnowing, redeposition of transported sediment and fossils, and bioturbation are observed throughout this facies. A massive pelitic facies consists of thickly bedded, variably silty shale or mudstone, commonly well bioturbated, bearing varied but generally sparse fossils. It has been inferred to include sediment representative of intervals of relatively rapid sedimentation. Third, a well-laminated fine pelitic facies includes Lagerstätten yielding most of the fossils exhibiting preservation of soft parts and lightly sclerotized exoskeletons that are known from the Kinzers Formation. Bioturbation is generally absent, and locally abundant pyrite, now represented by molds, indicates the accumulation of organic-rich sediments in periodically anoxic environments (Powell, Reference Powell2009), alternating with influxes of very fine sediment interpreted as distal tempestites (Skinner, Reference Skinner2005). For further details on the preservation and taphonomy of fossils occurring in these Lagerstätten, see Thomas et al. (Reference Thomas, Runnegar and Matt2020).

Conway Morris (Reference Conway Morris1985) observed that the Kinzers Formation exhibits similarities to the Burgess Shale in the nature and preservation of its fossils and its setting on a shelf margin of Laurentia. The two sites were at similar tropical paleolatitudes, and Powell (Reference Powell2009) has documented analogous geochemical data bearing on the circumstances of deposition of the two formations. Even so, unlike the Burgess Shale, which was deposited at the base of the Cathedral Escarpment, the Emigsville Lagerstätten were not situated off a bank edge. Rather, these sediments accumulated in mid-shelf to shelf-break environments, more like those of the Sirius Passet Lagerstätte in Greenland (Hammarlund et al., Reference Hammarlund, Smith, Rasmussen, Nielsen, Canfield and Harper2018; Harper et al., Reference Harper, Hammarlund, Topper, Nielsen, Rasmussen, Park and Smith2019). From its stratigraphic context, the Emigsville shale appears to have been deposited farther offshore, with less input of clastic sediments, than the prodeltaic Yu’anshan Formation (Saleh et al., Reference Saleh, Qi, Buatois, Mángano, Paz, Vaucher, Zheng, Hou, Gabbott and Ma2022), which embraces the Lagerstätten that have yielded the prolific Chengjiang fauna.

Materials and methods

Locality information

The holotype specimen was collected from a temporary basement excavation exposing fossil-bearing shale of the Emigsville Member of the Kinzers Formation, Cambrian Series 2, Stage 4, at 223 Settlers Bend, near its intersection with Buch Avenue, 40.094935°N, 76.3221983°W, Manheim Township, Lancaster, Pennsylvania (SB on Fig. 2). No outcrop has ever been accessible at this location. The specimen was made available to us for study by the collector, Mr. Kerry Matt, with the concurrence of the landowners. A juvenile specimen (USNM 25561 and NMNS P-A 388, part and counterpart), previously assigned to other taxa, is here also assigned to the new species. This latter specimen was collected from the Kinzers Formation at the locality listed as 22L in the Smithsonian file, cited as such by Resser and Howell (Reference Resser and Howell1938). This locality (Fig. 2) is 2.3 km west of that where the new holotype was found.

Methodology

Our comparison of lengths of endites relative to podomere heights among radiodont frontal appendages is based on direct measurements of the holotype of the new species (Fig. 1.4) and comparable measurements made on scale drawings of the other species figured by authors cited in the figure caption. Graphs documenting proportions of parts of the new appendage and comparison of the lengths of its endites with those of related taxa were generated by Excel. Photographs were taken as follows: Figure 1.1, 1.2, the best available images in this state, were taken by the collector with a simple camera; Figure 1.3 was taken by Connor Hollinger with a Sony a1 and Sony FE 24-70mm f/2.8 GM II camera, at 70mm in full-frame mode; Figure 4 images were taken with a computer-linked Leica MC 120 HD camera attached to a Leica S 60 stereomicroscope and processed in Photoshop to enhance otherwise very limited contrast.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

The holotype of the new species described in this paper is archived in the collection of the North Museum of Nature and Science (NMNS) in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Access to specimens of Lenisicaris pennsylvanica Resser, Reference Resser1929 and other material from the Kinzers Formation studied by Briggs (Reference Briggs1979) and Pates and Daley (Reference Pates and Daley2018) was provided at the North Museum of Nature and Science, where they are cataloged with numbers preceded by P-A. Specimens archived in the Department of Paleobiology at the U.S. National Museum of Natural History are cited as USNM PAL.

Systematic paleontology

Panarthropoda Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1995

Arthropoda Gravenhorst, Reference Gravenhorst1843

Order Radiodonta Collins, Reference Collins1996

Family Anomalocarididae Raymond, Reference Raymond1935

Diagnosis

Radiodonts with a small head, a pair of eyes born on short stalks, a small dorsal carapace, and a unique triradial oral cone; frontal appendages with 13 to 15 distal articulated podomeres bearing pairs of simple endites that may or may not alternate long/short in length and that are equipped proximally in some species with a pair of short auxiliary spines; well-developed lateral flaps and an elaborate tail consisting of a medial blade and three pairs of upwardly extended furcae.

Remarks

Taxa assigned to this family share general diagnostic features with taxa constituting the Amplectobelulidae (Potin and Daley, Reference Potin and Daley2023). However, the paired endites of anomaolocaridids are generally unspecialized and similar to one another in form. They differ most obviously in this way from amplectobelulids, which are strikingly characterized by a large, specialized endite attached to podomere 4, together with a peduncle composed of three segments and gnathobase-like elements in place of an oral cone. Currently, the Anomalocarididae embraces only four formally described species, including that introduced here, although several other undescribed radiodonts have been informally affiliated with Anomalocaris. The diagnosis of this family is problematic in that features of the frontal appendage are variable, and those of the carapace, the triradial oral cone, and the tail are known only from the single species Anomalocaris canadensis, recently reassessed by Daley and Edgecombe (Reference Daley and Edgecombe2014). The other anomalocaridid species so far described are represented only by isolated frontal appendages with paired endites that may or may not alternate long/short and that lack auxiliary spines.

Genus Verrocaris new genus

Type species

Verrocaris kerrymatti new species, by monotypy.

Diagnosis

As for the type species here described, by monotypy.

Occurrence

As for the type species.

Etymology

From the Latin verb verrere, “to sweep,” and the Latin caris, a marine shrimp or crab-like animal, ex Greek “karis” with the same meaning.

Remarks

This genus exhibits a unique set of characters within the family to which it can most readily be affiliated: 15 podomeres, long spiniform endites that do not alternate long/short in length, separately attached at the margins of their podomeres and without auxiliary spines. In other combinations, these features characterize the frontal appendages of related genera.

Verrocaris kerrymatti new genus new species

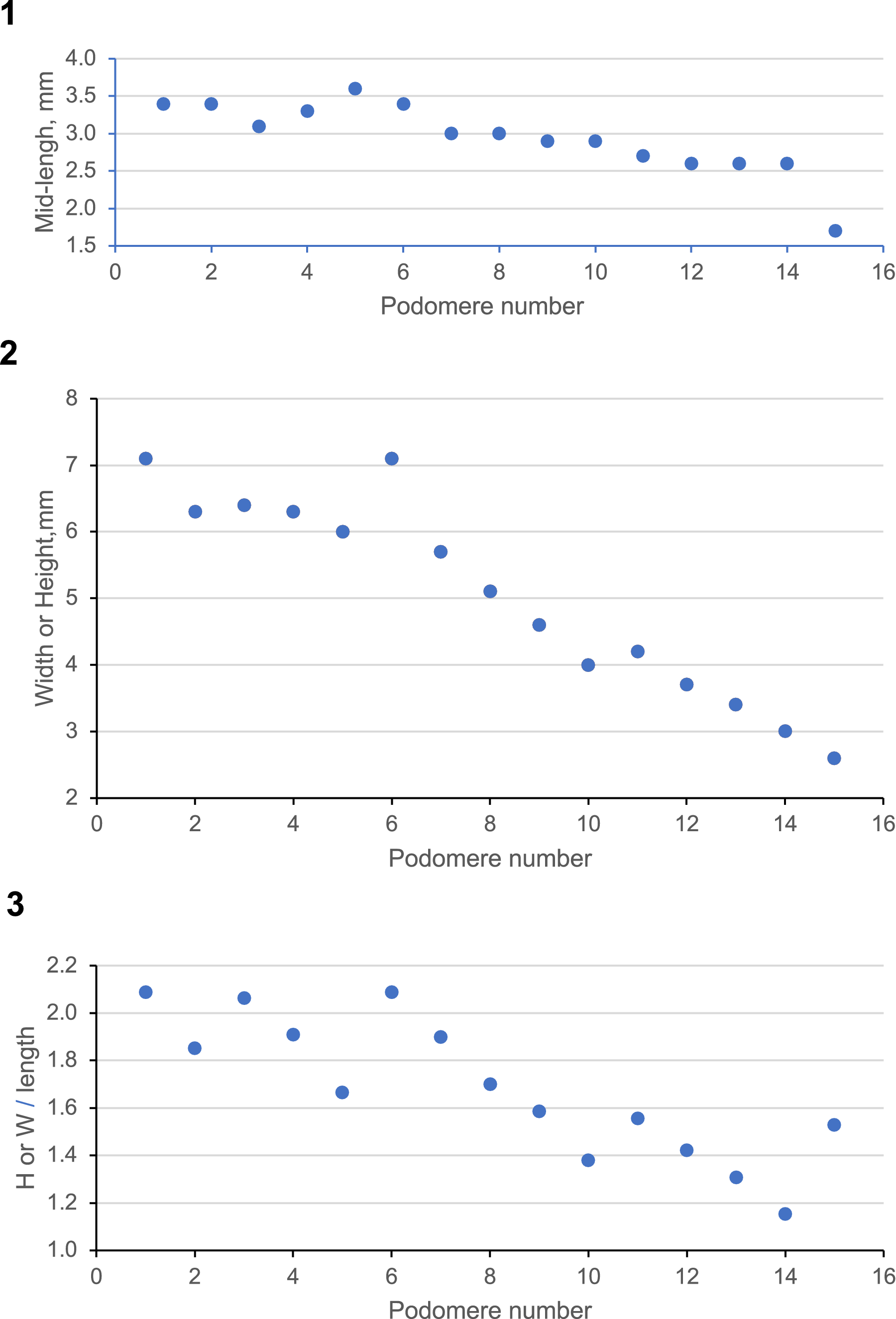

Figure 3. Sizes and shapes of podomeres along the length of the holotype appendage. (1) Length of podomere at its mid-line versus podomere number. (2) Height of podomere proximal from fracture, width of podomere distally (see text) versus podomere number. (3) Shape, height or width of podomeres versus their lengths. For definitions, see Figure 1.4; for data, see Appendix.

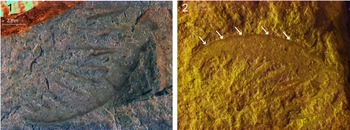

Figure 4. Partial frontal appendage of a juvenile anomalocaridid, here referred to Verrocaris kerrymatti n. gen. n. sp., from the Kinzers Formation (Cambrian, Series 2, Stage 4) at locality 22L in East Petersburg, Pennsylvania. (1) Part, USNM PAL 90827. (2) Counterpart, NMNS P-A 388; arrows point to small dorsal spines at the distal margins of distal podomeres.

v.Reference Resser and Howell1938 Anomalocaris pennsylvanica Resser and Howell, USNM 90827, p. 231, pl. 13, fig. 5.

v.Reference Briggs1979 Anomalocaris pennsylvanica Briggs, NMNS P-A 388, p. 641, not figured.

v.Reference Pates and Daley2018 Tamisiocaris aff. T. borealis Pates and Daley, NMNS P-A 388, p. 1240, fig. 4a, b and USNM 90827, not figured.

Holotype

NMNS, P-A-2300, North Museum of Nature and Science, Lancaster, Pennsylvania. An isolated, almost complete frontal appendage. A counterpart exists. It was formerly in a private collection, but its current whereabouts is not known.

Material

The holotype P-A-2300 is a single isolated frontal appendage with its distal articulated podomeres and the bases of their attached endites well preserved. The lengths of most of its long, spine-like endites can be inferred from their impressions, molds in the shale (Fig. 1.1, 1.3). A previously described distal portion of a frontal appendage, originally assigned to Anomalocaris pennsylvanica by Resser and Howell (Reference Resser and Howell1938) and by Briggs (Reference Briggs1979), was recently referred to Tamisiocaris by Pates and Daley (Reference Pates and Daley2018). This specimen, USNM PAL 90827 part (Fig. 4.1) and NMNS P-A 388 counterpart (Fig. 4.2), is here inferred to represent a juvenile instar of V. kerrymatti n. gen. n. sp.

Diagnosis

A radiodontid frontal appendage with a peduncle and 15 distal articulated podomeres; paired spiniform ventral endites, in length 1.5 or more times the heights of their podomeres (except most distally); endites not alternating long/short, attached separately at anterior and posterior margins of the podomeres, and bearing no auxiliary spines.

Occurrence

Known from two specimens recovered from the Emigsville Member of the Kinzers Formation, Cambrian Series 2, Stage 4 at sites SB and 22L (Fig. 2) in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.

Description

The flattened holotype represents a single frontal appendage, consisting of 15 distal articulated podomeres and a largely deteriorated peduncle (Fig. 1), lying on a bedding plane in olive-gray shale. The appendage spans 5.4 cm along its midline, curving about 50° as it tapers, and the podomeres become shorter distally (Fig. 3.1). The specimen is twisted along its length. The five most proximal podomeres are seen in lateral aspect, as is usual for isolated radiodont frontal appendages. Podomeres 6–8 are distorted by an oblique fracture, representing the locus of twisting of the appendage (Fig. 1.1, 1.4). Seven distal podomeres display their ventral surfaces. Narrow triangular gaps between the peduncle and podomeres 1–4 represent the locations of arthrodial membranes about which the podomeres were able to be flexed (Fig. 1.1, 1.4). These attachments are not seen in the twisted portion of the appendage, but they reappear as narrow strips that are more nearly rectangular between podomeres 9–12, as is to be expected on the ventral surface of the appendage.

The podomeres become smaller, declining in length (Fig. 3.1) and height (Fig. 3.2) along the appendage. The most proximal podomeres are about twice as high as they are long, declining distally in height until this measurement is offset by the fracture (Fig. 3.2, 3.3). Thereafter, it is the width of the appendage that is seen to decline distally. The regularity of change in podomere proportions that is apparent along the length of the appendage, apart from the effects of the fracture, suggests that the proportions of height and width of the podomeres are relatively alike along the length of the appendage.

All the endites attached to podomeres 1–15 of the distal articulated region are broken off at short distances from their attachments. Those associated with podomeres 1–11 are inferred from their impressions in the shale to have been long, 1.3 to about 2.0 times the lengths of the podomeres to which they are attached (Fig. 1.1, 1.3). The endites do not alternate long and short as in Anomalocaris canadensis (Briggs, Reference Briggs1979; Daley and Edgecombe, Reference Daley and Edgecombe2014; Pates and Daley, Reference Pates and Daley2018) and species assigned to Lenisicaris (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Ma, Lin, Sun, Zhang and Fu2021b). The endites attached to podomeres 12–14 are much shorter, and the last podomere bears a relatively long terminal spine.

The twisted preservation of this appendage allows the points of attachment of the paired distal endites to be seen directly. They are set far apart, near the anterior and posterior margins of each podomere, distal from the midpoints of the lengths of podomeres 9–14 (Fig. 1.1, 1.2). It can be seen there also that the endites, otherwise knitting-needle-shaped, broaden toward their bases. Thus, the endites were contiguous, integral parts of the podomeres from which they extend, with no articulation at their bases. The fine preservation of some of the distal endites and their molds indicates that the absence of auxiliary spines is real and not a consequence of loss in the process of postmortem preservation. There is a disadvantage associated with the orientation of the distal podomeres, however. The holotype provides no evidence of the presence or absence of dorsal spines at the distal margins of the podomeres. The form of the peduncle is also uncertain because of its scrappy preservation. It bears a projection near its distal margin that may or may not constitute part of the broad or irregularly shaped base of an endite.

Etymology

The species name applied to Verrocaris kerrymatti n. gen. n. sp. acknowledges the valuable contributions of Kerry D. Matt, who has discovered a variety of taxa not previously recognized in the Kinzers fauna (Thomas, Reference Thomas2021), and who has made the type specimen of V. kerrymatti and other important material available for study and description by the authors.

Remarks

Pates and Daley (Reference Pates and Daley2018) designated the latter juvenile radiodont as Tamisiocaris aff. T. borealis. They based this assessment on their observations that the 8 or 9 podomeres preserved are approximately square, becoming proportionately more elongate, hence rectangular distally, and that the slender, paired endites are about twice as long as their associated podomere heights. We concur in these observations, except to note that this specimen’s most distal podomeres are comparable in shape to those of the holotype of Verrocaris kerrymatti n. gen, n. sp., while the most proximal ones preserved are taller than they are long. In addition, we see evidence of the presence of very small dorsal spines at the distal margins of the podomeres (Fig. 4.2).

Pates and Daley (Reference Pates and Daley2018) enabled this specimen to be embraced in the genus Tamisiocaris by revising its diagnosis on the basis of only the type specimen of T. borealis Daley and Peel, Reference Daley and Peel2010, which lacks preservation of auxiliary spines. These spines were later discovered in association with specimens collected at the same outcrop as the holotype. Moreover, it was this later discovery that prompted recognition of T. borealis as a mid-water suspension feeder (Vinther et al., Reference Vinther, Stein, Longrich and Harper2014). This then first-recognized mode of radiodont adaptation has since become generally associated with the genus and with the family Tamisiocarididae (Lerosey-Aubril and Pates, Reference Lerosey-Aubril and Pates2018; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Fu, Ma and Lin2021a).

In our view, diagnosis of the genus Tamisiocaris should be redefined to include its auxiliary spines, consistent with current paleobiological usage. Hence, we see the partial frontal appendage USNM PAL 90827 and NMNS P-A 388 as being more plausibly identified as a juvenile specimen of Verrocaris kerrymatti n. gen. n. sp., judging from the limited available data: podomeres that become less high relative to their length distally, long paired spiniform endites that do not alternate long/short in length, and the absence of auxiliary spines. It is unclear whether the paired endites were attached together, near the ventral midline of the appendage, as has been inferred in T. borealis (Vinther et al., Reference Vinther, Stein, Longrich and Harper2014), or at the margins of the podomeres as in V. kerrymatti (Fig. 1.1, 1.2). However, in three of the most proximal pairs of endites preserved (Fig. 4.1), the “sister” endites diverge at an angle of about 15° away from their podomeres, rather than running parallel to one another. This suggests that their bases may have been in different planes before flattening of the specimen in the plane of the bedding.

V. kerrymatti differs from Anomalocaris spp. in that the new species has 15 rather than 13 distal articulated podomeres. Its proximal podomeres are not elongated along the length of the appendage to the same extent as those of A. canadensis. Podomeres 1–11 of V. kerrymatti bear endites that are longer and narrower than those of Anomalocaris spp., and its endites do not alternate long and short on successive podomeres (Fig. 5). Moreover, the endites of V. kerrymatti bear no auxiliary spines.

Figure 5. Comparison of the relative lengths of endites (in proportion to podomere heights) of Verrocaris kerrymatti n. gen. n. sp. with related radiodonts. Data sources: V. kerrymatti n. gen. n. sp., original measurements, Oxman (Reference Oxman2014); Lenisicaris pennsylvanica (Resser and Howell, Reference Resser and Howell1938 ) (Briggs, Reference Briggs1979, text-fig. 18); Anomalocaris canadensis Whiteaves, Reference Whiteaves1892 (Briggs Reference Briggs1979, text-figs. 5, 10); Shucaris ankylosskelos Wu et al., 2024 (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Pates, Liu, Zhang, Lin, Ma, Wu, Chai, Zhang and Fu2024a) (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Bergström and Ahlberg1995, figs. 7, 8); Houcaris saron (Hou, Bergstrom, and Ahlberg, Reference Hou, Bergström and Ahlberg1995) (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Bergström and Ahlberg1995, fig. 3a, b); Echidnacaris briggsi (Nedin, Reference Nedin1995) Daley et al. (Reference Daley, Paterson, Edgecombe, García-Bellido and Jago2013, fig. 1A, B); Tamisiocaris borealis Daley and Peel, Reference Daley and Peel2010 (Vinther et al., Reference Vinther, Stein, Longrich and Harper2014, fig. 1a). For data, see Appendix.

V. kerrymatti differs from the type species of Lenisicaris, L. lupata Wu, Ma, Lin, Sun, Zhang, and Fu, 2021 (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Ma, Lin, Sun, Zhang and Fu2021b) and from L. pennsylvanica in that the new species has 15 rather than 13 distal articulated podomeres and its endites are spiniform and much longer (Table 1). V. kerrymatti also differs from these two species in that its endites do not alternate long and short in length along the appendage. This feature is expressed only weakly in L. lupata, but alternation in the lengths of endites is unequivocal in L. pennsylvanica (Briggs, Reference Briggs1979; Pates and Daley, Reference Pates and Daley2018).

Table 1. Summarized comparison of character states of the frontal appendages of the new radiodont Verrocaris kerrymatti n. gen. n. sp. and genera to which it might have been assigned

Note: ? - Unknown

V. kerrymatti differs from Tamisiocris borealis in that the new species lacks the fine auxiliary spines characteristic of Tamisiocaris. In addition, the paired endites of V. kerrymatti are attached far apart, at the anterior and posterior margins of the podomeres (Fig. 1.1, 1.2), in the same positions of attachment as the endites of Houcaris magnabasis from the Pioche Formation of Nevada, illustrated by Pates et al. (Reference Pates, Daley, Edgecombe, Cong and Lieberman2021, fig. 10A, B). In this respect, the endites of both species differ from those of T. borealis, which are inferred to have been attached close together, near the ventral midline of the appendage (Vinther et al., Reference Vinther, Stein, Longrich and Harper2014).

Hence, the characteristics of V. kerrymatti deviate in different ways from the established diagnoses of all three genera, Anomalocaris, Tamisiocaris, and Lenisicaris (Table 1). It seems least appropriate to assign the new species to Tamisiocaris given that V. kerrymatti lacks the uniquely oriented auxiliary spines characteristic of endites of T. borealis. The emergence of these fine, homogeneous, and closely spaced spines, attached at a high consistent angle to the endites, was a key innovation that enabled the frontal appendages of Tamisiocaris to evolve as filters employed in suspension feeding (Vinther et al., Reference Vinther, Stein, Longrich and Harper2014). This feature, facilitating a shift from bottom feeding to a new way of life, is certainly appropriate to serve as the basis in adaptive morphology for recognition of a distinct genus and family.

The frontal appendage of V. kerrymatti differs from those of species assigned to both Anomalocaris and Lenisicaris in the number of its podomeres and in the lack of alternation in length of its endites. Its endites are longer and narrower, also lacking the auxiliary spines characteristic of Anomalocaris. To accommodate V. kerrimatti in either of these genera, one or the other of their diagnoses would have to be revised, a procedure that we are reluctant to undertake on the basis of one new species represented by only a single frontal appendage. For the same reasons, we were not eager to establish a new genus on the basis of a single new species. However, our decision to do so is consistent with current taxonomic practice in the still preliminary study and documentation of radiodont arthropods, as exemplified by recent accounts of Guanshancaris (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Huang and Hu2013) and Laminacaris (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Pates, Cong, Daley, Edgecombe, Chen and Hou2019).

V. kerrimatti has characters (15 distal articulated podomeres that are proximally tall, rectangular, and distally more nearly square) in common with Shucaris ankylosskelos Wu, Pates, Liu, Zhang, Lin, Ma, Wu, Chai, Zhang and Fu 2024 (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Pates, Liu, Zhang, Lin, Ma, Wu, Chai, Zhang and Fu2024a), a species that its authors chose not to assign to any existing family. However, these two species differ in that the endites of S. ankylosskelos are only as long as their podomeres are tall, they alternate slightly long/short in length, and they bear auxiliary spines that decline in number from three proximally to two on endites 5–7 and no more than one distally. Moreover, Shucaris ankylosskelos bears two pairs of endites on its first distal articulated podomere, a feature that is unique to this species (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Pates, Liu, Zhang, Lin, Ma, Wu, Chai, Zhang and Fu2024a).

Frontal appendages of Paranomalocaris simplex Jiao et al., Reference Jiao, Pates, Lerosey-Aubril, Ortega-Hernández, Yang, Lan and Zhang2021, recently described from the Guanshan Biota of southern China, also bear long, thin endites. Attached to most of the 20 or more podomeres, these endites are inferred on limited data to have alternated long/short. They appear almost entirely to lack auxiliary spines, apart from hints of their presence on the dorsal margins of one or two of the most distal podomeres. Relatively long dorsal spines, projecting distally across dorsal contacts between podomeres of this species (Jiao et al., Reference Jiao, Pates, Lerosey-Aubril, Ortega-Hernández, Yang, Lan and Zhang2021, figs. A1, A2), would have served well to prevent upward flexing of the appendage in response to resistance exerted by loose sediment through which the endites were drawn in searching for prey, in a manner comparable to that which we infer for V. kerrymatti (see the following). These similarities are notable in that V. kerrymatti and P. simplex occur in strata of much the same age (Cambrian Stage 4) that were likewise deposited in generally shallower and nearer-to-shore environments than those occupied by most Burgess Shale-type faunas. However, V. kerrymatti is quite unlike the type species, Paranomalocaris multisegmentalis Wang, Huang, and Hu, Reference Wang, Huang and Hu2013, which has short, notably stout endites equipped with well-developed auxiliary spines. Given our assessment of patterns of development of endites and their auxiliary spines, we find it curious that the two species assigned to Paranomalocaris, both based only on small numbers of isolated frontal appendages, have been referred to the same genus.

In the assignment of radiodont species to families, the occurrence of endites that alternate long/short along the frontal appendage has been seen as a notably characteristic feature of the Anomalocarididae (Daley and Edgecombe, Reference Daley and Edgecombe2014; Pates and Daley, Reference Pates and Daley2018; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Ma, Lin, Sun, Zhang and Fu2021b). However, this simplest of steps in the direction of differentiation of form and inferred function of endites on the same frontal appendage is variable in its expression. It is absent in V. kerrymatti. In this respect and in their numbers of podomeres, the Anomalocarididae are in fact variable. The family Amplectobelulidae is well characterized by the sharp differentiation in form of the large endite attached to podomere 4 of the frontal appendage. The frontal appendages of taxa assigned to the Tamisiocarididae exhibit two quite different modes of specialization of their frontal appendages. Some evolved even greater differentiation among the forms of their endites with varied patterns of auxiliary spines, while Tamisiocaris itself developed a network of identical endites and attached auxiliaries, integrated to act in synchrony to serve a common function (see next sections).

Phylogenetic ambiguities

Over the past decade, phylogenetic analyses employing a variety of methods have been applied to rapidly expanding, substantially overlapping data sets representing characters of increasingly many newly discovered early arthropods (Vinther et al., Reference Vinther, Stein, Longrich and Harper2014; see Potin and Daley, Reference Potin and Daley2023 for a comprehensive review). Radiodonts, first recognized taxonomically as major players in this great adaptive radiation by Collins (Reference Collins1996), have emerged as a diverse but cohesive stem group of innovative predators that arose close to the evolutionary nexus between lobopodians and biramous, near-crown group arthropods.

Four families have been widely recognized on the basis of these analyses (Vinther et al., Reference Vinther, Stein, Longrich and Harper2014; Lerosey-Aubril and Pates, Reference Lerosey-Aubril and Pates2018; Zeng et al., Reference Zeng, Zhao and Zhu2022). The Hurdiidae emerge as a diverse but consistently coherent clade, rooted early and generally apart from the other three families (Moysiuk and Caron, Reference Moysiuk and Caron2025). The Anomalocarididae currently includes only two or three named genera (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Ma, Lin, Sun, Zhang and Fu2021b; Zeng et al., Reference Zeng, Zhao and Zhu2022), although some species have been designated as Anomalocaris spp. in open nomenclature. Others are attributed to the Amplectobeluidae, the two families having a common root (Lerosey-Aubril and Pates, Reference Lerosey-Aubril and Pates2018; Zeng et al., Reference Zeng, Zhao and Zhu2022). The Tamisiocarididae are least consistent, “unstable” according to Potin and Daley (Reference Potin and Daley2023), with varying relationships implied by studies employing different data sets and modes of analysis. The tamisiocaridids are limited in their stratigraphic range to strata of Cambrian Series 2 (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Fu, Ma and Lin2021a). They have been construed either as a deeply rooted sister group of the hurdiids (Lerosey-Aubril and Pates, Reference Lerosey-Aubril and Pates2018) or as the most highly derived branch of a large clade that embraces the anomalocaridids and the amplectobeluids at successively greater removes (Zeng et al., Reference Zeng, Zhao and Zhu2022). Shucaris, unassigned by its authors to a family (see the preceding), is also inferred to be related to this complex (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Pates, Liu, Zhang, Lin, Ma, Wu, Chai, Zhang and Fu2024a). These ambiguities parallel those recognized at a higher taxonomic level by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Pisani and Donoghue2023), among alternative associations of Euarthropoda, Onychophora, and Tardigrada as clades within Panarthropoda. Hence, we are led to ask whether some of the characters currently inferred to link taxa now assigned to the Tamisiocardidae may not in fact be homologous. Might patterns of development involved in the construction of architectural complexity (Simon, Reference Simon1963), such as those recognized in arthropods at the level of tagmata (Cisne, Reference Cisne1974; Moysiuk and Caron, Reference Moysiuk and Caron2025), be more fundamental indicators of evolutionary relationships than potentially pliable character states that could have varied independently in more than one way?

Exploits in modularity

Emergence of the Metazoa was initially facilitated by modular exploitation of diversifying cell types that were employed in constructing increasingly complex organ systems, supported by internal hydrostatic or mainly external hardened skeletons. Early in the Cambrian Explosion, worms and arthropods rapidly took advantage of anterior–posterior segmentation as the simplest way, first to increase body size and subsequently to differentiate structures associated with serial body segments, or groups of similar segments, adapted to serve discrete functions (Jacobs, Reference Jacobs1990; Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs, Hughes, Fitz-Gibbon and Winchell2005; Thomas, Reference Thomas, Callebaut and Rasskin-Gutman2005). Long-term outcomes of this process had previously been quantified by Cisne (Reference Cisne1974), who limited his focus to aquatic arthropods, in terms of an information function he defined as “tagmosis.”

Recently, assessing the hurdiid radiodont Stanleycaris, Moysiuk and Caron (Reference Moysiuk and Caron2021) pointed out that a parallel subsidiary process of differential “tagmatic partitioning” occurred among the radiodonts as endites associated with successive podomeres of individual frontal appendages evolved to serve discrete adaptive functions. Here we note that this pattern of modularity is repeated, a step further down the hierarchy of anatomical design, in the evolution of accessory spines attached to the endites of species now assigned to the genus Houcaris (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Bergström and Ahlberg1995; Pates et al., Reference Pates, Daley, Edgecombe, Cong and Lieberman2021; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Fu, Ma and Lin2021a) and to a lesser degree in Shucaris ankylosskelos (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Pates, Liu, Zhang, Lin, Ma, Wu, Chai, Zhang and Fu2024a).

The development of auxiliary spines in Houcaris varies considerably, among endites attached to podomeres along the length of the frontal appendage, between species, and apparently among individuals, although recognition of this last aspect of variation is susceptible to vagaries of preservation. In both H. saron (Hou, Bergström, and Ahlberg, Reference Hou, Bergström and Ahlberg1995) and H. magnabasis (Pates et al., Reference Pates, Daley, Edgecombe, Cong and Lieberman2021), two distinctly different kinds of auxiliary spines are associated with the more proximal articulated podomeres (2 to 7 or 8). Distally, each endite bears a terminal spine accompanied by one or two pairs of spines attached at low angles to the endite behind it. Together, these three or five terminal spines constitute a trident-like tool shaped like a bird’s foot or a frozen hand (Fig. 6.1, 6.2). Behind them, more proximally on each endite, three auxiliary spines, all about the same short length, are attached at a higher angle to the distal side of the endite. Finally, close to the base of each endite, two more spines that have been characterized as setules (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Fu, Ma and Lin2021a) are attached almost perpendicularly to the surface of the podomere itself.

Figure 6. Modes of development of auxiliary spines. (1, 2) Frontal appendage (FA) of Houcaris saron (Hou, Bergstrom, and Ahlberg, Reference Hou, Bergström and Ahlberg1995) from Chengjiang, South China, with distinct categories of auxiliary spines and setules (see text): (1) camera lucida drawing of FA; (2) three-dimensional computer model derived from a micro-CT scan. Cp, podomere; En, endite, right and left; as, auxiliary spine; se, setule. From Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Fu, Ma and Lin2021a, fig. 2c, e); for copyright, see acknowledgements. (3, 4) Frontal appendage of Tamisiocaris borealis Daley and Peel, Reference Daley and Peel2010 from Sirius Passet, Greenland, with identical, uniformly spaced auxiliary spines constituting a mesh or “net” in aggregate: (3) photograph of FA; (4) digital reconstruction of FA. Art, podomere; Am, articulating membrane; Sp, “spine” = endite; As, auxiliary spine. From Vinther et al. (Reference Vinther, Stein, Longrich and Harper2014, figs. 1a, 2a); for copyright, see acknowledgements. (1, 2) Scale bars = 5 mm.

In short, the auxiliary spines associated with podomeres 2 to 7 or 8 of Houcaris are differentiated morphologically into two or three distinct sets, implicitly having different functions. The terminal, trident-like assemblies imply by their design the capacity to be used in piercing prey or perhaps more likely probing in search of infaunal organisms. However, the more proximal, evenly spaced auxiliaries suggest they could have been used like a rake to capture meiofaunal prey.

Together with differentiation in the length and spinosity of endites of Houcaris along the lengths of its frontal appendages, these observations stand in marked contrast with the characteristic properties of Tamisiocaris borealis. It is the uniformity of form and deployment of identical slender endites and tiny auxiliary spines across its entire frontal appendage (Fig. 6.3, 6.4) that prompted the highly plausible inference that Tamisiocaris was a suspension feeder, adapted to sweep up swarms of plankton (Vinther et al., Reference Vinther, Stein, Longrich and Harper2014).

Two entirely different patterns of adaptation are represented here. In the case of Houcaris, structural divergence was developmentally unconstrained (Moysiuk and Caron, Reference Moysiuk and Caron2021), locally micromanaged to serve different purposes, even by distinct groups of auxiliary spines on the same individual endites. By contrast, the uniform auxiliaries of Tamisiocaris evolved in tandem as components of a common structure that evolved to perform a single function by acting together as a whole.

Inferred mode of life and feeding of Verrocaris kerrymatti n. gen. n. sp

Radiodonts in general are inferred to have been active swimmers judging from their flexible body segments, unique lateral flaps that are not present in crown group arthropods (Edgecombe, Reference Edgecombe2015), and posterior fans or furcae (Sheppard et al., Reference Sheppard, Rival and Caron2018). Their variously elaborated frontal appendages, radial jaws with flat inwardly facing teeth, and large compound eyes indicate that they were predators. Although they were once supposed to have preyed on trilobites, it is now generally agreed that most, if not all, radiodonts fed either on soft-bodied prey or on organisms small enough that they could be ingested whole (Daley and Bergström, Reference Daley and Bergström2012; De Vivo et al., Reference De Vivo, Lautenschlager and Vinther2021; Potin and Daley, Reference Potin and Daley2023).

Distinctive features of radiodont frontal appendages are inferred to have been involved in searching for, capturing, and manipulating prey to deliver it to the mouth (Whittington and Briggs, Reference Whittington and Briggs1985), apparently with little capacity in most taxa for processing before its ingestion. Searching for prey calls for visual acuity, consistent with the large eyes of many radiodonts, and different kinds of mechanical action employed in sweeping, raking, or probing sediments of different grain sizes and consistency, potentially including those stabilized by bacterial mats. Arguments based largely on mechanical paradigms, but in some cases also on kinematic models, suggest roles for short, sharp, spike-like endites in piercing and gripping prey (Daley and Budd, Reference Daley and Budd2010; Bicknell et al., Reference Bicknell, Schmidt, Rahman, Edgecombe, Gutarra, Daley, Melzer, Wroe and Paterson2023). Alternation of long and short endites associated with successive podomeres is inferred to have played a role in grappling and manipulation of prey (De Vivo et al., Reference De Vivo, Lautenschlager and Vinther2021), although details of this action are still not yet well understood. Nets constituted by endites bearing short, fine, closely spaced auxiliary spines such as those of Tamisiocaris borealis have plausibly been interpreted as filters employed in suspension feeding, potentially well above the seafloor (Vinther et al., Reference Vinther, Stein, Longrich and Harper2014).

In the case of V. kerrymatti n. gen. n. sp., we have so far only the frontal appendage of the organism from which to draw inferences. We presume that in swimming and in its visual search for potential prey, its capacities were similar to those of the much better-known A. canadensis (Sheppard et al., Reference Sheppard, Rival and Caron2018). Given its long, thin endites, unequipped with auxiliary spines and without alternation in endite length, we infer that V. kerrymatti was not well equipped for piercing, grappling, or netting its prey. Consequently, we propose that V. kerrymatti is likely to have been adapted to cruise over the seafloor using its long, stiff endites as whisk brooms, sweeping away unconsolidated sediment in search of shallowly buried prey, much as do present-day stingrays by flapping their lateral fins. On having located a prey item, V. kerrymatti must necessarily have ingested it entirely by suction generated within its mouth. We envision a reciprocal process of sucking and slicing: as a worm-like animal was drawn into the mouth, it could have been serially cut into manageable pieces by constriction of the flat teeth surrounding the circumferential jaw as the “worm” was progressively drawn into the gullet. This hypothesis is potentially testable by future discovery of the oral cone of V. kerrymatti. If our hypothesis is correct, this oral cone is predicted to exhibit furrows between plates of the jaw such as those cited and illustrated by Daley and Bergström (Reference Daley and Bergström2012) as evidence for suction in Anomalocaris canadensis.

Conclusions

We have documented the form and taxonomic relationships of the previously undescribed radiodont species V. kerrymatti n. gen. n. sp. We have discussed its implications for both the existing classification of radiodont taxa and our understanding of patterns of evolutionary modification of radiodont frontal appendages. These considerations lead us to propose that V. kerrymatti extracted its likely worm-like prey from the seafloor and ingested them by suction. If this hypothesis is correct, this predator would likely have adventitiously ingested meiofaunal organisms that were living together with its prey in the sediment. In this case, it would have required only the evolutionary acquisition of fine, transverse auxiliary spines attached to its endites to shift the animal’s primary feeding adaptation from one kind of prey to the other. Hence, we infer that V. kerrymatti was potentially transitional in its feeding habits between those of bottom-feeding anomalocaridids and that of the mid-water suspension feeder Tamisiocaris borealis, as proposed by Oxman (Reference Oxman2014). As such, V. kerrymatti appears to have been a functional and evolutionary intermediary between members of the family Anomalocarididae and Tamisiocaris.

Acknowledgments

The land from which Verrocaris kerrymatti n. gen. n. sp. was collected lies in territory long populated by groups variously designated as the Lenni Lenape, Susquehannock, Conestoga, and Delaware peoples before their displacement by European colonists. We thank D.E.G. Briggs, J. Moysiuk, S. Pates, J. Vinther, two anonymous reviewers, and the editors for constructive advice from which this paper has much benefitted. We are grateful to P.J. Mehta and P. Mehta for their permission to study specimens collected by K. Matt on their property and to have the type specimen of Verrocaris kerrymatti deposited in the collection of the North Museum of Nature and Science. We thank M. Wolanski for her assistance and for access to specimens held by the North Museum and J.K. Nakano for help with loans of specimens from the U.S. National Museum. We thank E. Wilson and C. Hollinger for their assistance with photography, A. de Wet for providing our map, and S. Jha for help with Figure 4. We thank Franklin & Marshall College for financial and logistical support over many years, including our summer research as students. Copyrights: Figure 6.1, 6.2 from Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Fu, Ma and Lin2021a), their figure 2c, e, used with permission of Springer Nature BV; Figure 6.3, 6.4 from Vinther et al. (Reference Vinther, Stein, Longrich and Harper2014), their figures 1a and 2a, used with permission of Springer Nature BV; permission in both cases conveyed by the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Appendix

Data representing sizes and shapes of podomeres, illustrated by Figure 3.

H or W = height proximally and width distally, beyond the twist/fracture. See main text.

Data documenting relative endite lengths, illustrated by Figure 5 .

All measurements are recorded in centimeters.

Data for Verrocaris kerrymatti n. gen. n. sp.

For this one specimen, H represents height proximally and width, supposed not to differ greatly from height, distally, beyond the twist/fracture. See main text.

Data for Lenisicaris pennsylvanica

Data for Anomalocaris canadensis

Data for Shucaris ankylosskelos

Data for Houcaris saron (a)

Data for Houcaris saron (b)

Data for Echidnacaris briggsi

Data for Tamisiocaris borealis