1. Introduction

Flow around and downstream of two-dimensional (2-D) porous media has received significant attention due to its practical importance in engineering and environmental applications. From an engineering perspective, porous media offer enhanced aerodynamic properties, such as reductions in drag force (Klausmann & Ruck Reference Klausmann and Ruck2017; Geyer Reference Geyer2020), noise (Sato & Hattori Reference Sato and Hattori2021) and vortex-induced vibration (Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Laima, Gao, Chen and Li2021). These characteristics make porous media promising for passive flow control, with applications in the design of aircraft landing gear (Merino-Martínez et al. Reference Merino-Martínez, Kennedy and Bennett2021; Selivanov et al. Reference Selivanov, Silnikov, Markov, Popov and Pusev2021), high-speed train pantographs (Sueki, Ikeda & Takaishi Reference Sueki, Ikeda and Takaishi2009), subsea pipeline systems (Wen et al. Reference Wen, Jeng, Wang and Zhou2012) and unmanned aerial vehicle frames (Klippstein et al. Reference Klippstein, Hassanin, Diaz De Cerio Sanchez, Zweiri and Seneviratne2018). From an environmental perspective, emergent aquatic vegetation, modelled as arrays of 2-D circular cylinders, serves as an example of flows through porous media. Such vegetation plays a critical role in river ecosystems by providing habitats for aquatic organisms, improving water quality and influencing morphodynamic processes such as sedimentation and erosion (Gacia & Duarte Reference Gacia and Duarte2001; Bouma et al. Reference Bouma, Van Duren, Temmerman, Claverie, Blanco-Garcia, Ysebaert and Herman2007; Moore Reference Moore2009).

The flow characteristics of porous media, including wake manipulation, are primarily governed by bleeding flow, defined as the flow passing through the porous media. In 2-D porous configurations, bleeding occurs in both the longitudinal and lateral directions, typically characterized by the velocity at the trailing edge and along the lateral surfaces, respectively (Taddei, Manes & Ganapathisubramani Reference Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2016). These components interact to collectively modify the downstream flow structure (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Zeng, Lee, Bai and Low2010; Nicolle & Eames Reference Nicolle and Eames2011; Cummins et al. Reference Cummins, Viola, Mastropaolo and Nakayama2017; Ledda et al. Reference Ledda, Siconolfi, Viola, Gallaire and Camarri2018). For instance, longitudinal bleeding has been shown to reduce the size of recirculation bubbles, displace them downstream, weaken shear layer intensity and shift the shear layer convergence point farther downstream (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Ortiz, Zong and Nepf2012; Zong & Nepf Reference Zong and Nepf2012; Tang et al. Reference Tang, Yu, Shan and Chen2019). In contrast, lateral bleeding increases the boundary-layer thickness along the side of the porous body by reducing the streamwise momentum of the external flow and vertically displacing the shear layer away from the wake core (Nicolai et al. Reference Nicolai, Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2020; Seol, Kim & Kim Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024). These flow manipulation mechanisms are governed by the bleeding flux, which is intrinsically linked to the porosity and permeability of the porous medium.

Although porosity and permeability are interdependent, most experimental studies have treated porosity as the primary control parameter for bleeding, due to its ease of manipulation (Zong & Nepf Reference Zong and Nepf2012; Tang et al. Reference Tang, Yu, Shan and Chen2019; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Blois, Best and Christensen2020; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Chang, Yu, Chen and Gao2022; Cicolin et al. Reference Cicolin, Chellini, Usherwood, Ganapathisubramani and Castro2024; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Best, Christensen and Blois2025). For example, Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Chang, Yu, Chen and Gao2022) demonstrated experimentally that increasing the porosity of circular cylinders suppressed vortex shedding and reduced drag at high Reynolds numbers (

![]() $ \textit{Re}=2.02\times 10^4$

,

$ \textit{Re}=2.02\times 10^4$

,

![]() $ \textit{Re}=U_eD/\nu$

, where

$ \textit{Re}=U_eD/\nu$

, where

![]() $U_e$

is the upstream velocity,

$U_e$

is the upstream velocity,

![]() $D$

is the cylinder width and

$D$

is the cylinder width and

![]() $\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity). Similarly, Cicolin et al. (Reference Cicolin, Chellini, Usherwood, Ganapathisubramani and Castro2024) reported that higher porosity in rectangular porous plates weakened shear layers, resulting in more diffuse vortices and reduced shedding intermittency. Zong & Nepf (Reference Zong and Nepf2012) further examined the effect of porosity on wake development using patches of 2-D circular cylinders. Their results showed that longitudinal bleeding occurs in the region between shear layers and becomes stronger with increasing patch porosity, shifting the shear layer convergence point farther downstream. This finding highlights the crucial role of longitudinal bleeding in shaping the wake, particularly through its influence on shear layer interactions and velocity recovery in the near wake.

$\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity). Similarly, Cicolin et al. (Reference Cicolin, Chellini, Usherwood, Ganapathisubramani and Castro2024) reported that higher porosity in rectangular porous plates weakened shear layers, resulting in more diffuse vortices and reduced shedding intermittency. Zong & Nepf (Reference Zong and Nepf2012) further examined the effect of porosity on wake development using patches of 2-D circular cylinders. Their results showed that longitudinal bleeding occurs in the region between shear layers and becomes stronger with increasing patch porosity, shifting the shear layer convergence point farther downstream. This finding highlights the crucial role of longitudinal bleeding in shaping the wake, particularly through its influence on shear layer interactions and velocity recovery in the near wake.

Despite these experimental advances, previous studies have not explicitly established a direct relationship between porosity and the aerodynamic or wake characteristics of porous bluff bodies. This limitation stems from the intrinsic coupling between porosity and permeability. While porosity quantifies the void fraction, it is permeability that characterizes the resistance to internal flow and more directly controls the bleeding flux through the medium.

In contrast to porosity, permeability has often been systemically varied in numerical studies, particularly through macroscopic frameworks such as the Darcy–Brinkman–Forchheimer (DBF) model (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Zeng, Lee, Bai and Low2010; Cummins et al. Reference Cummins, Viola, Mastropaolo and Nakayama2017; Ledda et al. Reference Ledda, Siconolfi, Viola, Gallaire and Camarri2018) or homogenization-based approach (Mei & Auriault Reference Mei and Auriault1991; Zampogna & Bottaro Reference Zampogna and Bottaro2016). In DBF-based studies of 2-D porous configurations, the Darcy number (

![]() $ \textit{Da}=K/D^2$

, where

$ \textit{Da}=K/D^2$

, where

![]() $K$

is the physical permeability and

$K$

is the physical permeability and

![]() $D$

denotes the cylinder diameter) is commonly used to characterize the degree of flow blockage and its effect on the flow field. For instance, Yu et al. (Reference Yu, Zeng, Lee, Bai and Low2010) performed finite-volume simulations to investigate flow past porous square cylinders over a wide range of Darcy numbers (

$D$

denotes the cylinder diameter) is commonly used to characterize the degree of flow blockage and its effect on the flow field. For instance, Yu et al. (Reference Yu, Zeng, Lee, Bai and Low2010) performed finite-volume simulations to investigate flow past porous square cylinders over a wide range of Darcy numbers (

![]() $10^{-6}\lt Da\lt 10^{-1}$

). Their study revealed strong correlations between permeability and wake structure. Cummins et al. (Reference Cummins, Viola, Mastropaolo and Nakayama2017) conducted direct numerical simulations (DNS) at low Reynolds numbers (

$10^{-6}\lt Da\lt 10^{-1}$

). Their study revealed strong correlations between permeability and wake structure. Cummins et al. (Reference Cummins, Viola, Mastropaolo and Nakayama2017) conducted direct numerical simulations (DNS) at low Reynolds numbers (

![]() $1\lt \textit{Re} \lt 130$

) and identified distinct flow regimes, characterized by changes in recirculation patterns as a function of

$1\lt \textit{Re} \lt 130$

) and identified distinct flow regimes, characterized by changes in recirculation patterns as a function of

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

. Similarly, Ledda et al. (Reference Ledda, Siconolfi, Viola, Gallaire and Camarri2018) showed that the drag coefficient (

$ \textit{Da} $

. Similarly, Ledda et al. (Reference Ledda, Siconolfi, Viola, Gallaire and Camarri2018) showed that the drag coefficient (

![]() $C_{\kern-1pt D}$

) depends on both

$C_{\kern-1pt D}$

) depends on both

![]() $ \textit{Re} $

and

$ \textit{Re} $

and

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

, highlighting the dominant role of permeability in wake dynamics.

$ \textit{Da} $

, highlighting the dominant role of permeability in wake dynamics.

Beyond these macroscopic approaches, recent studies have employed pore-resolved simulations to investigate flow behaviour near the porous interface (Nair et al. Reference Nair, Kazemi, Curet and Verma2023; He et al. Reference He, An, Ghisalberti, Draper, Ren, Branson and Cheng2024). These works showed that the internal arrangement of solid elements within a fixed-porosity matrix strongly influence drag, vortex formation and wake recirculation even when porosity remains constant. In particular, Nair et al. (Reference Nair, Kazemi, Curet and Verma2023) observed that vorticity production is highly sensitive to the local configuration of internal structures. He et al. (Reference He, An, Ghisalberti, Draper, Ren, Branson and Cheng2024) further confirmed that a change in internal arrangement geometry can significantly affect drag and bleeding behaviour.

Despite these contributions, a major limitation of both macroscopic and pore-resolved numerical studies is their predominant focus on low Reynolds number regimes (

![]() $ \textit{Re}\sim O(10^2)$

). Consequently, the influence of permeability on bleeding characteristics at high Reynolds numbers remains poorly understood. This knowledge gap poses a significant challenge to developing a comprehensive understanding of flow past porous media and limits the assessment of their feasibility in practical applications.

$ \textit{Re}\sim O(10^2)$

). Consequently, the influence of permeability on bleeding characteristics at high Reynolds numbers remains poorly understood. This knowledge gap poses a significant challenge to developing a comprehensive understanding of flow past porous media and limits the assessment of their feasibility in practical applications.

To address this challenge, our recent experimental studies introduced a novel design of porous structures based on a uniform and scalable simple cubic lattice (Seol et al. Reference Seol, Hong and Kim2023, Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024). This design enables independent control of permeability while maintaining constant porosity, made possible through high-resolution three-dimensional (3-D) printing. This approach facilitated the first experimental study of permeability effects on flow past porous square cylinders over a wide range of Darcy numbers (

![]() $2.4\times 10^{-5}\lt Da\lt 2.9\times 10^{-3}$

) at a high Reynolds number (

$2.4\times 10^{-5}\lt Da\lt 2.9\times 10^{-3}$

) at a high Reynolds number (

![]() $ \textit{Re} = 3.1\times 10^4$

). In particular, Seol et al. (Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024) demonstrated that the interaction between longitudinal and lateral bleeding significantly alters the shear layers and associated wake structures, depending on

$ \textit{Re} = 3.1\times 10^4$

). In particular, Seol et al. (Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024) demonstrated that the interaction between longitudinal and lateral bleeding significantly alters the shear layers and associated wake structures, depending on

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

. They further identified four distinct flow regimes downstream of porous square cylinders, each corresponding to a different range of Darcy numbers. These findings highlight the critical role of permeability in shaping wake topology and governing bleeding flow characteristics.

$ \textit{Da} $

. They further identified four distinct flow regimes downstream of porous square cylinders, each corresponding to a different range of Darcy numbers. These findings highlight the critical role of permeability in shaping wake topology and governing bleeding flow characteristics.

Building on the structural features of longitudinal bleeding observed in Seol et al. (Reference Seol, Hong and Kim2023, Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024), we note that the downstream evolution of the longitudinal bleeding, originating from an array of pores, is analogous to that of parallel plane jets, wherein multiple shear layers develop and eventually merge. This structural similarity motivates a conceptual model of longitudinal bleeding as a quasi-2-D jet, which itself shares characteristics with the far wake of a solid cylinder (Bradbury Reference Bradbury1965). As a result, for 2-D porous cylinders with uniform and periodic internal geometry, we hypothesize that the longitudinal jets issuing from individual pores can be interpreted within the framework of multiple plane jets, where the interaction between adjacent shear layers governs the downstream flow evolution in the presence of an external flow. In other words, the flow behind porous square cylinders can be understood by integrating two distinct structural behaviours: quasi-2-D jet-like structures in the near wake and turbulent boundary-layer-like flow in the far wake.

In classical multiple plane jet configurations, individual jets undergo a merging and combining process in the near wake, eventually evolving into a single jet-like structure as they develop downstream (Tanaka Reference Tanaka1974; Nasr & Lai Reference Nasr and Lai1997; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Aleyasin, Biswas and Tachie2020). The merging region refers to the initial zone in which distinct jets begin to interact and redistribute momentum. Beyond this, in the combined region, the jets have fully coalesced into a single structure, where the flow evolves primarily through lateral diffusion and momentum decay (Miller & Comings Reference Miller and Comings1960; Zhao & Wang Reference Zhao and Wang2018).

The structural development of multiple plane jets is known to depend strongly on nozzle configuration, such as spacing (Tanaka Reference Tanaka1970; Tanaka & Nakata Reference Tanaka and Nakata1975) and nozzle orientation (Morris et al. Reference Morris, Aleyasin, Biswas and Tachie2020). While the fully combined region resembles a canonical turbulent plane jet in structure, its overall momentum and turbulence intensity often differ, depending on jet configuration (Tanaka Reference Tanaka1974; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Aleyasin, Biswas and Tachie2020). In particular, the presence of a central jet plays a critical role in flow development, leading to the classification of dual jets (no central jet) and triple jets (with a central jet) as canonical configurations for studying jet interactions. For example, dual jets are characterized by inward entrainment towards the centreline, driven by a low-pressure region between the side jets (Tanaka Reference Tanaka1970, Reference Tanaka1974; Nasr & Lai Reference Nasr and Lai1997). In contrast, triple jets exhibit enhanced lateral momentum diffusion due to the merging of the central jet with adjacent side jets (Tanaka & Nakata Reference Tanaka and Nakata1975; Nouali & Mataoui Reference Nouali and Mataoui2016; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Aleyasin, Biswas and Tachie2020). This distinction is particularly relevant to the structured porous cylinders considered in the present study. Specifically, the arrangement of lattice pores at the trailing edge may lead to wake structures resembling either dual- or triple-jet-like configurations. Consequently, the presence or absence of a central pore plays a significant role in determining the structural characteristics of bleeding flows.

From the perspective of the boundary-layer framework, Bradbury (Reference Bradbury1965) showed that, in the far field of a turbulent plane jet, the flow becomes self-similar. This indicates that velocity profiles collapse onto a universal shape when appropriately scaled. This self-similarity arises because, at a sufficient distance downstream, the effect of initial conditions at the jet exit diminishes. In this regime, the jet spreads at a predictable rate with a characteristic decay in centreline velocity, a condition referred to as the boundary-layer assumption.

More recently, this assumption has been extended from canonical plane jets to porous bluff-body wakes. For instance, Nicolai et al. (Reference Nicolai, Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2020) experimentally investigated the wake of a wall-mounted porous patch composed of an array of circular cylinders, fully immersed in a turbulent boundary layer. Despite the inherent three-dimensionality and wall interference in their configuration, they observed that beyond the immediate near-wake region (approximately 1

![]() ${-}$

2 patch diameters downstream), the velocity deficit profiles evolved towards a self-similar form. These results suggest that the wake transitions into a shear-layer-dominated state, where the boundary layer assumption becomes asymptotically valid, even in geometrically complex, wall-bounded environments.

${-}$

2 patch diameters downstream), the velocity deficit profiles evolved towards a self-similar form. These results suggest that the wake transitions into a shear-layer-dominated state, where the boundary layer assumption becomes asymptotically valid, even in geometrically complex, wall-bounded environments.

Based on our recent study (Seol et al. Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024), this work reports the first experimental investigation into the structural characteristics of longitudinal bleeding jets downstream of porous square cylinders, with a focus on the effect of cylinder permeability and pore configuration. In particular, the behaviour of longitudinal bleeding is interpreted within the framework of turbulent plane jets under the influence of an external flow. Furthermore, an analytical model is developed to predict the key dynamics of bleeding flow evolution, formulated by integrating the momentum equation with the DBF model and the boundary-layer assumption. To this end, we fabricated porous square cylinders composed of a periodic and scalable simple cubic lattice structure using high-resolution 3-D printing. This unique design, initially proposed in our earlier work (Seol, Hong & Kim Reference Seol, Hong and Kim2023), enables the independent control of permeability and porosity. A comprehensive set of experiments was conducted over a broad range of Darcy numbers, using particle image velocimetry (PIV) to systematically investigate the impact of permeability and pore configuration on the longitudinal bleeding flow and the corresponding wake dynamics.

The DBF model effectively captures flow dynamics both within and around porous media based on the macroscopic effects of viscosity, inertia and permeability. In this regard, the DBF model has been widely used in numerical simulations of flow around porous bluff bodies, particularly at low Reynolds numbers (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Zeng, Lee, Bai and Low2010; Cummins et al. Reference Cummins, Viola, Mastropaolo and Nakayama2017; Ledda et al. Reference Ledda, Siconolfi, Viola, Gallaire and Camarri2018). More recently, the DBF model has been extended to high-Reynolds-number flows in both experimental and computational studies with thorough validations (Seol et al. Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024; Hao & García-Mayoral Reference Hao and García-Mayoral2025).

For example, Seol et al. (Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024) demonstrated the successful application of a DBF-based analytical model in characterizing the streamwise flow adjustment behind porous square cylinders for

![]() $ \textit{Re}\approx 3.1\times 10^4$

. Their analytical model captured the permeability-induced source terms and predicted the flow adjustment length across a wide range of Darcy numbers (

$ \textit{Re}\approx 3.1\times 10^4$

. Their analytical model captured the permeability-induced source terms and predicted the flow adjustment length across a wide range of Darcy numbers (

![]() $10^{-5}\lt Da\lt 10^{-3}$

). Their model predictions were in close agreement with experimental data from PIV measurements. This result indicates that the DBF model remains valid when used to capture macroscopic momentum loss associated with porous media under turbulent conditions. Moreover, the recent DNS study by Hao & García-Mayoral (Reference Hao and García-Mayoral2025) provides further theoretical and computational justification. In this work, they investigated turbulent channel flows over porous substrates with Reynolds numbers up to

$10^{-5}\lt Da\lt 10^{-3}$

). Their model predictions were in close agreement with experimental data from PIV measurements. This result indicates that the DBF model remains valid when used to capture macroscopic momentum loss associated with porous media under turbulent conditions. Moreover, the recent DNS study by Hao & García-Mayoral (Reference Hao and García-Mayoral2025) provides further theoretical and computational justification. In this work, they investigated turbulent channel flows over porous substrates with Reynolds numbers up to

![]() $ \textit{Re}_\tau \approx 550$

(

$ \textit{Re}_\tau \approx 550$

(

![]() $ \textit{Re}_\tau = u_\tau h/\nu$

, where

$ \textit{Re}_\tau = u_\tau h/\nu$

, where

![]() $u_\tau$

and

$u_\tau$

and

![]() $h$

are the friction velocity and the channel half-height, respectively). Particularly, they employed analytical solutions to the Darcy–Brinkman equation to estimate the permeability-dependent shear penetration and subsurface velocity field. These solutions served as boundary conditions for the overlying DNS. They were found to be in good agreement with the simulated near-interface velocity fields. Their analysis confirms that the Darcy–Brinkman model provides a physically consistent framework for representing bulk momentum transport and interface conditions even in wall-bounded turbulent flows.

$h$

are the friction velocity and the channel half-height, respectively). Particularly, they employed analytical solutions to the Darcy–Brinkman equation to estimate the permeability-dependent shear penetration and subsurface velocity field. These solutions served as boundary conditions for the overlying DNS. They were found to be in good agreement with the simulated near-interface velocity fields. Their analysis confirms that the Darcy–Brinkman model provides a physically consistent framework for representing bulk momentum transport and interface conditions even in wall-bounded turbulent flows.

Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to characterize the evolution of longitudinal bleeding flow with respect to permeability and pore configuration. First, we investigate how permeability alters wake topology to establish its role in governing downstream flow structures. Next, we assess structural variation in longitudinal bleeding induced by changes in permeability and pore arrangement, leading to a refined description of jet merging and decay processes. Particularly, this work presents the first experimental evidence that longitudinal bleeding can be modelled as interacting multiple plane jets, providing a new conceptual framework for interpreting porous-body wakes. Finally, we proposed a new analytical model to predict the merging length of longitudinal bleeding jets, explicitly incorporating permeability as a governing parameter, and validated the model against experimental data. This analytical approach extends the applicability of DBF-based models to jet-interaction regimes not previously addressed in porous media flow studies.

2. Experiments

2.1. Cylinder models

The porous cylinders investigated in this study utilize a simple cubic lattice structure characterized by the unit cell length (

![]() $d_1$

) and the strut width (

$d_1$

) and the strut width (

![]() $d_2$

). As depicted in figure 1(a), this lattice design ensures isotropic permeability, with its porosity (

$d_2$

). As depicted in figure 1(a), this lattice design ensures isotropic permeability, with its porosity (

![]() $\varPhi$

) determined by the ratio of

$\varPhi$

) determined by the ratio of

![]() $d_2$

to

$d_2$

to

![]() $d_1$

in a unit cell as

$d_1$

in a unit cell as

Figure 1. (a) Simple cubic lattice structure serving as a base porous structure; (b) schematic representation illustrating of decoupling process of permeability (

![]() $K$

) from porosity (

$K$

) from porosity (

![]() $\varPhi$

); (c) dimensions of the porous square cylinder utilized in the experiments; (d) sample images of the porous square cylinders with different designs; detailed design parameters outlined in the schematic cross-sections for (e) case A3 and (f) case A5 (see table 1).

$\varPhi$

); (c) dimensions of the porous square cylinder utilized in the experiments; (d) sample images of the porous square cylinders with different designs; detailed design parameters outlined in the schematic cross-sections for (e) case A3 and (f) case A5 (see table 1).

A key feature of this design is that while porosity remains constant (i.e. constant

![]() $d_2/d_1$

), decreasing

$d_2/d_1$

), decreasing

![]() $d_1$

leads to a reduction in permeability (

$d_1$

leads to a reduction in permeability (

![]() $K$

), thereby enabling the decoupling of permeability effect from those of porosity (see figure 1

b). This experimental configuration allows for a controlled investigation of permeability-driven flow phenomena, which have predominantly been explored though computational studies due to the challenges associated with independently varying permeability in experimental settings. Within this unit-cell design, the pore-to-pore spacing equals the lattice length

$K$

), thereby enabling the decoupling of permeability effect from those of porosity (see figure 1

b). This experimental configuration allows for a controlled investigation of permeability-driven flow phenomena, which have predominantly been explored though computational studies due to the challenges associated with independently varying permeability in experimental settings. Within this unit-cell design, the pore-to-pore spacing equals the lattice length

![]() $d_1$

. Accordingly, at fixed porosity

$d_1$

. Accordingly, at fixed porosity

![]() $\varPhi$

, varying permeability

$\varPhi$

, varying permeability

![]() $K$

by uniform unit-cell scaling necessarily changes the spacing in proportion. Jet spacing is thus not treated as an independent control parameter in this study. Its influence is accounted for implicitly through the scale-separation parameter

$K$

by uniform unit-cell scaling necessarily changes the spacing in proportion. Jet spacing is thus not treated as an independent control parameter in this study. Its influence is accounted for implicitly through the scale-separation parameter

![]() $\epsilon =d_1/D$

(Mei & Auriault Reference Mei and Auriault1991; Zampogna & Bottaro Reference Zampogna and Bottaro2016), as discussed in §§ 3.1–3.2. The precise fabrication of these geometries was achieved using advanced stereolithography 3-D printing techniques, ensuring high resolution and surface quality.

$\epsilon =d_1/D$

(Mei & Auriault Reference Mei and Auriault1991; Zampogna & Bottaro Reference Zampogna and Bottaro2016), as discussed in §§ 3.1–3.2. The precise fabrication of these geometries was achieved using advanced stereolithography 3-D printing techniques, ensuring high resolution and surface quality.

In this study, 2-D square cylinders were chosen due to their alignment with the Cartesian coordinate system. Compared with cylinders with circular cross-sections, 2-D square cylinders with rectangular cross-sections are better suited for manipulating permeability due to their tensor nature. For simplicity, the aspect ratio of the rectangular cross-section was set to unity, resulting in square cylinders. Additionally, it is worth noting that the pore configuration of the porous cylinders can vary between odd and even numbers of pores along the cylinder width (

![]() $D$

), as illustrated in figure 1(e) and 1(f). These specific configurations play a crucial role in the behaviour of longitudinal bleedings near the trailing edge and their downstream structural evolution, depending on whether a central pore aligns with the lateral centreline (Seol et al. Reference Seol, Hong and Kim2023). For clarity, we refer to these configurations as the odd and even cases, respectively. All cylinders, both porous and solid, were fabricated using an advanced stereolithography 3-D printer (Anycubic Photon Mono X), with a width

$D$

), as illustrated in figure 1(e) and 1(f). These specific configurations play a crucial role in the behaviour of longitudinal bleedings near the trailing edge and their downstream structural evolution, depending on whether a central pore aligns with the lateral centreline (Seol et al. Reference Seol, Hong and Kim2023). For clarity, we refer to these configurations as the odd and even cases, respectively. All cylinders, both porous and solid, were fabricated using an advanced stereolithography 3-D printer (Anycubic Photon Mono X), with a width

![]() $D$

of 40 mm (or 42 mm) and a length of 320 mm, as depicted in figure 1(c). Detailed specifications of each cylinder are provided in table 1 and further discussed in previous studies (Seol et al. Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024).

$D$

of 40 mm (or 42 mm) and a length of 320 mm, as depicted in figure 1(c). Detailed specifications of each cylinder are provided in table 1 and further discussed in previous studies (Seol et al. Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024).

2.2. Permeability measurements

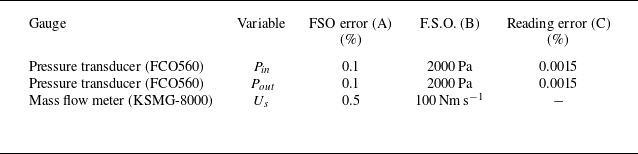

Permeability measurements were carried out in a 3.5 m-long acrylic pipe with an internal diameter of 65 mm, as shown in figure 2(a). Porous disks with the same lattice structure used in this study were fabricated via 3-D printing. To ensure that the maximum pressure drop did not exceed 2000 Pa at a superficial velocity (

![]() $U_s$

) of 15 m s−1, the thickness of the disks was varied between 20 and 60 mm. The disks were securely mounted 1.2 m downstream from the inlet to guarantee a fully developed flow. Pressure drop (

$U_s$

) of 15 m s−1, the thickness of the disks was varied between 20 and 60 mm. The disks were securely mounted 1.2 m downstream from the inlet to guarantee a fully developed flow. Pressure drop (

![]() $\Delta{\kern-1pt}P$

) across the disks was measured using a high-resolution differential pressure transmitter (FCO560, Furness Control) with a sampling rate of 1 kHz over a 2 min period, using pressure taps placed before and after the disks. At a distance of 0.4 m from the outlet, the superficial velocity (

$\Delta{\kern-1pt}P$

) across the disks was measured using a high-resolution differential pressure transmitter (FCO560, Furness Control) with a sampling rate of 1 kHz over a 2 min period, using pressure taps placed before and after the disks. At a distance of 0.4 m from the outlet, the superficial velocity (

![]() $U_s$

) was measured using a thermal mass flow meter (KSMG-8000, pressure and temperature compensated) over the same 2 min period, with

$U_s$

) was measured using a thermal mass flow meter (KSMG-8000, pressure and temperature compensated) over the same 2 min period, with

![]() $U_s$

ranging from 0.15 to 15 m s−1. By plotting

$U_s$

ranging from 0.15 to 15 m s−1. By plotting

![]() $\Delta{\kern-1pt}P$

against

$\Delta{\kern-1pt}P$

against

![]() $U_s$

for all the porous samples, the permeability (

$U_s$

for all the porous samples, the permeability (

![]() $K$

) was determined by fitting the data to the Forchheimer equation (Dukhan & Minjeur Reference Dukhan and Minjeur2011). The resulting permeability (

$K$

) was determined by fitting the data to the Forchheimer equation (Dukhan & Minjeur Reference Dukhan and Minjeur2011). The resulting permeability (

![]() $K$

) and the corresponding non-dimensional Darcy numbers (

$K$

) and the corresponding non-dimensional Darcy numbers (

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

) are listed in table 1.

$ \textit{Da} $

) are listed in table 1.

Figure 2. Experimental set-up for (a) permeability measurements, featuring sample porous disks and associated equipment, including a thermal mass flow meter, differential pressure transmitter and pressure taps for

![]() $\Delta{\kern-1pt}P$

measurement; (b) PIV measurements using two PIV cameras arranged in tandem; (c) schematic representation of the field of view (FoV) for PIV measurements, with the darker shaded area in the middle indicating the overlap between the two fields of view.

$\Delta{\kern-1pt}P$

measurement; (b) PIV measurements using two PIV cameras arranged in tandem; (c) schematic representation of the field of view (FoV) for PIV measurements, with the darker shaded area in the middle indicating the overlap between the two fields of view.

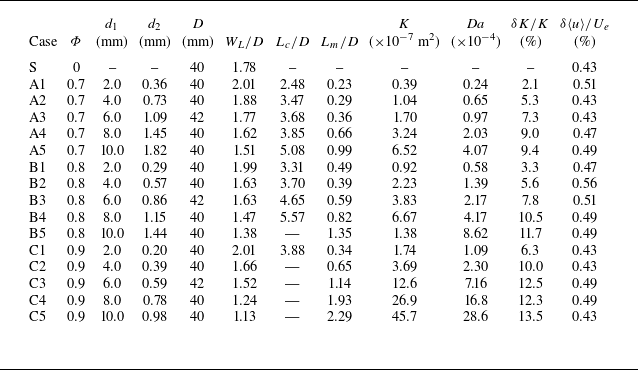

Table 1. Parameters for the structured porous square cylinders:

![]() $\varPhi$

, porosity;

$\varPhi$

, porosity;

![]() $d_1$

, length of the unit cell;

$d_1$

, length of the unit cell;

![]() $d_2$

, strut width;

$d_2$

, strut width;

![]() $D$

, cylinder width;

$D$

, cylinder width;

![]() $W_L$

, lateral wake extent;

$W_L$

, lateral wake extent;

![]() $L_{c}$

and

$L_{c}$

and

![]() $L_m$

, longitudinal extent of combined and merging region, respectively;

$L_m$

, longitudinal extent of combined and merging region, respectively;

![]() $K$

, permeability;

$K$

, permeability;

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

, Darcy number;

$ \textit{Da} $

, Darcy number;

![]() $\delta K/K$

, relative total uncertainty in permeability;

$\delta K/K$

, relative total uncertainty in permeability;

![]() $\delta \langle u \rangle / U_e$

: relative total uncertainty in mean longitudinal velocity.

$\delta \langle u \rangle / U_e$

: relative total uncertainty in mean longitudinal velocity.

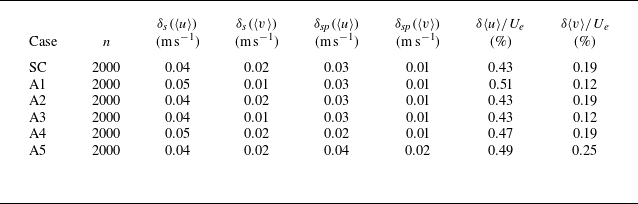

2.3. The PIV measurements

Particle image velocimetry was employed to assess the flow behaviour for all cylinder cases at an upstream velocity of 11.5 m s−1 (corresponding to

![]() $ \textit{Re} \approx 3.1 \times 10^4$

). The free stream turbulence intensity in the test section was less than 0.8

$ \textit{Re} \approx 3.1 \times 10^4$

). The free stream turbulence intensity in the test section was less than 0.8

![]() $\,\%$

over the velocity range

$\,\%$

over the velocity range

![]() $3{-}20$

m s−1, as reported previously for the same facility (Seol et al. Reference Seol, Hong and Kim2023). The operating condition of the present measurements lies within this range. Measurements were taken at two downstream positions in the

$3{-}20$

m s−1, as reported previously for the same facility (Seol et al. Reference Seol, Hong and Kim2023). The operating condition of the present measurements lies within this range. Measurements were taken at two downstream positions in the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $y$

plane to capture the extended wake structures, using two 12 MP TSI Powerview cameras (

$y$

plane to capture the extended wake structures, using two 12 MP TSI Powerview cameras (

![]() $4k \times 3k$

, eight-bit) fitted with 105 mm Nikkor lenses. These cameras provided a FoV of

$4k \times 3k$

, eight-bit) fitted with 105 mm Nikkor lenses. These cameras provided a FoV of

![]() $6D \times 3D$

(figure 2

a,b). A Quantel Evergreen Nd:YAG double-pulsed laser (200 mJ per pulse) was used to generate a 1 mm-thick laser sheet, and data were acquired at a frequency of 5 Hz for all cases. For each cylinder case, 2000 independent image pairs were recorded. The final interrogation window size was 32

$6D \times 3D$

(figure 2

a,b). A Quantel Evergreen Nd:YAG double-pulsed laser (200 mJ per pulse) was used to generate a 1 mm-thick laser sheet, and data were acquired at a frequency of 5 Hz for all cases. For each cylinder case, 2000 independent image pairs were recorded. The final interrogation window size was 32

![]() $\times$

32 pixels with 50

$\times$

32 pixels with 50

![]() $\,\%$

overlap, resulting in a grid resolution of 890

$\,\%$

overlap, resulting in a grid resolution of 890

![]() $ \unicode{x03BC}\rm m$

. Considering the random error in PIV measurements, which results from both sampling error in the turbulent velocity signal and the subpixel accuracy of the PIV system, the total random error in the mean velocity for the current measurements is estimated to be

$ \unicode{x03BC}\rm m$

. Considering the random error in PIV measurements, which results from both sampling error in the turbulent velocity signal and the subpixel accuracy of the PIV system, the total random error in the mean velocity for the current measurements is estimated to be

![]() $\pm 0.05$

m s−1. This corresponds to an uncertainty of 0.1

$\pm 0.05$

m s−1. This corresponds to an uncertainty of 0.1

![]() $\,\%$

when normalized by the free stream velocity (

$\,\%$

when normalized by the free stream velocity (

![]() $U_e$

). For further details on permeability and PIV measurements, readers are referred to our previous studies (Seol et al. Reference Seol, Hong and Kim2023, Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024).

$U_e$

). For further details on permeability and PIV measurements, readers are referred to our previous studies (Seol et al. Reference Seol, Hong and Kim2023, Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Downstream wake topology

Since the velocity deficit serves as a useful indicator of the downstream wake topology behind bluff bodies, we computed the velocity deficit, which is defined as the difference between the incoming mean flow and the mean longitudinal velocity around the porous cylinders,

![]() $(U_e- \langle u\rangle )/U_e$

. Figure 3 displays selected contour maps of the velocity deficit alongside a schematic representation of the porous cylinders at the origin. This facilitates in understanding the cross-section of the cylinder and the effect of permeability. For a baseline of comparison, a solid case is included to highlight the influence of permeability on the downstream wake topology. The coordinate system is normalized by the cylinder width,

$(U_e- \langle u\rangle )/U_e$

. Figure 3 displays selected contour maps of the velocity deficit alongside a schematic representation of the porous cylinders at the origin. This facilitates in understanding the cross-section of the cylinder and the effect of permeability. For a baseline of comparison, a solid case is included to highlight the influence of permeability on the downstream wake topology. The coordinate system is normalized by the cylinder width,

![]() $D$

.

$D$

.

Figure 3. Selected contour maps of the normalized velocity deficit,

![]() $(U_e - \langle u \rangle )/U_e$

, illustrating the wake topology behind the cylinders. Panels (

$(U_e - \langle u \rangle )/U_e$

, illustrating the wake topology behind the cylinders. Panels (

![]() $a$

)–(

$a$

)–(

![]() $f$

) depict the variation in velocity deficit behaviour with increasing Darcy number (

$f$

) depict the variation in velocity deficit behaviour with increasing Darcy number (

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

).

$ \textit{Da} $

).

Figure 3 illustrates the evolution of the velocity deficit with increasing

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

, which highlights the main flow features influenced by the permeable nature of the cylinders. A representative subset of configurations (S, A1, B2, A4, B5, C5) is shown to span the tested

$ \textit{Da} $

, which highlights the main flow features influenced by the permeable nature of the cylinders. A representative subset of configurations (S, A1, B2, A4, B5, C5) is shown to span the tested

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

range and to sample both odd and even pore arrangements. The remaining cases exhibit similar trends and are omitted here for clarity. It should be noted that in figure 3 contour levels less than 0.5 were omitted to clearly identify the downstream wake topology imposed by the current porous cylinders. This means that at the edge of the coloured regions in the contour maps, the streamwise velocity has recovered 50

$ \textit{Da} $

range and to sample both odd and even pore arrangements. The remaining cases exhibit similar trends and are omitted here for clarity. It should be noted that in figure 3 contour levels less than 0.5 were omitted to clearly identify the downstream wake topology imposed by the current porous cylinders. This means that at the edge of the coloured regions in the contour maps, the streamwise velocity has recovered 50

![]() $\,\%$

of its undisturbed value upstream of the cylinders.

$\,\%$

of its undisturbed value upstream of the cylinders.

As shown in figure 3, the velocity deficit and its spatial evolution behind the cylinders are clearly dictated by the permeability and the characteristics of the bleedings through the porous structure. Even with the smallest permeability (i.e.

![]() $ \textit{Da}=2.44 \times 10^{-5}$

) considered in this study (see figure 3

b), the downstream wake structure is significantly altered compared with the solid case shown in figure 3(a). Specifically, the overall shape of the wake becomes elongated in both longitudinal and lateral directions due to the presence of bleeding flows in these directions, featuring a smaller magnitude of velocity deficit near the porous-fluid interface compared with the solid case. With increasing

$ \textit{Da}=2.44 \times 10^{-5}$

) considered in this study (see figure 3

b), the downstream wake structure is significantly altered compared with the solid case shown in figure 3(a). Specifically, the overall shape of the wake becomes elongated in both longitudinal and lateral directions due to the presence of bleeding flows in these directions, featuring a smaller magnitude of velocity deficit near the porous-fluid interface compared with the solid case. With increasing

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

, the downstream wake topology is remarkably modified, as shown in figure 3(c–f). The lateral extent of the wake appears to decrease, and the magnitude of velocity deficit diminishes with increasing

$ \textit{Da} $

, the downstream wake topology is remarkably modified, as shown in figure 3(c–f). The lateral extent of the wake appears to decrease, and the magnitude of velocity deficit diminishes with increasing

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

. This observation is consistent with the findings of Nicolai et al. (Reference Nicolai, Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2020), reporting similar trends in flows through cylinder arrays at high Reynolds numbers (

$ \textit{Da} $

. This observation is consistent with the findings of Nicolai et al. (Reference Nicolai, Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2020), reporting similar trends in flows through cylinder arrays at high Reynolds numbers (

![]() $ \textit{Re} = 1.3\times 10^5$

). This topological change in the wake is due to the fact that the higher permeability allows more fluid to pass through the porous cylinder, reducing the momentum deficit and resulting in a structural alteration of the downstream wake (Taddei et al. Reference Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2016).

$ \textit{Re} = 1.3\times 10^5$

). This topological change in the wake is due to the fact that the higher permeability allows more fluid to pass through the porous cylinder, reducing the momentum deficit and resulting in a structural alteration of the downstream wake (Taddei et al. Reference Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2016).

Furthermore, the dependence of lateral wake extent on permeability observed here is in close agreement with previous studies of porous plates at lower Reynolds numbers. For example, Castro (Reference Castro1971) reported that increasing longitudinal bleeding through porous plates leads to a reduction in the lateral wake width, which is a consistent pattern with the present results. Similarly, Steiros, Bempedelis & Ding (Reference Steiros, Bempedelis and Ding2021) provided both theoretical and experimental analysis of wakes behind porous plates, showing that increased longitudinal bleeding reduces wake width by weakening the momentum deficit in the wake region. Their results indicated that the reduction in wake width results from attenuated velocity gradients across the shear layer, reducing downstream wake entrainment and suppressing lateral wake growth. This mechanism has also been supported in other studies involving porous geometries (Zong & Nepf Reference Zong and Nepf2012; Taddei et al. Reference Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2016; Ciuti et al. Reference Ciuti, Zampogna, Gallaire, Camarri and Ledda2021). The current results in figure 3 exhibit a similar structural trend, supporting the notion that enhanced permeability mitigates the momentum deficit and effectively reduces the lateral wake extent. The agreement between the present results and previous studies suggests that this trend is robust across different configurations of porous bluff-body and Reynolds number conditions.

It should be also noted that figure 3 captures the structural features of longitudinal bleeding flow immediately downstream of the porous cylinders depending on the pore size and the corresponding permeability. For the porous cylinders with a sufficiently small permeability, as shown in figure 3(b,c), the longitudinal bleeding appears to behave as a combined single jet. In contrast, as pore size increases, inherently leading to higher permeability, the longitudinal bleeding transitions into discrete jet structures emitted from each lattice pore. These discrete jets are demarcated by the internal boundaries of the coloured contours within the wake topology (see figure 3 d–f).

The observed transition in wake structure – from a single, combined jet to spatially discrete bleeding jets – can be further interpreted through the framework of homogenization theory (Mei & Auriault Reference Mei and Auriault1991; Zampogna & Bottaro Reference Zampogna and Bottaro2016). Classical homogenization assumes a strong scale separation between the microscopic porescale and the macroscopic domain size, quantified by the scale separation parameter

![]() $\epsilon =d_1/D$

, where

$\epsilon =d_1/D$

, where

![]() $d_1$

is the unit cell size and

$d_1$

is the unit cell size and

![]() $D$

is the cylinder width. When

$D$

is the cylinder width. When

![]() $\epsilon \ll 1$

, the flow through the porous medium can be approximated as spatially uniform, thereby justifying the emergence of a homogenized jet-like structure in the near wake, as illustrated in figure 3(b,c). However, in the present study, the scale separation parameter spans the range

$\epsilon \ll 1$

, the flow through the porous medium can be approximated as spatially uniform, thereby justifying the emergence of a homogenized jet-like structure in the near wake, as illustrated in figure 3(b,c). However, in the present study, the scale separation parameter spans the range

![]() $0.05\lt \epsilon \lt 0.25$

, and for cases with larger pore size (i.e.

$0.05\lt \epsilon \lt 0.25$

, and for cases with larger pore size (i.e.

![]() $\epsilon \gt 0.1$

, see figure 3

d–f), the assumption of homogenization breaks down. The pores are macroscopically resolvable, and the flow exhibits discrete jet-like features aligned with the pore geometry. This breakdown highlights the limitation of homogenization theory in high-permeability regimes, where pore-resolved effects, such as localized bleeding and wake variability, become significant.

$\epsilon \gt 0.1$

, see figure 3

d–f), the assumption of homogenization breaks down. The pores are macroscopically resolvable, and the flow exhibits discrete jet-like features aligned with the pore geometry. This breakdown highlights the limitation of homogenization theory in high-permeability regimes, where pore-resolved effects, such as localized bleeding and wake variability, become significant.

It is also worth noting that porescale inertial effects play a critical role in determining the flow characteristics particularly under the homogenization framework (Zampogna & Bottaro Reference Zampogna and Bottaro2016). These effects can be quantified using the microscopic-scale Reynolds number

![]() $ \textit{Re}_l=U^*l/\nu$

, where

$ \textit{Re}_l=U^*l/\nu$

, where

![]() $U^*$

is the characteristic internal velocity through the porous matrix, and

$U^*$

is the characteristic internal velocity through the porous matrix, and

![]() $\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity (Zampogna & Bottaro Reference Zampogna and Bottaro2016). However, in our current experimental set-up, the internal velocity cannot be captured using a standard PIV system. Accurate measurement would require advanced techniques such as refractive-index matching (Blois et al. Reference Blois, Bristow, Kim, Best and Christensen2020) or magnetic resonance velocimetry (Elkins & Alley Reference Elkins and Alley2007). In this regard, we are currently unable to systematically assess the inertial contribution at the pore level. Nonetheless, the scale-separation parameter

$\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity (Zampogna & Bottaro Reference Zampogna and Bottaro2016). However, in our current experimental set-up, the internal velocity cannot be captured using a standard PIV system. Accurate measurement would require advanced techniques such as refractive-index matching (Blois et al. Reference Blois, Bristow, Kim, Best and Christensen2020) or magnetic resonance velocimetry (Elkins & Alley Reference Elkins and Alley2007). In this regard, we are currently unable to systematically assess the inertial contribution at the pore level. Nonetheless, the scale-separation parameter

![]() $\epsilon$

remains a useful metric for evaluating the applicability of homogenization in porous bluff-body flows and provides an important physical basis for interpreting the observed transition from homogenized to discrete bleeding behaviour.

$\epsilon$

remains a useful metric for evaluating the applicability of homogenization in porous bluff-body flows and provides an important physical basis for interpreting the observed transition from homogenized to discrete bleeding behaviour.

Figure 4. (a) Schematic representation of the lateral wake extent,

![]() $W_L$

, for case A1. (b) Variation of the lateral wake extent,

$W_L$

, for case A1. (b) Variation of the lateral wake extent,

![]() $W_L$

, as a function of

$W_L$

, as a function of

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

. The crosses bounding the symbols indicate the sensitivity of the wake extent to the threshold level (set at 50

$ \textit{Da} $

. The crosses bounding the symbols indicate the sensitivity of the wake extent to the threshold level (set at 50

![]() $\%$

) used to define the wake edge.

$\%$

) used to define the wake edge.

To further examine the influence of permeability on the wake size, the wake extent is evaluated. In this study, the lateral wake extent is only considered since the longitudinal extents for the porous cylinders are beyond the present PIV FoV under 50

![]() $\,\%$

of the cutoff defining the wake edge. The lateral wake extent

$\,\%$

of the cutoff defining the wake edge. The lateral wake extent

![]() $W_L$

, defined as the maximum lateral distance reached by the wake edge, is illustrated in figure 4(a). In figure 4(b), the measured

$W_L$

, defined as the maximum lateral distance reached by the wake edge, is illustrated in figure 4(a). In figure 4(b), the measured

![]() $W_L$

for all porous cases is plotted against

$W_L$

for all porous cases is plotted against

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

, with uncertainty indicated by cross symbols. The uncertainty in

$ \textit{Da} $

, with uncertainty indicated by cross symbols. The uncertainty in

![]() $W_L$

was quantified by performing a sensitivity analysis, varying the threshold level used to define the wake edge by

$W_L$

was quantified by performing a sensitivity analysis, varying the threshold level used to define the wake edge by

![]() $50 \pm 10\,\%$

(Nicolai et al. Reference Nicolai, Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2020), resulting in a maximum variation of

$50 \pm 10\,\%$

(Nicolai et al. Reference Nicolai, Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2020), resulting in a maximum variation of

![]() $\pm 2.46\,\%$

in

$\pm 2.46\,\%$

in

![]() $W_L$

.

$W_L$

.

As seen in figure 4(b),

![]() $W_L$

expands laterally up to approximately twice the cylinder width

$W_L$

expands laterally up to approximately twice the cylinder width

![]() $D$

for the lowest

$D$

for the lowest

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

(i.e. case A1) and decreases progressively with increasing

$ \textit{Da} $

(i.e. case A1) and decreases progressively with increasing

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

. This reduction in

$ \textit{Da} $

. This reduction in

![]() $W_L$

with increasing

$W_L$

with increasing

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

is attributed to the effect of lateral bleeding, a phenomenon previously shown to strongly influence the wake size in the

$ \textit{Da} $

is attributed to the effect of lateral bleeding, a phenomenon previously shown to strongly influence the wake size in the

![]() $y$

-direction (Taddei et al. Reference Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2016). Nicolai et al. (Reference Nicolai, Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2020) also observed a decreasing trend in wake extent related to cylinder porosity

$y$

-direction (Taddei et al. Reference Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2016). Nicolai et al. (Reference Nicolai, Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2020) also observed a decreasing trend in wake extent related to cylinder porosity

![]() $\varPhi$

, although the relation in their study was implicit. In contrast, the present observations in figure 4(b) reveal an explicit log–linear relationship between

$\varPhi$

, although the relation in their study was implicit. In contrast, the present observations in figure 4(b) reveal an explicit log–linear relationship between

![]() $W_L$

and

$W_L$

and

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

. This result further emphasize the role of permeability as an important control parameter for the wake structures induced by porous cylinders (Cummins et al. Reference Cummins, Viola, Mastropaolo and Nakayama2017; Ledda et al. Reference Ledda, Siconolfi, Viola, Gallaire and Camarri2018; Seol et al. Reference Seol, Hong and Kim2023).

$ \textit{Da} $

. This result further emphasize the role of permeability as an important control parameter for the wake structures induced by porous cylinders (Cummins et al. Reference Cummins, Viola, Mastropaolo and Nakayama2017; Ledda et al. Reference Ledda, Siconolfi, Viola, Gallaire and Camarri2018; Seol et al. Reference Seol, Hong and Kim2023).

Based on the observations in figures 3 and 4, several noteworthy points emerge. First, bleeding flows in both longitudinal and lateral directions significantly affect shear layer development and wake formation behind porous square cylinders. For example, it has been documented that longitudinal bleeding contributes to the weakening of shear layer intensity, while lateral bleeding causes the vertical displacement of the top and bottom shear layers away from the wake core (Taddei et al. Reference Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2016; Nicolai et al. Reference Nicolai, Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2020). In this study, figure 3 illustrates a substantial decrease in velocity deficit with increasing

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

, indicating a significant attenuation in shear layer intensity. Simultaneously, figure 4 demonstrates a decreasing pattern in lateral wake extent with increasing

$ \textit{Da} $

, indicating a significant attenuation in shear layer intensity. Simultaneously, figure 4 demonstrates a decreasing pattern in lateral wake extent with increasing

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

, reflecting weakened lateral bleeding. These findings are consistent with recent observations from both qualitative and quantitative perspectives (Taddei et al. Reference Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2016; Zhou & Venayagamoorthy Reference Zhou and Venayagamoorthy2019; Nicolai et al. Reference Nicolai, Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2020), reaffirming that cylinder permeability and the associated bleeding characteristics predominantly control the flow structures downstream of the porous cylinders.

$ \textit{Da} $

, reflecting weakened lateral bleeding. These findings are consistent with recent observations from both qualitative and quantitative perspectives (Taddei et al. Reference Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2016; Zhou & Venayagamoorthy Reference Zhou and Venayagamoorthy2019; Nicolai et al. Reference Nicolai, Taddei, Manes and Ganapathisubramani2020), reaffirming that cylinder permeability and the associated bleeding characteristics predominantly control the flow structures downstream of the porous cylinders.

Second, discrete longitudinal bleeding jets observed in cases with larger pores and higher permeability (figure 3

d–f) evolve structurally, resembling multiple plane jets as they move downstream (Miller & Comings Reference Miller and Comings1960; Zhao & Wang Reference Zhao and Wang2018). This structural similarity suggests that the discrete jets behind the porous square cylinders can be classified into two distinct regions based on their streamwise location: merging and combined regions. In the merging region, as seen in figure 3(d), individual jets curve towards the symmetry plane (i.e.

![]() $y/D=0$

) and begin to merge. As they move downstream, these jets interact further and coalesce into a single jet in the combined region. Notably, the pore configuration of the cylinder significantly influences local flow structures immediately behind the cylinder. For instance, in the case of cylinders with odd pore configuration (figure 3

d), the momentum of the longitudinal bleeding reaches its maximum at

$y/D=0$

) and begin to merge. As they move downstream, these jets interact further and coalesce into a single jet in the combined region. Notably, the pore configuration of the cylinder significantly influences local flow structures immediately behind the cylinder. For instance, in the case of cylinders with odd pore configuration (figure 3

d), the momentum of the longitudinal bleeding reaches its maximum at

![]() $y/D=0$

and decreases laterally due to the presence of a central pore along the lateral centreline. In contrast, cylinders with even pore configuration (figure 3

e) generate dual jet-like structure, with the highest momentum occurring along the off-centreline, due to the locally impermeable boundary at

$y/D=0$

and decreases laterally due to the presence of a central pore along the lateral centreline. In contrast, cylinders with even pore configuration (figure 3

e) generate dual jet-like structure, with the highest momentum occurring along the off-centreline, due to the locally impermeable boundary at

![]() $y/D=0$

. These differences in the longitudinal bleeding patterns and their interactions lead to complex flow dynamics within the merging region before the jets fully combine into a single structure.

$y/D=0$

. These differences in the longitudinal bleeding patterns and their interactions lead to complex flow dynamics within the merging region before the jets fully combine into a single structure.

Lastly, drawing an analogy from multiple plane jets (Miller & Comings Reference Miller and Comings1960; Zhao & Wang Reference Zhao and Wang2018), the current observations of the permeability effect on longitudinal bleeding provide a basis for developing an analytical model linking the structural characteristics of bleeding jets to permeability. Specifically, the combined point on the centreline marks where the jets coalesce into a single entity. Beyond this point, the effects of the initial conditions have largely dissipated, and the influence of permeability, as a global factor, prevails in the downstream bleeding flow. In our previous work (Seol et al. Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024), we successfully proposed an analytical model for downstream flow adjustment behind porous square cylinders in relation to permeability. We believe that the connection between the structural behaviour of the bleeding (i.e. the combined point) and permeability can be analytically approached. This relationship will be discussed in further detail in § 3.3.

3.2. Structural characteristics of longitudinal bleeding

As discussed in the previous section, bleeding flows play a pivotal role in shaping the wake structures downstream of porous square cylinders. The structural features of longitudinal bleeding are dictated by the permeability and pore configuration of the porous cylinders, which in turn exert a significant influence on the development of the downstream flow. To gain further insight into the fundamental physics governing these flows, it is essential to investigate how the structural characteristics of longitudinal bleeding evolve with permeability and pore configuration. In this section, we examine the downstream evolution of longitudinal bleeding jets, drawing on an analogy with multiple plane turbulent jets, with particular emphasis on the merging and coalescence behaviour of the jets (Miller & Comings Reference Miller and Comings1960; Zhao & Wang Reference Zhao and Wang2018).

Figure 5. (a) Evolution of the longitudinal velocity profiles at multiple downstream positions (

![]() $x/D = 1.5$

, 3, 4.5 and 6) for cases S, A1, B2, C4 and C5, corresponding to increasing

$x/D = 1.5$

, 3, 4.5 and 6) for cases S, A1, B2, C4 and C5, corresponding to increasing

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

. (b) Schematic illustration of the development of longitudinal bleeding jets, interacting with surrounding shear layers. The diagram highlights the merging, combined, and wake regions for the odd pore configuration.

$ \textit{Da} $

. (b) Schematic illustration of the development of longitudinal bleeding jets, interacting with surrounding shear layers. The diagram highlights the merging, combined, and wake regions for the odd pore configuration.

Figure 5(a) shows the lateral profiles of the mean longitudinal velocity,

![]() $\langle u \rangle /U_e$

, at several downstream positions for selected porous cases, emphasizing the structural evolution of bleeding flows. Four porous cases (A1, B2, C4 and C5) are selected as representative configurations to capture distinct structural patterns across pore arrangement and permeability. The solid square (case S) is included as a baseline without bleeding. These cases cover the tested

$\langle u \rangle /U_e$

, at several downstream positions for selected porous cases, emphasizing the structural evolution of bleeding flows. Four porous cases (A1, B2, C4 and C5) are selected as representative configurations to capture distinct structural patterns across pore arrangement and permeability. The solid square (case S) is included as a baseline without bleeding. These cases cover the tested

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

range and represent both odd and even pore configurations. Other tested configurations exhibit the same qualitative behaviour and are therefore omitted for clarity.

$ \textit{Da} $

range and represent both odd and even pore configurations. Other tested configurations exhibit the same qualitative behaviour and are therefore omitted for clarity.

As evident in figure 5(a), the flow structure downstream of porous cylinders differs considerably from that of the solid cylinder due to the influence of bleeding flows. In the solid case, the centreline velocity reaches its minimum around

![]() $x/D=1.95$

(not shown for brevity), marking the onset of cylinder-scale vortex formation, followed by velocity recovery. In contrast, for porous cases, longitudinal bleedings shifts the minimum velocity point farther downstream, delaying the formation of large-scale vortices (Zong & Nepf Reference Zong and Nepf2012). In figure 5(a), the near-wake (

$x/D=1.95$

(not shown for brevity), marking the onset of cylinder-scale vortex formation, followed by velocity recovery. In contrast, for porous cases, longitudinal bleedings shifts the minimum velocity point farther downstream, delaying the formation of large-scale vortices (Zong & Nepf Reference Zong and Nepf2012). In figure 5(a), the near-wake (

![]() $x/D=1.5$

) exhibits more pronounced longitudinal bleeding, with individual bleeding jets becoming increasingly distinct and aligned with the lattice pores as pore size and permeability increase. These velocity profiles in the near-wake quantitatively confirm that the formation of the bleeding jet structure is strongly influenced by the pore configuration whether it corresponds to an odd or even case, as noted in the wake topologies (see figure 3). Interestingly, for the cases with larger pores (i.e. C4 and C5), figure 5(a) illustrates the merging of multiple parallel jets, emitted from each lattice pore, as they propagate downstream. These jets eventually combine into a single structure, which spreads and decays farther downstream. In contrast, for smaller pore cases (i.e. A1 and B2), their velocity profiles at

$x/D=1.5$

) exhibits more pronounced longitudinal bleeding, with individual bleeding jets becoming increasingly distinct and aligned with the lattice pores as pore size and permeability increase. These velocity profiles in the near-wake quantitatively confirm that the formation of the bleeding jet structure is strongly influenced by the pore configuration whether it corresponds to an odd or even case, as noted in the wake topologies (see figure 3). Interestingly, for the cases with larger pores (i.e. C4 and C5), figure 5(a) illustrates the merging of multiple parallel jets, emitted from each lattice pore, as they propagate downstream. These jets eventually combine into a single structure, which spreads and decays farther downstream. In contrast, for smaller pore cases (i.e. A1 and B2), their velocity profiles at

![]() $x/D=1.5$

resemble a single jet, indicating rapid flow adjustment immediately behind the porous cylinder (Seol et al. Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024).

$x/D=1.5$

resemble a single jet, indicating rapid flow adjustment immediately behind the porous cylinder (Seol et al. Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024).

The observations from figure 5(a) suggest a new conceptual model of bleeding flows behind porous square cylinders, analogous to the behaviour observed in parallel plane jets (Miller & Comings Reference Miller and Comings1960; Zhao & Wang Reference Zhao and Wang2018), although with distinct shear layer dynamics due to the influence of a strong external flow. Figure 5(b) illustrates this proposed model, which divides the longitudinal bleeding domain into three distinct flow regions based on their structural attributes. The first region, termed the merging region, situated near the jet exit where individual jets begin to interact and merge, leading to significant mixing and causing the flow to lose its individual jet characteristics. This is followed by the combined region, where the coalesced jets behave as a single, unified flow that progressively spreads and decays while interacting with the top and bottom shear layers induced by the cylinder. Finally, the wake region is located downstream of the combined region, where the combined jet fully dissipates and transitions into a wake characterized by the onset of wake recovery process. This conceptual framework captures the complex evolution of longitudinal bleedings behind porous square cylinders, offering a detailed understanding of how these jets shape the downstream flow structure under the influence of surrounding shear layers.

Figure 6. Selected contour maps of the normalized mean longitudinal velocity,

![]() $\langle u \rangle /U_e$

, superimposed with streamlines for case B, where

$\langle u \rangle /U_e$

, superimposed with streamlines for case B, where

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

varies while maintaining a constant porosity of

$ \textit{Da} $

varies while maintaining a constant porosity of

![]() $\varPhi =0.8$

. Red dashed circles indicate the main recirculation bubble at

$\varPhi =0.8$

. Red dashed circles indicate the main recirculation bubble at

![]() $y/D=0$

, while yellow dashed circles highlight the second recirculation bubble attached to the cylinder trailing edge.

$y/D=0$

, while yellow dashed circles highlight the second recirculation bubble attached to the cylinder trailing edge.

To investigate the overall behaviour of longitudinal bleeding flows and their influence on downstream flow structures, contour maps of the mean longitudinal velocity (

![]() $\langle u \rangle /U_e$

) with streamlines are presented in figure 6. Here,

$\langle u \rangle /U_e$

) with streamlines are presented in figure 6. Here,

![]() $\langle \boldsymbol{\cdot }\rangle$

denotes the ensemble average of a quantity. The analysis focuses on porous cylinders from case B, where permeability varies with unit-cell scaling while maintaining a constant porosity of

$\langle \boldsymbol{\cdot }\rangle$

denotes the ensemble average of a quantity. The analysis focuses on porous cylinders from case B, where permeability varies with unit-cell scaling while maintaining a constant porosity of

![]() $\varPhi =0.8$

. For clarity, a side view of the cylinder cross-section is included at the origin to aid in understanding the structural features of the longitudinal bleeding flows.

$\varPhi =0.8$

. For clarity, a side view of the cylinder cross-section is included at the origin to aid in understanding the structural features of the longitudinal bleeding flows.

Figure 6 reveals the presence of longitudinal bleeding flow along the symmetric plane (

![]() $y/D=0$

) for all porous cases due to the permeable nature of the cylinders. However, both the momentum and the longitudinal extent of this bleeding flow are strongly influenced by cylinder permeability (

$y/D=0$

) for all porous cases due to the permeable nature of the cylinders. However, both the momentum and the longitudinal extent of this bleeding flow are strongly influenced by cylinder permeability (

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

), which in turn modifies the main recirculation bubble. As highlighted by the red dashed circles in figure 6, increasing permeability leads to a reduction in the size of the main recirculation bubble and causes it to shift farther downstream, consistent with the findings of Ledda et al. (Reference Ledda, Siconolfi, Viola, Gallaire and Camarri2018). When reaches its critical value (

$ \textit{Da} $

), which in turn modifies the main recirculation bubble. As highlighted by the red dashed circles in figure 6, increasing permeability leads to a reduction in the size of the main recirculation bubble and causes it to shift farther downstream, consistent with the findings of Ledda et al. (Reference Ledda, Siconolfi, Viola, Gallaire and Camarri2018). When reaches its critical value (

![]() $ \textit{Da}_c=2\times 10^{-4}$

), as reported in our previous work (Seol et al. Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024), the reverse flow in the downstream region vanishes. Instead, a steady wake region with positive and nearly constant velocity develops, as seen in figure 6(e) and 6(f) (Zong & Nepf Reference Zong and Nepf2012). Based on this structural behaviour, Seol et al. (Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024) categorized flows into two regimes: high flow-blockage cases (

$ \textit{Da}_c=2\times 10^{-4}$

), as reported in our previous work (Seol et al. Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024), the reverse flow in the downstream region vanishes. Instead, a steady wake region with positive and nearly constant velocity develops, as seen in figure 6(e) and 6(f) (Zong & Nepf Reference Zong and Nepf2012). Based on this structural behaviour, Seol et al. (Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024) categorized flows into two regimes: high flow-blockage cases (

![]() $ \textit{Da} \lt Da_c$

) and low flow-blockage cases (

$ \textit{Da} \lt Da_c$

) and low flow-blockage cases (

![]() $ \textit{Da} \gt Da_c$

).

$ \textit{Da} \gt Da_c$

).

Additionally, figure 6 captures a second pair of recirculation bubbles attached to the trailing edge of the porous cylinders, highlighted by the yellow dashed circles. These bubbles have been reported in past numerical and experimental studies (Fang et al. Reference Fang, Yang, Ma and Li2020; Seol et al. Reference Seol, Kim and Kim2024) and attributed to the shear layer interactions between the separated external flow and the longitudinal bleeding flow. The second recirculation bubble represents a low-pressure zone that envelops the longitudinal bleeding flow near the trailing edge. These second bubble pairs thus influence the structural development of the longitudinal bleeding, inducing local acceleration and deceleration as the flow convects downstream in the near wake. Consequently, the observations in figure 6 suggest that the coupled effects of the main and second recirculation bubbles play a role in governing the structural behaviour of longitudinal bleeding flows downstream of the porous cylinders.

Figure 7. Selected contour maps of the normalized Reynolds shear stress,

![]() $-\langle u'v' \rangle /U_e^2$

, for the same cases shown in figure 6.

$-\langle u'v' \rangle /U_e^2$

, for the same cases shown in figure 6.

To further explore the structural evolution of longitudinal bleeding flows and their resulting shear layers as a function of permeability, contour maps of Reynolds shear stress,

![]() $-\langle u'v' \rangle$

, normalized by

$-\langle u'v' \rangle$

, normalized by

![]() $U_e^2$

are presented in figure 7. Here,

$U_e^2$

are presented in figure 7. Here,

![]() $u'$

and

$u'$

and

![]() $v'$

are the fluctuating velocity components in the longitudinal and lateral directions, respectively. For consistency, the same porous cases as in figure 6 are considered. A schematic representation of the cylinder cross-section is included to facilitate understanding of the structural characteristics of the bleeding shear layers, which are influenced by pore size and the corresponding permeability. Here, the term bleeding shear layer refers to the shear layers generated by longitudinal bleeding jets immediately downstream of the porous cylinders. This terminology is introduced intentionally to avoid confusion with the shear layers originating from flow separation at the leading edge of the cylinders. For reference, the solid cylinder case is also included to highlight the modifications in shear layer structure induced by the permeable nature of the cylinders and the resulting bleeding flows.

$v'$

are the fluctuating velocity components in the longitudinal and lateral directions, respectively. For consistency, the same porous cases as in figure 6 are considered. A schematic representation of the cylinder cross-section is included to facilitate understanding of the structural characteristics of the bleeding shear layers, which are influenced by pore size and the corresponding permeability. Here, the term bleeding shear layer refers to the shear layers generated by longitudinal bleeding jets immediately downstream of the porous cylinders. This terminology is introduced intentionally to avoid confusion with the shear layers originating from flow separation at the leading edge of the cylinders. For reference, the solid cylinder case is also included to highlight the modifications in shear layer structure induced by the permeable nature of the cylinders and the resulting bleeding flows.

Figure 7 clearly illustrates the impact of permeability on the intensity and development of the primary shear layers shed from the leading edge of the cylinders. As

![]() $ \textit{Da} $

increases, the magnitude of

$ \textit{Da} $

increases, the magnitude of

![]() $-\langle u'v' \rangle$