Introduction

Reproduction in Brachyura is modulated by a series of factors, ranging from life history aspects and complex reproductive strategies to peculiar behaviours in courtship and mating. In this context, numerous morphological characteristics have evolved within the group, contributing to its reproductive success (see McLay and Becker, Reference McLay, Becker, Castro, Davie, Guinot, Schram and Von vaupel klein2015). The morphology of the reproductive system of some Brachyura species has already been described in the literature, but the vast majority have focused on Heterotremata crabs, with few studies on Podotremata and Thoracotremata (see Antunes et al., Reference Antunes, Zara and Negreiros-Fransozo2016; Assugeni et al., Reference Assugeni, Toyama and Zara2021; Becker et al., Reference Becker, Brandis and Storch2011; Castilho et al., Reference Castilho, Ostrensky, Pie and Boeger2008; Diesel Reference Diesel1989; Erkan et al., Reference Erkan, Tunali, Balkis and Oliveira2009; Garcia-Bento et al., Reference Garcia-Bento, López-Greco and Zara2019; Nascimento and Zara, Reference Nascimento and Zara2013; Shinozaki-Mendes et al., Reference Shinozaki-Mendes, Silva and Hazin2011; Simeó et al., Reference Simeó, Ribes and Rotllant2009; Souza et al., Reference Souza, Silva, Araujo and Camargo-Mathias2013; Zara et al., Reference Zara, Toyama, Caetano and López-Greco2012).

The male reproductive system of brachyurans is bilateral, H-shaped, located in the cephalothorax, and consists of a pair of testes, vasa deferentia and ejaculatory ducts (Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, López-Greco and Zara2022). Histologically, the testes of brachyurans can be classified as lobular, which is the common pattern recorded for most crabs, although they can also be tubular, as described for some species of Grapsoidea MacLeay, 1838, Majoidea Samouelle, 1819 and Xanthoidea MacLeay, 1838 (Nagao and Munehara Reference Nagao and Munehara2003; Simeó et al., Reference Simeó, Ribes and Rotllant2009). Spermatozoa produced in the testes, once mature, are transported to the vas deferens, which is typically divided into three regions: anterior (AVD), median (MVD), and posterior (PVD) (Krol et al., Reference Krol, Hawkins, Overstreet, Harrison and Humes1992). In the AVD, seminal fluid is produced, which is related to the aggregation of spermatozoa, leading to the formation of coenospermic spermatophores (with several spermatozoa), which is the most common type observed in Eubrachyura, in contrast to cleistospermic spermatophores (with a single sperm), more common in freshwater crabs (Anilkumar et al., Reference Anilkumar, Sudha and Subramoniam1999; Klaus and Brandis, Reference Klaus and Brandis2011; Tiseo et al., Reference Tiseo, Mantelatto and Zara2014). The other two regions (MVD and PVD) are responsible for the storage of spermatozoa, as well as the production of additional seminal fluid (Adiyodi and Anilkumar, Reference Adiyodi, Anilkumar, Adiyodi and Adiyodi1988; Beninger et al., Reference Beninger, Elner, Foyle and Odense1988; Johnson Reference Johnson1980; McLay and Becker, Reference McLay, Becker, Castro, Davie, Guinot, Schram and Von vaupel klein2015). Besides, in some species, these regions may present accessory glands, ceca, diverticula, or outpockets, which function to produce secretions for the formation of spermatic layers or packages (Majoidea), or sperm plugs (Portunoidea) (Diesel, Reference Diesel1989; Zara et al., Reference Zara, Toyama, Caetano and López-Greco2012, Reference Zara, Raggi Pereira and Sant’Anna2014; Antunes et al., Reference Antunes, Zara, López Greco and Negreiros‐Fransozo2018; Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, López-Greco and Zara2022).

Among female eubrachyuran crabs, the reproductive system may have an expansion of the oviduct, leading to an internal connection with the ovary, where sperm storage and fertilization occur, called the seminal receptacle (SR), with a dorsal mesodermal region and a ventral ectodermal region, continuous with the vagina and vulva, whose opening is mesial on the sixth thoracic segment (McLay and López-Greco, Reference McLay and López-Greco2011). The connection of the oviduct with the SR can differ according to the eubrachyuran species (Diesel, Reference Diesel, Bauer and Martin1991; McLay and López-Greco, Reference McLay and López-Greco2011), ranging from a dorsal position (opposite to the insertion with the vagina) to a ventral position, juxtaposed to the vagina, still in the mesodermal region (Assugeni and Zara, Reference Assugeni and Zara2022; McLay and Becker, Reference McLay, Becker, Castro, Davie, Guinot, Schram and Von vaupel klein2015). This expansion and connection of the ovary with the oviduct do not occur in Podotremata crabs, where the sperm storage structure, the spermatheca, is exclusively ectodermal, surrounded by cuticle, and derived from the 7th and 8th thoracic segments, forming a suture line on the female thoracic sternum (Garcia-Bento et al., Reference Garcia-Bento, López-Greco and Zara2019; Guinot et al., Reference Guinot, Tavares and Castro2013).

Female Eubrachyura store sperm until fertilization (McLay and Becker, Reference McLay, Becker, Castro, Davie, Guinot, Schram and Von vaupel klein2015; McLay and López-Greco, Reference McLay and López-Greco2011), with the maintenance cost supported by female secretions (see Adiyodi and Anilkumar, Reference Adiyodi, Anilkumar, Adiyodi and Adiyodi1988; Beninger et al., Reference Beninger, Lanteigne and Elner1993; McLay and Becker, Reference McLay, Becker, Castro, Davie, Guinot, Schram and Von vaupel klein2015). In contrast, male secretions can influence the process of sperm competition, possibly having a gel-like consistency (Antunes et al., Reference Antunes, Zara and Negreiros-Fransozo2016; Diesel, Reference Diesel, Bauer and Martin1991; Ryan, Reference Ryan1967) or hardening into a seminal plug (Assugeni et al., Reference Assugeni, Toyama and Zara2021; Zara et al., Reference Zara, Raggi Pereira and Sant’Anna2014, Reference Zara, Toyama, Caetano and López-Greco2012). Gel-like secretions surround the spermatic package, acting to displace ejaculates from previous matings (Antunes et al., Reference Antunes, Zara and Negreiros-Fransozo2016), while the seminal plug externally occludes the vulva opening in females, preventing other males from introducing their gonopods and transferring their genetic material (Hartnoll, Reference Hartnoll1969; Hines et al., Reference Hines, Jivoff, Bushmann, Van Montfrans, Reed, Wolcott and Wolcott2003; Zara et al., Reference Zara, Raggi Pereira and Sant’Anna2014). Moreover, the combined secretions from males and females may have other functions, such as aiding in spermatophore dehiscence, protecting gametes (e.g., bacteriostatic properties), and supporting anaerobic sperm metabolism (Beninger et al., Reference Beninger, Lanteigne and Elner1993; Jeyalectumie and Subramoniam, Reference Jeyalectumie and Subramoniam1991; Sant’Anna et al., Reference Sant’Anna, Pinheiro, Mataqueiro and Zara2007).

In Gecarcinidae MacLeay, 1838, few studies describe aspects of the morphology or histochemistry of the reproductive system, particularly concerning Cardisoma guanhumi Latreille in Latreille, Le Peletier, Serville & Guérin, 1828 (see Shinozaki-Mendes et al., Reference Shinozaki-Mendes, Silva and Hazin2011, Reference Shinozaki-Mendes, Silva, Souza and Hazin2012; Souza et al., Reference Souza, Silva, Araujo and Camargo-Mathias2013). Nevertheless, the available studies are relatively superficial, especially concerning the male reproductive system, resulting in considerable morphological gaps that hinder meaningful comparisons with other species of the family. Additionally, within this family, different selective pressures act on continental species (e.g., genus Cardisoma Latreille, 1828) and insular species (e.g., genera Gecarcoidea H. Milne Edwards, 1837, Gecarcinus Leach, 1814, and Johngarthia Türkay, 1970), which have contrasting life histories (Guinot et al., Reference Guinot, Ng and Moreno2018; Marin and Tiunov, Reference Marin and Tiunov2023; Pkl et al., Reference Pkl, Guinot and Davie2008). To date, no descriptions of the male and female reproductive systems of insular gecarcinids exist, except for the external morphology of the gonads and their use in studies of sexual maturity (Hartnoll et al., Reference Hartnoll, Weber, Weber and Liu2017; João et al., Reference João, Kriegler, Freire and Pinheiro2021). Among the insular species, the genus Johngarthia stands out, encompassing six endemic species of oceanic islands: Johngarthia malpilensis (Faxon, 1893), Johngarthia planata (Stimpson, 1860), Johngarthia cocoensis Perger, Vargas and Wall, Reference Perger, Vargas and Wall2011, and Johngarthia oceanica Perger, 2019 in the Eastern Pacific; Johngarthia lagostoma (H. Milne Edwards, 1837) in the Central-West Atlantic; and Johngarthia weileiri (Sendler, 1912) in the Eastern Atlantic (Perger et al., Reference Perger, Vargas and Wall2011; Pkl et al., Reference Pkl, Guinot and Davie2008).

Johngarthia lagostoma (H.Milne Edwards, 1837), commonly known as the yellow crab, has its global distribution restricted to four small islands in the Atlantic Ocean: Rocas Atoll, Fernando de Noronha, Ascension, and Trindade. In Brazil, this species is categorized as ‘Endangered’ (EN) by the IUCN criteria due to its reduced range of occurrence, declining habitat quality, and the introduction of exotic species (Pinheiro et al., Reference Pinheiro, Santana, Rodrigues, Ivo, Santos, Torres, Boos, Dias-Neto, Pinheiro and Boos2016). The literature on J. lagostoma is still scarce, focusing on its reproductive dynamics (Hartnoll et al., Reference Hartnoll, Broderick, Musick, Godley, Pearson, Stroud and Saunders2010; João et al., Reference João, Duarte, Bispo da silva, Freire and Pinheiro2022, Reference João, Kriegler, Freire and Pinheiro2021; Mosna et al., Reference Mosna, Oliveira, João and Pinheiro2025), larval development (Colavite et al., Reference Colavite, Tavares, Mendonça and Santana2021; Lira et al., Reference Lira, Lima, Teixeira and Schwamborn2021), population structure (Hartnoll et al., Reference Hartnoll, Broderick, Godley and Saunders2009, Reference Hartnoll, Mackintosh and Pelembe2006; João et al., Reference João, Duarte, Freire, Kriegler and Pinheiro2023a), and evolution (Hartnoll et al., Reference Hartnoll, Weber, Weber and Liu2017; João et al., Reference João, Duarte, Freire and Pinheiro2023b). However, studies are still needed to describe the morphology of the male and female reproductive systems, facilitating a better understanding of its reproductive history.

This study describes the male and female reproductive systems of J. lagostoma, analysing their anatomy, histology, and histochemistry to elucidate the production and storage of seminal fluid and spermatozoa, aiming to understand the coevolution of reproductive systems in this important island crab. Studies on the reproduction of endangered species are crucial for developing conservation strategies (Pinheiro et al., Reference Pinheiro, Santana, Rodrigues, Ivo, Santos, Torres, Boos, Dias-Neto, Pinheiro and Boos2016). Therefore, the results of this study are key to advancing reproductive knowledge of J. lagostoma, which belongs to one of the most terrestrial brachyuran families on our planet (Marin and Tiunov, Reference Marin and Tiunov2023).

Materials & methods

Specimens of J. lagostoma (n = 10) were manually collected during expeditions to Trindade Island (Brazil) from February to April 2019 and from April to June 2022. Five specimens of each sex were obtained, with carapace width (CW) sizes exceeding physiological maturity (CW ≥ 56 mm), as estimated by João et al., (Reference João, Duarte, Bispo da silva, Freire and Pinheiro2022). In the laboratory, the animals were weighed (WE, total weight) using a precision balance (0.01 g) and measured with a digital caliper (0.01 mm). Subsequently, the specimens were anesthetized by cooling and then dissected. The reproductive systems of each sex were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution in 0.2 M phosphate buffer in seawater. The samples were kept in this fixative until the end of the expedition and transported to the laboratory.

In the laboratory, the materials were subjected to three 30-minute washes in 0.2 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) and then photographed under a stereomicroscope for anatomical descriptions. The samples were subsequently dehydrated in an ascending series of ethanol concentrations (70–95%) and embedded in Leica® glycol methacrylate historesin. Serial sections of 4–7 µm thickness were obtained using a rotary microtome.

For general histological description, the slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Junqueira and Junqueira, Reference Junqueira and Junqueira1983). For histochemistry, the slides were subjected to the following techniques: Xylidine Ponceau for proteins (Mello and Vidal, Reference Mello and Vidal1980); periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) for neutral polysaccharides; and Alcian Blue for acidic polysaccharides (Junqueira and Junqueira, Reference Junqueira and Junqueira1983). To better visualize different stages of spermiogenesis, testicular slides were treated with the PAS technique combined with hematoxylin (Junqueira and Junqueira, Reference Junqueira and Junqueira1983).

Results

Five males ranged in carapace width (CW) from 91.3 to 99.6 mm (mean ± SD: 95.0 ± 3.4 mm) and in body weight (WE) from 259.4 to 342.6 g (305.9 ± 33.5 g). Similarly, five females ranged in CW from 81.6 to 94.3 mm (90.5 ± 5.1 mm) and in WE from 235.6 to 259.4 g (246.7 ± 10.1 g).

Male reproductive system

Anatomy

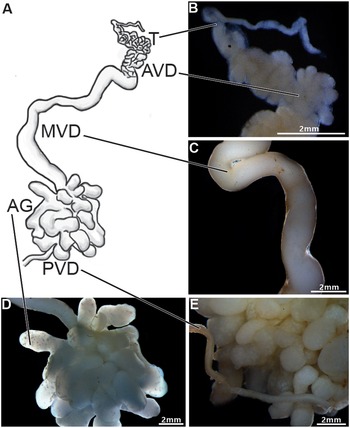

The male reproductive system of Johngarthia lagostoma (Figure 1) exhibits bilateral symmetry with an ‘H’shape, consisting of a pair of testes. These are located on the upper margin (right and left) of the cephalothorax, connected to the vasa deferentia, which extend longitudinally over the hepatopancreas, ending at the posterior region of the body. The testis is highly convoluted (Figure 1A and B), starting at the anterior periphery of the cephalothorax and traversing the central region of the cephalothoracic cavity, where this paired organ joins through a commissure located just below the intestine.

Figure 1. Anatomy of the male reproductive system of Johngarthia lagostoma. (A) Diagram of the male reproductive system (right side), showing the testis (T), different regions of the vas deferens (AVD, anterior; MVD, middle; and PVD, posterior), and the accessory glands (AG); (B) Detail of the testis and AVD, both convoluted regions; (C) Detail of the MVD, longer and less convoluted; (D) Detail of the accessory glands, highly branched tubular structures; (E) Detail of the PVD, which channels the various branches of the accessory glands into a single tubule.

The vas deferens was divided into three distinct regions: anterior (AVD), median (MVD), and posterior (PVD) (Figure 1A). The AVD is a highly convoluted, slender tubular structure (Figure 1B). The MVD is long, slightly convoluted, with a smooth surface and a wider diameter compared to the AVD (Figure 1C). At the transition between the MVD and PVD, tubular accessory glands with multiple branches are observed (Figure 1D). The PVD appears as a single slender tube, slightly convoluted and smooth like the MVD, positioned just after the accessory glands (Figure 1E).

Histology and histochemistry

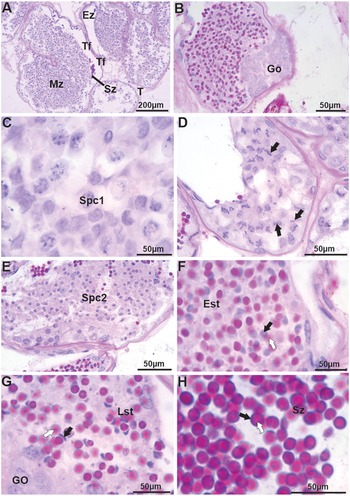

The testes of J. lagostoma are of the tubular type (Figure 2A), showing cells at different stages of spermatogenesis (Figure 2B–E) and spermiogenesis (Figure 2F–H). Generally, spermatogonia are located at the periphery of the seminiferous tubule (Figure 2B), forming the germinative zone, with cells displaying large basophilic nuclei. Primary and secondary spermatocytes are mainly observed in the maturation zone. Primary spermatocytes have large nuclei in different stages of meiotic prophase (Figure 2C–D), while secondary spermatocytes show small nuclei with homogeneous chromatin (Figure 2E). Spermiogenesis begins with early spermatids that display rounded basophilic nuclei and an acrosomal vesicle stained with PAS (Figure 2F). In the final stages, spermatids have more reduced crescent-shaped nuclei, while the acrosomal vesicle appears more heterogeneous, strongly stained with the PAS-H technique, and positioned opposite the nucleus (Figure 2G). Mature spermatozoa are located in the evacuation zone, displaying slender nuclei seemingly surrounded by the acrosomal vesicle with its central portion, the perforatorial chamber, showing weaker staining for neutral polysaccharides (Figure 2H).

Figure 2. Histology of the testes, vas deferens, and germ cells (spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis) in Johngarthia lagostoma. (A) Tubular testes with visible spermatozoa in the seminiferous tubule; (B) Spermatogonia located at the periphery of the seminiferous tubule (germinal zone). These cells have large basophilic nuclei; (C) and (D) Detail of spermatocytes I with nuclei at different stages of meiotic prophase (black arrows); (E) Spermatocytes II consisting of small, homogeneous nuclei; (F) Beginning of spermiogenesis with early spermatids exhibiting basophilic, round nuclei (black arrow) and an acrosomal vesicle stained by PAS (white arrow); (G) Final stage of spermatid with the nucleus in a crescent shape (black arrow), with a more heterogeneous acrosomal vesicle positioned opposite the nucleus (white arrow); (H) Mature spermatozoa in the evacuation zone, with basophilic nuclei (black arrow) and a heterogeneous acrosomal vesicle stained by PAS (white arrow). Staining: PAS and hematoxylin. Est, early spermatids; Ez, evacuation zone; Go, spermatogonia; Lst, late spermatid; Mz, maturation zone; Spc1, spermatocytes I; Spc2, spermatocytes II; Sz, spermatozoa; Tf, seminiferous tubule.

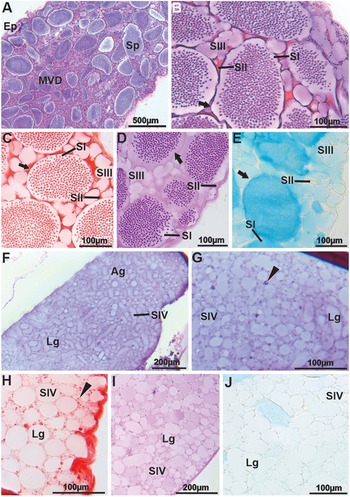

Mature spermatozoa are transported to the vas deferens, where in the AVD, due to the presence or absence of the spermatophore wall compacting sperm masses, this region was divided into two parts – proximal (AVDp) and distal (AVDd). Both parts exhibit simple cuboidal epithelium (Figure 3A–B). In the lumen of the AVDp, a large mass of free spermatozoa immersed in basophilic secretion is observed (Figure 3B), slightly positive for proteins (Figure 3C) and for neutral and acidic polysaccharides (Figure 3D–E, respectively), termed secretion type I (SI). Additionally, at the periphery of the AVDp, another type of acidophilic secretion is noted, termed secretion type II (SII). SII is strongly reactive for proteins (Figure 3C), positive for neutral polysaccharides (Figure 3D), and negative for acidic polysaccharides (Figure 3E). In the AVDd, SII becomes thicker and starts enveloping the spermatozoa, forming the spermatophore wall (Figure 3F–G). The spermatophore wall is basophilic (Figure 3G–H), strongly proteinaceous (Figure 3I), and positive for neutral (Figure 3J) and acidic polysaccharides (Figure 3K). Inside the spermatophores, the spermatozoa are immersed in SI, which remains basophilic and slightly positive for proteins, neutral, and acidic polysaccharides. SII, which surrounds the spermatophores, retains the same chemical composition observed in the AVDp (Figure 3F–K).

Figure 3. Histology and histochemistry of the anterior vas deferens (AVD) in Johngarthia lagostoma. (A) Proximal region of the anterior vas deferens (AVDp) in HE, with the lumen filled with free spermatozoa (arrow) immersed in type I secretions. (B) Detail of the AVDp in HE, showing free spermatozoa (arrow) and basophilic type I and acidophilic type II secretions. (C) Detail of free spermatozoa (arrow) in the AVDp, with secretions subjected to Xylidine ponceau (Secretion one: slightly positive; Secretion two: strongly positive for proteins). (D) and (E) AVDp subjected to PAS and Alcian blue (detection of neutral and acidic polysaccharides, respectively), presenting free spermatozoa (arrow). Note that secretion one is slightly positive for both stains, while secretion two is slightly positive for PAS and negative for Alcian blue. (F), (G), and (H) Distal region of the vas deferens (AVDd) in HE, showing the formation of spermatophores with spermatozoa. Secretion one remains basophilic, secretion two acidophilic, and the wall of the coenospermic spermatophores (arrow) is basophilic. (I) AVDd with the wall of the spermatophores (arrow) strongly proteic when subjected to Xylidine ponceau. (J) and (K) Spermatophores with walls (arrows) positive for neutral and acidic polysaccharides, stained with PAS and Alcian blue, respectively. Ep, simple cuboidal epithelium; Sp, spermatophores; Sz, spermatozoa; SI, secretion one; SII, secretion two.

In the MVD, the epithelium is simple squamous (Figure 4A). SII, located around the spermatophores, may serve as a structural matrix that supports the deposition of a new granular or globular secretion (SIII) (Figure 4B). SII remains acidophilic (Figure 4A–B), strongly proteinaceous (Figure 4C), weakly reactive for neutral polysaccharides (Figure 4D), and acidic polysaccharides (Figure 4E). SIII shows basophilic granules, weakly positive for proteins, neutral polysaccharides, and positive for acidic polysaccharides (Figure 4B–E). The chemical composition of the secretions from the wall and inside the spermatophores is identical to that of the AVDd (Figure 4B–E). At the transition between the MVD and PVD, tubular accessory glands with branches open into the lumen. These glands produce a large amount of secretion, named secretion type IV (SIV), which is released through a merocrine mechanism, since there is no apical accumulation or epithelial dilation, nor goblet cell–like release or holocrine disintegration. SIV exhibits slightly basophilic spherical to elliptical granules (Figure 4F–G), weakly positive for proteins (Figure 4H), positive for neutral polysaccharides (Figure 4I), and negative for acidic polysaccharides (Figure 4J).

Figure 4. Histology and histochemistry of the middle vas deferens (MVD) and accessory glands (AG) in Johngarthia lagostoma. (A) General view of the MVD in HE, showing a large quantity of spermatophores immersed in secretion. (B) Detail of the MVD stained with HE. Note the spermatophores with basophilic walls (arrow), surrounded by acidophilic secretions one and two, which form the matrix for secretion three, containing basophilic granules. (C) In Xylidine ponceau, secretion two is strongly positive, and secretion three shows slight reactivity to the stain. The arrow points to the spermatophore wall. (D) and (E) MVD subjected to PAS and Alcian blue, respectively. The spermatophore wall (arrow) and secretions two and three are weakly reactive to the stains. (F) and (G) General view and detail of the accessory gland in HE, showing large basophilic granules that make up secretion four and small portions of secretion two (head of the arrow). (H) Granules of secretion four show weak positivity when subjected to Xylidine ponceau. Notice that secretion two is more strongly stained for proteins (head of the arrow). (I) and (J) Secretion four with granules weakly positive for neutral and acidic polysaccharides when stained with PAS and Alcian blue, respectively. Ag, accessory gland; Ep, simple squamous epithelium; Lg, basophilic granules; Sp, spermatophores; SI, secretion one; SII, secretion two; SIII, secretion three; SIV, secretion four.

In the PVD, just after the glands and in the ejaculatory duct, the seminal fluid in the duct (spermatophores, SII, and SIII), along with the SIV from the glands, mix (Figure 5A–H). SIII and SIV are positive for neutral polysaccharides when stained with PAS (Figure 5E–F), while for acidic polysaccharides, SIV is slightly negative, and SIII is positive (Figure 5G–H). The SII, originating from the AVDp, remains non-reactive for acidic polysaccharides (Figure 5G–H). Additionally, the number of spermatophores in the PVD is clearly lower than in the MVD, and they are more dispersed among the secretions, with greater spacing between the spermatophores themselves.

Figure 5. Histology and histochemistry of the posterior vas deferens (PVD) and ejaculatory duct (ED) in Johngarthia lagostoma. (A) and (B) PVD and ejaculatory duct in HE, showing a mixture of secretions from the vas deferens and accessory glands. Note the more spaced spermatophores, secretion types of SI and SIV (basophilic), and type SIII (acidophilic). (C) and (D) PVD and ejaculatory duct, respectively. In Xylidine ponceau, all secretions are weakly positive for proteins. (E) and (F) PVD and ejaculatory duct, showing that SIV becomes more positive with PAS. (G) and (H) PVD and ejaculatory duct, exhibiting SIV less positive for acidic polysaccharides when subjected to Alcian blue. Ed, ejaculatory duct; M, muscle bundles; Sp, spermatophores; SI, secretion one; SII, secretion two; SIII, secretion three; SIV, secretion four.

Female reproductive system

Anatomy

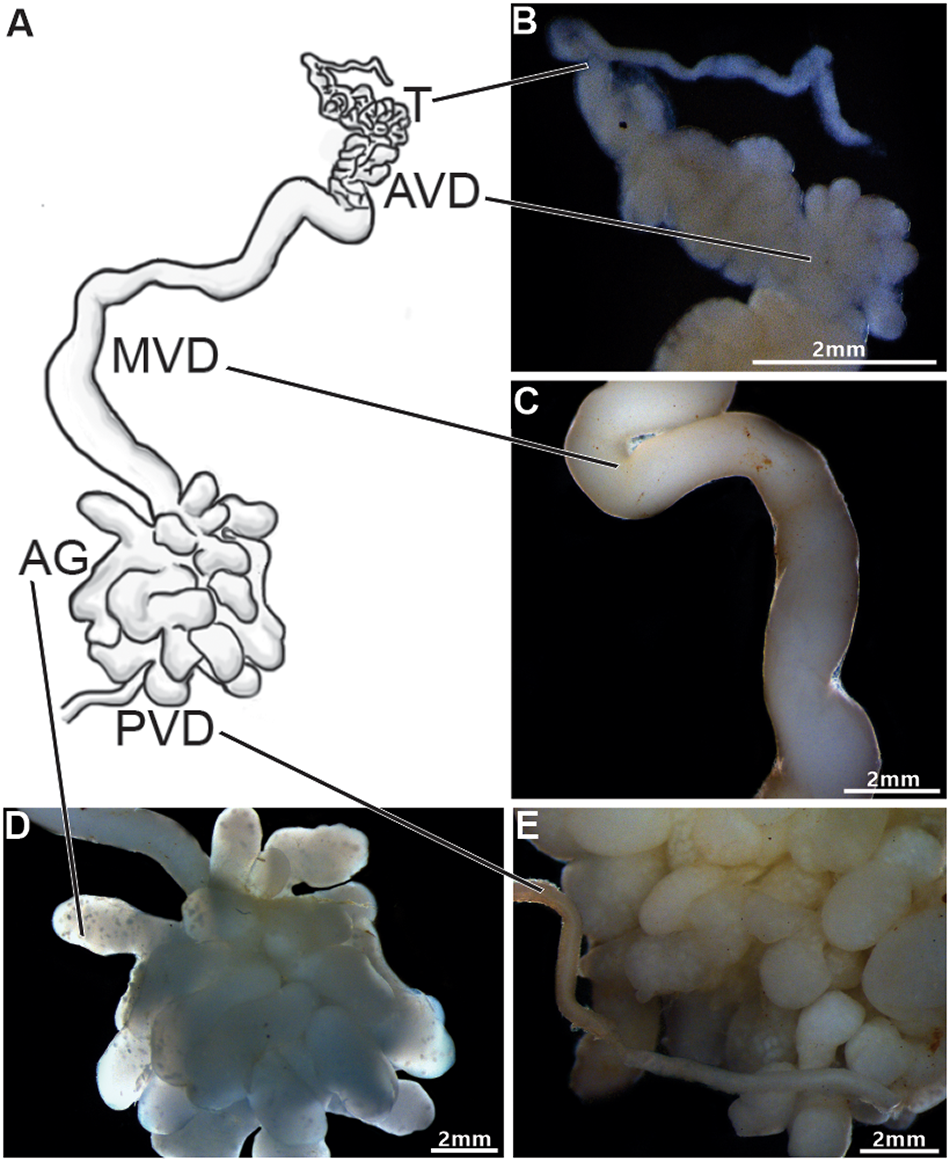

In J. lagostoma, the female reproductive system consists of a concave-type vagina, a pair of transversely paired ovaries connected to a pair of SRs through an oviduct located adjacent to the vagina, which is considered a ventral-type receptacle (Figure 6A–C). The vagina forms a dilated structure, with one of its faces collapsed against the other and associated with longitudinal musculature attached to the opposite face of the oviduct opening, both in the ventral region and along one of the vagina’s margins (Figure 6A–B). The vagina opens at the vulva (gonopores), which exhibit one of their faces protruding from the external surface (Figure 6A and 6D–E). In all females studied, the interior of the seminal receptacles was filled with a large amount of secretion; however, the SR did not have a rigid consistency (Figure 6E).

Figure 6. Anatomy of the female reproductive system (seminal receptacle) in Johngarthia lagostoma. (A) General view of the ventral-type seminal receptacle, with connection to the ovary through the oviduct. (B) Vagina with one face collapsed onto the other, showing longitudinal muscle attached to the oviduct opening. (C) Connection of the seminal receptacle to the oviduct. (D) Vagina opening into the vulva (arrow), near the gonopores. (E) Interior of the receptacles after rupture of the dorsal and ventral epithelium, showing a large amount of secretion, but with no rigid consistency (arrow). Dep, dorsal epithelium; G, gonopore; M, longitudinal musculature; Rs, seminal receptacle; Od, oviduct; Ov, ovary; Vep, ventral epithelium; Vg, vagina; Vu, vulva.

Histology and histochemistry

Histological sections confirmed the classification of the seminal receptacle as ventral-type, with the oviduct opening in the dorsal mesodermal region, near the transition area with the ventral ectodermal region (Figure 7A–C).

Figure 7. Histology of the seminal receptacle in female Johngarthia lagostoma. (A) General view of the seminal receptacle from the dorsal to the ventral region, associated with longitudinal musculature. (B) Detail of the ventral connection of the seminal receptacle with the oviduct, opening into the dorsal mesodermal region, near the area of transition to the ventral ectodermal region. (C) Nearly transverse section of the oviduct in the dorsal region of the ovary, highlighting the lining epithelium, as well as the presence of amorphous material filling the oviduct (arrow). (D) Detail of the dorsal region, composed of simple columnar or prismatic epithelium with elliptical nuclei. Note the presence of many fibroblasts (arrow) on the collagenous layer, stained with HE, along with a layer of connective tissue. (E) Detail of the dorsal epithelium showing varying heights due to the accumulation of secretory material. (F) Abrupt termination of the dorsal region (arrow). (G) Ventral region with numerous folds (arrow). (H) Detail of the folds in the ventral region, with cells formed by simple epithelium. (I) Detail of the epithelium in the ventral region with the connective tissue layer. (J) Epithelium of the vagina, with longitudinal muscle fibres present at the opening of the oviduct, associated with a collagenous layer. (K) Detail of the vaginal epithelium. Cl, connective tissue layer; Dep, dorsal epithelium; Dr, dorsal region; Ep, epithelium; M, longitudinal musculature; N, elliptical nuclei; Od, oviduct; Ov, ovary; Vr, ventral region.

The dorsal region of the seminal receptacle is composed of a simple columnar or prismatic epithelium, seated on connective tissue forming the collagenous layer, containing many fibroblasts as well as collagen fibres (Figure 7D–F). Additionally, the epithelial cells of the dorsal region have cytoplasmic secretory material at the apical pole, producing an appearance of different heights in the cells. The secretory vesicles have acidophilic areas with a basophilic central core, possibly released by a merocrine mechanism (Figure 7D–E).

The dorsal region of the seminal receptacle ends abruptly at the epithelium of the ventral region, which is covered by a thin cuticular layer at this point (Figure 7F).

The ventral region of the seminal receptacle, particularly opposite the oviduct opening, is characterized by the presence of numerous voluminous folds with cells formed by simple epithelium resting on the collagenous layer, which in some areas is anchored to muscle fibres (Figure 7F–I). The ventral region is continuous with the vagina, which is obliterated, with one face meeting the opposite margin of the vagina, producing a C-shaped appearance, classified as concave-type. Thus, the vaginal lumen is significantly reduced (Figure 7A and I). The vaginal epithelium has the same characteristics as the region opposite the oviduct opening; however, associated with the collagenous layer, many oblique muscle fibres are observed, present only on one of the faces (Figure 7J–K). Longitudinal muscle fibres are also observed along the vagina, positioned on the face coinciding, with the oviduct opening (Figure 7J).

The lumen of the seminal receptacle is filled with three types of secretions, in which sperm masses (wall-less spermatophores) or free spermatozoa are immersed. The secretion produced by the dorsal columnar epithelium is basophilic (SI), occurring in association with an acidophilic secretion (SII) (Figure 8A–C). Through histochemical analysis, it was found that the dorsal epithelium, SI, free spermatozoa, and sperm masses are reactive to proteins, whereas SII is strongly positive (Figure 8D–F). When subjected to PAS, SI and SII were strongly positive for neutral polysaccharides (Figure 8G–I). Regarding the presence of acidic polysaccharides, only SI (produced by the dorsal epithelium) was reactive, whereas SII was weakly positive and SIII was negative for this compound (Figure 8J–L; Table 1). Furthermore, areas without reactivity were detected in the lumen of the seminal receptacle for any histological techniques used (Figure 8C, F, I e K).

Figure 8. Histology and histochemistry of the secretions in the seminal receptacle of female Johngarthia lagostoma. (A) General view of the seminal receptacle, subjected to HE staining technique. (B) Detail of the seminal receptacle, with wall-less spermatophores immersed in secretion type one, produced by the dorsal columnar epithelium. (C) Seminal receptacle with spermatozoa and the additional presence of secretion one (acidophilic), showing reactivity to HE. (D) Seminal receptacle subjected to Xylidine Ponceau, with the dorsal epithelium and secretion one reacting for proteins. (E) Wall-less spermatophores reacting for proteins. (F) Secretion two strongly positive for proteins, surrounding the wall-less spermatophores. (G) Detail of the seminal receptacle subjected to PAS, with the dorsal epithelium and secretion one being strongly positive for neutral polysaccharides. (H) Secretion two surrounding the sperm masses, being strongly positive to the dye, while secretion three is negative. (I) Seminal receptacle showing the two secretions present and the sperm masses. (J) Seminal receptacle subjected to Alcian Blue, with secretion one produced by the dorsal epithelium reacting for acidic polysaccharides. (K) Spermatophores weakly positive, with secretion two weakly positive. (L) General view of the seminal receptacle, showing the two types of secretions and the sperm masses. Arrows indicate the loss of spermatophore walls. * indicate regions that do not show reactivity for any histological techniques used. Cl, connective tissue layer; Dep, dorsal epithelium; Sp, spermatophores; Sz, spermatozoa; SI, secretion one; SII, secretion two; SIII, secretion three.

Table 1. Histochemistry of the secretions of the vas deferens (males) and seminal receptacles (females) in Johngarthia lagostoma. Where: AVDp, anterior proximal vas deferens; MVD, median vas deferens; PVD, posterior vas deferens; SP, spermatophores; SI to SIV, secretion types I to IV; +++, strongly positive; ++, positive; +, weakly positive; and −, negative

Discussion

The present study provides the first anatomical, histological, and histochemical description of the male and female reproductive systems of the insular crab Johngarthia lagostoma. The male reproductive system of J. lagostoma is divided into a pair of testes, with their vasa deferentia and accessory glands arranged in an ‘H’ shape, similar to what has been described for the gecarcinid C. guanhumi (Shinozaki-Mendes et al., Reference Shinozaki-Mendes, Silva and Hazin2011) and other brachyuran species (Castilho et al., Reference Castilho, Ostrensky, Pie and Boeger2008; Krol et al., Reference Krol, Hawkins, Overstreet, Harrison and Humes1992; Shinozaki-Mendes and Lessa, Reference Shinozaki-Mendes and Lessa2018; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Sun, He, Li and Wang2015; Zara et al., Reference Zara, Toyama, Caetano and López-Greco2012). In turn, females exhibit paired gonads connected transversely, with a concave-type vagina (sensu Hartnoll, Reference Hartnoll1968) and a pair of seminal receptacles connected ventrally to the oviduct (sensu Diesel, Reference Diesel, Bauer and Martin1991), with no presence of sperm packets or the formation of sperm plugs within. This morphological model is similar to the one described for C. guanhumi by Souza et al. (Reference Souza, Silva, Araujo and Camargo-Mathias2013), and is widely common among crabs of the Thoracotremata Guinot, 1977 (for review, see McLay and López-Greco, Reference McLay and López-Greco2011).

Male reproductive system

The testes of J. lagostoma was histologically classified as tubular, similar to the pattern described for other species of Thoracotremata, such as those of the genus Pachygrapsus Randall, 1840 (Chiba and Honma, Reference Chiba and Honma1972; Tiseo et al., Reference Tiseo, Mantelatto and Zara2014). However, it differs from the lobular type reported for C. guanhumi by Shinozaki-Mendes et al. (Reference Shinozaki-Mendes, Silva and Hazin2011), which is the testicular type typically observed in most crabs (Nascimento and Zara, Reference Nascimento and Zara2013; Simeó et al., Reference Simeó, Ribes and Rotllant2009; Zara et al., Reference Zara, Toyama, Caetano and López-Greco2012). In J. lagostoma, cells at different stages of spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis are present within the same testicular tubule, suggesting that cellular development does not occur synchronously. Despite this, synchronization in the development of these cells has been previously reported by Johnson (Reference Johnson1980), and it was also verified for C. guanhumi, where the germ cells are at the same stage in each tubule in the maturation zone (Shinozaki-Mendes et al., Reference Shinozaki-Mendes, Silva and Hazin2011). At the beginning of spermatogenesis in J. lagostoma, spermatogonia are located at the periphery of the seminiferous tubule, forming the germinal zone, following the germinal centre pattern observed for portunids (Johnson, Reference Johnson1980; Nascimento and Zara, Reference Nascimento and Zara2013; Ryan, Reference Ryan1967; Zara et al., Reference Zara, Toyama, Caetano and López-Greco2012). In C. guanhumi, spermatogonia were observed on opposite sides, not close to the evacuation zone, which in this case only contains spermatozoa (Shinozaki-Mendes et al., Reference Shinozaki-Mendes, Silva and Hazin2011). The same pattern was found by Simeó et al. (Reference Simeó, Ribes and Rotllant2009) for Maja brachydactyla Balss, 1922. It is possible to analyse, both during spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis, a reduction in the cell nucleus until the formation of the mature spermatozoon, which is present in the evacuation zone. This same pattern has already been observed for other brachyurans, such as Ucides cordatus (Linnaeus, 1763), according to Castilho et al. (Reference Castilho, Ostrensky, Pie and Boeger2008); Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896, by Johnson (Reference Johnson1980); Portunus pelagicus (Linnaeus, 1758), studied by Ravi et al. (Reference Ravi, Manisseri and Sanil2014); Callinectes danae (Smith, 1869), as per Zara et al. (Reference Zara, Toyama, Caetano and López-Greco2012); and Callinectes ornatus Ordway, 1863, according to Nascimento and Zara (Reference Nascimento and Zara2013). However, such nuclear reduction was not observed during the spermiogenesis of M. brachydactyla (Simeó et al., Reference Simeó, Ribes and Rotllant2009).

The division of the vas deferens into three regions (AVD, MVD, and PVD) for J. lagostoma is commonly proposed for other Brachyura species (Krol et al., Reference Krol, Hawkins, Overstreet, Harrison and Humes1992). Additionally, based on histological and histochemical differences in the AVD, it was possible to subdivide it into proximal and distal regions (AVDp and AVDd, respectively), due to the storage of spermatozoa from the testes and the production of seminal fluid. This fluid, produced in AVDd, plays an important role in the formation of the wall of the coenospermic spermatophores, which house a large quantity of spermatozoa immersed in the extracellular matrix, being the predominant packing pattern in Thoracotremata. Several families within Brachyura exhibit coenospermic spermatophores, including: Grapsidae MacLeay, 1838 (Garcia and Silva, Reference Garcia and Silva2006Nicolau et al., Reference Nicolau, Nascimento, Machado-Santos, Sales and Oshiro2012; Tiseo et al., Reference Tiseo, Mantelatto and Zara2014); Ocypodidae Rafinesque, 1815 (Castilho et al., Reference Castilho, Ostrensky, Pie and Boeger2008); Pinnotheridae De Haan, 1833 (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Klaus and Tudge2013); and Sesarmidae Dana, 1851(Santos et al., Reference Santos, Lima, Nascimento, Sales and Oshiro2009). The differential dehiscence rate varies between types of spermatophores, being higher in cleistospermic ones, which contain only one germ cell per spermatophore, and are related to species-specific reproductive strategies (Guinot et al., Reference Guinot, Jamieson and Tudge1997; Klaus and Brandis Reference Klaus and Brandis2011; Klaus et al., Reference Klaus, Schubart and Brandis2009; Tiseo et al., Reference Tiseo, Mantelatto and Zara2014). For J. lagostoma, analyses of SR contents revealed only the presence of free spermatozoa or masses of spermatozoa without the spermatophore walls, as also demonstrated in other Stenorhynchus seticornis (Herbst, 1788) (Antunes et al., Reference Antunes, Zara and Negreiros-Fransozo2016). However, males showed both coenospermic spermatophores and seminal secretions (both internal and external to the spermatophores) in the distal regions of the vas deferens, which demonstrated reactivity to acidic polysaccharides, indicating a possible relationship with spermatophore dehiscence.

In the MVD and PVD of J. lagostoma, spermatophores are immersed in a large amount of seminal fluid, consisting of a homogeneous matrix, in which secretion granules are embedded. Additionally, the accessory glands, recorded in the MVD–PVD transition region, contribute to the production of a larger amount of granular material, which is released into the PVD after the glands open. A similarity can be observed between the secretions produced by the vas deferens and the accessory glands, suggesting that the process is related to the increased production and final volume of seminal fluid, which may serve distinct functions, such as assisting in the conduction of spermatophores and spermatozoa during sperm transfer (Benhalima and Moriyasu, Reference Benhalima and Moriyasu2000; Johnson Reference Johnson1980; Sainte-Marie and Sainte-Marie Reference Sainte-Marie and Sainte-Marie1998; Zara et al., Reference Zara, Toyama, Caetano and López-Greco2012); enabling the formation of sperm packets (Antunes et al., Reference Antunes, Zara and Negreiros-Fransozo2016; Garcia-Bento et al., Reference Garcia-Bento, López-Greco and Zara2019; Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, López-Greco and Zara2022); and nourishing the spermatozoa in the seminal receptacles (Diesel Reference Diesel1989; Sant’Anna et al., Reference Sant’Anna, Pinheiro, Mataqueiro and Zara2007; Zara et al., Reference Zara, Raggi Pereira and Sant’Anna2014). In this regard, in the seminal receptacles of J. lagostoma, as in most Thoracotremata, a mixture of free spermatozoa in secretion occurs, indicating that the seminal fluid from the vas deferens is helping to increase the flow, optimizing the transfer of sperm to the female’s seminal receptacle (Antunes et al., Reference Antunes, Zara and Negreiros-Fransozo2016; Assugeni and Zara, Reference Assugeni and Zara2022; Diesel, Reference Diesel1989; Sal Moyano et al., Reference Sal Moyano, Gavio and Cuartas2010; Spalding, Reference Spalding1942).

Female reproductive system

Johngarthia lagostoma presents a concave type of vagina (sensu Hartnoll, Reference Hartnoll1968), following the characteristic pattern for Thoracotremata (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Brandis and Storch2011; Hartnoll, Reference Hartnoll1968; Lautenschlager et al., Reference Lautenschlager, Brandis and Storch2010; McLay and Becker Reference McLay, Becker, Castro, Davie, Guinot, Schram and Von vaupel klein2015; Souza et al., Reference Souza, Ogawa, Silva and Camargo‐Mathias2017; Vehof et al., Reference Vehof, Van der Meij, Türkay and Becker2015). This type of vagina is also observed in some Heterotremata Guinot, 1977, including the majid crabs Hyas araneus (Linnaeus, 1758), Hyas coarctatus Leach, 1815 (Hartnoll, Reference Hartnoll1968), and Inachus phalangium (Fabricius, 1775) (Diesel, Reference Diesel1989). In the concave type of vagina, the muscles are predominantly attached internally to the flexible side of the vagina, forming a crescent-shaped configuration. This structure allows the female to exert control over the movement of the vaginal lumen during copulation and fertilization, assisting in the loss of fluids, an important function for crabs inhabiting terrestrial environments. This regulation also plays a key role in controlling the penetration of gonopods during sperm transfer and the transport of sperm deposited in the vagina towards the seminal receptacles (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Brandis and Storch2011; Diesel, Reference Diesel1989; Hartnoll, Reference Hartnoll1968; Lautenschlager et al., Reference Lautenschlager, Brandis and Storch2010; Souza et al., Reference Souza, Ogawa, Silva and Camargo‐Mathias2017). Hartnoll (Reference Hartnoll1968) described another type of vagina, referred to as simple, characterized by a stiffer, rounded lumen in cross-section, with this pattern occurring in other families within the Heterotremata subsection. The distribution of different types of vagina among brachyurans suggests that the simple form is more likely to be considered primitive, while the concave form would be a secondary derivation (Hartnoll, Reference Hartnoll1968; Vehof et al., Reference Vehof, Scholtz and Becker2017).

Regarding the seminal receptacles (SR), a ventral connection with the oviduct was observed, aligning with the pattern seen in other Thoracotremata (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Brandis and Storch2011; Lautenschlager et al., Reference Lautenschlager, Brandis and Storch2010; López-Greco et al., Reference López-Greco, Fransozo, Negreiros-Fransozo and Santos2009, Reference López-Greco, López and Rodríguez1999; McLay and López-Greco, Reference McLay and López-Greco2011; Souza et al., Reference Souza, Ogawa, Silva and Camargo‐Mathias2017, Reference Souza, Silva, Araujo and Camargo-Mathias2013), particularly in more derived species within the Grapsoidea-Ocypodoidea clade (McLay and López-Greco, Reference McLay and López-Greco2011). According to Brink and McLay (Reference Brink and McLay2009), the position of the connection to the receptacle influences the fertilization process of species. In those where this connection is ventral, the sperm from the last male to copulate with the female is preferred for fertilizing the oocytes, while sperm from earlier copulations are pushed further away and are more distant from the ventral region, where the oocytes are released into the seminal receptacle (McLay and Becker, Reference McLay, Becker, Castro, Davie, Guinot, Schram and Von vaupel klein2015; McLay and López-Greco, Reference McLay and López-Greco2011).

Some species employ different strategies to ensure paternity, such as the display of pre- and post-copulatory behaviors (e.g., guarding embraces) (for review, see Guinot et al., Reference Guinot, Tavares and Castro2013; McLay and Becker, Reference McLay, Becker, Castro, Davie, Guinot, Schram and Von vaupel klein2015). Hartnoll et al. (Reference Hartnoll, Mackintosh and Pelembe2006) highlighted the presence of pre-copulatory guarding behaviour in J. lagostoma, although João et al. (Reference João, Kriegler, Freire and Pinheiro2021) did not record any form of guarding by females before or after copulation. According to the latter authors, the differing findings can be explained by the species’ behavioural plasticity on each island, which would be understandable given that on Trindade Island, J. lagostoma occupies a top predator position in the terrestrial environment, unlike on Ascension Island. However, guarding behaviors are not common in crabs with a higher degree of terrestriality (McLay and Becker, Reference McLay, Becker, Castro, Davie, Guinot, Schram and Von vaupel klein2015), being confirmed in Thoracotremata almost exclusively for some varunid species, such as Hemigrapsus sexdentatus (H. Milne Edwards, 1837), where males embrace females until they extrude their eggs (Brockerhoff and McLay, Reference Brockerhoff and McLay2005).

In Eubrachyura, the seminal secretion transferred during copulation can form sperm packages or spermatophores inside the seminal receptacles (Antunes et al., Reference Antunes, Zara and Negreiros-Fransozo2016; Assugeni et al., Reference Assugeni, Toyama and Zara2021; Beninger et al., Reference Beninger, Elner, Foyle and Odense1988; Diesel, Reference Diesel1989; Guinot et al., Reference Guinot, Tavares and Castro2013; Hartnoll, Reference Hartnoll1969; Zara et al., Reference Zara, Raggi Pereira and Sant’Anna2014, Reference Zara, Toyama, Caetano and López-Greco2012). These sperm packages contribute to sperm competition, depending on the positioning of the oviduct (dorsal, ventral, or intermediate), the fertilization of the oocytes may favour the gametes of a specific male (Antunes et al., Reference Antunes, Zara and Negreiros-Fransozo2016; Beninger et al., Reference Beninger, Elner, Foyle and Odense1988; Diesel, Reference Diesel1989). The spermatophore plug, prevents the loss of sperm after copulation and also prevents subsequent copulations by temporarily occluding the seminal receptacles, vagina, and gonopores (Assugeni et al., Reference Assugeni, Toyama and Zara2021; Guinot et al., Reference Guinot, Tavares and Castro2013; Hartnoll, Reference Hartnoll1969; Hines et al., Reference Hines, Jivoff, Bushmann, Van Montfrans, Reed, Wolcott and Wolcott2003; McLay and Becker, Reference McLay, Becker, Castro, Davie, Guinot, Schram and Von vaupel klein2015; Zara et al., Reference Zara, Raggi Pereira and Sant’Anna2014, Reference Zara, Toyama, Caetano and López-Greco2012). Sperm packages and spermatophore plugs were not observed in J. lagostoma, but histological analysis revealed that the seminal receptacles were filled with free sperm immersed in secretions. Therefore, in J. lagostoma, there appears to be a simple transfer from a single male, or if the female accepts more than one male, with successive copulations – as theorized by João et al. (Reference João, Kriegler, Freire and Pinheiro2021) – the male genetic material is mixed within the seminal receptacle. This is consistent with the absence of guarding behaviours, sperm package formation, and spermatophore plugs in the seminal receptacles. This knowledge gap highlights the need for further studies on this subject, directed at a possible selection process at the cellular level in this species, as well as exploring other strategies, such as the differential morphology of the gonopods and their use during copulation.

The dorsal region of the seminal receptacle in J. lagostoma terminates abruptly, without a transitional zone between the dorsal and ventral epithelia, such as the presence of a “velum” seen in a few majid crabs (Diesel, Reference Diesel1989; González-Pisani et al., Reference González-Pisani, Barón and López-Greco2012) or modified dorsal epithelium, as recorded in portunid crabs (see Assugeni et al., Reference Assugeni, Toyama and Zara2021; Zara et al., Reference Zara, Raggi Pereira and Sant’Anna2014). However, J. lagostoma exhibits prominent folds in the ventral region of the seminal receptacle, particularly opposite the oviduct opening. These cuticular folds were also observed in other Thoracotremata crabs, such as Pinnotheres pisum (Linnaeus, 1767), Pinnotheres pectunculi Hesse, 1872, Nepinnotheres pinnotheres (Linnaeus, 1758), Cyrtograpsus angulatus Dana, 1851, Neohelice granulata (Dana, 1851), and O. quadrata (Fabricius, 1787) (see Becker et al., Reference Becker, Brandis and Storch2011; López-Greco et al., Reference López-Greco, Fransozo, Negreiros-Fransozo and Santos2009). According to these studies, the folds in the cuticular region may aid in the mixing of sperm and oocytes, as well as allowing the expansion of the seminal receptacle, maximizing its sperm storage capacity and fertilization potential.

In the lumen of the seminal receptacle of J. lagostoma, two secretions (SI and SII) were observed, along with free sperm or small sperm clusters. SI appears to originate from the dorsal columnar epithelium of the seminal receptacle, associated with the production of polysaccharides while the SII seem to come from the males eyaculate, considering the histochemical similarity to those recorded in the vas deferens. Polysaccharides secretions may help maintain sperm during sperm transfer and storage in the seminal receptacles (Anilkumar et al., Reference Anilkumar, Sudha and Subramoniam1999; Diesel, Reference Diesel1989). According to Anilkumar et al. (Reference Anilkumar, Sudha and Subramoniam1999), a temporal analysis of the seminal receptacle of newly copulated females of the grapsoid Metopograpsus messor (Forskål, 1775) showed that 72 hours after mating, the spermatophore wall dissolved, leaving only free sperm, suggesting that this process is triggered by female fluids. On the other hand, for the varunid Eriocheir sinensis H. Milne Edwards, 1853, it is described that the dissolution of the spermatophore wall was more efficient when the seminal fluids produced by the male accessory glands were mixed with the fluids from the females (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Mao, He, Gong, Qu and Wang2010). For J. lagostoma, the presence of male and female secretions in the lumen of the seminal receptacle was verified, as well as the absence of spermatophores with walls, similar to what was observed for E. sinensis. However, the authors provided empirical evidence supporting the efficiency of spermatophore dissolution for the species, and further studies similar to those for J. lagostoma are needed to verify whether the secretions found in the lumen reflect this process.

In addition to the secretions found in the seminal receptacles (SR), colourless areas with no chemical reactivity to the histological techniques used were also detected. It is supposed that these regions correspond to water influxes resulting from sperm transfer, a feature previously reported in studies on Chionoecetes opilio (Fabricius, 1788) (Diesel, Reference Diesel, Bauer and Martin1991; Sainte-Marie et al., Reference Sainte-Marie, Sainte-Marie and Sévigny2000) and C. danae (Assugeni et al., Reference Assugeni, Toyama and Zara2021). The role of water in sperm transfer in crabs has been widely discussed (Assugeni et al., Reference Assugeni, Toyama and Zara2021; Becker et al., Reference Becker, Brandis and Storch2011; Beninger et al., Reference Beninger, Elner, Foyle and Odense1988; Brown Reference Brown1966; Medina, Reference Medina1992; Sainte-Marie et al., Reference Sainte-Marie, Sainte-Marie and Sévigny2000; Watson, Reference Watson1972), and one possible function would be the dilution of seminal fluid during its passage through the gonopods during copulation (Assugeni et al., Reference Assugeni, Toyama and Zara2021; Beninger et al., Reference Beninger, Elner, Foyle and Odense1988). However, it is still unclear how these water influxes occur in the SR of J. lagostoma, as this species exhibits a higher degree of terrestriality (Marin and Tiunov, Reference Marin and Tiunov2023). This fact distinguishes this species from the aquatic ones previously mentioned, whose biological events are not limited by this resource. Terrestrial crabs face limitations in water access and, therefore, have developed adaptations that favour their acquisition and retention, ensuring greater water independence (see Pinheiro et al., Reference Pinheiro, Dias-Silva, Kriegler, Santana and João2024 and references therein). In J. lagostoma, for example, there is a ventral tuft of hydrophilic setae located between the 5th pereiopod and the margins of the 1st–2nd pleonal somites, which aids in water retention (Bliss, Reference Bliss, Whittington and Rolfe1963; Guinot et al., Reference Guinot, Ng and Moreno2018; Oliveira, Reference Oliveira2014; Pinheiro et al., Reference Pinheiro, Dias-Silva, Kriegler, Santana and João2024), facilitating the capture of water from the environment they inhabit.

In conclusion, for J. lagostoma, both the male and female reproductive systems follow the basic pattern previously described for Thoracotremata crabs. In males, the presence of coenospermic spermatophores immersed in seminal fluid is observed starting from the AVDd and extending along the other regions of the vas deferens, where different types of secretions are produced and surround the spermatophores. The accessory glands, located at the transition between the MVD and PVD, produce secretion type IV (SIV), characterized by basophilic granules strongly positive for neutral polysaccharides. Based on this profile, SIV may function as a matrix that spaces and stabilizes spermatophores, contributing to sperm protection and transfer (McLay and López-Greco, Reference McLay and López-Greco2011).

In females, the seminal receptacle follows the traditional pattern described for Thoracotremata, with the dorsal mesodermal region composed of simple columnar epithelium with a merocrine secretion mechanism, without any evidence of apocrine secretion. There is no cellular shedding, i.e., no holocrine mechanism, as described for Heterotremata (Assugeni et al., Reference Assugeni, Toyama and Zara2021; Becker et al., Reference Becker, Brandis and Storch2011, Reference Becker, Klaus and Tudge2013, Reference Becker, Turkay and Brandis2012; Zara et al., Reference Zara, Raggi Pereira and Sant’Anna2014). Spermatophore plugs and spermatophore packages were absent from the studied species. Additionally, no spermatophores with walls were observed inside the seminal receptacles, only free sperm or small clusters of sperm immersed in secretion. We speculate that the secretion produced by the females, derived from the mesodermal epithelium, and the secretions transferred by the males, may, in addition to maintaining the sperm, influence spermatophore dehiscence and facilitate the fertilization process.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Brazilian Navy (First District), Inter-ministerial Secretariat for Marine Resources (SECIRM) and ‘Programa de Pesquisas Científicas da Ilha da Trindade’ (PROTRINDADE), under the commander C. C. Vitória-Régia, who guaranteed our presence in Trindade Island and helped with the project logistic. We thank members of the ‘Projeto Caranguejos de Ilhas Oceânicas’ for help during the field sampling. We thank Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio) by the sample permission supported by Sistema de Autorização e Informação da Biodiversidade (SISBIO # 65446). EEDM acknowledges the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for financial support during their master’s studies (CNPq # 131436/2024-4), Dr. Nicholad Kriegler for participating in field sampling activities and Dr. Caio Santos Nogueira and Ms. Laira Lianos for critical reading of the master’s qualification that originated this manuscript. MAAP thanks ‘National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for the financial support provided by Universal Project (CNPq # 404224-2016) and for the Research Productivity Fellowship (CNPq # 305957/2019-8 and # 307482/ 2022-7). MCAJ acknowledges the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for financial support during their doctoral studies (CNPq # 140137/2024-6). FJZ acknowledges the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) for JP #2005/04707-5; BIOTA Intercrusta #2019/13685-5; ProFix #2024/01947-6; and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for logistical/financial support (Projeto PPBio 2023 – 07/2023 – Linha 8: Rede Costeira Marinha Proc. #442421/2023-0) and the Research Productivity Fellowship (CNPq #308324/2023-4). MAGB acknowledges the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for financial support during their doctoral studies (CNPq #40236/2019-8). This study was conducted in accordance with Brazilian National System of Management of Genetic Heritage (SisGen) under cadaster A4DA42C.

Author contributions

MAAP and FJZ conceived and designed the study. MCAJ coordinated the field sampling activities. EEDM and MAGB carried out the fieldwork and laboratory analyses and processed the figures. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results, manuscript writing, and critical revision, and approved the final version for submission.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Ethical standards

This work was carried out in accordance with the following ethical licenses: SISBIO #65446 For collecting specimens on Trindade Island and SisGen cadaster A4DA42C for histological and histochemical analyses.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study will be available in the UNESP Institutional Repository upon publication. Until then, the datasets are available from the corresponding author (EEDM) upon reasonable request.