Introduction

Top-down inspections constitute a prevalent oversight mechanism in governance systems worldwide. In the existing literature, scholars have extensively debated the relationship between such inspections and governance performance, revealing two predominant patterns in existing literature. First, research has predominantly focused on sector-specific business inspections—technical reviews grounded in domain expertise (e.g., education, healthcare, environmental regulation, housing). Second, studies have largely examined the direct effects of inspections on targeted entities. Departing from this established focus, this article investigates China’s central political inspections and their indirect governance consequences at the municipal level. Specifically, we posit that China’s central political inspections trigger improvements in the provision of invisible public goods by local governments.

Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, central political inspections have evolved into an important component of the nation’s top-down oversight regime. Distinct from conventional administrative reviews, China’s political inspections are party-initiated monitoring mechanisms rather than professionally led governmental procedures. During implementation, inspection teams circumvent local information monopolies through autonomous evidence-gathering channels, prioritizing assessments of provincial officials’ political loyalty and integrity over technical competence or performance metrics. Consequently, inspection outcomes directly imperil the political survival of provincial leaders while simultaneously generating deterrent effects that extend to municipal officials facing inspection pressures.

In order to mitigate political risk, municipal officials occasionally engage in proactive corrective actions, which often improve the provision of invisible public goods. Following Mani and Mukand (Reference Mani and Mukand2007), we define such goods as those whose government provision capacity is difficult to evaluate based on observable outcomes. Urban infrastructure systems like underground pipelines and natural gas networks exemplify invisible public goods. Since these facilities are largely hidden or obscured from public view, citizens struggle to intuitively assess their quality through direct observation. More importantly, invisible public goods also exhibit two defining characteristics: (1) Public evaluation is conditional, only becoming viable under specific circumstances (e.g., extreme weather events or system failures); and consequently, (2) public assessment of quality typically involves a significant time lag. Due to these attributes, politicians frequently prioritize allocating limited resources towards goods that are more visible and directly linked to personal career advancement. Paradoxically, this tendency inherently transforms inadequate provision of invisible public goods into a significant career risk for officials. However, the deterrence effect of central political inspections can motivate rational officials to reallocate resources, thereby correcting the undersupply of these invisible public goods.

Literature review

By definition, inspections constitute an institutional mechanism through which organizations monitor subordinate entities’ behavioral compliance and performance outcomes. The defining feature of this approach is the on-site verification process, wherein inspectors engage in direct observation of service providers, scrutinizing operational procedures and documentary evidence directly (Boyne et al., Reference Boyne, Day and Walker2002). Like other monitoring mechanisms, inspection effectiveness remains contingent upon contextual variables, rendering its sophisticated impact on governance performance a persistent focus of empirical scholarship.

Within the political economy of inspection, Hemenway is one of the early representative scholars. Based on the in-depth observation of the inspection process across nine domains, including occupational health and safety, housing, restaurants, grain, buildings, nursing homes and so on, Hemenway (Reference Hemenway1985) demonstrated that the inspector’s independence and legal authority, and other environmental factors, fundamentally shape inspection vulnerability. While this early work yields many valuable insights, it did not go beyond these enlightening descriptions to establish a more general analytical framework. This theoretical gap prompted Boyne and his coauthors to develop their contribution. In constructing a general theoretical framework for evaluating public service inspection, Boyne et al. (Reference Boyne, Day and Walker2002) identified three elements that facilitate inspection effectiveness (a director, a detector, and an effector), five potential problems that impede it (resistance, ritualistic compliance, regulatory capture, performance ambiguity and information asymmetry), and a critical mediating variable of inspector expertise.

The framework proposed by Boyne et al. systematically encompasses core issues related to inspection quality. Inspired by this framework, subsequent scholarship has progressively explored the implementation of inspection across domains, with a particular focus on the impact of inspection processes on improving governance performance in specific policy contexts. For example, in European education governance, inspection embodies “governing at a distance” (Clarke Reference Clarke, Grek and Lindgren2015), with England’s Ofsted, Sweden’s legalistic model, and Scotland’s collaborative approach forming distinct inspection regimes. These regimes reflect varied strategies for reconciling neoliberal pressures, market accountability, decentralization, and performance metrics, with traditional welfare-state commitments to equity (Grek and Lindgren Reference Grek, Lindgren, Grek and Lindgren2015). Environmental regulation studies offer a contrasting perspective, empirically demonstrating the effectiveness of targeted discretion. For instance, research in India found that doubling random inspections yielded minimal pollution reduction. Conversely, inspections leveraging regulators’ local knowledge and discretion to target likely violators proved significantly more effective (Duflo et al. Reference Duflo, Greenstone, Pande and Ryan2018). This highlights the value of professional judgment over mechanistic application of rules. The value of discretion and local knowledge is further reaffirmed in studies of labor inspection across Latin America (Piore and Schrank Reference Piore and Schrank2008, Reference Piore and Schrank2006). According to this research, the Latin model’s flexibility, allowing inspectors to tailor enforcement based on firm context (e.g., compliance capacity, economic vulnerability), emerges as crucial for achieving substantive outcomes rather than mere procedural compliance.

In recent years, the impact of inspections on local governance has also been a prominent research focus within China studies. Following the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2012, the central government intensified monitoring efforts and introduced some novel oversight mechanisms to address principal-agent problems among local officials, while maintaining performance-based incentive schemes (Ma Reference Ma2021). Scholars have extensively analyzed these adaptations within China’s supervisory framework, with particular attention to how central environmental inspections reshape environmental governance outcomes. Some researchers contend that such inspections fail to correct local deviations from central policies, thereby limiting their effectiveness in addressing pollution. Zheng and Na (Reference Zheng and Na2020) demonstrated that while inspected provinces showed statistically significant air quality improvements, these gains proved transient. Xiao et al. (Reference Xiao, Hou and Lovely2025) provide a compelling explanation for this short-term effect: China’s “under-institutionalized” public accountability system prevents top-down inspections from overcoming entrenched organizational inertia. Consequently, local policymaking discretion tends to rebound toward its original status once the high risk of blame caused by top-down inspection is no longer a concern (Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Hou and Lovely2025). Ma et al. (Reference Ma, Wang and Chen2025) reached parallel conclusions through analyzing corporate political connections. Their findings indicate that such connections correlate positively with increased pollution emissions, particularly in counties with stringent environmental regulations.

Conversely, other scholars present alternative perspectives. Zhu and Wang (Reference Zhu and Wang2025) maintain that multi-wave inspection schemes enable the central government to credibly signal its emphasis on certain policies and intentions to punish noncompliance, thereby achieving long-term pollution reduction. Dong et al. (Reference Dong, Liu, Zhang, Jiang, Wang, Zhang, Shu, Sun and Bi2024) proposed an alternative mechanism, arguing that central inspections mobilize public complaints which, when coupled with follow-up inspections, significantly improve air quality. Li et al. (Reference Li, Zhou, Bi, Liu and Li2020) offer a much easier explanation: China’s local environmental governance is undergoing a promising shift from passive to active engagement due to the implementation of the “Balanced Scorecard” (BSC) performance evaluation system. The BSC’s comprehensive metrics, incorporating both short- and long-term objectives alongside stakeholder considerations, effectively rectify distorted behaviors among local governments (Li et al. Reference Li, Zhou, Bi, Liu and Li2020).

This review of prior research on the relationship between inspection and governance performance reveals two recurring characteristics in the literature. First, existing studies predominantly examine business inspections—specialized evaluations initiated and conducted by superior departments to assess subordinate entities’ professional competence and performance. For instance, current scholarship on China’s inspection systems focuses heavily on the implementation and efficacy of central environmental inspections. Second, scholars concentrate primarily on inspections’ direct impacts on inspected entities and objectives, such as educational inspections improving equity, labor inspections enhancing productivity, or environmental inspections reducing pollution. Nevertheless, a limited number of researchers note that since National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2012, China’s supervisory framework has expanded beyond business inspections to include new political oversight mechanisms—the central political inspections. Yeo (Reference Yeo2016) characterized this innovation as an institutional compensation to the existing discipline inspection commission. However, scholarly attention to the newly introduced political inspections and their indirect governance effects remains scarce. This article addresses this gap in the literature.

The central political inspection and the provision of invisible public goods

The absence of an effective accountability system has been a long-standing challenge for many countries across the world. China is not an exceptional case. To make up for its institutional deficiencies and hold its members to account, the Communist Party of China (CPC) has rejuvenated the inspection system since Xi Jinping took office in late 2012. Despite some limitations, the political inspection of provincial governments exerts an indirect effect on correcting the insufficient provision of invisible public goods at the municipal level. This section provides qualitative evidence for how this corrective effect forms.

Inspection (xunshi), as a top-down monitoring tool, is not novel in the history of the CPC. Before coming to power, the central committee of the CPC often sent commissioners to every grassroots party organization with the aim of disciplining its members’ behaviors and consolidating internal cohesiveness for the sake of victory in the war (The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection of the CPC 2015). After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the inspection system did not work until 1990, when the Decision of the CPC Central Committee on Strengthening Ties between the Party and the People passed in the sixth Plenary Session of the 13th CPC Central Committee. Since then, the top-down inspection from Beijing has episodically occurred as a complement to the party’s routine surveillance system.

Circumstances changed when Xi Jinping took office in late 2012. Manion (Reference Manion2016) indicated that, in Xi’s era, the inspection campaign far exceeded its predecessors in intensity and scope. Manion’s observation is right, but she does not capture the full picture of the change. According to Li and Ma (Reference Li and Ma2020), since 2012 the inspection system has undergone a series of changes with regard to its purposes, methods, scope, and consequences. Prominently featured in the current inspection system is the political discipline function (Deng and Tan Reference Deng and Tan2025). The recently issued Inspection Regulations explicitly codify this political mandate, stipulating core objectives including: verifying subordinate units’ implementation of Party lines, principles, policies, and major decisions; strengthening Party organizational development; cultivating party members and cadres; preserving Party unity; and maintaining the Party’s advanced nature. Additionally, inspections fulfill a critical anti-corruption function by identifying clues and providing evidentiary support for integrity investigations. Standard protocols require examining whether leading cadres of Party committees in secondary units maintain probity standards.

The content of reports from inspection teams provides some convincing evidence of the inspections’ political focus. From 2013 to 2017, Beijing had undertaken 12 rounds of inspections that covered all central ministries, provincial governments, state-owned enterprises, and universities under the Ministry of Education. Li and Wu (Reference Li and Wu2019) conducted a content analysis of the reports from these inspections. They found that among the most frequently used keywords were accountability, supervision, political integrity, political discipline, and anti-corruption. As for the distribution of the most-discussed issues in the reports, the top three were economic corruption, consciousness of political integrity, and bad conduct. In short, the nature of the inspection system under the Xi administration, as Xi said in his report to the 19th CPC National Congress, is politically aimed at discovering, correcting, and punishing party members’ misconduct.

The rejuvenated political inspection system is much more than a symbol, but it can play substantially deterrent roles in disciplining officials at lower levels. Talking is a legal method for investigation; it is also a critical tool for communicating the deterrence to officials who are summoned by the inspection teams. From 2013 to 2017, during the 12 rounds of inspections, the inspection teams sent from Beijing interviewed 53,000 officials, which led to the leveling of various warnings and punishments against 450,000 party members (The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection of the CPC 2017). The deterrence effect comes not only from the scope of the conversation, but also from the process of participating in it. According to Article 21 of Chapter 5 of the “Regulations on the Inspection of the CPC” (Central Committee of the Communist Party of China 2015), prior to conducting inspections the inspection team shall inquire about the leading officials and members of the party organizations who are under investigation by the discipline inspection organs, auditing departments, petition office, and others at the same level. Following this procedure, when the inspection team conducts interviews, it is not working empty-handed but often already possesses some information. As a result, this well-prepared investigation delivers a clear signal to the interviewees about Beijing’s capacity and determination to put an end to the official’s rule-violating behaviors. Although there is no evidence suggesting that this is Beijing’s intentional strategy, this expanded deterrence effect does exist. Wang (Reference Wang2022) even makes the rather extreme argument that the inspection campaign has widely reduced the productivity of bureaucrats and frightened them away from working.

In addition to meeting with local officials and engaging in face-to-face communications with relevant personnel, inspection teams systematically gather information by facilitating public participation. During the inspection period, citizens may report official misconduct through five designated channels: (1) National unified reporting hotline 12388 (2) Central inspection team dedicated hotline (3) Postal mailbox (4) Online platform (website/APP) (5) On-site receptions. Contact details for these channels will be released to the public through official announcements after the inspection team is stationed in the inspected area. During the 18th Central Political Inspection, the Central Inspection Team received more than 1.59 million letters and visits, and communicated with citizens and party members more than 53,000 times.

In summary, following the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, the central political inspection is a new top-down control method introduced by Xi’s administration within the existing supervision system. Compared with international counterparts and China’s existing business inspections, central political inspections exhibit four distinctive features. First, they constitute party-initiated oversight activities rather than evaluations conducted by higher-level administrative agencies, positioning them as core components of the intra-party oversight framework. Second, their primary focus shifts from assessing subordinate leaders’ professional competence and performance to evaluating political loyalty and integrity toward central authorities, thereby ensuring effective power centralization. Third, through direct consultations and public mobilization channels, these inspections exert an indirect deterrent effect on non-targeted local governments. As Yeo (Reference Yeo2016, 67) argued, “the investigation reports from these central inspection groups enable the party leadership not only to pre-empt the appointment of senior cadres under suspicion, but also to alarm powerful local cadres.” Fourth, while business inspections primarily influence career advancement, political inspections fundamentally relate to political security and survival.

The comparative features of political inspections and business inspections can be summarized as in Table 1. Due to these characteristics, central government political inspections of provincial agencies can indirectly rectify certain inappropriate behaviors by municipal officials. A prime example involves the inadequate provision of “invisible public goods,” a concept defined by Mani and Mukand (Reference Mani and Mukand2007) as public goods whose provision quality cannot be reliably evaluated through observable outcomes. Such goods include drainage systems, sewer density in urban areas, and similar infrastructure. This definition reveals two core attributes of invisible public goods. First, their evaluation is inherently conditional: public judgment of quality depends on specific triggering circumstances. Sewer adequacy, for instance, only becomes demonstrable during extreme rainfall, just as natural gas supply resilience is tested exclusively during sustained cold temperatures. Conversely, goods like streetlight coverage or park accessibility permit immediate visual assessment. The conditional nature of such goods creates a second attribute: temporal lag in public evaluation. If stable climatic conditions persist—failing to activate the necessary evaluation triggers—public scrutiny of sewer systems or gas supply adequacy may remain dormant for years, delaying accountability for undersupply.

Table 1. The comparison of political and business inspections

The above two characteristics of invisible public goods are closely related to politicians’ strategic resource allocation. This relationship can be elucidated through the lens of policy salience. Specifically, because the public, media, and policy advocates can only frame inadequate supply of invisible public goods as a policy “problem” under specific timing and conditions, the salience of addressing such deficiencies exhibits inherent contingency and uncertainty. Policy salience is an important concept in much political science research (see the overview in Behr and Iyengar, Reference Behr and Iyengar1985). The term originally denotes the perceived importance of policy issues (e.g., Berelson et al., Reference Berelson, Lazarsfeld and McPhee1954). Consequently, higher public salience typically increases politicians’ responsiveness. However, traditional salience measurements cannot effectively distinguish between invisible and visible public goods when evaluating pure importance. No citizen would objectively consider drainage systems less essential than urban green spaces. Regarding conceptual limitations in salience applications, Wlezien (Reference Wlezien2005) critiqued how conventional approaches conflate an issue’s intrinsic importance with its recognition as an immediate problem. He asserted: “We have reason to believe that the economy is always an important issue to voters, but that it is a problem only when unemployment and/or inflation are high” (Wlezien Reference Wlezien2005, 556). Salience is therefore equally determined by when and to what degree an issue manifests as a tangible problem. This reconceptualization, validated by subsequent scholarship (Bromley-Trujillo and Poe Reference Bromley-Trujillo and Poe2020), provides our analytical framework for differentiating invisible from visible public goods. Applying this perspective to invisible public goods’ conditional evaluation, their supply inadequacies become recognizable as policy problems only under particular circumstances. Thus, while invisible public goods may possess higher latent salience than other public goods, the actualization of this potential remains contingent.

When public salience regarding invisible public goods provision depends on unpredictable contingencies rather than sustained visibility, political actors have more incentives to prioritize funding and effort toward areas offering higher career returns. Mani and Mukand (Reference Mani and Mukand2007) demonstrate how this mechanism operates in electoral democracies: since voter decisions depend on governments’ observed performance metrics, politicians rationally prioritize visibly verifiable services over those resisting immediate assessment.

This crowding-out of invisible public goods in favor of visible ones is ubiquitous in China as well. Using a panel dataset including all Chinese prefecture-level cities from 2001 to 2010, Wu and Zhou (Reference Wu and Zhou2018) indicate that, in terms of urban maintenance construction expenditures, local governments show a clear tendency to prioritize the improvement of visible public goods, some of which are not directly beneficial to economic development, such as landscaping and sanitation. They attribute this “visibility bias” to the Chinese centralized personnel system, under which subjective performance evaluations aided by superiors’ field visits and interviews are as important as local GDP performance. The neglect of invisible public goods provision further manifests procedurally through perfunctory review mechanisms. Municipal Housing and Urban-Rural Development Bureaus routinely convene planning meetings designed to evaluate all urban infrastructure projects—from public facilities and housing to green spaces and signage. Yet in practice, crucial investments in invisible public goods like drainage systems and underground utilities face systematic marginalization. As Wu and Zhou (Reference Wu and Zhou2018) document, such projects either bypass agenda inclusion entirely or receive rushed approval without substantive debate. This procedural short-circuiting stems directly from leadership incentives: since these low-visibility initiatives offer negligible political returns during promotion competitions, officials rationally deprioritize rigorous scrutiny despite their critical long-term significance.

In summary, robust central political inspections generate a dual governance effect: they directly purge non-compliant provincial officials while indirectly compelling municipal leaders to proactively mitigate career risks. Facing this deterrent, city-level cadres engage in strategic self-rectification rather than passive inaction, implementing corrective measures in domains vulnerable to accountability exposure. Improving municipal provision of invisible public goods represents a logical priority within this risk-reduction calculus, transforming neglected infrastructure into a targeted area for preemptive governance adjustments. However, some may question that given the conditional evaluation and temporal accountability lag inherent to invisible public goods, why would officials choose to improve rather than conceal deficiencies or maintain the status quo? This paradox is resolved through two key factors. First, whereas the triggering conditions for assessing invisible public goods (e.g., extreme weather events) are stochastic, central political inspections operate through institutionalized cycles. Second, as previously established, the inspection process independently gathers evidence via auditing and social mobilization mechanisms, thereby breaking local information monopolies. Consequently, the institutionalized nature and informational advantages of central political inspections transform concealment or nonfeasance, originally a strategy carrying only contingent risks, into a credible threat to officials’ political survival. This dynamic in a way mirrors the prisoner’s dilemma: when law enforcement possesses independent evidence, denial becomes the riskier strategy.

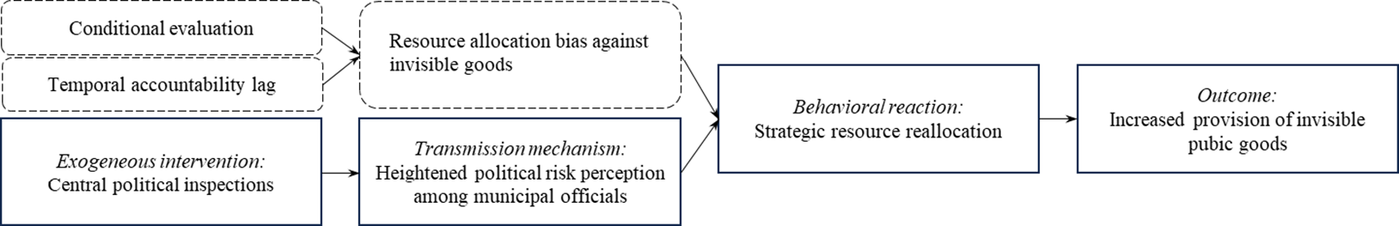

The causal logic and interrelationships among core theoretical constructs, as discussed above, are synthesized in Figure 1).

Figure 1. The causal logic and relationship among core theoretical constructs.

The causal pathway delineated above crystallizes into the following testable hypothesis:

Other things being equal, the central government’s political inspection of provincial governments will increase the provision of invisible public goods at the municipal level.

Data and methodology

Our main data include a yearly panel covering 289 cities in China during 2007–2017. The decentralized administrative system in China provides substantial variation across years and cities in terms of governance outcomes. To document the quantitative evidence, we combine four primary datasets: public goods provision from the China Urban Construction Statistical Yearbook (CUCSY), central inspection information from the State Supervision Commission, the personal characteristics of municipal leaders from their public CV, and city-level geographic and economic information from the China City Statistical Yearbook. Our dataset allows us to empirically examine the unintended fixing effects of central inspections on the invisible public goods supply.

Invisible public goods provision

Our empirical analysis relies on measures of a city’s invisible public goods provision as the main dependent variables. To construct these variables, we use data from the CUCSY in the period 2007–2017. Since the construction expenditures of these public goods are not available in the yearbook, we use the scale of public goods provision as a proxy for public goods supply intensity. The CUCSY is published by the Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development and contains a comprehensive list of the provision scales of public utilities at the city level. Following the discussion in Wu and Zhou (Reference Wu and Zhou2018), we mainly use the supply variables related to water supply, drainage, and gas supply as invisible public goods. These essential and underground infrastructure projects cannot be observed directly by the public, and are less transparent to superior officers during the government performance evaluation. Specifically, we use seven forms of public goods provision as the outcome variables: water coverage, public service water, drainage pipeline length, built district sewer density, gas supply pipeline length, gas coverage, and gas supply. The detailed definitions for the variables are provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Definitions of invisible public goods

Key variable of interest: Central inspection’s impact

This study focuses on political inspections of provincial governments that are initiated by the central government. We determine the distribution of the central inspection’s impact using the inspection information collected from the official website of the State Supervision Commission.Footnote 1 This website contains inspection area, arrival and departure dates of the inspection team, and feedback from each round of the central inspection. We mainly use the data for the first four rounds of central inspection since 2013, finalizing the first wave of full coverage for the governors at the provincial level. We identify the average impact of the first experience of a central inspection for the inspected provinces. According to the Regulations of the CPC in the Inspection of Work, the directors and composition of the inspection team, period for investigation, coverage area, and mission of the inspection are determined by the central state, and are only released to the public and bureaucrats a few days before each inspection round. These conditions guarantee that the timing of the central inspection is exogenous to the economic and governance performance at the city level. It is unlikely that the unobserved characteristics of an individual city could affect the periodic launch of central inspections.

Control variables

We control for confounding factors at the city level and characteristics of the municipal leaders to account for certain omitted variables. Our socioeconomic variables at the city level include population, the proportion of secondary industry, per capita GDP, and fiscal revenue (obtained from the CEIC China Premium Database), and built-up area (from the CUCSY). We also control for the personal characteristics of municipal leaders (i.e., the city CPC secretary and the city’s mayor) from their official resumes, including their age, gender, educational background, and details of tenure. For cities where more than one official served in each position (secretary or mayor) in the same year, the official with the longest tenure is considered the municipal leader for that year, following Yao and Zhang (Reference Yao and Muyang2013). The detailed description for the variables are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of key variables

Identification strategies

Our identification exploits variation in the timing of central inspections across provinces. Central inspection is a top-down campaign, and it is considered an exogenous shock to the cities in the inspected province. The first four rounds of central inspection covered all provinces and cities, and we cannot find a suitable control group for each inspected province. Following Sun et al. (Reference Sun, Fang, Yu and Wang2022), We analyze the effects of central inspection on municipal invisible public goods provision based on an analogous difference-in-difference (event-study) approach with a two-way fixed effects model. The specifications take the following form:

where the dependent variable yit is the invisible public goods provision for city i in year t, and InspectionIt is a dummy variable that equals 1 if province I for city i has been inspected in year t. China’s central inspection has a long and complicated political process for monitoring and involving the local government, which may not have immediate effects. To fully capture the effects of central inspection on the local government, InspectionIt equals 1 if the central inspection occurred in the first half of year t, and 0 otherwise. In the latter case, InspectionIt+1 will equal 1. This setting ensures that central inspections are given sufficient time to affect local public goods provision.

The coefficient of interest in Equation (1) is β1, which captures the impacts of central political inspections on invisible public goods provision. In line with our hypothesis, the coefficient is expected to be positive, suggesting that central inspection promotes invisible public goods provision. Xit is a vector of the control variables, including city leaders’ characteristics (e.g., age, tenure, square of tenure, gender, and native place) and city socioeconomic variables (e.g., resident population, the proportion of secondary industry, per capita GDP, fiscal revenue, and built-up area). The city fixed effects, φi, and year fixed effects, γt, are also included. The standard errors are clustered at the city level.

Baseline results

Table 4 reports the results of our baseline specification from Equation (1). In all columns, we control for city fixed effects, year fixed effects, personal characteristics of city leaders (CPC secretary and city mayor) and city socioeconomic variables. The estimated coefficients on central inspection are positive and significant for all types of invisible public goods, and their magnitudes are in the range from 0.010 to 0.216. This finding indicates that central political inspection promotes the provision of invisible public goods. We also report the Conley standard errors to deal with the potential spatial correlation between cities following Conley (Reference Conley1999) and Conley and Molinari (Reference Conley and Molinari2007), and our findings are still robust.Footnote 2 The cutoff window is set as 200 km and 5 years, account for the average distance between cities and the 5 years party political cycle.

Table 4. Central inspection and invisible public goods: Baseline

Note: The control variables are personal characteristics of the city leaders (CPC secretary and city mayor) and city socioeconomic variables. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the city level. Standard errors in brackets are Conley standard errors robust for spatial correlation, assuming a cutoff window of 200 km and a serial correlation of 5 years.

*p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01

Our baseline identification relies on the assumption that no other events occurred at the same time as the central inspection. We should not take this assumption for granted since China experienced rapid economic growth during our study period, and invisible public goods provision can be considered the consequence of economic development. To validate the key assumption that the trends are parallel for the inspected groups and uninspected groups before the central inspection, we test the pre-trend assumption. To simplify comparing the results, we combine the several invisible public goods into a single panel dataset. We employ a strategy similar to the event study that takes the following form:

$$ {y}_{igt}={\beta}_0+\sum \limits_{k=- 3+}^{k= 4}{\beta}_k\times {D}_{IK}+{\delta}^T\sum {X}_{it}+{\eta}_g+{\omega}_i+{\gamma}_t+{\varepsilon}_{igt} $$

$$ {y}_{igt}={\beta}_0+\sum \limits_{k=- 3+}^{k= 4}{\beta}_k\times {D}_{IK}+{\delta}^T\sum {X}_{it}+{\eta}_g+{\omega}_i+{\gamma}_t+{\varepsilon}_{igt} $$

where yigt is the outcome variable of invisible public good g for city i in year t. Here, DIk is a set of dummy variables equal to 1 if k years have passed since the first central inspection of province I, where −3+ ≤ k ≤ 4, and where -3+ refers to three years or more. One period before the central inspection is omitted as the comparison group. If the coefficients β-3+, β-3, and β-2 are not statistically different from 0, the parallel trends assumption is likely to hold. φi represents the city fixed effects, γt represents the year fixed effects, and ηg represents the public goods fixed effects.

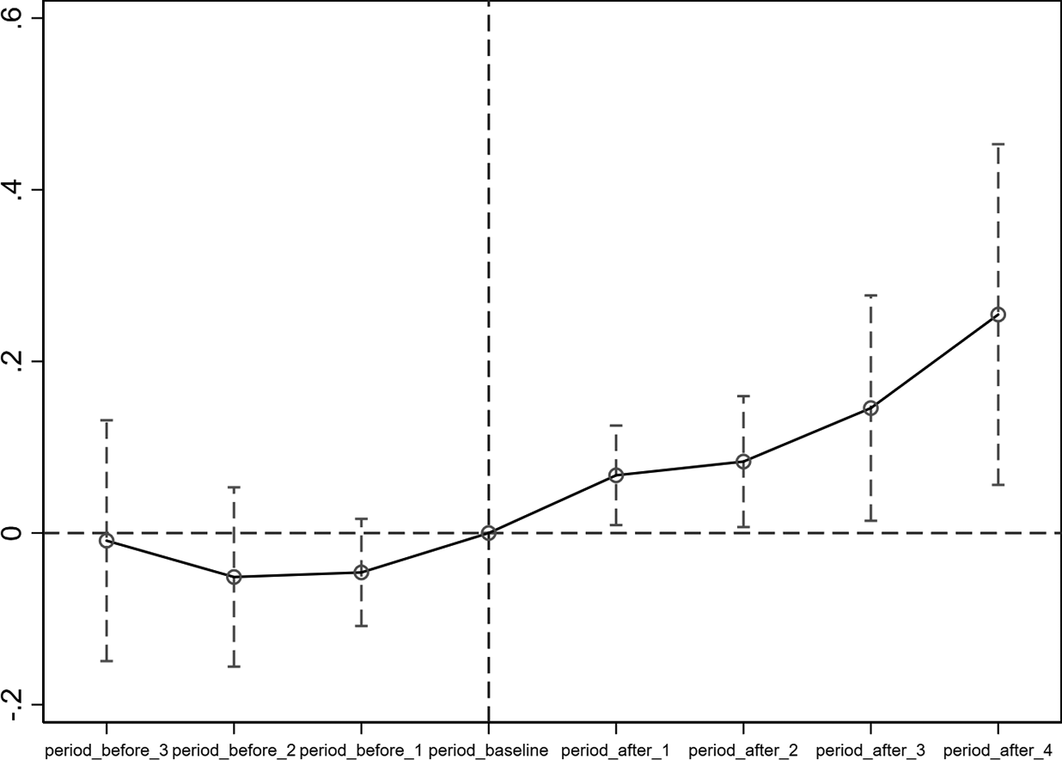

The results for Equation (2) and their 95 percent confidence intervals are presented in Figure 2. During the pre-inspection period, the difference between the inspected and uninspected groups is small, indicating that inspected cities and uninspected cities have similar trends in terms of invisible public goods provision. During the post-inspection period, the estimated coefficients are positive and significant, indicating that central inspection increases the supply scale of invisible public goods.

Figure 2. Dynamic estimation of the treatment effects.

We employ a placebo test to further confirm that our baseline identification captures the real effects from central inspection, rather than some other omitted confounding factors related to the inspection sequence, following Belloc et al. (Reference Belloc, Drago and Galbiati2016). Our sample covers the first round of full-coverage inspection, consisting of four waves of central inspection for 27 provinces. In the placebo test, we re-assign the sequence of inspection for all provinces in these four waves, and re-estimate our baseline regressions. To simply comparing the results, we combine the several invisible public goods into a single panel dataset with the following equation:

where all variables are defined as in Equation (2). The results are presented in Figure 3, which illustrates the probability density function of the 1,000 placebo point estimates, with a vertical line indicating our true point estimate. It is clear that the point estimates generated in the placebo test deviate around zero, and they are different from the true estimated coefficients from our baseline specification. This supports our previous findings.

Figure 3. Robustness check: Placebo test.

Endogeneity problem

One may consider possible reverse causation for our baseline results—that is, the scale of invisible public goods provision is not the consequence of central inspection, but the determinant of the order in the inspection sequence. In other words, the central inspection sequence is not implemented randomly; it reflects the central state’s consideration of many aspects, including political, economic, and environmental conditions. Although the multitude of factors determining this sequence is not transparent to the public, it is difficult to argue that inspection decisions only target invisible public goods provisions. With these conditions, central inspection can be considered a plausibly exogenous shock to invisible public goods provision at the city level.

To test the exogeneity of central inspection in invisible public goods provision, we regress provincial invisible public goods provision on the inspection sequence during the first round of the central inspection’s full coverage (i.e., 2013–2014).Footnote 3 The dependent variable is a dummy variable equal to 1 if province I was inspected in year t+1, and the independent variables are the main invisible public goods provision in province I in year t. Similar to our baseline specification, we also control for the personal characteristics of provincial leaders and provincial socioeconomic variables. The provincial and yearly fixed effects are included for each regression, and the results are reported in the following table. From Column 1 to Column 3, we add water coverage rate, gas coverage rate and density of sewers individually. None of the coefficients is significant, which is consistent with our expectation. In Column 4, we add all of these invisible public goods measures together, but their coefficients are still not significant. The results in the table suggest that the reverse causation is not the main concern of our empirical analysis. These findings confirm that our baseline results capture the impact of central inspection on invisible public goods provision.

Robustness checks

Alternative supervisions

Our first concern is to control for the alternative supervision and inspection based on our baseline specification. The results are reported in Table 5. First, we control for the second round of central inspection (i.e., follow-up re-inspection) at the provincial level. After 2015, while the first round of full coverage for central inspection was completed, the second round of central inspection was implemented as the “follow-up inspection” (“Huitoukan”). In Panel A of Table 5, the coefficients of inspection are all positive, and most are statistically significant, while the follow-up inspection, F_InspectionIt, is added. These findings imply that the increase in invisible public goods provision was mainly caused by the first-round inspection.

Table 5. Endogeneity: Invisible public goods and inspection sequence

Note: The control variables are personal characteristics of the province leader and province socioeconomic variables. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the province level. *p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01

Second, we control for provincial political supervision independence relative to the provision of public goods. Some literature argues that an official who establishes their career trajectory within a province can develop ties to subordinate officials and local elites (Huang, Reference Huang2002; Persson and Zhuravskaya, Reference Persson and Zhuravskaya2016; Tian and Fan, Reference Tian and Fan2016). Thus, a more independent provincial discipline inspection will improve local public goods provision. We add the variable IndependenceIt, which indicates whether or not the secretary of the committee for discipline inspection of province I in year t was rotated from outside (i.e., from a different province or the central government). We use this variable to exclude the effects of political connection among bureaucratic elites on the outcome variables, and our results in Panel B of Table 5 are robust.

Third, we add the variable, P_InspectionIt, indicating the provincial inspection for province I in year t, and our results in Panel C of Table 6 are consistent with our previous findings. The key takeaway from these results is that it is central political inspections rather than provincial inspections that have a stronger positive and significant influence on invisible public goods provision.

Table 6. Central inspection and invisible public goods: Alternative supervisions

Note: All regressions include controlled fixed effects and control variables. Fixed effects are year effects and city effects. The control variables are personal characteristics of the city leaders (CPC secretary and city mayor) and city socioeconomic variables. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the city level. Standard errors in brackets are Conley standard errors robust for spatial correlation, assuming a cutoff window of 200 km and a serial correlation of 5 years.

*p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01

Visible public goods

We also confirm that the impact of the central inspection is only significant for invisible public goods provision. According to our theoretical discussion, the shortage of invisible public goods provision is a more risky “short slab” than the visible goods provision, which attracts more attention from the local governors who want to safeguard their careers. Following this, the central inspection may not have an additional impact on visible public goods provision. We explore differences in the visibility of public goods to test our hypothesis indirectly. In Table 7, we use different types of visible public goods as the dependent variables, and we find that none of the coefficients is significant. These findings support our previous results.

Table 7. Central inspection and visible public goods

Note: The control variables are personal characteristics of city leaders (CPC secretary and city mayor) and city socioeconomic variables. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the city level. Standard errors in brackets are Conley standard errors robust for spatial correlation, assuming a cutoff window of 200 km and a serial correlation of 5 years.

*p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01

Political Ranking

Our first concern regards the omitted time-varying political ranking factors related to the public goods budget. Based on our baseline specification, we add the interaction terms between the time trend and the dummies capturing a city’s political ranking in Equation (1). The city dummies indicate whether or not: the city is a provincial capital; it is a sub-provincial city; it is located in eastern China; it is located in southern China; it is a municipality. Under China’s unified political system, each city’s administrative rank affects its scale of fiscal transfer from the central state, and higher-ranking cities receive more financial support from the central state for public goods provision (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Sun and Nie2018). These time-trend interactions allow us to control for the time-varying effects of municipal long-term budget support on the outcome variables. The results are reported in Panel A of Table 7. They show that all coefficients of the central inspection for different types of invisible public goods are positive and significant, which is consistent with our baseline results. To further alleviate the impact of sample selection bias, in Panel B of Table 8, we exclude the sub-provincial cities from our sample, and we still obtain the same robust results.

Table 8. Central inspection and invisible public goods: Political ranking

Note: The control variables are personal characteristics of the city leaders (CPC secretary and city mayor) and city socioeconomic variables. Fixed effects are year effects and city effects. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the city level. Standard errors in brackets are Conley standard errors robust for spatial correlation, assuming a cutoff window of 200 km and a serial correlation of 5 years.

*p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01

Anti-Corruption Effects

The promotion effect of inspection on invisible public goods may result from the deterrence effect of anti-corruption activities. During the central inspection period, there were great achievements in anti-corruption activities (Shi et al. Reference Shi, Shi-yi and Guo2017). According to the public information from the official website, the central inspection team has collected more than 58,000 clues about bureaucrat officials and inspected 1,225 officials at the prefectural level and 8,684 officials at the county level since the 18th National Congress of the CPC. If the provision of invisible public goods is motivated by exposure to anti-corruption activities, the positive effect of inspection obtained in the basic regression should be biased.

To deal with this possible omitted-variable bias, we control for anti-corruption intensity as a robustness check. We measure the intensity of anti-corruption efforts with two variables from the official information collected from the CDI (Commissions for Discipline Inspection) report. First, we use the number of officials above the bureau level in each city who were inspected between November 2012 and December 2015 (Corruption_bureaui). Second, we use the ratio of investigated officials above the county level to the total number of officials above the bureau level in each city between November 2012 and December 2015 (Corruption_ratioi). Because the public anti-corruption data are aggregated on a yearly basis and are only available during 2012–2015, the anti-corruption intensity variable is constructed as a cross-sectional variable. We interact the anti-corruption intensity measures with the time trend from 2007 in our panel data to control for the heterogeneous effects of anti-corruption efforts on the promotion of invisible public goods at the city level. The results are reported in Table 9, and all of the coefficients are positive and significant with alternative controls for the anti-corruption effects. These robust results confirm that the anti-corruption efforts are not the main explanation for the increased provision of invisible public goods that we observe.Footnote 4

Table 9. Anti-corruption achievements and inspection

Note: The control variables are personal characteristics of city leaders (CPC secretary and city mayor) and city socioeconomic variables. The time-trend interaction term is an interaction between the time trend and Corruption_bureau for Panel A and Corruption_ratio for panel B. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the city level. Standard errors in brackets are Conley standard errors robust for spatial correlation, assuming a cutoff window of 200 km and a serial correlation of 5 years.

*p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01

Leadership turnover

We also control for the cadre rotation of official regional leaders as a robustness check. An alternative explanation is that the change of public goods provision is the consequence of the newly nominated regional leader rather than the central inspection. It is possible that the newly appointed leader has stronger incentives to provide public goods at the beginning of their tenure. To exclude these factors, we add two dummy variables that represent whether or not the provincial leaders (provincial governor or secretary of provincial party committee) or city leaders (mayor or secretary of municipal party committee) had changed for province I or prefecture i in year t. The results, shown in Table 10, suggest that leadership turnover is not a key mechanism for invisible public goods provision. The estimated coefficients of the inspection term are similar to those of the baseline results.

Table 10. Central inspection and invisible public goods: Leadership turnover

Note: The control variables are personal characteristics of the city leaders (CPC secretary and city mayor) and city socioeconomic variables. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the city level. Standard errors in brackets are Conley standard errors robust for spatial correlation, assuming a cutoff window of 200 km and a serial correlation of 5 years.

*p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01

Political budget cycle

Another concern we investigate is the relationship between the city fiscal budget cycle and its public goods provision. Moving from the approval of public goods investments and budget appropriation to the final construction of infrastructure takes time. To account for this time lag, we modify our measure of central inspection and set C_InspectionI,t equal to 1 if the central inspection occurred during the first quarter of year t for province I. Otherwise, C_InspectionI,t+1 equals 1 if the central inspection occurred after March of year t for province I. This modification allows sufficient time for our specification to capture the effects of the change of official decisions on public goods provision under the pressure of central inspection. The results using C_InspectionI,t+1 are reported in Panel A of Table 10 and are consistent with our previous conclusions.

In addition, municipal governments have incentives to increase budget expenditures during the year the Provincial Congress of the CPC is held (Wu and Zhou, Reference Wu and Zhou2015). In democracies, during election years, government at all levels often diverts spending toward projects with high immediate visibility to show high competence and improve their chances of reelection (Rogoff, Reference Rogoff1990; Drazen, Reference Drazen2000). Similarly, Chinese officials face political budget cycles. The promotion incentives drive prefectural officials to accelerate expenditures on public goods during the Provincial Congress of the CPC (Gong et al., Reference Gong, Xiao and Zhang2017; Tsai, Reference Tsai2016). To deal with this time-varying factor, we add a dummy variable, P_CycleIt, to indicate the year of the CPC Provincial Congress for province I, which controls for the local political budget cycle. As reported in Panel B of Table 11, all the coefficients remain positive and significant, which is consistent with our findingsFootnote 5.

Table 11. Central inspection and invisible public goods: Political budget cycle

Note: The control variables are personal characteristics of the city leaders (CPC secretary and city mayor) and city socioeconomic variables. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the city level. Standard errors in brackets are Conley standard errors robust for spatial correlation, assuming a cutoff window of 200 km and a serial correlation of 5 years.

*p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01

Long-term effects and mechanism

We investigate whether the positive effects of inspections could be long-lasting. We address this concern by replacing the inspection variable with a set of dummy variables that represent the years after the inspection in Equation (2). To control for the potential unit-specific linear and quadratic time trends, we also add trend terms that city fixed effect interact with linear and quadratic year trends. In Table12, we present dynamic estimates for the provision of invisible public goods. Column (1) presents the results for the baseline model of Equation (2). The current-year term and subsequent-year terms are all positive and significant, and the coefficients on the subsequent-year terms increase over time. Indeed, this pattern implies that inspection has a long-term cumulative effect on invisible public goods provision that increases over time. In Columns 2–6, based on the specification in Column 1, we further control for the cities’ political rankings, independence of provincial monitoring, provincial inspections, follow-up re-inspections, and the CPC Provincial Congress. All results support the idea that the central inspection has a long-term impact on invisible public goods provision.

Table 12. Central inspection and invisible public goods: Long-term effects

Note: The control variables are personal characteristics of city leaders (CPC secretary and city mayor) and city socioeconomic variables. Standard errors in parentheses are Conley standard errors, assuming a cutoff window of 200 km and a serial correlation of 5 years.

*p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01

As described in our theoretical discussion, the main channel behind invisible public goods provision is the deterrent effects from the central political inspection, which forces local officials to address the shortage of public goods. However, these deterrent effects are difficult to measure because they are the subjective psychological response to the political inspection. As a compromise, we examine the mechanism by identifying officials’ direct behavior changes as a result of the deterrent effects. We then test whether invisible public goods provision increases as a result of improving financial transparency. The potential channel is that the high pressure created by the central political inspection may increase the incentives of local leaders to improve the transparency of public goods governance. It is expected that the municipal government will offer more information about the city budget to satisfy the public’s right to know, and to decrease citizens’ complaints. In China, although transparency may not improve accountability directly since electoral incentives are negligible, local officials still fear negative publicity because it can lead to punishment by higher-level authorities (Distelhorst, Reference Distelhorst2012; Lorentzen et al., Reference Lorentzen, Landry and Yasuda2014). Because the increasing financial transparency exerts pressure on misbehaving local officials, invisible public goods become visible to the public. Thus, the incentives for local municipal leaders to provide invisible public goods will increase in the long term.

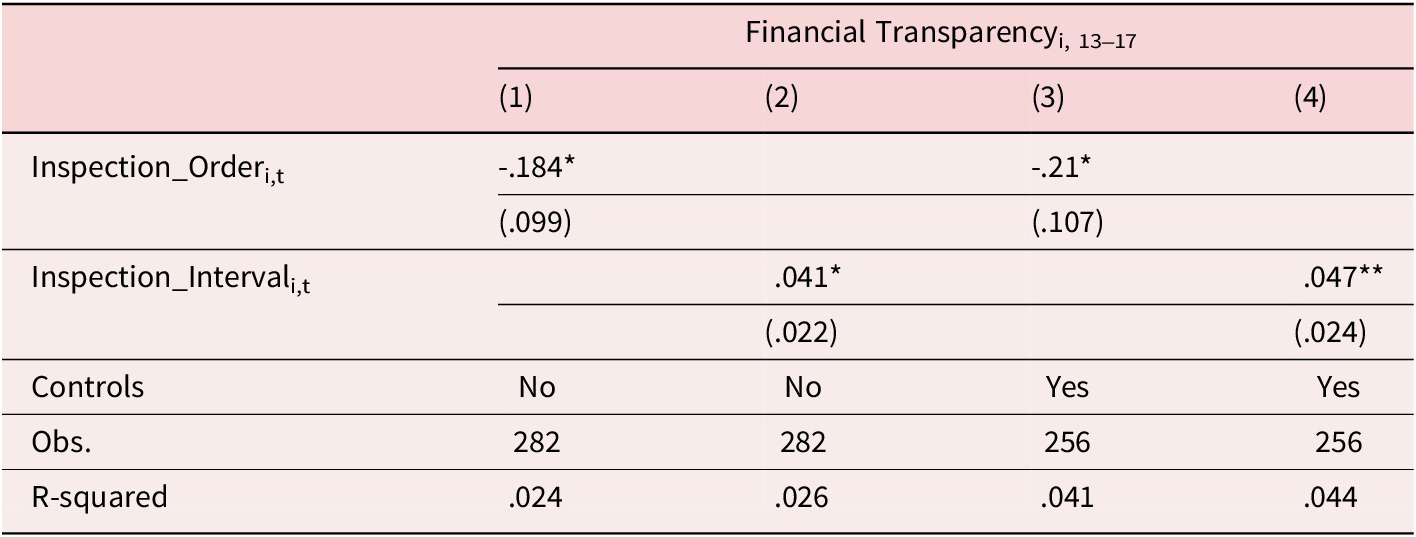

Empirically, we use the growth rates of the transparency score at the city level, which are extracted from the Research Report on Financial Transparency of Municipal Governments in China. Footnote 6 This serves as a proxy for municipal financial transparency growth from 2013 to 2017. The financial transparency score is an index that measures budget transparency in municipal administration institutions (e.g., government, the municipal People’s Congress, and the municipal party commission). To match the data on financial transparency, we use two new variables to capture the political inspection’s influence. First, we construct Inspection_Orderi,t as the inspection sequence order, which is a discrete variable coded from 1 to 4. The higher the number, the later the province was inspected. Second, we construct Inspection_Intervali,t as the number of months between the date of the province’s inspection and December 2017. The earlier a province was inspected, the longer and stronger the city in this province will be influenced by the central inspection. Table 13 reports the cross-sectional results of the effects of the inspection on financial transparency growth. The estimated coefficients on the inspection-order term are negative and significant, and the estimated coefficients on the inspection-interval term are positive and significant. Consistent with our expectation, this pattern suggests that the central political inspection indeed increased financial transparency at the city level.

Table 13. Financial transparency

Note: The control variables are city socioeconomic variables. Robust standard errors are in parentheses, clustered at the city level.

*p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01

Conclusion

The impact of top-down inspections on governance performance constitutes a central debate in political economy literature. Scholars have generated insightful empirical analyses across diverse national contexts and governance domains. Notably, extant research predominantly focuses on business inspections, a common variant of oversight mechanisms. Diverging from this emphasis, our study examines China’s central political inspections and their indirect effects on municipal governance. We demonstrate that since the 18th CPC National Congress, the Communist Party of China has revitalized this system, endowing it with institutional functions. By prioritizing political loyalty and integrity, with consequences directly tied to officials’ political survival, these inspections generate robust deterrence effects among municipal leaders. This dynamic activates strategic self-correction behaviors. In public governance, invisible public goods exhibit characteristics of conditional evaluation and temporal lag in assessment. These attributes frequently lead local governments to allocate insufficient attention to their provision. To mitigate perceived political risks amplified by inspections, municipal governments are incentivized to reallocate resources strategically, thereby enhancing the supply of invisible public goods.

The above findings, drawn from the Chinese context, highlight a key scope condition for the theory’s applicability: the central role of the political party in the selection, appointment, and promotion of cadres at both central and local levels. From this perspective, North Korea emerges as a potentially applicable case among East Asian countries, given its shared socialist framework and the existence of internal party supervision mechanisms. However, a critical distinction lies in the absence of a standardized and institutionalized political inspection system within the Workers’ Party of Korea (Li, Reference Li2021). In contrast, Japan and South Korea fall outside the theory’s scope. As local chief executives there are elected by popular vote and are directly accountable to their constituents, the central government—even when controlled by the ruling party—cannot effectively intervene in local affairs through intra-party supervision (Anderson, Reference Anderson and Farazmand2019; Noda, Reference Noda and Noda2024). This brief comparative analysis of East Asia reveals that the specific form and function of an inspection system are endogenous to a country’s broader political system, resulting in a diverse pattern of institutional arrangements.

Further, this study identifies a material mechanism—improving the provision of invisible public goods—that complements the moral mechanism proposed by Wang (Reference Wang2025), which centers on enhancing legitimacy through ethical concerns about corruption. Together, both Wang (Reference Wang2025) and this article concern how inspections reshape the public evaluations of governance. Although this study demonstrates that central political inspections can improve local provision of invisible public goods, their broader impact on overall governance performance requires more cautious examination. Some literatures suggest that top-down accountability may impede bureaucratic efforts to advance public interest in certain circumstances (Chen, Keng, and Zhang, Reference Chen, Keng and Zhang2023; Zhong and Zeng, Reference Zhong and Zeng2024; Tu and Gong, Reference Tu and Gong2022). Wang (Reference Wang2022) makes a more pessimistic argument that Chinese political inspections produce somewhat adverse effects on local economic developments. Due to the “chilling effect” of political inspections, bureaucrats are afraid to do their daily jobs using informal practices, many of which may be well intended to support organizational goals. As a result, political inspections significantly lower the area of land development projects proposed by bureaucrats. Juxtaposing Wang’s findings with our analysis reveals that this distinctive top-down monitoring instrument introduced by the CPC generates highly heterogeneous effects on official behavior and governance outcomes. Specifically, it appears more effective at stimulating corrective behaviors in officials (e.g., improving invisible goods provision) while concurrently suppressing developmental initiatives (e.g., expanding land development projects).

Finally, it is essential to acknowledge notable limitations of this study. Empirically, our analysis relies primarily on data from the inaugural wave of nationwide central inspections (2013–2017). As detailed in the methodology section, this temporal scope ensures exogeneity between inspection timing and city-level governance/economic performance. However, this data limitation fundamentally restricts our examination to the initial deployment phase of this oversight instrument, precluding analysis of its long-term institutionalization effects. Specifically, our design cannot ascertain whether localities develop adaptive counterstrategies as political inspections become institutionalized practices. Should such adaptations emerge, how might they reconfigure the efficacy of subsequent inspection cycles? While emerging scholarship engages these questions, substantial theoretical and empirical disagreements persist. Future research examining this evolutionary dynamic between inspection regimes and their adaptive responses, promises dual contributions: advancing understanding of China’s complex monitoring regime, while generating insights applicable to broader questions such as central–local bargaining, bureaucratic adaptation mechanisms, and institutional resilience.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2025.10026.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Jianan Li is an Associate Professor in Economics at the School of Economics, and Wang Yanan Institute for Studies in Economics at Xiamen University. His research interests include economic history and development economics.

Wenxun Chen is a Ph.D. candidate in Economics at the Wang Yanan Institute for Studies in Economics, Xiamen University. His research interests include economic history, cultural economics, and development economics.

Chao Chen (Corresponding author) is an Associate Professor at School of International and Public Affairs at Shanghai Jiao Tong University. He is also a Research Fellow at Institute of Politics and Economics and Shanghai Research Center for Innovation and Policy Evaluation at Shanghai Jiao Tong University. His research interests center around political economy and Chinese politics.