1. Introduction

In recent decades, wind turbines have grown significantly in size. This trend is expected to continue, especially in the offshore sector, as the wind energy industry seeks to improve the economics of wind turbines (Enevoldsen & Xydis Reference Enevoldsen and Xydis2019; Bilgili & Alphan Reference Bilgili and Alphan2022). However, the increasing size and hub height of wind turbines introduce new research challenges, particularly in understanding and modelling atmospheric turbulence at rotor-relevant altitudes (Veers et al. Reference Veers2023). For example, the widely used Mann (Reference Mann1994) and Kaimal (Kaimal et al. Reference Kaimal, Wyngaard, Izumi and Coté1972) models, recommended by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) for wind turbine design and certification (IEC 2019), were originally developed for turbulence within the atmospheric surface layer. Their validity at the heights of multi-megawatt turbines remains uncertain, partly due to the scarcity of experimental data on turbulence above 100 m in the marine atmospheric boundary layer (MBL) (van Kuik et al. Reference van Kuik2016; Veers et al. Reference Veers2023).

This study aims to present measurements of one-point auto-spectra and two-point spectral coherence of turbulence at heights from 150 to 250 m above sea level, which are then compared with the predictions of the Mann model and its extension, the Syed–Mann model (Syed & Mann Reference Syed and Mann2024). We also attempt to answer the following question: What physical mechanism causes the measurements to deviate from the theoretical foundations of the aforementioned models?

Measurements of atmospheric turbulence over water began with the use of anemometers placed 10–15 m above the surface (Weiler & Burling Reference Weiler and Burling1967; Miyake, Stewart & Burling Reference Miyake, Stewart and Burling1970) and air plane flights (Lenschow & Agee Reference Lenschow and Agee1976; Nicholls & Readings Reference Nicholls and Readings1981; Gage & Nastrom Reference Gage and Nastrom1986) that covered higher altitudes but only provided pointwise measurements over limited durations. Data on the spatio-temporal structure of turbulence in the MBL became more widely available in the 1990s as met-masts were deployed near the coast and offshore (Mann, Kristensen & Courtney Reference Mann, Kristensen and Courtney1991; Gjerstad et al. Reference Gjerstad, Aasen, Andersson, Brevik and Løvseth1995; Vincent et al. Reference Vincent, Larsén, Larsen and Sørensen2013; Larsén et al. Reference Larsén, Vincent and Larsen2013; Holtslag et al. Reference Holtslag, Beirbooms and van Bussel2015; Cheynet, Jakobsen & Reuder Reference Cheynet, Jakobsen and Reuder2018). One of the first campaigns to measure two-point cross-spectra in the marine boundary layer was done by Mann et al. (Reference Mann, Kristensen and Courtney1991) that used two meteorological masts placed on the island of Sprogø in the Great Belt. This dataset was used in the validation of the Mann model. Gjerstad et al. (Reference Gjerstad, Aasen, Andersson, Brevik and Løvseth1995) used measurements spanning many hours from an islet in the Norwegian Sea and observed the spectral gap (van der Hoven Reference van der Hoven1957) in agreement with the seminal Kansas experiment (Kaimal et al. Reference Kaimal, Wyngaard, Izumi and Coté1972). Vincent et al. (Reference Vincent, Larsén, Larsen and Sørensen2013) and Larsén et al. (Reference Larsén, Vincent and Larsen2013) analysed spectra, cross-spectra and coherence at low frequencies down to 10

![]() $^{-6}$

Hz and at separations of more than one kilometre from two wind farms in the North and Baltic Seas. They found that mesoscale turbulence under stationary conditions was two-dimensional (two components of space and two components of velocity, 2D2C) and isotropic such that both components had the same variance. Larsén et al. (Reference Larsén, Larsen and Petersen2016) subsequently derived an empirical expression for the auto-spectra over mesoscales and synoptic scales in the frequency domain, akin to the relation first presented by Lindborg (Reference Lindborg1999) in the wavenumber domain. In another study (Larsén et al. Reference Larsén, Larsen, Petersen and Mikkelsen2021), a similar expression was derived for the cross-wind fluctuations. Cheynet et al. (Reference Cheynet, Jakobsen and Reuder2018) also computed the spectra and vertical coherence over different stability regimes at heights up to 81 m above the German North Sea. They found that the Kaimal model agreed with the observed spectra, except under very stable conditions when there was a spectral gap present. Vertical coherence was also adequately described by the Davenport model (Davenport Reference Davenport1961).

$^{-6}$

Hz and at separations of more than one kilometre from two wind farms in the North and Baltic Seas. They found that mesoscale turbulence under stationary conditions was two-dimensional (two components of space and two components of velocity, 2D2C) and isotropic such that both components had the same variance. Larsén et al. (Reference Larsén, Larsen and Petersen2016) subsequently derived an empirical expression for the auto-spectra over mesoscales and synoptic scales in the frequency domain, akin to the relation first presented by Lindborg (Reference Lindborg1999) in the wavenumber domain. In another study (Larsén et al. Reference Larsén, Larsen, Petersen and Mikkelsen2021), a similar expression was derived for the cross-wind fluctuations. Cheynet et al. (Reference Cheynet, Jakobsen and Reuder2018) also computed the spectra and vertical coherence over different stability regimes at heights up to 81 m above the German North Sea. They found that the Kaimal model agreed with the observed spectra, except under very stable conditions when there was a spectral gap present. Vertical coherence was also adequately described by the Davenport model (Davenport Reference Davenport1961).

The construction costs of offshore met-masts are high and they tend to rise sharply with the height of the mast. Consequently, offshore masts taller than 100 m are rare. This has led to remote sensing techniques such as light detection and ranging (lidar) (Sathe & Mann Reference Sathe and Mann2013) becoming increasingly common in measuring turbulence at higher altitudes in the MBL (Cheynet et al. Reference Cheynet, Jakobsen, Snæbjörnsson, Mikkelsen, Sjöholm, Mann, Hansen, Angelou and Svardal2016, Reference Cheynet2021; Angelou et al. Reference Angelou, Mann and Dubreuil-Boisclair2023; Syed & Mann Reference Syed2024). For instance, short-range dual lidars were deployed by Cheynet et al. (Reference Cheynet, Jakobsen, Snæbjörnsson, Mikkelsen, Sjöholm, Mann, Hansen, Angelou and Svardal2016) on a bridge in Norway at a height of 55 m to measure lateral coherence, demonstrating that spatial averaging effects of lidars were negligible for coherence measurements. Building on this, Cheynet et al. (Reference Cheynet2021) used long-range scanning lidars to record spectra and lateral coherence up to 130 m above the Norwegian Sea. However, high uncertainty in beam pointing directions limited the accuracy of their results. More recently, Angelou et al. (Reference Angelou, Mann and Dubreuil-Boisclair2023) and Syed & Mann (Reference Syed2024) used forward-looking nacelle lidars to measure lateral coherence at separations up to 100 m. These studies also observed mesoscale turbulence with the characteristic

![]() $-5/3$

slope (Lindborg Reference Lindborg1999; Larsén et al. Reference Larsén, Larsen and Petersen2016) at wavenumbers below 10

$-5/3$

slope (Lindborg Reference Lindborg1999; Larsén et al. Reference Larsén, Larsen and Petersen2016) at wavenumbers below 10

![]() $^{-3}$

m

$^{-3}$

m

![]() $^{-1}$

. However, the measurements were limited to line-of-sight components. Thus, the lateral coherence of the true wind components has not been measured before at separations between 100 to 250 m, at heights above100 m and for frequencies down to the mesoscale range. Consequently, the validity of turbulence models like the Mann model, at these heights and separations, has remained an open question.

$^{-1}$

. However, the measurements were limited to line-of-sight components. Thus, the lateral coherence of the true wind components has not been measured before at separations between 100 to 250 m, at heights above100 m and for frequencies down to the mesoscale range. Consequently, the validity of turbulence models like the Mann model, at these heights and separations, has remained an open question.

In this study we present novel observations of spectra and lateral coherence at heights between 150 and 250 m above the Danish North Sea, with lateral separations of up to 241 m. Our set-up consists of five lidars deployed along the west coast of Denmark, with beam pointing directions calibrated using drones to achieve high accuracy (Thorsen, Simon & Clausen Reference Thorsen, Simon and Clausen2023). This set-up enables direct measurement of the true along-wind and cross-wind components of turbulence. The observations are also compared with the Mann model and its extension, which includes mesoscale turbulence (Syed & Mann Reference Syed and Mann2024). The Syed–Mann model can capture most features of atmospheric turbulence at these heights, albeit with exceptions.

The paper is organised as follows: § 2 describes the site, instrumentation, data processing methods and estimation of atmospheric stability using Weather Research and Forecast (WRF) simulations and boundary layer height detection. Section 3 presents a comparison between our measurements and the turbulence models, with a detailed analysis of cases where discrepancies occur. Finally, key conclusions are summarised in § 4.

2. Experimental dataset

2.1. Description of the field campaign

The experimental site was located near Trans, a small town in the Jutland peninsula on the west coast of Denmark. The site provided unobstructed access to the North Sea while being near the Test Centre Høvsøre where full-scale wind turbine prototypes are routinely tested. Consequently, technicians from the test facility could regularly carry out maintenance on the equipment. Moreover, this region and its climate are of high relevance to wind energy as many offshore wind farms are in operation, under construction or being planned in the North Sea.

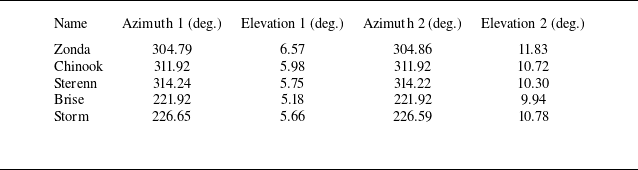

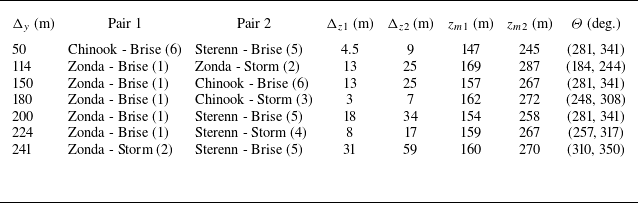

We used five long-range pulsed coherent Doppler lidars in the experiment as described in table 1. The campaign lasted for five months, from late January to late June 2024. Thus, the campaign covered a period from late winter to early summer. The change in seasons had a direct effect on the observed atmospheric stability, which is discussed in § 2.3. The set-up of the experiment is shown in figure 1. Two lidars were present at the northern site close to the lighthouse of Bovbjerg while the remaining three lidars were next to the church of Trans in the south. Pictures from these sites are shown in figure 2. The lidar beams had a low elevation angle and intersected approximately 1.5 km from the coast. The plane of intersection lay approximately 150 m above the sea surface from the start of the campaign to the end of April. Subsequently, the elevation angles were increased to move the plane of intersection to nearly 250 m above the sea surface. The azimuth and elevation of the beams during the two periods are described in table 2. Figure 3 provides a closer look at the plane of intersection and the six crossing points. This set-up bears some similarity to the RUNE experiment (Floors et al. Reference Floors, Peña, Lea, Vasiljević, Simon and Courtney2016) that was carried out at the same location, although with only one pair of dual lidars.

Table 1. Details of the instruments used in the measurement campaign. From left to right the columns are: name of the lidar, manufacturer and model, closest landmark, positions in UTM zone 32V and the elevation above the sea surface of the ground where the lidars are located.

Figure 1. Three-dimensional (3D) view of the experiment indicating the two sites, church and lighthouse, where the black lines indicate the lidar beams in configuration 1 and the red dots show the intersection points. The colours indicate the elevation of the surrounding terrain. The easting and northing axes are defined with the origin at 441 000 m and 6 260 000 m, respectively. Thus, the church is present close to easting 446 000 m and northing 6 262 000 m as indicated in table 1. The arrow with the label ‘N’ denotes the direction of true north that corresponds to 0

![]() $^{\circ }$

azimuth. An interactive version of this plot, the associated data and Jupyter notebook can be found (https://www.cambridge.org/S0022112025111038/JFM-Notebooks/files/Figure_1/Make_figure_1.ipynb).

$^{\circ }$

azimuth. An interactive version of this plot, the associated data and Jupyter notebook can be found (https://www.cambridge.org/S0022112025111038/JFM-Notebooks/files/Figure_1/Make_figure_1.ipynb).

Table 2. Set-up of the lidars in terms of azimuth and elevation of the beams in configurations 1 and 2. The azimuth is defined such that 0

![]() $^\circ$

is north while the elevation is 0

$^\circ$

is north while the elevation is 0

![]() $^\circ$

for a beam oriented parallel to the sea surface.

$^\circ$

for a beam oriented parallel to the sea surface.

Figure 2. Pictures from the church (a) and lighthouse (b) site showing the instruments used in the experiment. Information about the instruments can be found in table 1.

Extensive verifications of the correct pointing positions of the lidars were performed before, during and after the campaign. The primary method of calibration was hard targeting a drone with real time kinematic (RTK) positioning (Thorsen et al. Reference Thorsen, Simon and Clausen2023). We also relied on sea surface levelling and traditional hard target mapping. A detailed description of the campaign can be found in Mann et al. (Reference Mann, Sjöholm, Patel, Thorsen, Simon, Hung and Gottschall2025). Note that the drone-based calibration resulted in an uncertainty of 1 mrad in the azimuth and elevation angles of the lidar beams. This corresponds to an uncertainty of 1 m in the altitudes and separations shown in table 3, which is negligible compared with the separation distances analysed in this study.

2.2. Preparation of lidar data

This section describes the removal of data with excessive noise and the post-processing applied on the leftover data to prepare it for the analysis shown in § 3.

Table 3. The available lateral separations for coherence measurements along with the height above sea level and direction bins. The columns from left to right are: lateral separation (

![]() $\Delta _y$

), lidar pairs at the two ends, vertical separation in configuration 1 and 2 (

$\Delta _y$

), lidar pairs at the two ends, vertical separation in configuration 1 and 2 (

![]() $\Delta _z$

), average measurement height in configuration 1 and 2 (

$\Delta _z$

), average measurement height in configuration 1 and 2 (

![]() $z_m$

) and the wind direction bins (

$z_m$

) and the wind direction bins (

![]() $\varTheta$

). The numbers in the braces in columns 2 and 3 refer to the intersection points from figure 3. Note that the heights shown here are the mean of the heights of the two crossing points. As the plane of intersection is not horizontal, the crossing points do not lie on the same height.

$\varTheta$

). The numbers in the braces in columns 2 and 3 refer to the intersection points from figure 3. Note that the heights shown here are the mean of the heights of the two crossing points. As the plane of intersection is not horizontal, the crossing points do not lie on the same height.

Figure 3. Top view of the intersection plane of the lidar beams where the numbers denote the crossing points and the beams from the lidars are denoted according to table 1. The arrow with the label ‘N’ indicates the direction of true north.

Doppler lidars measure the component of the velocity field projected along the lidar beam, which is henceforth referred to as the radial velocity,

![]() $v_r$

. Since the radial velocity is sampled at a frequency of 1 Hz, it may contain spikes or noise due to low concentrations of aerosols in the atmosphere, dirt and water on the lens, the presence of obstacles in the lidar beam, etc. (Vasiljević et al. Reference Vasiljević, Lea, Courtney, Cariou, Mann and Mikkelsen2016). The 1 Hz data are first segregated into periods of 10 minutes duration and entire 10 min periods are rejected wherein the noise is above a certain threshold. In the literature, noise is often characterised by the carrier-to-noise ratio (CNR) and a threshold that is constant in time is applied to differentiate between reliable and unreliable data. Although this method is simple to implement, it suffers from the drawback that the optimal CNR threshold varies significantly with the site conditions, instrument manufacturer and experimental set-up (Gryning et al. Reference Gryning, Floors, Peña, Batchvarova and Brümmer2016). Thus, in this study, noise was characterised by another metric:

$v_r$

. Since the radial velocity is sampled at a frequency of 1 Hz, it may contain spikes or noise due to low concentrations of aerosols in the atmosphere, dirt and water on the lens, the presence of obstacles in the lidar beam, etc. (Vasiljević et al. Reference Vasiljević, Lea, Courtney, Cariou, Mann and Mikkelsen2016). The 1 Hz data are first segregated into periods of 10 minutes duration and entire 10 min periods are rejected wherein the noise is above a certain threshold. In the literature, noise is often characterised by the carrier-to-noise ratio (CNR) and a threshold that is constant in time is applied to differentiate between reliable and unreliable data. Although this method is simple to implement, it suffers from the drawback that the optimal CNR threshold varies significantly with the site conditions, instrument manufacturer and experimental set-up (Gryning et al. Reference Gryning, Floors, Peña, Batchvarova and Brümmer2016). Thus, in this study, noise was characterised by another metric:

![]() $\sigma _{v_r}$

, which is the standard deviation of

$\sigma _{v_r}$

, which is the standard deviation of

![]() $v_r$

over an interval of 10 minutes. The optimal threshold for

$v_r$

over an interval of 10 minutes. The optimal threshold for

![]() $\sigma _{v_r}$

was independent of the aforementioned factors.

$\sigma _{v_r}$

was independent of the aforementioned factors.

When

![]() $\sigma _{v_r}$

was greater than 4 ms

$\sigma _{v_r}$

was greater than 4 ms

![]() $^{-1}$

, the 10 min period contained at least 60 spikes in the 1 Hz data (which corresponds to 10 % of the data). This relation was determined empirically by analysing a large portion of the raw dataset. Consequently, the corresponding 10 min periods were removed from the dataset. On the other hand, when

$^{-1}$

, the 10 min period contained at least 60 spikes in the 1 Hz data (which corresponds to 10 % of the data). This relation was determined empirically by analysing a large portion of the raw dataset. Consequently, the corresponding 10 min periods were removed from the dataset. On the other hand, when

![]() $\sigma _{v_r}$

was less than 1.2 ms

$\sigma _{v_r}$

was less than 1.2 ms

![]() $^{-1}$

, the 10 min period was free from spikes and was retained for further post-processing. When

$^{-1}$

, the 10 min period was free from spikes and was retained for further post-processing. When

![]() $1.2 \leqslant \sigma _{v_r} \leqslant 4$

, the method developed by Beck & Kühn (Reference Beck and Kühn2017) was used to remove spikes. It is based on 2D Gaussian kernel density estimation (KDE) using

$1.2 \leqslant \sigma _{v_r} \leqslant 4$

, the method developed by Beck & Kühn (Reference Beck and Kühn2017) was used to remove spikes. It is based on 2D Gaussian kernel density estimation (KDE) using

![]() $v_r$

and CNR and relies on the assumption that good data are self-similar. As a result, they must be present in ‘data-dense’ regions in the abstract space defined by

$v_r$

and CNR and relies on the assumption that good data are self-similar. As a result, they must be present in ‘data-dense’ regions in the abstract space defined by

![]() $v_r$

and CNR. Beck & Kühn (Reference Beck and Kühn2017) found that the method minimises the mean error between lidar and sonic anemometer measurements as compared with many other commonly used spike-removal algorithms. The method was modified such that it estimated the kernel density of radial velocity differences (

$v_r$

and CNR. Beck & Kühn (Reference Beck and Kühn2017) found that the method minimises the mean error between lidar and sonic anemometer measurements as compared with many other commonly used spike-removal algorithms. The method was modified such that it estimated the kernel density of radial velocity differences (

![]() $\Delta v_r$

instead of

$\Delta v_r$

instead of

![]() $v_r$

) and the CNR as this reduced the amount of data incorrectly identified as noise. After applying the modified KDE algorithm, if less than 10 % of the data was lost in a given 10 min period or the spike removal left gaps less than 5 s in duration, then the gaps were filled by linear interpolation. Otherwise, the corresponding 10 min period was removed as well. Note that the spike-removal algorithm did not remove all the spikes in the dataset. The leftover noise is dealt with separately as described in the next section.

$v_r$

) and the CNR as this reduced the amount of data incorrectly identified as noise. After applying the modified KDE algorithm, if less than 10 % of the data was lost in a given 10 min period or the spike removal left gaps less than 5 s in duration, then the gaps were filled by linear interpolation. Otherwise, the corresponding 10 min period was removed as well. Note that the spike-removal algorithm did not remove all the spikes in the dataset. The leftover noise is dealt with separately as described in the next section.

Next, the east–west (

![]() $v_{\textit{EW}}$

) and north–south (

$v_{\textit{EW}}$

) and north–south (

![]() $v_{\textit{NS}}$

) wind components were reconstructed at the six crossing points using the following relations (Peña & Mann Reference Peña and Mann2019):

$v_{\textit{NS}}$

) wind components were reconstructed at the six crossing points using the following relations (Peña & Mann Reference Peña and Mann2019):

\begin{align} \underbrace {\left [\begin{array}{l} v_{r_1} \\ v_{r_2} \end{array}\right ]}_{\mathbf{v_r}}=\underbrace {\left [\begin{array}{cc} \cos \zeta _1 \cos \phi _1 & \sin \zeta _1 \cos \phi _1 \\ \cos \zeta _2 \cos \phi _2 & \sin \zeta _2 \cos \phi _2 \end{array}\right ]}_{\mathbf{M}} \underbrace {\left [\begin{array}{l} v_{\textit{EW}} \\ v_{\textit{NS}} \end{array}\right ]}_{\mathbf{v}} \end{align}

\begin{align} \underbrace {\left [\begin{array}{l} v_{r_1} \\ v_{r_2} \end{array}\right ]}_{\mathbf{v_r}}=\underbrace {\left [\begin{array}{cc} \cos \zeta _1 \cos \phi _1 & \sin \zeta _1 \cos \phi _1 \\ \cos \zeta _2 \cos \phi _2 & \sin \zeta _2 \cos \phi _2 \end{array}\right ]}_{\mathbf{M}} \underbrace {\left [\begin{array}{l} v_{\textit{EW}} \\ v_{\textit{NS}} \end{array}\right ]}_{\mathbf{v}} \end{align}

and

The subscripts 1 and 2 refer to the lidars close to the church and lighthouse, respectively, whereas

![]() $\zeta$

is the azimuthal orientation of the beam and

$\zeta$

is the azimuthal orientation of the beam and

![]() $\phi$

is its elevation. This relation relies on the assumption that the projection of the vertical wind component along the lidar beam is negligible as compared with the radial wind speed. For instance, if the vertical component,

$\phi$

is its elevation. This relation relies on the assumption that the projection of the vertical wind component along the lidar beam is negligible as compared with the radial wind speed. For instance, if the vertical component,

![]() $w$

, is 1 ms

$w$

, is 1 ms

![]() $^{-1}$

then its projection along the lidar beam with an elevation angle of 10

$^{-1}$

then its projection along the lidar beam with an elevation angle of 10

![]() $^{\circ }$

is

$^{\circ }$

is

![]() $1\sin 10^{\circ } \approx 0.17$

ms

$1\sin 10^{\circ } \approx 0.17$

ms

![]() $^{-1}$

. This is about 1.7 % of the radial velocity measurement, if

$^{-1}$

. This is about 1.7 % of the radial velocity measurement, if

![]() $v_r = 10$

ms

$v_r = 10$

ms

![]() $^{-1}$

. Indeed, the projection of the vertical component along the lidar beam is between

$^{-1}$

. Indeed, the projection of the vertical component along the lidar beam is between

![]() $1\,\%\text{-}5\,\%$

of the radial wind velocity measurements for the range of elevation angle analysed in this study (refer table 2). The vertical velocity component also introduces a small bias in the measurements of the auto-spectra. This effect is discussed in more detail in the next section and at the end of Appendix B. Since the beams of the church and lighthouse lidars are approximately 90

$1\,\%\text{-}5\,\%$

of the radial wind velocity measurements for the range of elevation angle analysed in this study (refer table 2). The vertical velocity component also introduces a small bias in the measurements of the auto-spectra. This effect is discussed in more detail in the next section and at the end of Appendix B. Since the beams of the church and lighthouse lidars are approximately 90

![]() $^{\circ }$

apart, when using (2.1) and (2.2), the uncertainty in (2.1) is independent of the wind direction (Peña & Mann Reference Peña and Mann2019). However, reconstructing the horizontal wind requires simultaneous data from both lidars. Data availability after noise removal was not uniform across the five lidars. Some lidars showed noisier data than the rest, probably because they were older models (Sterenn) or had accumulated more dirt on the lens (Chinook). Consequently, the 10 min periods where (2.2) could not be applied were also removed from the dataset.

$^{\circ }$

apart, when using (2.1) and (2.2), the uncertainty in (2.1) is independent of the wind direction (Peña & Mann Reference Peña and Mann2019). However, reconstructing the horizontal wind requires simultaneous data from both lidars. Data availability after noise removal was not uniform across the five lidars. Some lidars showed noisier data than the rest, probably because they were older models (Sterenn) or had accumulated more dirt on the lens (Chinook). Consequently, the 10 min periods where (2.2) could not be applied were also removed from the dataset.

Subsequently, the horizontal wind speed,

![]() $u_{\textit{hor}}$

, and wind direction,

$u_{\textit{hor}}$

, and wind direction,

![]() $\theta$

, were computed:

$\theta$

, were computed:

Note that the wind direction will be expressed in the meteorological convention, where 0

![]() $^\circ$

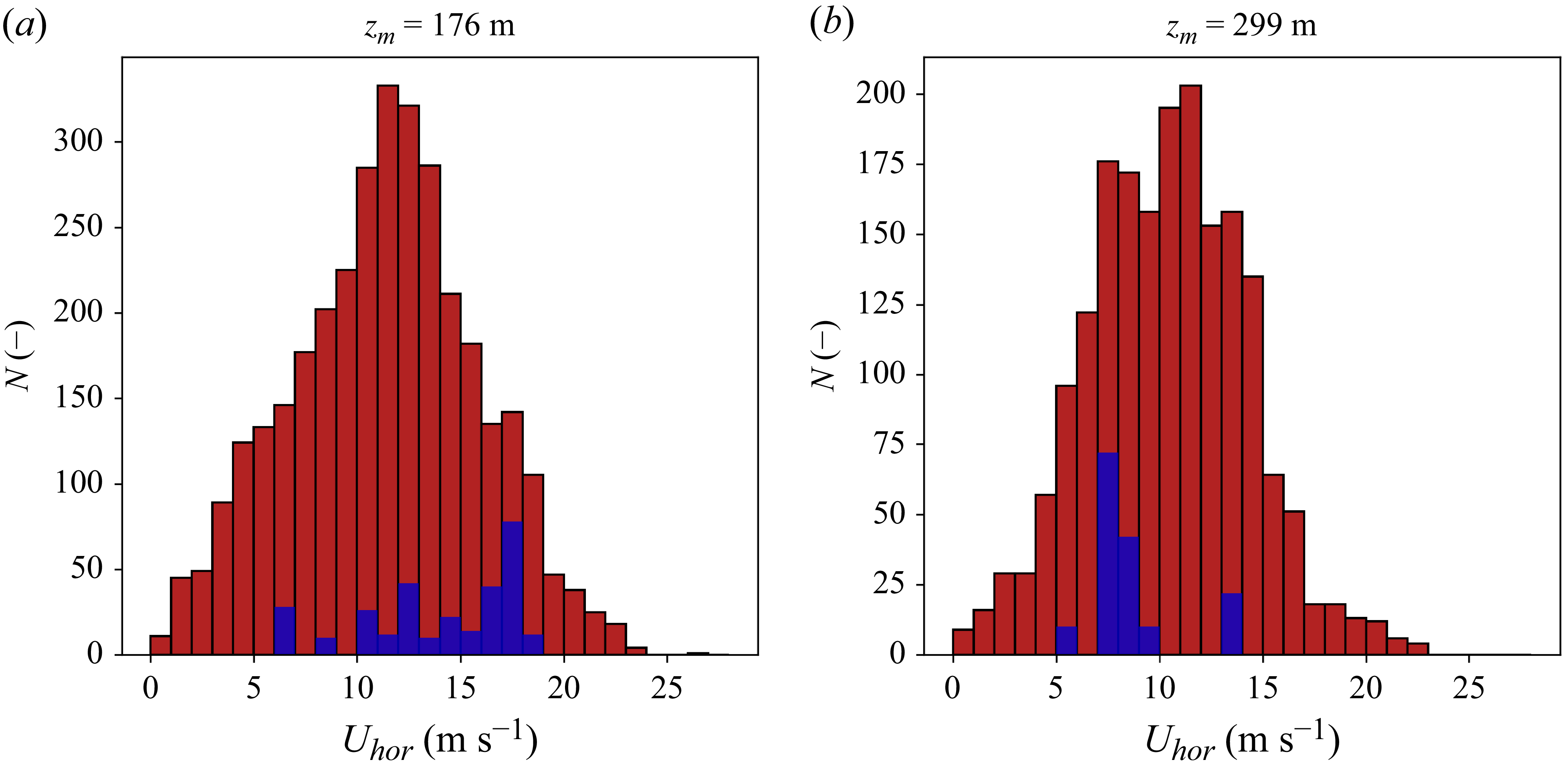

refers to wind blowing from true north. The histograms of the 10 minute mean horizontal wind speed (

$^\circ$

refers to wind blowing from true north. The histograms of the 10 minute mean horizontal wind speed (

![]() $U_{\textit{hor}}$

) and wind direction (

$U_{\textit{hor}}$

) and wind direction (

![]() $\varTheta$

) are shown in figures 4 and 5, where

$\varTheta$

) are shown in figures 4 and 5, where

![]() $z_m$

indicates the measurement height above sea level. The modal 10 min wind speed is between 11 and 12 ms

$z_m$

indicates the measurement height above sea level. The modal 10 min wind speed is between 11 and 12 ms

![]() $^{-1}$

. The maximum observed value of

$^{-1}$

. The maximum observed value of

![]() $U_{\textit{hor}}$

was 26.2 ms

$U_{\textit{hor}}$

was 26.2 ms

![]() $^{-1}$

. The modal wind direction was between 210

$^{-1}$

. The modal wind direction was between 210

![]() $^\circ$

and 220

$^\circ$

and 220

![]() $^\circ$

from the start of the campaign to the end of April 2024. While from May 2024 to the end of the campaign, it was between 290

$^\circ$

from the start of the campaign to the end of April 2024. While from May 2024 to the end of the campaign, it was between 290

![]() $^\circ$

and 300

$^\circ$

and 300

![]() $^\circ$

. This corresponds to westerly circulation over the northern mid-latitudes due to the Ferrel cell. Easterly winds are also frequently observed, but only westerly winds were analysed in this study since the scope is limited to marine atmospheric turbulence.

$^\circ$

. This corresponds to westerly circulation over the northern mid-latitudes due to the Ferrel cell. Easterly winds are also frequently observed, but only westerly winds were analysed in this study since the scope is limited to marine atmospheric turbulence.

Figure 4. The number of 10 min periods,

![]() $N$

, for different 10 min mean wind speed bins, computed at crossing point 2 for (a) configuration 1 and (b) configuration 2. The measurement height,

$N$

, for different 10 min mean wind speed bins, computed at crossing point 2 for (a) configuration 1 and (b) configuration 2. The measurement height,

![]() $z_m$

, is shown at the top of each figure. The data used in the final analysis are highlighted in blue.

$z_m$

, is shown at the top of each figure. The data used in the final analysis are highlighted in blue.

Figure 5. The number of 10 min periods,

![]() $N$

, for different 10 min mean wind direction bins plotted in polar coordinates and computed at crossing point 2 for (a) configuration 1 and (b) configuration 2. The measurement height,

$N$

, for different 10 min mean wind direction bins plotted in polar coordinates and computed at crossing point 2 for (a) configuration 1 and (b) configuration 2. The measurement height,

![]() $z_m$

, is shown at the top of each figure. The data used in the final analysis are highlighted in blue.

$z_m$

, is shown at the top of each figure. The data used in the final analysis are highlighted in blue.

This study aims to compare the measurements with the turbulence models down to frequencies lower than 10 min

![]() $^{-1}$

, similar to the work of Cheynet et al. (Reference Cheynet, Jakobsen and Reuder2018), Larsén et al. (Reference Larsén, Vincent and Larsen2013, Reference Larsén, Larsen and Petersen2016) and Syed & Mann (Reference Syed and Mann2024). Due to the scanning configuration of one of the lidars (Zonda), the duration of the longest continuous time series that can be reconstructed is 20 min. Consequently, from the dataset retained after the aforementioned data removal steps, we found two contiguous 10 min periods. These were attached to each other to create a time series that was 20 min in duration.

$^{-1}$

, similar to the work of Cheynet et al. (Reference Cheynet, Jakobsen and Reuder2018), Larsén et al. (Reference Larsén, Vincent and Larsen2013, Reference Larsén, Larsen and Petersen2016) and Syed & Mann (Reference Syed and Mann2024). Due to the scanning configuration of one of the lidars (Zonda), the duration of the longest continuous time series that can be reconstructed is 20 min. Consequently, from the dataset retained after the aforementioned data removal steps, we found two contiguous 10 min periods. These were attached to each other to create a time series that was 20 min in duration.

In this experiment, coherence was measured between the lateral separations,

![]() $\Delta _y$

, whose values are shown in table 3. Note that (3.5), (3.10) and (3.15) were used to quantify the coherence. The separations were obtained by selecting two intersection points from figure 3. The respective intersection points are shown in the second and third columns of table 3. For example, points 6 and 5 were horizontally separated by 50 m while the vertical separation (

$\Delta _y$

, whose values are shown in table 3. Note that (3.5), (3.10) and (3.15) were used to quantify the coherence. The separations were obtained by selecting two intersection points from figure 3. The respective intersection points are shown in the second and third columns of table 3. For example, points 6 and 5 were horizontally separated by 50 m while the vertical separation (

![]() $\Delta _y$

) was 4.5 m and 9 m in configurations 1 and 2, respectively. Moreover, the lateral coherence in this case was only computed for those 20-min periods where the mean wind direction (

$\Delta _y$

) was 4.5 m and 9 m in configurations 1 and 2, respectively. Moreover, the lateral coherence in this case was only computed for those 20-min periods where the mean wind direction (

![]() $\varTheta$

) was between 281

$\varTheta$

) was between 281

![]() $^{\circ }$

and 341

$^{\circ }$

and 341

![]() $^{\circ }$

. Since the analysis is now focused on 20-minute periods, the mean wind direction is also computed over a duration of 20 min. The wind direction bins shown in table 3 were obtained by considering a 30

$^{\circ }$

. Since the analysis is now focused on 20-minute periods, the mean wind direction is also computed over a duration of 20 min. The wind direction bins shown in table 3 were obtained by considering a 30

![]() $^{\circ }$

interval around the normal to the separation vector connecting the intersection points. The 20-min periods where the mean wind direction was outside these bins were also removed from the dataset. Measuring coherence also requires simultaneous data from both intersection points. As mentioned before, data from Sterenn and Chinook was noisier than data recorded by the other lidars. Thus, these two lidars had lower data availability after removal of noisy data based on

$^{\circ }$

interval around the normal to the separation vector connecting the intersection points. The 20-min periods where the mean wind direction was outside these bins were also removed from the dataset. Measuring coherence also requires simultaneous data from both intersection points. As mentioned before, data from Sterenn and Chinook was noisier than data recorded by the other lidars. Thus, these two lidars had lower data availability after removal of noisy data based on

![]() $\sigma _{v_r}$

and the modified KDE algorithm. Similarly, the data availability was lower at points 4, 5 and 6 compared with the rest. Thus, for a given separation, the 20-minute periods where simultaneous data from both points were not available were also discarded.

$\sigma _{v_r}$

and the modified KDE algorithm. Similarly, the data availability was lower at points 4, 5 and 6 compared with the rest. Thus, for a given separation, the 20-minute periods where simultaneous data from both points were not available were also discarded.

Turbulence is often analysed in the coordinate system where the

![]() $x$

axis is aligned with the mean wind direction, which varies in time and with height. Thus, the along-wind (

$x$

axis is aligned with the mean wind direction, which varies in time and with height. Thus, the along-wind (

![]() $u$

) and cross-wind (

$u$

) and cross-wind (

![]() $v$

) components are computed as

$v$

) components are computed as

where

![]() $\varTheta$

is the 20 min mean wind direction during a particular period in time and at the height where the time series of

$\varTheta$

is the 20 min mean wind direction during a particular period in time and at the height where the time series of

![]() $u_{\textit{hor}}$

and

$u_{\textit{hor}}$

and

![]() $\theta$

were measured. The analysis is also limited to data that is quasi-stationary. A linear fit (Angelou et al. Reference Angelou, Mann and Dubreuil-Boisclair2023) was computed to each 20 min time series and if the slope was greater than 2 ms

$\theta$

were measured. The analysis is also limited to data that is quasi-stationary. A linear fit (Angelou et al. Reference Angelou, Mann and Dubreuil-Boisclair2023) was computed to each 20 min time series and if the slope was greater than 2 ms

![]() $^{-1}$

h

$^{-1}$

h

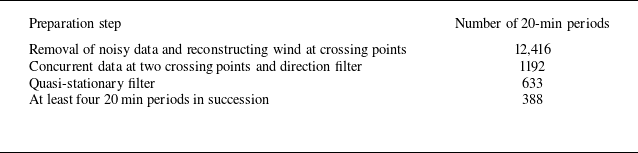

![]() $^{-1}$

then that period was rejected. For the final processing step, the data where at least four 20 min periods were present in succession was accepted. This is because each 20 min period is considered as a separate realisation and the auto-spectra and coherence will be averaged over at least four realisations. The data available after each processing step is shown in table 4 and is also highlighted in figures 4 and 5. The 388 periods from table 4 correspond to 50 ensembles. Since these ensembles will be referred to on many occasions in this study, an example of the first ensemble is discussed to explain the terminology and the binning of the processed data. The first ensemble contains data from 20 February 2024 01:00 UTC to 05:00 UTC. This corresponds to 12 samples each of which is 20 minutes long. The ensemble-mean wind direction was 294

$^{-1}$

then that period was rejected. For the final processing step, the data where at least four 20 min periods were present in succession was accepted. This is because each 20 min period is considered as a separate realisation and the auto-spectra and coherence will be averaged over at least four realisations. The data available after each processing step is shown in table 4 and is also highlighted in figures 4 and 5. The 388 periods from table 4 correspond to 50 ensembles. Since these ensembles will be referred to on many occasions in this study, an example of the first ensemble is discussed to explain the terminology and the binning of the processed data. The first ensemble contains data from 20 February 2024 01:00 UTC to 05:00 UTC. This corresponds to 12 samples each of which is 20 minutes long. The ensemble-mean wind direction was 294

![]() $^{\circ }$

while the ensemble-mean wind speed was 12.3 ms

$^{\circ }$

while the ensemble-mean wind speed was 12.3 ms

![]() $^{-1}$

. Since the realisations were quasi-stationary, the ensemble mean was representative of the mean wind speed and wind direction of each individual 20 min period. Moreover, the lidars Chinook, Brise and Sterenn recorded data that met the noise criteria defined earlier. Thus, this ensemble contains measurements of the lateral coherence between points 5 and 6 from figure 3 along with the auto-spectra at both the points.

$^{-1}$

. Since the realisations were quasi-stationary, the ensemble mean was representative of the mean wind speed and wind direction of each individual 20 min period. Moreover, the lidars Chinook, Brise and Sterenn recorded data that met the noise criteria defined earlier. Thus, this ensemble contains measurements of the lateral coherence between points 5 and 6 from figure 3 along with the auto-spectra at both the points.

Table 4. Overview of the processes applied on the raw lidar data to prepare it for the analysis of auto-spectra and lateral coherence. The subsequent data availability summed over all lidars or crossing points is shown in the second column.

2.3. Estimation of atmospheric stability

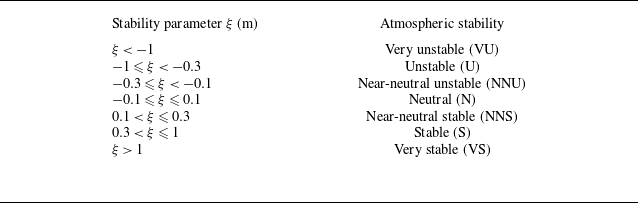

We aim to assign each of the 50 ensembles to a particular stability group based on the stability parameter,

![]() $\xi$

, and the classifications described in table 5. An implicit assumption in the analysis presented herein is that since data are quasi-stationary, time averaging can be replaced by ensemble averaging (Wyngaard Reference Wyngaard2010). Moreover, it must be emphasised that ensembles with the same stability are not binned together. Thus, even if two ensembles belong to the same stability group, they are analysed separately. This prevents averaging out phenomena that might not occur during all periods with the same stability. One such example is shown in § 3.4 where gravity waves are possibly detected during a period of very stable stratification.

$\xi$

, and the classifications described in table 5. An implicit assumption in the analysis presented herein is that since data are quasi-stationary, time averaging can be replaced by ensemble averaging (Wyngaard Reference Wyngaard2010). Moreover, it must be emphasised that ensembles with the same stability are not binned together. Thus, even if two ensembles belong to the same stability group, they are analysed separately. This prevents averaging out phenomena that might not occur during all periods with the same stability. One such example is shown in § 3.4 where gravity waves are possibly detected during a period of very stable stratification.

Table 5. Stability regimes used to classify the ensembles.

Table 5 is drawn from the stability classes used by Cheynet et al. (Reference Cheynet, Jakobsen and Reuder2018) while

![]() $\xi$

is the non-dimensional stability parameter:

$\xi$

is the non-dimensional stability parameter:

Here,

![]() $z_i$

is the height of the boundary layer and

$z_i$

is the height of the boundary layer and

![]() $L_{\textit{mo}}$

is the Monin-Obukhov length. The brackets,

$L_{\textit{mo}}$

is the Monin-Obukhov length. The brackets,

![]() $\left \langle \boldsymbol{\cdot }\right \rangle$

, represent ensemble averaging. Measurements of

$\left \langle \boldsymbol{\cdot }\right \rangle$

, represent ensemble averaging. Measurements of

![]() $z_i$

could be obtained from a ceilometer, however, measuring

$z_i$

could be obtained from a ceilometer, however, measuring

![]() $ {1}/{L_{\textit{mo}}}$

was not possible because there were no sonic anemometers present on site (due to logistical and economical constraints). Hence, the Monin–Obukhov length computed by WRF (Skamarock et al. Reference Skamarock, Klemp, Dudhia, Gill, Barker, Wang and Powers2005) simulations was used in the calculation of

$ {1}/{L_{\textit{mo}}}$

was not possible because there were no sonic anemometers present on site (due to logistical and economical constraints). Hence, the Monin–Obukhov length computed by WRF (Skamarock et al. Reference Skamarock, Klemp, Dudhia, Gill, Barker, Wang and Powers2005) simulations was used in the calculation of

![]() $\xi$

.

$\xi$

.

While several definitions exist for the boundary layer height (Stull Reference Stull1988), in this study,

![]() $z_i$

is defined as the height where the aerosol concentration reduces to its level in the free atmosphere. This is because measurements of the vertical profile of the aerosols in the atmosphere were readily available at the site. A Vaisala CL31 ceilometer was placed next to the church of Trans. It measured the vertical profile of the aerosol backscatter at a sampling interval of 16 s and with a vertical resolution of 10 m. Steyn, Baldi & Hoff (Reference Steyn, Baldi and Hoff1999) showed that under ideal cloudless conditions, the aerosol profile in a well-mixed boundary layer follows the shape of the Gauss error function. Thus, the boundary layer height could be computed by fitting the error function to measurements of the backscatter vertical profile. Note that the backscatter profiles were time averaged over a duration of 10 min to reduce noise and obtain a better fit with the error function. However, when clouds form within the boundary layer, it is not possible to detect

$z_i$

is defined as the height where the aerosol concentration reduces to its level in the free atmosphere. This is because measurements of the vertical profile of the aerosols in the atmosphere were readily available at the site. A Vaisala CL31 ceilometer was placed next to the church of Trans. It measured the vertical profile of the aerosol backscatter at a sampling interval of 16 s and with a vertical resolution of 10 m. Steyn, Baldi & Hoff (Reference Steyn, Baldi and Hoff1999) showed that under ideal cloudless conditions, the aerosol profile in a well-mixed boundary layer follows the shape of the Gauss error function. Thus, the boundary layer height could be computed by fitting the error function to measurements of the backscatter vertical profile. Note that the backscatter profiles were time averaged over a duration of 10 min to reduce noise and obtain a better fit with the error function. However, when clouds form within the boundary layer, it is not possible to detect

![]() $z_i$

from a ceilometer (or any laser-based remote sensing method) (Hennemuth & Lammert Reference Hennemuth and Lammert2006) because the cloud absorbs light from the laser and no backscatter is obtained after a certain height within the cloud. In such instances, the height where the backscatter becomes negligible is taken as a rough estimate of

$z_i$

from a ceilometer (or any laser-based remote sensing method) (Hennemuth & Lammert Reference Hennemuth and Lammert2006) because the cloud absorbs light from the laser and no backscatter is obtained after a certain height within the cloud. In such instances, the height where the backscatter becomes negligible is taken as a rough estimate of

![]() $z_i$

. The implications of the uncertainty in estimations of

$z_i$

. The implications of the uncertainty in estimations of

![]() $z_i$

under cloudy conditions are discussed at the end of this section. We refer the reader to Appendix A for more details of boundary layer height estimation from ceilometer measurements.

$z_i$

under cloudy conditions are discussed at the end of this section. We refer the reader to Appendix A for more details of boundary layer height estimation from ceilometer measurements.

The Monin–Obukhov length was determined from WRF simulations carried out by Olsen et al. (Reference Olsen, Hahmann, de, Alonso, Žagar and Dörenkämper2025) as the measurement site was present within the innermost domain of the simulations. The simulations also covered the entire duration of the campaign. Weather Research and Forecast computes the inverse Monin–Obukhov length (

![]() $ {1}/{L_{\textit{mo}}}$

) using bulk estimates of the heat flux from the temperature difference between the surface and the first model level. This is coupled to the planetary boundary layer scheme (PBL) and Monin–Obukhov similarity theory (Peña & Hahmann Reference Peña and Hahmann2012; Skamarock et al. Reference Skamarock, Klemp, Dudhia, Gill, Barker, Wang and Powers2005). The configuration with the three-dimensional turbulent kinetic energy (3DTKE) PBL from Olsen et al. (Reference Olsen, Hahmann, de, Alonso, Žagar and Dörenkämper2025) was used to obtain estimates of

$ {1}/{L_{\textit{mo}}}$

) using bulk estimates of the heat flux from the temperature difference between the surface and the first model level. This is coupled to the planetary boundary layer scheme (PBL) and Monin–Obukhov similarity theory (Peña & Hahmann Reference Peña and Hahmann2012; Skamarock et al. Reference Skamarock, Klemp, Dudhia, Gill, Barker, Wang and Powers2005). The configuration with the three-dimensional turbulent kinetic energy (3DTKE) PBL from Olsen et al. (Reference Olsen, Hahmann, de, Alonso, Žagar and Dörenkämper2025) was used to obtain estimates of

![]() $ {1}/{L_{\textit{mo}}}$

at intervals of 30 min.

$ {1}/{L_{\textit{mo}}}$

at intervals of 30 min.

Since

![]() $z_i$

and

$z_i$

and

![]() $ {1}/{L_{\textit{mo}}}$

were sampled at different rates (10 min and 30 min, respectively), they were ensemble averaged separately such that

$ {1}/{L_{\textit{mo}}}$

were sampled at different rates (10 min and 30 min, respectively), they were ensemble averaged separately such that

As an example of stability classification, consider the first ensemble of wind speed measurements. It contains data from 20 February 2024 01:00 UTC to 05:00 UTC. Hence, concurrent data (corresponding to 36 periods of 10 minutes) from the ceilometer were used to determine

![]() $\left \langle z_i \right \rangle$

. Similarly, concurrent data (eight samples) were retrieved from the WRF simulations to find

$\left \langle z_i \right \rangle$

. Similarly, concurrent data (eight samples) were retrieved from the WRF simulations to find

![]() $ \left \langle {1}/{L_{\textit{mo}}} \right \rangle$

. Since

$ \left \langle {1}/{L_{\textit{mo}}} \right \rangle$

. Since

![]() $\xi$

was found to be

$\xi$

was found to be

![]() $-0.78$

, this ensemble period was classified as stable (S) according to table 5. The ensemble-averaged value of

$-0.78$

, this ensemble period was classified as stable (S) according to table 5. The ensemble-averaged value of

![]() $\xi$

was representative of the stability during the entire ensemble period (which in some cases was 8 hours long), as the individual 20 min periods never showed any abrupt changes in the boundary layer height or the Monin–Obukhov length. Daily variations in stability were also not observed at the experimental site as it is located near shore where the global stability varies on a seasonal basis (Sathe et al. Reference Sathe, Gryning and Peña2011a

). Indeed, stable atmospheric conditions were commonly observed during the period from February to late April while unstable conditions were more frequent from early May till the end of the campaign.

$\xi$

was representative of the stability during the entire ensemble period (which in some cases was 8 hours long), as the individual 20 min periods never showed any abrupt changes in the boundary layer height or the Monin–Obukhov length. Daily variations in stability were also not observed at the experimental site as it is located near shore where the global stability varies on a seasonal basis (Sathe et al. Reference Sathe, Gryning and Peña2011a

). Indeed, stable atmospheric conditions were commonly observed during the period from February to late April while unstable conditions were more frequent from early May till the end of the campaign.

The stability classification based on ceilometer measurements and WRF has two sources of uncertainty. As mentioned previously, accurately determining

![]() $z_i$

under cloudy conditions is not possible. In these conditions,

$z_i$

under cloudy conditions is not possible. In these conditions,

![]() $z_i$

was estimated as the height at which the backscatter signal was lost within the cloud. This certainly underestimates the actual boundary layer height. The second source of uncertainty is that to our knowledge, the

$z_i$

was estimated as the height at which the backscatter signal was lost within the cloud. This certainly underestimates the actual boundary layer height. The second source of uncertainty is that to our knowledge, the

![]() $L_{\textit{mo}}$

from WRF using the 3DTKE scheme has never been validated against measurements. Peña & Hahmann (Reference Peña and Hahmann2012) found that estimates of

$L_{\textit{mo}}$

from WRF using the 3DTKE scheme has never been validated against measurements. Peña & Hahmann (Reference Peña and Hahmann2012) found that estimates of

![]() $L_{\textit{mo}}$

from WRF and sonic anemometers were strongly correlated in the near-neutral region but showed considerable scatter for the more extreme stability conditions when using the Yonsei University (YSU) PBL scheme. Both 3DTKE and YSU show similar behaviour (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Bao, Chen and Grell2018), for instance, in predicting the potential temperature profile. Consequently, the conclusions of Peña & Hahmann (Reference Peña and Hahmann2012) may also be valid for the 3DTKE scheme. Thus, given these uncertainties, the stability classification of each ensemble was verified with the measured vertical profiles of ensemble-averaged wind speed and direction. Appendix C provides more details along with some examples. While the verification was based on qualitative analysis, wind shear and veer are often strong indicators of stability. Thus, this verification with an independent set of measurements provided sufficient confidence in the stability classification.

$L_{\textit{mo}}$

from WRF and sonic anemometers were strongly correlated in the near-neutral region but showed considerable scatter for the more extreme stability conditions when using the Yonsei University (YSU) PBL scheme. Both 3DTKE and YSU show similar behaviour (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Bao, Chen and Grell2018), for instance, in predicting the potential temperature profile. Consequently, the conclusions of Peña & Hahmann (Reference Peña and Hahmann2012) may also be valid for the 3DTKE scheme. Thus, given these uncertainties, the stability classification of each ensemble was verified with the measured vertical profiles of ensemble-averaged wind speed and direction. Appendix C provides more details along with some examples. While the verification was based on qualitative analysis, wind shear and veer are often strong indicators of stability. Thus, this verification with an independent set of measurements provided sufficient confidence in the stability classification.

3. Results

3.1. Description of turbulence models

The measurements of auto-spectra and lateral coherence were compared with the Mann (Reference Mann1994) and Syed & Mann (Reference Syed and Mann2024) models, henceforth referred to as M94 and S24, respectively. The M94 model describes the spatial structure of homogeneous, anisotropic, neutral, surface layer turbulence using rapid distortion theory and a parametrisation of the eddy lifetime. Although Mann (Reference Mann1994) presents two models: uniform shear (US) and uniform shear plus blockage (US + B), only the former is within the scope of this paper. The US model has three parameters:

![]() $L$

,

$L$

,

![]() $\varGamma$

and

$\varGamma$

and

![]() $\alpha \varepsilon ^{({2}/{3})}$

. Here

$\alpha \varepsilon ^{({2}/{3})}$

. Here

![]() $L$

is a length scale that is related to the size of the most energetic eddies;

$L$

is a length scale that is related to the size of the most energetic eddies;

![]() $\varGamma$

is the anisotropy parameter and defines the lifetime of the eddies. The definition of

$\varGamma$

is the anisotropy parameter and defines the lifetime of the eddies. The definition of

![]() $\varGamma$

can be found in Mann (Reference Mann1994, Equation (3.6)). It relates the eddy lifetime to the linear shear that rapidly distorts the initial isotropic von Kármán spectra (von Kármán Reference von Kármán1948) into the anisotropic spectra. Thus, as

$\varGamma$

can be found in Mann (Reference Mann1994, Equation (3.6)). It relates the eddy lifetime to the linear shear that rapidly distorts the initial isotropic von Kármán spectra (von Kármán Reference von Kármán1948) into the anisotropic spectra. Thus, as

![]() $\varGamma$

increases, the turbulent eddies live for a longer time and suffer more distortion, resulting in turbulence that is more anisotropic. Finally,

$\varGamma$

increases, the turbulent eddies live for a longer time and suffer more distortion, resulting in turbulence that is more anisotropic. Finally,

![]() $\alpha \varepsilon ^{({2}/{3})}$

is a scaling parameter and the level of the inertial subrange in the initial von Kármán spectra. Herein,

$\alpha \varepsilon ^{({2}/{3})}$

is a scaling parameter and the level of the inertial subrange in the initial von Kármán spectra. Herein,

![]() $\alpha$

is the spectral Kolmogorov constant and

$\alpha$

is the spectral Kolmogorov constant and

![]() $\varepsilon$

is the turbulent energy dissipation rate. These parameters are typically computed by fitting the modelled auto-spectra to the measured auto-spectra. Note that in the equations that follow, there is no summation over repeated indices.

$\varepsilon$

is the turbulent energy dissipation rate. These parameters are typically computed by fitting the modelled auto-spectra to the measured auto-spectra. Note that in the equations that follow, there is no summation over repeated indices.

The modelled auto-spectrum is given by

where

![]() $F_{i} (k_1 )$

is the auto-spectrum in wavenumber space:

$F_{i} (k_1 )$

is the auto-spectrum in wavenumber space:

![]() $\boldsymbol{k} = (k_1, k_2, k_3)$

and

$\boldsymbol{k} = (k_1, k_2, k_3)$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{\varPhi } (\boldsymbol{k} )$

is the spectral tensor derived by Mann (Reference Mann1994). Here the indices 1, 2 and 3 refer to the along-wind (

$\boldsymbol{\varPhi } (\boldsymbol{k} )$

is the spectral tensor derived by Mann (Reference Mann1994). Here the indices 1, 2 and 3 refer to the along-wind (

![]() $u$

), cross-wind (

$u$

), cross-wind (

![]() $v$

) and vertical components (

$v$

) and vertical components (

![]() $w$

), respectively. In general, the spectral tensor is defined as the Fourier transform of the two-point covariance tensor,

$w$

), respectively. In general, the spectral tensor is defined as the Fourier transform of the two-point covariance tensor,

![]() $R_{\textit{ij}}(\boldsymbol{r})$

(Lumley Reference Lumley1970):

$R_{\textit{ij}}(\boldsymbol{r})$

(Lumley Reference Lumley1970):

and

Here,

![]() $\left \langle \boldsymbol{\cdot }\right \rangle$

denotes ensemble averaging and

$\left \langle \boldsymbol{\cdot }\right \rangle$

denotes ensemble averaging and

![]() $\boldsymbol{r}$

is the separation vector.

$\boldsymbol{r}$

is the separation vector.

The components of the spectral tensor can be calculated using equations (3.18) to (3.23) of Mann (Reference Mann1994). Although none of these equations show an explicit dependence on

![]() $(L, \varGamma , \alpha \varepsilon ^{2/3})$

, they are implicitly dependent on these parameters via the non-dimensional time,

$(L, \varGamma , \alpha \varepsilon ^{2/3})$

, they are implicitly dependent on these parameters via the non-dimensional time,

![]() $\beta$

, and the initial energy spectrum,

$\beta$

, and the initial energy spectrum,

![]() $E(k_0)$

(refer to equations (2.17), (3.12) and (3.6) of Mann Reference Mann1994). As a consequence,

$E(k_0)$

(refer to equations (2.17), (3.12) and (3.6) of Mann Reference Mann1994). As a consequence,

![]() $(L, \varGamma , \alpha \varepsilon ^{2/3})$

completely determine the values of the spectral tensor. Since it is very difficult to measure the spectral tensor directly, the model is fitted to the measurements via the auto-spectrum. This is achieved by determining the values of

$(L, \varGamma , \alpha \varepsilon ^{2/3})$

completely determine the values of the spectral tensor. Since it is very difficult to measure the spectral tensor directly, the model is fitted to the measurements via the auto-spectrum. This is achieved by determining the values of

![]() $(L, \varGamma , \alpha \varepsilon ^{2/3})$

that minimise the difference or error between the model and the measurements. In this context, (3.1) is more intuitive than any definition available in Mann (Reference Mann1994).

$(L, \varGamma , \alpha \varepsilon ^{2/3})$

that minimise the difference or error between the model and the measurements. In this context, (3.1) is more intuitive than any definition available in Mann (Reference Mann1994).

Note that (3.1) is calculated numerically by providing

![]() $(L, \varGamma , \alpha \varepsilon ^{2/3})$

as input. The error,

$(L, \varGamma , \alpha \varepsilon ^{2/3})$

as input. The error,

![]() ${\chi }^2$

, between the modelled auto-spectra and the measured auto-spectra is defined as

${\chi }^2$

, between the modelled auto-spectra and the measured auto-spectra is defined as

\begin{align} {\chi }^2\left (L, \varGamma , \alpha \varepsilon ^{\frac {2}{3}}\right )=\sum _{i=1}^2 \sum _{n=1}^N \left [ \log \left ( k^n_1 F_{i} \right )- \log \left ( k^n_1 F_{i, m} \right ) \right ]^2 \!, \end{align}

\begin{align} {\chi }^2\left (L, \varGamma , \alpha \varepsilon ^{\frac {2}{3}}\right )=\sum _{i=1}^2 \sum _{n=1}^N \left [ \log \left ( k^n_1 F_{i} \right )- \log \left ( k^n_1 F_{i, m} \right ) \right ]^2 \!, \end{align}

where the subscript m refers to the measured spectra and the dependence of

![]() $F_i$

on

$F_i$

on

![]() $(L, \varGamma , \alpha \varepsilon ^{2/3})$

is dropped for convenience. Moreover,

$(L, \varGamma , \alpha \varepsilon ^{2/3})$

is dropped for convenience. Moreover,

![]() $k_1$

is discretised on a grid of

$k_1$

is discretised on a grid of

![]() $N$

points. Equation (3.4) is the least-squared error between model and measurements summed over all wavenumbers as well as the

$N$

points. Equation (3.4) is the least-squared error between model and measurements summed over all wavenumbers as well as the

![]() $u$

,

$u$

,

![]() $v$

components (hence,

$v$

components (hence,

![]() $i= 1, 2$

). The

$i= 1, 2$

). The

![]() $w$

component was not included as the lidars only measured the horizontal wind component. The resulting implications are discussed at the end of this subsection. Here

$w$

component was not included as the lidars only measured the horizontal wind component. The resulting implications are discussed at the end of this subsection. Here

![]() ${\chi }^2$

was minimised by a downhill simplex algorithm (McKinnon Reference McKinnon1998) by providing a grid of

${\chi }^2$

was minimised by a downhill simplex algorithm (McKinnon Reference McKinnon1998) by providing a grid of

![]() $(L, \varGamma , \alpha \varepsilon ^{2/3})$

as input, resulting in the model being fitted to the measurements. Note that

$(L, \varGamma , \alpha \varepsilon ^{2/3})$

as input, resulting in the model being fitted to the measurements. Note that

![]() $k_1F_i$

is typically not much larger than zero. Consequently, the absolute magnitude of the error was 10

$k_1F_i$

is typically not much larger than zero. Consequently, the absolute magnitude of the error was 10

![]() $^{-4}$

and the minimisation algorithm converged very slowly. Thus, the logarithm of

$^{-4}$

and the minimisation algorithm converged very slowly. Thus, the logarithm of

![]() $k_1F_i$

and

$k_1F_i$

and

![]() $k_1F_{i, m}$

was used to enhance the convergence speed.

$k_1F_{i, m}$

was used to enhance the convergence speed.

The parameters obtained from (3.4) are then used to compute the theoretical coherence,

![]() $\gamma$

,

$\gamma$

,

\begin{align} \gamma _{\textit{ij}}\left (k_1, \Delta _y, \Delta _z\right )=\frac {\mathfrak{R}\left (\chi _{\textit{ij}}\left (k_1, \Delta _y, \Delta _z\right )\right )}{\sqrt {F_i\left (k_1\right ) F_j\left (k_1\right )}}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \gamma _{\textit{ij}}\left (k_1, \Delta _y, \Delta _z\right )=\frac {\mathfrak{R}\left (\chi _{\textit{ij}}\left (k_1, \Delta _y, \Delta _z\right )\right )}{\sqrt {F_i\left (k_1\right ) F_j\left (k_1\right )}}, \end{align}

where

![]() $\mathfrak{R}(\boldsymbol{\cdot })$

refers to the real part of a complex number,

$\mathfrak{R}(\boldsymbol{\cdot })$

refers to the real part of a complex number,

![]() $\chi _{\textit{ij}}$

, which itself is defined as

$\chi _{\textit{ij}}$

, which itself is defined as

Note that in (3.5) and (3.6) the dependence on the parameters has been dropped for convenience. Moreover, the cross-spectrum in (3.6) is defined for

![]() $i=j$

as well as

$i=j$

as well as

![]() $i \neq j$

.

$i \neq j$

.

Here

![]() $\gamma$

is more formally referred to as the co-coherence because it depends on the real part of the cross-spectrum (also called the co-spectrum). On the other hand, the quad-coherence is defined as the ratio of the imaginary part of the cross-spectrum to the square root of the product of the auto-spectra. In this study, the quad-coherence is not analysed and, for convenience, the co-coherence is henceforth called the coherence.

$\gamma$

is more formally referred to as the co-coherence because it depends on the real part of the cross-spectrum (also called the co-spectrum). On the other hand, the quad-coherence is defined as the ratio of the imaginary part of the cross-spectrum to the square root of the product of the auto-spectra. In this study, the quad-coherence is not analysed and, for convenience, the co-coherence is henceforth called the coherence.

Coherence is the correlation in wavenumber space. Thus, if a wind component (say

![]() $u$

) is completely correlated at a certain wavenumber (

$u$

) is completely correlated at a certain wavenumber (

![]() $k_1$

) at two points in space, separated horizontally by

$k_1$

) at two points in space, separated horizontally by

![]() $\Delta _y$

and vertically by

$\Delta _y$

and vertically by

![]() $\Delta _z$

, then

$\Delta _z$

, then

![]() $\gamma _{\textit{uu}}(k_1, \Delta _y, \Delta _z) = 1$

. On the contrary, if

$\gamma _{\textit{uu}}(k_1, \Delta _y, \Delta _z) = 1$

. On the contrary, if

![]() $u$

is decorrelated at the two points then

$u$

is decorrelated at the two points then

![]() $\gamma _{\textit{uu}}(k_1, \Delta _y, \Delta _z) = 0$

.

$\gamma _{\textit{uu}}(k_1, \Delta _y, \Delta _z) = 0$

.

Although the equations in this subsection have been defined in wavenumber space, the measurements are obtained in frequency space. To move between these two representations, Taylor’s hypothesis will be used. De Maré & Mann (Reference de Maré and Mann2016) extended M94 using a Lagrangian framework to derive a four-dimensional space–time representation of the spectral tensor. This version of the spectral tensor did not rely on Taylor’s hypothesis as it could directly predict the auto-spectra and coherence in the frequency domain. However, de Maré & Mann (Reference de Maré and Mann2016) found that it did not result in any significant improvement over Mann (Reference Mann1994) except in predicting the

![]() $uw$

cross-spectrum, which is not included in the present analysis. Thus, Taylor’s hypothesis is assumed to be a reasonable approximation for fluctuations in the streamwise direction. To determine the convective velocity used in Taylor’s hypothesis, we also assume that the time average is equal to the ensemble average for the quasi-stationary data analysed in this study.

$uw$

cross-spectrum, which is not included in the present analysis. Thus, Taylor’s hypothesis is assumed to be a reasonable approximation for fluctuations in the streamwise direction. To determine the convective velocity used in Taylor’s hypothesis, we also assume that the time average is equal to the ensemble average for the quasi-stationary data analysed in this study.

Motivated by the results of Nybø et al. (Reference Nybø, Nielsen, Reuder, Churchfield and Godvik2020) and Doubrawa et al. (Reference Doubrawa, Churchfield, Godvik and Sirnivas2019) as well as the observations of Cheynet et al. (Reference Cheynet, Jakobsen and Reuder2018) and Larsén et al. (Reference Larsén, Larsen and Petersen2016, Reference Larsén, Larsen, Petersen and Mikkelsen2021), M94 was extended to account for mesoscale turbulence (Syed & Mann Reference Syed and Mann2024). In S24, mesoscale turbulence is assumed to be 2D anisotropic and modelled using the

![]() $-5/3$

scaling observed beyond the spectral gap by Gage & Nastrom (Reference Gage and Nastrom1986) and Lindborg (Reference Lindborg1999). Note that 2D means two components of velocity (

$-5/3$

scaling observed beyond the spectral gap by Gage & Nastrom (Reference Gage and Nastrom1986) and Lindborg (Reference Lindborg1999). Note that 2D means two components of velocity (

![]() $u$

and

$u$

and

![]() $v$

) defined over the two horizontal directions of space (2D2C). This terminology is in line with the work of Gage & Nastrom (Reference Gage and Nastrom1986), Lindborg (Reference Lindborg1999) and Syed & Mann (Reference Syed and Mann2024) and will be used throughout the rest of this study. Thus, 3D also means three components of velocity and three directions of space (3D3C).

$v$

) defined over the two horizontal directions of space (2D2C). This terminology is in line with the work of Gage & Nastrom (Reference Gage and Nastrom1986), Lindborg (Reference Lindborg1999) and Syed & Mann (Reference Syed and Mann2024) and will be used throughout the rest of this study. Thus, 3D also means three components of velocity and three directions of space (3D3C).

The S24 model uses the Mann US model for the smaller scales such that together, the 2D + 3D model, can describe turbulence down to frequencies of

![]() $\sim 1$

$\sim 1$

![]() $\mathrm{hr}^{-1}$

. It includes only two additional parameters:

$\mathrm{hr}^{-1}$

. It includes only two additional parameters:

![]() $\psi$

and

$\psi$

and

![]() $c$

. Here

$c$

. Here

![]() $\psi$

is an anisotropy parameter for the mesoscales and is equal to 45

$\psi$

is an anisotropy parameter for the mesoscales and is equal to 45

![]() $^\circ$

for isotropic turbulence. It is determined via

$^\circ$

for isotropic turbulence. It is determined via

\begin{align} \psi =\arctan \left (\sqrt {\frac {3}{5} \frac {F_{2}}{F_{1}}}\right ) \!. \end{align}

\begin{align} \psi =\arctan \left (\sqrt {\frac {3}{5} \frac {F_{2}}{F_{1}}}\right ) \!. \end{align}

Although, (3.7) implies that

![]() $\psi$

is a function of

$\psi$

is a function of

![]() $k_1$

,

$k_1$

,

![]() $\psi$

is a constant. This is because S24 assumes scale-independent anisotropy for mesoscale turbulence. Thus,

$\psi$

is a constant. This is because S24 assumes scale-independent anisotropy for mesoscale turbulence. Thus,

![]() $\psi$

is computed by first averaging

$\psi$

is computed by first averaging

![]() $F_1$

and

$F_1$

and

![]() $F_2$

over all values of

$F_2$

over all values of

![]() $k_1$

than 10

$k_1$

than 10

![]() $^{-3}$

m and then applying (3.7). The implications of this assumption are discussed in Syed & Mann (Reference Syed2024). Here

$^{-3}$

m and then applying (3.7). The implications of this assumption are discussed in Syed & Mann (Reference Syed2024). Here

![]() $c$

is a scaling parameter that is zero when no mesoscale turbulence is present (or when turbulence is 3D and microscale) and is found via the fitting procedure described earlier. In other words, it is the constant of proportionality in the 2D energy spectrum (refer to equation (5) of Syed & Mann Reference Syed2024).

$c$

is a scaling parameter that is zero when no mesoscale turbulence is present (or when turbulence is 3D and microscale) and is found via the fitting procedure described earlier. In other words, it is the constant of proportionality in the 2D energy spectrum (refer to equation (5) of Syed & Mann Reference Syed2024).

3.2. Auto-spectra

The one-point spectra or auto-spectra of turbulence

![]() $S_i(f)$

are also defined as the Fourier transforms of the autocorrelation functions

$S_i(f)$

are also defined as the Fourier transforms of the autocorrelation functions

![]() $R_i(\tau )$

:

$R_i(\tau )$

:

Here

![]() $R_i(\tau )$

are defined as

$R_i(\tau )$

are defined as

Note that

![]() $u_i(t)$

is the time series of the

$u_i(t)$

is the time series of the

![]() $i$

th wind speed component (

$i$

th wind speed component (

![]() $u_1 = u$

and

$u_1 = u$

and

![]() $u_2 = v$

) measured at a particular point in space and

$u_2 = v$

) measured at a particular point in space and

![]() $\tau$

is the time lag. Here

$\tau$

is the time lag. Here

![]() $S_i(f)$

can be related to

$S_i(f)$

can be related to

![]() $F_i(k)$

by Taylor’s hypothesis. In practice, (3.8) is computationally expensive and consequently the measured spectra are calculated by (Lumley Reference Lumley1970)

$F_i(k)$

by Taylor’s hypothesis. In practice, (3.8) is computationally expensive and consequently the measured spectra are calculated by (Lumley Reference Lumley1970)

\begin{align} S_i \left ( f \right ) = \frac {2\pi }{N_kT} \sum _{k = 1}^{N_k} \big | \mathrm{u}_i^k\left (f, T\right ) \big |^2, \end{align}

\begin{align} S_i \left ( f \right ) = \frac {2\pi }{N_kT} \sum _{k = 1}^{N_k} \big | \mathrm{u}_i^k\left (f, T\right ) \big |^2, \end{align}

where

is the Fourier transform of the kth realisation or sample of length

![]() $T$

seconds taken from an ensemble of

$T$

seconds taken from an ensemble of

![]() $N_k$

samples. Note that (3.10) implies ensemble averaging over

$N_k$

samples. Note that (3.10) implies ensemble averaging over

![]() $N_k$

samples. As mentioned in the previous section, 50 ensembles were left after post processing the raw lidar data. Each sample within the ensembles was 20 min in duration (

$N_k$

samples. As mentioned in the previous section, 50 ensembles were left after post processing the raw lidar data. Each sample within the ensembles was 20 min in duration (

![]() $T = 1200$

s), while

$T = 1200$

s), while

![]() $N_k$

was always greater than or equal to 4. Subsequently, the measured auto-spectra were computed using (3.10). Here

$N_k$

was always greater than or equal to 4. Subsequently, the measured auto-spectra were computed using (3.10). Here

![]() $S_i(f)$

was also averaged over logarithmically spaced frequency bins to further reduce the scatter in the measurements at the high frequency end of the spectra. This procedure is referred to as ‘log-smoothing’ and is explained as follows. The frequencies are divided into

$S_i(f)$

was also averaged over logarithmically spaced frequency bins to further reduce the scatter in the measurements at the high frequency end of the spectra. This procedure is referred to as ‘log-smoothing’ and is explained as follows. The frequencies are divided into

![]() $n_{\kern-1.5pt f}$

bins, i.e.

$n_{\kern-1.5pt f}$

bins, i.e.

where

![]() $f_{N}$

and

$f_{N}$

and

![]() $f_{1}$

are the highest and lowest frequencies in the spectra. The parameter

$f_{1}$

are the highest and lowest frequencies in the spectra. The parameter

![]() $d_{\kern-1.5pt f}$

is an input and determines the number of bins per decade. We find that

$d_{\kern-1.5pt f}$

is an input and determines the number of bins per decade. We find that

![]() $d_{\kern-1.5pt f} = 12$

sufficiently reduces noise while avoiding any distortions in the spectra. Consequently, the number of frequencies in each bin

$d_{\kern-1.5pt f} = 12$

sufficiently reduces noise while avoiding any distortions in the spectra. Consequently, the number of frequencies in each bin

![]() $N_b{_i}$

is given by

$N_b{_i}$

is given by

where

![]() $\lfloor \boldsymbol{\cdot }\rfloor$

denotes the floor function and

$\lfloor \boldsymbol{\cdot }\rfloor$

denotes the floor function and

![]() $i = 1, \ldots , n_{\kern-1.5pt f}$

. However, a few bins have

$i = 1, \ldots , n_{\kern-1.5pt f}$

. However, a few bins have

![]() $N_b{_i}= 0$

and these are discarded. This means that the effective number of bins are less than

$N_b{_i}= 0$

and these are discarded. This means that the effective number of bins are less than

![]() $n_{\kern-1.5pt f}$

. Thus, the statistical uncertainty quantified by the standard deviation in the ensemble-averaged and log-smoothened measured auto-spectra

$n_{\kern-1.5pt f}$

. Thus, the statistical uncertainty quantified by the standard deviation in the ensemble-averaged and log-smoothened measured auto-spectra

![]() $\sigma (S_i)$

is (Mann Reference Mann1994)

$\sigma (S_i)$

is (Mann Reference Mann1994)

In addition to the statistical uncertainty, measurements of auto-spectra from lidars can suffer from systematic biases as a result of two separate effects: lidar low-pass filtering and cross-contamination (Sathe et al. Reference Sathe, Mann, Gottschall and Courtney2011b