Introduction

Interest in urban agriculture is rising worldwide and turning toward green roofs as a space to grow crops in cities to achieve food security, access, and resiliency (Whittinghill and Rowe, Reference Whittinghill and Rowe2011; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Barbarossa, Erisman and Mogollón2024). The creation of green spaces in cities to support human well-being presents an opportunity to re-localize food production, access, and distribution, while simultaneously enhancing other important ecosystem services (Knapp and MacIvor, Reference Knapp and MacIvor2023). Extensive green roofs (EGRs) are a potential space for both growing food crops and citizen engagement. Furthermore, expanding the typology of green spaces promoting urban agriculture promises to help meet key environmental goals, including greenhouse gas reductions, while generating socioeconomically sustainable and equitable systems. Therefore, apart from the standard ecosystem services accounted for in green roof design (Williams, Lundholm and MacIvor, Reference Williams, Lundholm and MacIvor2014; Xie, Lundholm and Scott MacIvor, Reference Xie, Lundholm and Scott MacIvor2018; Ndayambaje, MacIvor and Cadotte, Reference Ndayambaje, MacIvor and Cadotte2024), with adequate modification to maintenance and accessibility, these spaces can implement additional services, such as food production.

EGRs are the most common type of green roof in urban areas as they are inexpensive to manufacture, easy to implement on new or existing structures, and require less maintenance compared with intensive green roofs (IGRs) (MacIvor and Lundholm, Reference MacIvor and Lundholm2011). These are generally characterized by a shallow substrate of less than 15 cm deep made of various grades of crushed brick or other inorganic aggregate mixed with small amounts of organic matter (Oberndorfer et al., Reference Oberndorfer, Lundholm, Bass, Coffman, Doshi, Dunnett, Gaffin, Köhler, Liu and Rowe2007; FLL, 2018). Vegetative cover consists largely of self-sustaining plants that are adapted to extreme conditions and have high regeneration capacities (FLL, 2018). Globally, these communities are largely dominated by a single genus, Sedum (Family: Crassulaceae), which are low-growing succulents adapted to European alpine and rocky meadows, with shallow roots and other drought tolerance strategies (Clausen, Reference Clausen1966; Gravatt and Martin, Reference Gravatt and Martin1992). Many different crops can be successfully grown on IGRs with their deeper, more nutrient-rich substrates. New York City’s The Brooklyn Grange atop the former Brooklyn Navy Yard is a 0.6 ha IGR producing 11 000–13 000 t y−1 of organic vegetables (Harada and Whitlow, Reference Harada and Whitlow2020). Resource-limited EGR environments make species selection difficult, especially for crop growth. Ahmed et al. (Reference Ahmed, Buckley, Stratton, Asefaha, Butler, Reynolds and Orians2017) successfully grew culinary herbs, such as silver thyme (Thymus argenteus), Moroccan mint (Mentha spicata), and Italian oregano (Organum majoricum) on EGRs with limited supplemental irrigation, concluding that they are suitable for growing on EGRs. These herbs are all native to the Mediterranean, which has a dry climate similar to conditions found on EGRs (Van Mechelen, Dutoit and Hermy, Reference Van Mechelen, Dutoit and Hermy2014). Food production of other crops, including fruits and vegetables such as beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), cucumber (Cucumis sativus), pepper (Capsicum annuum), basil (Ocimum basilicum), and chive (Allium schoenoprasum), is possible on EGRs with ample irrigation and minimal fertilization (Whittinghill, Rowe and Cregg, Reference Whittinghill, Rowe and Cregg2013). Yet a major limiting factor to the functioning of EGRs is water availability.

To minimize supplemental irrigation while maximizing the ecosystem functioning of plant communities on EGRs, researchers have turned to ecological theory to inform how plant selection might lead to better-functioning EGRs (Lundholm and Williams, Reference Lundholm, Williams and Sutton2015; Blaustein, Kadas and Gurevitch, Reference Blaustein, Kadas and Gurevitch2016; Lundholm and Walker, Reference Lundholm and Walker2018). Plant facilitation is one such vital mechanism from the ecological sciences that draws on plant diversity to maintain the function of plant communities (Callaway, Reference Callaway2007). Much of what is known about plant–plant facilitation in natural and seminatural environments has been framed by the stress-gradient hypothesis (SGH) (Lortie and Callaway, Reference Lortie and Callaway2006; Callaway, Reference Callaway2007; Maestre et al., Reference Maestre, Callaway, Valladares and Lortie2009). The SGH states that the benefits of stress amelioration by neighbors relative to the negative effects of competition increase as stress levels increase (Bertness and Callaway, Reference Bertness and Callaway1994). Such facilitative interactions between plants are vital for improving plant survival on EGRs (Butler and Orians, Reference Butler and Orians2011; Vasl et al., Reference Vasl, Shalom, Kadas and Blaustein2017; Rolhauser et al., Reference Rolhauser, MacIvor, Roberto, Ahmed and Isaac2023). Facilitative interactions through companion planting have been widely used in agriculture. Examples include maize and bean intercropping, where maize provides a structural support for beans to grow (Zhang and Li, Reference Zhang and Li2003). Soybean and wheat intercropping has been used to promote root complementarity and new sources of nitrogen (Nimmo et al., Reference Nimmo, Violle, Entz, Rolhauser and Isaac2023). Intercropping deep-rooting woody shrubs with grain is known to improve water availability in arid regions (Bogie et al., Reference Bogie, Bayala, Diedhiou, Dick and Ghezzehei2019). Companion planting wildflowers with strawberry promotes pollinator visitation and increases yield and fruit quality (Griffiths-Lee, Nicholls and Goulson, Reference Griffiths-Lee, Nicholls and Goulson2020). In addition, planting species of geranium has been done to reduce pest pressure of aphids on pepper plants (Ameline et al., Reference Ameline, Dorland, Werrie, Couty, Fauconnier, Lateur and Doury2023).

Although facilitation exerted by stress-tolerant species (e.g., Sedum) has been proposed to improve the performance of stress-intolerant species (crops) in EGRs (Rolhauser et al., Reference Rolhauser, MacIvor, Roberto, Ahmed and Isaac2023), the conditions under which facilitation could occur are not well understood. Sedum has been shown to act as a nurse plant, reducing the severity of an environment for another species’ survival (Bertness and Callaway, Reference Bertness and Callaway1994; Young, Cameron and Phoenix, Reference Young, Cameron and Phoenix2017). During water-stressed conditions, Sedum has been shown to facilitate native wildflower performance (plant cover and survival) on green roofs by creating cooler soil temperatures (Butler and Orians, Reference Butler and Orians2011). Several studies reported that Sedum help neighboring plants not to wilt when experiencing drought conditions (Nagase and Dunnett, Reference Nagase and Dunnett2010; Matsuoka et al., Reference Matsuoka, Tsuchiya, Yamada, Lundholm and Okuro2019). Substrate water holding capacity and moisture retention have been shown to be higher when plants are grown with Sedum on green roofs (Vasl et al., Reference Vasl, Shalom, Kadas and Blaustein2017), resulting in less leaf wilt on neighboring plants (Matsuoka et al., Reference Matsuoka, Tsuchiya, Yamada, Lundholm and Okuro2020). In contrast, one study specifically showed competitive interactions of Sedum and neighboring plants on an EGR. Butler and Orians (Reference Butler and Orians2011) observed a reduction in the maximum growth of wildflower plants when grown with Sedum in wet conditions, showing signs of competition when water resources are not limited. This is likely due to the shallow root structure of Sedum, which is distributed throughout the substrate to optimal water uptake when water is available (Van Wijk and Bouten, Reference Van Wijk and Bouten2001; Craine and Dybzinski, Reference Craine and Dybzinski2013).

These facilitative interactions could occur in numerous ways. Sedum can help shade seedlings during critical early growth, ameliorating elevated soil temperatures and solar exposure, and impacting perennial herbs and shrubs in EGR shading studies (Aguiar, Robinson and French, Reference Aguiar, Robinson and French2019). Sedum can contribute to higher soil moisture and thus facilitate leaf retention (Butler and Orians, Reference Butler and Orians2011) through its photosynthetic plasticity and minimal evapotranspiration (Gravatt and Martin, Reference Gravatt and Martin1992). The intercropping of Sedum with crops may promote root plasticity and spatial root distribution, thus increasing root density and accessing more nutrients, promoting better growth often observed in other intercropping systems (Li et al., Reference Li, Sun, Zhang, Guo, Bao, Smith and Smith2006). The presence of Sedum may promote acquisitive root traits in neighboring crops, such as finer root diameter, to encourage uptake of water and nutrients, as seen with millet roots intercropped with peanut (Zou et al., Reference Zou, Li, Sun, Sun, Yang, Shiwei, Liu, Xu and Tan2019).

While we have general hypotheses on plant interactions in stressful environments, most of this evidence focuses on aboveground interactions and among wild plants. If we are to transition EGRs into crop production, understanding nurse plant interactions from a belowground perspective and with food-producing species is imperative. In this study, we determine the facilitative effects of Sedum on crop performance in EGRs using 48 EGR modules with bean (P. vulgaris) in monoculture or planted with Sedum, plus an artificial Sedum treatment. We also applied two watering levels to induce stressful conditions within these planting designs. We hypothesize that (1) beans planted with Sedum will outperform beans in monoculture under water limitations due to nurse effects by Sedum, (2) bean roots will express higher acquisitive traits when planted with Sedum to achieve this facilitation, and (3) bean root traits will display higher plasticity than Sedum roots under low water availability, given the adaptation of Sedum to low water environments.

Methods

Study site and design

The study was conducted in the summer of 2021 at the University of Toronto Scarborough green roof testing facilities on the Highland Hall building. In this study, 48 green roof modules (40 cm × 60 cm; Vegetal i.D, FR) were installed with 12 treatment combinations (four replicates per treatment) in an additive design (Fig. 1). Modules were spaced at least 60 cm apart from each other to avoid interactions between them. Each module was lined with landscaping fabric to allow for water drainage and reduce substrate loss. An organic substrate media consisting of a 25% w/w organic green waste matter and crushed aggregate (‘EcoBlend’ Bioroof Systems, CAN) was filled to the top of each module to a depth of 10 cm.

Figure 1. (a) Planting layout and treatment design of green roof modules with (b) example images of all planting design treatments.

Modules were planted in three planting designs: (i) living Sedum, (ii) an artificial plastic Sedum (Ashland, USA) of similar size to control for the aboveground effect of shading by the plants but without the transpirative cooling ability and belowground interactions of a live plant (Aguiar, Robinson and French, Reference Aguiar, Robinson and French2019), or (iii) no Sedum. The planting design is shown in Fig. 1. In modules receiving a live Sedum treatment, two rows of six plugs of two species, S. album L. and S. sexangulare L., were alternated along the long axis of the module, dividing the planting area into thirds. In modules receiving an artificial Sedum treatment, two rows of artificial plants were positioned corresponding to the live Sedum rows in modules receiving artificial Sedum treatments, and control modules were left empty. All three planting designs were planted with Contender bush beans (P. vulgaris L.) from seed. Each module was planted with a single central row of four seeds at a depth of 1 cm and spaced 15 cm apart along the long axis.

Water was provided every second day for the first 2 weeks after planting to promote germination. Two watering levels were implemented in the design thereafter, with a low-watering treatment maintaining substrate moisture between 12% and 35% (approximately 1.5 L per watering event) and high-watering treatment maintaining substrate moisture above 35% (approximately 3 L per watering event). This was maintained by checking soil moisture on five randomly selected modules per watering treatment per day, calculating an average soil moisture and applying the watering treatment once soil moisture approached the lower threshold.

Above- and belowground sampling

Bean leaf traits were assessed in late August during bean ripening in each module. Leaf photosynthesis (A sat, μmol CO2 m−2 s−1), instantaneous water use efficiency (IWUE, mmol CO2 mol−1 H2O), and chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm) on an area basis were measured using a LI-COR 6800 portable gas analyzer and fluorometer (LI-COR Biosciences, USA). One mature leaf was sampled from the middle of the same plant following photosynthesis measurements to determine leaf area (LA, mm2) using image analysis with ImageJ (Schneider, Rasband and Eliceiri, Reference Schneider, Rasband and Eliceiri2012). The leaf was then dried and weighed, and specific leaf area was calculated (SLA, mm2 mg−1). The entire aboveground portion of the plant was then harvested, separated into shoot biomass and yield (fruit and seed), and dried at 65 °C in a drying oven (Fisher Scientific, USA) for a minimum of 48 hours to determine total biomass (g).

The entire root system from the harvested plant was carefully excavated and collected. The roots were rinsed and scanned using a flatbed scanner, dried and weighed at 65 °C for a minimum 48 hours for biomass. Root diameter (RD, mm), specific root length (SRL, mm g−1), specific root area (SRA, mm2 g−1), and tip density (TD, g−1) using WinRhizo (Regents Instruments, CA) and root weights were determined.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R v. 4.3.2 (R Core Team, 2023). Plant, leaf, and root trait measurements were all tested for normality using Shapiro–Wilk tests, and traits were log-transformed if best described by log-normal distributions. The differences in plant design (no Sedum, artificial Sedum, and live Sedum) and water availability (low, high) for these traits were analyzed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with F-values, p-values, and partial eta-squared effect sizes (ηp 2) reported. Tukey’s post hoc tests were performed for traits with significant p-values, and the mean values of these traits were visualized using boxplots.

Functional trait hypervolumes were constructed using the ‘hypervolume’ R package and a Gaussian kernel density estimate (Blonder et al., Reference Blonder, Morrow, Maitner, Harris, Lamanna, Violle, Enquist and Kerkhoff2018). Hypervolumes depict the observed plant trait space. The occupied volume of the plant trait indicates its niche, where overlap in trait space of species indicates complete sharing of trait space, while areas of spillover represent trait plasticity. Four-dimensional hypervolumes were created for beans and Sedum in both water availability treatments. Data were standardized using z-transformation to compare axes with different units. Hypervolumes included root traits (SRL, SRA, RD, and TD). These traits were selected as they are responsive to soil environmental factors, specifically water availability (Wasson et al., Reference Wasson, Richards, Chatrath, Misra, Prcsad, Rebetzke, Kirkegaard, Christopher and Watt2012; Bao et al., Reference Bao, Aggarwal, Robbins, Sturrock, Thompson, Tan, Tham, Duan, Rodriguez, Vernoux, Mooney, Bennett and Dinneny2014; Forde, Reference Forde2014).

Results

Treatment effects on crop performance

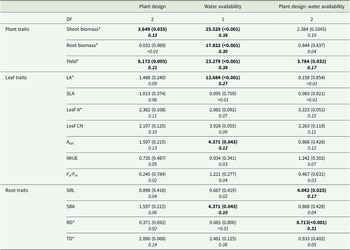

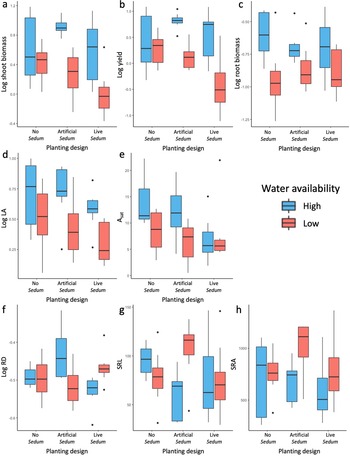

Two-way ANOVA results for bean functional traits are summarized in Table 1, and Tukey’s post hoc tests (TukeyHSD) can be found in Supplementary Table 3. Shoot biomass was significantly influenced by both plant design (Table 1; p = 0.035; ηp 2 = 0.15) and water availability (Table 1; p < 0.001; ηp 2 = 0.38). Bean shoot biomass was the greatest when grown in the artificial Sedum planting treatment with high water availability (Fig. 2a) and significantly greater than all low water availability planting designs (Supplementary Table 3; No p = 0.041; Artificial p = 0.003; Live p < 0.001), while bean shoot biomass was the lowest when grown in live Sedum with low water availability and significantly lower than all other treatments except Artificial:Low (Supplementary Table 3; No:High p = 0.007; Artificial:High p < 0.001; Live:High p = 0.012; No:Low p = 0.013). Yield also was significantly influenced by plant design (Table 1; p = 0.005; ηp 2 = 0.21) and water availability (Table 1; p < 0.001; ηp 2 = 0.38), as well as for the interaction plant design: water availability (Table 1; p = 0.032; ηp 2 = 0.17). Similar to shoot biomass, yield for high-watering treatments increased in the artificial Sedum planting effect compared with the other effects. This was significantly greater than the Artificial Sedum (Supplementary Table 3; p = 0.035) and live Sedum (Supplementary Table 3; p < 0.001) under low water availability. A decrease in yield was observed when grown with live Sedum and low watering, and was also significantly lower than all other treatments except Artificial:Low (Supplementary Table 3; No:High p = 0.003; Artificial:High p < 0.001; Live:High p < 0.001; No:Low p = 0.014). Overall, yield was greater in the high-watering treatments, specifically with both planting treatments (Fig. 2b). Root biomass was only significantly influenced by water availability (Table 1; p < 0.001; ηp 2 = 0.30), where in all planting designs, beans grown with high-watering treatments had greater root biomass (Fig. 2c).

Table 1. Analysis of variance results for plant, leaf, and root traits of bush beans under planting designs (no Sedum, artificial Sedum, and live Sedum planting effects) and water availability levels (high and low water availability)

Note: F-values are reported with p-values in parentheses, and partial eta-squared effect sizes (ηp 2) are italicized. Bold text denotes significance. Traits marked with asterisks are log-transformed for normality. Tukey’s post hoc tests for significant traits are reported in Supplementary Table 3.

Figure 2. Boxplots of bean traits with planting design (no Sedum, artificial Sedum, and live Sedum) and water availability (high and low water availability). Traits include (a) shoot biomass (g), (b) yield (g), (c) root biomass (g), (d) LA (mm2), (e) A sat (μmol CO2 m−2 s−1), (f) RD (mm), (g) SRL (mm g−1), and (h) SRA (mm2 g−1).

Treatment effects on leaf functional traits

Two leaf functional traits, LA and A sat, were significantly different based on water availability (Table 1; LA: p = 0.001; ηp 2 = 0.27; A sat p = 0.043; ηp 2 = 0.12). LA increased with greater watering in all plant designs (Fig. 2d). A sat was also greater overall in high-watering treatments, specifically in beans with no Sedum or artificial Sedum (Fig. 2e). Planting design and planting design:water availability were not significantly influenced for all seven leaf traits (LA, SLA, Lean N, Leaf CN, A sat, IWUE, and Fv/Fm).

Treatment effects on root traits

Water availability significantly influenced SRA (Table 1; p = 0.043; ηp 2 = 0.10). In low-watering treatments, SRA increased with the artificial and live Sedum planting effects (Fig. 2h). Planting design:water availability significantly influenced SRL (Table 1; p = 0.025; ηp 2 = 0.17) and RD (Table 1; p < 0.001; ηp 2 = 0.31). SRL of beans planted with the artificial Sedum treatment showed an increase compared with other planting designs when in the low-watering treatment and decreased when high watering (Fig. 2g). RD was greater in beans planted with the artificial Sedum treatment when receiving higher watering and significantly greater than beans planted with live Sedum with high water availability (Supplementary Table 3; p = 0.008), but beans planted with the live Sedum treatment had increased RD with lower water availability (Fig. 2f). No treatment significantly influenced TD.

Root trait hypervolumes

We used four-dimensional trait hypervolume analysis to visualize root trait space for beans intercropped with Sedum in high-watering treatments (Fig. 3a) and low-watering treatments (Fig. 3b). In both treatments, beans had larger hypervolumes than Sedum (high watering: Beans = 367.51; Sedum = 20.06; low watering: Beans = 432.09; Sedum = 106.03), with Sedum hypervolumes being more constrained in the high-watering treatment. The bean trait space almost fully encompassed the Sedum trait space for all four root traits, with much less internal overlap in the high-watering treatment.

Figure 3. Root trait hypervolume for multiple bivariate functional trait axes (log RD, SRA, SRL, and log TD) for Sedum (orange) and beans (green) with (a) high water availability and (b) low water availability. Larger points correspond to observations in bivariate trait space, whereas the solid lines represent boundaries of the two-dimensional hypervolume trait space, estimated using a Gaussian kernel density.

Discussion

Water availability overrides planting design

Across all measures of performance and leaf traits, plant response was controlled by low water conditions more than planting conditions. Average soil moisture was 21.8% for modules receiving the low water availability treatment and 40.3% for modules receiving the high water availability treatment (Supplementary Table 5). We show that regardless of whether beans are grown alone (no Sedum), with only aboveground influences of a companion (artificial Sedum) or with live Sedum, bean leaf physiological responses were suppressed with lower water availability, rejecting our first hypothesis. Beans are one of the most sensitive legumes to water stress (Toaldo et al., Reference Toaldo, de Morais, Battilana, Coimbra and Guidolin2013), and it is detrimental to their biomass and yield (Campos et al., Reference Campos, Schwember, Machado, Ozores-Hampton and Gil2021). While we draw on facilitative mechanisms in various intercropping scenarios to underpin our hypotheses on Sedum–crop interactions, it may be that the adaptation of Sedum to dry conditions provided was advantageous, and therefore the beneficial effects of the presence of Sedum on, for instance, substrate cover and lower evapotranspiration were overshadowed by Sedum growth and competitive advantage under low water availability. We note that for most aboveground measures, there is little difference in bean performance with and without Sedum, suggesting that competitive effects of Sedum are minimized when substrate water is not limited.

Water availability affects root traits more than leaf traits

We show that bean response is driven by the presence of Sedum roots when in low-watering environments. Under high water conditions, we see little impact of aboveground or both aboveground and belowground interactions on root traits. However, under low water conditions, we see differences, with sometimes opposing but significant interactions. Unlike classic soil environments where resources are heterogeneously distributed within a complex soil matrix, green roofs may offer a more homogeneous resource distribution, given the more confined space, which has consequences for the expression of foraging and morphological root traits and should be further studied. Differences in root architecture drive water acquisition and plant productivity in water-stressed conditions (Vadez et al., Reference Vadez, Rao, Kholova, Krishnamurthy, Kashiwagi, Ratnakumar, Sharma, Bhatnagar-Mathur and Basu2008). Increased root length, root length density, and rooting depth are all traits shown to improve drought tolerance in beans and improve yield (Beebe et al., Reference Beebe, Rao, Cajiao and Grajales2008). Water stress also encourages root tip density and a decrease in root diameter (Salazar-Henao, Vélez-Bermúdez and Schmidt, Reference Salazar-Henao, Vélez-Bermúdez and Schmidt2016), which is thought to increase water acquisition from the soil. Ramamoorthy et al. (Reference Ramamoorthy, Lakshmanan, Upadhyaya, Vadez and Varshney2017) showed an increase in root length and decreased root diameter in legumes under water stress in a field-based study, inconsistent with the results we found. Although the study environment differs, this highlights the need for green roof resource distribution to be studied.

Notably, we show that beans grown with artificial Sedum, therefore with only aboveground interactions, showed higher crop performance compared with live Sedum, as well as strong root trait responses, with acquisitive traits such as specific root area and length increasing under low water availability, as hypothesized. Likely, bean plants are thriving with artificial Sedum as there is no root competition from both Sedum and neighboring bean plants, as well as additional available water that would otherwise be taken up by Sedum that could be contributing to a cooler microclimate. This result can also be attributed to changes in red to far-red light ratios (R:FR) reflected from the live versus artificial Sedum. Changes in R:FR can be detected in plants that initiate a photoreceptive response to avoid competition from neighboring plants, causing stem elongation to avoid shading that potentially has irreversible consequences impacting response to environmental stressors later in life (Weinig and Delph, Reference Weinig and Delph2001). Schambow et al. (Reference Schambow, Adjesiwor, Lorent and Kniss2019) showed that plants were not impacted by the R:FR of plastic mulches, regardless of their color, but had reduced leaf area and leaf biomass when exposed to R:FR of live plants. Although R:FR was not measured in our study, these observations are supported by our findings and could indicate a competitive interaction between beans and live Sedum and a lack of competition between beans and artificial Sedum.

Leaf traits did not show any effects on water availability. Since these traits are established indicators of plant water status and photosynthetic performance, we attribute these findings to the highly unstable environmental conditions on the green roof, notably the intense wind gusts cycling in varying temperatures of humid air, disrupting the measurements. Although we did not find strong effects of water availability on leaf traits, severe drought is known to impact photosynthesis in legumes, impacting growth and development (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Pan, Zhang, Luo and Ji2018). Hao et al. (Reference Hao, Li, Feng, Han, Gao, Lin and Han2013) reported a reduction in chlorophyll content in water-stressed soybeans. Fava bean also showed reduced chlorophyll content, photosynthetic rate, and decreased growth and yield (Siddiqui et al., Reference Siddiqui, Al-Khaishany, Al-Qutami, Al-Whaibi, Grover, Ali, Al-Wahibi and Bukhari2015). Abid et al. (Reference Abid, M’hamdi, Mingeot, Aouida, Aroua, Muhovski, Sassi, Souissi, Mannai and Jebara2017) also report negative effects on chlorophyll fluorescence in water-stressed fava. Updating methodological protocols for measuring leaf physiological traits for highly variable environmental conditions on green roofs is needed to make any further inferences on relationships with water stress.

Bean roots display higher trait plasticity, while Sedum roots are more constrained

Through hypervolume analyses, we show that beans have higher root trait plasticity than Sedum when companion-planted, supporting our hypothesis. Beans occupy a larger amount of trait space compared with Sedum, suggesting that crops can potentially change their strategies to survive in less favorable conditions. Riyaz et al. (Reference Riyaz, Shafi, Zaffar, Wani, Zargar, Djanaguiraman, Prasad and Sofi2024) found that spatial plasticity of root traits of common beans influenced yield under drought stress, and that increased root diameter and surface area were major drivers to help plants capture water during drought. This is supported by our findings, as similar trends were seen with decreases in bean yield and positive changes in plasticity (increase) of SRA with low water availability. Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Sun, Su, Du, Bai, Wang, Wang, Nie, Sun, Feng, Zhang, Yang, Zhang, Evers, van der Werf and Zhang2022) determined that legumes invest more into roots than shoots when intercropped with maize, and root plasticity in terms of the ratio of root length density to shoot biomass produced was greater by 76% when intercropped versus alone. A similar investment strategy in root biomass over the shoot biomass when intercropped is also reported in our low water availability treatment. Although our study does not report on plasticity differences between intercropped and monoculture, we see a large root trait space occupancy in both watering availability treatments by beans, suggesting that plasticity is retained. Ajal et al. (Reference Ajal, Jack, Vico and Weih2021) and Nimmo et al. (Reference Nimmo, Violle, Entz, Rolhauser and Isaac2023) show that legume root trait space, observed through hypervolume analysis, shows minimal overlap with companion species, even under a range of soil amendment regimes, suggesting root trait coordination across a range of conditions. We report similar findings, as the bean trait space is much larger than Sedum.

Sedum hypervolume was 5.46% of the total volume of beans when water availability was high, and hypervolume size increased to 24.54% of bean volume with low water availability. Sedum hypervolume increased by 428.56% from high to low water availability, while bean increased by 17.57%. The reduction in Sedum trait space when water is highly available suggests weaker plasticity and conservative root traits. This is supported by Ji et al. (Reference Ji, Sæbø, Stovin and Hanslin2018), who found a greater proportion of root length in substrates with higher watering, interpreted as a weakening of foraging capabilities of Sedum roots when high water resources are available. Root plasticity in intercropping is a result of soil water availability (Li et al., Reference Li, Sun, Zhang, Guo, Bao, Smith and Smith2006). In the same study by Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Sun, Su, Du, Bai, Wang, Wang, Nie, Sun, Feng, Zhang, Yang, Zhang, Evers, van der Werf and Zhang2022), intercropped legumes consumed more water in the reproductive stage than legumes grown in monoculture when soil moisture was limited, while their companion plant, maize, consumed more water in the vegetative stage, suggesting temporal complementarity in water use. Though we do not measure water consumption during different life stages of beans and Sedum, these findings do not support our suggestion of competition for water resources in low water availability conditions.

While the facilitative interactions we studied were not strong enough to overcome the environmental conditions, there are other mechanisms that may be more important to bean productivity on green roofs, such as nitrogen availability. Water stress negatively impacts nitrogenase activity in legume nodules (Sprent, Reference Sprent1972; Albrecht, Bennett and Boote, Reference Albrecht, Bennett and Boote1984), impacting legume growth. While companion planting may alleviate some of the negative effects of water stress, this is not sufficient to overcome decreased nitrogenase activity, as nodule nitrogen fixation is highly sensitive to drought and results in decreased nitrogen accumulation and crop yield (Serraj, Sinclair and Purcell, Reference Serraj, Sinclair and Purcell1999). Martin et al. (Reference Martin, Hayes, Borden, Buchanan, Gordon, Isaac and Thevathasan2019) show an increase in legume nodulation and nodule mass with increasing soil moisture. This relationship is likely due to hydrated nodules having a greater O2 diffusion potential and boosting the mobilization of atmospheric nitrogen to bioavailable forms (Fleurat-Lessard et al., Reference Fleurat-Lessard, Michonneau, Maeshima, Drevon and Serraj2005) or reduced feedback inhibition of N2-fixation from greater shoot growth in water sufficient conditions (Streeter, Reference Streeter2003). Since the aggregate size of the FLL substrate used in this study is similar to that of natural soil used for legume planting, it is likely that these impacts of soil oxygenation on nitrogenase activity are occurring. Similarly, soil fungi are known to benefit green roof ecosystems, though these systems generally lack inoculum (John, Lundholm and Kernaghan, Reference John, Lundholm and Kernaghan2014, Reference John, Kernaghan and Lundholm2017). Mycorrhizal fungi increase plant access to soil nutrients, especially under water-stressed conditions (Veresoglou, Chen and Rillig, Reference Veresoglou, Chen and Rillig2012), allowing better growth. More research is needed on soil fungal communities on EGRs as a pathway to enhance crop performance in stressed environments (Fulthorpe et al., Reference Fulthorpe, MacIvor, Jia and Yasui2018).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that water availability is the primary driver of crop performance and root trait expression on EGRs, overriding potential facilitative effects from companion planting with Sedum. While studies typically predict positive interactions between plants under stress, our findings indicate that under water-limited conditions on EGRs, nurse plants may compete with rather than facilitate crop performance. We also show that crops exhibit greater root trait plasticity, adjusting their morphology in response to water stress and neighboring plant presence.

We disentangle scenarios for facilitative planting on EGRs and show the ability to test and find patterns of water stress in crops. While the plant interactions studied did not provide evidence of facilitation to enhance crop performance within the variable conditions of EGRs, looking to other methods to overcome high environmental stress, such as nutrient addition and inoculation of mycorrhizal fungi, is needed to help expand food production on EGRs.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170525100197.

Disclosure of use of AI tools

The authors have not used any generative AI tools in the research and writing process.

Data availability statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within this paper and its online supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Andrew Nichols, Gabby Simard, Thanuka Sivanathan, Isabelle Aquino, and Darren Suthananthan for their help with the field and lab work.

Funding statement

This research was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Collaborative Research and Training Experience (NSERC CREATE #401276521) program grant awarded to M.E.I. and J.S.M. through project lead Jennifer Drake, as well as the Sustainable Food and Farming Futures cluster grant awarded to M.E.I.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests to disclose.

Ethical standard

All best practices and ethical standards have been met through the research design, execution, and adhere to the legal requirements of the research institution.