Globally, the genus Astragalus comprises 3,082 recognized species (POWO, 2025), most of which are adapted to arid and semi-arid environments (Scherson & Podlech, Reference Podlech2008; Khassanov, Reference Khassanov, Shomuradov and Kadyrov2011). A significant number of Astragalus species are rare or threatened and require dedicated conservation (Maassoumi & Ashouri, Reference Maassoumi and Ashouri2022; Castillon, Reference Castillon, Quintanilla, Delgado-Salinas and Rebman2023). To date, only 149 species of Astragalus (c. 4%) have been assessed for the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN, 2024), with c. 36% of these categorized as threatened (i.e. Critically Endangered, Endangered or Vulnerable) and one (Astragalus nitidiflorus Jiménez & Pau) as Extinct in the Wild (Sánchez Gómez et al., Reference Sánchez Gómez, Carrión Vilches and Galicia Herbada2006). In Uzbekistan, 32 species of Astragalus have been recorded in the National Red Book (Khassanov et al., Reference Khassanov, Kuchkarov, Tozhibaev, Pratov, Belolipov and Shomurodov2019), and it is the genus with the greatest number of species listed in the country’s conservation registry.

The mountains of the Kyzylkum Desert harbour a total of 30 endemic plant species, including Astragalus spp., and are a centre of plant endemism in Central Asia (Turginov, Reference Turginov2024). These low mountains (700–1,000 m altitude) form the western extension of the central mountain belt of Central Asia (Fig. 1; Shomurodov, Reference Shomurodov2018). The distinctive edaphic, climatic and biogeographical conditions determine the floristic assemblages of these mountains. Of the 42 species of Astragalus in this region (Khassanov, Reference Khassanov, Shomuradov and Kadyrov2011), six are endemic (A. adylovii F.O.Khass., Ergashev & Kadyrov, A. centralis Sheld., A. holargyreus Bunge, A. kuldzhuktauense F.O.Khass., Shomuradov & Esankulov, A. remanens Nabiev and A. subbijugus Ledeb.).

Fig. 1 The mountains of the Kyzylkum Desert, Uzbekistan, showing the distribution of Astragalus centralis on the northern slope of the Tamditau (Aktau) mountains.

Astragalus centralis is a perennial that grows to 10–15 cm high, with white-haired stems and 1–2-jugated leaves, with dense inflorescences of yellow flowers produced annually. During 2007–2016, we studied the status of A. centralis in the Kuldzhuktau mountains of the Kyzylkum Desert, which was considered to host the species’ largest population (Saribaeva, Reference Saribaeva2009; Saribaeva & Shomurodov, Reference Saribaeva and Shomurodov2017). However, subsequent research in 2016 revealed that the subpopulations in the Kuldzhuktau and Auminzatau mountains were a distinct species, now described as A. kuldzhuktauense (Khassanov et al., Reference Khassanov, Shomuradov and Esankulov2016). Revised consideration of the distribution and conservation of A. centralis was therefore required. We subsequently carried out the first monitoring of the only known population of A. centralis, in the Tamditau (Aktau) range, in 2016–2017 (Shomurodov, Reference Shomurodov2018). Monitoring continued in 2018–2019 (Tojibaev et al., Reference Tojibaev, Beshko, Shomurodov, Abduraimova, Adilova and Akhmedova2019) and 2023–2024. In all three monitoring periods (2016–2017, 2018–2019, 2023–2024) we carried out a complete census at the peak of flowering, using equal effort in each period.

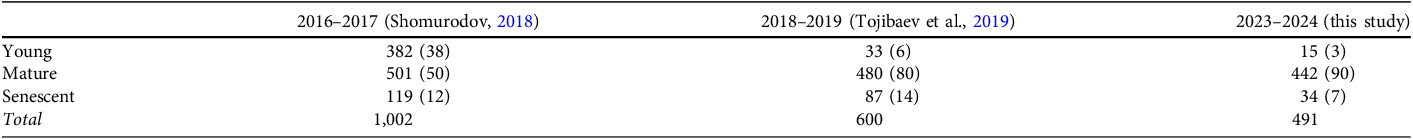

We can now confirm that A. centralis, which has not previously been assessed for the IUCN Red List, is endemic to Uzbekistan, restricted to a single, isolated population on the northern slope of the Tamditau mountains (Plate 1), where it grows in rock crevices among large boulders on limestone and rocky soils, and in gravelly habitats, in an area of c. 6 ha. In 2016–2017, the population comprised c. 1,000 individuals, the majority of which were mature (reproductive) individuals. By 2018–2019 the population had declined to c. 600 individuals, with an increased per cent of mature individuals and a reduced per cent of young (non-reproductive) individuals. In 2023–2024 we counted 491 individuals, with a further increase in the per cent of mature individuals and decrease in the per cent of young individuals (Table 1), considerably lower than the number reported in the national Red Book (c. 1,200 individuals; Khassanov et al., Reference Khassanov, Kuchkarov, Tozhibaev, Pratov, Belolipov and Shomurodov2019).

Plate 1 (a) Characteristic habitat of Astragalus centralis, endemic to the Tamditau (Aktau) mountains (Fig. 1), (b) the species in its habitat, and (c) detail of inflorescence. Photos: Khabibullo Shomurodov.

Table 1 Number (and per cent) of young, mature and senescent individuals of the only known population of Astragalus centralis, in the Tamditau mountains in the Kyzylkum Desert of Uzbekistan (Fig. 1), recorded during three monitoring periods.

This small population is exposed to a number of potential threats. Limestone is extracted in this region, and we have observed an increase in the number of excavation trenches, with the species’ habitat being progressively lost. In addition, the population is located near the Tamdi settlement, where the local economy primarily relies on livestock farming. The area is used year-round as pastureland, and grazing and trampling by livestock pose a significant threat to A. centralis. Climate change-induced droughts during the vegetative period may potentially have a negative effect, similar to effects we have observed on A. kuldzhuktauense. Additionally, seed predation by insects has been reported to occur more commonly in dry years (Saribaeva, Reference Saribaeva2009). Climate anomalies and extreme weather events observed over the past decade potentially further exacerbate these threats (Khabibullaev et al., Reference Khabibullaev, Shomurodov and Adilov2022). We have observed that spring flash floods, which are increasing in frequency and intensity, destroy young seedlings that have not yet firmly established their roots in rocky substrates. Moreover, unseasonal short-term cold anticyclones, occurring every 5–6 years (Fenu, et al., Reference Fenu, Cambria, Giacò, Khabibullaev, Shomurodov and Peruzzi2023a; Khaitov, Reference Khaitov2024), have a disproportionately negative impact on the most vulnerable stages, the young and senescent individuals.

Our monitoring indicates that A. centralis is losing the ability to self-sustain because of insufficient recruitment and/or low survival rate of young plants, resulting in a demographic shift to mature individuals. Considering that the species is restricted to a single, small and isolated population dominated by mature individuals, its habitat is under continuous threat, and the identified drivers of population decline remain unmitigated and are expected to persist, we recommend that A. centralis is categorized as Critically Endangered based on IUCN Red List criteria (IUCN, 2012) B1ab(i,ii,iii,v)+2ab(i,ii,iii,v); i.e. extent of occurrence (EOO; B1) is < 100 km2 and area of occupancy (AOO; B2) is < 10 km² (both are < 4 km²), only one population of the species is known (a), and a continuous decline (b) has been observed in EOO (i), AOO (ii), habitat quality (iii) and number of mature individuals (v).

To ensure the survival of A. centralis, we make the following recommendations: (1) Designate its restricted habitat as a protected area (the area also harbours other species listed in the National Red Data Book, including Ferula kyzylkumica Korovin, Lagochilus vvedenskyi Kamelin & Tzukerv., Lappula aktaviensis Popov & Zakirov, Lepidium subcordatum Botsch. & Vved., Silene tomentella Schischk and Stipa aktauensis Roshev), classify the Tamditau mountains as a significant national ecosystem and assess the area for potential inclusion in the Red List of Ecosystems. (2) Inventory pasture resources, to determine sustainable grazing capacities and regulate livestock grazing, and thus reduce pressure on the population. (3) Consider translocation as a strategy for restoring and stabilizing the population (Fenu et al. Reference Fenu, Calderisi, Boršić, Kharrat, Fernández and Kahale2023b), using species distribution modelling to identify suitable areas. (4) Develop ex situ propagation at the Kyzylkum Desert Experimental Station, and collect seed for curation in an appropriate seed bank. (5) Include the species on the IUCN Red List, and conduct awareness campaigns and promote conservation initiatives for its protection.

Rare and endemic plants at significant risk may be overlooked as a result of outdated taxonomy and/or a lack of knowledge of their distribution and conservation status. As recently demonstrated for other plant species (e.g. Abeli et al., Reference Abeli, Müller and Seidel2024; Fenu et al., Reference Fenu, Calderisi and Cogoni2024; Li et al., Reference Li, Tang and Wang2024), conservation needs may shift significantly as knowledge of the ecology of a species improves. This study provides a basis for the conservation of A. centralis and reaffirms the importance of taxonomic reassessments in conservation.

Author contributions

Study design: BK; fieldwork: all authors; data analysis: KSH; writing and revision: all authors.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted within the framework of the state programme Digital Nature, implemented by the Institute of Botany of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Grant No. PRIM 01-73 The modernization of the Institute of Botany of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan, funded under the MUNIS Project supported by the World Bank and the Government of the Republic of Uzbekistan. We thank our colleagues and institutions who provided invaluable support in data collection, analysis and interpretation, and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive critiques.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.