Introduction

Common lambsquarters (Chenopodium album L.) is a summer annual, broadleaf weed with a global distribution, commonly infesting crops such as corn (Zea mays L.) (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Harvey, Bauman, Phillips, Hart, Johnson, Kells, Westra and Lindquist2004), various types of beans (Hekmat et al. Reference Hekmat, Soltani, Shropshire and Sikkema2008; Li et al. Reference Li, Van Acker, Robinson, Soltani and Sikkema2017; Odero and Wright Reference Odero and Wright2018; Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Feist, Eskelsen, Scott and Knezevic2017; Pavlovic et al. Reference Pavlovic, Colquhoun, Korres, Liu, Lowry, Peachey, Scott, Sosnoskie, VanGessel and Williams2024), wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) (Salonen et al. Reference Salonen, Niemi, Haavisto and Juvonen2022), and vegetables (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, White and Mckenzie-Gopsill2023; Odero and Wright Reference Odero and Wright2022; Tang et al. Reference Tang, Guo, Yin, Ding, Xu, Wang, Yang, Xiong, Zhong, Tao and Sun2022). It is particularly competitive during the early growth stages of spring-seeded crops, often causing substantial yield losses (Crook and Renner Reference Crook and Renner1990). It is one of the species commonly found infesting lima and snap bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) fields in the U.S. Northwest, Midwest, and Northeast (Pavlovic et al. Reference Pavlovic, Colquhoun, Korres, Liu, Lowry, Peachey, Scott, Sosnoskie, VanGessel and Williams2025; Takenata et al. Reference Takenaka, Pavlovic, VanGessel, Scott, Colquhoun and Williams2025). Even low levels of infestation can lead to weed parts being harvested with the crop, and their removal during processing is often difficult and costly (Pavlovic et al. Reference Pavlovic, Colquhoun, Korres, Liu, Lowry, Peachey, Scott, Sosnoskie, VanGessel and Williams2025). Its widespread occurrence is largely due to its ability to thrive under a broad range of environmental conditions (Tang et al. Reference Tang, Guo, Yin, Ding, Xu, Wang, Yang, Xiong, Zhong, Tao and Sun2022), rapid growth, and prolific seed production, as well as the longevity and viability of its seeds in the soil seedbank (reviewed by Bajwa et al. Reference Bajwa, Zulfiqar, Sadia, Bhowmik and Chauhan2019).

The ecological success of species in the Chenopodium genus is largely attributed to their phenotypic plasticity, enabling adaptation to diverse environments. For example, Li et al. (Reference Li, Lindquist and Yang2015) demonstrated that photoperiod sensitivity influences oakleaf goosefoot (Chenopodium glaucum L.) life-cycle progression and total biomass allocation in response to summer sowing dates (June to August). Later sowing favored reproduction over total biomass, while earlier sowing promoted greater vegetative and reproductive growth. Furthermore, there is evidence that growth and reproduction of C. album is highly responsive to light quality and nitrogen availability (Gramig and Stoltenberg Reference Gramig and Stoltenberg2009; Mahoney and Swanton Reference Mahoney and Swanton2008). With respect to reproductive output and persistence, C. album produces two types of seed: a brown-coated type, which exhibits lack of dormancy and germinates quickly after dispersal, and a black-coated seed, which is dormant upon shedding, creating a long-lasting seedbank in the soil (Shams et al. Reference Shams, Kupdhoni, Arifur Rahman Khan and Nahidul Islam2023). Such variability in seed longevity poses challenges for both short- and long-term weed management.

Weed control strategies in commercial lima and snap bean typically include cultural (e.g., crop rotation, cover crops, spring tillage), mechanical (e.g., cultivation, false and stale seedbeds), and chemical (e.g., imazamox, bentazon, fomesafen) methods (Pavlovic et al. Reference Pavlovic, Colquhoun, Korres, Liu, Lowry, Peachey, Scott, Sosnoskie, VanGessel and Williams2025; Peachey Reference Peachey2019; Soltani et al. Reference Soltani, Shropshire and Sikkema2013). Among weed management tactics, preemergence and postemergence herbicides are the most widely used, often providing more than 80% control (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Wilson and Hines2003; Beiermann et al. Reference Beiermann, Creech, Knezevic, Jhala, Harveson and Lawrence2022a, Reference Beiermann, Miranda, Creech, Knezevic, Jhala, Harveson and Lawrence2022b). Postemergence herbicides for broadleaf weed control in lima and snap bean are limited to bentazon, imazamox, and halosulfuron. Bentazon (Basagran®, BASF Corporation, Florham Park, NJ, USA) is often tank mixed with imazamox to expand the spectrum of control and improve efficacy. The imazamox (Raptor®, BASF Corporation, Florham Park, NJ, USA) label requires the addition of bentazon in lima and snap bean to minimize crop injury. Halosulfuron (Gowan Company, Yuma, AZ, USA) is labeled for use in lima and snap bean at the second to fourth trifoliate growth stage. However, its application often causes crop injury, stunted growth, and in some cases, reduced yield (Peachey Reference Peachey2019).

Bentazon is a postemergence herbicide that inhibits the photosynthesis II (PSII) by blocking electron transport in chloroplasts. It competes with quinone for the D1 protein binding site, preventing the reoxidation of plastoquinone A (QA) and effectively halting photosynthetic activity (Shaner et al. Reference Shaner, Jachetta, Senseman, Burke, Hanson, Jugulam, Tan, Reynolds, Strek and McAllister2014). Although effective, bentazon has limited translocation in plants (Wills Reference Wills1976) and is rapidly metabolized in several crops, such as navy bean (Mahoney and Penner Reference Mahoney and Penner1975), soybean, wheat, and corn (reviewed by Qiao et al. Reference Qiao, Lv, Chen, Liu, Yang and Zhang2023). In these species, bentazon is detoxified via cytochrome P450–mediated hydroxylation to 6-OH- or 8-OH-bentazon (Kato et al. Reference Kato, Yokota, Suzuki, Fujisawa, Sayama, Kaga, Anai, Komatsu, Oki, Kikuchi and Ishimoto2020), followed by glucose conjugation (Qiao et al. Reference Qiao, Lv, Chen, Liu, Yang and Zhang2023), likely facilitated by ABC transporters localized to the plasma membrane (Qiao et al. Reference Qiao, Wang, Gu, Zhang, Yan and Liu2025). Despite the widespread use of bentazon in soybean during 1970s (Penner Reference Penner1975), the discovery of acetolactate synthase (ALS)-inhibiting herbicides provided better benefits for soybean growers, selectively controlling important weed species at low application rates while providing crop safety and residual activity. However, bentazon has remained an important herbicide option in other crops such as lima and snap bean (Hekmat et al. Reference Hekmat, Soltani, Shropshire and Sikkema2008; Herrmann et al. Reference Herrmann, Goll, Phillippo and Zandstra2017).

The evolution of herbicide resistance is a top concern in specialty crops that have limited herbicide options (Boyd et al. Reference Boyd, Moretti, Sosnoskie, Singh, Kanissery, Sharpe, Besançon, Culpepper, Nurse, Hatterman-Valenti, Mosqueda, Robinson, Cutulle and Sandhu2022). Recently, reduced efficacy of bentazon to control C. album has been identified by practitioners, raising the question of whether escapes are due to herbicide resistance evolution. As of 2025, a total of 51 unique cases of herbicide-resistant C. album have been documented, including 24 confirmations in the United States (Heap Reference Heap2025). Most of these reports involve resistance to PSII inhibitors (e.g., atrazine, simazine, cyanazine, metribuzin, and terbacil). The first case of PSII-inhibitor resistance in C. album was reported in 1973 in Ontario, Canada, with resistance to atrazine in cornfields (Heap Reference Heap2025). In the United States, triazine-resistant C. album populations are concentrated in the Corn Belt, where continuous corn cultivation and repeated triazine use has intensified selection pressure and resistance evolution (Bajwa et al. Reference Bajwa, Zulfiqar, Sadia, Bhowmik and Chauhan2019). These herbicides persist in the soil, further promoting the selection for resistant biotypes.

Considering that C. album exhibits large phenotypic plasticity that could impact overall response to bentazon (particularly when comparing populations from distinct geographic regions) and that bentazon is often sprayed by farmers in tank mixture with imazamox, a better understanding of the underlying response to bentazon treated alone is needed. While bentazon resistance in C. album has not yet been documented, the weed’s widespread distribution and adaptability require proactive monitoring of population response. Because bentazon remains an important herbicide in lima and snap bean production, resistance to bentazon would significantly reduce chemical weed control options for growers. Therefore, establishing the current response to bentazon is essential for evaluating variation in herbicide sensitivity across weed populations, reporting resistance evolution, informing management practices, and supporting regulatory assessments of current control measures. Thus, the objectives of this project are to (1) evaluate the effectiveness of bentazon on C. album populations collected from lima and snap bean fields in Delaware, Illinois, Minnesota, New York, and Oregon; and (2) determine whether reports of poor bentazon performance can be attributed to herbicide resistance evolution.

Material and Methods

Source of Plant Material

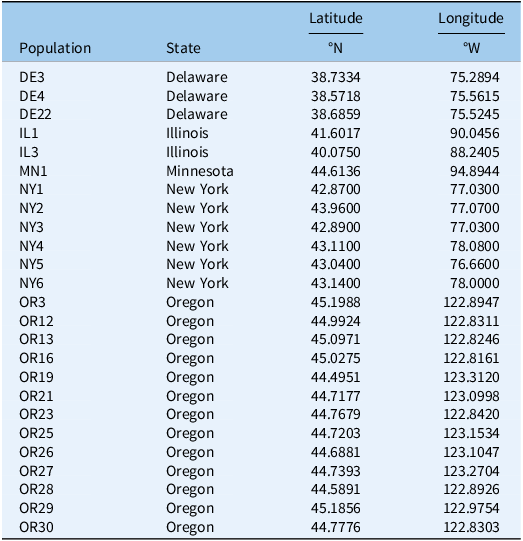

Seeds were collected from lima and snap beans fields in Delaware (n = 3), Illinois (n = 2), Minnesota (n = 1), New York (n = 6), and Oregon (n = 13), as part of a weed community survey in lima and snap bean across major growing regions in the United States conducted from 2019 to 2023 (Pavlovic et al. Reference Pavlovic, Colquhoun, Korres, Liu, Lowry, Peachey, Scott, Sosnoskie, VanGessel and Williams2024). For analysis purposes, the small number of samples from Illinois and Minnesota were combined and are collectively referred to as “Northcentral” populations. In brief, seeds were collected from at least 20 mature plants at each site, randomly selected from those that had survived weed control measures during the growing season. Seed heads were threshed and cleaned, and seeds from each site were pooled and stored at room temperature until further analysis. The population coordinates of origin are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Sources of Chenopodium album populations.

Determination of Response to Bentazon in Chenopodium album

Seeds from populations were germinated in trays filled with commercial potting media (PRO-MIX BX, PRO-MIX, Quakertown, PA, USA), transplanted to cell trays at the 2-leaf stage, and kept in a greenhouse. Dose–response experiments were performed in a completely randomized design with four replicates (one plant per pot as an experimental unit), and the experiments were repeated. Herbicide rates were 0 (nontreated control), 131, 262, 525, 1,050, 2,101, 4,203, and 8,406 g ai ha−1 of bentazon (Basagran® 5L, BASF), including nonionic surfactant (0.25% v/v), and sprayed when plants had 3 to 4 fully expanded leaves. These rates were based on a preliminary experiment to identify the range of doses for the dose–response experiments, which consisted of performing a dose–response experiment with a subset of the populations with 10 rates (from zero to two times the field rate). The bentazon labeled rate for C. album control is between 560 to 1,120 g ha−1 (depending on weed size). Treatments were applied using a commercial track sprayer (DeVries Manufacturing, Hollandale, MN, USA) equipped with an 8002EVS nozzle (TeeJet®, Spraying Systems, Denver, CO, USA) calibrated to deliver 187 L ha−1. Injury ratings (0% represents no injury and 100% plant death) were assigned to individual experimental units at 28 d after application (DAA), followed by sampling of aboveground tissue for biomass assessments. Biomass was assessed by drying samples at 60 C for 5 d.

Data Analysis

The data across the two experimental runs were pooled upon inspection for homoscedasticity of variance across runs with a Levene’s test (α = 0.05), followed by fitting four-parameter log-logistic models (Equation 1) (Knezevic et al. Reference Knezevic, Streibig and Ritz2007):

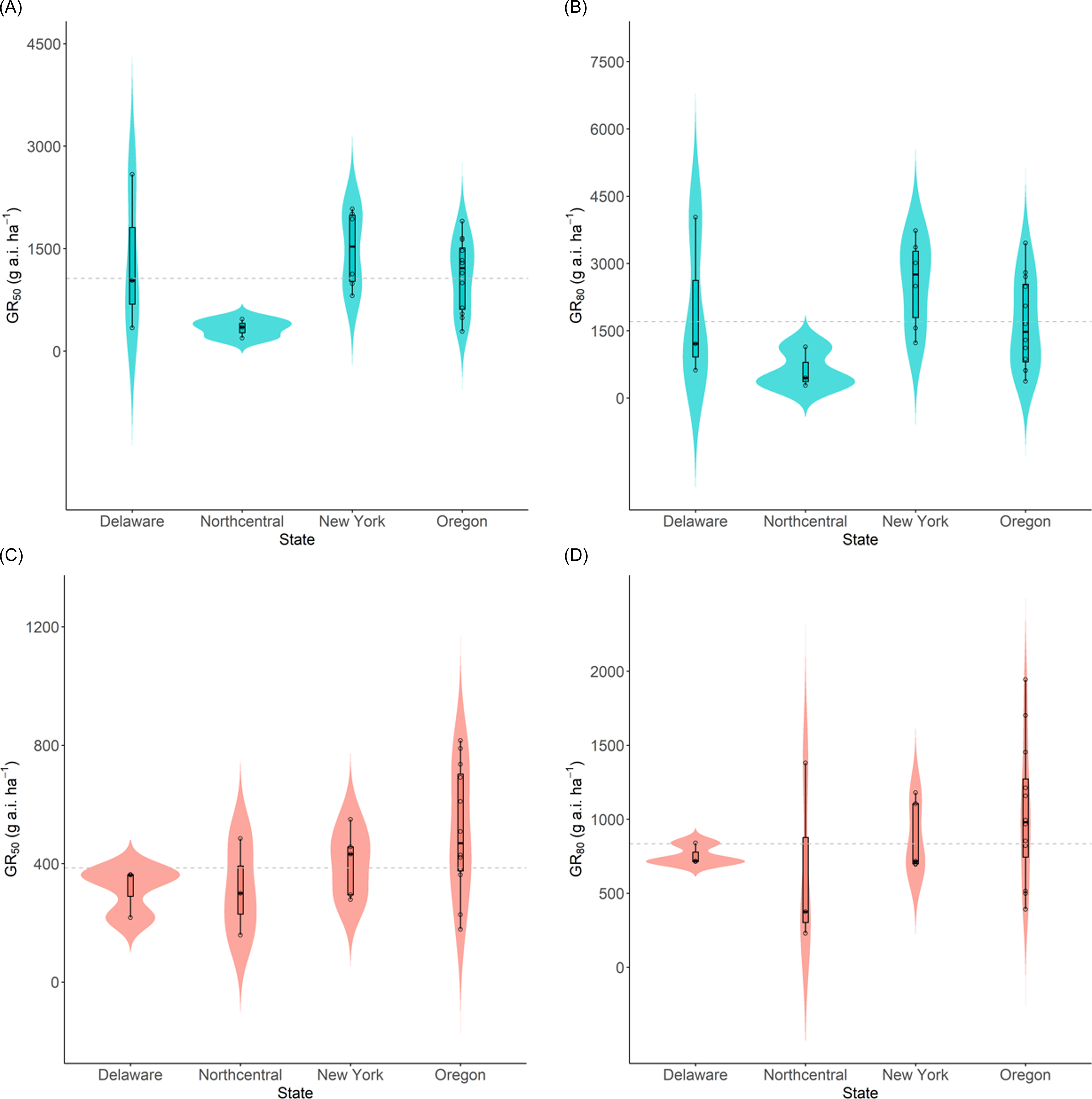

where Y is the response variable as injury ratings or dry biomass at 28 DAA as a percentage of the nontreated control, b is the slope of the curve, c is the lower asymptote, d is the upper asymptote, I50 or I80 is the herbicide rate required to increase visual injury by 50% or 80%, and GR50 or GR80 is the herbicide rate required to reduce plant dry biomass by 50% or 80%. Confidence intervals were generated with the predict function in R and plotted with ggplot2. To better illustrate the distribution density of bentazon sensitivity levels across populations, I50, I80, GR50, and GR80 estimates are presented using violin plots created in R.

Dose–response data were used to dissect the underlying response of C. album to bentazon. Biomass-based GR50 estimates were pooled across populations within each state or region, excluding the outliers, GR50 estimates that were not statistically different than zero, to obtain a single average estimate for each state. The GR50 parameter was selected because it provides the most accurate estimate of plant response to herbicides with minimal error around the mean (Seefeldt et al. Reference Seefeldt, Jensen and Fuerst1995). Within each state (or region), we identified the population with biomass-based GR50 that was closest to the calculated state average and designated it as the representative susceptible reference population to account for potential genetic background differences among geographic regions. This approach differs from alternative methods such as the baseline sensitivity index, which calculates the simple average GR50 between the most and least susceptible populations and does not account for populations that exhibit extreme high or low herbicide sensitivity (Crespo et al. Reference Crespo, Wingeyer, Borman and Bernards2016; Lim et al. Reference Lim, Kim, Noh, Lim, Yook, Kim, Yi and Kim2021; Paterson et al. Reference Paterson, Shenton and Straszewski2002). Our method of averaging GR50 values on a per region basis will result in better representation of the underlying response to bentazon while accounting for the local environment (Burgos et al. Reference Burgos, Tranel, Streibig, Davis, Shaner, Norsworthy and Ritz2013). Resistance indices (RIs) were subsequently calculated by dividing the herbicide rate required to achieve 50% injury or biomass reduction in suspected resistant populations by the corresponding rate for the selected susceptible reference population. We chose not to select the population with the lowest GR50 as the local reference population to avoid overestimation of RIs that would lead to susceptible populations being misinterpreted as resistant. Pairwise comparisons were performed with a t-test (α = 0.05). A population was considered resistant if it met two conservative criteria: (1) the injury rating- or biomass-based RI must be greater than 2.0 (based on a two-sided one-sample t-test; α = 0.05), and (2) the injury rating- or biomass-based I80 or GR80 must be greater than the highest labeled field rate (1,120 g ha−1). These criteria put less emphasis on the RI50 estimates and will account for the fact that we are using different reference populations.

Results and Discussion

Whole-Plant Dose–Response Experiments Revealed a Wide Variation in Chenopodium album Response to Bentazon

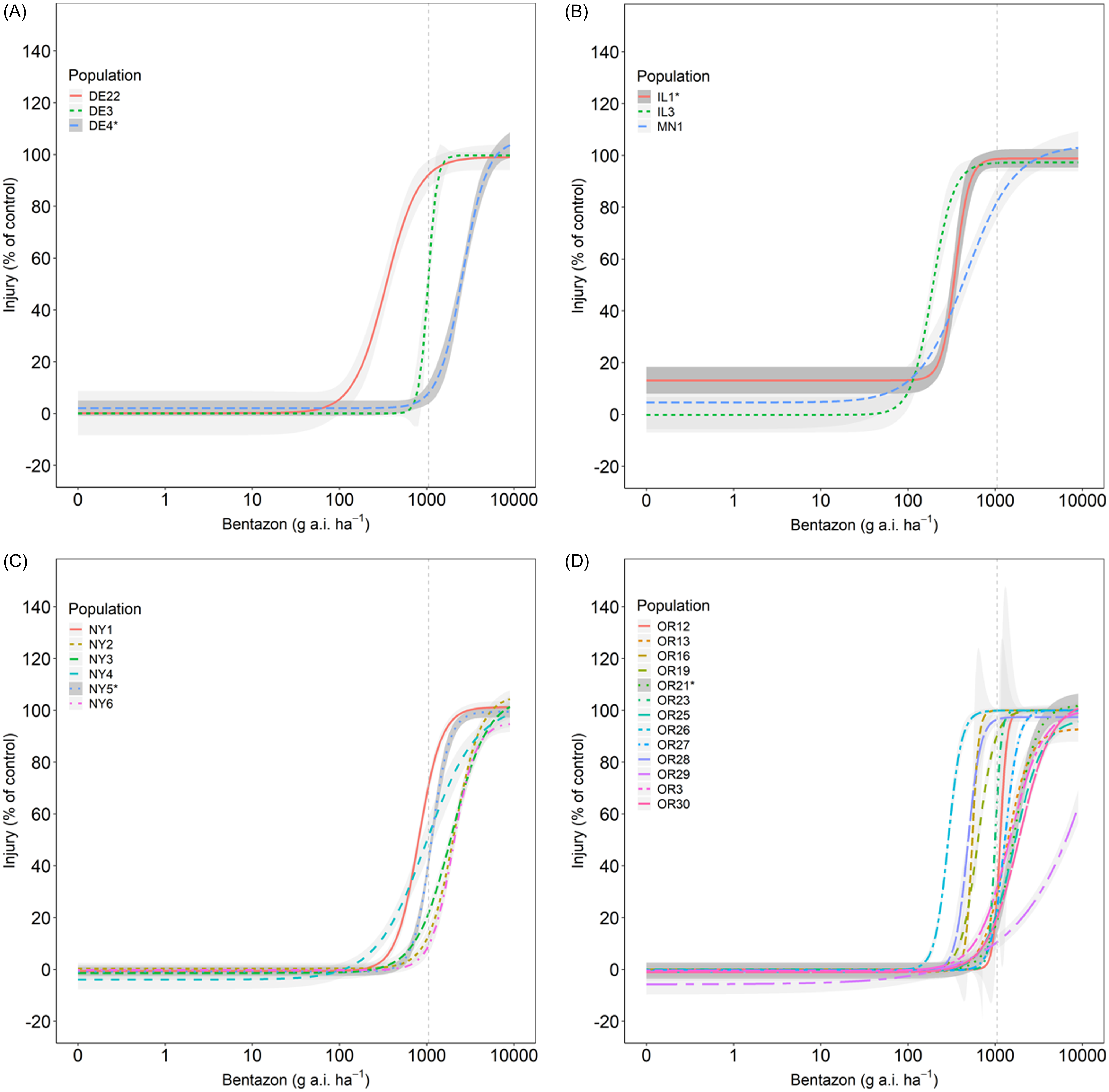

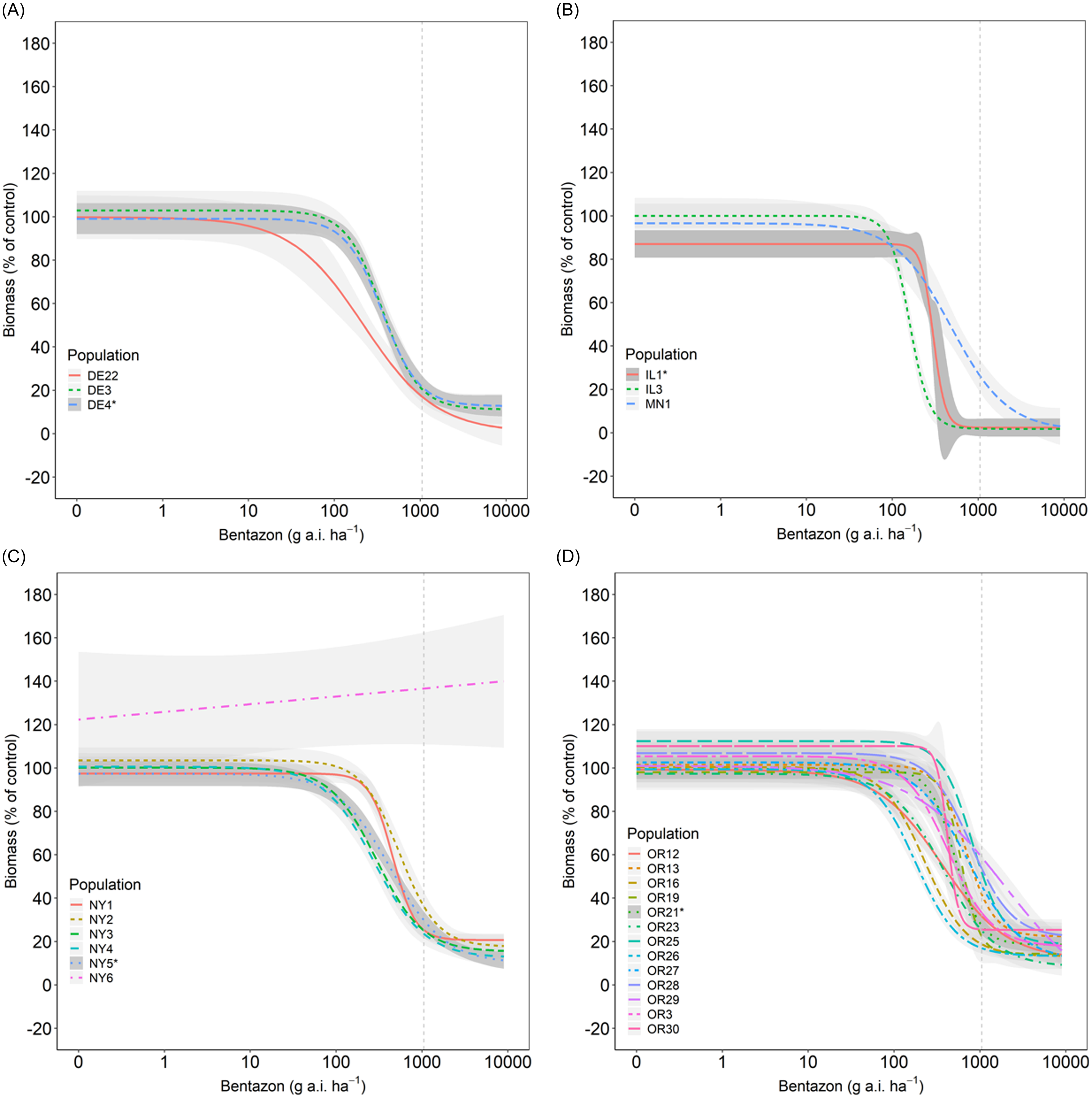

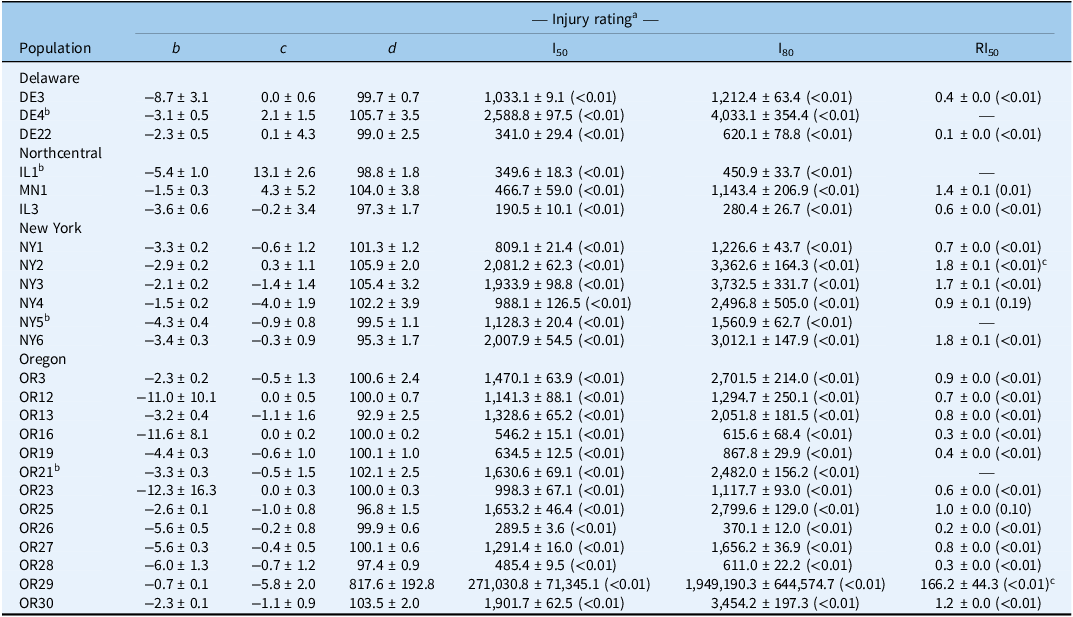

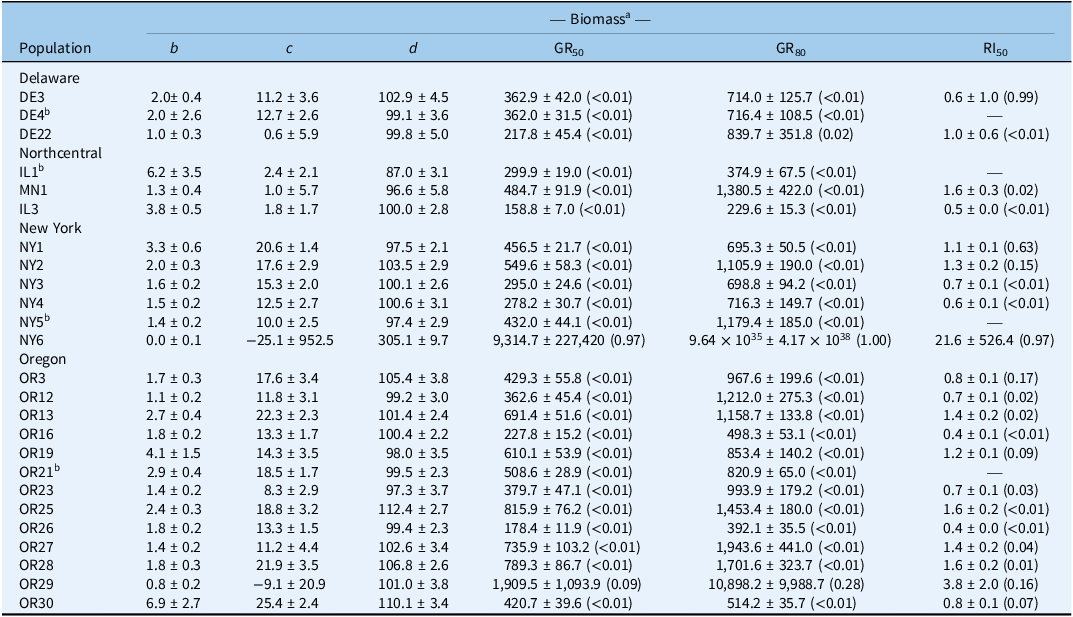

We observed a wide range of C. album responses to bentazon (Figures 1 and 2) depending on the geographic region where a population originated. The I50 of populations collected in Delaware ranged from 341 to 2,589 g ha−1 for injury ratings (Table 2; Figure 1A), with population DE22 exhibiting the lowest I50 (314 g ha−1), and DE4 the largest (2,588 g ha−1), with a 7.6-fold variation in response. Similarly, the I80 estimates exhibited a 6.5-fold variation (620 to 4,033 g ha−1). The biomass GR50 ranged from 218 to 363 g ha−1, and 714 to 840 g ha−1 for the GR80, 1.7- and 1.2-fold variations, respectively (Table 3; Figure 2A). The distribution density of I50,80 values suggests that Delaware populations exhibited the largest variability in injury rating in response to bentazon, as indicated by the extended height of their respective violin plots (Figure 3A and 3B). The Northcentral populations had the greatest susceptibility to bentazon (Figures 1B and 2B), based on injury ratings (I50: 191 to 467 g ha−1; I80: 280 to 1,143 g ha−1) and biomass (GR50: 159 to 485 g ha−1; GR80: 230 to 1,381 g ha−1).

Figure 1. Dose–response models of bentazon in Chenopodium album populations from Delaware (A), Northcentral states (B), New York (C), and Oregon (D). Injury ratings assessed at 28 d after application. Vertical dashed lines represent the label rate (1,120 g ai ha−1).

Figure 2. Dose–response models of bentazon in Chenopodium album populations from Delaware (A), Northcentral states (B), New York (C), and Oregon (D). Biomass assessed at 28 d after application. Vertical dashed lines represent the label rate (1,120 g ai ha−1).

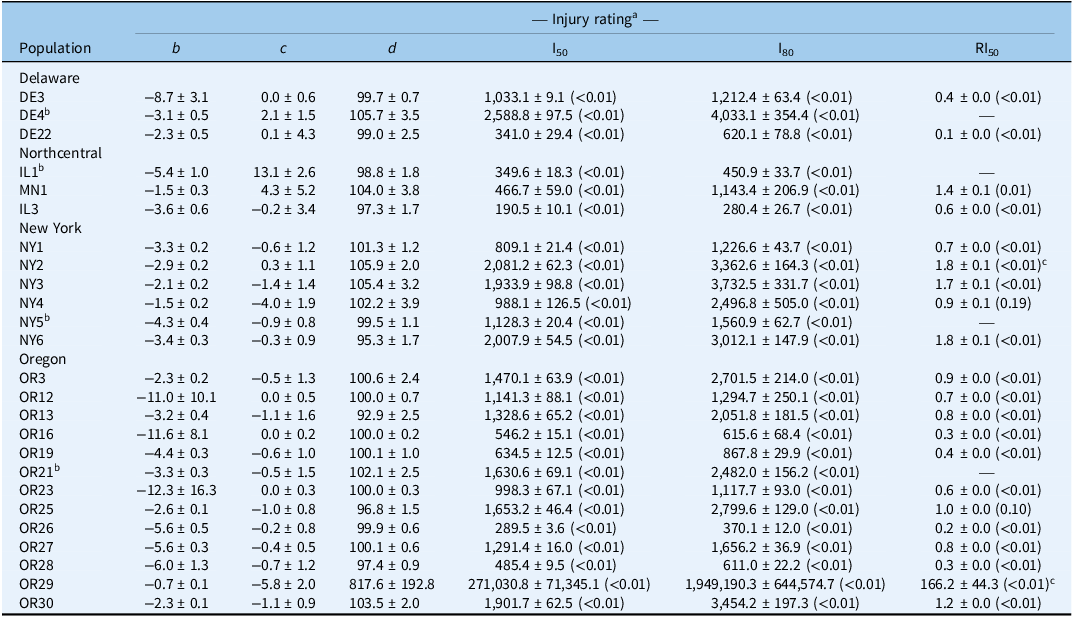

Table 2. Four-parameter log-logistic estimates for Chenopodium album populations from Delaware, Northcentral states, New York, and Oregon.

a Injury ratings assessed 28 d after treatment. Mean values are followed by their SEs; P-values provided in parentheses; b is slope of the curve, c is lower asymptote; d is the upper asymptote; I50/80 is the herbicide rate that achieves injury rating by 50% or 80%, respectively; RI50 is the resistance index for bentazon, calculated by dividing the I50 of the resistant by the susceptible population.

b Reference susceptible for state.

c Indicates whether the I50 is statistically different than 2.

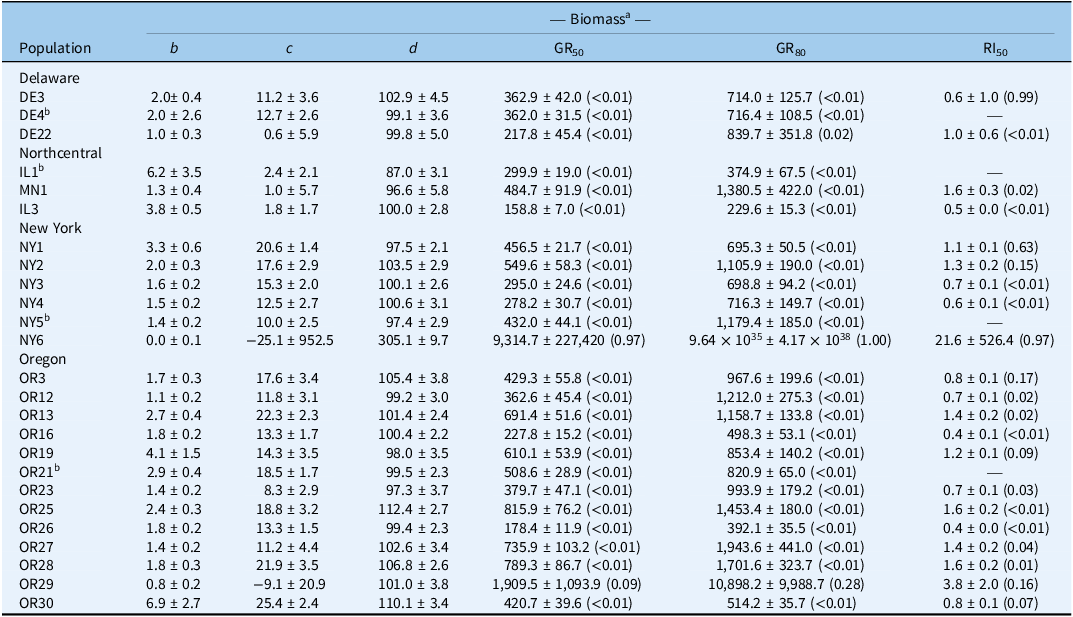

Table 3. Four-parameter log-logistic estimates for Chenopodium album populations from Delaware, Northcentral states, New York, and Oregon.

a Biomass assessed at 28 d after treatment. Mean values are followed by their standard errors; P-values provided in parentheses; b is slope of the curve; c is lower asymptote; d is the upper asymptote; GR50/80 is herbicide rate that reduces biomass by 50% pr 80%, respectively; RI50 is the resistance index for bentazon, calculated by dividing the GR50 of the resistant by the susceptible population.

b Reference susceptible for state.

Figure 3. Distribution density of sensitivity to bentazon in Chenopodium album populations from Delaware, Northcentral states, New York, and Oregon. Average growth reduction estimates (I50 and I80) for injury rating (A, B) and biomass (C, D). Horizontal dashed lines represent the total average I50/80 or GR50/80 for each variable.

New York populations had the highest I50,80 and GR50,80 estimates (Table 4), where the I50 ranged from 809 to 2,081 for injury rating (Table 2; Figure 1C), and 278 to 550 g ha−1 for biomass-based GR50 data (Table 3; Figure 2C). The I80 estimates ranged from 1,227 to 3,733 g ha−1 for injury ratings, and 695 to 1,179 g ha−1 for biomass. Our statistical approach did not result in reliable biomass-based estimates for NY6, because the chosen bentazon rates failed to provide complete control.

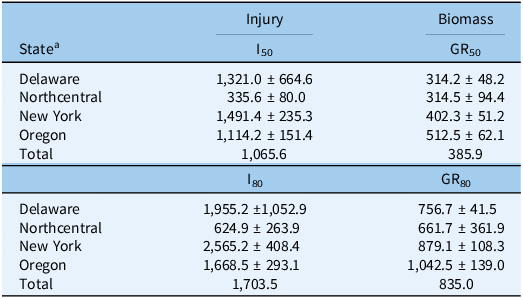

Table 4. Bentazon rate required to achieve growth reduction (I50 or GR50 and I80 or GR80) for Chenopodium album populations collected in Delaware, Northcentral states, New York, or Oregon based on injury rating and biomass.

a Populations averaged within state followed by SEs.

Oregon populations had I50 estimates ranging from as low as 290 g ha−1 to as high as 1,902 for injury ratings (Table 2; Figure 1D). Injury-based I80 estimates had a 9.3-fold variation (Table 2), ranging from 370 to 3,454 g ha−1. Biomass-based GR50 estimates varied nearly 5-fold, from 178 to 816 g ha−1, and GR80 from 392 to 1,944 (5-fold), indicating moderate bentazon response variation among Oregon populations (Tables 1 and 2; Figures 1D and 2D). For one of the populations, OR29, we were not able to have a good fit of the log-logistic model for biomass data due to incomplete control with bentazon.

Our dose-response data suggest that most populations required bentazon rates above the typical labeled field rate for lima and snap bean (1,120 g ha⁻1) to achieve 80% control (8 populations based on injury ratings, and 16 based on biomass data) (Figures 1 and 2; Tables 1 and 2). In some cases, populations from Oregon (OR27 and OR28) required more than 1.5-fold increases in the labeled field rate to achieve 80% biomass reduction (Table 3; Figure 3), while OR29 and NY6 required more than 2.7-fold bentazon to achieve 80% of injury ratings (Table 2).

Comparing our results with those of other studies on bentazon efficacy for C. album, a potential shift in the response of populations in recent years is apparent. The bentazon rates required for C. album control in our study were notably higher than those reported in previous research. For example, Parks et al. (Reference Parks, Curran, Roth, Hartwig and Calvin1996) achieved around 48% biomass reduction in C. album with 70 g ha−1 of bentazon. In contrast, the most sensitive populations that we studied (IL3 and OR26) required 159 and 178 g ha−1, respectively, to achieve similar growth reductions (based on GR50), a 2.3- to 2.5-fold greater tolerance to the herbicide (Table 3). Other studies have reported greater than 90% control with bentazon rates ranging from 560 to 1,120 g ha−1 (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Wilson and Hines2003; Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Renner and Penner1995; Harvey Reference Harvey1991; Peachey Reference Peachey1995). Herrmann et al. (Reference Herrmann, Goll, Phillippo and Zandstra2017) observed over 70% control with bentazon rates above 560 g ha−1. However, in our study, the average bentazon rate required to achieve 80% control across states ranged from 625 to 2,565 g ha−1 based on injury ratings, and from 662 to 1,043 g ha−1 based on biomass assessments (Table 4; Figure 3). These findings highlight the need to include a diverse germplasm when assessing weed response to herbicides to account for variability that could be confounded with local adaptation.

Sensitivity Survey Identifies Bentazon-Resistant Chenopodium album Populations

Sensitivity surveys are key to determining the general response of weed populations to a given herbicide, allowing for detection of shifts in population response, as well as confirming the evolution of herbicide resistance. The average biomass-based GR50 across populations was 314, 315, 402, and 513 g ha−1 for Delaware, populations from the Northcentral states, New York, and Oregon, respectively (Table 4; Figure 3). Using the average biomass-based GR50 for each state, we identified a local reference bentazon-susceptible population for comparison purposes. We rely on biomass assessments to identify the local susceptible references, because (1) fitting log-logistic models to susceptible populations is often successfully accomplished, as opposed to resistant populations, where visual injury may be absent even at high herbicide rates; and (2) biomass provides a more objective data type. Therefore, populations designated as susceptible for each state or region included DE4 (GR50 = 362 g ha−1), IL1 (GR50 = 300), NY5 (GR50 = 432), and OR21 (GR50 = 509) for Delaware, Northcentral states, New York, and Oregon, respectively.

Following identification of local reference susceptible populations, we assessed whether populations that exhibited reduced response to bentazon could be confirmed as cases of herbicide-resistance evolution. The RI50 values based on injury ratings ranged from 0.1 to 0.4 for Delaware populations, 0.6 to 1.4 for populations from the Northcentral states, 0.7 to 1.8 for New York populations, and 0.2 to >100 for Oregon populations (Table 2). Similarly, the biomass-based RI50 was 0.6 to 1 for Delaware populations, 0.5 to 1.6 for populations from the Northcentral states, 0.6 to 22 for New York populations, and 0.4 to 3.8 for Oregon populations (Table 3). Populations OR29 and NY6 meet our resistance criteria because they exhibited an injury rating- or biomass-based RI values >2 and required I80 or GR80 rates that exceeded the maximum labeled rate (1,120 g ha−1).

To date, four weed populations with resistance to bentazon have been reported worldwide (Heap Reference Heap2025). The resistance mechanism to bentazon in redroot pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus L.) identified by Li et al. (Reference Li, Cao, Liu, Wei, Huang, Lan, Sun and Huang2022) was overexpression of the psbA gene and enhanced herbicide metabolism, resulting in high RI values (>6-fold). Another report documented cross-resistance in Powell amaranth (Amaranthus powellii S. Watson), where an amino acid substitution (valine to isoleucine at position 219) conferred resistance not only to bentazon but also to other PSII inhibitors (Dumont et al. Reference Dumont, Letarte and Tardif2016). Although resistance confers survival advantage under herbicide selection pressure, this trait may come with a fitness trade-off. Solymosi and Lehoczki (Reference Solymosi and Lehoczki1989) found that C. album biotypes resistant to PSII inhibitors had reduced biomass, seed weight, and seed number, potentially slowing resistance spread over time and increasing wind dispersal to long distances. In California arrowhead (Sagittaria montevidensis Cham. & Schltdl.), studies on seed ecology in bentazon-resistant biotypes revealed reduced germination despite comparable viability, suggesting possible ecological trade-offs in resistant populations (Pitol et al. Reference Pitol, Cechin, Schreiber, Moisinho, Andres and Agostinetto2022). Ghanizadeh and Harrington (Reference Ghanizadeh and Harrington2019) found that triazine-resistant C. album had early vegetative stage fitness costs, which became reduced as plants matured, suggesting that early competitive suppression could be an effective management strategy. Future research should investigate whether the populations from our study also exhibit any fitness penalty associated with bentazon-resistance evolution.

Our study reports on the current sensitivity to bentazon in C. album populations from lima and snap bean fields collected across five U.S. states and underscores the wide variation in C. album response to bentazon across the country, as well as the importance of a better understanding of the baseline response of weed populations to herbicides and accounting for local variation in dose–response studies. The presence of resistant populations in geographically distant states, including New York states and Oregon, presents a key question concerning whether resistance is evolving independently in response to local weed characteristics and management practices, or whether resistant populations were introduced. Future work could investigate the genetics of these populations to elucidate their relatedness (Goncalves Netto et al. Reference Gonçalves Netto, Ribeiro, Nicolai, Lopez Ovejero, Silva and Junior2025; Ribeiro et al. Reference Ribeiro, Gallagher, Mallory-Smith, Barroso and Brunharo2025). Our study also highlights the advantage of creating baseline sensitivities for a better characterization of herbicide resistance, because arbitrarily choosing a reference susceptible population, or a population with the greatest susceptibility to the target herbicide, has the potential to inflate RIs, resulting in reporting herbicide resistance when there is none (i.e., false positive), potentially leading to misinterpretations from stakeholders. Given the increasing need for higher bentazon rates and evidence of partial control, integrated weed management strategies are essential to avoid the spread and evolution of resistance. This includes preventive practices like equipment sanitation, rotating herbicide modes of action, using tank mixtures, applying competitive pressure early in the season, and tailoring control strategies based on state-level resistance patterns.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and Regional Research Appropriations under Project no. PEN04818 and Accession no. 7004166 (CB).

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.