Introduction

At the recent Synod charge of the Diocese on the Niger held at All Saints’ Cathedral, Onitsha, on June 10, 2022, titled ‘Reflections on the History of the Diocese on the Niger’, Bishop Owen Nwokolo of the Diocese on the Niger reaffirmed the historical importance of the diocese in Western Africa and its centrality to the life and mission of the Church in Nigeria and the Anglican Communion at large. Bishop Nwokolo expressed concern that the diocese’s profound historical significance is frequently undervalued or misinterpreted in current discussions within the Church of Nigeria Anglican Communion. He emphasized the necessity for the faithful to grasp historical context as a means to shape the future in accordance with the Anglican Communion’s values and mission. In his narrative of the Diocese on the Niger’s history, set against the backdrop of the nineteenth-century founding of the Anglican Communion in Nigeria, Bishop Nwokolo also made efforts to clarify several misunderstandings surrounding the diocese’s legacy.

A growing body of scholarship explores the ramifications of contested histories, particularly their influence on contemporary perceptions of ‘past’ events and identity formation in indigenous communities (Gordon and McCormick, Reference Gordon and McCormick2013; Gray and Sloan, Reference Gray and Sloan2014). Contested history theories explain variations in historical interpretations contingent on the perspective of the narrator (Gordon and McCormick, Reference Gordon and McCormick2013). Owing to factors such as ideological disparities, political affiliations, class, culture, ethnicity, religion, gender and power dynamics, these narratives can exhibit significant differences across generations (Gordon and McCormick, Reference Gordon and McCormick2013). Hence, it is important to acknowledge and scrutinize these narratives to ascertain their influence on contemporary history and community identity.

The enduring impact of disputed historical narratives extends beyond mere acknowledgement and rectification of historical inaccuracies; it also pertains to understanding how past and present events inform individual and communal identities (Gordon and McCormick, Reference Gordon and McCormick2013). Viewed through the prism of identity and community, historical narratives can be instrumental in the establishment, preservation and challenging of power structures via the ascription of meanings to past events (Gray and Sloan, Reference Gray and Sloan2014). This contested paradigm underscores the importance of appreciating the history and legacy of the Diocese on the Niger within the broader context of Western African Christianity and the Anglican Communion, encompassing colonial, imperial and contemporary political narratives.

This historical perspective enriches our understanding of the identity of the indigenous churches within the Anglican Communion in the twenty-first century. As the Diocese on the Niger continues to hold its place within the Church of Nigeria Anglican Communion, its establishment and evolution provide an insightful contrast to the narratives of other dioceses and churches that emerged during the colonial period. The history of the Diocese on the Niger offers a valuable case study for theories addressing the contested nature of history and identity within the Anglican Church and broader society.

While primarily focusing on the disputed history of the Diocese on the Niger, we do not purport to provide an exhaustive history of the Anglican Church in Nigeria. Rather, we analyse the historical context of the diocese’s establishment in the nineteenth century and its broader implications for the Anglican Communion and Nigerian society. We do not intend to engage in theological and political debates concerning the diocese’s establishment or the evolution of the Anglican Communion’s polity in Nigeria over the past 160 years. Consequently, this paper should be regarded as a factual historical account, rather than an attempt to stake a position on the ongoing discourse surrounding colonial legacy within the Church of Nigeria Anglican Communion and globally.

The Diocese on the Niger

The origins of the Diocese on the Niger can be traced back to the missionary activities of the Church Missionary Society (CMS), under the leadership of Samuel Ajayi Crowther, an indigenous missionary priest who later ascended to the bishopric of the diocese (Ross, Reference Ross1960). As the mission expanded, the need to appoint Crowther as a bishop became increasingly evident. Thus, on June 29, 1864, Crowther was consecrated as the inaugural African bishop of the Western Africa District by the Archbishop of Canterbury at Canterbury Cathedral, a significant milestone in the history of the Anglican Communion (Barnes, Reference Barnes2018).

The First Indigenous Bishop

Bishop Crowther was designated as the leader of the CMS mission to the Niger area, a role which implicitly placed him as the indigenous spiritual overseer throughout the Western region of Africa. His leadership played a pivotal role in church growth in the region, laying a robust groundwork for subsequent missions and the evolution of the church in the area (Crowther, Reference Crowther1866). The converts Crowther garnered during his missionary activities exhibited loyalty to him and subsequently became strong advocates of the new diocese, which he established along the Niger river in West Africa. These initial converts, along with the early missionaries, were instrumental in shaping the history of the diocese and, by extension, the trajectory of the Anglican Church in Western Africa (Kwashi, Reference Kwashi2013; Ross, Reference Ross1960).

However, there exists a paradoxical situation within the Church of Nigeria Anglican Communion with regard to Bishop Crowther’s recognition and legacy. On one hand, Crowther is acknowledged as the founding figure of the Anglican Church in Nigeria. His pioneering efforts to establish the church in the region have been widely accepted and documented. This is a testament to his enduring legacy and the influential role he played in the establishment and growth of Anglicanism in Nigeria. On the other hand, it is a matter of historical contention that the diocese which Crowther led – arguably the seedbed of the Anglican Church in Nigeria – is not recognized as the first indigenous diocese within Nigerian boundaries. Consider, for instance, the Church Year Calendar of the Church of Nigeria, Anglican Communion. Since its inception in 1979 through to the present day, there is no mention of Bishop Crowther’s episcopal service. The recorded history of Nigerian Bishops prior to 1979 begins with Bishop Melville Jones in 1919, leaving a glaring omission of Crowther and his successors’ contributions (refer to the Church Year Calendar from 1979 to 2022, initial sixty pages each year). This lack of recognition for Bishop Crowther in the ecclesiastical chronicles could potentially be viewed as an attempt to downplay his substantial influence on the Niger area’s episcopal ministry. Erivwo (Reference Erivwo1979) expressed concern about how the CMS disassembled Crowther’s mission work, seemingly with the intention to delegitimize his achievements within the Niger Mission. This perceived dismissal of Crowther’s contributions did not go without ramifications. It set the stage for the emergence of African Independent Churches (Erivwo, Reference Erivwo1979), demonstrating how historical narratives can significantly impact religious evolution and identity formation.

This seeming inconsistency about the episcopal ministry of Bishop Crowther raises questions about the criteria for such recognitions and how they are applied within the Church of Nigeria Anglican Communion. Moreover, the narratives about Crowther’s missionary activities in the region are frequently skewed, often reflecting the perspectives and interests of those recounting his apostolic work (Hanciles, Reference Hanciles1994; Stevens, Reference Stevens2023). This can lead to biased interpretations that favour certain perspectives over others, often to the detriment of a holistic and balanced understanding of Crowther’s contributions and the historical realities of his time. This incongruity – of recognizing Crowther as a central figure in the establishment of the Anglican Church in Nigeria, while concurrently not fully acknowledging his diocese-led missionary activities – points to the complexities and challenges inherent in historical interpretations within the church. It underscores the necessity for a more comprehensive and nuanced exploration of the historical roots and evolution of the Anglican Communion in Nigeria.

Historical narratives regarding Bishop Crowther’s ministry, the first African bishop of the Western African Territories, have offered varying accounts. Some historians, like Page (Reference Page1908), have praised his achievements while others, such as Ayandele (Reference Ayandele1966), have questioned the effectiveness of his mission due to issues like ethnic rivalries and lack of strategic planning. Mgbemena (Reference Mgbemena1992) clarifies that Crowther’s bishopric in the Niger dates back to 1864, despite some sources placing it later. His influence in the Niger area was notable. He was responsible for ordaining the first set of ministers in Onitsha, which became a launching pad for further missionary activities in Nigeria. In his first synod charge in Onitsha, Crowther (Reference Crowther1866) writes:

Our first station commenced at Onitsha in 1857, where our dear brother the Rev. J. C. Taylor was landed, assisted by the late Simon Jonas, a Scripture reader. Their lodging was an oblong verandah-hovel, some three feet wide, just enough to spread mats on without any other comforts. In this place they remained for months and went out to preach as well as to work, building their own mission house on the spot which we now occupy. (p. 12)

The growth of the CMS mission in Nigeria, as outlined by Finney (Reference Finney2004, p. 122), was shaped by an increase in new converts, expansion of mission branches, and a need for leadership. This situation necessitated the evolution from missions to churches, leading to the creation of the Church of Nigeria, Anglican Communion. This transition closely mirrored the early church’s evolution, and in line with this, the CMS mission aimed to establish a self-governing, self-supporting and self-propagating church, with Henry Venn, the CMS Secretary in London, championing this strategy in 1846. Despite strong opposition, this vision resulted in the consecration of Samuel A. Crowther, the first black bishop, in 1864, marking the emergence of the Niger Territories Diocese under his leadership. However, the final years of Bishop Crowther’s tenure were mired in difficulties and escalating tensions with European missionaries under his supervision. By the 1880s, ‘dark clouds’ had started to gather over the Niger Mission. The influential supporter of Crowther, Henry Venn, had passed away (in 1873), and Crowther himself was advancing in years. The morality and efficiency of Crowther’s staff, largely made up of native Africans, were increasingly being questioned by the British missionaries (Walls, Reference Walls and Anderson1998).

Changes in mission policy, shifts in racial attitudes, alterations in evangelical spirituality, and the availability of new sources of European missionaries combined to slowly dismantle Crowther’s mission (Walls, Reference Walls and Anderson1998, Reference Walls2002). Financial controls were tightened, young Europeans began to take over key roles, and the African staff members were dismissed, suspended, or transferred (Walls, Reference Walls and Anderson1998). This systematic undermining of Crowther’s authority culminated in a damning report prepared by a CMS youth group in Cambridge, which dealt a severe blow to Crowther’s bishopric authority (Mepaiyeda and Popoola, Reference Mepaiyeda and Popoola2019; Walls, Reference Walls and Anderson1998). Historians provide varying accounts of Crowther’s final moments in office. Some suggest that Crowther, deeply disheartened by the disregard shown to his office, resigned in protest and refused to support secession (Ade-Ajayi, Reference Ade-Ajayi1965; Barnes, Reference Barnes2018). Others maintain that he was forcibly stripped of his position (Page, Reference Page2020). Regardless of the circumstances leading to his departure, it is clear that the experience profoundly impacted Crowther. Left desolate and beleaguered, Crowther succumbed to a stroke and died shortly after in 1891. The aftermath saw a European bishop succeeding him, and the landscape of the Anglican Church in West Africa forever changed.

Post-Crowther Conflict and the Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa

The passing of Bishop Crowther from a stroke on December 31, 1891, precipitated a period of profound challenge for the Church Missionary Society (CMS) across West Africa, particularly for the Niger Mission. This critical juncture was exacerbated by the absence of the late Henry Venn, the CMS Secretary, who had championed the vision of consecrating a native black bishop (Okeke, Reference Okeke2006). The aftermath of Crowther’s death provided a platform for some European missionaries to question Crowther’s leadership and the morality of his staff, resulting in the undermining and ultimate dismantling of his influence. A European bishop – Joseph Sydney Hill (Ross, Reference Ross1960) – succeeded Crowther in 1893, and it wouldn’t be until 1952, sixty years after Crowther’s death, that another native Anglican Diocesan would emerge (Ross, Reference Ross1960).

In a significant step towards reconciliation, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, acknowledged and apologized for the Church’s mistreatment of Crowther. During a ‘thanksgiving and repentance’ service marking the 150th anniversary of Bishop Crowther’s consecration, Welby expressed regret and shame over the betrayal and undermining of a rightfully consecrated bishop, stating, “It was wrong” (Anglican Communion News, 2014). Yet, despite this apology, attempts to marginalize Bishop Crowther’s contributions to the establishment of the Diocese of Niger Territories continue.

Nevertheless, the succession process following Crowther’s death underscored the legitimacy of his bishopric. For instance, the Church Missionary Society report for 1893–94 noted that the Archbishop of Canterbury accepted the Committee’s nomination of Revd Joseph Sidney Hill to the See left vacant by Bishop Crowther’s passing (CMS Archives, 1949). The archbishop then altered the title of Crowther’s Diocese to the ‘Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa’. Post Crowther’s death, the jurisdiction of Lagos was made part of the Bishop of Western Equatorial Africa’s domain in 1898. This implies that throughout his tenure as a missionary bishop, Crowther never held authority over Lagos. Instead, he presided over a diocese whose Episcopal See was located in Onitsha, thus governing territories to the east and west (Mgbemena, Reference Mgbemena1992).

Succeeding Crowther, Bishop Joseph Sydney Hill assumed leadership in 1893, covering the same geographical span as Crowther, but under the new title of the Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa (Ross, Reference Ross1960). Shortly after Hill’s death in 1894, Bishop Herbert Tugwell was consecrated and continued to uphold Onitsha as the headquarters of the Diocese (Ross, Reference Ross1960). In fact, under Tugwell’s tenure, the Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa further solidified its status by constituting its synod in 1904 and adopting the diocesan constitution in 1906 (Okeke, Reference Okeke2006). This firm establishment of the diocese in Onitsha highlights the enduring legacy of Crowther’s influence in the region.

Missionary Diocese Model and the Legacy of Crowther

Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther was ordained as the Bishop of the Church of England in West Africa on June 29, 1864, by the Archbishop of Canterbury, in the areas referred to as the Niger Territories (Page, Reference Page2020; Ross, Reference Ross1960). Following the successful formation and growth of the Igbo mission, also known as the Niger Mission, the churches in Igboland were established as a separate diocese from the Diocese of Sierra Leone in 1864, with its headquarters in Onitsha. This initiative followed the principles outlined in the Lambert Conference Archives of 1920, Resolution 34 on missionary issues, which emphasizes the establishment of self-governing, self-supporting and self-extending churches. The resolution promotes decentralization and entrusting local bodies with administrative and financial control. The intention is to encourage indigenous workers to develop the work in their own countries, reflecting their national character (Anglican Consultative Council, 1920).

Resolution 43 of the Lambert Conference Archives of 1920 provided additional guidelines for the conversion of a missionary diocese to a full-fledged episcopal diocese. It stated that the transition should occur when the missionary diocese becomes largely self-supporting and self-governed. Also, Canon 6 of the South African Church outlined specific criteria for the creation and conversion of missionary dioceses, ensuring proper governance and sufficient resources (Anglican Church of Southern Africa, 2019).

In the Church of Nigeria (Anglican Communion), the creation of both full-fledged and missionary dioceses follows this established tradition. Asadu (Reference Asadu2023) highlighted that missionary dioceses are formed as a strategy for evangelism, as they are not self-supporting and depend on external funding. However, they evolve into full-fledged dioceses over time, depending on evidence of growth and financial independence. This transition was evident in the ‘Decade of Evangelism’ in 1990 when ten missionary dioceses were created in Nigeria, all of which have since evolved into fully developed dioceses. The Abuja Diocese serves as a prime example, beginning as a missionary diocese in 1989, and now not only functioning as a full-fledged diocese but also serving as the seat of the Archbishop, Primate, and Metropolitan of the Church of Nigeria Anglican Communion.

This evolutionary pattern of the creation and development of missionary dioceses in Nigeria can be traced back to the precedent set by Bishop Crowther, who pioneered the development of autonomous, progressively maturing missionary dioceses. The diocese he fostered began as a missionary diocese and grew into a full-fledged diocese by 1906, a considerable time before the establishment of the Lagos Diocese from the Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa in 1919. Thus, whether the Diocese on the Niger began as a missionary diocese or not does not detract from its primacy as the first indigenous diocese in the Western African territory, existing long before the Diocese of Lagos. The debate isn’t about determining which diocese is the older or the younger twin, but rather it is about acknowledging the historical progression and the undeniable evidence of the sequential establishment of these dioceses.

The Diocese on the Niger’s establishment predates the Lagos Diocese, and its initial status as a missionary diocese does not diminish its precedence or importance. Indeed, its journey from a missionary diocese to a full-fledged one is a testament to its resilience, growth and the strength of its community. Bishop Crowther’s establishment of the Diocese on the Niger reflects the embodiment of the principles of the Anglican Church – nurturing a local body that could self-govern, self-sustain and expand, while preserving the national character. This strategy of evangelism and church growth remains evident in the evolution of missionary dioceses in Nigeria today. The focus, therefore, should not be on debating which diocese holds the title of the eldest, but on understanding and appreciating the unique paths each diocese took in their formation and growth. The heritage of the Diocese on the Niger as the first indigenous diocese in the Western African territory is a significant aspect of the history of the Anglican Church in Nigeria. Its evolution from a missionary to a full-fledged diocese set a precedent for subsequent dioceses in the country, including the Diocese of Lagos.

Revisiting the Primacy of the Diocese on the Niger

Navigating the layered and often contentious historical narratives surrounding the Diocese on the Niger and the Diocese of Lagos requires an understanding of the unique roles and claims associated with each entity. This exploration involves unpacking several points of contention: (1) the establishment dates of the churches; (2) the divide between the two dioceses that comprised the erstwhile unified Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa before 1919; and (3) the role of Bishop Tugwell in founding the dioceses.

First, the Diocese on the Niger’s establishment was reported as 1922, with Bishop Bertram Lasbery inaugurated as its initial bishop (Church of Nigeria, 2005, 2010, 2015). Yet, other records indicate a 1919 inception, albeit vacant until 1922 (Church of Nigeria, 2005; Kolapo, Reference Kolapo and Sachs2017). However, no centennial celebration occurred in 2022, implying an earlier start date (Adiele, Reference Adiele1996; Ross, Reference Ross1960). Supported by historical documents, Bishop Crowther declared its inception in 1864 (Adiele, Reference Adiele1996; Crowther, Reference Crowther1866; Mgbemena, Reference Mgbemena1992). Indeed, CMS missions on the Niger began on July 27, 1857, and by 1864, the Diocese of Niger Territories was founded with Bishop Crowther’s consecration. The Church Missionary Society for Africa and the East’s proceedings (1863–67) detailed the need for a bishop to ensure the organization and permanence of the burgeoning Protestant churches along Africa’s West Coast. Moreover, they outlined a plan for the indigenous bishop to work independently but benefit from the advice and moral support of a neighboring European bishop. Notably, the Diocese on the Niger marked the beginning of bishopric in the Niger territories, headquartered in Onitsha, whereas the Yoruba Mission (including Lagos) remained under the Bishop of Sierra Leone’s jurisdiction (Page, Reference Page2020). It is important to remember that the Bishop of Sierra Leone (Diocese of Sierra Leone established in 1852) covered regions within the British dominion, including Lagos, distinct from the territories allocated to Bishop Crowther. Therefore, unpacking these historical backdrops offers a nuanced understanding of the complex, multifaceted origins of these dioceses, shedding light on the ongoing discourse about their primacy.

Addressing the second issue, the Anglican Church of Nigeria’s current documentation posits that the Diocese of Lagos, inaugurated on November 10, 1919, post the division of the Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa, is the first diocese in Nigeria (Mgbemena, Reference Mgbemena1992). This perspective is articulated by Bishop Olumakaiye as he commemorates the Church of Nigeria Standing Committee Footnote 1 (Episcopal News Service, 2021). He champions the See of Lagos as the elder, or ‘Mother of all Dioceses’, in the national church, dating its creation back to December 10, 1919, and extols the evangelistic accomplishments of its past bishops. This stand, however, is not in alignment with historical accounts archived by CMS. Notably, a correspondence penned on September 19, 1919, by G.T. Manley, the CMS Secretary, details the split of the Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa and the ensuing creation of the Lagos Diocese. Footnote 2 Manley’s letter clarifies that the Diocese of Lagos was newly created, while the mother diocese, the Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa, remained intact with Bishop Tugwell retaining his position (Okeke, Reference Okeke2006). This contradicts the assertion that Lagos is the ‘Mother Diocese’, given that the Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa, later renamed the Diocese on the Niger, appointed Bishop Crowther as its first bishop years earlier. Before Bishop Crowther’s death in 1891, the Yoruba mission, under the Diocese of Sierra Leone, expressed aspirations to form their own diocese. Stock (Reference Stock1899) confirms that the Diocese of Sierra Leone extended beyond Sierra Leone, including all British possessions on West Africa’s West Coast – Gambia, Gold Coast and Lagos. Plans for a bishopric in Yoruba-speaking region were already underway as of 1888, although these plans were not fully realized until after Bishop Crowther’s death. Footnote 3 As historical documentation affirms (see Stock, Reference Stock1899 and Church Missionary Society, 1906), there was no division, per se, in the Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa. Instead, the new Lagos Diocese was carved out, leaving the mother diocese (i.e., Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa), subsequently renamed the Diocese on the Niger, intact (CMS Archives, 1949). Thus, the assertion that the Lagos Diocese is the mother of all other dioceses is misaligned with historical evidence. Footnote 4

Lastly, as Ross (Reference Ross1960) recorded, Bishop Tugwell, who was the incumbent bishop when the Lagos Diocese was carved out of the Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa, elected to remain the bishop of the latter. According to Okeke (Reference Okeke2006), the agreement to divide the diocese was reached on May 19, 1919, and the two newly formed dioceses were officially announced in November of the same year. Archdeacon Melville Jones was given charge of the Western division, along with the Episcopal supervision of the Northern Nigeria Mission. Bishop Tugwell retained control over the Niger Delta pastorate, the Igbo mission, and the section of the Cameroons which fall under the British mandate. A royal proclamation confirmed that in the Eastern division, Bishop Tugwell would continue as the diocesan bishop, although there were anticipations of his impending resignation. A.W. Howells was also appointed as an assistant bishop, succeeding Bishop James Johnson (Okeke, Reference Okeke2006). According to further documentation (see Okeke, Reference Okeke2006), Bishop Tugwell returned to Igboland as the Bishop of the Eastern diocese (i.e., Diocese on the Niger).

Bishop Tugwell continued as the Bishop of the Eastern Diocese without interruption, maintaining his position from the remaining part of the Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa. As an established diocese with a reigning bishop, there was no need for an inauguration in 1919. Furthermore, the claim that the change of name from Niger Territories to Western Equatorial Africa and then to Diocese on the Niger indicates the creation of a new diocese is historically unsubstantiated, given the traditions of Nigeria. This is exemplified by a comparable event within the Church of Nigeria Anglican Communion, where the Diocese of Okigwe North was divided into Isi-Mbano and Okigwe. Bishop Alfred Nwizuzu relocated his cathedral from Okigwe to Ezihe in Isi-Mbano and resumed his episcopal duties as Bishop of Okigwe North Diocese until his retirement. Despite the name change and relocation, the Isi-Mbano Diocese, which was inaugurated earlier (January 7, 1994), remained older than the newly inaugurated Okigwe Diocese (January 13, 2009), clearly showing that a change of diocesan name or location does not reset its historical inception.

In accordance with Anglican practice in Nigeria, an archdeacon consecrated to the bishopric does not supersede the current reigning bishop, even in situations where an inauguration is necessary (see the Principles 36.5 and 20.4 of the Anglican Consultative Council, 2008; this statement is also attributed to Archbishop Anikwenwa of Nigeria). When such circumstances arise, the incumbent bishop retains precedence. The matter at hand reflects both theological and societal dynamics, linking Anglican canon law to the age-based hierarchies prevalent in Nigeria. By examining the canonical provisions ‘Enthronement or other installation in the diocese may follow confirmation in the case of a person already in episcopal orders’ (Principle 36.5) and ‘A see becomes vacant on the death, resignation, retirement or removal of its bishop’ (Principle 20.4), one can find a robust argument against the precedence of an Archdeacon consecrated as Bishop over an incumbent Bishop. Principle 36.5 underlines the protocol of an already ordained bishop’s enthronement or installation after official confirmation. This principle supports the contention that, even in cases of the creation of a new diocese from an existing one, the reigning bishop of the original diocese maintains episcopal primacy. This continuation of authority extends to the newly formed diocese unless the incumbent Bishop’s seat becomes vacant as specified in Principle 20.4. That is to say, the office is transferred only through the death, resignation, retirement or removal of the incumbent bishop, not merely by consecrating an archdeacon to a bishopric office.

Archbishop Anikwenwa (Reference Anikwenwa2022), in a recent oral interview, appears to affirm these canonical provisions, suggesting an interplay between Church law and cultural traditions in Nigeria. In a society where seniority and age are deeply respected, the canon law supports and reinforces these societal norms within the Church structure. The established bishop, with presumably more experience and age, maintains authority unless his see is vacated. However, this dynamic invites further exploration. For example, as dioceses are divided and new bishops are consecrated, how are authority and seniority negotiated? Does the principle of respecting age and experience trump potential benefits of fresh perspectives from new leadership? These are areas that invite further scholarly investigation.

Notably, there was no alteration in the episcopal leadership during the transition from the old Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa to the new Diocese on the Niger. As such, Bishop Herbert Tugwell continued his episcopal work until he resigned in 1921 and returned to England (Ross, Reference Ross1960). His resignation came into effect on March 4, 1921, and in 1922, Bishop Bertram Lasbery succeeded him as the new Bishop of the Diocese on the Niger. In the interim period between Tugwell’s resignation and Lasbery’s appointment (March 1921 to January 25, 1922), Bishop A.W. Howells, who was consecrated as the Assistant Bishop on the Niger on June 11, 1920, undertook certain episcopal duties for the diocese.

Subsequently, Bishop Melville Jones of the Diocese of Lagos was given a temporary commission by the Archbishop of Canterbury in a letter dated October 26, 1921, to assist Bishop A.W. Howells in performing certain episcopal duties, such as the ordination of priests and deacons, that an assistant bishop was not legally permitted to perform. A non-existent diocese cannot be supervised. Hence, considering the evidence that the Diocese on the Niger was officially established prior to the Lagos Diocese, and it was in existence at the time of Bishop Melville Jones’s arrival, it is clear that the Niger diocese had a distinct ecclesiastical jurisdiction from Lagos. This was during the period before the transfer of the former bishop’s seat to the latter.

The Diocese on the Niger, formerly known as the Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa, continues to be the oldest Anglican diocese in Nigeria. Consequently, it is fitting that the church and its stakeholders acknowledge the significant role this diocese has played in propagating Christianity and maintaining the values of the CMS among Nigeria’s and Western Africa’s indigenous peoples. It should be noted that the decision to ‘divide’ the Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa into two in 1919 was primarily driven by the need to establish more dioceses to cater for the expanding Anglican Church in Nigeria, rather than by ethnic tension, although the latter cannot be completely disregarded. The claim that the Lagos Diocese is the oldest in Nigeria, to be discussed in a following section, exemplifies the challenge of reconciling divergent historical legacies among different ethnic groups in the country, highlighting a broader issue in Nigerian society.

The CMS Niger Mission and Legacy in Igboland: A Divine Providence or a Geographic Strategy?

As we analyze the story of the Diocese on the Niger, some intriguing questions arise. Why was the original Diocese of Western Equatorial Africa, now known as the Diocese on the Niger, positioned in the predominantly Igbo-speaking Eastern region instead of the Yoruba-speaking Western region? In probing this issue further, it is important to consider the theological and geographical variables that sculpted the church’s origins in the region. Several explanations have been suggested, including the notion that CMS chose to establish their indigenous Footnote 5 mission in the Eastern region – an act considered by some as divine providence (Mgbemena, Reference Mgbemena1992). While such a theological interpretation may be comforting, it lacks the nuance required to fully understand the underlying pragmatic motivations that led to the decision to plant the first indigenous Anglican mission in West Africa in Eastern Nigeria. By the same token, describing this choice as ‘God’s Plan’ brings us face-to-face with the impenetrability of divine wisdom and intention (Sharples, Reference Sharples1983). If indeed it was God’s will to birth the Niger Mission on the Eastern banks of the river Niger, then it is not within our right to challenge such divine governance. However, we can, and should, critically examine the historical and contextual factors that led to this decision during the colonial era, a time when European powers were the dominant political force in Africa. This leads us to a more critical exploration of the geographical implications of the Diocese’s location in the next paragraphs.

Geographic strategy theory (Gray and Sloan, Reference Gray and Sloan2014) is a useful lens through which to understand the practical motives underlying the placement of the mission in Igboland. The framework is used in business strategy and planning to understand how a company’s geographical location influences its strategic options, growth potential, competitive advantage and overall performance. It takes into account multiple aspects such as the firm’s value proposition, operational scale, cost efficiency and the potential for expansion, all of which are largely influenced by the geographical location of the company. This theory can be applied to a range of sectors beyond business, such as religious organizations and their mission work, as it has the potential to provide insight into the strategic decisions made regarding location and the subsequent impacts of these decisions.

In the context of the establishment of the Diocese on the Niger, the CMS’s decision to plant the first indigenous mission in Igboland could be analyzed using the Geographic Strategy Theory (Gray and Sloan, Reference Gray and Sloan2014). It offers a plausible explanation for the choice of location. The Eastern region of Nigeria, where the diocese was established, was known to be economically robust, signifying a potentially high capacity for funding the missionary work and sustaining the Church’s operations. This aligns with the theory’s emphasis on the influence of geographic location on the operational scale and potential for growth. Moreover, the Eastern region of Nigeria, as it existed prior to 1960, was an economic hub that offered the CMS fertile ground for evangelization and the capacity to scale their mission. The readiness of the local population to accept and engage with the new faith represents the ‘value proposition’ aspect of the theory. If the location is receptive to the CMS mission’s message, it enhances the potential for successful evangelism and church growth. Lastly, the choice of location could also be viewed in terms of strategic expansion. Situating the mission in the Eastern region could have been seen as a strategic move to establish a foothold in an area that was less dominated by Muslim influence compared to other parts of West Africa.

Therefore, the strategic location of the Diocese on the Niger in Igboland should not be viewed as a hasty, politically motivated decision. Instead, it was the result of thoughtful deliberation by those seeking to establish an Anglican foothold in the West African region, particularly amid the rise of the Muslim population (Reichmuth, Reference Reichmuth2019). The historical positioning of the Diocese on the Niger in the Eastern region – prior to the establishment of other dioceses in West Africa – also lends credibility to the ‘divine providence’ argument, suggesting that it could indeed have been a part of God’s plan. However, it also showcases the judicious geographical and economic strategy adopted by the CMS, painting a more nuanced picture of the past, as we shall see in subsequent paragraphs.

Value Proposition and Readiness to Engage with Other Cultures

As we conceptualize the trajectories using the Geographic Strategy Theory (Gray and Sloan, Reference Gray and Sloan2014), we explore the intricacies behind the CMS’s choice to establish the first indigenous West African diocese in the Eastern part of Nigeria, now known as the Diocese on the Niger. Contrary to a divine act of providence, we posit that the decision was an intelligent strategy considering the area’s unique value proposition at that time. Notably, the Eastern region was socioeconomically vibrant and demonstrated greater receptivity to Christianity, which presented a more fertile ground for missionary expansion compared to the Muslim-majority Western region Footnote 6 (Reichmuth, Reference Reichmuth2019; Okwu, Reference Okwu2010).

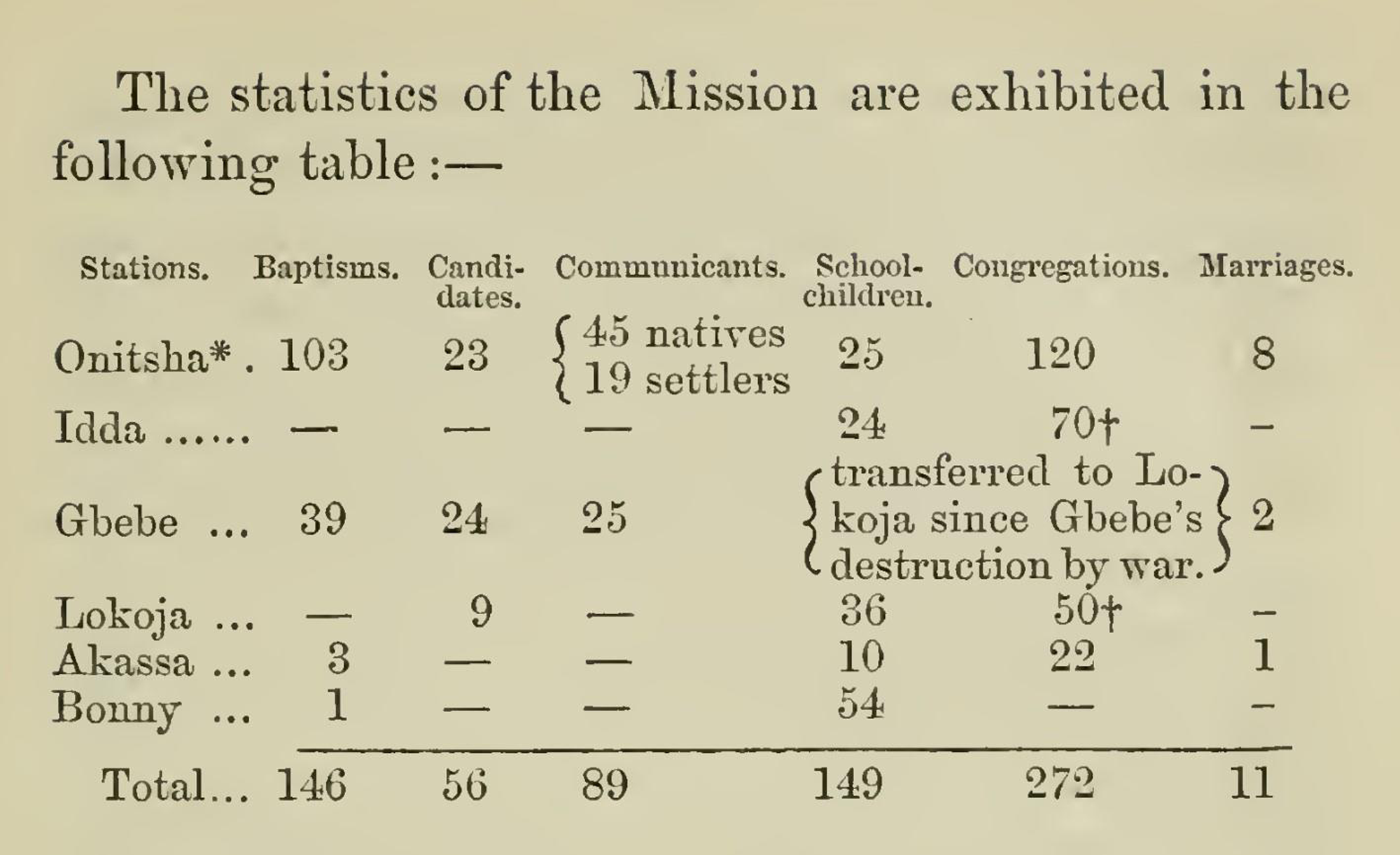

A detailed analysis of Crowther’s report (Reference Crowther1866; see Figure 1) indicates that the CMS saw in the Eastern region a promising hub for conversion, membership and active participation in church life, given the evident progress in the Niger Mission. For instance, in 1871, Crowther emphasized the need for the establishment of industrial schools, indicating the mission’s rapid progress. Footnote 7 Conversely, Stock (Reference Stock1899) and Tugwell (1919) Footnote 8 chronicled the challenges faced by the Yoruba Mission, which lacked resident European Interior missionaries for several years, hampering its growth and development. Peel (Reference Peel2000) Footnote 9 corroborated this narrative, further underscoring the strategic advantage of the Eastern region over the Western counterpart (also see Crowther’s statistics in Figure 1). Footnote 10

Figure 1. Statistics of the CMS mission in Nigeria by Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther (Crowther, Reference Crowther1866, p. 13).

In analyzing the aforementioned dynamics, we draw parallels with the words of Jesus in Lk 9.5, alluding to the strategic need to focus on regions more receptive to the message. This is further corroborated by the work of Akinfenwa (Reference Akinfenwa2021), who narrates the failed efforts to spread Christianity to the north and the challenges in gaining significant traction in the Western region. Thus, it becomes clear that the Eastern region’s receptivity to the Christian message was a critical factor behind the establishment of the first diocese in present-day Eastern Nigeria.

Furthermore, the Eastern region represented a fertile ground for the spread of the gospel with no significant religious competition, unlike the Western region, where Islam was well established (Reichmuth, Reference Reichmuth2019; Sanneh, Reference Sanneh2015; Soares, Reference Soares2014). Ayandele (Reference Ayandele1973) and Okwu (Reference Okwu2010) report that this region was perceived as safe for missionaries to work and expand their base (at least during the colonial era). In contrast, Islam’s presence in the Western and Northern regions was seen as a significant hindrance to the spread of Christianity, leading the CMS to make fewer inroads in these regions (Akinfenwa, Reference Akinfenwa2021; Reichmuth, Reference Reichmuth2019). Therefore, based on the Geographic Strategy Theory (Gray and Sloan, Reference Gray and Sloan2014), the establishment of the first indigenous West African diocese in the Eastern part of Nigeria was not merely a product of divine providence but rather a strategic decision, considering the region’s unique value proposition. It seems that the missionaries carefully evaluated the geographical, socioeconomic and religious factors and deemed the Eastern region as the most promising terrain for the establishment of the first indigenous Anglican diocese in West Africa.

A Foothold to Scale CMS Operations in Muslim-dominated West and North

In the context of the geographic strategy theory, the Church Missionary Society (CMS) seemed to find fertile ground for expansion in the pre-1960 Eastern region of Nigeria, mainly Igboland, considering the area’s unique socio-cultural characteristics and geographic advantages. Contrasted with the Western region marked by Islamic dominance, the Eastern region was identified for its progressive views and existing commercial infrastructure, Footnote 11 making it a promising terrain for the growth of the CMS operations (Adiele, Reference Adiele1996). Onitsha, located in Igboland, served as a strategic linchpin for the missionary activities, earning endorsements from historical figures like Ajayi Crowther, Macgregor Laird, and William Balfour Baikie (Adiele, Reference Adiele1996). It was celebrated not only as a vibrant commercial hub but also as a missionary epicentre. Footnote 12 From a geographic strategy perspective, Onitsha’s network of roads, described as ‘wonderful’ by Bishop Tugwell, was a major asset, enabling efficient movement and outreach compared to the disjointed infrastructure in the Yoruba region. Footnote 13

The sociocultural characteristics of the Igbos also played a pivotal role in the CMS strategy. The Igbos’ migratory patterns (within the borders of Igbolands), their thirst for education, and their ‘self-initiative’ ideology were all factors that complemented the geographical advantages and presented a compelling case for the CMS’s expansion in this region (Kanu, Reference Kanu2019; Ayandele, Reference Ayandele1973). In the interplay of demographic variables, individuals of diverse age, sex and status in Igboland demonstrated receptivity towards the CMS’s mission, reinforcing the potential for an extensive operational base (Isichei, Reference Isichei1970).

Despite the subsequent economic rise of the Western region, the historical, geographical and socio-cultural merits of the Eastern region prompted the CMS to establish the first indigenous diocese there. This decision was made in light of the strategic implications for the spread of Christianity and the potential for further operational growth in West Africa (Ikpeze, Reference Ikpeze, Amadiume and An-Na’im2000; Kansese, Reference Kansese2021; Onuoha, Reference Onuoha2018). The post-1967 scenario, marked by the Western region’s economic ascendancy due to the catastrophic impact of the Nigeria-Biafra war on Igbos, does not eclipse the historical relevance of Igboland in the CMS’s geographic strategy. Hence, the nuances of the CMS mission in Igboland are essentially rooted in geographic strategy theory, which stresses the strategic importance of geographical and sociocultural attributes in shaping the course of missionary activities in West Africa.

The Problem of Contested History in the Church of Nigeria, Anglican Communion: A Mirror of Political Divisions in Nigeria

Historically, Igboland, with its kingdoms such as Nri and Onitsha, played a significant role in West Africa’s rich history (Afigbo, Reference Afigbo1981; Chuku, Reference Chuku2005). Its inhabitants, the Igbo people, had a strong reputation as traders, and established commerce networks along the Niger banks. Footnote 14 While these commerce networks initially attracted European colonial powers, it was the unique receptivity of the Igbo people to the Christian message that resulted in significant conversions and ultimately led to the establishment of Christianity in this region. The trade routes in the region served as an initial point of contact, but the progressive values of the Igbos fostered a favourable environment for Christian missionaries to put down roots.

The openness of the Igbos to engage different cultures was evidenced in the substantial conversion to Christianity, establishing the Niger region’s indigenous Christian majority and setting the stage for the CMS’s successful mission in the mid-1800s (Okwu, Reference Okwu2010; Ayandele, Reference Ayandele1973). However, the dynamics shifted post-independence, notably influenced by the Nigeria-Biafra War of the late 1960s. With Nigeria’s independence from the British in 1960, the Eastern region, predominantly Igboland, stood as an economically vibrant hub. The Nigeria-Biafra War, however, ushered in an era of slowed growth and development for the region. The war was the consequence of Biafra, largely inhabited by ethnic Igbos, attempting to establish a separate state due to widespread marginalization (Ikpeze, Reference Ikpeze, Amadiume and An-Na’im2000).

Tensions leading up to the Nigeria-Biafra war were notably documented by scholars like Achebe (Reference Achebe2012), who detailed the political, regional and ethnic disparities that compounded over time in Nigeria. For example, Achebe (Reference Achebe2012) argued that this marginalization has its roots in the colonial era and was exacerbated by post-independence political developments. The British colonial administration amalgamated disparate regions into a single entity in 1914, largely disregarding Nigeria’s rich ethnic diversity (Falola and Heaton, Reference Falola and Heaton2008). This centralization of power, which often favored the Hausa-Fulani in the north due to their existing administrative structures, unwittingly set the stage for future inter-ethnic tensions (Lynch, Reference Lynch2012). After Nigeria gained independence in 1960, power struggles between the country’s three major ethnic groups – the Hausa-Fulani, Yoruba and Igbo – became pronounced. Many scholars argue that the Igbo, who were significant in the fight for independence, became politically marginalized (Achebe, Reference Achebe2012; Okwuosa et al., Reference Okwuosa, Nwaoga and Uroko2021). The political instability of this period culminated in a coup in 1966, led predominantly by Igbo officers, which resulted in anti-Igbo pogroms in the north (Achebe, Reference Achebe2012). This culminated in the Igbo people, primarily inhabiting the Eastern region, becoming increasingly marginalized, thereby fueling their desire for independence. However, the war itself, which lasted from 1967 to 1970, led to devastating consequences for the Igbo people (Falola and Heaton, Reference Falola and Heaton2008). The loss of the war was not only a political and military setback but also inaugurated a period of increased hardship and vulnerability for the Igbo people.

In the Nigeria-Biafra war’s aftermath, numerous legislative acts were enacted, some of which directly impacted the Igbo people’s socio-economic standing. The Public Officers (Special Provisions Decree no. 46 of 1970), as noted by the Federal Ministry of Information (1971), led to the dismissal or compulsory retirement of many Igbo officers who participated in the civil war on Biafra’s side. Contrary to earlier assurances, these officers were not reabsorbed into their former positions, an act that further compounded the sense of alienation and disenfranchisement amongst the Igbo people. Further economic marginalization was brought about by the Banking Obligation (Eastern States Decree) and the Indigenisation Decree of 1972. The former subjected banks in the Igbo region to pay all account owners a flat rate of 20 pounds, irrespective of the original account balance prior to the war (Okwuosa et al., Reference Okwuosa, Nwaoga and Uroko2021). The latter provided Nigerians an opportunity to participate in the country’s productive enterprises. However, due to their socio-economic condition postwar, many Igbo people felt alienated from this development (Afigbo, Reference Afigbo1981). Additionally, the Abandoned Property Policy, which allowed for the confiscation of properties left behind by Igbo people who fled during the war, was seen as an economic attack on them (Akolokwu, Reference Akolokwu2012).

In the wake of these economic, political and social challenges, the Igbo people were confronted with a crisis of faith. The war, which they had termed Oguejiofo (the war of justice and truth), was fought with deep faith in the principle of justice and truth (Ezeanya, Reference Ezeanya1967). The loss of the war led to a religious vacuum and a faith crisis amongst the Igbo people (Okwuosa et al., Reference Okwuosa, Nwaoga and Uroko2021; Ugwu, Reference Ugwu2014). This complex history has significantly shaped the narrative of the Igbo people, both within Nigeria’s socio-political landscape and within the Church’s role in their community. Understanding these nuances is crucial for appreciating the enduring legacies of the Igbo people.

The tendency to diminish or even dismiss the significance of history and heritage is not confined to the political sphere; it is also encroaching upon religious institutions. As social scientists and theologians, our objective in this paper is to bring awareness to the Diocese on the Niger’s disputed legacy within the broader Church of Nigeria Anglican Communion, which are essential steps towards addressing these broader issues. The complexity of the contested history framework mirrors the dynamics within the Anglican Church in Nigeria. This framework speaks to how disputes over historical narratives serve to establish ‘political legitimacy’ or ‘social hierarchy’, invariably linked to the pursuit of truth (Hatavara, Reference Hatavara2012; Schär and Sperisen, Reference Schär and Sperisen2010). In Nigeria, such contests are visible in the myriad societal layers (ethnic, political, religious), where narratives of political marginalization and economic deprivation are prominent (Kansese, Reference Kansese2021).

Theological Implications

In addressing the theological implications of arguments made in this paper, one must contend with the Christian mandate to uphold unity, empathy and reconciliation within a diverse and historically complex community. St. Paul’s theology, particularly his metaphoric description of the Church as the ‘Body of Christ’ (1 Cor. 12.12-27), becomes central to this reflection. As Christians, we are called to promote healing and unity within our communities. However, the scars of history, particularly for marginalized groups such as the Igbo, demand a reckoning. These legacies, imbued with pain and suffering, must be confronted and processed within the Christian community, which must act as a place of healing rather than suppression (Johnson, Reference Johnson2017).

Scholars such as Volf (Reference Volf1996) emphasize the importance of embracing the past within the process of reconciliation. This does not mean forgetting the injustices done or the pain suffered. Instead, it involves remembering in a way that acknowledges the harm done and seeks to heal the wounds inflicted. This dynamic is particularly vital within the Church, where unity is not just a sociopolitical construct but a theological imperative. The Nigerian Church, with its diverse ethnic composition, is uniquely positioned to address the historical grievances and prevent marginalization of the Igbo. By engaging with this contentious past, the Church can model Christ-like empathy and promote healing (Akinade, Reference Akinade2010).

Confronting these contested legacies is a challenging task. However, the Church’s mandate necessitates this difficult process, making the distinction between the ‘Body of Christ’ and the ‘Corpse of the World’. This separation, as described by Bonhoeffer (Reference Bonhoeffer and John1954), implies that, unlike the world which is characterized by division and strife, the Church, as the Body of Christ, must model unity and reconciliation. Thus, it becomes the task of the Church in Nigeria, and indeed the global Christian community, to foster environments where such conversations can occur – not to reopen old wounds, but to apply the healing balm of Christ-like love and understanding (Villa-Vicencio, Reference Villa-Vicencio2009).

However, it is equally important that these theological reflections translate into practical actions. A theology of unity, while conceptually robust, must be operationalized within the Church’s structures, practices and teachings. As Nigerian theologian Oborji (Reference Oborji2005) suggests, the Church must continually strive to embody a community of equality, justice and love, demonstrating in concrete ways the theological tenet of the Body of Christ.

Conclusion

In conclusion, understanding the marginalization of the Igbo people requires more than just historical analysis; it demands an exploration of a complex tapestry woven with theological, sociopolitical and cultural threads. The Church has the potential to act as an effective platform, fostering an environment that values diversity, encourages dialogue and heals historical wounds, thus advancing towards the theological ideal of unity in Christ. We cannot overlook the historical significance of the Diocese on the Niger as the first indigenous Anglican Diocese in the former Western Equatorial Africa. However, this understanding must be viewed through a larger lens that encompasses social and political forces shaping identities and influencing interests within the Church and the broader Nigerian society. Disputes over the diocese’s legacy are not isolated disputes, but reflections of societal rifts birthed from the Nigeria-Biafra war, sectarianism, ethno-religious divisions, regionalism and patterns of ethnic dominance. They are further exacerbated by issues of class and politics, alongside deep-seated social inequality. Therefore, achieving reconciliation and laying to rest the contested legacy of the Diocese on the Niger involves addressing these endemic societal divisions and structural inequalities. It is important, for the most part, to acknowledge how different groups conceptualize their histories, perceive their roles in nation-building, and understand their lived experiences.

While fostering open dialogue on these matters can be challenging and sometimes divisive, such discourse is instrumental in promoting reconciliation and facilitating inclusive nation-building, not only in Nigeria but within the global Anglican Communion. We therefore warmly invite commentaries on the discussions raised in this document. It is our hope to foster an ongoing dialogue, one that we would willingly contribute to by addressing any contested points or alternate viewpoints presented in response to this paper. We believe that through collective discourse, we can address these critical issues and further enrich the nuanced understanding of our shared history. It is through this dialectical process that the prevailing narrative regarding the Igbo’s legacy can be challenged, thereby addressing the societal backdrop contributing to their continued economic and social disenfranchisement. As we grapple with this past together, the Church and the wider society can lay a foundation for a more inclusive, equitable and unified future.