Introduction

Capsicum annuum is the most widely cultivated and versatile Capsicum species, and is commonly used as both a vegetable and a spice (Fári Reference Fari1986). Variants of C. annuum include chile pepper, which is grown as both green and red fruits, with each fruit type sold in both fresh market and processed forms (Walker and Funk Reference Walker and Funk2014). In 2023, New Mexico accounted for approximately 45% of chile pepper production in the United States, ranked second among chile pepper-producing states, and produced a total of 46,410 Mg of chile pepper, resulting in an overall production value of US$41.5 million (USDA-NASS 2023). Of this total, chile pepper for processing accounted for US$34.2 million, and chile pepper for the fresh market accounted for US$7.3 million (USDA-NASS 2023).

Weeds in chile pepper can severely reduce production profitability. If not controlled, weeds can lower crop yields and decrease the efficiency of harvesting operations. For instance, infestations of spurred anoda [Anoda cristata (L.) Schltdl.] that emerge during the latter portion of the chile pepper growing season (9 wk after chile pepper seeding) reduce chile pepper yield by 31% (Schroeder Reference Schroeder1993). Late-season infestations of tall morningglory [Ipomoea purpurea (L.) Roth] increase the amount of time required for hand-harvesting chile pepper (Schutte Reference Schutte2017). Furthermore, weeds can serve as hosts for pathogens that cause diseases (Rodriguez-Alvarado et al. Reference Rodriguez-Alvarado, Fernandez-Pavia, Creamer and Liddell2002; Sanogo et al. Reference Sanogo, Schroeder, Thomas, Murray, Schmidt, Beacham and Liess2013) and can produce seeds and propagules that contribute to infestations in crops planted afterward (Schutte Reference Schutte2017).

Management of broadleaf weeds is a primary challenge in chile pepper production because, in part, the availability of herbicides for controlling broadleaf weeds is limited. Consequently, hand hoeing is a common practice in controlling broadleaf weeds in chile pepper. This method of weed control is labor-intensive and costly, and significantly reduces the profitability of chile pepper production in New Mexico (Daramola et al. Reference Daramola, Adigun and Adeyemi2021; Funk and Walker Reference Funk and Walker2009). Cultivation can help control weeds between chile pepper rows; however, cultivation is generally ineffective against weeds that grow within or near the crop rows. Weeds in and near vegetable crop rows can be managed with synthetic or natural mulches (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Kolb, Leslie and Hooks2017), but mulches are not widely used in New Mexico chile pepper production. One particularly troublesome broadleaf weed is Wright groundcherry [Physalis acutifolia (Miers) Sandw.]. This species is not only common in commercial chile fields in southern New Mexico (Insa et al. Reference Insa, Schutte and Lehnhoff2024), but it is also phylogenetically related to chile pepper (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Sun, Wang, Zhu, Ayhan, Yi, Yan, Zhang, Meng, Mu, Li, Meng, Bian and Wang2024), which complicates chemical control due to the risk of crop injury.

A previous study determined that broadleaf weeds and hand hoeing time in chile pepper are reduced by false seedbeds implemented the summer prior to chile pepper seeding (Schutte et al. Reference Schutte, Sanchez, Beck and Idowu2021). These “fallow-season false seedbeds” work by stimulating germination of troublesome broadleaf weeds, then eliminating all subsequent broadleaf weeds before they reach reproductive maturity. Although fallow-season false seedbeds may be a method for reducing reliance on hand hoeing in chile pepper, fields treated with fallow-season false seedbeds lack vegetative cover for an extended period. Such fields are susceptible to wind erosion (Siddoway et al. Reference Siddoway, Chepil and Armbrust1965), which is a persistent threat to agricultural sustainability in the southwestern United States. Also, during false seedbed procedures, fields are not producing financial income, which may limit adoption of this method for weed seedbank reduction (Llewellyn et al. Reference Llewellyn, Pannell, Lindner and Powles2006).

One potential strategy for reducing field susceptibility to wind erosion and improving farm profits during weed seedbank reduction is to grow a rotational, warm-season grass crop in ways that both encourage weed seed germination and permit techniques for termination of subsequent weed seedlings. Sorghum is a warm-season grass crop that can be cultivated for grain or forage and is particularly well-suited for semiarid environments like New Mexico because it produces large amounts of biomass with limited water, which thus reduces the need for irrigation (Marsalis Reference Marsalis2011). In New Mexico, sorghum is conventionally grown in rows spaced 15 to 51 cm apart (Marsalis Reference Marsalis2011). However, when grown for weed seedbank reduction, sorghum may need to be sown in rows spaced farther apart than conventional practice. This is because sorghum grown with relatively narrow row spacing can rapidly develop a canopy that intercepts high percentages of photosynthetically active radiation (Kukal and Irmak Reference Kukal and Irmak2020), which inhibits weed seed germination (Pons Reference Pons and Fenner2000). To terminate broadleaf weeds in sorghum, farmers can apply nonresidual, postemergence herbicides such as bromoxynil, fluroxypyr, and 2,4-D (Marsalis Reference Marsalis2011; Pannacci and Bartolini Reference Pannacci and Bartolini2018). Residual herbicides such as atrazine and halosulfuron can also be applied to sorghum; however, plant-back restrictions often prevent applications of residual herbicides to sorghum grown before chile pepper (Gowan 2017; Syngenta 2021). Such restrictions may be consequences of the potential for harm to chile pepper seedlings or the absence of residue data needed for maximum residue limits in a food crop like chile pepper.

Efficient use of herbicides applied to sorghum crops to reduce weeds in subsequent chile pepper crops requires knowledge of the relationship between the number of herbicide applications to sorghum and the economic benefits across sorghum and chile pepper growing seasons. Multiple applications of herbicides when sorghum is being grown may reduce weed densities in the subsequent chile pepper crop; however, multiple herbicide applications may not be necessary if just one herbicide application provides benefits that are equivalent to multiple applications. To collect information to support the efficient use of herbicides in sorghum production, this study aimed to determine broadleaf weed density and hand hoeing time responses in chile pepper to the following two treatments with nonresidual, postemergence herbicides applied to sorghum: 1) a premix combination of bromoxynil, fluroxypyr, and 2,4-D applied at the 4-leaf stage of sorghum; and 2) the same premix combination of bromoxynil, fluroxypyr, and 2,4-D applied at the 4-leaf stage of sorghum, followed by an application of bromoxynil at the 6-leaf stage of sorghum. In addition, this study compared the two herbicide treatments for the net economic benefits across sorghum and chile pepper growing seasons.

Material and Methods

Experimental Site

Field studies were conducted during 2022 to 2023 and 2023 to 2024 at the New Mexico State University Leyendecker Plant Science Research Center near Las Cruces, New Mexico (32.202005°N, 106.745282°W). The soil at the study site, averaged across both study years, consisted of 23% sand, 40% silt, and 37% clay, with 1.9% organic matter. It is classified as Belen clay loam (clayey over loamy, montmorillonitic [calcareous], thermic Vertic Torrifluvent) (USDA-NRCS 2023). Study sites were in chile pepper production in years immediately prior to study initiation. Accordingly, the soils were expected to include large numbers of broadleaf weed seeds. Irrigation at the study site consisted of surface flooding during sorghum seasons, and flood-furrow during chile pepper seasons.

Experimental Design

The experiment was designed as a randomized complete block with four replications. Experimental plots were 4 m wide by 12 m long and contained four rows of chile pepper. Treatments included 1) a nontreated control (sorghum planted, no weed control after sorghum seeding); 2) one herbicide application to sorghum (a premix combination of 2,4-D [0.35 kg ai ha−1] + bromoxynil [0.35 kg ai ha−1] + fluroxypyr [0.14 kg ai ha−1] applied at the 4-leaf stage); 3) sorghum with two herbicide applications (the aforementioned premix combination followed by bromoxynil [0.28 kg ai ha−1] applied at the 6-leaf stage); and 4) a weed-free control (sorghum with hand hoeing as needed for complete weed control). The two-application treatment included bromoxynil because label restrictions prevent repeated applications of the premix combination (Winfield 2016). The two herbicides used in the study were Kochiavore (Winfield Solutions, Arden Hills, MN), which consists of bromoxynil (0.200 kg ai L−1) + fluroxypyr (0.080 kg ai L−1) + 2,4-D (0.200 kg ai L−1); and Moxy 2e (Winfield Solutions), which consists of bromoxynil (0.240 kg ai L−1). Herbicides were applied using a CO2-powered backpack sprayer calibrated to deliver 187 L ha–1 and equipped with flat-fan nozzles (TeeJet 8002VS; TeeJet Technologies, Glendale Heights, IL). The spray nozzle height was kept above the sorghum canopy.

Sorghum Management

Prior to planting sorghum (Pearl cultivar) in the summers of 2022 and 2023, the experimental area was tilled and laser-leveled to a grade of 0.01% to 0.03% to facilitate proper irrigation and drainage. Because sorghum was grown to promote emergence of broadleaf weeds, it was planted in widely spaced rows (1 m between adjacent rows) and not fertilized to minimize weed suppression from the crop canopy. Sorghum was sown using a mechanical planter (MaxEmerge Plus; John Deere, Moline, IL) at a seeding rate of 6.75 kg ha−1. Dates of sorghum management activities are provided in Table 1.

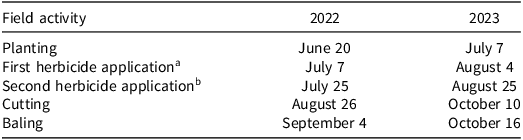

Table 1. Dates of sorghum season activities.

a The first treatment consisted of a premix combination of 2,4-D (0.35 kg ai ha−1) + bromoxynil (0.35 kg ai ha−1) + fluroxypyr (0.14 kg ai ha−1) applied at the 4-leaf stage.

b The second treatment consisted of bromoxynil (0.28 kg ai ha−1) applied at the 6-leaf stage.

After seeding, fields were irrigated via surface flooding to a depth of 7.62 cm at each irrigation event. In total, sorghum fields were irrigated four times throughout each of the growing seasons. Following the first irrigation, annual grass weeds were controlled with clethodim (Clethodim 2 EC, 0.093 kg ai L–1; Direct AG Source, Eldora, IA) applied at 0.42 kg ai ha−1 to row middles at 2 to 3 wk after sorghum seeding using a CO2-powered backpack sprayer equipped with a hooded nozzle. At the end of the sorghum seasons, sorghum aboveground biomass was swathed using a tractor-mounted swather (Hesston 8200; Massey Ferguson, Hesston, KS) and left in the field for 1 wk to dry before baled using a mechanical baler (Hesston 4570; Massey Ferguson).

Sorghum Season Data Collection

One week before sorghum harvest, the broadleaf weed cover was assessed using the point intercept method (BLM 1996). Transects spanned the entire length of each plot. Broadleaf weed cover was measured at 0.1-m intervals by identifying plants that contacted a wire stake positioned at each sampling location. Aboveground sorghum biomass was harvested from two 0.25-m2 quadrats within each plot. Biomass samples were oven-dried for 5 d at 35 C and then weighed.

Chile Pepper Management

Chile pepper was grown in the same fields where the sorghum was grown. Field preparation for chile pepper followed standard practices that involved tilling and forming raised beds spaced 1 m apart. Chile pepper (Sandia cultivar) was seeded at a rate of 6.15 kg ha−1 to a depth of 2 cm using a mechanical planter (MaxEmerge Plus; John Deere, Moline, IL). Dates of management activities for chile pepper are presented in Table 2. After seeding, napropamide (Devrinol 2XT, 0.13 kg ai L−1; United Phosphorus, Inc., Mumbai, India) was applied preemergence and mechanically incorporated using a ring roller. The fields were then fertilized and irrigated.

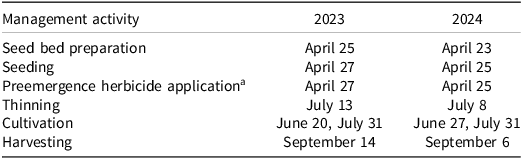

Table 2. Dates of major management activities during chile pepper growing seasons.

a Napropamide at 2.24 kg ai ha−1.

Chile Season Data Collection

Beginning 4 wk after chile pepper seeding, weed densities were determined by identifying weeds to species, counting, and removing them from two 0.25-m2 quadrats within the middle two rows of each plot. Weed counts from the two quadrats were summed to obtain a single density value per plot for each sampling date. Immediately after recording weed densities, the time required for one person to hand-hoe a 12-m2 section of a plot was measured. Hand hoeing time was measured only in the middle two rows of a plot, with each row hand-hoed over a 6-m length. Weed density data were collected at 2-wk intervals until 2 wk before harvesting. In the 2023 chile pepper season, weed density data were collected six times and hand hoeing time data were recorded five times, because hand hoeing was not needed early in the growing season. During the 2024 season, both weed density and hand hoeing time data were collected seven times throughout the season. At the end of each season, both broadleaf weed density and hand hoeing time data were summed to determine the cumulative broadleaf weed density and hoeing time for each plot.

Marketable green chile pepper fruits, defined as mature peppers that met size, shape, and quality standards (USDA-AMS 2007), were harvested by hand from 12-m sections of crop row in each plot. The harvested fruits were weighed in the field to determine their fresh weight.

Data Analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using R software (v.4.3.1; R Core Team 2023). Year-by-treatment interactions for broadleaf weed cover and sorghum biomass at sorghum cutting were evaluated using ANOVA. Results indicated the interaction between year and treatment was not significant for broadleaf weed cover (P = 0.372) or sorghum biomass (P = 0.407). Therefore, the data from 2022 and 2023 were combined. To assess the effects of treatment on broadleaf weed cover and sorghum biomass at sorghum cutting, data were analyzed using ANOVA. The models included treatment, replicate in year, and year as predictor variables. Post hoc comparisons of treatment means were conducted with a Fisher LSD test with Bonferroni-adjusted P-values, using the agricolae package in R.

For response variables collected during the chile pepper season, including broadleaf weed density, hand hoeing time, and fruit yield; data were combined across years after confirming that there were no significant year-by-treatment interactions. This was determined using ANOVA for each response variable. The interaction between year and treatment was not significant for cumulative broadleaf weed density (P = 0.108), hand hoeing time (P = 0.737), and chile pepper yield (P = 0.793).

Treatment effects on broadleaf weed density were assessed using generalized linear models with negative binomial distributions, implemented via the R package mass. In these models, treatment, replication in year, and year were included as predictor variables. Pairwise comparisons of estimated marginal means were performed using the emmeans package in R with Bonferroni-adjusted P-values. The estimated marginal means were back-transformed from the log scale for presentation in the results. Treatment effects on hand hoeing time and chile pepper yield were evaluated using ANOVA models that included treatment, replicate in year, and year as predictor variables. Post hoc comparisons of treatment means were conducted using the Fisher LSD test with Bonferroni-adjusted P-values.

Net Economic Benefits for Sorghum Herbicide Programs

The partial budget analysis included relevant costs and income based on prices presented in regional crop enterprise budgets (NMSU 2024a, 2024b). Gross revenue for sorghum was estimated by averaging plot-level biomass data across years, scaling the mean values to a per hectare basis (in tons), and multiplying by the market price of US$185 ton−1 for sorghum hay (NMSU 2024b). For chile pepper, gross revenue was calculated using plot-level fruit yield data and a market price of US$711 ton−1 (NMSU 2024a).

Weed control costs for sorghum were calculated by adding the costs of herbicide products and tractor operations during herbicide applications. Herbicide costs were based on retail prices from local agricultural suppliers: a premix combination of 2,4-D, bromoxynil, and fluroxypyr (US$27.52 ha−1) and bromoxynil alone (US$27.79 ha−1). Tractor operation costs (US$45.15 ha−1) were obtained from a regional crop enterprise budget (NMSU 2024b) and included labor, fuel and lubrication, repairs, and fixed costs. For chile pepper, weed control costs were determined by multiplying hand hoeing times by the hourly wage rate of US$16.77, as specified in the regional crop enterprise budgets (NMSU 2024a). Costs that did not differ between treatments—such as irrigation, cultivation, and baling—were excluded from the partial budget analysis because they would not affect the comparison of net economic benefits between herbicide treatments. For each herbicide treatment, net benefit was calculated as the using the following formula:

where total gross revenue is the sum of sorghum and chile pepper revenue, and total weed control cost is the sum of sorghum and chile pepper weed control costs.

Results and Discussion

Sorghum Season

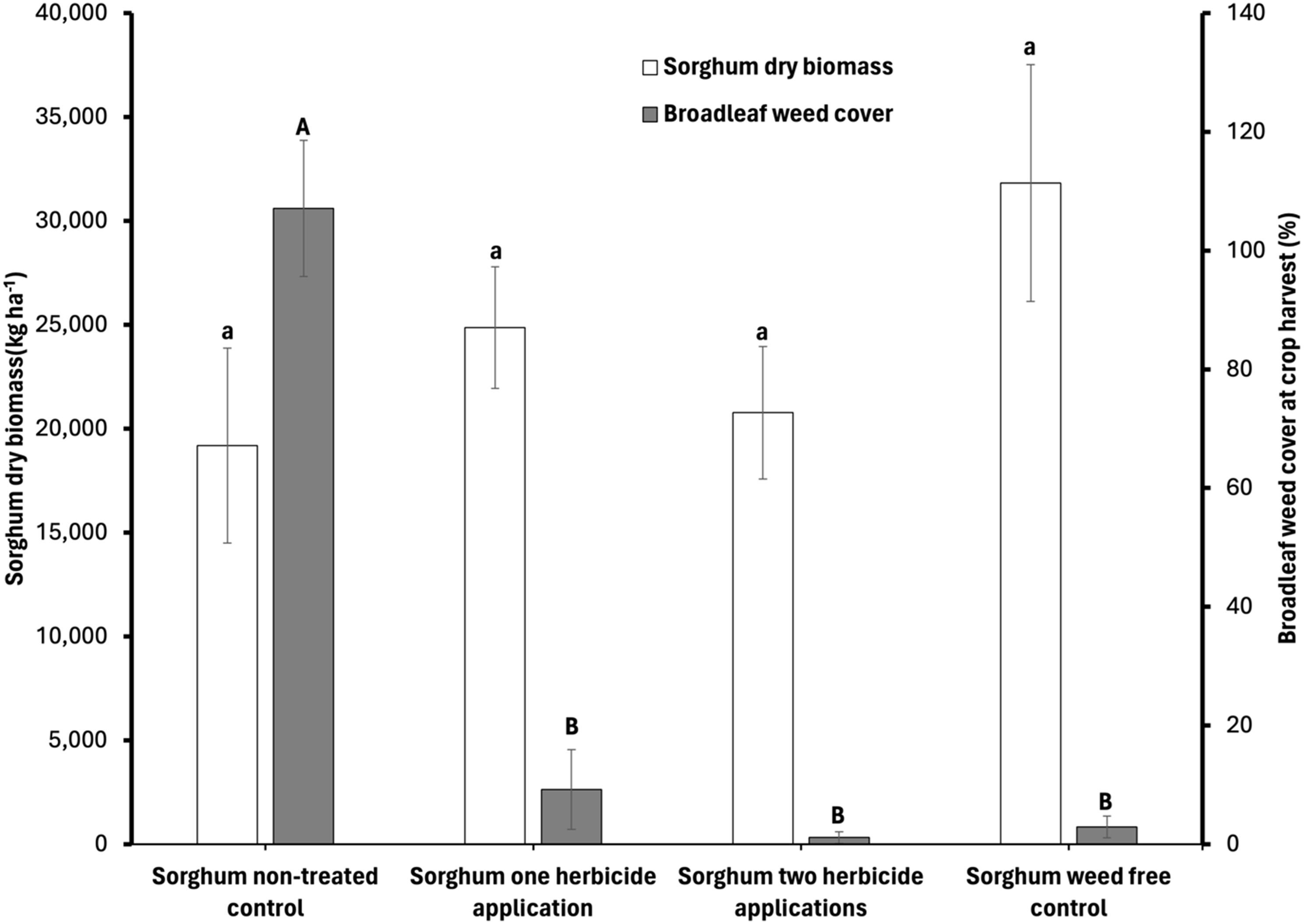

Broadleaf weed cover was greatest in the nontreated control plots (P < 0.05, Figure 1). In those plots, weed cover values exceeding 100% were consequences of the point-intercept method used in this study. In the point-intercept method, if more than one species is present at a single point, each species is counted separately, which can cause total cover to exceed 100%. Broadleaf weeds found among sorghum at cutting in the nontreated control plots included spurred anoda [Anoda cristata (L.) Schlecht], Wright groundcherry [Physalis acutifolia (Miers) Sandw.], Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri S. Watson), tall morningglory [Ipomoea purpurea (L.) Roth], ground spurge (Euphorbia prostrata Aiton), and common purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.).

Figure 1. Aboveground dry biomass of sorghum and broadleaf weed cover when sorghum was cut. Values are estimated marginal means from analyses of variance using data combined from 2022 and 2023. Means with the same letter are not different (Fisher LSD, Bonferroni-adjusted P > 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error (n = 8). Broadleaf weed cover was estimated using the point intercept method, and sorghum biomass was collected from two 0.25-m2 quadrats per plot, oven-dried, and converted to kilograms per hectare (kg ha−1).

Broadleaf weed cover at sorghum cutting was low among the treatments with one herbicide application (8.6%), two herbicide applications (1%), and the weed-free control (2.7%) relative to the nontreated control plots (P > 0.05, Figure 1). These results are consistent with previous studies that determined bromoxynil, fluroxypyr, and 2,4-D controlled broadleaf weeds in various grass crops. For instance, bromoxynil reduced common sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.), velvetleaf (Abutilon theophrasti Medik.), and ivyleaf morningglory (Ipomoea hederacea Jacq.) density in sorghum (Rosales-Robles et al. Reference Rosales-Robles, Sanchez-de-la-Cruz, Salinas-Garcia and Pecina-Quintero2005). Fluroxypyr suppressed broadleaf weeds such as cleavers (Galium aparine L.), corn gromwell (Sinapis arvensis L.), wild hemp (Cannabis ruderalis Janisch.), and hairy vetch (Vicia villosa Roth) in winter barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) (Cristea et al. Reference Cristea, Ciontu, Jalobă and Grădilă2023). A tank mix of bromoxynil, fluroxypyr, and 2,4-D controlled kochia [Bassia scoparia (L.) A.J. Scott] in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) (Torbiak et al. Reference Torbiak, Blackshaw, Brandt, Hamman and Geddes2021).

Sorghum biomass at cutting was similar among treatments, with biomass ranging from 19,183 to 31,826 kg ha−1 (P > 0.05, Figure 1). However, the two-application treatment caused nonsignificant reductions in sorghum biomass, with sorghum producing 16.5% less biomass than sorghum that received the one-application treatment and 34.7% less than sorghum kept weed-free with hand hoeing. This is consistent with previous studies that determined bromoxynil can cause temporary injury to sorghum (Bajwa et al. Reference Bajwa, Nawaz, Farooq, Chauhan and Adkins2023; Rosales-Robles et al. Reference Rosales-Robles, Sanchez-de-la-Cruz, Salinas-Garcia and Pecina-Quintero2005), which was observed in this study (Supplementary Figure S1). Bararpour et al. (Reference Bararpour, Hale, Kaur, Singh, Tseng, Wilkerson and Willett2019) determined sorghum biomass was not reduced by postemergence herbicides such as quinclorac, atrazine, dimethenamid-P, S-metolachlor, dicamba, mesotrione, and prosulfuron when applied to sorghum at the V2 and V4 growth stages. However, none of the herbicides in the paper by Bararpour et al. (Reference Bararpour, Hale, Kaur, Singh, Tseng, Wilkerson and Willett2019) can be used in sorghum–chile pepper rotations because of plant-back restrictions.

Chile Pepper Season

During the 2023 chile pepper growing season, Wright groundcherry was the most abundant weed species, comprising 63% of the total weed species. Grasses, including junglerice [Echinochloa colona (L.) Link] and red sprangletop [Leptochloa panicea (L.) Nees], were the second most prevalent group, accounting for 26% of the total weed species. In the 2024 chile pepper growing season, grasses, including junglerice and red sprangletop, were the most abundant group of weeds, accounting for 52% of the total weed species. Wright groundcherry comprised 22% of the weeds counted in chile pepper in 2024, and 18% in 2024 were Palmer amaranth. The most abundant weed species in this study were commonly reported in surveys of commercial chile pepper fields in the Rio Grande Valley of southern New Mexico (Insa et al. Reference Insa, Schutte and Lehnhoff2024).

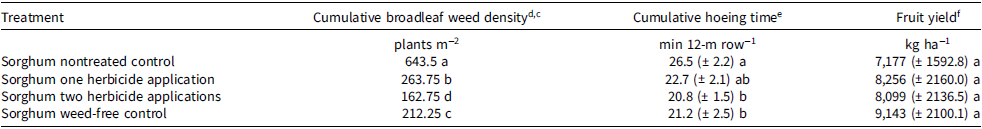

The cumulative density of broadleaf weeds in chile pepper was greatest in plots that were not treated with herbicide in the sorghum growing season (P < 0.05, Table 3). Presumably, the lack of weed control in sorghum led to relatively large weed seedbanks that persisted into the next crop. This hypothesis is consistent with previous studies that determined large deposits to weed seedbanks can increase future requirements for weed control (Ou et al. Reference Ou, Thompson, Stahlman and Jugulam2018; Taylor and Hartzler Reference Taylor and Hartzler2000).

a Data were combined across years prior to statistical analyses.

b For cumulative density of broadleaf weeds, values are marginal means from a negative binomial model.

c For cumulative hoeing time and fruit yield, values are marginal means from analyses of variance, with standard errors indicated by values in parentheses. Marginal means within a column followed by the same letter are not different at an alpha level of 0.05.

d Prior to each weed control event, weeds were identified to species, counted, and removed from two, 0.25-m2 quadrats within each plot. Broadleaf weeds observed in the chile pepper experiment included Wright groundcherry [Physalis acutifolia (Miers) Sandw.], Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri S. Watson), spurred anoda (Anoda cristata L.), common purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.), ground spurge (Euphorbia humistrata Engelm.), morningglory spp. (Ipomoea spp.), oakleaf thornapple (Datura quercifolia Kunth), prickly lettuce (Lactuca serriola L.), and London rocket (Sisymbrium irio L.).

e The amount of time required for one individual to hand hoe a 12-m2 section of crop row was determined for each hoeing intervention that occurred during the chile pepper season.

f Fresh weights of marketable green chile fruit were determined from 12-m sections of crop row and then converted to kg ha−1.

The cumulative density of broadleaf weeds in chile pepper was lowest in plots treated with the two-application treatment during the sorghum-growing season. Compared with the two-application treatment, the one-application treatment had 62% more broadleaf weeds in the chile pepper season. This result indicates that the second herbicide application when sorghum was being grown was needed for maximum reductions in broadleaf weed density in chile pepper. Hand hoeing time in chile pepper following sorghum treated with the two-application treatment was 21.5% lower than hand hoeing time when chile pepper was grown following a sorghum crop in which weeds were not controlled (Table 3). The mean hand hoeing time for plots treated with one herbicide application was numerically higher than for those treated with two herbicide applications; however the difference in hand hoeing time between the single and two application treatments was not significant. Chile pepper yield was similar across the sorghum weed control treatments (P > 0.05, Table 3), which indicates the various sorghum-season treatments primarily influenced weed management requirements, rather than directly impacting chile pepper yield.

The results from this study are consistent with those in previous studies indicating that crop rotation can significantly reduce weed populations. For example, crop rotations such as rice (Oryza sativa L.) and soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.], winter wheat and maize (Zea mays L.), and winter wheat and sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L. ssp. vulgaris) suppress weeds and improve crop yields (Koocheki et al. Reference Koocheki, Nassiri, Alimoradi and Ghorbani2009; Scherner et al. Reference Scherner, Schreiber, Andres, Concenço, Martins, Pitol, Shah, Khan and Iqbal2018). Crop rotations can contribute to weed management by providing opportunities for the application of different types of herbicides, which broadens the overall spectrum of control compared with herbicides available for a specific crop. By using rotation to change the types of herbicides used on the same plot of land, farmers can target annual weed species that are closely related to a crop by gradually reducing the weed seedbank (Ball Reference Ball1992; Derksen et al. Reference Derksen, Anderson, Blackshaw and Maxwell2002; Simard et al. Reference Simard, Rouane and Leroux2011). For chile pepper production in New Mexico, rotations with sorghum may help farmers manage Wright groundcherry and other troublesome broadleaf weeds and reduce labor requirements for weeding. Such reductions will help sustain production of chile pepper in New Mexico because labor availability and costs are major challenges for farmers in the state (Hawkes et al. Reference Hawkes, Libbin and Jones2008).

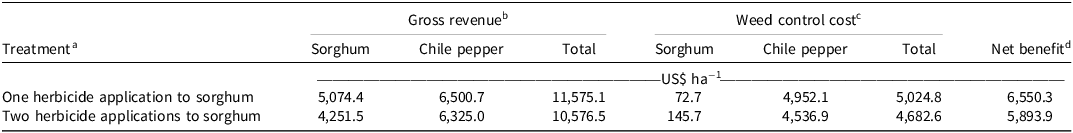

Net Economic Benefits for Sorghum Herbicide Programs

The partial budget analysis showed that the one-application treatment provided higher net economic returns compared with the two-application treatment (Table 4). Although the two-application treatment resulted in slightly lower weed control costs in chile pepper compared with the one-application treatment, the higher costs for herbicide application and the potential phytotoxicity to sorghum led to lower overall economic returns for the two-application treatment compared with the one-application treatment. These results suggest the one-application treatment, instead of the two-application treatment, is a more cost-effective strategy for using rotational sorghum to reduce weeds in subsequent chile pepper crops.

Table 4. Partial budget analysis comparing gross revenue, weed control cost, and net benefit for sorghum–chile pepper rotations under one- and two-herbicide applications to sorghum.

a The single herbicide treatment was a premix combination of 2,4-D (0.35 kg ai ha−1) + bromoxynil (0.35 kg ai ha−1) + fluroxypyr (0.14 kg ai ha−1) applied at the 4-leaf stage of sorghum. The two-herbicide treatment consisted of the premix combination followed by an application of bromoxynil (0.28 kg ai ha−1) at the 6-leaf stage of sorghum.

b Gross revenues were determined by multiplying yields (averaged across years). Market prices were obtained from regional crop enterprise budgets published in 2024 (New Mexico State University 2024a, 2024b).

c Weed control costs for sorghum were determined by adding expenditures for tractor operations during herbicide applications and herbicide product prices. Weed control costs for chile pepper were determined by multiplying hand hoeing times and hourly wages obtained from regional crop enterprise budgets published in 2024 (New Mexico State University, 2024a, 2024b).

d Net benefits were determined by subtracting total weed control costs from total gross revenues.

A previous study demonstrated the potential of fallow-season false seedbeds to reduce labor costs in chile pepper (Schutte et al. Reference Schutte, Sanchez, Beck and Idowu2021). The net economic benefit of fallow-season false seedbeds, which was calculated by adjusting the savings reported by Schutte et al. (Reference Schutte, Sanchez, Beck and Idowu2021) to reflect the values for wages and expenses used in this study, range from US$1,277 ha−1 to US$2,144 ha−1. Thus, fallow-season false seedbeds can increase economic returns in chile pepper. However, the net economic benefit of fallow-season false seedbeds may be less than rotational sorghum treated with the postemergence herbicides evaluated in this study.

It is important to note that this study did not include a treatment that lacked both sorghum and irrigation. Such a treatment would indicate chile pepper responses to weed seedbank reduction accomplished with irrigation implemented the summer prior to chile pepper seeding. Chile pepper responses to irrigation-induced weed seedbank reduction the summer prior to chile pepper seeding has been established (Schutte et al. Reference Schutte, Sanchez, Beck and Idowu2021). Thus, the purpose of this study was to evaluate different methods of weed seedbank reduction rather than to evaluate treatments with and without seedbank reduction.

Further research is needed to assess additional methods for weed control in sorghum and the broader implications of rotational sorghum on chile pepper production. Specifically, for sorghum grown in rotation with chile pepper, further research is needed to investigate grass weed control when sorghum is grown and sorghum effects on soil fertility for chile pepper production. One potential approach worth exploring is the use of herbicide-resistant grain sorghum, which could improve grass weed control (Abit et al. Reference Abit, Al-Khatib, Olson, Stahlman, Geier, Thompson and Bean2011). However, while herbicide-resistant sorghum offers potential benefits in terms of weed management, it may also raise concerns about herbicide selection pressure and the risk of resistance development in weed populations (Pandian et al. Reference Pandian, Sexton-Bowser, Prasad and Jugulam2022).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/wet.2025.10071

Acknowledgments

We thank Edward Morris, Andrea Nunez, Alexis Olmos, Carlos De Santiago, Lohith Siva Venkata Ramakrishna Koyya, and Kayla Elliott for their contributions to the study.

Funding

This research was funded by the New Mexico Chile Association, the New Mexico State University Agricultural Experiment Station, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture through the Hatch Act (Accession Number: 7006854). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official U.S. Department of Agriculture or U.S. Government determination or policy.

Competing Interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Practical Implications

The findings of this study highlight the trade-offs between weed control efficacy and economic returns when selecting herbicides to control weeds that grow with sorghum in sorghum–chile pepper rotations. Sorghum treated with a premix combination of 2,4-D + bromoxynil + fluroxypyr at the 4-leaf stage and bromoxynil at the 6-leaf stage (the two-application treatment) maximized reductions in both broadleaf weed density and hand hoeing time in the subsequent chile pepper crop. However, sorghum treated with only the premix combination at the 4-leaf stage (the one-application treatment) was more cost-effective, generating a higher net economic benefit (US$6,550 ha−1) than the two-application treatment (US$5,894 ha−1). This suggests that the single application of postemergence herbicides at the V4 stage of sorghum can offer a practical balance between effective weed suppression and economic sustainability for chile pepper production in fields with a soil seedbank enriched with broadleaf weeds. Although the two-application treatment may be preferred under conditions with very heavy broadleaf weed pressure or severe labor shortages, the one-application treatment provides an efficient and profitable option, reinforcing the importance of integrating agronomic performance with cost analysis in herbicide program planning.