1. Introduction

The study of fluid dynamics is fundamental to understanding a wide range of natural and engineered systems, from atmospheric phenomena to industrial processes. Central to this field is the propagation of fluctuations in fluids, which underpins our understanding of acoustics, turbulence and flow stability (Ren, Fu & Pecnik Reference Ren, Fu and Pecnik2019). Traditionally, research on linear waves in fluids has focused on ideal gases, where the assumptions of negligible intermolecular forces and molecular volumes simplify the governing equations (Poling, Prausnitz & O’Connell Reference Poling, Prausnitz and O’Connell2001). However, many real-world fluids deviate from these idealisations, necessitating a more general approach.

Non-ideal fluids, characterised by significant intermolecular interactions and complex equations of state (EOSs), present a rich and challenging area of study (Menikoff & Plohr Reference Menikoff and Plohr1989; Kluwick Reference Kluwick2018; Guardone et al. Reference Guardone, Colonna, Pini and Spinelli2024). These fluids are prevalent in various industrial applications, including heat exchangers (Romei et al. Reference Romei, Vimercati, Persico and Guardone2020), petroleum engineering, chemical processing, aerospace engineering (Cinnella & Congedo Reference Cinnella and Congedo2007) and defence applications. In heat exchanger systems (Nieuwenhuyse, Lecompte & Paepe Reference Van Nieuwenhuyse, Lecompte and De Paepe2023), working fluids sometimes operate under conditions where intermolecular forces significantly impact efficiency and performance. In petroleum engineering (De Hemptinne & Béhar Reference De Hemptinne and Béhar2006), hydrocarbon extraction and processing involve fluids that exhibit non-ideal behaviour due to high pressures and temperatures – e.g. the flash-gas phenomenon – affecting the flow dynamics in pipelines and reservoirs. Similarly, in chemical processing (Brunner Reference Brunner2010), reactor design and operation require a deep understanding of non-ideal fluid behaviour to optimise reaction conditions and ensure safety. In aerospace engineering, high-speed flows and combustion processes under high-pressure conditions necessitate accounting for non-ideal effects to accurately model and predict propulsion performance (Jofre & Urzay Reference Jofre and Urzay2021). Furthermore, in explosion dynamics, overpressure can be sufficiently large for the surrounding solid materials (Powers Reference Powers2004; Saurel et al. Reference Saurel, Métayer, Massoni and Gavrilyuk2007) or the undetonated condensed explosive itself (Lozano, Cawkwell & Aslam Reference Lozano, Cawkwell and Aslam2023) to be effectively modelled in hydrocodes as fluids with highly non-ideal EOSs (Chiapolino & Saurel Reference Chiapolino and Saurel2025). Non-ideal EOSs are also often best expressed explicitly as functions of temperature, which introduces additional challenges to numerical methods (Sirianni et al. Reference Sirianni, Guardone, Re and Abgrall2024; Vienne, Giauque & Lévêque Reference Vienne, Giauque and Lévêque2024; Yan et al. Reference Yan, Gori, Zocca and Guardone2025). Understanding linear wave propagation in non-ideal fluids – i.e. with non-ideal EOSs – is therefore crucial for optimising these processes and predicting fluid behaviour under diverse conditions.

Linear waves in ideal gases have been extensively studied (see e.g. Kirchhoff Reference Kirchhoff1868; Kovásznay Reference Kovásznay1953; Chu & Kovásznay Reference Chu and Kovásznay1958; Chu Reference Chu1965; Fletcher Reference Fletcher1974; Stokes Reference Stokes2009; Benjelloun & Ghidaglia Reference Benjelloun and Ghidaglia2020). Recently, Alferez & Touber (Reference Alferez and Touber2017), Touber & Alferez (Reference Touber and Alferez2019) derived the linear wave dynamics in inviscid, non-conducting and non-ideal fluids. This paper has two main objectives. First, it extends classical linear wave theory to encompass viscous heat-conducting non-ideal compressible fluids, i.e. fluids with an arbitrary EOS. Second, it re-examines the problem of dispersion and attenuation of linear fluctuations in fluids using modern numerical tools, which enable a much more efficient exploration of dispersion relations in fluids. By leveraging the Navier–Stokes–Fourier model, closed with an arbitrary EOS, this study integrates non-ideal effects into the ideal gas framework proposed by Kovásznay (Reference Kovásznay1953), Chu & Kovásznay (Reference Chu and Kovásznay1958) and Chu (Reference Chu1965). It elucidates wave propagation and attenuation in arbitrary non-ideal fluids. This research advances theoretical fluid dynamics while also providing practical insights applicable to a wide range of industrial and research contexts, enabling more accurate modelling and simulation of complex fluid systems.

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the fundamental equations of continuum fluid physics and thermodynamics used in this study. In § 3, these equations are linearised around a stationary and homogeneous base flow. A Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition of velocity simplifies the problem, and plane wave solutions and relevant non-dimensional numbers are introduced and discussed. Based on the linearised equations obtained in § 3, two families of linear waves are identified as solutions of the Navier–Stokes–Fourier model. Their dispersion relations – linking angular frequency to the wave vector of a plane wave – are analysed. The first family, referred to as hydrodynamic (or vorticity) modes, is examined in § 4. The second family, termed thermodynamic (or pressure-entropy) modes, is analysed in § 5. In § 6, a library is used to demonstrate how the general formalism introduced in previous sections can be applied to very different fluids under very different thermodynamic conditions. Finally, conclusions and final remarks are presented in § 7.

2. Thermo-hydrodynamics of non-ideal compressible fluids

Fluids in the continuous regime have diverse properties that can be observed macroscopically. If the influence of body forces and heat injection are neglected, the density

![]() $\rho$

, velocity

$\rho$

, velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}$

and specific total energy

$\boldsymbol{u}$

and specific total energy

![]() $E$

of an arbitrary fluid are governed by the Navier–Stokes–Fourier model (Liepmann & Roshko Reference Liepmann and Roshko2001)

$E$

of an arbitrary fluid are governed by the Navier–Stokes–Fourier model (Liepmann & Roshko Reference Liepmann and Roshko2001)

with

![]() $p$

the pressure,

$p$

the pressure,

![]() $E = e(\rho ,p)+\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{\boldsymbol{\cdot }}\boldsymbol{u}/2$

with

$E = e(\rho ,p)+\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{\boldsymbol{\cdot }}\boldsymbol{u}/2$

with

![]() $e$

the specific internal energy,

$e$

the specific internal energy,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\sigma }$

the viscous part of the stress tensor and

$\boldsymbol{\sigma }$

the viscous part of the stress tensor and

![]() $\boldsymbol{q}$

the heat flux. Each of these fields need to be specified in order to close the system. Starting with the latter, the heat flux is assumed to follow the standard Fourier law for an isotropic fluid

$\boldsymbol{q}$

the heat flux. Each of these fields need to be specified in order to close the system. Starting with the latter, the heat flux is assumed to follow the standard Fourier law for an isotropic fluid

in which

![]() $\lambda$

is the thermal conductivity of the fluid which is defined positive but can depend on other state variables such as

$\lambda$

is the thermal conductivity of the fluid which is defined positive but can depend on other state variables such as

![]() $T$

, the temperature. The most commonly found algebraic closure for the viscous stress tensor

$T$

, the temperature. The most commonly found algebraic closure for the viscous stress tensor

![]() $\boldsymbol{\sigma }$

in an isotropic fluid relates it to the velocity gradient by a linear relation

$\boldsymbol{\sigma }$

in an isotropic fluid relates it to the velocity gradient by a linear relation

in which

![]() $\mu$

and

$\mu$

and

![]() $\mu _b$

are defined positive and correspond to the shear and bulk viscosities modelling the irreversible resistance of the fluid against shear and isotropic compression, respectively. When gas molecules possess internal degrees of freedom, they are characterised by two distinct temperatures: one associated with translational kinetic motion and another linked to internal molecular motion. In cases where internal motion reaches equilibrium rapidly through collisions, the internal temperature becomes negligible, resulting in the emergence of bulk viscosity. Following the popular Stokes hypothesis (Stokes Reference Stokes2009) it is often considered that

$\mu _b$

are defined positive and correspond to the shear and bulk viscosities modelling the irreversible resistance of the fluid against shear and isotropic compression, respectively. When gas molecules possess internal degrees of freedom, they are characterised by two distinct temperatures: one associated with translational kinetic motion and another linked to internal molecular motion. In cases where internal motion reaches equilibrium rapidly through collisions, the internal temperature becomes negligible, resulting in the emergence of bulk viscosity. Following the popular Stokes hypothesis (Stokes Reference Stokes2009) it is often considered that

![]() $\mu _b=0$

. However, this is only a reasonable assumption for monatomic gases in the dilute regime (Sharma, Pareek & Kumar Reference Sharma, Pareek and Kumar2023). Other fluids and other regimes can exhibit a large bulk-to-shear ratio

$\mu _b=0$

. However, this is only a reasonable assumption for monatomic gases in the dilute regime (Sharma, Pareek & Kumar Reference Sharma, Pareek and Kumar2023). Other fluids and other regimes can exhibit a large bulk-to-shear ratio

![]() $\mu _b/\mu$

that can be as large as

$\mu _b/\mu$

that can be as large as

![]() $\mathcal{O}(10^3)$

–

$\mathcal{O}(10^3)$

–

![]() $\mathcal{O}(10^5)$

(Cramer Reference Cramer2012) even in Earth atmospheric conditions (Sharma Reference Sharma2022). This clearly advocates forsaking the Stokes hypothesis in order to be able to consider an arbitrary compressible fluid.

$\mathcal{O}(10^5)$

(Cramer Reference Cramer2012) even in Earth atmospheric conditions (Sharma Reference Sharma2022). This clearly advocates forsaking the Stokes hypothesis in order to be able to consider an arbitrary compressible fluid.

In order to completely close the Navier–Stokes–Fourier model the relationships between the thermodynamic variables

![]() $\rho$

,

$\rho$

,

![]() $p$

,

$p$

,

![]() $e$

and

$e$

and

![]() $T$

need to be prescribed. Additionally, it may be of interest to also know other fields such as the specific entropy

$T$

need to be prescribed. Additionally, it may be of interest to also know other fields such as the specific entropy

![]() $s$

. All these relations are described by an EOS (Lee & Ramamurthi Reference Lee and Ramamurthi2022). The most simple and commonly found model of compressible fluid is the perfect gas. It follows the

$s$

. All these relations are described by an EOS (Lee & Ramamurthi Reference Lee and Ramamurthi2022). The most simple and commonly found model of compressible fluid is the perfect gas. It follows the

![]() $p=\rho R T$

ideal EOS – with

$p=\rho R T$

ideal EOS – with

![]() $R$

the gas-dependent ideal gas constant – and assumes that the isochoric

$R$

the gas-dependent ideal gas constant – and assumes that the isochoric

![]() $C_v = T (\partial s/\partial T )_v$

heat capacity is constant, therefore implying that the isobaric

$C_v = T (\partial s/\partial T )_v$

heat capacity is constant, therefore implying that the isobaric

![]() $C_p = T (\partial s/\partial T )_p$

heat capacity is also constant. However, when the considered fluid behaviour significantly differs from the perfect gas model another EOS is necessary, e.g. the van der Waals model.

$C_p = T (\partial s/\partial T )_p$

heat capacity is also constant. However, when the considered fluid behaviour significantly differs from the perfect gas model another EOS is necessary, e.g. the van der Waals model.

To describe an arbitrary EOS in the context of linear fluctuations, mainly three non-dimensional thermodynamic fields will prove useful in what follows. First, introducing the specific volume

![]() $\vartheta =1/\rho$

, a non-dimensional inverse isochoric heat capacity

$\vartheta =1/\rho$

, a non-dimensional inverse isochoric heat capacity

![]() $g$

can be defined (Menikoff & Plohr Reference Menikoff and Plohr1989)

$g$

can be defined (Menikoff & Plohr Reference Menikoff and Plohr1989)

Second, a large set of thermo-mechanical processes can be modelled as isentropic. Isentropes are described in the

![]() $p$

-

$p$

-

![]() $v$

and

$v$

and

![]() $T$

-

$T$

-

![]() $v$

planes by

$v$

planes by

respectively. These coefficients are the adiabatic coefficient

![]() $\gamma _s$

and the Grüneisen parameter

$\gamma _s$

and the Grüneisen parameter

![]() $\varGamma$

. Indeed, they relate how an infinitesimal pressure variation

$\varGamma$

. Indeed, they relate how an infinitesimal pressure variation

![]() $\textrm{d}p$

(respectively

$\textrm{d}p$

(respectively

![]() $\textrm{d}T$

) is related to an infinitesimal specific volume variation

$\textrm{d}T$

) is related to an infinitesimal specific volume variation

![]() $\textrm{d}v$

along an isentrope. Coefficients

$\textrm{d}v$

along an isentrope. Coefficients

![]() $g$

,

$g$

,

![]() $\gamma _s$

and

$\gamma _s$

and

![]() $\varGamma$

are not completely independent as they should verify a set of inequalities. Indeed, a system in thermodynamic equilibrium exhibits a maximum entropy and must therefore remain stable in face of perturbations. Menikoff & Plohr (Reference Menikoff and Plohr1989) demonstrated that this condition translates to the following inequalities:

$\varGamma$

are not completely independent as they should verify a set of inequalities. Indeed, a system in thermodynamic equilibrium exhibits a maximum entropy and must therefore remain stable in face of perturbations. Menikoff & Plohr (Reference Menikoff and Plohr1989) demonstrated that this condition translates to the following inequalities:

Additionally,

![]() $c$

, the isentropic sound speed of the fluid, is defined as

$c$

, the isentropic sound speed of the fluid, is defined as

![]() $c^2 = \gamma _s p \vartheta$

. It is real as long as the first inequality is verified, along with positive

$c^2 = \gamma _s p \vartheta$

. It is real as long as the first inequality is verified, along with positive

![]() $\vartheta$

and

$\vartheta$

and

![]() $p$

. It is important to note that, in this work,

$p$

. It is important to note that, in this work,

![]() $\gamma _s$

differs from the ratio of specific heats

$\gamma _s$

differs from the ratio of specific heats

which is commonly defined in the context of non-ideal compressible fluids (Guardone et al. Reference Guardone, Colonna, Pini and Spinelli2024). Instead, these coefficients are related by

![]() $\gamma _s = (\rho /p) (\partial p/\partial \rho )_T \gamma$

. This relation shows that the adiabatic coefficient

$\gamma _s = (\rho /p) (\partial p/\partial \rho )_T \gamma$

. This relation shows that the adiabatic coefficient

![]() $\gamma _s$

coincides with the heat capacity ratio only when

$\gamma _s$

coincides with the heat capacity ratio only when

![]() $(\rho /p) (\partial p/\partial \rho )_T = 1$

, which holds true for ideal gases, where the EOS takes the form

$(\rho /p) (\partial p/\partial \rho )_T = 1$

, which holds true for ideal gases, where the EOS takes the form

![]() $p \propto \rho T$

.

$p \propto \rho T$

.

A very important non-dimensional number characterising non-ideal fluids is the so-called fundamental derivative of gas dynamics (Thompson Reference Thompson1971; Kluwick Reference Kluwick2018)

This thermodynamic quantity is usually positive, which is sometimes referred to as positive nonlinearity (Cramer & Kluwick Reference Cramer and Kluwick1984). This corresponds to the classical behaviour of gas dynamics. However, a negative nonlinearity

![]() $\mathcal{G}\lt 0$

is associated with possibly non-classical behaviours. These include composite and split waves (Cramer & Sen Reference Cramer and Sen1986; Cramer Reference Cramer1989; Guardone et al. Reference Guardone, Colonna, Casati and Rinaldi2014), compression fans (Cramer & Park Reference Cramer and Park1999) and the occurrence of admissible expansion shock waves (Thompson & Lambrakis Reference Thompson and Lambrakis1973; Borisov et al. Reference Borisov, Borisov, Kutateladze and Nakoryakov1983; Zamfirescu, Guardone & Colonna Reference Zamfirescu, Guardone and Colonna2008; Guardone, Zamfirescu & Colonna Reference Guardone, Zamfirescu and Colonna2010; Guardone & Vimercati Reference Guardone and Vimercati2016; Nannan et al. Reference Nannan, Sirianni, Mathijssen, Guardone and Colonna2016; Kluwick & Cox Reference Kluwick and Cox2019). Since

$\mathcal{G}\lt 0$

is associated with possibly non-classical behaviours. These include composite and split waves (Cramer & Sen Reference Cramer and Sen1986; Cramer Reference Cramer1989; Guardone et al. Reference Guardone, Colonna, Casati and Rinaldi2014), compression fans (Cramer & Park Reference Cramer and Park1999) and the occurrence of admissible expansion shock waves (Thompson & Lambrakis Reference Thompson and Lambrakis1973; Borisov et al. Reference Borisov, Borisov, Kutateladze and Nakoryakov1983; Zamfirescu, Guardone & Colonna Reference Zamfirescu, Guardone and Colonna2008; Guardone, Zamfirescu & Colonna Reference Guardone, Zamfirescu and Colonna2010; Guardone & Vimercati Reference Guardone and Vimercati2016; Nannan et al. Reference Nannan, Sirianni, Mathijssen, Guardone and Colonna2016; Kluwick & Cox Reference Kluwick and Cox2019). Since

![]() $p' = c^2 \rho ' + 0.5 (\partial c^2/\partial \rho )_s \rho '^2 + \boldsymbol{\cdots}$

with

$p' = c^2 \rho ' + 0.5 (\partial c^2/\partial \rho )_s \rho '^2 + \boldsymbol{\cdots}$

with

![]() $(\partial c^2/\partial \rho )_s = 2 c^2 (\mathcal{G}-1)/\rho$

and the present study focuses on the linear limit of the Navier–Stokes–Fourier model, the fundamental derivative of gas dynamics does not appear explicitly in this work, as it is associated with nonlinear higher-order terms. However, this is not true for all perturbation theories, since Cramer & Kluwick (Reference Cramer and Kluwick1984) demonstrated that weak shock theory indeed depends on

$(\partial c^2/\partial \rho )_s = 2 c^2 (\mathcal{G}-1)/\rho$

and the present study focuses on the linear limit of the Navier–Stokes–Fourier model, the fundamental derivative of gas dynamics does not appear explicitly in this work, as it is associated with nonlinear higher-order terms. However, this is not true for all perturbation theories, since Cramer & Kluwick (Reference Cramer and Kluwick1984) demonstrated that weak shock theory indeed depends on

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

.

$\mathcal{G}$

.

The second principle and various relations between thermodynamic state variables that essentially describe the material response of the considered fluid (Lee & Ramamurthi Reference Lee and Ramamurthi2022) can be expressed from

![]() $g$

,

$g$

,

![]() $\gamma _s$

and

$\gamma _s$

and

![]() $\varGamma$

. In this study four of these relations will be used

$\varGamma$

. In this study four of these relations will be used

Throughout the present work, the considered EOS is left to the reader’s choice, with two requirements. The first one is that the selected EOS is compatible with the laws of thermodynamics: it follows the inequalities (2.6a

)–(2.6c

),

![]() $p\gt 0$

,

$p\gt 0$

,

![]() $\vartheta \gt 0$

,

$\vartheta \gt 0$

,

![]() $T\gt 0$

and all the state relations such as (2.9a

)–(2.9d

) should be verified. The second requirement is that the variables

$T\gt 0$

and all the state relations such as (2.9a

)–(2.9d

) should be verified. The second requirement is that the variables

![]() $\rho$

,

$\rho$

,

![]() $p$

,

$p$

,

![]() $T$

,

$T$

,

![]() $e$

,

$e$

,

![]() $s$

,

$s$

,

![]() $g$

,

$g$

,

![]() $\gamma _s$

,

$\gamma _s$

,

![]() $\varGamma$

and

$\varGamma$

and

![]() $C_v$

are supposed to be known and computable for the chosen EOS.

$C_v$

are supposed to be known and computable for the chosen EOS.

By using the state relations ((2.9a ), (2.9c )) it is possible to deduce from ((2.1a )–(2.1c )) the governing equations of velocity, entropy and pressure for an arbitrary EOS

To summarise this section, assuming that the selected EOS follows the laws of thermodynamics, the Navier–Stokes–Fourier system in its mass–momentum–energy conservation usual form ((2.1a

)–(2.1c

)) is re-expressed in its

![]() $\boldsymbol{u},s,p$

form (2.10a

)–(2.10c

). This form of the Navier–Stokes–Fourier model will be used in this work. It is closed by ((2.2), (2.3)) and an arbitrary EOS that follows the laws of thermodynamics (2.9a

)–(2.9d

)).

$\boldsymbol{u},s,p$

form (2.10a

)–(2.10c

). This form of the Navier–Stokes–Fourier model will be used in this work. It is closed by ((2.2), (2.3)) and an arbitrary EOS that follows the laws of thermodynamics (2.9a

)–(2.9d

)).

3. First-order perturbation theory

The fluid flow is assumed to consist of a known stationary and homogeneous base flow with unknown superimposed fluctuations. The purpose of this section is to derive the governing equations of these fluctuations. An observable

![]() $\phi$

(pressure, velocity, viscosity, etc.) is expressed as

$\phi$

(pressure, velocity, viscosity, etc.) is expressed as

where

![]() $\phi '$

is the fluctuation with respect to the stationary and homogeneous base state

$\phi '$

is the fluctuation with respect to the stationary and homogeneous base state

![]() $\overline {\phi }$

. Because this work focuses on a first-order perturbation theory, the crossed fluctuation terms, e.g.

$\overline {\phi }$

. Because this work focuses on a first-order perturbation theory, the crossed fluctuation terms, e.g.

![]() $\phi ' \phi '$

and

$\phi ' \phi '$

and

![]() $\phi ' \phi ' \phi '$

, will be systematically assumed negligible. Additionally,

$\phi ' \phi ' \phi '$

, will be systematically assumed negligible. Additionally,

![]() $(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

dependencies are omitted throughout the complete article for compactness. It should therefore be remembered that the base flow is known, homogeneous and stationary while the fluctuations depends on

$(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

dependencies are omitted throughout the complete article for compactness. It should therefore be remembered that the base flow is known, homogeneous and stationary while the fluctuations depends on

![]() $(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

. Upon injection of (3.1) for

$(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

. Upon injection of (3.1) for

![]() $\phi = p$

,

$\phi = p$

,

![]() $\rho$

,

$\rho$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}$

, etc. inside ((2.10a

)–(2.10c

)) and by neglecting crossed fluctuation terms one can find

$\boldsymbol{u}$

, etc. inside ((2.10a

)–(2.10c

)) and by neglecting crossed fluctuation terms one can find

in which the material derivative describes the advection by the base state velocity

![]() $\overline {\boldsymbol{u}}$

. An auxiliary relation that can be deduced either from ((2.9c

), (3.2b

), (3.2c

)) or directly from (2.1a

)

$\overline {\boldsymbol{u}}$

. An auxiliary relation that can be deduced either from ((2.9c

), (3.2b

), (3.2c

)) or directly from (2.1a

)

will also prove useful in what follows.

3.1. Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition of velocity fluctuations

Then, by taking advantage of the principle of superposition of linear solutions the velocity vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}$

is sought by using an Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition

$\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}$

is sought by using an Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_{\delta }^{\prime}$

and

$\boldsymbol{u}_{\delta }^{\prime}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}_\omega$

respectively correspond to the curl free (irrotational) and divergence free (incompressible) components of the velocity field i.e.

$\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}_\omega$

respectively correspond to the curl free (irrotational) and divergence free (incompressible) components of the velocity field i.e.

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}_h$

is a potential flow defined as a function of

$\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}_h$

is a potential flow defined as a function of

![]() $\psi$

an harmonic field,

$\psi$

an harmonic field,

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}_h = \boldsymbol{\nabla }\psi$

. This leads to relations between the vorticity

$\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}_h = \boldsymbol{\nabla }\psi$

. This leads to relations between the vorticity

![]() $\boldsymbol{\omega }^{\prime}$

and

$\boldsymbol{\omega }^{\prime}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_\omega ^{\prime}$

on one side, and the velocity divergence

$\boldsymbol{u}_\omega ^{\prime}$

on one side, and the velocity divergence

![]() $\delta '$

and

$\delta '$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_{\delta }^{\prime}$

on the other side

$\boldsymbol{u}_{\delta }^{\prime}$

on the other side

This also means that incompressible

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_\omega ^{\prime}$

and irrotational

$\boldsymbol{u}_\omega ^{\prime}$

and irrotational

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_{\delta }^{\prime}$

velocity components are not uniquely defined by the knowledge of the divergence and vorticity fields because one could always add an arbitrary harmonic field to either

$\boldsymbol{u}_{\delta }^{\prime}$

velocity components are not uniquely defined by the knowledge of the divergence and vorticity fields because one could always add an arbitrary harmonic field to either

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_\omega ^{\prime}$

or

$\boldsymbol{u}_\omega ^{\prime}$

or

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_{\delta }^{\prime}$

and then subtract it to

$\boldsymbol{u}_{\delta }^{\prime}$

and then subtract it to

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_h'$

. It is a well-known problem of the Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition and is related to the fact that harmonic flows are associated with boundary conditions (Bhatia et al. Reference Bhatia, Norgard, Pascucci and Bremer2012). In an unbounded domain the harmonic field

$\boldsymbol{u}_h'$

. It is a well-known problem of the Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition and is related to the fact that harmonic flows are associated with boundary conditions (Bhatia et al. Reference Bhatia, Norgard, Pascucci and Bremer2012). In an unbounded domain the harmonic field

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_h'$

is arbitrary because boundary conditions are absent, the harmonic field is therefore arbitrarily chosen as

$\boldsymbol{u}_h'$

is arbitrary because boundary conditions are absent, the harmonic field is therefore arbitrarily chosen as

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_h'=\boldsymbol{0}$

. Thanks to this simplification, the velocity fluctuation is uniquely defined from its vorticity and divergence. Applying curl and divergence operators to (3.2a

) leads to

$\boldsymbol{u}_h'=\boldsymbol{0}$

. Thanks to this simplification, the velocity fluctuation is uniquely defined from its vorticity and divergence. Applying curl and divergence operators to (3.2a

) leads to

respectively. They represent the governing equations of the vorticity and divergence fluctuations and can be used instead of (3.2a ).

3.2. Linearised Navier–Stokes–Fourier system

Then, the linearised heat flux and viscous stress tensor read

Injecting these last two equations inside ((3.2b

), (3.2c

), (3.7a

), (3.7b

)) and eliminating the temperature fluctuation by using (2.9d

) leads to the linearised Navier–Stokes–Fourier system expressed in

![]() $\boldsymbol{\omega }^{\prime}$

,

$\boldsymbol{\omega }^{\prime}$

,

![]() $\delta '$

,

$\delta '$

,

![]() $s'$

and

$s'$

and

![]() $p'$

variables

$p'$

variables

\begin{align}&\qquad \overline {\rho } \overline {T}\frac {\textrm{d} s'}{\textrm{d} t} = \frac {\overline {\lambda }\,\overline {\varGamma }\,\overline {T}}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {p}}\Delta p' + \left (1-\frac {\overline {\varGamma }^2}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {g}}\right )\frac {\overline {\lambda }\,\overline {T}}{\overline {C_v}}\Delta s', \end{align}

\begin{align}&\qquad \overline {\rho } \overline {T}\frac {\textrm{d} s'}{\textrm{d} t} = \frac {\overline {\lambda }\,\overline {\varGamma }\,\overline {T}}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {p}}\Delta p' + \left (1-\frac {\overline {\varGamma }^2}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {g}}\right )\frac {\overline {\lambda }\,\overline {T}}{\overline {C_v}}\Delta s', \end{align}

\begin{align}& \frac {\textrm{d} p'}{\textrm{d}t} = -\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {p} \,\delta ' +\frac {\overline {\lambda }\,\overline {\varGamma }^2\,\overline {T}}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {p}}\Delta p' + \left (1-\frac {\overline {\varGamma }^2}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {g}}\right )\frac {\overline {\lambda }\,\overline {\varGamma }\,\overline {T}}{\overline {C_v}}\Delta s'. \end{align}

\begin{align}& \frac {\textrm{d} p'}{\textrm{d}t} = -\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {p} \,\delta ' +\frac {\overline {\lambda }\,\overline {\varGamma }^2\,\overline {T}}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {p}}\Delta p' + \left (1-\frac {\overline {\varGamma }^2}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {g}}\right )\frac {\overline {\lambda }\,\overline {\varGamma }\,\overline {T}}{\overline {C_v}}\Delta s'. \end{align}

Clearly the divergence, pressure and entropy fluctuations are intrinsically coupled. However, the vorticity field obeys its own governing equation and therefore appears as an autonomous variable uncoupled from the other fields. This does not come as a surprise as it was already the case for perfect gases. Indeed, since the pioneering work of Kovásznay (Reference Kovásznay1953), Chu & Kovásznay (Reference Chu and Kovásznay1958) and Chu (Reference Chu1965), the vorticity, entropy and pressure fields have been identified as the modes of the linearised Euler system for perfect gases.

3.3. Plane wave solutions

Thanks to the superposition principle of linear solutions, a small fluctuation can always be written as a Fourier series. Therefore, the modes that are solutions of ((3.9a

)–(3.9d

)) are sought in the form of plane waves. Hence, a dummy fluctuating field

![]() $\phi '$

is written as

$\phi '$

is written as

It is characterised by an amplitude

![]() $\tilde {\phi }(\boldsymbol{k}) \in \mathbb{C}$

, a wave vector

$\tilde {\phi }(\boldsymbol{k}) \in \mathbb{C}$

, a wave vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{k} \in \mathbb{R}^3$

and an angular frequency

$\boldsymbol{k} \in \mathbb{R}^3$

and an angular frequency

![]() $\varOmega _\phi (\boldsymbol{k}) \in \mathbb{C}$

which is a function of

$\varOmega _\phi (\boldsymbol{k}) \in \mathbb{C}$

which is a function of

![]() $\boldsymbol{k}$

to be determined. By neglecting

$\boldsymbol{k}$

to be determined. By neglecting

![]() $\operatorname {Im}(\varOmega _\phi )$

, the real part

$\operatorname {Im}(\varOmega _\phi )$

, the real part

![]() $\operatorname {\textrm{Re}}(\varOmega _\phi )$

is found to characterise the wave speed propagation because then

$\operatorname {\textrm{Re}}(\varOmega _\phi )$

is found to characterise the wave speed propagation because then

![]() $\phi '$

is constant along trajectories of constant

$\phi '$

is constant along trajectories of constant

![]() $\boldsymbol{k}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{x}-\operatorname {\textrm{Re}}(\varOmega _\phi ) t$

. By neglecting

$\boldsymbol{k}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{x}-\operatorname {\textrm{Re}}(\varOmega _\phi ) t$

. By neglecting

![]() $\operatorname {\textrm{Re}}(\varOmega _\phi )$

, a negative (respectively positive) imaginary part

$\operatorname {\textrm{Re}}(\varOmega _\phi )$

, a negative (respectively positive) imaginary part

![]() $\operatorname {Im}(\varOmega _\phi )$

induces time attenuation (respectively amplification). Amplification being forbidden in order to allow linearly stable thermo-mechanical equilibrium to exist, the imaginary part is expected to always satisfy

$\operatorname {Im}(\varOmega _\phi )$

induces time attenuation (respectively amplification). Amplification being forbidden in order to allow linearly stable thermo-mechanical equilibrium to exist, the imaginary part is expected to always satisfy

![]() $\operatorname {Im}(\varOmega _\phi )\leqslant 0$

.

$\operatorname {Im}(\varOmega _\phi )\leqslant 0$

.

In what follows, fluctuations in the form of plane waves will be injected into ((3.9a

)–(3.9d

)), thus leading to modes similar to (3.10). The dispersion relation

![]() $\varOmega _\phi (\boldsymbol{k})$

will be computed and expressed from non-dimensional numbers for each individual mode, therefore elucidating the propagation and attenuation of each mode of the Navier–Stokes–Fourier model with an arbitrary EOS.

$\varOmega _\phi (\boldsymbol{k})$

will be computed and expressed from non-dimensional numbers for each individual mode, therefore elucidating the propagation and attenuation of each mode of the Navier–Stokes–Fourier model with an arbitrary EOS.

3.4. Useful non-dimensional numbers

The first and most important non-dimensional number that will be considered hereafter is

![]() $\varPi$

. It can be related to the Mach number

$\varPi$

. It can be related to the Mach number

![]() $Ma$

and Reynolds number

$Ma$

and Reynolds number

![]() $\boldsymbol{Re}$

$\boldsymbol{Re}$

Indeed, the relation

![]() $\varPi \propto \textit{Ma} / \textit{Re}$

suggests a parallel with the Knudsen number

$\varPi \propto \textit{Ma} / \textit{Re}$

suggests a parallel with the Knudsen number

![]() $Kn$

, as it is also proportional to

$Kn$

, as it is also proportional to

![]() $\textit{Ma}/\textit{Re}$

in ideal gases (Cercignani Reference Cercignani2000). The Knudsen number is classically defined as the ratio of the characteristic molecular mean free path to the characteristic macroscopic length of a given problem (e.g. the chord of an airfoil or the radius of a pipe). It is generally accepted that, when

$\textit{Ma}/\textit{Re}$

in ideal gases (Cercignani Reference Cercignani2000). The Knudsen number is classically defined as the ratio of the characteristic molecular mean free path to the characteristic macroscopic length of a given problem (e.g. the chord of an airfoil or the radius of a pipe). It is generally accepted that, when

![]() $Kn$

reaches sufficiently large values, the continuum assumption (and the Navier–Stokes–Fourier model) loses accuracy and should be replaced by a rarefied gas model (Cercignani Reference Cercignani2000). However, the selection of a characteristic length scale is somewhat ambiguous and does not fully address the properties of local flow physics, where a local characteristic length scale may emerge (e.g. shock or boundary layer thickness).

$Kn$

reaches sufficiently large values, the continuum assumption (and the Navier–Stokes–Fourier model) loses accuracy and should be replaced by a rarefied gas model (Cercignani Reference Cercignani2000). However, the selection of a characteristic length scale is somewhat ambiguous and does not fully address the properties of local flow physics, where a local characteristic length scale may emerge (e.g. shock or boundary layer thickness).

Additionally, in this context,

![]() $\boldsymbol{Re}$

and

$\boldsymbol{Re}$

and

![]() $\varPi$

are based on the characteristic length scale

$\varPi$

are based on the characteristic length scale

![]() $2/\lVert \boldsymbol{k}\rVert$

, which is not always clearly linked to an experimental set-up or a macroscopic length scale. Instead,

$2/\lVert \boldsymbol{k}\rVert$

, which is not always clearly linked to an experimental set-up or a macroscopic length scale. Instead,

![]() $2/\lVert \boldsymbol{k}\rVert$

is associated with the wavelength of a fluctuation in a region of the fluid where the characteristic dynamic viscosity, density and isentropic sound speed are

$2/\lVert \boldsymbol{k}\rVert$

is associated with the wavelength of a fluctuation in a region of the fluid where the characteristic dynamic viscosity, density and isentropic sound speed are

![]() $\overline {\mu }$

,

$\overline {\mu }$

,

![]() $\overline {\rho }$

and

$\overline {\rho }$

and

![]() $\overline {c}$

, respectively. Finally, it is also important to emphasise that the relation

$\overline {c}$

, respectively. Finally, it is also important to emphasise that the relation

![]() $Kn \propto Ma/Re$

is derived under specific assumptions (hard sphere gases without attraction or repulsion), which may not necessarily hold for non-ideal fluids.

$Kn \propto Ma/Re$

is derived under specific assumptions (hard sphere gases without attraction or repulsion), which may not necessarily hold for non-ideal fluids.

Therefore, in the following,

![]() $\varPi = Ma/Re$

is deliberately not interpreted as a Knudsen number. Instead, fluctuations with short wavelengths (or, equivalently, large wave vectors) tend to have larger

$\varPi = Ma/Re$

is deliberately not interpreted as a Knudsen number. Instead, fluctuations with short wavelengths (or, equivalently, large wave vectors) tend to have larger

![]() $\varPi$

values than those with long wavelengths (or small wave vectors). In this context, both small and large values of

$\varPi$

values than those with long wavelengths (or small wave vectors). In this context, both small and large values of

![]() $\varPi$

will be examined.

$\varPi$

will be examined.

The ratio of viscous effects to heat conduction effects is typically measured by the Prandtl number,

![]() $Pr$

. In the following, heat conduction will be expressed through the non-dimensional number

$Pr$

. In the following, heat conduction will be expressed through the non-dimensional number

![]() $\varLambda$

, which is related to the Prandtl number by

$\varLambda$

, which is related to the Prandtl number by

The last two non-dimensional numbers that will be used are related to the bulk-to-shear viscosity ratio and the compliance with the thermodynamic stability. They are defined by

\begin{equation} {{B}} = \frac {\overline {\mu _b}+\dfrac {4}{3}\overline {\mu }}{\overline {\mu }}=\frac {4}{3}+\frac {\overline {\mu _b}}{\overline {\mu }},\qquad \qquad \varTheta =\frac {\overline {\varGamma }^2}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {g}}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} {{B}} = \frac {\overline {\mu _b}+\dfrac {4}{3}\overline {\mu }}{\overline {\mu }}=\frac {4}{3}+\frac {\overline {\mu _b}}{\overline {\mu }},\qquad \qquad \varTheta =\frac {\overline {\varGamma }^2}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {g}}. \end{equation}

When

![]() ${{B}}=4/3$

the hypothesis introduced by Stokes (Reference Stokes2009) holds true. Otherwise,

${{B}}=4/3$

the hypothesis introduced by Stokes (Reference Stokes2009) holds true. Otherwise,

![]() ${{B}}\gt 4/3$

because the second principle requires a positive bulk viscosity (Landau & Lifshitz Reference Landau and Lifshitz1987). The parameter

${{B}}\gt 4/3$

because the second principle requires a positive bulk viscosity (Landau & Lifshitz Reference Landau and Lifshitz1987). The parameter

![]() $\varTheta$

being a measure of the compliance of the thermodynamic stability criterion (2.6c

) it is necessary that

$\varTheta$

being a measure of the compliance of the thermodynamic stability criterion (2.6c

) it is necessary that

![]() $0\leqslant \varTheta \leqslant 1$

. Another interpretation of

$0\leqslant \varTheta \leqslant 1$

. Another interpretation of

![]() $\varTheta$

is to notice that it is a measure of the difference between the isentropic and isothermal sound speed

$\varTheta$

is to notice that it is a measure of the difference between the isentropic and isothermal sound speed

\begin{equation} \varTheta = \frac {\left (\dfrac {\partial \overline {p}}{\partial \overline {\rho }}\right )_{\overline {s}}-\left (\dfrac {\partial \overline {p}}{\partial \overline {\rho }}\right )_{\overline {T}}}{\left (\dfrac {\partial \overline {p}}{\partial \overline {\rho }}\right )_{\overline {s}}} = \frac {\overline {c}^2-\overline {c}_T^2}{\overline {c}^2}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \varTheta = \frac {\left (\dfrac {\partial \overline {p}}{\partial \overline {\rho }}\right )_{\overline {s}}-\left (\dfrac {\partial \overline {p}}{\partial \overline {\rho }}\right )_{\overline {T}}}{\left (\dfrac {\partial \overline {p}}{\partial \overline {\rho }}\right )_{\overline {s}}} = \frac {\overline {c}^2-\overline {c}_T^2}{\overline {c}^2}. \end{equation}

A final and more insightful interpretation, consistent with previous works on non-ideal compressible fluids (Guardone et al. Reference Guardone, Colonna, Pini and Spinelli2024), is to observe that the non-dimensional parameter

![]() $\varTheta$

can also be expressed as

$\varTheta$

can also be expressed as

Therefore, while values of

![]() $\varTheta \approx 0$

correspond to the low heat capacity ratios typically observed in the liquid phase, values of

$\varTheta \approx 0$

correspond to the low heat capacity ratios typically observed in the liquid phase, values of

![]() $\varTheta \approx 1$

are generally associated with the vicinity of the critical point. Using ((2.9c

), (2.9d

)) in order to further highlight the influence of

$\varTheta \approx 1$

are generally associated with the vicinity of the critical point. Using ((2.9c

), (2.9d

)) in order to further highlight the influence of

![]() $\varTheta$

the following thermodynamic identities can be expressed:

$\varTheta$

the following thermodynamic identities can be expressed:

and show that, even though

![]() $s'\neq 0$

, the

$s'\neq 0$

, the

![]() $T'$

-

$T'$

-

![]() $p'$

and

$p'$

and

![]() $\rho '$

-

$\rho '$

-

![]() $p'$

relations tend to behave isentropically as

$p'$

relations tend to behave isentropically as

![]() $\varTheta$

tends to

$\varTheta$

tends to

![]() $1$

and

$1$

and

![]() $0$

, respectively. While a different set of non-dimensional numbers could have been selected it will be shown in the following sections that the present choice allows a compact yet clear presentation of the various regimes of modes in a fluid flow of non-ideal fluids. Inspired by previous works of Kovásznay (Reference Kovásznay1953), Chu & Kovásznay (Reference Chu and Kovásznay1958) and Chu (Reference Chu1965), the modes in a non-ideal compressible fluid are now analysed.

$0$

, respectively. While a different set of non-dimensional numbers could have been selected it will be shown in the following sections that the present choice allows a compact yet clear presentation of the various regimes of modes in a fluid flow of non-ideal fluids. Inspired by previous works of Kovásznay (Reference Kovásznay1953), Chu & Kovásznay (Reference Chu and Kovásznay1958) and Chu (Reference Chu1965), the modes in a non-ideal compressible fluid are now analysed.

4. Hydrodynamic modes

The equation (3.9a

) appears to be uncoupled from the rest of the system ((3.9b

)–(3.9d

)), indicating that the vorticity components

![]() $\omega _x^{\prime}$

,

$\omega _x^{\prime}$

,

![]() $\omega _y^{\prime}$

and

$\omega _y^{\prime}$

and

![]() $\omega _z^{\prime}$

represent independent modes of the system. They are sought in the form of plane waves

$\omega _z^{\prime}$

represent independent modes of the system. They are sought in the form of plane waves

characterised by the amplitude

![]() $\tilde {\boldsymbol{\omega }} \in \mathbb{C}^3$

, the wave vector

$\tilde {\boldsymbol{\omega }} \in \mathbb{C}^3$

, the wave vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{k} \in \mathbb{R}^3$

and the angular frequency

$\boldsymbol{k} \in \mathbb{R}^3$

and the angular frequency

![]() $\varOmega _\omega (\boldsymbol{k}) \in \mathbb{C}$

, which is a function of

$\varOmega _\omega (\boldsymbol{k}) \in \mathbb{C}$

, which is a function of

![]() $\boldsymbol{k}$

to be determined. It is important to note that the

$\boldsymbol{k}$

to be determined. It is important to note that the

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

vorticity modes are assumed to share a common wave vector and, consequently, a common angular frequency. While this assumption is not strictly necessary, it simplifies the presentation without affecting the qualitative conclusions.

$z$

vorticity modes are assumed to share a common wave vector and, consequently, a common angular frequency. While this assumption is not strictly necessary, it simplifies the presentation without affecting the qualitative conclusions.

Substituting (4.1) into (3.9a) and simplifying yields the dispersion relation for vorticity modes

Substituting (4.2) into (4.1) provides the vorticity modes in a viscous and heat-conducting non-ideal fluid

For

![]() $\varPi \ll 1$

, the effect of viscosity approaches zero, and the vorticity equation (3.9a

) reduces to passive scalar advection. In this regime,

$\varPi \ll 1$

, the effect of viscosity approaches zero, and the vorticity equation (3.9a

) reduces to passive scalar advection. In this regime,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\omega }^{\prime}$

remains constant along trajectories where

$\boldsymbol{\omega }^{\prime}$

remains constant along trajectories where

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}-\overline {\boldsymbol{u}} t$

is conserved. This implies that, in an inviscid flow, vorticity fluctuations are passively advected by the mean flow velocity

$\boldsymbol{x}-\overline {\boldsymbol{u}} t$

is conserved. This implies that, in an inviscid flow, vorticity fluctuations are passively advected by the mean flow velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}$

. The same holds true in a viscous flow as long as

$\boldsymbol{u}$

. The same holds true in a viscous flow as long as

![]() $t\ll 1/ (2\varPi \lVert \boldsymbol{k}\rVert \overline {c} )$

. Conversely, when

$t\ll 1/ (2\varPi \lVert \boldsymbol{k}\rVert \overline {c} )$

. Conversely, when

![]() $t$

approaches or exceeds

$t$

approaches or exceeds

![]() $1/ (2\varPi \lVert \boldsymbol{k}\rVert \overline {c} )$

, viscous effects become significant, leading to attenuation due to the negative imaginary component of

$1/ (2\varPi \lVert \boldsymbol{k}\rVert \overline {c} )$

, viscous effects become significant, leading to attenuation due to the negative imaginary component of

![]() $\varOmega _\omega$

.

$\varOmega _\omega$

.

Having characterised the vorticity mode, we now explore how an arbitrary vorticity fluctuation correlates with other thermo-hydrodynamic fluctuations. As previously mentioned, vorticity fluctuations correlate only with the incompressible velocity field

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_\omega ^{\prime}$

through (3.6a

). Each vorticity component evolves autonomously, allowing the total vorticity field to be expressed as a linear superposition of three independent vorticity modes

$\boldsymbol{u}_\omega ^{\prime}$

through (3.6a

). Each vorticity component evolves autonomously, allowing the total vorticity field to be expressed as a linear superposition of three independent vorticity modes

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{\omega }^{\prime} = \begin{pmatrix} \omega _x^{\prime}\\ 0\\ 0 \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix} 0\\ \omega _y^{\prime}\\ 0 \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix} 0\\ 0\\ \omega _z^{\prime} \end{pmatrix}\! . \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{\omega }^{\prime} = \begin{pmatrix} \omega _x^{\prime}\\ 0\\ 0 \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix} 0\\ \omega _y^{\prime}\\ 0 \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix} 0\\ 0\\ \omega _z^{\prime} \end{pmatrix}\! . \end{equation}

Using ((3.6a ), (4.1)), the algebraic relations between the incompressible velocity fields associated with each vorticity mode are derived

where

![]() $k_x$

,

$k_x$

,

![]() $k_y$

and

$k_y$

and

![]() $k_z$

are the components of the wave vector

$k_z$

are the components of the wave vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{k}$

, and, for example,

$\boldsymbol{k}$

, and, for example,

![]() $u_{\omega _x,y}^{\prime}$

and

$u_{\omega _x,y}^{\prime}$

and

![]() $u_{\omega _x,z}^{\prime}$

are the

$u_{\omega _x,z}^{\prime}$

are the

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

incompressible velocity components stemming from the

$z$

incompressible velocity components stemming from the

![]() $x$

-vorticity mode

$x$

-vorticity mode

![]() $\omega _x^{\prime}$

. Recalling that incompressible velocity fields are divergence free provides additional constraints for each vorticity component

$\omega _x^{\prime}$

. Recalling that incompressible velocity fields are divergence free provides additional constraints for each vorticity component

These relations, together with ((4.5a )–(4.5c )), allow us to determine the total incompressible velocity fluctuations associated with each vorticity mode

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{u}_{\omega }^{\prime} = \begin{pmatrix} 0\\ \displaystyle \frac {i k_z}{k_y^2+k_z^2} \\ \displaystyle - \frac {i k_y}{k_y^2+k_z^2} \end{pmatrix}\omega _x^{\prime} + \begin{pmatrix} \displaystyle - \frac {i k_z}{k_z^2+k_x^2}\\ 0\\ \displaystyle \frac {i k_x}{k_z^2+k_x^2} \end{pmatrix}\omega _y^{\prime} + \begin{pmatrix} \displaystyle \frac {i k_y}{k_x^2+k_y^2}\\ \displaystyle - \frac {i k_x}{k_x^2+k_y^2}\\ 0 \end{pmatrix}\omega _z^{\prime}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{u}_{\omega }^{\prime} = \begin{pmatrix} 0\\ \displaystyle \frac {i k_z}{k_y^2+k_z^2} \\ \displaystyle - \frac {i k_y}{k_y^2+k_z^2} \end{pmatrix}\omega _x^{\prime} + \begin{pmatrix} \displaystyle - \frac {i k_z}{k_z^2+k_x^2}\\ 0\\ \displaystyle \frac {i k_x}{k_z^2+k_x^2} \end{pmatrix}\omega _y^{\prime} + \begin{pmatrix} \displaystyle \frac {i k_y}{k_x^2+k_y^2}\\ \displaystyle - \frac {i k_x}{k_x^2+k_y^2}\\ 0 \end{pmatrix}\omega _z^{\prime}. \end{equation}

Applying the material derivative to

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_{\omega }^{\prime}$

and using ((3.9a

), (4.7)) yields the governing equation for the incompressible velocity field

$\boldsymbol{u}_{\omega }^{\prime}$

and using ((3.9a

), (4.7)) yields the governing equation for the incompressible velocity field

Vorticity fluctuations therefore remain independent of the EOS and are consistent with those described in the perfect gas literature (Kovásznay Reference Kovásznay1953; Chu & Kovásznay Reference Chu and Kovásznay1958; Chu Reference Chu1965).

5. Thermodynamic modes

In the previous section, the modes characterised by vorticity fluctuations were derived and discussed. This section focuses on the remaining three modes that are solutions of ((3.9b

)–(3.9d

)). In the case of a non-conducting and inviscid ideal gas, Kovásznay (Reference Kovásznay1953) analysed these modes and found that they correspond to an entropy mode, characterised by

![]() $s'\neq 0$

,

$s'\neq 0$

,

![]() $p'=0$

,

$p'=0$

,

![]() $\delta '=0$

, and two acoustic modes, characterised by

$\delta '=0$

, and two acoustic modes, characterised by

![]() $s'=0$

,

$s'=0$

,

![]() $p'\neq 0$

,

$p'\neq 0$

,

![]() $\delta '\neq 0$

. In a viscous and conducting ideal gas, Chu & Kovásznay (Reference Chu and Kovásznay1958) and Chu (Reference Chu1965) found that the pure entropy mode and pure acoustic mode are replaced by three modes exhibiting non-zero fluctuations in

$\delta '\neq 0$

. In a viscous and conducting ideal gas, Chu & Kovásznay (Reference Chu and Kovásznay1958) and Chu (Reference Chu1965) found that the pure entropy mode and pure acoustic mode are replaced by three modes exhibiting non-zero fluctuations in

![]() $p'$

,

$p'$

,

![]() $s'$

and

$s'$

and

![]() $\delta '$

.

$\delta '$

.

For an arbitrary EOS, similar results are expected. From ((3.9b

)–(3.9d

)), trial and error suggests that it is not possible to derive a closed-form governing equation for

![]() $p'$

,

$p'$

,

![]() $\delta '$

or

$\delta '$

or

![]() $s'$

individually. However, it is possible to eliminate, for instance,

$s'$

individually. However, it is possible to eliminate, for instance,

![]() $s'$

. By applying the material derivative to (3.9b

) and using ((2.9c

), (3.3), (3.9d

)) to eliminate entropy fluctuations, a two-by-two system can be formulated with

$s'$

. By applying the material derivative to (3.9b

) and using ((2.9c

), (3.3), (3.9d

)) to eliminate entropy fluctuations, a two-by-two system can be formulated with

![]() $p'$

and

$p'$

and

![]() $\delta '$

as the only unknowns

$\delta '$

as the only unknowns

\begin{align}& \square p' = \left [-\left (\overline {\mu _b}+\frac {4}{3}\overline {\mu }\right )+\frac {\overline {\lambda }\,\overline {T}}{\overline {c}^2}\left (\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {g}-\overline {\varGamma }^2\right )\right ]\Delta \delta '+\frac {\overline {\lambda }\,\overline {T}\,\overline {g}}{\overline {p}\,\overline {c}^2} \Delta \frac {\textrm{d}p'}{\textrm{d}t}, \end{align}

\begin{align}& \square p' = \left [-\left (\overline {\mu _b}+\frac {4}{3}\overline {\mu }\right )+\frac {\overline {\lambda }\,\overline {T}}{\overline {c}^2}\left (\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {g}-\overline {\varGamma }^2\right )\right ]\Delta \delta '+\frac {\overline {\lambda }\,\overline {T}\,\overline {g}}{\overline {p}\,\overline {c}^2} \Delta \frac {\textrm{d}p'}{\textrm{d}t}, \end{align}

in which a d’Alembertian – or wave – operator based on the mean isentropic sound speed has been defined for compactness

Equations ((5.1a

), (5.1b

)) is a closed system describing how

![]() $\delta '$

and

$\delta '$

and

![]() $p'$

are coupled in a viscous and heat-conducting non-ideal fluid. Seeking the solutions of

$p'$

are coupled in a viscous and heat-conducting non-ideal fluid. Seeking the solutions of

![]() $p'$

and

$p'$

and

![]() $\delta '$

as plane waves allows us to continue the calculations

$\delta '$

as plane waves allows us to continue the calculations

with amplitudes

![]() $\tilde {p},\tilde {\delta } \in \mathbb{C}$

, wave vector

$\tilde {p},\tilde {\delta } \in \mathbb{C}$

, wave vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{k} \in \mathbb{R}^3$

and angular frequency of the irrotational modes

$\boldsymbol{k} \in \mathbb{R}^3$

and angular frequency of the irrotational modes

![]() $\varOmega (\boldsymbol{k}) \in \mathbb{C}$

, which is a function of

$\varOmega (\boldsymbol{k}) \in \mathbb{C}$

, which is a function of

![]() $\boldsymbol{k}$

to be determined. Injection of ((5.3a

), (5.3b

)) into ((5.1a

), (5.1b

)) and elimination of

$\boldsymbol{k}$

to be determined. Injection of ((5.3a

), (5.3b

)) into ((5.1a

), (5.1b

)) and elimination of

![]() $\tilde {p}$

and

$\tilde {p}$

and

![]() $\tilde {\delta }$

yields

$\tilde {\delta }$

yields

which is a third-order polynomial in

![]() $X$

$X$

expressed as a function of non-dimensional numbers

![]() $\varPi$

,

$\varPi$

,

![]() $\varLambda$

,

$\varLambda$

,

![]() ${B}$

and

${B}$

and

![]() $\varTheta$

previously introduced in § 3.4.

$\varTheta$

previously introduced in § 3.4.

The roots of (5.4) provide the three dispersion relations,

![]() $\varOmega (\boldsymbol{k} )$

, that characterise the three pressure-entropy modes. Once these roots have been obtained it is possible to compute the exact expressions relating the pressure, entropy and divergence fields, ((3.3), (3.16b

), (5.1a

))

$\varOmega (\boldsymbol{k} )$

, that characterise the three pressure-entropy modes. Once these roots have been obtained it is possible to compute the exact expressions relating the pressure, entropy and divergence fields, ((3.3), (3.16b

), (5.1a

))

\begin{align}& \frac {\tilde {s}}{\overline {\varGamma }\,\overline {C_v}} = \frac {1}{\varTheta }\left (\frac {\tilde {p}}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {p}}+\frac {i}{X}\frac {\tilde {\delta }}{\lVert \boldsymbol{k}\rVert \overline {c}}\right )\!. \end{align}

\begin{align}& \frac {\tilde {s}}{\overline {\varGamma }\,\overline {C_v}} = \frac {1}{\varTheta }\left (\frac {\tilde {p}}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {p}}+\frac {i}{X}\frac {\tilde {\delta }}{\lVert \boldsymbol{k}\rVert \overline {c}}\right )\!. \end{align}

The irrotational velocity is also obtained from ((3.5a ), (3.6b )) as

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{u}_{\delta }^{\prime} = \frac {-i\delta '}{\lVert \boldsymbol{k}\rVert ^2} \begin{pmatrix} k_x\\ k_y \\ k_z \end{pmatrix} . \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{u}_{\delta }^{\prime} = \frac {-i\delta '}{\lVert \boldsymbol{k}\rVert ^2} \begin{pmatrix} k_x\\ k_y \\ k_z \end{pmatrix} . \end{equation}

The three roots,

![]() $X$

, can be analytically obtained using Cardano’s method (see Appendix A). However, these analytical expressions are too complex to permit simple interpretation. Therefore, in the following discussion, several roots will be described based on the values of various non-dimensional numbers. Before attempting to graphically analyse the three general roots of (5.4) as functions of all non-dimensional numbers, it is pedagogically useful to first explore three simple asymptotic cases of increasing complexity, namely:

$X$

, can be analytically obtained using Cardano’s method (see Appendix A). However, these analytical expressions are too complex to permit simple interpretation. Therefore, in the following discussion, several roots will be described based on the values of various non-dimensional numbers. Before attempting to graphically analyse the three general roots of (5.4) as functions of all non-dimensional numbers, it is pedagogically useful to first explore three simple asymptotic cases of increasing complexity, namely:

-

(i) inviscid (

$\varPi =0$

) and non-conducting (

$\varPi =0$

) and non-conducting (

$\varLambda =0$

) fluid;

$\varLambda =0$

) fluid; -

(ii) viscous (

$\varPi \neq 0$

) and non-conducting (

$\varPi \neq 0$

) and non-conducting (

$\varLambda =0$

) fluid;

$\varLambda =0$

) fluid; -

(iii) inviscid (

$\varPi =0$

) and conducting (

$\varPi =0$

) and conducting (

$\varLambda \neq 0$

) fluid.

$\varLambda \neq 0$

) fluid.

Unless otherwise stated,

![]() ${B}$

and

${B}$

and

![]() $\varTheta$

are assumed to be non-zero finite numbers. Only after considering these simple asymptotic cases will the simultaneous effects of viscosity and heat conduction in a fluid be examined. Throughout these cases, most of the angular frequencies will fall into two generic categories: entropy-like and acoustic-like. An entropy-like angular frequency is characterised by a zero real part (indicating a mode advected by the mean flow) and a negative imaginary part. Conversely, an acoustic-like angular frequency is characterised by a pair of real parts with equal magnitude but opposite signs, along with a negative imaginary part. These categories are more thoroughly discussed in Appendix B.

$\varTheta$

are assumed to be non-zero finite numbers. Only after considering these simple asymptotic cases will the simultaneous effects of viscosity and heat conduction in a fluid be examined. Throughout these cases, most of the angular frequencies will fall into two generic categories: entropy-like and acoustic-like. An entropy-like angular frequency is characterised by a zero real part (indicating a mode advected by the mean flow) and a negative imaginary part. Conversely, an acoustic-like angular frequency is characterised by a pair of real parts with equal magnitude but opposite signs, along with a negative imaginary part. These categories are more thoroughly discussed in Appendix B.

5.1. Inviscid and non-conducting regime

By assuming an inviscid (

![]() $\varPi =0$

) and non-conducting (

$\varPi =0$

) and non-conducting (

![]() $\varLambda =0$

) fluid, the polynomial (5.4) is drastically simplified

$\varLambda =0$

) fluid, the polynomial (5.4) is drastically simplified

which therefore admits three roots. The first two roots correspond to acoustic-like modes while the last one to an entropy-like mode

Indeed, they precisely coincide with classical pressure and entropy modes of the Euler system that have been described by Kovásznay (Reference Kovásznay1953) for a perfect gas. Equations ((3.9c ), (5.1b )) lead, for a non-conducting and inviscid fluid, to

Similarly, the vorticity modes from § 4 (

![]() $\textrm{d} \boldsymbol{\omega }^{\prime}/\textrm{d}t = 0$

) were recovered and remained identical to Kovásznay’s pressure, entropy and vorticity modes in perfect gases. This result is fully consistent with the findings of Alferez & Touber (Reference Alferez and Touber2017) and Touber & Alferez (Reference Touber and Alferez2019) concerning inviscid and non-conducting modes in non-ideal fluids.

$\textrm{d} \boldsymbol{\omega }^{\prime}/\textrm{d}t = 0$

) were recovered and remained identical to Kovásznay’s pressure, entropy and vorticity modes in perfect gases. This result is fully consistent with the findings of Alferez & Touber (Reference Alferez and Touber2017) and Touber & Alferez (Reference Touber and Alferez2019) concerning inviscid and non-conducting modes in non-ideal fluids.

5.2. Viscous and non-conducting regime

From a pedagogical standpoint, the inviscid assumption is more easily relaxed. Therefore, the fluid is now assumed to be viscous (

![]() $\varPi \neq 0$

) while it is still considered to be non-conducting (

$\varPi \neq 0$

) while it is still considered to be non-conducting (

![]() $\varLambda =0$

). Hence, (5.4) reduces to

$\varLambda =0$

). Hence, (5.4) reduces to

This asymptotic case is a generalisation of classical works on acoustic attenuation – e.g. Stokes (Reference Stokes2009) – to an arbitrary EOS with non-zero bulk viscosity. The roots of (5.11) are a pair of acoustic-like and one entropy-like angular frequencies

The corresponding pressure and entropy equations derived from ((2.9c ), (3.3), (3.9c ), (5.1b )) of a viscous and non-conducting fluid are

\begin{align}& \square p' = \displaystyle \frac {\overline {\mu _b}+\dfrac {4}{3}\overline {\mu }}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {p}}\frac {\textrm{d}\Delta p'}{\textrm{d}t}, \end{align}

\begin{align}& \square p' = \displaystyle \frac {\overline {\mu _b}+\dfrac {4}{3}\overline {\mu }}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {p}}\frac {\textrm{d}\Delta p'}{\textrm{d}t}, \end{align}

Clearly the entropy mode is unchanged and still coincides with Kovásznay’s entropy mode. The pressure modes gained additional terms that account for additional dispersion and dissipation when compared with Kovásznay’s acoustic modes. Entropy and pressure fluctuations, just as in the inviscid and non-conducting case, remained uncoupled.

As a first approximation, fluids with a large Prandtl number exhibit dominant viscous effects compared with heat conduction, and can therefore be modelled as viscous and non-conducting fluids over short time scales. Assuming a sufficiently large wavelength such that

![]() $ 1 \gt {{B}}\! \varPi$

, the ratio of the imaginary parts of the angular frequencies from the acoustic and vorticity modes is

$ 1 \gt {{B}}\! \varPi$

, the ratio of the imaginary parts of the angular frequencies from the acoustic and vorticity modes is

![]() ${{B}}/2$

. This demonstrates that a large bulk-to-shear viscosity ratio leads to a significant difference in the attenuation of the acoustic and vorticity modes. Furthermore, due to their negligible thermal conductivity, these large Prandtl number fluids actually support a Kovásznay’s passively advected entropy mode.

${{B}}/2$

. This demonstrates that a large bulk-to-shear viscosity ratio leads to a significant difference in the attenuation of the acoustic and vorticity modes. Furthermore, due to their negligible thermal conductivity, these large Prandtl number fluids actually support a Kovásznay’s passively advected entropy mode.

5.3. Inviscid and conducting regime

Now the opposite situation is considered and the focus is set on the effect of heat conduction. Under the assumptions of an inviscid (

![]() $\varPi = 0$

) and conducting fluid (

$\varPi = 0$

) and conducting fluid (

![]() $\varLambda \neq 0$

) the pressure and entropy governing equations derived from ((3.9b

), (3.9c

), (5.1b

)) are

$\varLambda \neq 0$

) the pressure and entropy governing equations derived from ((3.9b

), (3.9c

), (5.1b

)) are

\begin{align}& \overline {\rho } \overline {T}\frac {\textrm{d}s'}{\textrm{d}t} =\displaystyle \frac {\overline {\lambda }\,\overline {\varGamma }\,\overline {T}}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {p}}\Delta p' + \left (1-\frac {\overline {\varGamma }^2}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {g}}\right )\frac {\overline {\lambda }\,\overline {T}}{\overline {C_v}}\Delta s', \\[9pt] \nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align}& \overline {\rho } \overline {T}\frac {\textrm{d}s'}{\textrm{d}t} =\displaystyle \frac {\overline {\lambda }\,\overline {\varGamma }\,\overline {T}}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {p}}\Delta p' + \left (1-\frac {\overline {\varGamma }^2}{\overline {\gamma _s}\,\overline {g}}\right )\frac {\overline {\lambda }\,\overline {T}}{\overline {C_v}}\Delta s', \\[9pt] \nonumber \end{align}

in which a qualitatively different behaviour is found when compared with the non-conducting previous cases. While the pressure equation remained autonomous the entropy is now enslaved to the pressure field. Contrarily to previous cases,

![]() $p'$

and

$p'$

and

![]() $s'$

are not necessarily independent fields. Under the present assumptions the third-order polynomial (5.4) reduces to

$s'$

are not necessarily independent fields. Under the present assumptions the third-order polynomial (5.4) reduces to

The three roots

![]() $X$

can be analytically obtained via Cardano’s method. However, the interpretation of these analytical expressions is difficult. Instead, four simplified cases are investigated:

$X$

can be analytically obtained via Cardano’s method. However, the interpretation of these analytical expressions is difficult. Instead, four simplified cases are investigated:

![]() $\varTheta =0$

,

$\varTheta =0$

,

![]() $\varTheta =1$

,

$\varTheta =1$

,

![]() $\varLambda \gg 1$

and

$\varLambda \gg 1$

and

![]() $\varLambda \ll 1$

. The first and second cases correspond to the bounds of the inequality (2.6c

) and will be shown to produce simple analytic angular frequencies. The third and fourth cases will be approached by truncated Taylor series. Then the general case will be graphically investigated.

$\varLambda \ll 1$

. The first and second cases correspond to the bounds of the inequality (2.6c

) and will be shown to produce simple analytic angular frequencies. The third and fourth cases will be approached by truncated Taylor series. Then the general case will be graphically investigated.

5.3.1. Roots when

$\varTheta = 0$

$\varTheta = 0$

From (5.15) the value

![]() $\varTheta =0$

corresponds to the lower bound of (2.6c

). It can be achieved by, e.g. setting

$\varTheta =0$

corresponds to the lower bound of (2.6c

). It can be achieved by, e.g. setting

![]() $\overline {\varGamma } = 0$

. Examining ((3.9c

), (3.9d

)) with this assumption shows that the dissipation due to heat conduction is entirely absent from the pressure equation and that entropy and pressure fluctuations are uncoupled. It yields a very simple set of roots

$\overline {\varGamma } = 0$

. Examining ((3.9c

), (3.9d

)) with this assumption shows that the dissipation due to heat conduction is entirely absent from the pressure equation and that entropy and pressure fluctuations are uncoupled. It yields a very simple set of roots

The first two roots exactly correspond to Kovásznay’s acoustic modes. Heat conduction effects are only found to produce an attenuation on the entropy-like mode. From (3.15) this indicates that, for non-ideal fluids with

![]() $C_p \approx C_v$

(liquid phase), the dissipation tends to be predominantly allocated to the entropy-like mode.

$C_p \approx C_v$

(liquid phase), the dissipation tends to be predominantly allocated to the entropy-like mode.

5.3.2. Roots when

$\varTheta = 1$

$\varTheta = 1$

The opposite case in which the dissipation due to heat conduction is entirely apportioned to the acoustic-like modes is obtained by setting

![]() $\varTheta = 1$

. In contrast with the previous case, it corresponds to the upper bound of (2.6c

) and also yields a very simple set of exact roots

$\varTheta = 1$

. In contrast with the previous case, it corresponds to the upper bound of (2.6c

) and also yields a very simple set of exact roots

![]() $X$

. Examining ((5.14a

), (5.14b

)) with this assumption shows that

$X$

. Examining ((5.14a

), (5.14b

)) with this assumption shows that

![]() $p'$

and

$p'$

and

![]() $s'$

are coupled. In this case (5.15) admits the following set of roots:

$s'$

are coupled. In this case (5.15) admits the following set of roots:

\begin{equation} X = \left \{ \begin{array}{ll} \pm \sqrt {\displaystyle 1-\left (\frac {\varLambda }{2}\right )^2} - i\displaystyle \frac {\varLambda }{2},\\ 0.\end{array} \right . \end{equation}

\begin{equation} X = \left \{ \begin{array}{ll} \pm \sqrt {\displaystyle 1-\left (\frac {\varLambda }{2}\right )^2} - i\displaystyle \frac {\varLambda }{2},\\ 0.\end{array} \right . \end{equation}

The first two roots correspond to damped downstream and upstream acoustic-like modes. Heat conduction effects are absent from the entropy-like mode. From (3.15) this indicates that for non-ideal fluids with

![]() $C_p \gg C_v$

(near critical point), the dissipation tends to be predominantly allocated to the acoustic-like modes.

$C_p \gg C_v$

(near critical point), the dissipation tends to be predominantly allocated to the acoustic-like modes.

5.3.3. Roots when

$\varLambda \ll 1$

$\varLambda \ll 1$

A weakly heat-conducting fluid, or a fluctuation with very large wavelength, is approached by

![]() $\varLambda \ll 1$

. The roots of (5.15) are approached with a series expansion around

$\varLambda \ll 1$

. The roots of (5.15) are approached with a series expansion around

![]() $\varLambda = 0$

. Neglecting high-order terms

$\varLambda = 0$

. Neglecting high-order terms

![]() $\mathcal{O} (\varLambda ^{3} )$

allows

$\mathcal{O} (\varLambda ^{3} )$

allows

![]() $X$

to be expressed as

$X$

to be expressed as

\begin{equation} X = \left \{ \begin{array}{ll} \displaystyle \pm \left (1-\frac {1}{8} \varTheta \left (4-3 \varTheta \right )\varLambda ^2\right ) -i\frac {\varTheta \varLambda }{2}+\mathcal{O}\left (\varLambda ^{3}\right ) ,\\ -i \left (1-\varTheta \right )\varLambda +\mathcal{O}\left (\varLambda ^{3}\right ).\end{array} \right . \end{equation}

\begin{equation} X = \left \{ \begin{array}{ll} \displaystyle \pm \left (1-\frac {1}{8} \varTheta \left (4-3 \varTheta \right )\varLambda ^2\right ) -i\frac {\varTheta \varLambda }{2}+\mathcal{O}\left (\varLambda ^{3}\right ) ,\\ -i \left (1-\varTheta \right )\varLambda +\mathcal{O}\left (\varLambda ^{3}\right ).\end{array} \right . \end{equation}

All three modes are now simultaneously attenuated due to the negative imaginary components of the angular frequencies. By expanding the exact roots from Cardano’s method up to

![]() $\mathcal{O} (\varLambda ^{20} )$

(not shown here) it is found that additional terms in the two acoustic-like modes can be either real or imaginary, indicating that they introduce deviations in both dispersion and dissipation when compared with the present truncated solution. However, additional terms in the third entropy-like mode are purely imaginary, indicating that the real part responsible for the wave propagation seems exact, at least up to an error

$\mathcal{O} (\varLambda ^{20} )$

(not shown here) it is found that additional terms in the two acoustic-like modes can be either real or imaginary, indicating that they introduce deviations in both dispersion and dissipation when compared with the present truncated solution. However, additional terms in the third entropy-like mode are purely imaginary, indicating that the real part responsible for the wave propagation seems exact, at least up to an error

![]() $\mathcal{O} (\varLambda ^{20} )$

. Note that it can clearly be seen that the violation of an inequality among ((2.6a

)–(2.6c

)) indicates either

$\mathcal{O} (\varLambda ^{20} )$

. Note that it can clearly be seen that the violation of an inequality among ((2.6a

)–(2.6c

)) indicates either

![]() $\varTheta \gt 1$

or

$\varTheta \gt 1$

or

![]() $\varTheta \lt 0$

. This would induce a positive imaginary term in the third root, which would be symptomatic of an unstable mode.

$\varTheta \lt 0$

. This would induce a positive imaginary term in the third root, which would be symptomatic of an unstable mode.

5.3.4. Roots when

$\varLambda \gg 1$

$\varLambda \gg 1$

Conversely, the assumption

![]() $\varLambda \gg 1$

corresponds to a strongly heat-conducting fluid, or a fluctuation with very short wavelength. Neglecting

$\varLambda \gg 1$

corresponds to a strongly heat-conducting fluid, or a fluctuation with very short wavelength. Neglecting

![]() $\mathcal{O} (\varLambda ^{-3} )$

terms in a series expansion around

$\mathcal{O} (\varLambda ^{-3} )$

terms in a series expansion around

![]() $\varLambda =\infty$

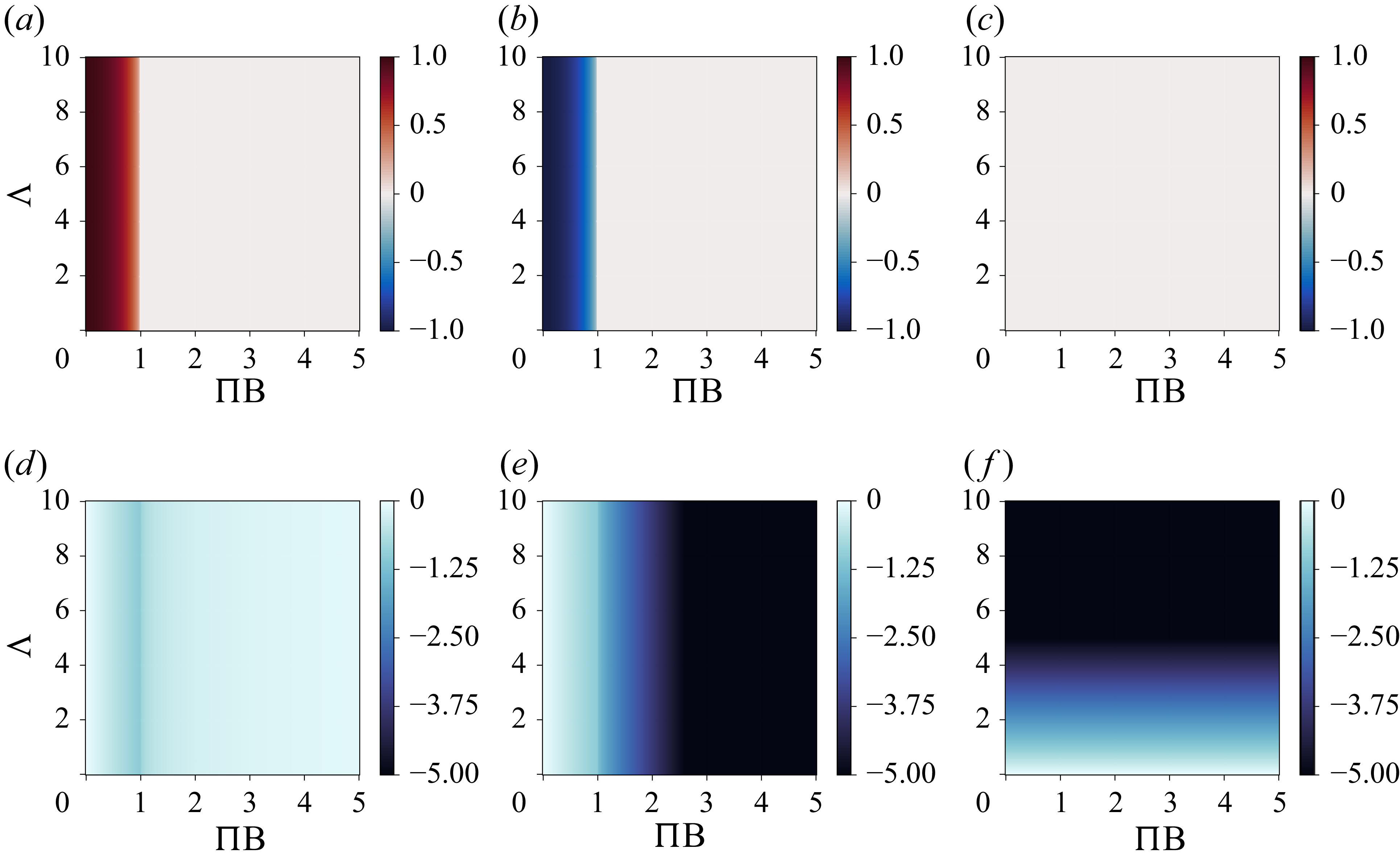

yields the roots of (5.15)