Introduction

Online slots and electronic gambling machines are associated with an elevated risk of harm relative to other gambling activities (Breen and Zimmerman, Reference Breen and Zimmerman2002; MacLaren, Reference MacLaren2016; Delfabbro et al., Reference Delfabbro, King, Browne and Dowling2020; Allami et al., Reference Allami, Hodgins, Young, Brunelle, Currie, Dufour, Flores-Pajot and Nadeau2021; Browne et al., Reference Browne, Delfabbro, Thorne, Tulloch, Rockloff, Hing, Dowling and Stevens2023). This is often attributed to design features that support rapid, continuous and immersive gambling, or that encourage erroneous beliefs about gambling outcomes or the degree of control that an individual has over chance events (Schüll, Reference Schüll2012; Murch and Clark, Reference Murch and Clark2016; Harris and Griffiths, Reference Harris and Griffiths2018; Yücel et al., Reference Yücel, Carter, Harrigan, van Holst and Livingstone2018; Myles et al., Reference Myles, Carter and Yücel2019; Schluter and Hodgins, Reference Schluter and Hodgins2019; Newall, Reference Newall2023).

To address these risks, the UK recently introduced regulatory measures for online slots that aim to ‘ensure that products are designed responsibly and to minimise the likelihood that they exploit or encourage problem gambling behaviour’ (UK Gambling Commission, 2021d). These measures included a reduction to the maximum allowable bet size (UK Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, 2018; UK Gambling Commission, 2025), slowing the rate of gambling to a minimum of 2.5 seconds between spins (UK Gambling Commission, 2021b), and a prohibition of features that ‘give the illusion of control’, such as ‘turbo’ or ‘slam stops’ (RTS-14E; UK Gambling Commission, 2021a, 2021d).

These recent reforms also included a ban on celebratory ‘sounds or imagery which give the illusion of a win’ (UK Gambling Commission, 2021c, 2021d). This change was intended to disable ‘losses disguised as wins’ (LDWs), a product design feature that displays celebratory sounds and imagery alongside monetary losses that involve a less-than-stake return (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Harrigan, Sandhu, Collins and Fugelsang2010). LDWs are common in slot gambling products that allow simultaneous bets across multiple ‘paylines’. When one or more of these multiple bets pay out, the return can be less than the total bet on all paylines (i.e., a less-than-stake return) – for example, a £0.50 return on a £1 bet. Although these outcomes result in a net monetary loss, they are typically accompanied by celebratory sound effects and animations. Because these events closely resemble genuine wins, they may foster the illusion that the consumer has won money (i.e., a loss disguised as a win).Footnote 1 This illusion may, in turn, contribute to a behavioural addiction by inflating the frequency of positively reinforced gambles in a manner that is incommensurate with the financial outcomes (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Harrigan, Sandhu, Collins and Fugelsang2010; Yücel et al., Reference Yücel, Carter, Harrigan, van Holst and Livingstone2018; Myles et al., Reference Myles, Carter and Yücel2019).

The concern that LDWs are mistaken for genuine wins is corroborated by empirical findings. Analysis of ecological gambling data has demonstrated that people are more likely to continue gambling following both wins and LDWs relative to unambiguous losses (Leino et al., Reference Leino, Torsheim, Pallesen, Blaszczynski, Sagoe and Molde2016). Randomised experiments have demonstrated that people tend to overestimate how often genuine wins occur when LDWs are included in simulated gambling tasks, whereas estimates are comparatively accurate when LDWs are absent (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Yazdani, Ayer, Kalvapalle, Brown, Stapleton, Brown and Harrigan2017; Graydon et al., Reference Graydon, Dixon, Gutierrez, Stange, Larche and Kruger2021; Myles et al., Reference Myles, Bennett, Carter, Yücel, Albertella, De Lacy-Vawdon and Livingstone2023). Additionally, a brief explanatory video about LDWs inoculates people against these errors (Graydon et al., Reference Graydon, Dixon, Harrigan, Fugelsang and Jarick2017), as does pairing these events with loss-associated and negative sound effects (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Collins, Harrigan, Graydon and Fugelsang2015). LDWs also evoke brain activity related to reward-processing (Myles et al., Reference Myles, Carter, Yücel and Bode2024) and measures of physiological arousal (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Harrigan, Sandhu, Collins and Fugelsang2010) similar to genuine wins and unlike losses (although c.f. null findings; Peterburs et al., Reference Peterburs, Suchan and Bellebaum2013; Lole et al., Reference Lole, Gonsalvez, Barry and Blaszczynski2014).

This literature supports the UK Gambling Commission’s decision to introduce a ‘permanent ban on features that […] celebrate losses as wins’ (UK Gambling Commission, 2021b). The relevant clause, requirement 14F of the Remote Gambling and Software Technical Standards (RTS-14F; UK Gambling Commission, 2021d), states that a product must ‘not celebrate a return which is less than or equal to the total stake gambled’. This requirement is provided alongside ‘implementation guidance’ clarifying that ‘celebrate’ means ‘the use of auditory or visual effects that are associated with a win are not permitted for returns which are less than or equal to [the] last total amount staked’.

We were concerned that this implementation guidance may render the regulation ineffective by inappropriately limiting the definition of the word celebrate, in that it would permit operators to continue using a celebratory sound effect that strongly implies a positive outcome following LDWs, so long as the same sound was not also used following genuine wins. The present work was intended to investigate this issue. We first conducted an environmental scan of popular online slots available in the UK to determine whether our concerns were substantiated. Because judgements about whether a sound effect communicates a positive outcome are inherently subjective, we conducted a pre-registered experiment to assess whether a collection of sounds recorded following less-than-stake returns observed in commercially available online slots were appraised as indicating a positive outcome by a sample of relevant end-users.

Study 1 – online environmental scan

Method

We observed how sound effects were used to indicate gambling outcomes in 26 online slots, developed by 13 software studios, that we identified from a list of the most prominent products across 175 UK websites (iGaming Tracker, retrieved 9 February 2024, see supplementary methods). We excluded roulette, blackjack or slingo products, but included tumble slots.Footnote 2 All observations were recorded between 18 February and 22 March 2024 using the website of a major UK-based online gambling provider. A personal account and personal funds were used to place all bets.

Screen-capture recordings (see Open Science Framework [OSF]) made during fieldwork were then evaluated to determine whether each product complied with the implementation guidance that win-associated auditory effects are not permitted following less-than-stake returns. Each sound associated with a less-than-stake return was then independently and blindly rated by the study authors as either positive, neutral or negative. Three initial disagreements (9 Pots of Gold, Fluffy Favourites and Shaman’s Dream) were subsequently resolved through discussion to reach a consensus appraisal of each sound.

Results

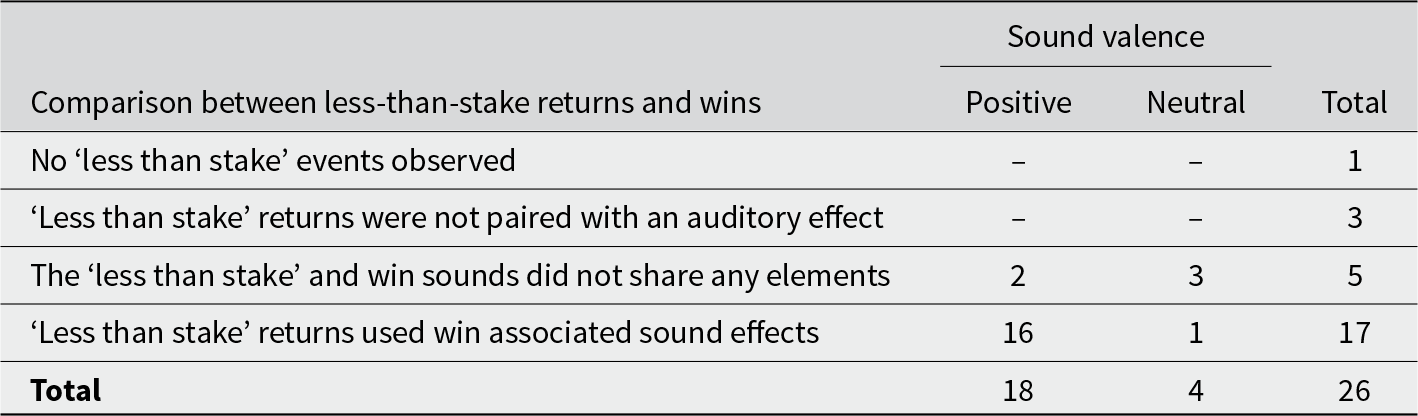

We observed 1,904 bets across 26 slot gambling products, including 203 genuine wins; 197 less-than-stake returns; 48 break-evens; and 1,456 losses. Each product was then classified based on the way sound effects were used following both less-than-stake returns and wins (see Table 1). First, no less-than-stake returns were observed after 200 bets using Gold Cash Free Spins. Second, three products did not use sound effects following less-than-stake returns. Third, five products paired less-than-stake returns with sound effects that were clearly distinct from those associated with genuine wins. Finally, 17 products used sounds following less-than-stake returns that were also associated with a win by that product (likely resulting in LDWs). A common approach was to celebrate wins with a longer sequence of sounds and then include a subset of these sounds following less-than-stake returns. For example, less-than-stake returns may be associated with a chime sound, while wins were followed by a longer sequence of sounds that ended with that same chime sound (e.g., Gold Blitz, Blazing Bison Gold Blitz). Another approach was to use the same sequence of sounds but scale the duration of an element with the magnitude of the payout. In several cases, the entire sound sequence following each type of event was indistinguishable from the other (e.g., Eye of Horus, Bonanza). Finally, of the 22 products that included less-than-stake returns that were paired with sound effects, we determined that 4 used a neutral sound, while 18 used positive or celebratory sounds (see Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of how sound effects were used to indicate less-than-stake returns and wins in the 26 online slots observed for this study

Notes: Comparison between less-than-stake returns and wins – Authors’ comparison between the auditory effects used following less-than-stake returns and genuine wins for each product.

Sound valence – Groups products by the authors’ consensus appraisal of the emotional or informational quality of the less-than-stake return sound sequence as either positive or neutral (there were no negative cases).

A screen capture and audio recording of every outcome described in this table has been made available on the OSF. A more detailed description of each sound effect is provided in the supplementary materials, see Supplementary Table S1.

Study 2 – online experiment

Method

Recruitment

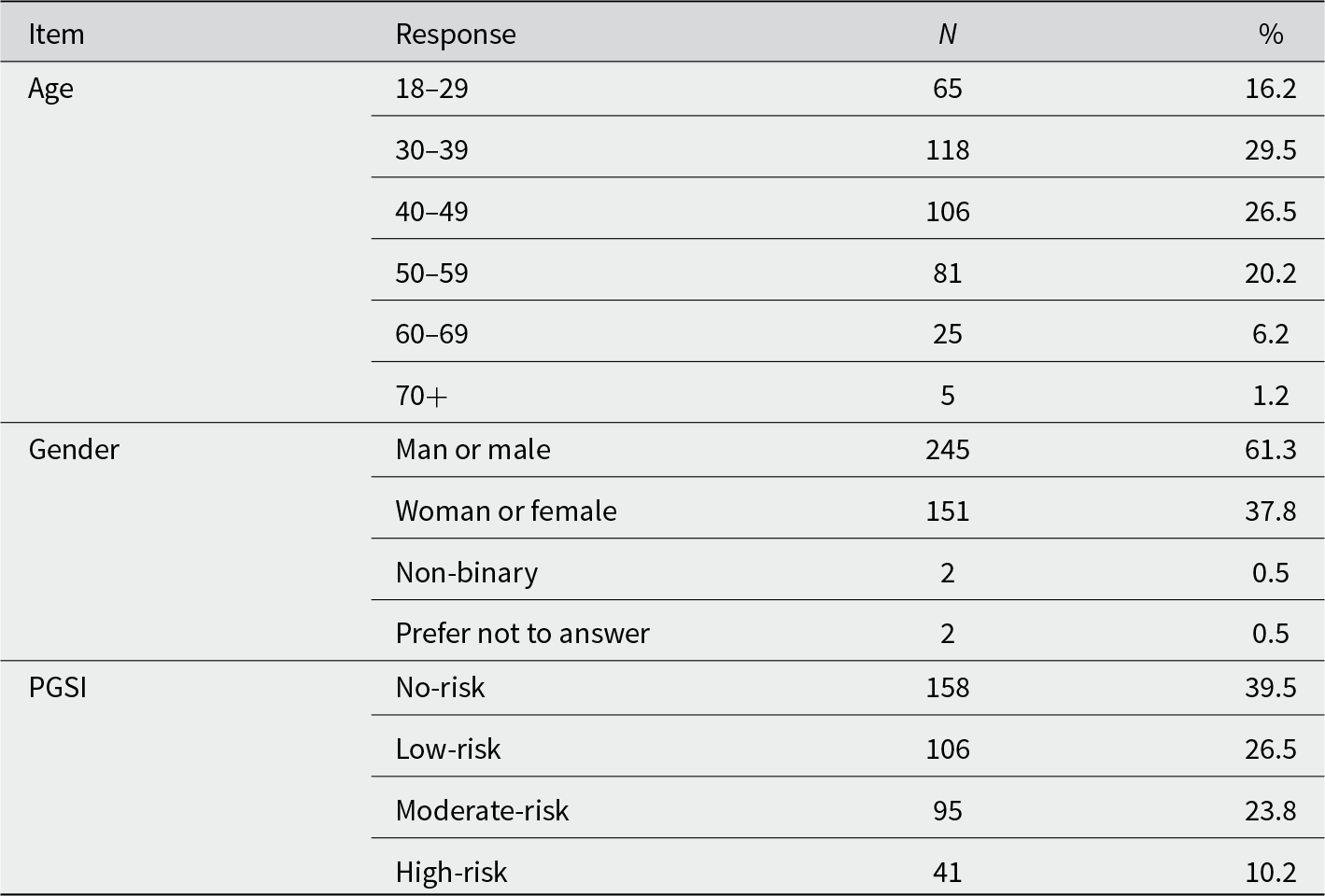

Participants were recruited online via Prolific (www.prolific.com) and paid £1.50 (£8.10 per hour). All participants were UK residents, aged 18+, who had previously gambled using online slots. We pre-registered an intent to recruit 400 participants prior to data-quality exclusions, including a self-reported carelessness check (SRSI Use Me, Meade and Craig, Reference Meade and Craig2012), an audio equipment test (see Supplementary Material) and evidence of inattentive responding (e.g., straight-lining and inconsistent responses; see OSF). All participants’ data passed these quality checks and were retained for analysis. Participant demographics are summarised below in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary statistics describing participant demographics

Procedure

Participants accessed the study online via a web browser. All participants were presented with a plain language description of the research before being asked to provide consent to participate. Consenting participants were presented with a listening task (described below), before being asked to complete a demographic survey (age and gender), the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI, Ferris and Wynne, Reference Ferris and Wynne2001), a self-reported carelessness check (SRSI Use Me, Meade and Craig, Reference Meade and Craig2012) and an optional open-text feedback form.

Listening task

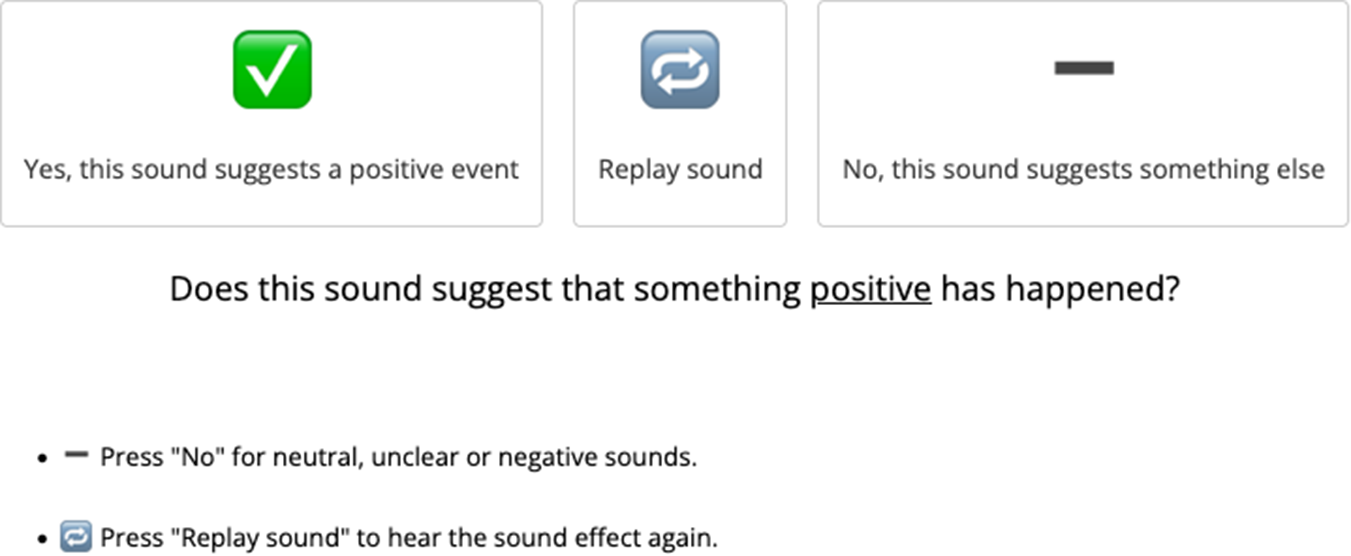

A video demonstration of the listening task and materials to reproduce it has been made available online (see OSF). The task was developed in jsPsych (De Leeuw et al., Reference De Leeuw, Gilbert and Luchterhandt2023) and hosted online using JATOS (Lange et al., Reference Lange, Kühn and Filevich2015) and mindprobe (https://mindprobe.eu/). The listening task involved listening to a series of audio recordings and classifying them into one of two categories, as shown in Figure 1. Participants were able to replay each recording as desired before submitting a response.

Figure 1. A screen capture of the display shown to participants on each listening trial.

The experiment included 60 unique audio recordings arranged in randomised order across 2 blocks for a total of 120 trials. We included recordings of sounds associated with wins and less-than-stake returns selected from our observations of online slots in study 1. Products that did not use sound effects following less-than-stake returns were excluded (see Supplementary Table S1), as were any recordings that contained too much contamination from background music or unrelated sound effects. Several slots used the same sound effects (see Supplementary Table S1). In these cases, we selected the clearer recordings. To increase the range of stimuli presented, four additional sounds were included from previous ad-hoc observations (Blue Wizard, Bison Moon, Pride of Persia and The Goonies).

To provide an objective point of reference, we also included positive and negative sounds collected from non-gambling settings. Positive sounds included a celebratory fanfare from the game show Wheel of Fortune, the Apple Pay successful payment sound and the coin collected sound from the classic video game Super Mario Bros. Negative sounds included the Microsoft Windows XP ‘Critical Stop’ system sound, a loud car horn, the Wilhelm Scream and a sad trombone. In total, we included 6 positive non-slot sounds and 16 negative non-slot sounds. All sound files used in the experiment are available on the OSF.

Hypotheses

We pre-registered the hypothesis that, on average, participants would appraise sounds associated with less-than-stake returns as positive (i.e., that the probability of a positive response would be both greater than 0.5 and greater than the average response to negative sound effects). We also pre-registered that the average responses to other sound categories would match their category labels. Finally, we pre-registered a hypothesis relating to each individual sound effect included in the experiment. These hypotheses were based on our consensus appraisal of the sound effects reported in study 1 (see Supplementary Table S1). This process identified four less-than-stake stimuli we felt would be unlikely to elicit a positive response on average. For these four products (9 Pots of Gold, Blue Wizard, Fluffy Favourites, Big Bass Bonanza), we hypothesised that the estimated probability that an average participant would rate the sound as positive would be less than 0.5. All remaining less-than-stake stimuli were hypothesised to elicit a positive response on average (i.e., greater than 0.5). All hypotheses relating to the remaining stimuli were consistent with their category labels. All hypotheses were pre-registered on the OSF.

Analysis

We did not depart from our pre-registered analysis plan. We fit a multilevel Bayesian logistic regression model to account for the repeated measures of participant responses and the nested structure of stimuli within categories. The final model structure included fixed effects by sound category, correlated varying slopes by participant and category, and varying intercepts by stimulus. We set uninformative priors that did not provide information related to the research hypotheses. The supplementary materials for this study include additional sensitivity analyses, all of which were consistent with findings reported in the primary paper. All data processing, analyses and visualisation were performed in R (R Core Team, 2025) and contributed packages (Wickham, Reference Wickham2016, Reference Wickham2023; Rinker and Kurkiewicz, Reference Rinker and Kurkiewicz2018; Müller, Reference Müller2020; Kay, Reference Kay2024; Vehtari et al., Reference Vehtari, Gabry, Magnusson, Yao, Bürkner, Paananen and Gelman2024; Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Dowle, Srinivasan, Gorecki, Chirico, Hocking, Schwendinger and Krylov2025; Gabry et al., Reference Gabry, Češnovar, Johnson and Bronder2025). Models were fit using Stan (Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Gelman, Hoffman, Lee, Goodrich, Betancourt, Brubaker, Guo, Li and Riddell2017) and brms (Bürkner, Reference Bürkner2017), and achieved good convergence (all ![]() $\hat R\, \lt \,1.01$, bulk and tail effective sample sizes >1,000) (Vehtari et al., Reference Vehtari, Gelman, Simpson, Carpenter and Bürkner2021).

$\hat R\, \lt \,1.01$, bulk and tail effective sample sizes >1,000) (Vehtari et al., Reference Vehtari, Gelman, Simpson, Carpenter and Bürkner2021).

Results

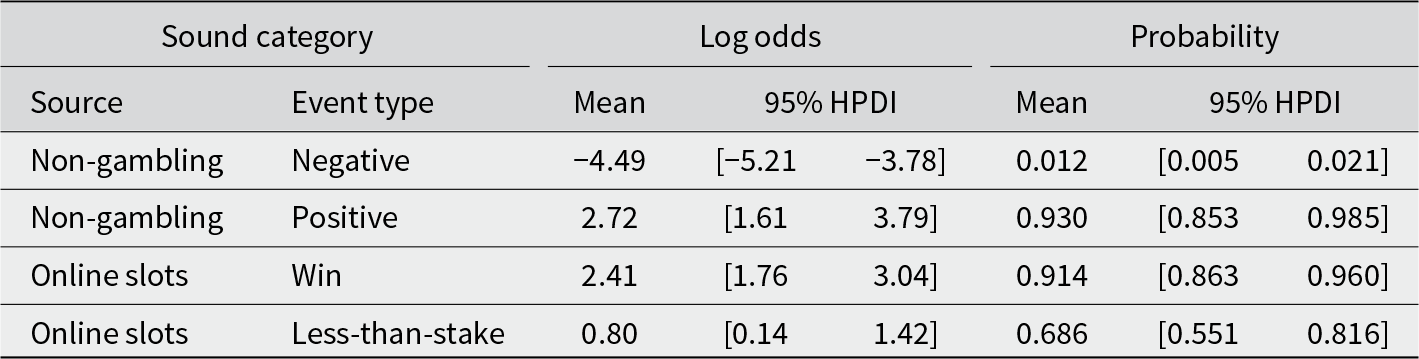

Table 3 reports posterior estimates for the model estimated marginal mean probability of a positive response to each sound category. As predicted, participants were more likely to classify less-than-stake sounds as conveying positive outcome information rather than ‘something else’, and more likely to rate these sounds as positive relative to negative sounds.

Table 3. Posterior estimates for model fixed effects

Note: These fixed effects represent the marginal response to each category of sound effect, or an average participant’s response to an average stimulus.

Participants classified 15 of the 19 less-than-stake sound effects included in this study as positive on average (See Figure 2). Conversely, four less-than-stake sounds were more likely to be rated as ‘something else’ on average (Blue Wizard, 9 Pots of Gold, Fluffy Favourites, Big Bass Bonanza). All results were consistent with our appraisal of the sound effects included in study 1. All remaining sound effects, both individually and on average by category, were rated as consistent with their category labels. All pre-registered hypotheses were therefore supported.

Figure 2. Average proportion of positive responses to each sound effect.

Discussion

This study investigated whether 26 popular online slots adhered to recently introduced UK regulations intended to permanently ban LDWs (RTS requirement 14F). Contrary to regulatory guidance, of the 26 products observed, 17 used win-associated sound effects following less-than-stake returns. Moreover, 18 products used sound effects following less-than-stake returns that we judged to signal a positive outcome. These assessments were then independently validated by a sample of 400 UK-based end-users.

The high rate of non-compliance we observed could indicate that monitoring and enforcement efforts have been insufficient. Our results also point to problems with the regulatory guidance itself. One problem is that RTS-14F inappropriately limits the definition of the word celebrate to ‘the use of auditory or visual effects that are associated with a win’. This provides a loophole that allows for technical compliance with the regulation while circumventing its intended effect, because it allows products to continue to use sound effects that strongly signal a positive outcome, so long as they differ from the sound used following a win. A more common observation was that products used partial components of win-associated sound sequences during the celebration of less-than-stake returns. In our view, this is inconsistent with existing implementation guidance and would likely result in LDWs. However, given that it was relatively common, further implementation guidance may be necessary to prevent this practice.

One way to provide unambiguous guidance consistent with the stated intention of RTS-14F would be to provide an independently tested repository of non-celebratory sounds. A more straightforward approach would be to prohibit the use of sound effects following less-than-stake returns altogether. This would require the removal of the current guidance that all returns include a ‘brief sound to indicate the result of the game and transfer to player balance’. During our environmental scan, we observed three products that used silence following less-than-stake returns. In our view, this approach is consistent with the spirit of RTS-14F. However, somewhat paradoxically, it is at odds with the letter of the implementation guidance.

Importantly, neither of these proposals may be sufficient to prevent errors associated with less-than-stake returns. Dixon et al. (Reference Dixon, Collins, Harrigan, Graydon and Fugelsang2015) demonstrated that pairing less-than-stake with a ‘negative’ sound effect substantially reduces LDW-related errors when that same sound is also paired with clear losses. It may therefore be necessary to require that both total losses as well as less-than-stake returns be accompanied by the same negative sound effect. Dixon et al. (Reference Dixon, Collins, Harrigan, Graydon and Fugelsang2015) also found that simply removing sound following LDWs only resulted in a small reduction in the observed incidence of LDW-related errors that was not statistically significant. Moreover, the LDW illusion is still observed in studies where no sound effects follow either wins or LDWs (Myles et al., Reference Myles, Bennett, Carter, Yücel, Albertella, De Lacy-Vawdon and Livingstone2023, Reference Myles, Carter, Yücel and Bode2024). Collectively, these results suggest that simply requiring silence following LDWs may not be sufficient to completely prevent errors caused by LDWs. It may therefore be necessary to supplement these proposals with improvements to the visual information display that includes a salient indication of the net return of each bet (i.e., bet amount minus return), in addition to the gross return, as is required for online betting activity statements in Australia (Behavioural Economics Team of the Australian Government, 2020). Each of these proposed changes should be empirically tested in a realistic setting prior to implementation – including whether a more salient indication of losses could contribute to loss chasing or other adverse consequences.

This research had several limitations. First, our results only pertain to whether UK-based online slots were using positively valenced or win-associated sounds following less-than-stake returns. We did not investigate whether these practices directly contribute to the misunderstanding of LDWs. Second, all observations were made using a single operator’s website. Because operators tend to provide access to the same products, we have assumed that the high rate of non-compliance observed likely applies across operators. However, it is feasible that other operators may have deployed alternate versions of these products that were compliant with RTS-14F. If this is the case, rates of compliance among other operators may well be better than what we observed. Third, participants in study 2 were recruited via a crowdsourcing platform that may not be population representative. Finally, we asked participants to make judgements about the qualitative characteristics of sound effects abstracted from the context in which they were designed to appear. It is possible that participants would experience sounds differently had they been presented in their typical context.

Despite these limitations, these findings present cause for concern that RTS-14F has not achieved its stated aim to ‘permanently ban’ LDWs. We recommend that these measures be more closely monitored and enforced, and guidance rewritten to unambiguously communicate regulatory requirements that will prevent creative (non-)compliance.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2026.10035.

Author contributions

Dan Myles: Conceptualisation; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Software; Resources; Validation; Visualisation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Daniel Bennett: Conceptualisation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing – review & editing.

Philip Newall: Conceptualisation; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Resources; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Funding statement

This research was funded by a startup grant awarded to Dr Philip Newall from the School of Psychological Science at the University of Bristol. The funders had no influence over the design, execution, analysis, interpretation of data or writing of this report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in relation to the publication of this article.

Declarations of interests

Dan Myles is currently employed as a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Melbourne. This position is partially funded through an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship awarded to Daniel Bennett (FT240100555). Dan has previously received funding from the New South Wales Department of Health, Office of Responsible Gambling, which derives resources for research purposes through hypothecated taxes on gambling revenue, as well as the Australian Government Research Training Program, to support his PhD training. Dan Myles has held previous positions at the Australian Gambling Research Centre and the Behavioural Insights Team. Neither of these organisations were involved in the current study, nor did they provide funding or in-kind support.

Daniel Bennett has previously received research funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council, the Monash-Warwick Alliance and the Australian-American Association, as well as funding from the Australian Government Research Training program to support his PhD training. These organisations did not provide funding or in-kind support towards the current research. He currently receives salary support from an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT240100555).

Philip Newall is a member of the Advisory Board for Safer Gambling – an advisory group of the Gambling Commission in Great Britain. In the last 3 years, Philip Newall has contributed to research projects funded by the Academic Forum for the Study of Gambling, Alberta Gambling Research Institute, BA/Leverhulme, Canadian Institute for Health Research, Clean Up Gambling, Gambling Research Australia and the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation. Philip Newall has received honoraria for reviewing from the Academic Forum for the Study of Gambling and the Belgium Ministry of Justice, travel and accommodation funding from the Alberta Gambling Research Institute and the Economic and Social Research Institute and open access fee funding from the Academic Forum for the Study of Gambling and Greo Evidence Insights.

Ethics review and approval

This study was reviewed and received a favourable ethics opinion by the School of Psychological Science Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Bristol (code: 17648).

Consent to participate

All participants were presented with a plain language statement describing the study prior to providing consent. All participants for whom data were recorded provided explicit consent to participate in the study as it was described.

Consent for publication

The plain language explanatory statement presented to participants prior to consent included a statement outlining that the study data would be analysed and ‘reported in an appropriate scientific journal or presented at a scientific meeting’.

Open science practice

OSF project page: https://osf.io/deuj5/.

Pre-registration

For study 2, we pre-registered our hypotheses, research design, data-exclusion plan and some basic information about our intended analyses via the Open Science Framework. A de-identified copy of this document was made available to peer-reviewers during the review process.

Availability of data, materials and analysis scripts

The code for the jsPsych task used in study 2, as well as de-identified data, analysis scripts and model code necessary to reproduce our analyses have been made available on the OSF. A de-identified version of this repository and all files was made available to peer-reviewers during the review process.

Consent to open data

All participants provided consent for open sharing of data. Our participant information and consent form stated that ‘the anonymized study data collected from you as part of the study will be made available as “open data”’. Participants were also informed in plain language what open data refers to, and the potential benefits of open data practices.