1. Introduction

Suspense is a key aesthetic feature of media in general (Abuhamdeh et al., Reference Abuhamdeh, Csikszentmihalyi and Jalal2015) and text, our primary interest in this paper, in particular. The present study attempts to establish whether information structural features of a text can be considered a respectable predictor of suspense, as suggested specifically by the recent proposal of Köppe and Onea (Reference Köppe and Onea2023).

The nature of suspense, defined for example as a pleasant excitement (Zillmann, Reference Zillmann, Bryant and Zillmann1991, 282), is a cognitive and emotive phenomenon usually associated with hope and fear (Ortony et al., Reference Ortony, Clore and Collins1990). It has been studied extensively from various perspectives, including psychology (Bálint et al., Reference Bálint, Kuijpers, Doicaru, Hakemulder, Kuijpers, Tan, Bálint and Doicaru2017; Lehne et al., Reference Lehne, Engel, Rohrmeier, Menninghaus, Jacobs and Koelsch2015), neurology (Bezdek et al., Reference Bezdek, Gerrig, Wenzel, Shin, Pirog Revill and Schumacher2015) and philosophy (Uidhir, Reference Uidhir2011). In this paper, we will not have much to contribute to a definition of suspense (at any level of analysis) and simply assume that readers of a text will be able to recognize when and to what degree it is suspenseful, thus making the suspense levels of a text measurable at the behavioral level (Bentz et al., Reference Bentz, Cortez Espinoza, Simeonova, Köppe and Onea2024). Instead, we will focus on the question what makes a text suspenseful. Thereby, we adopt a working definition of suspense as an emotional state of excitement and anticipation directed toward a specific, uncertain future outcome of the plot.

While the question is mostly not phrased specifically in the terms above, it is fair to suggest that there is near-complete agreement in the literature that the emergence of suspense is at the interplay between the information presented by the text (the content) and the way information is presented or revealed (a phenomenon that we will refer to broadly as information structure). In other words, what matters is which information is conveyed and how, specifically in terms of temporal development. Notions such as ‘outcome value’ and ‘outcome delay’ (Brewer & Lichtenstein, Reference Brewer and Lichtenstein1982; Doicaru, Reference Doicaru2016), ‘outcome uncertainty’ (Alavy et al., Reference Alavy, Gaskell, Leach and Szymanski2010) or progressively transferred information (Ely et al., Reference Ely, Frankel and Kamenica2015) but also computational models such as Delatorre et al. (Reference Delatorre, León, Gervás and Palomo-Duarte2017) can be naturally integrated into such a framework. Broadly speaking, the text makes the reader cope with danger, threats and similar situations that are characterized by incomplete information and some sense of anticipation of asymmetric possible outcomes: asymmetric because readers have various preferences regarding the possible outcomes based on the content of the text. It is easy to see that such a type of analysis of suspense can carry over to other media as well, as long as information is presented over time and some kind of content can be established.

In linguistics, partly due to a natural focus on individual utterances or sentences, information structure is usually understood as an abstract, grammatically encoded structural characteristic of utterances (Krifka, Reference Krifka2008). This raises the question to what extent a model of text structure and coherence that centers around a linguistic understanding of information structure, as explicated by linguistic theory, can in fact predict suspense. One well-established class of such theories, going back to Klein and von Stutterheim (Reference Klein and von Stutterheim1991), Ginzburg (Reference Ginzburg1992) and Roberts (Reference Roberts2012a [1996]), is often called erotetic. The term erotetic comes from ancient Greek and means broadly ‘pertaining to questions’. In erotetic theories of discourse structure, questions are treated as shared discourse goals between interlocutors, and discourse structure reflects rational strategies for achieving these goals by establishing intermediate discourse objectives that can be addressed strategically. In other words, understanding the structure of discourse is a matter of understanding the actions of the interlocutors, which is, in turn, closely linked to reconstructing their goals. The information structure of the text is then understood as the way in which a text reflects the questioning strategies that constitute its goals. Thus, the broad information structure of the text is reflected in its erotetic structure. Because goals are naturally aligned with actions, erotetic approaches to discourse are particularly effective in explaining linguistic phenomena in terms of their sensitivity to the question under discussion (QUD), i.e., the immediate discourse goal that individual utterances (or sometimes even larger text segments) address. Examples of this success story include distinguishing between at-issue and not-at-issue meaning components and presupposition projection (Simons et al., Reference Simons, Tonhauser, Beaver, Roberts, Li and Lutz2010; Tonhauser et al., Reference Tonhauser, Beaver, Roberts and Simons2013; Tonhauser et al., Reference Tonhauser, Beaver and Degen2018), analyzing core notions of information structure such as focus or contrastive topic (Büring, Reference Büring2003; Roberts, Reference Roberts2012a) and interpreting the meaning of discourse particles (Beaver & Clark, Reference Beaver and Clark2008; Onea, Reference Onea2016; Onea & Volodina, Reference Onea and Volodina2011; Rojas-Esponda, Reference Rojas-Esponda2014). Additionally, various versions of this approach have been applied in large-scale discourse annotation projects (e.g., Riester et al., Reference Riester, Brunetti, de Kuthy, Adamou, Haude and Vanhove2018).

From this perspective, the broader information structure of a text is naturally captured by erotetic theories of discourse structure, and thus, we may expect that erotetic theories of discourse may be instrumental in capturing narrative suspense. Indeed, the erotetic theories of Carroll (Reference Carroll1996) and Köppe and Onea (Reference Köppe and Onea2023) suggest that information structural features of texts (explicated by the erotetic structure of texts) directly correlate with narrative suspense. This leads us back to our goal, namely to establish to what extent information structural features of a text can predict suspense.

In this paper, we aim to test the validity of an information structural model of suspense. To this end, we first introduce the theoretical framework of erotetic text structure. We then operationalize this theory by defining a measurable ‘activation index’ based on plot-relevant questions. Finally, we report on two empirical studies where we compare the model’s predictions against behavioral suspense ratings obtained from readers. Anticipating somewhat, we submit that the answer is encouraging. The empirical studies using this operational approach show that suspense can be predicted remarkably well in such a theoretical framework. Thus, a narrow notion of information structure appears to suffice for at least a broad understanding of how texts bring about narrative suspense.

However, one may ask whether this makes suspense a purely formal, abstract information structural property of texts, thus contradicting traditional theories that derive suspense from content-related features of narratives. Here, a more nuanced answer is called for. While the theory that we work with in this paper and that we describe in more detail in the next section is essentially based on erotetic structure alone, it is not void of content-related features and, thus, does not contradict content-oriented theories of suspense. While we argue for an erotetic approach to suspense, we are not arguing for a divorce between content and information structure but rather for an integrative view of information structure in which content receives its due role as a partial determinant of information structure, as usually witnessed in theories of grammar. To give an analogy, the notion of a sentential subject is often defined by purely formal properties such as nominative case or agreement with the verb for a specific language. But content-related features such as prototypical semantic roles, animacy or discourse-oriented features such as definiteness or anaphoricity clearly play a role in the selection and identification of the subject cross-linguistically (Keenan, Reference Keenan and Li1976). Returning to suspense, then, we argue that suspense may indeed come about as a structural property of text interpretation, but the structural properties of text interpretation are not derived independently of the very content of the text.

2. Background and hypotheses

2.1. Erotetic structure

Discourse and text are more than a random collection of linguistic utterances with related content. It is widely accepted that discourse has a hierarchical structure by which individual utterances are organized into larger units according to general rules and constraints. Two main formal pragmatic approaches aim to define these rules and constraints: rhetorical-relations-based approaches (Asher & Lascarides, Reference Asher and Lascarides2003; Mann & Thompson, Reference Mann and Thompson1988) and question-based, erotetic approaches (Ginzburg, Reference Ginzburg1992; Klein & Stutterheim, Reference Klein and von Stutterheim1991; Roberts, Reference Roberts2012a, Reference Roberts2012b; Wiśniewski, Reference Wiśniewski1995). In this text, we focus on erotetic theories. As already mentioned above, the core idea of erotetic theories is that information structure is captured by a hierarchy of questions that reflect the discourse goals of discourse participants.

In what follows, we briefly explain in what sense the erotetic theory of discourse can be understood as a broad theory of information structure in discourse. Consider a simple assertion such as (1).

Depending on what question the speaker has in mind, (1) can exhibit very different information structure. If the question in (2) is addressed, the topic and focus are clearly different from the situation in which question (3) is addressed. This is well reflected at the surface by the different intonation of the most natural answer to (2) and (3), respectively (see Onea & Zimmermann, Reference Onea, Zimmermann, von Heusinger, Zimmermann and Onea2019). Notice that in both cases the content is the same, but by having different questions as discourse goals, the information structure has changed. We call the question directly addressed by an utterance (or a larger segment of discourse) the QUD. The immediate QUD is focus-congruent to its answer. So, the immediate QUD captures the information structure of its immediate answers. Arguably, at such a low level, information structure as reflected by the immediate QUD is hardly relevant for macro-phenomena of text interpretation such as narrative suspense. However, if we assume that questions are discourse goals and that discourse is coherent human action, we need to assume that discourse goals are connected in a strategic way (Onea, Reference Onea2016; Roberts, Reference Roberts2012a, Reference Roberts2012b), leading to a hierarchy of QUD. Thus, we would assume that a question such as (3) is a discourse goal (QUD) because there is a higher question such that (3) contributes to answering it. For example, let us consider a question such as (4), a higher QUD. This question would be reasonable to ask because of an even larger discourse goal such as (5). This would then create a coherent strategy such as in (6), where the questions enclosed within <> are possible further developments of the text:

Establishing discourse coherence, then, essentially means (in such an approach) reconstructing a hierarchy of questions such as, but obviously much more complicated than, (6).

From a cognitive perspective, this aligns well with the idea that when reading a text, readers are faced with the task to reconstruct the discourse goals the text is pursuing. This idea is clearly dominant in Roberts (Reference Roberts2012a [1996]) but also present in various psychological models of text comprehension such as Graesser et al. (Reference Graesser, Singer and Trabasso1994). Thereby, readers may have prior top-down expectations, but they may also pursue a bottom-up approach: based on the way in which they understand the text, they try to establish a hierarchy of discourse goals that explains why the text is written the way it is. It is immaterial to our current tasks whether readers are usually able to achieve such a complete explanatory interpretation of a text at a conscious level or whether this can be fully achieved at all in each case, as discourse often underspecifies its erotetic structure. Moreover, one needs to distinguish between incremental processing of text and post-hoc reconstruction of the erotetic structure of texts. Even the latter is a challenging task (cf. Riester et al., Reference Riester, Brunetti, de Kuthy, Adamou, Haude and Vanhove2018, on erotetic structure annotation of texts).

For our purposes, the goal of achieving a complete erotetic analysis of a narrative text that is formally precise, reflects the linguistic information structure of the text and has sufficient cognitive plausibility is immaterial. If the overall direction of erotetic theories is correct, it should suffice that, readers try to reconstruct erotetic strategies in the reading process by (temporarily or permanently) assuming immediate discourse goals and higher discourse goals that the text might be pursuing. Thereby, immediate discourse goals are understood as implicit, covert questions under discussion immediately answered by various discourse segments (after all, human interaction in general rarely involves explicitly declared goals). We call such questions micro-questions. Higher discourse goals are questions to which the reader may anticipate getting an answer as the reading progresses. We call such questions macro-questions (see also Carroll, Reference Carroll1996).

It is generally assumed that there are two major types of moves within erotetic strategies connecting higher (macro-questions) and immediate discourse goals (micro-questions): so-called sub-questions, i.e., inquiring parts of the information needed to answer the super-question (Groenendijk & Stokhof, Reference Groenendijk and Stokhof1984; Roberts, Reference Roberts2012a) and non-strategic, opportunistic elements, such as ‘potential questions’, i.e., questions made salient by given information (Onea, Reference Onea2016). Questions (2) and (3) would be sub-questions of question (4), for example. A potential question licensed by (1) would be (7), i.e., a question that one could not have naturally asked in discourse unless after having found out about the information given in (1).

In an ideal post-hoc analysis of a text, macro- and micro-questions are perfectly connected by potential questions and sub-questions following a well-defined set of rules. Moreover, in a processing theory of text interpretation, we should expect a range of temporary assumptions and restructuring operations on segments of hierarchical structure. But even without providing a full erotetic analysis of any given text, there is a clear prediction that in the reading process, readers will be preoccupied with, or entertain, questions that are at least temporarily assumed to be parts of the erotetic structure of the text. Indeed, a text that would eventually end up ignoring such questions is likely quite frustrating to read. So, the crucial element from erotetic theories of discourse that we will need is only the assumption that readers are able to identify questions addressed or raised by the text at various points.

Before closing this section, let us be reminded, however, that at the level of both immediate and higher discourse goals, not only linguistic form (word order, morphosyntax, prosodic features, etc.) but also content (from basic features such as animacy up to broad probabilistic expectations about what is normal or likely in a situation) play a role (Onea, Reference Onea2016). To give a very basic example, one is much more likely to ask (7) in continuation of the sentence provided in (1) because it is content-wise an unusual activity for hunters to chase cats in a backyard; but an analogous question given in (8b) would be a much less likely element of the erotetic structure of a text starting with (8a) because dogs often do chase cats, a fact that does not usually require an explanation.

2.2. Potentially inquiry-terminating questions and narrative suspense

With this general background, we now move to the role of the erotetic structure in the explication of narrative suspense. The core idea of Köppe and Onea (Reference Köppe and Onea2023) is that one substantial way in which readers anticipate the erotetic structure of a narrative is by implicitly asking macro-questions about possible future events in the story; i.e., when readers find sufficient grounds to assume that the text will discuss and answer a question about a possible future plot event, their online interpretation will assign it QUD status: readers will assume that the text is going to employ a rational strategy to answer it. They then try to interpret the subsequent text as an erotetic strategy to answer the macro-question about a future plot event. While a reader might be mistaken about his/her online interpretation of the text and the text might not always answer the question the reader might expect, crucially, for Köppe and Onea (Reference Köppe and Onea2023) suspense is associated with a given online interpretation and not with ex post structural text analysis. Hence, if a reader assumes that a question will be addressed by the subsequent text, this will be good enough to trigger suspense under certain conditions.

But what are these conditions? To see this, we need one more crucial term: potentially inquiry-terminating questions (PITQs), as defined in (Def I).

(Def I) A question q is a PITQ of another question q’ iff there is at least one possible answer to q that entails an answer to q’ and at least one possible answer to q that leaves q’ open.

We start with a simple non-narrative example to clarify the intuition behind this. Take a super-question of the form: ‘Who ate how many cookies?’ This question can be strategically addressed by sub-questions of the form: ‘How many cookies did Xi eat?’ where Xi is the i-th person in a sequence. Now, suppose there are eight cookies and five people, i.e., five sub-questions. Even for the first sub-question, one possible answer, namely that X1 ate eight cookies, would lead to the immediate termination of the inquiry, while any other number would not, thereby making each of the sub-questions PITQs in turn. By contrast, a similar series of sub-questions would not contain any PITQ if we did not know the number of cookies.

Now suppose that the super-question is a binary question about an important future plot event. According to Köppe and Onea (Reference Köppe and Onea2023), if a reader has established a macro-question about an important future plot event as a QUD for the subsequent text, then encountering a PITQ makes him/her vividly experience that the macro-question is about to be answered. Consider a scenario in which a character needs to reach a certain destination like an airport in time, but she is slightly late. The established QUD here is whether she will be able to reach her goal. As she is on her way to the destination, she ends up in a traffic jam and her driver explains that the only way to get there on time is to drive on the safety lane, but this will only work if the police do not catch her. Now the question of whether the police will catch her is a PITQ with regard to the broader QUD, since, if the police were to catch her, by the rules established, she would no longer make it to her destination. Thus, when asking whether the police will show up, the reader implicitly also asks whether she will make it on time to her destination. The very expectation to be on the tip of acquiring a favorable goal (i.e., receiving the information needed to answer the macro-question) triggers the excitement that is characteristic of experiences of suspense. Köppe and Onea (Reference Köppe and Onea2023) assume that encountering a PITQ without getting an answer to the governing macro-question constitutes a situation of ‘near-miss’ – a known source of excitement when experiencing the imminence of reaching, or almost having reached, a goal (Pisklak et al., Reference Pisklak, Yong and Spetch2020).Footnote 1 Repeated exposure to PITQs (which occurs mainly when the answer to a PITQ is given such that the macro-question remains open) intensifies this excitement. We assume that the effect of outcome delay on suspense (Doicaru, Reference Doicaru2016) is directly related to this: allowing many PITQs necessitates a slow revealing of the outcome.

In a nutshell, then, Köppe and Onea (Reference Köppe and Onea2023) reduce suspense to one single textual feature based on information structure, namely the appearance or accumulation of PITQs.

2.3. Operationalization

Given the empirical focus of this paper, the theory leads to our main hypothesis:

Hypothesis I: In a narrative, the posing and answering of PITQs in the reading process is positively correlated to suspense.

In order to operationalize this hypothesis, we will need to introduce a slight modification to the term ‘PITQ’, however. Def I is a purely logical definition, and as such, it may be too strong for the analysis of narratives (Bruner, Reference Bruner1991). Therefore, we replace the term ‘entailment’ in (Def I) with ‘n-entailment’, which in turn is defined as follows (see Def II).

(Def II) A proposition p n-entails a proposition p’ at a point t in a narrative for a reader R iff it is narratively plausible for R at t that if p holds in the narrative, p’ also holds true in the narrative.

N-entailment is independent of de facto narrative outcome, but rather relative to the reader’s personal knowledge base, expectations and psychological profile in the context of the narrative interpretation. It may thus vary between readers. We now adapt the definition of PITQs by integrating the notion of n-entailment and by specifying practical constraints on the run-time of questions that may stand in the PITQ relations matching the progression of readers’ knowledge through the story. Hence, in (Def III), we give a refined definition of PITQs that fits narratives and is sufficiently operational for text annotation:

(Def III) A question q is a PITQ of another question q’ in a narrative iff: (i) q is raised and answered within the text segment in which q’ is open; (ii) there is at least one possible answer to q that ‘n-entails’ one answer to q’ and at least one possible answer to q that leaves q’ open.

For example, ‘Will the lion catch the gazelle?’ might have the PITQ ‘Will the lion stumble?’, because stumbling ‘n-entails’ the lion failing, while not stumbling cannot ensure the lion’s success. Note that stumbling does not entail (but rather only ‘n-entails’) the lion’s failure, and indeed, one can imagine that the lion actually stumbles and still manages to catch the gazelle – but this does not change the PITQ status of the question because the reader would usually assume while asking the question that stumbling would lead to failure. After all, one may hold one’s breath (if rooting for the lion) and wish that the lion does not stumble.

The next step in the operationalization is to provide a comprehensive numeric link between suspense and PITQs. Specifically, we introduce what we call an ‘activation’ index, a numerical predictor based on the erotetic structure of a narrative (see Def IV).

(Def IV)

Activation index

![]() $ ac{t}_i=\left( ac{t}_{i-1}+p\right)\times {e}^{-\lambda d.} $

$ ac{t}_i=\left( ac{t}_{i-1}+p\right)\times {e}^{-\lambda d.} $

The general idea of the equation is this: activation increases whenever a new PITQ is raised or answered, and activation naturally decays over time. We model this in a recursive way assuming that

![]() $ ac{t}_0=0 $

, i.e., the text starts out with an activation index of 0. Then, for any text unit

$ ac{t}_0=0 $

, i.e., the text starts out with an activation index of 0. Then, for any text unit

![]() $ i $

, the activation is increased by

$ i $

, the activation is increased by

![]() $ p $

.

$ p $

.

![]() $ p $

is a binary that equals 0 if in text unit

$ p $

is a binary that equals 0 if in text unit

![]() $ i $

in the narrative, no new PITQ of any open question has been raised or answered and 1 otherwise. Moreover, the activation is multiplied by a term that captures decay over time. This term involves two variables,

$ i $

in the narrative, no new PITQ of any open question has been raised or answered and 1 otherwise. Moreover, the activation is multiplied by a term that captures decay over time. This term involves two variables,

![]() $ \lambda $

and

$ \lambda $

and

![]() $ d $

.

$ d $

.

![]() $ d $

is the distance to the last raise in activation, i.e., the last time ‘something relevant to suspense happened’, i.e., the reader established that either a PITQ emerged, thus giving a vivid possibility for a macro-question to be answered.

$ d $

is the distance to the last raise in activation, i.e., the last time ‘something relevant to suspense happened’, i.e., the reader established that either a PITQ emerged, thus giving a vivid possibility for a macro-question to be answered.

![]() $ \lambda $

, by contrast, is a free model parameter symbolizing the acceleration of activation decay which we take to be exponential over time. It is a measure of how quickly suspense decreases when nothing happens. The parameter

$ \lambda $

, by contrast, is a free model parameter symbolizing the acceleration of activation decay which we take to be exponential over time. It is a measure of how quickly suspense decreases when nothing happens. The parameter

![]() $ \lambda $

allows for the equation to apply independently of the granularity of text units with which the distance

$ \lambda $

allows for the equation to apply independently of the granularity of text units with which the distance

![]() $ d $

is measured, e.g., words, lines, paragraphs, pages, etc. Such a parameter is necessary, as we cannot possibly assume that a distance of ten words would have the same impact on the decay of activation as ten paragraphs. Similarly, we may assume that

$ d $

is measured, e.g., words, lines, paragraphs, pages, etc. Such a parameter is necessary, as we cannot possibly assume that a distance of ten words would have the same impact on the decay of activation as ten paragraphs. Similarly, we may assume that

![]() $ \lambda $

may also vary depending on genre and style. For example, a novel which is full of long descriptions may have a very different

$ \lambda $

may also vary depending on genre and style. For example, a novel which is full of long descriptions may have a very different

![]() $ \lambda $

as compared to a short story in which we can expect the plot to reach closure within only a few pages.

$ \lambda $

as compared to a short story in which we can expect the plot to reach closure within only a few pages.

Clearly, more elaborate versions of the equations are possible and may lead to more accurate predictions, for example by counting the number of raised or answered PITQs at a certain line of text, by including weights according to their hierarchical structure, etc. However, for the purposes of this paper, a minimal model is preferable as a baseline for further research on suspense prediction.

Finally, we suggest that the term ‘PITQ’ seems to gloss over a potentially crucial distinction. Let us return to our lion–gazelle chase scenario. Whether a lion might stumble may be of interest to the reader for at least the following two reasons: a) because the reader is interested in the outcome of the chase and deems the possibility of stumbling on the difficult terrain as relevant for the outcome or b) because the reader finds stumbling events interesting or important for themselves. Imagine, for example, that the reader assumes (or it is implied by the story) that a lion tends to fracture a bone when stumbling and thus stumbling would mean a short-term death sentence for the lion. In scenario a), the reader may root for the lion saying: ‘Don’t stumble, otherwise you miss the gazelle!’; in scenario b), the reader may root for the lion saying: ‘Oh, just don’t stumble on that difficult terrain! The gazelle is not worth risking your life!’ In both cases, the question about stumbling logically qualifies as a PITQ of the macro-question ‘Will the lion catch the gazelle?’; but it is only in the first case that the reader asks the PITQ because he/she is interested in the macro-question. Thus, we may want to distinguish between types of PITQs based on why they are raised. To capture this intuition, we distinguish between plain PITQ and PITQ+, such that a question q is a PITQ+ of q’ if q is a PITQ of q’ and q’ is the main reason why q is asked. By contrast, a plain PITQ could be asked for independent reasons. Imagine, as a second example, a narrative that entertains q’: ‘Will the protagonist be able to pay off his debt?’ Further on, the protagonist encounters a life-threatening situation, which raises q: ‘Will the protagonist survive?’ While q uncontroversially is a PITQ of q’, as paying off one’s debt is pointless when dead, q is not a PITQ+ of q’, as a reader will not ask q to get an answer to q’, but rather out of a more general interest in the protagonist’s welfare that is not motivated by the plot which is governed by q’ specifically.

Distinguishing between PITQ+ and plain PITQ raises the question of which one is more suitable for capturing narrative suspense. PITQ+ being defined as a reader wanting the answer to the macro-question that is the precondition to a near-miss situation, we pose Hypothesis II.

Hypothesis II: PITQ+ is better suited to predict suspense than the basic notion of PITQ.

Thus, we suggest that we can have an activation+ index, in which the role of PITQ is simply replaced by PITQ+. Then, Hypothesis II essentially says that activation+ is better correlated with suspense.

3. Study 1

3.1. Method

This study used the text ‘The Brazilian Cat’ by Arthur Conan Doyle, translated into German (Doyle, Reference Doyle1970), to which we shall refer as Text 1 in what follows. The study comprised two stages, a) the measurement of the suspense arc of the text and b) an expert annotation of PITQs for the text, in order to be able to check Hypotheses I and II.

Since Bentz et al. (Reference Bentz, Cortez Espinoza, Simeonova, Köppe and Onea2024) have not only proposed a novel paradigm of measuring suspense at the behavioral level at a very high level of granularity but also measured the suspense of Text 1, we have used their measurement data for our purposes. The data, which are available on OSF at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/YJ2Z7, comprise suspense ratings by 34 participants (aged M = 27.5, SD = 8.8), speakers of German at the University of Göttingen, and provide word-level suspense ratings. The methodology, which was also employed for new data collection in Study 2, involves participants reading a text while simultaneously drawing a continuous line in a coordinate system to represent the intensity of felt suspense. This process yields fine-grained, word-level suspense ratings. A key advantage of this continuous drawing method over traditional discrete rating tasks (e.g., stopping to rate on a Likert scale every few sentences) is that it minimizes disruption to the reading process. This allows for a more natural immersive experience and captures the dynamic, fine-grained rise and fall of suspense in real time. (For a full description, see Section 4.1.)

We conducted our annotation in a two-step procedure. In the first step, three groups consisting of two students, each trained in narratology, annotated questions that emerged during their reading experience. The tasks were to formulate binary, future plot-related questions q’ and to determine the points at which each question emerged and was answered. In the second step, two experts in formal semantics and pragmatics (co-authors of this paper) eliminated all questions that did not meet these criteria, e.g., because they targeted past events or explanations rather than the plot. Similarly, the experts merged questions that differed only in their wording, such as ‘Will he fail to P?’ vs. ‘Will he succeed to P?’, and resolved unclarities concerning the way question spans were determined (when exactly a question is raised in the narrative and when it is answered). This way, a total number of 99 questions were determined. Two student assistants trained in theoretical linguistics and formal pragmatics then used Excel spreadsheets to create two matrices containing information on PITQ and PITQ+ relations for all combinations of two questions.

3.2. Results

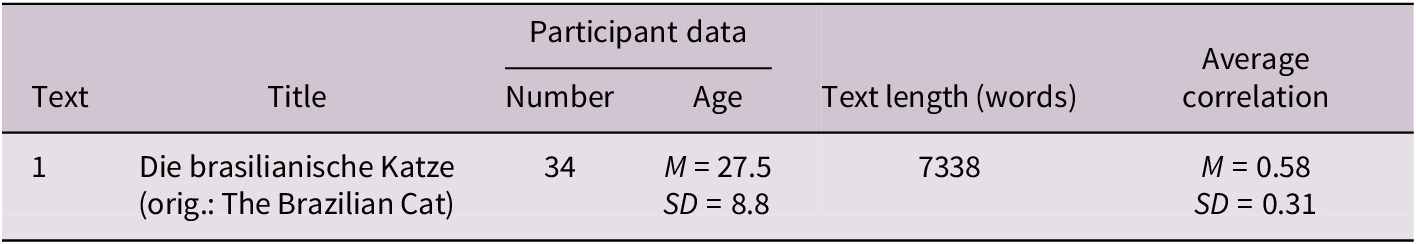

Data analysis was performed using R 4.4.1 (R Core Team, 2024) and RStudio (Posit team, 2024). As recommended by Bentz et al. (Reference Bentz, Cortez Espinoza, Simeonova, Köppe and Onea2024), we z-transformed the measured suspense data participant-wise to eliminate participant-specific height variation, thereby revealing the suspense arc of the story as given by each participant. Table 1 summarizes key measurement data, including the average correlation between readers’ suspense ratings.

Table 1. Core data about the suspense measurement for Text 1

Inter-annotator agreement between the two student assistants, A and B, who have annotated the PITQ and PITQ+ relations can be considered excellent (PITQ: Cohen’s

![]() $ \kappa $

= 0.95, z = 90.1, p < 0.001; PITQ+:

$ \kappa $

= 0.95, z = 90.1, p < 0.001; PITQ+:

![]() $ \kappa $

= 0.943, z = 99.8, p < 0.001). The numeric value of the model parameter

$ \kappa $

= 0.943, z = 99.8, p < 0.001). The numeric value of the model parameter

![]() $ \lambda $

,

$ \lambda $

,

![]() $ 4.2\times {10}^{-5} $

, which we use to compute all activation scores in all texts reported in this paper, was determined by maximizing

$ 4.2\times {10}^{-5} $

, which we use to compute all activation scores in all texts reported in this paper, was determined by maximizing

![]() $ {R}^2 $

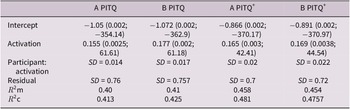

values of linear models predicting z-suspense from activation, using annotation data. From the matrices, activation was computed for each line of the text for both PITQ and PITQ+ independently. Using the lme4 package (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015), we fitted more complex linear mixed effects models with the maximum likelihood method (REML). We did this separately for all annotations: A and B for PITQ and PITQ+, respectively. To predict z-suspense from activation, we included participant-wise random slopes for the effect of activation, but including participant-wise random intercepts led to singular models, as our methodologically motivated z-transformation eliminated most inter-participant height variation (model specification: z_suspense ~ activation + (0 + activation|participant)). We report here the best model, i.e., the case of activation+, from PITQ+, computed given the annotation of annotation Team A, but in Table 2, we summarize all four models. Activation was found to have a significant fixed effect (

$ {R}^2 $

values of linear models predicting z-suspense from activation, using annotation data. From the matrices, activation was computed for each line of the text for both PITQ and PITQ+ independently. Using the lme4 package (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015), we fitted more complex linear mixed effects models with the maximum likelihood method (REML). We did this separately for all annotations: A and B for PITQ and PITQ+, respectively. To predict z-suspense from activation, we included participant-wise random slopes for the effect of activation, but including participant-wise random intercepts led to singular models, as our methodologically motivated z-transformation eliminated most inter-participant height variation (model specification: z_suspense ~ activation + (0 + activation|participant)). We report here the best model, i.e., the case of activation+, from PITQ+, computed given the annotation of annotation Team A, but in Table 2, we summarize all four models. Activation was found to have a significant fixed effect (

![]() $ {\chi}^2(1) $

= 1798.3, p < 0.001) in the type II Wald chi-squared test. The random effects indicated variability in activation across participants, with a variance of

$ {\chi}^2(1) $

= 1798.3, p < 0.001) in the type II Wald chi-squared test. The random effects indicated variability in activation across participants, with a variance of

![]() $ 5.2\times {10}^{-4} $

and a standard deviation of

$ 5.2\times {10}^{-4} $

and a standard deviation of

![]() $ 2\times {10}^{-2} $

. The residual variance was 0.519 with a standard deviation of 0.720. A marginal R-squared (

$ 2\times {10}^{-2} $

. The residual variance was 0.519 with a standard deviation of 0.720. A marginal R-squared (

![]() $ {R}^2 $

m) of 0.459 and a conditional R-squared (

$ {R}^2 $

m) of 0.459 and a conditional R-squared (

![]() $ {R}^2 $

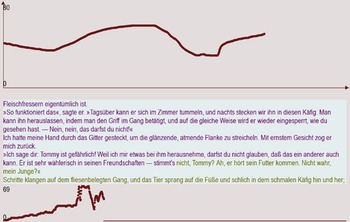

c) of 0.481 suggest a strong model fit that captures a substantial proportion of the variance in z-suspense with only a minimal role played by participant-related variation. The simplicity of the model leaves no concern of overfitting. Figure 1 shows the actual and model-fitted suspense lines in an original and a smoothed version. For smoothing, we applied a generalized additive model (GAM), using the geom_smooth function from the ggplot2 package (Wickham, Reference Wickham2016) with a smoothing spline (s (x, k = 40)).

$ {R}^2 $

c) of 0.481 suggest a strong model fit that captures a substantial proportion of the variance in z-suspense with only a minimal role played by participant-related variation. The simplicity of the model leaves no concern of overfitting. Figure 1 shows the actual and model-fitted suspense lines in an original and a smoothed version. For smoothing, we applied a generalized additive model (GAM), using the geom_smooth function from the ggplot2 package (Wickham, Reference Wickham2016) with a smoothing spline (s (x, k = 40)).

Table 2. Results of linear mixed effect models for Text 1, SE (standard error) and t-value in parentheses

Figure 1. Predicted and measured suspense arcs for Text 1.

Finally, we compared the linear mixed effect models using the activation computed from PITQ+ with the analogous model with activation from PITQ using the AIC and BIC values for the two teams individually. The results showed that the model based on the PITQ+ annotation was superior both in terms of AIC (df = 4, PITQ+ 544498.0 < PITQ 574975.4) and in terms of BIC (PITQ+ 544539.7 < PITQ 575017.1) for Team A. Similarly, for the comparison for Team B, we found better AIC (PITQ+ 547193.0 < PITQ 569857.2) and BIC (PITQ+ 547234.7 < PITQ 569898.9) values for the PITQ+ model.

3.3. Discussion

The study shows first and foremost that annotation of PITQs was successful and that the overall height of the suspense arc is well predicted. As shown in Figure 1, suspenseful and non-suspenseful regions are distinctively captured, and most measured suspense peaks are correctly predicted. The right-hand side graph shows GAM-smoothed lines, which reveal excellent alignment between the fitted and actual values. Taking into account the fact that we disregarded all other potentially relevant factors (such as narratological categories, question importance, etc.), the resulting simplicity of our model, the complexity of the phenomenon, the length of the text and the novelty of the approach, we consider the model fit excellent and take our results as strong evidence for Hypothesis I.

Regarding Hypothesis II, the results of model comparison reported above are in line with the hypothesis, as for both teams the PITQ+ models outperformed the PITQ models. However, as the annotation was aided by expert annotators (co-authors of this paper), replicating the results with non-expert, unbiased annotators was crucial in order to avoid potential bias stemming from expert knowledge. Exploring generalizability to other texts was another motivation. These concerns are addressed in Study 2.

4. Study 2

4.1. Method

For Study 2, we used the same method of suspense measurement as reported in Bentz et al. (Reference Bentz, Cortez Espinoza, Simeonova, Köppe and Onea2024), including the software provided to collect suspense measurement data for additional texts. However, we corrected a minimal software error reported in Bentz et al. (Reference Bentz, Cortez Espinoza, Simeonova, Köppe and Onea2024) that led to the loss of ratings for the very last segment of text, showed on the last screen. While the method of suspense measurement is identical to the one used in Study 1, we only explain the method here, since for Study 1 we used already published data and did not actually employ the method ourselves. Given the detailed description of the method in Bentz et al. (Reference Bentz, Cortez Espinoza, Simeonova, Köppe and Onea2024), we limit ourselves to a short description here.

A group of participants (32 participants, aged M = 24.0, SD = 3.2) rated the stories ‘Thomas’ (Krypczyk, Reference Krypczyk and Fitzek2020) and ‘Ein geheimer Auftrag’ (English translation as ‘A Secret Mission’ (Koeppen, Reference Koeppen and Estermann2000); these two shorter texts were rated back to back in one session, for which participants were remunerated with 12€ per hour at the University of Göttingen. The order in which the texts were rated was assigned randomly. The third text, a German translation of ‘how it happened’ (Doyle, Reference Doyle, Rocholl and Erné1969) (17 participants, aged M = 27.0, SD = 12.5), was rated in the process of a university wide ‘open science’ event at the University of Göttingen, thus explaining the age and participant number deviations as compared to the other texts.

Timeline: after an introductory phase featuring a questionnaire about personal data (age, highest degree of education, reading habits, etc.), participants were acquainted with the software environment in a training phase (zooming in and out on the drawing field, navigating back and forth between text sections, making corrections to a drawn line). In the main phase, participants read and simultaneously rated the text for their felt suspense through drawing a line on the screen corresponding to the experienced suspense intensity at the respective location in the text. Participants were given the following instructions: ‘Zeichne bitte mit der Linie ein, wie spannend du es findest [Please draw the line according to the suspense you experience.]’. During the training phase, two additional sentences had already been phrased as: ‘Sollte es weniger spannend werden, zeichne die Linie nach unten [in the case that the story becomes less suspenseful, draw the line downward]’ and ‘Deine Linie bildet also die Spannungsentwicklung im Textabschnitt ab [Your line thus represents the development of the suspense in the text part.]’.

The experiment software: the software provided a visual paradigm including (I.) a coordinate system to draw suspense ratings, (II.) a text box displaying a text section of ten lines and (III.) a progress bar box at the bottom of the screen. To facilitate orientation within the text when drawing, rated text appears in a different color than unrated text. The lower margin in the coordinate system is always at zero-level suspense, but the higher margin is adaptable, ensuring that rating at any suspense level is possible (‘the zooming option’). The progress bar at the bottom indicates the drawn line so far, the progress through the entire text and the maximum value rated so far. It is updated upon moving on to the next text section (see Figure 2). Cursor movement is constrained to rightward movement, and progressing to the next text section requires reaching the right edge of the drawing field (i.e., completing the rating for the current section). The suspense line data are saved at pixel-level granularity and mapped onto respective words in the text. For the data analysis of this experiment, these finer-grained data were aggregated to get one suspense value per word.

Figure 2. Visual paradigm of suspense measurement software.

As the participant draws the line from left to right, the text in the box above changes color in sync with the horizontal progress of the cursor. This provides continuous visual feedback, mapping the drawn suspense rating directly onto the segment of the text being rated. While individual strategies may vary – some may read and draw simultaneously, while others may read the full screen and then draw – the software ensures a direct spatial correspondence between the drawn line and the text on each screen.

All text annotation steps were done by two teams of two students each, Team A and Team B, who were given basic training in the erotetic structure of texts and the terminology necessary for annotation. First, each team annotated emerging questions, together with their opening and closing points, i.e., the point where the question is raised and where the question is answered. Both resulting lists were then annotated for PITQ and PITQ+ by both teams, yielding four sets of annotation data (two sets of agreement data) per text and PITQ type. Analogous to Study 1, a ‘PITQ-matrix’ and a ‘PITQ+-matrix’ were created.

4.2. Results

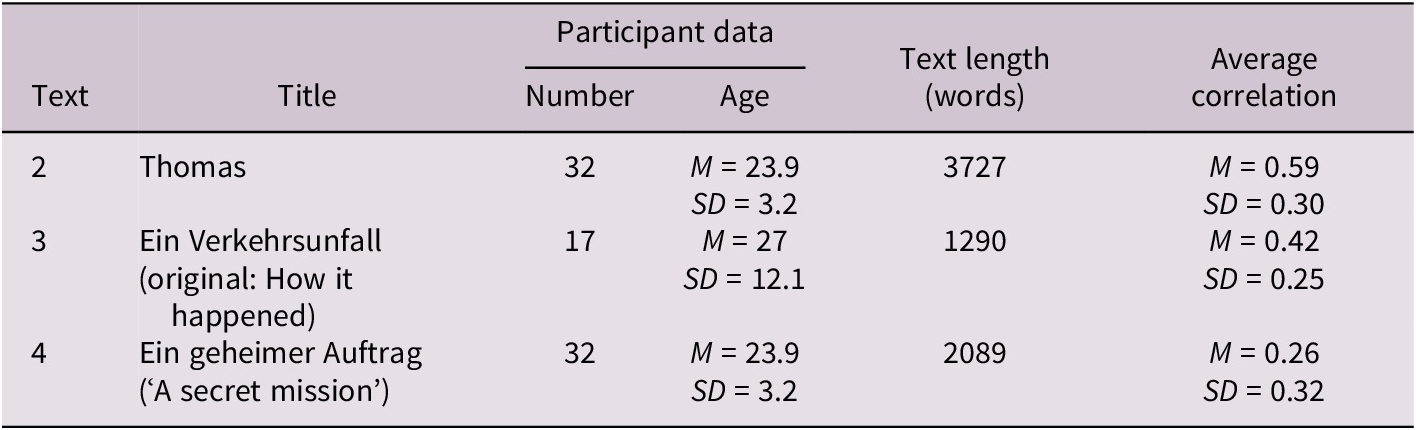

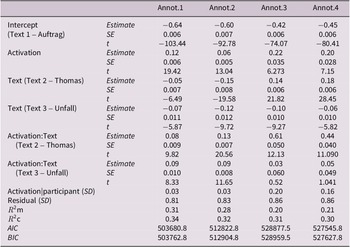

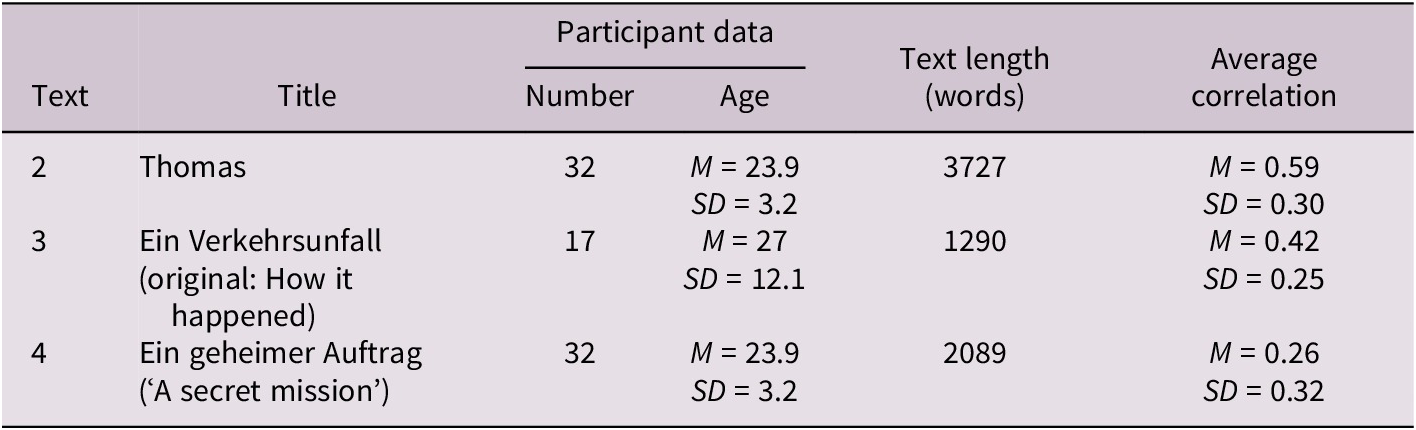

Again, we z-transformed the measured suspense data participant-wise to eliminate participant-specific height variation, thereby revealing the suspense arc of the story as given by each participant. Table 3 summarizes key measurement data, including the average correlation between readers’ suspense ratings. Other personal demographic data, especially regarding sex and gender, were not collected.

Table 3. Core data about the suspense measurement for Text 2–4

In Table 4, Cohen’s kappa gives the inter-annotator agreement between the teams. In all cases, Team A annotated far more questions than Team B. The teams achieved mostly moderate agreement, except for a good and a perfect agreement on PITQ for Texts 2 and 3 with the list created by Team B and only a fair agreement on PITQ+ for Text 2 (Team B) and for Text 3 (Team A).

Table 4. Inter-annotator agreement – student annotation

We have used the previously established λ = 4.2 × 10−5 to compute activation for all texts based on all annotations. Notice that since the annotating team configurations were the same for all three texts, we were able to fit a single linear mixed model for each annotation (corresponding to a team configuration) with main effects for ‘activation’ and ‘narrative’ (i.e., the individual texts), an interaction term between the two as well as participant-wise random slopes for activation (z-suspense ~ activation × narrative + (0 + activation|participant)), with participant-wise random intercepts being excluded for the same reason as in Study 1. The model output for all eight models can be found in Table 5 (PITQ+) and Table 6 (PITQ). Activation was highly significant with p < 0.001 for all of the models.

Table 5. Results of linear mixed effects models for Study 2 for each annotation team with PITQ+

Table 6. Results of linear mixed effects models for Study 2 for each annotation team with PITQ

Figure 3 shows the predicted suspense arcs for each text in comparison to the measured arcs based on the output of the best model in terms of AIC and BIC comparison.

Figure 3. Fitted versus measured suspense for Study 2.

4.3. Discussion

Our first observation is about the measured suspense. While we found fair correlation between the suspense measurements by participants in general, it was less so the case for Text 4, also exhibiting a broader ribbon for the z-suspense, indicating high variation. Apparently, the suspense arc of this text was not clearly identifiable for participants. In addition, toward the end of Text 3, the graph shows a measured suspense peak with a high variation: the last suspense peak was simply not identified by all participants. Upon inspection of the respective text section, it becomes apparent that this peak is not an instance of plot-related narrative suspense. Specifically, at this point, the protagonist of the story realizes that the person he is interacting with is in fact dead. One might call the phenomenon ‘mystery’ in the sense of Carroll (Reference Carroll1996) – a related kind of arousal where curiosity is directed toward a significant past event that explains the current situation. Critically, the mystery question is usually an open question about the plot such as ‘Why?’, ‘How come?’, ‘How was it possible?’, etc. Thus, while mystery is related to suspense in the sense that both raise questions about the plot, they differ in terms of the direction of the questions (future for suspense, past for mystery) and the nature of the question (binary for suspense and open for mystery). For this reason, it is clear that our model could not have predicted mystery even in principle.

However, the German term Spannung does not distinguish sufficiently between these notions (Junkerjürgen, Reference Junkerjürgen2002, 61, see also Hirsch et al., Reference Hirsch, Köppe and Onea2025 – for an analysis of the meaning range of the term Spannung in German); thus, the measurement experiment was not sensitive to this distinction, due to a lexical ambiguity in German. Since mystery did not occur in other parts of the analyzed stories, it did not cause any other issues with the data. Even in this particular peak, apparently some participants with a stricter notion of ‘suspense’ might have ignored the ‘mystery’ peak, thereby causing the observed noise.

The second observation is that annotating plot questions comes with challenges, as witnessed by the vastly different numbers of annotated questions between annotators. While these challenges may be overcome partially with more training and better guidelines, a certain level of variation may be unavoidable due to the subjective nature of various aspects of the annotation. For instance, the reason for posing a PITQ, the points at which a question is considered raised and answered and the PITQ relation itself depend not only on textual parameters but also on epistemic factors subject to inter-individual variation. For a more detailed discussion of variation in literary annotations, see Gius and Jacke (Reference Gius and Jacke2017). In conclusion, while expert annotations show better results, the fact that the computed activation index was a highly significant predictor for suspense in all models provides still more evidence for the aptness of the theory.

Observing the graphical representation in more detail, the model fit for Text 2 appears quite good: it captures the suspense arc correctly for large parts of the narrative, with only minor rises missing. Missing rises suggest that some relevant plot questions were not annotated. One particularly striking observation is that there is a decay-caused drop of predicted suspense at the end of the text, in the range of words 3200–3500. Apparently, readers experienced suspense as stable at a high level, while our model assumes a drop of suspense because no PITQs were identified by the annotators in this region. Potentially, a version of the theory that assumes different decay rates after opening and closing PITQs (where decay would need to be slower after opening a PITQ) would be able to handle such cases better. However, the goal of this paper is limited to a basic model of suspense based on activation, and we leave a more elaborate activation-based model for future research.

Lastly, Text 4 shows modest results, which is unsurprising given the high variation between participants’ suspense judgments found in the measurement study. Thus, we consider these modest results to constitute no evidence against Hypothesis I. We return to the problem in the next section.

What is more important, however, is that based on the model outputs, we can quite safely suggest that even the worst-performing annotation captures a significant amount of variation based on its R2 score. Indeed, the difference between the annotations is not particularly large in terms of their ability to predict suspense, which is a signal that the theory is on the right track and constitutes a good baseline for further elaboration.

Finally, the initial evidence toward Hypothesis II, concerning the superiority of the predictive power of the PITQ+ annotations, was not confirmed in Study 2. Indeed, it seems that PITQ+ annotations performed generally worse than simple PITQ annotations. However, given the general observation that non-expert annotations tend to fail to identify critical plot questions and thus tend to miss suspense-relevant plot events, the fact that PITQ+ imposes even harder constraints on the activation index appears to explain this finding independently. In other words, the data suggest that more relevant plot questions should have been annotated, and it is entirely possible that PITQ+ would have been superior if more questions had been annotated. For this reason, we do not consider Study 2 strongly conclusive regarding Hypothesis II, and we leave it open for future research to elucidate its correctness.

One could also entertain a different possible interpretation of the fact that non-expert plot question annotators tend to fail to identify critical plot questions. Specifically, one may interpret this as evidence against the importance of PITQ (and PITQ+) in literary narrative processing. While we readily acknowledge that this possibility exists, we take it that the difference between expert and non-expert annotators is more plausibly explained in terms of invested energy and cognitive load associated with the annotation process. An annotator may entertain a binary question during the reading process and yet fail to annotate it (correctly) for a multitude of reasons. Ideally, a future experiment in which an online assessment of future plot-related questions is implemented could elucidate this issue.

5. General discussion

The two studies presented in this paper provide clear evidence that the erotetic structure of a narrative is highly relevant for suspense and thus a text model based primarily on the linguistic understanding of information structure is indeed able to provide a respectable model of suspense. While an expert text analysis yields the best quality of predictions, annotations with limited inter-annotator agreement also yield highly significant effects of activation on suspense. This is an important result for several reasons.

First, the formula used to compute the activation index as well as the statistical model itself is remarkably simple, consisting of a single predictor. Crucially, we used the same value

![]() $ \lambda $

for all four texts, i.e., the only parameter of the model was not manipulated to increase model performance for each text individually. (Obviously, somewhat better R2 values could have been achieved with

$ \lambda $

for all four texts, i.e., the only parameter of the model was not manipulated to increase model performance for each text individually. (Obviously, somewhat better R2 values could have been achieved with

![]() $ \lambda $

optimized for each text and by modeling texts individually.) Moreover, the random effects observed in the mixed models only account for a minimal amount of variation; thus, in practice, the theory operationalized in the way suggested in this paper can be reduced to even simpler models. While future research can clearly improve the model, we deem simple approaches to complex and multifaceted phenomena such as narrative suspense all the more impressive.

$ \lambda $

optimized for each text and by modeling texts individually.) Moreover, the random effects observed in the mixed models only account for a minimal amount of variation; thus, in practice, the theory operationalized in the way suggested in this paper can be reduced to even simpler models. While future research can clearly improve the model, we deem simple approaches to complex and multifaceted phenomena such as narrative suspense all the more impressive.

Second, as our model derives suspense from high-level, interpretive textual properties, it comes with a genuine explanation for variations in experienced suspense: the text underspecifies its erotetic interpretation, and the interpretation underspecifies the cognitive-emotional response. However, just as we believe that a theory of text interpretation – albeit not necessarily incorporating stochastic parameters – can be given, our results suggest that a theory of cognitive-emotional responses mediated through text interpretation is possible as well. The key element is the representation of text interpretation as erotetic structures that reflect rational goals of linguistic behavior.

It might be argued that, prima facie, the experiments merely show that students can be trained to create plot questions based on linguistic elements in some regions of the text and that these plot questions play a role in the prediction of suspense. What is lacking is evidence that these questions are being generated online, during reading or – for that matter – that they partake in what would count as a preliminary or final (ex post) erotetic structure of the texts under investigation. We readily admit that future research is necessary to show that such questions would be activated in the reading process even if the annotators were not specifically trained and prompted to find such questions. However, (a) to the extent that these questions are actually generated online they do qualify as potential questions and thus are naturally part of the erotetic structure of the respective texts (at least at some preliminary level, as explained in Section 2.1) and (b) essentially all theories of suspense link suspense to curiosity, and explicating curiosity in terms of binary questions (following Carroll’s, Reference Carroll1996 theory, but also Zillmann, Reference Zillmann, Bryant and Zillmann1991 and many others) is indeed a very natural step. Hence, while we acknowledge that further studies will be necessary to validate our assumptions about the cognitive reality or plausibility of the annotated questions as part of the broadly understood information structure of the text, we maintain that the hypothesis is as solid as can be given the state of the research on the erotetic structure of texts in general and on the linguistic basis of aesthetic phenomena such as suspense in particular.

Third, Figure 3 shows how most predicted peaks correspond to a significant increase in measured suspense. However, there remain measured suspense peaks that the model failed to detect. This leads to two hypotheses:

Hypothesis III: The activation model is a sufficient but not necessary factor in the emergence of suspense.

Hypothesis IV: The level of detail to which plot events can be annotated is insufficient to capture all details of suspense arcs.

Given that we observed some variation in the number of questions annotated by different annotation teams for each text and even in the annotation of the PITQ and PITQ+ relation, we suggest that Hypothesis IV might be on the right track. However, even without further data to help distinguish between the two hypotheses, our model is able to isolate those suspense peaks that are not captured. This facilitates research on the components missed by the theory. Crucially, such research needs to focus qualitatively and quantitatively on the specific sort of variation not captured by our models.

There is also a broader question about the scope of erotetic theories of suspense. While we have specifically tried to capture suspense from a linguistic perspective in this paper, suspense does not only come about while reading narratives. We contend that wherever a consumer processes information sequentially and forms expectations, they are effectively raising PITQs. This is arguably a general feature of media consumption. For example, in watching sports, a penalty kick constitutes a non-verbal PITQ (‘Will this goal occur?’) relative to the macro-question of the match outcome (Knobloch-Westerwick et al., Reference Knobloch-Westerwick, Prabu, Eastin, Tamborini and Greenwood2009; Richardson, Reference Richardson2020). Similar structural expectations drive suspense in movies (Comisky & Bryant, Reference Comisky and Bryant1982) and video games (Delatorre et al., Reference Delatorre, Palomo-Duarte and Gervás2016). While the theory as operationalized in this paper is limited to textual interpretation, significant progress has been achieved in ‘super-linguistics’ exporting general principles of natural language grammar, semantics and pragmatics to non-verbal domains. Research has successfully demonstrated that linguistic insights regarding structure and meaning can be transferred to sign languages (Stokoe, Reference Stokoe2005), comics, pictures, music and dance (Abusch, Reference Abusch, Gutzmann, Matthewson, Meier, Rullmann, Voloshina and Zimmermann2021; Grosz, Reference Grosz2022; Schlenker, Reference Schlenker2019). To the extent that PITQs form a fundamental pragmatic principle independent of the domain of its medial realization, one can thus expect that it can be applied to all or at least some of these domains. Consequently, an erotetic theory of narrative suspense offers a formal framework that could arguably be applied mutatis mutandis to these alternative domains as well. Future research should elucidate to what extent this more general hypothesis applies empirically.

We close this discussion by addressing a natural question about the relationship between text structure and suspense. As pointed out above, there are other theories of text coherence and text structure in addition to erotetic approaches. To what extent are alternative theories of discourse structure, focused for example on rhetorical relations, such as segmented discourse representation theory (Asher & Lascarides, Reference Asher and Lascarides2003) able to capture suspense in a meaningful or even similar way? In this paper, we have not discussed such theories at any level of detail. Also, such theories were originally focused mainly on truth-conditional and logical aspects of discourse, and they do not aim at explaining their aesthetic effects. However, recently, significant progress has been made in such frameworks in capturing some foundational aspects of literary narratives such as perspective shifts (Abrusán, Reference Abrusán, Maier and Stokke2021), free indirect discourse (Bimpikou et al., Reference Bimpikou, Maier and Hendriks2021), imaginative resistance (Altshuler & Maier, Reference Altshuler and Maier2022) or narrative frustration (Altshuler & Kim, Reference Altshuler and Kim2024). This makes it imperative for future research to ascertain whether an erotetic theory of suspense – or a competing view – might be integrated in rhetorical relations-based models of narrative texts as well.

6. Conclusion

Our paper introduced a way to operationalize a theory of suspense essentially predicated upon a linguistic model of the information structure of texts. Our experimental studies empirically validated our model by showing how it captures a significant amount of variation in measured suspense intensity in four different literary texts. This suggests that text structure, understood as incremental, online information structure is a good predictor of suspense. Moreover, PITQ specifically is a linguistic notion with a strong correlation with suspense, thus suggesting its usefulness to linguistic theory, pragmatics and interdisciplinary studies.

Data availability statement

We share all collected experiment data, annotation guidelines and data analysis under: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/M524V.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Austrian Science Fund (FWF), grant number I 4858-G awarded to E.O., and the German Science Foundation (DFG), grant number 441917136 awarded to T.K. within the project ‘The erotetic and the aesthetic. How linguistic features of literary texts determine literary suspense’. The authors acknowledge that Generative AI Gemini 2.5 Pro was used to assist in annotating and optimizing the statistical code used in this analysis for readability and in proofreading the main text of the paper. The authors reviewed and verified all outputs manually. The AI tool was not used to generate the manuscript text or scientific concepts.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.