Introduction

The last decade in Turkey has been marked by a series of pivotal political events that have dramatically reshaped its societal and political landscape. From the 2013 Gezi protests to the failed coup attempt on July 15, 2016, Turkey has undergone a turbulent period marked by the elections of June 7 and November 1, 2015, followed by the 2017 presidential referendum and subsequent highly polarized elections. These developments have not only intensified political polarization but have also oscillated between phases of de-politicization and re-politicization, crafting a charged political environment (Bedirhanoğlu Reference Bedirhanoğlu2022). As Turkey becomes increasingly notorious for its polarized political structure (Aydın-Düzgit and Balta Reference Aydın-Düzgit and Balta2019), a critical question emerges: how can we understand the underlying public ideologies within this recent political context? What could be the dominant ideological divides in Turkey? How do these ideologies interrelate, and what are the significant clusters, considering public politics, including both electoral and contentious aspects? This research aims to examine recent ideological divides and political alignments by analyzing the grassroots politics of the past decade.

By answering these questions, the study makes three contributions to the existing literature. First, it challenges traditional binary views of political ideology in Turkey and highlights the interdependencies between Turkey’s cultural and political domains via individual ideologies. Traditional analyses of political ideologies have primarily focused on elite perspectives and conventional party politics, offering only a partial view of the broader ideological currents that influence public opinion and societal actions. Second, previous global studies on ideology detection using computational tools have often replicated these theoretical shortcomings, typically reducing the complex ideological landscape to binary classifications. Methodologically, they prioritize electoral politics, which introduces an empirical bias against contentious politics. The data collection pipeline in the existing literature generally exacerbates this bias. Third, the existing theoretical positions on political ideologies in Turkey, while providing insights, highlight the necessity for a data-driven approach to delineate the dimensions and clusters of ideologies more accurately.

This research aims to fill this gap in the existing literature by employing state-of-the-art computational social science (CSS) techniques to analyze public ideologies on a more granular, province-level basis. By doing so, it aims to uncover the underpinnings of the contentious political landscape and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the ideological divides that shape political society in Turkey. Central to this research is the application of standard principal component analysis (PCA) and cluster analysis to data extracted from the Politus database, an innovative resource funded by the European Research Council (ERC). The database is designed to enhance the study of public opinion using state-of-the-art computational methods. It aggregates a vast amount of Twitter/X data, making it a valuable tool for researchers aiming to analyze and understand public opinion, stance, emotions, and ideologies on social media. The timeframe for the earliest content extends from 2011 up to the May 2023 general elections, after which the platform restricted data access through its academic application programming interface (API) tools. Politus stands out for its use of deep-learning techniques to classify digital trace data, moving away from traditional lexicon-based approaches, which enables more accurate interpretations of text and network data (Yörük et al. Reference Yörük, Atsızelti, Kına, Duruşan, Gürerk, Yardı, Hürriyetoğlu, Mutlu, Etgü, Koyuncu and Topçu2025). This database is particularly suited for exploring contentious politics by capturing a broad spectrum of public ideologies – from local levels, such as Kemalism, Turkish nationalism, and the Kurdish National Movement, to global and regional ideologies like conservatism, social democracy, feminism, socialism, and Islamism. After extracting tweet-level data from the Politus database, I applied a two-stage transformation to mitigate measurement and sampling errors embedded in social network data in general.

In the study, PCA effectively condenses an eight-dimensional ideological space into a two-dimensional coordinate plane, successfully capturing 70 percent of the total variance among ideologies and thereby demonstrating strong explanatory power. The first dimension is the traditional political spectrum, ranging from left to right. The second dimension, which runs perpendicular to the first, is the cultural–religious spectrum that spans from secular to religious orientations. This axis reflects the deep-seated cultural influence that intertwines with political ideologies in Turkey, highlighting significant divisions such as conservatism and Islamism versus Kemalism.

Cluster analysis further identifies distinct groups based on their ideological leanings. This analysis reveals three principal clusters, each characterized by unique combinations of political and religious attributes. The first cluster predominantly consists of individuals who hold centrist and right-wing views with less emphasis on religiosity. The second cluster is more religiously inclined and leans towards the right, sharing centrist views that represent a blend of nationalist and religious conservatism. This group aligns with the ideologies typically associated with the current government coalition, comprising the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi; AKP) and the Nationalist Movement Party (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi; MHP). The third and distinct cluster captures the ideological stance of the Kurdish region, which is left-leaning yet displays a significant religious component, distinguishing it from the first two clusters. Through the findings of PCA and cluster analysis, the study provides a comprehensive overview of the ideological orientations that define Turkey’s contentious political environment, which also helps to understand electoral dynamics.

In the subsequent sections, I will first explore two distinct bodies of literature: one on computational analysis that addresses the task of ideology detection and another that examines ideological divides in Turkey, with a particular focus on theoretical constructs and empirical shortfalls. I will then introduce the data used in this analysis, including the definition of each ideology within the Politus database, as well as the specific empirical strategy employed in this research. Following this, I will present the results obtained from the empirical models. Finally, I will discuss these findings and assess their implications for the current political landscape in Turkey.

Ideology detection using CSS tools

The burgeoning field of CSS has witnessed a rapid evolution over the last decade (Edelmann et al. Reference Edelmann, Wolff, Montagne and Bail2020), significantly enhancing researchers’ ability to detect political and ideological tendencies through computational techniques alongside traditional statistical tools (Doan and Gulla Reference Doan and Gulla2022). Substantial research in the past decade has focused on automatically analyzing political speeches and communications, employing datasets consisting of parliamentary documents and statements from politicians (Rheault and Cochrane Reference Rheault and Cochrane2020). Parallel to the studies on politicians, researchers have also continued to scrutinize public ideologies through surveys (Doering et al. Reference Doering, Davies and Corrado2023). For the last few years, Twitter has become a significant source of data due to its openness and the voluminous political discussions it hosts, making it a preferred platform for research until at least May 2023, when the platform limited data access for researchers (Preoţiuc-Pietro et al. Reference Preoţiuc-Pietro, Liu, Hopkins, Ungar, Barzilay and Kan2017). However, the ideologies of ordinary people still occupy a relatively small space in existing research, and researchers primarily focus on analyzing the ideologies of political elites. Despite researchers sometimes measuring the ideologies of ordinary users, as exemplified by Gu et al. (Reference Gu, Chen, Sun and Wang2017) and Barbera (Reference Barbera2015), they often access these users through their interactions with politicians. This method creates a circular bias against contentious politics. However, the sociological perspective adopted in this research suggests that public ideologies may emerge and exist entirely through grassroots political dynamics.

Upon delving deeper into the methodologies used for analyzing public ideologies, it becomes clear that the approaches employed are varied. Some studies leverage textual data from tweets of users (Baly et al. Reference Baly, Karadzhov, Saleh, Glass, Nakov, Burstein, Doran and Solorio2019; Prati and Said-Hung Reference Prati and Said-Hung2019) while others analyze their networks (Barbera Reference Barbera2015; Gu et al. Reference Gu, Chen, Sun and Wang2017). As outlined by Doan and Gulla (Reference Doan and Gulla2022), while many studies in ideology detection have traditionally employed “classical techniques” such as n-grams and word embeddings, only six studies have embraced deep learning. As an important exception, for instance, an earlier study by Djemili et al. (Reference Djemili, Longhi, Marinica, Kotzinos and Sarfati2014) distinguished between ideological and non-ideological texts using linguistic rules. Ideology detection research typically treats ideology as a classification task, often binary, and relatively few studies have integrated network-based metrics like follows, retweets, and likes (Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Song, Xu, Ren and Sun2020). Researchers, further, typically concentrate on assessing political attitudes during elections, thus perpetuating biases against contentious politics (Conover et al. Reference Conover, Gonçalves, Ratkiewicz, Flammini and Menczer2011; González-Bailón et al. Reference González-Bailón, Lazer, Barberá, Zhang, Allcott, Brown, Crespo-Tenorio, Freelon, Gentzkow, Guess, Iyengar, Kim, Malhotra, Moehler, Nyhan, Pan, Rivera, Settle, Thorson, Tromble, Wilkins, Wojcieszak, de Jonge, Franco, Mason, Stroud and Tucker2023). This indicates a limitation in current approaches since public ideologies extend beyond just electoral contexts.

Moreover, many analytical methods default to binary classification or unidimensional analysis, with only a few studies challenging this approach. Instead of a binary classification, Preoţiuc-Pietro et al. (Reference Preoţiuc-Pietro, Liu, Hopkins, Ungar, Barzilay and Kan2017) detected conservative and liberal ideologies, ranging from extreme to moderate positions, in the United States (US) context. A contributing factor to this limitation is that many researchers base their frameworks on the binary political structure standard in the US, which may not accurately capture the complexity of political ideologies in other contexts. Accordingly, Doan and Gulla (Reference Doan and Gulla2022) have noted a scholarly disinterest in non-English datasets in their review, which introduces challenges in model training due to linguistic complexity and diversity. This highlights a crucial gap for ideology detection research in the field of CSS.

In the Turkish context, more specifically, the recent study by Cem Çalışkan (Reference Çalışkan2024) explores ideologies during the pandemic, utilizing a lexicon-based approach. This study does not rely on text-based machine learning (or deep learning) models or network analysis. However, interestingly, Çalışkan’s work diverges significantly from the typical left–right ideological spectrum, instead reflecting a secular–religious dichotomy. This theoretical choice is crucial within the scope of this paper, indicating a nuanced understanding of ideological dimensions in non-Western contexts.

In light of these current shortcomings in the CSS scholarship, it becomes evident that ideology detection requires artificial intelligence-driven examination of both the content of tweet texts and their relational position within social networks. Furthermore, shifting the focus from politicians to the public is essential for better integrating electoral and contentious politics, as ideologies hold significance beyond electoral contexts. Electoral politics and politicians’ speeches, networks, and texts are significant for understanding public ideology, provided they accurately reflect people’s actual ideological leanings. Therefore, this paper suggests using a novel database for the Turkish case, namely the Politus database, that initiates research on ordinary users’ tweets based on a large corpus, uses deep learning techniques for classification instead of lexicon-based approaches, represents the whole Twitter space due to its data collection pipeline, and progressively integrates network-based metrics (see Yörük et al. Reference Yörük, Atsızelti, Kına, Duruşan, Gürerk, Yardı, Hürriyetoğlu, Mutlu, Etgü, Koyuncu and Topçu2025). This approach offers a more comprehensive understanding of the entire spectrum of public ideologies and the broader political landscape, encompassing both electoral and contentious politics. Additionally, moving beyond binary classifications, the Politus database incorporates various local-level ideologies, such as Kemalism and the Kurdish National Movement, alongside ideologies with global and regional representation like feminism, socialism, and Islamism. A detailed description of the Politus database will be presented below and can be accessed via Yörük et al. (Reference Yörük, Atsızelti, Kına, Duruşan, Gürerk, Yardı, Hürriyetoğlu, Mutlu, Etgü, Koyuncu and Topçu2025).

Ideological divides in Turkey: theoretical constructs and empirical shortfalls

Clustering the ideological leanings of the public using quantitative data has long been a practice in social sciences. For instance, in an analysis based on nationally representative survey data, John Fleishman (Reference Fleishman1986) identified six distinct ideological clusters among the US public, ranging from the most conservative to the most liberal. More recently, analyzing eighty-three different societies via the World Values Survey and the European Values Study between 2008 and 2014, Noël et al. (Reference Noël, Thérien and Boucher2021) demonstrated that the left–right divide still significantly matters in a global context, but to varying degrees, based on gross domestic product, democracy levels, and secularization within countries.

In contrast, empirical research on ideological clustering in Turkey remains scarce, with only a few exceptions. Candaş (Reference Candaş2023) proposes a purely theoretical two-dimensional space for ideological mapping: the x-axis representing the left–right spectrum and the y-axis delineating the divide between Islamism and Westernism. While theoretically innovative, Candaş’s model lacks empirical grounding and omits critical contemporary issues, such as the Kurdish question – a significant and ideologically potent division. Furthermore, the study does not provide empirical criteria for deciding what constitutes an axis or an intermediary category, such as whether Kemalism itself should be considered an axis.

Yağcı (Reference Yağcı2022) adopted a more classical quantitative methodology, surveying nearly 2,000 individuals about their left–right orientation and analyzing the determinants of these self-identifications. The findings suggest that secularism is a more significant determinant of leftism in Turkey than economic factors, such as public property or redistribution, and even gender equality. Similarly, the study of Aydogan and Slapin (Reference Aydogan and Slapin2015) indicates that the Turkish party system is unique, characterized by upper-class support for the center-left Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi; CHP), poorer voter support for the right, a religious–secular divide defining the left–right dimension, the CHP’s historical ties to the bureaucracy and military, and reversed ideological positions, with the CHP using populist rhetoric typically associated with right-wing parties in the West.

According to the analysis of Çarkoğlu (Reference Çarkoğlu2007) on the individual-level determinants of people’s left–right self-placement,

“Left” is characterized by progressive, tolerant, democratic attitudes with low levels of religiosity and critical evaluations of the economic policy performance of the government. “Right”, on the other hand, is characterized by more trusting and happy individuals who are of low tolerance levels. The right wing is also more prone to maintenance of the status quo, more state authoritarianism, and less democracy in its value predispositions. Individuals who approve of Shari’a rule in the legal system of the country also tend to group themselves in the right-wing (p. 268).

His findings show that the distribution of people on the left–right ideological self-placement in Turkey is heavily influenced by cultural parameters such as religiosity. However, what if this self-placement is indeed a function of some other ideological axis, driven by cultural divides? The dependent and independent variables need to be better separated conceptually. Given Turkey’s highly politicized context, it is reasonable to consider dimensions such as secularism, religiosity, and Westernism as part of the ideological scale, or, in other words, the dependent variable. The findings of Çarkoğlu and other researchers empirically support this approach while also theoretically highlighting the gap. To determine the ideological axes in current politics, it is essential to consider the diverse individual ideologies within the public in Turkey, given the scholarly need to reexamine ideological divides and develop a more comprehensive analytical model, as the unique conditions of politics in Turkey cannot be explained within a one-dimensional left–right spectrum.

Further, in Turkey, the theoretical positions established by intellectuals on ideologies also reflect local dynamics and historical contexts. For instance, in line with the findings of Aydogan and Slapin (Reference Aydogan and Slapin2015), Küçükömer (Reference Küçükömer2012) posits that in Turkey, what is considered left is often right and vice versa – a viewpoint that underscores the unique impacts of anti-imperialism and anti-Westernism on local dynamics. Mardin (Reference Mardin, Türköne and Önder2006) recommends interpreting Turkish ideologies through a center–periphery dialectic, providing a framework that elucidates the socio-political stratifications within the country. Meriç (Reference Meriç2018) adopts a more critical stance, dismissing ideologies as confining and irrational, and argues against strict adherence to any ideological line. Meanwhile, Bora (Reference Bora2018) argues that claims dismissing the left–right distinction as outdated are essentially rooted in a right-wing perspective, offering a critique of contemporary political discourse in Turkey.

While these theoretical positions are insightful, they underscore the need for a data-driven approach in the study of political ideologies. Empirical data should be used to determine the dimensions and the number of ideological clusters accurately. Previous cluster analyses of ideologies have been conducted based on voters’ party preferences, largely ignoring contentious political spaces (e.g. see Çarkoğlu Reference Çarkoğlu2009). The approach followed in this research will not only validate or challenge these theoretical positions but also provide a more detailed and quantitative mapping of ideological orientations at the grassroots level. Accordingly, this paper addresses several key inquiries concerning the ideological landscape in Turkey. It seeks to identify the significant ideological divisions within Turkey’s ideological spectrum and explores how these different ideological stances interrelate. Additionally, it examines how various political clusters are distributed across Turkey’s ideological map, aiming to provide an exploratory overview of the country’s political sociology through the lens of contentious politics.

Methodology

Data

The analysis employs standard PCA and cluster analysis on eight ideologies in Turkey: Turkish nationalism; Islamism; Kemalism; conservatism; socialism; feminism; the Kurdish National Movement; and social democracy, utilizing data derived from the Politus database. The Politus project employs a CSS methodology to extract and analyze public opinions in Turkey systematically. It develops a data platform that offers representative, frequent, multilingual, and privacy-conscious panel data on significant political and social trends within Turkey. This platform aggregates and analyzes social media users’ digital data to make nationwide predictions about public opinions, including the popularity of certain ideologies, support ratings for governments, and political behaviors, such as voting trends. These projections are geographically detailed and categorized by demographic factors, including age and gender. Data collection begins on Twitter, using ethically approved deep-learning models and natural language-processing tools. The pipeline is entirely compliant with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and is monitored by the ERC ethics committee. Accordingly, the data used in this research are completely anonymized, with any user- and tweet-level identifiers removed before the PCA and cluster analysis.

For training the language models, a meticulously vetted corpus of tweets, annotated by social and political science graduate students and reviewed by a domain expert, was used. The annotation process involved categorizing tweets based on their political or ideological content, excluding media or external quotes. A transformer-based pre-trained language model, further enhanced by training with these annotations, was employed to classify tweets aligned with specific ideologies, achieving an F1 macro score between 70 and 90 percent on its test set. The database includes comprehensive information on Twitter users in Turkey, starting with data from the top 100 most-followed accounts, which represent approximately 55 million users. From this pool, I first identified 6 million unique Twitter users (N = 6,682,284). Then, using the Politus project’s rule-based location detection tools on users’ tweets and description fields, I extracted province-level location information for 4 million users (N = 4,188,844). I removed users who had no interactions during the relevant period, reducing the number to 1 million (N = 1,158,865). Focusing on users who posted or interacted with at least one tweet predicted to be positive for any ideology, I excluded users who did not send or interact with any ideological tweets. The final dataset comprises 481,041 users who sent a total of 53 million tweets, with approximately 3.5 million being ideological tweets (N = 3,426,221).

As described in Yörük et al. (Reference Yörük, Atsızelti, Kına, Duruşan, Gürerk, Yardı, Hürriyetoğlu, Mutlu, Etgü, Koyuncu and Topçu2025), the annotation process for ideologies involves categorizing tweets based on their direct connection to specific ideological themes. In total, 10,000 tweets were analyzed and assigned one of two labels: “1” for those explicitly related to a given ideology and “0” for those that were not. This classification method prioritizes identifying core ideological principles rather than capturing every opinion expressed by political figures or their supporters. The primary goal is to identify and analyze political narratives and sentiments within tweets, interpreting them as components of broader ideological frameworks.

Notably, a tweet is considered ideological only if it directly expresses themes, principles, or rhetorical elements associated with specific ideological frameworks – that will be shared in the next section. Tweets were not categorized based on indirect associations or presumed beliefs of ideological groups unless clearly articulated. Coders identify recurring linguistic patterns, arguments, and references that align with well-established ideological discourses. Ideologies are treated as structured narratives with distinct “grammars” and lexicons, meaning that a tweet must explicitly articulate an ideological stance to be labeled accordingly. This ensures that the annotation process remains systematic and avoids subjective interpretation.

The Politus database has been previously presented and validated in several studies. Examining political support for candidates in the 2023 elections using the Politus database, Yörük et al. (Reference Yörük, Atsızelti, Kına, Duruşan, Gürerk, Yardı, Hürriyetoğlu, Mutlu, Etgü, Koyuncu and Topçu2025) analyzed the geographical distribution of various ideologies. To assess the accuracy of the Politus models’ individual-level predictions, Kına et al. (Reference Kına, Atsızelti, Nişancı, Yörük, Hürriyetoğlu, Yardı, Gürerk, Etgü, Akbulut, Duruşan and Turbic2024) and Kına (Reference Kına and Ünver2025) validated the dataset’s metrics. This study, however, makes a distinct empirical contribution by identifying Turkey’s core ideological axes and clusters through province-based relationships among individual ideologies and proposing a concise theoretical framework for understanding the country’s grassroots politics.

Ideologies in Turkey

Before delving into the empirical models, this section outlines and summarizes each ideology, referring to the original definitions used in the Politus project. In developing the annotation manual and defining various ideologies, the project primarily relied on the seminal work Cereyanlar: Türkiye’de Siyasi İdeolojiler (Bora Reference Bora2020), also known as “Currents: Political Ideologies in Turkey.”Footnote 1 This pivotal Turkish book offers an in-depth historical analysis of ideologies uniquely relevant to Turkey, including Kemalism, Turkish nationalism, and the Kurdish National Movement, as well as local manifestations of globally recognized ideologies such as socialism and feminism. The Politus project uses Bora’s comprehensive analysis as a foundational reference. Although the ideologies used in this study are mainly derived from Bora’s work, they differ in that they focus on public ideology rather than the ideologies of political elites. In reinterpreting Bora’s ideologies, the Politus database aims to both effectively summarize the existing theoretical framework and adapt it in a way that captures its public reflections.

The concept of public ideology in this research, more specifically, refers to the collective expression and manifestation of ideological positions at the societal level, distinct from the formalized ideological stances of political elites, party leaders, intellectuals, or opinion leaders. Rather than being confined to elite discourse, public ideology emerges through the beliefs, attitudes, and sentiments of the general population, shaping political culture, social movements, and contentious politics. It is articulated in everyday political discussions, media consumption, and digital interactions. Therefore, public ideology represents how broader ideological frameworks are internalized, adapted, and reinterpreted by individuals and communities. Unlike elite-driven ideology, which is often strategic and programmatic, public ideology reflects grassroots-level ideological currents that may be more fluid, fragmented, and shaped by historical, cultural, and regional contexts. Below, I provide summarized definitions of each ideology included in this research.

Turkish nationalism serves as a foundational aspect of the nation-state-building project in Turkey and plays a central role in its official ideology. This form of nationalism varies as it intertwines with other ideological strands such as Turkism, Islamism, conservatism, and secularism, reflecting the diverse social groups within the country. Although these variants offer different interpretations of national identity, they collectively contribute to the dynamic and multifaceted nature of Turkish nationalism. It is a pervasive ideology that often coexists with other ideological positions.

Conservatism in Turkey reflects a traditionalist skepticism toward rapid and comprehensive social change, favoring instead the preservation of established social norms and hierarchies. This ideology has its roots in the response to the modernizing and reformist efforts during the late Ottoman and early Republican periods, which sought to westernize and secularize Turkish society. Over time, Turkish conservatism has adapted, engaging with liberal democracy and capitalist market institutions while maintaining its core identity protection against perceived secularist overreaches.

Islamism is an ideology that seeks to structure state and society according to Islamic principles, as derived from the Quran. Historically linked to the National View (Milli Görüş) movement and various political groups, Islamism in Turkey has often positioned itself against the secularist and Western influences of the official Kemalist ideology. Today, it remains a significant force, particularly in more religious regions, advocating for policies that reflect Islamic values in public life and governance while occasionally clashing with nationalist perspectives.

Kemalism is the cornerstone ideology of the Republic of Turkey, emphasizing reform and nation-state building. Its principles include statism and secularism, with a historical emphasis on rescuing the state from decline during the Ottoman era. The Kemalist form of nationalism aims to set itself apart from ethnocentric and racist views by defining the nation as a collective of the Republic’s citizens. A key element of Kemalist ideology is statism, which prioritizes the established institutional framework of the Republic over participatory or democratic politics.

Social democracy advocates for interventions in the economy and society to promote social justice within a capitalist framework. This ideology supports a range of progressive policies aimed at reducing inequality and establishing a comprehensive welfare state. Distinct from socialism, it does not emphasize class struggle but instead seeks to improve living standards and address economic disparities through democratic means and social reforms.

Socialism advocates for the collective or governmental control over the production and distribution of goods, aiming to diminish the wealth and power disparities inherent in capitalist societies. This ideology supports a radical restructuring of society to achieve equity and justice, often through revolutionary means. Socialism critiques the capitalist system and envisions a society where the working class can rise to power and create an equitable social structure.

Feminism challenges the patriarchal structures that enforce gender inequalities and strives for equity across various spheres of life. This broad ideology encompasses a variety of movements that address issues ranging from reproductive rights to economic inequality, advocating for systemic change. Feminism seeks to reevaluate and transform societal norms to ensure fairness and justice for all genders, impacting discussions on global issues and cultural practices.

The Kurdish National Movement ideology in Turkey advocates for greater cultural and political rights for Kurds within the existing state structure. It emphasizes cultural preservation, education in Kurdish, and political representation, alongside broader goals of decentralization and environmental sustainability. Inspired by libertarian socialism, the movement advocates for increased regional autonomy and a stateless society organized through direct democracy, promoting peaceful coexistence and the resolution of ongoing conflicts.

To illustrate how each ideological category manifests in everyday political discourse on Twitter, a representative sample tweet has been included in the Appendix for each of the eight ideologies analyzed in this study.

Empirical strategy

Twitter data, like most social network data, are subject to two fundamental errors or biases: measurement and sampling errors (Sen et al. Reference Sen, Flöck, Weller, Weiß and Wagner2021). Measurement error primarily stems from the ability of some users to manipulate data through the volume of tweets they post. There is a substantial disparity in user engagement levels; some users might interact with content over 100 times in a single day, while others may not share anything for weeks. This imbalance leads to a measurement error known as the vocal user problem. Sampling error, on the other hand, primarily arises because Twitter users may not be representative of the broader population in Turkey. Therefore, this study acknowledges these biases and does not argue that Twitter accurately represents the public in its current form. To mitigate these biases, however, it proposes a rule-based solution. After the data were collected via Twitter’s academic API tools, tweet-level ideology predictions were generated, and the database was filtered accordingly. A two-stage transformation process was then implemented to mitigate the impact of vocal users and enhance the representativeness of the predicted measures.

Initially, I transformed tweet-level predictions into user-level aggregates. In this rule-based approach, first, I divided the number of tweets a user posted (or interacted with) about a specific ideology by their total number of ideological tweets. This score represented the user’s alignment with that ideology, such as their “socialist score.” This method penalized users who interacted extensively, ensuring a more balanced scoring system. In addition to the original tweets, I also considered likes and reposts as endorsements and took into account the author-generated component of quote and response tweets. This ideology-detection pipeline focused on text or content-based predictions and expanded the analysis to include measures of dynamic inter-user interactions within their networks. This adjustment shifts the focus from counting tweets to counting users’ scores, thereby reducing measurement errors caused by overly vocal users who can significantly distort the data.

In the second stage, I aggregated the user-level ideology scores to the province level by calculating the mean values of users in each province. This transformation accounts for the uneven distribution of Twitter activity across different geographic regions. Larger provinces tend to have higher Twitter participation rates, while smaller provinces often exhibit lower engagement levels. As a result, a direct comparison of raw user-level ideology scores across provinces would be misleading, as it would disproportionately reflect the ideological leanings of provinces with a higher concentration of active Twitter users. The user to province transformation, therefore, is a balancing procedure that adjusts for these disparities. Instead of treating all provinces as equally representative, province-level averages provide a weighting mechanism based on the relative number of active Twitter users in each location. This approach ensures that provinces with a high volume of Twitter engagement do not dominate the overall ideological composition while also preventing smaller provinces from being underrepresented in the aggregated measures.

By shifting the focus from individual users to province-level aggregates, this methodology enhances the representativeness of the estimated ideological distributions, reducing location-based sampling errors. The two-stage transformation employed in the research ensures that users who tweet more frequently and provinces with a higher number of users are appropriately penalized. This method helps avoid the respective measurement and sampling errors associated with uneven user participation and variation between different provinces, although it does not entirely solve the problem.

Following the transformation, the data were restructured into a matrix format with eight ideologies across eighty-one provinces. The dataset was filtered to include only the most recent available data, covering the one year preceding the latest possible time point. Specifically, the earliest tweets in the dataset span from May 2022 up to the May 2023 general elections, after which Twitter restricted data access through its academic API tools. In the Politus project, emotions and stance variables are treated as dynamic, whereas ideology variables are regarded as static, similar to demographic characteristics. While ideologies can exhibit some degree of temporal variability, this article, following Yörük et al. (Reference Yörük, Atsızelti, Kına, Duruşan, Gürerk, Yardı, Hürriyetoğlu, Mutlu, Etgü, Koyuncu and Topçu2025), disregards this aspect and focuses on an aggregate-level comparison.

To explore ideological divides, I applied two standard exploratory statistical techniques – PCA and cluster analysis – to this dataset. These two techniques are well-known basic unsupervised machine-learning models and are often used together in scientific research due to their ability to provide insightful exploration of complex data structures (Feldman et al. Reference Feldman, Schmidt and Sohler2020; Margaritis et al. Reference Margaritis, Soenen, Fransen, Pipintakos, Jacobs and Blom2020; Rahman and Rahman Reference Rahman and Rahman2020). PCA is a technique used to reduce the complexity of high-dimensional data while preserving underlying trends and patterns. It achieves this by converting the original variables into new variables that are linear combinations of the original ones, organized orthogonally to minimize overlap, with the first few capturing most of the variance from the original dataset. Cluster analysis complements this by organizing the data into groups or clusters where members are more similar to each other than to those in different clusters. This method is commonly employed in fields such as data mining and image analysis to identify distinct patterns in data, typically after reducing dimensions through methods like PCA.

Therefore, PCA is expected to yield decorrelated, orthogonal dimensions across these eight ideologies for the eighty-one provinces. This process helps isolate the unique variances associated with each ideology, ensuring that the dimensions are independent of one another. Subsequently, cluster analysis will be used to group the provinces based on these principal dimensions extracted by the PCA. This approach enables a more precise distribution of provinces, highlighting similarities and differences in ideological patterns across various regions.

Results

PCA

The PCA in this research reveals a compelling ideological landscape of Turkey, offering insights into the prevailing political and cultural divides. The transformed data resulted in a two-dimensional space, with the provinces distributed accordingly. The analysis yielded two principal components (PCs) that account for a substantial proportion of the variance within our dataset: PC1 accounts for approximately 38.87 percent, and PC2 for about 34.75 percent. Together, they encompass 73.62 percent of the total observed variance, suggesting a strong structure in the dataset and indicating that these components effectively capture the most significant ideological variations among the provinces. While political ideology is often conceptualized as primarily one-dimensional, the relatively close explanatory power of the second component suggests that ideological variation in this context cannot be fully captured by a single axis alone. The presence of a second significant dimension implies an additional source of differentiation beyond the primary ideological divide.

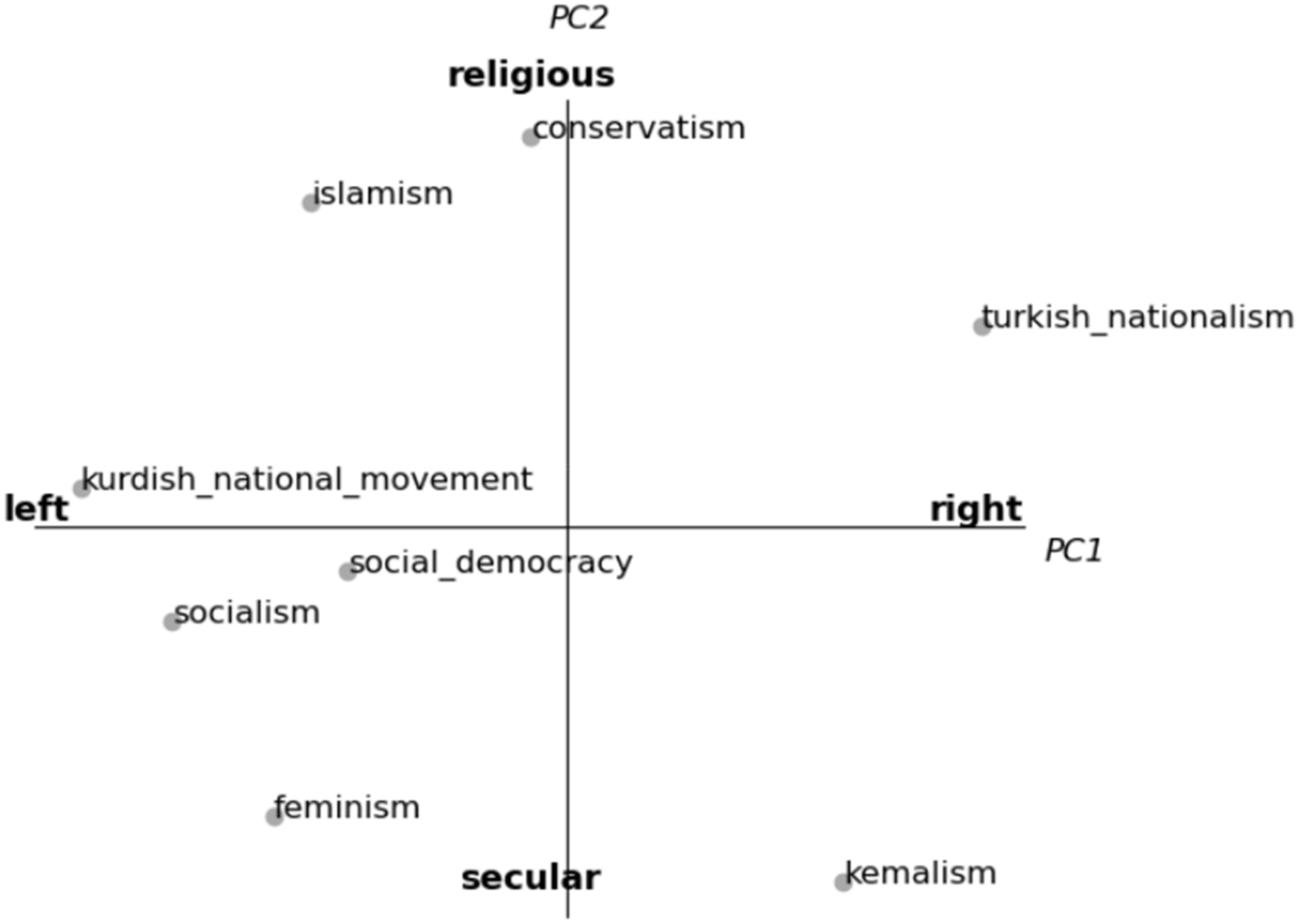

Given that PC2 contributes nearly as much as PC1, its inclusion is not merely for visualization purposes but instead reflects an empirically meaningful structure in the data. Failing to consider this secondary dimension could result in an oversimplified representation of ideological distributions across provinces. Therefore, instead of assuming a strict unidimensional framework, our approach acknowledges the complexity of political orientations and ensures that both dominant ideological patterns are incorporated into the analysis. The contribution of each additional dimension drops sharply after PC2, with PC3 and PC4 accounting for only 12 and 6 percent of the total variance, respectively, as shown in Figure 1. The loadings of eight ideologies on two PCs are presented as vectors in Figure 2. Based on the ideological loadings for the two dimensions extracted by the PCA, this research describes these two main parameters as the political and cultural dimensions of ideologies within the Turkish political context.

Figure 1. Explained variance ratios of additional components.

Figure 2. Ideological loadings on the principal components (PCs).

PC1 is oriented along the horizontal axis, labeled as “left to right,” and seems to encapsulate the traditional left–right political alignment. On this axis, ideologies traditionally associated with the left, such as socialism, social democracy, feminism, and the Kurdish National Movement, exhibit negative loadings, implying a more substantial presence or preference within provinces located on the left side of the plot. Conversely, Turkish nationalism and Kemalism exhibit positive loadings, positioning them on the right side, which is indicative of a right-leaning political inclination in provinces that align with these ideologies. PC2, which runs along the vertical axis as “secular to religious,” distinguishes between the secular versus religious leanings of the provinces. Here, Islamism and conservatism show significant positive loadings, denoting a strong association with the religious end of the spectrum. Kemalism and feminism are notable for their negative loadings, aligning them with secularism within this component. Note that this study does not rely on ideological self-placement scales. Instead, ideological orientations are inferred inductively through patterns in respondents’ evaluations of key political issues. By mapping these evaluations onto a two-dimensional structure using PCA, the study avoids potential distortions introduced by self-labeling, particularly in contexts where “left” and “right” carry ambiguous or contested meanings.

Figure 3 illustrates the spatial configuration of eight ideologies along two principal dimensions: left–right and secular–religious. The distribution reveals that Turkish public ideologies are structured by intersecting political and cultural axes rather than a single continuum. Notably, Islamism and the Kurdish National Movement cluster in the religious-left quadrant, reflecting their shared peripheral and oppositional character. Feminism, socialism, and social democracy align with the secular left, while conservatism and Turkish nationalism occupy the right, with differing cultural orientations. Kemalism stands out as secular-right, consistent with its state-centered and modernist roots. This configuration highlights the multidimensional and culturally embedded nature of ideological divides in Turkey. Interestingly, the orientation of the ideological vectors in the PCA biplot suggests an underlying coherence that cuts across the two dimensions, resembling a single line of political contestation. This visual pattern supports the idea that ideological divisions, while analytically multidimensional, may be experienced and articulated by the public in more unified or directional ways.

Figure 3. Two-dimensional space of the principal components (PCs).

Further, the distance matrix presented in Figure 4 elucidates the relative proximity and divergence among the ideologies. This matrix is instrumental in understanding the ideological relationships and potential overlaps. The values in the matrix range from 0.00, indicating no distance or complete overlap in ideological expression between provinces, to higher values, signifying greater ideological divergence. Notably, the ideologies of Turkish nationalism and conservatism are relatively close, with a minimal distance of 1.01. This closeness suggests that where Turkish nationalism is prevalent, conservative ideology might not be far behind. On the other end of the spectrum, we observe a substantial distance between Kemalism and the Kurdish National Movement, with values exceeding 1.75. This distance is reflective of divergent political traditions and priorities associated with each ideology.

Figure 4. Distances between ideology pairs.

Islamism, characterized by its stronger religious underpinnings, stands apart from both Kemalism and feminism, with distances of 1.90 and 1.43, respectively. These values underscore the clear ideological divide between religious and secular or leftist orientations within the provinces. Interestingly, feminism shows varying degrees of proximity to other ideologies, with the smallest distance to socialism at 0.54, suggesting shared principles or allied positions, perhaps on social issues or equality. Conversely, feminism is most distant from conservatism and Turkish nationalism, with distances of 1.79 and 1.70, respectively, underscoring the sharp contrast between feminist advocacy and right-wing ideologies, likely due to differing views on gender roles and traditional values. The Kurdish National Movement is closely aligned with socialism, with a distance of 0.37. This alignment likely reflects shared goals for more egalitarian and decentralized forms of governance, as well as common perspectives on minority rights and social justice. As expected, its greatest distance is from Turkish nationalism. Interestingly, the second closest ideology to the Kurdish National Movement is Islamism, with 0.81. Further, a correlation-based scatterplot illustrating all pairwise relationships among the eight ideologies is provided in the Appendix (see Appendix Figure 1, top and bottom panels) to offer a more interpretable view of their affinities.

Cluster analysis

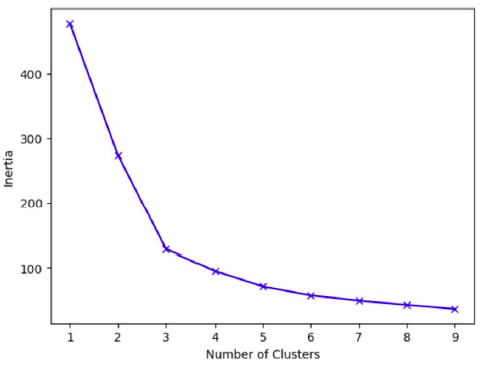

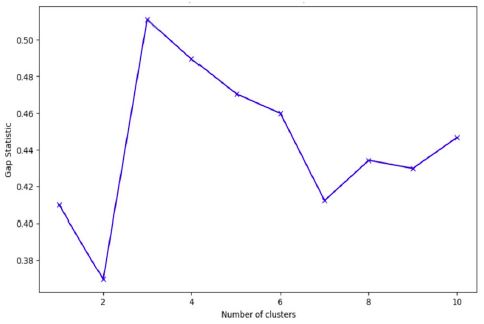

The cluster analysis identified three distinct clusters based on their political and religious characteristics, as demonstrated in Figures 5 and 6. To detect the optimal number of clusters, I analyzed inertia using the elbow method and gap statistics to compare the performances extracted from within-cluster variations for alternative cluster numbers numerically, which are presented in the Appendix.Footnote 2 These clusters provide a detailed picture of how the ideologies coalesce geographically and politically within Turkey. Figure 5 presents a scatter plot against the backdrop of two PCs: PC1, which represents the political spectrum from left to right, and PC2, which distinguishes between secular and religious orientations. Here, provinces are categorized into three clusters, each represented by a different color:

-

1. Center/right-wing and secular cluster: provinces within this cluster are visualized in blue and are primarily located on the west and south coasts of the map, signifying a central and right-wing position on the political spectrum, coupled with secular tendencies. This cluster suggests the presence of urban areas with a more moderate political view and a less religious orientation compared to the two alternative clusters.

-

2. Center/right-wing and religious cluster: provinces in this cluster, colored green, appear on the right side of PC1 and are dispersed across the PC2 axis, indicating a combination of centrist and right-wing political leanings and religious orientations. The provinces in this cluster are mostly located in Central Anatolia and the east of the Black Sea. Note that right-wing orientation of this group is higher than the first cluster.

-

3. Left-wing and religious cluster: this cluster is represented by gray dots and occupies east and southeastern Turkey, reflecting left-wing political views alongside religious sentiments. The provinces grouped here are characterized by their alignment with religious values while simultaneously endorsing leftist ideologies, indicating a distinctive ideological blend prevalent in certain regions.

Figure 5. Distribution of clusters on the principal components (PCs).

Figure 6. Distribution of clusters on the map of Turkey.

The cluster analysis highlights distinct ideological patterns across different regions of Turkey. The first cluster is characterized by a secular and center-oriented outlook, often associated with the CHP. The second cluster reflects regions with stronger conservative and religious tendencies, aligning with parties such as the AKP, MHP, the New Welfare Party (Yeniden Refah Partisi; YRP), and the Great Unity Party (Büyük Birlik Partisi; BBP). Additionally, the third cluster represents a left-wing and religious ideological composition, predominantly observed in areas with a significant Kurdish population and often linked to the People’s Equality and Democracy Party (Halkların Eşitlik ve Demokrasi Partisi; DEM). These findings suggest that Turkey’s ideological landscape is not strictly bipolar but instead comprises three distinct ideological orientations.

Discussion

In this study, the performed PCA managed to project an eight-dimensional ideological space onto a two-dimensional coordinate plane, capturing 73 percent of the variance, which demonstrates a robust explanatory capacity. The ideological tendencies in Turkey’s grassroots politics can fundamentally be explained along two axes. Essentially, Turkey’s ideological landscape is composed of two main tension points: one political and the other culturally and religiously oriented. In this research, I have chosen to define these emerging dimensions as leftism (opposed to rightism) and religiosity (opposed to secular orientation). This choice was influenced by both the approaches described in the literature above and the relative weights these ideologies hold within the PCs. Naming the left–right spectrum is not difficult, as it is the most prevalent ideological divide when considering public ideologies, both in Turkey and globally. Moreover, the proximity of ideologies such as feminism, socialism, social democracy, and the Kurdish National Movement along a specific side of the x-axis defines the character of this spectrum.

This research defines the second dimension as the cultural axis of public ideologies in Turkey. This dimension evokes what Mardin (Reference Mardin, Türköne and Önder2006) referred to as the center–periphery dynamic, highlighting the shift from the periphery to the center by the AKP since the 2010s, which is associated with Anatolian conservatism. The military–civil bureaucracy, which attempted to modernize the society with Western, secular reforms, contrasts with the periphery, representing the Islamic sectors that resisted these reforms. During the 2020s, however, it has become difficult to define this division solely in terms of bureaucratic power through Westernization, given the significant political transformations in the leading ideologies over recent decades. Nevertheless, the y-axis, or the dimension of religiosity or the cultural aspect of ideology, tends to concentrate on a conservatism/Islamism versus Kemalism dichotomy.

Thinking of the two axes together, conservatism represents the slightly right-leaning side of the religiosity pole, while Islamism indicates the slightly left-leaning side. Both forms of nationalism – Turkish nationalism (on the right) and the Kurdish National Movement (on the left) – score slightly above average in terms of religiosity. That is, both exhibit a relative abundance towards religiosity rather than secularism in Turkey’s current cultural polarization. Conversely, within the left, feminism embodies the opposite situation. Feminism represents the most secular form of the left in Turkey, though it is still not extremely secular. In this two-dimensional, bipolar space, the position of Kemalism is also noteworthy. While Kemalism appears to represent the secular side of the cultural divide, it should be noted that it slightly leans to the right.

From this perspective, an alternative labeling of the y-axis as “Localism” or an “Easternism–Westerism” spectrum could have been considered (as done by Candaş Reference Candaş2023). However, such a naming would be misleading in several ways. First, it would clearly be inadequate in explaining the position of the Kurdish National Movement in Figure 2. Candaş’s analysis, which does not sufficiently account for Kurdish ideology, examines this axis solely within the tension between Islamism and Westernization. Second, although the East–West dialectic might have had some relevance in the early Republican period, and maybe even until the early 2000s, claiming that it still holds explanatory power in today’s political tensions is theoretically challenging. Therefore, I describe this distinction as cultural.

Although Candaş’s typology is normative and not based on empirical data, it aligns remarkably well with the two-dimensional ideological space outlined above. This convergence raises a broader theoretical question: how can ideologies that diverge along distinct structural axes nonetheless produce cohesive political blocs in mainstream party politics? While the PCA and clustering results point to a multidimensional ideological structure in Turkey, such analytical distinctions do not prevent the formation of unified left- or right-wing alignments in political practice. This coherence may stem less from shared policy preferences than from shared oppositional stances. For example, both nationalist and Islamist actors may converge politically in resisting secularism or Kurdish demands, despite divergent programmatic commitments. In this sense, negative coalitions – built around common adversaries rather than shared visions – help explain the persistence of a dominant left–right axis in an otherwise fragmented ideological field.

Nonetheless, this political polarization should not obscure the more nuanced and diverse ideological landscape found among ordinary citizens. The empirical findings presented here highlight a rich plurality of grassroots attitudes that transcend binary frameworks. It is to this complex structure of popular ideology that the analysis now turns, with five further interpretive insights drawn from the data.

The first aspect of this multifaceted structure of popular ideology is based on a noticeable difference between the left and the right. Four ideologies commonly described as left-wing – the Kurdish National Movement, socialism, feminism, and social democracy – are positioned close to one another. In contrast, other ideologies exhibit a more disparate distribution along the scale. This observation can be interpreted in two ways. First, it may indicate the breadth of the hegemonic space that the right occupies in Turkey’s political society. This suggests a widespread dominance of the right across different regions. Second, it could mean that there is a higher level of ideological consolidation among left-leaning ideologies. This can be theoretically understood through the concept of intersectionality (Walby Reference Walby2007). Even if ethnic, class-based, and gender-based inequalities have independent and separate ontologies, as Walby suggests, in practice, the actors who suffer from these inequalities and adopt ideological positions experience these ideologies concurrently. So to speak, oppression brings people and their ideologies closer together. Without choosing between these two interpretations, it must be acknowledged that both make sense in the recent context of Turkey’s contentious politics.

Second, Turkish and Kurdish ideological concentrations are decisive for the alignment of the left and the right. This dichotomy fundamentally defines Turkey’s most important ideological axis. It is noted that this opposition aligns with the “shift to the right” in Turkish politics, which has been significantly intensified since the June 7, 2015 general elections, following the collapse of the Kurdish peace process between the Turkish state and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê; PKK). The Turkish–Kurdish ideological opposition appears to be the most salient dichotomy in Turkey’s recent political divide. This is also evident in the results of the cluster analysis, which will be elaborated on below.

Third, another notable point is that Kemalism corresponds to a kind of right-wing secularism, despite carrying all its hegemonic capacity throughout Turkey’s recent history. As Bora (Reference Bora2020) aptly stated, the distinct character of Kemalism has never been leftism throughout the history of the Republic. Its right-leaning character fundamentally stems from the principle of “statism.” However, Kemalism is not strictly right-wing. Specific historical periods, such as the 1970s, drew Kemalist elites and the CHP closer to the left, even giving rise to a Left Kemalist faction. The question of whether this Left Kemalism stems from an anti-capitalist political project or from anti-Ottoman secularism is worth exploring. The empirical analysis, however, suggests that Kemalism has leaned more towards the right in recent times.

Accordingly, one may rightfully ask, why does Islamism slightly lean to the left? Interestingly, the fourth inference that this research raises is based on the finding that Islamism is positioned along a left-leaning line contrary to conservatism. Similar to how Kemalism has occasionally veered left, Islamism has at times deviated from nationalist–conservative lines to establish an anti-imperialist version of an Ummah-based ideology, especially between the coups of September 12, 1980 and February 28, 1997. This version of Ummah-ism (Ümmetçilik), while not as universalist as leftist internationalism, is also not as local as nationalism. Rather than reducing it to the National View, which could be described as an organized attempt to integrate Islamism within the system (Tuğal Reference Tuğal2009), it makes sense to consider various sectors of Islamism, some of which occasionally lean left and explore alternatives outside the existing system. This form of Islamism, although exceptional, has given rise to specific eclectic forms such as the Anti-Capitalist Muslims seen during the Gezi protests in 2013. However, stating that the class struggle is the main factor that shapes soft ties between Islamism and the left is challenging. This connection is more likely established through the Kurdish issue, possibly in Kurdish provinces. A prime example of this is the long-standing employment of Islamist (or former Islamist) actors within various parties of the Kurdish movement. These cases highlight discussions around Ummah-ism and nationalism, anti-imperialism in Kurdish provinces, and demonstrate the error in conflating Islamism strictly with the AKP. This also underscores that, like Kemalism, Islamism cannot be monopolized by any single political entity.

Although the left and Islamism seem incompatible under the current conditions of political polarization, this is not as true for the grassroots as it is for the elites. In other words, the distance between the left intelligentsia and Islamist elites on one side and the closeness between the daily resistance and religiosity of the working class on the other can coexist. Therefore, from the perspective of grassroots politics, the tendency towards Islamism can also be high in worker areas where the left tendency is strong. An Islamic left has never been popular in Turkey, but due to this permeability at the grassroots level, the AKP and socialist left parties can sometimes compete in working-class areas. Historically a stronghold of Islamist parties since the 1990s, Kocaeli-Gebze as an industrial zone has also witnessed growing support for left-wing parties, such as the notable challenge posed by the Workers’ Party of Turkey (TİP) in the 2024 local elections. This suggests that ideological boundaries are more porous among the working class than they appear at the elite level.

Fifth, and finally, a detailed examination of the clusters reveals the existence of three poles in Turkey’s political landscape, significantly resembling the map from the March 2024 local elections.Footnote 3 From the perspective of contentious politics, politics in Turkey can be described not merely as bipolar but as having three main poles for the last several decades. In the 1990s, this third pole began to emerge in the realm of electoral politics. However, even during periods when this third pole has been less influential in mainstream politics, according to its claims, the Kurdish issue has profoundly impacted the alignments within party politics in recent elections, serving as a kind of litmus test.

These findings align with and expand upon recent research that highlights the democracy–authoritarianism cleavage as a dominant axis in Turkish politics. While Metin and Ramaciotti Morales (Reference Metin and Ramaciotti Morales2024) trace this realignment through member of parliament–follower relations on Twitter, their approach infers public ideology from elite-centered networks shaped by formal politics. In contrast, this study builds on a more bottom-up and comprehensive dataset directly capturing public ideological expressions, including contentious politics, across provinces and ideological registers. The identified clusters – particularly the left-leaning yet religiously inclined Kurdish profile and the secular–conservative differentiation within the center-right – suggest that while democratic backsliding reshapes elite coalitions, its reception and articulation among the public are mediated through culturally embedded and regionally differentiated ideological structures.

Conclusion

This study has employed CSS techniques to explore and map the ideological divides in the Turkish public, revealing significant insights into the political and cultural dimensions that shape the political society in Turkey. Through the use of PCA and cluster analysis on the extensive Politus database, the research has distilled Turkey’s ideological spectrum into two primary dimensions: the traditional political axis (left–right) and a cultural–religious axis (secular–religious). The results of this study illustrate that Turkey’s ideological landscape is composed of three distinct clusters, which diverge from the traditional understanding of politics within the two prominent poles. It indicates that examining the contentious political landscape can yield substantial insights into the dynamics of mainstream politics in Turkey. The first cluster, associated with the CHP and the founding ideology of the Republic, demonstrates a moderate, less religious stance and is centrist in the left–right spectrum. The second cluster, identified with the current ruling coalition (AKP–MHP), is marked by a more pronounced religious and nationalist orientation with a right-wing political stance. The third cluster, while primarily evident in regions with significant Kurdish populations, represents a unique blend of left-leaning ideologies with a softer but still significant religious undertone.

The use of empirical data is crucial not only for validating or challenging theoretical perspectives in the existing literature but also for offering a more detailed and quantitative analysis of ideological orientations across Turkey. This paper advocates for integrating these empirical data with theoretical insights. It identified and explored the major ideological divisions within Turkey’s political space to understand how these ideologies interrelate and examined the distribution of political groups across the ideological map. This approach leveraged advanced methodologies, such as the Politus database, which utilizes deep learning to analyze tweet content and interaction-based network measures, thereby capturing a broad spectrum of public ideologies beyond electoral politics. This combined methodological approach enables a more comprehensive examination of both electoral and contentious aspects of political ideologies in Turkey.

This study also contributes to CSS research by introducing a two-stage transformation to mitigate measurement and sampling biases in digital trace data. The proposed approach addresses the vocal user problem by aggregating tweet-level data to the user level. It reduces location-based sampling bias by further aggregating user-level data to the province level. By systematically correcting these biases, this methodological innovation enhances the reliability of digital trace analysis in social research.

In multiparty systems like Turkey, individuals may occasionally reverse or misinterpret conventional left–right labels while still intuitively grasping the relative positioning of political actors. Although this study does not directly capture such reversals, the consistency of the clustering patterns indicates that respondents nonetheless relate to ideological space in a structured, relational manner – defined more by perceived proximity and opposition than by fixed ideological terminology. Due to data limitations, the study cannot track how specific parties are ordered by respondents across the population, though this would be a valuable direction for future research. Another significant limitation of this study is its reliance on tweets and online interactions, which may not fully capture the breadth of political ideologies, particularly as not all segments of society are equally active or open on social media. Despite user-based and location-based weightings applied in the research, this could lead to underrepresentation or misrepresentation of certain political beliefs due to the private nature or sensitivity of expressing specific views online. Furthermore, the findings are subject to the temporal dynamics of social media, where trends can shift rapidly. The data used in this research do not account for temporal variation, which limits the data’s capacity to reflect future or past ideological states. Future research could address these challenges while also developing theoretical frameworks to explore further the findings obtained in this study.

Acknowledgments

Everyone involved in the long pipeline of the Politus project contributed to this article. I would like to extend my special thanks to all project members, especially Erdem Yörük. This work was supported by an ERC proof-of-concept grant (number 101082050).

Competing interests

The author declares no conflict of interest related to this study.

Appendix

Appendix Figure 1 (bottom panel)

Appendix Figure 1. Scatterplots of provinces based on ideological pairs.

Appendix Figure 2 (bottom panel)

Appendix Figure 2. Elbow method testing number of clusters.

Appendix Figure 3 (bottom panel)

Appendix Figure 3. Gap statistics method testing number of clusters.

Sample tweets by ideological category

1. Turkish nationalism

“Adnan Menderes’in neden asıldığını da anlatın. Türkiye Cumhuriyeti’ni ABD Emperyalizmine nasıl peşkeş çektiğini de anlatın.”

2. Conservatism

“Polisime saldıran Barış Atay denen haydut militan provokatörün derhal vekilliği düşürülsün.![]()

![]() #DevletiminYanindayimTR”

#DevletiminYanindayimTR”

3. Islamism

“Biz bize yeteriz. Müslümanlar dik durursa, bizi yıkan olmaz.”

4. Kemalism

“Türk’e isyan edenin adı ne olursa olsun, o HAİNDİR. Şeyh Sait 1925’te isyan etmiştir HAİNDİR. Buna güzelleme düzenleyenler Atatürk’e ve Cumhuriyete karşı olanlardır.”

5. Social democracy

“Asgari ücretle geçinmek mümkün değil. Kiralar, faturalar aldı başını gitti. Devlet vatandaşını bu kadar yalnız bırakamaz.”

6. Socialism

“Patronlar kârlarına kâr katarken, işçiler açlık sınırının altında yaşıyor. Bu düzeni ancak örgütlü emek değiştirebilir.”

7. Feminism

“Kadın cinayetleri politiktir! Erkek adalet değil, gerçek adalet istiyoruz. #İstanbulSözleşmesiYaşatır”

8. Kurdish National Movement

“Anadil haktır, pazarlık konusu olamaz. Kürt çocukları da kendi dilinde eğitim alabilmeli. #ZimanêZarokan”