Infant and young child feeding in emergencies (IYCF-E) is receiving growing attention within global public health and humanitarian nutrition due to the increasing frequency and severity of environmental, geopolitical and public health crises. In 2024 alone, 393 natural disasters were recorded globally, including heatwaves across Asia, droughts in Africa and the Americas and severe flooding in parts of Europe(1). These events resulted in 16,753 deaths and affected an estimated 167.2 million people. Such emergencies significantly disrupt food systems, water and sanitation services and healthcare infrastructure, placing people – particularly infants and young children – at heightened risk of malnutrition, infection and mortality(2–4). Climate change is expected to increase the frequency, intensity and complexity of emergencies globally, including in high-income settings(5,Reference Gribble, Tomori and Brodribb6) .

Infants and young children have specific nutritional requirements and are entirely dependent on caregivers to meet their feeding needs. Breastfeeding provides both a safe food source and immunological protection in emergencies(7,Reference Kouadio, Aljunid and Kamigaki8) . In cases where breastfeeding is not possible or interrupted, commercial milk formula (CMF) can be an alternative. However, poor water and sanitation conditions, mass movement of populations and overcrowding can occur during emergencies and natural disasters, and these can facilitate the spread of infectious diseases(Reference Victora, Bahl and Barros9), making the use and preparation of CMF dangerous. Infants and young children who are receiving CMF are at increased risk of morbidity and mortality due to the infection risks associated with CMF feeding as well as the absence of the immuno-protective benefits of breast milk(Reference Bartick, Reinhold and Young10), especially during emergencies(3,Reference Gribble and Fernandes11,Reference Theurich and Grote12) . Similarly, the introduction of complementary foods must be carefully managed during emergencies to avoid early introduction of inappropriate or nutritionally inadequate products(Reference Theurich and Grote12,13) . In emergencies, appropriate infant and young child feeding undoubtedly saves lives and optimises health outcomes(2).

Many high-income countries (HICs) have already low rates of exclusive breastfeeding, particularly beyond the first few weeks of life(14). Ireland, for example, has one of the lowest breastfeeding rates in Europe; in 2022, 62.4% of babies were breastfeeding on hospital discharge and 44.9% were exclusively breastfeeding(15), while also being one of the world’s largest producers and exporters of CMF(Reference Burke-Kennedy16). In such settings, reliance on CMF heightens vulnerability during emergencies where water, electricity and supply chains may be disrupted.

Recognising these risks, the World Health Organization (WHO) has called on all member states to develop formal IYCF-E preparedness plans, including specific protocols to protect breastfeeding, regulate the use and distribution of CMF and ensure access to safe, age-appropriate foods for children aged 6 to 23 months(17). Over the past two decades, key technical guidance has been developed, including the Operational Guidance on Infant and Young Child Feeding in Emergencies(2), the WHO International Code of Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes(18), the Sphere Standards(19) and World Health Assembly resolutions (WHA 63.23, 2010; WHA 71.9, 2018)(20,21) .

Despite this comprehensive framework, uptake in the development of national IYCF-E legislation and policy remains limited, particularly in HICs. According to the Global Breastfeeding Collective’s 2024 Scorecard, only 23% of countries worldwide have all three essential components in place for IYCF-E: programmes, policies and funding(14). Within Europe, none of the countries assessed by the World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative (WBTi) had a national IYCF-E policy in place, with the exception of North Macedonia(22) and no country had fully integrated IYCF-E into training for healthcare or emergency personnel(Reference Gribble and Palmquist23–Reference Bilgin and Karabayir25).

HICs often underestimate the risks posed by reliance on CMF, low breastfeeding prevalence and fragmented health systems. While some agencies, such as the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Australian Breastfeeding Association (ABA), have produced useful guidance for responders, these documents lack statutory weight and are rarely embedded in formal emergency planning frameworks(26,27) .

There have been efforts to address these gaps. In Ireland, researchers have developed an all-island IYCF-E preparedness plan outlining how governments might integrate infant feeding into emergency planning, coordination and service delivery(28). While not yet adopted, it offers a foundation for future statutory action and cross-sectoral collaboration.

This review paper examines how HICs have responded to the nutritional needs of infants and young children in recent emergencies. Drawing on case studies from several HICs, it analyses patterns of breastfeeding support, CMF management and complementary feeding practices during crises. Although this review focuses on HICs, selected examples from upper-middle-income settings are included where directly relevant to HIC-led responses. In particular, the case of Ukraine is considered due to the extensive involvement of neighbouring HICs, such as Poland, in providing cross-border IYCF-E support to displaced populations. The review identifies gaps in policy and operational readiness, with a focus on CMF-reliant settings and concludes with recommendations to strengthen IYCF-E preparedness as a public health priority.

Why infant feeding requires emergency-specific protection

Infants and young children are among the most nutritionally vulnerable populations in emergencies. Their survival depends on reliable access to safe and appropriate feeding, yet they lack the physiological resilience, mobility and autonomy to meet these needs without consistent caregiver and health system support(2,Reference Gribble and Palmquist23) . Even short disruptions to feeding routines can result in dehydration, infection, growth faltering or increased mortality, particularly in settings where water, sanitation and healthcare systems have been compromised(3,Reference Bartick, Tomori and Gribble29) .

Exclusive breastfeeding provides essential immunological protection, nutritional adequacy and a hygienic source of food and water during emergencies. However, it is frequently undermined by maternal stress, separation from infants, overcrowded shelters and a lack of breastfeeding support(Reference Russell, Haushalter and Rhoads30,Reference O’Sullivan and Kennedy31) . Where breastfeeding is not possible, the safe preparation and administration of CMF requires access to clean water, fuel, sterilisation and feeding equipment and practical guidance, all of which may be unavailable during crises(Reference DeYoung, Suh and Thomas32,Reference Callaghan, Rasmussen and Jamieson33) .

Similarly, the introduction of complementary foods after six months must be managed with care to ensure the chosen foods are age-appropriate, culturally acceptable and nutritionally adequate. Poorly regulated distribution of commercially available complementary foods (CACFs), particularly ultra-processed products, can lead to early introduction of solid food, displacement of breastfeeding and exposure to foods that are low in essential nutrients(Reference Theurich and Grote12,13) .

Given these risks, protecting infant and young child feeding during emergencies requires dedicated planning, cross-sector coordination and adherence to international standards. The sections that follow examine how breastfeeding, formula feeding and complementary feeding have been managed in recent emergencies in HICs and identify key lessons for improving preparedness and resilience.

Breastfeeding support in emergencies

Breastfeeding support is a critical yet often neglected aspect of emergency response. Comparative evidence from high-income and middle-income settings shows that breastfeeding is highly vulnerable during crises, particularly where systems lack coordinated care, trained personnel and breastfeeding-friendly environments. Experiences from Canada(Reference DeYoung, Suh and Thomas32), Italy(Reference Giusti, Marchetti and Zambri34), Ireland(Reference O’Sullivan and Kennedy31) and Australia(Reference Gribble, Peterson and George35) reveal that even in well-resourced countries, breastfeeding is disrupted when support mechanisms fail.

In Canada, during the Fort McMurray wildfire evacuation(Reference DeYoung, Suh and Thomas32), exclusive breastfeeding rates dropped significantly over this time. Mothers attributed this to the lost of access to lactation support networks and struggles with stress, mobility and public feeding in unfamiliar environments. While some women reported continuing to breastfeed for emotional or practical reasons, many were unable to do so consistently due to the absence of appropriate support systems or shelter infrastructure. In Italy, following the L’Aquila earthquake, breastfeeding was undermined by inconsistent postnatal care and outdated hospital practices such as scheduled feeds and unnecessary CMF prescriptions(Reference Giusti, Marchetti and Zambri34). While some mothers received initial support at birth, many reported being left without follow-up care or advice once discharged into unstable housing. The social expectation to breastfeed, combined with insufficient emotional and practical support, led to feelings of guilt and failure among some mothers(Reference Giusti, Marchetti and Zambri34).

Similarly, during the 2019–2020 Australian bushfires, breastfeeding was frequently disrupted by the physical and emotional demands of evacuation(Reference Gribble, Peterson and George35). Many mothers, particularly those who were on their own caring for infants, experienced a lack of privacy, insufficient lactation support and unsafe shelter environments. In some cases, infants became dehydrated due to delayed or absent breastfeeding assistance. Mothers frequently prioritised their children’s needs over their own, leading to exhaustion, dehydration and concerns about insufficient milk supply. Emergency responders were often untrained in infant feeding needs, and evacuation and recovery services largely overlooked infants and their caregivers. The study highlighted the need for targeted preparedness, including the provision of dedicated spaces in evacuation centres and practical guidance for families with very young children(Reference Gribble, Peterson and George35).

The United States provides further examples of structural challenges. During Hurricane Katrina in 2005, women living in the disaster-affected regions were found to be at greater risk of not breastfeeding or of breastfeeding for shorter durations compared to national averages(Reference Callaghan, Rasmussen and Jamieson33). Factors contributing to early weaning from the breast included breakdown of health services, lack of shelter and lack of support for breastfeeding and widespread distribution of CMF. More recently, a review by Russell et al. identified persistent systemic gaps across ten US-based disasters(Reference Russell, Haushalter and Rhoads30). Breastfeeding families were frequently overlooked in emergency plans; shelters lacked lactation supplies and private spaces, and healthcare professionals were not trained to support breastfeeding. The review also highlighted problems such as poor communication, unsolicited CMF donations and lack of continuity in care.

These examples from Canada(Reference DeYoung, Suh and Thomas32), Italy(Reference Giusti, Marchetti and Zambri34), Australia(Reference Gribble, Peterson and George35) and the United States(Reference Callaghan, Rasmussen and Jamieson33) show that well-resourced settings were often unprepared to meet the feeding needs of infants during emergencies, not due to a lack of infrastructure but because of fragmented planning, untrained personnel and weak integration of Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) into emergency response systems.

The COVID-19 pandemic further exposed these weaknesses in high-income settings. Lockdowns, early hospital discharge and the reduction of in-person postnatal services disrupted breastfeeding support at a global scale(Reference Gribble, Tomori and Brodribb6,Reference O’Sullivan and Kennedy31,Reference Brown and Shenker36) . Many mothers reported limited access to skilled lactation care, particularly in the early weeks postpartum. Although some reported continuing breastfeeding for longer than originally intended due to concerns about CMF availability and the improved immunity provided by breastfeeding, others stopped breastfeeding early or struggled due to lack of assistance and heightened stress(Reference Gribble, Tomori and Brodribb6,Reference Bartick, Reinhold and Young10) . Healthcare professionals and lay supporters offered assistance via virtual platforms but could not replace face-to-face help with latching, positioning or managing feeding problems. These disruptions highlighted the absence of coordinated breastfeeding protocols in pandemic preparedness frameworks and reinforced the need to include infant feeding support in future public health emergencies.

The experience of Ukrainian mothers and infants during the current conflict offers critical insight into IYCF-E challenges that intersect with HIC responses. Although Ukraine is not classified as a HIC, its inclusion in this review is justified due to the nature of the humanitarian response, particularly in host countries such as Poland. As displaced families crossed into neighbouring European Union states, many of the IYCF-related decisions, resources and coordination mechanisms were shaped by the policies and capacities of high-income host nations. According to Summers and Bilukha(Reference Summers and Bilukha37), during the 2014 conflict, exclusive breastfeeding rates among internally displaced mothers were low, with stress, poor education and limited support contributing to early breastfeeding cessation. More recent evidence from the ongoing war highlights persistent structural problems. Iellamo et al. and Shlemkevych et al. Both reported that mothers often faced pressure from healthcare staff to use CMF, sometimes immediately after birth(Reference Iellamo, Wong and Bilukha38,Reference Shlemkevych, Bilukha and Lunder39) . Access to lactation counselling was minimal, and CMF donations were frequently accepted and distributed, even when not medically necessary(Reference Iellamo, Wong and Bilukha38). These factors, combined with psychological stress and uncertainty, weakened confidence in breastfeeding and made it difficult for mothers to continue, particularly in displaced or conflict-affected areas.

Among refugees in Poland, experiences were more varied. While some mothers encountered language barriers and received unclear or conflicting advice, others were offered practical support such as lactation counselling, breastfeeding education and assistance with colostrum collection(Reference Iellamo, Wong and Bilukha38). Access to these services depended on the specific facility and available personnel. Across both contexts, mothers expressed a need for clearer infant feeding guidance, more consistent professional support and improved oversight of CMF provision.

In a separate study, Babiszewska-Aksamit et al. reported that over half of refugee mothers in Poland received lactation counselling, and most found it helpful in meeting their breastfeeding goals(Reference Babiszewska-Aksamit, Gawrońska and Sobczyk-Krupiarz40). Support included translated materials and professional guidance across multiple settings. However, Chrzan-Dętkoś and Murawska noted that language barriers and limited psychological care remained important challenges(Reference Chrzan-Dętkoś and Murawska41). Although Poland’s response was not uniform and had several limitations, its partial integration of breastfeeding support services, particularly within some maternity and public health settings, illustrates the potential for targeted and coordinated interventions to help sustain breastfeeding during displacement and crisis.

Japan provides a contrasting example of systemic preparedness. Following the 2011 Fukushima earthquake and nuclear disaster, Kyozuka et al. reported that breastfeeding rates and infant growth outcomes remained stable across both affected and unaffected regions(Reference Kyozuka, Yasuda and Kawamura42). This was attributed to Japan’s investment in public health preparedness, including the integration of maternal and infant care into emergency protocols. Although some mothers reported opting for CMF due to fear of radiation, overall health services provided continuity of care and protected breastfeeding through consistent guidance and institutional coordination(Reference Kyozuka, Yasuda and Kawamura42).

These case studies illustrate that breastfeeding is highly vulnerable and is easily disrupted when support systems are absent or fragmented. Countries with stronger preparedness measures and integrated breastfeeding support, such as Japan and to some extent Poland, have demonstrated greater resilience. By contrast, countries where emergency preparedness measures do not include breastfeeding as a priority experienced greater disruption.

Commercial milk formula in emergencies

When infants are not breastfed, global guidance states that CMF should only be used under strict criteria. These include assessment of infant feeding needs by appropriate trained personnel, procurement through government or health authority channels and provision of full support packages that include safe water, sterilisation equipment and guidance for safe preparation. Unregulated donations of CMF, bottles, teats or feeding equipment are strongly discouraged, as these can undermine breastfeeding efforts, introduce risks of contamination and lead to inappropriate use in non-target populations(2,3) . CMF usage during emergencies presents unique risks that require careful management, particularly where clean water, sterilisation and consistent supply chains cannot be guaranteed. Across a range of emergency settings, inappropriate CMF distribution has compromised infant health, displaced breastfeeding and exposed significant failures in emergency planning.

Evidence from high-income settings including Canada(Reference DeYoung, Suh and Thomas32), Italy(Reference Giusti, Marchetti and Zambri34), Australia(Reference Gribble, Peterson and George35) and the United States(Reference Russell, Haushalter and Rhoads30,Reference Callaghan, Rasmussen and Jamieson33) , consistently shows that unregulated donations of CMF are common during emergencies and are often poorly managed. Such distributions frequently undermine breastfeeding, contribute to confusion among caregivers and can introduce serious health risks when formula is used without access to clean water, sanitation or appropriate preparation equipment. While HICs are rarely the focus of rigorous impact studies, evidence from low- and middle-income settings illustrates the potential harm. In Indonesia, following the 2006 Yogyakarta earthquake, 80% of households with young children received donated infant formula, most of it unsolicited and unregulated(Reference Hipgrave, Assefa and Winoto43). As a result, formula use among infants under six months increased from 32% before the disaster to 43% within weeks. Critically, the study found that diarrhoea incidence was significantly higher among children in households that received donated formula, with a relative risk of 2.12 (95% CI: 1.34–3.35) and a five-fold increase in diarrhoea rates among toddlers compared to pre-crisis levels.

In the United States, Hurricane Katrina highlighted the vulnerability of formula-fed infants during disasters. Women in affected areas were more likely to stop breastfeeding early and turn to CMF, even in unsafe conditions(Reference Callaghan, Rasmussen and Jamieson33).

Russell et al. reviewed multiple US disaster responders and identified recurring issues, including unsolicited CMF donations, inadequate staff training, lack of needs assessment and the absence of safe preparation infrastructure(Reference Russell, Haushalter and Rhoads30). CMF was often distributed as general aid rather than targeted medical support, increasing the risk of unsafe feeding.

Similar patterns were observed elsewhere. In Canada, evacuees during the Fort McMurray wildfire reported receiving CMF without any instruction for its safe preparation(Reference DeYoung, Suh and Thomas32). In Italy, post-earthquake responses included mass distributions of CMF, often incompatible with local feeding practices(Reference Giusti, Marchetti and Zambri34). In Australia, unsafe feeding practices during the 2019–2020 bushfires led to at least one infant hospitalisation, as shared shelter spaces lacked basic facilities for safe CMF preparation(Reference Gribble, Peterson and George35).

The COVID-19 pandemic further exposed CMF-related vulnerabilities. In Ireland, families reported difficulty accessing CMF due to real or perceived shortages, leading to significant anxiety and concern(Reference O’Sullivan and Kennedy31). In the United States, one in three formula-feeding families reported unsafe practices, including dilution, leftover use or substitution with cow’s milk or juice(Reference Marino, Meraz and Dhaliwal44). In the UK and in Canada, some parents adjusted feeding methods based on CMF supply concerns or lack of in-person breastfeeding support(Reference Vazquez-Vazquez, Dib and Rougeaux45,Reference Fry, Levin and Kholina46) . These examples underscore the need for national emergency preparedness plans to secure CMF supply chains, provide clear caregiver guidance and reduce panic-driven adaptation during crises.

Disparities in CMF distribution are also evident in conflict settings. Ukraine’s experience during both the 2013 conflict and the ongoing war has further shown how CMF usage can become widespread in the absence of oversight. CMF was distributed broadly, often from humanitarian donations, with little attempt to assess need or support safe use(Reference Summers and Bilukha37–Reference Shlemkevych, Bilukha and Lunder39). In contrast, Poland’s Ukrainian refugee response was more aligned with international guidance. CMF was provided only when breastfeeding was not possible, and mothers received lactation counselling and feeding assessments(Reference Babiszewska-Aksamit, Gawrońska and Sobczyk-Krupiarz40,Reference Chrzan-Dętkoś and Murawska41) . These differences reflect how aid delivery models, decentralised (local and international agencies) vs. government-led can significantly influence IYCF-E outcomes.

Japan offers an example of coordinated planning. Following the 2011 Fukushima disaster, some families used CMF due to radiation fears, but the government maintained consistent public messaging and did not facilitate widespread CMF distribution. This helped sustain breastfeeding rates and protect infant health(Reference Kyozuka, Yasuda and Kawamura42).

Across these settings, a recurring pattern emerged. Where CMF was distributed without needs assessment, oversight or appropriate support, it frequently led to unsafe feeding practices, increased dependency and the disruption of breastfeeding. In contrast, countries that implemented clear protocols and provided targeted support such as Japan and Poland, demonstrated greater resilience in protecting infant feeding. These findings highlight the urgent need for comprehensive CMF preparedness strategies that include restrictions on unsolicited donations, adequate staff training, coordinated leadership and proactive public health communication.

Complementary feeding in emergencies

The introduction of complementary foods in emergencies is necessary once infants reach six months of age. While global IYCF-E guidance emphasises the protection and promotion of breastfeeding, the complementary feeding period has received comparatively less attention, despite its importance for growth, development and long-term nutritional resilience(Reference Abla and McGrath47). In emergency contexts, disruptions to food systems and a lack of nutrient-rich foods can increase the risk of malnutrition, micronutrient deficiencies and growth faltering in children aged 6 to 23 months(48).

Commercially available CACFs may serve as a temporary nutritional solution when home-prepared meals are not feasible. However, their use must be carefully managed. Unregulated or inappropriate distribution of these products can lead to the early displacement of breastfeeding, exposure to nutritionally poor products and longer-term dependency on ultra-processed foods(48,49) . For example, families living in emergency accommodation in Ireland have reported significant difficulty providing suitable solid foods to young children due to limited cooking facilities and poor access to appropriate products(Reference Share and Hennessy50).

Donations of CACFs should not be sought or accepted in emergencies. Supplies should be procured based on assessed nutritional need and only when age-appropriate, safe and culturally suitable options are available(2). Risks associated with donated CACFs include failure to meet nutritional and safety standards, inadequate labelling or preparation instructions and non-compliance with the WHO Code and the 2016 Guidance on Ending the Inappropriate Promotion of Foods for Infants and Young Children(49). Donated products may also be culturally inappropriate, displace local foods and undermine recommended IYCF practices(2).

Evidence from multiple emergencies has shown that complementary feeding is frequently compromised by inappropriate donations and a lack of caregiver support. During the 2015 European refugee crisis, more than one million refugees and migrants arrived in Europe. Along their migration routes and in temporary camps, various humanitarian actors distributed CACFs, including processed products marketed for children aged 6–23 months(Reference Theurich and Grote12). However, many of these products were unsolicited, poorly targeted or inappropriate for the feeding context. Distributions often diverged from international guidance on IYCF-E, and the inconsistent application of ad hoc complementary feeding guidance further complicated efforts to ensure safe and culturally appropriate feeding. These findings highlight the need for clearer technical specifications and stronger coordination mechanisms when CACFs are considered for emergency use.

During the internal displacement crisis in eastern Ukraine following the 2014 conflict, Summers and Bilukha reported that 18% of infants under six months had already been introduced to solid foods(Reference Summers and Bilukha37). Furthermore, commercial products were more likely to be introduced than homemade alternatives to this age group, suggesting that availability shaped feeding behaviours in displaced households.

Inappropriate use of CACFs may also have long-term dietary consequences. The UNICEF (2020) report on ultra-processed foods notes that many commercial baby foods are high in sugar and salt, lack dietary diversity and contribute to the development of sweet taste preferences in early life. While such products may temporarily meet energy needs during acute emergencies, their continued use without appropriate guidance may contribute to poor dietary quality, micronutrient deficiencies and increased risk of overweight and obesity in the long term.

These examples highlight the urgent need for a coordinated, evidence-based approach to complementary feeding in emergencies. Rather than accepting donated foods, it is instead preferable that procurement should follow established protocols, ensuring that products are nutritionally adequate, safe and tailored to age and context. Caregivers must be supported with culturally relevant guidance, appropriate feeding environments and practical tools for preparing safe meals. Complementary feeding in emergencies is not simply a matter of planning but a core element of public health protection and caregiver empowerment.

Global guidance and preparedness for IYCF-E

A robust framework exists to guide IYCF-E, yet the uptake and application of this guidance remains inconsistent, particularly in HICs. Key tools include the Operational Guidance on Infant and Young Child Feeding in Emergencies(2), the International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes and associated World Health Assembly resolutions(18,20,21) , the Sphere Handbook(19) and WHO/UNICEF technical guidance on infant feeding during the COVID-19 pandemic(51). Together, these documents provide comprehensive recommendations on breastfeeding protection, management of CMF, complementary feeding and coordinated response mechanisms.

However, as demonstrated throughout this review, these global standards are often not reflected in national emergency preparedness systems. In Ireland, while researchers(28) have developed a cross-border IYCF-E preparedness plan, it remains outside statutory systems and lacks operational integration. In Australia, although the Australian Breastfeeding Association and other organisations reference IYCF-E principles, these have not been fully adopted into formal emergency protocols or legislation(Reference Gribble and Palmquist23). Similarly, in New Zealand, while guidance on infant feeding in emergencies is available, it remains advisory and has not been implemented at scale or through binding regulation(52). Of note in Scotland, there is a national lead responsible for coordinating infant feeding in emergencies. However, there is no IYCF-E policy(53).

Common barriers to the integration of IYCF-E standards into formal emergency management frameworks include fragmented emergency governance, unclear leadership responsibilities, limited intersectoral coordination and a lack of legal frameworks to enforce compliance(Reference Bartick, Tomori and Gribble29,Reference Gribble, Peterson and Brown54) . Few HICs have assigned institutional responsibility for IYCF-E, and most have not embedded infant feeding within disaster risk reduction, civil contingency or pandemic preparedness strategies(Reference Gawrońska, Sinkiewicz-Darol and Wesołowska24,28,Reference O’Sullivan and Kennedy31) . Existing policies are often general in nature and lack operational detail, leading to poor coordination during real-world crises. As illustrated by the COVID-19 pandemic, wildfires in Australia and hurricane responses in North America, these gaps result in preventable breastfeeding disruption, unsafe CMF use and inappropriate complementary feeding practices(Reference DeYoung, Suh and Thomas32,Reference Gribble, Peterson and George35,Reference Marino, Meraz and Dhaliwal44) . Bridging this implementation gap requires more than technical guidance. It demands legally supported national plans, integrated inter-agency coordination and sustained investment in system-wide readiness. In the absence of these core enablers, global IYCF-E recommendations are unlikely to translate into consistent practice. The next section synthesises these findings and identifies policy priorities for improving infant feeding resilience during emergencies in high-income contexts.

Policy implications for IYCF-E

Climate change is expected to increase the frequency, severity and complexity of emergencies in HICs, including heatwaves, floods, wildfires and disruptions to critical infrastructure(4). These evolving risks underscore the need to strengthen infant and young child feeding preparedness as part of broader public health resilience and emergency planning.

Analysis of case studies from Ireland(28,Reference O’Sullivan and Kennedy31) , the United Kingdom(Reference Brown and Shenker36), the United States(Reference Bartick, Reinhold and Young10,Reference Russell, Haushalter and Rhoads30) , Canada(Reference DeYoung, Suh and Thomas32), Australia(Reference Gribble, Peterson and George35) and Poland(Reference Babiszewska-Aksamit, Gawrońska and Sobczyk-Krupiarz40) reveals a set of recurring challenges. These include insufficient breastfeeding support, unregulated distribution of CMF and CACFs, inadequate training for frontline responders and weak implementation of international IYCF-E guidance.

Breastfeeding, while recognised as a protective feeding practice in emergencies, was often compromised due to a lack of skilled personnel, absence of dedicated mother–infant spaces and breakdowns in continuity of care. These challenges persisted even in countries with centralised healthcare systems and during emergencies where risks to infant nutrition were widely acknowledged, such as the COVID-19 pandemic(Reference Gribble, Tomori and Brodribb6,Reference O’Sullivan and Kennedy31,Reference Brown and Shenker36) . In Japan, for example, investment in IYCF-E planning contributed to more protective approaches during the Fukushima disaster(Reference Kyozuka, Yasuda and Kawamura42). However, during COVID-19, Japan experienced reduced compliance with WHO breastfeeding recommendations, especially regarding rooming-in for COVID-19-positive mothers. Despite these disruptions, mothers who received all five key support interventions were significantly more likely to exclusively breastfeed, underscoring the protective role of structured support(Reference Nanishi, Myoga and Yamamoto55). This suggests that while Japan faced service gaps, prior preparedness and partial adherence to guidance helped buffer the impact. Similarly, Poland demonstrated partial success by coordinating breastfeeding support for Ukrainian refugees, although this was limited by gaps in psychological care and system integration(Reference Iellamo, Wong and Bilukha38,Reference Chrzan-Dętkoś and Murawska41) .

The management of CMF during emergencies was particularly inconsistent. Many responses involved the widespread distribution of formula without assessment of need, adequate preparation facilities or support for caregivers. These practices often undermined breastfeeding and exposed infants to avoidable health risks. Evidence from Ukraine(Reference Iellamo, Wong and Bilukha38,Reference Shlemkevych, Bilukha and Lunder39) and the United States(Reference Bartick, Reinhold and Young10,Reference Russell, Haushalter and Rhoads30) confirms that without clear leadership, operational guidance and enforcement mechanisms, policies designed to protect infant feeding are frequently bypassed. This reflects a broader issue: the presence of international standards(2) alone does not ensure implementation. National systems must assign clear responsibilities, enforce regulations and provide training to emergency responders across sectors.

The distribution and use of commercially available CACFs during emergencies present similar risks to those associated with CMF but receive even less policy attention. CACFs are often introduced too early, without caregiver education or in forms that are nutritionally inadequate or culturally inappropriate(13,48,49) . In several emergencies, complementary food products have been distributed despite being expired or close to expiry, inadequately labelled or of limited nutritional value(2,49) . Theurich and Grote documented widespread distribution of CACFs during the 2015 European refugee crisis, often without proper targeting or adherence to international guidance(Reference Theurich and Grote12). Despite the existence of WHO guidance on the inappropriate promotion of foods for infants and young children(49), most HICs lack clear protocols for CACF procurement, distribution and oversight during emergencies(2,13) . There is also little training for responders on how to assess the appropriateness of complementary foods or to support caregivers in safe preparation and feeding practices(2). The increasing prevalence of ultra-processed baby foods, combined with weak regulation and limited donation controls, raises concerns not only for immediate nutritional adequacy but also for long-term dietary health(48). Addressing these risks requires specific policy measures, including national guidance on CACFs in emergencies, enforcement of labelling and quality standards and integration of complementary feeding into broader IYCF-E preparedness planning.

Collectively, these findings point to a clear policy gap. While technical guidance on IYCF-E exists, few HICs have adapted these tools to their national systems. IYCF-E is still largely treated as a specialised concern, often limited to low-income or conflict settings. As a result, infant feeding is frequently absent from broader disaster risk reduction, public health resilience and family preparedness frameworks. For example, the European Union’s March 2025 launch of a public 3-day emergency survival kit included no guidance or supplies related to infant feeding, despite targeting household readiness across member states(56). This omission highlights how the specific needs of infants and young children remain a low priority in mainstream emergency planning.

Some countries have made early efforts to address these issues. In Ireland, researchers have developed an all-island IYCF-E preparedness plan to guide coordination, surge planning and systems readiness(28). While this document outlines how the Irish and Northern Irish governments might embed infant feeding into emergency systems, it has not yet been formally adopted. Without legal mandates, sustainable funding and operational mechanisms, such frameworks remain aspirational rather than actionable. Similar limitations are observed in existing guidance from bodies such as the United States Centre for Disease Control and Prevention(26) and the Australian Breastfeeding Association(27), both of which offer practical resources for responders but lack the statutory authority or regulatory mandate to ensure consistent application across jurisdictions.

The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine has issued a comprehensive position statement calling for breastfeeding to be explicitly integrated into all emergency preparedness plans(Reference Bartick, Tomori and Gribble29). The statement emphasises the need for breastfeeding specialists to be involved in both the development and delivery of emergency protocols. It recommends prioritising caregivers of infants in relief distribution, ensuring private and culturally sensitive spaces for breastfeeding and maintaining mother–infant proximity wherever possible. The statement also outlines conditions for the controlled provision of CMF and explicitly discourages the donation of CMF, bottles, teats and pumps during emergencies. These recommendations reinforce the need for operational frameworks that move beyond informal support and guidance and into structured, accountable planning.

To address these shortcomings, IYCF-E must be embedded into national and sub-national emergency preparedness frameworks as a core public health priority. This includes developing operational protocols for breastfeeding support in all emergency settings, regulating CMF and CACF procurement and distribution and deploying trained IYCF personnel as part of emergency response teams. Feeding support must be available in shelters and healthcare facilities, and systems should ensure families can access safe, private and culturally appropriate feeding environments. Legal protections should be established to uphold breastfeeding rights, regulate donations and mandate the inclusion of IYCF-E in emergency planning and funding mechanisms.

Community-based resources such as community maternal and child health services, breastfeeding support groups, donor milk banks and early years health networks already exist in many high-income settings. With appropriate policy support, training and coordination, these assets could play a significant role in delivering consistent and context-specific support during emergencies. Recent crises have created momentum and awareness around the nutritional needs of young children in emergencies. As climate change continues to drive more frequent and severe emergencies in HICs, the risks to infant feeding will only intensify. IYCF-E must be recognised as a core component of public health resilience and statutory emergency planning. This must now be matched by structural action to ensure that infant feeding is protected not only by guidance but by operational readiness and political will.

Recommendations

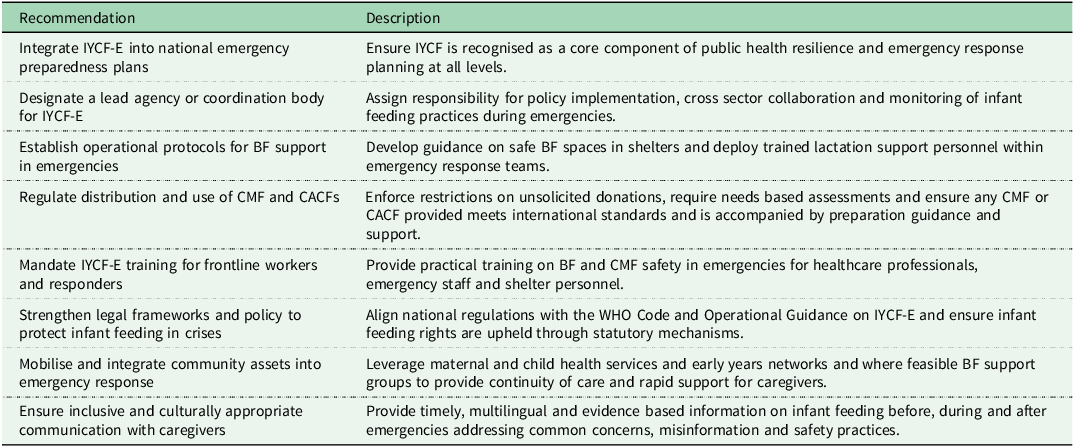

To strengthen nutritional resilience for infants and young children during emergencies, HICs should take forward the key actions outlined in Table 1, which summarises priority measures relating to IYCF E planning, coordination, service provision and policy.

Table 1. Recommendations to strengthen nutritional resilience for infants and young children during emergencies in High income countries

BF, breastfeeding; CACF, commercially available complementary food; CMF, commercial milk formula; HIC, high income country; IYCF, infant and young child feeding; IYCF-E, infant and young child feeding in emergencies; WHO Code, International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes.

By acting on these recommendations, countries can protect the health and wellbeing of infants and young children during emergencies, reduce avoidable risks and ensure that families are not left to navigate feeding challenges alone in times of crisis.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This project was funded by the North–South Research Programme (NSRP), a collaborative initiative funded by the Government of Ireland through the Shared Island Fund.

Competing Interests

No conflict of interest to be declared by either author.