Background

With widespread population ageing, many Western countries can expect a substantial growth in demand for labour-intensive long-term care (LTC) services (OECD 2021). At the same time, older segments of the population are growing increasingly diverse as immigrants ‘age in place’ (Rechel et al. Reference Rechel, Mladovsky, Ingleby, Mackenbach and McKee2013). Despite immigrants’ access to health care being a crucial element of integration and a fundamental human right, there is limited knowledge on the utilization of LTC services among immigrants (Bolster-Foucault et al. Reference Bolster-Foucault, Vedel, Busa, Hacker, Sourial and Quesnel-Vallée2024; Nielsen et al. Reference Nielsen, Krasnik and Rosano2009).

While the share of the foreign-born population in Norway is higher than the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development average (OECD 2022), large-scale immigration to Norway is a relatively recent phenomenon and the number of immigrants falling into the older age categories remains low. However, according to the official population projections, the number of immigrants over the age of 80 will increase fourfold within 20 years and more than tenfold by 2060 (Thomas and Tømmerås Reference Thomas and Tømmerås2024). This represents an increase from around 13,000 today, to over 145,000 by 2060 (Thomas and Tømmerås Reference Thomas and Tømmerås2024).

Generally speaking, immigrants in Western countries, including Norway, have lower average risks of mortality than their native-born peers (Wallace et al. Reference Wallace, Thomas, Aburto, Pallesen, Mortensen, Syse and Drefahl2022). This general health advantage has been linked to the so-called healthy immigrant effect, where immigrants are thought to be positively selected on health (and health-conducive socio-economic characteristics) relative to non-migrants in the sending country, while requirements linked to immigrant admission policies at the destination may add a further layer of positive selection (Elshahat et al. Reference Elshahat, Moffat and Newbold2022). Negative selection into return migration might also contribute to apparent health advantages among immigrants relative to the native-born population, particularly if less healthy and less economically advantaged immigrants are those that are more likely to return to their country of origin (a process described as the ‘salmon bias’) (Abraído-Lanza et al. Reference Abraído-Lanza, Dohrenwend, Ng-Mak and Turner1999). However, the existence of a salmon bias effect has been challenged by recent empirical results from Sweden, with lower risks of emigration observed among immigrants with co-morbidities (low, moderate and high) relative to those without co-morbidities (Dunlavy et al. Reference Dunlavy, Cederström, Katikireddi, Rostila and Juárez2022).

Of particular relevance to a focus on older immigrants, who typically have long durations of residence, is evidence that immigrant health advantages decline with time spent in the destination country. In Norway, for instance, studies ranging from hospital admission rates (Elstad Reference Elstad2016) to mortality risks (Syse et al. Reference Syse, Dzamarija, Kumar and Diaz2018) observe a general trend of convergence towards the native-born population as immigrants’ durations of stay increase. For some immigrant groups, health can be significantly worse than the national average regardless of duration of residence, and especially with long duration of residence (Kjøllesdal et al. Reference Kjøllesdal, Gerwing and Indseth2023). A process of unhealthful acculturation, wherein immigrants adopt risky/unhealthy behaviours and lifestyles more prevalent in the destination context, is one perspective as to why immigrants experience health deterioration over time. For instance, meta-analyses of health risk behaviours point to the importance of specific origin and destination contexts and differences according to the behaviours studied; however, several North American and European studies do at least highlight generally increased risks of smoking among immigrant populations with longer durations of residence (Juárez et al. Reference Juárez, Honkaniemi, Gustafsson, Rostila and Berg2022). An alternative perspective points to (cumulative) individual, social and system-based stressors as having deleterious effects on immigrants’ health over time. Disadvantaged socio-economic status, language difficulties, discrimination and difficulties navigating housing, labour market and health systems have been noted as examples of stressors that can accumulate over time with negative implications for immigrants’ health trajectories (Elshahat et al. Reference Elshahat, Moffat and Newbold2022). It has also been noted that experiences of such stressors may themselves underlie observed increases in health risk behaviours among immigrants over time. For example, stressors may engender the uptake of risky/unhealthy behaviours, while limited material resources can restrict access to certain types of physical activity and diet that are associated with healthier lifestyles (Juárez et al. Reference Juárez, Honkaniemi, Gustafsson, Rostila and Berg2022). The typical associations between older immigrants’ durations of stay, health and health-care utilization are thus likely to be moderated by a wide range of social determinants (Marmot Reference Marmot2005), including socio-economic status and education, health literacy and practices, access to care, and lived or perceived discrimination (Diaz et al. Reference Diaz, Kumar, Gimeno‐Feliu, Calderón‐Larrañaga, Poblador‐Pou and Prados‐Torres2015; Edberg et al. Reference Edberg, Cleary and Vyas2011).

A further important source of heterogeneity relates to immigrants’ country of origin, which is known to be closely associated with initial reasons for immigration. Notably, over the period 1990–2023, the large majority (79 per cent) of immigrations from combined African and Asian origins were linked to refugee and family reunification reasons, with just 7 per cent of immigrations from Africa and Asia undertaken for labour reasons (Statistics Norway 2024a). Refugees are often exempt from the typical health benefits we associate with immigrants upon arrival, and they may even experience health deteriorations because of circumstances before or during the transfer (Syse et al. Reference Syse, Dzamarija, Kumar and Diaz2018). Non-Western immigrants also have typically lower levels of educational attainment and weaker labour-market attachment and earnings than Western-origin immigrants in Norway (Bratsberg et al. Reference Bratsberg, Raaum and Røed2018). While this may point to relatively poor health outcomes, refugees are invited to a general health assessment upon arrival in Norway, which could promote a higher uptake of formal health and care services and follow-up when such needs exist (Haj-Younes et al. Reference Haj-Younes, Strømme, Igland, Abildsnes, Kumar, Hasha and Diaz2021).

Among older age immigrants, country of origin has also been used to proxy cultural distance between origin and destination contexts and to recognize differences in sensitivities to and experiences of health-care systems, as well as heterogeneities in the role and expectations of family in care-giving (Hestevik et al. Reference Hestevik, Jardim and Hval2022). Independent of any underlying differences in care needs, such factors could bear relevance for disparities in LTC utilization by immigrant background. In a small-scale study of municipal care among older immigrants in Sweden, Hovde et al. (Reference Hovde, Hallberg and Edberg2008a) noted how non-Nordic immigrants found difficulties in access to culturally congruent care and in knowledge and interactions with health-care systems, while health-care personnel appeared to have less knowledge about non-Nordic immigrant patients than their Nordic-born peers. Family members of non-Nordic immigrants were also found to play a more significant role in health-care provision, where they were more often registered as carers (Hovde et al. Reference Hovde, Hallberg and Edberg2008b). A more recent qualitative study of older Pakistani women living in Oslo, Norway, documented a range of issues that were reported to have influenced preferences, experiences and negotiations between formal and informal care, which ranged from perceptions about the quality of formal care and fears of being left behind in residential care homes, to concerns about mixing with other cultures and genders and feelings of disloyalty and shame in relation to being cared for by outsiders (Arora et al. Reference Arora, Straiton, Bergland, Rechel and Debesay2020).

From this perspective, where the presence of family members (e.g. adult children and partners) may indicate access to informal familial support systems, we might expect a higher likelihood that family care substitutes for formal health and social care among older immigrants, and perhaps particularly for those from more culturally distant origins. Likewise, those who do transition into LTC might be a select immigrant subgroup that, for instance, utilizes LTC only when the situation is severe. With that said, an increasing openness to home health-care services among older immigrants with non-European backgrounds has been noted as another form of adaptation, wherein professional care provision might play a supportive rather than a substitutive role (Horn Reference Horn, Torres and Hunter2023).

More generally, previous studies find the presence of partners (and parenthood) to be positively associated with health and longevity (Kravdal et al. Reference Kravdal, Grundy, Lyngstad and Wiik2012; Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Hoherz, Addo, Lappegård, Evans, Sassler and Styrc2018), while unpartnered and/or childless older people have been shown to have higher rates of LTC utilization than those with partners and/or children (Grundy and Jitlal Reference Grundy and Jitlal2007; Syse et al. Reference Syse, Artamonova, Thomas and Veenstra2022; van Der Pers et al. Reference van Der Pers, Kibele and Mulder2015). There is very little research on the role of family in influencing the intensity of LTC, but it has been suggested that close family members could play an important role in helping to support older relatives’ navigation, interaction and follow-up in health-care systems (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Dixon, Trevena, Nutbeam and McCaffery2009; Syse et al. Reference Syse, Artamonova, Thomas and Veenstra2022).

In the Norwegian context, the initial evidence suggests that immigrants are less likely than natives to use LTC services, and if they are awarded services, they tend to receive fewer hours of care (Dzamarija Reference Dzamarija2022). However, these prior findings are descriptive in nature and do not account for socio-demographic differences between immigrants and natives, or potential variations across immigrant subgroups. They are, however, in line with existing research on possible under-use (Hansen Reference Hansen2014), especially among those with short durations of residence (Emami and Ekman Reference Emami and Ekman1998; Qureshi et al. Reference Qureshi, Schumacher, Talarico, Lapenskie, Tanuseputro, Scott and Hsu2021). Against this backdrop, academic and policy reports have considered whether eligible immigrants might under-utilize LTC services owing to potential discrimination in health system evaluations, differing levels of knowledge of immigrant groups among health-care professionals, differences in preferences or a lack of health literacy when navigating complex care systems (Hestevik et al. Reference Hestevik, Jardim and Hval2022; Khatri and Assefa Reference Khatri and Assefa2022).

The Norwegian setting

Norway sits within the Nordic tradition of extensive and universal welfare provision (Esping‐Andersen Reference Esping‐Andersen1999), providing highly subsidized health and care services (either home-based or institutionalized) to all residents regardless of age (Molven and Ferkis Reference Molven and Ferkis2011). The services are predominantly publicly financed through general taxation and rationed according to needs (Molven and Ferkis Reference Molven and Ferkis2011); public sources account for 85 per cent of total health expenditure (Debesay et al. Reference Debesay, Arora, Bergland, Borch, Harsløf, Klepp and Laitala2019). Care services are administered at the municipal level. To mitigate geographical disparities in service provision, statutory regulations require all municipalities to adhere to predefined minimum standards of welfare services, including primary health and care services. With that said, residents are not entitled to specific services, and municipalities must decide on the type and scope of the service that is warranted to meet the corresponding individual needs of residents (Molven and Ferkis Reference Molven and Ferkis2011). Previous variance component analyses have found very little variation in uptake of LTC at the municipality level (Syse et al. Reference Syse, Artamonova, Thomas and Veenstra2021).

Home health care (HHC), which includes home nursing and other forms of health care (e.g. physiotherapy, occupational therapy and (re)habilitation services) received in the patient’s home, is the most commonly awarded LTC service among older individuals in Western countries (OECD 2021) and is the preferred form of care, when appropriate, in Norway (Ministry of Health and Care Services 2011). More than 80 per cent of all LTC users in Norway depend on HHC (Statistics Norway 2023). Within the Norwegian health-care system, HHC is defined as an LTC service and, according to the data analysed in this article, around 90–92 per cent of persons receiving HHC continued to receive it in the following year. An additional attractiveness about the analysis of HHC is that it enables us to assess variations in both transitions into care and intensity of care, with the latter not possible in analyses of institutionalized care. Thus, via a full-population longitudinal study, we examine patterns in HHC uptake and intensity among immigrants and natives in Norway, adjusting for differences in immigrant background and socio-demographic characteristics.

Norway’s highly universalistic service provision, coupled with its defamilialized policy environment (Albertini and Pavolini Reference Albertini and Pavolini2017), should allow individuals access to formal care relatively independently from their own economic or familial resources. Still, recent research indicates fewer transitions to institutionalized LTC among older individuals with resourceful partners and adult children, in contrast to those without partners or children, or those with partners and children with less advantageous characteristics (Syse et al. Reference Syse, Artamonova, Thomas and Veenstra2022). To our knowledge, no prior research has been performed to determine how patterns in HHC uptake and intensities might vary by immigrant background characteristics. Given the limited body of existing research, we pose three broad research questions (RQs):

RQ1: Does the likelihood of transitioning into HHC differ by immigrant background characteristics (immigrants versus natives; country group of origin; and length of stay in Norway) and, if so, in what ways?

RQ2: For those who are in receipt of HHC, are there differences in the intensity of care by immigrant background characteristics?

RQ3: Do the patterns associated with the effect of socio-demographic characteristics (e.g. the presence of family and individual socio-economic resources) on HHC utilization differ according to immigrant background characteristics?

Data and methods

Data

We use population register data from Statistics Norway, covering all individuals aged 60 or older from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2016 (5.7 million person-years, average follow-up time 4.7 years, N = 1,220,091).Footnote 1 Structured as an annual panel, the data include dates of birth, death, immigration and emigration, as well as sex, immigrants’ country group of origin, education, income, living situation, parental status and whether the municipality is highly urbanized or not. Time-invariant and time-varying socio-demographic data were linked to the pseudonymized municipal care use registry (IPLOS) after ethical review by the Norwegian Board of Medical Ethics (#2014/1708), by means of a unique personal ID number assigned to all residents in Norway. The IPLOS registry contains individual-level information on persons’ most frequently used services including HHC, practical assistance (PA) and LTC, ranging from in-home safety alarms to full-time institutionalized care. All data handling has been done on an anonymized file and undertaken in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and national ethics requirements.

While this dataset provides the necessary detail on immigrant background and socio-demographic characteristics, it does not include objective measures of health and thus poses a challenge for discerning the extent to which variations in HHC transitions are owing to underlying differences in health and care needs rather than preferences/barriers to care access. It should be noted, however, that the use of administrative register data to quantify prior health status can carry complexities for interpretations of HHC utilization as we observe morbidities only for those who have actively engaged with the health-care system, and we cannot determine if non-users are healthy or not (Diaz and Kumar Reference Diaz and Kumar2014). Still, online supplemental material Appendix A provides an evaluation of the extent to which variations in HHC transitions by status as an immigrant versus native and country group of origin are influenced by the inclusion of an objective measure of health. This sensitivity analysis draws on an alternative dataset, for the period 2018–2022, which contains information on hospitalizations but far more limited information on immigrant and socio-demographic characteristics. The results suggest that the inclusion of an objective measure of health status has little influence on the size and direction of the association between HHC transitions and the two immigrant background variables.

Outcome variables

The first outcome we study is binary in nature (0 = not using HHC, 1 = using HHC) and is used to assess the risk of a first transition into HHC. Home nursing comprises the vast majority of HHC provided to older adults, and commonly includes follow-ups on medication and medical procedures, such as wound care or other services requiring observation or intervention by a registered nurse.Footnote 2 Our second outcome of interest is HHC intensity, measured as the number of hours of care per day over all episodes of care within a given calendar year. We set an upper limit at 48 hours of care per day (equivalent to two full-time day/night carers) for the small number of cases that exceeded this value.

For analyses of variations in HHC transitions, records were censored after 31 December 2016, or following death, emigration or a transition to institutionalized care, whichever came first. Analyses of HHC intensity (hours/day) were limited to observations where individuals were in receipt of HHC.

Covariates

Immigrant background characteristics are our primary interest, with focus placed on three dimensions: immigrant versus native; country group of origin; and length of stay in Norway. Immigrants are defined as persons born abroad to two foreign-born parents and having four foreign-born grandparents, with natives comprising the remaining population who primarily consist of individuals born in Norway with two Norwegian-born parents.

Country group of origin categorizes immigrants into four groups based on origin country background. The grouping closely matches the one used in the official population projections (Thomas and Tømmerås Reference Thomas and Tømmerås2024), except that Nordic immigrants have been singled out as a separate group and Eastern European immigrants include those from EU and non-EU states. The country groups (CGs) are: (1) Nordic; (2) Eastern European; (3) Western; and (4) Non-Western. Group CG3 comprises all Western European countries, the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Group CG4 includes all remaining countries (i.e. those in Asia, Africa, and South and Central America). According to official statistics for the period studied here, the distributions of immigrants aged 60+ across the constituent sub-regions of CG4 were 64 per cent (Asia), 14 per cent (Africa) and 12 per cent (South and Central America) (Statistics Norway 2024b).

Immigrants’ duration of residence is divided into three groups: (1) <10 years; (2) 10–29 years; and (3) 30+ years. All immigrant background measures are time invariant, except length of stay, which changes over time.

Additional socio-demographic variables of interest include educational attainment, which was time-invariant and categorized into (1) Low (compulsory and secondary education) and (2) High (tertiary education), in line with the ISCED-2011 classification. Those with missing education were assigned to the Low education category. The remaining covariates were time varying across person-years. Personal income was grouped into (1) Below median income and (2) Median or above income, based on income quartiles by age group, sex and year. Living situation was categorized as (1) Living alone and (2) Not living alone, while parental status was dichotomized as (1) Parent (of at least one child of any age who is resident in Norway) and (2) Childless (no child resident in Norway). To adjust for geographical context in the provision of HHC, we included a dummy separating (1) Urban municipalities from (2) Less urban areas (the rest), with urban reflecting those municipalities defined as ‘central’ in Statistics Norway’s four-level 2008 centralization index (Statistics Norway 2025). When analysing HHC intensity, we also include a variable that records the number of years that HHC has been received prior to the given observation year. In addition, we adjust for calendar year (2011, 2012, … 2016) and age group (60–64, 65–69, … 90+).

Methods

To assess variations in HHC transitions, we employ binary logit population average models (using the generalized estimating equation) with an exchangeable within-individual correlation structure. We employ robust standard errors (the Huber/White/sandwich estimator of the variance) to improve the validity of statistical inference in the presence of potential misspecification of the assumed correlation structure (Liang and Zeger Reference Liang and Zeger1986). Here, Y = 1 if HHC was received by an individual at any point during the calendar year; Y = 0 otherwise. Population average models are particularly useful in this context because they provide population-averaged effects, which are often easier to interpret, especially in the context of binary outcomes. Random effects models estimate subject-specific effects, which can be less intuitive for binary outcomes, while fixed effects models would prohibit the estimation of the effects of immigrant background characteristics given their time-constant nature. To determine whether variations in HHC transitions exist according to immigrant background characteristics, our initial model includes immigrant country group of origin and adjusts for socio-demographic background characteristics. We then include interactions between country group of origin and the socio-demographic variables, to identify whether the general associations between socio-demographic characteristics and HHC transitions are moderated by country group of origin. Finally, we include a composite variable that defines immigrants according to both their country group of origin (Nordic; Eastern European; Western; or Non-Western) and duration of residence (< 10 years; 10–29 years; or 30+ years), with natives as the reference (Table 3).

We modelled HHC intensity via linear population average models, again with an exchangeable within-individual correlation structure and robust standard errors. The continuous dependent variable is the number of hours of care per day across all spells of care for those who were in receipt of HHC during the calendar year. For linear models (continuous response), the estimates of marginal and random-effects models coincide. The same three-step iterative modelling strategy is employed: model immigrant background adjusting for socio-demographic characteristics; model interactions between immigrant background and socio-demographic characteristics; and model the composite variable identifying immigrant background by duration of residence in Norway. Standard errors in all models for HHC transitions and HHC intensity are adjusted for clustering at the individual level. Separate models by gender revealed few substantive differences from the results presented in the next section, which are based on the full two-sex samples with dummy variables used to identify gender.

Results

Descriptives

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the analytical samples used in the analyses that follow. Compared to the native population, immigrant groups tend to be younger, have smaller shares of low educated (except non-Western) and have larger shares with below median income, though sizable variation across the immigrant groups does exist. Childlessness, living alone (except non-Western) and living in an urban municipality are also more common among immigrants. There are variations by duration of residence across the immigrant groups, although, given that our focus is on older immigrants, relatively few have durations of residence below ten years. Immigrants on average have lower HHC transition rates, with the lowest transition rates being observed for non-Western immigrants (2.1 per cent of person-years, 8.8 per cent of individuals) and Eastern European immigrants (2.0 per cent of person-years, 7.7 per cent of individuals). From Panel B in Table 1, we see that HHC intensity is also lower among immigrant groups, and particularly among non-Western origin immigrants.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics by country group of origin

Notes: Panel A portrays data used for analysing HHC transitions and thus includes all individuals at risk of such a transition. Panel B portrays data used for analysing HHC intensities and thus includes only recipients of HHC. Descriptive statistics for Panel A (%) and Panel B (median, mean and standard deviation) are based on person-year observations, unless stated otherwise.

Analysis of transitions into HHC

Table 2 presents the results of an initial model that focuses on the relative risks of HHC transitions by country group of origin, having conditioned on socio-demographic characteristics (age group, sex, education, income, living alone, childlessness, if living in an urban municipality and calendar year). The results show natives to have the highest likelihood of transitioning into HHC, followed by Nordic-origin (OR = 0.93), Western-origin (OR = 0.81), non-Western (OR = 0.77) and Eastern European immigrants (OR = 0.65).

Table 2. Odds ratios for HHC transitions by country group of origin

Notes: Observations n = 5,736,469. Population average model using generalized estimating equation (GEE) approach with exchangeable within-group correlation structure. Standard errors adjusted for clustering at individual level (1,220,091 clusters). Model results adjusted for age group, sex, education, income, living alone, childlessness, if living in an urban municipality and calendar year. Full model results available in online supplemental material Appendix B.

To assess whether country group of origin moderated the typical socio-demographic associations with transitions into HHC, we include a series of two-way interactions terms. The resulting predictive margins (on the probability scale) are presented in Figure 1 (regression results in tabular form are provided in online supplemental material Appendix C). As we would expect, a general pattern of increasing probabilities to transition to HHC for older age groups is observed across all country groups of origin (top left, Figure 1). With that said, once we focus on ages 80+ among those from Eastern European and non-Western origins, transition propensities are low with little difference between the older age groups. It is among those aged over 80, and even more so for those aged over 90, that the largest age differentials by immigrant background emerge. Compared to native Norwegians aged 90 and over, equivalent non-Western immigrants have on average a 19-percentage point (pp) lower probability of transitioning into HHC, while for equivalent Eastern European origin immigrants it is 17 pp lower.

Figure 1. Predictive margins and 95 per cent confidence intervals for HHC transitions: interactions between country group of origin and socio-demographic characteristics.

With regards to the other socio-demographic characteristics, we see the largest within-group differences by socio-economic status (i.e. education and income levels) and family composition (living alone and childlessness) in the Norwegian-born population. The smallest within-group differences in HHC uptake along these dimensions are typically observed among immigrants with non-Western backgrounds. While the broad socio-demographic patterning to HHC transitions generally holds across country background groupings (i.e. higher likelihood of transitioning into HHC when lower educated, lower income, living alone, childless and residing in less urban municipalities), there are some deviations from this general picture. In line with previous findings on family composition and LTC utilization in the Nordic context (Artamonova et al. Reference Artamonova, Brandén, Gillespie and Mulder2023; Syse et al. Reference Syse, Artamonova, Thomas and Veenstra2022), childlessness is associated with higher propensities to transition into HHC for native-born Norwegians and Nordic-origin immigrants. However, for Eastern European immigrants, and to a lesser extent Western-origin immigrants, childlessness appears to be associated with lower transition probabilities, while for non-Western immigrants we observe no significant difference in the likelihood of transitioning into HHC according to the presence of children. We return to these variations by family composition in the conclusion.

Table 3 presents estimated odds ratios for a composite measure that combines country group of origin with duration of residence in Norway, having adjusted for age group, sex, education, income, living alone, childlessness, if living in an urban municipality and calendar year. The results suggest that as durations in Norway increase, there is a gradual trend towards convergence to the transition rates of the native-born population. This trend aligns with previously observed associations between immigrants’ duration of residence, deteriorating health (Elstad Reference Elstad2016) and increased mortality risks (Syse et al. Reference Syse, Dzamarija, Kumar and Diaz2018). With that said, the pattern observed for non-Western immigrants appears somewhat different. Compared to the (relatively high) transition probabilities of the native-born Norwegian population, we observe lower probabilities to transition into HHC among non-Western origin immigrants with medium and long durations of residence, but at short durations of residence there is no difference. The differing reasons for immigration associated with non-Western immigrants is likely to be of relevance here. While data on the reason for immigration are limited to those who arrived after 1990, many older non-Western immigrants with short durations of residence are refugees (52 per cent); among those who transition into HHC the share is 70 per cent. As noted earlier, refugees often do not enjoy the positive health outcomes typically associated with immigrants upon arrival, and poor and deteriorating health can occur owing to poor life circumstances prior to or during the transfer. Having claimed refugee status in older age and relatively recently, we might expect especially pronounced levels of poor health among this population subgroup. The opportunity for a general health assessment upon arrival in Norway may also promote a higher uptake of formal health and care services among recently arriving refugees.

Table 3. Odds ratios for HHC transitions by combined country group of origin and duration of residence categories

Notes: Observations n = 5,736,469. Population average model using generalized estimating equation (GEE) approach with exchangeable within-group correlation structure. Standard errors adjusted for clustering at individual level (1,220,091 clusters). Model results adjusted for age group, sex, education, income, living alone, childlessness, if living in an urban municipality and calendar year.

Analysis of HHC intensities

Table 4 presents results detailing the variations in HHC intensities (hours of care per day) by country group of origin, again adjusting for age group, sex, education, income, living alone, childlessness, if living in an urban municipality, years in receipt of care and calendar year (full model results available in online supplemental material Appendix D). In contrast to the results associated with HHC transitions, differences in HHC intensity by country group of origin are limited. Indeed, the only appreciable difference is associated with immigrants from non-Western backgrounds, where estimates suggest that they receive an average of 0.16 fewer hours of care per day than their native-born peers.

Table 4. Estimated differences in HHC intensities (hours of care per day) by country group of origin

Notes: Observations n = 469,881. Population average model using generalized estimating equation (GEE) approach with exchangeable within-group correlation structure. Standard errors adjusted for clustering at individual level (203,344 clusters). Model adjusted for age group, sex, education, income, living alone, childlessness, if living in an urban municipality and years in receipt of care.

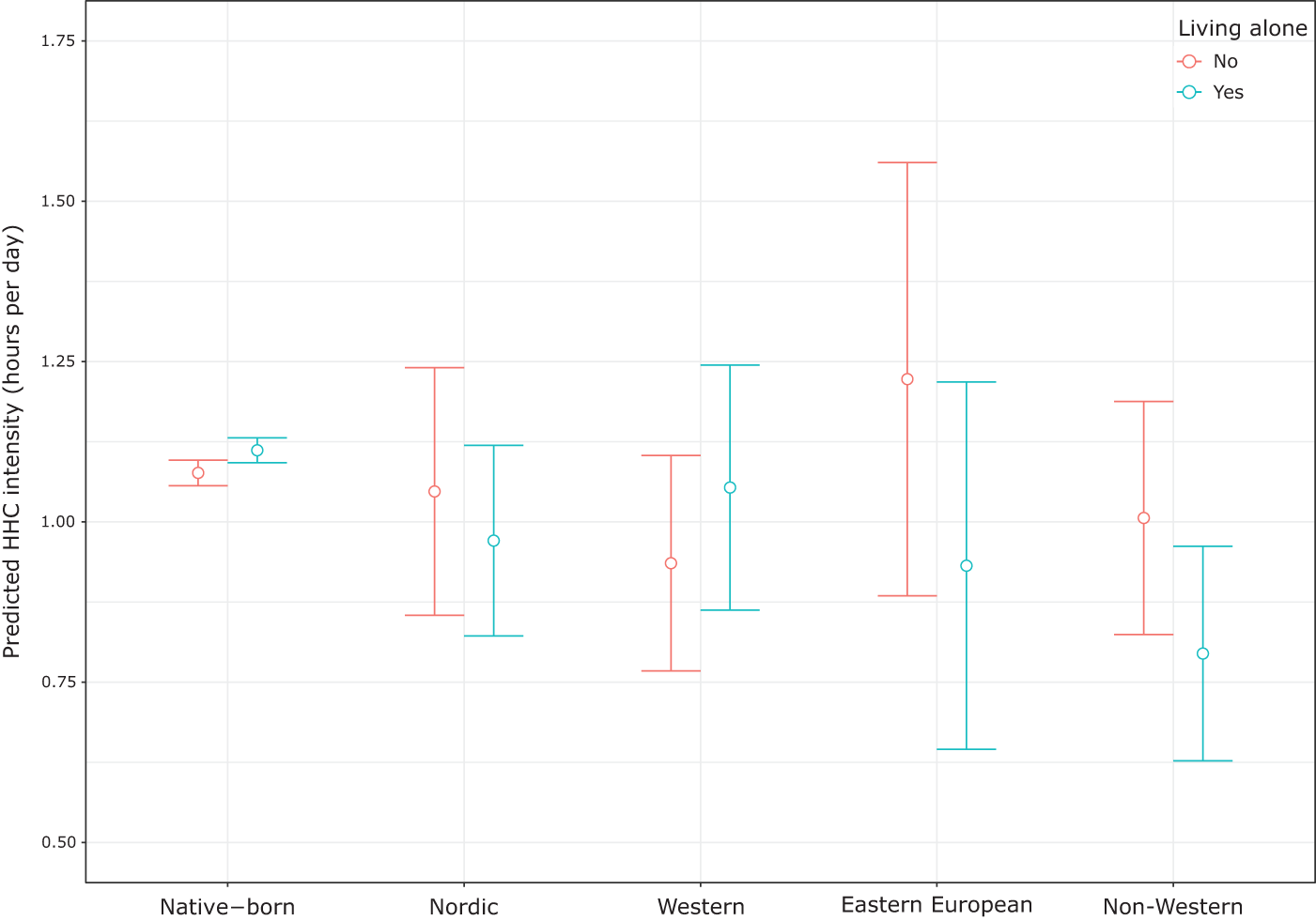

Tests of interactions between socio-demographic characteristics and country group of origin revealed few appreciable effects, except for the term associated with living alone and with a non-Western background. Indeed, when we include this interaction, the main effect for non-Western immigrant background was no longer significant, which suggests that the lower HHC intensities we observed among this group are contingent upon living alone (see Figure 2). Similarly, few differences were observed in HHC intensities when using the composite measure combining country group of origin and duration of stay (see online supplemental material Appendix E). The only significantly lower intensities among immigrants, as compared to natives, related to Nordic-origin immigrants with medium durations of residence (coef. − 0.46) and non-Western immigrants with short durations of residence (coef. − 0.38). There appear to be no appreciable differences in the average hours of care received between natives and immigrants with longer durations.

Figure 2. Predicted average HHC intensities and 95 per cent confidence intervals: interaction between country group of origin and whether living alone or not.

Discussion and concluding remarks

To our knowledge, no prior research has attempted to determine how HHC utilization (transition risks and intensities) might vary by immigrant background characteristics. Given the limited body of existing research, we posed three broad explorative research questions. RQ1 asked: ‘Does the likelihood of transitioning into HHC differ by immigrant background characteristics […] and, if so, in what ways?’. We found that immigrants were less likely to transition into HHC, but transition risks among immigrants trended towards the propensities of the native-born population as durations of stay in Norway increased. No immigrant group had a higher transition risk than natives, but natives and non-Western immigrants with a short duration of residence had similar risks. A closer look at the latter group revealed that 70 per cent of those who transitioned into HHC were recently arrived refugees. RQ2 asked: ‘For those who are in receipt of HHC, are there differences in the intensity of care by immigrant background characteristics?’. Adjusted model results suggested that variations in HHC intensities by immigrant background characteristics were small and not significant for all groups except non-Western immigrants, where we observed fewer hours of care per day on average than for natives. RQ3 asked: ‘Do the patterns associated with the effects of socio-demographic characteristics (e.g. the presence of family and individual socio-economic resources) on HHC utilization differ according to immigrant background characteristics?’. For HHC transitions, the largest variations in the effects of socio-demographic characteristics were observed among the native-born population, with generally less variation by socio-demographic background characteristics among the immigrant groups. Across all country-of-origin groups, higher transition likelihoods were observed for individuals with lower education, lower income, living alone and residing in less urban areas. Associations with childlessness varied: it was linked to higher relative transition propensities among natives and Nordic immigrants, but to lower relative propensities among Western-origin and Eastern European immigrants. Among non-Western immigrants, childlessness appeared to have little influence on transition propensities. For HHC intensity, where only non-Western immigrants were observed to receive significantly fewer hours of care than natives, subsequent analysis of interaction effects indicated that this difference was entirely contingent on living alone: only Non-Western immigrants living alone had significantly fewer hours of care than natives (living alone or otherwise).

These findings on family composition are particularly interesting in the context of previous qualitative research (Hovde et al. Reference Hovde, Hallberg and Edberg2008b), which highlighted a more prominent role of families in health-care provision among non-Nordic immigrants. From this perspective, our expectations might have run in the opposite direction, with fewer familial resources translating into higher HHC uptake particularly among the non-Nordic immigrant groups. Finding lower transition propensities to be associated with childlessness might instead point to the relevance of children in supporting older immigrants’ navigation, interaction and follow-up with formal health-care systems. This finding may also point to potential barriers to accessing care among older immigrants when limited familial support networks exist.

Whether the lower likelihood of HHC utilization among immigrants reflects reduced needs, differences in preferences, potential discrimination in health system evaluations or a lack of health literacy when navigating complex care systems is not clear from this study. Since the likelihood of transitioning into HHC was so much lower among immigrants than natives, one might anticipate that immigrants who do transition receive more intensive care owing to greater needs. Our findings do not support this. No immigrant subgroup had higher estimated HHC intensities than natives.

On the one hand, the higher HHC transition rates associated with long durations of residence could suggest that disadvantageous ‘acculturation’ or cumulative stressors play a role in promoting worse health outcomes among immigrant populations. With that said, additional sensitivity checks suggest that the inclusion of health status does little to adjust associations by immigrant background or country group of origin. On the other hand, this pattern could also reflect adaptation processes in terms of reduced language barriers and an improvement in knowledge of the Norwegian health and care system, including knowledge of eligibility and rights to care and changes in expectations in terms of who is to deliver care (Horn Reference Horn, Torres and Hunter2023; Park et al. Reference Park, Lee and Kang2018). The relatively high HHC transition rates among Nordic-origin immigrants, as compared to the other immigrant groups, support this interpretation. More generally, our findings align with those of studies examining other forms of public health service utilization in Norway (general practitioner (GP) care, emergency primary care services and institutional care), where immigrants generally use fewer health services compared to natives, and where immigrants from high-income countries and those with longer durations of residence tend to have usage more similar to natives (Debesay et al. Reference Debesay, Arora, Bergland, Borch, Harsløf, Klepp and Laitala2019; Diaz and Kumar Reference Diaz and Kumar2014; Dzamarija Reference Dzamarija2022).

Although most people in Norway report that they receive adequate (medical) care (OECD 2021), population ageing and a more diverse older-age population mean that increased efforts will be required to ensure that disparities in LTC utilization do not occur among certain groups of older persons living at home. Since the allocation of care services requires an active approach, where those in need of care (often with assistance from relatives) are responsible for informing health services about their needs, either by making an appointment with the GP or by applying directly to home health services, it will be important to ensure that older immigrants and their relatives are sufficiently informed about, and able to use, such approaches. This comes as a responsibility not only for immigrants and their families but also for health-care services, given previous findings of difficulties in accessing culturally congruent care among immigrants and lower levels of knowledge about (non-Nordic) immigrants among health-care personnel (Hovde et al. Reference Hovde, Hallberg and Edberg2008a; Khatri and Assefa Reference Khatri and Assefa2022).

Limitations and future research needs

While this study has several strengths, such as the use of high-quality register data encompassing the entire Norwegian population aged 60+, measures on the timing and intensity of HHC, and the availability of socio-demographic and immigrant background characteristics, some limitations should be noted. First, given Norway’s relatively recent history of large-scale immigration, the immigrants included in the study period (2011–2016) were still relatively young. As such, we had relatively few cases of immigrants in the older age groups, where the needs and utilization of HHC are most common. Furthermore, marked compositional changes have taken place over time in the older immigrant groups in Norway where, aside from a general ageing of the immigrant population, there has been a growing number and share of refugees entering older ages (see online supplemental material). Future research should thus examine the impact of these compositional shifts in more detail as they likely carry important implications for future care needs in the municipalities, and particularly for patterns associated with older, non-Western immigrants.

Second, formal educational qualifications are registered based on information provided directly to Statistics Norway by the respective educational institutions. Hence, data on education obtained in Norway are almost complete, whereas information on education obtained abroad is incomplete. While our findings relating to education fit with the known associations with health and care needs, they should be treated with caution.

Third, the extent to which missing or incorrect emigration data may have influenced our results could not be examined in detail. Despite legal requirements, some individuals fail to notify the authorities when they emigrate and thus remain in the registered population (at least temporarily) despite having no risk of HHC utilization. This issue applies mostly to immigrants (Tønnessen et al. Reference Tønnessen, Skjerpen and Syse2023). The likelihood of emigrating is, however, greatest in younger ages and in the first few years after immigration and decreases substantially with time spent in Norway (Tønnessen et al. Reference Tønnessen, Skjerpen and Syse2023). Given that we study the older age population, we have relatively small shares with short durations of residence, and the increased HHC utilization observed for longer durations of residence suggests that any bias is likely to be minor.

Fourth, we did not have more detailed information on the country group of origin of non-Western immigrants. A more nuanced look at older immigrants from different regions within this broad grouping is warranted going forwards, particularly given the projected growth and ageing of non-Western immigrant populations (Thomas and Tømmerås Reference Thomas and Tømmerås2024) and the well-known heterogeneity in cultural approaches to care (Horn Reference Horn, Torres and Hunter2023).

Lastly, our data lack information on health, although analyses shown in the online supplemental material suggest that the presence of (co-)morbidities (based on hospitalization data) played a minor role in affecting HHC transition risks by immigrant background characteristics. This limited effect of health may be explained by our focus on the older population, as comparisons are largely based on differences between native-born and immigrant populations with long durations of residence. Still, careful consideration of how health is measured in future work is essential. In register-based studies, health is typically assessed via measures of morbidity. This is problematic when barriers to care are of analytical interest because measures of morbidity are dependent on individuals having already accessed and engaged with health-care systems in the first place. Added to this is the fact that we cannot determine if non-users are healthy or not (Diaz and Kumar Reference Diaz and Kumar2014). Self-reported measures of immigrants’ health in Norway are only available from cross-sectional surveys. When compared to the older general population, survey results for older immigrants suggest significantly lower rates of reporting ‘good’ or ‘very good’ health and significantly higher rates of chronic diseases and impaired functional ability (Norwegian Institute of Public Health 2024). In the context of our results, and for the period studied, such differences in self-reported health offer indirect support to the argument that immigrants either faced greater barriers to accessing HHC or had different preferences and expectations of care provision. Still, robust conclusions in this regard can be drawn only if future research is able to incorporate a direct and accurate measure of health, and ideally one that is not so dependent on access to and utilization of prior health services. From a policy perspective, this is an important ambition. If certain immigrant groups are found to have high health needs but low service utilization, policies can be designed to improve access and reduce barriers.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X25100408.

Financial support

This study was supported by a grant from the Norwegian Research Council (#344365).

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

A licensure to link socio-demographic data to the pseudonymized municipal care use registry (IPLOS) was provided by the National Data Inspectorate in Norway, after ethical review by the Norwegian Board of Medical Ethics (#2014/1708). The need for written informed consent was waived by the Norwegian Board of Medical Ethics, under the Health Research Act §§ 15, 28 and 35. All data handling has been undertaken in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and national ethics requirements.