Impact statement

Microplastics (MPs) are not routinely monitored or effectively removed during water and wastewater treatment processes, posing potential and/or actual risks to human health and are classified as emerging contaminants. MPs are ubiquitous in aquatic environments, and the long-term persistence of plastics in these ecosystems allows them to release chemical additives (plasticizers) used in production. Most plasticizers are hazardous additives that have adverse effects on living organisms, causing hormonal, immune and reproductive disruptions in both aquatic species and humans. Additionally, plastics adsorb persistent organic pollutants, other organic compounds and metals, all of which are hazardous to environmental and human health. Therefore, it is necessary to assess the contamination level of aquatic ecosystems, especially freshwater systems used for human water supply. The results of the present study, for the first time, demonstrated widespread contamination by a diverse range of MPs (encompassing various shapes, colors and polymer types), as well as by a semisynthetic microfiber (artificial cellulose particles), in the Guandu River basin. This freshwater system is the largest water source supplying 8 million people in the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro state (southeastern Brazil), highlighting the potential risks of MP contamination to environmental and human health. This study falls within the context of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals 6 (clean water and sanitation) and 14 (life below water).

Introduction

In a new era defined by consumption, its greatest symbol has become its greatest villain. Plastic emerged as an innovative, highly versatile material, driven by advances in research and technology, and gained increasing prominence, replacing materials such as aluminum and glass (Montenegro et al., Reference Montenegro, Vianna and Teles2020). Due to its chemical composition, plastic tends to persist in the environment for extended periods – a fact that has raised global concern (Lambert and Wagner, Reference Lambert, Wagner, Wagner and Lambert2018). Half-lives of plastic waste vary depending on the polymer type and environmental conditions, ranging from days to centuries (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Armstrong, Walsh, Jackson and Reddy2019). Despite its high durability, plastic is widely applied in single-use applications, such as packaging and disposable bags, which are discarded shortly after use. It is estimated that 40% of all plastic products end up as solid waste within a month or less (Montenegro et al., Reference Montenegro, Vianna and Teles2020). Plastics that are not disposed of in sanitary landfills are released into the environment. For these reasons, plastic has become ubiquitous in aquatic, terrestrial and atmospheric environments, as well as within living organisms, in the form of nano- and microplastics (MPs).

The entry of plastics into the environment is primarily associated with improper disposal of solid waste, domestic and industrial effluents and urban runoff (Andrady et al., Reference Andrady, Pandey and Heikkilä2020). Primary MPs are intentionally manufactured small particles (e.g., microbeads or pellets) (Fendall and Sewell, Reference Fendall and Sewell2009) that often enter the environment through leaks during production, logistical failures during transport and inefficiencies in industrial waste treatment (Andrady et al., Reference Andrady, Pandey and Heikkilä2020). The secondary MPs, the most prevalent in the environment, result from the breakdown of macro- and mesoplastic wastes (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Galgani, Thompson and Barlaz2009; Thompson, Reference Thompson, Bergmann, Gutow and Klages2015). The fragmentation processes are mediated by photolysis, thermal oxidation, hydrolysis, biodegradation and physical abrasion by sediment particles (Andrady, Reference Andrady2011, Reference Andrady, Bergmann, Gutow and Klages2015). In many cases, MPs exist in a transitional state between macrodebris and nanomaterials. It is estimated that the fragmentation of MPs could generate several nanoparticles exceeding the original abundance by more than 1014 times (Besseling et al., Reference Besseling, Redondo-Hasselerharm, Foekema and Koelmans2018). The high variety of plastics and processes allows MPs to be found in several sizes, shapes (e.g., fragments, fibers, films and beads) and colors in the environment (Ivar do Sul et al., Reference Ivar do Sul, Costa and Fillmann2014).

Originating from excessive plastic consumption in both urban and rural environments, MPs are transported to freshwater systems via wind and rainfall, industrial effluent and runoff from land-based sources (Bhardwaj et al., Reference Bhardwaj, Rath, Yadav and Gupta2024). They can infiltrate groundwater through leaching and percolation processes, but wind and rain also carry particles from landfills, tire wear, paints and sewage networks (Hale et al., Reference Hale, Seeley, La Guardia, Mai and Zeng2020). Within households, washing synthetic fiber textiles (e.g., polyester [PES], polyurethane [PU], polyamide [PA] and polyacrylonitrile) and semisynthetic textiles (e.g., artificial cellulose particles [ACPs], including rayon) releases large amounts of microfibers into the sewage system, which eventually reach aquatic ecosystems (Luzi et al., Reference Luzi, Carnevale Miino, Rada, Zullo, Baltrocchi, Torretta and Galafassi2025). Other aquatic sources of MPs include fishing and aquaculture activities, which involve the use of polymer-based nets, lines, traps and tanks. Additionally, boat paints degrade over time, releasing MPs and other contaminants (Hale et al., Reference Hale, Seeley, La Guardia, Mai and Zeng2020).

MPs are considered emerging contaminants, as they are not routinely monitored or effectively removed during water and wastewater treatment processes and pose potential and/or actual risks to human health (Morin-Crini et al., Reference Morin-Crini, Lichtfouse, Liu, Balaram, Ribeiro, Lu, Stock, Carmona, Teixeira, Picos-Corrales, Moreno-Piraján, Giraldo, Li, Pandey, Hocquet, Torri, Crini, Morin-Crini, Lichtfouse and Crini2021). It is essential to highlight that, over the long persistence and degradation of plastics in aquatic ecosystems, chemical additives used in plastic production are released, potentially causing adverse effects on living organisms (Melzer et al., Reference Melzer, Rice, Depledge, Henley and Galloway2010; DeWitt, Reference DeWitt2015; Pan et al., Reference Pan, Wang, Yeung, Wei and Dai2020). Plastics have a high adsorption potential and act as “carriers” of persistent organic pollutants, as well as other organic compounds and metals. Moreover, plasticizers, such as phthalates and bisphenols, are hazardous additives known to cause hormonal, immune and reproductive disruptions in both aquatic species and humans (Bereketoglu and Pradhan, Reference Bereketoglu and Pradhan2022; Eales et al., Reference Eales, Bethel, Galloway, Hopkinson, Morrissey, Short and Garside2022; Ghosh et al., Reference Ghosh, Sinha, Ghosh, Vashisth, Han and Bhaskar2023; Manatunga et al., Reference Manatunga, Sewwandi, Perera, Jayarathna, Peramune, Dassanayake, Ramanayaka and Vithanage2024).

Although scientific studies on the health effects of MPs in humans are still limited, it is known that due to their persistence in the gastrointestinal and pulmonary systems, these particles can cause various adverse effects, including potential intoxication from both additive and adsorbed chemicals (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Tang, Liu and Wang2022; Yee et al., Reference Yee, Hii, Looi, Lim, Wong, Kok, Tan, Wong and Leong2021; Blackburn and Green, Reference Blackburn and Green2022). Thus, assessing the presence of MPs in freshwater ecosystems, especially in drinking water sources, is crucial for understanding human exposure and inferring health risks, as these particles are not removed in conventional water and wastewater treatment processes. In this sense, the present study aimed to assess MP contamination in surface water from lentic and lotic sites comprising the Guandu River basin, the largest water source supplying more than 8 million people in the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro (southeastern Brazil). Besides MPs, microfibers composed of ACPs in surface waters have also been reported, as this emerging class of anthropogenic contaminants is a source of leached chemical additives.

Methods

Study area

The Guandu River basin encompasses the second Hydrographic Region of Rio de Janeiro state in Brazil, comprising 15 municipalities and including the Guandu Water Treatment Plant (Guandu WTP), operated by the Rio de Janeiro State Water and Sewage Company – CEDAE (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Soares, Farias, Lima, Teixeira Junior, Silva and Maurício2001). The Guandu basin has an extension of 108.5 km and an area of 1,385 km2, extending from the confluence of the Ribeirão das Lajes River with the Santana River to the mouth of Sepetiba Bay (22.55–23.19° S and 43.29–44.28° W; Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Miyahira, Rodrigues, Santos and Neves2025). Although it receives contributions from its tributaries, the river’s main flow comes from the Ribeirão das Lajes reservoir, which is regulated by the Pereira Passos Hydroelectric Power Plant in Piraí city (Rio de Janeiro state). Ribeirão das Lajes Reservoir is currently used as a domestic water supply for about 1 million people, with its water receiving simple chlorination before use. The reservoir is an oligo-mesotrophic freshwater system, a special class under Brazilian legislation (Guarino et al., Reference Guarino, Branco and Diniz2005). The surrounding area features Atlantic Rain Forest formations and fragments, which contribute to the reservoir’s high water quality (Branco et al., Reference Branco, Kozlowsky-Suzuki, Sousa-Filho, Guarino and Rocha2009). In the vicinity of the Ribeirão das Lajes reservoir, the Vigário reservoir – an artificial lake surrounded by an urban landscape of villages and roads – is located and is intensively colonized by aquatic macrophytes due to eutrophication (Kasper et al., Reference Kasper, Palermo, Dias, Ferreira, Leitão, Branco and Malm2009). Its depth and steep banks provide habitat for free-floating macrophyte species, including Salvinia auriculata, Pistia stratiotes and Eichhornia crassipes, which occur both as small mats floating on the water surface and as continuous cross-sectional covers (Molisani et al., Reference Molisani, Kjerfve, Silva and Lacerda2006). The Vigário reservoir receives water from the Santana reservoir, which in turn receives water from the Piraí (20 m3s−1) and Paraíba do Sul rivers (up to ~160 m3s−1) (Kasper et al., Reference Kasper, Palermo, Dias, Ferreira, Leitão, Branco and Malm2009). Its main uses are as a water supply for the human population, for generating electrical power and for fishing activities.

In its upper course, the Guandu River runs adjacent to low-income urban areas, including the city of Japeri, which has an estimated population of 102.171 thousand people and a population density of 1,178.61 people km−2 (IBGE, 2024). Until 2014, in Japeri city, a solid waste landfill accumulated garbage from the surrounding population, and during periods of heavy rainfall, leachate runoff flowed into the Guandu River (Leal et al., Reference Leal, MLTG and Cruz2024). The increase in Guandu River flow following the diversion of the Paraíba do Sul and Ribeirão das Lajes rivers enabled the construction of the Guandu WTP for human supply. In operation since 1955, this plant is the world’s largest, currently processing 43 m3s−1 of water for the domestic supply for more than 8 million people in the Rio de Janeiro metropolitan region (COPPETEC, 2014; Kelman, Reference Kelman2015). Upstream of the Guandu WTP intake, in a short geographical distance, lies the Guandu Lagoon, where the Poços and Ipiranga rivers flow. Both are heavily contaminated by sewage, industrial effluents and solid waste from surrounding low-income communities (Coelho and Antunes, Reference Coelho, Antunes, Filho, Antunes and Vettorazzi2012). Given that multiple municipalities heavily rely on the Guandu River basin in the Baixada Fluminense (i.e., part of the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro, comprising 13 towns, where more than 3.5 million people live) and on an industrial complex in Itaguaí city, it has been chronically and increasingly affected by contamination from various types of waste. The industrial complex located in Baixada Fluminense has more than 100 active industries, distributed across eight municipalities, with a higher concentration in Rio de Janeiro, Itaguaí and Queimados (Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Miyahira, Rodrigues, Santos and Neves2025).

Sampling

Sampling was conducted along the water quality gradient established by the Environmental Institute of the State of Rio de Janeiro (INEA, 2013). Eleven sampling sites were surveyed in the Guandu River basin, following the river course, including seven cities in Rio de Janeiro state, and the environmental gradient that included sampling sites subjected to distinct degrees of impacts, uses and anthropogenic activities (INEA, 2013). Among these seven cities surrounding the Guandu River, four have high population density with more than 100 thousand inhabitants (IBGE, 2024) and/or significant economic and industrial activities: Nova Iguaçu (843,220 inhabitants), Queimados (149,135 inhabitants), Itaguaí (124,021 inhabitants) and Japeri (102,171 inhabitants). Therefore, the sampling sites extended from the Ribeirão das Lajes reservoir, in the municipality of Piraí, an area with better water quality, to the surroundings of the Guandu Lagoon in the Nova Iguaçu municipality, an area with the poorest water quality, where the water intake for treatment and human supply occurs (Guandu WTP).

Sampling was conducted in 11 sites, of which seven are characterized as lentic waters (i.e., stagnant or nonflowing water bodies): Guandu Lagoon (ST1 and ST2), Patos Lagoon (ST4) and the reservoirs of Paracambi (ST8), Pereira Passos (ST9), Vigário (ST10) and Ribeirão das Lajes (ST11). The remaining four sampling sites are lotic environments (i.e., with constant water flow) located along the main course of the Guandu River from downstream to upstream: ST3, ST5, ST6 and ST7 (Figure 1). Sampling was conducted in two seasonal periods, the cold-dry period in August 2022 and the warm-rainy period in April 2023.

Figure 1. Geographical location of sampling sites (ST1–ST11) in the Guandu system, covering lentic environments (e.g., lagoons and reservoirs) and lotic environments (river course), in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Codes represent sampling sites in the Guandu Lagoon (ST1 and ST2), Patos Lagoon (ST4) and the reservoirs of Paracambi (ST8), Pereira Passos (ST9), Vigário (ST10) and Ribeirão das Lajes (ST11); all the other sites were located along the main course of the Guandu River (ST3, ST5, ST6 and ST7). Different symbols indicate the potential sources of microplastics: the oldest landfill area in Japeri city (▪), a highly urbanized city with more than 300 thousand inhabitants (**), and highly urbanized cities with less than 300 thousand and more than 100 thousand inhabitants (*).

Water sampling

Water sampling for MP analysis was conducted using a Manta trawl for 3 min, with a net mesh size of 68 μm, deployed from the side of a motorized boat (1 knot). Two independent samplings (i.e., transects covering an extension of 1 km each) with a flowmeter (General Oceanics, 2030R) coupled in the Manta trawl were conducted at the 11 sampling sites (Figure 1). The volume of water flowed through the neuston net ranged from 2.5 × 104 to 6.91 × 104 L. Water samples were conditioned in glass flasks decontaminated using intensive rinsing with filtered ultrapure water (0.45 μm) and filtered denatured alcohol (0.45 μm) (Frias et al., Reference Frias, Pagter, Nash, O’Connor, Carretero, Filgueiras, Viñas, Gago, Antunes, Bessa, Sobral, Goruppi, Tirelli, Pedrotti, Suaria, Aliani, Lopes, Raimundo, Caetano, Palazzo, de Lucia, Muniategui, Grueiro, Fernandez, Andrade, Dris, Laforsch, Scholz-Böttcher and Gerdts2018). All the samples were frozen (−20 °C) until laboratory analysis to avoid organic matter decomposition before sample processing. Sampling was conducted following the approval of the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio, no. 81,992) and the National System for the Management of Genetic Heritage and Associated Traditional Knowledge (SISGEN, no. A387CEF).

MP separation

MP separation from water samples was performed according to the BASEMAN protocol for monitoring MPs in water (Gago et al., Reference Gago, Filgueiras, Pedrotti, Caetano and Firas2019). After the sample was defrosted at room temperature, an organic digestion step was performed at a low temperature (40 °C) using a 10% potassium hydroxide solution (KOH) at 1:3 volume sample:solution ratio for 48 h, followed by an additional step with a 15% hydrogen peroxide solution (H2O2) at 1:1 volume sample:solution ratio for 48 h (Gago et al., Reference Gago, Filgueiras, Pedrotti, Caetano and Firas2019). Between each chemical step, samples were washed with filtered ultrapure water using a stainless-steel membrane (25 μm) to remove the previous solution, and then placed in a decontaminated glass flask for the next step. After the two digestion steps, density separation was conducted using a saturated sodium chloride solution (NaCl), and the supernatant was filtered through a hydrophilic nitrocellulose membrane (MF-Millipore HAWG04700, 0.45 μm) using a vacuum pump system. Membranes were placed in previously washed and decontaminated glass Petri dishes and kept at room temperature (25 °C) in a desiccator with silica gel. All the field and laboratory procedures were performed using washed and decontaminated nonplastic materials, filtered ultrapure water and solutions (0.45 μm) to prevent cross-contamination of samples. Additionally, procedural blanks were performed at each laboratory step using flasks containing the same volumes of chemical solutions and ultrapure water as those used during processing and filtering through a fiberglass membrane (0.45 μm) for solvent solutions and a nitrocellulose membrane (0.45 μm) for ultrapure water (Gago et al., Reference Gago, Filgueiras, Pedrotti, Caetano and Firas2019). To control airborne contamination, controls of nitrocellulose membranes were placed around the working area during sample processing and MPs quantification. All the samples were covered using aluminum foil or glass as much as possible. No MP particle was detected in blanks (n = 10) or controls (n = 10). Moreover, the proportion of particles not identified in the micro-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (μ-FTIR) analysis using the reference database of plastics was corrected based on the total particles counted for each replicate; therefore, the MP abundance shown in the results represents only the identified plastic polymers and ACPs.

Microparticle analyses

Quantification, classification and chemical analysis

Microparticles retained on the membranes were analyzed using a stereoscope microscope with an attached camera (Leica EZ4 HD). All the MP particles in water samples were quantified and classified by color and shape. MP counts by replicate were divided by the volume of water flowed through the neuston net (m3), and MP abundance is presented in particles m−3. Subsequently, μ-FTIR analysis (Nicolet-6,700 FTIR-ATR Spectrometer from Thermo Fisher Scientific coupled to microscopy with 15× magnification) was conducted on MPs to identify the polymeric matrix in reflection mode. During analysis, particles were placed on a silver-coated metal plate. Groups of the most abundant and representative types (i.e., different shapes and colors) of MPs were chosen to determine their chemical composition, and 86% samples were analyzed (MSFD Technical Group on Marine Litter, 2023). The spectra were recorded between 4,000 and 600 cm−1, with 64 scans and an optical speed of 1.89. Each spectrum was automatically compared to the equipment reference database and the virtual database Open Specy, and only match rates ≥70% were considered. The spectra of the identified polymers are presented in the Supplementary Material.

Data analysis

A two-way multivariate permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was applied to the data to evaluate the influence of sampling sites, seasonal periods (cold-dry and warm-rainy) and the interaction between these factors (site × period) on MPs abundance. When significant, multiple comparison analysis was performed to identify differences within each factor. The analyses were based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity, using 9,999 unrestricted permutations, with the PERMANOVA v.1.6 software (Anderson, Reference Anderson2005). Additionally, a nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test was applied to MP abundance data to test differences between lentic (n = 7 sampling sites) and lotic (n = 4 sampling sites) systems, regardless of the sampling period. In addition, the Mann–Whitney U-test was applied to the polymer proportion data, after transformation by arcsine of the square root, to test differences between seasons. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica 10 software. The map was developed using QGIS 3.34.11, and the graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 8.0.

Results

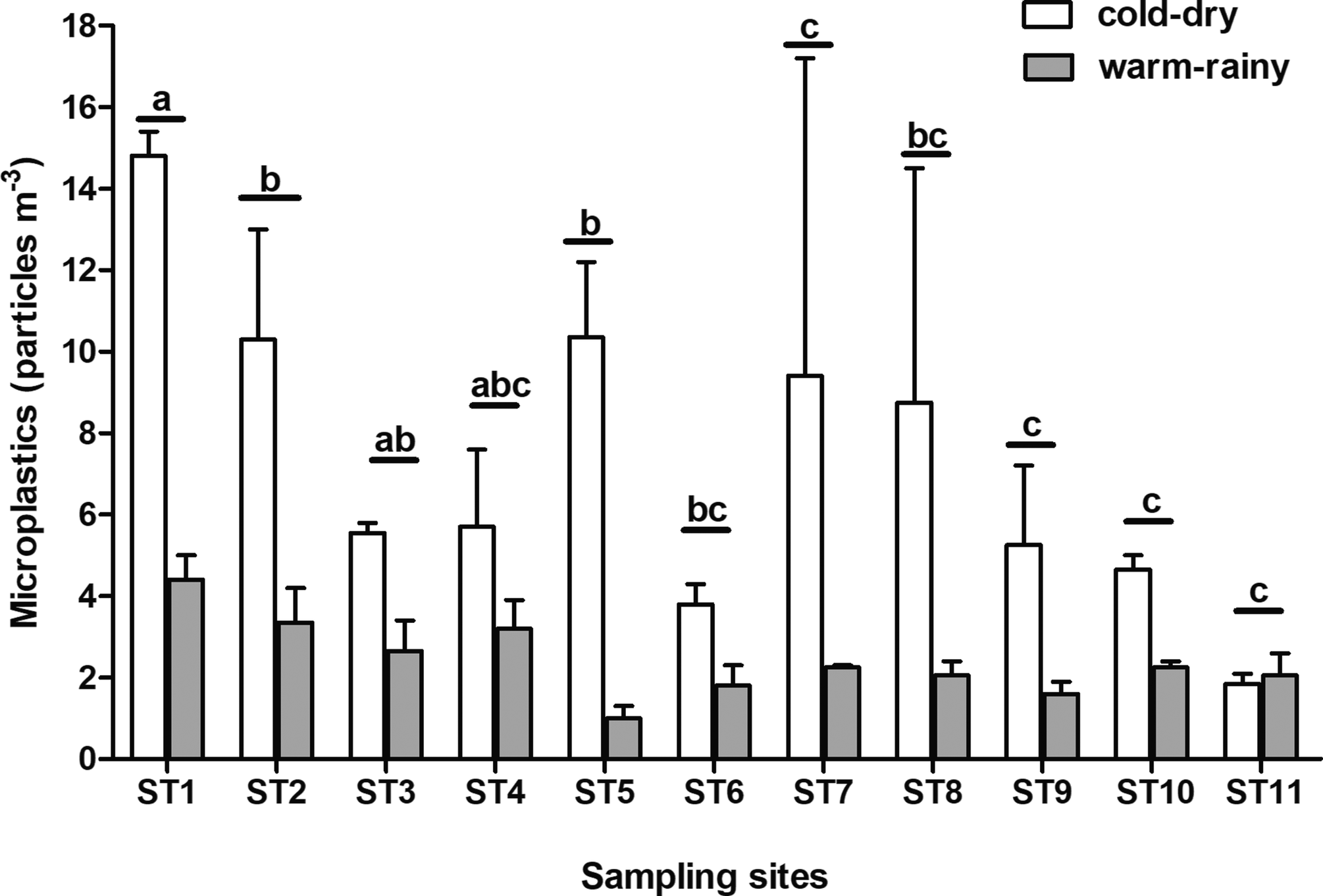

MPs were detected in all 44 samples collected, with 22 from the cold-dry period and 22 from the warm-rainy period. In the cold-dry period, an average of 6.1 ± 4.9 particles m−3 was obtained, whereas in the warm-rainy period, the average was 2.3 ± 1.1 particles m−3. However, no significant difference was found between the seasonal periods (PERMANOVA, F = 1.01 and p = 0.347), nor a significant interaction between the sampling sites and seasonal period (PERMANOVA, F = 1.28 and p = 0.258). A significant effect of sampling site was found on MPs abundance (PERMANOVA, F = 5.54 and p = 0.0002) (Figure 3). Significant differences among sampling sites were mainly due to a trend of higher MPs abundances near the Guandu Lagoon sites (i.e., ST1 and ST2), and lower MP abundances in the reservoirs surrounded by less urbanized areas (ST9, ST10 and ST11; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Microplastic abundance (particles m−3) at the sampling sites in the Guandu River basin during cold-dry and warm-rainy seasons. The different letters indicate significant differences among sampling sites (multiple comparisons test, p ≤ 0.05), regardless of the seasonal period.

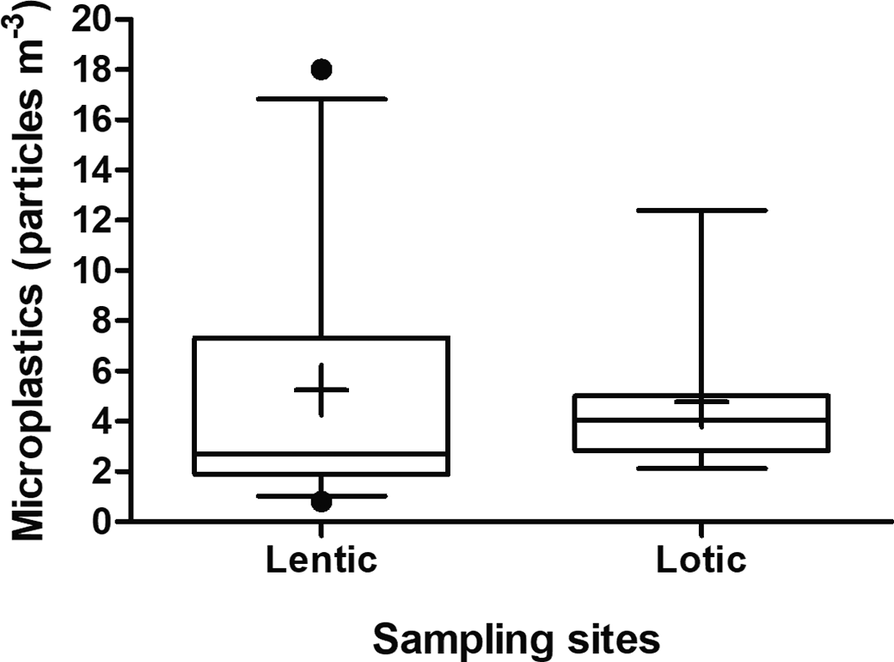

Considering the characteristics of the sampling sites regarding water flow, no significant difference was detected in MPs abundance between the lentic (i.e., ST1, ST2, ST4, ST8, ST9, ST10 and ST11) and lotic (i.e., ST3, ST5, ST6 and ST7) sampling sites (Mann–Whitney U-test, U = 171, Z = −1.28, p = 0.19) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Boxplot of microplastic abundance (particles m−3) at lentic and lotic sampling sites in the Guandu River basin. Lentic areas include lagoons and reservoirs (ST1, ST2, ST4, ST8, ST9, ST10 and ST11). While lotic areas include sites in the main course of the Guandu River (ST3, ST5, ST6 and ST7). The data represent the 5th–95th percentiles (box limits), median (−), mean (+), standard deviation and outliers (•).

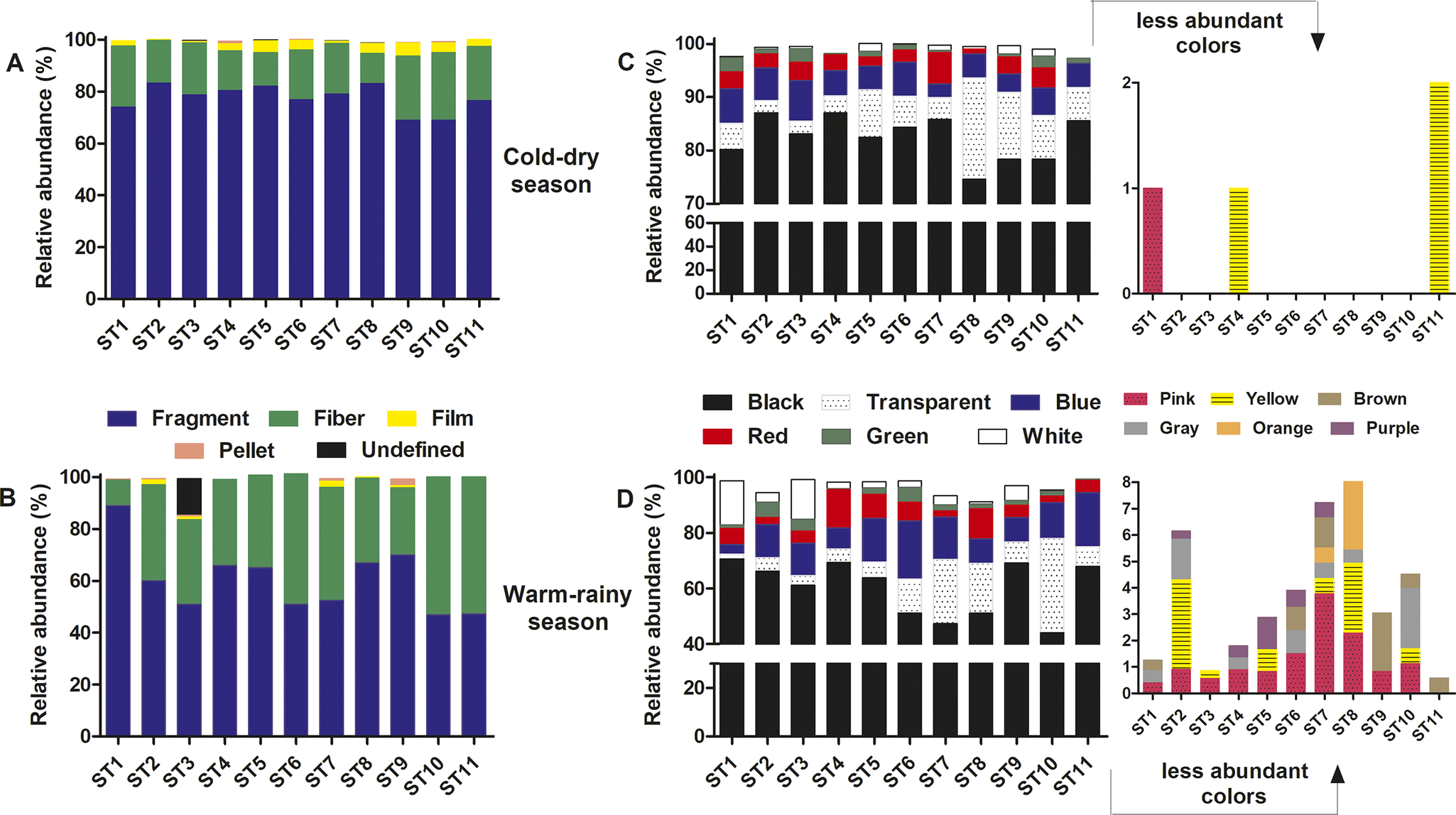

Four MP shapes were identified in the surface water of the Guandu River basin: pellet, fragment, fiber and film (Figure 4A,B). In the cold-dry period, fragments were found in higher abundance (x̄ = 77.9%), followed by fibers (x̄ = 58.9%) (Figure 4A). In contrast, the shape with the lowest abundance was the pellet (x̄ = 0.20%) (Figure 4A). During the warm-rainy period, fragments were again the most representative (x̄ = 60.9%), followed by fibers (x̄ = 37.1%) (Figure 4B). In comparison, the MP shape with the lowest relative abundance was film (x̄ = 0.60%) (Figure 4B). Regarding the colors, 12 different colors were found: black, blue, white, transparent, red, green, pink, orange, yellow, brown, gray and purple (Figure 4C,D). However, four MP colors were exclusively detected during the warm-rainy season: orange, gray, brown and purple. Black-colored particles were predominant in both sampling periods. A mean relative abundance of 82.5% was found in the cold-dry period, followed by transparent (7.05%) and blue (5.05%) particles (Figure 4C). In contrast, in the warm-rainy period, the mean relative abundance of black MPs was 60.2%, followed by blue-colored (12.4%) and transparent (11.1%) particles (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Microplastics in the surface waters of the Guandu River basin. Relative percentage of occurrence by particle shape (%) in the cold-dry and warm-rainy seasons (A and B, respectively). Relative percentage of microplastic occurrence by color (%) in the cold-dry and warm-rainy seasons, including the less abundant colors (pink, yellow, brown, gray and purple) in a complementary graph (C and D, respectively). The data represent the mean relative abundance between independent replicates (n = 2).

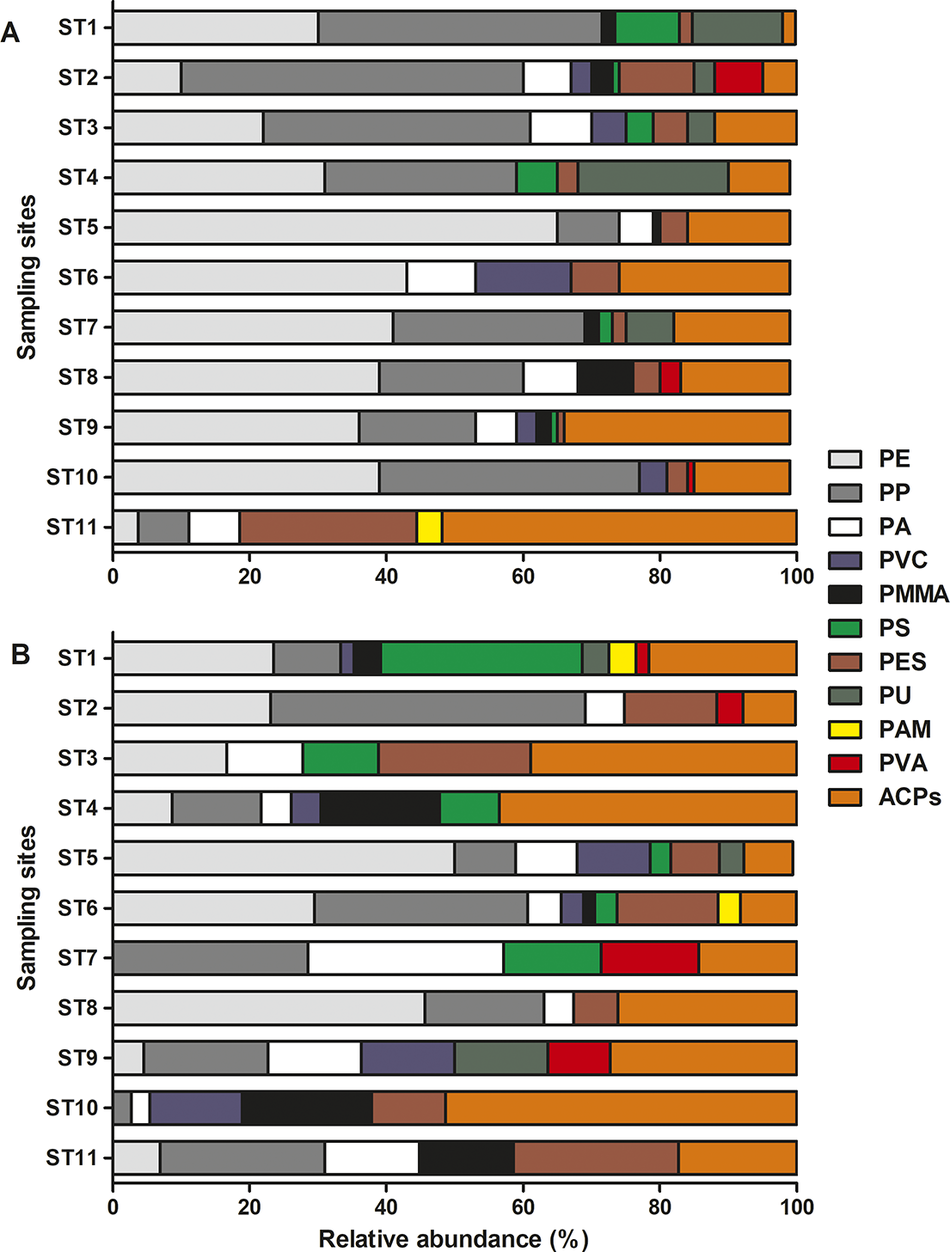

The chemical characterization of the polymeric matrix of MPs was performed on 1,077 representative particles collected from the Guandu River basin. The μ-FTIR analysis detected the presence of 11 types of polymers, where the most abundant polymers in the Guandu River basin were the plastics polyethylene (PE) (x̄ = 25.8%), followed by polypropylene (PP) (x̄ = 21.8%) and the semi-synthetic ACPs (including rayon) (x̄ = 21.2%) (Figure 5). Despite no significant difference in the polymer contribution between seasonal periods (Wilcoxon test, Z = 0.89, p = 0.37), the relative abundance of the most common polymers showed variations between cold-dry and warm-rainy seasons. During the cold-dry season, a greater contribution of PE and PP was observed, with relative abundances of 34.7% and 31.8%, respectively, while ACPs accounted for 14.2%. In contrast, ACPs were the most common polymer in the warm-rainy season, followed by PE and PP. In addition, the relative abundances of PES and PA have increased by 9.00% and 8.90%, respectively, compared to the cold-dry season (by 4.13% and 4.05%, respectively).

Figure 5. Relative abundance (%) of microplastic polymers and artificial cellulosic particles (ACPs) identified in the surface waters of sampling sites in the Guandu River basin by seasonal period: (A) cold-dry season and (B) warm-rainy season. The codes mean polymer identified: polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polyamide – nylon (PA), polystyrene (PS), polyester (PES), polymethyl methaacrylate (PMMA), polyacrylamide (PAM), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyurethane (PU), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and artificial cellulose particles – including rayon (ACPs). The data represent the mean relative abundance of polymers between independent replicates (n = 2).

Discussion

The results of this study reveal MP contamination in the Guandu River basin at all sampling sites, regardless of water flow (lentic and lotic systems) or seasonal variation. However, the significant difference observed between sampling sites in the Guandu River basin suggests a tendency for upstream sites to show lower MP abundance and downstream sites to exhibit higher abundance. This pattern can be explained by the differences in land-use characteristics in the geographical area where this river basin is located. The upstream sites (i.e., ST11, ST10, ST9, ST8 and ST7) are surrounded by rural areas with greater terrestrial vegetation cover (Lessa, Reference Lessa2015; IBGE, 2021). As a result, these sites are subject to lower pressure from urbanization-related factors (e.g., domestic wastewater discharge and/or urban runoff), in addition to their location in geographical areas with more limited access. Ribeirão das Lajes reservoir (ST11) is the most conserved freshwater system evaluated herein, surrounded by Atlantic Rain Forest fragments and controlled access (Branco et al., Reference Branco, Kozlowsky-Suzuki, Sousa-Filho, Guarino and Rocha2009). As the sampling sites move downstream the Guandu River (e.g., ST1, ST2, ST3, ST4, ST5 and ST6), the surrounding areas become predominantly urban (i.e., high population density, improper waste disposal and greater urbanization) (IBGE, 2021). In addition to the downstream areas being more urbanized, near the municipality of Japeri (ST6) lies the confluence with the Macacos River, which carries domestic effluents from the municipalities of Paracambi and Engenheiro Paulo de Frontin, and the Santana River that holds most of the domestic effluents from the Japeri (INEA, 2013). In the Guandu River Lagoon (ST1 and ST2), the Queimados River discharges its waters. This river drains the highly urbanized cities of Queimados, part of the Cabuçu region of Nova Iguaçu and the Queimados Industrial District (INEA, 2013).

Therefore, a rural–urban effect is suggested for MP contamination in the Guandu River basin, as increased MP abundance was observed in areas with predominantly urban surroundings. A rural–urban gradient was observed by Kunz et al. (Reference Kunz, Schneider, Anthony and Lin2023) across various tributaries of the Wu River in Taichung, central Taiwan, where MP abundance increased in residential areas with higher population density. A similar pattern was observed in a study comparing MP abundances in the Guapi-Macacu basin (a more rural region) with those in the Maracanã River Basin and Mangrove Canal, areas with greater urban influence in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Drabinski et al., Reference Drabinski, Carvalho, Gaylarde, Lourenço, Machado, Fonseca, Silva and Baptista Neto2023). The Maracanã River showed the highest MP abundance (86.0% of the total analyzed), while the Macacu and Guapimirim Rivers accounted for 7.50% and 6.60% of the total detected particles, respectively (Drabinski et al., Reference Drabinski, Carvalho, Gaylarde, Lourenço, Machado, Fonseca, Silva and Baptista Neto2023).

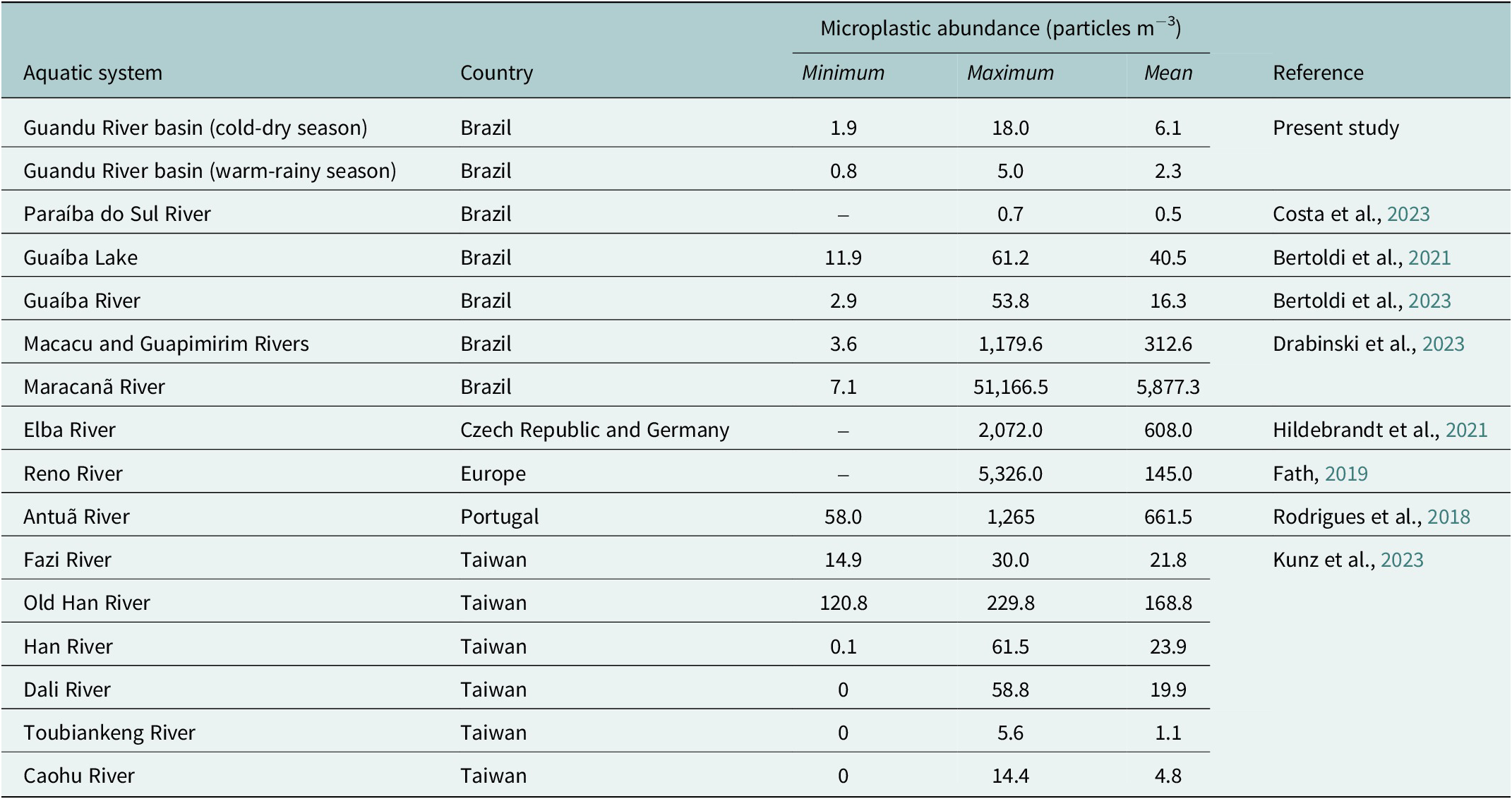

The contamination levels of MPs found in the Guandu River basin fall within the range reported in other freshwater systems in Brazil and abroad (Table 1). Moreover, the rural–urban effect for MP contamination can also be reinforced when analyzing other aquatic systems worldwide (Table 1), as the closer to urban areas – such as rivers flowing through cities – the higher the MP abundances detected by studies, such as in the Antuã River (Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Abrantes, Gonçalves, Nogueira, Marques and Gonçalves2018) and the Rhine River (Fath, Reference Fath2019). In general, the abundance of MPs in the Guandu River basin was lower than that reported in most other studies. However, when compared to the Paraíba do Sul River – a geographically close river that, after its transposition, flows into the Guandu River – the values found in the Guandu River at both seasonal periods are higher (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Zalmon and Costa2023). The Paraíba do Sul River’s location in an area less influenced by urban agglomerations may explain this difference in MP contamination in surface waters.

Table 1. Microplastic abundance (particles m−3) found in surface waters of freshwater systems worldwide. Data are presented as minimum, maximum and mean values when available in the studies

Although no significant difference was detected in this study between cold-dry and warm-rainy seasons, previous studies have found significant seasonal influences on MP contamination in riverine surface waters. For example, Costa et al. (Reference Costa, Zalmon and Costa2023) observed a significant correlation between MP abundances and seasonality, due to the specific characteristics of the Paraíba do Sul River (Southeast Brazil). It has a higher flow rate than the Guandu River and stronger, rainfall-dependent water currents. MP transport into watercourses occurs through surface runoff, where particles are carried from terrestrial to aquatic environments (Su et al., Reference Su, Nan, Craig and Pettigrove2020). Consequently, during periods of higher rainfall, MP transport is more intense. Unlike the Paraíba do Sul River, the Guandu River faces a chronic and severe issue regarding effluent discharge along its course at various locations, which, in addition to the river’s natural conditions, may explain the lack of a significant seasonal influence on MP abundances. The influence of precipitation may vary across a freshwater system, with expected MP increases in some sites but similar or lower abundances than the site average, due to dilution (Stanton et al., Reference Stanton, Johnson, Nathanail, Macnaughtan and Gomes2020).

Regarding MPs’ shape in the Guandu River basin, fragments were dominant, followed by fibers. These MP shapes have been described as the most common in other freshwater systems, such as Guaíba Lake (Porto Alegre – Brazil) (Bertoldi et al., Reference Bertoldi, Lara, Mizushima, Martins, Battisti, Hinrichs and Fernandes2021) and the Antuã River (Portugal) (Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Abrantes, Gonçalves, Nogueira, Marques and Gonçalves2018). The identification of the polymers confirmed that PE and PP were dominant in the Guandu River basin, as in other freshwater systems (e.g., Bertoldi et al., Reference Bertoldi, Lara, Mizushima, Martins, Battisti, Hinrichs and Fernandes2021; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Zalmon and Costa2023; Maharjan et al., Reference Maharjan, Pyakurel, Bista and Dhungel2025). These polymers are commonly found in fragment shape, originating from the fragmentation of larger disposable plastics, such as food packaging, electrical and electronic products and other items used in various industrial sectors, including textiles, automotive and construction (Plastics Europe, 2023). In the Guandu River basin, MP fragments may have originated from illegal dumping sites, sanitary landfills, atmospheric deposition from roadways or improperly discarded solid waste from nearby populations. This observation was supported by our results, particularly at downstream sampling sites, including Guandu Lagoon (ST1 and ST2). This lentic area receives and concentrates solid wastes, chemical and domestic effluents from its tributaries (e.g., Ipiranga River, Cabuçu River and Queimados River), mostly untreated domestic sewage, resulting in high nutrient and bacterial levels (Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Miyahira, Rodrigues, Santos and Neves2025). The ubiquity of fragments in freshwater systems can also be attributed to the discharge of untreated or inadequately treated wastewater directly into rivers (Kataoka et al., Reference Kataoka, Nihei, Kudou and Hinata2019). Another potential source of fragment-shaped particles is the terrestrial environment, where macro- and mesoplastics fragment into increasingly smaller particles that are carried into river channels (Sankoda and Yamada, Reference Sankoda and Yamada2021). At Guandu Lagoon (ST1 and ST2), the relative abundances of fragments were higher and may be related to these discharges from multiple sources.

Microfibers have been commonly reported in other freshwater systems (e.g., Chinfak et al., Reference Chinfak, Sompongchaiyakul, Charoenpong, Shi, Yeemin and Zhang2021; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Zalmon and Costa2023; Drabinski et al., Reference Drabinski, Carvalho, Gaylarde, Lourenço, Machado, Fonseca, Silva and Baptista Neto2023). Microfibers may originate from synthetic (e.g., PES and PA) and semi-synthetic (e.g., ACPs) textiles, which are released during laundry and may indicate the inefficiency of wastewater treatment processes in removing MPs (Browne, Reference Browne, Crump, Niven, Teuten, Tonkin, Galloway and Thompson2011), in addition to the possible absence of sanitation infrastructure and/or direct discharge of domestic effluents into river tributaries in certain regions. Fibers derived from nylon fishing nets (PA) are also frequently found in systems where fishing activity occurs (Biswal, Reference Biswal, Sharma, Biswas and Nadda2024). In the present study, microfibers were the second-most prevalent material, in relative terms, represented by polymers such as ACPs, PES and PA. In addition, the relative contribution of microfibers increased in the warm-rainy season, when ACPs were the most abundant polymer identified, and the relative contribution of microfibers (PES and PA) also increased. The increase in microfiber occurrence during the warm-rainy season, across both shape and polymers, at sites in the Guandu River basin, appears to be related to higher inflows from tributaries and domestic effluents. In addition, sedimentary MPs may be resuspended as the river’s suspended solid load increases during rainfall (Stanton et al., Reference Stanton, Johnson, Nathanail, Macnaughtan and Gomes2020), which can explain the rise in relative contribution of denser polymers – PES (1.24–1.3 g cm−3) and PA (1.04–1.4 g cm−3) – during warm-rainy period in the Guandu River basin. Some fibers may also be composed of PE terephthalate (PET), a PES polymer (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ndungu, Li and Wang2017), which has a higher density and can even exceed that of freshwater (1.03 g cm−3) (Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Abrantes, Gonçalves, Nogueira, Marques and Gonçalves2018). A characteristic of the main course of the Guandu River is the absence of aquatic vegetation (e.g., submerged macrophytes) and the moderate flow along its course, which results in the suspension of less dense particles in the water column. Aquatic vegetation retains MPs on leaf surfaces, promoting the settling of buoyant particles and reducing their availability in surface water (Sfriso et al., Reference Sfriso, Tomio, Juhmani, Sfriso, Munari and Mistri2021; Miloloza et al., Reference Miloloza, Putar, Starin, Novak and Kalcíková2025). Within the Guandu River basin, free-floating macrophytes occur only in abundance in the eutrophic Vigário reservoir (ST 10; Molisani et al., Reference Molisani, Kjerfve, Silva and Lacerda2006), which might contribute to the lower MPs’ abundance in its surface water. In contrast, denser particles tend to settle until flow increases and/or turbulent events (such as rainfall) resuspend them (Ockelford et al., Reference Ockelford, Cundy and Ebdon2020; Xia et al., Reference Xia, Rao, Deng, Chen and Xie2020). This may also explain the tendency toward increased microfiber relative contribution during the warm-rainy season in the Guandu River basin.

MPs colors found in the Guandu River basin were similar to those reported in other studies worldwide (Table 1), with black, blue and transparent being the most common colors; however, the order of prevalence varied. Plastic chromatic color can affect plastic aging and MP formation by influencing its solar absorbance and ultraviolet (UV) transmittance (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Wang, Yee Leung and Wu2022). Blue plastics cannot effectively absorb UV light, which makes blue-colored plastics age faster in the sun, and a higher proportion of bluish MPs is often found in the environment compared to red or yellow particles, while black, white and gray are achromatic colors (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Wang, Yee Leung and Wu2022). Twelve different MP colors were found in the Guandu River basin; among them, black, blue and transparent were the most abundant. From a consumer perspective, color diversity may be perceived as attractive and positive. However, for aquatic animals, it is a concern, as it increases the likelihood of mistaking MPs for food and thus ingesting them (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ndungu, Li and Wang2017). Another concern related to color is the adsorption of chemical contaminants, as MPs’ color can influence the extent of adsorption (reviewed in Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wong, Chen, Lu, Wang and Zeng2018; Hu et al., Reference Hu, Johnson, Jiang, Zhang, Huang, Xi and Xu2023). Black and aged particles may have higher concentrations of chemicals than particles of other colors (reviewed in Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wong, Chen, Lu, Wang and Zeng2018). This is particularly relevant in the context of the contamination scenario in the Guandu River basin, where black MPs were predominant. Moreover, because most black MPs are fragments composed of PE and PS (Frias et al., Reference Frias, Sobral and Ferreira2010), these polymers often exhibit a high sorption affinity for organic chemicals (reviewed in Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wong, Chen, Lu, Wang and Zeng2018). Conversely, the greater contribution of transparent MPs during the cold-dry season may be attributed to the widespread use of transparent plastic packaging and to fishing-related activities (Drabinski et al., Reference Drabinski, Carvalho, Gaylarde, Lourenço, Machado, Fonseca, Silva and Baptista Neto2023).

The high diversity of different polymers identified in the Guandu River basin (i.e., 10 MPs and one semisynthetic fiber [ACPs]) highlights the multiple sources of MPs and estimated origins, such as synthetic and semisynthetic textiles for clothing and shopping bags (e.g., PES, PA and ACPs), packaging sacks (PE), fragmentation from diverse and unidentified large plastics (e.g., PE and PP), foam (e.g., PS and PU), road and ship paints and varnishes (e.g., PU, PMMA and PAM) (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Orlowski and Bopf2024). To better contextualize potential contamination sources, further studies on land use and coverage in the areas surrounding the Guandu River basin are necessary, combined with mapping of sanitation infrastructure, identification of public access areas and the points at which different types of effluents are discharged. This approach will enable a better understanding of MP occurrence by site, considering their shape, color and polymer type and dispersion potential throughout the freshwater system. Moreover, for the first time, the levels of MP contamination in the surface waters of the Guandu River basin, a freshwater system of high environmental, economic and social relevance, were elucidated. The present results may support the development of public policies and actions to mitigate the impacts of emerging contaminants in the Guandu River basin. The ubiquity of MPs in all analyzed samples from the Guandu River basin underscores the need for increased scrutiny of water quality in this freshwater system, reinforcing concerns aligned with global discussions, especially Sustainable Development Goals 6 (clean water and sanitation) and 14 (life below water).

Conclusions

MP contamination was observed at all sites in the Guandu River basin, as well as in the ACPs microfibers, with the Guandu Lagoon (ST1 and ST2) showing the highest contamination levels during both seasonal periods. MPs’ contamination patterns (shape, color and polymers) in the Guandu River basin were similar to those found in freshwater systems worldwide. It is noteworthy that a rural–urban effect was identified among the sampling sites, highlighting the influence of contamination sources, including metropolitan areas with highly urbanized cities and tributary rivers polluted by effluents from domestic and industrial regions that discharge into the Guandu River, and improperly discarded plastic waste. Moreover, the high diversity of plastic polymers identified in water samples suggests multiple sources of MPs and their estimated origin. The identification of microfibers produced by other emerging contaminants (ACPs) highlights the multisource nature of contaminants in freshwater systems. This underscores the need for an urgent discussion on reducing plastic use worldwide and implementing mitigation policies, given that the Guandu River is the primary water source for WTP Guandu, which supplies “treated” water to more than 8 million people in the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro state (Brazil).

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/plc.2025.10038.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/plc.2025.10038.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and/or its Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ademário and Batata for field support, as well as to the team of the Eco-Shift Guandu project and to UNIRIO employees.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: L.N.S., R.A.F.N.; Methodology: A.N.F., L.N.S., R.A.F.N.; Validation: C.d.S.O., R.S.G., A.N.F., L.N.S., R.A.F.N.; Formal analysis: R.A.F.N.; Investigation: C.d.S.O., R.S.G., A.N.F., L.N.S., R.A.F.N.; Resources: L.N.S., R.A.F.N.; Writing – original draft: C.d.S.O., R.A.F.N.; Writing – review and editing: C.d.S.O., R.S.G., A.N.F., L.N.S., R.A.F.N.; Funding acquisition: L.N.S., R.A.F.N.

Financial support

This study is part of the PlastiTox® and Emerging Contaminants projects supported by the Foundation Carlos Chagas Filho Research Support of the State of Rio de Janeiro – FAPERJ (E-26/204.410/2024 and E-26/210.024/2024, respectively) through Research Grant attributed to R.A.F. Neves and by L’Óreal Brazil-UNESCO-ABC through “Women in Science” Grant awarded to R.A.F. Neves (18ª edition in Brazil/ 2023). This study was also financially supported by FAPERJ through the Program Temáticos (Eco-Shift Guandu: E-26/211.394/2021) coordinated by L.N. Santos, and by the Research Grant attributed to L.N. Santos (E-26/200.489/2023). This study was also financed by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) through Universal projects coordinated by R.A.F. Neves (404346/2021-9) and L.N. Santos (408310/2023-5), and by the Research Grants attributed to R.A.F. Neves (PQ2; 306212/2022-6), L.N. Santos (PQ-C; 308175/2025-5) and C. Oliveira (403655/2020-0).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Comments

Dear Editor of the journal Cambridge Prisms: Plastics

Please find the manuscript entitled “Microplastic contamination in the Guandu River basin: the water supply reservoir of Rio de Janeiro

metropolitan region (southeastern Brazil)” by Catarina de Sá Oliveira, Raimara S. Gomes, Andreia N. Fernandes, Luciano Neves dos

Santos and Raquel A. F. Neves, submitted as Research Article.

Microplastics (MPs) are ubiquitous in aquatic environments. They are not routinely monitored or effectively removed during water and

wastewater treatment processes, posing potential and/or actual risks to human health, and are classified as emerging contaminants.

Our study aimed to elucidate the contamination of MPs in the Guandu River basin. This freshwater system is the largest water source

supplying 8 million people in the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro state (southeastern Brazil), highlighting the potential risks of

MPs contamination to environmental and human health. For this purpose, samples were collected from surface waters using a Manta

trawl at 11 sites during two seasonal periods. MPs were quantified, classified, and identified using µ-FTIR analysis. For the first time, a

widespread contamination by a diverse range of MPs (encompassing various shapes, colors, and types of polymers), as well as a

semi-synthetic microfiber (artificial cellulose particles - ACPs), was observed in the Guandu River basin. Our study falls within the

context of the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals 6 (clean water and sanitation) and 14 (life below water).

We believe that the present study falls within the range of interests of the Cambridge Prisms: Plastics, and we would appreciate

hearing your comments on it. We hope you will consider it for publication.

Yours sincerely,

Raquel A. F. Neves