1. Introduction

Amorphous materials lie at the intersection of solids and liquids (Nicolas et al. Reference Nicolas, Ferrero, Martens and Barrat2018). Under small stresses, amorphous materials deform elastically, whereas under large stresses, they yield and start to flow plastically, and consequently they are also referred to as yield stress materials (Nicolas et al. Reference Nicolas, Ferrero, Martens and Barrat2018; Lin et al. Reference Lin, Lerner, Rosso and Wyart2014a ). In athermal amorphous materials such as dense granular suspensions, foams and emulsions, the effects of Brownian motion on the response of the material to deformation are negligible (Amon et al. Reference Amon, Bruand, Crassous and Clément2012). On the contrary, thermal fluctuations can play a key role in the dynamics of thermal amorphous materials such as colloidal gels, colloidal glasses and metallic glasses (Chattoraj, Caroli & Lemaître Reference Chattoraj, Caroli and Lemaître2010). The yielding transition has been extensively studied for athermal materials (Ritort & Sollich Reference Ritort and Sollich2003; Biroli & Bouchaud Reference Biroli and Bouchaud2012; Lin et al. Reference Lin, Gueudré, Rosso and Wyart2015; Ozawa et al. Reference Ozawa, Berthier, Biroli, Rosso and Tarjus2018). However, the origin of this transition and its connection to molecular-level information remains poorly understood, especially in thermal systems.

Unlike crystalline solids in which plasticity is a consequence of dislocations (Hill Reference Hill1998), amorphous materials are in an arrested, glassy state, and plasticity occurs through localized rearrangements of constituent particles as they break the cages created by their neighbours (Argon Reference Argon1979; Falk & Langer Reference Falk and Langer1998). More specifically, glassy materials have a rough free energy landscape meaning that the particles are in metastable configurations (energy wells) due to the presence of their neighbours. The particles can hop to another energy well by thermal activation. This is the underlying physics of trap models developed for glasses (Bouchaud Reference Bouchaud1992; Monthus & Bouchaud Reference Monthus and Bouchaud1996). Following in the footsteps of Monthus & Bouchaud (Reference Monthus and Bouchaud1996), Sollich et al. (Reference Sollich, Lequeux, Hébraud and Cates1997) developed the soft glassy rheology (SGR) model to incorporate elasticity into trap models and describe the rheology of foams and dense emulsions (so-called soft glassy materials (Dollet & Graner Reference Dollet and Graner2007; Dollet, Scagliarini & Sbragaglia Reference Dollet, Scagliarini and Sbragaglia2015)). This model divides the material into mesoscopic elements (each with a specific energy well and thus a yield threshold) and assumes that under mechanical loading, the elements (particles) deform elastically within their energy wells. This stored elastic energy reduces the energy barrier to hop. Since foams and emulsions are athermal, the yielding of elements is activated by the stress redistributed by the structural relaxation of other elements. This activation is modelled by an ad hoc noise temperature in the SGR model (Sollich et al. Reference Sollich, Lequeux, Hébraud and Cates1997; Sollich Reference Sollich1998). Hébraud & Lequeux (Reference Hébraud and Lequeux1998) further formalized the idea of dividing the material into mesoscopic elements leading to the emergence of numerous elastoplastic models (EPMs) which consider an elastic response, a local yield criterion, stress redistribution after yielding and a recovery of the local stress after a plastic event (Lin et al. Reference Lin, Lerner, Rosso and Wyart2014a ,Reference Lin, Saade, Lerner, Rosso and Wyart b , Reference Lin, Gueudré, Rosso and Wyart2015; Lin & Wyart Reference Lin and Wyart2016).

These models provide illuminating insights into the elasticity and the mechanical noise generated by plasticity in amorphous materials. However, they exhibit deficiencies in two significant regards: first, they are developed for athermal materials, while many amorphous materials have nanoscopic elements and activated dynamics, e.g. biological tissues (Bi et al. Reference Bi, Yang, Marchetti and Manning2016), cytoskeleton networks in living cells (Bursac et al. Reference Bursac, Lenormand, Fabry, Oliver, Weitz, Viasnoff, Butler and Fredberg2005), calcium-protein assembly in the casein matrix of cheese (Gillies Reference Gillies2019), nanofilms at fluid interfaces (Krishnaswamy & Sood Reference Krishnaswamy and Sood2010), among others. An activated version of the Hébraud–Lequeux model is proposed by Popović et al. (Reference Popović, de, Tom, Ji and Wyart2021), which shows that thermal fluctuations change the distribution of local stress, referred to as rounding of the yielding transition. They also proposed scaling laws for the yielding transition that were further analysed and explained by Ferrero, Kolton & Jagla (Reference Ferrero, Kolton and Jagla2021). Both of these studies, however, were limited to steady-state flows and applied stresses only slightly below the yield stress. Second, the currently available elastoplastic modelling only connects the mesoscopic properties (such as distribution of local stress, mechanical noise, etc.) to the bulk response while neglecting the molecular-level properties. This is despite the fact that the free energy landscape and the local barriers, which are a result of molecular-level information, dictate the dynamics of amorphous materials (Pica Ciamarra et al. Reference Ciamarra, Massimo and Wyart2024).

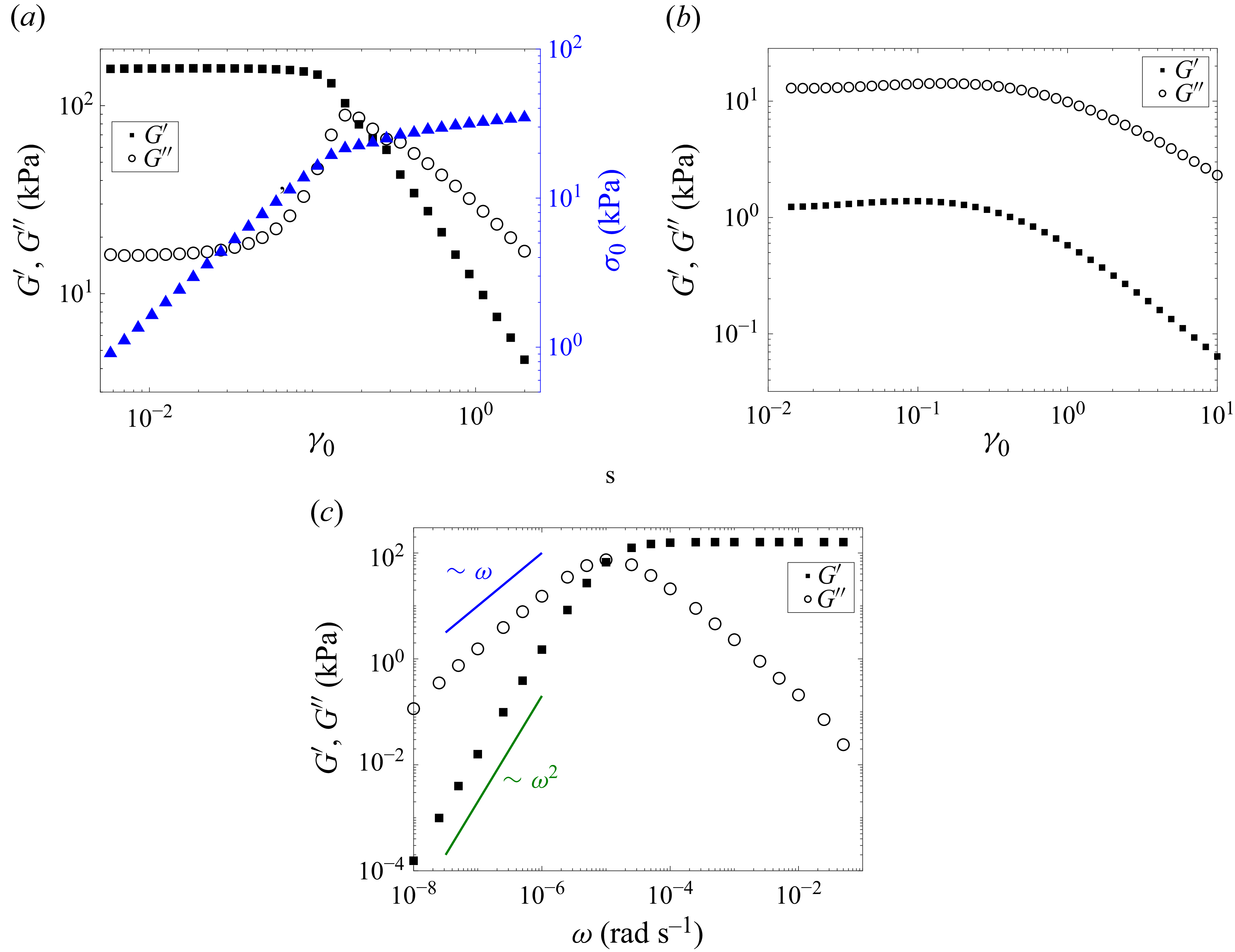

Unlike simple liquids, soft amorphous materials exhibit complex nonlinear rheology (Goyon et al. Reference Goyon, Colin, Ovarlez, Ajdari and Bocquet2008; Bonn et al. Reference Bonn, Denn, Berthier, Divoux and Manneville2017; Khabaz, Cloitre & Bonnecaze Reference Khabaz, Cloitre and Bonnecaze2020). Some common rheological features of these materials are: (i) a rate-dependent stress overshoot in the stress–strain curve of a start-up shear test depending on the initial state of the material and direction of the shear (Derec et al. Reference Derec, Ducouret, Ajdari and Lequeux2003; Moorcroft, Cates & Fielding Reference Moorcroft, Cates and Fielding2011); (ii) a peak in the loss modulus and a decrease in the storage modulus in a strain sweep test when an oscillatory shear strain is applied (Mason, Bibette & Weitz Reference Mason, Bibette and Weitz1995; Rogers et al. Reference Rogers, Erwin, Vlassopoulos and Cloitre2011; Dimitriou, Ewoldt & McKinley Reference Dimitriou, Ewoldt and McKinley2013); (iii) history-dependent behaviour (Khabaz et al. Reference Khabaz, Di, Flavio, Cloitre and Bonnecaze2021; Di Dio et al. Reference Di, Flavio, Khabaz, Bonnecaze and Cloitre2022); (iv) ageing (Liu, Martens & Barrat Reference Liu, Martens and Barrat2018; Parley, Fielding & Sollich Reference Parley, Fielding and Sollich2020); (v) shear banding (Kabla, Scheibert & Debregeas Reference Kabla, Scheibert and Debregeas2007; Coussot & Ovarlez Reference Coussot and Ovarlez2010; Fielding Reference Fielding2014), among others. The SGR model can qualitatively reproduce these rheological features for athermal amorphous materials by changing the parameters of the model (Fielding et al. Reference Fielding, Sollich and Cates2000, Reference Fielding, Cates and Sollich2009). Quantitative agreement between the model and experiments might be achieved provided that the model is linked to molecular-level information about the material to achieve physical and meaningful values for the parameters.

An important question is how the presence of thermal fluctuations affects this nonlinear rheology. The first consideration when including the thermal fluctuations is the time scale of thermally activated structural relaxations (

![]() $\tau _{\textit{th}}$

) that competes with the time scale of mechanical loading (

$\tau _{\textit{th}}$

) that competes with the time scale of mechanical loading (

![]() $1/\dot \gamma$

). Further richness may arise when one considers a time scale for plasticity (single rearrangement) (Ferrero, Martens & Barrat Reference Ferrero, Martens and Barrat2014) and a time scale for avalanches of rearrangements (multiple plastic events which are triggered by an initial event) (Nicolas et al. Reference Nicolas, Puosi, Mizuno and Barrat2015). The complex interplay between mechanical loading and thermal fluctuations might completely alter both transient and steady-state responses, depending on the system under deformation. For example, the flow curve, indicating the stress as a function of shear rate in steady shear, in athermal amorphous materials usually follows a Herschel–Bulkley law (Lin et al. Reference Lin, Lerner, Rosso and Wyart2014a

; Sen, Morales & Ewoldt Reference Sen, Morales and Ewoldt2020), while at vanishing shear rates, thermal fluctuations give rise to a Newtonian stress instead of a stress plateau in dense colloidal suspensions (Fuchs & Cates Reference Fuchs and Cates2002). Furthermore, molecular dynamics simulations of a two-dimensional Lennard-Jones glass (Chattoraj et al. Reference Chattoraj, Caroli and Lemaître2010) and thermally activated creep tests using kinetic Monte Carlo simulations on a square lattice (Merabia & Detcheverry Reference Merabia and Detcheverry2016) show that thermal fluctuations introduce a logarithmic dependence of the steady-state stress on the shear rate. An activated version of the Hébraud–Lequeux model also predicts a logarithmic flow curve for large stresses just below the yield stress in the limit of small temperatures (Popović et al. Reference Popović, de, Tom, Ji and Wyart2021). Prior studies on the role of thermal fluctuations in amorphous materials have only focused on steady-state situations under large applied deformation. However, thermal amorphous materials can flow over a long time scale even under very small deformation while showing solid-like behaviour on limited time scales (Schröter & Donth Reference Schröter and Donth2000; Lu, Ravichandran & Johnson Reference Lu, Ravichandran and Johnson2003; Agarwal, Qi & Archer Reference Agarwal, Qi and Archer2010; Riechers et al. Reference Riechers, Das, Rashidi, Dufresne and Maaß2025). A comprehensive theoretical understanding of the intricate physics governing this complex behaviour is yet to be established. Thus, to better understand and characterize the combined effects of mechanical loading and thermal fluctuations on both the transient and steady-state rheology, it is essential to have a thermally activated constitutive model. To test the model, it would be crucial to study a well-characterized thermal amorphous material.

$1/\dot \gamma$

). Further richness may arise when one considers a time scale for plasticity (single rearrangement) (Ferrero, Martens & Barrat Reference Ferrero, Martens and Barrat2014) and a time scale for avalanches of rearrangements (multiple plastic events which are triggered by an initial event) (Nicolas et al. Reference Nicolas, Puosi, Mizuno and Barrat2015). The complex interplay between mechanical loading and thermal fluctuations might completely alter both transient and steady-state responses, depending on the system under deformation. For example, the flow curve, indicating the stress as a function of shear rate in steady shear, in athermal amorphous materials usually follows a Herschel–Bulkley law (Lin et al. Reference Lin, Lerner, Rosso and Wyart2014a

; Sen, Morales & Ewoldt Reference Sen, Morales and Ewoldt2020), while at vanishing shear rates, thermal fluctuations give rise to a Newtonian stress instead of a stress plateau in dense colloidal suspensions (Fuchs & Cates Reference Fuchs and Cates2002). Furthermore, molecular dynamics simulations of a two-dimensional Lennard-Jones glass (Chattoraj et al. Reference Chattoraj, Caroli and Lemaître2010) and thermally activated creep tests using kinetic Monte Carlo simulations on a square lattice (Merabia & Detcheverry Reference Merabia and Detcheverry2016) show that thermal fluctuations introduce a logarithmic dependence of the steady-state stress on the shear rate. An activated version of the Hébraud–Lequeux model also predicts a logarithmic flow curve for large stresses just below the yield stress in the limit of small temperatures (Popović et al. Reference Popović, de, Tom, Ji and Wyart2021). Prior studies on the role of thermal fluctuations in amorphous materials have only focused on steady-state situations under large applied deformation. However, thermal amorphous materials can flow over a long time scale even under very small deformation while showing solid-like behaviour on limited time scales (Schröter & Donth Reference Schröter and Donth2000; Lu, Ravichandran & Johnson Reference Lu, Ravichandran and Johnson2003; Agarwal, Qi & Archer Reference Agarwal, Qi and Archer2010; Riechers et al. Reference Riechers, Das, Rashidi, Dufresne and Maaß2025). A comprehensive theoretical understanding of the intricate physics governing this complex behaviour is yet to be established. Thus, to better understand and characterize the combined effects of mechanical loading and thermal fluctuations on both the transient and steady-state rheology, it is essential to have a thermally activated constitutive model. To test the model, it would be crucial to study a well-characterized thermal amorphous material.

As a class of polymer nanocomposites and a promising thermal model material, self-suspended polymer-grafted nanoparticles consist of hard inorganic nanocores densely grafted with polymer chains. Even in the absence of a dispersing medium, these polymer-grafted nanoparticles can exhibit fluid behaviour as the grafted polymers fill the interstitial space between the cores like an incompressible fluid (Bourlinos et al. Reference Bourlinos, Herrera, Chalkias, Jiang, Zhang, Archer and Giannelis2005a , Reference Bourlinos, Ray Chowdhury, Herrera, Jiang, Zhang, Archer and Giannelisb ; Rodriguez et al. Reference Rodriguez, Herrera, Archer and Giannelis2008). Strong van der Waals forces usually lead to irreversible aggregation of nanoscale suspensions making the material properties unpredictable (Russel et al. Reference Russel, Russel, Saville and Schowalter1991). However, polymer-grafted nanoparticles are a novel class of polymer nanocomposites in which particle aggregation is suppressed since the configurational entropy of the grafted polymers is much greater than the van der Waals interactions between the cores (Yu & Koch Reference Yu and Koch2010; Chremos et al. Reference Chremos, Panagiotopoulos, Yu and Koch2011; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Srivastava, Archer and Koch2014).

Experiments have shown that due to the interactions of the grafted polymers, solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles exhibit rheological characteristics similar to those of soft glassy materials, e.g. slow dynamics, yield stress, rate-dependent behaviour (Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Qi and Archer2010; Agarwal & Archer Reference Agarwal and Archer2011; Srivastava et al. Reference Srivastava, Shin and Archer2012b

). This stems from the cooperation of the grafted polymers to fill the interstitial space which creates local cages around the nanocores. More specifically, in solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles, the entropy of the space-filling grafted polymers controls the core configuration, and there is a large energy penalty to alter this configuration. Thus, solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles are in arrested states and relax very slowly exhibiting an apparent yield stress over extended time periods (Agarwal, Srivastava & Archer Reference Agarwal, Srivastava and Archer2011; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Utomo, Zhao, Zheng, Zhang and Archer2020). Interestingly, polymer-grafted nanoparticles can display glassy behaviour at very low core volume fraction (

![]() $\phi \approx 0.1{-}0.2$

) (Yu & Koch Reference Yu and Koch2014; Srivastava et al. Reference Srivastava, Choudhury, Agrawal and Archer2017), which allows thermal fluctuations to relax their nanostructures towards local equilibrium states. This is in contrast to dense colloidal suspensions in which the large particle volume fraction prevents thermal relaxation to a local equilibrium state (Nazockdast & Morris Reference Nazockdast and Morris2012; Lu & Weitz Reference Lu and Weitz2013). Understanding the complex rheology of a thermal amorphous materials like polymer-grafted nanoparticles requires knowledge of the molecular-level physics.

$\phi \approx 0.1{-}0.2$

) (Yu & Koch Reference Yu and Koch2014; Srivastava et al. Reference Srivastava, Choudhury, Agrawal and Archer2017), which allows thermal fluctuations to relax their nanostructures towards local equilibrium states. This is in contrast to dense colloidal suspensions in which the large particle volume fraction prevents thermal relaxation to a local equilibrium state (Nazockdast & Morris Reference Nazockdast and Morris2012; Lu & Weitz Reference Lu and Weitz2013). Understanding the complex rheology of a thermal amorphous materials like polymer-grafted nanoparticles requires knowledge of the molecular-level physics.

Theoretical calculations (Yu & Koch Reference Yu and Koch2010) and scattering experiments (Bourlinos et al. Reference Bourlinos, Ray Chowdhury, Herrera, Jiang, Zhang, Archer and Giannelis2005b ; Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Qi and Archer2010) have shown that the grafted polymers in solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles act as an incompressible fluid, indicating that each core and its tethered polymers must exclude exactly one neighbouring core and its tethered polymers. This means that each particle carries its own share of the fluid attached to it making monodisperse, solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles an incompressible single-component fluid for which the static structure factor at zero wavenumber is theoretically zero (Yu & Koch Reference Yu and Koch2010). Small angle X-ray scattering experiments on these materials show that due to polydispersity in core size, polymer molecular weight and grafting density, the static structure factor at zero wavenumber is slightly above zero but still substantially smaller than that for a hard-sphere suspension with the same core volume fraction. This means that long-range density fluctuations in solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles are suppressed, making them disordered hyperuniform materials as the grafted polymers uniformly fill the interstitial space between the cores (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Srivastava, Archer and Koch2014; Chremos & Douglas Reference Chremos and Douglas2018). This cooperation between grafted polymers to fill the space leads to a non-pairwise-additive interparticle potential, interpenetration of polymer brushes from neighbouring particles, creation of cages around the cores and slowing-down of the relaxation dynamics (Yu & Koch Reference Yu and Koch2010; Goyal & Escobedo Reference Goyal and Escobedo2011; Chremos, Panagiotopoulos & Koch Reference Chremos, Panagiotopoulos and Koch2012). As a result, the incompressibility constraint alters the probability distribution of the grafted polymers and thus their free energy (Tai, Pan & Yu Reference Tai, Pan and Yu2019). Generally, the probability distribution of surface-tethered polymers can be obtained by using a self-consistent field theory (SCFT) (Park et al. Reference Park, Kim, Yong, Choe, Bang and Kim2018), polymer reference interaction site model (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Gartner, Jones, Snyder and Jayaraman2018), classical density functional theory (DFT) (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Tang, Qiu and Shi2015), molecular dynamics (Chang & Yu Reference Chang and Yu2021) or Monte Carlo (Ohno et al. Reference Ohno, Sakamoto, Minagawa and Okabe2007) simulations. Among these techniques, the polymer SCFT (Matsen Reference Matsen2002) and classical DFT (Yu & Koch Reference Yu and Koch2013) can effectively impose the incompressibility constraint and capture the entropic interactions between the grafted polymers. However, modelling an incompressibility constraint with polymer SCFT is numerically challenging as it results in solving a set of stiff integrodifferential equations, while classical DFT is more analytically favourable (Tai et al. Reference Tai, Pan and Yu2019).

In this paper, we first focus on thermodynamics at the molecular scale and study how the free energy of the nanostructure evolves under deformation using a classical DFT discussed in § 2. The outcome will be the free energy landscape of a solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticle system as a function of material properties such as core volume fraction, and molecular weight and grafting density of the polymers. In § 3, a thermally activated SGR model is proposed which takes the free energy landscape as an input and connects the thermodynamics to the bulk rheology of the material. In § 4, we delve into the molecular-level information and explain that the shape of the energy well is an outcome of the competition between the translational and configurational entropy of the grafted polymers. In § 5, we note that depending on the energy landscape and the rate of deformation, structural rearrangements activated by thermal hops can regulate the macroscopic rheology. Furthermore, a detailed characterization of the interplay between mechanical loading and thermal fluctuations is provided by modelling different shear tests and including a deformation history.

2. A classical DFT

We model the polymer chains as beads–springs tethered to the surface of the cores and assume linear and massless springs with zero rest length. The spring energy is defined as

![]() $F_{\textit{spring}} = ({1}/{2}) \xi x^2$

where

$F_{\textit{spring}} = ({1}/{2}) \xi x^2$

where

![]() $\xi$

is the spring constant and

$\xi$

is the spring constant and

![]() $x$

is the displacement of the spring from its rest length. The spring constant is chosen to be related to the radius of gyration,

$x$

is the displacement of the spring from its rest length. The spring constant is chosen to be related to the radius of gyration,

![]() $R_g$

, of an ideal, unattached linear chain as

$R_g$

, of an ideal, unattached linear chain as

![]() $\xi = ({k_{\!B} T}/{2R_g^2})$

, where

$\xi = ({k_{\!B} T}/{2R_g^2})$

, where

![]() $k_{\!B}$

is the Boltzmann constant and

$k_{\!B}$

is the Boltzmann constant and

![]() $T$

is the temperature. The spring energy models the configurational entropy of an ideal chain. To achieve the relaxation of the core configuration, all the grafted polymers have to move, whereas for polymer relaxation, only one polymer has to move. As a result, we assume that polymers are at equilibrium since they can relax much faster than the cores. Previous studies have tested the validity of these assumptions (Yu & Koch Reference Yu and Koch2010; Chremos et al. Reference Chremos, Panagiotopoulos, Yu and Koch2011; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Srivastava, Archer and Koch2014; Tai et al. Reference Tai, Pan and Yu2019). For solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles, the free energy of the grafted polymers includes the entropy of the beads and the spring energy of the chains. Furthermore, the incompressibility condition is imposed by requiring all the grafted polymers to uniformly fill the interstitial space. Thus, the total free energy,

$T$

is the temperature. The spring energy models the configurational entropy of an ideal chain. To achieve the relaxation of the core configuration, all the grafted polymers have to move, whereas for polymer relaxation, only one polymer has to move. As a result, we assume that polymers are at equilibrium since they can relax much faster than the cores. Previous studies have tested the validity of these assumptions (Yu & Koch Reference Yu and Koch2010; Chremos et al. Reference Chremos, Panagiotopoulos, Yu and Koch2011; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Srivastava, Archer and Koch2014; Tai et al. Reference Tai, Pan and Yu2019). For solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles, the free energy of the grafted polymers includes the entropy of the beads and the spring energy of the chains. Furthermore, the incompressibility condition is imposed by requiring all the grafted polymers to uniformly fill the interstitial space. Thus, the total free energy,

![]() $F$

, of the polymers can be written as

$F$

, of the polymers can be written as

\begin{align} \frac {F}{k_{\textit{B}}T} = \int _V \int _A \left [P(\boldsymbol{r},\boldsymbol{r_0}) \big [\ln \big (P(\boldsymbol{r},\boldsymbol{r_0})\varLambda _b^3 \big ) - 1 \big ] + P(\boldsymbol{r},\boldsymbol{r_0})\frac {|\boldsymbol{r}-\boldsymbol{r}_0|^2}{4R_g^2}\right ] {\text{d}}\boldsymbol{r}_0 \, {\text{d}}\boldsymbol{r} \notag \\ + \dfrac {\alpha }{2}\int _V \, \left (n(\boldsymbol{r})-n_0 \right )^2 {\text{d}}\boldsymbol{r}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {F}{k_{\textit{B}}T} = \int _V \int _A \left [P(\boldsymbol{r},\boldsymbol{r_0}) \big [\ln \big (P(\boldsymbol{r},\boldsymbol{r_0})\varLambda _b^3 \big ) - 1 \big ] + P(\boldsymbol{r},\boldsymbol{r_0})\frac {|\boldsymbol{r}-\boldsymbol{r}_0|^2}{4R_g^2}\right ] {\text{d}}\boldsymbol{r}_0 \, {\text{d}}\boldsymbol{r} \notag \\ + \dfrac {\alpha }{2}\int _V \, \left (n(\boldsymbol{r})-n_0 \right )^2 {\text{d}}\boldsymbol{r}. \end{align}

In the above formulation,

![]() $P(\boldsymbol{r},\boldsymbol{r}_0)$

is the probability density of finding a polymer bead position

$P(\boldsymbol{r},\boldsymbol{r}_0)$

is the probability density of finding a polymer bead position

![]() $\boldsymbol{r}$

provided that it is grafted at a position

$\boldsymbol{r}$

provided that it is grafted at a position

![]() $\boldsymbol{r}_0$

on the particle surface. Therefore, the integrals over

$\boldsymbol{r}_0$

on the particle surface. Therefore, the integrals over

![]() $\boldsymbol{r}$

and

$\boldsymbol{r}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{r}_0$

are integrals over volume (denoted by

$\boldsymbol{r}_0$

are integrals over volume (denoted by

![]() $V$

) of the system and over the surface (denoted by

$V$

) of the system and over the surface (denoted by

![]() $A$

) of the cores, respectively. All the lengths are non-dimensionalized by the diameter of the cores,

$A$

) of the cores, respectively. All the lengths are non-dimensionalized by the diameter of the cores,

![]() $d$

. In the first integral, the first term is the ideal gas Helmholtz free energy of the beads which models the translational entropy of the polymers where

$d$

. In the first integral, the first term is the ideal gas Helmholtz free energy of the beads which models the translational entropy of the polymers where

![]() $\varLambda _b$

is the thermal de Broglie wavelength of the monomer beads, and the second term represents the spring energy of the grafted polymers which models the configurational entropy of the polymer chains. The last term is the space-filling (incompressibility) constraint. The number density,

$\varLambda _b$

is the thermal de Broglie wavelength of the monomer beads, and the second term represents the spring energy of the grafted polymers which models the configurational entropy of the polymer chains. The last term is the space-filling (incompressibility) constraint. The number density,

![]() $n(\boldsymbol{r})$

, of the grafted polymers at every point in the void space is given by

$n(\boldsymbol{r})$

, of the grafted polymers at every point in the void space is given by

and

![]() $n_0$

is the mean number density of the grafted polymers defined as

$n_0$

is the mean number density of the grafted polymers defined as

![]() $n_0 = {N}/{V_{v\textit{oid}}}$

, where

$n_0 = {N}/{V_{v\textit{oid}}}$

, where

![]() $N$

is the total number of chains and

$N$

is the total number of chains and

![]() $V_{v\textit{oid}}$

is the void volume in the system. We impose the space-filling constraint as a free energy penalty term by defining a space-filling parameter,

$V_{v\textit{oid}}$

is the void volume in the system. We impose the space-filling constraint as a free energy penalty term by defining a space-filling parameter,

![]() $\alpha$

. When

$\alpha$

. When

![]() $\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

, there is a very large free energy penalty for having a number density at any point in space that differs from the mean value. This corresponds to a solvent-free case in which the tethered polymers are modelled as an incompressible fluid. The case

$\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

, there is a very large free energy penalty for having a number density at any point in space that differs from the mean value. This corresponds to a solvent-free case in which the tethered polymers are modelled as an incompressible fluid. The case

![]() $\alpha =0$

can be viewed as a system with excess implicit, theta solvent. Here, there is no requirement for the grafted polymers to fill the void space, because we assume that the void volume is occupied primarily by the solvent. By choosing a reference state consisting of excess theta solvent, we omit considerations of the excluded volume interactions that lead to extended brush heights at large polymer grafting densities (Alexander Reference Alexander1977; de Gennes Reference de Gennes1980). For intermediate values of

$\alpha =0$

can be viewed as a system with excess implicit, theta solvent. Here, there is no requirement for the grafted polymers to fill the void space, because we assume that the void volume is occupied primarily by the solvent. By choosing a reference state consisting of excess theta solvent, we omit considerations of the excluded volume interactions that lead to extended brush heights at large polymer grafting densities (Alexander Reference Alexander1977; de Gennes Reference de Gennes1980). For intermediate values of

![]() $\alpha$

, we can view the energy penalty modelling the finite compressibility of tethered polymers in a solvent-free system. This form of the energy penalty is related to the free energy variation of a Lennard-Jones liquid of monomer beads (Betancourt-Cárdenas et al. Reference Betancourt-Cárdenas, Galicia-Luna and Sandler2008; Chremos et al. Reference Chremos, Panagiotopoulos, Yu and Koch2011) with

$\alpha$

, we can view the energy penalty modelling the finite compressibility of tethered polymers in a solvent-free system. This form of the energy penalty is related to the free energy variation of a Lennard-Jones liquid of monomer beads (Betancourt-Cárdenas et al. Reference Betancourt-Cárdenas, Galicia-Luna and Sandler2008; Chremos et al. Reference Chremos, Panagiotopoulos, Yu and Koch2011) with

![]() $\alpha$

being related to the ratio of the interbead potential to the thermal energy. In a typical liquid, the attractive and repulsive potential forces maintain nearly constant molecular density so that typical values of

$\alpha$

being related to the ratio of the interbead potential to the thermal energy. In a typical liquid, the attractive and repulsive potential forces maintain nearly constant molecular density so that typical values of

![]() $\alpha$

are very large but not infinite. In this case, the incompressibility constraint replaces considerations of monomer excluded volume typically included in solvent-swollen polymer brushes (Alexander Reference Alexander1977; de Gennes Reference de Gennes1980). By minimizing the free energy, we can find the probability density of the grafted polymers at equilibrium,

$\alpha$

are very large but not infinite. In this case, the incompressibility constraint replaces considerations of monomer excluded volume typically included in solvent-swollen polymer brushes (Alexander Reference Alexander1977; de Gennes Reference de Gennes1980). By minimizing the free energy, we can find the probability density of the grafted polymers at equilibrium,

\begin{equation} \frac {\delta\! F}{\delta\! P} = 0 \rightarrow P(\boldsymbol{r},\boldsymbol{r}_0) = K(\boldsymbol{r}_0)\exp\! {\left [\!-\frac {|\boldsymbol{r}-\boldsymbol{r}_0|^2}{4R_g^2}\right ]} \exp {[-\alpha (n(\boldsymbol{r})-n_0)]} ,\end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac {\delta\! F}{\delta\! P} = 0 \rightarrow P(\boldsymbol{r},\boldsymbol{r}_0) = K(\boldsymbol{r}_0)\exp\! {\left [\!-\frac {|\boldsymbol{r}-\boldsymbol{r}_0|^2}{4R_g^2}\right ]} \exp {[-\alpha (n(\boldsymbol{r})-n_0)]} ,\end{equation}

where

![]() $K(\boldsymbol{r}_0)$

is a normalization coefficient related to the grafting density of the polymers, given by

$K(\boldsymbol{r}_0)$

is a normalization coefficient related to the grafting density of the polymers, given by

Polymer-grafted nanoparticles are usually made of silica nanocores with a diameter of

![]() $d \approx 5{-}10 \, \mathrm{nm}$

and polyethylene glycol (PEG) as the grafted polymer (Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Qi and Archer2010; Srivastava et al. Reference Srivastava, Agarwal and Archer2012a

). A schematic of an arbitrary configuration of solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles and the bead–spring representation of the grafted polymers are shown in figure 1(a) and 1(b), respectively. We obtain the free energy landscape by shearing the system of nanocores and grafted polymers, and at each strain, we calculate the free energy of the system. This requires solving a highly coupled system of equations for the probability density and number density for every point in the space, at each strain and for each value of the space-filling parameter. Furthermore, to study the effect of material properties like core volume fraction, polymer molecular weight, etc., we have to repeat this procedure. Therefore, it is computationally expensive to solve this system multiple times for millions of polymer-grafted particles in a real sample. To ameliorate this situation, we consider a face-centred-cubic (FCC) arrangement of the cores, shown in figure 1(c), to limit the calculations to a unit cell by using periodic boundary conditions. This calculation is used to estimate the typical energy barrier to rearrange the local configuration of a nanoparticle and its neighbours. This energy barrier can then be placed into an EPM designed to approximately describe the rheology of amorphous materials to provide predictions that incorporate molecular-scale information. As mentioned previously, in the solvent-free case, each particle carries an equal amount of the grafted polymeric fluid. This leads to a disordered structure but with equal Voronoi volumes around each particle (Singh, Walsh & Koch Reference Singh, Walsh and Koch2015). The FCC lattice provides equal Voronoi volumes but in an ordered structure.

$d \approx 5{-}10 \, \mathrm{nm}$

and polyethylene glycol (PEG) as the grafted polymer (Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Qi and Archer2010; Srivastava et al. Reference Srivastava, Agarwal and Archer2012a

). A schematic of an arbitrary configuration of solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles and the bead–spring representation of the grafted polymers are shown in figure 1(a) and 1(b), respectively. We obtain the free energy landscape by shearing the system of nanocores and grafted polymers, and at each strain, we calculate the free energy of the system. This requires solving a highly coupled system of equations for the probability density and number density for every point in the space, at each strain and for each value of the space-filling parameter. Furthermore, to study the effect of material properties like core volume fraction, polymer molecular weight, etc., we have to repeat this procedure. Therefore, it is computationally expensive to solve this system multiple times for millions of polymer-grafted particles in a real sample. To ameliorate this situation, we consider a face-centred-cubic (FCC) arrangement of the cores, shown in figure 1(c), to limit the calculations to a unit cell by using periodic boundary conditions. This calculation is used to estimate the typical energy barrier to rearrange the local configuration of a nanoparticle and its neighbours. This energy barrier can then be placed into an EPM designed to approximately describe the rheology of amorphous materials to provide predictions that incorporate molecular-scale information. As mentioned previously, in the solvent-free case, each particle carries an equal amount of the grafted polymeric fluid. This leads to a disordered structure but with equal Voronoi volumes around each particle (Singh, Walsh & Koch Reference Singh, Walsh and Koch2015). The FCC lattice provides equal Voronoi volumes but in an ordered structure.

Figure 1. (a) A schematic of a random configuration of polymer-grafted nanoparticles. For clarity, only a few grafted chains per nanocore are illustrated. (b) A schematic of solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles with the bead–spring model under shear deformation. (c) The FCC arrangement assumed for the nanocores.

Due to the impenetrability of the cores, we exclude the space inside the nanocores from the volume integrals (polymers are grafted to the surface of the cores). For computational convenience, we model the impenetrability of the cores using a soft potential such that the integrands become zero inside the cores. As

![]() $\alpha$

increases, the problem becomes more stiff and as a result is more prone to instabilities. To solve for

$\alpha$

increases, the problem becomes more stiff and as a result is more prone to instabilities. To solve for

![]() $\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

, we use the solution for

$\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

, we use the solution for

![]() $\alpha =0$

as an initial guess and then gradually increase

$\alpha =0$

as an initial guess and then gradually increase

![]() $\alpha$

and use the solution for each

$\alpha$

and use the solution for each

![]() $\alpha$

as the initial guess for the next

$\alpha$

as the initial guess for the next

![]() $\alpha$

. Another important point to ensure stability of the calculations is to use under-relaxation to update the solution. It is worth mentioning that a fourth-order accurate, six-point quadrature rule in three dimensions is used for the volume integrals (Hughes Reference Hughes2003) and Lebedev quadrature rule is used for the surface integrals over the spherical particles (Ericson & Zinoviev Reference Ericson and Zinoviev2001).

$\alpha$

. Another important point to ensure stability of the calculations is to use under-relaxation to update the solution. It is worth mentioning that a fourth-order accurate, six-point quadrature rule in three dimensions is used for the volume integrals (Hughes Reference Hughes2003) and Lebedev quadrature rule is used for the surface integrals over the spherical particles (Ericson & Zinoviev Reference Ericson and Zinoviev2001).

3. Thermal SGR model

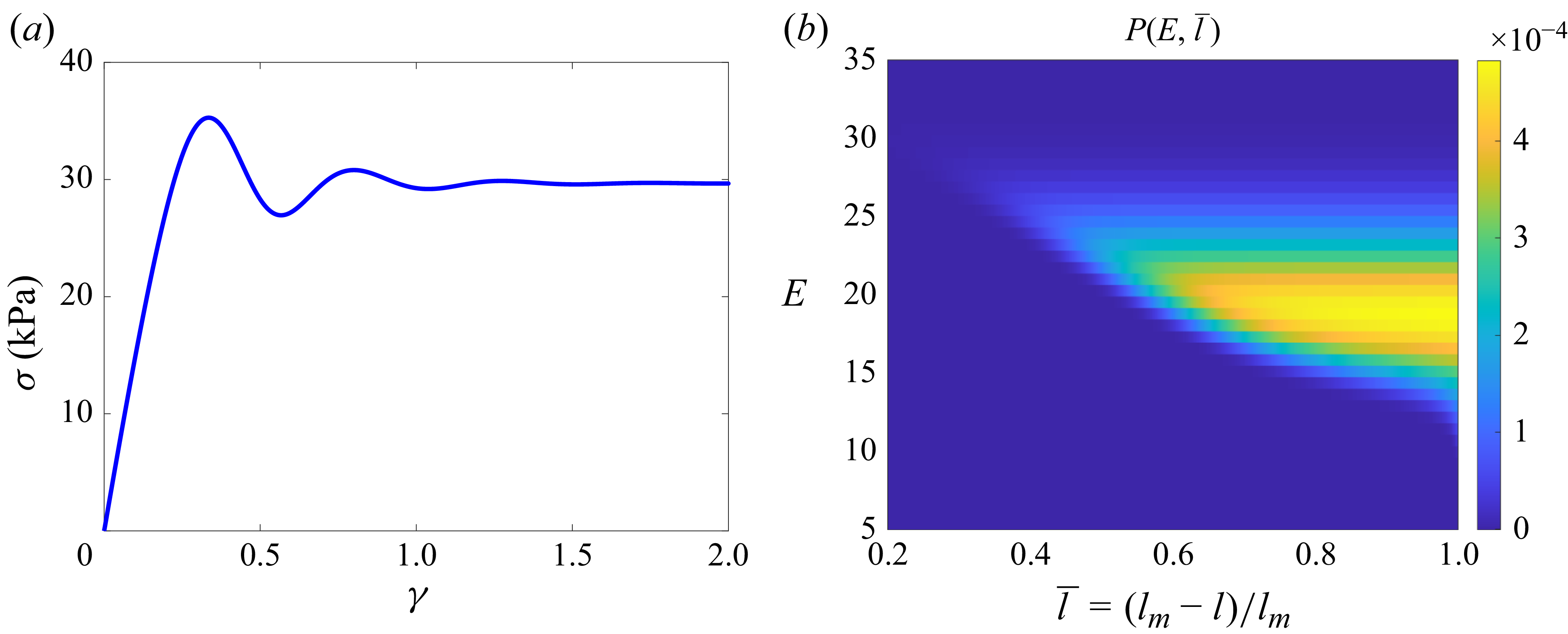

In the last section, we elaborated on how to obtain the free energy as a function of the applied shear strain. The output will be the energy landscape and the corresponding energy barrier to structural relaxation. In this section, we connect the obtained energy landscape to the bulk rheology by introducing a thermal SGR model. Similar to the original SGR model, we conceptually divide the material into a large number of mesoscopic elements and assign a local scalar strain (and thus a local stress) and a local yield energy to each element (Sollich et al. Reference Sollich, Lequeux, Hébraud and Cates1997; Sollich Reference Sollich1998). The elements are sheared with the same rate as the macroscopic shear rate, and they store elastic energy. Mechanical loading reduces the energy barrier thus facilitating hops out of the trap by thermal fluctuations, which we call a thermally induced microstructural relaxation. Therefore, the energy barrier to hop at each local strain,

![]() $l$

, is equal to

$l$

, is equal to

![]() $\mathcal{R} = E-F(l)$

, where

$\mathcal{R} = E-F(l)$

, where

![]() $F(l)$

is the locally stored elastic energy at strain

$F(l)$

is the locally stored elastic energy at strain

![]() $l$

, and

$l$

, and

![]() $E$

is the local yield energy (the maximum energy barrier) both of which are predicted by our DFT calculations. We use this energy barrier,

$E$

is the local yield energy (the maximum energy barrier) both of which are predicted by our DFT calculations. We use this energy barrier,

![]() $\mathcal{R}$

, as the activation energy for an Arrhenius law to predict the rate of thermal hops. We assume that elements mechanically yield once

$\mathcal{R}$

, as the activation energy for an Arrhenius law to predict the rate of thermal hops. We assume that elements mechanically yield once

![]() $F(l)\geqslant E$

, similar to the local yield criterion in athermal EPMs. After relaxation, whether mechanical or thermal, the elements rearrange to a new configuration corresponding to a new energy well and zero local strain. Thus, the probability,

$F(l)\geqslant E$

, similar to the local yield criterion in athermal EPMs. After relaxation, whether mechanical or thermal, the elements rearrange to a new configuration corresponding to a new energy well and zero local strain. Thus, the probability,

![]() $P(E,l,t)$

of having an element with a local strain

$P(E,l,t)$

of having an element with a local strain

![]() $l$

and yield energy

$l$

and yield energy

![]() $E$

at time

$E$

at time

![]() $t$

evolves as the following:

$t$

evolves as the following:

The first term on the right-hand side represents the elastic deformation with the applied macroscopic shear rate,

![]() $\dot \gamma$

. The second term is the thermally activated relaxation, and

$\dot \gamma$

. The second term is the thermally activated relaxation, and

![]() $\varGamma _0$

is the attempt frequency for hopping. The third term is the mechanical relaxation. Here

$\varGamma _0$

is the attempt frequency for hopping. The third term is the mechanical relaxation. Here

![]() $\mathcal{H}$

is the Heaviside function denoting that once the entire local barrier is surmounted, the element relaxes over a time scale of

$\mathcal{H}$

is the Heaviside function denoting that once the entire local barrier is surmounted, the element relaxes over a time scale of

![]() $1/\varGamma _m$

. Finally, the last term is the rearrangement of elements after yielding to a new configuration which is unstrained and randomly chosen from the distribution of energy wells,

$1/\varGamma _m$

. Finally, the last term is the rearrangement of elements after yielding to a new configuration which is unstrained and randomly chosen from the distribution of energy wells,

![]() $\rho (E)$

. The prefactor is the total yielding rate which is the average of local yielding rates:

$\rho (E)$

. The prefactor is the total yielding rate which is the average of local yielding rates:

The stress response of the material,

![]() $\sigma (t)$

, is the average over all the local stresses,

$\sigma (t)$

, is the average over all the local stresses,

![]() $\sigma _{\textit{loc}}$

, multiplied by the number density of the particles,

$\sigma _{\textit{loc}}$

, multiplied by the number density of the particles,

![]() $n_c$

, as the following:

$n_c$

, as the following:

We take each core with its attached polymers as an element of the thermal SGR model. Also, we calculate the local stresses as

![]() $\sigma _{\textit{loc}} = ({d\!F}/{dl})$

from the locally stored elastic energies. The thermal SGR model is connected to our free energy calculations through the energy landscape. Since we used a FCC arrangement in our DFT calculations, the energy landscape has only one unique energy well, and thus

$\sigma _{\textit{loc}} = ({d\!F}/{dl})$

from the locally stored elastic energies. The thermal SGR model is connected to our free energy calculations through the energy landscape. Since we used a FCC arrangement in our DFT calculations, the energy landscape has only one unique energy well, and thus

![]() $\rho (E) = \delta (E-E_0)$

with

$\rho (E) = \delta (E-E_0)$

with

![]() $E_0$

being the depth of the single energy well in the landscape. This single-well assumption allows us to probe the effect of thermal fluctuations on the rheology as the only factor to produce a steady-state response. We also use a Gaussian distribution of the yield energies to account for heterogeneity in the energy landscape. A Gaussian distribution of yield energies is assumed in polymer glasses (Hasan & Boyce Reference Hasan and Boyce1995), supercooled liquids (Xia & Wolynes Reference Xia and Wolynes2001), metallic glasses (Schirmacher, Ruocco & Mazzone Reference Schirmacher, Ruocco and Mazzone2015) and active cytoskeletal networks (Woillez, Kafri & Gov Reference Woillez, Kafri and Gov2020). Also, a Gaussian distribution of yield energies is argued to result in stretched exponential relaxations (Monthus & Bouchaud Reference Monthus and Bouchaud1996; Xia & Wolynes Reference Xia and Wolynes2001), which are observed experimentally in solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles (Agarwal & Archer Reference Agarwal and Archer2011).

$E_0$

being the depth of the single energy well in the landscape. This single-well assumption allows us to probe the effect of thermal fluctuations on the rheology as the only factor to produce a steady-state response. We also use a Gaussian distribution of the yield energies to account for heterogeneity in the energy landscape. A Gaussian distribution of yield energies is assumed in polymer glasses (Hasan & Boyce Reference Hasan and Boyce1995), supercooled liquids (Xia & Wolynes Reference Xia and Wolynes2001), metallic glasses (Schirmacher, Ruocco & Mazzone Reference Schirmacher, Ruocco and Mazzone2015) and active cytoskeletal networks (Woillez, Kafri & Gov Reference Woillez, Kafri and Gov2020). Also, a Gaussian distribution of yield energies is argued to result in stretched exponential relaxations (Monthus & Bouchaud Reference Monthus and Bouchaud1996; Xia & Wolynes Reference Xia and Wolynes2001), which are observed experimentally in solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles (Agarwal & Archer Reference Agarwal and Archer2011).

To achieve thermally induced structural relaxation, the particle has to diffuse some distance to change its neighbours. The attempt frequency,

![]() $\varGamma _0$

, for hopping that is the inverse of the bare hopping time,

$\varGamma _0$

, for hopping that is the inverse of the bare hopping time,

![]() $\tau _0$

, is calculated as

$\tau _0$

, is calculated as

![]() $\varGamma _0 = D/h^2$

, where

$\varGamma _0 = D/h^2$

, where

![]() $D$

is a diffusion coefficient and

$D$

is a diffusion coefficient and

![]() $h$

is the interparticle distance between the cores. The diffusion coefficient is approximated by the Stokes–Einstein relation for a single particle diffusing through a polymer melt with the same molecular weight as the grafted polymers. Therefore, this formulation connects the attempt frequency to the core particle radius, the polymer molecular weight and the core volume fraction. An increase in the polymer molecular weight leads to an increase in the viscosity of the polymer melt,

$h$

is the interparticle distance between the cores. The diffusion coefficient is approximated by the Stokes–Einstein relation for a single particle diffusing through a polymer melt with the same molecular weight as the grafted polymers. Therefore, this formulation connects the attempt frequency to the core particle radius, the polymer molecular weight and the core volume fraction. An increase in the polymer molecular weight leads to an increase in the viscosity of the polymer melt,

![]() $\mu _{\!p}$

, which hinders the diffusion and thus reduces the attempt frequency. Increasing the core volume fraction corresponds to smaller interparticle distances and consequently shorter time scales for the particle to diffuse relative to its neighbours. Note that the actual time scale for thermally induced rearrangements also includes the barrier as expressed by an Arrhenius law,

$\mu _{\!p}$

, which hinders the diffusion and thus reduces the attempt frequency. Increasing the core volume fraction corresponds to smaller interparticle distances and consequently shorter time scales for the particle to diffuse relative to its neighbours. Note that the actual time scale for thermally induced rearrangements also includes the barrier as expressed by an Arrhenius law,

![]() $\tau = \tau _0 \, \exp ({\mathcal{R}}/{k_{\textit{B}}T} )$

. All the calculations are performed assuming a temperature of

$\tau = \tau _0 \, \exp ({\mathcal{R}}/{k_{\textit{B}}T} )$

. All the calculations are performed assuming a temperature of

![]() $T = 100 \, ^\circ \mathrm{C}$

, which is above the melting point of the solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles of interest (Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Qi and Archer2010). Another time scale in the model is the mechanical relaxation of the stress once the barrier is removed by mechanical deformation. In this work, we assume that this relaxation happens instantly thus eliminating

$T = 100 \, ^\circ \mathrm{C}$

, which is above the melting point of the solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles of interest (Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Qi and Archer2010). Another time scale in the model is the mechanical relaxation of the stress once the barrier is removed by mechanical deformation. In this work, we assume that this relaxation happens instantly thus eliminating

![]() $\varGamma _m$

from the model.

$\varGamma _m$

from the model.

Equation (3.1) is solved numerically using finite volume method to discretize the strain space for each value of

![]() $E$

. The coupling between different values of

$E$

. The coupling between different values of

![]() $E$

is achieved through the yielding rate (3.2) which is solved separately. The discontinuity introduced by the Dirac delta function is numerically challenging to resolve, and thus to ensure stability and accuracy a total variation diminishing (TVD) scheme is used. In TVD schemes, the total variation of the solution is always non-increasing in time. The TVD schemes are usually defined for homogeneous partial differential equations. Therefore, to apply this scheme to (3.1), which is a hyperbolic equation with a source term (thermally induced rearrangements), we split the equation into a homogeneous hyperbolic equation and an ordinary differential equation for the source term. In this way, we first solve the homogeneous partial differential equation by applying the TVD scheme and using the initial condition of the problem, and then we use the solution to this equation as an initial condition to solve the ordinary differential equation for the source term. This process is repeated at each time step. To update the solution in time, the second-order explicit Runge–Kutta method is used (Toro Reference Toro2013). The last two terms in (3.1) are treated as boundary conditions. Lastly, the composite midpoint rule is used as the quadrature routine for numerical integration.

$E$

is achieved through the yielding rate (3.2) which is solved separately. The discontinuity introduced by the Dirac delta function is numerically challenging to resolve, and thus to ensure stability and accuracy a total variation diminishing (TVD) scheme is used. In TVD schemes, the total variation of the solution is always non-increasing in time. The TVD schemes are usually defined for homogeneous partial differential equations. Therefore, to apply this scheme to (3.1), which is a hyperbolic equation with a source term (thermally induced rearrangements), we split the equation into a homogeneous hyperbolic equation and an ordinary differential equation for the source term. In this way, we first solve the homogeneous partial differential equation by applying the TVD scheme and using the initial condition of the problem, and then we use the solution to this equation as an initial condition to solve the ordinary differential equation for the source term. This process is repeated at each time step. To update the solution in time, the second-order explicit Runge–Kutta method is used (Toro Reference Toro2013). The last two terms in (3.1) are treated as boundary conditions. Lastly, the composite midpoint rule is used as the quadrature routine for numerical integration.

4. Molecular-level information

We shear the system of polymer-grafted nanoparticles in the

![]() $x$

direction while the shear gradient is in the

$x$

direction while the shear gradient is in the

![]() $z$

direction. Since the system under shear is a unit cell, once it is displaced by its size, we reproduce the same configuration. The configuration with a shear strain of

$z$

direction. Since the system under shear is a unit cell, once it is displaced by its size, we reproduce the same configuration. The configuration with a shear strain of

![]() $\gamma = 1$

results in the most deviation from the initial configuration (

$\gamma = 1$

results in the most deviation from the initial configuration (

![]() $\gamma = 0$

) since the unit cell is displaced by half of its size. As a result, we can detect all the possible configurations in a shearing cycle, by shearing the unit cell only from

$\gamma = 0$

) since the unit cell is displaced by half of its size. As a result, we can detect all the possible configurations in a shearing cycle, by shearing the unit cell only from

![]() $\gamma = 0$

to

$\gamma = 0$

to

![]() $\gamma = 1$

.

$\gamma = 1$

.

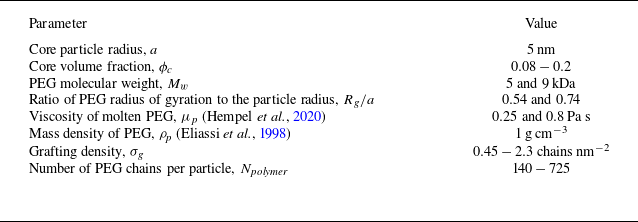

Table 1 lists the dimensional and dimensionless parameters used in this work. We assume a range of core volume fractions and two different polymer molecular weights. The void volume per core depends on the core volume fraction as

![]() ${(1-\phi _c)}/{n_c}$

where

${(1-\phi _c)}/{n_c}$

where

![]() $n_c$

is the number density of the cores. Since the grafted polymers must be able to fill the void volume, the number of grafted polymers is found by defining a volume per polymer molecule as

$n_c$

is the number density of the cores. Since the grafted polymers must be able to fill the void volume, the number of grafted polymers is found by defining a volume per polymer molecule as

![]() $({M_w}/{\rho _p N_{\!A}})$

, where

$({M_w}/{\rho _p N_{\!A}})$

, where

![]() $N_{\!A}$

is Avogadro’s number. As the core volume fraction is decreased, there is more void space in the system for polymers to fill. As a result, the number of grafted polymers (and thus the grafting density) has to increase. For a fixed core volume fraction, increasing the molecular weight of the grafted polymers decreases the grafting density. This stems from the fact that a higher molecular weight provides a larger volume per polymer molecule, and thus a smaller number of polymers is needed to fill the void space. The range of the core volume fraction and polymer molecular weights that we use in this work lead to a range of grafting densities,

$N_{\!A}$

is Avogadro’s number. As the core volume fraction is decreased, there is more void space in the system for polymers to fill. As a result, the number of grafted polymers (and thus the grafting density) has to increase. For a fixed core volume fraction, increasing the molecular weight of the grafted polymers decreases the grafting density. This stems from the fact that a higher molecular weight provides a larger volume per polymer molecule, and thus a smaller number of polymers is needed to fill the void space. The range of the core volume fraction and polymer molecular weights that we use in this work lead to a range of grafting densities,

![]() $\sigma _g = 0.45{-}2.3 \, \mathrm{chains}\,\text{nm}^{-2}$

, which is experimentally achievable (Srivastava et al. Reference Srivastava, Choudhury, Agrawal and Archer2017). The viscosity of molten PEG is also reported in table 1 for the two different molecular weights. These values will be used in the thermal SGR model to calculate the attempt frequency as described in § 3.

$\sigma _g = 0.45{-}2.3 \, \mathrm{chains}\,\text{nm}^{-2}$

, which is experimentally achievable (Srivastava et al. Reference Srivastava, Choudhury, Agrawal and Archer2017). The viscosity of molten PEG is also reported in table 1 for the two different molecular weights. These values will be used in the thermal SGR model to calculate the attempt frequency as described in § 3.

Table 1. Dimensional and dimensionless parameters used in this study. Two different polymer molecular weights are used which lead to two different radii of gyration and viscosities of melt. A range of grafting densities and number of polymer chains per particle is due to a range of core volume fractions and two different molecular weights.

4.1. Number density profiles

As shown in (2.1), a competition between the translational entropy of the polymers (captured by the beads) and the configurational entropy of the polymers (captured by the spring energy) in conjunction with the space-filling constraint (depending on the value of

![]() $\alpha$

) determines the free energy of the polymers. Figure 2 shows the number density of the grafted polymers in a system with a core volume fraction of

$\alpha$

) determines the free energy of the polymers. Figure 2 shows the number density of the grafted polymers in a system with a core volume fraction of

![]() $\phi _c=0.1$

, a grafting density of

$\phi _c=0.1$

, a grafting density of

![]() $\sigma _g = 1.8 \, \mathrm{chains}\,\text{nm}^{-2}$

and polymer molecular weight of

$\sigma _g = 1.8 \, \mathrm{chains}\,\text{nm}^{-2}$

and polymer molecular weight of

![]() $M_w = 5000 \, \mathrm{Da}$

. The number densities are shown at different points in space for the solvent-free case (

$M_w = 5000 \, \mathrm{Da}$

. The number densities are shown at different points in space for the solvent-free case (

![]() $\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

) and the case with solvent (

$\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

) and the case with solvent (

![]() $\alpha =0$

) under shear deformation. The dark blue regions display the cores where there is zero probability of finding a polymer.

$\alpha =0$

) under shear deformation. The dark blue regions display the cores where there is zero probability of finding a polymer.

Figure 2. The number density of the grafted polymers (normalized by the mean number density) at each point of the unit cell under shear deformation with different applied strains and different values of the space-filling parameter: (a)

![]() $\alpha = 0$

and

$\alpha = 0$

and

![]() $\gamma = 0$

, (b)

$\gamma = 0$

, (b)

![]() $\alpha = 0$

and

$\alpha = 0$

and

![]() $\gamma = 1$

, (c)

$\gamma = 1$

, (c)

![]() $\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

and

$\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

and

![]() $\gamma = 0$

and (d)

$\gamma = 0$

and (d)

![]() $\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

and

$\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

and

![]() $\gamma = 1$

. In all of the profiles, the core volume fraction is

$\gamma = 1$

. In all of the profiles, the core volume fraction is

![]() $\phi _c = 0.1$

, the grafting density is

$\phi _c = 0.1$

, the grafting density is

![]() $\sigma _g = 1.8 \, \mathrm{chains}\,\text{nm}^{-2}$

, and the PEG molecular weight is

$\sigma _g = 1.8 \, \mathrm{chains}\,\text{nm}^{-2}$

, and the PEG molecular weight is

![]() $M_w = 5000 \, \mathrm{Da}$

.

$M_w = 5000 \, \mathrm{Da}$

.

For

![]() $\alpha =0$

at no shear deformation (figure 2

a), the polymers are most likely found around the grafting points as they form a cloud around each core. The number density in these relatively thin clouds is larger than the mean number density. The green regions between the clouds represent a mild polymer–polymer interpenetration where the polymers from neighbouring cores meet. In regions far away from any grafting points, the number density decreases, and only a few polymers can be found. One can assume that these regions are filled with solvent molecules although their contribution to the free energy of the system is not explicitly modelled. When

$\alpha =0$

at no shear deformation (figure 2

a), the polymers are most likely found around the grafting points as they form a cloud around each core. The number density in these relatively thin clouds is larger than the mean number density. The green regions between the clouds represent a mild polymer–polymer interpenetration where the polymers from neighbouring cores meet. In regions far away from any grafting points, the number density decreases, and only a few polymers can be found. One can assume that these regions are filled with solvent molecules although their contribution to the free energy of the system is not explicitly modelled. When

![]() $\alpha =0$

, there is no constraint requiring the polymers to stretch and fill the interstitial space, and they are free to occupy interstitial space in a manner that maximizes the sum of their translational and configurational entropies. To fill the entire void space, the polymers have to highly stretch which causes a large spring energy contribution to the free energy. As a result, the polymers remain near their grafting points and avoid stretching in order to minimize their spring energy. For

$\alpha =0$

, there is no constraint requiring the polymers to stretch and fill the interstitial space, and they are free to occupy interstitial space in a manner that maximizes the sum of their translational and configurational entropies. To fill the entire void space, the polymers have to highly stretch which causes a large spring energy contribution to the free energy. As a result, the polymers remain near their grafting points and avoid stretching in order to minimize their spring energy. For

![]() $\alpha =0$

under maximum deformation (figure 2

b), polymers would need to stretch and increase their spring energy to fill the additional space along the extensional axis. Thus, the polymers avoid filling the added volume along the extensional axis to minimize their free energy resulting in an almost zero number density along this axis. As a result, the polymers from neighbouring particles accumulate along the compressional axis leading to a very non-uniform number density profile in the shear plane. Since the plane

$\alpha =0$

under maximum deformation (figure 2

b), polymers would need to stretch and increase their spring energy to fill the additional space along the extensional axis. Thus, the polymers avoid filling the added volume along the extensional axis to minimize their free energy resulting in an almost zero number density along this axis. As a result, the polymers from neighbouring particles accumulate along the compressional axis leading to a very non-uniform number density profile in the shear plane. Since the plane

![]() $z=0$

undergoes no shear deformation, the polymers in this plane form the thin clouds around the cores which are the hallmark of the case with

$z=0$

undergoes no shear deformation, the polymers in this plane form the thin clouds around the cores which are the hallmark of the case with

![]() $\alpha =0$

and zero applied strain (figure 2

a).

$\alpha =0$

and zero applied strain (figure 2

a).

When

![]() $\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

, the space-filling constraint is imposed and the polymers stretch and uniformly fill the entire interstitial space under both minimum (figure 2

c) and maximum (figure 2

d) deformation. In this case, the polymers are not compressed as, at each point, they have a number density equal to the mean number density corresponding to an incompressible single-component fluid. This is corroborated by scattering experiment, theoretical and molecular simulation results for the structure factor showing that density fluctuations are highly suppressed in solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles (Yu & Koch Reference Yu and Koch2010; Chremos et al. Reference Chremos, Panagiotopoulos, Yu and Koch2011; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Srivastava, Archer and Koch2014). This situation corresponds to many-body interactions between the cores as their grafted polymers cooperate to fill the void space. Although filling the entire void space is accompanied by a large spring energy, the penalty for not filling the entire space is much larger than the spring energy when

$\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

, the space-filling constraint is imposed and the polymers stretch and uniformly fill the entire interstitial space under both minimum (figure 2

c) and maximum (figure 2

d) deformation. In this case, the polymers are not compressed as, at each point, they have a number density equal to the mean number density corresponding to an incompressible single-component fluid. This is corroborated by scattering experiment, theoretical and molecular simulation results for the structure factor showing that density fluctuations are highly suppressed in solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles (Yu & Koch Reference Yu and Koch2010; Chremos et al. Reference Chremos, Panagiotopoulos, Yu and Koch2011; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Srivastava, Archer and Koch2014). This situation corresponds to many-body interactions between the cores as their grafted polymers cooperate to fill the void space. Although filling the entire void space is accompanied by a large spring energy, the penalty for not filling the entire space is much larger than the spring energy when

![]() $\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

. Therefore, to minimize their free energy, the polymers have to satisfy the space-filling constraint and consequently

$\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

. Therefore, to minimize their free energy, the polymers have to satisfy the space-filling constraint and consequently

![]() $n(\boldsymbol{r}) \approx n_0$

at any point in the void space (the number density profiles of figure 2

c and 2

d). The origin of the slow dynamics of solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles can be found in the space-filling constraint and will be discussed in depth in § 4.2 and § 4.3. This observation is supported by experiments (Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Qi and Archer2010, Reference Agarwal, Srivastava and Archer2011) and molecular dynamics simulations (Midya et al. Reference Midya, Rubinstein, Kumar and Nikoubashman2020) on solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles indicating a high degree of polymer interpenetration in the system and formation of cages around the cores which slow down the relaxation. To understand how the system evolves under shear from figure 2(a) and 2(c), to figure 2(b) and 2(d), respectively, we quantitatively demonstrate the different contributions to the free energy along with the effects of the space-filling penalty in a cycle of shear.

$n(\boldsymbol{r}) \approx n_0$

at any point in the void space (the number density profiles of figure 2

c and 2

d). The origin of the slow dynamics of solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles can be found in the space-filling constraint and will be discussed in depth in § 4.2 and § 4.3. This observation is supported by experiments (Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Qi and Archer2010, Reference Agarwal, Srivastava and Archer2011) and molecular dynamics simulations (Midya et al. Reference Midya, Rubinstein, Kumar and Nikoubashman2020) on solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles indicating a high degree of polymer interpenetration in the system and formation of cages around the cores which slow down the relaxation. To understand how the system evolves under shear from figure 2(a) and 2(c), to figure 2(b) and 2(d), respectively, we quantitatively demonstrate the different contributions to the free energy along with the effects of the space-filling penalty in a cycle of shear.

4.2. Free energy and entropy of the grafted polymers

Figure 3 illustrates how the free energy of the polymers grafted on a single core changes with respect to the shear deformation and the space-filling parameter in a system with a core volume fraction of

![]() $\phi _c = 0.1$

, a grafting density of

$\phi _c = 0.1$

, a grafting density of

![]() $\sigma _g = 1.8 \, \mathrm{chains\,nm^{-2}}$

and a PEG molecular weight of

$\sigma _g = 1.8 \, \mathrm{chains\,nm^{-2}}$

and a PEG molecular weight of

![]() $M_w = 5000 \, \mathrm{Da}$

. Since the entropic free energy is

$M_w = 5000 \, \mathrm{Da}$

. Since the entropic free energy is

![]() $-T\Delta S$

, where

$-T\Delta S$

, where

![]() $S$

is the entropy, figure 3 also shows how the translational entropy of the beads changes with respect to the space-filling parameter and shear deformation. Positive changes in the entropic free energy correspond to negative changes in the translational entropy of the beads and vice versa. Increasing

$S$

is the entropy, figure 3 also shows how the translational entropy of the beads changes with respect to the space-filling parameter and shear deformation. Positive changes in the entropic free energy correspond to negative changes in the translational entropy of the beads and vice versa. Increasing

![]() $\alpha$

, regardless of the value of the shear strain, monotonically increases the total free energy of the polymers (figure 3

a) and the translational entropy of the beads until they reach a plateau. For

$\alpha$

, regardless of the value of the shear strain, monotonically increases the total free energy of the polymers (figure 3

a) and the translational entropy of the beads until they reach a plateau. For

![]() $\alpha \gt 0.4$

, the state of the system appears to be insensitive to the value of

$\alpha \gt 0.4$

, the state of the system appears to be insensitive to the value of

![]() $\alpha$

, implying that the space-filling constraint is satisfied. This can be regarded as the solvent-free case, i.e.

$\alpha$

, implying that the space-filling constraint is satisfied. This can be regarded as the solvent-free case, i.e.

![]() $\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

.

$\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

.

Figure 3. (a) The changes in the free energy of the polymers as a function of the space-filling parameter relative to the values at

![]() $\alpha =0$

(open symbols,

$\alpha =0$

(open symbols,

![]() $\gamma = 0$

; filled symbols,

$\gamma = 0$

; filled symbols,

![]() $\gamma = 1$

). (b) The evolution of the total free energy and different contributions to the free energy with shear strain relative to the values at

$\gamma = 1$

). (b) The evolution of the total free energy and different contributions to the free energy with shear strain relative to the values at

![]() $\gamma =0$

(open symbols,

$\gamma =0$

(open symbols,

![]() $\alpha = 0$

; filled symbols,

$\alpha = 0$

; filled symbols,

![]() $\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

). The core volume fraction is

$\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

). The core volume fraction is

![]() $\phi _c = 0.1$

, the grafting density is

$\phi _c = 0.1$

, the grafting density is

![]() $\sigma _g = 1.8 \, \mathrm{chains}\,\text{nm}^{-2}$

, and the PEG molecular weight is

$\sigma _g = 1.8 \, \mathrm{chains}\,\text{nm}^{-2}$

, and the PEG molecular weight is

![]() $M_w = 5000 \, \mathrm{Da}$

.

$M_w = 5000 \, \mathrm{Da}$

.

The polymers always choose the configurations that minimize their free energy. In the absence of the space-filling constraint, all the configurations are allowed corresponding to a large configurational entropy for the chains. The configurations that lead to a small spring energy are preferred due to the free energy minimization. Thus, the polymers choose the configurations that avoid stretching as much as possible, shown in figure 2(a) and 2(b). However, these configurations lead to a small translational entropy since the probabilities of finding the polymers in the void space are highly inhomogeneous. On the other hand, when the space-filling constraint is imposed, the polymers are forced to choose only between the configurations that result in a relatively large stretch. This reduces the number of allowed configurations for the chains and greatly suppresses their configurational entropy. In this case, the chains are ‘frustrated’ because their conformational space is extremely limited. This entropic frustration of the chain configurations, which is a unique characteristic of solvent-free polymer-grafted nanoparticles (Agarwal, Kim & Archer Reference Agarwal, Kim and Archer2012; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Srivastava, Archer and Koch2014), manifests itself here through the drastic increase in the spring energy as the space-filling constraint is enforced (figure 3

a). However, satisfying the space-filling constraint brings about an advantage for the translational entropy. In this situation, the number density (and thus the probability distribution) of the polymers is uniform in the void space (figure 2

c and 2d

) correlating with a large translational entropy for the polymers. Therefore, the role of the space-filling parameter in the configurational entropy of the polymers (spring energy) and in the translational entropy of the polymers can be interpreted as unfavourable and favourable, respectively. Since the effects on the configurational entropy are more pronounced, the total free energy increases with

![]() $\alpha$

.

$\alpha$

.

The free energy penalty is zero when

![]() $\alpha = 0$

and also when the polymers uniformly fill the interstitial space since

$\alpha = 0$

and also when the polymers uniformly fill the interstitial space since

![]() $n(\boldsymbol{r}) \approx n_0$

at any point (see (2.1)). However, one should note that changing

$n(\boldsymbol{r}) \approx n_0$

at any point (see (2.1)). However, one should note that changing

![]() $\alpha$

alters the probabilities and thus the free energy and entropy, as described earlier and evidenced by figure 3 and number density profiles in figure 2. An interesting observation is the non-zero values of the free energy penalty for small, non-zero values of

$\alpha$

alters the probabilities and thus the free energy and entropy, as described earlier and evidenced by figure 3 and number density profiles in figure 2. An interesting observation is the non-zero values of the free energy penalty for small, non-zero values of

![]() $\alpha$

. Since

$\alpha$

. Since

![]() $\alpha$

is small, the space-filling constraint is mildly enforced and thus the number density at each point still deviates from the mean value. This can be considered as a compressible system in which the thermal energy of the polymers can cause variations in their number density. However, large variations are not allowed as they lead to a large free energy penalty. In this case, the polymers have more freedom in choosing different configurations compared with when

$\alpha$

is small, the space-filling constraint is mildly enforced and thus the number density at each point still deviates from the mean value. This can be considered as a compressible system in which the thermal energy of the polymers can cause variations in their number density. However, large variations are not allowed as they lead to a large free energy penalty. In this case, the polymers have more freedom in choosing different configurations compared with when

![]() $\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

. Therefore, decreasing

$\alpha \rightarrow \infty$

. Therefore, decreasing

![]() $\alpha$

(increasing the compressibility of the system) releases the entropic frustration of the chain configurations.

$\alpha$

(increasing the compressibility of the system) releases the entropic frustration of the chain configurations.

Figure 3(b) shows that by starting from the initial configuration, the free energy and the translational entropy change with shear strain until they reach a maximum difference (at

![]() $\gamma = 1$

) where the cores experience the most deviation from their initial configuration. The core configuration has mirror symmetry about the

$\gamma = 1$

) where the cores experience the most deviation from their initial configuration. The core configuration has mirror symmetry about the

![]() $zy$

plane such that shearing beyond

$zy$

plane such that shearing beyond

![]() $\gamma =1$

yields configurations in which strain of

$\gamma =1$

yields configurations in which strain of

![]() $1+\delta \gamma$

is the mirror image (with equal free energy) of that with strain of

$1+\delta \gamma$

is the mirror image (with equal free energy) of that with strain of

![]() $1-\delta \gamma$

.

$1-\delta \gamma$

.

Figure 3(b) indicates that, at

![]() $\alpha =0$

, the spring energy decreases under shear deformation corresponding to the polymers being less stretched as they leave the extensional axis. Since shearing in this case leads to even less homogeneous probabilities (transition from figure 2

a to 2b

), the translational entropy of the polymers decreases under deformation. Thus, at

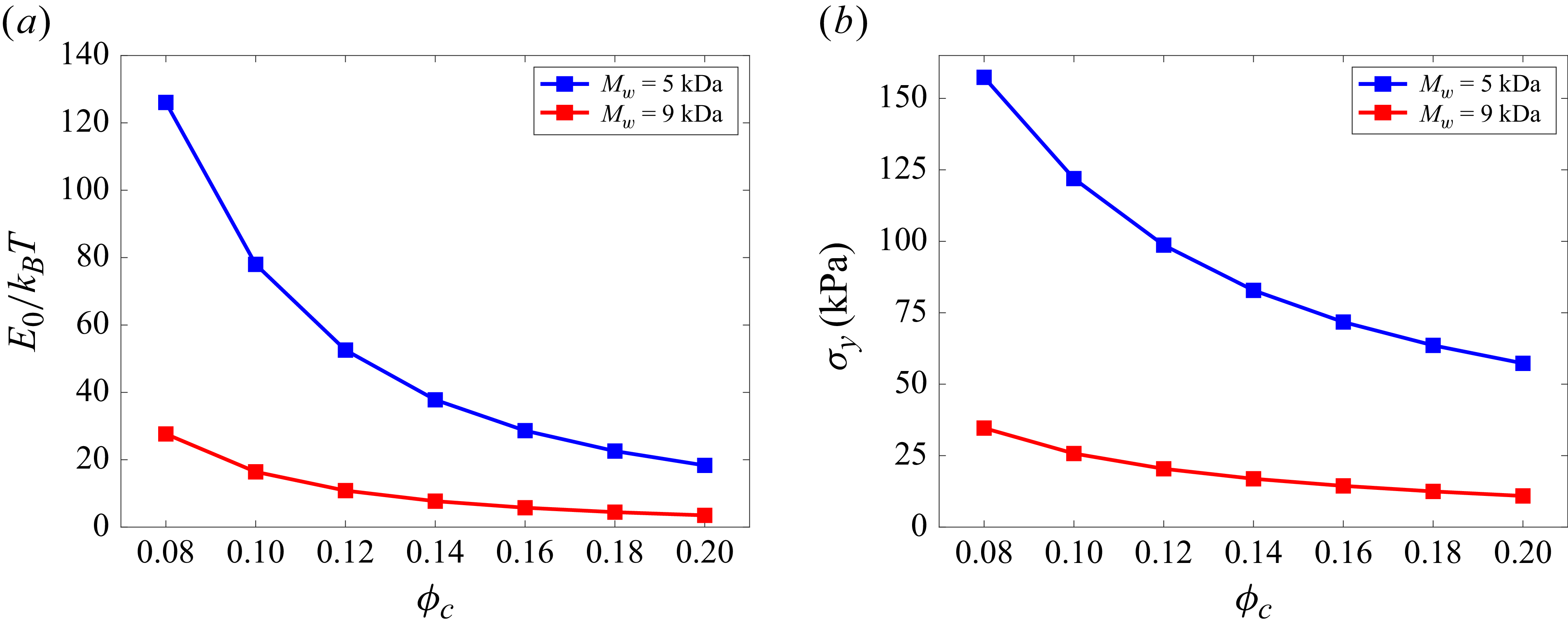

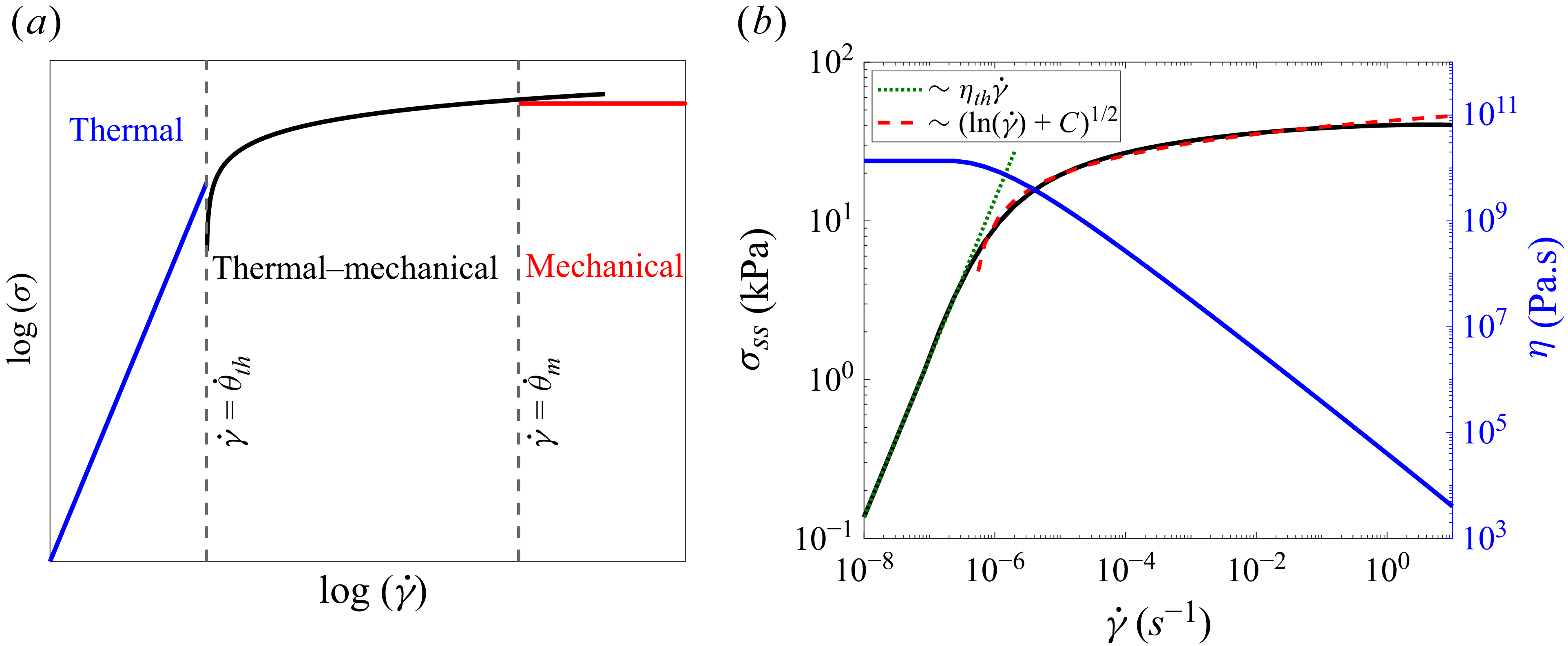

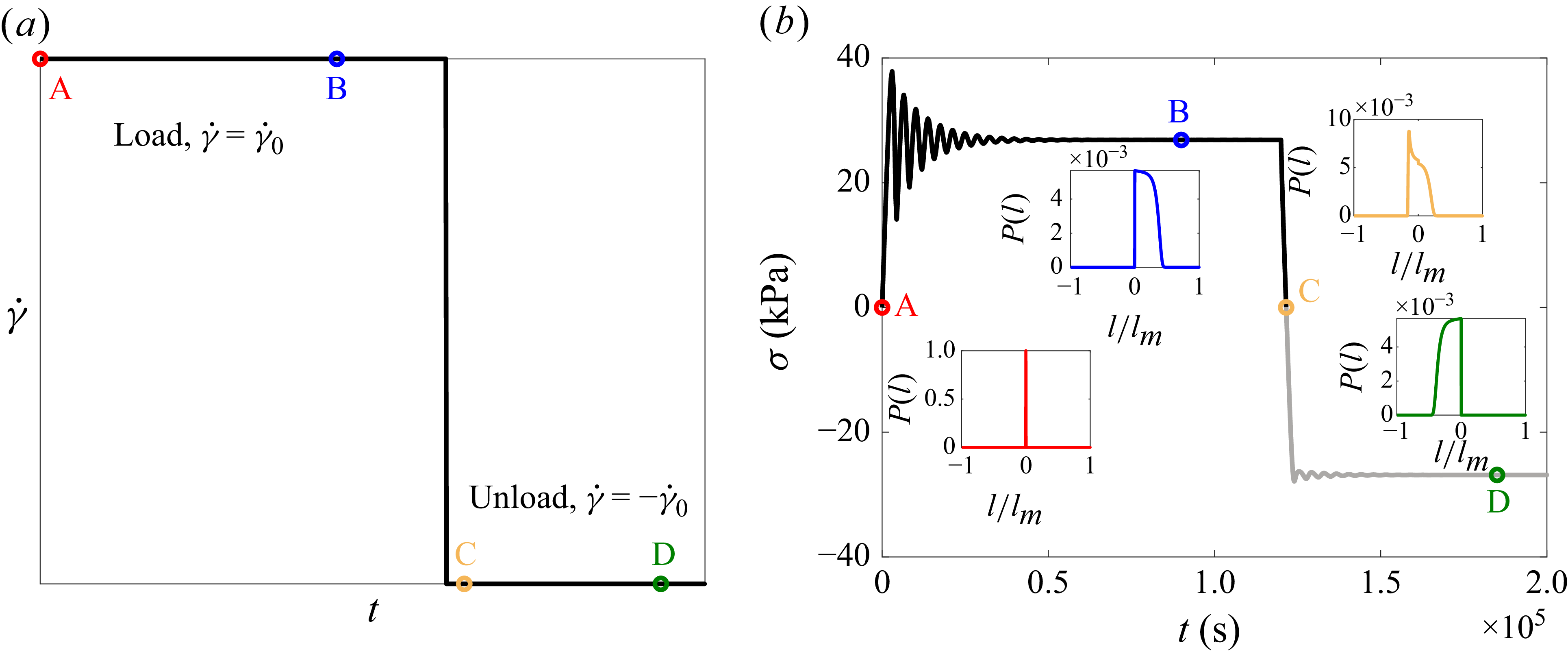

$\alpha =0$