1. Introduction

Practical combustion processes take place in a confined burner. As a consequence, internal combustion engines, gas turbines, etc. need to consider flame–wall interactions (FWIs). The presence of the wall not only significantly affects the flame dynamics (Ng et al. Reference Ng, Cheng, Robben and Talbot1982; Poinsot, Haworth & Bruneaux Reference Poinsot, Haworth and Bruneaux1993; Zhao, Wang & Chakraborty Reference Zhao, Wang and Chakraborty2018), but also influences pollutant production (Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Brouzet, Talei, Gordon, Cazeres and Cuenot2021; Chi Reference Chi2024a ). Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the near-wall flame dynamics is in great demand.

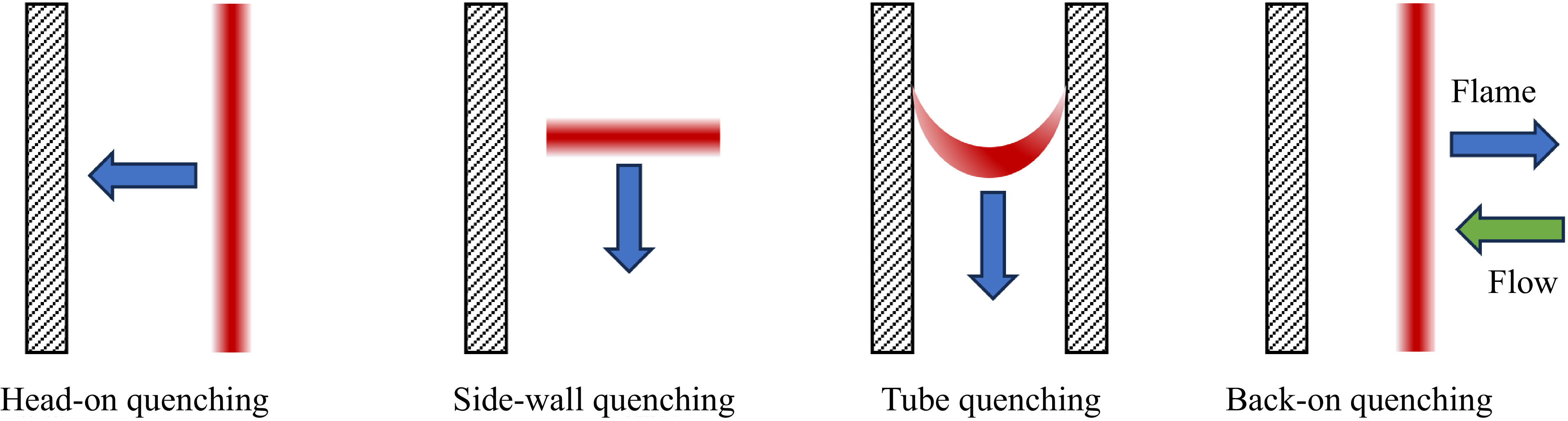

Due to the limited temporal and spatial resolutions in experiments and intricate near-wall turbulent flame dynamics, direct numerical simulation (DNS) appears as the most suitable approach to study the transient behaviour of the near-wall flame dynamics. Previous numerical studies on FWIs mostly focus on four different configurations as depicted in figure 1: (i) head-on quenching (Hocks, Peters & Adomeit Reference Hocks, Peters and Adomeit1981; Westbrook, Adamczyk & Lavoie Reference Westbrook, Adamczyk and Lavoie1981; Poinsot et al. Reference Poinsot, Haworth and Bruneaux1993; Wichman & Bruneaux Reference Wichman and Bruneaux1995; Bruneaux et al. Reference Bruneaux, Akselvoll, Poinsot and Ferziger1996; Popp, Smooke & Baum Reference Popp, Smooke and Baum1996; Bruneaux, Poinsot & Ferziger Reference Bruneaux, Poinsot and Ferziger1997; Popp & Baum Reference Popp and Baum1997; Ezekoye Reference Ezekoye1998; Dabireau et al. Reference Dabireau, Cuenot, Vermorel and Poinsot2003; Mari et al. Reference Mari, Cuenot, Rocchi, Selle and Duchaine2016; Sellmann et al. Reference Sellmann, Lai, Kempf and Chakraborty2017; Ohta, Onishi & Sakai Reference Ohta, Onishi and Sakai2022; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Cai, Chi, Mashruk, Valera-Medina and Maas2023; De Nardi et al. Reference De Nardi, Douasbin, Vermorel and Poinsot2024; Tamadonfar et al. Reference Tamadonfar, Karimkashi, Zirwes, Vuorinen and Kaario2024), (ii) side-wall quenching (Kármán & Millán Reference Kármán and Millán1953; Alshaalan & Rutland Reference Alshaalan and Rutland1998; Andrae et al. Reference Andrae, Björnbom, Edsberg and Eriksson2002; Gruber et al. Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010; Palulli, Talei & Gordon Reference Palulli, Talei and Gordon2019; Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Brouzet, Talei, Gordon, Cazeres and Cuenot2021; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Zirwes, Häber, Bockhorn, Trimis and Suntz2021; Zirwes et al. Reference Zirwes2021; Kaddar et al. Reference Kaddar, Steinhausen, Zirwes, Bockhorn, Hasse and Ferraro2023; Luo et al. Reference Luo, Steinhausen, Kaddar, Hasse and Ferraro2023; Steinhausen et al. Reference Steinhausen, Zirwes, Ferraro, Scholtissek, Bockhorn and Hasse2023; Tamadonfar et al. Reference Tamadonfar, Salomaa, Rintanen, Karimkashi, Zirwes, Vuorinen and Kaario2025), (iii) tube quenching (Palmer & Tonkin Reference Palmer and Tonkin1963; Bai et al. Reference Bai, Chen, Zhang and Chen2013; Bioche, Vervisch & Ribert Reference Bioche, Vervisch and Ribert2018), and (iv) back-on quenching (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Wang and Chakraborty2018; Konstantinou, Ahmed & Chakraborty Reference Konstantinou, Ahmed and Chakraborty2021; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang, Luo, Hawkes, Chen and Fan2021; Zhao, Wang & Chakraborty Reference Zhao, Wang and Chakraborty2021; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Hernández, Francisco, Guo, Im and Wang2022, Reference Zhao, Zhang, Hernández Pérez, Im and Wang2023; Tomidokoro & Im Reference Tomidokoro and Im2024). In the present study we investigate the head-on flame quenching in a fully developed channel flow. This configuration was initially studied in Bruneaux et al. (Reference Bruneaux, Akselvoll, Poinsot and Ferziger1996, Reference Bruneaux, Poinsot and Ferziger1997) with one-step chemistry. Later, V-shaped premixed flames were studied in a channel flow in Alshaalan & Rutland (Reference Alshaalan and Rutland1998, Reference Alshaalan and Rutland2002), Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010), Wang & Tanahashi (Reference Wang and Tanahashi2024). Recently, both the head-on and V-shaped flames were studied and compared in a channel flow in Ahmed et al. (Reference Ahmed, Chakraborty and Klein2021b

,

Reference Ahmed, Chakraborty and Kleinc

,

Reference Ahmed, Chakraborty and Kleind

, Reference Ahmed, Chakraborty and Klein2023), Ghai et al. (Reference Ghai, Ahmed, Klein and Chakraborty2023). This configuration is interesting because the wall turbulence is statistically steady and can be uniquely described based on the friction Reynolds number Re

![]() $_\tau$

. More specifically, a turbulent boundary layer is typically present in practical systems, so that the conclusions are useful and instructive.

$_\tau$

. More specifically, a turbulent boundary layer is typically present in practical systems, so that the conclusions are useful and instructive.

Figure 1. Sketch of the four different FWI configurations.

Previous studies have revealed different physics for near-wall flames compared with free flames, due to wall confinement and wall heat loss. One of the most distinct observations is that the flame thickness would increase significantly near the wall (Gruber et al. Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010; Gruber et al. Reference Gruber, Richardson, Aditya and Chen2018; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Wang and Chakraborty2018). This would result in a change of the turbulent combustion regime for near-wall flames and directly affect the flame surface density (Bruneaux et al. Reference Bruneaux, Poinsot and Ferziger1997; Sellmann et al. Reference Sellmann, Lai, Kempf and Chakraborty2017). Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010) proposed two reasons to explain the increased flame thickness in their study: (i) the increased unsteadiness and wrinkling of the flame brush near the wall results in an increase of the averaged flame thickness, and (ii) the turbulent length and time scales decrease near the wall, while the chemical time scale increases due to heat loss. This results in a decrease in the local Damköhler number and entrainment of small eddies into the flame zone. These two reasons can be summarised as (i) effects of wall heat loss and (ii) near-wall change of turbulent scales. Though being physically perfectly reasonable, the two phenomena proposed in Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010) have to our knowledge never been fully validated. Additionally, variations of turbulent length and time scales near the wall were found to be highly dependent on the friction Reynolds number (Ahmed et al. Reference Ahmed, Apsley, Stallard, Stansby and Afgan2021a ), and it is not clear which one is the dominant factor for flame thickening during FWIs.

Apart from flame thickness, another distinct observation is that the flame displacement speed is still large even when the reaction rate becomes negligibly small and the global flame burning rate approaches zero as the flame is very close to the wall (Gruber et al. Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Wang and Chakraborty2021, Reference Zhao, Hernández, Francisco, Guo, Im and Wang2022). Flame displacement speed is an important quantity to characterise the turbulent flame propagation speed and is essential for modelling turbulent premixed combustion (Dave & Chaudhuri Reference Dave and Chaudhuri2020). Very recently, Tomidokoro & Im (Reference Tomidokoro and Im2024) explained that the non-zero flame displacement speed near the wall is because of the diffusive term in the non-reactive region of the flame zone. This explanation is built on the back-on quenching configuration. However, this may not explain the similar behaviour observed in the head-on quenching configuration. Hence, further investigations of the flame displacement speed statistics in such configuration are needed.

Due to the change of flame thickness and flame speed near walls, the turbulent combustion regime would also change. Since the turbulence scales are also varying with wall distance, an accurate determination of the combustion regime during FWIs is difficult, but especially important for reduced models (Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes and large-eddy simulations), which are often designed for specific combustion regimes. Only few studies have been done to investigate the combustion regime dynamics during FWIs. Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Richardson, Aditya and Chen2018) investigated the combustion regime for premixed and stratified flames propagating in a turbulent channel flow and observed a transition from ‘thin flamelets’ in the bulk flow to ‘thickened flamelets’ near the wall. This is qualitatively consistent with the findings in Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010) (for side-wall quenching) and Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Wang and Chakraborty2018) (for back-on quenching). However, these studies did not investigate quantitatively at which wall distance the combustion regime is changing.

The main objectives of the present study are therefore to (i) quantify separately the effects of wall heat loss and wall turbulence on flame thickness during FWIs, (ii) analyse the dynamics of flame displacement speed and reveal the underlying reason for the high displacement speed very close to the wall, (iii) investigate the evolution of the turbulent combustion regime during FWIs, and (iv) clarify the cumulative effects of wall turbulence and wall heat loss on the turbulent flame dynamics during FWIs. To achieve these objectives, DNS of turbulent premixed H

![]() $_2/$

air and NH

$_2/$

air and NH

![]() $_3/$

H

$_3/$

H

![]() $_2/$

air flames in a fully developed channel flow at Re

$_2/$

air flames in a fully developed channel flow at Re

![]() $_\tau$

$_\tau$

![]() $\approx$

300 with both isothermal and adiabatic walls are carried out. These specific fuels have been selected since H

$\approx$

300 with both isothermal and adiabatic walls are carried out. These specific fuels have been selected since H

![]() $_2$

and NH

$_2$

and NH

![]() $_3/$

H

$_3/$

H

![]() $_2$

are attracting increasing attention in the combustion community due to their high energy efficiency while being carbon free (Valera-Medina et al. Reference Valera-Medina, Xiao, Owen-Jones, David and Bowen2018; Kobayashi et al. Reference Kobayashi, Hayakawa, Somarathne and Okafor2019; Pitsch Reference Pitsch2024). Thus, the present study is especially relevant for the upcoming energy transition and provides new physical insights on the FWI process for such flames. In what follows, § 2 introduces the numerical configurations, § 3 presents the results for a laminar FWI process, before the turbulent results are discussed and analysed in detail in § 4. The final conclusions are summarised in § 5.

$_2$

are attracting increasing attention in the combustion community due to their high energy efficiency while being carbon free (Valera-Medina et al. Reference Valera-Medina, Xiao, Owen-Jones, David and Bowen2018; Kobayashi et al. Reference Kobayashi, Hayakawa, Somarathne and Okafor2019; Pitsch Reference Pitsch2024). Thus, the present study is especially relevant for the upcoming energy transition and provides new physical insights on the FWI process for such flames. In what follows, § 2 introduces the numerical configurations, § 3 presents the results for a laminar FWI process, before the turbulent results are discussed and analysed in detail in § 4. The final conclusions are summarised in § 5.

2. Numerical configurations

The present study involves DNS of turbulent premixed H

![]() $_2/$

air and NH

$_2/$

air and NH

![]() $_3/$

H

$_3/$

H

![]() $_2/$

air flames in a fully developed channel flow. The case set-up is similar to our recent studies in (Chi et al. Reference Chi, Yu, Cuenot, Maas and Thévenin2024, Reference Chi, Theisel and Thévenin2023b

; Chi Reference Chi2024a

). The detailed mechanism from Jiang et al. (Reference Jiang, Gruber, Seshadri and Williams2020) has been used to simulate the NH

$_2/$

air flames in a fully developed channel flow. The case set-up is similar to our recent studies in (Chi et al. Reference Chi, Yu, Cuenot, Maas and Thévenin2024, Reference Chi, Theisel and Thévenin2023b

; Chi Reference Chi2024a

). The detailed mechanism from Jiang et al. (Reference Jiang, Gruber, Seshadri and Williams2020) has been used to simulate the NH

![]() $_3/$

H

$_3/$

H

![]() $_2/$

air combustion kinetics, after successful validation in previous investigations (Chi et al. Reference Chi, Han and Thévenin2023a

; Chi & Thévenin Reference Chi and Thévenin2023). Regarding H

$_2/$

air combustion kinetics, after successful validation in previous investigations (Chi et al. Reference Chi, Han and Thévenin2023a

; Chi & Thévenin Reference Chi and Thévenin2023). Regarding H

![]() $_2/$

air combustion kinetics, the mechanism from Li et al. (Reference Li, Zhao, Kazakov and Dryer2004) has been used, as for the previous FWI study in Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010). A mixture-averaged diffusion model has been applied to describe molecular species transport. Soret effect (thermodiffusion) is not considered since this effect has been found negligible during the FWI process (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Cai, Chi, Mashruk, Valera-Medina and Maas2023). All the DNS are carried out using the in-house combustion solver DINO (Abdelsamie et al. Reference Abdelsamie, Fru, Oster, Dietzsch, Janiga and Thévenin2016).

$_2/$

air combustion kinetics, the mechanism from Li et al. (Reference Li, Zhao, Kazakov and Dryer2004) has been used, as for the previous FWI study in Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010). A mixture-averaged diffusion model has been applied to describe molecular species transport. Soret effect (thermodiffusion) is not considered since this effect has been found negligible during the FWI process (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Cai, Chi, Mashruk, Valera-Medina and Maas2023). All the DNS are carried out using the in-house combustion solver DINO (Abdelsamie et al. Reference Abdelsamie, Fru, Oster, Dietzsch, Janiga and Thévenin2016).

Cold channel flows are firstly simulated until the wall turbulence is fully developed. The channel has streamwise (

![]() $x$

), wall-normal (

$x$

), wall-normal (

![]() $y$

) and spanwise (

$y$

) and spanwise (

![]() $z$

) lengths of

$z$

) lengths of

![]() $5h$

,

$5h$

,

![]() $2h$

and

$2h$

and

![]() $2h$

, respectively, where

$2h$

, respectively, where

![]() $h =5$

mm is the half-width of the channel. This domain size is large enough in both the streamwise and spanwise directions to capture all turbulence scales, as clarified in Appendix A. A detailed validation of the wall turbulence statistics of the cold flows can be found in Chi et al. (Reference Chi, Yu, Cuenot, Maas and Thévenin2024). Further validations of the cold flow concerning turbulent dissipation rate and turbulent kinetic energy distribution can be found in Appendix B. Afterwards, two identical flame fronts (mapped from one-dimensional (1-D) unstretched freely propagating flame solutions) are initiated at

$h =5$

mm is the half-width of the channel. This domain size is large enough in both the streamwise and spanwise directions to capture all turbulence scales, as clarified in Appendix A. A detailed validation of the wall turbulence statistics of the cold flows can be found in Chi et al. (Reference Chi, Yu, Cuenot, Maas and Thévenin2024). Further validations of the cold flow concerning turbulent dissipation rate and turbulent kinetic energy distribution can be found in Appendix B. Afterwards, two identical flame fronts (mapped from one-dimensional (1-D) unstretched freely propagating flame solutions) are initiated at

![]() $y = 0.5 h$

and

$y = 0.5 h$

and

![]() $y = 1.5 h$

, with burned gases in the channel centre and flames propagating towards the top and bottom cold walls, as shown in figure 2. The simulations are continued until the flames quench on the isothermal wall or consume all fresh gases near the adiabatic wall. In total, these DNS required nearly 15 million CPU hours on the supercomputer JUWELS in the Jülich Supercomputing Center Germany and produced 12 TB of data, which are freely shared on Zenodo (Chi Reference Chi2024b

). The numerical details are listed in table 1.

$y = 1.5 h$

, with burned gases in the channel centre and flames propagating towards the top and bottom cold walls, as shown in figure 2. The simulations are continued until the flames quench on the isothermal wall or consume all fresh gases near the adiabatic wall. In total, these DNS required nearly 15 million CPU hours on the supercomputer JUWELS in the Jülich Supercomputing Center Germany and produced 12 TB of data, which are freely shared on Zenodo (Chi Reference Chi2024b

). The numerical details are listed in table 1.

Figure 2. Direct numerical simulation configuration showing the propagation of the flame surfaces towards the top and bottom channel walls at different times (from top to bottom) for a H

![]() $_2/$

air flame (left, case HI) and a NH

$_2/$

air flame (left, case HI) and a NH

![]() $_3/$

H

$_3/$

H

![]() $_2/$

air flame (right, case AI). The flame surface is indicated by

$_2/$

air flame (right, case AI). The flame surface is indicated by

![]() $C = C^\ast =0.55$

in case HI and

$C = C^\ast =0.55$

in case HI and

![]() $C = C^\ast =0.78$

in case AI, with the progress variable

$C = C^\ast =0.78$

in case AI, with the progress variable

![]() $C$

defined by Y

$C$

defined by Y

![]() $_{{{\rm H}_2{\rm O}}}$

and

$_{{{\rm H}_2{\rm O}}}$

and

![]() $C^\ast$

corresponding to the peak of heat release rate (HRR) in the corresponding laminar flames. The flame surfaces have been coloured by the surface density function (SDF)

$C^\ast$

corresponding to the peak of heat release rate (HRR) in the corresponding laminar flames. The flame surfaces have been coloured by the surface density function (SDF)

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

.

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

.

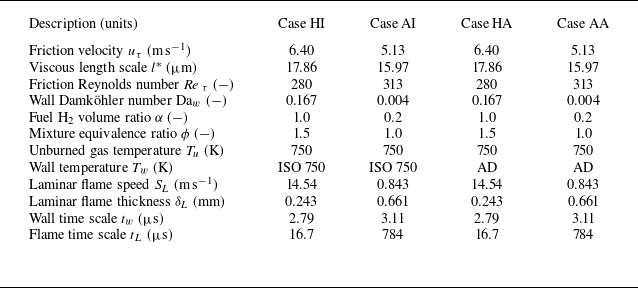

Table 1. Numerical details of the DNS cases. Here ISO denotes isothermal and AD denotes adiabatic.

The table contains the viscous length scale

![]() $l^{\ast } = \nu /u_{\tau }$

, with

$l^{\ast } = \nu /u_{\tau }$

, with

![]() $\nu$

the kinematic viscosity, as well as the friction Reynolds number Re

$\nu$

the kinematic viscosity, as well as the friction Reynolds number Re

![]() $_{\tau }$

=

$_{\tau }$

=

![]() $hu_\tau /\nu$

and wall Damköhler number Da

$hu_\tau /\nu$

and wall Damköhler number Da

![]() $_w$

=

$_w$

=

![]() $t_w/t_L$

(Gruber et al. Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010). The quantity

$t_w/t_L$

(Gruber et al. Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010). The quantity

![]() $t_w = \nu /u_{\tau }^2$

is the wall time scale and

$t_w = \nu /u_{\tau }^2$

is the wall time scale and

![]() $t_L = \delta _L/S_L$

is the flame time scale, with

$t_L = \delta _L/S_L$

is the flame time scale, with

![]() $\delta _L = (T_{ad}-T_u)/\max (|\boldsymbol{\nabla }T|)$

the laminar flame thickness of the unstretched freely propagating laminar flame,

$\delta _L = (T_{ad}-T_u)/\max (|\boldsymbol{\nabla }T|)$

the laminar flame thickness of the unstretched freely propagating laminar flame,

![]() $T_{ad}$

and

$T_{ad}$

and

![]() $T_u$

the adiabatic flame temperature and unburned gas temperature, respectively. Here

$T_u$

the adiabatic flame temperature and unburned gas temperature, respectively. Here

![]() $S_L$

is the laminar flame speed. Selecting an equivalence ratio

$S_L$

is the laminar flame speed. Selecting an equivalence ratio

![]() $\phi = 1.5$

for the H

$\phi = 1.5$

for the H

![]() $_2/$

air flame reduces the potential effect of thermodiffusive instability and is consistent with the previous study in Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010). On the other hand, using

$_2/$

air flame reduces the potential effect of thermodiffusive instability and is consistent with the previous study in Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010). On the other hand, using

![]() $\phi = 1.0$

for the NH

$\phi = 1.0$

for the NH

![]() $_3/$

H

$_3/$

H

![]() $_2/$

air flame leads to a higher flame velocity (keeping in mind the typically very low flame speeds obtained when burning ammonia), resulting in a shorter channel transit time and lower computational cost. Overall, there are four DNS cases: case HI and case AI are H

$_2/$

air flame leads to a higher flame velocity (keeping in mind the typically very low flame speeds obtained when burning ammonia), resulting in a shorter channel transit time and lower computational cost. Overall, there are four DNS cases: case HI and case AI are H

![]() $_2/$

air and NH

$_2/$

air and NH

![]() $_3/$

H

$_3/$

H

![]() $_2/$

air flames with isothermal walls, while case HA and case AA are the same flames, but with adiabatic walls. Case HI and case HA are simulated with a grid resolution

$_2/$

air flames with isothermal walls, while case HA and case AA are the same flames, but with adiabatic walls. Case HI and case HA are simulated with a grid resolution

![]() $\Delta x^+$

= 2.71 (uniformly 48.4

$\Delta x^+$

= 2.71 (uniformly 48.4

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

m),

$\unicode{x03BC}$

m),

![]() $\Delta z^+$

= 2.189 (uniformly 39.1

$\Delta z^+$

= 2.189 (uniformly 39.1

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

m) and 0.437

$\unicode{x03BC}$

m) and 0.437

![]() $\leqslant \Delta y^+ \leqslant$

1.635 (stretched grids in the wall-normal direction from 7.8–29.2

$\leqslant \Delta y^+ \leqslant$

1.635 (stretched grids in the wall-normal direction from 7.8–29.2

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

m). Case AI and case AA are simulated with a grid resolution

$\unicode{x03BC}$

m). Case AI and case AA are simulated with a grid resolution

![]() $\Delta x^+$

= 2.023 (uniformly 32.3

$\Delta x^+$

= 2.023 (uniformly 32.3

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

m),

$\unicode{x03BC}$

m),

![]() $\Delta z^+$

= 2.448 (uniformly 39.

$\Delta z^+$

= 2.448 (uniformly 39.

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

m) and 0.326

$\unicode{x03BC}$

m) and 0.326

![]() $\leqslant \Delta y^+ \leqslant$

1.215 (stretched grids in the wall-normal direction from 5.2–19.4

$\leqslant \Delta y^+ \leqslant$

1.215 (stretched grids in the wall-normal direction from 5.2–19.4

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

m). Both resolutions are fine enough to resolve all (wall-) turbulence length scales and flame length scales, with at least 13 grid points within the flame thickness during the FWI process.

$\unicode{x03BC}$

m). Both resolutions are fine enough to resolve all (wall-) turbulence length scales and flame length scales, with at least 13 grid points within the flame thickness during the FWI process.

Apart from the three-dimensional (3-D) turbulent cases, 1-D laminar cases are also simulated to check independently the effects of wall heat loss. The laminar cases are set up similar to the 3-D turbulent cases in the wall-normal (

![]() $y$

) direction, with the same spatial distribution for the initial thermochemical states. Four laminar cases corresponding to those in table 1 are finally simulated, denoted as case HIL, case AIL, case HAL and case AAL in the following discussion.

$y$

) direction, with the same spatial distribution for the initial thermochemical states. Four laminar cases corresponding to those in table 1 are finally simulated, denoted as case HIL, case AIL, case HAL and case AAL in the following discussion.

3. Laminar FWI

To understand the effects of wall heat loss, we first analyse in detail the underlying mechanisms controlling flame thickness during laminar FWIs.

3.1. Definitions of flame thickness

There are different definitions for the flame thickness. It is important to distinguish the differences between those different definitions before the dynamics of flame thickness can be correctly captured during FWIs. In the present study, different definitions are evaluated and compared. Flame thickness can usually be defined based on the surface density function (SDF)

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

as

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

as

on a certain isosurface (3-D)/isoline (2-D)/point (1-D), where

![]() $C$

is the progress variable. If

$C$

is the progress variable. If

![]() $C$

is defined thermally,

$C$

is defined thermally,

then

![]() $\delta _{\!f} = \delta _t$

is called thermal flame thickness. Here,

$\delta _{\!f} = \delta _t$

is called thermal flame thickness. Here,

![]() $T_b$

is the burned gas temperature, usually taken equal to

$T_b$

is the burned gas temperature, usually taken equal to

![]() $T_{ad}$

. On the other hand, if

$T_{ad}$

. On the other hand, if

![]() $C$

is defined chemically,

$C$

is defined chemically,

then

![]() $\delta _{\!f} = \delta _c$

is called chemical flame thickness. Here,

$\delta _{\!f} = \delta _c$

is called chemical flame thickness. Here,

![]() $Y_{k,u}$

and

$Y_{k,u}$

and

![]() $Y_{k,b}$

are mass fractions of species

$Y_{k,b}$

are mass fractions of species

![]() $k$

in the unburned and burned gas, respectively. In the present study we have chosen Y

$k$

in the unburned and burned gas, respectively. In the present study we have chosen Y

![]() $_{{{\rm H}_2{\rm O}}}$

in (3.3) to define the chemical progress variable

$_{{{\rm H}_2{\rm O}}}$

in (3.3) to define the chemical progress variable

![]() $C_{k}$

. During the FWI process,

$C_{k}$

. During the FWI process,

![]() $T_u$

and

$T_u$

and

![]() $Y_{k,u}$

might change with time, especially for an adiabatic wall. To make this scale time-independent, we use the initial values of

$Y_{k,u}$

might change with time, especially for an adiabatic wall. To make this scale time-independent, we use the initial values of

![]() $T_u$

and

$T_u$

and

![]() $Y_{k,u}$

before flame quenching for the normalisation in (3.2) and (3.3). There are several ways to choose a value of

$Y_{k,u}$

before flame quenching for the normalisation in (3.2) and (3.3). There are several ways to choose a value of

![]() $C$

to calculate the flame thickness, these are as follows.

$C$

to calculate the flame thickness, these are as follows.

-

(i) Method 1: value of

$C$

where the instantaneous peak heat release rate (HRR)/fuel consumption rate is found.

$C$

where the instantaneous peak heat release rate (HRR)/fuel consumption rate is found. -

(ii) Method 2:

$C = C^{\ast }$

,

$C = C^{\ast }$

,

$C^{\ast }$

being chosen where HRR reaches a peak value in the corresponding unstretched, freely propagating laminar flame.

$C^{\ast }$

being chosen where HRR reaches a peak value in the corresponding unstretched, freely propagating laminar flame. -

(iii) Method 3: value of

$C$

where the maximum gradient of

$C$

where the maximum gradient of

$C$

is located.

$C$

is located.

In principle, these three definitions are consistent for unstretched freely propagating laminar flames. However, during FWIs, there are obvious discrepancies between these definitions. Especially, the value of

![]() $C$

in method 1 is not constant any more during FWIs, as shown in figure 29 in Appendix C. In the present study, all these three choices are evaluated for both the thermal and chemical flame thickness, so that

$C$

in method 1 is not constant any more during FWIs, as shown in figure 29 in Appendix C. In the present study, all these three choices are evaluated for both the thermal and chemical flame thickness, so that

![]() $\delta _{c1}$

,

$\delta _{c1}$

,

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

and

$\delta _{c2}$

and

![]() $\delta _{c3}$

represent chemical flame thickness defined with method 1, 2 and 3, respectively, and

$\delta _{c3}$

represent chemical flame thickness defined with method 1, 2 and 3, respectively, and

![]() $\delta _{t1}$

,

$\delta _{t1}$

,

![]() $\delta _{t2}$

and

$\delta _{t2}$

and

![]() $\delta _{t3}$

represent thermal flame thickness defined with these same methods. In the following discussion, all the thicknesses are normalised by the laminar flame thickness

$\delta _{t3}$

represent thermal flame thickness defined with these same methods. In the following discussion, all the thicknesses are normalised by the laminar flame thickness

![]() $\delta _L$

, to become

$\delta _L$

, to become

![]() $\delta _k^{\ast }$

=

$\delta _k^{\ast }$

=

![]() $\delta _k/\delta _L$

(

$\delta _k/\delta _L$

(

![]() $k = c1,c2,\ldots ,t3$

).

$k = c1,c2,\ldots ,t3$

).

Figure 3 depicts the time evolution of

![]() $1/{\delta _k^{\ast }}$

during FWI in case HIL (figure 3

a) and case HAL (figure 3

b). The evolution of the Peclet number (denoted as Pe) is also shown. This quantity describes the normalised flame–wall distance as Pe =

$1/{\delta _k^{\ast }}$

during FWI in case HIL (figure 3

a) and case HAL (figure 3

b). The evolution of the Peclet number (denoted as Pe) is also shown. This quantity describes the normalised flame–wall distance as Pe =

![]() $d/\delta _z$

(Bruneaux et al. Reference Bruneaux, Akselvoll, Poinsot and Ferziger1996), with

$d/\delta _z$

(Bruneaux et al. Reference Bruneaux, Akselvoll, Poinsot and Ferziger1996), with

![]() $d$

the mean flame–wall distance and

$d$

the mean flame–wall distance and

![]() $\delta _z = \lambda _u/(\rho _uc_pS_L)$

the Zel’dovich flame thickness, where

$\delta _z = \lambda _u/(\rho _uc_pS_L)$

the Zel’dovich flame thickness, where

![]() $\lambda _u, \rho _u$

and

$\lambda _u, \rho _u$

and

![]() $c_p$

denote the thermal diffusion coefficient, density and heat capacity of the unburned mixture, respectively. As shown, the flame quenches at

$c_p$

denote the thermal diffusion coefficient, density and heat capacity of the unburned mixture, respectively. As shown, the flame quenches at

![]() $t\boldsymbol{\cdot }S_L/\delta _L \approx 13.45$

in case HIL and at

$t\boldsymbol{\cdot }S_L/\delta _L \approx 13.45$

in case HIL and at

![]() $t\boldsymbol{\cdot }S_L/\delta _L \approx 13.35$

in case HAL. All flame thicknesses begin to change shortly before the quenching time, apart from

$t\boldsymbol{\cdot }S_L/\delta _L \approx 13.35$

in case HAL. All flame thicknesses begin to change shortly before the quenching time, apart from

![]() $\delta _{t3}^\ast$

, which reacts much earlier. This is because the value of

$\delta _{t3}^\ast$

, which reacts much earlier. This is because the value of

![]() $\max |\boldsymbol{\nabla }T|$

is very sensitive to the near-wall temperature profile, which is affected much earlier than flame quenching, corresponding to a zone of influence much larger than the quenching zone (Poinsot et al. Reference Poinsot, Haworth and Bruneaux1993; Gruber et al. Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Wang and Chakraborty2018). By inspecting the trends of flame thickness variation during FWIs, it can be observed that all chemical thicknesses are increasing, while thermal thicknesses are decreasing in the isothermal wall case and increasing in the adiabatic wall case. Especially,

$\max |\boldsymbol{\nabla }T|$

is very sensitive to the near-wall temperature profile, which is affected much earlier than flame quenching, corresponding to a zone of influence much larger than the quenching zone (Poinsot et al. Reference Poinsot, Haworth and Bruneaux1993; Gruber et al. Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Wang and Chakraborty2018). By inspecting the trends of flame thickness variation during FWIs, it can be observed that all chemical thicknesses are increasing, while thermal thicknesses are decreasing in the isothermal wall case and increasing in the adiabatic wall case. Especially,

![]() $\delta _{t3}^\ast$

is decreasing rapidly in the isothermal wall case, which matches well with the recent findings in De Nardi et al. (Reference De Nardi, Douasbin, Vermorel and Poinsot2024) (who used

$\delta _{t3}^\ast$

is decreasing rapidly in the isothermal wall case, which matches well with the recent findings in De Nardi et al. (Reference De Nardi, Douasbin, Vermorel and Poinsot2024) (who used

![]() $\delta _{t3}$

to represent the flame thickness), while

$\delta _{t3}$

to represent the flame thickness), while

![]() $\delta _{c2}^\ast$

is increasing in the isothermal wall case, consistent with the findings in Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010) and Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Wang and Chakraborty2018) (who used

$\delta _{c2}^\ast$

is increasing in the isothermal wall case, consistent with the findings in Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010) and Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Wang and Chakraborty2018) (who used

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

to represent the flame thickness). The opposite evolutions coming with the different flame thickness definitions indicate the importance of a clear and founded choice, since it would affect all final conclusions concerning the dynamics of flame thickness during FWIs. From a physical point of view, the value of

$\delta _{c2}$

to represent the flame thickness). The opposite evolutions coming with the different flame thickness definitions indicate the importance of a clear and founded choice, since it would affect all final conclusions concerning the dynamics of flame thickness during FWIs. From a physical point of view, the value of

![]() $C$

in method 1 appears preferable to identify the flame position. However, the flame surface defined by method 1 is not as easy to track as by method 2, while the evolutions of flame thickness computed using method 2 are similar to those using method 1. Comparing chemical and thermal thicknesses, the latter one is not recommended since the temperature profile (used to calculate the thermal thickness) is significantly influenced by the wall heat flux during FWIs. Most previous FWI studies (e.g. Gruber et al. Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Wang and Chakraborty2018) defined flame thickness as

$C$

in method 1 appears preferable to identify the flame position. However, the flame surface defined by method 1 is not as easy to track as by method 2, while the evolutions of flame thickness computed using method 2 are similar to those using method 1. Comparing chemical and thermal thicknesses, the latter one is not recommended since the temperature profile (used to calculate the thermal thickness) is significantly influenced by the wall heat flux during FWIs. Most previous FWI studies (e.g. Gruber et al. Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Wang and Chakraborty2018) defined flame thickness as

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

. As a consequence, the discussion in this section will focus on the chemical flame thicknesses defined using method 2, i.e.

$\delta _{c2}$

. As a consequence, the discussion in this section will focus on the chemical flame thicknesses defined using method 2, i.e.

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

. Still, in order to enable comparisons, the thermal flame thickness

$\delta _{c2}$

. Still, in order to enable comparisons, the thermal flame thickness

![]() $\delta _{t2}$

is also provided.

$\delta _{t2}$

is also provided.

Figure 3. Time evolution of the SDF (

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C| \boldsymbol{\cdot }\delta _L$

) with six different definitions of the flame thickness during laminar FWI in cases with (a) an isothermal wall and (b) an adiabatic wall. The blue dashed line in (b) is overlapped with the green dashed line.

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C| \boldsymbol{\cdot }\delta _L$

) with six different definitions of the flame thickness during laminar FWI in cases with (a) an isothermal wall and (b) an adiabatic wall. The blue dashed line in (b) is overlapped with the green dashed line.

3.2. Effect of wall heat loss on flame thickness

In this section the effect of wall heat loss on

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

and

$\delta _{c2}$

and

![]() $\delta _{t2}$

during FWIs are analysed in detail. By comparing the isothermal and adiabatic wall cases in figure 3, it is observed that the chemical thickness

$\delta _{t2}$

during FWIs are analysed in detail. By comparing the isothermal and adiabatic wall cases in figure 3, it is observed that the chemical thickness

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

also increases rapidly even without wall heat loss, indicating that the effect of wall heat loss is limited regarding the trend of chemical thickness during FWIs. In the opposite, the trends of

$\delta _{c2}$

also increases rapidly even without wall heat loss, indicating that the effect of wall heat loss is limited regarding the trend of chemical thickness during FWIs. In the opposite, the trends of

![]() $\delta _{t2}$

with either isothermal or adiabatic walls are completely different. This will be explained later. Since the flame surfaces of

$\delta _{t2}$

with either isothermal or adiabatic walls are completely different. This will be explained later. Since the flame surfaces of

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

and

$\delta _{c2}$

and

![]() $\delta _{t2}$

are collected at a constant value

$\delta _{t2}$

are collected at a constant value

![]() $C = C^{\ast }$

, using the equation governing the evolution of SDF

$C = C^{\ast }$

, using the equation governing the evolution of SDF

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

is interesting:

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

is interesting:

Here,

![]() $\boldsymbol {n} = -\boldsymbol{\nabla }C/|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

is the flame normal vector pointing to the unburned gas side,

$\boldsymbol {n} = -\boldsymbol{\nabla }C/|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

is the flame normal vector pointing to the unburned gas side,

![]() $a_n = \boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol {n}: \boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol {u}$

is the flame normal strain rate,

$a_n = \boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol {n}: \boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol {u}$

is the flame normal strain rate,

![]() $a_{n,{\textit{eff}}}$

is the effective normal strain rate and

$a_{n,{\textit{eff}}}$

is the effective normal strain rate and

![]() $S_d$

is the flame displacement speed, which can be calculated chemically through

$S_d$

is the flame displacement speed, which can be calculated chemically through

\begin{equation} S_d = S_{d,C} = \underbrace {\frac {\dot {\omega }_C}{\rho |\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|}}_{S_{d,{\textit{react}}}} + \underbrace {\frac {\boldsymbol{\nabla }(\rho D_C \boldsymbol{\nabla }C)}{\rho |\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|}}_{S_{d,{\textit{diff}}}}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} S_d = S_{d,C} = \underbrace {\frac {\dot {\omega }_C}{\rho |\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|}}_{S_{d,{\textit{react}}}} + \underbrace {\frac {\boldsymbol{\nabla }(\rho D_C \boldsymbol{\nabla }C)}{\rho |\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|}}_{S_{d,{\textit{diff}}}}, \end{equation}

with

![]() $C$

denoting the chemical progress variable defined using Y

$C$

denoting the chemical progress variable defined using Y

![]() $_{{{\rm H}_2{\rm O}}}$

. In (3.5),

$_{{{\rm H}_2{\rm O}}}$

. In (3.5),

![]() $\dot {\omega }_C$

is the reaction source term of

$\dot {\omega }_C$

is the reaction source term of

![]() $C$

and

$C$

and

![]() $D_C$

is the diffusion coefficient of

$D_C$

is the diffusion coefficient of

![]() $C$

(here

$C$

(here

![]() $D_C = D_{{{\rm H}_2{\rm O}}}$

). The chemical flame displacement speed

$D_C = D_{{{\rm H}_2{\rm O}}}$

). The chemical flame displacement speed

![]() $S_{d,C}$

can be divided into the reaction term

$S_{d,C}$

can be divided into the reaction term

![]() $S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

and diffusion term

$S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

and diffusion term

![]() $S_{d,{\textit{diff}}}$

, as shown in (3.5). Alternatively,

$S_{d,{\textit{diff}}}$

, as shown in (3.5). Alternatively,

![]() $S_d$

can also be calculated thermally through

$S_d$

can also be calculated thermally through

\begin{equation} S_d = S_{d,T} = \underbrace {\frac {\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{\cdot }(\lambda \boldsymbol{\nabla }T)}{\rho C_p|\boldsymbol{\nabla }T|}}_{S_{d,{\textit{diff}}}} +\underbrace {\frac {\boldsymbol{\nabla }T \boldsymbol{\cdot }\sum _k(D_k C_{p,k} \boldsymbol{\nabla }Y_k)}{C_p|\boldsymbol{\nabla }T|}}_{S_{d,{\textit{md}}}}+\underbrace {\frac {-\sum _k h_k\dot {\omega }_k}{\rho C_p|\boldsymbol{\nabla }T|}}_{S_{d,{\textit{react}}}}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} S_d = S_{d,T} = \underbrace {\frac {\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{\cdot }(\lambda \boldsymbol{\nabla }T)}{\rho C_p|\boldsymbol{\nabla }T|}}_{S_{d,{\textit{diff}}}} +\underbrace {\frac {\boldsymbol{\nabla }T \boldsymbol{\cdot }\sum _k(D_k C_{p,k} \boldsymbol{\nabla }Y_k)}{C_p|\boldsymbol{\nabla }T|}}_{S_{d,{\textit{md}}}}+\underbrace {\frac {-\sum _k h_k\dot {\omega }_k}{\rho C_p|\boldsymbol{\nabla }T|}}_{S_{d,{\textit{react}}}}, \end{equation}

where

![]() $\lambda$

is the thermal diffusion coefficient,

$\lambda$

is the thermal diffusion coefficient,

![]() $C_p$

is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure,

$C_p$

is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure,

![]() $D_k$

,

$D_k$

,

![]() $C_{p,k}$

,

$C_{p,k}$

,

![]() $h_k$

and

$h_k$

and

![]() $\dot {\omega }_k$

are the diffusion coefficient, species heat capacity, specific enthalpy and mass production rate of species

$\dot {\omega }_k$

are the diffusion coefficient, species heat capacity, specific enthalpy and mass production rate of species

![]() $k$

, respectively. Thermally,

$k$

, respectively. Thermally,

![]() $S_{d,T}$

can be divided into the reaction term

$S_{d,T}$

can be divided into the reaction term

![]() $S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

, mass diffusion term

$S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

, mass diffusion term

![]() $S_{d,{\textit{md}}}$

and thermal diffusion term

$S_{d,{\textit{md}}}$

and thermal diffusion term

![]() $S_{d,{\textit{diff}}}$

. From our preliminary tests,

$S_{d,{\textit{diff}}}$

. From our preliminary tests,

![]() $S_{d,{\textit{md}}}$

is orders of magnitude smaller than the other two terms, even during FWIs. Therefore, this term is neglected in the following analysis.

$S_{d,{\textit{md}}}$

is orders of magnitude smaller than the other two terms, even during FWIs. Therefore, this term is neglected in the following analysis.

Following (3.4), we check the time evolution of

![]() $a_{n,{\textit{eff}}}$

,

$a_{n,{\textit{eff}}}$

,

![]() $a_n$

and

$a_n$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_d$

during the FWI process, as shown in figure 4. It is observed that the trend of

$\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_d$

during the FWI process, as shown in figure 4. It is observed that the trend of

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

in figure 3 matches quite well with the value of

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

in figure 3 matches quite well with the value of

![]() $a_{n,{\textit{eff}}}$

in figure 4, with decreasing (respectively increasing) trend of

$a_{n,{\textit{eff}}}$

in figure 4, with decreasing (respectively increasing) trend of

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

for positive (respectively negative)

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

for positive (respectively negative)

![]() $a_{n,{\textit{eff}}}$

. The large positive

$a_{n,{\textit{eff}}}$

. The large positive

![]() $a_{n,{\textit{eff}}}$

for

$a_{n,{\textit{eff}}}$

for

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

in both cases is dominated by the large positive value of

$\delta _{c2}$

in both cases is dominated by the large positive value of

![]() $\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_d$

. On the other hand, the variation of normal strain rate

$\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_d$

. On the other hand, the variation of normal strain rate

![]() $a_n$

is relatively mild during the flame quenching process. The effect of wall heat loss on

$a_n$

is relatively mild during the flame quenching process. The effect of wall heat loss on

![]() $a_n$

is obvious, with an increasing trend for

$a_n$

is obvious, with an increasing trend for

![]() $a_n$

in the adiabatic wall case and a decreasing trend in the isothermal wall case. This indicates that wall heat loss tends to decrease the normal strain rate

$a_n$

in the adiabatic wall case and a decreasing trend in the isothermal wall case. This indicates that wall heat loss tends to decrease the normal strain rate

![]() $a_n$

, by weakening the thermal expansion effect, therefore increasing

$a_n$

, by weakening the thermal expansion effect, therefore increasing

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

and decreasing the flame thickness. However, since the overall trend of

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

and decreasing the flame thickness. However, since the overall trend of

![]() $a_{n,{\textit{eff}}}$

is dominated by

$a_{n,{\textit{eff}}}$

is dominated by

![]() $\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_d$

and not

$\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_d$

and not

![]() $a_n$

, the effect of wall heat loss is overall negligible.

$a_n$

, the effect of wall heat loss is overall negligible.

Figure 4. Time evolution of the effective normal strain rate, flame normal strain rate and flame speed gradient on the chemical and thermal flame fronts during the FWI process in cases with (a) an isothermal wall and (b) an adiabatic wall.

To determine the key factors resulting in the rapid increase of

![]() $\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_d$

for

$\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_d$

for

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

during FWIs, the reaction and diffusion components are plotted separately in figure 5. In both cases, the reaction part increases rapidly and dominates the increase of

$\delta _{c2}$

during FWIs, the reaction and diffusion components are plotted separately in figure 5. In both cases, the reaction part increases rapidly and dominates the increase of

![]() $\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_d$

for

$\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_d$

for

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

. Therefore, the increase of

$\delta _{c2}$

. Therefore, the increase of

![]() $\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_d$

for

$\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_d$

for

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

in both cases are closely related to the increase of

$\delta _{c2}$

in both cases are closely related to the increase of

![]() $\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

at

$\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

at

![]() $C = C^{\ast }$

. Figure 6 further shows the distributions of

$C = C^{\ast }$

. Figure 6 further shows the distributions of

![]() $S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

and

$S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

and

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

at five sequential time instants during the FWI process in case HAL. As shown, due to the zero-diffusion flux boundary condition for species (

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

at five sequential time instants during the FWI process in case HAL. As shown, due to the zero-diffusion flux boundary condition for species (

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C| = 0$

) on the wall,

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C| = 0$

) on the wall,

![]() $S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

gradually increases near the wall as the flame approaches, resulting in a rapid decrease of

$S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

gradually increases near the wall as the flame approaches, resulting in a rapid decrease of

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

and thereby increase of

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

and thereby increase of

![]() $\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

, ultimately increasing

$\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

, ultimately increasing

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

. On the other hand, for the thermal thickness

$\delta _{c2}$

. On the other hand, for the thermal thickness

![]() $\delta _{t2}$

, while the trend is similar to

$\delta _{t2}$

, while the trend is similar to

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

in the adiabatic case (as shown in figures 3

b, 4

b, 5

b), it is completely different in the isothermal case. This is because the isothermal wall does not have a constraint

$\delta _{c2}$

in the adiabatic case (as shown in figures 3

b, 4

b, 5

b), it is completely different in the isothermal case. This is because the isothermal wall does not have a constraint

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }T| = 0$

for the thermal diffusion flux, so that the reaction term

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }T| = 0$

for the thermal diffusion flux, so that the reaction term

![]() $\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

(figure 5

a) does not increase rapidly, as it does in the adiabatic case (figure 5

b) during FWIs. There is even a slight decrease of

$\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

(figure 5

a) does not increase rapidly, as it does in the adiabatic case (figure 5

b) during FWIs. There is even a slight decrease of

![]() $\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_d$

and of

$\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }S_d$

and of

![]() $a_{n,{\textit{eff}}}$

below zero during the flame quenching process, resulting in a decrease of

$a_{n,{\textit{eff}}}$

below zero during the flame quenching process, resulting in a decrease of

![]() $\delta _{t2}$

in the isothermal wall case. This explains the different trends observed for

$\delta _{t2}$

in the isothermal wall case. This explains the different trends observed for

![]() $\delta _{t2}$

for isothermal or adiabatic walls as already discussed in connection with figure 3.

$\delta _{t2}$

for isothermal or adiabatic walls as already discussed in connection with figure 3.

Figure 5. Time evolution of the flame speed gradient with reaction and diffusion contributions on the chemical (continuous lines) and thermal (dashed lines) flame fronts during the FWI process in cases with (a) an isothermal wall and (b) an adiabatic wall.

To conclude, the major reason for the increase of chemical flame thickness

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

during the FWI process is the zero-flux boundary condition for species diffusion on the wall. Note that a small diffusion flux boundary condition (

$\delta _{c2}$

during the FWI process is the zero-flux boundary condition for species diffusion on the wall. Note that a small diffusion flux boundary condition (

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C| = \epsilon$

with

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C| = \epsilon$

with

![]() $\epsilon \approx 0$

), which is more realistic, would also result in a significant increase of chemical flame thickness, based on the analysis in figure 6. Therefore, the above conclusion is still valid for realistic walls with a very small diffusion flux for species. Wall heat loss tends to decrease the chemical flame thickness, while this effect is negligible and overridden by the effect of wall boundary condition with

$\epsilon \approx 0$

), which is more realistic, would also result in a significant increase of chemical flame thickness, based on the analysis in figure 6. Therefore, the above conclusion is still valid for realistic walls with a very small diffusion flux for species. Wall heat loss tends to decrease the chemical flame thickness, while this effect is negligible and overridden by the effect of wall boundary condition with

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C| = 0$

for species. For an adiabatic wall, both the chemical and thermal flame thickness increase due to the zero-diffusion flux boundary condition for both species and temperature (

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C| = 0$

for species. For an adiabatic wall, both the chemical and thermal flame thickness increase due to the zero-diffusion flux boundary condition for both species and temperature (

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }T| = 0$

). For an isothermal wall (

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }T| = 0$

). For an isothermal wall (

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }T| \neq 0$

on the wall), the chemical flame thickness increases due to

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }T| \neq 0$

on the wall), the chemical flame thickness increases due to

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C| = 0$

for species on the wall, while the thermal flame thickness decreases further due to wall heat loss.

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C| = 0$

for species on the wall, while the thermal flame thickness decreases further due to wall heat loss.

Figure 6. Distributions of

![]() $S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

(dashed lines) and

$S_{d,{\textit{react}}}$

(dashed lines) and

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

(solid lines) during the FWI process in case HAL, showing the time instants

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

(solid lines) during the FWI process in case HAL, showing the time instants

![]() $t_1 = 13.28\delta _L/S_L$

,

$t_1 = 13.28\delta _L/S_L$

,

![]() $t_2 = 13.3\delta _L/S_L$

,

$t_2 = 13.3\delta _L/S_L$

,

![]() $t_3 = 13.32\delta _L/S_L$

,

$t_3 = 13.32\delta _L/S_L$

,

![]() $t_4 = 13.34\delta _L/S_L$

and

$t_4 = 13.34\delta _L/S_L$

and

![]() $t_5 = 13.35\delta _L/S_L$

.

$t_5 = 13.35\delta _L/S_L$

.

Note that, in the present study, we only consider inert walls without any heterogeneous or catalytic reactions. For a chemically active wall, the constraint

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C| = 0$

would fall for species, with the following boundary condition regarding species diffusion flux j

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C| = 0$

would fall for species, with the following boundary condition regarding species diffusion flux j

![]() $_k$

(De Nardi et al. Reference De Nardi, Douasbin, Vermorel and Poinsot2024):

$_k$

(De Nardi et al. Reference De Nardi, Douasbin, Vermorel and Poinsot2024):

Here

![]() $\dot {s}_k$

is the surface reaction source term for species

$\dot {s}_k$

is the surface reaction source term for species

![]() $k$

. The effect of a non-zero species diffusion flux at the wall on the chemical flame thickness during FWIs might be completely different from what is discussed in the present work and needs to be investigated in future studies.

$k$

. The effect of a non-zero species diffusion flux at the wall on the chemical flame thickness during FWIs might be completely different from what is discussed in the present work and needs to be investigated in future studies.

4. Turbulent FWI

After concentrating on wall heat loss and revealing the underlying mechanism for the increase of chemical flame thickness during a laminar FWI process, this section focuses on the effect of wall turbulence on flame thickness. In this section we select the flame thickness defined by

![]() $\delta _{c1}$

, since this definition is more precise than

$\delta _{c1}$

, since this definition is more precise than

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

during a turbulent FWI process, as will be proved in the following discussion. Because of the very similar behaviours of

$\delta _{c2}$

during a turbulent FWI process, as will be proved in the following discussion. Because of the very similar behaviours of

![]() $\delta _{c1}$

and

$\delta _{c1}$

and

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

shown in figure 3, the underlying mechanism analysed in the previous section for

$\delta _{c2}$

shown in figure 3, the underlying mechanism analysed in the previous section for

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

should also be valid for

$\delta _{c2}$

should also be valid for

![]() $\delta _{c1}$

, though we do not know the governing equation for SDF

$\delta _{c1}$

, though we do not know the governing equation for SDF

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

on the flame surface defined by method 1. The chemical flame thickness

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

on the flame surface defined by method 1. The chemical flame thickness

![]() $1/|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

(either

$1/|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C|$

(either

![]() $\delta _{c1}$

or

$\delta _{c1}$

or

![]() $\delta _{c2}$

) will always be heavily affected by the zero species diffusion flux

$\delta _{c2}$

) will always be heavily affected by the zero species diffusion flux

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C| = 0$

boundary condition on the inert wall. In the following analysis, the flame–wall distance (characterised by the Peclet number) is also obtained based on the corresponding flame surface (defined by method 1). Note that different choices of the flame surface would slightly affect the quenching Peclet number. However, conclusions in the present study do not depend on this choice.

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C| = 0$

boundary condition on the inert wall. In the following analysis, the flame–wall distance (characterised by the Peclet number) is also obtained based on the corresponding flame surface (defined by method 1). Note that different choices of the flame surface would slightly affect the quenching Peclet number. However, conclusions in the present study do not depend on this choice.

4.1. Turbulent flame surface identification

A flame surface defined by method 1 previously defined in § 3 is much more difficult to be clearly identified in turbulent flames due to the quenching process, compared with method 2. An accurate identification of this flame surface is crucial for a reliable calculation of

![]() $\delta _{c1}$

. In the present study, a ridge-based flame surface detection method has been developed, based on the recent studies in Rochette et al. (Reference Rochette, Riber, Cuenot and Vermorel2020) and Schießl & Bykov (Reference Schießl and Bykov2022). First, a Hessian matrix is numerically constructed, i.e.

$\delta _{c1}$

. In the present study, a ridge-based flame surface detection method has been developed, based on the recent studies in Rochette et al. (Reference Rochette, Riber, Cuenot and Vermorel2020) and Schießl & Bykov (Reference Schießl and Bykov2022). First, a Hessian matrix is numerically constructed, i.e.

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol {H} = \left [\begin{matrix} \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial x^2} & \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial x \partial y} & \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial x \partial z}\\[9pt] \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial x \partial y} & \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial y^2} & \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial y \partial z} \\[9pt] \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial x \partial z} & \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial y \partial z} & \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial z^2} \end{matrix}\right ]\! ,\end{equation}

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol {H} = \left [\begin{matrix} \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial x^2} & \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial x \partial y} & \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial x \partial z}\\[9pt] \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial x \partial y} & \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial y^2} & \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial y \partial z} \\[9pt] \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial x \partial z} & \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial y \partial z} & \dfrac {\partial ^2 f}{\partial z^2} \end{matrix}\right ]\! ,\end{equation}

where

![]() $f$

is the mass production rate of H

$f$

is the mass production rate of H

![]() $_2$

(

$_2$

(

![]() $\dot {\omega }_{{{\rm H}_2}}$

) for the H

$\dot {\omega }_{{{\rm H}_2}}$

) for the H

![]() $_2/$

air flames and HRR (

$_2/$

air flames and HRR (

![]() $\dot {Q}$

) for the NH

$\dot {Q}$

) for the NH

![]() $_3/$

H

$_3/$

H

![]() $_2/$

air flames in the present study. Note that

$_2/$

air flames in the present study. Note that

![]() $\dot {Q}$

would increase rapidly very close to the wall in the H

$\dot {Q}$

would increase rapidly very close to the wall in the H

![]() $_2/$

air flames due to the near-wall radical recombination reactions; therefore, the peak position of

$_2/$

air flames due to the near-wall radical recombination reactions; therefore, the peak position of

![]() $\dot {\omega }_{{{\rm H}_2}}$

is usually used to indicate the flame position (Dabireau et al. Reference Dabireau, Cuenot, Vermorel and Poinsot2003; Chi et al. Reference Chi, Yu, Cuenot, Maas and Thévenin2024). Though different quantities are used to analyse the H

$\dot {\omega }_{{{\rm H}_2}}$

is usually used to indicate the flame position (Dabireau et al. Reference Dabireau, Cuenot, Vermorel and Poinsot2003; Chi et al. Reference Chi, Yu, Cuenot, Maas and Thévenin2024). Though different quantities are used to analyse the H

![]() $_2/$

air and NH

$_2/$

air and NH

![]() $_3/$

H

$_3/$

H

![]() $_2/$

air flames, these two indicators both track the most reactive region related to fuel combustion, accurately representing the real flame front position of the corresponding flame. A sensitivity analysis of

$_2/$

air flames, these two indicators both track the most reactive region related to fuel combustion, accurately representing the real flame front position of the corresponding flame. A sensitivity analysis of

![]() $\dot {Q}$

and

$\dot {Q}$

and

![]() $\dot {\omega }_{fuel}$

for the flame front representation is shown in Appendix E and demonstrates the negligible discrepancies between peak positions of both quantities. Therefore, the following analysis based on these two quantities is consistent, delivers physically meaningful findings and can be used for direct comparisons. The Hessian matrix can be decomposed into

$\dot {\omega }_{fuel}$

for the flame front representation is shown in Appendix E and demonstrates the negligible discrepancies between peak positions of both quantities. Therefore, the following analysis based on these two quantities is consistent, delivers physically meaningful findings and can be used for direct comparisons. The Hessian matrix can be decomposed into

where

![]() $\mathrm{\boldsymbol{\varLambda }}$

contains the eigenvalues

$\mathrm{\boldsymbol{\varLambda }}$

contains the eigenvalues

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{\varLambda } = \left [\begin{matrix} \lambda _1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \lambda _2 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \lambda _3 \end{matrix}\right ] \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{\varLambda } = \left [\begin{matrix} \lambda _1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \lambda _2 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \lambda _3 \end{matrix}\right ] \end{equation}

and

![]() $\boldsymbol {A}$

contains the corresponding left eigenvectors

$\boldsymbol {A}$

contains the corresponding left eigenvectors

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol {A} = \left [\begin{matrix} | & | & | \\ \boldsymbol{v}_1 & \boldsymbol{v}_2 & \boldsymbol{v}_3 \\ | & | & | \end{matrix}\right ]\!. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol {A} = \left [\begin{matrix} | & | & | \\ \boldsymbol{v}_1 & \boldsymbol{v}_2 & \boldsymbol{v}_3 \\ | & | & | \end{matrix}\right ]\!. \end{equation}

The eigenvalues

![]() $\lambda _1$

,

$\lambda _1$

,

![]() $\lambda _2$

and

$\lambda _2$

and

![]() $\lambda _3$

represent the principal curvatures in

$\lambda _3$

represent the principal curvatures in

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}_1$

,

$\boldsymbol{v}_1$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}_2$

and

$\boldsymbol{v}_2$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}_3$

directions, respectively. The eigenvector

$\boldsymbol{v}_3$

directions, respectively. The eigenvector

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}_m$

associated to the largest absolute eigenvalue/curvature (

$\boldsymbol{v}_m$

associated to the largest absolute eigenvalue/curvature (

![]() $|\lambda _m| = \max |\lambda _k|$

with

$|\lambda _m| = \max |\lambda _k|$

with

![]() $k = 1,2,3$

) therefore represents the direction of flame propagation. To be on the flame front,

$k = 1,2,3$

) therefore represents the direction of flame propagation. To be on the flame front,

![]() $\lambda _m \gt 0$

if

$\lambda _m \gt 0$

if

![]() $f = \dot {\omega }_{{{\rm H}_2}}$

(convex to the valley) and

$f = \dot {\omega }_{{{\rm H}_2}}$

(convex to the valley) and

![]() $\lambda _m \lt 0$

if

$\lambda _m \lt 0$

if

![]() $f = \dot {Q}$

(concave to the peak) must be satisfied. To identify the ridge surface (in 3-D)/line (in 2-D), we can plot the projection of

$f = \dot {Q}$

(concave to the peak) must be satisfied. To identify the ridge surface (in 3-D)/line (in 2-D), we can plot the projection of

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }\!f$

in the direction of

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }\!f$

in the direction of

![]() $\lambda _m$

:

$\lambda _m$

:

Then, the ridge can be identified as the iso-surface/line with

![]() $g(\boldsymbol{x}) = 0$

. Since the direction of

$g(\boldsymbol{x}) = 0$

. Since the direction of

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}_m$

is not guaranteed to be consistent (e.g. always pointing towards the fresh gas side), it is difficult to directly use (4.5) to identify the ridge surface/line, as shown in figure 7(a). Thereby, a modified formulation for the ridge function

$\boldsymbol{v}_m$

is not guaranteed to be consistent (e.g. always pointing towards the fresh gas side), it is difficult to directly use (4.5) to identify the ridge surface/line, as shown in figure 7(a). Thereby, a modified formulation for the ridge function

![]() $g(\boldsymbol{x})$

is proposed as

$g(\boldsymbol{x})$

is proposed as

where

![]() $\boldsymbol {n}$

is the flame normal vector and ‘sign’ is the signum function (−1 for negative inputs and 1 for positive inputs). In this way, the direction of

$\boldsymbol {n}$

is the flame normal vector and ‘sign’ is the signum function (−1 for negative inputs and 1 for positive inputs). In this way, the direction of

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}_m$

is ensured to be consistent with the flame normal direction (direction of

$\boldsymbol{v}_m$

is ensured to be consistent with the flame normal direction (direction of

![]() $\boldsymbol {n}$

) and finally the ridge surface/line can be correctly captured, as shown in figure 7(b). To summarise, the following two steps are used to identify the ridge-based flame surface.

$\boldsymbol {n}$

) and finally the ridge surface/line can be correctly captured, as shown in figure 7(b). To summarise, the following two steps are used to identify the ridge-based flame surface.

-

(i) Compute the eigenvalue of the Hessian matrix with the largest absolute value:

(4.7) \begin{align} \lambda _m= \begin{cases} \gt 0 & \text{if } f = \dot {\omega }_{{{\rm H}_2}},\\ \lt 0 & \text{if } f = \dot {Q}. \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} \lambda _m= \begin{cases} \gt 0 & \text{if } f = \dot {\omega }_{{{\rm H}_2}},\\ \lt 0 & \text{if } f = \dot {Q}. \end{cases} \end{align}

-

(ii) Determine the modified ridge function

(4.8) \begin{align} g(\boldsymbol{x}) = \mathrm{sign}(\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v}_m) \boldsymbol{\nabla }\!f \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v}_m = 0. \end{align}

\begin{align} g(\boldsymbol{x}) = \mathrm{sign}(\boldsymbol {n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v}_m) \boldsymbol{\nabla }\!f \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v}_m = 0. \end{align}

Figure 7. Selected two-dimensional (2-D) slice of the result for case HI at

![]() $t = 0.42h/S_L$

. (a) Distribution of the ridge function

$t = 0.42h/S_L$

. (a) Distribution of the ridge function

![]() $g$

following (4.5). (b) Distribution of the ridge function

$g$

following (4.5). (b) Distribution of the ridge function

![]() $g$

following (4.6). (c) Distribution of

$g$

following (4.6). (c) Distribution of

![]() $\dot {\omega }_{{{\rm H}_2}}$

. Both the ridge-based position of the flame front and its position based on a constant value of

$\dot {\omega }_{{{\rm H}_2}}$

. Both the ridge-based position of the flame front and its position based on a constant value of

![]() $C$

are plotted.

$C$

are plotted.

Figure 7(c) compares the flame front obtained using the ridge function (red line) and that obtained for a constant value of

![]() $C = 0.55$

(black line) in case HI. As shown, apart from the local flame extinction events and the wall quenching events, both representations match along the flame front. At flame quenching/extinction, the ridge-based flame front is more accurate since it captures correctly the local peak (respectively valley) of the HRR (respectively fuel reaction rate). The flame front defined with

$C = 0.55$

(black line) in case HI. As shown, apart from the local flame extinction events and the wall quenching events, both representations match along the flame front. At flame quenching/extinction, the ridge-based flame front is more accurate since it captures correctly the local peak (respectively valley) of the HRR (respectively fuel reaction rate). The flame front defined with

![]() $C = 0.55$

would even touch the wall in this case, which is physically impossible during FWIs for a cold isothermal wall. Therefore, it must be kept in mind that previous FWI studies based on a constant value of

$C = 0.55$

would even touch the wall in this case, which is physically impossible during FWIs for a cold isothermal wall. Therefore, it must be kept in mind that previous FWI studies based on a constant value of

![]() $C$

to represent the flame front might lead to incorrect conclusions regarding flame–wall distance and near-wall flame dynamics. To accurately determine such quantities, the ridge-based flame front is systematically considered in this section. For this purpose, the flame normal vector is replaced from

$C$

to represent the flame front might lead to incorrect conclusions regarding flame–wall distance and near-wall flame dynamics. To accurately determine such quantities, the ridge-based flame front is systematically considered in this section. For this purpose, the flame normal vector is replaced from

![]() $\boldsymbol {n}$

to

$\boldsymbol {n}$

to

The flame curvature is calculated as

with positive curvature associated to a flame front convex toward the fresh gas side.

4.2. Effect of wall turbulence on flame thickness

After ensuring a proper description of the turbulent flame front, the flame thickness/SDF statistics on the flame front can be analysed. Figure 8(a) shows the joint probability density function (PDF) between

![]() $1/{\delta _{c1}^\ast }$

and Pe during the FWI process in case HI. The black line shows the laminar solution, while the blue line shows the conditional averaged value of

$1/{\delta _{c1}^\ast }$

and Pe during the FWI process in case HI. The black line shows the laminar solution, while the blue line shows the conditional averaged value of

![]() $1/{\delta _{c1}^\ast }$

with Pe in the turbulent case. In the present study the conditional averaged value of any scalar quantity

$1/{\delta _{c1}^\ast }$

with Pe in the turbulent case. In the present study the conditional averaged value of any scalar quantity

![]() $q$

with Pe on the flame front is calculated as

$q$

with Pe on the flame front is calculated as

where

![]() $\delta _s$

is the delta function for the flame surface

$\delta _s$

is the delta function for the flame surface

\begin{align} \delta _s= \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if } g(\boldsymbol{x}) = 0,\\ 0, & \text{otherwise}, \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} \delta _s= \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if } g(\boldsymbol{x}) = 0,\\ 0, & \text{otherwise}, \end{cases} \end{align}

and

\begin{align} \delta _d= \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if } {\textit{Pe}} = {\textit{Pe}}^{\ast } ,\\ 0, & \text{otherwise} .\end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} \delta _d= \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if } {\textit{Pe}} = {\textit{Pe}}^{\ast } ,\\ 0, & \text{otherwise} .\end{cases} \end{align}

In figure 8(a) it is observed that the conditional averaged value

![]() $\langle 1/{\delta _{c1}^\ast }\rangle _s|_{{{\textit{Pe}}^{\ast }}}$

in the turbulent case matches quite well with the laminar solution. Especially, both the laminar and turbulence cases have the quenching Peclet number Pe

$\langle 1/{\delta _{c1}^\ast }\rangle _s|_{{{\textit{Pe}}^{\ast }}}$

in the turbulent case matches quite well with the laminar solution. Especially, both the laminar and turbulence cases have the quenching Peclet number Pe

![]() $_Q$

$_Q$

![]() $\approx$

1.2, which is similar to the result in Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010) for H

$\approx$

1.2, which is similar to the result in Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010) for H

![]() $_2/$

air flames. Since it was shown in the previous section that flame thickening in the laminar case is mainly due to the wall boundary condition (

$_2/$

air flames. Since it was shown in the previous section that flame thickening in the laminar case is mainly due to the wall boundary condition (

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C| = 0$

), the turbulence effect can only be checked after filtering out this wall boundary effect. For this purpose, a criterion

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }C| = 0$

), the turbulence effect can only be checked after filtering out this wall boundary effect. For this purpose, a criterion

![]() $|\dot {\omega }_{{{\rm H}_2}}| \gt ({1}/{3})|\dot {\omega }_{{{\rm H}_2}}|_{L,\textit{max}}$

(where

$|\dot {\omega }_{{{\rm H}_2}}| \gt ({1}/{3})|\dot {\omega }_{{{\rm H}_2}}|_{L,\textit{max}}$

(where

![]() $\dot {\omega }_{{{\rm H}_2}}|_{L,\textit{max}}$

is the maximum fuel reaction rate in the corresponding unstretched laminar flame) has been used to extract the flame before it approaches too close to the wall and is heavily affected by the wall boundary condition. The value

$\dot {\omega }_{{{\rm H}_2}}|_{L,\textit{max}}$

is the maximum fuel reaction rate in the corresponding unstretched laminar flame) has been used to extract the flame before it approaches too close to the wall and is heavily affected by the wall boundary condition. The value

![]() ${1}/{3}$