Introduction

Eighty-one species of animals and plants are currently categorized as Extinct in the Wild (IUCN, 2024), surviving only in specialized institutions such as ex situ conservation breeding centres, zoos or botanic gardens. This is the case for many species of French Polynesian tree snails of the family Partulidae. In the Society Islands the genus Partula comprises 51 species, of which at least 29 (possibly 34) are extinct. Of the 17 species known to be extant, 10 survive only in captivity (IUCN, 2024).

Partulidae tree snails were a notable part of the Society Islands’ fauna until the late 20th century. Globally, they were notable in the development of genetics, being the first organisms to be the focus of an attempt to demonstrate the validity of Mendelian genetics in wild species, with the pioneering work of Henry Crampton, and later the phenotypic inheritance studies of Bryan Clarke, James Murray and Michael Johnson (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Murray and Clarke1993). In the Society Islands they were of significant cultural value in the manufacture of hei necklaces, crowns and other ornaments. As highly abundant detritivores they were also probably of great ecological significance (Gerlach, Reference Gerlach2014) although this was never studied. All of these roles came to an end between 1982 and 1995 when almost all wild populations were eliminated by the introduced predator, the rosy wolfsnail Euglandina (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Murray and Johnson1984; Gerlach, Reference Gerlach2016). Two members of this species complex were introduced under the single species name Euglandina rosea (Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Yeung, Slapcinsky and Hayes2017) in a failed attempt to control populations of an invasive agricultural pest species, the giant African snail Lissachatina fulica (Gerlach et al., Reference Gerlach, Barker, Bick, Bouchet, Brodie and Christensen2021). Subsequently, a second invasive mollusc predator was identified, the New Guinea flatworm Platydemus manokwari. This has now become the primary predator of tree snails on the islands, with Euglandina declining on all Society Islands (Gerlach et al., Reference Gerlach, Barker, Bick, Bouchet, Brodie and Christensen2021).

Captive populations of nine species of Partula were established for genetics research in the 1960s and added to up until 1984. With the extinction of wild populations these became the basis of a conservation breeding programme (Clarke & Wells, Reference Clarke, Wells, Gittenberger and Gould1992), first at the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust and later as the Partulid Global Species Management Programme coordinated by the Zoological Society of London. Additional species were brought into the breeding programme during 1991–1995 as Euglandina spread through the islands. All snails were kept in stable, artificial conditions according to the European Association of Zoos and Aquariums (EAZA) Best Practice Guidelines covering all aspects of care (Clarke, Reference Clarke2019). Not all species were successfully bred but 12 species, with four subspecies, were considered to be established ex situ by 2015 (Coote et al., Reference Coote, Merz and Pearce-Kelly2015).

Efforts to re-establish Extinct in the Wild species have had mixed results, although successful reintroduction has been documented for 10 animals and three plants (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Abeli, Beckman Bruns, Dalrymple, Foster and Gilbert2023). The animals have all been vertebrates: the Yarkon bream Acanthobrama telavivensis, Tequila splitfin Zoogoneticus tequila, Española giant tortoise Chelonoidis hoodensis, Californian condor Gymnogyps californianus, Guam rail Hypotaenidia owstoni, black-footed ferret Mustela nigripes, European bison Bison bonasus, red wolf Canis rufus, Arabian oryx Oryx leucoryx and Przewalski’s horse Equus ferus. In the case of Partula, reintroduction attempts first began in 1995 on Moorea Island. At this time fully wild re-establishment was considered impossible because of the persistence of Euglandina but it was thought that release into a predator-proof field exclosure may be viable and captive-bred Partula suturalis, Partula taeniata and Partula tohiveana were released into a protected Partula reserve (Coote et al., Reference Coote, Clarke, Hickman and Murray2004). Although all three species adapted to the exclosure and bred, the releases ultimately failed because of repeated incursion by Euglandina as a result of insurmountable maintenance problems (Coote et al., Reference Coote, Clarke, Hickman and Murray2004).

Field surveys across the Society Islands and reintroduction efforts for 10 species, led by the Partulid Global Species Management Programme’s field conservationist Trevor Coote, resumed in 2015 (Coote et al., Reference Coote, Merz and Pearce-Kelly2015). During the construction of an exclosure on Tahiti Island, relict populations of Partula clara were found in Tahitian chestnut Inocarpus fragifer woodland. Tahitian chestnuts are also commonly known as mape trees, and this discovery led to the so-called mape hypothesis suggesting that these tall trees formed refugia for Partula as their bare, dry trunks deter foraging Euglandina. Reintroductions onto such trees were suggested as an alternative to the ineffective and high-maintenance exclosures. Releases of captive-bred snails onto trees became the focus for reintroductions from 2015 onwards (Gerlach, Reference Gerlach2016), continuing every year apart from 2020–2022, when the Covid-19 pandemic caused a hiatus to the programme and movement restrictions prevented fieldwork on all islands (Table 1).

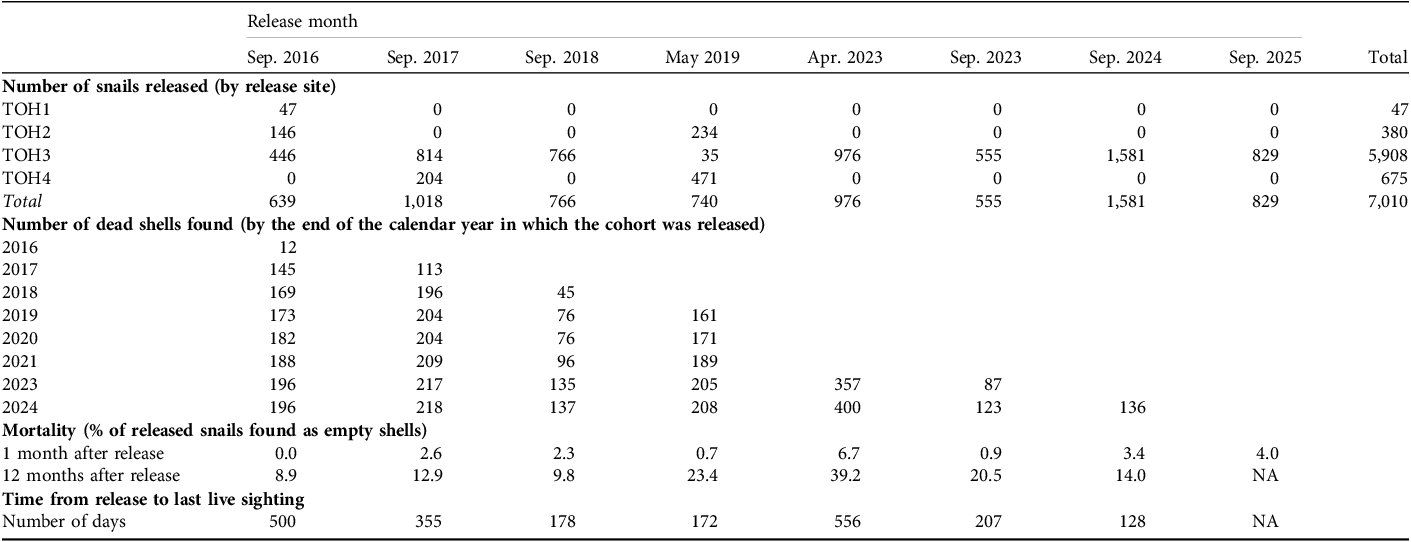

Table 1 Summary of releases of captive-bred Partula tohiveana tree snails in the Afareaito valley on Moorea Island, French Polynesia (Fig. 1) during 2016–2025, and population monitoring results to the end of 2024.

These unprotected releases have proved simple to implement but difficult to evaluate. In many cases survival (as indicated by low numbers of dead shells and initial counts of living snails) has been good but released populations have mostly disappeared after a few months. However, in 2024 a population of wild-born Partula tohiveana was found on Moorea Island, demonstrating that a population of this species has been re-established. Here we evaluate the establishment process.

Partula tohiveana, the Tohiea tree snail, is a relatively large sinistral partulid with a maximum shell length of 13.7 mm (Gerlach, Reference Gerlach2016). It was naturally range-restricted, originally found in upper parts of the valleys of Moorea’s eastern ridge, particularly in association with the ‘ie‘ie or climbing pandanus Freycinetia demissa, up to 4 m above the ground (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Johnson and Clarke1982; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Murray and Clarke1993). Despite its specialist ecology, and having passed through a bottleneck of just four captive individuals (Gerlach, Reference Gerlach2016), P. tohiveana now breeds well in captivity and has been used as a starter species for new conservation breeding collections. It is ovoviviparous, producing 16 young per year and reaching maturity at 6–12 months of age (Gerlach, Reference Gerlach2016; Clarke, Reference Clarke2019). Despite the population bottleneck there is still some phenotypic variation, with at least two of the original four polymorphisms remaining (banded and unbanded).

Methods

The general protocols for transport, release and monitoring of Partula snails are described below. Where any aspects are specific to Partula tohiveana, this is specified.

Release methods

Prior to release we screened all shipments of snails from captive-bred populations for potential pathogens (Clarke, Reference Clarke2019; Flach et al., Reference Flach, Stidworthy, Aberdeen, Clarke, Davidson and Donald2024), to maximize survival of released animals and to prevent importation of novel pathogens into French Polynesia. We transported snails in a dormant, aestivating state according to a fixed protocol (Clarke, Reference Clarke2019) and revived nearly all of them from aestivation on Tahiti (< 1% mortality).

Initially, we released Partula species into the valleys where the captive stock had originally been collected. In the case of P. tohiveana this was the Afareaito valley on Moorea Island (Fig. 1). This species is known to associate with F. demissa (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Johnson and Clarke1982; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Murray and Clarke1993) and we selected trees supporting this plant at three release points (TOH1–TOH3), with a fourth added subsequently (TOH4). The first site, TOH1, was lost to a tree-fall shortly after release and no monitoring data are available. TOH2 has F. demissa growing up I. fragifer trees (Plate 1a), is the most easterly of the sites and is relatively dry, but has not been used since 2019. TOH3 was the main release site in most years; it is the location of the 1995 Partula reserve (but the barriers intended to keep out predators have not been intact for the last 2 decades) and has dense growth of F. demissa, both on the ground and on trees (Plate 1b). TOH4 comprises large trees with dense F. demissa on steep ground but the steep slope makes monitoring impractical and it has only been used on two occasions.

Fig. 1 (a) Location of the release area (black rectangle) of captive-bred Partula tohiveana in the Afareaito valley on Moorea Island, and habitat categories (modified from Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Pouteau, Spotswood, Taputuarai and Fourdrigniez2015): invaded habitat is dominated by introduced (non-native) plants, native habitat is mostly native plant species, and mixed habitat is intermediate. (b) Location of Moorea Island in the Society Islands, French Polynesia.

Plate 1 Sites of releases of Partula tohiveana in the Afareaito valley on Moorea Island, French Polynesia: (a) site TOH2, used in 2016 only, (b) site TOH3, the main release site used each year during 2016–2024. Arrows show release points on Tahitian chestnut Inocarpus fragifer trees amongst climbing pandanus Freycinetia demissa.

Prior to release we placed up to 100 snails of each species in plastic plant pots, one-third filled with soaked sphagnum moss and covered in clingfilm for transport. In 2025 the practice of using sphagnum moss was changed in favour of using soaked tissue paper to encourage the snails to disperse more quickly. At the release sites we attached one or more such pots to trees in each site by garden wire; the number of trees used varied between release sites. Pots were attached to the main trunk or substantial branches 1.5–2.0 m above ground. On release we removed the clingfilm and sprayed the pots with filtered water to encourage snail activity and dispersal. Pots were left in place to allow gradual dispersal and to provide a site marker for monitoring purposes. All release sites were georeferenced to ensure that they could easily be relocated.

We marked snails with enamel paint before release, using a different colour each year so that release cohorts could be recognized. Adults, identifiable by the presence of an expanded lip at the shell aperture, were marked on the middle of the shell, and young snails lacking any apertural lip were marked on the apex to distinguish life stages and determine whether juveniles were maturing in the wild. In 2023 we replaced the enamel paint with ultra-violet reflective paint (Starglow UV neon, Glowtec Ltd., UK) so that marked snails could be detected with an ultra-violet torch at heights of up to c. 5 m above ground (Gerlach et al., Reference Gerlach, Pearce-Kelly, Brocherieux, Elliott and Garcia2023). In some species, problems arose with paint adhesion, either because of a dehiscent periostracum or a highly glossy shell surface. Partula tohiveana has a thin periostracum and a rough surface, and we did not experience any paint adhesion issues with this species.

Monitoring

We monitored snails 24 hours after release and then frequently thereafter. Timing of monitoring was dependent on the availability of personnel and weather conditions. In 2015–2019 we monitored releases monthly until bad weather prevented surveys for ≥ 3 months. We restructured the release programme following the pandemic and changed our approach from 2023 onwards. We reduced the number of release sites, which enabled monitoring to be more focussed, and we carried out more regular monitoring of all sites with assistance from the French Polynesian government’s Direction de l’environnement and the Fare Natura eco-museum on Moorea Island. Monitoring is now carried out on a schedule of 24 hours post release, weekly for the first month, fortnightly for the following month and monthly thereafter.

During monitoring we searched the ground around release trees for Partula shells, recording them as adult or juvenile and noting the colour mark (if present). We removed all dead shells to prevent future double counting. We examined all release trees and nearby vegetation for the presence of snails, which were recorded in the same manner. These visual searches were limited to what could be seen from the ground; snails were occasionally recorded up to 5 m above ground (especially once ultra-violet marked), but search effectiveness was inevitably reduced above c. 3 m. We used three approaches in our efforts to detect snails in the forest canopy. In 2017 we attached a camera (GoPro HERO 6, GoPro, USA) to a 3 m long pole, which allowed us to detect some snails but the images were too poor to provide useful detail. In 2023 we used a drone (DJI Mavic Mini, DJI, China) to search for snails, both in natural light and with an ultra-violet torch attached. Whilst this did provide access to high levels of the canopy, we found navigation in complex forest to be problematic and it proved impossible to fly the drone close enough to vegetation to obtain useable images. Finally, we used a remote-controlled camera (Olympus Tough TG-6, Olympus Corporation, Japan) attached to a remotely controllable tripod head (ZIFON YT-800, Zhongshan City Zifon Electronic Technology Co. Ltd., China) on a 9 m telescopic monopod to directly access the canopy. This gave high quality imagery but we were unable to locate significant numbers of snails. Therefore, ongoing monitoring relies on visual searches aided by the use of ultra-violet reflective paint to mark snails. We also recorded the presence of predators, although we did not search for them systematically.

In evaluating re-establishment success, we considered mortality, survival, maturation, reproduction and recruitment. We also considered emigration but data were limited; only one shell was found > 5 m from a release point and all live snails were located within a similar radius. Mortality rates (percentage of released snails found dead) were calculated from the numbers of dead shells. Survival was indicated by the numbers of live snails recorded and the maximum number of days after release on which live animals were found. Maturation was demonstrated by finding animals (live or dead) that had been released as juveniles (with an apical paint mark) but had grown to full maturity, defined as having developed an expanded shell lip. Reproduction was indicated by the presence of unmarked individuals and recruitment was confirmed by finding unmarked adults. Unmarked (wild-born) snails could be individually identified from photographs based on the position of colour bands, growth lines and irregularities on the shell surface.

If several live, unmarked adults were found simultaneously, we considered this as evidence of population establishment. Any such population was then a particular focus of monitoring, to determine whether the number of individuals was increasing and the area occupied expanding, or whether the population was stable or contracting.

Results

Mortality, survival and dispersal

We summarize the numbers of live and dead snails in Table 1. We recorded low mortality in the first month after release (0–7% of released snails found dead). In contrast, mortality after 1 year was higher (9–39%) but varied widely between years. This variability probably reflects differences in monitoring opportunities and methods during 2016–2019; higher monitoring frequency since 2023 has resulted in more shells being recovered. The majority of snails disappeared quickly but survival to at least 1 year was recorded in 2016 and 2023 (Table 1). We observed direct evidence of dispersal from the release site in 2024 when one live, marked juvenile was found 5 m from the nearest release pot after 3 days.

Maturation and reproduction

We found adults that had been released as young in 2016 (1), 2018 (5), 2019 (1) and 2023 (10). Records of unmarked snails (shells and/or live animals) provide evidence of reproduction. We found the first wild-born snail on 29 September 2016 (a newborn) and the first half-grown juvenile on 9 August 2017, resulting from the first release the year before. We found the first wild-born adult on 24 September 2018 (Plate 2). We have found wild-born individuals in increasing numbers since early 2023 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Numbers of individual wild-born Partula tohiveana found as dead shells and live individuals during 2016–2024. Breaks indicate periods without monitoring.

Plate 2 Live wild-born Partula tohiveana observed early in the reintroduction programme providing first evidence of re-establishment: (a) first large young snail, 9 August 2017, (b) first live adult, 24 September 2018, (c) large young, 13 October 2017, (d) second live adult, 14 October 2018, (e) snail shown in (d) found again on 8 November 2018, (f) third live adult, 16 August 2019. Scale bar 1 cm. Photos: T. Coote.

Recruitment

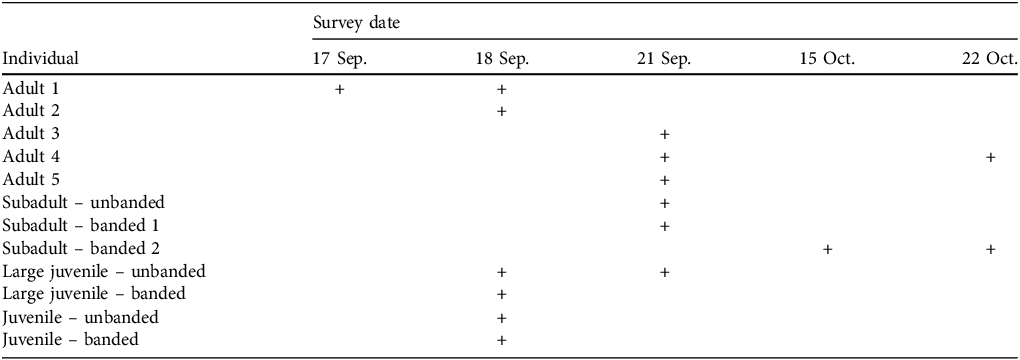

We have found adult, unmarked shells at site TOH3 regularly since 2020, indicating successful recruitment (Plate 2), with a marked increase in unmarked shells from 2023 onwards. We found single live, unmarked adults of P. tohiveana on two occasions in 2018; during surveys over 3 days in September 2024 we located a population of unmarked individuals, comprising four adults and 13 juveniles (Table 2, Plate 3); and we found further unmarked individuals in October 2024 and September 2025. The latter included an individual 10 m outside of the release site.

Table 2 Records of individual unmarked P. tohiveana found at release site TOH3 in the Afareaito valley on Moorea Island, French Polynesia, in 2024. Dates on which each individual was observed are recorded (+). Please refer to Plate 3 for images of adults 1–4.

Plate 3 Four live, wild-born adult P. tohiveana individuals found in September 2024: (a) Adult 1: mature adult, 17 September 2024, (b) Adult 2: young adult with partially developed shell lip, 18 September 2024, (c) Adult 3: mature adult, 21 September 2024, (d) Adult 4: young adult, 21 September 2024. Scale bar 1 cm. Photos: J. Gerlach.

Discussion

The data on the releases of P. tohiveana in the Afareaito valley on Moorea Island show that the released animals adapted well to the natural environment despite having spent c. 20 generations in relatively stable, artificial conditions. Breeding occurred in the first year and recruitment was demonstrated from 2018 onwards, 2 years after the first release. Only single wild-born adults were found initially, but in September 2024 a resident, unmarked population comprising adults and juveniles was detected at the release site. This discovery of a population of wild-born P. tohiveana demonstrates that captive-bred Partula can be re-established in the wild. However, the presence of multiple wild-born adults does not necessarily constitute a viable population in the long term, and we recognize this is merely the first step towards full recovery. The first evidence of expansion was found in Sepember 2025 and continued expansion will be needed to confirm long-term establishment; this is now the focus of monitoring for this species. In time, monitoring data will reveal whether the population is continuing to expand in numbers and area, is remaining stable or declining. The 2025 releases took place in similar habitat 20 m from this population, to evaluate whether the population will continue to grow in the absence of further augmentation. Partula conservation has always been adaptable and reactive, and future management will continue to be adjusted based on monitoring results.

In this particular case, it is notable that population establishment has occurred despite the presence of the invasive predators that caused the original extirpation of partulid populations. The mape hypothesis proposed that it may be possible to re-establish partulids on tall trees where there could be vertical separation between predators on or near the ground and partulids high in the trees (Coote et al., Reference Coote, Merz and Pearce-Kelly2015). The height was not specified but given that Euglandina often climb, it was hoped that released Partula could be established some 4 m above the ground: high enough to reduce predation but still be visible for monitoring purposes. Partula tohiveana is associated with F. demissa, which grows as a climber on forest trees to well above this height and also occurs sprawling on the ground. The re-established population has so far been found almost exclusively in the low vegetation, with all but one individual being < 1 m above ground level. This would be expected to make them vulnerable to predation, and P. manokwari flatworms are occasionally found in the act of predating the snails. Euglandina are also present in the area, although now only found as isolated individuals. Euglandina has declined throughout the Society Islands, to the point of extinction on some of the islands (Gerlach et al., Reference Gerlach, Barker, Bick, Bouchet, Brodie and Christensen2021). It has exhibited the boom-and-bust dynamics typical of some invasive species, but the reason for this is not known. It no longer appears to be a major risk to Partula populations, even where it remains present. Population establishment in the presence of predators may have been possible because of the complexity of the vegetation. Although flatworms have been found in the low growing vegetation, the ground has only sparse leaf litter and the vegetation structure is extremely complex. This provides many alternative routes for a predator to explore, reducing the likelihood of a successful pursuit of a snail.

At present there is no evidence of population re-establishment on the taller forest trees, with no recent sightings of released or wild-born snails away from the TOH3 release point. However, monitoring snails on these trees has proven difficult. The ultra-violet reflective paint increases detection distance but it is still difficult to see snails > 5 m above ground. The complexity of the habitat made it impossible to fly a drone close enough to the leaves on the trees to enable clear visualization and sufficiently thorough surveying. The use of cameras on long poles helped to extend the monitoring range and the GoPro did detect snails at c. 4–5 m above ground but both cameras proved too unstable to collect clear images or carry out extensive surveying. The remotely controlled camera improved imagery but we did not detect any significant populations above 5 m. In the case of P. tohiveana the lack of sightings high up in trees may be a reflection of their ecology as historical records show them to have inhabited relatively low-growing vegetation (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Johnson and Clarke1982).

The scarcity of observations of live snails outside dense growth of F. demissa may be a result of rapid and wide early dispersal. This pattern of movement seems to be typical for reintroduced or translocated snails: released Hawaiian tree snails Achatinella concavospira initially dispersed 2.5–7.0 m (maximum of 14.1 m) from the release point but within 2–4 months established stable home ranges (Hee, Reference Hee2024). Early, rapid dispersal was initially seen as positive and a requirement for survival in the presence of predators (Coote et al., Reference Coote, Merz and Pearce-Kelly2015). However, it may result in over-dispersed populations, reducing the potential for breeding and population establishment, and contributing to the lack of evidence of success in small-scale releases of several Partula species. Mass releases may overcome this to enable establishment of P. tohiveana and P. taeniata, the two species released in the largest numbers on Moorea. The latter is one of the most adaptable partulids and one of the few species to persist in the wild (categorized as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List; Coote & Gerlach, Reference Coote and Gerlach2022). Releases of P. taeniata have been successful in re-establishing additional populations since 2019.

Thanks to decades of effort from the international zoo community it is possible to breed tree snails in large numbers and relatively easy to transport them to field sites. The greatest difficulty in the reintroductions is the monitoring of small animals in complex habitats, which requires considerable effort and dedication. Monthly monitoring of the snail populations within a narrow radius of the release sites is practical for a large part of the year, although monitoring is inevitably disrupted by extreme weather conditions. Monitoring population expansion will be challenging and will require an exploratory approach, probably as an intensive annual survey. The re-establishment of populations of the Critically Endangered P. taeniata is an important observation because it demonstrates that the release of captive-bred snails can be effective. The discovery of a population of wild-born P. tohiveana is significant for the Partula conservation programme as it showed for the first time that an Extinct in the Wild snail can be re-established; P. tohiveana was reassessed as Critically Endangered in 2025 (Gerlach & Pearce-Kelly, Reference Gerlach and Pearce-Kelly2025). It is also notable that the extinction of this species in the wild occurred > 40 years ago (Reference Clarke, Murray and Johnson1984). The captive lineage last received input from the wild in 1984 and passed through a genetic bottleneck of four individuals in 1988 (Gerlach, Reference Gerlach2016). Although this bottleneck probably resulted in inbreeding and the snails spent multiple generations in relatively constant, artificial conditions, they have retained sufficient adaptability to survive and breed in the wild. We are hopeful that the remaining Extinct in the Wild Partula and other species can also be re-established.

Author contributions

Data collection: JG, TA, CB, MD, KH, EL, SM, AO, PPK, AR, RT; programme management: SA, DC, KG, PPK; conservation breeding: SA, DC, JE, DF, SH, PPK; writing: JG; revision: all authors.

Acknowledgements

The re-establishment of Partula tohiveana would not have been possible without the late Trevor Coote’s 20 years of dedicated work; Bryan Clarke, James Murray and Michael Johnson were the original catalysts for the conservation programme and their captive populations, especially under the care of Vivien Frame, saved P. tohiveana from extinction. The ex situ conservation breeding and reintroduction programme relies on the hard work and financial support from the international zoo community (Akron, Artis, Bristol, Chester, Detroit, Duesseldorf, Disney’s Animal Kingdom, Edinburgh, Jersey, London, Marwell Wildlife, Poznan, Riga, Saint Louis, Schwerin, Sedgwick County, Whipsnade, Wild Discovery, Woodland Park and Wuppertal zoos), Conservation International, Critical Ecosystems Partnership, Foundation Serge, The Mohammed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund and Beauval Nature. The 1wild Foundation supported the development of new monitoring approaches. The IUCN Species Survival Commission Conservation Planning Specialist Group facilitated the development of the Partula conservation breeding and reintroduction programme.

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

Handling and transport of animals in the Partula conservation programme is covered by agreement between the Direction de l’environnement, French Polynesia and the Partulid Global Species Management Programme. This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.