Benzodiazepines act as positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors Reference Sigel and Ernst1 and have sedative, hypnotic, muscle relaxant and anticonvulsant effects, with an exceptionally low risk of overdose. Reference Riemann and Perlis2 Benzodiazepines have an addictive potential as they stimulate dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area by modulating GABAA receptors in adjacent interneurons. Reference Tan, Brown, Labouèbe, Yvon, Creton and Fritschy3 Evidence suggests that benzodiazepines with shorter half-lives are associated with a greater risk of dependence. Reference Soyka4 Long-term (beyond 6 months) users may experience withdrawal symptoms, such as anxiety, insomnia, muscle spasms, perceptual hypersensitivity and even psychosis. Reference Lader5 Burnout, an emotional and psychological stressor, is frequently experienced by physicians, with an overall prevalence of up to 80.5%. Reference Rotenstein, Torre, Ramos, Rosales, Guille and Sen6 High occupational stress could lead to sleep disorders, Reference Tsai and Liu7 anxiety and depression. Reference de Jong, Nieuwenhuijsen and Sluiter8 Physicians have a similar prevalence of substance misuse compared to the general population; however, prescription drug abuse is more prevalent owing to accessibility and prescription privileges. Reference Watkins9 Self-prescription is common. A recent study estimated that the self-prescription rates of opioids, benzodiazepines and psychotropic medications were between 3 and 7%. Reference Hartnett, Drakeford, Dunne, McLoughlin and Kennedy10 Self-medication for emotional stress and mood disturbances carries the risk of addictive drug use and leaving comorbidities untreated. Reference DuPont and Gold11 Substance misuse among physicians is an important public health issue related to physicians’ well-being and patient safety.

Previous studies on resident physicians revealed that the reasons for benzodiazepine misuse were self-treatment for insomnia and to cope with stress. Reference Khan, Din, Khan, Khan, Hanif and Nawaz12 A previous study in Taiwan revealed that physicians had a lower risk of depression, yet higher odds of insomnia and anxiety, compared with the general population. Reference Huang, Weng, Wang, Hsu and Wu13 Some specialities were associated with a high risk of substance use disorders, such as emergency room doctors and anaesthesiologists. Reference Rose, Campbell and Skipper14,Reference Samuelson and Bryson15 However, no previous study examined the nationwide prevalence and distribution of benzodiazepine use among physicians in Taiwan. To evaluate the patterns and correlates of benzodiazepine use in physicians, we compared the characteristics of heavy users with those of low-dose users via the physician registries of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), from 2014 to 2020.

Method

Data source

In Taiwan, the Universal National Health Insurance Programme was launched in 1995, and approximately 99% of the national population was enrolled. Reference Lin, Warren-Gash, Smeeth and Chen16 We utilised a data-set for the nationwide population from 2000 to 2018. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. All procedures involving human patients were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of China Medical University & Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan (approval numbers CMUH109-REC2-031(AR-5) and CMUH112-REC1-117(CR-1)). Because of the anonymous nature of the NHIRD data, informed consent could not be obtained from the participants.

Study population

We identified 32 080 physicians after we combined physician’s identities on 1 January 2009 with the NHIRD data. Furthermore, the study period was from 2014 to 2020. Participants younger than 20 years old were excluded. The benzodiazepine group included physicians who had been prescribed benzodiazepines (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical codes: N05CD, N05CF, N05BA and N03AE01), either themselves or by other physicians, during the follow-up period. Benzodiazepine users were further divided into low, intermediate and heavy doses based on the yearly equivalent doses of <20, 20–150 and >150 defined daily dose (DDD), respectively, according to Isacson’s definition. Reference Isacson17 The equivalent dose was calculated after the DDD of benzodiazepine per year was summed for each user.

Measurement

We investigated the characteristics of each group, which included gender, age and psychiatric comorbidities: sleep disorders (ICD-9-CM codes 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 309, 311; ICD-10-CM codes F32, F33, F34.1, F43), anxiety (ICD-9-CM codes 300, 309.21, 309.24; ICD-10-CM codes F40, F93.0, F43.22) and depressive disorders (ICD-9-CM codes 307.41, 307.42, 780.50, 780.51, 780.52; ICD-10-CM codes F51.0, F47.8, F47.9, G47). Physicians’ medical speciality was identified based on Taiwan’s Diplomate Specialization and Examination Regulations. 18 The analysis was not pre-registered and the results should be considered exploratory.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the number and percentage for the categorical variables, and mean and standard deviation for age. Kruskal–Wallis and chi-squared tests were used to examine the differences between the three benzodiazepine user groups. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to examine the association of demographic characteristics and specialities with benzodiazepine use (reference was the control group), as well as heavy benzodiazepine use (reference was the low-dose group). A generalised estimating equation was used to examine the relationship between the three psychiatric comorbidities and benzodiazepine doses in the four ordinal groups (no use and low-, intermediate-, and high-dose users). Age and gender were controlled for in the models as time-invariant variables and other comorbidities as time-variant variables. All analyses were conducted via SAS version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA; see https://www.sas.com/en_gb/home.html). Significance level was set as P-value <0.05.

Results

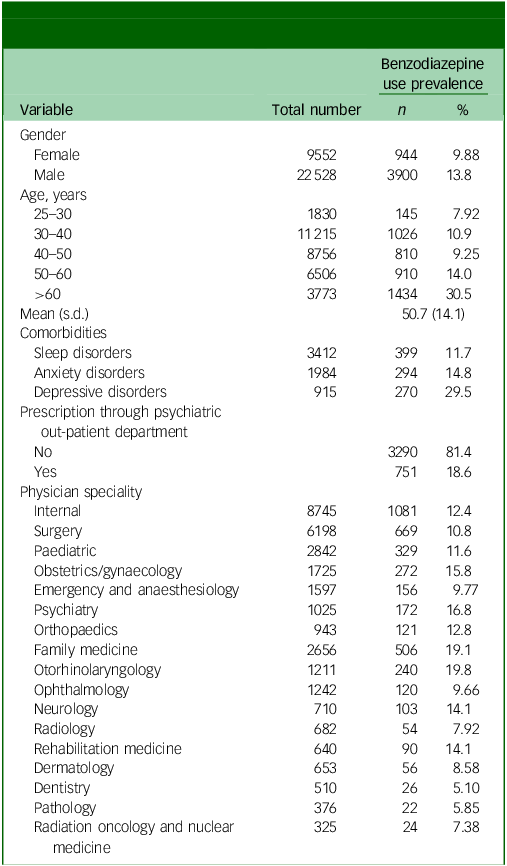

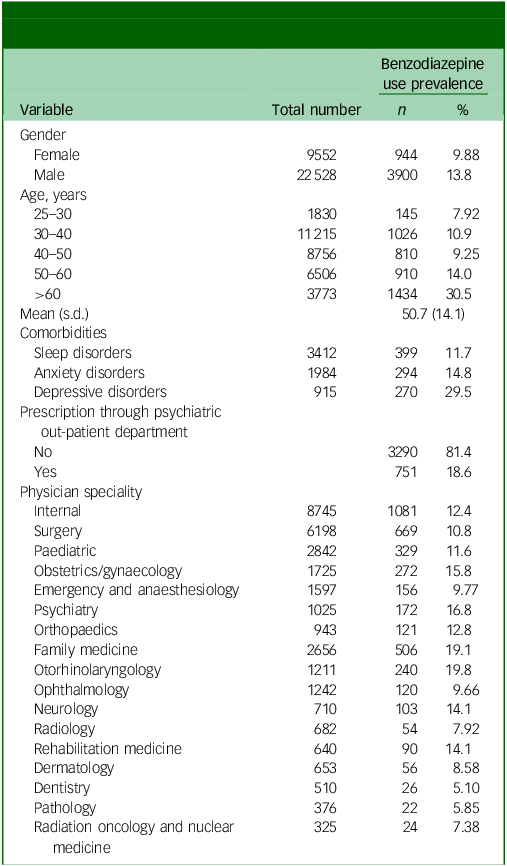

Table 1 presents the prevalence of benzodiazepine use among the 32 080 physicians. The overall prevalence of benzodiazepine use was 15.1%, and 9.88% and 13.8% of female and male physicians were benzodiazepine users, respectively. Among the different age groups, physicians older than 60 years had a higher percentage of benzodiazepine use (30.5%). Among the participants, 11.7%, 14.8% and 29.5% had sleep disorders, anxiety, and depressive disorders, respectively. Among the 4844 benzodiazepine users, 18.6% had prescriptions from psychiatric out-patient departments. Regarding specialities, highest prevalence of benzodiazepine users was in otorhinolaryngology (19.8%), followed by family medicine (19.1%) and psychiatry (16.8%).

Table 1 Demographics and comorbidities in physicians with and without benzodiazepine use during 2014–2020 (N = 32 080)

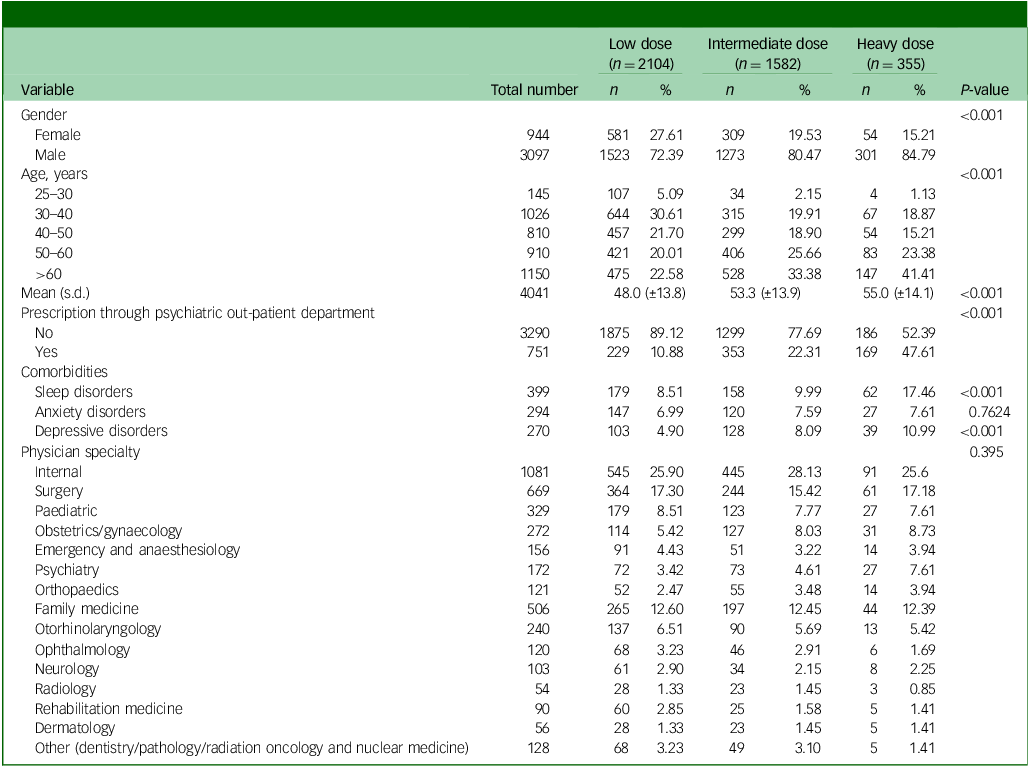

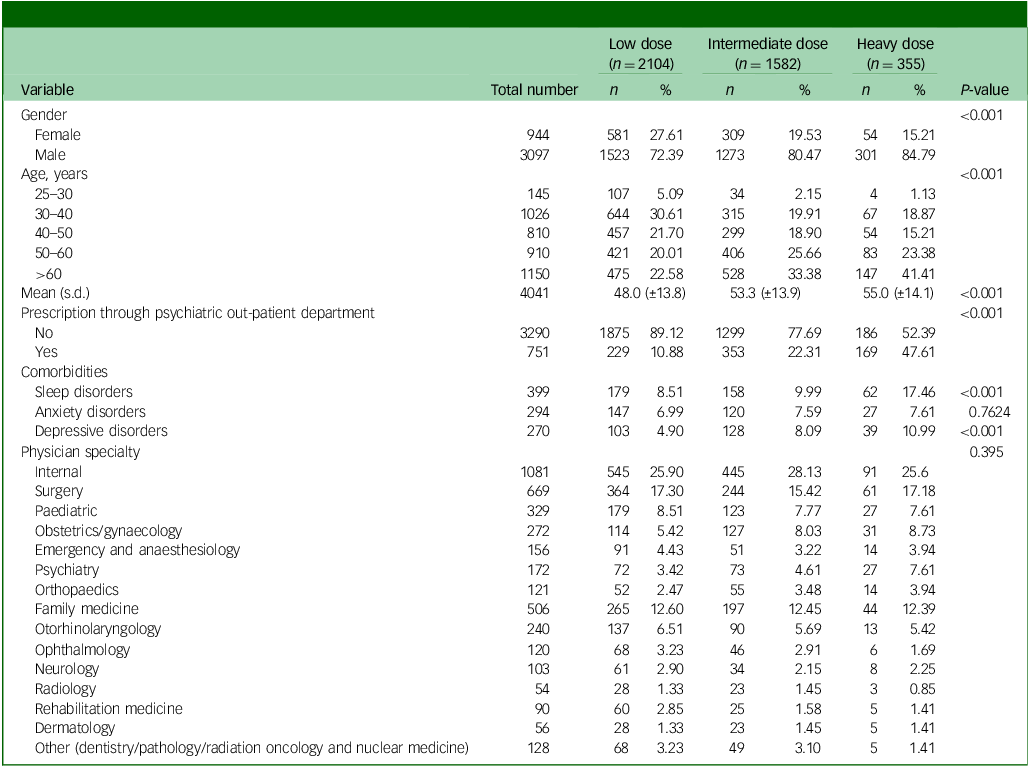

We further stratified benzodiazepine users into low, intermediate and heavy users. In 2020, 52%, 39% and 9% were low, intermediate and heavy users, respectively. In all three groups, heavy users were older (Table 2, P < 0.001, which was less than the significance level after Bonferroni’s correction, 0.05/7 = 0.007). A higher percentage of heavy users were prescribed benzodiazepines by the psychiatric out-patient department compared with the other two groups (P < 0.001, which was less than 0.007). Sleep disorders were the most common comorbidity. There were no significant differences among specialities across different dosage levels.

Table 2 Demographics and comorbidities in physicians with benzodiazepine use in 2020

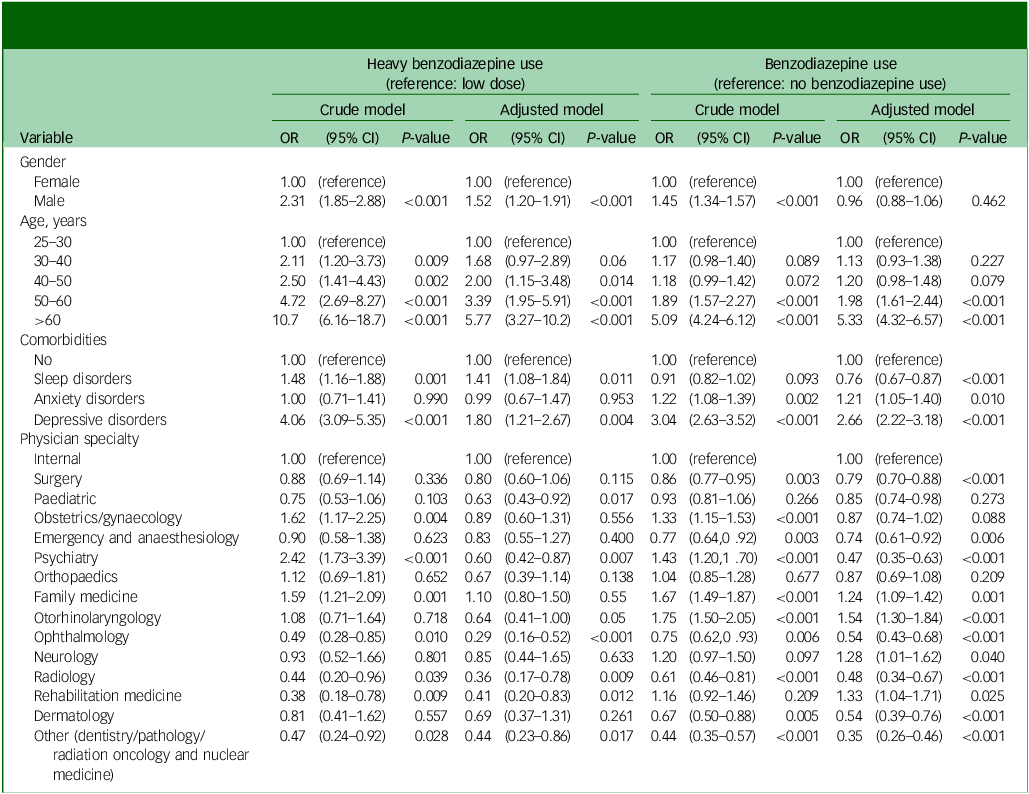

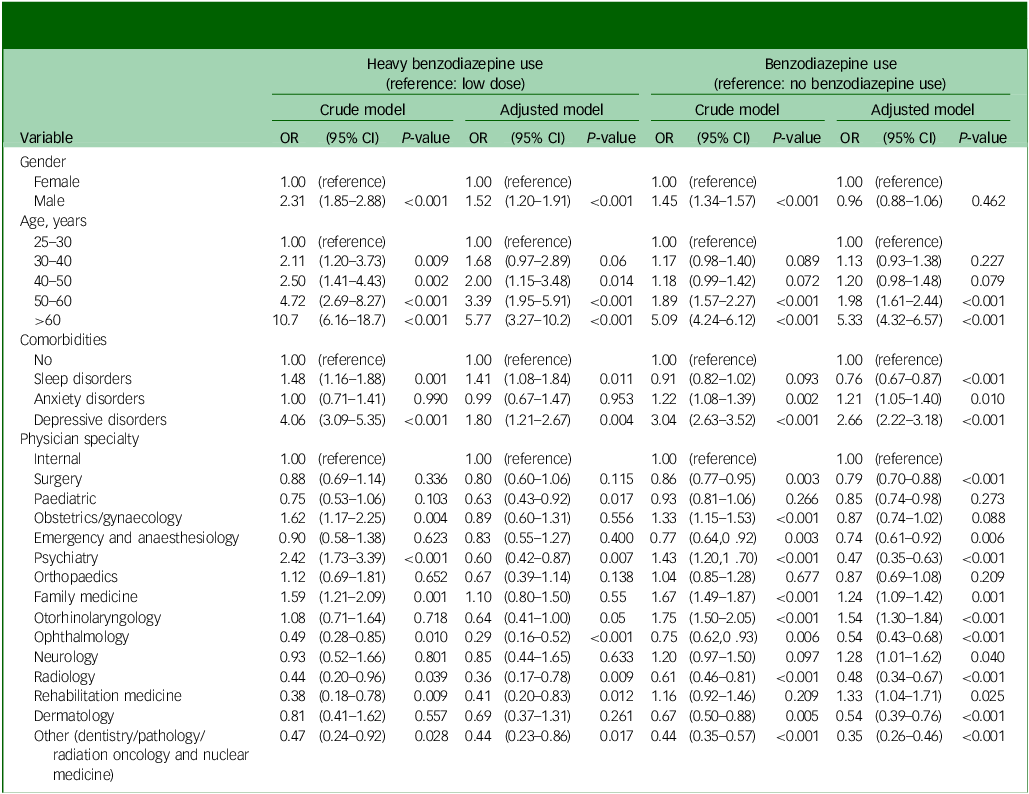

According to Table 3, older physicians were more likely to use benzodiazepines (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 5.33; 95% CI 4.32–6.57 for age >60 years) and male physicians more likely to become heavy users (aOR = 1.52; 95% CI 1.20–1.91). Physicians with anxiety (aOR = 1.21; 95% CI 1.05–1.40) and depressive disorders (aOR = 2.66; 95% CI 2.22–3.18) had higher odds of becoming benzodiazepine users. Among benzodiazepine users, sleep disorders were associated with heavy use compared with low-dose use (aOR = 1.41; 95% CI 1.08–1.84). Compared with internal medicine physicians, family medicine (aOR = 1.24; 95% CI 1.09–1.42), otorhinolaryngology (aOR = 1.54; 95% CI 1.30–1.84), neurology (aOR = 1.28; 95% CI 1.01–1.62) and rehabilitation physicians (aOR = 1.33; 95% CI 1.04–1.71) were more likely to use benzodiazepines. Conversely, physicians in surgery (aOR = 0.79; 95% CI 0.70–0.88), emergency and anaesthesiology (aOR = 0.74; 95% CI 0.61–0.92), psychiatry (aOR = 0.47; 95% CI 0.35–0.63), ophthalmology (aOR = 0.54; 95% CI 0.43–0.68), diagnostic radiology (aOR = 0.48; 95% CI 0.34–0.67) and other departments (aOR = 0.35; 95% CI 0.26–0.46) were less likely to use benzodiazepines. Paediatric (aOR = 0.63; 95% CI 0.43–0.92), psychiatry (aOR = 0.60; 95% CI 0.42–0.87), ophthalmology (aOR = 0.29; 95% CI 0.16–0.52), diagnostic radiology physicians (aOR = 0.36; 95% CI 0.17–0.78), rehabilitation physicians (aOR = 0.41; 95% CI 0.20–0.83) and other departments (aOR = 0.44; 95% CI 0.23–0.86) had a lower chance of becoming heavy users compared with internal medicine physicians.

Table 3 Estimates of longitudinal patterns of low-dose and frequent use of benzodiazepines in physicians according to the generalised estimating equations

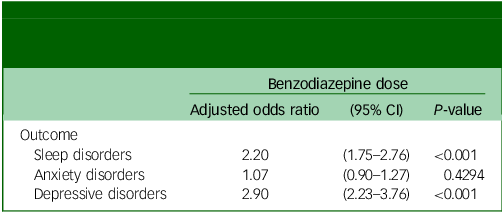

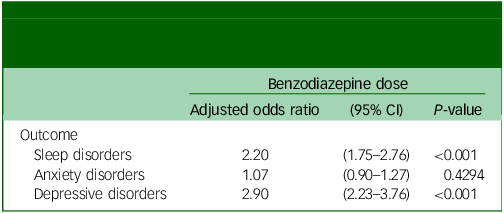

Table 4 presents the results of the generalised estimating equation analysis for benzodiazepine doses in the four ordinal groups, adjusted for gender and age. All three psychiatric comorbidities were associated with increased benzodiazepine use. For sleep and depressive disorders, the odds of being higher-dosage users compared to lower-dosage users were 2.20 (95% CI 1.75–2.76) and 2.90 (95% CI 2.23–3.76), respectively.

Table 4 Estimates of patterns of dose of benzodiazepines in physicians in the four ordinal groups (non-users, low-, intermediate- and high-dose users) via the generalised estimating equations

Models are adjusted for gender and age; reference is lower-level users. All three psychiatric disease outcomes are analysed in separate models.

Discussion

Summary

Our findings indicated that older male physicians with comorbidities, such as depression or sleep disorders, were at higher probability of being benzodiazepine users. Speciality in otorhinolaryngology or family medicine was associated with greater benzodiazepine use.

Comparison with existing literature

The prevalence of benzodiazepine use was 7.5% in the general French population. Reference Lagnaoui, Depont, Fourrier, Abouelfath, Begaud and Verdoux19 The level of consumption ranged from 39 to 55% among senior citizens, and continuous use ranged from 17 to 30%. Reference Jobert, Laforgue, Grall-Bronnec, Rousselet, Péré and Jolliet20 In Taiwan, one in five community-dwelling older adults reported sedative-hypnotic drug use. Furthermore, approximately 5% of usage was without a doctor’s prescription. Reference Tseng, Yu, Lee, Huang, Huang and Wu21 The prevalence of past-year non-medical use was 0.71% and 3.66% for sedatives/hypnotics and analgesics or sedatives/hypnotics, respectively, in the 2014 national survey with 17 837 individuals aged 12–64 years. Reference Chen, Chen, Tsay, Wu, Chen and Hsiao22 Our analysis revealed that the prevalence of benzodiazepine use among physicians was 15.1%, which was lower than 19.6–20.3% in the general population aged >25 years during 2014–2018 in Taiwan (unpublished data). The lower prevalence could be because physicians were aware of the risks, in better health or concerned regarding the stigma. The higher prevalence of benzodiazepine use compared with other countries was probably attributable to the National Health Insurance reimbursement system.

Benzodiazepines are commonly prescribed as effective medications to treat insomnia and anxiety disorders in later life. Reference Gupta, Bhattacharya, Farheen, Funaro, Balasubramaniam and Young23,Reference Samara, Huhn, Chiocchia, Schneider-Thoma, Wiegand and Salanti24 Our study showed that older physicians were more likely to use benzodiazepines and become heavy users, which corresponded to the relationship between advanced age, insomnia and anxiety disorders. The observation that male physicians were more likely to heavily use benzodiazepines echoed results from a previous study, which revealed that female nurses were less likely to be heavy benzodiazepine users than male nurses in Taiwan. Reference Sang, Liao, Miao, Chou and Chung25 Male gender was also associated with use of sleep aids in early-career emergency physicians in Japan. Reference Chiba, Hagiwara, Hifumi, Kuroda, Ikeda and Khoujah26 Unlike in East Asia, where stigma and professional norms discourage formal mental healthcare, Western settings may display greater openness toward mental health treatment and different gender norms. A study in Canada revealed that male physicians were significantly less likely to fill a benzodiazepine prescription than female physicians. Reference Myran, Milani, Pugliese, Hensel, Sood and Kendall27 Female physicians tended to perceive higher stress. Reference Kannampallil, Goss, Evanoff, Strickland, McAlister and Duncan28 Nevertheless, women had a lower rate of benzodiazepine misuse. Reference McHugh, Geyer, Chase, Griffin, Bogunovic and Weiss29 These findings may reflect stigma toward mental illness and professional norms emphasising emotional restraint among Asian healthcare workers. Consequently, physicians – particularly men – may be less likely to recognise work stress or seek formal mental healthcare, which could contribute to greater reliance on benzodiazepines. Reference Dalum, Tyssen, Moum, Thoresen and Hem30 Future research is warranted on whether the gender differences between Asian and American healthcare providers rises from cultural differences in the social expectations for male professionals.

The finding that physicians who specialised in family medicine or otorhinolaryngology were more likely to use benzodiazepines was noteworthy. Previous studies reported that emergency physicians had the highest rates of burnout and benzodiazepine use among specialised physicians. Reference Shanafelt, Boone, Tan, Dyrbye, Sotile and Satele31,Reference Liou, Li, Ho and Lee32 In Taiwan, physicians who specialised in family medicine and otorhinolaryngology were mostly at the primary care level in the National Health Insurance programme. Reference Wang, Liu, Chen, Hwang, Chou and Lin33 Therefore, our results echoed those of a previous USA study, which revealed that substantial differences in burnout were observed by speciality, with the highest rates among physicians at the front line of care access (family medicine, general internal medicine and emergency medicine). Reference Shanafelt, Boone, Tan, Dyrbye, Sotile and Satele31 Lower pay, prolonged working hours and a higher risk of facing emerging infectious diseases Reference Al Maqbali, Alsayed, Hughes, Hacker and Dickens34 could be stressors for family physicians and otorhinolaryngologists, and could further lead to benzodiazepine use. Notably, these results represent population-level prescribing patterns observed in the data-set and should not be interpreted as evidence of inappropriate practice, personal shortcomings or misconduct by individual physicians. The associations identified may reflect systemic prescribing behaviours rather than characteristics inherent to the specialities themselves.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study was that we used registered data to diagnose mental disorders instead of self-reported psychological symptoms. This study has several limitations. First, the NHIRD lacked information on working conditions and hours, health behaviours such as alcohol consumption, and family history of mental disorders. These were all potential risk factors for benzodiazepine use, and a bias attributable to the existence of unknown confounders may exist. Second, benzodiazepine use could be a result of comorbidities other than sleep, anxiety and depressive disorders. However, the NHIRD does not include information on the clinical indications for benzodiazepine prescriptions, the severity of symptoms or the physicians’ rationale for prescribing benzodiazepines. Consequently, the appropriateness of benzodiazepine use cannot be determined in this study. Third, we used medical claims data on benzodiazepine prescriptions; however, user adherence with the prescription regimen was not available. Similarly, the diagnosis of mental disorders was based on NHIRD physician coding, which may introduce misclassification bias. On one hand, diagnoses may have been recorded for reimbursement purposes in cases of self-prescription without a complete specialist assessment. On the other hand, mood disorders such as depression in individuals who did not seek medical care were not captured as diagnosed cases in our analysis. Reference Chang, Liao, Chang, Wu, Huang and Hwang35 Fourth, our analysis focused on physicians in Taiwan and might not be generalisable to physicians in other countries because of differences in healthcare systems and policies.

Implications for research and/or practice

Benzodiazepines have a great chance of liability. In addition to dreadful complications, such as memory impairment, vehicle accidents, falls, respiratory arrest and withdrawal symptoms, such as life-threatening delirium, benzodiazepines can enable dependence and tolerance. Reference Fluyau, Revadigar and Manobianco36 Discontinuation of benzodiazepine use requires treatments that range from pharmacological management to psychotherapies, such as cognitive–behaviour therapy. Reference Brett and Murnion37,Reference Otto, McHugh, Simon, Farach, Worthington and Pollack38 Recovery among physicians with substance use disorders is good. Reference Rose, Campbell and Skipper14 Nevertheless, physicians were notoriously reluctant to seek help for mental problems or substance misuse. Reference Harvey, Epstein, Glozier, Petrie, Strudwick and Gayed39 In Taiwan, benzodiazepine prescriptions are regulated and monitored, which may help deter inappropriate self-medication. However, on-site education remains essential – not only to reinforce prescribing standards for benzodiazepines, but also to but also to enhance primary care physicians’ self-awareness and equip them with effective stress-coping strategies. Reference Liu, Tang, Weng, Lin and Chen40 Furthermore, sleep difficulties following night shifts has been observed to be associated with benzodiazepine use among physicians. Reference Ferguson, Shoff, McGowan and Huecker41 Organisational-level interventions, such as shift schedule design, have shown potential in mitigating adverse health effects of shift work. Reference Shriane, Ferguson, Rigney, Gupta, Kolbe-Alexander and Sprajcer42

In conclusion, male and older physicians were more likely to be benzodiazepine users. Specialities in otorhinolaryngology and family medicine, both at the frontline of care access in Taiwan, were the most likely for benzodiazepine use. Psychiatric comorbidities that included depression and sleep disorders increased the probability of benzodiazepine use. Educating physicians on effective stress management and workplace-based strategies for improving physicians’ health are essential. Future studies are needed to explore indications for benzodiazepine use among physicians, and physicians’ attitudes toward benzodiazepine use.

Data availability

We are not allowed to share the data for public use owing to constraints on data-sharing permissions from the Health and Welfare Data Science Center (HWDC) in Taiwan.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Health Data Science Center of China Medical University Hospital for providing administrative, technical and funding support.

Author contributions

W.-J.C. conceived the study, contributed to study methodology and funding acquisition, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Y.-C.C. and H.-C.W. conceived the study. H.-T.Y. contributed to project administration, study methodology and formal analysis, and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. C.-L.L. contributed to project administration, study methodology and revised analysis, and revised the original draft of the manuscript. C.W.-S.L. conceived and supervised the study, contributed to study methodology, wrote the original draft of the manuscript and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially supported by the Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial Center (grant number MOHW112-TDU-B-212-144004) and China Medical University Hospital (grant numbers DMR-111-105 and DMR-112-087).

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.