14.1 Introduction

The preceding manifesto has three aspects. First, it is about bringing climate change discussions into classrooms (and particularly in Ugandan classrooms). Second, it is about bringing Ugandan experiences of climate education into classrooms. And third, it is about helping children and communities make sense of climate change in their lives and futures. Climate change is often understood through the prism of personal experience – blinding us to the connections between our actions, or the issues affecting us, and life in other parts of the world. ‘Think global and act local’ is an overused phrase. But it remains an important concept given our increasing interconnectedness; solutions cannot be found in one country – we must raise global awareness and stoke both local and global action. In this practitioner’s response, Luke reflects on his personal experiences of living in Japan and explains the thinking behind the development of a sustainable curriculum he co-developed as a school leader in the UK.

14.2 Practitioner Wisdom from Japan, Looking Back to Cambridge, UK

When I moved from the UK to Japan, I had to reaccustom myself with the country’s carefully observed protocols regarding how, when and where to dispose of different types of recycling. Across Japan, on collection days, paper and cardboard boxes are meticulously folded, tied and arranged in designated places. However, one small rural town in Shikoku has gone above and beyond in its efforts to deal with waste and live sustainably. In only a few years, the small community of Kamikatsu has become known across the world as a model ‘zero waste’ town. Residents have attracted attention for their dedication to separating their waste into no less than forty-five different categories. Beyond this headline, many other local sustainability initiatives thrive – with businesses, restaurants and factories all producing new products from collected waste.

What struck me about Kamikatsu’s transformation was the journey that residents were asked to go on to change their daily habits. Akira Sakano (pers. comm.), founder of Zero Waste Japan, recalls, ‘We were burning our waste in the open air, in a big hole, which was obviously hurting our environment, our air and potentially our health.’ Several inhabitants, who later became strong advocates of the town’s approach, were initially resistant to the proposed changes to recycling, perplexed about the number of ways they had to separate their rubbish. However, the process of changing norms led to shared realisations around their use of resources, reducing unnecessary waste and rethinking what could be reused. As one resident reflected, ‘For me, Zero Waste is a way to understand myself. When you live in Kamikatsu, you will not only know about waste, but also about the time you have, what you spend your effort on, how you spend your money and how waste is produced as a result’ (Ding, Reference Ding2021).

What educational lessons can we learn from these examples of environmentally conscious living? The insights and forms of participation cultivated in Kamikatsu resonate with Cross’ (Reference Cross2022) conception of citizenship ‘not as a status, but as something that people continuously do: citizenship as practice’. Cross cites Kerr’s claim that most citizenship curricula have only managed ‘to reinscribe a passive, dutiful version of citizenship that fails to inspire or convince’. An alternative is the Japanese educational concept of ‘Tokkatsu’ (Tsuneyoshi, Reference Tsuneyoshi2020) – school activities and cultures that work to develop holistic education, positive personal habits and social and ethical responsibility. In Japanese schools, such ‘special activities’ include children cleaning their classrooms, planting rice with a local farmer or having a classroom meeting about effecting change in their community (Bloomberg Quicktake, 2020). Unfortunately, such experiential knowledge, or, as Bertrand Russell (Reference Russell1910) put it, ‘knowledge by acquaintance’, is given less emphasis in many other education systems

What follows are three cases from the UK, India and Nepal. They all focus on the development of curricula that position sustainability as central to children’s learning. The first concerns the design of a school curriculum, drawing from local research and expertise. This is the most detailed case study, shining a light on the considerations that shape curriculum development from start to finish. The second and third cases are shorter and set out final curricula decisions. The second describes a set of co-created of curricula resources, again drawn from a range of contextually specific expertise. The third sketches how a commitment to living sustainably can be situated at the core of the learning experiences embedded in a curriculum.

Case Study 1: Designing a Curriculum for Sustainability

The University of Cambridge Primary School (UCPS) is situated in a new University residential development, and sustainability is central to its design. As well as working closely with the Faculty of Education, the school teams up with other organisations at the University, such as Cambridge Zero, a solution-focused initiative harnessing research and expertise to respond innovatively to the climate crisis that is led by Professor Emily Shuckburgh.

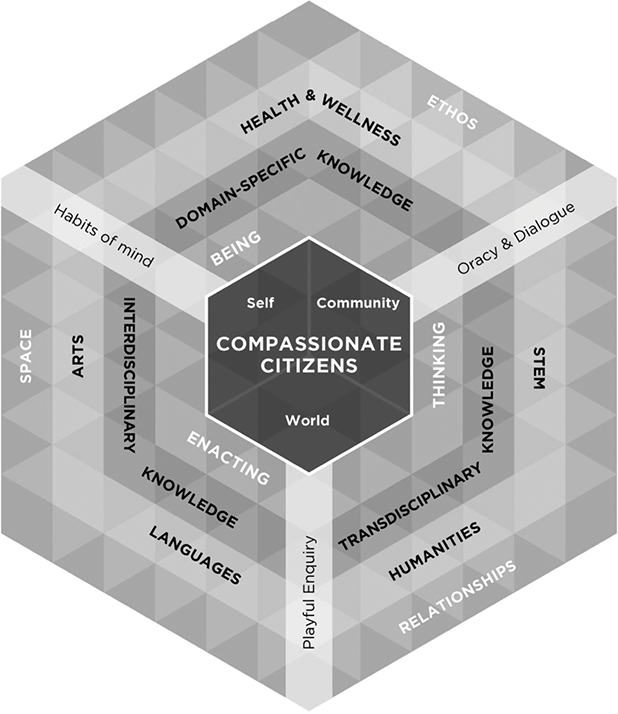

There are various sustainability initiatives in contemporary educational practice. At the UCPS, we were interested in looking broadly at how a curriculum for teaching sustainability could be introduced for children from ages three to eleven and beyond. What would a curriculum for developing sustainability competences look like? What knowledge, behaviours and competencies do our children need to flourish? How might these intersect with other types of pedagogy? The curriculum design model in Figure 14.1 attempts to illustrate how the aim of nurturing compassionate citizens relates to school culture and ethos, and how both interact with particular forms of knowledge. We distinguished between three different forms of knowledge (Table 14.1).

Figure 14.1 Curriculum design model.

Figure 14.1Long description

From outer to inner hexagons: 1. Space, ethos, relationships; 2. Arts and languages, humanities and STEM, health and wellness; 3. Interdisciplinary knowledge, domain-specific knowledge, transdisciplinary knowledge; 4. Enacting, being, thinking. In the central hexagon alongside the title, compassionate citizens: self, community, world. Additional radial components detail: habits of mind, oracy and dialogue, playful enquiry.

Table 14.1 Definitions of three forms of curriculum knowledge.

- Domain-specific knowledge

Specialised forms of subject-specific knowledge

- Interdisciplinary knowledge

Knowledge that arises through making meaningful connections between different subjects across the curriculum

- Transdisciplinary knowledge

Concepts or ‘big ideas’ that transcend subject boundaries

While domain-specific and to a lesser extent interdisciplinary knowledges are commonly taught in schools, the third category, transdisciplinary knowledge (Arnold, Reference Arnold2020), is less common. However, we thought it might hold significant potential for binding different subject areas together in meaningful ways. To decide what these transdisciplinary knowledge categories would be, we conducted a consultation, asking our broader school community – academics, parents, children and teachers – what they thought. After several iterations, five themes became apparent:

1) Health and spirit

2) Sustainability

3) Diversity and relationships

4) Power and systems

5) Technology

We then worked out how each of these areas mapped onto different subject areas and curriculum projects. For the category of Sustainability, several principles emerged in considering curriculum progression:

Experiencing the value of nature. Education on sustainability muststart early, with experiences that help children appreciate the joy and well-being associated with being in nature. This can be achieved by timetabling experiences such as Forest School, where children engage in hands-on outdoor learning in nature, before going on to learn about different aspects of sustainability, such as climate change.

Sequencing content carefully. We created curriculum progression maps for each subject, outlining core substantive and disciplinary knowledge and vocabulary, as well as subject-specific concepts, such as ‘place and space’ in geography.

Starting local. Before engaging children in big global environmental challenges, we start with local issues and the changes and practices children can make in their own school community and lives.

Identifying anchoring subject areas. We avoided creating an extra subject or lesson out of sustainability. Rather, we used existing subject disciplines as lenses through which to understand the world and what it means to live sustainability. We drew on geography, science, Forest School, art and personal, social, health and citizenship education as the drivers of sustainability learning in the curriculum.

Together, these principles give rise to a rigorous curriculum that develops ‘powerful knowledge’ (Lambert, Reference Lambert2017), alongside wider, longer-term aims of nurturing children’s ‘learning autonomy’ (James et al., Reference James2007). However, in practice, such principles are not easy to realise and require educators to draw on different ‘pedagogical repertoires’ (Alexander, Reference Alexander2000). These repertoires might include aspects of experiential learning and personal reflection, alongside important substantive and disciplinary knowledge. For example, in learning about deforestation and reduced biodiversity in Brazilian rainforests, children might reflect on their own consumer behaviours and any changes they are able to make. Classes may discuss how the school sources its own food and whether it is sustainable. Small examples like this demonstrate how subject learning (in this case, in geography) can lead to new understandings about our lives, while generating questions about the changes necessary in our communities.

When teaching issues relating to sustainability, we were conscious not to give children self-directed projects about complex areas like climate change before they were familiar with the concepts necessary to have a deep understanding of the ideas involved. As such, we spent time considering curriculum sequencing. For example, in geography, we knew that children would need to some understanding of weather and biomes to grapple with concepts like climate and climate zones. In science, children would need a basic grounding in the ideas of ‘living things’ and ‘habitats’ before exploring questions of biodiversity. Without careful mapping of subject progressions, it is also difficult to understand interdisciplinary connections. By contrast, by mapping subject progressions, students could see that energy and electricity (learned about in science) connected with learning about populations, the planet and globalisation. Similarly, learning about migration helped their understanding of the impact of climate change on the lives of environmental migrants.

The UCPS curriculum strives to find a balance between important subject knowledge and bigger transdisciplinary concepts. By treating sustainability as a core curriculum theme through both formal teaching and practical experiences, children are invited to engage with bigger human conversations (Wegerif, Reference Wegerif2019) about how they can live in a symbiotic way with the planet – within their own lives, their local communities and the wider world.

Case Study 2: Pani Pahar – the Water Curriculum

Water is a precious resource. As industrialisation and migration increase, the question of fair water distribution will become more critical. How can we develop curricula in these contexts? This case study offers an example of innovative, transdisciplinary thinking about curricula design.

From 2017 to 2023, work to develop knowledge and understanding about water and its management was developed with the University of Cambridge and the Hearth Advisors, a division of Canta Consultants LLP. ‘Pani Pahar – Waters of the Himalayas’ grew out of a collaborative research project between the University of Cambridge, the Centre for Ecology Development and Research in India and the South Asia Institute for Advanced Studies in Nepal. The project explores the changing landscapes and escalating water crises of the Indian Himalayas. It combines academic research led by Cambridge pro-vice-chancellor for education Professor Bhaskar Vira and Dr Eszter Kovacs, then at Cambridge’s Department of Geography (now at University College London), with imagery by photojournalist Toby Smith, since exhibited in the UK and India. Professor Vira explains the purpose of the curriculum and resource materials:

These school materials are designed to allow young people, who are highly mobilised through the school strikes for climate, to develop a critical engagement with these issues, with learning resources and educational materials that are targeted at different stages of the secondary school curriculum. We wanted to show the links between our research on water scarcity and broader concerns about environmental change and crises.

Designed for students between the ages of nine and fifteen, the Pani Pahar curriculum has been freely available to teachers and schools since 2020. The aim of the curriculum is to engage students in experiential learning and to instil a sense of responsibility for water conservation and environmental sustainability. The curriculum preparation and instructional design was led by the Hearth Advisors, based on research conducted at the University of Cambridge.

The curriculum aims to help students understand water resources and sustainability and how they are impacted by climate change. The detailed lesson plans encourage reflection and research on the human causes of water scarcity, and some of the effects of environmental change on humans and our shared resources. It also helps students understand the meaning of activism, recognise some of the challenges associated with activism, and begin to associate activism with the needs and issues of their school.

Each curriculum includes the following:

Introduction to the curriculum

Curriculum rationale

Curriculum outline

Guide on how to use the lesson plans

Lesson plans (with resources/learning material)

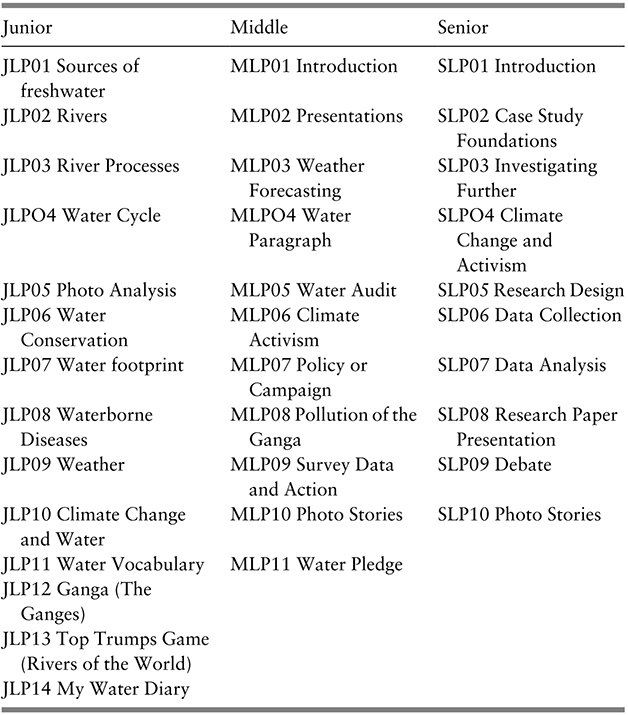

The lesson plans included in this water curriculum are as in Table 14.2.

Table 14.2Long description

The table has three columns: Junior, Middle, and Senior. It reads as follows: Row 1: Junior Level Project 01 Sources of freshwater; Middle Level Project 01 Introduction; Senior Level Project 01 Introduction. Row 2: Junior Level Project 02 Rivers; Middle Level Project 02 Presentations; Senior Level Project 02 Case Study Foundations. Row 3: Junior Level Project 03 River Processes; Middle Level Project 03 Weather Forecasting; Senior Level Project 03 Investigating Further. Row 4: Junior Level Project 04 Water Cycle; Middle Level Project 04 Water Paragraph; Senior Level Project 04 Climate Change and Activism. Row 5: Junior Level Project 05 Photo Analysis; Middle Level Project 05 Water Audit; Blank. Row 6: Junior Level Project 06 Water Conservation; Middle Level Project 06 Climate Activism; Senior Level Project 05 Research Design. Row 7: Junior Level Project 07 Water footprint; Middle Level Project 07 Policy or Campaign; Senior Level Project 06 Data Collection. Row 8: Junior Level Project 08 Waterborne Diseases; Middle Level Project 08 Pollution of the Ganga; Senior Level Project 07 Data Analysis. Row 9: Junior Level Project 09 Weather; Middle Level Project 09 Survey Data and Action; Senior Level Project 08 Research Paper Presentation. Row 10: Junior Level Project 10 Climate Change and Water; Middle Level Project 10 Photo Stories; Senior Level Project 09 Debate. Row 11: Junior Level Project 11 Water Vocabulary; Middle Level Project 11 Water Pledge; Senior Level Project 10 Photo Stories. Row 12: Junior Level Project 12 Ganga (The Ganges); Blank; Blank. Row 13: Junior Level Project 13 Top Trumps Game (Rivers of the World); Blank; Blank. Row 14: Junior Level Project 14 My Water Diary; Blank; Blank.

The full curriculum can be downloaded as a free resource and has potential to be adapted to different localities and contexts: https://thehearthadvisors.com/our-work/pani-pahar-the-water-curriculum/.

Case Study 3: Harmony

The Harmony Project aims to transform education to ensure it prepares young people for life in the twenty-first century, not just to pass exams. The Harmony Project envisions a way of learning to live that is based on a deep understanding of – and connection to – the natural world. The project works with teachers and other educators in the UK to reframe teaching and learning around nature and the idea of the world as an interconnected whole. This approach can help young people better understand the world and develop the skills they need to act within it. In doing so, they will learn how to live more sustainably.

The Harmony Project is led by Richard Dunne. In his thirty-year career in education, Richard has developed a school curriculum based on nature’s principles of harmony. These principles guide and inform the way a ‘Harmony curriculum’ is structured, providing a coherent and meaningful framework through which National Curriculum learning objectives can be delivered. They include the following:

The principle of Interdependence, revealing that elements within natural systems are interconnected; each element has a value and a role to play

The principle of the Cycle, illustrating that Nature’s regenerative, cyclical systems are models of sustainability, reusing resources and eliminating waste

The principle of Diversity, expressed in natural systems which are healthy and resilient and better able to adapt to change

The principle of Adaptation, showing that living things are always adapting to their place and to the ecosystems they are part of, which ensures each species is able to survive and thrive

The principle of Health, demonstrating that the balance and well-being of natural systems is maintained by the dynamic relationships that exist within them

The principle of Geometry, revealing that the patterns we see in Nature, in micro and macro form, also exist in us – far from being separate from Nature, we are Nature

The principle of Oneness, uniting all the foregoing principles, revealing their interconnectedness and helping us to understand that – like all life on Earth – we are part of something greater than ourselves

For an in-depth understanding of ways to develop a Harmony approach to education, see www.theharmonyproject.org.uk.

Over to You

Given that a generation of children have now grown up in the context of a global climate crisis, the case for making sustainability central to school curricula is overwhelming. When considering curriculum aims and purpose, we should refer to Kamikatsu town’s injunction to think ‘about the future of the living environment … as one’s own responsibility and foster people who can take action’ (Kamikatsu, 2021). Such a perspective could help educators create learning experiences that go beyond simply informing students, towards mobilising our future citizens to think and act in new ways.

This chapter asks us how we might bring this about. And now, at the end, we are left with a series of questions designed to open up conversations in your own educational context:

What are the aims of a curriculum, and how coherent is the focus given to sustainability?

How does progression in individual subjects contribute to providing unique lenses to help children to understand issues in sustainability? What meaningful connections can be brought out between the learning in these subjects?

Rather than indoctrinating children in a ‘correct’ way of thinking about sustainability, what pedagogies can be employed to draw children into a wider dialogue about the issues facing the planet?

How are children given opportunities to practically live out what they have learned about sustainability?

What opportunities for pupil voice, school and community change are designed into children’s curriculum experiences?