Introduction

Marmosets of the genus Callithrix in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest are threatened not only by habitat loss and fragmentation but also by the introduction of congeneric species released to areas outside their natural geographical ranges. Notable examples of the latter include the common marmoset Callithrix jacchus, the Geoffroy’s tufted-ear marmoset (also known as the white-faced marmoset) Callithrix geoffroyi, and the black-pencilled marmoset (also known as the black-tufted-ear marmoset) Callithrix penicillata. These species are now widely distributed in the natural ranges of two threatened marmosets in the montane forests of south-east Brazil, the buffy-headed marmoset Callithrix flaviceps and the buffy-tufted-ear marmoset Callithrix aurita (Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Bergallo, Cronemberger, Guimarães-Luiz, Souza and Jerusalinsky2018; Malukiewicz, Reference Malukiewicz2019; Malukiewicz et al., Reference Malukiewicz, Cartwright, Curi, Dergam, Igayara and Moreira2021). These introductions have resulted in the establishment of breeding populations, competition and, potentially, hybridization with native species, pathogen transmission and predation of bird eggs (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Alvarenga and Boere2008; Sales et al., Reference Sales, Ruiz-Miranda and Santos2010; Ruiz Miranda et al., Reference Ruiz-Miranda, Morais Júnior, Paula, Grativol and Rambaldi2011; Oliveira & Grelle, Reference Oliveira and Grelle2012; Melo et al., Reference de Melo, Ferraz, Valença-Montenegro, Oliveira, Pereira and Port-Carvalho2015; Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Bergallo, Cronemberger, Guimarães-Luiz, Souza and Jerusalinsky2018; Malukiewicz et al., Reference Malukiewicz, Cartwright, Curi, Dergam, Igayara and Moreira2021). Hybridization in Callithrix can produce fertile offspring with intermediate traits (Coimbra Filho et al., Reference Coimbra-Filho, Pissinati and Rylands1993; Mendes, Reference Mendes1997; Fuzessy et al., Reference Fuzessy, de Oliveira Silva, Malukiewicz, Silva, do Carmo Pônzio, Boere and Ackermann2014; Malukiewicz et al., Reference Malukiewicz, Boere, Fuzessy, Grativol, Silva and Pereira2015), compromising the genetic integrity of native species (Todesco et al., Reference Todesco, Pascual, Owens, Ostevik, Moyers and Hubner2016). The greatest hybrid reproductive success occurs between invasive females and native males, resulting in complex backcrossing and continued hybrid interbreeding (Nogueira et al., Reference Nogueira, de Carvalho, de Oliveira, de Paula, Pereira and Pissinatti2022). These findings highlight the conservation importance of identifying and prioritizing individuals that still retain a majority (> 50%) of the native genome, as they represent the remaining genetic reservoir of the threatened species and are therefore essential for maintaining evolutionary potential (Wayne & Shaffer, Reference Wayne and Shaffer2016; Nogueira et al., Reference Nogueira, de Carvalho, de Oliveira, de Paula, Pereira and Pissinatti2022).

In Rio Doce State Park in the Atlantic Forest of south-east Brazil, the genetic integrity of C. aurita is threatened by the presence of C. geoffroyi and C. penicillata (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Vale, Alves, Mittermeier and Papavero1983; Coimbra-Filho, Reference Coimbra-Filho1984; IEF, 2001; Oliveira & Grelle, Reference Oliveira and Grelle2012; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Malukiewicz, Silva, Carvalho, Ruiz-Miranda and Coelho2018). Callithrix geoffroyi naturally occurs in other areas of the Atlantic Forest, with a geographical range extending to the Piracicaba River (the natural barrier between C. geoffroyi and C. aurita) north of the Park, and C. penicillata inhabits the Cerrado (the savannah of central Brazil) and Caatinga (a semi-arid landscape in north-east Brazil) biomes further west beyond the vicinity of the Park. The Doce River, east of the Park, is the natural boundary between C. flaviceps and C. aurita. Both C. geoffroyi and C. penicillata were probably released into the Park by environmental agencies after animals were rescued from the illegal wildlife trade (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Vale, Alves, Mittermeier and Papavero1983; Coimbra-Filho, Reference Coimbra-Filho1984; IEF, 2001; Morais Júnior et al., Reference Morais Júnior, Ruiz-Miranda, Grativol, Andrade, Lima, Martins and Beck2008; Ruiz-Miranda et al., Reference Ruiz-Miranda, Morais Júnior, Paula, Grativol and Rambaldi2011). There is a need for research on hybridization and competition between C. geoffroyi, C. penicillata and C. aurita (IEF, 2001; Silva & Carvalho, Reference Silva and Carvalho2015). Early surveys identified C. geoffroyi and C. penicillata as allochthonous species (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Vale, Alves, Mittermeier and Papavero1983), with subsequent studies documenting hybrids amongst all three marmoset species (Coimbra-Filho, Reference Coimbra-Filho1984; Stallings et al., Reference Stallings, Fonseca, Pinto, Aguiar and Sábato1991; Hirsch, Reference Hirsch1995, Reference Hirsch2003; Hirsch et al., Reference Hirsch, Toledo, Brito and Rylands1996).

Callithrix aurita is categorized as Endangered on both the Brazil Official List of Endangered Species (MMA, 2022) and the IUCN Red List (de Melo, Reference de Melo, Port-Carvalho, Pereira, Ruiz-Miranda, Ferraz and Bicca-Marques2021c). The species has undergone significant population declines (de Melo et al., Reference de Melo, Ferraz, Valença-Montenegro, Oliveira, Pereira and Port-Carvalho2015, Reference de Melo, Ferraz, Valença-Montenegro, Oliveira, Pereira and Port-Carvalho2018) and is considered one of the most threatened primates (Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Fransen, Valença-Montenegro, Dunn, Igayara-Souza, Port-Carvalho, Schwitzer, Mittermeier, Rylands, Chiozza, Williamson and Byler2019) and in need of urgent protection (ICMBio/MMA, 2018). The congeneric species, C. geoffroyi and C. penicillata, are categorized as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List (de Melo, Reference de Melo, Pereira, Kierulff, Bicca-Marques and Mittermeier2021b; Valle, Reference Valle, Ruiz-Miranda, Pereira, Rímoli, Bicca-Marques and Jerusalinsky2021).

Effective management plans and conservation strategies depend on accurate population estimates but these are often difficult to obtain because of challenging environmental conditions, species rarity, imperfect detection and observer errors (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Elkin, Martin and Possingham2009; Kellner & Swihart, Reference Kellner and Swihart2014). N-mixture models use a hierarchical approach to estimate abundance while accounting for imperfect detection under difficult conditions (Royle, Reference Royle2004). They have been shown to be an effective tool for estimating primate abundance (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Elkin, Martin and Possingham2009; Froese et al., Reference Froese, Contasti, Mustari and Brodie2015; Senzaki et al., Reference Senzaki, Yamaura and Nakamura2015; Belant et al., Reference Belant, Bled, Wilton, Fymagwa, Mwampeta and Beyer2016; Coelho et al., Reference Coelho, Collins, Santos Junior, Valença-Montenegro, Jerusalinsky and Alonso2020).

Marmosets are difficult to count in forest environments particularly when they are inactive. Therefore, we estimated abundance and detection probability in the Rio Doce State Park using data from repeated playback of vocalizations to attract marmosets to an observation point, based on the protocol of Coelho et al. (Reference Coelho, Collins, Santos Junior, Valença-Montenegro, Jerusalinsky and Alonso2020), and N-mixture models. We expected marmosets to be more abundant near forest edges, in dense secondary forest with tangles of lianas and epiphytes, in areas with greater food resources (Rylands & Faria, Reference Rylands, Faria and Rylands1993; Norris et al., Reference Norris, Rocha-Mendes, Marques, Nobre and Galetti2011), and around areas of human activity such as roads, tourist areas and urban communities, where they feed opportunistically (Stevenson & Rylands, Reference Stevenson, Rylands, Mittermeier, Rylands, Coimbra-Filho and da Fonseca1988; Detogne et al., Reference Detogne, Ferreguetti, Mello, Santana, Dias and Mota2017; Secco et al., Reference Secco, Grilo and Bager2018). We expected detection probability to increase with survey effort but to decrease with adverse weather conditions, particularly high rainfall, which can hinder marmoset activity (Côrrea, Reference Côrrea1995; Hilário et al., Reference Hilário, Silvestre, Abreu, Beltrão-Mendes, de Castro and Chagas2022).

Study area

Rio Doce State Park covers 36,000 ha in Minas Gerais state, south-east Brazil (Fig. 1a-b). It is the largest Atlantic Forest remnant in the state, hosting rich biodiversity and many endemic species (IEF, 2001). In addition to the three species of marmoset, there are four other primates: the brown howler monkey Alouatta guariba, northern muriqui Brachyteles hypoxanthus, black-fronted titi monkey Callicebus nigrifrons and black-horned capuchin Sapajus nigritus. Together, they represent 25% of all Atlantic Forest primates (IEF, 2001).

Fig. 1 Geographical context, distribution ranges of Callithrix species and survey design in Rio Doce State Park, Minas Gerais, Brazil. (a) Minas Gerais state, with the distributions of Callithrix aurita (de Melo et al., Reference de Melo, Port-Carvalho, Pereira, Ruiz-Miranda, Ferraz and Bicca-Marques2021c), Callithrix flaviceps (de Melo et al., Reference de Melo, Hilário, Ferraz, Pereira, Bicca-Marques and Jerusalinsky2021a), Callithrix geoffroyi (de Melo et al., Reference de Melo, Pereira, Kierulff, Bicca-Marques and Mittermeier2021b) and Callithrix penicillata (Valle et al., Reference Valle, Ruiz-Miranda, Pereira, Rímoli, Bicca-Marques and Jerusalinsky2021), and (b) the location of Rio Doce State Park, indicating survey hexagons and the abundance of Callithrix spp. (abundance is based on the most decisive predictor variable for influencing this parameter; Table 2). (c) The hexagonal survey design, with each side 205 m long and a total area of 11 ha, used for playback of the C. flaviceps long-call in the marmoset surveys.

The Park’s submontane seasonal semideciduous forest occurs at 230–515 m altitude across several successional stages (Gilhuis, Reference Gilhuis1986; IEF, 2001; Silva & Carvalho, Reference Silva and Carvalho2015). The climate is humid tropical, with rainfall during October–March and a dry season during April–September (IFMG, 2021). Annual rainfall averages 1,075 mm (1,001–1,150 mm) in the wet season and 200 mm (150–250 mm) in the dry season (IFMG, 2021). Mean daily temperature is 22–26 °C in the rainy season and 19–22 °C in the dry season (IFMG, 2021). Located in a region of high industrial activity, monocultures of Eucalyptus spp., small agro-silvopastoral properties and urban expansion (IEF, 2001), the Park faces significant environmental pressures. It was indirectly affected by a tailings dam disaster in 2015 that released millions of tons of mining waste and contaminated the Rio Doce and its floodplain, causing significant aquatic mortality and disrupting access to water for wildlife (Rocha, Reference Rocha2021).

Methods

Surveys

We established 106 hexagonal survey sites at 410 m intervals along 14 trails within the Park (Fig. 1b); other areas were inaccessible. Each hexagon covered 11 ha (205 m per side) and was centred on a marmoset call playback point (Fig. 1c). We surveyed each hexagon 1–5 times during 6 months (May–October 2021), a period chosen to minimize violations of the closed population assumption in N-mixture models (Royle, Reference Royle2004) considering that callitrichids are territorial and associate in cohesive groups (Côrrea et al., Reference Côrrea, Coutinho and Ferrari2000). This design ensured that playback could not be heard by marmosets in adjacent hexagons, preserving the independence of sampling points, and the survey area aligned with the home range of C. aurita, which is < 11 ha (Muskin, Reference Muskin1984; Rylands & Faria, Reference Rylands, Faria and Rylands1993).

We randomized the order in which trails were surveyed. Once a trail was selected, all hexagons intersecting that trail were surveyed sequentially. On each occasion, we broadcast marmoset calls over a portable sound system for 2 min 30 sec in each cardinal direction, followed by 2 min 30 sec of listening, repeated four times for a total of 20 minutes per visit, between 06.00 and 13.00 (Fig. 1c). We sourced standardized and high-quality call recordings from Carvalho et al. (Reference Carvalho, Fransen, Valença-Montenegro, de Melo, Souza and Possamai2025), and used standard audio equipment comprising a sound amplifier and a tweeter that emitted sounds at 2–20 kHz with a range of c. 200 m. We broadcast the C. flaviceps long-call, which is answered by any congeneric species and has proved effective in previous research with C. aurita (da Silva et al., Reference da Silva, Ribeiro, Hasui, da Costa and da Cunha2015).

Two observers, 5 m apart, monitored responses to the playback and tracked the direction of any marmoset respondents while a third observer identified the species, to avoid double counting (Fig. 1c). Identification relied on ear tuft appearance, pelage colour and facial features, key traits for distinguishing species and hybrids (Vivo, Reference Vivo1991; Coimbra-Filho et al., Reference Coimbra-Filho, Pissinati and Rylands1993; Fuzessy et al., Reference Fuzessy, de Oliveira Silva, Malukiewicz, Silva, do Carmo Pônzio, Boere and Ackermann2014).

Modelling abundance and detection probability

We used N-mixture models, a type of occupancy model, to estimate two parameters modelled as a function of predictor variables: r, the detection probability at a survey point, and λ, the abundance at that survey point (Royle, Reference Royle2004). We input counts of the number of animals (N) observed on each occasion (or visit) at each point within each hexagon. The models assume that there are N animals at a survey point and the probability of detecting one or more individuals, given the point is occupied, is 1–(1–r)N. The spatial distribution of N follows a Poisson distribution with mean λ (Royle, Reference Royle2004).

We identified 12 potential predictor variables: per cent tree canopy cover, circumference of trees at breast height (1.6 m), density of trees, numbers of lianas and epiphytes per tree, distances to nearest forest edge, road, tourist area and urban area, survey effort, and mean daily precipitation and temperature (Table 1). We randomly assigned five points within each hexagon and measured tree variables at one point per visit. Within the four quadrants, one in each cardinal direction around each point, we measured the circumference and counted the number of lianas and epipphytes for the nearest tree. We averaged canopy cover for each hexagon using CanopyApp 1.0.4 (University of New Hampshire, 2018), which estimates canopy closure based on a digital photograph. We averaged tree circumferences at breast height for mature trees (> 20 cm). We estimated tree density using the mean distance to the nearest trees in the four cardinal directions, with higher index values (i.e. trees spaced further apart) indicating lower tree density.

Table 1 Mean values and range of the variables used to model the abundance (λ) and detection probability (r) of Callithrix spp. in Rio Doce State Park, in Minas Gerais, Brazil (Fig. 1), recorded in or from the 106 hexagonal survey sites.

The distances from each hexagon’s centroid to the nearest forest edge (using the legally defined boundary of the Park), road, tourist area and urban area were measured with ArcGIS 10.8.1 (Esri, USA) using shapefiles for the Park (IEF, 2001) and data from Google Earth Pro 7.3.4 (Google, 2021). We obtained mean daily precipitation and temperature from meteorological stations in Caratinga, Timóteo and the Park’s station in Marliéria (INMET, 2021). Effort was the number of surveys per hexagonal site. We assessed correlations amongst predictor variables using Pearson’s correlation test, finding no strong correlations (|r| < 0.70) (Dormann et al., Reference Dormann, Elith, Bacher, Buchmann, Carl and Carré2012).

Data analysis

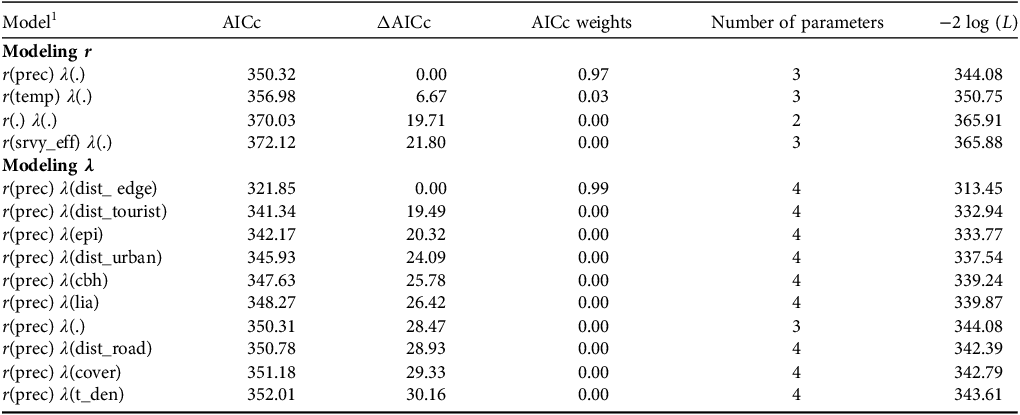

We recorded individual counts of marmosets per survey visit per hexagon. Overdispersion (ⓒ > 1) was assessed using Pearson’s χ 2 test in the AICcmodavg package in R 4.0.3 (Mazerolle, Reference Mazerolle2016; R Core Team, 2020), with results showing no overdispersion (ⓒ = 1.638, χ 2 = 379.865; P = 0.078) We built the models in MARK (White & Burnham, Reference White and Burnham1999) using the Akaike information criterion corrected for small samples (AICc) to select the most parsimonious model structures (ΔAICc ≤ 2) and determine key variables (Burnham & Anderson, Reference Burnham and Anderson2002). Following a step-down model selection (Lebreton et al., Reference Lebreton, Burnham, Clobert and Anderson1992), we first fixed a null structure (i.e. only the intercept) for λ (marmoset abundance) and built univariate models for r (detection probability). We fixed the highest-ranked model (ΔAICc ≤ 2), which contained the variable that most influenced r, to model the parameter λ, and then used the same method to build univariate models. We built four models for r and 10 models for λ (Table 2). As a result of the low number of marmoset records, it was not feasible to further parameterize structures for λ when modelling r but a recent study showed that this does not significantly affect the results (Morin et al., Reference Morin, Yackulic, Diffendorfer, Lesmeister, Nielsen and Schauber2020). We summed density estimates for each hexagon to estimate total marmoset abundance across all hexagons and divided this value by the total area surveyed (1,166 ha) to estimate the number of marmosets per ha. We estimated the number of Callithrix groups by dividing the total number of individuals by the average group size per hexagon using data reported in the literature (Muskin, Reference Muskin1984; Oliveira et al., Reference Oliveira, Câmara, Hirsch, Paschoal, Alvarenga and Belarmino2003; IUCN, 2025).

Table 2 Selection of models used to evaluate variables that influence the abundance (λ) and detection probability (r) of Callithrix spp. in Rio Doce State Park. Models were classified using the Akaike information criterion adjusted for small samples (AICc) with models having ΔAICc ≤ 2 being considered more parsimonious.

1 prec, mean daily precipitation; temp, mean daily temperature; srvy_eff, survey effort; dist_edge, distance to nearest forest edge; dist_tourist, distance to nearest tourist area; epi, number of epiphytes per tree; dist_urban, distance to nearest urban area; cbh, circumference of trees at breast height; lia, number of lianas per tree; dist_road, distance to nearest road; cover, per cent tree canopy cover; t_den, tree density.

Results

We obtained 19 records of Callithrix spp. in the Rio Doce State Park: four in the north (at 36 survey sites), one in the centre (31 sites) and six in the south (39 sites). Most observed groups were hybrids, with phenotypic traits between C. aurita and C. penicillata (Plate 1a) and some hybrids between C. penicillata and C. geoffroyi (Plate 1b). Only one individual exhibited pure C. aurita traits (Plate 1c), observed in a southern group alongside hybrids of both C. aurita × C. penicillata and C. penicillata × C. geoffroyi (Plate 1d). This group also contained hybrids of C. aurita × C. penicillata and C. penicillata × C. geoffroyi (Plate 1d). Because of the lack of non-hybrid groups, we combined all individual records in the N-mixture model analysis.

Plate 1 Callithrix species observed in Rio Doce State Park (Fig. 1). Hybrid individuals with phenotypic characters between (a) Callithrix aurita and Callithrix penicillata and (b) C. penicillata and Callithrix geoffroyi. (c) Individual with phenotypic characters of Callithrix aurita in (d) a group composed of hybrid individuals of C. aurita × C. penicillata (yellow arrow) and C. penicillata × C. geoffroyi (pink arrow); red arrow: C. aurita.

Abundance (λ) was negatively correlated with the distance to the nearest forest edge (Fig. 2a, Table 2). The average number of individuals/hexagon was 1.31 (range 0.01–5.00), with a total estimated abundance of 139 (95% CI 26.2–251.8) individuals, giving an estimated density of 0.12 ± SE 0.54 (95% CI 0.02–0.22) individuals/ha. We estimated there were c. 28 groups of Callithrix spp. across the surveyed area, with an estimated group size of five adults per hexagon (95% CI 0.67–9.33), similar to that reported in the literature for the genus Callithrix. Extrapolating to the entire Park (35,976 ha less 2,100 ha of lake), the estimated total abundance of Callithrix spp. could be 4,038 individuals across 808 groups. Detection probability (r) was positively correlated with daily precipitation (Fig. 2b; Table 2), with an average detection probability of 0.10 (95% CI 0.02–0.12).

Fig. 2 Effect of (a) distance to nearest forest edge on Callithrix species abundance, and (b) daily precipitation on the detection probability of Callithrix species, in Rio Doce State Park. Estimates and 95% CIs (denoted by dashed lines) were obtained from the most parsimonious model containing the variables.

Discussion

We estimated a higher density of marmosets in the Rio Doce State Park than previous studies (Stallings et al., Reference Stallings, Fonseca, Pinto, Aguiar and Sábato1991; Hirsch, Reference Hirsch1995), with a notably high density of hybrids. This suggests a significant decline in the native C. aurita population, and an increase in hybrid populations, especially in the southern region and expanding to central and northern areas of the Park.

The presence of C. geoffroyi and C. penicillata was first recorded in an earlier primate survey (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Vale, Alves, Mittermeier and Papavero1983). Subsequent studies confirmed their occurrence and the emergence of hybrids amongst the three Callithrix species (Coimbra-Filho, Reference Coimbra-Filho1984; Stallings et al., Reference Stallings, Fonseca, Pinto, Aguiar and Sábato1991; Hirsch, Reference Hirsch1995, Reference Hirsch2003; Hirsch et al., Reference Hirsch, Toledo, Brito and Rylands1996). Stallings et al. (Reference Stallings, Fonseca, Pinto, Aguiar and Sábato1991) reported marmoset hybrid densities of 0.47 individuals/km2 in secondary forests in the Park, and C. aurita densities of 0.02 individuals/km2 in secondary forests and 0.08 and 0.03 individuals/km2 in two areas of primary forest. Hirsch (Reference Hirsch1995) observed two marmoset groups with hybrids in the southern region: one group of six C. penicillata × C. aurita hybrids (0.031 and 0.054 individuals/ha, from two different observers), and a second group of five C. penicillata × C. geoffroyi hybrids. Hirsch (Reference Hirsch1995) also observed a group comprising 11 C. penicillata individuals (0.036 and 0.096 individuals/ha, from two different observers) and a group of six C. aurita individuals, in the same region of the Park. Given the Park’s proximity to wildlife trafficking routes, C. geoffroyi and C. penicillata may have been released by environmental agencies after animals were rescued from wildlife traffickers (Silva, Reference Silva2014; Loureiro et al., Reference Loureiro, Damo and Rodrigues2019).

The presence of mixed hybrid groups in the Park highlights the risks to native C. aurita from the spread of introduced C. geoffroyi and C. penicillata. Phenotypic analyses suggest there has been genetic erosion of the native C. aurita population, facilitating hybridization, backcrossing and introgression, posing a major threat to the genetic integrity of C. aurita (Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Bergallo, Cronemberger, Guimarães-Luiz, Souza and Jerusalinsky2018, Reference Carvalho, Fransen, Valença-Montenegro, Dunn, Igayara-Souza, Port-Carvalho, Schwitzer, Mittermeier, Rylands, Chiozza, Williamson and Byler2019). Most of the marmoset groups observed in our study consisted solely of hybrids, indicating historical hybridization without recent genetic input from the parental species (Coimbra-Filho et al., Reference Coimbra-Filho, Pissinati and Rylands1993; Malukiewicz et al., Reference Malukiewicz, Boere, Fuzessy, Grativol, Silva and Pereira2015). However, the presence of groups containing both hybrid and non-hybrid individuals would suggest more recent formation, particularly when native parents are nearby (Pereira, Reference Pereira2010). The discovery of a C. aurita individual in a hybrid group in our study indicates that this may occasionally be the case in the Rio Doce State Park (Plate 1d). Our opportunistic observation (outside our survey) of a group of C. aurita confirms the presence of the native species at low density compared to the invasive species, underscoring the urgent need to conserve these remaining populations.

Of the environmental variables we considered, distance to the nearest forest edge was negatively correlated with Callithrix spp. abundance. It is well known that Callithrix species are adaptable and prefer secondary-growth forest at various stages of succession as well as edge habitats (Rylands, Reference Rylands1982, Reference Rylands1996; Stevenson & Rylands, Reference Stevenson, Rylands, Mittermeier, Rylands, Coimbra-Filho and da Fonseca1988; Rylands & Faria, Reference Rylands, Faria and Rylands1993). These habitats feature dense vegetation with tangles of lianas and/or bamboo, providing shelter and cover from predators (Olmos & Martuscelli, Reference Olmos and Martuscelli1995; Rylands, Reference Rylands1996; Norris et al., Reference Norris, Rocha-Mendes, Marques, Nobre and Galetti2011). Secondary forests and forest edges also provide an abundance of prey, facilitate movement and support fewer potential competitors, particularly other primates (Rylands, Reference Rylands1989, Reference Rylands1996; Rylands & Faria, Reference Rylands, Faria and Rylands1993; Goldizen et al., Reference Goldizen, Mendelson, Van Vlaardingen and Terborgh1996; Raboy & Dietz, Reference Raboy and Dietz2004). However, C. aurita is less of a generalist and tends to inhabit areas farther from human influence (for example in the Serra dos Órgãos National Park), whereas invasive species are more common near forest edges (Detogne et al., Reference Detogne, Ferreguetti, Mello, Santana, Dias and Mota2017), highlighting their ecological flexibility.

None of the other environmental variables influenced Callithrix abundance, most probably because of the ecological flexibility shown by marmosets (Vilela & Faria, Reference Vilela and Faria2004; Sales et al., Reference Sales, Hayward and Passamani2016; Grande et al., Reference Grande, Alencar, Ribeiro and Melo2020). Likewise, anthropogenic variables (distance to nearest tourist areas, urban areas and roads) had no discernible effect. However, logistical constraints, including access difficulties, resource limitations and weather conditions, limited surveys in some locations. Therefore, we recommend that future studies should focus on diverse and more remote sites, to better assess the influence of these variables.

Contrary to our expectations, marmosets were more frequently detected during periods of higher daily precipitation, despite low (maximum 1.9 mm) and relatively stable daily precipitation throughout the survey period. The higher detection rates could be related to increased atmospheric humidity on rainy days (Côrrea, Reference Côrrea1995) resulting in greater insect abundance (Janzen, Reference Janzen1973), which could increase marmoset foraging activity and detectability.

Overall, detection probability was low, most probably as a result of the scarcity of fruit and insects during our survey period in the dry season. During periods of resource shortage, marmosets tend to increase their foraging activity over greater areas (Passamani & Rylands, Reference Passamani and Rylands2000; Ferrari & Hilário, Reference Ferrari and Hilário2014), which may reduce their visibility and impact their responsiveness to playback sessions. In contrast, Hilário et al. (Reference Hilário, Silvestre, Abreu, Beltrão-Mendes, de Castro and Chagas2022) presented evidence that higher temperatures, especially during the rainy season, reduce marmoset activity, with more time spent resting and less time spent exploring. Consequently, the chances of detection may be greater during these times, as they may stay in their territory core area.

Detection of marmosets may have been negatively affected by practical constraints in our study. For example, the dense understorey at some sampling points may have hindered playback sound propagation (Soares et al., Reference Soares, Santos, Beltrão-Mendes and Ferrari2011), and the irregular terrain may have hindered the visual identification of individuals, especially any that were present but did not respond to playback. Previous studies in this area also reported low marmoset detection (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Vale, Alves, Mittermeier and Papavero1983; Stallings et al., Reference Stallings, Fonseca, Pinto, Aguiar and Sábato1991; Hirsch, Reference Hirsch1995). Despite the Park being one of the few protected areas with high primate diversity in the state, primates are observed infrequently except for the black-horned capuchin S. nigritus. It is possible that increasing the playback and search time could improve detection and yield more accurate abundance estimates.

Given the severe consequences of biological invasions for C. aurita and its low occurrence in Rio Doce State Park, we recommend strengthening conservation efforts by integrating measures into the National Action Plan for the Conservation of Atlantic Forest Primates and the Maned Sloth (ICMBio/MMA, 2018). Managing the C. aurita population, including translocation to conservation breeding centres, is crucial for safeguarding genetic diversity and increasing ex situ population viability (ICMBio/MMA, 2018). It is also vital that genetic analyses of Callithrix individuals in the Park are used to inform effective management actions for hybrids, such as control, eradication or protection. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of protecting hybrids with up to 50% of the genome of a threatened native species, to enhance the gene pool in offspring, even in inter-crossing cases (Wayne & Shaffer, Reference Wayne and Shaffer2016; Nogueira et al., Reference Nogueira, de Carvalho, de Oliveira, de Paula, Pereira and Pissinatti2022). Each hybridization case is unique and conservation guidelines must be formulated carefully to incorporate ecological and evolutionary processes (Wayne & Shaffer, Reference Wayne and Shaffer2016). Population assessments in other areas across the Park are also needed to establish the total population size of C. aurita. Incorporating innovative technology, such as drones and thermal imaging, could aid in surveying marmosets in remote areas. In addition, similar surveys of the surrounding forest fragments are necessary as they may be acting as refuges for other species that then move into the Park. Environmental education and training for personnel working to combat illegal trafficking of primates is also important, to prevent inappropriate releases of allochthonous marmosets (ICMBio/MMA, 2018).

This study used the playback method combined with N-mixture models to estimate the abundance and detection probability of marmosets, proving it to be effective for acoustically responsive species. Our findings could be applied to other protected areas where native species are facing similar challenges from biological invasions and hybridization. We hope this will contribute to the conservation of threatened species, in particular the buffy-headed marmoset C. flaviceps.

Author contributions

Study design: all authors; data collection: VPGL, NGL, JSD; analysis, writing: VPGL; revision: all authors.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Rio Doce State Park team and everyone who contributed to this research. This study was financed by The Rufford Foundation, Re:wild, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The research was conducted under the authorization of the Animal Use Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (permit 256/2018), of the Minas Gerais State Forest Institute (permit 090/2018) and the Biodiversity Information and Authorization System of the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation and the Brazilian Ministry of the Environment (permit 59562-1). The research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.

Data availability

The data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.