Introduction

Cephalopod prey play a crucial role in many trophic webs and is consumed in tonnes (Clarke, Reference Clarke1996) despite the fact that cephalopods are much less diverse than finfish and crustaceans. It should be noted that there are about 70 species of cephalopods in the Mediterranean (of which 57 are autochthonous and 13 are suspected to be non-indigenous; Bello et al., Reference Bello, Andaloro and Battaglia2020) compared with 650 species of finfish and 2251 of crustaceans (Coll et al., Reference Coll, Piroddi, Steenbeek, Kaschner, Ben Rais Lasram, Aguzzi, Ballesteros, Bianchi, Corbera, Dailianis, Danovaro, Estrada, Froglia, Galil, Gasol, Gertwagen, Gil, Guilhaumon, Kesner-Reyes, Kitsos, Koukouras, Lampadariou, Laxamana, De La Cuadra CM, Lotze, Martín, Mouillot, Oro, Raicevich, Rius-Barile, Sáiz-Salinas, San Vicente, Somot, Templado, Turón, Vafidis, Villanueva and Voultsiadou2010). This may indicate the abundance and high biodiversity of cephalopod communities, as in other North-eastern Atlantic places (Bay of Biscay, North Sea, or Irish Sea; Lordan et al., Reference Lordan, Warnes, Cross and Burnell1996; Oesterwind et al., Reference Oesterwind, Hofstede, Harley, Brendelberger and Piatkowski2010; Velasco et al., Reference Velasco, Olaso and Sánchez2001). Furthermore, some large predators became specialised in a strictly or predominantly teuthivorous or teuthofagous diet, such as the cosmopolitan Risso’s dolphin, Grampus griseus (G. Cuvier, 1812) (Hartman, Reference Hartman, Würsig, Jgm and Kovacs2018; Luna et al., Reference Luna, Sánchez, Chicote and Gazo2022). Both oceanic and demersal cephalopods are widely preyed upon in all oceans, although the former appear to attain a biomass-wise predominant role in marine food webs with respect to the latter (Clarke, Reference Clarke1996). From this standpoint, oceanic ones can be considered ubiquitous prey items (Boyle and Rodhouse, Reference Boyle and Rodhouse2005).

Cephalopods play a key role in the world’s marine ecosystems (Boyle and Rodhouse, Reference Boyle and Rodhouse2005). Large cephalopods (Taningia danae Joubin, 1931, Nototeuthis dimegacotyle Nesis & Nikitina, 1986 – Navarro et al., Reference Navarro, Coll, Somes and Olson2013 – and Gonatus J. E. Gray, 1849 in Arctic waters – Golikov et al., Reference Golikov, Ceia, Hoving, Queirós, Sabirov, Blicher, Larionova, Walkusz, Zakharov and Xavier2022, Reference Golikov, Ceia, Sabirov, Zaripova, Blicher, Zakharov and Xavier2018) have isotopic values that are similar to those of sperm whales or some dolphins in the same oceanic area (Das et al., Reference Das, Lepoint, Leroy and Bouquegneau2003, Reference Das, Lepoint, Loizeau, Debacker, Dauby and Bouquegneau2000), acting as top predators in some systems, preying on large fishes and other cephalopods. They are important consumers (Clarke, Reference Clarke1996), and oceanic squids in particular are valuable prey items for many top marine predators such as large bony fishes, sharks, marine mammals, and seabirds (Clarke, Reference Clarke1996; Croxall, Prince and Clarke, Reference Croxall, Prince and Clarke1996; Klages and Clarke, Reference Klages and Clarke1996; Smale and Clarke, Reference Smale and Clarke1996). Octopuses, however, are voracious mesopredators that play a key role in coastal marine food webs, thanks to their ability to adapt well to a dynamic, constantly changing environment with an abundance of prey types (Lankow, Reference Lankow2022). In addition, cephalopods are fast-growing animals that optimise their food intake energy-wise and, in turn, act as efficient energy transmitters in food webs from bottom feeders to large predators (Amaratunga, Reference Amaratunga1983).

The examination of cephalopods ingested by predators provides information not only about the predators themselves (e.g., biology, biomass, population composition, size-frequency), but also about their feeding habits (Villanueva et al., Reference Villanueva, Perricone and Fiorito2017), habitats and ecological niches (Roscian et al., Reference Roscian, Herrel, Zaharias, Cornette, Fernández, Kruta, Cherel and Rouget2022), and their phylogenetic and ecological drivers (Sánchez-Márquez et al., Reference Sánchez-Márquez, Navarro, Kaliontzopoulou, Farré, Taite, Escolar, Villanueva, Allcock and Fernández-Álvarez2022). Currently, dietary studies, combined with stable isotope techniques, allow the trophic position of specimens to be inferred, opening up a wide range of new possibilities in ecological, biogeographical, fisheries and environmental studies (Xavier et al., Reference Xavier, Golikov, Queirós, Perales-Raya, Rosas-Luis, Abreu, Bello, Bustamante, Capaz, Dimkovikj, González, Guímaro, Guerra-Marrero, Gomes-Pereira, Kubodera, Laptikhovsky, Lefkaditou, Lishchenko, Luna, Liu, Pierce, Pissarra, Reveillac, Romanov, Rosa, Roscian, Rose-Mann, Rouget, Sánchez, Sánchez-Márquez, Seixas, Souquet, Varela, Vidal and Cherel2022).

The purpose of this paper is to review the available information on the dietary preferences and feeding behaviour of teuthivorous predators in the Mediterranean Sea. We present this article at a regional rather than a global level for one main reason: historically, in the Mediterranean important studies on the diet of different predators have been carried out. Besides, a global approach would obviously be extremely difficult to accomplish. This work opens a window on a very important aspect, not only in terms of knowledge of the relationships in the ecological web between predators and prey cephalopods, but also in filling a gap that fisheries data cannot provide, data that can be used in the management of marine resources. They also provide information on the feeding strategies and behaviour of many species, highlighting where possible the presence of alien species. We focus on the Mediterranean as a case study, approached from a selection of Mediterranean teuthivorous predators, because the world literature on cephalopods as predators and prey is quite extensive.

Materials and methods

The literature relating to the diet of marine predators in the entire Mediterranean Sea was reviewed. We have tried to include as many studies as possible on the diets of these Mediterranean teutophagous species. The specific criterion used for the bibliographic searches is to find out which teuthivorous predators are present in the Mediterranean and what prey species they eat. The keywords used were ‘diet’, ‘feeding’, ‘teutophagous predators’, ‘teuthivorous predators’, ‘teuthivores predators’, ‘cephalopods diet’, ‘cephalopods feeding’, ‘Mediterranean’, and the names (scientific and common) of the different predators (Supplementary Table S1). The following search engines, bibliographic repositories, and platforms were used to search specific databases: PROA (ICM-CSIC), University of Vigo’s Interlibrary Loan Service, Google Academic and Web of Science. The search was conducted in 2024, in several languages (English, Italian, Spanish and French). Due to the paucity of data in the articles on this topic, none were excluded from the results. There is therefore a significant collection of articles here, many of which are not indexed in electronic bibliographic search engines. We want to provide an outlet for these articles so that the information they contain, which is very valuable for dietary studies, is captured. Many of the papers reviewed do not have standardised data because they are old or grey literature, and some of them do not follow standards in data collection. Older publications do not have all the information needed for this type of work. For example, some of them lack biomass, so in some cases they only have frequency data (Bello, Reference Bello1985; Bingel and Avsar, Reference Bingel and Avsar1988; Würtz and Palumbo, Reference Würtz and Palumbo1985). So, to make this information available at a glance, we have focused on the most important predators in terms of abundance in the area, number of studies focusing on them and type of feeding habits, giving priority to predators that are considered to be mainly teuthivorous. All available data were extracted from them to carry out the analyses. Of these papers, 120 were found to relate to cephalopod predators (Supplementary material).

Statistical techniques were used to investigate trends in the diet of these predators. A matrix of the presence and absence of cephalopod predators and their prey was constructed. Neither the percentage of occurrence nor the biomass (in terms of number and/or weight of prey) of ingested cephalopods was reported, as such data are only partially available and, in many cases, difficult to compare. We used PRIMER statistical software to perform multivariate analyses on prey species data (Clarke and Warwick, Reference Clarke and Warwick1994). Cluster analysis was performed on the presence/absence data using the normalised Euclidean distance index, and dendrograms were constructed using the group-average clustering method. The resulting similarity matrices were then used to perform non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS). To make the results clearer, only predators with more than 12 different cephalopod prey items in their stomachs were included in this latter analysis.

To confirm the literature findings, the distribution of prey and predators was compared to see if the identified cephalopods had the same distribution as the identified teuthivorous predators (see Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Only species distributions are shown, as there may be different distribution patterns within the same family or genus, which would add uncertainty to the discussion of these results. Species distributions have been extracted from WoRMS Editorial Board (2025), except in certain specified cases as for the distribution of bony fishes, where the work of Hureau and Monod (Reference Hureau and Monod1979) has been followed, or for cephalopods, where FAO volumes have generally been followed (Jereb and Roper, Reference Jereb and Roper2005, Reference Jereb and Roper2010; Jereb et al., Reference Jereb, Roper, Norman and Finn2016 (see Table 1). Information on the feeding behaviour of selected predators throughout the Mediterranean, inferred from their prey cephalopods, is also reported in the discussion (e.g., Bello, Reference Bello1994; Bello and Biagi, Reference Bello and Biagi1995; among others).

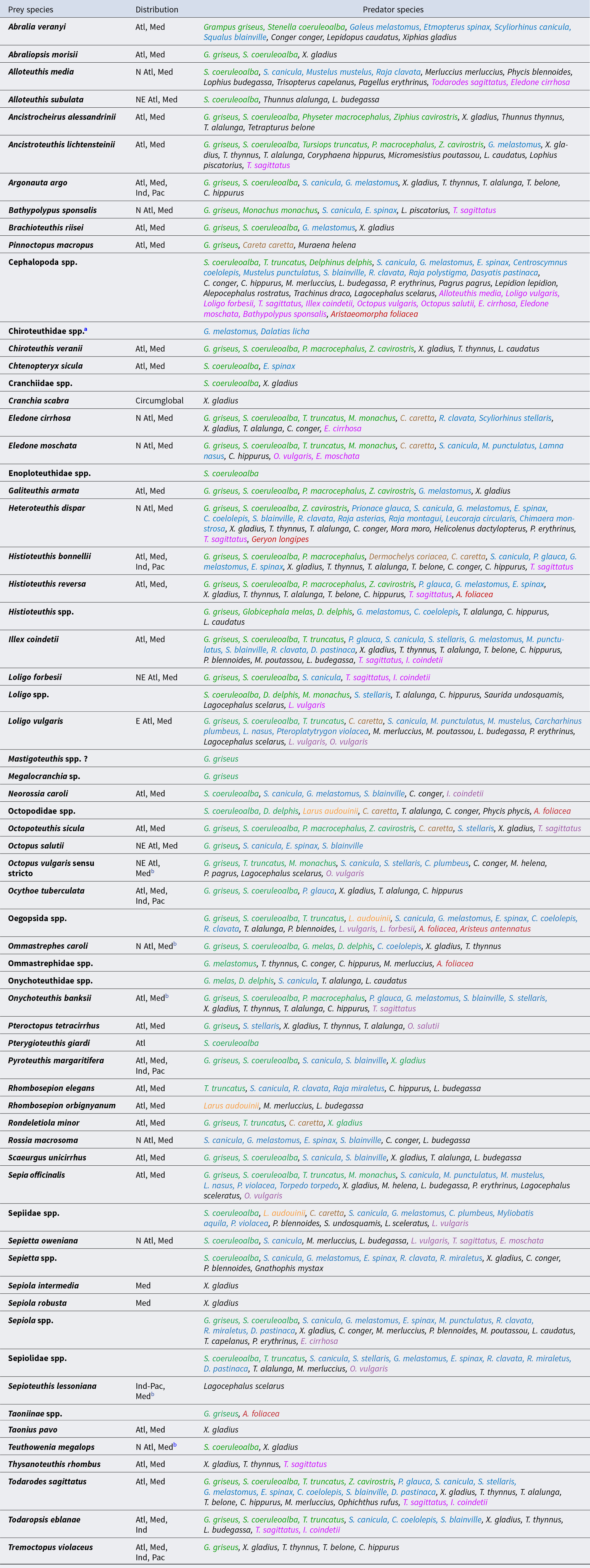

Table 1. Cephalopods identified in the predators’ stomachs in the literature (see Supplementary Table S1)

For the prey species distribution, some abbreviations have been used. Atl: Atlantic, Med: Mediterranean, N Atl: North Atlantic, NE Atl: North-east Atlantic, S Afr: South Africa, Ind: Indian, Pac: Pacific.

aSince the only chiroteuthid species known to live in the Mediterranean is Chiroteuthis veranii, records of Chiroteuthidae spp. most likely refer to this species. Colour code: ![]() (black),

(black), ![]() (blue),

(blue), ![]() (green),

(green), ![]() (orange),

(orange), ![]() (brown),

(brown), ![]() (red) and

(red) and ![]() (purple).

(purple).

bDistribution extracted from FAO volumes (Jereb and Roper, Reference Jereb and Roper2005, Reference Jereb and Roper2010; Jereb et al., Reference Jereb, Roper, Norman and Finn2016). For Teuthowenia megalops, from Sánchez, Reference Sánchez1985; Santos et al., Reference Santos, Pierce, Herman, López, Guerra, Mente and Clarke2001; Bello et al., Reference Bello, Andaloro and Battaglia2020; for Sepioteuthis lessoniana from Salman (Reference Salman2002); for Octopus vulgaris sensu stricto, from Amor et al. (Reference Amor, Norman, Á, Leite, Gleadall, Reid, Perales-Raya, Ch, Silvey, Vidal, Hochberg, Zheng and Strugnell2017); for Loligo forbesii from Riad (Reference Riad2020); for Ommastrephes caroli, from Fernández-Álvarez et al. (Reference Fernández-Álvarez, Braid, Nigmatullin, Bolstad, Haimovici, Sánchez, Sajikumar, Ragesh and Villanueva2020); for Eledone moschata, from Luna et al. (Reference Luna, Rocha and Perales-Raya2021); for Chtenopteryx sicula from Fernández-Álvarez et al. (Reference Fernández-Álvarez, Sánchez, Deville, Taite, Villanueva and Allcock2023); for Thysanoteuthis rhombus from Deville et al. (Reference Deville, Mori, Kawai, Escánez, Macali, Lishchenko, Braid, Githaiga-Mwicigi, Mohamed, Bolstad, Miyahara, Sugimoto, Fernández-Álvarez and Sánchez2024); for Ancistrocheirus alessandrinii from Arnold et al. (Reference Arnold, Nos, Sáez-Liante and Fernández-Álvarez2025).

Results

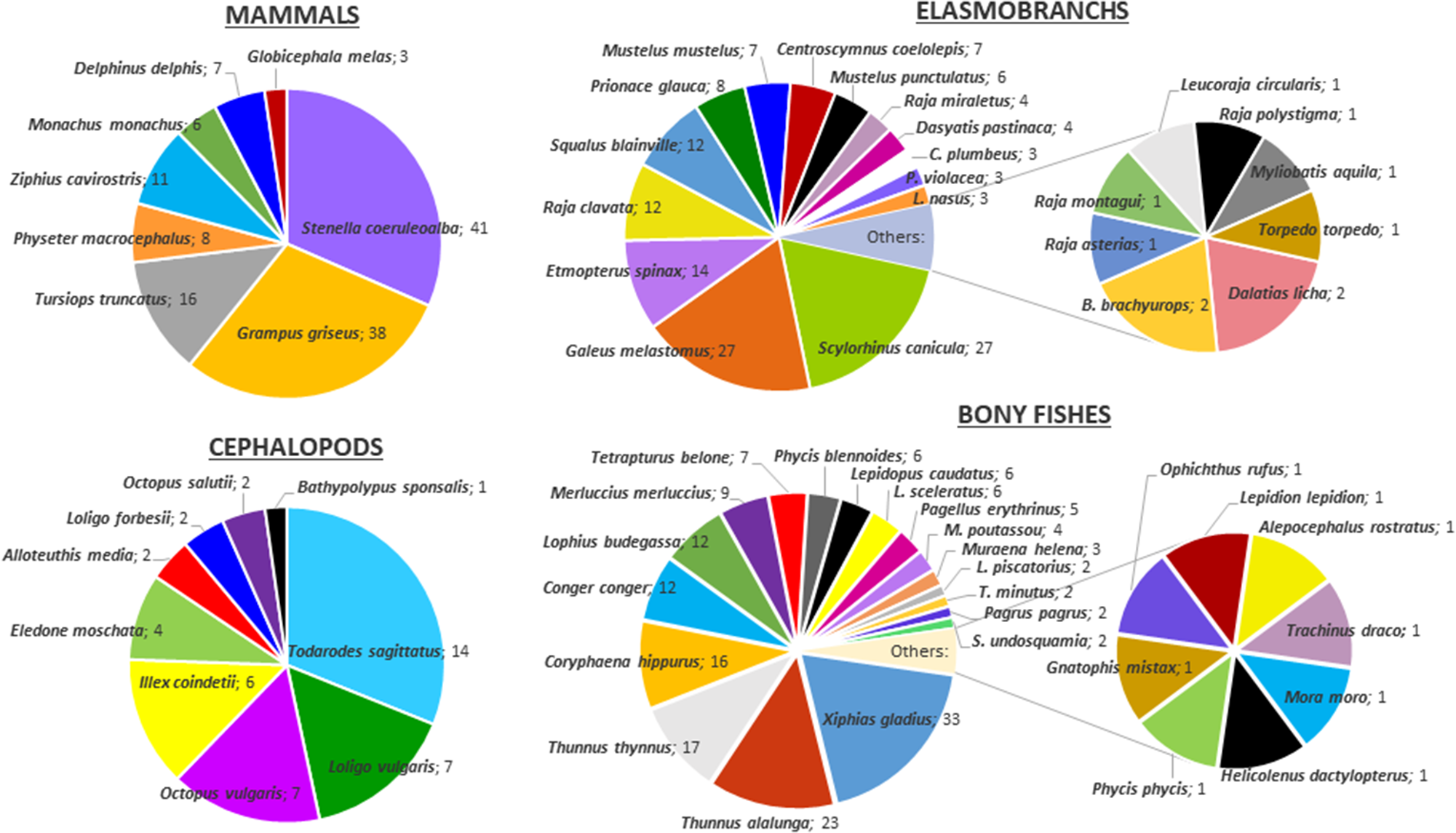

In the Mediterranean Sea, eight marine mammals, two turtles, 23 chondrichthyans, two birds, 26 bony fishes, nine cephalopods and three crustaceans have been reported as consumers of cephalopods (Figure 1). This does not mean that there are no other cephalopod predators, just that they are not yet known or studied. The results show the most important teuthivorous only in terms of prey variety (i.e., not in terms of quantity). For the same reason, it is not possible to determine which is the most abundant prey in terms of quantity, but only in terms of frequency of occurrence. According to the literature consulted, at least 46 different cephalopod species have been identified among the remains recovered from the digestive tracts of predators. Other remains could only be assigned to taxa above the species level, i.e., seven to the genus level, seven to the family level and two to the order level; some others could only be assigned to the class Cephalopoda (Table 1).

Figure 1. Pie diagram of the different groups of cephalopod predators, showing the number of prey species of each of them.

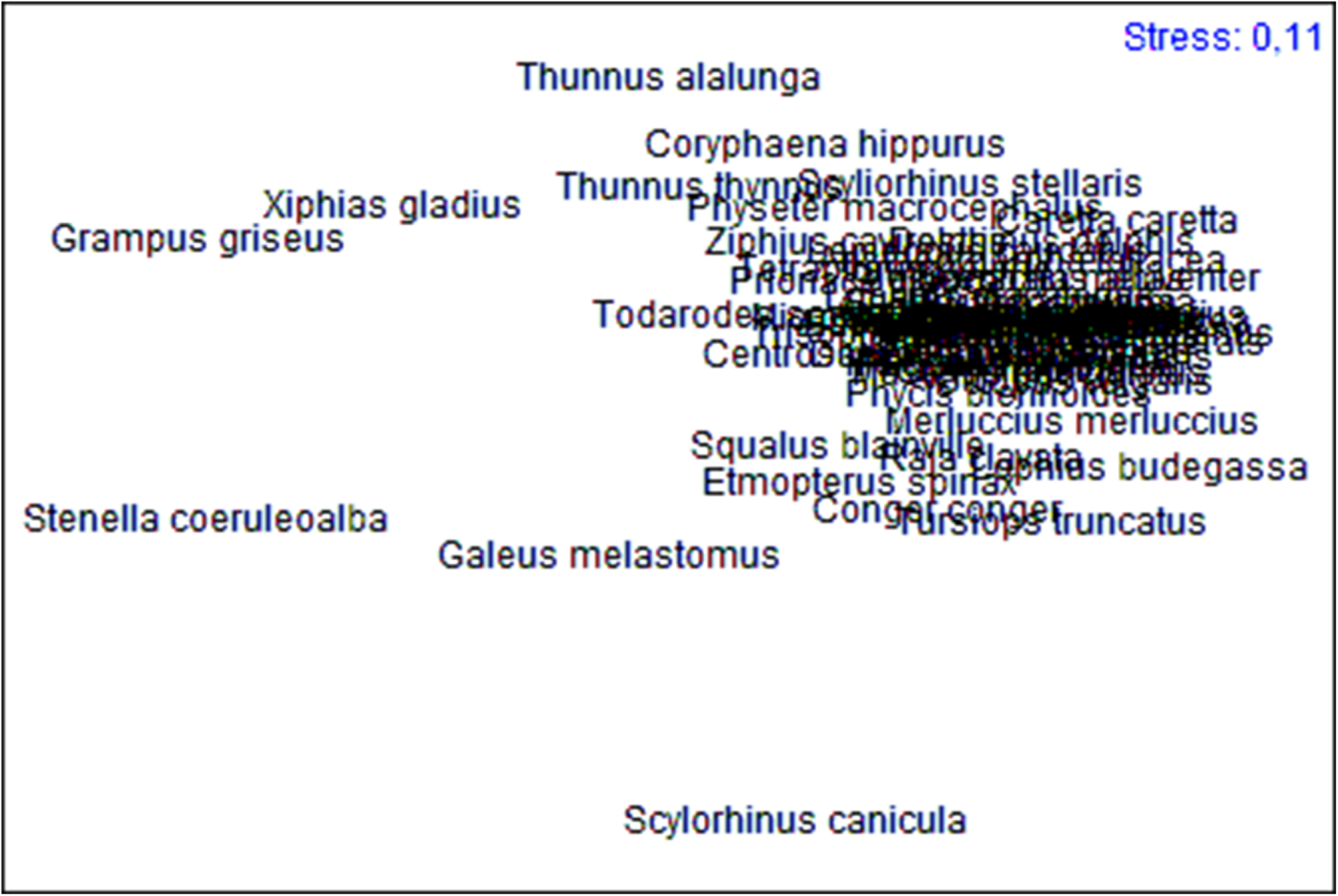

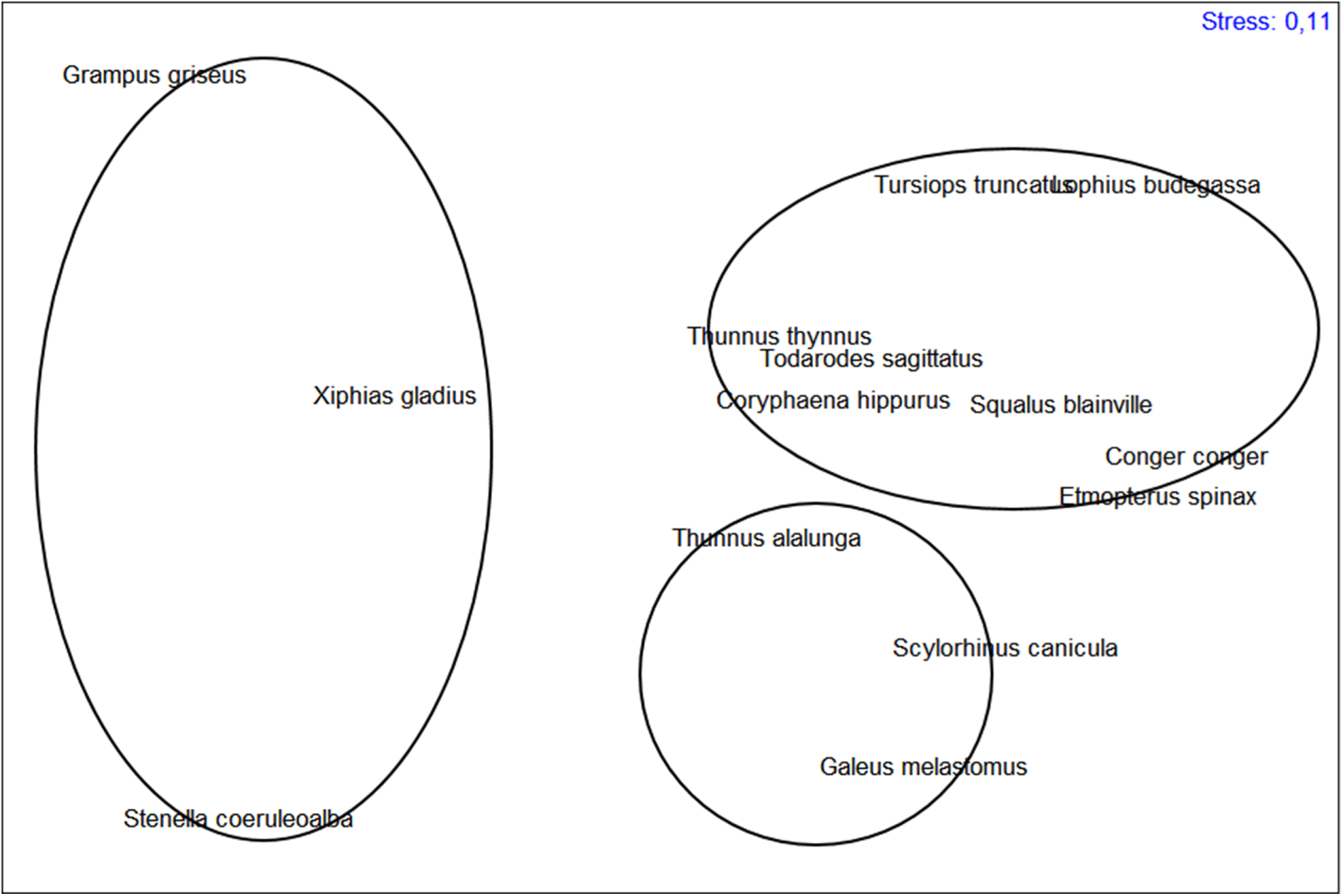

The results of the cluster analysis and the nMDS (Figure 2) do not show the occurrence of defined groups of predator species, except for the separation of Stenella coeruleoalba (Meyen, 1833), G. griseus and Xiphias gladius Linnaeus, 1758 with respect to the other species. In the case of nMDS, in addition to the three species mentioned above, a group of species slightly separated from the main cluster is observed. The nMDS (Figure 3) allows three groups of large cephalopod predators to be distinguished. One is clearly formed by the largest cephalopod consumers, in terms of diversity of consumed prey: S. coeruleoalba, G. griseus and X. gladius. Of the 65 prey items identified, S. coeruleoalba consumed 68.9% of the total number of possible prey items, and G. griseus and X. gladius 62.3%. The next group is made up of Scyliorhinus canicula (Linnaeus, 1758) (which consumed 44.3% of the possible prey items), Galeus melastomus Rafinesque, 1810 (37.7%) and Thunnus alalunga (Bonnaterre, 1788) (32.8%). The third group is formed by Thunnus thynnus (Linnaeus, 1758) and Tursiops truncatus (Montagu, 1821) (both consumed 26.2%), Coryphaena hippurus Linnaeus, 1758 (24.6%), Etmopterus spinax (Linnaeus, 1758) and Todarodes sagittatus (Lamarck, 1798) (both with 23.0%), followed by Squalus blainville (Risso, 1827), Lophius budegassa Spinola, 1807 and Conger conger (Linnaeus, 1758), which consumed 19.7% of the total documented prey species.

Figure 2. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS) representation of cephalopod predators in the Mediterranean Sea.

Figure 3. nMDS representation of the three assemblages identified among the principal of cephalopod predators.

When analysing prey cephalopods, Table 1 shows that Heteroteuthis dispar (Rüppell, 1844) and Illex coindetii (Vérany, 1839) are the most frequent prey of different predators (23 and 21, respectively). Todarodes sagittatus is also very frequent (found in 20 predators). The large occurrence of ‘unidentified Cephalopoda’, the category with the highest frequency of occurrence as prey species for so many different predators (32), is largely due to the fact that in many cases, cephalopod remains from the predators’ stomach contents are represented only by fragments of beaks or eye lenses, preventing any identification below the class level. This category is not directly comparable with the individual species listed in Table 1, as it most likely includes several species.

Comparing the distribution of prey and predators reveals that of the 73 predators studied, 39.7% have a global or wide distribution. It is the case of the seven cetaceans Delphinus delphis Linnaeus, 1758, Globicephala melas (Traill, 1809), G. griseus, Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758, T. truncatus, S. coeruleoalba and Ziphius cavirostris Cuvier, 1823 (Boldrocchi et al., Reference Boldrocchi, Conte, Galli, Bettinetti and Valsecchi2024; WoRMS Editorial Board, 2025); six chondrichthyans Lamna nasus (Bonnaterre, 1788), Prionace glauca (Linnaeus, 1758), Pteroplatytrygon violacea (Bonaparte, 1832), Carcharhinus plumbeus (Nardo, 1827), Centroscymnus coelolepis Barbosa du Bocage and de Brito Capello, 1864 and Dalatias licha (formerly Scymnorhinus licha [Bonnaterre, 1788]); three osteichthyans, C. hippurus, T. alalunga, T. thynnus and X. gladius; the giant red shrimp (Aristaeomorpha foliacea (Risso, 1827)); and the sea turtles Dermochelys coriacea (Vandelli, 1761) and Caretta caretta (Linnaeus, 1758).

53,4% of the predators have an Atlantic distribution, including the Mediterranean Sea. This is the case of the crustaceans Aristeus antennatus (Risso, 1816) and Geryon longipes A. Milne-Edwards, 1882, the chondrichthyans S. blainville (although this species appears to be a species complex; Ebert and Stehman, Reference Ebert and Stehman2013), and G. melastomus, or the osteichthyans Helicolenus dactylopterus (Delaroche, 1809), Merluccius merluccius (Linnaeus, 1758), Micromesistius poutassou (Risso, 1827), Mora moro (Risso, 1810), the monk seal (Monachus monachus [Hermann, 1779]), the common eagle ray (Myliobatis Aquila [Linnaeus, 1758]), Dasyatis pastinaca (Linnaeus, 1758) and most cephalopod predators (Alloteuthis media [Linnaeus, 1758]), Bathypolypus sponsalis (Fischer and Fischer, 1892), I. coindetii, Loligo vulgaris (Lamarck, 1798), Octopus salutii (Vérany, 1839), Octopus vulgaris sensu stricto (Cuvier, 1797), and T. sagittatus. There are three endemic Mediterranean predators (4.1% of species: Raja polystigma [Regan, 1923], Tetrapturus belone [Rafinesque, 1810], and Trisopterus capelanus [Lacepède, 1800]; WoRMS Editorial Board, 2025). Two are invasive Lessepsian species and one anti-Lessepsian species. The Lessepsian species, one of which is Lagocephalus sceleratus (Gmelin, 1789), occurs in the western Pacific and Indian Oceans (from where it entered the Mediterranean through the Suez Canal). Another one is Saurida undosquamis (Richardson, 1848), which Inoue and Nakabo (Reference Inoue and Nakabo2006) consider to be a group of species. One of these must have been introduced into the Mediterranean from the Red Sea, as it has been found on the coasts of Israel and Turkey (Bilecenoğlu et al., Reference Bilecenoğlu, Kaya, Cihangir and Çiçek2014). The anti-Lessepsian species is Muraena helena Linnaeus, 1758, expanded from the Mediterranean Sea to the Indian Ocean.

Discussion

The overall faunal picture provided by cephalopod predators is quite different from that provided by fisheries. Small-sized species such as H. dispar, which rarely appear in trawl catches, are abundant in the diet of teuthivorous predators (P.S. pers. obs.). Likewise, deep-sea pelagic species such as Histioteuthis spp. appear to be common prey for large predators (Clarke, Reference Clarke1996) (see Table 1).

Currently, researchers conducting studies on the diet of teuthivorous are finding gaps in knowledge that have already been studied and cannot be found on the internet. As researchers in this field, we know how valuable it is to find a paper with the information you need (species present in the diet of a particular predator, or a morphometric equation for a particular species), in addition to the time it can save. The study of predators’ diets using a purely morphological approach, i.e., identification of gut contents based on visual assessment, is generally rejected by researchers because it is time-consuming and requires high taxonomic skills. As a result, the number of researchers working in this area, which provides very valuable biological and ecological information, is decreasing. This purpose will be fulfilled by examining the prey cephalopods for seabirds, fish, marine mammals and other predators. This compilation can be very useful for future authors studying trophic relationships, especially due to the difficulty of finding some of the papers reviewed.

Of the 70 cephalopod species reported in the Mediterranean by Bello et al. (Reference Bello, Andaloro and Battaglia2020), only 48 have been identified in the digestive tract of predators. For instance, 11 Sepiolida have not been reported in their stomachs, eight of them belonging to the genus Sepiola Leach, 1817, two to the genus Sepietta Naef, 1912 and the species Stoloteuthis cthulhui Fernández-Álvarez et al. (Reference Fernández-Álvarez, Sánchez and Villanueva2021) (to the establishment of this new species, all previous records of S. leucoptera in the Mediterranean would correspond to S. cthulhui [Fernández-Álvarez et al., Reference Fernández-Álvarez, Sánchez and Villanueva2021]). Some of them are possibly included in the category ‘Sepiolidae’.

Several species considered to be non-indigenous species (NIS) have been recorded in the Mediterranean Sea, some of them coming from the Atlantic Ocean via the Strait of Gibraltar and others from the Red Sea via the Suez Canal (Bello et al., Reference Bello, Andaloro and Battaglia2020). There are several plausible hypotheses as to why these species are present in the Mediterranean, and these hypotheses are not mutually exclusive. 1) Given the short time that has elapsed since the introduction of most of them, their populations are still rather small, which may explain why only one of them, Taonius pavo (Lesueur, 1821), has been reported in very few predators’ gastric remains, i.e., G. griseus (Luna et al., Reference Luna, Sánchez, Chicote and Gazo2022) and a juvenile X. gladius (Fernández-Corredor et al., Reference Fernández-Corredor, Francotte, Martino, FÁ, García-Barcelona, Macías, Coll, Ramírez, Navarro and Giménez2023). Of particular relevance is Sepioteuthis lessoniana R. P. Lesson, 1831, which has been reported in the stomach contents of L. sceleratus, both species being Lessepsian migrants (Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Christidis, Peristeraki, Somarakis and Tserpes2025). In this regard, Clarke (Reference Clarke1980) cautioned against inferring geographic distributions of prey species based on their occurrence in the stomach contents of predators capable of swimming long distances in short periods of time. This is the case with sperm whales, which can reach places far from their feeding grounds in a matter of days. Their stomachs could therefore contain beaks of squid that do not live in the area where the prey died. This could be the case for predators with a global distribution (such as D. delphis, P. glauca, or T. alalunga) or with a wide distribution (such as C. plumbeus, T. thynnus, or C. caretta). This point has already been widely discussed. There is no doubt that species with this type of distribution raise doubts (‘Is this species from the Pacific or the Mediterranean?’), but the valuable information provided by the collection of beaks of different predators cannot be ignored. In this sense, the works that relate the erosion of the beaks to the time that the beaks remain in the stomach can be useful in determining the rate of digestion (Van Heezik and Seddon, Reference Van Heezik and Seddon1989; Xavier et al., Reference Xavier, Clarke, Magalhães, Stowasser, Blanco and Cherel2007, Reference Xavier, Golikov, Queirós, Perales-Raya, Rosas-Luis, Abreu, Bello, Bustamante, Capaz, Dimkovikj, González, Guímaro, Guerra-Marrero, Gomes-Pereira, Kubodera, Laptikhovsky, Lefkaditou, Lishchenko, Luna, Liu, Pierce, Pissarra, Reveillac, Romanov, Rosa, Roscian, Rose-Mann, Rouget, Sánchez, Sánchez-Márquez, Seixas, Souquet, Varela, Vidal and Cherel2022), as well as the works on the erosion of the tips of the beaks during the feeding process (Perales-Raya et al., Reference Perales-Raya, Bartolomé, Hernández-Rodríguez, Carrillo, Martín and Fraile-Nuez2020). There is a lack of studies in this direction, and they would be very useful in determining the time the beaks spend in the stomach. It would be possible to deduce whether the prey was recently ingested or not. The mobility of the predator is also important, since a species with a limited distribution, such as a shrimp, is not the same as a species with a wide range of movements, such as a cetacean. Relevant here is the work of Whitehead et al. (Reference Whitehead, Macleod and Rodhouse2003), who analysed the differences in niche breadth of some cetaceans, pointing out that some prey species may be less likely to accumulate in the stomach, and that the prey of the prey may be inadvertently included in the diet (Clarke, Reference Clarke1980; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Paliza and Aguayo1988). 2) It is possible that the NIS has been overestimated. These species may have been present in the Mediterranean earlier than reported, but they would not have been found in this area until recently. This could reflect a sampling bias. For example, this could be because a species’ sampling area was not sampled, or not sampled at sufficient depth in the case of deep-sea species (Zaragoza et al., Reference Zaragoza, Quetglas, Hidalgo, Álvarez-Berastegui, Balbín and Alemany2015, who found a clear difference in the species composition of shallow-water and deeper-water cephalopod paralarvae in the Balearic Mediterranean). There are many other possible causes, such as sudden demographic explosions of rare species considered NIS in the area (finding unexploited or underexploited ecological niches, or the absence of predators). However, this would mean that they would be found in abundance in surveys during the bloom (e.g., blue crab in many Mediterranean locations; Marchessaux et al., Reference Marchessaux, Mangano, Bizzarri, M’rabet, Principato, Lago, Veyssiere, Garrido, Scyphers and Sarà2023). 3) Species rarely caught in Atlantic waters (e.g., Cranchia scabra Leach, 1817, T. pavo, Megalocranchia spp., Teuthowenia megalops (Prosch, 1849), Cycloteuthis sirventi Joubin, 1919, T. danae) could just be scarce, with the added difficulty of sampling bias (Bello, Reference Bello2003; Quetglas et al., Reference Quetglas, Ordines, González, Zaragoza, Mallol, Valls and De Mesa2013; Escánez Pérez and Perales-Raya, Reference Escánez Pérez and Perales-Raya2017). Bottom trawling is simply not an effective sampling tool for some species. For example, the oceanic flying squid (Ommastrephes caroli (Furtado, 1887)) is difficult to obtain, despite probably reaching enormous biomasses in the Mediterranean Sea, as it is almost absent from most trawls. Fernández-Álvarez et al. (Reference Fernández-Álvarez, Braid, Nigmatullin, Bolstad, Haimovici, Sánchez, Sajikumar, Ragesh and Villanueva2020) argue that this is a direct consequence of this genus’ oceanic lifestyle, coupled with the absence of directed fisheries in most of its range, which makes its collection in some localities a chance phenomenon. For the endemic Mediterranean predators (R. polystigma, T. belone and T. capelanus), there is no doubt that the prey were ingested within the distribution range of the predator. And it could be the same for all the species with an Atlantic-Mediterranean distribution. However, only in the case of Mediterranean endemic predators it is possible to establish the Mediterranean origin of the prey.

Some Mediterranean cephalopod predators can be considered true teuthivorous, while others are opportunistic, occasional predators of cephalopods. For example, S. coeruleoalba is by far the most frequent cetacean in the western Mediterranean. Its strandings along the Catalan coast account for more than 60% of the total of those that occur along the coasts of the northwestern Mediterranean (Duguy et al., Reference Duguy, Aguilar, Casinos, Grau and Raga1988). Its diet, based on fish, cephalopods and crustaceans, has been compared between the western (Alessandri et al., Reference Alessandri, Affronte and Scaravelli2001; Aznar et al., Reference Aznar, Míguez-Lozano, Ruiz, Bosch De Castro, Raga and Blanco2017; Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Aznar and Raga1995; Pedà et al., Reference Pedà, Battaglia, Scuderi, Voliani, Mancusi, Andaloro and Romeo2015; Würtz and Marrale, Reference Würtz and Marrale1993) and eastern Mediterranean (Bello, Reference Bello1992b, Reference Bello1993; Dede et al., Reference Dede, Salman and Tonay2016; Meissner et al., Reference Meissner, Macleod, Richard, Ridoux and Pierce2012; Öztürk et al., Reference Öztürk, Salman, Öztürk and Tonay2007; Pulcini et al., Reference Pulcini, Carlini and Würtz1992; Saavedra et al., Reference Saavedra, García-Polo, Giménez, Mons, Castillo, Fernández-Maldonado, De Stephanis, Pierce and Santos2022) (Supplementary material). Based on the available collected data, the preferred cephalopod prey of striped dolphins may be Onychoteuthis banksii (Leach, 1817) (family Onychoteuthidae), which was present in the majority of the stomachs of these Mediterranean cetaceans (Table 1 and Supplementary material). Other important prey for this dolphin appear to be Ommastrephidae spp. (Alessandri et al., Reference Alessandri, Affronte and Scaravelli2001; Bello, Reference Bello1992b, Reference Bello1993; Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Aznar and Raga1995; Pulcini et al., Reference Pulcini, Carlini and Würtz1992; Würtz and Marrale, Reference Würtz and Marrale1993) which were identified in almost half of the stomachs analysed by Saavedra et al. (Reference Saavedra, García-Polo, Giménez, Mons, Castillo, Fernández-Maldonado, De Stephanis, Pierce and Santos2022). However, this family was not reported by either Öztürk et al. (Reference Öztürk, Salman, Öztürk and Tonay2007) or Dede et al. (Reference Dede, Salman and Tonay2016). Aznar et al. (Reference Aznar, Míguez-Lozano, Ruiz, Bosch De Castro, Raga and Blanco2017) detected a remarkable relative decrease of oceanic cephalopods and a significant increase of the lower shelf Ommastrephidae, i.e., I. coindetii, during 1990–2012 in the western Mediterranean. According to these authors, there seems to be a shift in the diets of teuthivourous over time: the habitat shift towards the increase of some neritic prey species was most likely related to the decline of top demersal predators (Aznar et al., Reference Aznar, Míguez-Lozano, Ruiz, Bosch De Castro, Raga and Blanco2017). The possibility that Ommastrephidae had benefited from climate change is pointed out by some authors (Coll et al., Reference Coll, Navarro, Olson and Christensen2013; Pardo et al., Reference Pardo, FÁ, Varela, Navarro, Medina, Gómez-Vives, Sbragaglia, Bellido, Coll and Giménez2025). Illex coindetii was found in the stomach of several striped dolphins in the Mediterranean (Alessandri et al., Reference Alessandri, Affronte and Scaravelli2001; Pedà et al., Reference Pedà, Battaglia, Scuderi, Voliani, Mancusi, Andaloro and Romeo2015; Pulcini et al., Reference Pulcini, Carlini and Würtz1992; Würtz and Marrale, Reference Würtz and Marrale1993).

Striped dolphins also prey on other oceanic cephalopod families such as Brachioteuthidae, Chiroteuthidae, Enoploteuthidae and Histioteuthidae, or neritic species such as Alloteuthis spp. and sepiolids (Table 1 and Supplementary material). Dede et al. (Reference Dede, Salman and Tonay2016) found Chiroteuthis veranii (Férussac, 1834), Abralia veranyi (Rüppell, 1844), Histioteuthis bonnellii (Férussac, 1835) and H. dispar as species with more than 50% occurrence, apart from other pelagic and mesopelagic luminous cephalopods. They also found Pterygioteuthis giardi Fischer, 1896 and Chtenopteryx sicula (Vérany, 1851) for the first time in the stomach contents of Mediterranean striped dolphins. Meissner et al. (Reference Meissner, Macleod, Richard, Ridoux and Pierce2012) found that changes in the isotopic composition of Mediterranean S. coeruleoalba may be due to dolphin migrations away from coastal feeding grounds, some of which may be driven by migration within the Mediterranean basin, explaining the predation of these dolphins on oceanic species. Pedà et al. (Reference Pedà, Battaglia, Scuderi, Voliani, Mancusi, Andaloro and Romeo2015) suggested a possible partitioning of cephalopod resources among the Mediterranean predatory cetaceans, which was also proposed by Dede et al. (Reference Dede, Salman and Tonay2016). This partitioning may be due to the regional oceanographic and geological differences between the two Mediterranean basins (Cavazza and Wezel, Reference Cavazza and Wezel2003; Moranta et al., Reference Moranta, Quetglas, Massutí, Guijarro, Ordines, Valls, Rades and Tilesman2008), which have been colonised by cephalopod species with partly different life histories.

Grampus griseus is a cosmopolitan dolphin which, according to the studies of its stomach contents, is an obligate teuthivorous predator. In fact, except in a few very rare cases, the remains recovered from its stomach consist exclusively of cephalopods, both oceanic and demersal (Luna et al., Reference Luna, Sánchez, Chicote and Gazo2022). This suggests that G. griseus feeds both in the water column and near the bottom, both inshore and offshore. In terms of bottom-dwelling cephalopods, the prey list includes both relatively shallow-water octopods (e.g., Eledone moschata [Lamarck, 1798]) and deep-water ones (i.e., Pteroctopus tetracirrhus [Delle Chiaje, 1830] and B. sponsalis). For the oceanic species, it is more difficult to establish the depth at which they are captured by Risso’s dolphins because of their diel vertical migration. However, some species inhabit mainly deep-water layers, such as Octopoteuthis sicula Rüppell, 1844 and H. bonnellii, while others, such as I. coindetii and Tremoctopus violaceus delle Chiaje, 1830, live in shallower layers (Luna et al., Reference Luna, Sánchez, Chicote and Gazo2022: Figure 2).

In particular, Bello (Reference Bello1992a), based on the high proportion of bioluminescent prey cephalopods (86%) he found in a stranded Risso’s dolphin, hypothesised that this cetacean could detect the light emitted by these cephalopods, even though they use bioluminescence to conceal themselves through a counter-illumination mechanism. In this regard, Luna et al. (Reference Luna, Sánchez, Chicote and Gazo2022) reported in their review that G. griseus feeds primarily on histioteuthids, which are known to be bioluminescent, in addition to several other bioluminescent cephalopods. This hypothesis is also indirectly supported by the fact that G. griseus is a powerful swimmer, capable of pursuing and catching any Mediterranean cephalopod, with a preference for muscular species with high energy content (see comments on the swordfish below); therefore, the high proportion of light-emitting squids in its diet could be explained by their better visibility in the darkness of deep water. This hypothesis could also explain the high proportion of bioluminescent cephalopod prey found in S. coeruleoalba in the eastern Mediterranean, 100% in Dede et al. (Reference Dede, Salman and Tonay2016).

The dietary spectrum of the swordfish X. gladius indicates that it preys on a wide range of prey sizes. Its stomach contents include remains of both large-sized, prey-cephalopods, i.e., T. sagittatus (which constitutes the bulk of its diet), and small-sized ones, i.e., H. dispar (Bello, Reference Bello1991). (Note that we describe these species as large or small regardless of the size of the prey in each individual stomach – even a T. sagittatus is small in its juvenile stage. In many of the papers reviewed, there is no indication of the individual prey size). Moreover, the swordfish prefer muscular, swift squids (preferentially Ommastrephidae; Bello, Reference Bello1991; Carmona-Antoñanzas et al., Reference Carmona-Antoñanzas, Metochis, Grammatopoulou, Leaver and Blanco2016; Romeo et al., Reference Romeo, Battaglia, Pedà, Perzia, Consoli, Esposito and Andaloro2012), whose flesh has a comparatively high energy content compared to the ammonia-rich flesh of Histioteuthidae (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Denton and Gilpin-Brown1979). On the contrary, Histioteuthidae species represent a staple food for a variety of oceanic predators in the Mediterranean. Therefore, it seems that the swordfish is not selective on the prey-item size, but rather on the type of prey, in terms of energetic content. As for the preferred depth of predation, the swordfish seems to feed in the upper layers of the water, at least at night (Bello, Reference Bello1991), mainly on aggregating cephalopods. In fact, its high locomotor performance – including parameters such as speed (up to 130 km/h), acceleration, quick start and manoeuvrability (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Jong, Chang and Wu2009), which is also based on the presence of red muscles in its body and a heating system for the eyes and brain (Abid and Idrissi, Reference Abid and Idrissi2006) – allows the swordfish to attack and subdue any Mediterranean oceanic cephalopod species. The most striking predatory feature of the swordfish is the use of its sword to kill or injure its prey, as documented by certain remains of histioteuthids found in fish (Bello, Reference Bello1994). This peculiar predatory behaviour was later confirmed by direct underwater observation of a swordfish attacking a squid (probably an ommastrephid) in mid-water off the NW Atlantic coast (pers. comm. by Verena Tunnicliffe to G.B., supported by underwater film clip, during the World Congress of Malacology, Ponta Delgada, Azores, July 2013). Finally, it is worth noting that oceanic cephalopods, i.e., fast-growing animals, represent a major food source for the swordfish, a fast-growing fish (Tserpes and Tsimenides, Reference Tserpes and Tsimenides1995), thus contributing to an efficient transfer of energy in the food web, in which the swordfish is an apex consumer (Amaratunga, Reference Amaratunga1983; Bello, Reference Bello1991).

The small spotted catshark S. canicula is a demersal species, found on the continental shelf and at depths of between 20 and 400 m, being more abundant between 150 and 300 m. It is a mesopredator (Navarro et al., Reference Navarro, Cardador, Ám, Bellido and Coll2016) with a preference for osteichthyans, crustaceans, cephalopods and other marine molluscs (Supplementary material). It is a generalist predator (Kousteni et al., Reference Kousteni, Karachle, Megalofonou and Lefkaditou2018; Macpherson, Reference Macpherson1977) that preys on both demersal and semi-pelagic cephalopod species (Kabasakal, Reference Kabasakal2002), with prey size and depth having a significant effect on the diet of this catshark (Valls et al., Reference Valls, Quetglas, Ordines and Moranta2011) (Table 1). Partial dietetic differences have been found by different authors (compare the results in Bello Reference Bello1997; Kabasakal Reference Kabasakal2002; Keller et al., Reference Keller, Hidalgo, Álvarez-Berastegui, Bitetto, Casciaro, Cuccu, Esteban, Garofalo, González, Guijarro, Josephides, Jadaud, Lefkaditou, Maiorano, Manfredi, Marceta, Micallef, Peristeraki, Relini, Sartor, Spedicato, Tserpes and Quetglas2017; Kousteni et al., Reference Kousteni, Karachle, Megalofonou and Lefkaditou2018; Valls et al., Reference Valls, Quetglas, Ordines and Moranta2011), which might be due to geographical differences in teuthofaunal composition, different life stages/depths (according to D’Onghia et al. (Reference D’Onghia, Matarrese, Tursi and Sion1995); Massutí and Moranta (Reference Massutí and Moranta2003), S. canicula juveniles and adult Mediterranean populations live on different bathymetric strata), as well as it could reflect different taxonomic expertise in identifying beaks. However, S. canicula consumes cephalopods at almost all stages of its growth (Cihangir et al., Reference Cihangir, Ünlüoğlu, Tiraṣin and Hoṣsu1997; Macpherson, Reference Macpherson1977), and I. coindetii and H. dispar appear to predominate in its feeding spectrum; both species are known to have regular contact with the bottom (Vecchione and Roper, Reference Vecchione and Roper1991). Therefore, these pelagic cephalopods may become available to sharks as they approach the bottom during the vertical diel movements (Kabasakal, Reference Kabasakal2002; Orsi-Relini and Würtz, Reference Orsi-Relini and Würtz1975). It is possible that, as suggested by Orsi-Relini and Würtz (Reference Orsi-Relini and Würtz1975), for G. melastomus, it may detect cephalopods by their light emission. Scyliorhinus canicula also moves away from the bottom and reaches bioluminescent prey (i.e., most cephalopod species in its diet) in mid-water, but not far from the bottom. Furthermore, it is not certain that the sharks catch demersal sepiolids (i.e., Rossiinae and Sepiolinae) on the bottom, as these supposedly benthic squids are actually capable of leaving the bottom and swimming several tens of metres upwards (Bello and Biagi, Reference Bello and Biagi1995).

The blackmouth catshark G. melastomus is a small catshark, the deepest living one in the Mediterranean. Its prey-cephalopod spectrum overlaps to some extent with that of E. spinax, both in terms of habitat and body size (Fanelli et al., Reference Fanelli, Rey, Torre and Gil de2009). The cephalopod remains in this fish belong to both demersal and oceanic species; thus it feeds both in the water column and near the bottom. Its preferred prey-cephalopods are small-sized ones, mainly Sepiolidae, but juveniles of large-sized species also contribute to its diet (Fanelli et al., Reference Fanelli, Rey, Torre and Gil de2009). The cephalopod prey size correlates with the size of G. melastomus. Moreover, in those cases where the remains consisted of bitten off pieces, they always came from the posterior part of the body (either the arms or the arm crown or the arm crown + head; unlike the velvet belly, see below). These results show that G. melastomus pursues prey items that can be ingested whole, although in many cases it only succeeds in biting off the trailing portion of the prey (Bello, Reference Bello1997). In summary, the hypothesis of a solitary prey pursuit behaviour is robustly supported.

In contrast to G. melastomus, the deep demersal small-sized velvet belly, E. spinax – although like G. melastomus it preys on both demersal and oceanic prey – is capable of attacking comparatively large prey, possibly carrying out group predation (Bello, Reference Bello1997). This small shark shows a higher preference for cephalopod prey on slope bottoms around the Balearic Islands (Valls et al., Reference Valls, Quetglas, Ordines and Moranta2011).

In general, ontogenetic shifts in diet are common in sharks, which may be attributed to increased predator size and appear to be adaptations to the higher metabolic requirements of larger individuals switching to larger prey types (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Goldman, Lowe, Carrier, Musick and Heithaus2004; Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Wetherbee, Crow and Tester1996; Macpherson, Reference Macpherson1986). The decrease in cephalopod abundance as the catshark G. melastomus increases in size indicates an ontogenetic shift in diet in favour of bony fishes. In addition, the differences observed in the condition of the beaks retained in the stomach contents of S. canicula and S. blainville, and in the variation in prey species diversity according to the size of the predators, may imply differences in their foraging tactics (prey hunting vs. bottom scavenging), habitats and stomach evacuation frequency (Kousteni et al., Reference Kousteni, Karachle, Megalofonou and Lefkaditou2018).

Moreover, the existence of different feeding spectra in different demersal chondrichthyan species underlines the existence of a trophic partitioning by depth in the Mediterranean Sea (Carrassón et al., Reference Carrassón, Stefanescu and Cartes1992; Macpherson, Reference Macpherson1977), but also by the feeding behaviour. Cephalopods from the stomachs of circalittoral specimens of Raja clavata Linnaeus, 1758 and S. canicula are typically caught on the circalittoral grounds and differ from cephalopods of G. melastomus and E. spinax caught on the upper slope (Bello, Reference Bello1997). This is in line with the possible partitioning of cephalopod resources among Mediterranean cetaceans of Pedà et al. (Reference Pedà, Battaglia, Scuderi, Voliani, Mancusi, Andaloro and Romeo2015) and Dede et al. (Reference Dede, Salman and Tonay2016).

The albacore, T. alalunga, is a very active medium-sized tuna that migrates in the Mediterranean Sea, appearing in areas of the eastern Mediterranean in autumn-winter. It has been described as an opportunistic predator that feeds on available prey species depending on both the season and the geographical area (Consoli et al., Reference Consoli, Romeo, Battaglia, Castriota, Esposito and Andaloro2008; Goñi et al., Reference Goñi, Logan, Arrizabalaga, Jarry and Lutcavage2011). Its predator activity is mainly directed towards diel migrating mesopelagic and, secondarily, epipelagic items. As for cephalopods in particular, they were mainly preyed upon during the evening/night when they migrate towards the upper water layers (Consoli et al., Reference Consoli, Romeo, Battaglia, Castriota, Esposito and Andaloro2008). In terms of prey size, no shift with predator size was observed (Consoli et al., Reference Consoli, Romeo, Battaglia, Castriota, Esposito and Andaloro2008). According to Bello (Reference Bello1991), albacore feed mainly, if not exclusively, on small-sized cephalopods: both small species (e.g., H. dispar) and early subadults of large species (e.g., T. sagittatus). This may also be inferred indirectly from data from other studies: e.g., Consoli et al. (Reference Consoli, Romeo, Battaglia, Castriota, Esposito and Andaloro2008) refer to Paralepis spp. as the main prey, with a maximum size of about 12 cm; Goñi et al. (Reference Goñi, Logan, Arrizabalaga, Jarry and Lutcavage2011) reported both small bony fishes and krill. It can therefore be concluded that T. alalunga is a relatively ‘microphagous’ predator. Finally, at least in some areas, such as the southern Adriatic Sea (eastern Mediterranean), schooling albacore represent an important mortality factor for juvenile squids (estimated prey in one autumn/winter season = 1.3 million T. sagittatus juveniles and 1 million H. bonnellii juveniles [Bello, Reference Bello1991]), as well as 4 million other small-sized oceanic cephalopods.

The common dolphinfish, C. hippurus, is a cosmopolitan fish species found in tropical and subtropical seas, often associated with floating debris. Since early history, this species has been an important food source for people living around the Mediterranean. In this area, it is seasonal and is exploited by traditional fisheries in Malta, Tunisia, Sicily and Mallorca using attracting devices and purse nets (Massutí and Morales-Nin, Reference Massutí and Morales-Nin1995). Despite the local importance of C. hippurus in the Mediterranean, its feeding habits have been scarcely studied in this area (Benseddik et al., Reference Benseddik, Besbes, Ezzeddine-Najai, Jarboui and Mrabet2015; Massutí et al., Reference Massutí, Deudero, Sánchez and Morales1998).

There are three species that can be considered Lessepsian or anti-Lessepsian. It is the case of two Lessepsian species, the invasive Teleostei L. sceleratus and S. undosquamis, which entered the Mediterranean Sea through the Suez Canal; and M. helena, an anti-Lessepsian species expanded from the Mediterranean Sea to the Indian ocean.

Among the cephalopods, T. sagittatus is the largest consumer of cephalopods and is also one of the most common prey species, consumed by 20 different predators (Table 1 and Supplementary material). Here is a clear example of a predator becoming prey, or vice versa, demonstrating the complex interactions that occur in food chains. Heteroteuthis dispar also occurs in the diet of many predators (23 of them) (Table 1 and Supplementary material), and despite its small body size, it seems to play an important role in Mediterranean food webs (Bello, Reference Bello1999). According to Kousteni et al. (Reference Kousteni, Karachle, Megalofonou and Lefkaditou2018), H. dispar seems to be quite abundant on the upper slope of the Mediterranean Sea, as it is one of the most frequently found cephalopods in the diet of demersal chondrichthyans (Bello, Reference Bello1997; Lefkaditou, Reference Lefkaditou, Papaconstantinou, Zenetos, Vassilopoulou and Tserpes2007), large pelagic fishes (Bello, Reference Bello1991, Reference Bello1999; Salman and Karakulak, Reference Salman and Karakulak2009) and dolphins (Orsi-Relini and Garibaldi, Reference Orsi-Relini and Garibaldi2005; Orsi-Relini et al., Reference Orsi-Relini, Garibaldi and Poggi1997), as well as in the catches of experimental mesopelagic trawls and macroplankton devices (Lefkaditou et al., Reference Lefkaditou, Papaconstantinou and Anastasopoulou1999; Roper, Reference Roper1974). The presence of H. dispar in the stomach contents of predators coming from different depth zones corresponds to its high tendency for vertical migration (Roper, Reference Roper1974). However, we must not forget the possibility of doubt raised by Clarke (Reference Clarke1980) on the assertion of the geographical distribution of predators that can move rapidly away from their feeding grounds.

Fisheries data on abundance and biomass have not been used for comparison with the data extracted from the literature because it is very difficult to extract them from existing and reviewed articles. Often, these articles barely have a taxonomic list of cephalopod prey extracted from the stomachs of predators. It would be a phenomenal task for teuthologists to try to extrapolate (sizes, weights, abundances, biomasses, inter- and intraspecific interactions) all the valuable data buried in these papers, due to how difficult it is to extract this information and standardise it for comparison.

To conclude, as stated above, the analysis of studies on the role of cephalopods as prey species in Mediterranean food webs shows a very different picture from that derived from fisheries research, which is not surprising since many predators are efficient collectors of apparently rare species, as already pointed out by Clarke since 1977 (Clarke, Reference Clarke1977; see also Bello, Reference Bello1996). Therefore, the present review contributes to the definition of the overall Mediterranean teuthofaunal situation (e.g., Kabasakal, Reference Kabasakal2002) on how the stomach content analysis of some chondrichthyans may give a good indication of the marine fauna in a specific area, both from an ecological and biogeographical standpoints; the outmost role of cephalopods in food webs, both demersal and pelagic, both in shallow and in deep waters; and also specific information on the behaviour and the habits of some teuthivorous predators.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315425100775.

Funding

Funding for open access charge: Institut de Ciències del Mar – Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Marinas (ICM – CSIC), Barcelona (Spain).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare none.

Data availability

The data underlying the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics declarations

Ethical review and approval were not required for this study because this work does not contain any experimental studies with live animals.

Compliance with ethical standards

We did not require animal ethics approval for this research because we did not use animal samples, but only literature data. This manuscript complies with the Ethical Rules applicable to this journal.