Introduction

“Lead was to the Romans what plastic is to us.” Footnote 1

Parallels can certainly be drawn between ancient lead (Pb) and modern plastic in terms of the versality, abundance, and unrealized toxicity of these materials in daily life. Lead isotopes in ice cores and peat bogs document a sharp spike in anthropogenic emissions during Greco-Roman Antiquity, in part resulting from growing demands for silver coinage and the consequent exploitation of argentiferous lead ores.Footnote 2 Lead was a much more abundant byproduct than the targeted silver; for example, at Laurion, it is suggested that ores contained 20% lead but only 0.04% silver.Footnote 3 Estimates suggest that at its peak, the Roman Empire produced an estimated 80,000 metric tons of lead per year, equivalent to production levels observed at the onset of the European Industrial Revolution.Footnote 4 The Romans’ exploitation of lead raises intriguing lines of archaeological inquiry into the intersections of lead use with health, economy, and society. Recent scholarship in archaeological chemistry has focused on Roman lead exploitation as a basis for isotopic provenance. Lead isotopic ratios in metallic artifacts and dental enamel vary regionally, and can provide insights into mining activity, trade networks, and human mobility and migration.Footnote 5 While this is an exciting research direction, we should not forget that widespread lead use would have also undoubtedly impacted population health. Archaeological human skeletal remains have served as indicators of population exposure,Footnote 6 and novel research has attempted to relate these skeletal lead burdens to other paleopathological indicators to better understand the impacts of lead on morbidity and mortality.Footnote 7 Lead has also served as a proxy for societal change and (in)stability, with fluctuations in faunal skeletal lead burdens, city water lead contamination levels, and lead pollution levels reflecting periods of social, economic, and political turbulence.Footnote 8

Discussions of Roman lead use have, at times, become sensationalized. Excerpts from ancient written texts and selected archaeological artifacts have been used to fuel more extreme speculations that lead use contributed to the decline of the Roman Empire. In 1965, sociologist Seabury Colum Gilfillan famously speculated that the Roman Empire’s use of lead contributed to its general decline, an assertion that restated and popularized earlier arguments by Karl Hofmann and his student Rudolf Kobert.Footnote 9 Gilfillan’s argument focused not on the historically documented political, economic, and military struggles that fractured the Roman Empire, but rather on what he felt was its “decay.” He argued that this stemmed from the end of novelty in the arts and sciences as the Roman aristocracy rapidly declined, beginning in the 2nd or 1st c. BCE, as the result of lead-induced infertility, miscarriage, and child mortality. According to Gilfillan, the primary source of this poisoning was the use of lead vessels in cookery and the consumption of wine adulterated with lead, both of which he claimed would have disproportionately affected the rich. Gilfillan’s argument received support from renowned environmental and public health scientist Jerome Nriagu, whose publications on the history of lead built on Gilfillan’s argument.Footnote 10 The core arguments of this model – that the key sources of ancient lead exposure were enriched syrups, adulterated wine, and lead pipes, and that lead poisoning was rampant in Roman civilization – continue to linger, despite criticism from classicists and historians for improper citations and liberal interpretation of the classical literature.Footnote 11 Recently, researchers modeling atmospheric lead pollution from ice core data have suggested that levels across much of the Roman Empire in the 1st to 2nd c. CE were high enough to cause measurable cognitive effects on children.Footnote 12 This proposal is likely to renew debates over the broader impact of lead on Roman lives.

Bioarchaeology and archaeological chemistry have produced exciting information on Roman lead use and its impacts, but this is scattered through works that often assume familiarity with the methods involved, warranting an up-to-date general overview. In this critical review, we take a three-pronged approach to assessing the current evidence for lead use in Roman Antiquity, summarizing (1) ancient accounts of lead use and poisoning, (2) the material and archaeological evidence for lead artifacts and lead use in the Roman Empire, and (3) skeletal lead burdens of individuals from Roman populations, with particular emphasis on the potential health effects of this metal on ancient populations.Footnote 13 We consider these streams of evidence in the context of modern toxicological research on lead to better infer potential lead exposure and absorption risk. We place particular emphasis on domestic lead exposure by introducing a framework approach to assess the importance of lead objects in some Imperial Roman domestic assemblages and synthesize published bioarchaeological data to examine variability in lead exposure within and between Roman populations. We attempt to remain cautious in interpreting these lines of evidence, hoping to provide a comprehensive synthesis that will serve as a resource for the broader research community.

Lead in the body

Clinical and toxicological research on lead serves as an important touchpoint when considering lead exposure in antiquity. Lead can be absorbed into the body through the gastrointestinal tract, respiratory system, skin, or placenta.Footnote 14 Children absorb significantly more lead than adults, due both to behavioral factors (e.g., infant mouthing and eating with hands) and physiological and developmental factors (e.g., immature gut structure, increased nutritional demands).Footnote 15 Individual nutritional status can influence the gastrointestinal absorption of lead; starvation, fasting events, or nutritional deficiencies in calcium, iron, or Vitamin C have been linked to increased lead absorption.Footnote 16 While possible, lead absorption through the skin results in negligible uptake.Footnote 17 Thus, handling inert lead objects poses a significantly lower risk of exposure than other pathways.

Once absorbed by the body, lead is highly disruptive on a cellular level. Lead can readily substitute or displace essential ions like calcium, iron, zinc, magnesium, and sodium, which disrupts regular function.Footnote 18 Lead can also induce oxidative stress and disrupt DNA methylation, leading to epigenetic changes in gene expression.Footnote 19 The consequences of these disruptions largely depend on exposure: short-term episodes of high-level lead exposure produce acute toxicity, and long-term episodes of lower-level lead exposure produce chronic toxicity. The clinical picture of acute lead toxicity includes severe abdominal colic and a range of neurological symptoms, such as staggering gait, delirium, convulsions, seizures, and coma.Footnote 20 Studies of chronic lead toxicity demonstrate both the extent of lead’s impact on all body systems and the surprisingly low levels at which these effects can occur. Lead is famous for its neurotoxic effects, leading to fatigue, headaches, intellectual impairment and memory loss, mood or behavior changes, motor and sensory impairments, and psychiatric symptoms. Chronic lead exposure has also been linked to kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, infertility and adverse birth outcomes, decreased immune function, anemia, diminished musculoskeletal development and functioning, and increased risk of cancer.Footnote 21 The impacts of lead are heightened for children, whose organ systems are actively developing and thus more susceptible to irreversible damage from lead. The transplacental transfer of lead from mother to child can result in lead poisoning during critical fetal development. Due to the disproportionate effects of lead toxicity on children, it is important to consider how children may have been exposed to lead in antiquity.Footnote 22

The body is highly efficient at removing lead from the bloodstream through excretion and sequestration; the kidneys, and to a lesser extent, the saliva, sweat, hair, and fingernails readily excrete lead, and the skeleton readily stores lead.Footnote 23 Within the skeleton, lead can substitute for calcium in hydroxyapatite, the mineral component of the bones and teeth.Footnote 24 In the context of bioarchaeology, this means that skeletal remains record lead exposure. For teeth, this window of lead incorporation is mostly limited to the specific interval during which the tooth forms. Bone, by contrast, is not a permanent reservoir for lead; remodeling ultimately returns lead stored in the bones to the bloodstream where it can act as an endogenous source of lead exposure years after initial exposure.Footnote 25 During life, bone remodeling rates are dynamic. Pregnancy, lactation, and disease states such as osteoporosis can result in higher rates of bone turnover, resulting in a higher rate of lead release back into the bloodstream.Footnote 26 In the case of pregnancy, this heightened bone turnover serves to mobilize calcium stores to support fetal development but also has important implications for both maternal and fetal health in antiquity.Footnote 27 The release of stored lead back into the bloodstream can act as an endogenous source of exposure for the mother, resulting in adverse health and pregnancy outcomes, but also for the fetus, for whom transplacental lead uptake can have critical effects on development. As the deciduous dentition largely forms in utero, fetal and infant enamel lead concentrations and isotopic ratios are largely reflective of the maternal lead burden during pregnancy, providing a window into maternal health and provenance, respectively.

Evidence of ancient lead use

The written record: ancient authors on lead use

The ancient written record presents first-hand accounts of how lead was used in the past and what ancient populations knew of lead. Because so much previous attention has been given to ancient written accounts, this evidence will only be briefly summarized here. We limit our discussion to the uses of lead most commented upon and those which, based on modern understanding, would be most likely to cause lead toxicity: food and drink, plumbing, cosmetics, and medicine. The ancient sources cited are mainly Roman Imperial-era works originating within the geographical extent of the Roman Empire, though we also refer to a couple of 2nd c. BCE sources that are of relevance to Greco-Roman lead use.

The source of lead that seems to have captured the imagination of most modern scholars is a sweet syrup known as sapa: boiled grape juice (must) reduced to a fraction of its original volume. Sapa is sometimes synonymously referred to as caroenum or defrutum in the literature, although there appear to have been some differences in reduction volume between the three syrups and some disagreement in the literature as to which term represents which reduction volume.Footnote 28 These syrups were a staple in the Roman diet, serving as food sweeteners, flavor additives, and coloring agents. In fact, over 80 recipes in the Roman culinary book De Re Coquinaria attributed to Apicius (ca. 5th c. CE) include caroenum, defrutum, or must. They were also a useful preservative for fruit; both Apicius and Cato, for example, suggest pears and quinces can be preserved in a sapa or defrutum mixture.Footnote 29

Sapa and defrutum were also used as preservatives for lower-quality wine or as an additive to ameliorate spoilt wines. Columella writes that “the best wine [is] any kind which can keep without preservative, nor should anything at all be mixed with it by which its natural savour would be obscured.”Footnote 30 Yet doctoring wine with sapa or other preservatives seems to have been a common practice in antiquity: Columella contradictorily states that “care must be taken that the flavour of the preservative is not noticeable, for that drives away the purchaser.”Footnote 31 According to Pliny, space should be left in the tops of wine jars to accommodate a mixture of passum (raisin wine), defrutum mixed with saffron, old pitch, or sapa and the jar lids should also be treated with the mixture.Footnote 32 According to Columella, one sextarius of properly prepared must added to one amphora of wine is sufficient for preservation.Footnote 33 Eisinger’s estimates suggest this would equate to one part sapa to 48 parts wine.Footnote 34

Pure sapa would not contain lead; however, many classical authors recommend the use of leaden vessels for its preparation, including Cato in De re rustica, Columella in De re rustica, and Pliny in Historia naturalis. According to Columella, lead should be used in preference to brass in preparing sapa because “in the boiling, brazen vessels throw off copper-rust, and spoil the flavour.”Footnote 35 Pliny echoes this sentiment about copper vessels.Footnote 36 However, if prepared in leaden, lead-coated, or lead-alloyed vessels, the acetic acid of grape juice would react with the lead to precipitate a salt called lead acetate, also known as the sugar of lead.Footnote 37 In addition to conferring a sweet flavor to the syrup, the use of lead-enriched sapa as a preservative can likely be attributed to lead’s bactericidal properties.Footnote 38 Hofmann’s imitation of one of Columella’s recipes produced sapa containing 781 mg/L Pb, and Eisinger, following Pliny, produced sapa containing 1,000 mg/L Pb.Footnote 39 If Columella’s instructions for doctoring wine were followed, this would produce wine containing 20 mg/L Pb.Footnote 40

The Romans also used lead widely in pipes. In fact, the word plumbing originates from the Latin term for lead, plumbum, and the term for pipe makers, plumbarii, equates to “leadmen.” According to Pliny, “where water is wanted to ascend aloft, it should be conveyed in pipes of lead,”Footnote 41 suggesting lead was preferred for aqueducts.

According to some ancient authors, white lead was sometimes used in cosmetics. Pliny describes the preparation of ceruse (white lead) for “whiten[ing] the complexion,” in which white lead shavings are dissolved by vinegar and divided into tablets.Footnote 42 As described by Ovid in Medicamina faciei, white lead could also be combined with roasted lupin-seeds, fried beans, red natron scum, and Illyrican iris to form a facial cleanser.Footnote 43

Lead also featured as an ingredient in many medicinal remedies. Pliny frequently references the dermatological benefits of topically applying lead or sapa, such as for treating burns, scars, chapped feet, “purulent eruptions of the face,”Footnote 44 and serpiginous skin ulcers. He also recommended sapa be used to treat bites and stings from variety of venomous insects and salamanders.Footnote 45 In some cases, ingestion of lead was recommended, such as doses of helxine combined with white lead for treating throat swellings.Footnote 46

Despite the wide-reaching uses of lead in antiquity, there appears to have been some awareness of its toxicity. Writing in the 2nd c. BCE, Greek poet and physician Nicander of Colophon has been credited with describing the specific effects of severe lead palsy:

Gleaming, deadly white lead whose fresh color is like milk which foams all over when you milk it rich in the springtime into the deep pails. Over the victim’s jaws and in the grooves of the gums is plastered an astringent froth, and the furrow of the tongue turns rough on either side, and the depth of the throat grows somewhat dry, and from the pernicious venom follows a dry retching and hawking, for this is severe; meanwhile, his spirit sickens and he is worn out with mortal suffering. His body too grows chill, while sometimes his eyes behold strange illusions or else he drowses; nor can he bestir his limbs as heretofore, and he succumbs to the overmastering fatigue.Footnote 47

During the Roman period, however, the awareness of lead’s toxicity seems to have been restricted to specific quantities or forms of lead, especially white lead. Concerning metallic lead uses, Vitruvius explicitly cautioned against the consumption of water specifically from lead pipes, stating that “the water from clay pipes is much more healthful than that from lead” – a sentiment echoed by Columella.Footnote 48 Pliny also commented that sapa can be poisonous, particularly if consumed by someone who is fasting, and if consumed immediately after a bath.Footnote 49 Galen writes that white lead and litharge, along with select other substances, should only be applied externally rather than internally.Footnote 50 There is also some awareness of lead toxicity associated with occupational contexts, such as mine working or metalworking. For example, Vitruvius commented that lead workers’ coloring “is overcome by pallor,” and Pliny described the “noxious vapor … of a deadly nature, to dogs in particular” produced from melting lead.Footnote 51

Ancient antidotes for lead ingestion are the most direct acknowledgement of lead’s toxicity. Pliny suggests that different concoctions of donkey’s milk, wild figs, or mallow can counteract the poisonous effects of white lead. The Romans’ use of lead as a contraceptive and abortifacient also demonstrates some awareness of its toxic effects regarding fertility. Soranus suggests that the internal application of white lead has contraceptive benefits for females, and Pliny writes that sapa, taken with onion, has the “effect of bringing away the dead fetus and the after-birth.”Footnote 52

The material record: archaeological and physical evidence for lead use

Ancient written sources, while highly valuable, are limited in that they represent a single individual’s perception of the world around them, as well as largely reflecting the elite male perspective in Roman society. It is difficult to reliably ground a given practice or use of lead within the wider region or period based on these written accounts alone. The archaeological record can help to address this problem of interpreting ancient lead use, allowing us to compare the written record on lead to the physical evidence. Certain practices or applications of lead may not have been extensively written about, or texts may not have survived; alternatively, a lead use clearly outlined in ancient texts may not have truly been a widespread practice. This section provides an overview of the common categories of lead artifacts excavated archaeologically in Roman contexts. While outside the scope of the present article, atmospheric pollution was also a potential vector for lead exposure in antiquity, as demonstrated by recent environmental archival and modeling research.Footnote 53

As with the textual record, there are some limitations to considering ancient material evidence of lead. First, evidence for a type of lead object in the archaeological record is not evidence for its widespread use; the mere existence of a given object does not mean that most Roman populations would have been exposed to lead via that object type. Second, the nature of the archaeological record itself is dynamic. Throughout time, artifacts may be salvaged, recycled, and looted, and the sites themselves undergo taphonomic transformation processes; thus, the archaeological record is not a perfect record of lead use in the past. Artifacts may also degrade or fragment through time, so that their original structure or function cannot be adequately attributed. Third, we are consulting published literature and accessible museum archives for this information, and thus only have access to what has been made available. On a related note, there may be an inherent bias in the literature. As aptly put by Brown, “lead is often relegated to a footnote or sidebar in the study of ancient metals.”Footnote 54 Consequently, lead objects may not be published with the same frequency as those made of metals deemed more precious. Finally, metals alloyed with lead may be underreported among lead finds from archaeological sites unless all objects have undergone chemical analysis to determine their metallic composition.

General categories of lead artifacts

LEAD INGESTION FROM VESSELS, FOOD, AND WINE – Some lead cookery and food storage vessels have been uncovered archaeologically; for example, on shipwrecks from the Israeli Coast, Rosen and Galili found that many of the cookware and storage vessels for food and beverages on board were leaden objects.Footnote 55 Lead or lead-alloyed utensils and receptacles (such as containers and cups) have also been found across Roman archaeological sites.Footnote 56 However, the relative dearth of lead cooking vessels is inconsistent with modern theories based on the written accounts by Cato, Columella, and Pliny.Footnote 57 Lead recycling during antiquity could partially account for the archaeological underrepresentation of such vessels, but it remains unclear how often sapa and other comestibles were enriched with lead through these means.

In the relative absence of archaeologically recovered lead cookware vessels, chemical analyses of food and drink remains offer another way to assess lead concentrations in ancient food and wine. Arobba and colleagues analyzed the liquid residue extracted from a sealed Dressel 1B amphora from an Early Roman shipwreck off the coast of Albingaunum (Albenga), Italy to determine the amphora’s original contents.Footnote 58 Chemical, isotopic, and palynological results from the residue analyses were consistent with wine, and the authors suggested that the residue’s lead concentration of 1.5 µg/g further supported this interpretation. While this value is an increase over concentrations typically found in modern wines, it is still considerably lower than the estimated wine lead concentrations from Hofmann’s and Eisinger’s experiments. It is therefore unlikely that this wine was enriched with lead-contaminated sapa: the wine’s lead concentration may have simply been the result of production in a society where there was widespread lead use and ambient lead pollution. It is also important to consider the potential impact of degradation over time and seawater contamination on the trace element concentrations of the liquid contained in the amphora.

At a Roman cemetery site near Valkenburg in the Netherlands, analyses of fish bones associated with the production of garum revealed lead concentrations of 670 µg/g.Footnote 59 The authors of the study attribute this high reading to the addition of lead-enriched sapa to garum during preparation. It is important to note, however, that the fish bones could have also been subjected to diagenetic (postmortem) contamination from lead solutes in the depositional environment, as is common for archaeological skeletal remains.

Analyzing the chemical composition of amphorae and other types of pottery that once contained foodstuffs and beverages can be another means of estimating lead ingestion. Hossain used laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) to analyze the distribution of lead in Roman amphorae samples from Lusitania.Footnote 60 Two of the 12 samples exhibited a heterogenous distribution of lead, with highly elevated lead enrichment on the inside of the amphora relative to the outside. These two amphora samples also contained evidence for the presence of diterpenic compounds associated with Pinaceae (pine) plants, which suggests the vessels were waterproofed with a resinous pitch coating to carry liquids, possibly wine.Footnote 61 Amphora samples from an early Roman villa in Sa Mesquida (Mallorca, Spain) had lead concentrations ranging from 21 to 55 µg/g, with an average concentration of 29.75 µg/g.Footnote 62 Most amphorae contained chemical evidence for the presence of pine resin and tartaric, succinic, malic, and fumaric acids, which are consistent with grape products and wine. Interestingly, the amphora with the highest lead concentration lacked this chemical evidence, leading the authors to suggest that a fermented substance other than wine was stored and transported in this amphora. Finally, De la Villa and colleagues’ analyses of Late Roman amphorae recovered from shipwrecks along the coast of Gibraltar revealed lead concentrations ranging from <0.5 to 976 µg/g, with a mean concentration of 104 µg/g.Footnote 63 However, they attribute these high lead concentrations to the use of lead in the engobium used to coat these ceramics, rather than the use of sapa. In summary, while the lead and lead-alloyed cauldrons supposedly used to prepare sapa are rare in the archaeological record, there is mixed evidence for cultural practices resulting in the enrichment of food and wine with lead.

Lead may also have been ingested through the use of lead-repaired ceramics, which are a common find at archaeological sites across the Roman Empire. During antiquity, lead was used to fill holes, reinforce hairline cracks, and repair breaks in ceramic vessels.Footnote 64 This work could take many forms: molten lead could be used to plug holes, and cracks or breaks could be repaired with internal clamps, cleats (tenons), rivets (staples), or strips of lead.Footnote 65 Croom suggests some repair techniques would not necessarily have required a specialist craftsperson: given lead’s low melting point, individuals could feasibly have performed rudimentary repairs in the home by melting lead in a pot and pouring it directly onto the broken vessel.Footnote 66 More sophisticated repairs, involving drilling holes into the vessel for lead wires or staples, may have required a specialist workshop. A possible example of such a workshop has been found at Kempston Church End, Bedfordshire, where there is compelling evidence for both ceramic repair and recycling activities.Footnote 67 Presumably repairing vessels could expose an individual to relatively high levels of lead (e.g., through inhalation of lead fumes). There would also have been a certain level of exposure risk to individuals consuming food or beverages from these vessels. Any lead present in repairs to the interior surface of a vessel could be mobilized into the stored food or liquid, a process which modern toxicity research suggests could be exacerbated by heat, acidity, or stagnation time.Footnote 68

Lead was also sometimes used in glazes for ceramics during the Roman period. These glazes were formulated from either lead oxide (PbO) or PbO mixed with quartz.Footnote 69 They were advantageous for several reasons. They were cheap, easily produced and applied to vessels, had a low firing temperature, and were resistant to cracking and crawling.Footnote 70 Lead-glazed ceramics began to appear during the Late Hellenistic to Early Roman period (1st c. BCE) in Anatolia, and spread to the western Mediterranean during the Augustan period, with production foci in Italy and Gaul.Footnote 71 By the late 1st c. CE, the popularity of lead-glazed ceramics had grown, with evidence for their use in Italy, Gaul, Britain, and northeast Spain, as well as along the Danube.Footnote 72 It is thought that interest in lead-glazed ceramics during this period may have derived from the way they imitated more expensive metallic vessels: for example, early lead-glazed skyphoi often had a green exterior and yellow interior, mimicking copper-alloy vessels.Footnote 73 While the popularity of lead-glazed ceramics certainly grew during the Roman period, their production and circulation still remained relatively low, and they never fully saturated the Imperial Roman marketplace. Greene suggests that the burgeoning Roman glassware industry “left no economic or cultural niche” for lead-glazed ceramics.Footnote 74

Acidic substances cause high levels of lead leaching from glazed vessels, contaminating the food or liquid in question; less acidic foods result in lower levels of lead leaching.Footnote 75 Rasmussen and colleagues’ experimental research on Byzantine glazed potsherds serves as a useful parallel to help infer the health risks associated with Roman glazed ceramics.Footnote 76 They undertook acid etching experiments on several sherd samples to assess the extent to which glazed ceramics may have been a regular source of lead exposure in medieval Europe. Acid extracts from sherds ranged from 0.301 to 29,100 µg/g Pb cm−2 day−1, with an average of 1,549.33 µg/g Pb cm−2 per day. The authors also found that lead concentrations in acid extracts increased exponentially with increasing PbO content in glazes. While Roman period glazed ceramics were relatively rare compared to those of the Middle to Late Byzantine period, this experimental research shows that glazed ceramics could have presented a high risk of lead ingestion, particularly when they contained acidic foodstuffs such as wine, grape juice, or vinegar.

Finally, lead exposure could have occurred through occupational glass manufacturing or through consumption of food and beverages from glass vessels. Due to the naturally low concentrations of lead in sands typically used for glassmaking, instances of high lead concentrations (e.g., >100 µg/g) in archaeological glass suggest cases where lead compounds were intentionally added as glass opacifiers or (de)colorants, or that recycled glass with a high lead concentration was incorporated into the cullet.Footnote 77

ARCHITECTURE AND BUILDING – Archaeological evidence attests to the widespread use of lead in the general Roman building industry; for example, lead was used for clamps, sheets, strips, sheaths, dowels, pipes, and joints. The shipbuilding industry also made extensive use of lead. The aforementioned shipwrecks from the Israeli coast contained lead hull sheathing, hull patch repairs, bilge-pump constituents, weights, anchor parts, and braziers.Footnote 78 Lead oxide was also sometimes added to tile grout.Footnote 79 These applications of lead would have resulted in a high risk of occupational exposure for the artisans constructing these objects from raw materials, through the inhalation of lead fumes and ingestion of lead particulates; however, its presence in buildings and infrastructure would have likely had minimal health repercussions for the public.

Lead plumbing was a common practice in Roman Antiquity, archaeological evidence confirming ancient accounts. Within water distribution systems, lead would sometimes be used for pressurized siphons in aqueducts, for networks of water pipes (fistulae) connecting sources of water with fountains, waterworks, private residences, and baths within cities, and for water storage tanks and cisterns. Lead pipes were commonly formulated from lead sheets jointed with molten lead.Footnote 80 Archaeological evidence for the use of lead in plumbing has been most frequently noted in the Roman West, though evidence has also been uncovered in the Eastern Empire, such as at Roman Corinth.Footnote 81 If lead was present in the supply of drinking water, we can imagine it would have contributed to low-level exposure. Although boiling might have rendered the water safe to drink, it would not have removed its heavy metal content. In addition to consuming water alone or mixed with wine, the Romans of course used it culinarily, in dishes such as soups, stews, and grain porridges, all of which would have contained a substantial portion of water with its attendant lead.Footnote 82 The question of whether there were substantial concentrations of lead in a particular community’s drinking water is more difficult to answer. We often cannot say with certainty whether a given lead pipe from an archaeological context was indeed used for drinking water or whether it supplied water for other purposes; for example, to a bath. Additionally, unlike modern systems, Roman urban plumbing systems often had continuous water flow, limiting the opportunity for increased lead contamination of standing water.Footnote 83 Furthermore, hard water causes pipes to become encrusted with calcium carbonate (limescale), which protects water from coming into contact with the pipe.Footnote 84 This is not to say that the lead pipes presented no risk of exposure. Analysis of sediment cores from the Trajanic basin of Rome shows that the use of lead pipes may have resulted in a 40-fold increase in the lead concentration in Rome’s city water during the early Roman Period, a 14-fold increase during the Late Roman Period, and a 105-fold increase during the High Middle Ages, relative to lead levels in natural springs.Footnote 85 The authors themselves, however, suggest that this increase in lead concentration – while significant – would not have been sufficient to cause lead poisoning. To summarize, the scholarly discussion on the impact of lead plumbing on ancient populations suggests that it could have contributed to low-level, chronic lead exposure, but likely would not have constituted a key source of high exposure, the effects of which could accumulate over time. Perhaps the risk factors of lead plumbing would also have been exacerbated by local factors such as low water mineral content and stagnancy (e.g., tap infrastructure, retention in storage cisterns).

PIGMENTS – Chemical analyses of ancient artifacts confirm the use of lead in some paintings and cosmetics during antiquity. Researchers have utilized spectroscopic techniques to characterize the compounds in fresco and painting samples, finding some evidence for the use of white lead in white and pink pigments, and minium in red and orange pigments.Footnote 86 In rare cases, Naples yellow (lead antimonate: Pb2Sb2O7) has also been identified in Roman wall art.Footnote 87 Artisans using these lead-containing pigments could have inhaled or ingested lead while applying them to plaster. Based on toxicological research on modern lead paint and its risk to families and infants, it is plausible that older, degrading frescoes in ancient domiciles could have released lead particulates into the air as dust to be ingested by residents.

To examine the composition of ancient cosmetics, researchers have analyzed residues from cosmetic unguentaria. Analysis of several unidentified powders in unguentaria from Casa di Bacco House, Pompeii found lead compounds in several of the samples, including cerussite and to a lesser extent, minium.Footnote 88 This supports use of cerussa for ancient cosmetics (e.g., foundation); the minium might have been used in pink-pigmented cosmetics (e.g., rouge), but could also be a product of cerussa degradation caused by heating during the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 CE.Footnote 89 Grüner found trace evidence of galena as well as anglesite and cerussite, common alteration byproducts of galena, in a cosmetic glass vessel from Late Roman Palestine.Footnote 90 The author suggests this indicates use of galena as kohl.

At other sites, there has been a lack of evidence for lead compounds in cosmetics during Roman Antiquity. In their chemical analysis of pigments from various Greco-Roman sites, Welcomme and colleagues found evidence for the use of white lead in samples of foundation from Hellenistic sites, but not in samples from Roman Pompeii, Gaul, or Germany. These Roman foundation samples instead contained gypsum and calcite.Footnote 91

MISCELLANEOUS OBJECTS – Lead was often used in loom weights and scale counterweights.Footnote 92 Other relatively common lead artifacts are lead seals and stamps, lead and lead-lined coffins, and lead sling bullets.Footnote 93 While it is worth noting these objects to understand the breadth of lead use in Roman society, it is unlikely there was much risk of exposure for the individuals who regularly handled them (e.g., weavers, merchants, soldiers). It is likely, however, that the artisans who molded these objects would have been at high risk of occupational lead exposure.

Lead crepundia (children’s toys and jewelry) have been found in domestic assemblages and the graves of children and could feasibly have introduced children to high levels of lead through infant mouthing behaviors. Lead was sometimes used in children’s figurines, miniature furniture, rattles, teething objects, and game pieces.Footnote 94 While lead was not as popular for jewelry as other metals such as gold, silver, copper, or bronze, it was sometimes used in children’s amulets and jewelry. On the dies lustricus, or day of purification, a ritual taking place eight or nine days after birth, free Roman children would often be bestowed with a protective pendant to wear until adulthood.Footnote 95 In particular, male children were often given an amulet (bulla), which, depending on the wealth of the family, would be composed of gold, lead, or leather.

Case study: household lead exposure

While lead is clearly abundant in the material record, an archaeological perspective on domestic lead exposure during Roman Antiquity is lacking. However, there is value in examining sources of lead in the home: through modern awareness, we know infants and children would be most susceptible to the effects of lead, and the sources of household exposure would be more likely to be shared across a population, rather than affecting specific individuals of specific occupations, ages, or socioeconomic statuses. We might expect these more commonplace uses of lead within the home to be less commented upon by ancient authors or less likely to be the subject of standalone research studies.

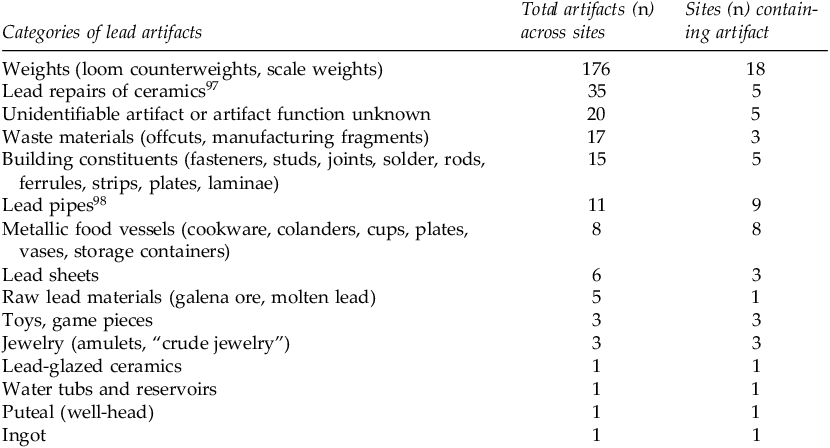

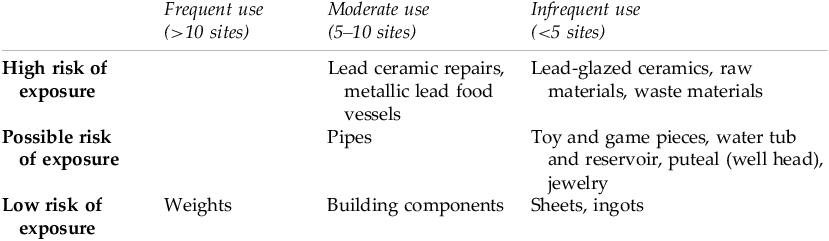

We examined dissertations, reports, and monographs that published complete and comprehensive catalogues of all finds, including metallic lead objects, from Roman domestic assemblages. The comprehensiveness was key, given the disciplinary bias towards publishing artifacts containing more precious metals. The goal of assessing these publications was to establish a preliminary framework for Roman-period household lead use. There were 41 published domestic sites that met these criteria, spanning Italy, Britain, Carthage, and Cyprus.Footnote 96 A summary of the lead objects from these domestic assemblages can be found in Table 1. This data informed the framework presented in Table 2, which classifies lead objects by their frequency across sites and the relative risks of lead exposure, based on the modern clinical and toxicological literature, that each object category would likely pose.

Table 1. Categories of lead artifacts from the assessed published domestic assemblages. Artifacts are presented by total number (n) across sites and by sites (n) containing the artifact category.

Table 2. Matrix of lead artifact frequency in archaeological domestic assemblages vs. inferred risk of exposure.

Modern literature from environmental health research clearly shows that ingestion and inhalation of lead are substantially more detrimental than dermal (skin) exposure.Footnote 99 Thus, inert lead weights, building implements, sheets, lock and tack, and ingots presented a higher risk of exposure only for artisans who initially manufactured these objects, and a lower risk of exposure for individuals who regularly handled them. Toys, game pieces, and jewelry, if merely handled, would similarly not have presented a high risk of exposure, but they could feasibly have exposed infants to lead via ingestion (i.e., mouthing behaviors).

By contrast, direct ingestion of lead could have occurred through consumption of food and drink stored in lead vessels and lead-repaired ceramics, though the function of each vessel cannot be known for certain. Lead repairs were the second most common artifact type categorized, after lead weights, speaking to their prevalence in the homes surveyed and the overall likelihood that they posed a risk of exposure for the typical Roman family. Lead-glazed ceramics occurred extremely infrequently across sites, though consumption of food and beverages from these vessels would have presented a high risk of lead exposure given the previously discussed propensity for leaching.

Evidence for lead pipes and lead jointing of pipes was moderate across sites, but the risk of exposure is largely dependent on function. As discussed above, if water was consumed from these pipes, it could have exposed the drinkers to lead; however, some households may have used the pipes for bathing rather than drinking. Other artifacts and features associated with water storage, such as puteals and basins, could feasibly have presented a risk as well; for instance, if the puteal corroded, leading to contaminated well run-off, or if the outdoor water reservoir was used for drinking water.

Some sites exhibited evidence of raw and waste lead materials, perhaps suggesting a degree of lead working within the home, which is feasible given the metal’s low melting point. David Sánchez posits that the Roman Villa at Street Farm (Tackley, Oxfordshire) is one such example of a lead workshop within the home given the presence of lead sheet offcuts, molten lead pieces, crude jewelry, and galena ore on site.Footnote 100 Such home-workshop activities would present a high risk of occupational exposure for the individual and confer risk to the other members of the household who inhaled the same air.

The bioarchaeological record: lead concentrations from skeletal remains

The written and physical records provide valuable insights into the ways in which lead may have been used in antiquity. However, these records fail to provide detailed insights into the extent to which these lead-use practices affected population health. At best, we can use modern toxicological research to infer their impacts. Bioarchaeological remains, however, provide a direct means of measuring individual lead exposure levels. As discussed above, the skeleton plays an important role in sequestering lead; therefore, archaeological skeletal remains provide us with a window into biogenic (lifetime) lead exposure.

Using academic search engines such as Google Scholar, discipline-specific journal archives, and citation tracking, we performed a survey of the literature in late 2023 to assemble all lead analysis studies performed on Roman-period skeletal remains. It should be noted that some studies included skeletal remains with a date range extending into the early medieval period. As shown in Figure 1, which depicts the archaeological sites from which skeletal remains were sampled for analysis, there is substantially more site representation in the Roman West than the Greek East. The majority of studies cluster in present-day Italy, mainly within the city of ancient Rome and its hinterland, and in the British Isles.

Fig. 1. Map of Roman archaeological sites from which bone and enamel samples have been analyzed for lead concentration. (Created by authors using ArcGIS.)

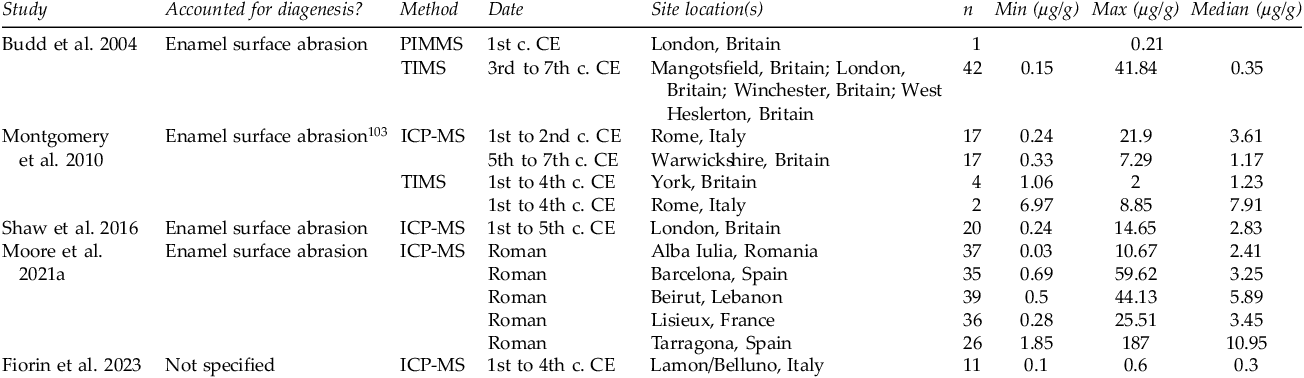

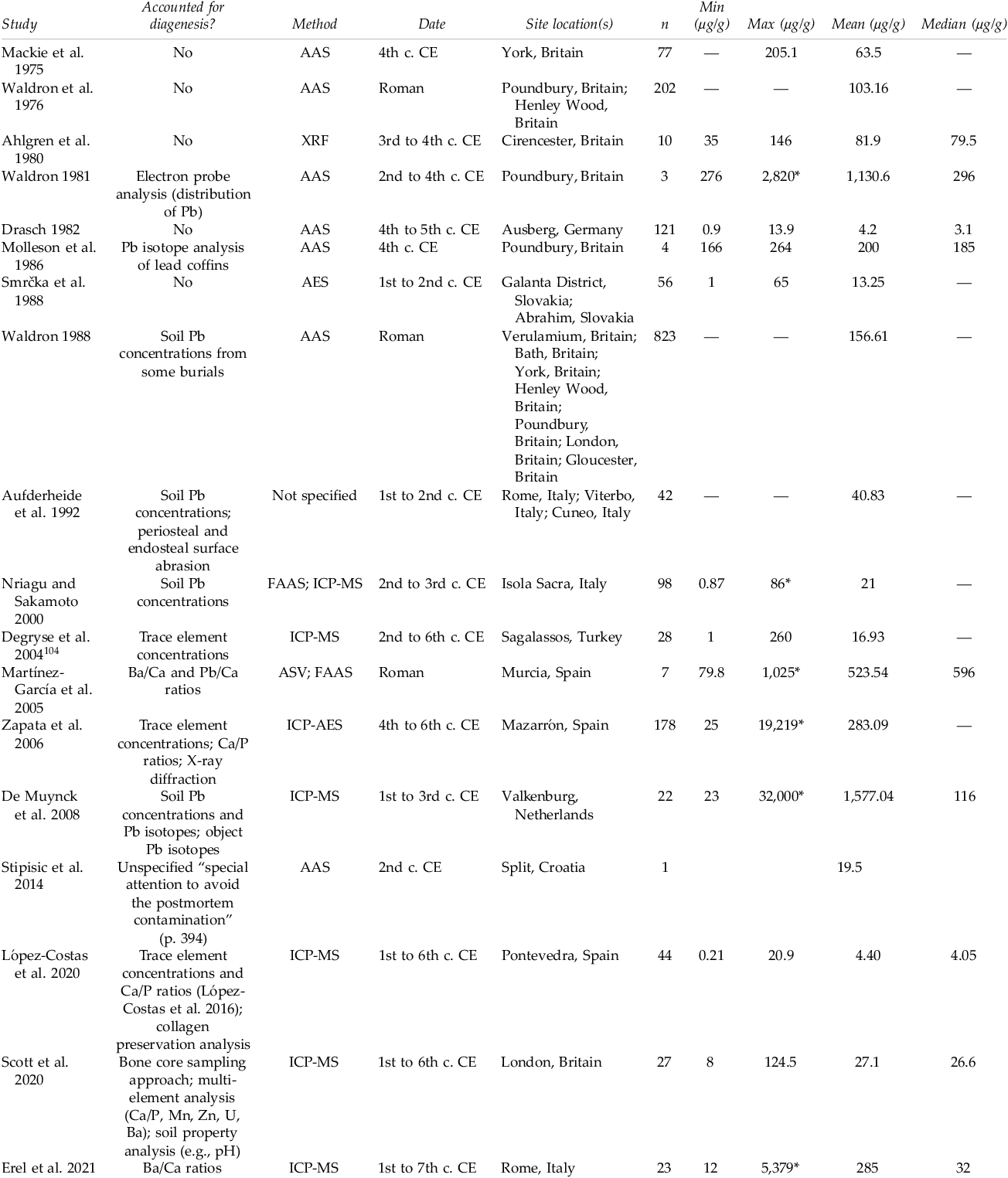

The resulting studies reporting enamel and bone concentrations are summarized in Tables 3 and 4. Enamel and bone lead concentration data are presented separately given the influence of tissue differences on the window of mineralization. Enamel and bone also differ in their susceptibility to diagenesis, a process that can include chemical contamination. Enamel is more resistant than bone and other dental tissues to diagenetic chemical alteration.Footnote 101

Table 3. Summary of studies reporting enamel lead concentrations from Imperial Roman and early medieval archaeological sites.

Table 4. Summary of studies reporting bone lead concentrations from Imperial Roman and early medieval archaeological sites.

* Authors identified diagenetic contamination in sample(s) or diagenesis suspected

The potential to compare the results of bioarchaeological lead concentration studies is limited for several reasons. First, the studies vary in terms of sample preparation methods, instruments, and analytical laboratories. Different laboratories may have different sample digestion methods, margins of error, and calibration protocols. Additionally, publications sometimes lack transparency and detail about these aspects of their methodology, which hinders both replicability and inter-study comparison.Footnote 102 Over time, advancements have been made in terms of instrument detection limits, precision, and drift, which has implications for comparing publications across time. These differences do not pose issues for the enamel studies summarized above, as the studies are transparent in their methodology and follow similar methods. These technological differences are problematic, however, for comparing the literature on bone lead concentrations: the literature encompasses a broad timeframe of scholarship, with variability in both methodology and methodological transparency.

The summarized studies also vary in their approach to identifying or accounting for diagenetic modification (the postmortem alteration of skeletal remains, including the incorporation of lead from the burial environment into the remains). The literature summarized in Table 4 documents the growth of disciplinary awareness of the existence, pervasiveness, and mechanisms of diagenesis, an awareness which was absent in the early years of research in this area. It is currently a disciplinary expectation that diagenesis be in some way accounted for, but not all methods of identifying or removing diagenetic contamination are equally effective. For example, analysis of soil lead concentrations has been a common approach for identifying potential diagenesis, but a lack of correlation between soil and bone lead concentrations has been found.Footnote 105 Other soil properties instead, such as pH, seem to be better predictors of diagenetic alteration.Footnote 106 The surfaces of enamel and bone tend to be disproportionately enriched with diagenetic lead, and therefore, physical or chemical surface abrasion or core sampling approaches can be a useful approach in removing traces of surface contamination.Footnote 107 For enamel, which is relatively resistant to diagenetic alteration, this is sufficient in most contexts, with rare exceptions.Footnote 108 For bone, this approach is adequate only if the contamination is indeed restricted to the bone surface and is insufficient in cases where diagenetic alteration has progressed into interior regions. Other approaches such as multiple trace element analysis, Ca/P ratios, and Ca/Ba ratios can serve as useful proxies for assessing overall bone quality and preservation. No one indicator, however, is truly concordant with lead diagenesis; therefore, the most reliable studies are those which draw upon multiple methods to identify it.Footnote 109

The summarized studies also vary with respect to the skeletal element sampled. Different teeth form at specific intervals in childhood, representing different timescales of development.Footnote 110 Additionally, different bones remodel at different rates, but, to date, there are limited studies investigating the specific rates by bone, which can lead to intra-skeleton variation in trace element concentrations.Footnote 111 Individual studies often target a specific bone or tooth type for sampling, which facilitates intra-study comparison but poses limitations for comparison across studies. A further reality of bioarchaeological sampling is recovery and preservation: the target element may be absent or poorly preserved. Many studies are obliged to opportunistically sample available elements, which leads to a mixed sampling strategy.

Enamel lead concentrations from the summarized studies range from 0.03 to 187 µg/g, with a median concentration of 2.69 µg/g. The violin plot in Figure 2 provides an overview of the enamel lead concentrations, by site, with a y-axis limit of 40 µg/g to better visualize variability within the bulk of the datasets. It should be noted that enamel lead concentrations exceeding 10 µg/g are rare in modern populations, and therefore, cases of high enamel lead concentrations (>10 µg/g) can be considered evidence of likely elevated lead exposure during the short tooth-specific window of enamel mineralization during childhood or adolescence.Footnote 112 For most populations, the mean enamel lead concentration falls below this threshold of exposure, though most sample sets had maximum values exceeding it. While our ability to directly compare studies is limited due to inter-study differences in methodology and element selection, the variability that is evident in enamel lead concentrations highlights the individual differences in risk of childhood lead exposure across populations.

Fig. 2. Violin plot of enamel lead concentrations from archaeological skeletal remains across the Roman Empire, represented by site, prepared by the authors. Concentrations >40 µg/g excluded. Straight line: median values; dotted lines: quartiles.

Among the studies summarized, Moore and colleagues reported remarkably high enamel lead concentrations in teeth belonging to a fetal individual (187 µg/g Pb) and infants (0–2 years; 76.10–99.90 µg/g Pb).Footnote 113 Enamel is less susceptible than bone or dentine to diagenesis; however, under certain conditions, enamel can become diagenetically altered.Footnote 114 It is therefore possible that diagenesis could be responsible for producing these values, particularly given the undermineralized state of developing fetal and infant teeth. However, if biogenic, the incompatibility of such high concentrations with life could be interpreted as further evidence for the role of lead in causing higher rates of juvenile mortality during the Roman period. As described above, the enamel caps for much of the deciduous dentition form in utero, reflecting maternal blood lead levels during pregnancy as well as a potential pregnancy-induced spike in lead remobilization from the skeleton. This work also suggests that the impacts of lead poisoning episodes on ancient morbidity and mortality may be paleopathologically discernable. Moore and colleagues found higher rates of pathological lesions potentially indicative of metabolic diseases (Vitamin C deficiency, Vitamin D deficiency, anemia) among individuals with higher enamel lead concentrations, arguing these conditions could have been caused by lead’s ability to disrupt metabolic processes. Additionally, they suggest that lead could have been a contributing factor to the high infant and juvenile mortality rates of the Roman period, given that there were higher enamel lead concentrations among juvenile individuals compared to adults. It is not clear whether the association between pathological lesions and high lead burdens reported by the authors still exists if the aforementioned outliers are excluded.

Bone lead concentrations, which represent lead exposure in the years before death, ranged from 0.87 to 19,219 µg/g. Data from some of the studies included in Table 4 are represented in Figure 3, with a limit of 200 µg/g to better visualize variability within the bulk of the datasets. The single sample with an outlier concentration of 5,379 µg/g from the study by Erel and colleagues was excluded.Footnote 115 Additionally, entire studies with lead concentrations largely influenced by diagenesis were completely excluded: the study of Martínez-García and colleagues was critiqued for its physiologically improbable trace element concentrations, and Zapata and colleagues concluded that many of their samples were diagenetically contaminated.Footnote 116 Many of the older publications were excluded from the plot because they reported bone concentration means and ranges only, not full data points, illustrating the importance of data transparency.

Fig. 3. Violin plot of bone lead concentrations from archaeological skeletal remains across the Roman Empire, represented by site, prepared by the authors. Straight line: median values; dotted lines: quartiles.

It is very likely that diagenetic contamination could be influencing the concentration of some samples presented in the violin plot in Figure 3, and caution must therefore be exercised when interpreting values. For example, even when excluding outliers, the lead concentrations in the study by De Muynck and colleagues are considerably elevated relative to other studies.Footnote 117 The authors examined lead concentrations and isotope ratios in the site soil and lead artifacts and argued that diagenesis was not the key contributor to bone lead. However, the study’s focus on infant bone, which may be poorly mineralized, could have resulted in an increased susceptibility of samples to diagenesis. This caveat aside, the studies demonstrate considerable variability in the distribution of bone lead concentrations within singular studies, as well as between different sites. This variability highlights the role of individual life factors in different levels of lead exposure. We may tentatively offer the interpretation that urban life posed a higher risk of lead exposure to individuals: the skeletal samples from Rome and London exhibit considerably elevated lead concentrations relative to more rural and/or peripheral imperial regions in present-day Germany, Croatia, and Spain.Footnote 118

Some of the enamel and bone studies took a diachronic approach to examining lead exposure.Footnote 119 Temporally, the studies on western sites documented higher lead concentrations in both human enamel and bone during the Imperial Roman period than in the early medieval period. This is in line with the larger political and economic context: by the late 5th c. CE, the Western Roman Empire had fractured into smaller kingdoms. During the Late Antique to early medieval period, these locales would have largely lacked the imperial systems responsible for centralized and large-scale mining, production, and distribution of lead.Footnote 120 This would have contributed to a decrease in skeletal lead concentrations. The Greek East, which survived this period of tumult, could have feasibly maintained the necessary political and economic infrastructure for lead production and distribution into the early medieval period, but studies have largely neglected this part of the Roman Empire. Degryse and colleagues analyzed goat bones from Turkey, documenting a slight decline in the 4th c. CE, followed by an uptick during the early medieval period.Footnote 121 The authors contextualized this pattern against a larger backdrop of 4th-c. prosperity and 5th- to 6th-c. insecurity: during times of economic abundance and political security, people would have ventured further from town with their herds; during periods of uncertainty, they would have kept those herds closer to town, where the animals would have been exposed to more lead pollution.

Conclusions and future directions

Lead exposure remains a key health and environment issue today and likely would have been an unrealized dimension of morbidity and mortality in the past. To understand how lead was used and how it affected ancient populations, this article has employed a three-pronged approach to examining lead use and exposure during Roman Antiquity, exploring the written, material, and bioarchaeological records. Critically, a key conclusion from this survey is that previous work has often overstated the impacts of Roman lead use, with an excessive focus on sapa, wine, and plumbing as key contributors to exposure that is not adequately supported by the material and bioarchaeological records. Rather, a comprehensive examination of “common” uses of lead and rigorous bioarchaeological study can help to elucidate a more nuanced picture of this ancient lead use and exposure.

Written evidence from the Roman period – the source of information which largely inspired early hyperbolized claims about the impacts of Roman lead use – emphasizes lead as an additive to food and drink, as a versatile component of building and plumbing, as a panacea, and as a common pigment in cosmetics and paint. Indeed, the consideration of written accounts in tandem with archaeological and other physical evidence supports many of these uses of lead, but the written accounts from Pliny, Cato, and Columella of sapa preparation in leaden or stagnum-coated vessels are not adequately corroborated by the material record. Direct analysis of food and beverage remains and indirect chemical analysis of ceramic storage vessels provide mixed evidence for the adulteration of wine and food with lead. That said, limitations of the archaeological record (e.g., salvage, looting, recycling) could partially account for the inconsistency between the written and material records, and perhaps the practice of using lead vessels for sapa production was temporally or regionally circumscribed. Overall, however, evidence from the archaeological record would suggest that sapa and adulterated wine were not leading causes of lead exposure throughout the Roman Empire. Lead pipes represent a similar case of being widely thought of as a contributor to Roman lead exposure. While there are, in this case, abundant written references and archaeological remains that attest to their usage, the extent to which this would have resulted in a contaminated drinking water supply is unclear. Our assessment of comprehensively inventoried houses spanning the Roman Empire provided insights into common uses of lead within the home. Introducing a matrix-based framework, we evaluated Roman domestic lead artifacts from published sites on the basis of frequency and risk. Lead repairs of ceramics are abundant in the archaeological record, though they are seldom commented upon in ancient writings. This likely would have represented a more common source of lead exposure in the domestic sphere.

What is missing from both the written and the material records is a notion of how these lead-use practices affected Roman populations. The written record provides hints in this regard, both by describing diseases reminiscent of lead poisoning and by alluding to lead’s toxicity, but lead’s overall impacts on human health, morbidity, and mortality cannot fully be gathered from these ancient writings. The bioarchaeological record can help to address this gap. Mean and median lead concentrations across studies are not so elevated as to suggest that lead poisoning was as prevalent and widespread as some of the contemporary scholarship on lead and the Roman Empire would suggest. However, Moore and colleagues found compelling associations between metabolic pathological lesions, elevated enamel lead concentrations, and childhood mortality.Footnote 122 Future research on the impacts of ancient lead exposure on individual and population health would benefit from this synergistic perspective.

Interpreting written, material, and bioarchaeological sources of information together and in the context of modern toxicological lead research also exposes lacunae in the existing literature on lead in Roman Antiquity. These areas represent fruitful opportunities for further research on lead in the Roman Empire.

Further research in the domestic sphere

Much contemporary scholarly discussion of ancient lead has focused on adult exposure, particularly among individuals of high socioeconomic status. While adulterated wine and pewter objects would have disproportionately impacted groups of higher to middle socioeconomic status, there is, as discussed above, a relative lack of associated archaeological evidence. Domestic sources of lead, on the other hand, would have contributed more broadly to population exposure and would have posed the greatest detriment to children, whose health and development are more susceptible to lead’s toxic effects. However, lead in the ancient domestic sphere has been under-researched.

A geographic emphasis on the Roman West

Most of the current bioarchaeological research on lead has tended to focus geographically on the Roman West, particularly present-day Britain and Italy. Levels of lead exposure in the western provinces would have likely decreased following the fall of Rome in the 5th c. CE, but our understanding of how lead impacted populations in the Roman East is currently lacking. On a more macroscopic scale, this raises compelling questions about changes in lead mining and manufacturing in relation to broader patterns of societal turbulence, continuity, and change. In addition to examining skeletal lead concentrations at underrepresented eastern sites, future research could also examine the distribution of lead mines and the isotopic provenance of lead artifacts in the Roman East in Late Antiquity.

Methodological improvements in bioarchaeological analysis

Both the validity and the comparative potential of many of the bioarchaeological studies examined here are limited by issues inherent in the bioarchaeological record itself. Differential preservation between and within sites means that studies often employ a mixed sampling strategy with respect to element selection. Many of the studies reporting bone lead concentrations lack data transparency or proper controls for lead diagenesis. Overall, the discipline lacks sample preparation and methodological standardization.Footnote 123 Additionally, diagenesis research on lead contamination specifically is lacking, with research on other elements often co-opted into the study of lead. More research is needed on identifying diagenesis and recovering biogenic information to ensure research published on lead is accurate. This area of research as a whole may benefit from greater use of element mapping approaches (e.g., laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry, synchrotron radiation X-ray fluorescence imaging, scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy) to visualize the extent of diagenetic trace element diffusion.Footnote 124 To mitigate the susceptibility of bone to diagenetic alteration, studies may benefit from sampling dense bones that are less affected, such as the petrous portion or recovered ear ossicles, which would provide a maternal or early life perspective on lead exposure. Such an approach would need to balance the goals of the project with competing considerations, including potential future research targeting these bones (e.g., ancient DNA analysis) and context-specific conservation ethics associated with more invasive sampling.Footnote 125

The use of zooarchaeological or multiple sampling approaches for bioarchaeological studies

To date, bioarchaeological studies have largely focused on human bone or tooth samples. As demonstrated by Degryse and colleagues, the analysis of faunal skeletal material is a potentially fruitful proxy for exploring urban lead exposure and ambient air pollution.Footnote 126 An additional consideration is the ethics of destructive sampling and analysis of human skeletal remains; chemical analysis of zooarchaeological samples is a potential means of addressing these ethical sensitivities.

All bioarchaeological studies on Roman collections have also, to date, focused on either bone or enamel samples, not both. Utilizing a multiple sampling approach of bones with different remodeling rates, bone-tooth pairs, or multiple teeth could provide a longer-term window into changes in lead exposure across the individual lifespan. Micro-sampling techniques could also be employed to investigate short-term shifts in lead exposure.

Although the impact of lead on wider events has sometimes been exaggerated, “Rome’s plastic” was common in civic, industrial, and domestic settings, with significant implications for population health. Research to date has provided valuable documentation of lead use and evidence for lead exposure at individual sites and in specific regions. Further study, integrating multiple lines of evidence and comparing bioarchaeological data across periods and regions, has the potential to provide a wider view of lead and health in ancient Roman society.

Declarations of Interest

None

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the two anonymous readers for their constructive comments on this manuscript. We would also like to thank Dr. Margriet Haagsma and Dr. Jeremy Rossiter for the productive feedback early in the research process that contributed to the direction on household archaeology.