1. Introduction

This paper focuses on telicity, one aspect of a predicate’s event structure (also known as lexical aspect or Aktionsart), which describes the inherent temporal properties of an eventuality. Telicity in linguistics is defined as a lexico-semantic property of predicates indicating whether the denoted event has an inherent endpoint or temporal boundary. Verbs that describe events with an endpoint (e.g., discover, arrive) are called telic, while those that describe events without an endpoint are termed atelic (e.g., sleep, walk). Whereas atelic verbs do not have a final state, telic verbs are characterized as having the potential to transition to a final state, although they do not necessarily imply completeness (e.g., Tenny, Reference Tenny1994; Vendler, Reference Vendler1967; Verkuyl, Reference Verkuyl1972). In this paper, the term ‘telic’ refers to all events that possess an endpoint, including both the accomplishment and achievement verb types in the Dowty–Vendler system (Dowty, Reference Dowty1979; Vendler, Reference Vendler1967). The term ‘atelic’ is used to refer to all events without such an endpoint, including activities, semelfactives and states.

Telic and atelic verbs differ in their subevent structure, as described by Vendler (Reference Vendler1967), in terms of the homogeneity property: Telic verbs have a heterogeneous internal structure consisting of non-identical subevents. In contrast, atelic verbs have a homogeneous internal structure that does not consist of different subevents, but can be divided into identical intervals. Heterogeneity of telic verbs, determined by their event frame involving a change of state (inchoative semantics), can be further specified by the presence of grammatically relevant semantic features in each subevent, including durativity, dynamicity and agentivity (Pustejovsky, Reference Pustejovsky1998).Footnote 1

Linguistically relevant distinctions between telic and atelic predicates have been reported in the literature, and various linguistic tests have been used to distinguish telic and atelic predicates from each other (cf. Dowty, Reference Dowty1979; Vendler, Reference Vendler1967, for an overview). Typical tests include: (1) the temporal adverbial modification test, (2) the conjunction test and (3) the ‘almost’ modification test.Footnote 2 It has been noted that these tests are restricted in their cross-linguistic application (Borik, Reference Borik2006). Thus, although specific tests might be useful for determining telicity in one language, the same test might not be usable for determining telicity in another language (e.g., Rathmann, Reference Rathmann2005).

Furthermore, it has been shown that the same verb may be interpreted as telic or atelic, meaning that verbs can shift between verb categories (the process sometimes termed ‘frame alternations’) depending on the context in which the verb appears (Levin, Reference Levin1993). Thus, telicity may not only arise from the lexical semantics of a verb itself (i.e., inherently telic verbs), but also from the interaction of an atelic verb with other morpho-syntactic elements in a sentence (Krifka, Reference Krifka, Bartsch, van Benthem and van Emde Boas1989, Reference Krifka and Rothstein1998). This form of compositional telicity, whereby an atelic verb is coerced into a telic meaning, may result from the involvement of directional phrases (e.g., run to the store), resultative phrases (e.g., sweep the floor clean) or phrases including resultative verb particles (e.g., eat up). Also, the quantificational semantics of the object argument may lead to a telic reading (e.g., eat a piece of cake) (e.g., Krifka, Reference Krifka, Bartsch, van Benthem and van Emde Boas1989, Reference Krifka and Rothstein1998; Ramchand, Reference Ramchand2008; Schulz, Reference Schulz, Syrett and Arunachalam2018; van Hout, Reference van Hout, Greenhill, Hughes, Littlefield and Walsh1998).

In sign languages, the event structure reflected in verbs and their arguments is, to some degree, systematically reflected in the formation of the relevant signs. Based on observations in American Sign Language (ASL), Wilbur (Reference Wilbur2003, Reference Wilbur and Quer2008, Reference Wilbur and Brentari2010) noted an overt systematic mapping between semantic components of events and their morphophonological representations, formulated as the Event Visibility Hypothesis (EVH). For instance, Wilbur observed that telic and atelic verb signs in ASL are characterized by different movement profiles. Telic signs involving an inherent event endpoint are produced with a sharper ending to a stop resulting from either (1) a change of handshape aperture (open/closed, closed/open), (2) a change of hand orientation or (3) an abrupt stop at a location in space or contact with a body part (change in setting or location). This marking of an endpoint was analyzed by Wilbur (Reference Wilbur2003, Reference Wilbur and Quer2008) as an EndState morpheme. Atelic events lack an EndState morpheme, because while they can, in principle, be terminated, they cannot be completed (because of a lack of final state/inchoative semantics). Atelic signs are phonologically represented either by a (repeated) path movement (over a straight or curved line) or do not show any (path or internal/local) movement at all (i.e., are static at a location in signing space). An example from ASL is the verb sign TO-STARE, which is held in its position and orientation; movement to and from this position is considered epenthetic within the syllable structure (Wilbur, Reference Wilbur, van Oostendorp, Ewen, Hume and Rice2011; Wilbur, Reference Wilburin press). Figure 1 represents examples of a telic and an atelic verb in Austrian Sign Language (ÖGS).

Figure 1. Examples of a telic and an atelic verb in ÖGS. In (A), the verb ‘walk’ is presented, showing repeated straight forward movements (repeated three times), lacking endpoint marking. In (B), the verb ‘arrive’ is illustrated, showing a single path movement toward the signer’s non-dominant hand (i.e., movement is not repeated), indicating endpoint marking (from the online database LedaSila – Lexical Database for Sign Languages; http://ledasila.aau.at; Krammer et al., Reference Krammer, Bergmeister, Dotter, Hilzensauer, Okorn, Orter and Skant2001).

Telic and atelic verbs differ in both the semantics/event structure, as well as phonological features and syllable structure (Malaia et al., Reference Malaia, Ranaweera, Wilbur and Talavage2012). Within the Prosodic Features branch of Brentari’s prosodic model (Brentari, Reference Brentari1998), telic signs have a second timing slot that is phonologically contrastive with the first timing slot, while atelic signs’ timing slots are occupied by homogeneous articulatory productions.

The EVH posits that spatiotemporal patterns of sign production (morpho-phonological structure of the sign) map to (conceptual) event structure denoted by the sign. The EVH is fundamentally a linguistic hypothesis about morphophonological patterns, not a claim about general iconicity.Footnote 3 Specifically, the EVH proposes the following:

-

1. Semantic components of events systematically map to specific phonological features in the visual modality (across sign languages). For example, path movement maps to aspectual/Aktionsart marking of an event in the visual modality; rapid deceleration marks end-states (visible also in handshape change, orientation change or contact between dominant and non-dominant articulators).

-

2. These mappings are consistent and built from universally available physics of motion and geometry of space, not ad hoc iconic representations. The EVH identifies compositional structure in predicate signs that had not been previously recognized.

-

3. Critically, the EVH removes these patterns from the domain of ‘iconicity’, as that term is often used to mean ‘not linguistically analyzable’. Instead, the EVH demonstrates that what appears iconic (especially to non-signers) is actually a systematic, rule-governed linguistic pattern. Thus, the EVH represents a linguistic analysis of morpho-phonological patterns rather than a broad cognitive claim about iconicity.

The EVH was developed as an empirical generalization from observations of ASL verb structure (Wilbur, Reference Wilbur2003, Reference Wilbur and Hurch2005, Reference Wilbur and Quer2008, Reference Wilbur and Kenstowicz2009) and has since been tested across multiple unrelated sign languages: ASL (tested by Wilbur, Reference Wilbur2003, Reference Wilbur and Hurch2005, Reference Wilbur and Quer2008, Reference Wilbur and Kenstowicz2009; Malaia & Wilbur, Reference Malaia and Wilbur2011; King & Abner, Reference King and Abner2018); Croatian Sign Language (HZJ) (tested by Milković, Reference Milković2011; Malaia et al., Reference Malaia, Wilbur and Milković2013); ÖGS (tested by Schalber, Reference Schalber2004, Reference Schalber2006; Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Strutzenberger, Schwameder, Wilbur, Malaia and Roehm2021; Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Fessl, Wilbur, Malaia, Wiesinger, Schwameder and Roehm2023b); Italian Sign Language, Sign Language of the Netherlands and Turkish Sign Language (tested by Strickland et al., Reference Strickland, Geraci, Chemla, Schlenker, Kelepir and Pfau2015); for discussion, see also Malaia and Milković (Reference Malaia, Milković, Quer, Pfau and Herrmann2021).

The EVH is proposed to apply broadly across sign languages, with the expectation of principled variation in implementation within a specific sign language. This variation operates at two levels:

-

1. Semantic component selection: Different sign languages may select different semantic components to encode the same concept. For example, the sign SKI can represent either the ‘activity of skiing’ (movement of skis along a path) (atelic construal), or ‘put ski pole into ground/snow’ (telic construal). Both are linguistically valid; the difference lies in which component of the event the language chooses to encode, not in how the mapping works once that choice is made. Note that ‘put ski pole in ground/snow’ can be repeated for a derived atelic representation.

-

2. Phonological implementation: Sign languages may use different spatiotemporal motion patterns (phonological features) from their inventory to mark the same semantic distinction. For instance, ASL marks the endpoint of ARRIVE with a path movement ending abruptly. ÖGS marks the same endpoint with a hand orientation change. Both languages use endpoint marking for telic events, but select different phonological features from their respective inventories.

The hypothesis has both descriptive and predictive components: (1) descriptively, it characterizes observed patterns in how sign languages encode event structure; (2) predictively, it anticipates that sign languages will recruit kinematic features systematically for marking, though specific implementations may vary based on each language’s phonological and morphemic/grammatical inventory. Counterevidence to the EVH would require a sign language to display a fundamentally different semantic–phonological mapping pattern, like using handshape (rather than movement patterns) as the primary marker of telicity; systematically marking atelics with endpoint morphology and telics without it; or showing no consistent correlation between kinematic features and event structure distinctions.

Phonological marking of endpoint or boundary was not only observed for telic verb signs, but also for scalar adjectives in ASL lacking closed upper boundaries (like far) in combination with degree modification with too (e.g., too far to walk) (Wilbur et al., Reference Wilbur, Malaia, Shay, Aloni, Kimmelman, Roelofsen, Sassoon, Schulz and Westera2012), as well as for count nouns in ASL (referring to entities with physical boundaries, e.g., ball, coin) (Kuhn et al., Reference Kuhn, Geraci, Schlenker and Strickland2021). Additionally, the semantic–phonology mapping was observed for an ASL ‘resultative’ construction, in which context atelic States obtain telic meaning with added phonological movement and a ‘final state’ (Kentner, Reference Kentner2014; Wilbur, Reference Wilbur2003). Extensions of the EVH to include predicate adjectives led to a more general Visibility Hypothesis for the manual component of the sign (Wilbur et al., Reference Wilbur, Malaia, Shay, Aloni, Kimmelman, Roelofsen, Sassoon, Schulz and Westera2012):

Sign languages express the boundaries of semantic scales by means of phonological mapping.

Previous studies testing the EVH revealed that the majority of the signs evaluated for phonology–semantics mapping exhibit the systematic event visibility hypothesized by the EVH, with some potential exceptions (e.g., in ÖGS, Schalber, Reference Schalber2006; in ASL, Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Kocab, Sims and Wagner2019). In the studies published to date, a small set of signs does not exhibit the expected mapping, in that either evaluated telic verbs do not manifest phonological/articulatory EndState morphemes, or semantically atelic verb signs appear to manifest EndState morpheme articulation endpoint marking.Footnote 4 Note, however, that single-sign exceptions do not falsify the EVH, just as irregular plurals in English (children, oxen, sheep) do not invalidate the regular plural rule. Linguistic patterns always allow exceptions due to language contact, historical change and dialectal variation. This suggests that event visibility is a generally robust phenomenon; however, rigorous methods of both the semantic–syntactic analysis of event structure (which is variable across languages) and articulation analysis (e.g., high-temporal-resolution motion capture) need to be employed to clarify whether the apparent exceptions are due to cross-linguistic variability in verb semantics, syntax of event structure or, possibly, individual variability and even historical change in event structure of verb signs.

Existing cross-linguistic analyses of event structure in sign languages (Wilbur, Reference Wilbur and Quer2008) show that there are sign language-specific differences in the following: (1) how the grammatical category encompassing telic–atelic distinction is realized in each languageFootnote 5, (2) which root signs can combine with language-specific EndState morphemes and (3) how the EndState morpheme is articulated in the particular sign language (i.e., given the phonological inventory of motion, and phonotactic constraints, especially for bimanual signs). The two languages that have been compared in most detail in terms of event structure mapping are American Sign Language (ASL) and Croatian Sign Language (HZJ), in which the distinction between telic and atelic verb classes is realized in different ways. For example, while ASL lexical verbs are invariant as to the presence/absence of EndState morpheme in the root of their phonological form (Wilbur, Reference Wilbur2003), in HZJ, a morphological process (i.e., modification of movement) can be used to produce either telic or atelic verb signs with similar lexical semantics from one root; in terms of articulation, telic signs are characterized by shorter, sharper movement than atelic signs (Milković, Reference Milković2011). In particular, in ASL, telics and atelics are divided into classes based on their phonological form (an example of a telic verb is SEND, involving handshape change, and an example of an atelic verb is PLAY, showing a repetitive path movement, Wilbur, Reference Wilbur and Brentari2010), and in HZJ most telic verbs show a shorter, sharper movement compared to atelic signs (an example is the atelic sign ERASE and the telic sign TO-HAVE-ERASED, Malaia & Milković, Reference Malaia, Milković, Quer, Pfau and Herrmann2021). Empirical evidence for the EVH has been provided by motion capture data showing systematic kinematic distinctions between telic and atelic predicates. In ASL, the endpoint of the event in telic signs is marked by a significantly faster deceleration at the end of the verb, in contrast to atelic signs (Malaia & Wilbur, Reference Malaia and Wilbur2011). In HZJ, faster deceleration at the sign end, as well as greater peak velocity was observed for telic signs compared to atelic signs (Malaia et al., Reference Malaia, Wilbur and Milković2013).

ÖGS, the focus of the present study, has been examined in the context of the EVH by Schalber (Reference Schalber2004, Reference Schalber2006), who provided descriptive data supporting the EVH for a set of ÖGS predicates. In Schalber’s analysis, the phonological articulation of the verbs using the Prosodic Model of Brentari (Reference Brentari1998) was correlated with the conceptual event structure of the predicates, determined according to their subevent structure – that is, according to the presence of an endpoint and change of state (Transitions) in the phonological form, or the lack thereof (in verb signs denoting States and Processes). Schalber reported that telic verbs in ÖGS marked the end-state by rapid deceleration to a complete stop, realized in changes of hand orientation, handshape or setting; such marking of end-state was not found in atelic signs. Additionally, ÖGS was noted to use specific non-manual markings for distinguishing predicate event types. Specifically, Schalber (Reference Schalber2004, Reference Schalber2006) described a correlation between event structure and two adverbial mouth non-manuals: Transitional-mouth (T-mouth) non-manual scoping over the semantic endpoint and involving a change in mouth position, exclusive to telic predicates; and Posture-mouth (P-mouth) non-manuals, held for the sign’s duration, which occurred with both telic and atelic verb signs, and modified the entire event.

Schalber (Reference Schalber2006) also reported a few possible exceptions to the EVH. For instance, some sign roots did not allow for overt representation of event structure by an EndState morpheme, instead requiring the construction of a complex predicate (e.g., a classifier construction) or the use of the aspect marking sign fertig (finish) expressing completion. For instance, for expressing the telic event ‘to dig a grave’, the atelic verb DIG, which by itself cannot be modified to indicate an end-state, is combined with the aspect marker FINISH. Likewise, Schalber notes that the sign for SKI, which shows the plunging of ski sticks into the ground/snow, must add a separate sign FINISH to indicate that the skier crossed the finish line. However, Schalber (Reference Schalber2006) pointed out that the failure to mark event structure could be accounted for by both the phonological properties of the stem sign and the subtle differences in sign semantics in ÖGS as compared to Austrian German or English.

The difference in motion features between a set of telic and atelic signs in ÖGS has been investigated in more detail by motion capture and electromyography (EMG). These studies showed that telic ÖGS signs exhibit higher acceleration, jerk and deceleration, along with shorter durations, compared to atelic signs (Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Strutzenberger, Schwameder, Wilbur, Malaia and Roehm2021, Reference Krebs, Malaia, Fessl, Wiesinger, Wilbur, Roehm, Schwameder, Calzolari, Kan, Hoste, Lenci, Sakti and Xue2024, Reference Krebs, Fessl, Wilbur, Malaia, Wiesinger, Schwameder and Roehm2023b). Telic verbs also had ~2.5 times longer holds at the sign’s end. EMG data revealed greater upper arm muscle activity for telic verbs, with increased biceps activation during the sign and triceps activation during the hold phase, while atelic verbs showed higher forearm muscle activity due to repeated movements (Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Fessl, Wilbur, Malaia, Wiesinger, Schwameder and Roehm2023b). Further investigation additionally revealed more regular and less variable movement patterns for telic verbs compared to atelic verbs in ÖGS, as well as temporally precise muscle coordination, synchronization and stability involved in the production of telic verbs in ÖGS (Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Harbour, Malaia, Wilbur, Martetschläger, Schwameder and Roehm2025).

Interestingly, motion features similar to those observed for telic signs have been reported to play a role in non-linguistic visual action comprehension (cf. Blumenthal-Drame & Malaia, Reference Blumenthal-Drame and Malaia2018, for review). For example, studies of visual event segmentation show that event boundary identification (i.e., identification of action start and end times) is highly correlated with increases and decreases in speed (or acceleration and deceleration) of agents in a visual scene (Zacks et al., Reference Zacks, Swallow, Vettel and McAvoy2006). Furthermore, the boundary marking observed for telic signs was also observed during the use of pro-speech gestures, that is, gestures produced by hearing non-signers, which are used instead of spoken words and thus often contribute to the semantics of an expression (Schlenker, Reference Schlenker2020). In particular, Schlenker (Reference Schlenker2020) observed visual boundary markings for gestures that expressed telic events but not for gestures expressing atelic events. King and Abner (Reference King and Abner2018) compared atelic/telic ASL signs produced by signers with gestures produced by hearing non-signers who were asked to gesturally express the meaning of telic and atelic predicates without using speech. They observed that hearing non-signers produced boundaries for telic, but not atelic events. Specifically, telics showed a higher boundedness score (i.e., an abrupt stop or deceleration, handshape change or contact at sign end; assessed by a 7-point scale) and atelics received a higher repetition score (i.e., repeated movement across space, opening, closing or changing of handshape; assessed by a 7-point scale). Although these differences were observed for both signs and gestures, the effects were stronger in ASL than in gesture (King & Abner, Reference King and Abner2018). Moreover, it has been shown that hearing non-signers can infer aspectual meaning from sign language stimuli and identify event structure (telic/atelic) in unknown sign language verbs, associating signs involving a visual boundary with telic events and signs without a visual boundary with atelic events (Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Wilbur, Roehm and Malaia2023a; Kuhn et al., Reference Kuhn, Geraci, Schlenker and Strickland2021; Strickland et al., Reference Strickland, Geraci, Chemla, Schlenker, Kelepir and Pfau2015). An event-related potential (ERP) study investigating the neural processing mechanisms involved when hearing non-signers classify telic and atelic verb signs (in a two-choice lexical decision task) revealed early effects reflecting differences in perceptual processing (i.e., differences in perceived motion profiles of telic vs. atelic signs), and later lexical-retrieval-driven effects reflecting integration of perceptual features with linguistic concepts in the participants’ native language (Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Wilbur, Roehm and Malaia2023a).

Note, however, that the phonological form of telic and atelic verb signs is linguistically determined, that is, motivated by the phonological inventory of each sign language, as well as its grammar. Schalber (Reference Schalber2006) found a different realization of end-state marking of equivalent predicates in ASL and ÖGS. For example, while ASL marks the end-state of ‘arrive’ with the phonological feature [direction] (path movement ending abruptly), ÖGS uses the feature [supination] (orientation change). Thus, although both ASL and ÖGS use the phonological features [direction] and [supination] to mark endpoints in telic signs, the two languages differ in which verbs employ which form of endpoint marking.

Furthermore, although both Deaf signers and hearing non-signers perceive telic–atelic differences visually, only signers process them linguistically (Malaia et al., Reference Malaia, Ranaweera, Wilbur and Talavage2012). This suggests that perceptual features for non-linguistic event segmentation have been integrated into sign language as linguistic elements (cf. Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Malaia, Siskind and Wilbur2022; Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Wilbur, Roehm and Malaia2023a; Malaia et al., Reference Malaia, Wilbur and Weber-Fox2012).

The present study aims to contribute to the research on telicity and the EVH in sign languages by conducting a systematic analysis of ÖGS verbs, combining semantic test results with phonological analysis. While it has been shown that the EVH can be applied to some ÖGS predicates (Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Strutzenberger, Schwameder, Wilbur, Malaia and Roehm2021; Schalber, Reference Schalber2004, Reference Schalber2006), only a small set of verbs has been analyzed (e.g., Krebs et al. [Reference Krebs, Strutzenberger, Schwameder, Wilbur, Malaia and Roehm2021] analyzed 10 atelic and 10 telic verbs). Moreover, while the telic–atelic distinction was reported for a number of sign languages, most of these reports did not assess telicity using semantic tests, which are critical for providing objective, systematic evidence for specific grammatical structures. The present study investigates the telic–atelic distinction in ÖGS with regard to a larger set of verbs in a systematic way, that is, by using specific linguistic tests previously used for other (sign) languages to determine telicity. This way, it can be determined whether the systematic mapping between phonological form and event structure holds even when a larger set of verbs covering a wider part of the ÖGS lexicon is used, and whether potential contradictions to the EVH can be observed. Note that, because we aim to investigate whether the event structure is systematically reflected in the phonological form of verb signs in ÖGS, in the following, we only refer to inherently telic verbs, that is, verbs whose telicity is determined by the verb lexeme itself (and thus is not determined at the verb phrase level) (Tenny, Reference Tenny1994; Vendler, Reference Vendler1967; Verkuyl, Reference Verkuyl1972). Additionally, by providing information about the phonological features reflecting certain aspects of event structure in ÖGS (such as indicating the presence or absence of endpoint marking), this study provides important knowledge about the ÖGS verb system.

2. The present study

The present study tested whether the telic–atelic semantic distinction is encoded in ÖGS verb signs through systematic morpho-phonological patterns, specifically examining whether verbs exhibit the kinematic endpoint-marking predicted by the EVH. Four signers judged a list of verbs according to semantic tests that had been previously used in other sign and spoken languages to determine telicity (outlined below). These results were then correlated with the phonological structure of the verbs produced by one of the signers who participated in the interview. Based on the EVH, we expected a mapping pattern between articulatory marking of an endpoint and telic semantics in ÖGS verb signs, as compared to iterative or stative marking for atelic verb signs.

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Semantic tests for investigating telicity in ÖGS

To classify the ÖGS verbs as telic or atelic, detailed interviews with Deaf signers were conducted.Footnote 6 Signers were asked to judge whether a particular verb can occur in specific phrase and sentence contexts and, if yes, how the resulting constructions can be interpreted as to their fine-grained meaning. Four linguistic tests for examining telicity were used in the present study: (1) the temporal adverbial modification test, (2) the conjunction test, (3) the ‘almost’ modification test and (4) the ‘stop/finish’ test. These tests have been used previously for testing telicity in ASL (Malaia & Wilbur, Reference Malaia and Wilbur2011); however, as no cross-linguistic assumptions should be made for linguistic test applicability in signed or spoken languages, their use in ÖGS elicitation requires elaboration on adaptations made to the original versions (Borik, Reference Borik2006).

2.1.1.1. The temporal adverbial modification test

The temporal adverbial modification test examines the co-occurrence with the temporal expression ‘in an hour’ contrasted with ‘for an hour’ (Dowty, Reference Dowty1979; Verkuyl, Reference Verkuyl1972). For a number of languages, it has been noted that atelic verbs combine with durative adverbs like ‘for an hour’, expressing that a specific activity lasted an hour. Telic verbs, on the other hand, combine with time-reference adverbials like ‘in an hour’, meaning that an activity took an hour, that is, was completed within an hour. Some telic verbs can be combined with durative adverbs. However, this combination (if possible) leads to an iterative interpretation (i.e., it results in conveying the meaning of someone doing something repeatedly for an hour). In the present study, signers were asked whether the event expressed by the verb can be combined with ‘do for an hour’, and if yes, how this combination could be interpreted (i.e., whether something is done for an hour or is done repeatedly for an hour). In addition, signers were asked whether the event expressed by the verb could be combined with the adverbial phrase ‘complete an action in an hour’.

2.1.1.2. The conjunction test

The conjunction test (Verkuyl, Reference Verkuyl1972, Reference Verkuyl1993) examines verb meaning in temporal contexts, such as ‘she/he did something on Sunday and on Monday’. If the sentence can only be interpreted as denoting two discrete events, the verb is considered telic. If the sentence is ambiguous and could be interpreted as either denoting two discrete events or one long event, the verb is considered atelic. In the present study, signers were asked to explain how the verb signs would be interpreted in such sentence contexts, that is, whether the sentence could only be interpreted as describing two discrete events, or whether the sentence could also describe one long event.

2.1.1.3. The ‘almost’ modification test

The ‘almost’ modification test has been used in sign language research as a means to identify telic verbs (Brentari, Reference Brentari1998; Smith, Reference Smith2007). This test involves combining a verb with the adverb ‘almost’, which yields distinct interpretations for telic and atelic verbs: Specifically, when ‘almost’ is paired with an atelic verb, such a combination yields a singular interpretation indicating that the action never commenced (‘one did not start doing X’; the unrealized inceptive; Liddell, Reference Liddell, Drogo, Mishra and Testen1984). When the adverb ‘almost’ is combined with a telic verb, two potential interpretations typically arise: Either that the action failed to commence at all, or that the action commenced but remained incomplete (‘one did not complete doing X’; the incompletive; Liddell, Reference Liddell, Drogo, Mishra and Testen1984; Smith, Reference Smith2007). In our current investigation, signers were prompted to articulate how a verb could be interpreted when combined with the ÖGS sign for ‘almost’ (German ‘fast’), and whether two interpretations were possible. In particular, we sought to ascertain whether the verb, when combined with ‘almost’, could convey the notion that the event ‘wasn’t started/didn’t start’, as well as whether it could mean ‘started but was stopped before completion’.

2.1.1.4. The ‘stop/finish’ combinability test

The final test that was used in the study was the ‘stop/finish’ combinability test. In ASL, telic signs can be combined with the sign finish expressing a ‘completive’ meaning (Fischer & Gough, Reference Fischer and Gough1999). In contrast, when atelic verbs combine with finish, they do not convey the meaning of ‘completed’, but rather the meaning of ‘already, in the past’; alternatively, atelic verb stems combine with the sign stop, yielding the meaning ‘to stop/quit something’ (Malaia & Wilbur, Reference Malaia and Wilbur2011). In the present investigation, signers were queried regarding each verb’s combinability with the ÖGS sign fertig (finish). In ÖGS, this sign can express several meanings depending on the context. Amongst possible interpretations of fertig are ‘finish’; ‘already, in the past’; ‘stop/quit something’ (Okorn et al., Reference Okorn, Skant, Bergmeister, Dotter, Hilzensauer, Hobel, Krammer, Orter and Unterberger2001; Schalber, Reference Schalber2006). Specifically, during elicitation, we asked the signers to decide whether a verb could combine with fertig, expressing the meaning of ‘done/completed’, and/or ‘to quit/stop doing something’ (e.g., because someone is tired, or gets interrupted). We also asked about the combinability of the verb with the ÖGS sign stoppen, meaning ‘to quit/stop doing something’.

Individual signers were invited to participate in an interview aimed at exploring various facets of the meaning associated with a list of verbs (N = 119), using the tests described above. The verbs were chosen based on the phonological form known from published (Krammer et al., Reference Krammer, Bergmeister, Dotter, Hilzensauer, Okorn, Orter and Skant2001) and unpublished data: About half of the verbs show phonological endpoint marking, and the other half lack endpoint marking. The verb list contained activity, state and achievement verbs, but no transitive accomplishments, as only isolated verbs were presented.Footnote 7 Conducted in ÖGS by one author, sessions were recorded for analysis, totaling 23.5 hours. The entire conversation was recorded on video to facilitate subsequent analysis of responses and sign language productions. Each participant visited the lab twice, with the interview sessions held on two separate days. During the second meeting, any unresolved questions from the initial session were addressed and discussed further.

2.1.2. Participants

Four Deaf ÖGS signers (three females) with a mean age of 55 years (range: 51–59 years) took part in the interview study. All participants reside in the Salzburg area; one was raised in Upper Austria, another in Salzburg and two in Styria. They were either born deaf or lost their hearing early in life, had hearing parents and acquired ÖGS between 4 and 7 years of age. All use ÖGS in their daily life, are certified teachers of ÖGS and members of the Austrian Deaf community.

2.1.3. Semantic test results and phonological analysis

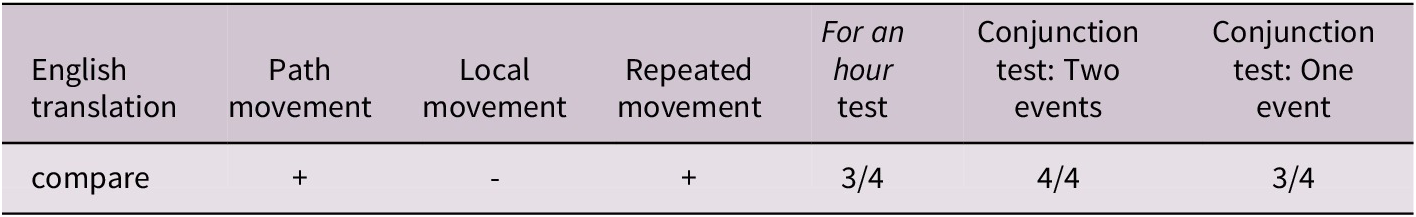

For each verb, the responses regarding all four tests were listed in a table summarizing the number of signers who responded that a certain verb can be used in a specific semantic context, which was reported as ‘4/4’ meaning ‘4 out of 4 persons’, ‘3/4’ meaning ‘3 out of 4 persons’, ‘2/4’ meaning ‘2 out of 4 persons’, ‘1/4’ meaning ‘1 out of 4 persons’ or ‘0/4’ meaning ‘0 out of 4 persons’. Participants consistently provided similar, clear judgments regarding two of the administered tests, namely the ‘for an hour’ test and the conjunction test. The outcomes of these two tests were thus considered suitable for classifying the verbs with respect to telicity (telic/atelic). The other tests used, that is, the ‘within an hour’ test, the ‘almost’ test and the ‘stop/finish’ test, did not give clear results for the telic–atelic distinction and thus were not further used for categorizing the signs (for more information about why these tests were not used in the present study for determining telicity, see the Discussion section 3.6).

The test results were evaluated according to the expectations based on prior literature. For atelic verbs, positive responses were anticipated for the ‘for an hour’ test and both options of the conjunction test (i.e., the two individual events reading as well as the one long event reading). Conversely, for telic verbs, a negative response was expected for the ‘for an hour’ test, while a positive response was expected for the two individual events reading and a negative response for the single long event reading in the conjunction test. The judgment data were analyzed against these expectations.

Additionally, the verbs were grouped according to the clarity of the test results, that is, whether both tests provide a ‘clear’ result (all four participants gave the same judgment), or whether one of the tests or both show a ‘relatively clear’ result (three of the signers gave the same judgment) or a ‘mixed’ pattern (two of the signers gave the same judgment, the other two gave the contrary judgment). It was also checked whether the test results of both tests (‘for an hour’ and conjunction test) contradict or corroborate each other. In cases in which the results of the semantic tests did not point in the same direction or revealed mixed results, the data of the individual interview sessions were examined in detail to determine the source of variability in judgments. More concretely, we went back to the interview recordings and analyzed the discussion and the signers’ explanations.

To evaluate the correlation between the results of the semantic tests and the phonological structure of the signs, one of the interviewees, a right-handed female participant, was asked (some time after the interview took place) to produce the verb signs. The signs were elicited by a list of written glosses. These sign productions were video recorded for further analysis. The participant who was filmed is fully representative of the dialect of all participants who took part in this study (i.e., the Salzburg dialect of ÖGS). The phonological structure of the verbs was analyzed, focusing on whether endpoint marking was present and, if so, which form of endpoint marking was utilized. Verbs were judged as having phonological endpoint marking if the form includes changes in handshape, hand orientation or location (with or without contact with the non-dominant hand or another body part), as well as combinations of these markings. Verbs lacking these phonological characteristics (i.e., showing path movement(s) or no movement at all) were described as lacking endpoint marking. Additionally, the movement component and syllable structure of the signs were examined by determining whether the verb was produced by a path movement and/or a local movement, as well as whether or not the sign involved repeated movement. One of the authors, a fluent ÖGS signer, conducted the phonological analysis and determined whether a verb showed endpoint marking or not. Both the semantic and the phonological analyses are discussed in detail below.

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Correlating telicity and phonological form of ÖGS signs

The phonological analysis revealed that among the 119 signs, 62 signs exhibited endpoint marking, while 57 signs did not. Endpoint marking was manifested through various means, including changes in handshape, hand orientation or location (with or without contact with the non-dominant hand or another body part). Sometimes, endpoint marking was achieved through a combination of these features, such as a change in hand orientation coupled with a change in location with or without contact, a change in handshape along with a change in location with or without contact or a change in handshape along with a change in hand orientation (Figure 2).Footnote 8

Figure 2. Examples for the different forms of endpoint marking observed in the present study: (A) change of handshape (erfinden, invent), (B) change of hand orientation (entscheiden, decide), (C) change of location without contact at sign end (töten, kill), (D) change of location with contact at sign end (entdecken, discover), (E) change of hand orientation and change of location without contact at sign end (ankommen, arrive), (F) change of hand orientation and change of location with contact at sign end (aufstehen, get up), (G) change of handshape and change of location without contact at sign end (schicken, send), (H) change of handshape and change of location with contact at sign end (zugeben, admit), (I) change of hand orientation and change of handshape (stehlen, steal).

Most of the signs lacking endpoint marking were signed with a repeated movement. The signs without repeated movement lacking endpoint marking either displayed a directed path movement or no movement at all (Figure 3).Footnote 9

Figure 3. Examples for different forms of atelic signs lacking endpoint making: (A) repeated path movement (schreiben, write), (B) no manual movement (schlafen, sleep), (C) single path movement (reisen, travel).

Interestingly, two signs with endpoint marking also exhibited repeated movement: The second part of the composite sign abmelden (sign off), which is signed like the sign anmelden (sign in) with small, repeated path movements of the dominant hand making repeated contact with the back of the non-dominant hand. Additionally, the sign for aufholen (catch up) featured repeated local movement, with the wrist of the dominant hand repeating a left–right rotating motion simultaneously within a single non-repeated linear forward path movement.Footnote 10

2.2.2. Signs with endpoint marking and telic event structure

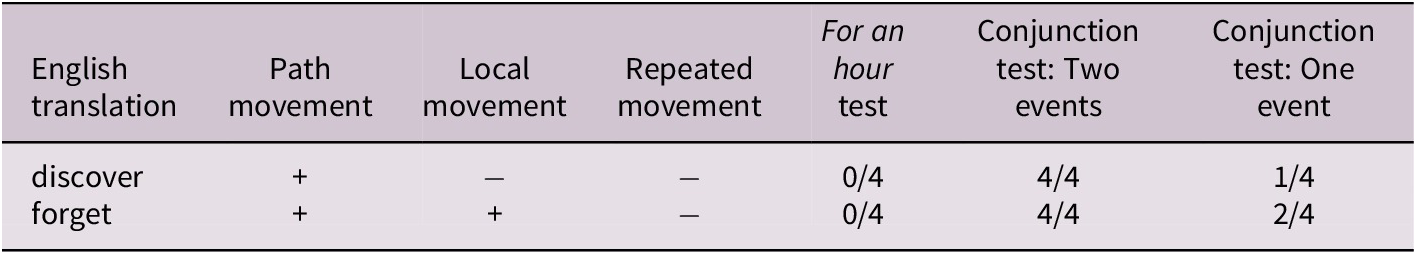

The study identified 27 signs with endpoint marking that were unequivocally categorized as telic by both semantic tests (see Table 1). Additionally, 12 signs with endpoint marking were clearly identified as telic by the conjunction test, with either a relatively clear telic result (N = 9) or a mixed pattern (N = 3) observed in responses to the temporal modification test (see Table 2). Two signs were clearly identified as telic by the temporal adverbial modification (‘for an hour’) test, but either exhibited a relatively clear telic result (N = 1) or a mixed pattern (N = 1) in the conjunction test (see Table 3).

Table 1. Telics: Clear on both tests (N = 27)

Table 2. Telics: Conjunction test clear, ‘for an hour’ test relatively clear (N = 9) or shows a mixed pattern (N = 3)

Table 3. Telics: ‘For an hour’ test clear; conjunction test relatively clear (N = 1) or shows a mixed pattern (N = 1)

For 10 of the signs with endpoint marking, both tests were not entirely clear: For four signs, both tests are relatively clear; for another five signs, the conjunction test shows a relatively clear result, and the ‘for an hour’ test shows a mixed pattern, and for one sign, both tests show a mixed pattern (see Table 4). These signs showing endpoint marking were categorized as telic because the conjunction test provided relatively clear results toward a telic meaning. Only the verb CHANGE shows a mixed pattern for both tests. The interview data show that, besides the telic reading, the verb CHANGE may get an atelic interpretation depending on the context in which the verb is used (for more details, see the Discussion section).

Table 4. Telics: Both tests not entirely clear; both tests relatively clear (N = 4), conjunction test relatively clear and ‘for an hour’ test shows a mixed pattern (N = 5), both tests show a mixed pattern (N = 1)

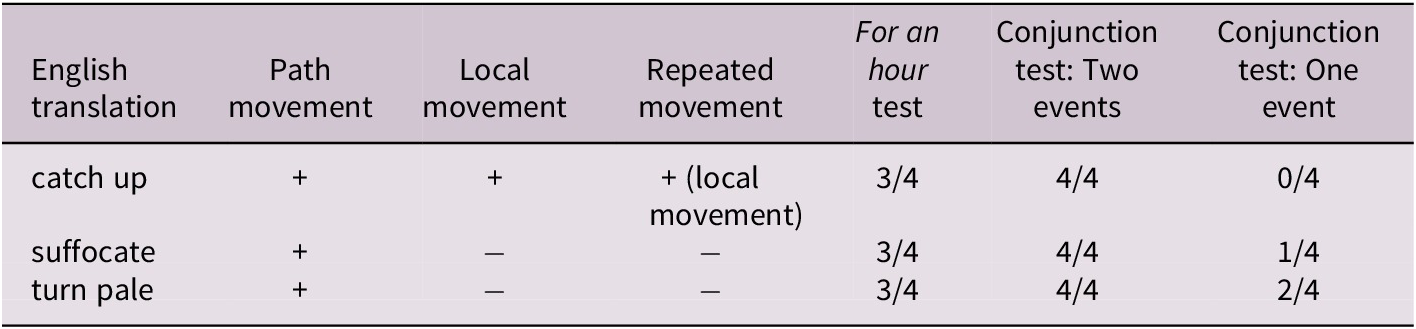

Additionally, for three of the signs with endpoint marking, the ‘for an hour’ test is pointing toward an atelic event structure (relatively clear result; 3/4), while the conjunction test either indicated a clearly telic result (N = 1), a relatively clear telic result (N = 1) or a mixed pattern (N = 1) (see Table 5). These verbs with endpoint marking were classified as telic because for two of the signs (CATCH-UP and SUFFOCATE), the conjunction test provides a clear or relatively clear result toward a telic meaning. For the verb TURN-PALE a mixed result was observed for the conjunction test. The interview session revealed that this sign can show an argument structure alternation (for more details, see the Discussion section below). Note that the cases where the two semantic tests revealed inconsistent results were rare and therefore seem to be driven by the properties of particular verbs.

Table 5. Telics: Both tests not entirely clear: ‘For an hour’ test more atelic event structure (3/4), and the conjunction test either clearly telic (N = 1), relatively clearly telic (N = 1), or shows a mixed pattern (N = 1)

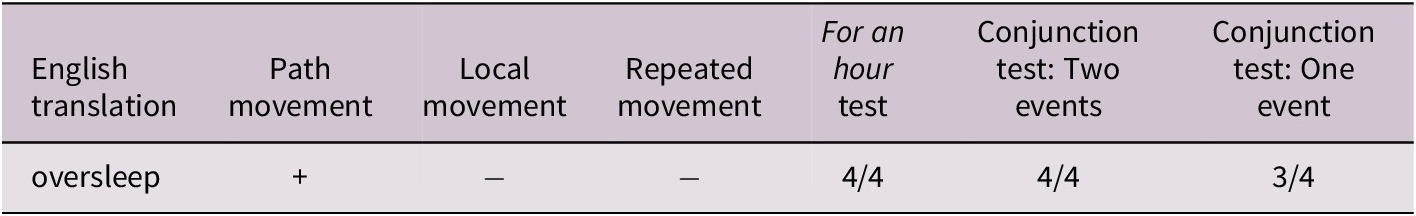

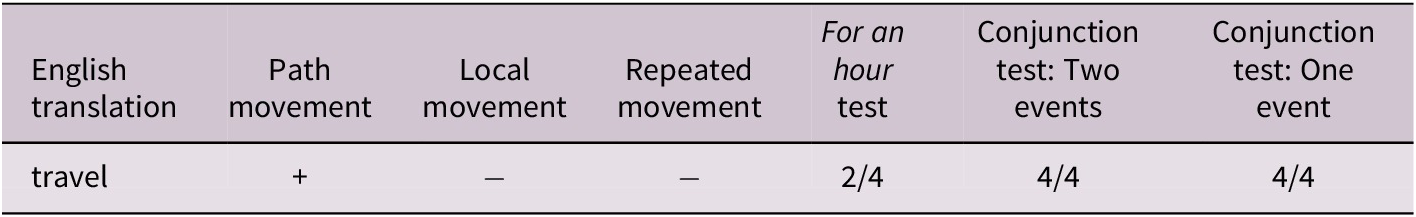

2.2.3. Signs without endpoint marking with atelic event structure

Fifty-two signs without endpoint marking were clearly identified as atelic by the two semantic tests (see Table 6). Three additional signs were classified into the atelic category: One sign without endpoint marking was clearly identified as atelic by the ‘for an hour’ test and as relatively clear by the conjunction test (see Table 7). One sign was clearly identified as atelic by the conjunction test but showed a mixed pattern regarding the ‘for an hour’ test (see Table 8). For another sign without endpoint marking relatively clear results were revealed by both tests (see Table 9).

Table 6. Atelics: Clear on both tests (N = 52)

Table 7. Atelics: ‘For an hour’ test clear and conjunction test relatively clear (N = 1)

Table 8. Atelics: Conjunction test clear and ‘for an hour’ test mixed pattern (N = 1)

Table 9. Atelics: Both tests relatively clear (N = 1)

2.2.4. Signs potentially contradicting the EVH

Ten signs appeared to contradict the expectations based on the EVH. Among these, eight signs exhibited phonological endpoint marking, but semantically tested as having atelic event structure (see Table 10, Figure 4); the remaining two signs lacked endpoint marking yet were interpreted by respondents as having telic event structure (see Table 11, Figure 5).

Table 10. Atelic test results but telic form (N = 8)

Figure 4. Signs with endpoint marking and atelic event structure.

Table 11. Telic test results but atelic form (N = 2)

Figure 5. Signs lacking endpoint marking and telic event structure.

3. Discussion

The confirmation of the EVH was largely consistent for most of the verbs (N = 109), with the telicity test results aligning with the phonological verb form, indicating a systematic mapping: Telic verbs manifesting the endpoint marking, atelic verbs lacking such marking. However, 10 of the 119 signs presented complexities in this mapping. Upon closer examination of the semantic elicitation responses and phonology, half of these signs (N = 5) manifested argument structure alternations in ÖGS, similar to those found in English verbs (Levin, Reference Levin1993). Only five signs appeared to present exceptions to the EVH; however, nuanced analysis indicated that the phonological form of these signs still reflected components of event structure, although not the marking of the end-state.

The present study provides further information about telicity and the systematic mapping between event semantics and the phonological verb form (i.e., event visibility as proposed by the EVH) on a larger set of ÖGS signs, extending our knowledge about the ÖGS verb system and contributing to cross-linguistic findings on event structure and telicity. This investigation presents some preliminary findings regarding argument structure alternations and the representation of event onset, that is, linguistic phenomena that have previously been discussed only rarely with respect to sign languages. In contrast to the majority of studies on telicity in sign languages, this study determined telicity by semantic tests.

3.1. Verbs with atelic event structure and telic form

For two of the signs identified as atelic events by the semantic tests (with unambiguous results on the ‘for an hour’ test, and a relatively clear result on the conjunction test), despite their exhibiting endpoint marking, some signers noted that the movement component of the verb had to be modified in the context of durative reading (i.e., in combination with the ‘for an hour’ or ‘two days long’ phrases). The verb küssen (kiss) required repetition or a longer duration to convey the intended atelic reading. Similarly, the sign rufen (shout) required repetition to be interpreted as an atelic event. These examples illustrate verb frame alternations (cf. Levin, Reference Levin1993, for English examples), expressed in the phonological form of the verb sign. The verbs küssen and rufen can alternate between a punctual event and a durative event reading (e.g., give one kiss vs. kiss for some time; shout once vs. shout for some time), whereby the durative interpretation may also be construed as a single, extended event.

For another three signs exhibiting phonological features that can be interpreted as endpoint marking and showing an atelic event structure, similar possibilities of verb frame alternations were observed. The signs ertauben (get deaf; clear results on the conjunction test and a relatively clear result on the ‘for an hour’ test), verschwinden (disappear; clear results on both tests) and the sign weg/ab (leave; relatively clear results on both tests) can alternate between an inchoative (change of state, with the emphasis on the onset of the event) and a state interpretation (e.g., get deaf vs. be deaf; disappear vs. be absent; leave/go away vs. be away). Within these signs, the phonological boundary marking may have two semantic interpretations: As marking of the end-state in a telic (inchoative) event, or the initiation of the (resultant) state in an atelic (state) eventFootnote 11.

Similarly, the sign besuchen (visit) has atelic semantics (clear on both tests), but exhibits the phonology of a telic verb sign. The sign is an agreeing verb that inflects in signing space with reference loci associated with its subject and object arguments. Thereby, the sign moves from the reference locus associated with the subject argument to the locus associated with the object argument, leading to a (non-repeated) path movement with a stop at the location associated with the object argument. Schalber (Reference Schalber2006) describes such examples as belonging to a subclass of agreeing verbs in ÖGS, which are semantically atelic, but have an internal (object) argument that is indicated by the same motion type as the endpoint in telic verbs: Rapid movement to a stop at the end of the sign. Schalber observed this phonological form for agreeing verbs with atelic semantics, and suggested that these verbs denote the real or metaphorical transfer event, which has heterogeneous structure. One other example from Schalber (Reference Schalber2006) is the verb vertrauen (trust), which shows agreement marking by a change in hand orientation with a rapid stop. Semantically, however, the sign denotes homogeneous internal structure with no change of state or endpoint. Schalber suggested that the structure of this sign is based on its metaphorical use as a verb of transfer, whereby an abstract entity is transferred (‘I give you my trust’). The phonological form of the verb besuchen (visit) tested in the present study might represent the physical transfer of a person to a specific location. Endpoint marking expressed by a change of location might not only mark the object argument, but also the initiation of the process of visiting (someone is staying at the place where she/he has gone). Similarly, the signs leben (live) and wünschen (wish), which have atelic semantics (evidenced by unambiguous results for semantic tests), yet possess phonological features characteristic of boundary marking, appear to use phonological features to emphasize the initiation of the state (live) or the process (wish).

In general, the seeming misalignment between the semantics and phonology of the eight ÖGS verbs described above indicates, in close elicitation, the potential for the phonological features previously investigated as end-state markings to also denote transfer and mark sign-internal argumentsFootnote 12. The observations of verb frame alternation possibilities in ÖGS also illustrate the rich potential taxonomy of the event structure conceptualization that goes beyond the telic–atelic dichotomy. For instance, Kuhn (Reference Kuhn2017) suggested that verbs in ASL are decomposed into a logical form with a scale that not only includes the two endpoints telic and atelic, but a richer scale including intermediate degrees (Hay et al., Reference Hay, Kennedy, Levin, Matthews and Strolovitch1999; Kennedy & Levin, Reference Kennedy, Levin, McNally and Kennedy2008). Kuhn further notes that ASL verbs show a mapping that represents change along this scale and that endpoint-marking of telics is the iconic representation of the end of a scale. For instance, the phonological form of the ASL sign DIE can be modified by inserting stops in sign movement to express that a person died gradually, with intermediate states of deteriorating health until death (‘bit-by-bit’ inflection) (Kuhn, Reference Kuhn2017). Further, Wilbur et al. (Reference Wilbur, Malaia, Shay, Aloni, Kimmelman, Roelofsen, Sassoon, Schulz and Westera2012) analyzed the ASL excessive construction, TOO ADJ TO VERB, for example, ‘too far to walk’ and reported that when adjectives that normally lack an end of scale are put into this construction, an overt boundary marking (parallel to end-state deceleration) is added because the construction itself means that the activity denoted by the verb is beyond the reasonable end of scale for the adjective.

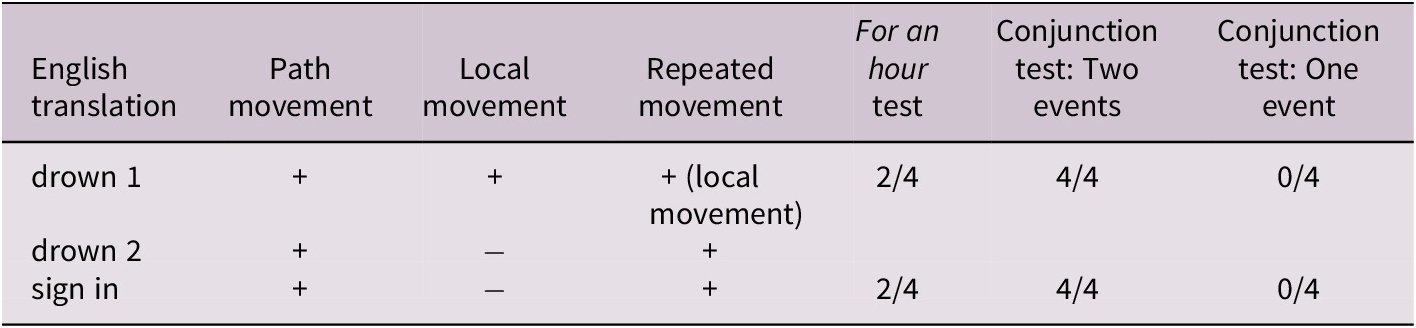

3.2. Verbs with telic event structure and atelic form

Two of the signs investigated in the present study – ertrinken (drown) and anmelden (sign in) – manifested telic semantics (unambiguous on the conjunction test, with a mixed pattern on the for an hour test), but lacked phonological features typical of telic signs, incorporating repeated movement instead. Interestingly, for the sign ertrinken (drown), two ÖGS sign forms were produced. One sign began with an upward path movement with repeated finger movement, indicating that the head is moving under water. The second sign involved repeated movement of the hands toward the mouth, indicating that water is swallowed repeatedly. Thus, the phonological form of these signs appears to focus on the manner of the event, as opposed to the event structure denoted by the verb.

The sign anmelden (sign in) is connected, both semantically and phonologically, with the ÖGS sign melden (report), which uses the same handshape and movement (small repeated path movements), but differs in that it is produced by one hand and can be inflected in signing space to indicate verbal agreement by change of hand orientation.Footnote 13 The sign anmelden (sign in) is produced with two hands, such that the non-dominant hand serves as ground – the place of articulation – while the small repeated path movements of the dominant hand lead to repeated contact between both hands (the fingertips of the dominant hand contact the back of the non-dominant hand). Thus, the form of the sign anmelden (sign in) might be related to the event of telling or informing someone.

Thus, while these examples do not show a clear mapping as expected by the EVH in terms of telicity and are not systematic for event endpoint or change of state, other parameters of verb semantics, such as manner or onset component of event structure, may be systematically reflected in the phonological form of the verb sign.

3.3. Greater variability in test responses observed for telic signs

In general, participants provided more unambiguous judgments for signs belonging to the atelic verb category compared to verbs classified as telic. Additionally, the results of both semantic tests were clear for the majority of atelic verbs. Only a few signs with atelic event structure yielded only ‘relatively’ clear test results (three out of four responses) on one or both tests, and there was only one sign (reisen, travel) with a mixed pattern (two out of four responses) on the ‘for an hour’ test. For two signers, the combination of the sign reisen (travel) with the phrase for an hour seemed to be too short (the combination with a phrase expressing a longer period of time, such as, e.g., for a week was acceptable).

For telic verbs, on the other hand, the decision of whether a specific phrase could be combined with a verb sign was often not as straightforward, and signers sometimes provided more interpretation possibilities for the meaning of the combinations. For a number of telics, clear results on both tests were observed. However, in comparison to the atelic category, the test results were more differentiated in the telic group. For 12 signs, while the responses to the conjunction test were clear, there was variability among judgments on the ‘for an hour’ test. For two signs, the ‘for an hour’ test yielded unambiguous interpretations, but there was variability among judgments regarding the conjunction test. For 10 signs, the informants varied in their judgments on both tests.

For three signs, the ‘for an hour’ test points toward an atelic event structure (relatively clear test result; 3/4), but the conjunction test showed either a clearly telic, a relatively clearly telic or a mixed pattern. Two of the signs, ersticken (suffocate) and aufholen (catch up), were described by the informants as semantically telic, but with additional durative reading of the pre-end-state component of the event structure over short time scales (i.e., in combination with ‘for an hour’), but not longer time periods (such as ‘for two days’). The sign erblassen (turn pale) elicited a mixed pattern of responses on the conjunction test; in-depth interview revealed that this sign allows for verb frame alternation in that it can be used to express a change of state (turn pale) or a state (be pale), which both might last 2 days.

This data suggest that signs describing telic events might have semantic restrictions, whereby some telic verbs might allow combinability with the adverbial phrase indicating short duration (‘for an hour’), but not a longer one (‘two days’), and some might be combined with either.

The present findings are in line with previous work suggesting that telic verbs can have a more complex event structure than atelic verbs, both in encompassing different types of inchoative structures (onset and offset of events), and focusing on grammatically relevant semantic features of included states or activities – such as durativity, manner or internal object or location-encoded goal (e.g., Malaia et al., Reference Malaia, Ranaweera, Wilbur and Talavage2012; Wilbur, Reference Wilbur2003, Reference Wilbur and Quer2008). Furthermore, previous cross-linguistic research on the neuropsychological bases of event type processing suggested that telics, which have a conceptual boundary for event segmentation, trigger the retrieval of an event template from long-term memory along with thematic roles inherent in it. Psycholinguistic studies showed that the processing of telics involves a segmentation operation that might require more effort at the point of being carried out but might facilitate thematic role re-assignment during the resolution of garden path sentences in English (Malaia et al., Reference Malaia, Wilbur and Weber-Fox2009, Reference Malaia, Wilbur and Weber-Fox2012, Reference Malaia, Wilbur, Weber-Fox, Arsenijević, Gehrke and Marín2013) or facilitate participants’ performance in a following offline classification task (Ji & Papafragou, Reference Ji and Papafragou2020; Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Wilbur, Roehm and Malaia2023a).

The greater variability in test responses for telic verbs in our study can be attributed to the inherently more complex event structure of these verbs. Unlike atelic predicates, which denote homogeneous activities without an inherent endpoint, telic verbs may encode one or more transition(s) between distinct event phases, sometimes with a culmination point (Dowty, Reference Dowty1979; O’Bryan et al., Reference O’Bryan, Folli, Harley and Bever2013; Ramchand, Reference Ramchand2008). This structural complexity results in a wider range of possible mappings between semantic components (phases) and phonological realization. In ÖGS, as in other sign languages, telic predicates tend to be marked by sharp deceleration, abrupt stops or changes in hand orientation, all of which serve to systematically signal the endpoint of the event (Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Strutzenberger, Schwameder, Wilbur, Malaia and Roehm2021; Wilbur, Reference Wilbur and Quer2008). However, as motion capture data from ÖGS suggest (Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Fessl, Wilbur, Malaia, Wiesinger, Schwameder and Roehm2023b), variability arises from multiple factors, including argument structure alternations and phonotactic constraints specific to individual verb signs. Some verbs that are semantically telic fail to exhibit an overt phonological endpoint (marking an initiation point instead), while others marked with clear deceleration patterns may not be judged as telic in semantic tests due to specifics of context – either with regard to temporal modification or argument structure. This suggests that the mapping between verb semantics and phonological features is subject to language-internal phonological constraints, as well as typological variability, as has been reported in ASL and HZJ (Malaia & Wilbur, Reference Malaia and Wilbur2011; Milković, Reference Milković2011). Additionally, cross-linguistic evidence – including spoken language data – indicates that telic predicates are more susceptible to event structure coercion, where individual and dialectal preferences, pragmatic context and syntactic framing can all influence interpretation (Borer, Reference Borer2005; O’Bryan et al., Reference O’Bryan, Folli, Harley and Bever2013; Ramchand, Reference Ramchand2008). Future research using high-resolution motion tracking and cross-linguistic comparisons in unrelated sign languages could provide insight into the factors contributing to this variability.

3.4. Event structure alternations in telic verb signs

While many of the tested verbs clearly perform as telic on the conjunction test, for some of the telic signs, alternative interpretation possibilities seem to be available. These are the cases where interview data revealed variability in judgments among participants, indicating that some verbs can be used in combination with either of the temporal adverbials on the test, yielding different meanings. Verb class alternation (the possibility of the same verb stem being used to have two distinctly different event structures) has been documented for spoken languages (Levin, Reference Levin1993), but has not been discussed extensively for sign languages. Previous work on spoken verb class alternations has suggested approaches to clarifying verb frames and alternations in event structure based on the meaning of the verb in context – for example, in combination with arguments (semantic Agent and Patient), temporal adverbials, as well as markers of tense and aspect (cf. Levin, Reference Levin2015; Partee, Reference Partee1975; see also the work on aspectual coercion: e.g., De Swart, Reference De Swart1998, Reference De Swart, Butt and King2000; Dölling, Reference Dölling and Robering2014; Moens & Steedman, Reference Moens and Steedman1988; Paczynski et al., Reference Paczynski, Jackendoff and Kuperberg2014; Pustejovsky & Bouillon, Reference Pustejovsky and Bouillon1995). In the following, we describe the observations of verb frame alternations in ÖGS in more detail.

Elicitation data from ÖGS indicated that the combination with the phrase ‘for an hour’ as well as with the phrase ‘two days long’ may sometimes lead to a reading (i.e., interpreted meaning) in which the focus is not on the change of state, but rather the entirety of the event bounded by, in this case, the temporal adverbial (e.g., lock something for an hour, fall asleep for an hour, book something for an hour, lose something for an hour, forget something for two days or be arrested for two days). The interviewees also suggest that the phonological form of the verb may change to clearly express the difference in the event structure for the verbs that allow frame alternations. For instance, the sign erblassen (turn pale) combined with the phrase ‘for an hour’, expressing durative change of state (i.e., ‘to continue getting pale for an hour’), is signed by a slower movement as compared to the same verb sign in combination with the phrase ‘for an hour’, with the meaning ‘to be pale for an hour’.

For some telic verbs, the combination with the durative adverbial phrase for an hour is possible only in specific cases, constrained by the aspects of semantics that do not directly have anything to do with event structure. For example, the verb öffnen (open) can only combine with ‘for an hour’-type durative adverbial phrase if something is difficult to open; the verb zusperren (lock up), similarly, only allows such combinability if the action is difficult to accomplish; the verb bestellen (order) allows for durative adverbial combination only if someone is ordering a long list of things. So, while these verbs do allow for combinability with either durative or punctual adverbials, the durative reading of the activity or state prior to the change provided by the durative adverbial is restricted as to possible context (which might be interpreted as manner). In at least one case among the verbs we studied, the type of patient (when the verb was used in a sentence) was important for sentence-level semantics: The verb ändern (change) could be combined with either the for an hour and the two days long phrases, but only when the process of change scoped over a grand scale: ‘the weather is changing’ or ‘to make changes in the house’.

3.5. Grammatically relevant semantics in phonology beyond telicity

While the main focus of our study was telicity marking in ÖGS, interviews revealed that the phonological form of the verb can sometimes reflect components of event semantics and structure beyond telicity. As described above, the endpoint marking of a change of state verb (e.g., erblassen, turn pale) could also be interpreted as event onset for an atelic (state) event, when combined with the durative adverbial phrase ‘for an hour’ (e.g., ‘be pale for an hour’). The atelic verb entspannen (relax), a two-handed sign produced with a contact between the hands at the beginning of the sign, also appeared to encode the initiation of the event in its phonological form. Also, some telic signs in the data set involved contact of the dominant hand with the non-dominant hand or with another body part at the beginning (e.g., geben, give) or in the middle of the sign (e.g., ausrutschen, slip), rather than at the end of the sign. However, these telic signs did include additional (velocity-based) phonological endpoint marking (in contrast, the verb entspannen does not show any form of boundary marking).

In addition, the data suggest that the arguments, that is, the agent and patient/undergoer of the event, may be spatially referenced in the phonological form of signed verbs: In ÖGS, the patient is marked in certain transitive agreeing verbs by directing the path movement toward a location associated with the object argument in the default (non-inflected) form (e.g., the agreeing verb besuchen, visit).

Non-manual markings produced simultaneously with the manual part of the sign may also indicate the agent/patient arguments. A sideways body shift may indicate the agent role (in ÖGS, a subject), with the body shifted toward the location associated with the subject argument. Eye gaze directed toward the location associated with the object argument might reflect the patient/undergoer. For instance, in the recorded video of our elicitation, the verb anstecken (to infect) is accompanied by a left body shift, and the path movement is directed to the right toward the location associated with the object argument. The signs auswählen (to choose) and abschalten (to shut down) in the data also show eye gaze directed toward the location associated with the object argument.

The verbs with non-manual marking of agent or patient arguments are typically agreeing verbs that also inflect spatially. Our examples suggest that for certain transitive verbs, the agent and patient arguments can be marked by co-occurring non-manuals, independent of the form of agreement marking: The verb anstecken (to infect) shows path movement from subject to object location and palm orientation toward the object; the verb auswählen (to choose) shows path movement from object to subject location and palm orientation toward the object; the verb abschalten (to shut down) can indicate agreement by being produced at a location associated with the object argument (this verb sign lacks path movement between the two locations associated with the agent/patient arguments). These non-manual argument-structure markings have been observed previously at the sentence level for ÖGS in structures with agreeing verbs or agreement markers (Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Malaia, Wilbur and Roehm2018, Reference Krebs, Wilbur, Alday and Roehm2019, Reference Krebs, Wilbur and Roehm2020).

3.6. Tests for telicity applicable in ÖGS

Not all of the tests we applied to determine telicity in ÖGS worked reliably in this language. The conjunction test, as well as the temporal adverbial modification test, provided the most consistent results. With some verbs, the combination with the ‘for an hour’ phrase was judged unacceptable, but the combination with an adverbial phrase expressing a longer time period was acceptable. For instance, for one signer, the verb ertauben (to become deaf) was acceptable combined with ‘for a year’, or for two of our informants, reisen (to travel) was acceptable with ‘for a month’ or ‘for a week’, but not with ‘for an hour’.

The ‘complete something in an hour’ test did not perform in ÖGS in the same way that it has been used in, for example, ASL. In our data, not only telic verbs but also many atelic verbs could be combined with this phrase. In the interview sessions, we used an additional phrase that Malaia and Wilbur (Reference Malaia and Wilbur2011) employed for testing telicity in ASL, translating ‘in an hour’ to ‘it-took-an-hour’. We used a similar version in ÖGS which can be translated as ‘takes an hour to finish’. However, this phrase could also be combined with both telic and atelic verbs. In line with this finding, the ‘stop/finish’ combinability test did not provide clear results with respect to the telic–atelic distinction. Atelic signs were judged as combinable with the sign fertig (finish) expressing ‘completive’ meaning. Additionally, telic signs could combine with the sign stoppen (stop) – which, in English, is only possible for atelic ones; thus, while the semantics of ÖGS stoppen is broadly similar to ‘to stop’, it does not have the same selectional restrictions as the English term. Similarly, Rathmann (Reference Rathmann2005) noted that in ASL, the ‘in an hour’ test as well as the ‘stop/finish’ combinability test did not provide the expected results.

The ‘almost’ modification test was also unsuitable for testing telicity in ÖGS. For many of the atelics (like many telic verbs), both interpretations were possible: The ‘wasn’t started/didn’t start’ interpretation and the ‘started but was stopped before it finished’ interpretation. Although some of the tests employed in the study were not useful for distinguishing telic and atelic verbs in ÖGS, they, in some cases, helped elicit a more nuanced understanding of syntactic and semantic constraints and nuances of meaning related to event structure in ÖGS. Thus, the ways in which these tests can tap into aspects of event structure and fine-grained semantics of the verbs in a way that is circumscribed by the parameters of the specific language under investigation remain to be researched further.

The present study further confirms that the semantic tests used for examining telicity are restricted in their cross-linguistic application (Borik, Reference Borik2006) and shows that this is true even for sign languages for which the event structure is systematically reflected in the phonological form of verbs. As pointed out before, in sign languages the systematic form-meaning mapping (i.e., event visibility) is determined by the linguistic structure of each sign language, showing language-specific differences in the phonological inventory and grammatical structure. Therefore, it is not surprising that cross-linguistic differences in the application of linguistic tests can also be observed within sign languages.

3.7. Directions for further research

The participant group in this study focused on a group of signers whose age ranges between 51 and 59 years and who acquired ÖGS between 4 and 7 years of age. Future investigations would have to investigate how individual differences, or aspects such as signers’ age or age of sign language acquisition might impact event structure representation in signers. Further investigations focused on other components of event structure, such as dynamicity or agentivity, or the various forms of verb modifications expressing different types of grammatical aspect (Klima & Bellugi, Reference Klima and Bellugi1979; Wilbur, Reference Wilbur and Quer2008), are needed to construct a more comprehensive picture of how event structure may be manifested cross-linguistically and cross-modally, in language and cognition.

The EVH’s main theoretical contribution may be methodological, as it demonstrates that systematic empirical investigation can reveal linguistic structure in phenomena initially attributed to iconicity. This transition to objective, quantifiable analysis is similar to the one that happened in spoken language phonology, where observations about ‘natural’ sound patterns gave way to phonological analyses based on well-operationalized measures (F0, power-spectral entropy, etc.). By providing explicit predictions about form-meaning mappings, the EVH provides the bases for forming falsifiable hypotheses that are sign-language-specific.

4. Conclusion

This study extends research in sign languages, focusing on event visibility in verb signs. Most of the ÖGS verbs investigated in the present study mapped event structure systematically to phonology. A small set of signs exhibited a combination of semantic behaviors (e.g., frame alternations, focus on event onset) that resulted in phonological representations not predicted by the telic–atelic dichotomy, and these cases require further analysis. The greater variability in test responses elicited from informants regarding telic signs suggests that the inventory of inchoative verb signs in ÖGS (those encompassing a change of state within their event structure) might reflect a more complex taxonomy of event structures as compared to atelic signs, or as previously documented for other sign languages.

This study both provides new insights into the verb system of ÖGS and contributes to models of cross-linguistic variability in verbal event structure and event visibility.

Data availability statement

The dataset generated and analyzed for this study is available at https://osf.io/2xkyp/?view_only=71ca33fa77b1416b96f3eff04e116518

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all our ÖGS experts for taking part in this study. Special thanks to Waltraud Unterasinger for signing the ÖGS signs. This research was funded in whole or in part by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) [10.55776/ESP252]. For open access purposes, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright license to any author accepted manuscript version arising from this submission.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.