1 Introduction

The index of a pair of projections introduced in [Reference Kato36, Reference Brown, Douglas and Fillmore21, Reference Avron, Seiler and Simon6] and explored further in [Reference Avron, Seiler and Simon7] is an integer-valued index that can be associated with two projections

![]() $P,Q$

on a Hilbert space whenever their difference is compact:

$P,Q$

on a Hilbert space whenever their difference is compact:

It is ‘topological’ in the sense that it is invariant under compact and norm-continuous deformations. In the case where one of the projections is a unitary conjugate of the other,

![]() $Q = U^\ast P U$

, the index reduces to a Fredholm index of

$Q = U^\ast P U$

, the index reduces to a Fredholm index of

![]() $PUP+P^\perp $

.

$PUP+P^\perp $

.

Since its introduction, this notion has been intimately connected to the quantum Hall effect. It is indeed one of the possible expressions for the Hall conductance, when the currents are driven by the adiabatic increase of a magnetic flux through the two-dimensional electron gas. The physical meaning of P is that of a Fermi projection whenever the Fermi energy lies in a spectral gap or a mobility gap [Reference Aizenman and Michele Graf1]. In particular, this picture is valid in a noninteracting setting where the many-body ground state reduces to a one-body projection, see [Reference Michele Graf30] for an overview and further references. This concept was eventually generalized to yield the index of all entries of the Kitaev periodic table of topological insulators [Reference Katsura and Koma37, Reference Katsura and Koma38].

There have been various attempts of generalizing the index of a pair of projections to an interacting setting where the state is not simply given by a projection in Hilbert space, most notably [Reference Bachmann, Bols, De Roeck and Fraas9] in an arbitrarily large finite volume followed by [Reference Kapustin and Sopenko33] in the infinite volume setting, where quantization can be proved under the assumption of invertibility of the initial state. In both cases, the attention is on the Hall effect.

In this work, we introduce a generalization of the above indices which is defined in a completely abstract setting. It is associated with two pure states

![]() $(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

of a C*-algebra

$(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

of a C*-algebra

![]() ${{\mathcal A}}$

that are related by an inner automorphism, in the presence of a

${{\mathcal A}}$

that are related by an inner automorphism, in the presence of a

![]() $U(1)$

symmetry. Specifically, when

$U(1)$

symmetry. Specifically, when

![]() $\omega _2 = \omega _1\circ \mathrm {Ad}_u$

, where

$\omega _2 = \omega _1\circ \mathrm {Ad}_u$

, where

![]() $u\in {{\mathcal A}}$

is unitary the index is given by

$u\in {{\mathcal A}}$

is unitary the index is given by

where

![]() $\delta ^\rho $

is the generator of the

$\delta ^\rho $

is the generator of the

![]() $U(1)$

-symmetry. We prove, among other things, that the index is integer valued, operator-norm-continuous, and invariant under deformations by symmetric automorphisms. We also show that if the algebra is chosen to be the CAR algebra describing Fermions and if the two states are quasi-free, then our index reduces to the index of a pair of projections. Therefore, this new index of a pair of pure states generalizes [Reference Avron, Seiler and Simon7], as well as the noncommutative geometric approach of [Reference Bellissard, van Elst and Schulz-Baldes17].

$U(1)$

-symmetry. We prove, among other things, that the index is integer valued, operator-norm-continuous, and invariant under deformations by symmetric automorphisms. We also show that if the algebra is chosen to be the CAR algebra describing Fermions and if the two states are quasi-free, then our index reduces to the index of a pair of projections. Therefore, this new index of a pair of pure states generalizes [Reference Avron, Seiler and Simon7], as well as the noncommutative geometric approach of [Reference Bellissard, van Elst and Schulz-Baldes17].

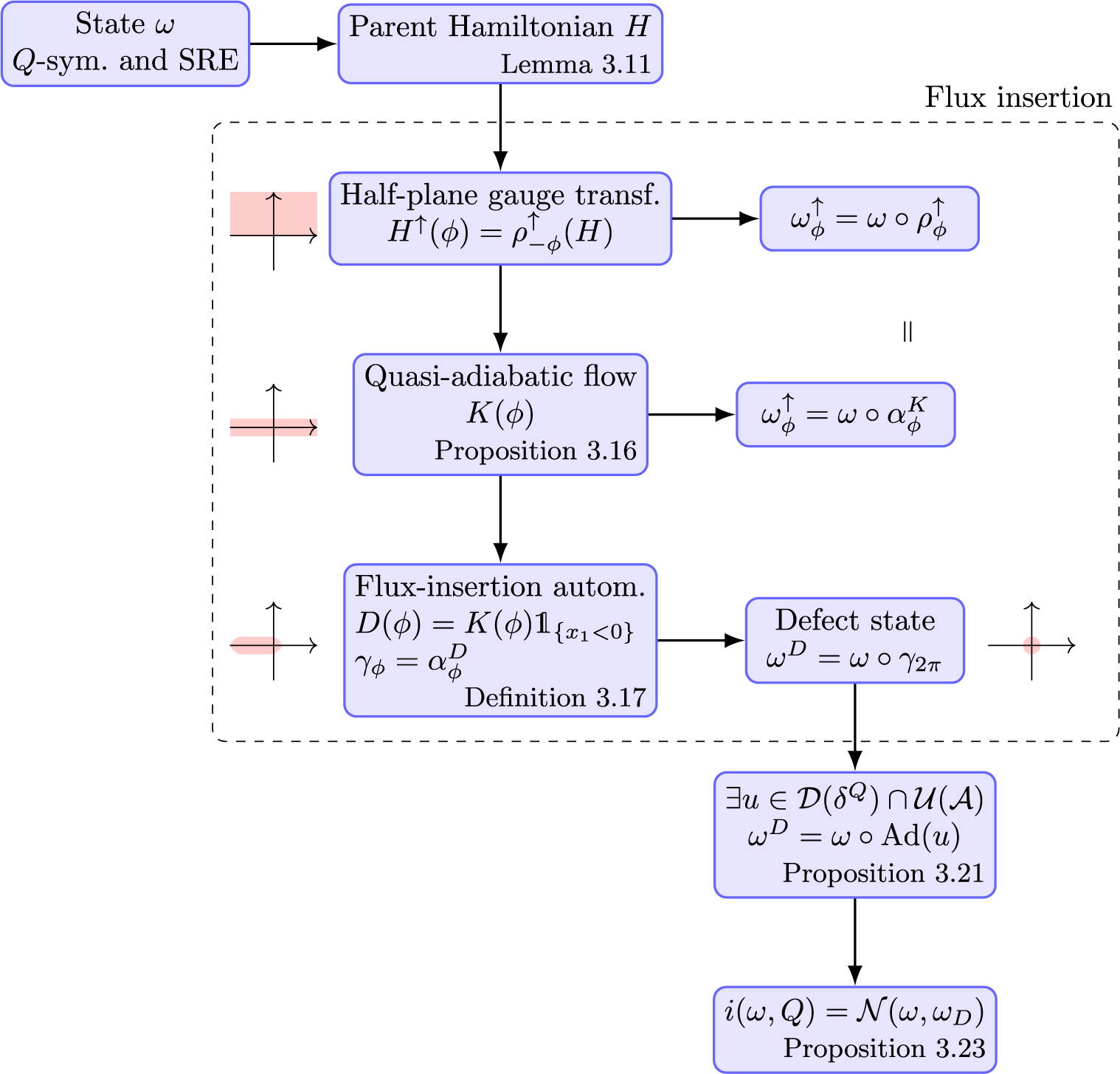

We then turn to the quantum Hall effect. Echoing [Reference Kapustin and Sopenko33], we prove that the piercing of a magnetic flux from

![]() $0$

to

$0$

to

![]() $2\pi $

starting from an invertible state corresponds to a situation where the many-body index is well-defined. The technical part here uses adiabatic flux insertion à la Laughlin [Reference Laughlin40] extended to the many-body setting in [Reference Bachmann, Bols and Rahnama10]. Unlike there, we focus on charge conservation rather than time-reversal symmetry. In this context, the many-body index equals the charge deficiency of the final state with respect to the initial state, and so to the Hall conductance by the Laughlin argument. This places the Hall index into a very general C*-algebraic framework which is valid for both interacting and noninteracting fermionic systems, generalizing previous expressions [Reference Bachmann, Bols, De Roeck and Fraas9, Reference Kapustin and Sopenko33] and placing them in a functional analytic framework which complements other approaches using algebraic topology [Reference Kapustin and Sopenko34, Reference Artymowicz, Kapustin and Sopenko3].

$2\pi $

starting from an invertible state corresponds to a situation where the many-body index is well-defined. The technical part here uses adiabatic flux insertion à la Laughlin [Reference Laughlin40] extended to the many-body setting in [Reference Bachmann, Bols and Rahnama10]. Unlike there, we focus on charge conservation rather than time-reversal symmetry. In this context, the many-body index equals the charge deficiency of the final state with respect to the initial state, and so to the Hall conductance by the Laughlin argument. This places the Hall index into a very general C*-algebraic framework which is valid for both interacting and noninteracting fermionic systems, generalizing previous expressions [Reference Bachmann, Bols, De Roeck and Fraas9, Reference Kapustin and Sopenko33] and placing them in a functional analytic framework which complements other approaches using algebraic topology [Reference Kapustin and Sopenko34, Reference Artymowicz, Kapustin and Sopenko3].

We point out immediately that the invertibility assumption appears in two roles that are very distinct from each other. It first plays a role as a tool that allows us to ensure that the state is the gapped ground state of a so-called parent Hamiltonian. Secondly, it is crucial in concluding that the defect state obtained after flux insertion is locally comparable to the initial state, namely that the two differ only in the vicinity of the puncture and not at infinity. While the first role could be bypassed in a physical setting where the state is given as a gapped ground state, the second one appears fundamental. Indeed, it is that very assumption that ensures that the state has integer quantum Hall conductance as opposed to fractional conductance. In the latter case, the initial state is expected to have nontrivial superselection sectors corresponding to anyonic excitations (see [Reference Ogata43] for one possible meaning of these terms and [Reference Fröhlich, Studer and Thiran25] for an overview of anyons in the fractional quantum Hall effect) and these cannot be realized upon an invertible state [Reference Kitaev39, Reference Bachmann, Getz, Naaijkens and Wray15].

Let us briefly discuss other approaches to (integer) quantization in the interacting quantum Hall effect. In the single particle picture, charge deficiency, charge transport and linear response coincide [Reference Laughlin40, Reference Avron, Seiler and Simon6, Reference Michele Graf30]. This equivalence continues to hold in the interacting picture [Reference Bachmann, Bols, De Roeck and Fraas9, Reference Kapustin and Sopenko33], where quantization of the Hall conductance was proved in [Reference Hastings and Michalakis31, Reference Bachmann, Bols, De Roeck and Fraas8], see also [Reference Bachmann, De Roeck and Fraas12, Reference Monaco and Teufel42] for the validity of linear response. While the above assume the presence of a gap, this assumption is proved to hold in a perturbative setting in [Reference Giuliani, Mastropietro and Porta28], while it is not needed if one considers nonequilibrium almost steady states [Reference Wesle, Marcelli, Miyao, Monaco and Teufel49, Reference Teufel and Wesle46].

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we describe the general algebraic setting, introduce the notion of two pure states being

![]() $\rho $

-locally comparable, (see Definition 2.3) and define the index

$\rho $

-locally comparable, (see Definition 2.3) and define the index

![]() ${\mathcal N}_\rho (\omega _1,\omega _2)$

. If

${\mathcal N}_\rho (\omega _1,\omega _2)$

. If

![]() $\rho _t$

is a

$\rho _t$

is a

![]() $U(1)$

-symmetry, then

$U(1)$

-symmetry, then

In Section 2.2, we consider the Fermionic algebra

![]() ${\mathcal A}=\mathrm {CAR}(\cal H)$

on a one-particle Hilbert space

${\mathcal A}=\mathrm {CAR}(\cal H)$

on a one-particle Hilbert space

![]() $\mathcal {H}$

. For

$\mathcal {H}$

. For

![]() $P,Q$

two orthogonal projections on

$P,Q$

two orthogonal projections on

![]() $\mathcal H$

and

$\mathcal H$

and

![]() $\omega _P, \omega _Q$

their corresponding quasi-free states on

$\omega _P, \omega _Q$

their corresponding quasi-free states on

![]() ${\mathcal A}$

, we show that if

${\mathcal A}$

, we show that if

![]() $P-Q$

is trace class then

$P-Q$

is trace class then

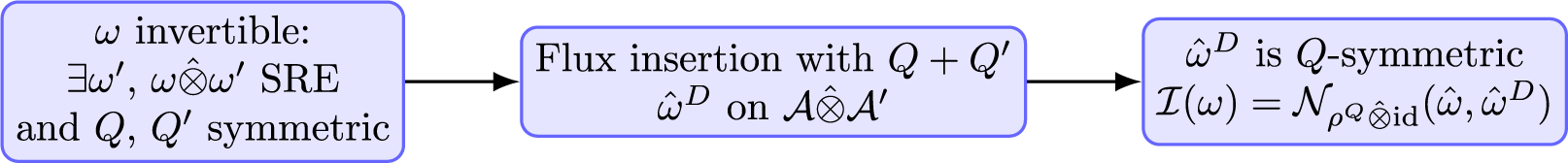

the index of a pair of projection. Section 3 focusses on the quantum Hall effect in an interacting setting where the two states are an initial invertible state and a defect state obtained from the initial one by inserting a unit of flux at the origin. Then the charge deficiency, and therefore the Hall conductance, is given by

where

![]() $\hat \cdot $

corresponds to a stacking operation associated to invertible states. The fact that we pick

$\hat \cdot $

corresponds to a stacking operation associated to invertible states. The fact that we pick

![]() $\rho \otimes \mathrm {id}$

rather than the stacked

$\rho \otimes \mathrm {id}$

rather than the stacked

![]() $\hat {\rho }$

means that we measure only the charge transported in the original system, rather than in the full, stacked system. We then show in Section 4 that this index covers gapped ground states of interacting Hamiltonian as well, and that in the quasi-free case it coincides with a single-particle spectral flow.

$\hat {\rho }$

means that we measure only the charge transported in the original system, rather than in the full, stacked system. We then show in Section 4 that this index covers gapped ground states of interacting Hamiltonian as well, and that in the quasi-free case it coincides with a single-particle spectral flow.

2 Abstract index theory

2.1 The index of a pair of pure states

Let

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

be a unital C*-algebra. In later sections we shall apply the theory to

$\mathcal {A}$

be a unital C*-algebra. In later sections we shall apply the theory to

![]() $\mathcal {A}=\operatorname {CAR}(\mathcal {H})$

for some separable Hilbert space

$\mathcal {A}=\operatorname {CAR}(\mathcal {H})$

for some separable Hilbert space

![]() $\mathcal {H}$

but in fact throughout this section no assumptions on

$\mathcal {H}$

but in fact throughout this section no assumptions on

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

will be made. We denote by

$\mathcal {A}$

will be made. We denote by

![]() $\mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

the set of unitary elements of

$\mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

the set of unitary elements of

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

. A state

$\mathcal {A}$

. A state

![]() $\omega : {\mathcal A} \to \mathbb C$

is a positive (i.e.,

$\omega : {\mathcal A} \to \mathbb C$

is a positive (i.e.,

![]() $\omega (a^{*} a)\geq 0$

for all

$\omega (a^{*} a)\geq 0$

for all

![]() $a\in \mathcal {A}$

) linear functional on

$a\in \mathcal {A}$

) linear functional on

![]() ${\mathcal A}$

with

${\mathcal A}$

with ![]() ; the space of all states shall be denoted

; the space of all states shall be denoted

![]() $\mathcal S({\mathcal A})$

. The condition

$\mathcal S({\mathcal A})$

. The condition ![]() is equivalent to the normalization

is equivalent to the normalization

![]() $\|\omega \| =1$

, where the norm is given by

$\|\omega \| =1$

, where the norm is given by

In other words, all states are on the unit sphere of

![]() ${{\mathcal A}}^{*}$

and so

${{\mathcal A}}^{*}$

and so

![]() $\mathcal S({\mathcal A})$

is a weakly*-compact and convex subset of

$\mathcal S({\mathcal A})$

is a weakly*-compact and convex subset of

![]() ${\mathcal A}^{*}$

. The extreme points of

${\mathcal A}^{*}$

. The extreme points of

![]() $\mathcal S({\mathcal A})$

are called pure states and their collection is denoted by

$\mathcal S({\mathcal A})$

are called pure states and their collection is denoted by

![]() ${\mathcal P}({{\mathcal A}})$

.

${\mathcal P}({{\mathcal A}})$

.

Definition 2.1 (locally comparable pair of pure states).

Let

![]() $\omega _1,\omega _2\in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {A})$

be a pair of pure states. We say that the pair

$\omega _1,\omega _2\in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {A})$

be a pair of pure states. We say that the pair

![]() $(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

is locally comparable iff there exists some

$(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

is locally comparable iff there exists some

![]() $u\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

such that

$u\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

such that

Here and in the sequel,

![]() $\operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

denotes the automorphism

$\operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

denotes the automorphism

![]() $\operatorname {Ad}_{u}(a) = u^{*} a u$

. In other words,

$\operatorname {Ad}_{u}(a) = u^{*} a u$

. In other words,

![]() $\omega _1$

and

$\omega _1$

and

![]() $\omega _2$

are locally comparable iff they are inner-automorphism equivalent.

$\omega _2$

are locally comparable iff they are inner-automorphism equivalent.

Remark 2.2. The intuition we have in mind for two pure states to be locally comparable is that their difference is “compact” in a vague sense. Since

if

![]() $\mathcal {A}=\operatorname {CAR}(\mathcal {H})$

for some Hilbert space

$\mathcal {A}=\operatorname {CAR}(\mathcal {H})$

for some Hilbert space

![]() $\mathcal {H}$

, then

$\mathcal {H}$

, then

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

may be considered as the operator norm limit of finite-rank (but not necessarily quadratic) observables, and as such, since

$\mathcal {A}$

may be considered as the operator norm limit of finite-rank (but not necessarily quadratic) observables, and as such, since

![]() $u\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

, we should consider

$u\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

, we should consider ![]() and hence also

and hence also

![]() $\operatorname {Ad}_{u}-\mathrm {id}$

to be (the many-body analog of) compact. Then by the ideal property, the whole expression

$\operatorname {Ad}_{u}-\mathrm {id}$

to be (the many-body analog of) compact. Then by the ideal property, the whole expression

![]() $\omega _1\circ \left (\operatorname {Ad}_{u}-\mathrm {id}\right )$

is.

$\omega _1\circ \left (\operatorname {Ad}_{u}-\mathrm {id}\right )$

is.

Back to the case of a general C*-algebra

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

, when two pure states

$\mathcal {A}$

, when two pure states

![]() $\omega _1,\omega _2$

are locally comparable, we want to measure how different they are, with the expectation that if they are path-connected (in

$\omega _1,\omega _2$

are locally comparable, we want to measure how different they are, with the expectation that if they are path-connected (in

![]() $\mathcal {P}(\mathcal {A})$

) they should not be different at all. This is the case when

$\mathcal {P}(\mathcal {A})$

) they should not be different at all. This is the case when

![]() $u\in \mathcal {U}_0(\mathcal {A})$

, that is, when u may be continuously deformed to

$u\in \mathcal {U}_0(\mathcal {A})$

, that is, when u may be continuously deformed to ![]() , whence we get a continuous deformation of

, whence we get a continuous deformation of

![]() $\omega _2$

to

$\omega _2$

to

![]() $\omega _1$

. However, there are C*-algebras where

$\omega _1$

. However, there are C*-algebras where

![]() $\pi _0(\mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A}))\neq \{0\}$

(for example

$\pi _0(\mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A}))\neq \{0\}$

(for example

![]() $C({\mathbb S}^1)$

). It will turn out that we are not quite interested in such obstructions. Rather, in many interesting cases (such as UHF algebras),

$C({\mathbb S}^1)$

). It will turn out that we are not quite interested in such obstructions. Rather, in many interesting cases (such as UHF algebras),

![]() $\pi _0(\mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A}))=\{0\}$

. Then, to gauge a topological obstruction we impose a further symmetry constraint.

$\pi _0(\mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A}))=\{0\}$

. Then, to gauge a topological obstruction we impose a further symmetry constraint.

Let

![]() $\{\rho _t\}_{t\in \mathbb {R}}\subseteq \operatorname {Aut}(\mathcal {A})$

be a strongly continuous one-parameter group of *-automorphisms. Its generator

$\{\rho _t\}_{t\in \mathbb {R}}\subseteq \operatorname {Aut}(\mathcal {A})$

be a strongly continuous one-parameter group of *-automorphisms. Its generator

![]() $\delta ^\rho $

, given by

$\delta ^\rho $

, given by

is a *-derivation. In general

![]() $\rho _t$

is not expected to be inner and

$\rho _t$

is not expected to be inner and

![]() $\delta ^\rho $

is not expected to be bounded. As such, we must consider

$\delta ^\rho $

is not expected to be bounded. As such, we must consider

![]() $\delta ^\rho $

together with its domain

$\delta ^\rho $

together with its domain

With this, we refine the notion of locally comparable pure states as follows.

Definition 2.3 (

$\rho $

-locally comparable pair of pure states).

$\rho $

-locally comparable pair of pure states).

Let

![]() $\rho _t$

be as above and

$\rho _t$

be as above and

![]() $(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

be a pair of pure states. We say that this pair is

$(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

be a pair of pure states. We say that this pair is

![]() $\rho $

-locally comparable iff there exists some

$\rho $

-locally comparable iff there exists some

![]() $u\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})\cap \mathcal {D}(\delta ^\rho )$

such that

$u\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})\cap \mathcal {D}(\delta ^\rho )$

such that

We now have all the definitions to set up our index.

Definition 2.4 (The index of a locally comparable pair of

$\rho $

-invariant pure states).

$\rho $

-invariant pure states).

Let

![]() $\rho _t$

be as above and

$\rho _t$

be as above and

![]() $(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

be a pair of

$(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

be a pair of

![]() $\rho $

-locally comparable pure states. Assume moreover that both

$\rho $

-locally comparable pure states. Assume moreover that both

![]() $\omega _1$

and

$\omega _1$

and

![]() $\omega _2$

are

$\omega _2$

are

![]() $\rho $

-invariant, that is,

$\rho $

-invariant, that is,

Then the index of the pair

![]() $(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

is defined as

$(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

is defined as

where

![]() $u\in \mathcal {D}(\delta ^\rho )$

is any unitary which obeys

$u\in \mathcal {D}(\delta ^\rho )$

is any unitary which obeys

![]() $\omega _2=\omega _1\circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

.

$\omega _2=\omega _1\circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

.

We note that in general there is no reason for the unitary u above to be

![]() $\rho _t$

-invariant; see Remark 3.22(iii) for an explicit example. Indeed, if this happens, then

$\rho _t$

-invariant; see Remark 3.22(iii) for an explicit example. Indeed, if this happens, then

![]() $\delta ^\rho (u) = 0$

and so

$\delta ^\rho (u) = 0$

and so

![]() $\mathcal {N}_\rho (\omega _1,\omega _2)=0$

.

$\mathcal {N}_\rho (\omega _1,\omega _2)=0$

.

The condition that the pair

![]() $(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

must be compatible with

$(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

must be compatible with

![]() $\rho $

in the above sense, namely that they are

$\rho $

in the above sense, namely that they are

![]() $\rho $

-locally comparable and invariant, means they are generically not path connected, which is what the index measures.

$\rho $

-locally comparable and invariant, means they are generically not path connected, which is what the index measures.

Theorem 2.5 (Properties of the index).

The index defined above has the following properties:

-

(i)

$\mathcal {N}_\rho (\omega _1,\omega _2)$

does not depend on the choice of

$\mathcal {N}_\rho (\omega _1,\omega _2)$

does not depend on the choice of

$u\in \mathcal {D}(\delta ^\rho )\cap \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

such that

$u\in \mathcal {D}(\delta ^\rho )\cap \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

such that

$\omega _2=\omega _1\circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

.

$\omega _2=\omega _1\circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

. -

(ii) If

$\rho _{2\pi }=\mathrm {id}$

, then

$\rho _{2\pi }=\mathrm {id}$

, then

$\mathcal {N}_\rho (\omega _1,\omega _2)\in \mathbb {Z}$

.

$\mathcal {N}_\rho (\omega _1,\omega _2)\in \mathbb {Z}$

. -

(iii)

$\mathcal {N}_\rho (\omega _1,\omega _2)$

has the following continuity property: (4)

$\mathcal {N}_\rho (\omega _1,\omega _2)$

has the following continuity property: (4) $$ \begin{align} \left\Vert \omega_1-\omega_2 \right\Vert<2\Longrightarrow \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_2) = 0. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \left\Vert \omega_1-\omega_2 \right\Vert<2\Longrightarrow \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_2) = 0. \end{align} $$

-

(iv) For any automorphism

$\alpha $

of

$\alpha $

of

${{\mathcal A}}$

such that

${{\mathcal A}}$

such that

$\alpha \circ \delta ^\rho = \delta ^\rho \circ \alpha $

, (5)

$\alpha \circ \delta ^\rho = \delta ^\rho \circ \alpha $

, (5) $$ \begin{align} \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1\circ\alpha,\omega_2\circ\alpha) = \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_2). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1\circ\alpha,\omega_2\circ\alpha) = \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_2). \end{align} $$

-

(v)

$\mathcal {N}_\rho \left (\omega ,\omega \right ) = 0$

for any

$\mathcal {N}_\rho \left (\omega ,\omega \right ) = 0$

for any

$\rho $

-invariant pure state

$\rho $

-invariant pure state

$\omega \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {A})$

.

$\omega \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {A})$

. -

(vi) If

$\omega _1,\omega _2,\omega _3$

are three pairwise

$\omega _1,\omega _2,\omega _3$

are three pairwise

$\rho $

-locally comparable pure states, all of which are

$\rho $

-locally comparable pure states, all of which are

$\rho $

-invariant, then (6)

$\rho $

-invariant, then (6) $$ \begin{align} \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_2)+\mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_2,\omega_3) = \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_3). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_2)+\mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_2,\omega_3) = \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_3). \end{align} $$

-

(vii) The index is anti-symmetric

(7) $$ \begin{align} \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_2) = -\mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_2,\omega_1). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_2) = -\mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_2,\omega_1). \end{align} $$

-

(viii) We have the following additivity with respect to tensor products. Let

$\widetilde {\mathcal {A}}$

be another C*-algebra and

$\widetilde {\mathcal {A}}$

be another C*-algebra and

$\widetilde {\rho }$

as above; Let further

$\widetilde {\rho }$

as above; Let further

$\widetilde {\omega _1},\widetilde {\omega _2}$

be two

$\widetilde {\omega _1},\widetilde {\omega _2}$

be two

$\widetilde \rho $

-locally comparable pure states on

$\widetilde \rho $

-locally comparable pure states on

$\widetilde {\mathcal {A}}$

which are

$\widetilde {\mathcal {A}}$

which are

$\widetilde {\rho }_t$

-invariant. Then (8)

$\widetilde {\rho }_t$

-invariant. Then (8) $$ \begin{align} \mathcal{N}_{\rho\otimes\widetilde{\rho}}\left(\omega_1\otimes\widetilde{\omega_1},\omega_2\otimes\widetilde{\omega_2}\right) = \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_2) + \mathcal{N}_{\widetilde{\rho}}(\widetilde{\omega_1},\widetilde{\omega_2}). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{N}_{\rho\otimes\widetilde{\rho}}\left(\omega_1\otimes\widetilde{\omega_1},\omega_2\otimes\widetilde{\omega_2}\right) = \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_2) + \mathcal{N}_{\widetilde{\rho}}(\widetilde{\omega_1},\widetilde{\omega_2}). \end{align} $$

To clarify further, let us assume temporarily that

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

is a uniformly hyperfinite (UHF) algebra. In this case, it is well known (see, e.g., [Reference Bratteli and William Robinson19, Prop 3.2.52]) that one may find a sequence

$\mathcal {A}$

is a uniformly hyperfinite (UHF) algebra. In this case, it is well known (see, e.g., [Reference Bratteli and William Robinson19, Prop 3.2.52]) that one may find a sequence

![]() $\{q_n=q_n^\ast \}_n\subseteq \mathcal {A}$

such that

$\{q_n=q_n^\ast \}_n\subseteq \mathcal {A}$

such that

Then it is clear that

Since this expression does not involve the unitary u the index is well-defined. The remainder of this subsection does not assume that

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

is UHF.

$\mathcal {A}$

is UHF.

Remark 2.6. If

![]() $(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

are

$(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

are

![]() $\rho $

-locally comparable and if

$\rho $

-locally comparable and if

![]() $\tilde \omega _2 = \omega _2\circ \mathrm {Ad}_v$

for a

$\tilde \omega _2 = \omega _2\circ \mathrm {Ad}_v$

for a

![]() $v\in {\mathcal U}({{\mathcal A}})$

with

$v\in {\mathcal U}({{\mathcal A}})$

with

![]() $\delta ^\rho (v)=0$

, then

$\delta ^\rho (v)=0$

, then

![]() $(\omega _1,\tilde \omega _2)$

are also

$(\omega _1,\tilde \omega _2)$

are also

![]() $\rho $

-locally comparable and

$\rho $

-locally comparable and

by additivity (6) and

![]() ${\mathcal N}_\rho (\tilde \omega _2, \omega _2) = 0$

.

${\mathcal N}_\rho (\tilde \omega _2, \omega _2) = 0$

.

Proof of Theorem 2.5.

(i) If we have

![]() $\omega _2 = \omega _1\circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u} = \omega _1\circ \operatorname {Ad}_{v}$

for two a priori distinct unitaries

$\omega _2 = \omega _1\circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u} = \omega _1\circ \operatorname {Ad}_{v}$

for two a priori distinct unitaries

![]() $u,v\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

then this readily implies

$u,v\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

then this readily implies

![]() $\omega _1 = \omega _1 \circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u^\ast v}$

. Let us define

$\omega _1 = \omega _1 \circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u^\ast v}$

. Let us define

![]() $w := u^\ast v$

whence

$w := u^\ast v$

whence

![]() $\omega _1= \omega _1\circ \operatorname {Ad}_{w}$

. Since

$\omega _1= \omega _1\circ \operatorname {Ad}_{w}$

. Since

![]() $v = uw $

, we have

$v = uw $

, we have

Applying

![]() $\omega _1$

to both sides of this and using the w-invariance of

$\omega _1$

to both sides of this and using the w-invariance of

![]() $\omega _1$

, it remains to show that

$\omega _1$

, it remains to show that

![]() $\omega _1(w^\ast \delta ^\rho (w)) =0$

to get the statement. Using Lemma 2.7 below we have that

$\omega _1(w^\ast \delta ^\rho (w)) =0$

to get the statement. Using Lemma 2.7 below we have that

Defining ![]() , we calculate

, we calculate

where we have used that ![]() . Now by Cauchy-Schwarz,

. Now by Cauchy-Schwarz,

for all

![]() $a\in \mathcal {A}$

which shows that

$a\in \mathcal {A}$

which shows that

![]() $\ker \omega _1$

is a two-sided *-ideal within

$\ker \omega _1$

is a two-sided *-ideal within

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

. Hence

$\mathcal {A}$

. Hence

where we used that

![]() $\omega _1\circ \delta ^\rho = 0$

since

$\omega _1\circ \delta ^\rho = 0$

since

![]() $\omega _1$

is invariant under

$\omega _1$

is invariant under

![]() $\rho _t$

in the second equality and (12) in the last equality.

$\rho _t$

in the second equality and (12) in the last equality.

(ii) Let

![]() $(\mathcal {H}_1,\pi _1,\Omega _1)$

be the GNS triplet associated with

$(\mathcal {H}_1,\pi _1,\Omega _1)$

be the GNS triplet associated with

![]() $\omega _1$

. Let

$\omega _1$

. Let

![]() $Q_1$

be the self-adjoint operator on

$Q_1$

be the self-adjoint operator on

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

such that

$\mathcal {H}_1$

such that

![]() $\mathrm {e}^{\mathrm {i} t Q_1}$

implements

$\mathrm {e}^{\mathrm {i} t Q_1}$

implements

![]() $\rho _t$

; see Lemma 2.8 right below. By construction,

$\rho _t$

; see Lemma 2.8 right below. By construction,

![]() $Q_1\Omega _1 = 0$

.

$Q_1\Omega _1 = 0$

.

We claim that

![]() $\Omega _2:=\pi _1(u)\Omega _1$

is also an eigenvector of

$\Omega _2:=\pi _1(u)\Omega _1$

is also an eigenvector of

![]() $Q_1$

, namely

$Q_1$

, namely

![]() $Q_1\Omega _2=n\Omega _2$

for some

$Q_1\Omega _2=n\Omega _2$

for some

![]() $n\in \mathbb {Z}$

since

$n\in \mathbb {Z}$

since

![]() $Q_1$

has integer spectrum. To see this we proceed as follows. Since

$Q_1$

has integer spectrum. To see this we proceed as follows. Since

![]() $(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

is a locally comparable pair,

$(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

is a locally comparable pair,

![]() $\omega _2$

is a vector state in

$\omega _2$

is a vector state in

![]() ${\mathcal H}_1$

, namely the vector

${\mathcal H}_1$

, namely the vector

![]() $\Omega _2 \equiv \pi _1(u) \Omega _1$

is such that

$\Omega _2 \equiv \pi _1(u) \Omega _1$

is such that

Moreover,

![]() $\omega _2\circ \rho _t=\omega _2$

implies, after going to the GNS representation and taking the derivative with respect to t at

$\omega _2\circ \rho _t=\omega _2$

implies, after going to the GNS representation and taking the derivative with respect to t at

![]() $0$

, that

$0$

, that

since

![]() $\Omega _2$

is in the domain of

$\Omega _2$

is in the domain of

![]() $Q_1$

. We may take A to be the orthogonal projection onto

$Q_1$

. We may take A to be the orthogonal projection onto

![]() $\operatorname {span}(\Psi )$

for some

$\operatorname {span}(\Psi )$

for some

![]() $\Psi \in \mathcal {H}_1$

to conclude that

$\Psi \in \mathcal {H}_1$

to conclude that

Now if

![]() $\Omega _2$

is not an eigenvector of

$\Omega _2$

is not an eigenvector of

![]() $Q_1$

, then there is a nonzero

$Q_1$

, then there is a nonzero

![]() $\Phi \in \operatorname {span}(\Omega _2)^\perp $

such that

$\Phi \in \operatorname {span}(\Omega _2)^\perp $

such that

for some

![]() $\lambda \in \mathbb {C}$

. Actually

$\lambda \in \mathbb {C}$

. Actually

![]() $\lambda \in \mathbb {R}$

because

$\lambda \in \mathbb {R}$

because

![]() $Q_1$

is self-adjoint. Now if we invoke (13) with

$Q_1$

is self-adjoint. Now if we invoke (13) with

![]() $\Psi =\Omega _2 +\operatorname {i} \Phi $

we obtain

$\Psi =\Omega _2 +\operatorname {i} \Phi $

we obtain

$$ \begin{align*} \mathbb{R} \ni &\:\langle \Omega_2, Q_1\left(\Omega_2+\operatorname{i}\Phi\right) \rangle\langle \Omega_2+\operatorname{i}\Phi, \Omega_2 \rangle = \langle \lambda \Omega_2 + \Phi, \Omega_2+\operatorname{i}\Phi \rangle \left\Vert \Omega_2 \right\Vert{}^2\\ &=\left(\lambda\left\Vert \Omega_2 \right\Vert{}^2+\operatorname{i}\left\Vert \Phi \right\Vert{}^2\right) \left\Vert \Omega_2 \right\Vert{}^2, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \mathbb{R} \ni &\:\langle \Omega_2, Q_1\left(\Omega_2+\operatorname{i}\Phi\right) \rangle\langle \Omega_2+\operatorname{i}\Phi, \Omega_2 \rangle = \langle \lambda \Omega_2 + \Phi, \Omega_2+\operatorname{i}\Phi \rangle \left\Vert \Omega_2 \right\Vert{}^2\\ &=\left(\lambda\left\Vert \Omega_2 \right\Vert{}^2+\operatorname{i}\left\Vert \Phi \right\Vert{}^2\right) \left\Vert \Omega_2 \right\Vert{}^2, \end{align*} $$

which is a contradiction unless

![]() $\Phi =0$

. Hence

$\Phi =0$

. Hence

![]() $\Omega _2$

is an eigenvector of

$\Omega _2$

is an eigenvector of

![]() $Q_1$

, which has integer spectrum, so

$Q_1$

, which has integer spectrum, so

(iii) Using the same GNS notation as above, if

![]() $\mathcal {N}_\rho (\omega _1,\omega _2)\neq 0$

then

$\mathcal {N}_\rho (\omega _1,\omega _2)\neq 0$

then

![]() $\Omega _2$

has a nonzero eigenvalue for

$\Omega _2$

has a nonzero eigenvalue for

![]() $Q_1$

. Since

$Q_1$

. Since

![]() $Q_1$

is a self-adjoint operator and

$Q_1$

is a self-adjoint operator and

![]() $\Omega _1$

is a zero-eigenvalue eigenvector for

$\Omega _1$

is a zero-eigenvalue eigenvector for

![]() $Q_1$

, this implies that

$Q_1$

, this implies that

![]() $\langle \Omega _2, \Omega _1 \rangle =0$

.

$\langle \Omega _2, \Omega _1 \rangle =0$

.

On the other hand, since both states

![]() $\omega _1,\omega _2$

are represented as vector states on the same Hilbert space, we have

$\omega _1,\omega _2$

are represented as vector states on the same Hilbert space, we have

![]() $\left \Vert \omega _1-\omega _2 \right \Vert =\sup _{a\in \mathcal {A}:\left \Vert a \right \Vert \leq 1} \left \lvert {\langle \Omega _1, \pi _1(a)\Omega _1 \rangle - \langle \Omega _2, \pi _1(a)\Omega _2 \rangle } \right \rvert $

. Denoting

$\left \Vert \omega _1-\omega _2 \right \Vert =\sup _{a\in \mathcal {A}:\left \Vert a \right \Vert \leq 1} \left \lvert {\langle \Omega _1, \pi _1(a)\Omega _1 \rangle - \langle \Omega _2, \pi _1(a)\Omega _2 \rangle } \right \rvert $

. Denoting

![]() $P_j$

is the orthogonal projection onto the span of

$P_j$

is the orthogonal projection onto the span of

![]() $\Omega _{\omega _j}$

for

$\Omega _{\omega _j}$

for

![]() $j=1,2$

, we have

$j=1,2$

, we have

The second equality is by duality since

![]() $\pi _1$

is irreducible, as

$\pi _1$

is irreducible, as

![]() $\omega _1$

is pure. Since

$\omega _1$

is pure. Since

![]() $P_j$

are one-dimensional projections, the trace norm is easily computable and we conclude that

$P_j$

are one-dimensional projections, the trace norm is easily computable and we conclude that

Hence,

We note in passing that the reader may want to compare this with a related converse statement about unitary equivalence of the states when

![]() $\left \Vert \omega _1-\omega _2 \right \Vert <2$

, see [Reference Glimm and Kadison29, Corollary 9, Remark 10].

$\left \Vert \omega _1-\omega _2 \right \Vert <2$

, see [Reference Glimm and Kadison29, Corollary 9, Remark 10].

(iv) Since

![]() $(\omega _2,\omega _1)$

are

$(\omega _2,\omega _1)$

are

![]() $\rho $

-locally comparable, there is

$\rho $

-locally comparable, there is

![]() $u\in {{\mathcal A}}\cap {\mathcal D}(\delta ^\rho )$

such that

$u\in {{\mathcal A}}\cap {\mathcal D}(\delta ^\rho )$

such that

![]() $\omega _2 = \omega _1\circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

. Therefore,

$\omega _2 = \omega _1\circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

. Therefore,

so that

![]() $(\omega _2\circ \alpha ,\omega _1\circ \alpha )$

are locally comparable. They are in fact

$(\omega _2\circ \alpha ,\omega _1\circ \alpha )$

are locally comparable. They are in fact

![]() $\rho $

-locally comparable since

$\rho $

-locally comparable since

![]() $\alpha $

commutes with

$\alpha $

commutes with

![]() $\delta ^\rho $

and so

$\delta ^\rho $

and so

![]() $\alpha ^{-1}({\mathcal D}(\delta ^\rho ))\subset {\mathcal D}(\delta ^\rho )$

. The computation

$\alpha ^{-1}({\mathcal D}(\delta ^\rho ))\subset {\mathcal D}(\delta ^\rho )$

. The computation

yields the invariance.

(v) By (i), we can pick ![]() , for which

, for which

![]() $\delta ^\rho (u)=0$

and so the index vanishes.

$\delta ^\rho (u)=0$

and so the index vanishes.

(vi) To get the additivity of the index, assume that

![]() $\omega _2 = \omega _1 \circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

and

$\omega _2 = \omega _1 \circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

and

![]() $\omega _3 = \omega _2 \circ \operatorname {ad}_{v}$

. Hence

$\omega _3 = \omega _2 \circ \operatorname {ad}_{v}$

. Hence

![]() $\omega _3 = \omega _1 \circ \operatorname {Ad}_{v u}$

so that

$\omega _3 = \omega _1 \circ \operatorname {Ad}_{v u}$

so that

$$ \begin{align*} \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_3) &= \operatorname{i} \omega_1\left(\left(vu\right)^\ast\delta^\rho\left(vu\right)\right) \\ &= \operatorname{i} \omega_1\left(u^\ast v^\ast\left(\left(\delta^\rho (v)\right)u+v\delta^\rho (u)\right)\right) \\ &= \operatorname{i} \omega_2(v^\ast \delta^\rho (v)) +\operatorname{i} \omega_1(u^\ast \delta^\rho (u))\\ &= \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_2,\omega_3) + \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_2). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_3) &= \operatorname{i} \omega_1\left(\left(vu\right)^\ast\delta^\rho\left(vu\right)\right) \\ &= \operatorname{i} \omega_1\left(u^\ast v^\ast\left(\left(\delta^\rho (v)\right)u+v\delta^\rho (u)\right)\right) \\ &= \operatorname{i} \omega_2(v^\ast \delta^\rho (v)) +\operatorname{i} \omega_1(u^\ast \delta^\rho (u))\\ &= \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_2,\omega_3) + \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_2). \end{align*} $$

Finally, (vii) follows from (vi) with

![]() $\omega _3 = \omega _1$

and (v).

$\omega _3 = \omega _1$

and (v).

(viii) The result follows immediately since

![]() $\delta ^{\rho \otimes \widetilde {\rho }} = \delta ^\rho \otimes \mathrm {id}+\mathrm {id}\otimes \delta ^{\widetilde {\rho }}$

.

$\delta ^{\rho \otimes \widetilde {\rho }} = \delta ^\rho \otimes \mathrm {id}+\mathrm {id}\otimes \delta ^{\widetilde {\rho }}$

.

Lemma 2.7. Let

![]() $\omega \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {A})$

and

$\omega \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {A})$

and

![]() $u\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

be such that

$u\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

be such that

![]() $\omega =\omega \circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

. Then

$\omega =\omega \circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

. Then

![]() $\omega (u)\in U(1)$

.

$\omega (u)\in U(1)$

.

Proof. Let

![]() $(\mathcal {H},\pi ,\Omega )$

be the GNS representation of

$(\mathcal {H},\pi ,\Omega )$

be the GNS representation of

![]() $\omega $

. Then the invariance condition implies

$\omega $

. Then the invariance condition implies

We find that both

![]() $\Omega $

and

$\Omega $

and

![]() $\pi (u)\Omega $

are cyclic vectors that generate the same state, where

$\pi (u)\Omega $

are cyclic vectors that generate the same state, where

![]() $\pi $

is irreducible as

$\pi $

is irreducible as

![]() $\omega $

is pure. This implies that

$\omega $

is pure. This implies that

![]() $\pi (u)\Omega = {\mathrm e}^{\operatorname {i}\theta }\Omega $

for some

$\pi (u)\Omega = {\mathrm e}^{\operatorname {i}\theta }\Omega $

for some

![]() $\theta \in \mathbb {R}$

and so

$\theta \in \mathbb {R}$

and so

![]() $\omega (u) = \langle \Omega , \pi (u)\Omega \rangle = {\mathrm e}^{\operatorname {i}\theta }$

as claimed.

$\omega (u) = \langle \Omega , \pi (u)\Omega \rangle = {\mathrm e}^{\operatorname {i}\theta }$

as claimed.

Lemma 2.8. Let

![]() $\{\rho _t\}_{t\in \mathbb {R}}\subseteq \operatorname {Aut}(\mathcal {A})$

be a one-parameter group of strongly continuous automorphisms such that

$\{\rho _t\}_{t\in \mathbb {R}}\subseteq \operatorname {Aut}(\mathcal {A})$

be a one-parameter group of strongly continuous automorphisms such that ![]() and let

and let

![]() $\omega \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {A})$

be

$\omega \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {A})$

be

![]() $\rho $

-invariant. Then in the GNS representation

$\rho $

-invariant. Then in the GNS representation

![]() $(\mathcal {H}_{\omega },\pi _{\omega },\Omega _{\omega })$

of

$(\mathcal {H}_{\omega },\pi _{\omega },\Omega _{\omega })$

of

![]() $\omega $

, there exists a self-adjoint operator

$\omega $

, there exists a self-adjoint operator

![]() $Q_{\omega }:\mathcal {H}_{\omega }\to \mathcal {H}_{\omega }$

such that

$Q_{\omega }:\mathcal {H}_{\omega }\to \mathcal {H}_{\omega }$

such that

One may choose

![]() $Q_{\omega }$

such that

$Q_{\omega }$

such that

![]() $Q_{\omega }\Omega _\omega = 0$

, in which case

$Q_{\omega }\Omega _\omega = 0$

, in which case

![]() $\sigma (Q_{\omega })\subseteq \mathbb {Z}$

.

$\sigma (Q_{\omega })\subseteq \mathbb {Z}$

.

Proof. For any

![]() $t\in {\mathbb R}$

, the existence of a unitary implementer

$t\in {\mathbb R}$

, the existence of a unitary implementer

![]() $U_{\omega ,t}$

of

$U_{\omega ,t}$

of

![]() $\rho _t$

is a standard consequence of the uniqueness of the GNS representation. Strong continuity of

$\rho _t$

is a standard consequence of the uniqueness of the GNS representation. Strong continuity of

![]() $t\mapsto \rho _t$

implies strong continuity of

$t\mapsto \rho _t$

implies strong continuity of

![]() $t\mapsto U_{\omega ,t}$

, and the existence of a self-adjoint generator

$t\mapsto U_{\omega ,t}$

, and the existence of a self-adjoint generator

![]() $Q_\omega $

is ensured by Stone’s theorem. Since

$Q_\omega $

is ensured by Stone’s theorem. Since

![]() $\omega $

is pure,

$\omega $

is pure,

![]() $\pi _{\omega }$

is irreducible and hence

$\pi _{\omega }$

is irreducible and hence

![]() $Q_\omega $

is defined up to an additive constant. The invariance of

$Q_\omega $

is defined up to an additive constant. The invariance of

![]() $\omega $

yields that

$\omega $

yields that

![]() $\Omega _{\omega }$

is an eigenvector of

$\Omega _{\omega }$

is an eigenvector of

![]() $Q_\omega $

, which can be fixed by imposing

$Q_\omega $

, which can be fixed by imposing

![]() $Q_\omega \Omega _{\omega }=0$

. With this, for any

$Q_\omega \Omega _{\omega }=0$

. With this, for any

![]() $a\in {{\mathcal A}}$

,

$a\in {{\mathcal A}}$

,

![]() $\mathrm {e}^{2\pi \mathrm {i} Q_\omega }\pi _{\omega }(a)\Omega _{\omega } = \pi _{\omega }(\rho _{2\pi }(a))\Omega _{\omega } = \pi _{\omega }(a)\Omega _{\omega }$

, which implies that

$\mathrm {e}^{2\pi \mathrm {i} Q_\omega }\pi _{\omega }(a)\Omega _{\omega } = \pi _{\omega }(\rho _{2\pi }(a))\Omega _{\omega } = \pi _{\omega }(a)\Omega _{\omega }$

, which implies that ![]() by cyclicity of GNS representation, so that

by cyclicity of GNS representation, so that

![]() $\sigma (Q_\omega )\subseteq \mathbb {Z}$

.

$\sigma (Q_\omega )\subseteq \mathbb {Z}$

.

Remark 2.9. The assumption of local-comparability and the standard Lemma 2.8 immediately imply that the index of just the difference of eigenvalues of a charge operator which has integer spectrum, see (14), and hence the name ‘charge deficiency’. The interest of phrasing our result in the abstract algebraic setting is two-fold. First of all, as we shall see in Section 3, establishing the

![]() $\rho $

-local-comparability of two states is the essence of the problem in applications. Secondly, it allows us to phrase the automorphic invariance (5) since the states

$\rho $

-local-comparability of two states is the essence of the problem in applications. Secondly, it allows us to phrase the automorphic invariance (5) since the states

![]() $\omega _1$

and

$\omega _1$

and

![]() $\omega _1\circ \alpha $

are not in general unitarily equivalent and therefore not representable as vector states in each other’s GNS representation.

$\omega _1\circ \alpha $

are not in general unitarily equivalent and therefore not representable as vector states in each other’s GNS representation.

Of course, the lemma also shows that the period

![]() $2\pi $

of the group

$2\pi $

of the group

![]() $\rho _t$

is, at least mathematically, an arbitrary choice: If instead

$\rho _t$

is, at least mathematically, an arbitrary choice: If instead

![]() $\rho _{2\pi /\lambda }=\mathrm {id}$

for some

$\rho _{2\pi /\lambda }=\mathrm {id}$

for some

![]() $\lambda>0$

(but keeping Q with integer spectrum) then

$\lambda>0$

(but keeping Q with integer spectrum) then

![]() $\widetilde {\mathcal {N}_\rho }(\omega _1,\omega _2):=\lambda ^{-1}\mathcal {N}_\rho (\omega _1,\omega _2)\in \mathbb {Z}$

. Finally, we emphasize again that the requirement that the intertwining unitary u obey

$\widetilde {\mathcal {N}_\rho }(\omega _1,\omega _2):=\lambda ^{-1}\mathcal {N}_\rho (\omega _1,\omega _2)\in \mathbb {Z}$

. Finally, we emphasize again that the requirement that the intertwining unitary u obey

![]() $u\in \mathcal {D}(\delta ^\rho )$

is not vacuous with the following example.

$u\in \mathcal {D}(\delta ^\rho )$

is not vacuous with the following example.

Example 2.10. Let

![]() $\mathcal {A}=\operatorname {CAR}(\ell ^2(\mathbb {N}))$

with

$\mathcal {A}=\operatorname {CAR}(\ell ^2(\mathbb {N}))$

with

![]() $\{e_j\}_{j\geq 1}$

the canonical position basis of

$\{e_j\}_{j\geq 1}$

the canonical position basis of

![]() $\ell ^2(\mathbb {N})$

so

$\ell ^2(\mathbb {N})$

so

![]() $a_j\equiv a(e_j)$

are the annihilation operators associated with those basis elements. Then

$a_j\equiv a(e_j)$

are the annihilation operators associated with those basis elements. Then

$$ \begin{align*} q_N := \sum_{j=1}^N a_j^{*} a_j \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} q_N := \sum_{j=1}^N a_j^{*} a_j \end{align*} $$

defines a sequence of bounded self-adjoint elements in

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

which approximates a derivation

$\mathcal {A}$

which approximates a derivation

![]() $\delta $

as

$\delta $

as

where

![]() $\mathcal {D}(\delta )$

is the space of elements a for which the limit exists. Define

$\mathcal {D}(\delta )$

is the space of elements a for which the limit exists. Define

$$ \begin{align*} a := \sum_{j=1}^\infty j^{-3/2} a_1^\ast \cdots a_j^\ast \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} a := \sum_{j=1}^\infty j^{-3/2} a_1^\ast \cdots a_j^\ast \end{align*} $$

which exists since

![]() $\left \Vert a \right \Vert \leq \sum _j j^{-3/2} < \infty $

. We may then calculate

$\left \Vert a \right \Vert \leq \sum _j j^{-3/2} < \infty $

. We may then calculate

and hence

$$ \begin{align*} [q_N, a] = \sum_{j=1}^N j^{-1/2} a_1^\ast \cdots a_j^\ast + N \sum_{j=N}^\infty j^{-3/2} a_1^\ast \cdots a_j^\ast. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} [q_N, a] = \sum_{j=1}^N j^{-1/2} a_1^\ast \cdots a_j^\ast + N \sum_{j=N}^\infty j^{-3/2} a_1^\ast \cdots a_j^\ast. \end{align*} $$

We see that the limit

![]() $N\to \infty $

of the above expression does not exist so that

$N\to \infty $

of the above expression does not exist so that

![]() $a\notin \mathcal {D}(\delta )$

.

$a\notin \mathcal {D}(\delta )$

.

Now take

![]() $h := a + a^\ast $

and

$h := a + a^\ast $

and ![]() to get a unitary element which is not in

to get a unitary element which is not in

![]() $\mathcal {D}(\delta )$

. As a result, for any

$\mathcal {D}(\delta )$

. As a result, for any

![]() $\omega \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {A})$

we may define

$\omega \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {A})$

we may define

![]() $\widetilde {\omega } := \omega \circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

such that

$\widetilde {\omega } := \omega \circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

such that

![]() $\omega ,\widetilde \omega $

are locally comparable but not

$\omega ,\widetilde \omega $

are locally comparable but not

![]() $\rho $

-locally comparable.

$\rho $

-locally comparable.

2.2 Connection with the index of a pair of projections on a Hilbert space

Let

![]() $\mathcal {H}$

be a separable Hilbert space and

$\mathcal {H}$

be a separable Hilbert space and

![]() $P_1,P_2$

be two self-adjoint projections such that

$P_1,P_2$

be two self-adjoint projections such that

In this setting it is well-known that a topological index is associated with the pair

![]() $(P_1,P_2)$

(see, e.g., [Reference Avron, Seiler and Simon7] and earlier citations within) given by

$(P_1,P_2)$

(see, e.g., [Reference Avron, Seiler and Simon7] and earlier citations within) given by

where the index on the right-hand sides is the Fredholm index and U is any unitary

![]() $U:\operatorname {im}(P_1^\perp )\to \operatorname {im}(P_2^\perp )$

. In the special case that

$U:\operatorname {im}(P_1^\perp )\to \operatorname {im}(P_2^\perp )$

. In the special case that

![]() $P-Q\in \mathcal {J}_p({\mathcal H})$

, the ideal of p-Schatten class operators, for some p, we may also write

$P-Q\in \mathcal {J}_p({\mathcal H})$

, the ideal of p-Schatten class operators, for some p, we may also write

for any

![]() $p'\in \mathbb {N}$

such that

$p'\in \mathbb {N}$

such that

![]() $2p'+1\geq p$

. Finally, if

$2p'+1\geq p$

. Finally, if

![]() $P_1-P_2\in \mathcal {J}_2({\mathcal H})$

then by [Reference Arveson4, Theorem 3], we may write

$P_1-P_2\in \mathcal {J}_2({\mathcal H})$

then by [Reference Arveson4, Theorem 3], we may write

We turn to the relation of

![]() $\operatorname {index}(P_1,P_2)$

with the newly introduced many-body index

$\operatorname {index}(P_1,P_2)$

with the newly introduced many-body index

![]() ${\mathcal N}_\rho (\omega _1,\omega _2)$

.

${\mathcal N}_\rho (\omega _1,\omega _2)$

.

Remark 2.11. Since any two projections

![]() $P_1,P_2$

on an infinite-dimensional Hilbert space with infinite

$P_1,P_2$

on an infinite-dimensional Hilbert space with infinite

![]() $\ker P_j,\,\operatorname {im} P_j$

admit a unitary U which conjugates them, that is,

$\ker P_j,\,\operatorname {im} P_j$

admit a unitary U which conjugates them, that is,

![]() $P_2 = U^\ast P_1 U$

, one may be tempted to conclude that if

$P_2 = U^\ast P_1 U$

, one may be tempted to conclude that if

![]() $P-Q$

is “small” then so is

$P-Q$

is “small” then so is ![]() (so as to have any hope to implement it in

(so as to have any hope to implement it in

![]() $\mathcal {A})$

. However, it is well-known (see, e.g., [Reference Loreaux and Ng41, Theorem 1.2] or [Reference Brown, Douglas and Fillmore21]) that a unitary

$\mathcal {A})$

. However, it is well-known (see, e.g., [Reference Loreaux and Ng41, Theorem 1.2] or [Reference Brown, Douglas and Fillmore21]) that a unitary

![]() $U\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {H})$

can be found such that both

$U\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {H})$

can be found such that both ![]() and

and

![]() $P_2=U^\ast P_1 U$

iff

$P_2=U^\ast P_1 U$

iff

This indicates that to capture a nontrivial index we most likely need to find a unitary in the CAR algebra which is not the second quantization of a Hilbert space one.

As we shall see below, there will be additional obstructions beyond the purely Hilbert space index obstruction.

Let now

![]() $\mathcal {A}=\operatorname {CAR}(\mathcal {H})$

(see Section 3.2 for more details) be the algebra of observables corresponding to systems of many fermions. Any self-adjoint projection P induces a pure state

$\mathcal {A}=\operatorname {CAR}(\mathcal {H})$

(see Section 3.2 for more details) be the algebra of observables corresponding to systems of many fermions. Any self-adjoint projection P induces a pure state

![]() $\omega _{P}\in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {A})$

, the so-called quasi-free state associated to P, given by the Gaussian formula

$\omega _{P}\in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {A})$

, the so-called quasi-free state associated to P, given by the Gaussian formula

where

![]() $f_i,g_i\in \mathcal {H}$

, and extended linearly to all polynomials and by continuity to all of

$f_i,g_i\in \mathcal {H}$

, and extended linearly to all polynomials and by continuity to all of

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

.

$\mathcal {A}$

.

The canonical ‘charge’

![]() $U(1)$

*-automorphism

$U(1)$

*-automorphism

![]() $\rho _t$

is defined by

$\rho _t$

is defined by

for any

![]() $f\in \mathcal {H}$

and

$f\in \mathcal {H}$

and

![]() $t\in {\mathbb R}$

. Note that

$t\in {\mathbb R}$

. Note that ![]() . For any orthogonal projection P, the state

. For any orthogonal projection P, the state

![]() $\omega _P$

is automatically invariant under

$\omega _P$

is automatically invariant under

![]() $\rho _t$

.

$\rho _t$

.

To contextualize the ensuing discussion, let us recall a few basic facts:

-

(i) The Shale-Stinespring condition for quasi-free states on CAR(

$\mathcal {H}$

) [Reference Shale and Forrest Stinespring44]:

$\mathcal {H}$

) [Reference Shale and Forrest Stinespring44]:

$\omega _{P_1},\omega _{P_2}$

have unitarily equivalent GNS representations if and only if

$\omega _{P_1},\omega _{P_2}$

have unitarily equivalent GNS representations if and only if

$P_1-P_2 \in {\mathcal J}_2({\mathcal H})$

.

$P_1-P_2 \in {\mathcal J}_2({\mathcal H})$

. -

(ii) The Kadison transitivity theorem for general C*-algebras [Reference Glimm and Kadison29, Corollary 8]: If two pure states

$\omega ,\widetilde {\omega }\in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {A})$

have unitarily equivalent GNS representations then there exists some

$\omega ,\widetilde {\omega }\in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {A})$

have unitarily equivalent GNS representations then there exists some

$u\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

such that

$u\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

such that

$\widetilde {\omega } = \omega \circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

.

$\widetilde {\omega } = \omega \circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

. -

(iii) The condition on Bogoliubov automorphisms of CAR

$(\mathcal {H})$

to be inner [Reference Araki2, Theorem 5]:

$(\mathcal {H})$

to be inner [Reference Araki2, Theorem 5]:  if and only if

if and only if

$\exists {\Gamma }(U)\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

such that

$\exists {\Gamma }(U)\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

such that

$a(Uf) = {\Gamma }(U)^{*} a(f){\Gamma }(U)$

for all

$a(Uf) = {\Gamma }(U)^{*} a(f){\Gamma }(U)$

for all

$f\in \mathcal {H}$

.

$f\in \mathcal {H}$

.

We are now ready to connect the index in (18) with the one defined in (3). For this, given the basic facts stated above, and in particular (iii), we need to strengthen the assumption on

![]() $P_1-P_2$

from compact to trace-class.

$P_1-P_2$

from compact to trace-class.

Theorem 2.12. Let

![]() $P_1,P_2$

be self-adjoint projections such that

$P_1,P_2$

be self-adjoint projections such that

Then

![]() $\omega _{P_1}$

and

$\omega _{P_1}$

and

![]() $\omega _{P_2}$

are

$\omega _{P_2}$

are

![]() $\rho $

-locally comparable and

$\rho $

-locally comparable and

This theorem identifies

![]() $\mathcal {N}_\rho $

as the many-body analog of the notion of an index of pair of projections, albeit with a certain mathematical gap: if

$\mathcal {N}_\rho $

as the many-body analog of the notion of an index of pair of projections, albeit with a certain mathematical gap: if

![]() $P_1-P_2\in \mathcal {K}(\mathcal {H})$

but is not Hilbert-Schmidt, then by the above basic facts

$P_1-P_2\in \mathcal {K}(\mathcal {H})$

but is not Hilbert-Schmidt, then by the above basic facts

![]() $\omega _{P_1}$

and

$\omega _{P_1}$

and

![]() $\omega _{P_2}$

cannot be locally comparable: indeed, if they were, they would be GNS unitarily equivalent and hence violate the Shale-Stinespring condition. If

$\omega _{P_2}$

cannot be locally comparable: indeed, if they were, they would be GNS unitarily equivalent and hence violate the Shale-Stinespring condition. If

![]() $P_1-P_2$

is Hilbert-Schmidt but not trace-class, then by the above there would be a unitary conjugating them in the CAR algebra, but since that unitary is given abstractly by the Kadison transitivity theorem and is not the second quantization of any unitary, we do not know how to establish that that unitary necessarily lies in the domain of

$P_1-P_2$

is Hilbert-Schmidt but not trace-class, then by the above there would be a unitary conjugating them in the CAR algebra, but since that unitary is given abstractly by the Kadison transitivity theorem and is not the second quantization of any unitary, we do not know how to establish that that unitary necessarily lies in the domain of

![]() $\delta ^\rho $

.

$\delta ^\rho $

.

Ultimately, a generalization of the many-body index may exist, which relies on a weaker condition that

![]() $(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

be locally comparable, and which would always be defined for quasi-free states

$(\omega _1,\omega _2)$

be locally comparable, and which would always be defined for quasi-free states

![]() $(\omega _{P_1},\omega _{P_2})$

as soon as

$(\omega _{P_1},\omega _{P_2})$

as soon as

![]() $P_1-P_2\in \mathcal {K}$

. This problem is not entirely academic since in the interesting case of the integer quantum Hall effect,

$P_1-P_2\in \mathcal {K}$

. This problem is not entirely academic since in the interesting case of the integer quantum Hall effect,

![]() $P-L^\ast P L\in \mathcal {J}_3\setminus \mathcal {J}_2$

where

$P-L^\ast P L\in \mathcal {J}_3\setminus \mathcal {J}_2$

where

is the Laughlin unitary [Reference Avron, Seiler and Simon6] implementing one quanta of a magnetic flux insertion. See also Example 2.14 below for a simple example of this type.

Example 2.13 (Nonzero index yet unitary exists thanks to interactions).

The obstruction outlined in Remark 2.11 does not imply that we cannot implement nonzero indices. Indeed, pick

![]() $\mathcal {H} := \ell ^2(\mathbb {Z})$

and let P be the multiplication operator by the indicator function

$\mathcal {H} := \ell ^2(\mathbb {Z})$

and let P be the multiplication operator by the indicator function

![]() $\chi _{\mathbb {N}}$

, namely the projection onto the RHS of space. Let R be the bilateral right shift operator

$\chi _{\mathbb {N}}$

, namely the projection onto the RHS of space. Let R be the bilateral right shift operator

![]() $R:\delta _x\mapsto \delta _{x+1}$

. Then

$R:\delta _x\mapsto \delta _{x+1}$

. Then

![]() $P_R=R^\ast P R$

is the projection given by

$P_R=R^\ast P R$

is the projection given by

![]() $\chi _{\mathbb {N}\cup \{0\}}$

and

$\chi _{\mathbb {N}\cup \{0\}}$

and

![]() $P_R-P$

is the finite rank projection given by

$P_R-P$

is the finite rank projection given by

![]() $\chi _{\{0\}}$

, and

$\chi _{\{0\}}$

, and

![]() $\operatorname {index}(P,P_R) = -1$

. Of course this means

$\operatorname {index}(P,P_R) = -1$

. Of course this means

![]() $P-P_R \in \mathcal {J}_2({\mathcal H})$

, equivalently,

$P-P_R \in \mathcal {J}_2({\mathcal H})$

, equivalently,

![]() $[R,P]\in \mathcal {J}_2({\mathcal H})$

.

$[R,P]\in \mathcal {J}_2({\mathcal H})$

.

The operator

is unitary since ![]() , such that

, such that

and we claim that

Indeed, if

![]() $n,m\neq 0$

,

$n,m\neq 0$

,

and if

![]() $n=m=0$

then

$n=m=0$

then

while both

![]() $\omega _P(u^{*} a_m^\ast a_n u)$

and

$\omega _P(u^{*} a_m^\ast a_n u)$

and

![]() $\omega _{P_R}(a^{*}_m a_n)$

vanish if

$\omega _{P_R}(a^{*}_m a_n)$

vanish if

![]() $n\neq m$

. Since

$n\neq m$

. Since

we see that

![]() $u\in {\mathcal D}(\delta ^\rho )$

and

$u\in {\mathcal D}(\delta ^\rho )$

and

![]() $-\mathrm {i} \delta ^\rho (u) = -a_0 + a_0^{*}$

, so that

$-\mathrm {i} \delta ^\rho (u) = -a_0 + a_0^{*}$

, so that

Example 2.14 (Compact but not Hilbert-Schmidt difference of projections so no unitary exists).

Let

![]() $\mathcal {H} := \ell ^2(\mathbb {N})\otimes \mathbb {C}^2$

. Let P be given by

$\mathcal {H} := \ell ^2(\mathbb {N})\otimes \mathbb {C}^2$

. Let P be given by

$$ \begin{align*} P_{nm} := \delta_{nm} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} P_{nm} := \delta_{nm} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}, \end{align*} $$

that is, projection onto the top of each dimer. Let U be the unitary given by

$$ \begin{align*} U_{nm} := \delta_{nm} \begin{bmatrix} \cos(\theta_n) & \sin(\theta_n) \\ -\sin(\theta_n) & \cos(\theta_n) \end{bmatrix} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} U_{nm} := \delta_{nm} \begin{bmatrix} \cos(\theta_n) & \sin(\theta_n) \\ -\sin(\theta_n) & \cos(\theta_n) \end{bmatrix} \end{align*} $$

where

![]() $\{\theta _n\}_n$

is some sequence of angles to be determined below. If

$\{\theta _n\}_n$

is some sequence of angles to be determined below. If

![]() $Q := U^\ast P U$

, then

$Q := U^\ast P U$

, then

$$ \begin{align*} P_{nm}-Q_{nm}=\delta_{nm}\begin{bmatrix} \sin^{2}\theta_n & -\cos\theta_n\sin\theta_n\\ -\cos\theta_n\sin\theta_n & -\sin^{2}\theta_n \end{bmatrix}. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} P_{nm}-Q_{nm}=\delta_{nm}\begin{bmatrix} \sin^{2}\theta_n & -\cos\theta_n\sin\theta_n\\ -\cos\theta_n\sin\theta_n & -\sin^{2}\theta_n \end{bmatrix}. \end{align*} $$

Since the singular values of

![]() $P-Q$

are

$P-Q$

are

![]() $\{ \left \lvert {\sin (\theta _n)} \right \rvert \}_{n\geq 1}$

it is clear that if we pick

$\{ \left \lvert {\sin (\theta _n)} \right \rvert \}_{n\geq 1}$

it is clear that if we pick

![]() $\theta _n := \arcsin (x_n)$

for some sequence

$\theta _n := \arcsin (x_n)$

for some sequence

![]() $\{x_n\}_n\subseteq (0,1)$

we can engineer whichever summability we want. For example if we take

$\{x_n\}_n\subseteq (0,1)$

we can engineer whichever summability we want. For example if we take

![]() $x_n = n^{-\beta }$

for any

$x_n = n^{-\beta }$

for any

![]() $\beta \in (1/3,1/2]$

then we guarantee that

$\beta \in (1/3,1/2]$

then we guarantee that

![]() $\{x_n^2\}_n$

is not summable but

$\{x_n^2\}_n$

is not summable but

![]() $\{x_n^3\}_n$

is. Note that as soon as

$\{x_n^3\}_n$

is. Note that as soon as

![]() $x_n\to 0$

we have

$x_n\to 0$

we have

![]() $P-Q\in \mathcal {K}(\mathcal {H})$

.

$P-Q\in \mathcal {K}(\mathcal {H})$

.

Now, for

![]() $\{x_n\}_n$

in

$\{x_n\}_n$

in

![]() $\ell ^3$

but not

$\ell ^3$

but not

![]() $\ell ^2$

there does not exist a unitary

$\ell ^2$

there does not exist a unitary

![]() $u\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

such that

$u\in \mathcal {U}(\mathcal {A})$

such that

![]() $\omega _Q = \omega _P\circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

. Indeed, the existence of such a unitary would violate the Shale-Stinespring condition [Reference Shale and Forrest Stinespring44].

$\omega _Q = \omega _P\circ \operatorname {Ad}_{u}$

. Indeed, the existence of such a unitary would violate the Shale-Stinespring condition [Reference Shale and Forrest Stinespring44].

Before presenting the proof of Theorem 2.12, let us make a final remark. Suppose we knew that

![]() $\omega _1$

and

$\omega _1$

and

![]() $\omega _2$

(with

$\omega _2$

(with

![]() $\omega _j\equiv \omega _{P_j}$

) are

$\omega _j\equiv \omega _{P_j}$

) are

![]() $\rho $

-locally comparable. Then the equivalence of the two indices would be immediate. Indeed, starting from (9) and approximating

$\rho $

-locally comparable. Then the equivalence of the two indices would be immediate. Indeed, starting from (9) and approximating

![]() $\delta ^\rho = \lim _N\operatorname {i}[q_N,\cdot ]$

with

$\delta ^\rho = \lim _N\operatorname {i}[q_N,\cdot ]$

with

![]() $q_N := \sum _{j=1}^N a^{*}(e_j)a(e_j)$

where

$q_N := \sum _{j=1}^N a^{*}(e_j)a(e_j)$

where

![]() $\{e_j\}_j$

is any ONB of

$\{e_j\}_j$

is any ONB of

![]() $\mathcal {H}$

, we obtain using (20)

$\mathcal {H}$

, we obtain using (20)

$$ \begin{align*} \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_2) &= \lim_N \left(\omega_1(q_N) - \omega_2(q_N)\right) = \lim_N \sum_{j=1}^N\left(\langle e_j, P_1 e_j \rangle-\langle e_j, P_2e_j \rangle\right) \\ &= \lim_N \mathrm{tr}\left(\left(P_1-P_2\right)\chi_{\{1,\cdots,N\}}(X)\right) \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \mathcal{N}_\rho(\omega_1,\omega_2) &= \lim_N \left(\omega_1(q_N) - \omega_2(q_N)\right) = \lim_N \sum_{j=1}^N\left(\langle e_j, P_1 e_j \rangle-\langle e_j, P_2e_j \rangle\right) \\ &= \lim_N \mathrm{tr}\left(\left(P_1-P_2\right)\chi_{\{1,\cdots,N\}}(X)\right) \end{align*} $$

where X is the position operator w.r.t. the basis

![]() $\{e_j\}_j$

, that is,

$\{e_j\}_j$

, that is,

![]() $X e_j \equiv j e_j$

for any

$X e_j \equiv j e_j$

for any

![]() $j\in \mathbb {N}$

. Since we have

$j\in \mathbb {N}$

. Since we have ![]() strongly as

strongly as

![]() $N\to \infty $

, and since

$N\to \infty $

, and since

![]() $P_1-P_2\in \mathcal J_1$

we are finished, since the product of a strongly convergent sequence with a trace-class operator is a sequence converging in trace-class norm, that is, we find

$P_1-P_2\in \mathcal J_1$

we are finished, since the product of a strongly convergent sequence with a trace-class operator is a sequence converging in trace-class norm, that is, we find

We also note that in the case

![]() $P_1-P_2\in {\mathcal J}_2({\mathcal H})$

the proof given (using a particular choice of the ONB

$P_1-P_2\in {\mathcal J}_2({\mathcal H})$

the proof given (using a particular choice of the ONB

![]() $\{e_j\}_j$

) goes through by invoking the explicit formula (19). In the proof below, we rely on the trace-class assumption to construct the unitary intertwiner between

$\{e_j\}_j$

) goes through by invoking the explicit formula (19). In the proof below, we rely on the trace-class assumption to construct the unitary intertwiner between

![]() $\omega _1$

and

$\omega _1$

and

![]() $\omega _2$

, which lies in

$\omega _2$

, which lies in

![]() $\mathcal {D}(\delta ^\rho )$

. So the main difficulty is to establish the

$\mathcal {D}(\delta ^\rho )$

. So the main difficulty is to establish the

![]() $\rho $

-local-comparability of

$\rho $

-local-comparability of

![]() $\omega _1,\omega _2$

, that is, to find the unitary which conjugates them and show it lies in

$\omega _1,\omega _2$

, that is, to find the unitary which conjugates them and show it lies in

![]() $\mathcal {D}(\delta ^\rho )$

.

$\mathcal {D}(\delta ^\rho )$

.

The proof of Theorem 2.12 relies on two steps.

-

(i) We first extract the ‘excess states’ out of the difference

$P_1-P_2$

which are responsible for a nonzero index, see Lemma 2.15 below. Because of the obstruction in Remark 2.11, the unitary which implements this unfolding is necessarily not the second quantization of a Hilbert space one, but it can be constructed explicitly. In particular, it is in

$P_1-P_2$

which are responsible for a nonzero index, see Lemma 2.15 below. Because of the obstruction in Remark 2.11, the unitary which implements this unfolding is necessarily not the second quantization of a Hilbert space one, but it can be constructed explicitly. In particular, it is in

$\mathcal {D}(\delta ^\rho )$

since the charge deficiency is finite. Indeed, it is very much in the spirit of Example 2.13.

$\mathcal {D}(\delta ^\rho )$

since the charge deficiency is finite. Indeed, it is very much in the spirit of Example 2.13. -

(ii) As a result, we obtain two projections whose index is zero and whose difference is trace-class. It remains to use the second quantization provided by Lemma 2.16, which does not change the charge deficiency. Since all unitaries are explicit, the equality of indices follows from a computation.

Proof of Theorem 2.12.

Using Lemma 2.15 below, since

![]() $P_1-P_2 \in \mathcal {J}_1(\mathcal {H})$

, we write

$P_1-P_2 \in \mathcal {J}_1(\mathcal {H})$

, we write

with

![]() $\widetilde P=VP_1V^{*}$

and

$\widetilde P=VP_1V^{*}$

and ![]() . By Lemma 2.16 below,

. By Lemma 2.16 below,

![]() $\omega _{\widetilde P}$

and

$\omega _{\widetilde P}$

and

![]() $\omega _{P_1}$

are

$\omega _{P_1}$

are

![]() $\rho $

-locally comparable with

$\rho $

-locally comparable with

![]() $\Gamma (V^{*})\in \mathcal U(\mathcal {A}) \cap \mathcal {D}(\delta ^Q)$

and

$\Gamma (V^{*})\in \mathcal U(\mathcal {A}) \cap \mathcal {D}(\delta ^Q)$

and

since

![]() $\omega _{\widetilde P}(a^{*}(f) a(g)) = \langle g, VP_1V^{*} f\rangle = \omega _{P_1}(a^{*}(V^{*} f) a(V^{*} g))$

. Let

$\omega _{\widetilde P}(a^{*}(f) a(g)) = \langle g, VP_1V^{*} f\rangle = \omega _{P_1}(a^{*}(V^{*} f) a(V^{*} g))$

. Let

![]() $n_\pm =\mathrm {rank}(N_\pm )$

and

$n_\pm =\mathrm {rank}(N_\pm )$

and

![]() $\{f_i\}$

and

$\{f_i\}$

and

![]() $\{g_i\}$

be orthonormal bases of the range of

$\{g_i\}$

be orthonormal bases of the range of

![]() $N_-$

and

$N_-$

and

![]() $N_+$

respectively. We consider

$N_+$

respectively. We consider

$$ \begin{align*}v_+ = \prod_{i=1}^{n_+} (a(g_i)+a^*(g_i)), \qquad v_-=\prod_{i=1}^{n_-} (a(f_i)+a^*(f_i)). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}v_+ = \prod_{i=1}^{n_+} (a(g_i)+a^*(g_i)), \qquad v_-=\prod_{i=1}^{n_-} (a(f_i)+a^*(f_i)). \end{align*} $$

One checks that

![]() $v_\pm \in \mathcal {U}({\mathcal A})$

as products of unitary factors, see again Example 2.13. Moreover,

$v_\pm \in \mathcal {U}({\mathcal A})$

as products of unitary factors, see again Example 2.13. Moreover,

![]() $v_\pm \in \mathcal {D}(\delta ^Q)$

as polynomials in creation and annihilation operators. We claim that

$v_\pm \in \mathcal {D}(\delta ^Q)$

as polynomials in creation and annihilation operators. We claim that

is such that

We prove the first equality in (24), the second one is just (23). Since

we see that for

![]() $v_\xi = a^{*}(\xi ) + a(\xi )$

,

$v_\xi = a^{*}(\xi ) + a(\xi )$

,

where

![]() $P_\xi = \vert \xi \rangle \langle \xi \vert $

. In particular,

$P_\xi = \vert \xi \rangle \langle \xi \vert $

. In particular,

$$ \begin{align*} \begin{cases} \omega_{\widetilde P}\circ \operatorname{Ad}_{v_\xi}(a^{*} (\psi)a(\phi)) = \langle\phi,(\widetilde P - P_\xi )\psi\rangle &\text{if}\quad \widetilde P P_\xi = P_\xi, \\ \omega_{\widetilde P}\circ \operatorname{Ad}_{v_\xi}(a^{*} (\psi)a(\phi)) = \langle\phi,(\widetilde P + P_\xi )\psi\rangle & \text{if}\quad \widetilde P P_\xi = 0. \end{cases} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \begin{cases} \omega_{\widetilde P}\circ \operatorname{Ad}_{v_\xi}(a^{*} (\psi)a(\phi)) = \langle\phi,(\widetilde P - P_\xi )\psi\rangle &\text{if}\quad \widetilde P P_\xi = P_\xi, \\ \omega_{\widetilde P}\circ \operatorname{Ad}_{v_\xi}(a^{*} (\psi)a(\phi)) = \langle\phi,(\widetilde P + P_\xi )\psi\rangle & \text{if}\quad \widetilde P P_\xi = 0. \end{cases} \end{align*} $$

Applying this recursively with

![]() $\xi $

running through the basis of

$\xi $

running through the basis of

![]() $N_+$

and then the basis of

$N_+$

and then the basis of

![]() $N_-$

and recalling that

$N_-$

and recalling that

![]() $\widetilde P N_- = N_-$

and

$\widetilde P N_- = N_-$

and

![]() $\widetilde P N_+ = 0$

yields

$\widetilde P N_+ = 0$

yields

which proves (24). Thus

![]() $\omega _{P_2}$

and

$\omega _{P_2}$

and

![]() $\omega _{P_1}$

are

$\omega _{P_1}$

are

![]() $\rho $

-locally comparable.

$\rho $

-locally comparable.

For completeness let us show the equivalence of the indices using the intrinsic decomposition just exhibited. We compute