LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

recognise the presenting features of ARFID in children and young people, and relate these to current diagnostic criteria

understand associations with other neurodevelopmental and psychiatric conditions

understand the importance of a holistic multidisciplinary approach to assessment and management.

The conceptualisation of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) has evolved over time. The first reference to ARFID in diagnostic classifications came with the publication of DSM-5 in 2013 (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Prior to this, both DSM-4 (American Psychiatric Association 1994) and ICD-10 (World Health Organization 1992) made reference to a ‘feeding disorder of infancy and [early] childhood’.

ICD-11, which came into effect in 2022, defines ARFID as an avoidance or restriction of food that has a negative impact on an individual’s weight or nutritional status or significantly impairs their functioning (World Health Organization 2022). ICD-11 highlights that the avoidant or restrictive eating pattern seen in ARFID can lead to significant weight loss, severe nutritional deficiencies and, in some cases, a dependence on nutritional supplements. Consequently, individuals may experience substantial impairment in family relationships, educational engagement or occupational domains and they may struggle with social interaction, particularly at mealtimes. Importantly, ARFID is not motivated by a desire to achieve a certain body shape or weight, which differentiates ARFID from other eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa. It cannot be better explained by another mental disorder, another health condition (such as food allergies) or the effects of substances or medications. Furthermore, the restrictive food intake demonstrated in ARFID is not a result of food scarcity, cultural practices or food preferences such as veganism (World Health Organization 2022).

It is commonly accepted that there are three main manifestations of ARFID: (a) lack of interest in food, (b) sensory sensitivity to food and/or (c) fear of aversive consequences from eating (American Psychiatric Association 2013).

Individuals with ARFID may present with one or more than one of these manifestations. Those with a lack of interest may describe eating as a chore and/or do not derive any pleasure from it. Individuals with sensory sensitivities tend to restrict their food intake because of the specific sensory properties of the food (such as its texture or taste), with some foods perceived as completely intolerable. Individuals with sensory sensitivities often report differences in interoception or they may be hypersensitive to taste perception (Thomas Reference Thomas, Lawson and Micali2017). Those with a fear of aversive consequences typically have had a previous negative experience with certain foods, such as choking or vomiting after consuming the food; however, their response to the event may be disproportionate or the fear may persist long after the actual event.

Box 1 presents the first of three fictitious cases of young people with ARFID, introducing Casey, who has a lack of interest in food. We will return to these three vignettes when discussing interventions.

BOX 1 Case vignette 1: Casey, a young person with lack of interest in food

Casey is a 12 year-old girl who was referred to the community eating disorder service (CEDS) by the duty and assessment team in her local child and adolescent mental health service (CAMHS). Casey’s parents explained that for several years they have been worried about how little interest in eating she seems to have and how she struggles to gain weight. They had taken her to their general practitioner (GP) and to the accident and emergency department on several occasions, but professionals had been reassured by her normal physical observations. Her GP had referred her to a dietitian and also to CAMHS, querying whether she might have an eating disorder or an anxiety disorder. The CAMHS duty team recognised that her presentation could fit with possible avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) and referred Casey to CEDS.

Casey explained to her ARFID practitioner that eating is a ‘chore’ and she finds it ‘boring’. She did not have any concerns about her body size or image, and emphasised that she was not trying to lose weight. She explained that she just never feels particularly hungry and has to force herself to eat a small meal and snack each day. Her body mass index (BMI) centile was below the 0.4th on assessment.

BOX 2 Key co-occurring neurodevelopmental and psychiatric conditions associated with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)

-

Autism spectrum disorder (autism): 43.9%a

-

Anxiety: 43.9%

-

Intellectual disability: 20.4%

-

Depression: 7.8%

-

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): 7.2%

-

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD): 5.3%

-

Self-harm: 4.7%

a. Prevalence rates obtained from Sanchez-Cerezo et al (Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Neale and Julius2024a).

Epidemiology

A national observational surveillance study of ARFID in the UK and Ireland was conducted between March 2021 and March 2022, in collaboration with the British Paediatric Surveillance Unit (BPSU) and the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Surveillance System (CAPSS) (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Neale and Julius2024a). The annual incidence rate for ARFID was 2.79 per 100 000 young people aged 5–17 years. The average age at diagnosis was 11.2 years. Females formed 45.5% of the sample. It is important to recognise that young people with ARFID managed in primary care, psychology or dietitian-led services would not have been detected by this study, and therefore UK community incidence and prevalence rates are unknown (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Neale and Julius2024a). Additionally, the ability of a clinician to recognise ARFID when a patient presents will influence prevalence estimates. A recent meta-analysis highlighted that ARFID often remains unrecognised by healthcare professionals (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Nagularaj and Gledhill2023). Prevalence estimates for ARFID internationally are variable, owing to the scarcity and heterogeneity of epidemiological studies. A recent meta-analysis (Nicholls-Clow Reference Nicholls-Clow, Simmonds-Buckley and Waller2024) cited a prevalence of 11.14%, but once the model was adjusted for between-study variability in study quality, the prevalence reduced to 4.51%. Therefore, prevalence figures are likely to be skewed by low study quality.

The estimated mean age of individuals with ARFID at presentation to services is between 11.1 and 14.6 years, which is typically younger than individuals diagnosed with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Nagularaj and Gledhill2023). There is a higher proportion of males than females in both paediatric and adult populations (Nicholls-Clow Reference Nicholls-Clow, Simmonds-Buckley and Waller2024). Based on estimated probabilities, the BPSU/CAPSS study calculated that just over one-third (38.2%) of individuals between 5 and 18 years of age tend to experience a combined manifestation, where they lack an interest in food and demonstrate sensory sensitivities (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Neale and Julius2024b). The second most common manifestation is sensory sensitivities alone (29.5%), followed by a lack of interest in food (25.1%). Fear of aversive consequences tends to be the least commonly experienced manifestation (7.2%).

Co-occurring conditions

The aetiology of ARFID remains poorly understood but pre-existing medical, neurodevelopmental and psychiatric conditions are common. There is often a precipitating event such as bereavement, bullying, physical illness or other trauma (Cooney Reference Cooney, Lieberman and Guimond2018). Box 2 highlights the most prevalent neurodevelopmental and mental health conditions associated with ARFID in 5- to 17-year-olds in the recent UK BPSU/CAPSS study (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Neale and Julius2024a).

Box 3 Case vignette 2: Ayub, a young person anxious about the consequences of eating

Ayub is a 15-year-old who was referred to child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) by his general practitioner (GP) for an assessment of his anxiety symptoms. CAMHS referred him on to the community eating disorder service (CEDS). Ayub reported a year-long history of being able to eat only smooth foods, such as yoghurt, tomato soup or melted chocolate. Ayub struggled to fully describe why he does this, but revealed he is worried he will choke if he eats more solid food. His parents could not remember an initial trigger, but report that he has lost significant amounts of weight over the past few months. Prior to his difficulties with eating, Ayub was achieving well at school, although he preferred to spend time on his own and displayed little interest in peer interactions. He often appeared to struggle in class because of environmental noise, and moving between lessons in busy corridors could cause him anxiety and distress. Teachers had raised concerns about this with his mother.

On assessment, Ayub had been losing at least 1 kg/week for the past 3 months. He appeared tired and had poor muscle strength.

Psychiatric comorbidity is often seen in those with ARFID, with anxiety disorders being the most common (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Neale and Julius2024b). Although individuals with ARFID and anxiety disorder can experience any of the ARFID manifestations, they most often experience a fear of aversive consequences and/or sensory sensitivities. The BPSU/CAPSS study found that 84.2% of young people with a fear of aversive consequences and 56% of those with sensory sensitivities also had an anxiety disorder (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Neale and Julius2024b). Box 3 introduces Ayub, a young person with food-related anxiety.

BOX 4 Case vignette 3: Jack, a young person with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), an intellectual disability and sensory sensitivities to food

Jack is a 7-year-old boy who was referred to the community eating disorder service (CEDS) by the community paediatrician at his school. Jack has a moderate disorder of intellectual development and attends a specialist school. Concerns for Jack arose as a result of the repertoire of his dietary intake, which had become increasingly restricted over a period of several years. He would only eat a certain brand of chicken nuggets, ready salted crisps (one brand) and chips. He would only drink Vimto. He expressed extreme levels of distress when encouraged to eat other foods. His family believed that this was because of the sensory quality associated with these foods, because certain textures and smells made him retch.

On assessment by specialist ARFID practitioners, Jack’s weight and height measured within the normal range (75th body mass index centile). However, the team and Jack’s family were concerned about the risk of nutritional deficiencies.

ARFID has a particular association with autism, whether diagnosed or undiagnosed, and intellectual disability (also known as learning disability in UK health services). Individuals with both autism and ARFID can present with any of the ARFID manifestations, but they are more likely to have sensory sensitivities and a lack of interest in food compared with those without a co-occurring autism diagnosis (Watts Reference Watts, Archibald and Hembry2023). This may be because there are shared traits between autism and ARFID, such as differences in interoceptive awareness, sensory sensitivities and restricted, repetitive behaviours. These may converge to limit food intake variety and interest (Watts Reference Watts, Archibald and Hembry2023). Those with co-existing intellectual disability tend to primarily experience sensory sensitivities to food, rather than the other manifestations (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Neale and Julius2024b).

Other psychiatric conditions, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depressive and bipolar-related disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and trauma-related disorders, are also risk factors for ARFID driven by sensory sensitivities (Kambanis Reference Kambanis, Kuhnle and Wons2020; Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Neale and Julius2024b). Individuals who have had a traumatic food-related event (such as choking), OCD or trauma-related disorders are at an increased risk of developing a fear of aversive consequences of eating (Kambanis Reference Kambanis, Kuhnle and Wons2020).

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has been cited as a risk factor for ARFID. A recent cross-sectional study among patients aged 8–25 years with IBD in the USA estimated that 15% met criteria for ARFID, higher than the cited general population prevalence of 2–3% (Koh Reference Koh, Dunn and Tandel2025). Individuals with IBD typically exhibit restrictive eating patterns and use exclusion diets to help manage their bowel condition. A recent study in China conducted with adults concluded that individuals with active Crohn’s disease who also had dietary attitudes towards symptom control or adopted specific diets were significantly more likely to have ARFID (Tu Reference Tu, Li and Yin2025). Other gastrointestinal conditions are likely to co-occur; emerging evidence points to a high prevalence of ARFID among people with coeliac disease (Bennett Reference Bennett, Bery and Esposito2022), and further research in paediatric populations is recommended.

Clinical presentation

Typical presenting features of ARFID include low weight, significant weight loss or a failure to thrive. Weight loss cannot be considered a pathognomonic feature of ARFID, as some individuals eat a restricted repertoire of foods but in sufficient quantities to maintain a normal or higher weight (World Health Organization 2022; Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Neale and Julius2024b). These patients are still at risk of nutritional deficiencies or psychosocial consequences depending on the nature of their restrictive eating habits. Box 4 introduces Jack, a young person with an intellectual disability who is of normal weight and has sensory sensitivities to food.

Other signs and symptoms associated with ARFID, which may either pre-date or result from restricted eating, include acid reflux, constipation, abdominal pain, vomiting, delayed puberty, menstrual irregularities, concentration difficulties and intolerance of cold (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Nagularaj and Gledhill2023).

Where do patients present?

Individuals with ARFID present to a range of services, owing to the heterogeneous nature of the disorder and resulting varied clinical presentations. The vast majority will have initial contact with primary care. From there, depending on local referral pathways, they may be referred to a specialist ARFID service, an eating disorders service, a community or out-patient paediatric service or a paediatric dietitian. Not all services will have comprehensive knowledge of managing ARFID presentations and it can be an exclusion criterion for some services. Specialist feeding clinics have the highest prevalence rate of young people with ARFID compared with other health services, with 32–64% of young people presenting to these services meeting criteria for the disorder (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Nagularaj and Gledhill2023). Many physical symptoms, such as abdominal pain and constipation, pre-date the eating disturbances seen in ARFID, and it is estimated that almost 50% of young individuals with ARFID have had interactions with gastroenterology and endocrinology clinicians prior to presenting to more specialist services (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Nagularaj and Gledhill2023). Those with ARFID can also present to emergency services if acute complications arise as a result of malnutrition.

In areas that lack a specialised ARFID service, there can be challenges for primary care professionals and dietitians in knowing which service to refer to. It can be difficult to determine whether mental health services or paediatrics should take the lead in coordinating care, depending on the nature of the ARFID presentation and co-occurring conditions. Challenges of working across teams may include conflicting views on treatment options and inflexibility of treatment pathways.

Assessment

Bryant-Waugh et al (Reference Bryant-Waugh, Loomes and Munave2020) have proposed an evidence-based out-patient care pathway for young people with ARFID. They recommend that as a minimum, the multidisciplinary team should include medical and mental health professionals, ideally alongside dietitian input. Other professionals may be involved as required, for example speech and language therapists to assess swallow function or occupational therapists to assess sensory processing. Education staff are key to a multi-agency approach, as schools may need to support a young person at mealtimes and need to have an understanding of their presentation.

There are currently no national guidelines advising on the assessment and management of ARFID in the UK. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline on the recognition, assessment and management of eating disorders explicitly excludes ARFID (NICE 2017, updated in 2020). The following recommendations are derived from the research evidence base and our clinical practice.

History

A thorough patient history is crucial in the assessment of an individual with potential ARFID, to discriminate the diagnosis from other eating disorders and causes of restricted eating and to develop an appropriate management plan (Brigham Reference Brigham, Manzo and Eddy2018). By adopting a biopsychosocial model, professionals can formulate the predisposing, precipitating, perpetuating and protective factors for the young person and their family. Assessing professionals should specifically enquire about the main manifestations of ARFID (whether there is low interest in food, worries about adverse consequence from eating, or sensory sensitivities). They should determine the onset and progression of symptoms, possible precipitating factors, maintaining factors and the impact of ARFID for the young person and their family. It is important to understand typical dietary intake over a period of time, alongside associated eating behaviours such as avoiding mealtimes or secreting food. It is essential to determine the individual’s perspective of their weight and body shape, given that individuals with ARFID are not motivated to restrict their eating by a desire to alter their weight or body shape. Clinicians should screen for purging behaviours to help differentiate ARFID from other eating disorders. Through history taking, clinicians can gauge the motivation of the young person and their family to make changes.

A full medical history should be taken, with an emphasis on screening for co-occurring physical, neurodevelopmental and psychiatric conditions and undertaking a medical risk assessment. Weight change over time should be explored. Symptoms associated with malnutrition should be specifically probed, such as fatigue, dizziness or palpitations. In biologically female patients, it is essential to enquire if and when they reached menarche and to determine their current menstrual cycle pattern; menstrual cycles can become irregular or disappear in individuals with ARFID and this often indicates significant nutritional deficits (Brigham Reference Brigham, Manzo and Eddy2018).

Dinkler & Bryant-Waugh (Reference Dinkler and Bryant-Waugh2021) summarise the screening questionnaires, questionnaires for clinical populations and diagnostic interviews available for the assessment of ARFID. Screening measures include the Nine Item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Screen (Nine-Item ARFID Screen, NIAS), which can be parent- or self-reported, and the ARFID – Brief Screener (ARFID-BS), which is a parent-reported questionnaire for children aged 2–17 years. The Pica, ARFID, and Rumination Disorder Interview – ARFID Questionnaire (PARDI-AR-Q) focuses on ARFID symptoms, and is also parent- or self-reported, depending on the age of the child. It is based on the longer PARDI. Additional validation studies are required to determine the clinical utility of these measures (Dinkler Reference Dinkler and Bryant-Waugh2021), and there is currently a lack of consensus as to which should be routinely used in clinical practice. Diagnostic tools can allow for a standardisation of assessment, but they may not fully allow for a psychosocial formulation, and individuals falling just below the diagnostic threshold may still require interventions to address functional impairment.

Examination

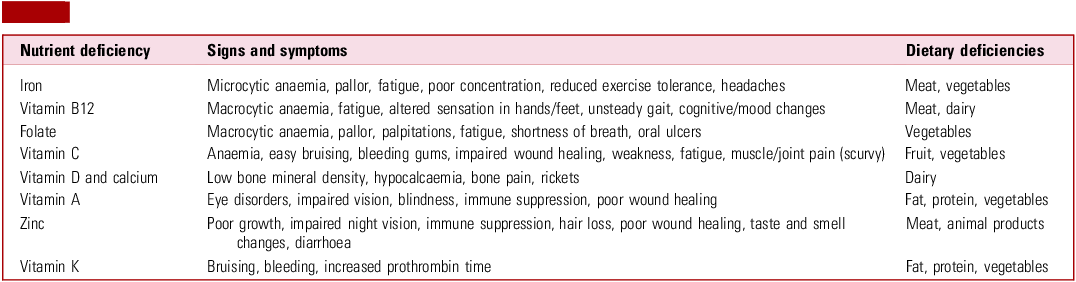

Height and weight should be measured, with the child’s body mass index (BMI) centile calculated. This calculation compares the young person’s BMI with that of other young people of the same age and gender. It should be plotted over time on a growth chart to determine trends to help guide management. Clinicians should assess for signs of significant global malnutrition such as cachexia, bradycardia and hypothermia (Brigham Reference Brigham, Manzo and Eddy2018). Muscle wasting and reduced muscle strength may be identified. Signs of specific nutrient deficiencies may be evident; although there remains a lack of consensus on which nutritional deficiencies should be screened for in ARFID, possible deficiencies are summarised in Table 1.

TABLE 1 Nutrient deficiencies associated with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)

Source: adapted from Brigham et al (Reference Brigham, Manzo and Eddy2018) and Yule et al (Reference Yule, Wanik and Holm2021).

Investigations

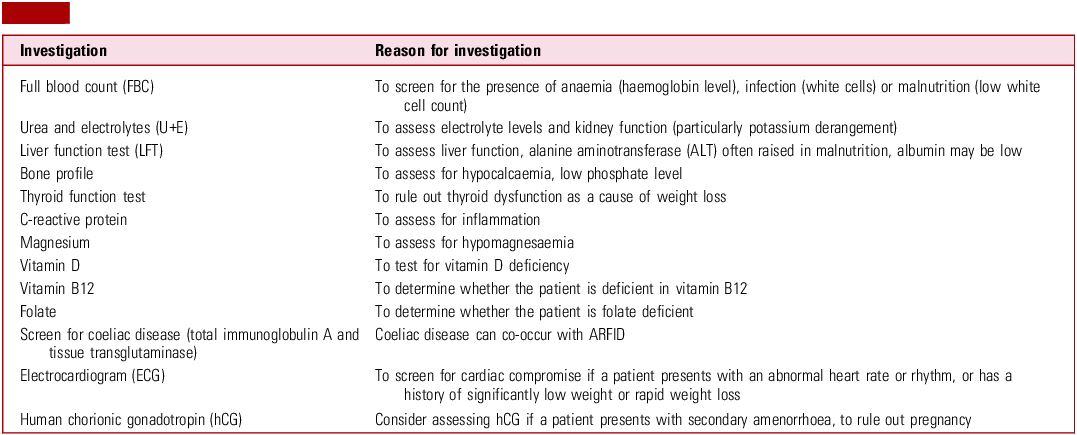

Restricted eating can result in significant physical compromise. Electrolyte abnormalities such as hypokalaemia, hypophosphataemia and hypocalcaemia risk cardiac and renal compromise. Endocrine abnormalities may emerge, such as delayed puberty and, in biological females, secondary amenorrhoea (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Nagularaj and Gledhill2023; James Reference James, O’Shea and Micali2024). Specific cardiac complications include bradycardia and QT interval prolongation, which can increase the risk of further arrhythmias and sudden death (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Nagularaj and Gledhill2023). Insufficient nutritional intake can cause low bone mineral density or osteoporosis (calcium and vitamin D deficiency) (James Reference James, O’Shea and Micali2024). This may be exacerbated by delayed or interrupted puberty. As with patients with anorexia nervosa, those with ARFID and a disruption of their menstrual cycle should be referred to a paediatric endocrinologist for an assessment of bone health (NICE 2017). There are few published studies on the specific magnitude of effect of ARFID on growth and puberty (James Reference James, O’Shea and Micali2024) and this warrants further research. However, the impact is likely to be associated with how long the young person has been underweight, the effect on their growth and pubertal development, and specific nutritional deficiencies.

Table 2 illustrates recommended investigations to consider in a young person with ARFID at presentation (and subsequently as needed).

Table 2 Investigations for a young person presenting with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)

Risk assessment

ARFID can present as an acute medical emergency. In 2022, the Royal College of Psychiatrists published guidelines on medical emergencies in eating disorders (MEED) (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2022, updated in 2023). These superseded the previous Junior MARSIPAN guidelines (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2012). The MEED guidelines apply to ARFID, alongside other eating disorders. They recommend an urgent risk assessment at presentation to determine whether there is an immediate risk to life. A risk assessment involves taking a detailed medical and psychiatric history, alongside examining parameters such as weight, cardiovascular and renal function and hydration status. Physical observations (e.g. blood pressure, heart rate) and blood tests (Table 2) should be performed, with additional tests being ordered based on clinical judgement. The MEED guidelines present a ‘traffic light’ system of concerning features on assessment, such as red flags (‘lightbulb’ signs) that signal high impending risk to life in paediatric patients (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2022).

Clinicians should not necessarily be reassured by normal blood test results, as even patients with advanced malnutrition can present with test results in the normal range. It is therefore essential that a specialist dietitian evaluates the individual’s diet to look for nutritional problems that would not be identified via blood tests alone.

An assessment of mental health is also needed, to determine the risk of self-harm, suicidal ideation, vulnerability to external influence and self-neglect.

Psychosocial impact of ARFID

Young people and their families describe the impact of ARFID on their social and educational progress. Although it is generally accepted that malnutrition affects attention and concentration, there is a gap in the research literature on the effect of ARFID on educational attainment, attendance and engagement. It is suspected that associated conditions, such as autism and intellectual disability, may cumulatively exacerbate the educational impact of ARFID. Eating practices such as group mealtimes and limited choice of foods may increase anxiety and lead to anxiety-based school avoidance; however, data are limited and this is an important area for future research. Social interactions more generally may be affected, owing to either reduced motivation and energy to engage in social activities, or high levels of distress regarding exposure to food (Harshman Reference Harshman, Wons and Rogers2019). Some individuals experience shame about their restrictive food choices, which can lead to them eating in isolation rather than in social settings (Harshman Reference Harshman, Wons and Rogers2019). Many carers and family members also experience mealtimes as challenging, as the individual with ARFID can become irritable and combative about what or how much food they will eat (World Health Organization 2022).

Interventions

A collaborative approach involving patients and their families is key to intervention and management. Clinicians should seek to understand the concerns, expectations and health beliefs that families bring and what their priorities about treatment goals may be. Dietary goal setting should be graded, realistic, regularly reviewed and co-designed with families.

There is often an initial period of weight restoration and nutritional optimisation. Weight restoration involves returning a patient to their target weight and expected BMI centile based on age- and height-appropriate norms. If the individual is deemed to be at high risk of physical compromise through malnutrition or refeeding, they may require in-patient treatment for weight restoration. Nutritional supplements may be required, but are not always tolerated. Enteral feeding and legal frameworks to support this may need to be considered if the young person refuses or cannot tolerate oral refeeding. However, this can be problematic as it may be difficult for a young person with existing aversions to food to return to an oral diet once enteral feeding has been introduced. Careful thought and multidisciplinary planning regarding the most appropriate feeding methods may be required, including close collaboration with caregivers (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2022).

Weight and growth maintenance longer term involves collaboration between the young person, their family and healthcare professionals to modify unhelpful attitudes to food and promote healthier eating habits. During these interactions, professionals should aim to increase the volume of preferred foods to promote weight gain, before they attempt to increase the food variety (Brigham Reference Brigham, Manzo and Eddy2018). By restoring an individual’s weight, this may initiate puberty or restore menstruation (Downey Reference Downey, Richards and Tanner2023).

In the sections that follow, we use the cases introduced in Boxes 1–3 to illustrate the role psychoeducation can play in supporting recovery from ARFID. This is often undertaken with the caregivers and network around the young person and, depending on their age and level of understanding, may also include the young person.

Biological and pharmacological interventions

There are currently no pharmacological agents specifically designed to treat ARFID; however, there are medications that could improve specific aspects of an ARFID presentation or co-occurring conditions. Improving these conditions may enable an individual with ARFID to engage more effectively with behavioural interventions. It is important to recognise that psychotropic medications that are sometimes used for ARFID are prescribed off-label, as none have yet been approved by regulatory bodies. Moreover, there is a very limited evidence base for their efficacy and idiosyncratic responses have been noted. Medication in this context should therefore be prescribed only in secondary care and with caution, and appropriate information should be provided to parents, carers and the young people for the purposes of informed consent.

Many individuals with ARFID, particularly those with a fear of aversive consequences, also have an anxiety disorder or significant symptoms. Medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can be prescribed to address either generalised or food-specific anxiety, and there is growing evidence for their effectiveness (Mahr Reference Mahr, Billman and Essayli2022).

A systematic review provides cautious emerging evidence for the use of the anti-histamine cyproheptadine to stimulate appetite and promote weight gain; this review included five randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving adults with anorexia nervosa (Harrison Reference Harrison, Norris and Robinson2019). However, there have been few efficacy studies in ARFID populations. Cyproheptadine can cause sedation, alongside tachyphylaxis, and therefore regular medication breaks should be considered if the efficacy of the medication decreases over time (Brigham Reference Brigham, Manzo and Eddy2018). Box 5 illustrates the use of cyproheptadine alongside a holistic package of care for Casey, whom we met in Box 1.

BOX 5 Case vignette 1: Casey – interventions

Casey and her family accepted the offer of intervention from the avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) service. Following assessment by a dietitian, she chose to receive therapeutic work from an ARFID specialist practitioner. Casey’s blood tests showed a mild anaemia and raised liver enzymes, with normal electrolytes. Her electrocardiogram (ECG) was unremarkable.

Direct psychoeducation was undertaken with Casey, focused on helping her not to rely on her bodily sensations to gauge her need for nutrition, and to adopt a mechanical eating programme (eating by the clock). Motivational interviewing techniques were employed to assess her motivation for change. Parallel work was undertaken with parents, including enrolling them in the ARFID parent psychoeducation group.

Casey was trialled on cyproheptadine as an appetite stimulant. Initially, she struggled with side-effects, particularly fatigue, and wanted to stop the medication; however, with encouragement from her parents and practitioners, she managed to continue. Gradually, Casey began to eat regular meals. Her weight improved over a period of months, and she reported being able to concentrate in school better and have more energy for gymnastics.

Olanzapine, an atypical antipsychotic, has been used off-label for young people with ARFID to reduce cognitive rigidity about food beliefs and to encourage weight gain (Brigham Reference Brigham, Manzo and Eddy2018). However, it has an extensive side-effect profile, and clinicians should use the smallest effective dose possible to limit the side-effects (Brewerton Reference Brewerton and D’Agostino2017).

There are currently no medications proven beneficial for patients with sensory sensitivity to food (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Neale and Julius2024b).

Individuals with ARFID should be prescribed electrolyte and vitamin supplements as required to counteract deficiencies that have developed (Brigham Reference Brigham, Manzo and Eddy2018).

ADHD can co-occur with ARFID. The inattention and motor hyperactivity associated with ADHD can affect interest in eating and arousal levels during meals (Fonseca Reference Fonseca, Curtarelli and Bertoletti2024). Medical treatment options for ADHD should be targeted to the individual, noting differential impacts on appetite.

Psychological interventions

Willmott and colleagues’ scoping review (Reference Willmott, Dickinson and Hall2024) reports on an array of psychological interventions for ARFID, including behavioural interventions, cognitive–behavioural therapy, family therapy and a combination of approaches. They do, however, highlight that most studies have small sample sizes and heterogeneous outcome measures are used, making it challenging to draw direct comparisons. Food exposure, family involvement, psychoeducation and management of anxiety are common themes across many interventions.

Individual approaches

Some behavioural techniques can be applied to all individuals with ARFID, regardless of the specific manifestation, to improve their food intake and range. ‘Food chaining’ is a technique that involves identifying a food that a patient likes and gradually introducing new but similar foods over time (Białek-Dratwa Reference Białek-Dratwa, Szymańska and Grajek2022). Another technique is a ‘sequential oral sensory approach’, where a therapist is involved to help children and adolescents try new foods (Mohamed Reference Mohamed and Mahfouz2025). The methods the therapists use in this approach are determined by the patient’s age and developmental status.

If a patient presents with a lack of interest in food, techniques such as structured mealtime routines and behavioural rewards when food is eaten at the table while gradually increasing portion sizes can be trialled. Engaging the young person in food-related activities such as shopping or cooking can also be integrated into the management plan (Archibald Reference Archibald and Bryant-Waugh2023).

Cognitive–behavioural therapy for ARFID (CBT-AR) is a form of CBT adapted for people with ARFID. It typically involves 20–30 sessions and is currently recommended for patients 10 years or older who are clinically stable and not dependent on enteral feeding (Thomas Reference Thomas, Becker and Kuhnle2020). Following psychoeducation, maintaining mechanisms are addressed, which may include exposure to foods during sessions (e.g. trying new foods or working through a fear and avoidance hierarchy) and between-session practice. This is followed by relapse prevention (Thomas Reference Thomas, Becker and Kuhnle2020). In a feasibility study utilising CBT-AR in children and adolescents with ARFID, 70% of participants no longer met the criteria for ARFID post-treatment (Thomas Reference Thomas, Becker and Kuhnle2020). Further large-scale studies are required to determine the longer-term efficacy of CBT-AR and the relapse rate. Traditional CBT can also be used for treatment of co-occurring conditions such as depression and anxiety (Archibald Reference Archibald and Bryant-Waugh2023), and may need to be adapted for young people who are neurodivergent. It should be noted that with neurodivergent patients, the offer of individual or family-based psychological interventions targeting anxiety or affective difficulties should be based on the age and functioning of the young person. Box 6 illustrates how CBT was offered to Ayub, whom we met in Box 3.

BOX 6 Case vignette 2: Ayub – interventions

For Ayub, the initial focus was on providing nutrition via local refeeding protocols. He was given liquid nutritional supplements. His blood tests revealed a low white cell count, and his bloods and electrocardiograms (ECGs) were monitored during the refeeding process.

Ayub began to gain weight with nutritional supplements, and the team felt he and his parents were now in a position to be offered psychoeducation. Individual cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) was undertaken with Ayub; however, as the sessions progressed, it became clearer to the practitioner and Ayub that he struggled to fully access his own cognitions. Therefore an adapted approach was offered with a focus on behaviours (graded exposure alongside intensive psychoeducation).

Once Ayub’s weight was fully restored, the team raised with the family whether they felt he would benefit from a formal assessment of his social communication; Ayub and his parents gave consent for this.

Family-based approaches

Family-based approaches have also been demonstrated to have a positive effect on clinical outcomes of young people with ARFID (Archibald Reference Archibald and Bryant-Waugh2023). These can include educating parents about ARFID: teaching them specific skills to help them provide structure and routine at mealtimes, make changes to the home environment to encourage eating, and manage the young person’s anxiety (Białek-Dratwa Reference Białek-Dratwa, Szymańska and Grajek2022). By investigating family dynamics during family therapy sessions, health professionals can identify behaviours of the family members or carers that may be inadvertently promoting restrictive eating behaviours and work with them to adapt the home environment to encourage improved eating habits. Lock et al’s (Reference Lock, Sadeh-Sharvit and L’Insalata2019) RCT comparing family-based treatment for ARFID with usual care suggests that such RCTs are feasible, and large scale trials are now needed to demonstrate efficacy. Additionally, caring for patients with ARFID can be emotionally and physically draining, so it imperative that clinicians signpost carers to mental health and practical support.

Box 7 illustrates the use of family-centred psychoeducation while also drawing on multi-agency expertise to support Jack (introduced in Box 4) in school.

BOX 7 Case vignette 3: Jack – interventions

The focus of the team was providing psychoeducation and support for Jack’s parents and the teams around Jack, rather than direct therapeutic work with Jack himself. The specialist dietitian led the intervention, with an emphasis on nutritional safety and reducing the risks of malnutrition. The sensory experience of eating for Jack was discussed, including how he may be more sensitive to taste and prefer blander foods. Jack’s parents, school nurse, community paediatrician, intellectual disability nurse, social worker from the Children with Disabilities Team and education professionals were invited to multi-agency meetings to consider how best to support Jack with his nutritional intake, taking advantage of the sensory play facilities within school to reduce his anxiety about eating. Vitamin supplementation was also advised.

Over time, Jack was gradually supported to increase the repertoire of his oral intake; although this remained less varied than that of other children his age, his parents and professionals working with him were more knowledgeable and confident in understanding his dietary intake and the optimal environmental circumstances to reduce his anxiety about eating.

Barriers to identification and treatment

ARFID has a variety of presentations and clinical consequences. As a result, it can be challenging to diagnose and subsequently treat. A systematic review demonstrated that although recognition of ARFID by health professionals has increased over the past few years, many clinicians still lack confidence in diagnosing and treating these patients (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Nagularaj and Gledhill2023).

A further barrier to treatment is the fear carers have of being judged unfavourably by medical professionals (Nicholls Reference Nicholls and Barrett2015). Therefore, it is crucial for the multidisciplinary team to create an environment in which carers can have open and honest conversations with professionals.

Ongoing commissioning priorities will determine which services and interventions can be offered to families affected by ARFID. Moreover, funding is needed to conduct high-quality trials examining interventions for the disorder. There remain gaps in the evidence-base, which affect assessment and intervention: Box 8 summarises potential areas for future research and policy.

BOX 8 Potential areas for future research and policy in the field of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)

-

Epidemiology of ARFID globally

-

Community incidence and prevalence of ARFID in the UK

-

Aetiology of ARFID, including gene–environment interplay

-

Consensus guidelines on nutritional deficiency screening in ARFID

-

Consensus guidelines on the assessment and management of ARFID

-

Validation of screening and diagnostic tools for ARFID

-

Impact of ARFID on growth and puberty

-

Impact of ARFID on educational progress

-

Pharmacological strategies for ARFID

-

Psychological interventions for ARFID – large pragmatic clinical trials that are representative of the young people seen in clinic

-

Guidance on transition of children with ARFID to adult services

-

Transition of ARFID to other eating disorders

-

Longer-term outcomes of ARFID

-

Incidence, prevalence, presentation, assessment and management of ARFID in adults

Prognosis

Without intervention, the prognosis of individuals with ARFID is generally poor. Patients tend to remain selective in their food choices, resulting in persistent medical complications, such as significantly low weight and nutrient and electrolyte deficiencies (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Nagularaj and Gledhill2023). Cognitions regarding food are often held strongly, which means that treatment and clinical improvement may take some time. Few studies have investigated long-term outcomes in people with ARFID, and this is partly due to its relatively recent inclusion in diagnostic classifications (Seetharaman Reference Seetharaman and Fields2020). Encouragingly, in the first study of CBT-AR with older adolescents, the majority who successfully completed the trial remained in remission in the shorter term (Thomas Reference Thomas, Becker and Kuhnle2020). In the BPSU/CAPSS UK surveillance study, 54.8% of individuals with ARFID improved according to clinicians’ clinical impression (Sanchez-Cerezo Reference Sanchez-Cerezo, Neale and Julius2024a).

The research investigating the transition from ARFID to other eating disorders is limited. However, one recent study determined that 3% of the 100 young people included in the sample transitioned from ARFID to anorexia nervosa over a 2-year follow-up period (Kambanis Reference Kambanis, Tabri and McPherson2025). Those who transitioned were underweight throughout the duration of the study and had a lack of interest in food. Another study interviewed 35 adults who had developed a further eating disorder after being diagnosed with ARFID. Of these, 71% developed a restrictive eating disorder and the remaining 29% developed binge-spectrum eating disorders (Kambanis Reference Kambanis, Mancuso and Becker2024). The researchers noted that cognitive symptoms such as concern with body shape and image preceded the development of behavioural symptoms such as binge eating and excessive fasting and may offer a window for intervention before the subsequent eating disorder becomes more entrenched.

Transition to adult eating disorder services

ARFID can take a chronic course, and indeed some individuals continue to be affected into adulthood (Fonseca Reference Fonseca, Curtarelli and Bertoletti2024). In the UK, patients aged 16–17 years can be managed in either paediatric or adult eating disorder services; however, there is a lack of consistency across these services, which can be challenging for families and care providers (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2022). To facilitate a smooth transition from paediatric to adult health services for people with ARFID, communication between teams and a robust handover should occur. The MEED guidelines include a handover template (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2022). However, in reality, few adult eating disorder services are commissioned to accept ARFID presentations. If they are, acceptance criteria may be strict. The majority of young people are therefore likely to be managed in primary care after they turn 18, with involvement of other healthcare professionals as required. ARFID can newly occur in adults, but there are limited data regarding incidence and prevalence in adult populations.

Conclusion

ARFID is a heterogeneous condition with multiple sequelae, and it often co-occurs in those with neurodevelopmental and anxiety disorders. If left untreated, ARFID can have a significant impact on a young person’s physical health and development, alongside their psychosocial and educational functioning. The incidence and prevalence of ARFID globally is uncertain, and its true community prevalence in the UK is unknown.

Although including ARFID in diagnostic classifications and the MEED guidelines (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2022) is a promising step forward, there is a need for national evidence-based guidelines for the assessment and management of ARFID, and the commissioning support to develop and deliver specialist services. For guideline development, more high-quality, large-scale, pragmatic clinical trials are required to determine appropriate diagnostic tools for ARFID and to research the specific impact that ARFID may have on growth, puberty and education.

There are emerging pharmacological and psychological interventions used for young people with ARFID, but further research is required to determine their short- and long-term efficacy, acceptability and cost-effectiveness. Moreover, there is a lack of services available following transition to adulthood. Many studies researching ARFID focus solely on paediatric populations, resulting in a paucity of research in the adult population. Overall, a holistic multidisciplinary approach to assessment and management is key in order to optimise outcomes for this group of young people.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Which of the following is not part of the ICD-11 diagnostic criteria for ARFID?

-

a Avoidance or restriction of food intake

-

b The intake of an insufficient quantity or variety of food

-

c Significant impairment in functioning

-

d Preoccupation with body weight or shape

-

e The restrictive food intake is not a consequence of food unavailability.

-

-

2 Which of the following is true in relation to the epidemiology of ARFID?

-

a ARFID commonly presents at around the same age as other eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa

-

b ARFID is more common in boys than in girls

-

c ARFID occurs only in individuals with autism or an intellectual disability

-

d The annual incidence in the UK is <1 per 100 000 children aged 5–17

-

e Clear global incidence and prevalence rates are available for ARFID.

-

-

3 Which of the following is the most common manifestation of ARFID?

-

a Lack of interest in food

-

b Sensory sensitivity

-

c Fear of aversive consequences

-

d Combination of lack of interest in food and sensory sensitivity

-

e Combination of sensory sensitivity and fear of aversive consequences.

-

-

4 Which co-occurring condition is not commonly seen in children with ARFID?

-

a Autism

-

b Intellectual disability

-

c Anxiety disorder

-

d Psychosis

-

e Gastrointestinal condition.

-

-

5 Which of the following does not form part of a possible management plan of an individual with ARFID?

-

a Recommending a highly calorific diet, in an effort to increase the person’s weight

-

b Providing the person’s carers with adequate mental health and practical support where required

-

c Prescribing cyproheptadine to stimulate appetite in individuals who present with a lack of interest in food

-

d Implementing techniques such as food chaining and a sequential oral sensory approach to gradually increase the volume and variety of foods the individual will eat

-

e Offering CBT to individuals who have comorbid neurodevelopmental or psychiatric disorders.

-

MCQ answers

-

1 d

-

2 b

-

3 d

-

4 d

-

5 a

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

S.G. contributed to the conceptualisation of the article and led on the drafting of the manuscript. H.S. contributed to the conceptualisation of the article and drafting of the manuscript, along with critical review and revision. A.M. contributed to the conceptualisation of the article and drafting of the manuscript, along with critical review and revision. E.B., A.N., N.S., D.O. and R.E. contributed to the conceptualisation of the article and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the version for submission and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

H.S. is funded by The Christie Charity for a Clinical Research Training Fellowship. A.M. is funded by the Beighton Fellowship. The funders had no role in the design or dissemination of this research.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.