1. Introduction

This article compares relative clauses and their translation equivalents in a parallel corpus of German and English. The primary focus is on postnominal relatives with finite verbs such as der Junge, der den Koffer trug/the boy who carried the suitcase and der Koffer, den der Junge trug/the suitcase which the boy was carrying. A total of 700 examples were collected from written texts in a parallel corpus in which at least one of the languages employed a finite postnominal, or post-pronominal, relative clause. There were 350 translations from German to English, and 350 from English to German. The first goal of the study was to quantify the cases where the two languages employed the same finite relative clause structure versus cases where they diverged from one another using translations that were broadly semantically or pragmatically equivalent. Of particular interest were translations that involved alternative noun–modifier constructions. In the first example above the grammars of both languages permit a simple PP modifier following the noun in place of the finite relative, der Junge mit dem Koffer/the boy with the suitcase. English also allows a postnominal VP modifier with -ing attached to the verb, the boy carrying the suitcase, and it has productive relative pronoun deletion when relativizing on a non-subject, the suitcase the boy was carrying. This deletion is without parallel in German grammar, while German has the famous prenominal relative clause, or extended attribute, construction documented at length in Weber (Reference Weber1971), der von dem Jungen getragene Koffer, literally, ‘the by the boy carried suitcase’. This gloss is ungrammatical in English.

For the 700 examples in the corpus both languages could, in principle, have used the same postnominal finite relative clause (with or without the explicit relative pronoun in English). Yet, in a full 35 percent of cases (244 of the 700) it was found that they used different structural options and the translators did not preserve the precise structure of the source. Either one language employed a more reduced nominal modifier, like the postnominal PP or the VP-ing of English or the prenominal relative of German. Or else one of the languages employed a completely different paraphrase for the content of the finite relative clause using a semantically explicit main clause or alternative subordinate clause.

The reason for insisting that at least one of the languages should employ a full finite relative clause in our data collection, and not also including cases in which both languages employed a reduced form, is that the reduced modifiers can engage in different semantic relations with a preceding N or NP and do not always function as semantic equivalents of relative clauses. For example, I object to the boy carrying the suitcase in English could be a translation for ‘I object to the fact that the boy carried the suitcase’, with an NP-complement structure containing a non-finite subject-predicate clause, which is truth-conditionally distinct from a relative clause modifying the boy (in the former case I am objecting to the fact in question, in the latter I am objecting to this particular boy). Similarly, the PP in the fact of the matter does not correspond semantically to a relative clause whereas the fact under discussion can correspond to the fact we were discussing, which contains a relative clause. Our data selection accordingly required there to be a full and explicit finite relative clause in at least one of the languages, in order to control for this semantic variability.

In general, when reductions were made in the nominal modifiers, these were more characteristic of English than of German, especially in the English to German translations. So a second goal was to try and explain the directionality of these contrasts in language usage, as seen in the parallel corpus, and to further develop a hypothesis that has been proposed for German versus English generally, on the basis of their contrasting grammars.

Hawkins (Reference Hawkins1986) proposed that where German and English grammars contrast, it is generally German that is semantically more explicit and more transparent preserving more features of a corresponding semantic representation. In his terminology, German gives us a “tighter fit” between surface forms (morphemes, words, phrases, clauses) and their corresponding meanings, while English gives us a “looser fit.” Linguists may differ over what they consider a semantic representation to look like, but they are all agreed on the following: When a surface form has more than one truth-conditionally distinct meaning, semantic representations cannot be ambiguous and must have a separate representation for each meaning; material that is semantically understood, even though deleted or absent from surface structure, must be present in semantic representation; and noun phrase arguments must stand “together with” the predicates and subcategorizers with which they are associated semantically. It is these essentials that Hawkins’ comparative typology focuses on.

For example, the grammatical morphology of Modern English is now much reduced and its remaining morphemes exhibit greater ambiguity or vagueness with respect to all the semantic distinctions that were captured in the morphology of Old English, many of which are still captured in Modern German (cf. Sapir Reference Sapir1921, Hawkins Reference Hawkins1986: ch. 2). In the lexicon English verbs have systematically broader subcategorization possibilities than they once did (e.g. more transitive/intransitive ambiguities, again more than in German; see Berg Reference Berg2014). In the grammar there is much greater semantic diversity in the English thematic roles assigned to subjects and objects (German has no direct counterparts for NP-V-NP structures like This tent sleeps four and My guitar broke a string; see Rohdenburg Reference Rohdenburg1974 and again Berg Reference Berg2014). Regular structural ambiguities exist between Raising and Control in English (I believed John to be generous and I persuaded John to be generous have the same surface structure in English for which there is no corresponding surface ambiguity in German; see Hawkins Reference Hawkins1986: ch. 5 and König & Gast Reference König and Gast2018). And there is more pragmatic and information structure ambiguity in English basic SVO word order compared with the corresponding Topic-V2 … and SVO structures of German and older English (see Los & Dreschler Reference Los, Dreschler, Nevalainen and Closs Traugott2012). In all these cases a more reduced and smaller set of surface forms in Modern English can be mapped onto a greater range of meanings. In addition, the looser fit of English results in more separations of arguments from their predicates and subcategorizers, i.e. in more raisings compared with German of subjects and objects into higher clauses where they do not belong semantically and in more WH-extractions (Hawkins Reference Hawkins1986: chs. 5 and 6). There is also less Pied Piping in English, and also generally more permitted deletion of NPs (Hawkins Reference Hawkins1986: ch. 7).

The looser fit of English form–meaning mappings compared with German is accordingly realized on the one hand in the greater ambiguity and vagueness of a more minimal set of commonly used surface forms; and on the other hand we see a greater destruction of semantic clause structure in surface structure, through deletions and separations of items that are of necessity present and positioned together in semantic representations.

Since the tight fit/loose fit distinction was first proposed for English and German contrasts in Hawkins (Reference Hawkins1986) it has been shown to have wider applicability. Müller-Gotama (Reference Müller-Gotama1994) surveyed a dozen diverse languages and demonstrated that the predicted clustering of typological variants was well supported outside of Germanic. Levshina & Hawkins (Reference Levshina and Hawkins2022) also found extensive support for many of the predicted patterns of variation in electronic corpora from twenty-eight diverse languages. Horie (Reference Horie2002) used Hawkins (Reference Hawkins1986) as a basis for describing certain divergences in Japanese away from the extremely tight-fit Korean. Meanwhile within Germanic, Van der Auwera & Noël (Reference Van der Auwera and Noël2011) showed its usefulness in accounting for the intermediate nature of Dutch between English and German with respect to several of the typological variants, as did Shannon (Reference Shannon and Bruijn Lacy1990), while De Vogelaar (Reference De Vogelaar2007) proposed an extension of the typology assigning a greater role to verb agreement in addition to case marking and fixed word order, and he considered other intermediate Germanic dialects and languages as well.

At the same time a number of specialists in English and German have pointed to some counterexamples in the overall directionality of contrast, whereby English has a tighter fit between form and meaning and more semantic transparency in its surface structure (see e.g. Shannon Reference Shannon1988, Rohdenburg Reference Rohdenburg and Gnutzmann1990, Kortmann & Meyer Reference Kortmann, Georg Meyer, Mair and Markus1992, Fischer Reference Fischer2013, König & Gast Reference König and Gast2018). For example, English auxiliary verbs provide explicit expression for future tense (Mary will travel to London) and for ongoing actions (Mary is travelling to London) which are regularly left unexpressed and vague in German (Mary fährt nach London). English often uses a more semantically specific verb + ing in noun modifier constructions where German has a general preposition (compare passengers holding a rail card with Reisende mit BahnCard). And whereas Plank (Reference Plank1984) and others have argued that English verbs generally have broader and vaguer selectional restrictions (German brechen applies only to brittle objects, English break to non-brittle ones as well, like tendons; German regularly distinguishes affected from effected verbs, e.g. English paint translates both affected streichen and effected malen) Fischer (Reference Fischer2013) and König & Gast (Reference König and Gast2018) point to numerous lexical contrasts that go in the opposite direction (German unterschlagen is necessarily differentiated in English by embezzle for money and suppress for information whereas this German verb does service for both).

In response to these counterexamples Hawkins (Reference Hawkins2019) proposed a reformulation of the basic tight-fit/loose-fit typology in more psycholinguistic terms, specifically in terms of what he called “word-external property assignments.” What characterizes all the supporting grammatical contrasts in Hawkins (Reference Hawkins1986) as well as many or most of the proposed counterexamples is that they involve a greater exploitation in English of neighboring words for the assignment of properties in online processing to individual words. So future auxiliary will receives its disambiguation and future meaning by looking to its immediate right and finding the verb travel, which enables the parser to select the auxiliary category and associated meaning, as opposed to the lexical verb and noun categories that also occur within its lexical entry. It is crucially the adjacency and combination of is with verb+ing which permits assignment of present continuous aspect to is traveling. And for a verb like break the following noun (leg or tendon) will disambiguate between the type of breaking that is regularly differentiated word-internally in German by brechen versus zerreissen. The basic point in Hawkins (Reference Hawkins2019) is that the historical “drift” of English (cf. Sapir Reference Sapir1921) appears to have been systematically towards more word-external processing with the assignment of properties through neighborhood effects like this and can be most adequately described in these psycholinguistic, rather than purely grammatical terms. Quite generally languages with a looser fit between forms and meanings involve more word-external processing than languages (like Old English and Modern German) with a tighter fit.Footnote 1

Importantly, however, all languages employ a mix of both word-external and word-internal processes. What differs is the overall quantity and reliance on each within the language type in question. It is not that German does not have lexical entries and structures requiring word-external processing. It does, just like all languages do, and some of these have even increased in the history of the language (through, e.g., morphological syncretisms in its case marking since Old High German; cf. Fischer Reference Fischer2013). It also has some that are without parallel in English, especially in the lexicon (cf. König & Gast Reference König and Gast2018). It relies on the direct object of its verb unterschlagen to distinguish between the meaning of embezzle (for Geld) versus suppress (for Information). But the point is that there are significantly more such properties assigned word-externally in English, and English has expanded them in its grammatical conventions considerably more than German has in the last 1,000 years, giving rise to all the contrasts documented in Hawkins (Reference Hawkins1986) and (Reference Hawkins2019).

By reformulating the basic contrastive typology in these terms we achieve three benefits. First, we can understand the historical drift of English better, as a general expansion in word-external property assignments, culminating even in certain structures like will travel and is traveling that increase the semantic expressiveness of surface structures compared with German. These counterexamples to the original tight-fit/loose-fit typology can now be subsumed under a higher and more psycholinguistic generalization for the history of English that subsumes both the clear contrasts and the exceptions to the earlier formulation: They all involve supplementing the words and structures in question with properties assigned word-externally in online processing. Second, the new formulation provides an explanation for something that was unaddressed previously, namely: If loose-fit languages involve significantly reduced surface forms with greater ambiguity/vagueness and deletions, etc., how do they achieve an expressive power that is comparable to tight-fit languages, in which disambiguation and semantic transparency are conventionalized in their words and structures directly and immediately accessed by selecting these words and structures and their form–meaning mappings in processing? The answer is that loose-fit languages supplement the form–meaning conventions of individual words and structures by exploiting neighborhood effects in processing, as shown in detail in Hawkins (Reference Hawkins2019), thereby achieving comparable expressive power to tight-fit languages and assigning comparable properties in processing by different means. And third, by shifting the emphasis from a more discrete typological contrast to a quantitative one, we position it so that its predictions can now be precisely assessed and tested on usage data and corpora from the languages in question. We now expect languages to vary quantitatively in the extent to which they rely on word-external versus word-internal processing, as a result of their general psycholinguistic profile and the kind of online processing preference that they exemplify, and we expect to see correlations between the predicted typological features in proportion to the quantities for the properties involved.

An example of this quantitative approach to the typology of tight- and loose-fit languages was given recently in Levshina & Hawkins (Reference Levshina and Hawkins2022), which examined the “lability” of thematic role assignments to subjects and objects in alternations like The woman opened the door versus The door opened in a multilingual electronic corpus. The existence of productive alternations like these is characteristic of loose-fit languages, and assignment of the appropriate thematic roles to the arguments in these transitive and intransitive counterparts crucially requires word-external access to the verb in addition to recognition of the subject or object relations, however these are coded. The other properties that were shown to correlate with this kind of verb-argument lability in the corpus were those typical of loose-fit languages, such as little or no case marking, rigid order of subject and object, and a high proportion of verb-medial (SVO) clauses.

The present article on relative clauses is also quantitative in nature, it uses a parallel corpus of these two languages, and it focuses on general features of the tight-fit/loose-fit typology that have defined it from the beginning and that are characteristic of the English/German contrasts and exemplified in this structure: They involve the ambiguity of surface forms, deletion of arguments, and separation of arguments from their subcategorizers. What we see in language usage, and specifically in these translations of common propositions made by many native speaking writers and by bilingual translators of the two languages, is the same kind of contrast between these languages in performance that can be found in the great majority of their grammatical contrasts, even though both languages possess an identical finite relative clause structure that could have been selected on all occasions and that was used by at least one of the languages in all 700 instances. The grammars of these two languages also share several reduced noun-modifier counterparts like the N-PP structure with less syntactic complexity. Yet it is generally English that selects these. German prefers semantically more explicit relatives in actual usage and translation, fewer ambiguous and multi-purpose phrases modifying nouns, less deletion of arguments within these clauses and less separation of arguments from their subcategorizers, so giving us the tighter fit again between form and meaning even in an area where it does not strictly need to because numerous parallel structures exist. These contrasting structures require more word-external processing in English, therefore, disambiguating the ambiguous nominal modifiers and recovering deleted material by accessing the head of the relative, and linking arguments to their subcategorizers over longer distances.

Section 2 summarizes relevant background research for this kind of comparative cross-linguistic study of relative clauses. Section 3 describes the parallel corpus of German and English that was used. Section 4 gives numerous examples from the corpus of the different relative clause types and their equivalents, which are then tabulated and quantified in section 5. Section 6 discusses the theoretical significance of these quantified contrasts, and section 7 concludes.

2. Postnominal relatives and their equivalents in cross-linguistic comparison

Relative clauses have received significant attention in cross-linguistic comparison ever since Keenan & Comrie’s ground-breaking work in 1977 establishing the “Accessibility Hierarchy” for positions that the head of a relative (der Junge/the boy or der Koffer/the suitcase in the examples above) can “relativize on” within the relative clause. In der Junge, der den Koffer trug/the boy who carried the suitcase the head noun der Junge/the boy plays the role of subject in the relative clause: It was he who carried the suitcase. In der Koffer, den der Junge trug/the suitcase that the boy carried, the head der Koffer/the suitcase is the direct object in the relative clause: The suitcase is such that the boy carried it. Keenan & Comrie showed that languages could vary in interesting ways both in how many positions on their hierarchy they could actually relativize on, and in the precise surface form of the relative clause, for example, whether it preserved a pronoun of some sort in the position relativized on (corresponding to the suitcase that the boy carried it, which one finds in Hebrew, versus the suitcase that the boy carried O as in English, where there is a gap in place of the Hebrew pronoun; see Ariel Reference Ariel1999 and Hawkins Reference Hawkins2004:183–185 for concrete examples from Hebrew). More generally Keenan & Comrie (Reference Keenan1977) and Keenan (Reference Keenan1972) showed that cross-linguistic variation in areas such as relative clause formation can be better described and explained in terms of how closely the surface syntax of a grammar preserves features of its corresponding semantic structure.

The ordering of head noun and relative clause also varies across languages. Most languages position the head noun before the relative, N-Rel. But among languages with basic subject-object-verb (SOV) order, especially those with rigid verb-final verb positioning like Japanese and Korean, the relative clause often occurs to the left of its head, Rel-N (see Lehmann Reference Lehmann1984, Dryer Reference Dryer, Haspelmath, Dryer, Gil and Comrie2005). Certain other variants in surface syntax are also found across languages, such as when the head is actually internal to the relative clause and yet this clause is still interpreted semantically as its modifier, as in the Hokan-Yuman languages Diegueño and Yavapai (see again Lehmann Reference Lehmann1984, Dryer Reference Dryer, Haspelmath, Dryer, Gil and Comrie2005, Keenan Reference Keenan1972).

Keenan & Comrie (Reference Keenan1977) drew our attention to the fact that relative clauses are complex structures syntactically and semantically. They involve two clauses in which the head plays a grammatical role both in the higher clause and (a possibly different role) in the lower clause. The head NPs in our illustrative examples, Junge/boy and Koffer/suitcase, could potentially be subjects or objects or oblique NPs within prepositional phrases (PPs) in the higher main clause, and either subject or object or oblique NP in the relative clause itself. Yet despite this complexity of having a clausal modifier embedded within a higher clause, and a possibly different grammatical role for the head and position relativized on, relative clauses are frequently occurring in language use, and they also appear to be universally present across languages, albeit in the different forms and with the different restrictions that Keenan & Comrie documented.Footnote 2

The productivity of relative clauses despite complexity is plausibly because they are vital for communicative reasons. They are often needed semantically so that the speaker or writer can identify and describe a particular referent, e.g. der Junge/the boy or der Koffer/the suitcase, by linking it to a particular proposition, a whole clause, which is true of that entity and which thereby picks it out and distinguishes it from others in natural discourse Since these early publications in language typology the relative complexities of the different relative clause types defined and predicted by Keenan & Comrie’s hierarchy have been largely corroborated by a now massive research literature testing the predicted grammatical variation and its correlates within the fields of language processing, second language learning, first language learning and corpus linguistics, in addition to language typology itself.Footnote 3

A distinctive feature of relative clauses shared by German and English, and one which is interestingly characteristic of European languages generally (Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath, Haspelmath, König, Oesterreicher and Raible2001, Lehmann Reference Lehmann1984), is the presence of the so-called relative pronoun (der, das, die, den, dem, dessen, deren in German, who, whom, which, whose, also that in English).Footnote 4 These pronouns differ from the “resumptive” pronouns of Hebrew (corresponding to the suitcase that the boy carried it), which resemble other pronominal forms in these languages, but they are logically similar to them in that they also provide an explicit surface form for Keenan’s (Reference Keenan1972) bound variable within the relative. They are characteristic of relative clauses as such, however, and undergo fronting to the leftmost position of this clause, they bear morphological case marking appropriate for identifying the role of the head in the relative clause (especially in German with its richer case-marked forms, more productively in earlier English with its who/whom distinction for relativizations on subject versus object), and they also show agreement with the head noun (in case, gender, and number for German and in animacy for who versus which, etc., in English), (see Hawkins Reference Hawkins1986: ch. 2 for comparative details, Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985 for English, Eisenberg Reference Eisenberg1999 for German). The German relative pronouns are largely derived historically from definite articles and demonstrative determiners and are distinguished from these through their syntactic positioning (postnominal and initially within the clause versus the prenominal determiner position) by the kind of word-external property assignment described in Hawkins (Reference Hawkins2019). The corresponding forms of English are derived ultimately from wh-question words and from the demonstrative pronoun that.

With this much background we are in a position to classify and code the different kinds of relative clauses found in German and English, and also their noun-modifier alternatives in translation. We first present the corpus itself in the next section.

3. The parallel corpus for the current study

Four published books of parallel written texts were used in which German and English were juxtaposed on pages side by side. This made it possible to identify the exact structures that corresponded to one other. Two of the books were translations from German to English, the other two were from English to German.

The German to English translations were Parallel Text German Short Stories 1 Deutsche Kurzgeschichten 1, edited by Richard Newnham (Penguin, 1964), and Parallel Text German Short Stories 2 Deutsche Kurzgeschichten 2, edited by David Constantine (Penguin, 1976). The first contained eight short stories by eight twentieth-century authors writing in German, with eight different translators. All of its 151 pages of parallel text were searched and coded for a postnominal relative clause occurring in at least one of the languages. From the second book the first 104 pages were searched in a similar manner. These pages were taken from four twentieth-century authors writing in German who were distinct from those in volume 1, with different translators as well, making twelve authors altogether and twelve translators. See the Appendix for further details about these two books and their various authors and texts. These pages were searched carefully for the first 350 instances in which at least one of the languages employed a finite postnominal relative clause. The precise structures used in each language were then analyzed and counted.

The first book used for the English to German translations was Take It Easy Kurzgeschichten, edited by Richard Fenzl (Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 2013). It contained nine short stories by English and American authors from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with four different translators. All of its 179 pages were searched for examples in which at least one employed a finite postnominal relative. This supplied 264 instances. Further instances came from the first 54 pages of a selection from Mark Twain’s Germany and the Awful German Language/Deutschland und die schreckliche deutsche Sprache, edited and translated by Harald Raykowski (Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 2023). The result was ten different authors and five translators for these English to German texts, to reach the 350 instances matching the German to English data, with 700 instances overall. Again see the Appendix for full details of the authors and texts.

The corpus used in the present study was accordingly a written one of a literary nature. This is clearly a limitation and one that future studies will need to address by seeing whether the contrastive patterns documented in this genre generalize to spoken translations and to other written genres (e.g. journalism, academic prose, etc.). This corpus does control for the directionality of translation, however, by providing equal numbers of German to English and English to German data, and some interesting differences were found in these different directions (see section 5) sufficient to suggest that manipulating the different variables of language use and translation (different genres, different social contexts, different directionalities) could be a fruitful area for future research.

Another limitation of the present corpus is that it is a convenience sample, in several respects. These books were already available to me and they happened to contain the texts in question. Having them in book form enabled me to readily write in and annotate the books themselves, and to highlight the relevant structures that corresponded to one another, and to code them as exemplified in the next section. Other parallel corpora exist, in other books and in many cases in downloadable electronic form. I had sufficient examples in the books already available to me, however, to fill the time I had available for this project, and there were enough instances of the overlapping and divergent structures across the two languages to reveal some real trends in the data of relevance to the theoretical background raised in section 1 about contrasting form–meaning mappings in language typology. These contrastive trends were striking enough and clearly visible in the raw numbers and percentages and ratios shown in section 5 to make it unnecessary to employ the kind of sophisticated statistical analysis used in Levshina & Hawkins (Reference Levshina and Hawkins2022).

Future researchers can put the qualitative and quantitative findings of this study to the test, in these and other data of this type and in other genres. In the meantime the present study exemplifies a way of quantifying the key parameters of variation from the tight-fit/loose-fit typology (ambiguity, argument deletion, and argument–subcategorizer separation) as they apply to certain noun modifier structures in a parallel corpus. Electronic corpora are now available for German and English translations that are both tagged and parsed. I chose to do my own tagging and parsing manually for this study. Many corpora are now parsed by automatic parsers of different kinds, but manual tagging and parsing achieves a higher level of accuracy, especially when done by someone with decades of experience in grammatical comparison and syntactic analysis. My knowledge of both English and German also enabled me to make informed judgments about the equivalences, or lack thereof, between various structures in the two languages. Future studies can again put all of this to the test in different ways, using larger parallel corpora, either manual or electronic, more controlled text selections (e.g. all late twentieth century, British and not American or vice versa, German and not Austrian, etc.), and with different analysts and parsers.

4. Exemplifying the different relative clause types and their equivalents

In this section we give concrete examples of the various relative clauses and their equivalent nominal modifiers that were found in the parallel corpus. We also introduce the coding scheme, which builds on the typology of Keenan & Comrie (Reference Keenan1977) for descriptive purposes. It is not a major goal of this study, however, to test some of their predictions for text frequencies for the different positions on their Accessibility Hierarchy (though see note 8 below for quantities in the parallel corpus that are relevant for these predictions). In all the examples selected and presented below, the (a) version represents the original source language and (b) its translation. In the interests of space and clarity the material excerpted from each sentence is reproduced here in the shortest possible form that reveals the structural type in question. Where the German structure diverges significantly from the English one, such that a gloss would be useful for readers who are not specialists in German, this is given in addition to the actual corpus translation. Where the two languages are structurally parallel, the English version itself can serve as the translation.

The most common relative clause type found in both languages involves relativization on a subject (see note 8 in the next Section). This is exemplified in (1) where Buntphoto/colored photograph is the subject of the finite verb hing/hung within the relative clause:

The relative pronouns here are das in German, agreeing in neuter gender and number with the head noun, and which in English, agreeing in animacy, both clearly functioning as underlying subjects in the relative clause even though both are morphologically ambiguous and could in other relative clauses function as objects (the subject relation here is a word-external property as discussed above, assigned by accessing the immediately following verb in English and for German the verb plus the remaining pre-verbal material). The coding label used for this finite relative type with relative pronoun is N-Rel(S).

These relative pronouns provide an explicit form in surface structure that refers to an entity in the relative clause that is identical to the head. As mentioned in section 2, this entity corresponds to the bound variable in Keenan’s (Reference Keenan1972) logical structures (roughly ‘the colored photograph is such that it hung over the sofa’), and having it present rather than absent means that more of the logical structure is preserved in the surface form. The pronoun also makes explicit the role of the head within the relative, in combination with word-external processing, and so helps the language user parse that role clearly within the relative clause structure itself.

The next relative clause type down the Keenan–Comrie hierarchy involves relativizing on a direct object, as seen in (2) in which die rote Limonade/the red lemonade functions as the direct object of getrunken hatte/drank in the lower clause. This is coded as N-Rel(O):

The relative pronoun agrees now in (feminine) gender and number with the head noun in German, and in animacy with the head in English, and these pronouns which are again morphologically ambiguous between subject and object and disambiguated word-externally in favor of the latter by the immediately following subject pronouns ich/I, make clear that the relative pronouns must be direct objects within the relative clause.

A productive variant of the object relativization type, found in English only, permits deletion of the object relative pronoun, and hence removal of the entity corresponding to the bound variable in Keenan’s semantic structures. This is coded as N-ØRel(O) in (3a):

The German translation in (3b) preserves the relative pronoun die and is coded N-Rel(O) as before.

The third position down the Keenan–Comrie (Reference Keenan1977) Accessibility Hierarchy has been labeled “non-direct-object” in Comrie (Reference Comrie1989:155) and will be labeled here as “oblique” and coded N-Rel(Obl). It is exemplified in (4):

Typically, this subtype subsumes relative clauses in which the position relativized on occurs within a PP in its clause, and the relative pronoun then occurs within a fronted PP structure (“Pied Piping”) exemplified here by in which/in der. In the case of English, the preposition could also be stranded (which the Still might be found in is grammatical). This is seen in (5a) with the stranded preposition to. (5a) also exemplifies relative pronoun deletion for an oblique pronoun and is coded N-ØRel(Obl):

A variant corresponding to oblique relativizations in English is unique to German on account of its distinctive Dative case marking for indirect objects (and coded N-Rel (IO-Dat)). It is exemplified in (6a), with the English translation (6b) being N-Rel(Obl):

The next position down the Keenan–Comrie hierarchy is the genitive. This is the most complex, and the least frequent, position for the head to occupy in the relative clause (see the figures in note 8 below), because it is more deeply embedded structurally than the other positions on the hierarchy. The various relative pronoun words in the two languages that function as genitives are found in the corpus within a higher subject NP (coded as N-Rel(GenS)), within an object NP (N-Rel(GenO)) and within an oblique (N-Rel(GenObl)).

The first of these is exemplified in (7), in which the genitive of which/dessen occurs within a higher NP the value of which/dessen Wert functioning as subject of the lower predicate was priceless/unschätzbar sei:

Relativization on a genitive within a direct object is exemplified in (8):

And relativization on a genitive within an oblique phrase is shown in (9):

On some occasions an oblique relative clause with a relative pronoun in a PP in one language was translated by a semantically equivalent clause in the other language containing a more semantically specific relativizer: for example, where/wo specialized for locative relations, when/als for time phrases, and how/wie for manner. An example is (10) with a locative where in English (10b) corresponding to an oblique relative clause in the German (10a):

Since noun-modifying clauses such as (10b) with relativizers like where are semantically just like the relative clauses considered so far, it was decided to search for these systematically as well. The only difference is that these locative and other relativizers are specialized for certain semantic types like places and times, and require semantically appropriate head nouns.

The following examples illustrate these more specialized relatives and the coding system used:

The example in (13a) shows a reduced nominal modifier with a PP in English corresponding to an N-Rel(Manner) in German (13b) with the specialized relativizer wie:

A further instance is the reason why in the English (14b) (coded N-Rel(Cause)). It translates a different structure altogether involving a non-relative subordinate clause. Since the two languages are equally explicit semantically in the proposition being expressed, and since the contrast is not one of nominal modification, which is the central focus of this article, the German example is simply coded “Subordn.Cl”:

There are several noun-modifier structures in English and German that can be syntactically reduced and yet translated by a full relative clause in one or the other language. Semantically these reduced modifiers are always interpreted as having the same meaning as a finite relative clause in which the head noun occupies the role of grammatical subject (either active or passivized) of the lower clause. An example is (15a) in German with N-Rel(S), which was translated into English (15b) as an N-PP:

Another example with a different preposition in English is (16a):

Noun-modifier reductions are more characteristic of English than German (see table 3), but sometimes the contrast goes the other way, as shown in (17):

The reduced nominal modifier can take a number of different syntactic forms in addition to PP. It can be an adjective phrase like more destructive of each other than …, exemplified in (18a), which corresponds to the full, finite N-Rel(S) of German (18b):

Even a single-word (pre-nominal) adjective in English can be rendered as a full relative clause in German, as in (19). This time German (19b) uses an N-Rel(O) for the active counterpart of the passive participle registered in the English (17a):

A following adverb phrase with here and there down the columned aisles of the forest in English corresponding to a German N-Rel(S) is seen in (20). Part of the content of the German relative clause, corresponding to the verb huschten in (20b), has been moved into prenominal position in the English (20a) in the form of a second prenominal adjective in present participle form, flitting:

A common reduced postnominal phrase in English is with a VP and the verb in present participle form, coded as N-VPing. An example is (21a) in which the VP is headed by being:

The VP can also be headed by a past participle in passivized form e.g. perforated in (22a):

Another type of VP reduction in English is with an infinitival verb preceded by to:

Meanwhile, German grammar permits the N-PP reduction type illustrated in (17a), as well as several other possibilities with AdjP, Adj, and VP that have close correspondences with their English counterparts but are less frequently occurring (see table 3). Here we give an example of an N-VP(PastP) in German (24a) corresponding to an N-Rel(S) in English (24b):

We also exemplify the distinctive pre-nominal relative clause, or extended attribute, of German, coded here VP-N(S) since the position relativized on must always be a subject and the verb is either a past (passive) participle as in (25a) or a present participle as in (26a). The English translations (25b) and (26b) use an N-Rel(S) with an active finite verb.

The glosses in (25a) and (26a) show that English has no corresponding prenominal structures in these instances. They also show that this prenominal German VP is not finite, and that there is no relative pronoun within it that makes explicit the (subject) position relativized on.Footnote 5 Hence, like the corresponding post-nominal VP phrases of English, the VP-N(S) of German is a less explicit surface form with no pronoun corresponding to the bound variable in semantic representation.

The heads of relative clauses and their nominal modifier equivalents can often be pronouns rather than full lexical nouns within NPs. An example with the deictic pronoun jener (literally ‘that one’) is shown in (27a), translated by he in English (27b), both being followed by a clause relativizing on the subject position and coded Pro-Rel(S):

Relativization on an object with a pronominal head is given in (28), with the English (28b) also exemplifying relative pronoun deletion:

And a location relative clause with specialized wo/where relativizer is exemplified following a pro-form in German (dort, literally ‘there’) in German (29a), which is translated by a lexical locative noun in the English (29b):

One productive difference between German and English, both in grammar and in usage frequencies, concerns the extent to which the fronted relative pronoun is permitted at some distance from the subcategorizer (V or P) that governs it. In this study we quantify the number of instances in which the argument corresponding to the head and relative pronoun (if present) is separated by another subcategorizer from its actual subcategorizer within the relative clause, and we code such cases as +ASS (standing for +Argument Subcategorizer Separation). An example is (30a) in English in which the subcategorizer for the head spot (and for the deleted relative pronoun) is the preposition of, and this preposition is stranded and separated from spot by the subordinate finite verb speak:

The German translation (30b) with Pied Piping of the preposition + relative pronoun combination maintains the relative pronoun as an immediate sister of the preposition von in the PP, both being fronted and adjacent to the head noun Stelle. The verb reden does not now intervene between them.

Further cases of argument–subcategorizer separation can occur when an argument has been raised into a higher subject or object position within the relative clause by one of the different raising operations that are productive in English but much less so in German (Hawkins Reference Hawkins1986: ch. 5; cf. also Shannon Reference Shannon1987, Postal Reference Postal1974, Van der Auwera & Noël Reference Van der Auwera and Noël2011); or else extracted by WH-movement applying into a higher clause by a process that is productive in both languages, though more extensive in English (Hawkins Reference Hawkins1986: ch. 6). An example of the former with the intervening Subject-to-Subject raising verb kept in English is found in (31a). The relative pronoun who is separated here from its semantic predicate and subcategorizer saying by the raising verb, hence this is coded +ASS:

German renders the semantic content of the higher verb kept using the adverb ständig in (31b), with the result that the most immediate predicate and subcategorizer (V or P) for the pronoun die (referring back to the head Carrie) is the verb sagte and there is no intervening V or P that separates them.

In (32a) we see an instance of WH-movement in which the fronted relative pronoun which is linked syntactically and semantically to the verb accept as its object. There are now two intervening verbs in this English example as potential but not actual subcategorizers, pleased and allow, hence +ASS2:

The German translation (32b) again converts one of these to an adverb, gern, corresponding to was pleased, so removing one potentially intervening subcategorizing verb. The tree geometry of the relative clause, which contains a lassen construction, is interesting in that the closest verb syntactically to the fronted relative pronoun, measured in terms of branching phrase structure nodes, is actually the higher verb liess rather than the lower verb annehmen, which is the proper subcategorizer. If +ASS were defined solely in terms of the fewest branching nodes separating the relative pronoun from its subcategorizer, therefore, then liess would count as an intervening subcategorizer closer to the relative pronoun, making (32b) +ASS as well.Footnote 6

However, note that the true subcategorizer annehmen is closer to the relative pronoun and head in linear distance than the higher verb liess, and it is the first one that the parser will encounter after the relative pronoun. It is counterintuitive, therefore, to say that the relative pronoun has been separated from its subcategorizer under these circumstances by this higher verb, and I will propose a definition for +ASS in (33) that results in a coding of no ASS for the German (32b), contrasting with +ASS2 for English (32a). The earlier positioning of the verb in English compared with German means that the higher verbs pleased and allow do genuinely separate which from accept both in terms of branching structure and in terms of linear distance.

The German (32b) satisfies the first part of this definition but not the second since the actual subcategorizer is not closest to the relative pronoun in branching nodes but is closest to it in linear distance. Hence it is not coded as +ASS.

Finally, consider an example in which a relative clause in one language has a main clause paraphrase in another (coded Main.Cl). Since both versions are comparable and semantically explicit and the full argument structure of the head and position relativized on is expressed within a main clause translation, these will be of less interest in the present context in which one of the main goals is to document reductions between form and meaning in the translations.

5. Results

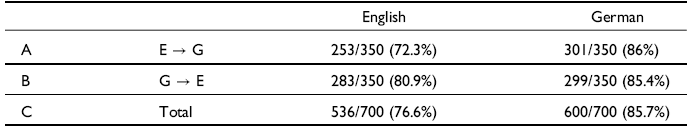

We now summarize the contrastive usage data for finite relative clauses and their reduced equivalents in the parallel corpus. Table 1 shows the overall number of post-N and post-Pro finite relatives in each language (with or without relative pronoun deletion in the case of English), that is, with a finite relative as opposed to a reduced nominal modifier or alternative subordinate clause or main clause paraphrase. The English totals are given in the left column, with German on the right. The first row A gives figures for the English to German translations (E → G), the second row B the figures for German to English (G → E), and the third row C gives the totals.

Table 1. Post-N and post-Pro finite relatives

Overall, finite relative clauses are more frequent in German than in English. A full 600 of the 700 items in the German data are post-N or post-Pro finite relatives (85.7%). The English total is 536 of the 700 (or 76.6%). The number of these is higher in the direction from German to English (row B, 80.9%) than in the English to German direction (row A, 72.3%). This presumably reflects the attempts by translators to preserve structures from the German source materials wherever possible.Footnote 7

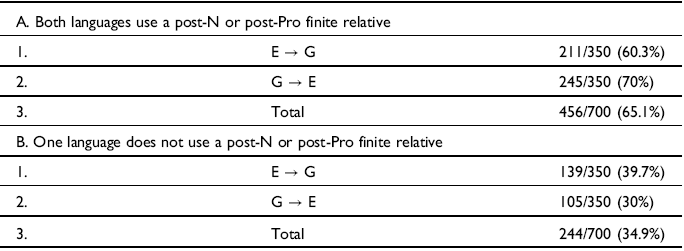

Table 2 gives the figures for post-N and post-Pro relatives not in terms of their overall total occurrences in each language, but in terms of their correspondences or non-correspondences across languages for each item. Rows A1, A2, A3 give the correspondences, that is, when both languages used a post-N or post-Pro finite relative. Rows B1, B2 and B3 show when there is a non-correspondence and one language does not use the post-N or post-Pro finite relative.

Table 2. Correspondences and non-correspondences between English and German

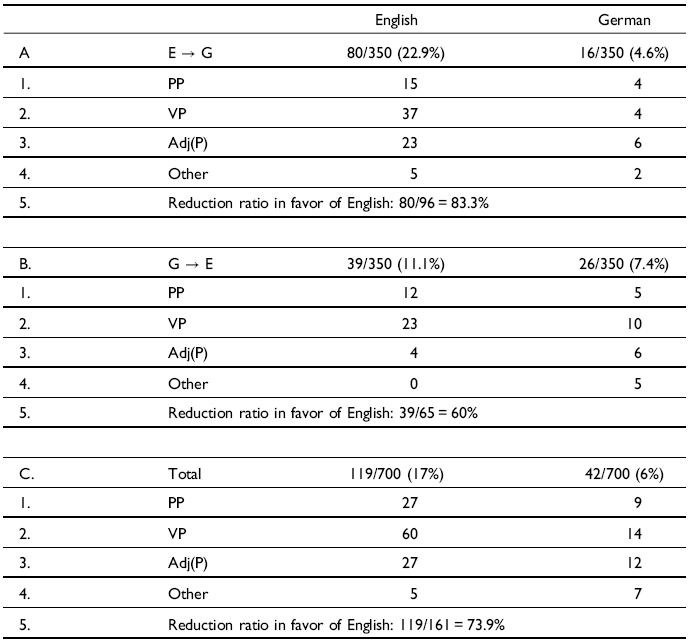

Table 3. Reduced nominal modifiers in English and German

A full 244 instances out of the 700 (34.9%) involve one of the languages not using a finite relative when the other does (see row B3). Again the correspondences, and retentions of the finite relative, are higher from German to English (at 70%, row A2) than from English to German (at 60.3%, row A1) (see note 7).Footnote 8

Table 3 looks now within the non-correspondences of table 2 and gives the quantities of reduced nominal modifiers in one language corresponding to a finite relative in the other. Row A gives the number out of 350 for English (80 or 22.9%), and the number for German (16 or 4.6%) in the English to German translations. Rows A1 to A4 give the bare numbers for the major reduced phrasal types in question, PP, VP (which subsumes the subtypes with present participle, past participle and infinitival exemplified in (21)–(26) above), Adj(P) and Other (such as AdvP). Row A5 shows that of the 96 total reductions compared to a finite relative in this data set, it is English that has the much higher proportion of 80/96, or 83.3% versus just 16.7% for German. There are five times more reductions in English than for German in this half of the data (see again note 7).

Row B gives the number of reductions out of 350 in the German to English translations. The total for English is now less than half of that in the E → G direction, 11.1% versus 22.9% in row A, while the number for German is slightly higher in the G → E direction than in E → G, 7.4% in row B versus 4.6% in row A. The number of reductions in English is just one and a half times that of German in this G → E half of the data (39 versus 26). Rows B1–B4 give raw numbers for the different types of reduced nominal modifiers, and B5 quantifies the proportion of reductions in this data set which still favors English, but by the smaller margin of 60% to 40%, compared with 83.3% to 16.7% in row A5. This all means that translators from the German original were more faithful in preserving the German preference for finite relatives and in reducing these to a lesser extent (see row B), than translators from the English originals were in preserving the significant number of reduced nominal modifiers (22.9%) in English shown in row A. Rows C and C1–C5 add up the quantities for the higher rows in A and B and give total figures and ratios. We will consider the significance of these higher reduction figures for English in the next section in terms of the greater ambiguity of the resulting nominal modifiers and their word-external disambiguation through access to the head noun in question.

When the number of finite relative clauses in German in table 1 (600, row C) is added to its reduced modifiers of table 3 (42, row C), giving 642, there are 58 remaining. These involved paraphrases of relative clauses using other subordinate clauses or main clauses, as exemplified in (14) and (34) above. Similarly for English there were 45 such cases remaining in addition to the 536 finite relatives in table 1 (row C) and the 119 reduced modifiers in table 3 (row C). These paraphrases were largely equivalent in semantic explicitness and argument structure to finite relative clauses with relative pronouns, so they are less relevant in the present context of form–meaning mappings in the noun phrase and their degrees of semantic explicitness compared with finite relatives.

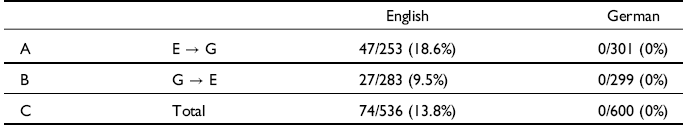

Table 4 shows the number of times a relative pronoun was deleted on non-subject positions in finite relative clauses in English (see examples (3a) and (5a) above), again breaking the data down into E → G (row A), G → E (row B) and Total (row C). It is readily apparent that German has no such deletions, whereas in the English originals of row A such deletions are found in 47/253 or 18.6% of the data and in 13.8% overall (row C). The translators from German originals shown in row B used only roughly half as many deletions (9.5%) as in row A (18.6%), reflecting once again their attempts to preserve more features of the German when this was also an option in English.

Table 4. Non-subject relative pronoun deletions in finite relatives

Table 5 combines the quantities from tables 3 and 4, in both of which there has been a removal of a lower argument corresponding to the bound variable in Keenan’s (Reference Keenan1972) semantic structure for relative clauses. Either this has been removed by reducing the finite relative clause to a reduced nominal modifier, PP, VP, etc. (table 3), or it has been removed by deleting the relative pronoun as such within the finite relative (table 4).

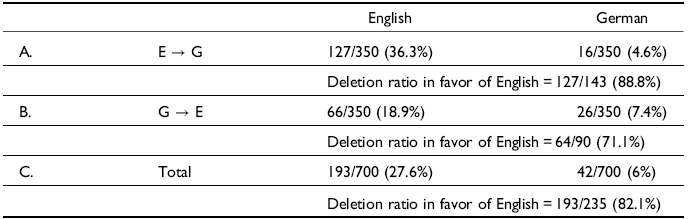

Table 5. Argument deletions in nominal modifiers through reduced nominal modifiers (Table 3) plus non-subject relative pronoun deletion (Table 4)

Row A shows an overall argument deletion ratio of 88.8% to 11.2% in favor of English in the E → G data (by adding up 80 from row A in table 3 and 47 from row A in table 4 to give the English 127/350 and the corresponding 0 + 16 for German, making 143 argument deletions in total out of the 700). Proceeding similarly, row B in table 5 shows a deletion ratio of 71.1% in favor of English for the G→E data, which is still much higher than the reverse 28.9% for German, though it is less than the 88.8% deletion ratio for English shown in row A. Row C gives the combined argument deletion ratio in favor of English of 82.1% to 17.9%.

A reviewer pointed out that this argument deletion ratio in favor of English will be even higher if the that relativizer is analyzed as a subordinating conjunction and not as a relative pronoun (following Huddleston & Pullum Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002:1056; see note 4), since all the finite relatives with that will then be instances of argument deletions within the relative clause, even when relativizing on a subject (as in students that like linguistics), and not just those of table 4 with clear non-subject relativizer deletions. I accordingly reexamined the data and found that 77 of the 536 English finite relatives of table 1 had a that relativizer (32 in E→G, 45 in G→E). If we add these 77 to the reduced nominal modifier and non-subject relative deletions in table 5 we have a total of 270/700 argument deletions in English relative clauses, and a higher deletion ratio compared with German of 270/312 or 86.5%, compared with the 82.1% shown in table 5 row C.

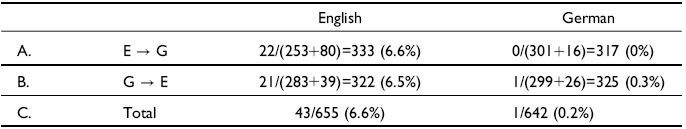

Finally, table 6 gives the argument subcategorizer separation totals (recall examples (30)–(32) above). Rows A, B, and C divide up the data as before. The English totals are 22 in row A and 21 in row B out of 333 and 322 possible structures respectively in which there could have been an +ASS coding. The 333 total in row A comprises the 253 finite relatives in table 1 row A and the 80 total reduced nominal modifiers in table 3 row A. Both of these nominal modification types could potentially be +ASS (as in the man who was most likely to succeed with a full relative containing a subject-to-subject raising predicate and the man most likely to succeed with an AdjP containing the same raising predicate). The 322 total from row B consists of the 283 from table 1 row B and the 39 from table 3 row B.

Table 6. Argument subcategorizer separations

The overall frequency of occurrence for these +ASS structures in the English data (row C) is 6.6%. What is striking is that there is only one single instance of this in the corresponding German relative clauses and reduced modifiers (row C). This shows that there is a real aversion to actually using these argument-subcategorizer separations in German, even when they can be grammatical in both languages (which they often are, especially for WH-extractions, see Hawkins Reference Hawkins1986: chs. 5 and 6).

6. Discussion

The first, empirical, goal of this study was to quantify the cases where German and English employed the same full and unambiguous finite relative clause structure versus cases where they diverge from one another. Of particular interest were translations that involve alternative constructions with reduced noun modifiers. These quantities have now been summarized in the tables of the last section.

A second, more theoretical, goal was to try and explain the directionality of contrast in language use, as seen in a parallel corpus in which a common set of propositions and of nominal references are being rendered in the two languages. More specifically the goal was to extend an idea that has been proposed for contrasts in the grammatical conventions between German and English into the preferences for structural selections in performance, even in an area where there is considerable overlap between the two languages in their grammars. As mentioned in section 1, Hawkins (Reference Hawkins1986) proposed that where German and English grammars contrast, it is generally German that is semantically more explicit and more transparent preserving more features of its corresponding semantic representations. German gives us a “tighter fit” between form and meaning, English a “looser fit” that relies more on the word-external processing of forms and meanings described in Hawkins (Reference Hawkins2019).

The relative clauses and their equivalents in the present study provide usage data from one particular semantic area where there is variation precisely along all the major dimensions of the tight-fit/loose-fit typology. German has a higher number of full finite clauses that are semantically unambiguous and unique to relative clause formation, 600 of the 700 in table 1 (row C) or 85.7%. These relatives also maintain all arguments of the relative clause without relative pronoun deletion (see table 4 row C). English uses fewer finite relative clauses, 536 of the 700 in table 1 (76.6%), of which 74 have undergone removal of the bound variable argument through relative pronoun deletion (table 4, row C), with the result that English has just 536 – 74 = 462/700 (66%) exact counterparts to the preferred 600/700 (85.7%) of German. It has even fewer counterparts if relatives with that are analyzed as subordinating conjunctions involving regular argument deletion (see note 4 and the data in the last section), namely 536 – 74 – 77 = 385/700 (55%). The English finite relatives are both less semantically complete and less unambiguously relative clause-like, therefore, compared with the German finite clauses containing a relative pronoun which serves to signal their relative clause status unambiguously.

The number of reduced nominal modifiers, meanwhile, such as PP and VP, is correspondingly higher in English, see table 3. These reductions involve removal of the finiteness of the relative clause plus deletion of what is semantically the grammatical subject argument within the modifier (the boy with the suitcase corresponds to the boy who had the suitcase). These reduced phrases are actually ambiguous in terms of the syntactic and semantic roles that they can in principle perform within a sentence (the PP could be a modifier of V not of N, the VP could be a predicate of a subject NP, and so on). They achieve their disambiguation as nominal modifiers of N or Pro through their positioning adjacent to N or Pro and through word-external processing generally looking left to the head noun (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2019). A total of 119 of the 700 are reduced nominal modifiers in English like this, compared with just 42 in German, making an overall reduction ratio of 119/161 (73.9%) in favor of English (table 3 row C). The grammars of both languages permit several overlapping reduced noun-modifiers like N-PP, and English is accordingly selecting more of these semantically less explicit and ambiguous phrases than German in performance.

Reduced nominal modifiers and deleted relative pronouns both involve removal of an entity that is present in the semantic representation of the full relative clause equivalent. Table 5 shows that this removal option was selected in 193/700 of the English cases, or 27.6% (row C). German has conventionalized the retention of non-subject relative pronouns in finite relatives (table 4) and permits removal in performance only for the non-finite nominal modifiers (see table 3). The resulting argument deletion ratio in the noun modifying phrases and clauses of our parallel corpus in favor of English is 193/235, or 82.1% (table 5 row C), and this rises to 86.5% if that is counted as a subordinating conjunction only (see note 4). There are many more such deletions in English usage than in German.

Table 6 shows that there are also strikingly more separations in English of arguments from their subcategorizers by other subcategorizers (V or P), 6.6% versus 0.2% (row C). Once again German grammar has conventionalized the impossibility of such separations in some cases (e.g. preposition stranding). But there are numerous structures in which separations are grammatical in both languages (Hawkins Reference Hawkins1986: chs. 5 and 6), yet it is clear that they are highly dispreferred in German performance.Footnote 9

Summarizing, what we see in the data of the parallel corpus is the same pattern in the contrasts of language performance as we see generally in their contrasting grammars and extensively in the lexicon as well. Both languages share a finite relative clause that could have been selected on all occasions, plus several overlapping reduced nominal modifiers with subject argument deletions, plus several shared options for separating arguments from their subcategorizers, yet it is regularly German that prefers the semantically more transparent relatives in usage and translation. Users of German have a clear dispreference for selecting ambiguous and multi-purpose phrases modifying their head nouns and pronouns, for deletions of arguments within these phrases, and for separations of arguments from their subcategorizers. Users of English have no such dispreferences and these surface forms occur frequently, especially in the English originals (see table 3, row A), but also with significant frequency when translating from German originals in which the full and semantically explicit finite relative is the most preferred option in 299 of the 350 instances (85.4%), see table 1 row B and table 3 row B. When these ambiguities, deletions, and separations occur they activate word-external processing operations as described in Hawkins (Reference Hawkins2019) that effectively reconstruct and assign semantic properties to the reduced surface forms within a loose-fit language that correspond to the properties that are explicitly linked to them by the conventionalized form–meaning mappings of a tight-fit language.

German is not only conventionalizing a tighter fit between form and meaning in its grammar, therefore, it is giving us a tighter fit between form and meaning in actual usage in an area where it does not strictly need to, and in translations from semantically less explicit nominal modifiers in English for which German often has close counterparts that it could have used instead of the finite relative plus relative pronoun. Semantically explicit surface structures, and less word-external processing, are clearly a characteristic of both grammar and usage in German. The conventions of German rule out deletion of a relative pronoun and of various argument–predicate separations and these can be seen as the tip of an iceberg that requires a faithfulness to its semantic representation that we have now documented in performance as well. This is a further instance of what Hawkins (Reference Hawkins2004) has called the Performance-Grammar Correspondence Hypothesis, whereby grammars conventionalize the preference patterns of performance.Footnote 10

There are some other patterns in the tables of the last section that are interesting and that merit further research, but are not a primary focus of the present article. First, tables 1, 2, and 3 show that full finite relatives in English are preserved more in the German to English direction than in the reverse. I assume this is because translators are making an effort to preserve features of German grammar and usage, employing options of English whenever they can do so grammatically, whereas these parallel options are less preferred in the spontaneous English of the English originals.Footnote 11 The question this raises is then why translators into German do not reciprocate and render more of the reduced nominal modifiers of English into German using parallel structures that are often available (table 3, row A). I have speculated (in note 7) that a loose-fit language like English may have a greater tolerance for both semantically explicit and less explicit surface forms, whereas a tight-fit language like German, with its systematic preference for semantic explicitness, may be much less tolerant of loose-fit alternatives. There are always processing advantages when meanings are clear and transparent and this could make English more amenable to preserving the semantic explicitness of German, while German would be less amenable to preserving the reductions and separations of loose-fit English and to activating word-external processing in a structure where semantic explicitness is clearly preferred. This should be examined further in the context of translation theory and practice and using proper statistical tests, since some of the differences in directionality are small and need statistical confirmation. This is not a primary focus of the present study, however, where the focus is on the form–meaning mappings themselves and on language typology and where the quantitative patterns we have focused on can be seen quite clearly using raw numbers and percentages and in the relative proportions of selections for the different structural types in the two languages.

Second, the usage frequencies for the different relativization positions on the Keenan–Comrie Accessibility Hierarchy shown in note 8 are interesting and broadly in line with their (greater or equal) relative frequency ranking for adjacent positions on the hierarchy. This is of potential relevance for actually explaining why the hierarchy has the ranking it does and what the precise grammatical and processing motivation for it is (see Hawkins Reference Hawkins2004, Diessel & Tomasello Reference Diessel and Tomasello2006, Lau & Tanaka Reference Lau and Tanaka2021). Whether all of the component predictions made by the hierarchy are fulfilled, however, requires a more detailed analysis of some of the strategies of English and German that are coded here in relation to the hierarchy, as mentioned in note 8. The Keenan–Comrie Accessibility Hierarchy has been employed in this article for primarily descriptive and coding purposes, and testing its relative frequency predictions is again not a primary focus.

Notice third that the usage frequencies presented here are taken from written literary samples only. It remains to be shown whether and to what extent the contrasts in usage within this genre generalize to spoken and other written genres, at different time periods, for different dialects of English and German, and so on (see section 3). The present article lays the groundwork for future studies of relative clauses and their equivalents in more controlled corpora, and of other constructions that exemplify variation in surface ambiguity, deletions, and argument–predicate separations.

7. Conclusions

We have seen that relative clauses and their equivalents in a parallel corpus show the same kinds of contrasts between German and English in language usage that are generally found in their grammatical contrasts, even though both languages possess a finite relative clause structure that is identical in crucial respects, plus several overlapping nominal modifiers with less syntactic complexity and less preservation of semantic structure. Yet it is English that regularly uses these less explicit alternatives. German prefers a finite relative clause structure in a full 600 of the 700 that is unambiguous and unique to relativization and that preserves more of a one-to-one mapping between form and meaning. It exhibits less deletion of arguments within this clause and a general dispreference for alternative modifying phrases that involve deletion of subject arguments and separation of arguments from their subcategorizers, so giving us a tighter fit between form and meaning in actual usage. English, by contrast, uses a greater number of ambiguous and multi-purpose noun modifiers, with more deletion of arguments both in these and in finite relatives, and with more separation of arguments from their subcategorizers, so giving us a looser fit between form and meaning. It compensates for this reduced explicitness and lesser semantic transparency by assigning properties through word-external processing of neighboring words and phrases, thereby enriching its semantic processing to match the conventionalized form–meaning mappings of tight-fit languages. German grammar and performance both exemplify the tighter fit between form and meaning, therefore, while English grammar and performance permit the looser fit, while also preserving certain features of the tighter fit of German in translation. The comparative typology proposed on the basis of conventionalized grammatical properties (see Hawkins Reference Hawkins1986, Reference Hawkins2019, Műller-Gotama Reference Müller-Gotama1994, and the further references given in section 1) has accordingly been shown in this area of relative clause and noun modifier semantics to have clear parallels in language usage as well, so supporting the Performance–Grammar Correspondence Hypothesis (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2004, Reference Hawkins2014).

Appendix

The four books that provided the parallel corpus for this study, with their respective contents, are the following. The first two are translations from German to English, the second two from English to German.

1. Parallel Text German Short Stories 1 Deutsche Kurzgeschichten 1, edited by Richard Newnham (Penguin, 1964), comprising:

“Pale Anna”/“Die Blasse Anna,” by Heinrich Böll, translated by Christopher Middleton, pp. 11–25;

“Story in Reverse”/“Spiegelgeschichte,” by Ilse Aichinger, translated by Christopher Levenson, pp. 27–51;

“The Host”/“Die Hostie,” by Hans Bender, translated by Roland Hill, pp. 53–75;

“Woman Driver”/“Dame am Steuer,” by Gertrud Fussenegger, translated by Patrick Bridgewater, pp. 77–85;

“Antigone and the Garden Dwarf”/“Antigone und der Gartenzwerg,” by Gerd Gaiser, translated by Dieter Pevsner, pp. 87–101;

“At the Trocadero”/“Im Trocadero,” by Wolfdietrich Schnurre, translated by John Cowan, pp. 103–119;

“When Potemkin’s Coach Went By”/“Beim Vorbeifahren der Potemkinschen Kutsche,” by

Reinhard Lettau, translated by Marie Surridge, pp. 121–131;

“Thithyphuth, or My Uncle’s Waiter”/“Schischyphusch oder Der Kellner meines Onkels,” by

Wolfgang Borchert, translated by Paul Dinnage, pp. 133–163.

2. Parallel Text German Short Stories 2 Deutsche Kurzgeschichten 2, edited by David Constantine (Penguin, 1976), from which the first 117 pages were selected comprising:

“The Dolphin”/“Der Delphin,” by Ernst Penzoldt, translated by David Constantine, pp. 11–49;

“Jennifer’s Dreams”/“Jennifers Träume,” by Marie Luise Kaschnitz, translated by Helen Taylor, pp. 51–69;

“Fedezeen”/“Fedezeen ” by Günter de Bruyn, translated by Peter Anthony, pp. 71–107;

“The Renunciation”/“Der Verzicht,” by Siegfried Lenz, translated by Stewart Spencer, pp. 109–117.

3. Take It Easy Kurzgeschichten, edited by Richard Fenzl (Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 2013), comprising:

“The Gauger Outwitted”/“Der übertölpelte Steuereintreiber,” by William Carleton, translated by Richard Fenzl, pp. 6–27;

“The Ball at the Mansion House”/“Der Ball im Haus des Lord Mayor,” by George and Weedon Grossmith, translated by Richard Fenzl, pp. 28–41;

“The Adventure of the Cantankerous Old Lady”/“Das Abenteuer der alten Rechthaberin,” by Grant Allen, translated by Richard Fenzl, pp. 42–93;

“The Model Millionaire”/“Der Modell-Millionär,” by Oscar Wilde, translated by Hella Leicht, pp. 94–109;

“A Lickpenny Lover”/“Ein knausriger Liebhaber,” by O. Henry, translated by Angela Uthe- Spencker, pp. 110–125;

“Dusk”/“Abenddämmerung,” by Saki, translated by Ulrich Friedrich Müller, pp. 126–139;

“The Split Sentence. Regina v. Strool”/“Das gespaltene Urteil. Regina Gegen Strool,” by A. P. Herbert, translated by Richard Fenzl, pp. 140–153;

“Vocation”/“Berufung,” by Evelyn Waugh, translated by Richard Fenzl, pp. 154–165;

”They Also Serve …”/“Sie dienen auch …,” by Mervyn Wall, translated by Richard Fenzl, pp. 166–185.

4. Germany and the Awful German Language/Deutschland und die schreckliche deutsche Sprache, by Mark Twain, edited and translated by Harald Raykowski (Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 2023), from which the first 54 pages were selected.