Members of Congress engage in numerous activities to care for their constituents on Capitol Hill. From introducing legislation to answering and following through on requests for services to voting on bills on the floor of Congress, legislators work to ensure that their constituents are well represented in government. Members of Congress also speak out publicly about issues that concern their constituents to ensure that they have a voice in the halls of power. This rhetorical form of representation is particularly important for members of underrepresented groups whose concerns have traditionally been ignored.

In fact, many elected officials identify the opportunity to provide a voice to groups who have been overlooked as an important part of their mission in government. In detailing his motivation to run for elected office, Yussef Salaam, one of the wrongly convicted Central Park Five, spoke about the importance of amplifying Black voices. In a July 2023 interview with the PBS Newshour Salaam proclaimed, “when others are marching in the streets, they need someone in the halls of power that can echo their voice, that can lift them up, that can carry them into those spaces, and be an advocate for them in the most powerful way.”Footnote 1 Yussef Salaam is not alone in this regard. Andrea Jenkins, a Black transwoman who served in the Minneapolis City Council spoke about the importance of giving Black people a voice in government. “It’s a mission…I really believe in the statement that representation matters. And then we need Black voices…”Footnote 2 Others, like Black Florida Congresswoman Sheila Cherfilus McCormick, have been explicit that one of their goals in Congress is to ensure that those outside of the seats of power have an opportunity to have their voices heard. In her biography page, she “vows to be a voice for the voiceless.”Footnote 3

A growing literature in political science is recognizing the importance of elected officials speaking out and amplifying the voices of marginalized groups in government (Gamble Reference Gamble2011, Evans and Clark Reference Evans and Clark2016, Gillion Reference Gillion2016, Gervais and Wilson 2017, Haines et al. Reference Haines, Mendelberg and Butler2019, Arora and Kim Reference Arora and Hannah J.2020, Bonilla and Tillery Reference Bonilla and Tillery2020, Hargrave and Langengen Reference Hargrave and Langengen2021, Russell Reference Russell2021, Dietrich and Hayes Reference Dietrich and Hayes2023, Vishwanath Reference Vishwanath2024). Much of this work has highlighted that descriptive representatives are more likely to advocate for their identity groups in their speech (Canon Reference Canon1999, Gershon Reference Gershon2008, Gamble Reference Gamble2011, Gervais and Wilson 2017). Other work has shown that the tenor and intensity with which descriptive representatives speak about issues pertaining to their identity are significantly different from non-descriptive representatives. (Dietrich et al. Reference Dietrich, Hayes and O’Brien2019, Hargrave and Langengen Reference Hargrave and Langengen2021, Hargrave and Blumenau Reference Hargrave and Blumenau2022).

Research on this form of representation, which has been labeled rhetorical representation, is in its nascent stages (Gillion Reference Gillion2016, Cormack Reference Cormack2018, Haines et al. Reference Haines, Mendelberg and Butler2019, Hargrave and Langengen Reference Hargrave and Langengen2021, Wӓckerle and Silva Reference Wӓckerle and Silva2023). This form of representation is becoming a more important part of legislators’ jobs as political polarization, filibusters, and divided government make it difficult for Congress to pass legislation. Rhetorical representation is likely even more significant for African Americans who not only encounter these hurdles in the legislative process but also face systematic racial barriers in Congress (Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003, Grose Reference Grose2011, Tyson Reference Tyson2016, Minta Reference Minta2021).

We are interested in how members of the U.S. House engage in Black rhetorical representation and whether this matters, especially now in the post-Obama age, where Black political power has continued to increase (Tate Reference Tate2010, Reference Tate2014). Scholars once called this period of expansion of Black political power, “post-racial” (Gillespie Reference Gillespie2010, McIlwain and Caliendo Reference McIlwain and Caliendo2011, Harris Reference Harris and Harris-Lacewell2012, Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Ford Dowe and Franklin2013). Barack Obama and other Black politicians seeking White support were to win their elections by downplaying racial concerns in their public outreach (Hamilton Reference Hamilton1977, Gillespie Reference Gillespie2010). While this deracialized approach increased Black representation in public office, it meant that Black people had few government officials speaking out on their behalf (Gillion Reference Gillion2016).

However, others recently contend that Obama’s election in 2008 triggered a racial backlash and George Floyd’s murder led to a national racial reckoning (Tesler Reference Tesler2016, Bunyasi and Smith Reference Bunyasi and Smith2019, Stout Reference Stout2020). This racial reckoning has polarized public opinion on racial issues. These divisions have created a sense of urgency for elected officials to speak out about Black political interests in a context where Black people are seeing a retrenchment in their political rights and prominent politicians work to combat what they see as a “woke” political agenda. Instead of avoiding racial topics, we argue that today’s politicians’ use of racial rhetorical outreach is central in combating systemic racial inequality.

While this increase in advocacy for Black political interests is certainly important to African Americans (Dietrich and Hayes Reference Dietrich and Hayes2023), it is likely equally as important how members speak out about racial issues. We draw an important and unexplored distinction in racial rhetorical outreach by disaggregating what we label as proactive racial rhetorical representation and reactive rhetorical representation. The latter is most likely a reaction to an event, high-profile news story or crises and frequently highlights traditional racial topics which are already in the public eye. This outreach may help elected officials build connections with their constituents (Eulau and Karp Reference Eulau and Karps1977, Chapman Sinclair Reference Sinclair-Chapman2002). In contrast, proactive racial rhetorical representation uses the elected official’s public platform to raise new racial issues, keep less salient racial topics on the agenda, and highlight the achievements of lesser-known African Americans in ways that are driven less by immediate public pressures. Proactive racial rhetorical representation may have the benefit of not only building trust with constituents but also potentially altering the policy landscape to be more inclusive of the interests of marginalized groups.

In this book, we engage in a deep dive into Black-oriented rhetorical representation by exploring U.S. House Representatives’ racial communication between 2015 and 2021. We use a wealth of data, including interviews with communications directors in Congress, hundreds of thousands of press releases and tweets, legislative activity including bill sponsorship, co-sponsorship, and committee hearing transcripts, survey data, and experimental analyses, to understand several important questions around racial rhetorical representation.

In particular, we explore the motivations of members of Congress to speak about Black political interests in government. We also delve into how elected officials may use rhetorical representation to alter the legislative landscape by speaking about lower salience topics, ensuring racial interests are accounted for in uncrystallized issues, and speaking to the diversity of interests within the Black community. Beyond exploring the policy impact of rhetorical representation, we also explore whether different types of racial public outreach can help build connections between elected officials and their constituents.

We consider this in two primary areas. First, can legislators build trust with their constituents by following through on their rhetoric with tangible legislative activity, such as bill sponsorship or co-sponsorship? Second, we explore which type of racial messaging matters to voters and why using experimental analysis, which includes both quantitative and qualitative responses. Through looking at racial rhetorical representation from different angles, circumstances, and through the lenses of both congressional offices and the voters, we hope to provide a complete analysis of the benefits of this form of representation.

What is Rhetorical Representation?

In her seminal book, The Concept of Representation, Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967) outlines four forms of political representation: formal, descriptive, substantive, and symbolic representation. While formal representation focuses on the norms and procedures that govern how representatives are selected, Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967) distinguishes the other forms of representation as “standing for” (descriptive and symbolic representation) and “acting for” (substantive representation).

According to Pitkin, descriptive and symbolic representation are both described as “standing for.” In terms of descriptive representation, it occurs when representatives mirror, in some way, the people they represent. Broadly defined, this can include a legislator and constituents sharing a profession, or what Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler (Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler2005: 408) refer to as functional representation. For instance, Montana U.S. Senator Jon Tester, a self-proclaimed third-generation farmer, descriptively represents farmers across his state. However, descriptive representation is most commonly used to describe the sharing of immutable characteristics, like race, ethnicity, and gender. For the purposes of our study, an African American who is represented by an African American legislator is descriptively represented.

Symbolic representation, according to Pitkin, occurs when representatives serve as symbols who “evoke feelings and attitudes” among the represented. “Symbolic representation is concerned not with who the representatives are or what they do, but how they are perceived and evaluated by those they represent” (Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler2005: 409). Many have interpreted Pitkin’s depiction of descriptive and symbolic representation as not requiring any action to be taken by the representative in order to be present.Footnote 4

In contrast, substantive representation occurs when representatives act “in the interests of the represented in a manner responsive to them” (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967: 209). Often, we think of this in terms of policy responsiveness (Miller and Stokes Reference Miller and Stokes1963), measured as the congruence between constituent interests and legislative actions, like voting and sponsoring legislation. For example, a legislator who votes for a restrictive abortion bill is taking action to substantively represent a pro-life constituent. However, others have argued for a more expansive understanding of substantive representation (Eulau and Karps Reference Eulau and Karps1977, Minta Reference Minta2011, Schulze Reference Schulze2013, Gamble Reference Gamble2011, Lowande et al. Reference Lowande, Ritchie and Lauterbach2019).

Eulau and Karp (Reference Eulau and Karps1977) argue that substantive representation can be broken down into four subcategories, which indicate some actions being taken on behalf of the constituents. In addition to policy responsiveness, they also consider substantive representation to include service responsiveness, allocation responsiveness, and symbolic responsiveness. Service responsiveness is centered on the ability of legislators to provide responsiveness to their constituents’ requests. Allocation responsiveness is tied to representatives bringing resources back to their district. Symbolic responsiveness, which is the most relevant to our focus, occurs when legislators make “public gestures of a sort that create a sense of trust and support in the relationship between representative and represented” (Eulau and Karps Reference Eulau and Karps1977: 241).

Symbolic responsiveness includes a variety of “public gestures” which entail actions like mirroring the attire of the constituents (Fenno Reference Fenno1977), posing with objects like a flag or bible (Callahan and Ledgerwood Reference Callahan and Ledgerwood2016), or actions like kneeling during the national anthem (Towler et al. Reference Towler, Crawford and Bennett2020). The public understands political issues and electoral choices, Edelman (Reference Edelman1964) contends, through political symbols (see also Sinclair Chapman Reference Sinclair-Chapman2018, Tate Reference Tate2003). Symbols help simplify issues, garner emotional support, and resonate with cultural values and beliefs. For Edelman (Reference Edelman1964), the use of symbols also gives the impression that the government is working on pressing issues of the day.

Speech is an important form of symbolic responsiveness (Dietrich and Hayes Reference Dietrich and Hayes2023). When this speech is centered on advancing the politics of a particular group, Haines et al. (Reference Haines, Mendelberg and Butler2019) label it as rhetorical representation. For our purposes, politicians provide rhetorical representation to African Americans when they discuss issues, legislation, and/or policies directly impacting Black communities, recognize African Americans, highlight their intentions to address problems faced by Black people, and/or outline their work on behalf of this group via a public forum. We argue that rhetorical representation is an especially significant subset of substantive representation.

Members of Congress have free rein to speak about whatever issues or topics they want. This allows for a greater variety of topics to be discussed via rhetorical representation. The ease with which legislators can put out a tweet or draft a press release means that elected officials can engage in rhetorical representation much more often than they can in bill introduction and in a less institutionally constrained way than with voting (Davidson et al. Reference Davidson, Oleszek, Lee and Schickler2019).

Elected officials can also move more quickly in their public outreach than they can in the legislative process. This leads rhetorical representation to be more flexible in response to moments of crises and allows legislators to immediately let their constituents know that they are thinking about them.

There is an important and growing body of work focused on studying Black-related speech, one form of symbolic responsiveness. Here, studies have looked at how representatives can use rhetoric to signal symbolic meaning to constituents. Of note is the work of Dietrich and Hayes (Reference Dietrich and Hayes2023), who convincingly show that legislators can be more effective advocates for different policies and build strong relationships with their constituents through the use of symbols in their rhetorical outreach. They find that Black House members are more likely than White House members to “use symbols of the African American struggle for civil rights when speaking on the House floor and that the correct application of these symbols can convey meaning to Black constituents” (Dietrich and Hayes Reference Dietrich and Hayes2023: 1369).

Much like Dietrich and Hayes (Reference Dietrich and Hayes2023), we too are interested in better understanding the differences in rhetorical strategies used by descriptive and non-descriptive representatives. However, we deviate from them in that we focus less on the use of symbolsFootnote 5 as the key divide between Black and non-Black legislators. Instead, we are more interested in the differences in motivations to speak out as distinguishing descriptive and non-descriptive representatives. We contend that legislators who view race as a key part of their legislative identity will be more proactive in their outreach. In doing so, they will speak about a broader set of topics, expend more effort to keep issues on the agenda, and ensure that race is considered in new policies. This proactive outreach not only helps connect legislators to their constituents, but we argue it also has important policy implications. In contrast, legislators who want to appeal to Black voters but do not see race as a core part of their identity will speak about race differently. These elected officials will frequently speak about well-known racial issues and speak on racial topics when there is public pressure to do so. This different motivation to speak out should lead to different policy implications, as well as provide a lesser ability to connect with constituents.

Proactive and Reactive Racial Representation

An important contribution of our research is moving beyond the dichotomy of racial substantive outreach and focusing on how the different motivations to engage in racial rhetorical representation lead to different types of responsiveness. Those who see addressing racial inequality as a primary part of their legislative identity are more intentional in their engagement around race in their public outreach. This intentionality is tied to proactive rhetorical representation. Elected officials engage in proactive rhetorical representation when they use their public platform to actively broaden the boundaries of racial discussions, keep racial issues on the agenda when they are no longer topical, and speak about racial issues in an unprompted manner which are not driven by immediate public pressures. We believe that this type of rhetorical representation has the greatest ability to both advance the policy interests of African Americans and improve voters’ trust and approval for elected officials.

In contrast, elected officials who want to target key constituencies but do not see issues pertaining to race as being a core part of their legislative brand may engage in reactive rhetorical representation. Reactive rhetorical representation occurs when elected officials speak about race using topics that are already in the public discourse and generally in response to immediate external pressures. While this form of outreach supports marginalized groups by reinforcing existing demands, it does less than proactive racial rhetorical representation to actively change the public discourse around race. As a result, this type of rhetorical representation may be effective in building connections between elected officials and the targeted groups, but is less likely to substantively alter the policy environment.

There are many characteristics that distinguish proactive and reactive outreach. In this section, we discuss key areas where these two forms of targeted outreach may differ. The first way that elected officials engage in proactive rhetorical representation is by broadening the scope of racial topics in American political discourse. This can occur in two ways. Elected officials can highlight racial concerns in new areas that are not traditionally tied to race. These issues can be longstanding or novel. For example, U.S. House Representative Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) engaged in proactive rhetorical representation when she put out several tweetsFootnote 6 and press releasesFootnote 7 highlighting the role of public transportation access to communities of color. Similarly, U.S. House Representatives Lauren Underwood (D-IL) and Alma Adams (D-NC) engaged in this form of outreach when they used their public platform to highlight racial discrimination in the maternal care of Black women.Footnote 8 In both of these examples, rhetorical representation is used to highlight the many different ways that race intersects with everyday activities to limit opportunities for people of color. In doing so, elected officials who engage in proactive racial rhetorical representation help broaden the racial discourse by addressing previously overlooked forms of racial inequality. They also highlight a problem which could potentially mobilize legislative solutions.

Along the same lines, elected officials engage in proactive racial rhetorical representation when they speak about lower-profile racial topics. Despite the lack of public attention on the issue, members of Congress highlight it in the hope of raising awareness and expanding the public agenda. Legislators feel little pressure to speak on these issues because if they said nothing, the public would likely not notice their absence. These could be topics which are well established as being tied to racial inequality, but because of their controversial nature or their perceived lack of broad interest, are generally not discussed by elected officials. Examples of this may be discussions of topics around reparations for slavery,Footnote 9 Black hair care,Footnote 10 or lesser-known Black public figures.Footnote 11

When speaking to communications directors in Black House offices, many explicitly discussed how a primary aim of theirs is to continually speak on issues important to the Black community that regularly go unheard and unrecognized. Given that these issues are rarely in the public eye, speaking out about them requires intentional effort by the legislators to continue to shed light on these topics.

This intentionality is also present in legislators’ willingness to continue to talk about high-profile racial topics even when they fade from popular discourse. This is another hallmark of proactive rhetorical representation. For example, in April of 2014, a group of Black girls was kidnapped from the Government Girls Secondary School in the Borno State of Nigeria by Boko Haram, a United States-designated terrorist group. This event led to a viral hashtag #Bringbackourgirls which was tweeted from several high-profile figures like Michelle Obama, Mary J. Blige, and Anne Hathaway (Parkinson and Hinshaw Reference Parkinson and Hinshaw2021). Multiple members of Congress used the hashtag in their Tweets. #Bringbackourgirls was one of the top ten most popular hashtags of 2014. However, by 2015, interest in the issue largely faded.Footnote 12 Although the girls who were kidnapped by Boko Haram were not brought home, the public had shifted its attention to other issues.

One member of Congress, Democratic Congresswoman Frederica Wilson (FL-24), engaged in proactive rhetorical representation when she continued to speak about the issue even when it was no longer a high-profile topic. She continued to give speeches about the topic on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives, she tweeted the hashtag daily for multiple years, and she organized “wear something red Wednesdays” to bring attention to the plight of the girls kidnapped by Boko Haram. In a speech on the floor of Congress, she noted months after the hashtag went viral, “While talking about the girls may no longer be trendy, it is more important than ever to bring them home…the time is now to keep pressure on the Nigerian government. We must tweet with the fervent passion that extends beyond the glamour of a breaking news story. We cannot slow down, we cannot lose momentum, we cannot rest until our girls are home.”Footnote 13 Representative Wilson used proactive rhetorical advocacy to fight for funding for combating Boko Haram and for marshaling more resources to bring the girls of the school in Chibok home. This action to keep talking about a once high-profile racial topic when public interest has faded requires attentiveness and a personal dedication to the issue, which is consistent with proactive rhetorical representation.

As a result, legislators engage in proactive rhetorical outreach when they speak out on an issue regularly, even when there is no external event prompting the discussion, like a mass shooting or political party leaders providing rhetorical support through pre-written statements. These unprompted discussions signal to the electorate that the topic, in this case Black-oriented issues, is always top of mind to the elected official. Elected officials who engage in proactive rhetorical representation do not need an occasion or headline to speak out in support of African Americans; they do so on a regular basis, regardless of the external circumstances. Overall, proactive racial rhetorical outreach expands the racial issue agenda, not only in the kinds of issues that are raised but also by the continual and persistent outreach on the issue. This has the potential to both expand substantive representation in terms of advancing policy interests and symbolic responsiveness in terms of creating a sense of trust between the elected official and the constituent.

While the above examples highlight forms of proactive rhetorical representation, reactive rhetorical representation will likely be the most common form of racial outreach. We suspect that key events, protests, or holidays will prompt more elected officials to engage in Black-related rhetorical representation because silence in these areas may be more costly than putting out a statement. For example, many elected officials will put out statements in recognition of Black History Month or condemnations of White Supremacy following the Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville in 2017. The former is nationally recognized, and it would be expected that attentive elected officials would highlight some aspect of Black history during the month of February. Such outreach would not be that risky, nor would it take incredible foresight to speak out, yet it would demonstrate an attentiveness to Black voters, which could be electorally beneficial and demonstrate symbolic responsiveness. The latter, too, would be both reactive and common. In large part, because there are few electoral costs to condemn White supremacy, given Americans’ disdain for overt racism (Wetts and Willer Reference Wetts and Willer2022). Moreover, the rally of White supremacists and President Trump’s ensuing comments about good people being on both sides would push elected officials to take a stand to show they are paying attention and to disassociate from such politically unpopular rhetoric. In both cases, elected officials engage in reactive rhetorical representation because their racially centered outreach was prompted by external circumstances.

Responsiveness to high-profile issues is a trademark of reactive rhetorical representation. We define high-profile issues as those that are clearly on the public’s agenda and getting regular public and media attention. If the legislator never spoke out on the issue, it would still be salient in the public realm. Moreover, in some cases, if a legislator does not speak out on a high-profile issue, they may face negative electoral consequences (Milita et al. Reference Milita, Ryan and Simas2014, Gillion Reference Gillion2016, Gause Reference Gause2022). During our interviews with communications directors, many said that when it became clear that their constituents cared about something or were being impacted by something, they felt compelled to issue a public statement. A safe way that elected officials can periodically shore up support from key constituencies is to speak about high-profile racial topics. Issues like voting rights, condemning White Supremacy, and, more recently, criminal justice reform are issues that have a profound and disproportionate impact on African Americans. The implications of discussing these issues are well known. As a result, legislators can appeal to African Americans using these topics and be less concerned about an unexpected backlash.Footnote 14

Moreover, consistent examples of these forms of discrimination are often covered by the media, which cries out for some form of action from elected officials who want to demonstrate their value to Black voters. The perpetual nature of these social problems and the high level of coverage they receive make discussions about these topics a common form of race-based outreach. Elected officials who engage in reactive rhetorical representation still work to appeal and advance the goals of Black people; they just do so in a narrower manner, which is consistent with a well-known racial script. Overall, reactive rhetorical outreach reiterates the racial issue agenda by echoing traditional and salient issues and does so most when circumstances prompt their discussion. While reactive rhetorical representation can put additional pressure on existing policy solutions to be enacted and build connections with constituents, it is less likely to have the broader impacts of proactive rhetorical representation.

The Link Between Descriptive Representation and Proactive Racial Rhetorical Representation

We anticipate that Black legislators will be more likely than non-Black legislators to engage in proactive racial rhetorical representation for three primary reasons. First, Black legislators hold distinct electoral incentives that may encourage them to speak out on Black issues more than other legislators. Black constituents have been and continue to be a uniquely important sub-constituency for Black legislators’ reelection efforts. Whether from a majority-Black district or, as is increasingly the case, from a non-majority–minority district, Black legislators uniquely rely on Black constituents for their reelection. For instance, Grose (Reference Grose2011) shows that Black Democratic members of Congress from districts in which African Americans make up 25 to 50 percent of the total population are more likely to rely on Black voters for reelection than White Democratic voters. Black elected officials’ unique reliance on the Black population to win reelection may motivate them to continuously find ways to speak out for the political interests of their co-racial constituents.

Second, Black legislators may engage in more proactive racial rhetorical outreach than others due to their identity. As Black members of society, Black legislators have direct experience with racism and marginalization. Scholars have argued that Black legislators bring these distinct perspectives to Congress, shaping deliberations and the issues considered within the institution (Cannon Reference Canon1999, Gamble Reference Gamble2011, Minta Reference Minta2011). Mansbridge (Reference Mansbridge1999: 647) argues that Black legislators have a “particular sensibility, created by experience,” that enables them to identify Black interests on “uncrystallized issues,” or issues where Black interests have not yet been fully formed and publicly recognized.

In addition to their personal experiences, the personal connections Black legislators have with the Black community enable them to better identify important issues facing Black people, which are overlooked by others. As members of the Black community themselves, their everyday interactions with Black family members, fellow parishioners at Black churches, fellow students and alumni of Historically Black Colleges and Universities, and even their Facebook feeds, provide them a greater connectedness to other Black people. Moreover, Grose (Reference Grose2011) shows that upon being elected to Congress, Black legislators are more likely to hire Black staffers and place their district offices closer to heavily populated Black areas. These relationships should provide a greater connectedness to the Black community, thus shaping their understanding of Black issues that are outside of the mainstream media. This greater awareness, in combination with stronger personal ties, should lead to stronger levels of advocacy for a greater variety of Black-related issues.

Black legislators also likely have a strong sense of group identity with the broader Black community. Due to their shared history and experiences with racism and oppression, some have argued that Black Americans hold a strong sense of linked fate, the belief that one’s fate is intrinsically connected to the fate of the entire community (Tate Reference Tate1994, Dawson Reference Dawson1995). For Black legislators, linked fate produces a feeling of added responsibility to represent Black Americans nationwide. As Rep. Louis Stokes said, “In addition to representing our individual districts, we had to assume the onerous burden of acting as congressman-at-large for unrepresented people around America” (Fenno Reference Fenno2003: 62). Studies have pointed to linked fate as at least part of the explanation as to why Black legislators are distinct in their representation of Black Americans (Tate Reference Tate2003, Gamble Reference Gamble2011, Minta Reference Minta2011, Broockman Reference Broockman2013). Others, however, have demonstrated that social pressure is also at play (White and Laird Reference White and Laird2020). While Black Americans hold an array of policy opinions and ideological perspectives, they maintain a fairly strong political unity. White and Laird (Reference White and Laird2020) show that an important reason for this unity is the norm of group solidarity, which is prioritized by Black Americans. As such, whether it be group identity or the norm of group solidarity, Black legislators’ belonging to the larger Black community may enhance their intentionality to engage in rhetorical outreach to Black Americans.

Lastly, Black legislators may rely more on proactive racial rhetorical outreach than other legislators due to the distinct barriers they face within Congress. While it’s difficult to get much of anything done in Congress these days, this is particularly true for Black legislators. In addition to the forces of polarization and insecure majorities (Lee Reference Lee, Kim and Scheufele2016), Black legislators face additional racialized barriers. Though the number of Black legislators has grown significantly over the last few decades, they remain minorities within Congress. In an institution governed by majority-rules, this can place significant constraints on their influence. However, even when the Democratic Party is in the majority, Black legislators still find their influence stymied. Studies have shown that despite the growing concordance between the CBC and the Democratic Party (Tate Reference Tate2014), the Democratic Party has been hesitant to include racialized issues on their agenda (Frymer Reference Frymer2014). Moreover, policies associated with Black politicians are often viewed as “ideologically radical” (Peay Reference Peay2021) and have the potential to be racialized (Tesler Reference Tesler2016), further inhibiting their advancement.

Black legislators also face racial prejudice and discrimination within Congress (Polsby Reference Polsby1968, Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003, King and Smith Reference King and Smith2005, Tyson Reference Tyson2016). For instance, in 1993, U.S. Senator Carol Moseley-Braun (D-IL), the only Black legislator in the United States Senate at the time, recalled an interaction with Sen. Jesse Helms (R-NC). Upon entering the elevator she was standing in, he began singing “Dixie.” He then turned to Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-UT) and said, “I’m going to make her cry. I’m going to sing ‘Dixie’ until she cries.”Footnote 15 Rep. Barbara LeeFootnote 16 and Sen. Tim ScottFootnote 17 have both recounted individual experiences of being denied access to certain members-only areas in the Capitol. In the summer of 2023, GOP Rep. Eli Crane referred to Black people as “colored people” during a speech on the House floor.Footnote 18 In fact, in early 2024, the New York Times published an article outlining the frequency at which Republican members of the House and Senate were engaging in “bigoted attacks” on people of color, including legislators like Rep. Cori Bush.Footnote 19

Beyond these individual acts of prejudice, scholars have pointed to institutionalized marginalization within Congress. For instance, studies have shown that Black legislators have been put on less prestigious committees than White legislators (Tate Reference Tate2003, Griffin and Keane Reference Griffin and Keane2011, Rocca et al. Reference Rocca, Sanchez and Morin2011) and committees whose jurisdictions do not overlap with their personal or constituents’ interests.Footnote 20 Additionally, Hawkesworth (Reference Hawkesworth2003) shows that congresswomen of color are systematically silenced and dismissed within Congress. Moreover, Peay (Reference Peay2021) shows that Black sponsored bills are disproportionately winnowed in congressional committees. As such, traditional avenues of policy influence are not always available to Black lawmakers. This forces them to rely on unique strategies to overcome these distinct barriers (Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003, Tyson Reference Tyson2016).

One way Black legislators can circumvent some of these constraints, while still trying to attain influence in policymaking, is through proactive racial rhetorical outreach. Black legislators, like all legislators, have a great deal of discretion in the statements they make to the public. When they are unable to gain traction on a policy priority within the normal legislative process, they can turn to rhetorical outreach in an effort to advance their priorities. One way they can do this is by continuously issuing public statements on an issue to try to get it more attention so that it becomes difficult for Congress to ignore it.

Racial rhetorical outreach by Black legislators can also alter the way an issue gets discussed. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Black legislators regularly brought up inequality in access to health care and the disparate impact of the pandemic on Black and Brown communities. This added perspective shapes the way the issue gets discussed in the future. Moreover, Black legislators are able to use their communications as a way to signal to key players, like party leaders, interest groups and advocacy organizations, and other legislators, that they are ready and willing to work on their policy priorities. Repeatedly issuing statements on a particular policy may help better position that legislator to be included in the legislative process when the opportunity arises to advance legislation in that policy area. Issuing statements can also signal to other legislators and organizations that you’re ready and willing to work on policy in this area. This may help build policy coalitions and improve the legislative effectiveness of the politician.

Why Racial Rhetorical Representation is Important for American Politics

While there are unique reasons for descriptive representatives to engage in proactive racial rhetorical outreach, it is important to discuss the value that such outreach produces in the legislative process and in connecting members of Congress with their constituents. The American federal legislative process is slow and often filled with what seems like insurmountable hurdles (Sinclair Reference Sinclair2016). A casual political observer may look at elected officials and believe that they are doing little to address the most pressing problems in society. This disconnect between social problems and public policy has the potential to have a demoralizing effect on the population and decrease trust in our political institutions (Sulkin et al Reference Sulkin, Paul and Kaye2015).

This is a particular concern for African Americans who, even in the best of times for their racial group, face significant political barriers (Wallace et al. Reference Walton, Smith and Wallace2017). The lack of a federal legislative response in the face of constant reminders of police violence through videos shot on cell phones and body cameras, attacks on racial history lessons in education, and growing wealth and healthcare disparities among Black and White people have highlighted the pressing need for legislative solutions. The perception that politicians are doing very little as new racial problems appear and old challenges resurface could lead to a sense of powerlessness for African Americans.

We believe that rhetorical representation may have the power to address concerns of unresponsiveness from our elected officials. African Americans have long been cognizant of the obstacles that their group faces in American political institutions (Wallace et al. Reference Walton, Smith and Wallace2017). They also have a long history of being ignored by both major political parties and even by elected officials who share their race (Gillespie Reference Gillespie2010, Frymer Reference Frymer2011, Wallace et al. Reference Walton, Smith and Wallace2017). To combat these feelings of being overlooked, elected officials can use racial rhetorical representation to demonstrate that they are working on behalf of African Americans, even if the system overall is unresponsive. The presence of a constant ally may serve to keep African Americans engaged in the political process.

The ability of public outreach to build trust and connections with constituents is a valuable byproduct of rhetorical representation. In fact, Dietrich and Hayes (Reference Dietrich and Hayes2023) demonstrate that elected officials who speak more about racial issues and tie these issues to prominent civil rights leaders tend to receive higher levels of approval and motivate political participation. The communicative aspect of rhetorical representation makes it easier for individuals to assess how concerned their representative is about their group in ways that other forms of substantive representation generally do not. For example, while a representative’s voting record or policy proposals are publicly available, voters are often forced to seek out this information, which can be time-consuming. Additionally, other substantive actions, like coalition building and working with community leaders, are even less publicly visible. Rhetorical representation removes the need for individuals to seek out what their representatives are doing for their group, and instead provides a shortcut through which politicians publicly highlight their priorities and work on behalf of these individuals.

In addition to building connections between representatives and constituents, we contend that racial rhetorical representation also has positive policy implications for underrepresented groups. As African Americans face consistent barriers to normalcy, having political actors use their public platform to frame the debates in a way that highlights the needs of African Americans and keeps pressing racial issues on the agenda increases the likelihood that federal legislation may follow.

Moreover, even if unsuccessful at the federal level, rhetorical representation may set the guidelines for change at the local level. For example, while there was not a successful federal legislative response to protests around George Floyd in the Summer of 2020, many states and cities adopted the policies advocated by members of Congress, including the banning of chokeholds, no-knock warrants, racial sensitivity training for police officers, and changes in police hiring practices.Footnote 21 By framing the debate and providing solutions to social problems that African Americans encounter, rhetorical representation can help make tangible changes to a political landscape that appears to be growing increasingly hostile to Black people’s political interests.

Measuring The Causes and Consequences of Rhetorical Representation Through Interviews, Machine Learning of Press Releases and Tweets, and Survey Experiments

Interviews With Communication Directors

Measuring the potential impact of rhetorical representation on policy and symbolic responsiveness requires a wide variety of data sources. First, it is important to learn from the communications directors themselves how they decide to use their public platform to alter the policy debate and/ or build connections with constituents. This interview data is instrumental in the development of our theory around the links between identity and rhetorical outreach.

In this spirit, we interviewed 29 communications directors in the 118th Congress (2023–2025). We spoke to communications directors from nine Black Democratic Congresswomen, four Black Democratic Congressmen, seven Latino Democrats, two Latina Democrats, three White Democratic Congressmen, two White Democratic Congresswomen, and two Republican Congressmen. Given that we are interested in the link between descriptive and racially oriented representation, we collected an oversample of communication directors from Black legislators’ offices. Our thirteen communication directors in Black representatives’ offices represent almost a quarter (22.5%) of all Black representatives’ legislative offices. Since communications directors are largely responsible for the messaging coming out of legislative offices, their perspectives shed valuable insight into the decision-making behind legislators’ use of proactive or reactive racial rhetorical outreach (See data and methods appendix for more information about our sampling strategies and questions used in the interviews).

Twitter and Press Release Data

Beyond what communications directors tell us, a key source of understanding whether elected officials engage in rhetorical representation and whether they do so proactively or reactively is their actual communication. There are a variety of public mediums through which elected officials can engage in rhetorical representation, including speeches, social media, community meetings, etc. We focus on two forms of communication: press releases and tweets from members of the U.S. House of Representatives. We believe that the combinations of these forms of outreach will best approximate rhetorical representation for several reasons. First, both forms of outreach provide a means through which legislators can reach voters and colleagues (Grimmer Reference Grimmer2013). Second, research shows that the media often gets their news stories from the press releases or tweets of political elites (Bennett Reference Bennett1990, Schaffner Reference Schaffner2006, Broersma and Graham 2012, Grimmer Reference Grimmer2013, Bane Reference Bane2019). As a result, the messages disseminated by members of Congress are not only available to those who search the member’s website or follow them on social media, but also to those who follow political news.

Finally, by using two forms of outreach, which tend to have different targeted audiences, we gain broader insight into how members of Congress communicate. Given that press releases are most effective when picked up by media organizations, members of Congress tend to take a less provocative approach in their outreach. In our interviews with communications directors, many emphasized that press releases were largely aimed at reporters and were reserved for larger pieces of news. When a legislator sponsored a bill, was able to bring something back to their district, or was responding to a major news story, their office tended to issue press releases. By incentivizing cautiousness, elected officials may speak less about particular issues and approach group-based appeals a little differently in their press releases than they would with other forms of communication.

In contrast, the communications directors we spoke to emphasized that those on Twitter tended to be more politically active and partisan. Sometimes what they posted on Twitter would be directed at interest groups and advocacy organizations. Other times, Twitter was used as a way to more quickly get out messages and respond to the day’s news cycle. Twitter tends to reward more extreme political outreach and thus incentivizes a different type of political rhetoric (Pew Research). Moreover, Twitter is particularly meaningful to African Americans as a tool to organize and voice their concerns to elected officials (Sharma Reference Sharma2013). Using communication approaches that reward different styles of outreach provides a more comprehensive view of how members of Congress engage in rhetorical representation. It also provides more confidence that our findings would hold across different communication channels and allows us to comparatively explore how racial rhetorical representation may differ on social media and traditional communication approaches.

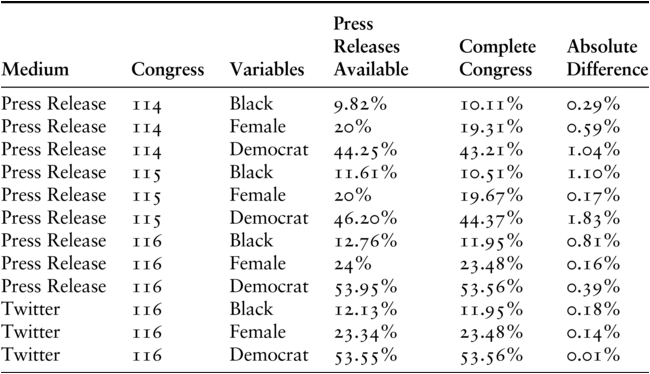

We draw from two separate data sets to determine levels of Black outreach in Congress. This includes almost the complete universe of press releases for members of the U.S. House of Representatives in the 114th (2015–2017), 115th (2017–2019), and 116th (2019–2021) US Congresses. This data set includes 204,806 individual press releases from 401 members in the 114th Congress, 403 members in the 115th Congress, and 407 members in the 116th Congress. Our dataset represents over 92 percent of the membership in each of the Congresses we examine. The only representatives we were unable to obtain data for were those whose websites did not have an accessible press release section or who retired, and whose websites could not be opened with the internet archive. The representatives from whom we could not get information do not significantly differ from the whole congress in their partisanship, gender, or race (see Table 1.1). Thus, we do not expect that the exclusion of these individuals will systematically bias our results.

| Medium | Congress | Variables | Press Releases Available | Complete Congress | Absolute Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Press Release | 114 | Black | 9.82% | 10.11% | 0.29% |

| Press Release | 114 | Female | 20% | 19.31% | 0.59% |

| Press Release | 114 | Democrat | 44.25% | 43.21% | 1.04% |

| Press Release | 115 | Black | 11.61% | 10.51% | 1.10% |

| Press Release | 115 | Female | 20% | 19.67% | 0.17% |

| Press Release | 115 | Democrat | 46.20% | 44.37% | 1.83% |

| Press Release | 116 | Black | 12.76% | 11.95% | 0.81% |

| Press Release | 116 | Female | 24% | 23.48% | 0.16% |

| Press Release | 116 | Democrat | 53.95% | 53.56% | 0.39% |

| 116 | Black | 12.13% | 11.95% | 0.18% | |

| 116 | Female | 23.34% | 23.48% | 0.14% | |

| 116 | Democrat | 53.55% | 53.56% | 0.01% |

* Significant at .05 based on Two-Sample T-Test

Our Twitter data are confined to the 116th Congress (2019–2021). This data set includes 601,303 individual tweets from 411 members of the 116th U.S. House of Representatives. This includes the universe of members of Congress who put out a tweet during our period of interest (January 3, 2019, and January 2, 2021) and/or had an active Twitter account. However, it is possible that deleted tweets were not included in this analysis.Footnote 22

Measuring Racial Outreach

We use press releases and social media posts to determine levels of Black-related rhetorical representation. We consider Black-oriented rhetorical representation to be any discussion of an issue, topic, public figure, event, institution, or organization that is explicitly tied to Black political interests. Additionally, these discussions must frame Black political interests in a positive or supportive manner. There is no established measure of Black-oriented outreach, so we create our own codebook for Black political appeals by using a comprehensive review of both our own communication data (i.e., press releases and tweets) and the work of scholars in this area (Metz and Tate Reference Metz and Tate1995, Reeves Reference Reeves1997, Grose Reference Grose2011, McIlwain and Caliendo Reference McIlwain and Caliendo2011, Minta Reference Minta2011, Gillespie Reference Gillespie2010, Reference Gillespie2012, Stout Reference Stout2015, Wamble Reference Wamble2018, Arora Reference Arora2019, Crowder 2021, Stephens-Dougan Reference Stephens-Dougan2020, Reference Stephens-Dougan2021, Dietrich and Hayes Reference Dietrich and Hayes2023).

We supplement this review with an additional audit of Black-centered organizations’ websites. This review allowed us to broaden the number of potential topics being covered and ensure that we would not miss key issues. For example, there are several names tied to Black Lives Matter that received low coverage in the media, and several Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) that may not be recognizable to the average coder. By including each of the names associated with Black Lives Matter, through a review of the organization’s website along with databases tied to political protest like countlove.org and ephrame.com, and each HBCU, we cast a wider net to ensure we are not missing lower-profile cases of Black-related outreach.

Finally, we coded all bill summaries that were issued in the U.S. House of Representatives during our period of interest (2015–2021), which recognized an individual or proposed naming a place after an individual. We then searched Google.com for biographies and photos of each individual named in the summary. While this is an inexact science, we were able to find several individuals who are African American who would not have been included in our initial coding scheme. For example, Kira Johnson was a Black woman who died during childbirth due to prejudiced health care. In recognition of her and all Black mothers who face greater risks during pregnancy, Alma Adams (D-NC) introduced the Kira Johnson Act. While not initially on our coding scheme, the inclusion of this name and people like her increases the probability that a Tweet or press release highlighting this legislation would be appropriately coded as appealing to African Americans.

From our review of research and an exploratory coding analysis of the data that we had available, we created a coding scheme that highlighted fifteen broad themes and provided coders over 500 words and names centered on Black political outreach to reference if they were unsure (see appendix for complete coding scheme). By creating this coding dictionary, we hope to have developed the broadest and most detailed measure of Black political outreach available. We also hope that this comprehensive list of racial outreach can be used as a guide for further research on Black appeals.Footnote 23

We focus on explicit Black outreach because press releases and tweets around these topics demonstrate the most direct and recognizable outreach to African Americans. Moreover, race is a central part of American politics and spillovers into many different domains such as healthcare (Tesler Reference Tesler2016), welfare (Gilens Reference Gilens2001), crime (Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001), and gun control (Filindra and Kaplan 2015). To ensure that the appeals we focus on are made directly to African Americans and are not simply racially tinged, we confine our coding to issues explicitly tied to race. We are not interested in racial outreach, which is meant to harm Black political interests. For example, several posts on Twitter following the murder of George Floyd accused Black Lives Matter of being a violent movement that encouraged rioting. While these forms of outreach make race a salient issue, they do so in a way that harms African Americans. Given that racial rhetorical representation is not simply discussing race but means doing so in a way that advances Black politics, we do not code attacks on African Americans as being forms of rhetorical representation in our analysis.

Given the large number of press releases and tweets, it would be extremely time-consuming and cumbersome to code each one individually. To circumvent this problem, we use a combination of hand-coding and computer-assisted content coding using RTextTools (Jurka et al. 2012). While much has been written about machine learning content analysis (see Grimmer and Stewart Reference Grimmer and Stewart2013, Barbera et al. Reference Barbera, Boydstun, Linn, McMahon and Nagler2016), recent research demonstrates that it performs better than dictionary coding approaches and with the proper environment, as well as manual coding (Barbera et al. Reference Barbera, Boydstun, Linn, McMahon and Nagler2016). Through an iterative process of hand-coding and machine learning, we were able to identify racial outreach with a high degree of intercoder reliability among the hundreds of thousands of press releases and tweets we analyzed. See the data and methods appendix for more details about the process we used to identify and validate our measures of Black-oriented outreach.

Survey Experimental Data

In addition to understanding whether there are differences in rhetorical representation between Black and non-Black elected officials and whether these representatives differ in their use of proactive and reactive forms of rhetorical representation, we are also interested in the electorate’s response to this form of racialized outreach. This is vital to understanding the efficacy of proactive and reactive rhetorical representation in building connections with constituents. To better understand whether rhetorical representation matters to the public, we use an experiment conducted via ProlificFootnote 24 on a sample of 600 Black and 600 White respondents. In these experiments, we present fictional press releases from a hypothetical Black and White member of Congress that either discusses a non-liberal racial issue, a low-profile (i.e., proactive) racial issue, or a high-profile (i.e., reactive) racial issue. We use the experiment to examine both quantitative and qualitative reactions to candidates who engage in different forms of representation. This allows us to not only assess whether rhetorical representation from descriptive and non-descriptive representatives matters, but also explore why potential voters respond to this form of outreach.

By using multiple data sources, which include information from communications directors, legislators’ official communications, and quantitative and qualitative responses from everyday citizens, we provide a holistic understanding of the crafting of rhetorical outreach and why it matters. The triangulation of different data sources and our mixed methods approach allows us to empirically investigate the many different sides of rhetorical representation.

Chapter Outline

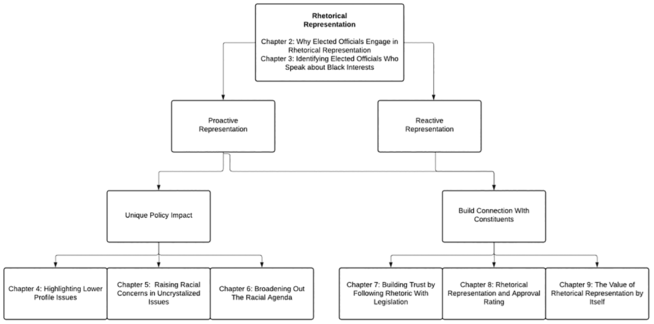

The book is divided into three main sections with the goal of providing readers with a complete understanding of rhetorical representation by using the case study of Black politics. The logic of the chapters is outlined in Figure 1.1. In Chapters 2 and 3, we explore who provides rhetorical representation and why members of Congress engage in this form of outreach.

Figure 1.1 Outline of the Plan of the Book

Figure 1.1Long description

The flowchart begins with an overview, as to why elected officials engage in rhetorical representation in Chapter 2, and identifying elected officials who speak about Black interests in Chapter 3. It then branches into Proactive Representation to Unique Policy Impact, which is further divided into three chapters, Chapter 4 Highlighting Lower Profile Issues, Chapter 5 Raising Racial Concerns in Uncrystallized Issues, and Chapter 6 Broadening Out The Racial Agenda. Reactive Representation leads to Build Connection With Constituents, which is also divided into three chapters, Chapter 7 Building Trust by Following Rhetoric With Legislation, Chapter 8 Rhetorical Representation and Approval Rating, and Chapter 9 The Value of Rhetorical Representation by Itself.

In Chapter 2, we discuss the rhetorical strategies of congressional offices based on our interviews with twenty-nine communications directors in the U.S. House of Representatives. Our interviews reveal that legislators frequently rely on proactive rhetorical outreach when speaking out on issues that are central to their identity or brand as a legislator. In these instances, legislators use proactive rhetorical representation to advance policy debates and demonstrate their expertise on these issues to build connections with their constituents.

In this section, we also explore who provides Black-oriented racial rhetorical representation. This allows us to explore how a racial identity interacts with other key descriptors like gender, age, district composition, and partisanship to shape levels of racial rhetorical outreach. Chapters 2 and 3 provide an overview of the motivations for elected officials to engage in rhetorical representation and provide information on which elected officials use their public platform to advance Black-oriented issues.

In Chapters 4, 5, and 6, we identify the elected officials who are most likely to use their public platform to advance the policy interests of Black people through the use of proactive rhetorical representation. In doing so, we identify three key areas in which speech can alter policy discussions. First, we explore whether Black and non-Black elected officials’ rhetorical representation differs in the proportion of high-profile and low-profile outreach. The former represents a reactive form of outreach, while the latter is indicative of proactive racial representation. Using an analysis of over 500 keywords and a case study of the Black Lives Matter movement, we demonstrate that African Americans are the most likely to use their public platform to shed light on lower-profile topics and to keep issues on the agenda when public interest has faded.

The second way in which proactive rhetorical representation improves the legislative landscape for Black people is ensuring that Black political interests are accounted for in emerging policies. To that end, we examine whether Black and non-Black elected officials differ in their discussion of what Mansbridge (Reference Mansbridge1999) describes as uncrystallized issues. Mansbridge (Reference Mansbridge1999) argues that uncrystallized political issues are those that have not been on the political agenda for very long, and political actors have not yet taken public stances. While Mansbridge’s (Reference Mansbridge1999) hypothesis was theoretical, in Chapter 5, we empirically demonstrate that Black elected officials are the most likely to speak out on behalf of co-racial individuals around uncrystallized issues using an analysis of racialized press releases and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The final way in which we believe that proactive rhetorical representation may alter the policy landscape is through the discussion of the multiple challenges and opportunities that different groups face in society. We argue that African American legislators’ ability to highlight issues of concern to a diverse Black community broadens the recognition of social problems and solutions for this racial group. In doing so, legislators who use proactive rhetorical representation ensure that a broader set of racial interests is in the public domain. In Chapter 6, we use keyword-assisted topic modeling to identify over twenty different topics in both press releases and tweets. We then explore whether Black elected officials differ from others in the number of topics they discuss in their rhetorical outreach. Similar to other areas of proactive rhetorical representation, we find that descriptive representatives speak about a broader set of racial topics than others.

Chapters 7, 8, and 9 explore the symbolic responsiveness aspects of proactive and reactive rhetorical representation. In particular, we explore whether different forms of rhetorical representation can help build trust and approval with constituents. While we think that both forms of rhetorical representation can provide a sense of symbolic responsiveness, it is important to explore whether one is a more effective way to build connections between elected officials and those whom they represent.

The first way that elected officials can use rhetorical representation to build trust is to follow their rhetoric with policy actions. Rhetorical representation can be a powerful tool to inform supporters of the member of Congress’ intentions about advancing racial progress in government if it is tied to actual behavior. If this is the case, it may be a useful tool to build trust between legislators and constituents. In Chapter 7, we assess whether the use of proactive or reactive rhetorical representation is correlated with a host of legislative activities, including bill sponsorship and co-sponsorship, voting scores, and discussions in committee hearings.

In Chapters 8 and 9, we shift from the trust-building function of public outreach to assess whether proactive and/or reactive rhetorical representation can improve constituents’ approval of legislators. In Chapter 8, we use an experiment that presents a large sample of Black and White respondents with a hypothetical press release that discusses a non-racial liberal issue (climate change), a high-profile racial issue (police reform), and a low-profile racial issue (manufacturing employment discrimination). We then ask respondents whether the press release they received improved their perceptions of the elected official and to explain their reasoning.

Chapter 9 explores whether racial rhetorical representation matters in the presence or absence of tangible legislation. To answer this question, we return to our experiment and inform respondents that the topic the elected official spoke about in the press release either became law or failed to become law. After providing information about the fate of legislation, we ask respondents whether this changes their opinion of the elected official’s advocacy and why.

In the conclusion, we speak about the growing significance of racial rhetorical representation in demonstrating that elected officials are working on behalf of their constituents in an era of increasing political gridlock. We also connect our findings to the continued importance of Black representation in a period where the salience of race and racial inequality has grown. Not only do we find that Black legislators provide Black people with the most rhetorical representation on race, but we also find that they are more proactive, speaking out on issues that are not widely known and pursuing interests that are not yet part of the national agenda. Black elected officials continue to play a crucial role in advocating for Black interests, and they are necessary for the full and equal representation of Black people.