Background

Major depressive disorder (MDD) impacts over 300 million people globally [Reference Ferrari, Santomauro, Aali, Abate, Abbafati and Abbastabar1], increasing the risk of suicide [Reference Choo, Diederich, Song and Ho2, Reference Large3] and overall mortality [Reference Cuijpers and Smit4], and impairing occupational performance and overall quality of life [Reference Trivedi, Wisniewski, Nierenberg, Gaynes, Warden and Morris5], thereby imposing a high burden on society and healthcare systems [Reference Stewart, Ricci, Chee, Hahn and Morganstein6]. MDD is highly recurrent, with a 60% recurrence rate within 5 years, 67% within 10 years, and 85% within 15 years [Reference Hardeveld, Spijker, De Graaf, Nolen and Beekman7]. Taken together, these characteristics illustrate the impressive burden of MDD on the mental healthcare system, which is often challenged by insufficient funding and staff. Developing a better understanding of the factors that impact recurrence and finding strategies to reduce this recurrence rate are crucial.

Several risk factors for the recurrence of MDD have been identified, with the baseline severity of an index episode providing the most evidence [Reference Gopinath, Katon, Russo and Ludman8–Reference Klein, Holtman, Bockting, Heymans and Burger14]. The severity of the index episode not only predicts recurrence but is also associated with treatment duration [Reference Melartin, Rytsala, Leskela, Lestela-Mielonen, Sokero and Isometsa10, Reference Spijker, De Graaf, Bijl, Beekman, Ormel and Nolen15, Reference Cohen, Brunoni, Boggio and Fregni16]. In addition, the chance of having an MDD recurrence is associated with the number of previous episodes [Reference Bulloch, Williams, Lavorato and Patten17]. The presence of comorbid psychiatric disorders [Reference Hardeveld, Spijker, De Graaf, Nolen and Beekman7, Reference Holma, Holma, Melartin, Rytsala and Isometsa9, Reference Melartin, Rytsala, Leskela, Lestela-Mielonen, Sokero and Isometsa10, Reference Keller, Lavori, Endicott, Coryell and Klerman18, Reference Hoertel, Blanco, Oquendo, Wall, Olfson and Falissard19] as well as residual symptoms after treatment [Reference Hardeveld, Spijker, De Graaf, Nolen and Beekman7, Reference Kanai, Takeuchi, Furukawa, Yoshimura, Imaizumi and Kitamura20] also increases the likelihood of recurrence. Ongoing research is exploring other potential factors, such as neurocognitive function [Reference Wang, Liu, Yang, Dou, Wang and Zhang21], cognitive bias [Reference Beshai, Dobson, Bockting and Quigley22], and time to clinical response [Reference Gueorguieva, Chekroud and Krystal23]. Evidence regarding the influence of family history, social support, low socioeconomic status, and stressful life events is still limited due to methodological constraints [Reference Hardeveld, Spijker, De Graaf, Nolen and Beekman7, Reference Buckman, Underwood, Clarke, Saunders, Hollon and Fearon24].

The roles of treatment intensity and duration during the index episode in recurrence have scarcely been studied. Existing evidence [Reference Mueller, Leon, Keller, Solomon, Endicott and Coryell25] suggests that longer illness duration before treatment initiation correlates with a higher probability of depressive episodes recurring. Additionally, research has explored how the recurrence rate is affected by the length of maintenance treatment. These studies suggest that while maintenance treatment can reduce the recurrence rate in the short term, extended maintenance treatment may not offer significant long-term benefits [Reference Reimherr, Amsterdam, Quitkin, Rosenbaum, Fava and Zajecka26, Reference Guidi, Tomba and Fava27]. However, these studies did not specifically investigate how the duration and intensity of treatment during the index episode might also influence time to recurrence. One study suggests that a shorter treatment duration of the index episode might lead to a higher risk of relapse and recurrence, but this finding was confounded by the number of previous episodes [Reference Berlanga, Heinze, Torres, Apiquián and Caballero28].

Furthermore, heterogeneity among MDD patients complicates treatment [Reference Banerjee, Wu, Bingham, Marino, Meyers and Mulsant29]. Understanding this heterogeneity, by identifying more homogeneous groups within the depressed patient population, is essential, as different subgroups may have varied treatment needs. These subgroups may respond differently to treatments and show varying recurrence patterns [Reference Gueorguieva, Chekroud and Krystal23]. The differences among these groups will help shed light on the underlying causes of disparity in treatment outcomes and recurrence rates. Group classifications are typically based on variables such as gender, age, diagnoses, severity of the disorder, the presence of comorbid conditions, and history of suicide attempts [Reference Musliner, Munk-Olsen, Laursen, Eaton, Zandi and Mortensen30].

Preventing recurrence of depressive episodes is a central aim of treatment [Reference Herrman, Patel, Kieling, Berk, Buchweitz and Cuijpers31]. It is relevant to explore how the intensity and duration of treatment correlate with the time until a depressive episode recurs, both in the whole cohort and within specific subgroups. Such analysis can provide insights for customizing treatment effectively. Insufficient treatment duration or inadequate intensity may fall short of preventing recurrence [Reference Berlanga, Heinze, Torres, Apiquián and Caballero28]. Conversely, excessively prolonged treatment duration may not offer additional benefits in preventing recurrence and may potentially strain healthcare resources, leading to increased waiting times for new clients [Reference Ismail32].

Our study aimed to analyze how treatment intensity and duration affect time to recurrence using real-world data, adjusting for potential confounders. We also aimed to use cluster analysis to identify subgroups and examine how the effects varied among these groups.

Methods

Study setting and data source

This study used an administrative database containing individual-level data of specialist mental healthcare clients in the northern Netherlands, covering January 2004 to February 2020. Data include demographic and clinical variables, the results of Routine Outcome Monitoring (ROM) questionnaires filled out by clients, primary diagnostic categories according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) [33], and detailed mental health service utilization.

Participants

The sample included 36,946 clients diagnosed with unipolar depression at the initial assessment. Clients treated for under 30 days or those without pre-treatment ROM scores within ±30 days of initiation were excluded. To ensure a minimum two-year follow-up period for each patient, only those clients whose treatment ended before December 2017 were included. The study was based on pseudonymized administrative healthcare data for which no ethical approval was needed.

Outcome

The main outcome was time to recurrence of depression, defined as the initiation of a new treatment episode following a 6-month service-free period. This definition has been validated in previous studies using the same Dutch mental health dataset [Reference Kan, Lokkerbol, Jörg, Visser, Schoevers and Feenstra34, Reference Li, Visser, Brilman, de Vries, Goeree and Feenstra35]. For clients with multiple episodes, the second-to-last was the index episode; single episodes without recurrence served as the index.

Exposures

Treatment duration, measured in months, was determined by calculating the interval between two dates: the start of the index episode, which is the first face-to-face diagnostic contact of the clients with the clinician, and the date of the last in-person treatment session [Reference De Beurs, Warmerdam, Oudejans, Spits, Dingemanse and De Graaf36]. Treatment intensity was quantified as the total cost of treatment divided by its overall duration in the index episode. To calculate costs, the service durations of various healthcare professionals were multiplied by their respective unit costs, price year 2019 [Reference Konings, Bruggeman, Visser, Schoevers, Mierau and Feenstra37]. These unit costs, based on professional salary levels, were derived from the Dutch costing manual for health economic evaluations [38] and were hence fixed across patients and providers, with the corresponding unit prices detailed in Supplementary Table S1. Detailed information on service types, contact times, and associated costs is provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Covariates and measurements

Six covariates were used to adjust for confounding and cluster classification: baseline severity of the index episode (measured by the Outcome Questionnaire-45, where lower scores indicate better functioning), comorbidity, the number of previous treatment episodes, antidepressant use during the index episode (yes/no), age, and gender. Comorbidity was grouped into three categories: only personality disorders, only other psychiatric conditions (e.g., anxiety, sleep disorders, ADHD), or both, due to the low prevalence of non-personality psychiatric conditions.

Statistical analysis

We employed the entropy weighting method, assigning weights to covariates based on their importance and variability, to adjust for confounding factors affecting the relationship between treatment intensity, duration, and recurrence [Reference Hainmueller39]. Next, the generalized gamma distribution was selected for modeling time to recurrence based on the Akaike Information Criterion (Supplementary Table S3) and validated using a 75–25% training-validation split (Supplementary Figures S2 and S3). Restricted cubic splines were used to capture non-linear exposure relationships, as this approach flexibly identifies dose-response patterns without arbitrary categorization while mitigating overfitting, and has also been applied in the field of depression care before, though during a different treatment phase [Reference Klein, Breilmann, Schneider, Girlanda, Fiedler and Dawson40]. Knots were placed at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles, consistent with established practice [Reference Klein, Breilmann, Schneider, Girlanda, Fiedler and Dawson40, Reference Harrell41]. Numerical differentiation identified turning points. To facilitate interpretation, we divided the entire population into two groups based on this turning point and applied the model with a linear spline to these groups. Specifically, clients with treatment intensity below the turning point were placed in the low-intensity group, while those above were assigned to the high-intensity group. Similarly, treatment durations shorter than the turning point were categorized as the short-duration group, whereas durations exceeding this point were considered the long-duration group. The analysis finally employed a weighted generalized gamma accelerated failure time (AFT) model with entropy weights. As the proportional hazards assumption had been violated, we chose the AFT model to examine the effects of treatment intensity and duration on the time to recurrence [Reference Wei42]. In the AFT model, an acceleration factor (AF) exceeding one signifies an extended time to recurrence, whereas an AF below one indicates a reduced time to recurrence.

Clustering analysis was conducted to address population heterogeneity by identifying clusters. Models were also fitted by clusters to evaluate the effects of exposures on outcomes with clusters. We employed K-means with Gower distance [Reference Tuerhong and Kim43] as a clustering technique. Clusters were classified based on five variables, as identified in existing literature: age [Reference Hardeveld, Spijker, De Graaf, Nolen and Beekman7], gender [Reference Gueorguieva, Chekroud and Krystal23], prior treatment episodes (yes/no) [Reference Beshai, Dobson, Bockting and Quigley22, Reference Clarke, Mayo-Wilson, Kenny and Pilling44], comorbidities [Reference Hardeveld, Spijker, De Graaf, Nolen and Beekman7], and baseline severity [Reference Hardeveld, Spijker, De Graaf, Nolen and Beekman7]. The number of clusters was established by iteratively repeating clustering and then selecting optimal clusters based on the Silhouette Width and Within-Cluster Sum of Squares with 100 bootstraps [Reference Brusco45].

Sensitivity analysis

Given the potential selection bias due to the substantial exclusion of data in the main analysis, we employed an imputation approach for handling missing data, where each missing value was imputed using Bayesian linear regression [Reference Wei42], generating plausible values by sampling from posterior predictive distributions based on observed covariates, thereby preserving both statistical relationships and appropriate uncertainty in the imputed values. Following the imputation process, we re-conducted the analysis on the larger dataset using the imputed data. Additionally, we tested the robustness of our spline models using alternative knot placements (3, 4, and 5 knots) following Harrell’s recommendations [Reference Harrell41].

Results

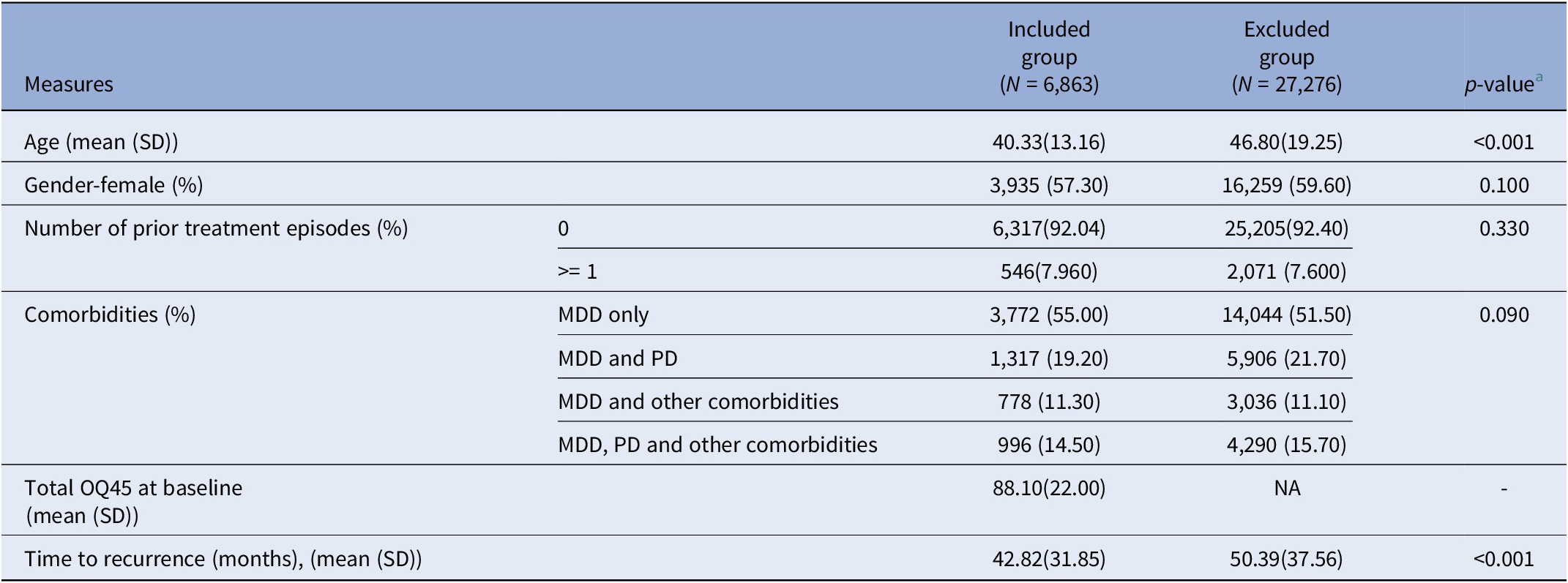

A total of 36,946 clients were diagnosed with MDD between 2004 and 2020. Among them, 27,276 were excluded due to the absence of baseline severity data of the index episode, resulting in 6,863 participants included in our study (see Supplementary Figure S3). The included participants were significantly younger (average age 41 years) than those excluded (average age 48 years). Over a 10-year follow-up, the included group had a shorter time to recurrence (42.82 months) compared to the excluded group (50.39 months) (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and outcome in included and excluded groups

Abbreviations: MDD, major depressive disorder; PD, personality disorder.

a Statistical comparisons between the two groups were performed using a chi-square test for categorical variables, and a t-test for continuous variables.

Supplementary Figure S4 presents the correlation between six covariates and two exposures before and after entropy weighting. Before adjustment, the severity of the index episode, antidepressant use, and the presence of comorbidities were associated with both treatment duration and treatment intensity, while the number of previous treatment episodes and clients’ age were only correlated with treatment intensity. These associations had modest effect sizes.

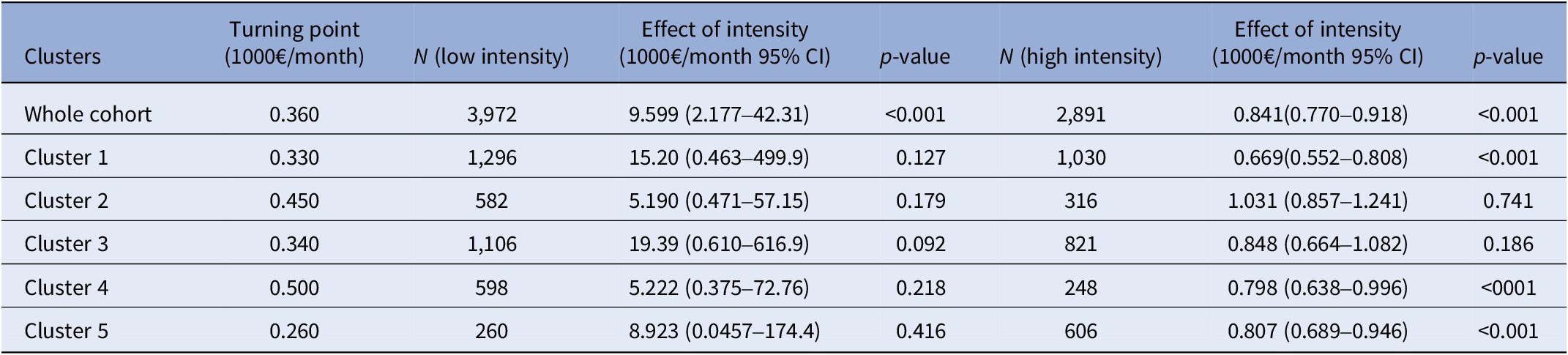

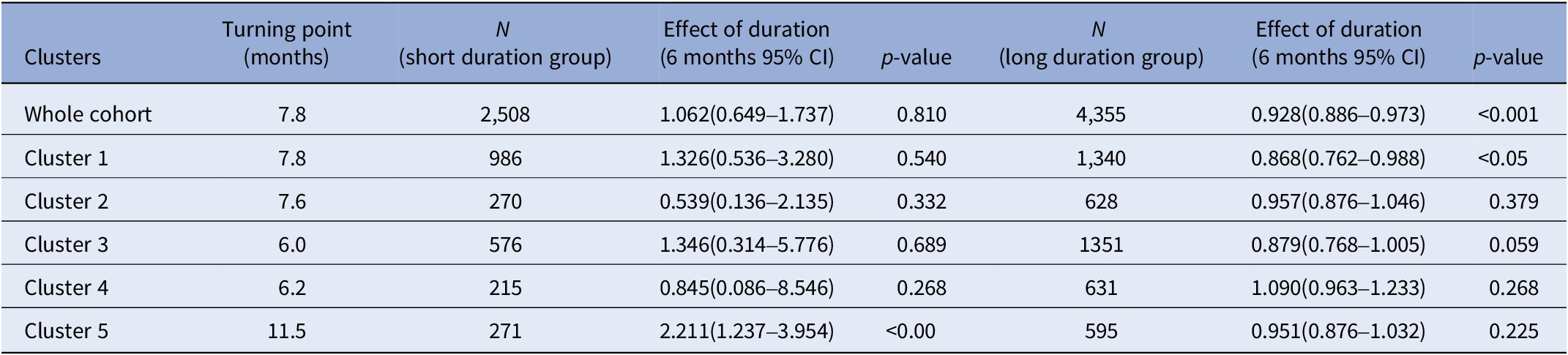

The linearity assessment revealed a non-linear relationship between exposures and recurrence (Supplementary Figures S5 and S6). Within the entire cohort, the turning point for treatment intensity was €360/month (Table 2). For clients undergoing treatment above this threshold, referred to as the high-intensity group, the AFT model showed an acceleration factor of 0.841 (95% CI: 0.770–0.918). This indicates that each €1000/month increase in treatment intensity was associated with a 15.9% (95% CI: 8.2–23.0%) shorter time to recurrence. Conversely, for clients with treatment intensities below this threshold, referred to as the low-intensity group, the AFT model showed a significantly higher acceleration factor of 9.599 (95% CI: 2.177–42.31), suggesting that each €1000/month increase in treatment intensity was associated with a 9.6-fold longer time to recurrence. Regarding treatment duration, the turning point within the whole cohort was 7.8 months. The long-duration group had an acceleration factor of 0.928 (95% CI: 0.886–0.973), indicating that a six-month extension in treatment duration was associated with a 7.2% (95% CI: 2.7–11.4%) shorter time to recurrence. No significant association was observed for the short-duration group (Table 3).

Table 2. The effect of treatment intensity in the complete cohort and by cluster

Table 3. The effect of treatment duration in the complete cohort and by cluster

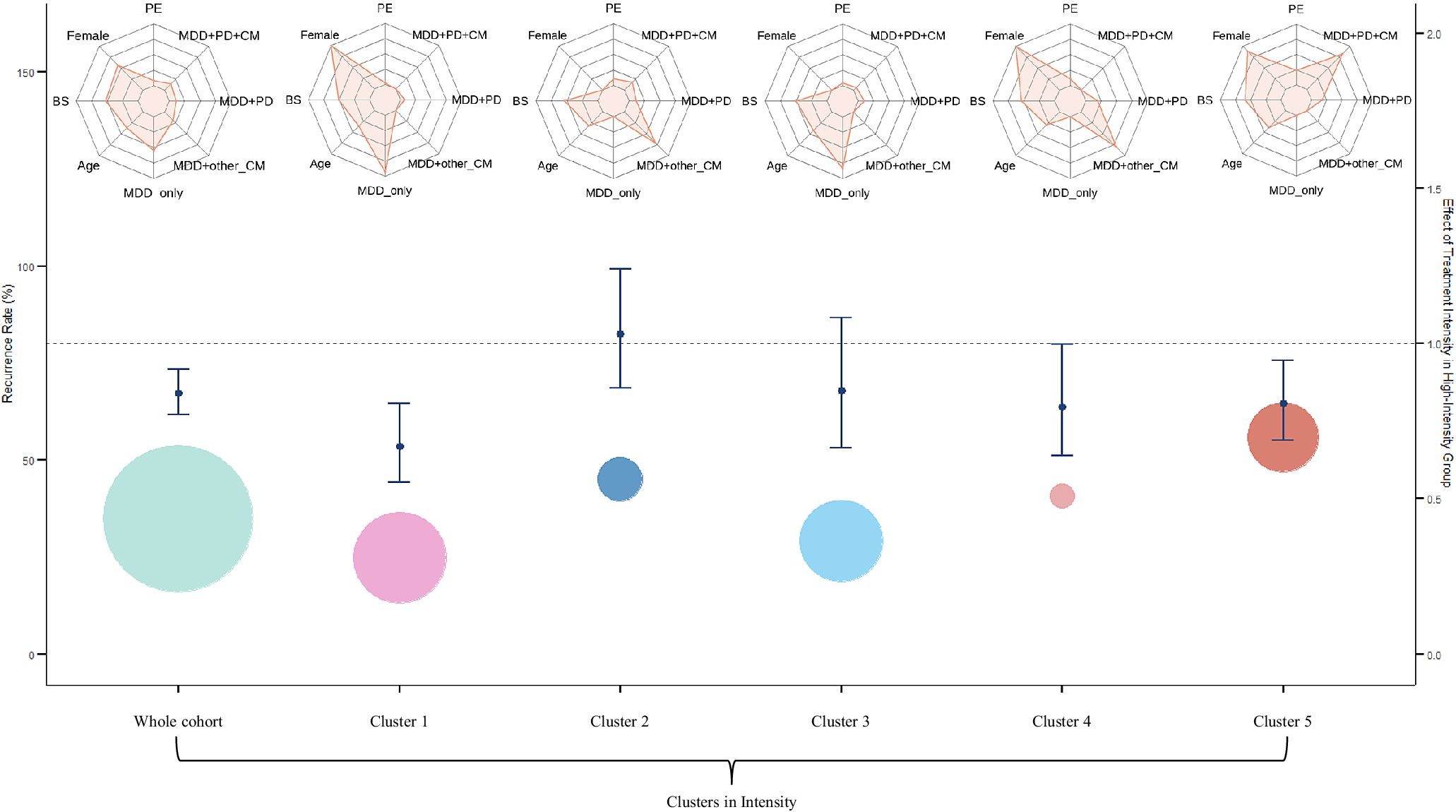

Cluster analysis identified five groups (Clusters 1–5). A graphical representation of this analysis is available in Supplementary Figure S7. Variations in the recurrence rates across these clusters are illustrated in Figure 1. Cluster 1 (female clients with depression only) had the lowest recurrence rate at 18%, while Cluster 5 (female clients with MDD, personality disorder, and comorbidities) had the highest at about 60%. Generalized gamma distribution parameters are reported in Supplementary Table S4.

Figure 1. Cumulative incidence of recurrence across five clusters. CM, comorbidity; MDD, major depressive disorder; PD, personality disorder.

The AFT models showed that Clusters 1, 4, and 5 had similar patterns to the whole cohort in the high-intensity group (Figure 2), with higher treatment intensity associated with shorter time to recurrence. In contrast, the low-intensity group showed no significant associations. Clusters 2 and 3 showed no significant associations with recurrence time in either group. Cluster 4 had the highest turning point at €500/month.

Figure 2. Clustering for recurrence rate and effect treatment intensity in high-intensity group. BS, baseline symptom score; CM, comorbidity; MDD, major depressive disorder; PD, personality disorder; PE, previous episode.

Regarding treatment duration, Cluster 1 displayed an AF of 0.868 (95% CI: 0.762–0.988), indicating that longer treatment duration was associated with shorter time to recurrence in the long-duration group. Cluster 5 showed an AF of 2.2 in the short-duration group, suggesting an association with longer time to recurrence. No significant associations with time to recurrence were observed in the other clusters. Cluster 5 had the largest turning point for treatment duration at 11.5 months.

Results from the sensitivity analysis, conducted on an imputed dataset comprising 34,139 cases, aligned with the findings of the main analysis (Supplementary Tables S5 and S6). The non-linear relationships for treatment intensity and duration are shown in Supplementary Figures S8 and S9. Higher treatment intensity in the low-intensity group was associated with extended time to recurrence, while in the high-intensity group, it was associated with shorter time to recurrence. The turning point for treatment intensity in this larger dataset was €340/month for the whole cohort, aligning closely with €360/month from the main analysis.

The turning points of treatment intensity for each cluster ranged from €320/month to €390/month, with Cluster 5 having the highest at €390/month. As in the main analysis, longer treatment duration in the long-duration group was associated with shorter time to recurrence. In the sensitivity analysis, effects were significant across all clusters in the long-duration group, with Cluster 5 showing the largest turning point at 19.5 months. Effects in short-duration groups were not statistically significant. In sensitivity analyses examining knot placement, the non-linear relationship remained stable across all alternative knot placements tested as shown in Supplementary Figure S10, with turning points ranging from €300 to 340/month, closely approximating our main estimate of €360/month.

Discussion

This study found that increasing treatment intensity may potentially extend the time to recurrence in the group receiving low treatment intensity, after adjusting for confounders. Conversely, for clients in the high-intensity group, an increase in treatment intensity appeared to shorten the time to recurrence. These results suggest a non-linear relationship between treatment intensity and recurrence, which was supported by the linearity check. Our analysis also showed that extended treatment duration reduced the time to recurrence in clients with longer treatment duration, while no significant effect of treatment duration was observed on the time to recurrence in the short-duration group.

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to use extensive longitudinal data to explore the effects of treatment intensity and duration on recurrence, accounting for potential confounders, and hence comparisons with similar studies are challenging. Our research found no evidence of an association between extending treatment duration and time to recurrence in the short-duration group, defined as clients with treatment durations below 7.8 months. This finding remains robust even after adjusting for confounders, such as baseline symptom scores. Consistent findings were also observed in a larger, imputed dataset. Additionally, results indicate that for clients receiving treatment at an intensity below the average turning point of €360/month, higher treatment intensity was associated with longer time to recurrence. This observation could be interpreted as suggesting that low treatment intensity in this group may result in residual symptoms, which subsequently lead to rapid recurrence of depressive symptoms [Reference Kanai, Takeuchi, Furukawa, Yoshimura, Imaizumi and Kitamura20]. In the high-treatment intensity group, however, further increases in treatment intensity were associated with shorter time to recurrence. This could have at least two possible explanations: first, clients may develop a dependency on the treatment or therapist, leading to increased difficulty in discontinuing treatment, which in turn increases the likelihood of recurrence. Second, the presence of unaddressed confounding factors could also contribute to this outcome.

In the literature, a similar non-linear relationship was observed between the total number of treatment sessions and symptom improvement. Shorter treatments with fewer sessions typically lead to faster improvement, while longer durations result in slower gains. However, the optimal number of sessions, or “turning point,” varies across studies, with some suggesting eight sessions as the turning point, beyond which no additional benefit is observed [Reference Beail, Kellett, Newman and Warden46–Reference Erekson, Lambert and Eggett48]. Other studies recommend 10 to 16 sessions [Reference Harnett, O’Donovan and Lambert49, Reference Kopta, Howard, Lowry and Beutler50], while one found the maximum benefit at 25 sessions, noting diminishing returns after that [Reference Lincoln, Jung, Wiesjahn and Schlier51]. Despite variations in settings, populations, and outcome measures, these findings support our conclusion that extended treatment duration may not enhance treatment outcome [Reference Bone, Delgadillo and Barkham52].

Our cluster analysis identified five groups with varying recurrence rates. Cluster 1 had the lowest recurrence rate, likely due to its composition of female clients with MDD, who tend to respond better to treatment [Reference Carter, Cantrell, Zarotsky, Haynes, Phillips and Alatorre53]. In contrast, Cluster 5 had the highest recurrence rate. This can be ascribed to the complexity of the client profiles within this cluster, which includes individuals with MDD in combination with comorbid personality disorders and other psychiatric conditions, presenting a more challenging scenario to prevent or postpone recurrence [Reference Newton-Howes, Tyrer, Johnson, Mulder, Kool and Dekker54]. This result is consistent with a previous study [Reference Melartin, Rytsala, Leskela, Lestela-Mielonen, Sokero and Isometsa10], indicating that clients with more comorbidities are more likely to experience a recurrence. Notably, our observations indicated a 30% recurrence rate in the entire cohort, lower than the rates reported in prior studies [Reference Hardeveld, Spijker, De Graaf, Nolen and Beekman7]. Two possible explanations for this difference might be: first, the minimum duration of our follow-up period is 2 years, which raises the possibility that some clients may not have experienced a relapse within this timeframe; second, our definition of recurrence is re-entering the healthcare service provider’s system. However, a relapse can also occur during the treatment process and may thus not be identified in our data.

The cluster analysis revealed a non-linear relationship between exposures, treatment duration and intensity, and the time to recurrence. In these clusters, consisting of female clients diagnosed with depression, with and without additional comorbidities, or with personality disorders and other comorbid conditions, increasing treatment intensity may be harmful. In the sensitivity analysis, treatment intensity significantly impacted outcomes in all clusters except Cluster 5, following the same trend as the whole cohort. Treatment duration significantly affected outcomes only in Cluster 1 in the main analysis, but did not extend beyond Cluster 1 in the long-duration group during the sensitivity analysis, potentially due to the large imputed sample. Cluster 5 had the highest turning points for both treatment duration and intensity, likely due to the complex conditions of clients with multiple comorbidities.

Our results highlight the importance of estimating treatment intensity and duration to determine the optimal treatment strategies for individuals. Clinicians are advised to closely monitor clients, especially individuals diagnosed with depression, personality disorders, and other comorbidities. Although these clients require relatively longer treatment durations and slightly higher treatment intensity to reach their turning point compared to other clusters, there is no evidence that increasing treatment intensity beyond this point prolongs the time to recurrence for this group. Such attention is essential, considering the limited benefits of excessive treatments and the common belief that more comorbidities need more extensive treatment [Reference Dickinson, Dickinson, Rost, DeGruy, Emsermann and Froshaug55]. Effective monitoring and appropriate treatment adjustment are key to enhancing client outcomes. This could also lead to more efficient resource allocation, allowing for shorter waiting times for new clients and improving the overall quality of care.

Given the pandemic-related shifts in prevalence and service delivery, we next consider the applicability of our findings to current practice in the Netherlands. Our data extend only until February 2020 due to availability; thus, the cohort primarily reflects pre-pandemic care patterns. During the pandemic, depression prevalence fluctuated in line with public health restrictions, and services shifted from face-to-face to tele-mental care. Overall contact volumes were maintained in the large Dutch providers [Reference Chow, Noorthoorn, Wierdsma, Van Der Horst, De Boer and Guloksuz56] during the pandemic, and tele-mental care has been shown to achieve outcomes comparable to those of in-person care [Reference Sugarman and Busch57]. Nowadays, a mix of in-person and tele-mental care is provided. We estimated the associations between treatment intensity and duration and time to recurrence, adjusting for confounders, with intensity defined as unit costs multiplied by clinician time per month, rather than by the mode of delivery. The therapeutic mechanisms linking treatment intensity and duration to time to recurrence, such as skill acquisition, symptom monitoring, and therapeutic alliance, remain operative regardless of delivery modality [Reference Andersson, Titov, Dear, Rozental and Carlbring58]. On this basis, we expect the direction and overall pattern of associations between intensity/duration and recurrence to generalize to current practice, although the turning points of treatment intensity may have shifted after 2020, calling for external validation in post-2020 cohorts.

This study should be seen in light of several strengths and limitations. First, our analyses were not specific to any single treatment modality, but rather included all treatments received, irrespective of treatment type. This reflects the fact that the vast majority of Dutch patients (approximately 95%) receive multimodal care. Additional analyses conducted for the small subgroup of CBT-only patients yielded similar patterns, although these were not statistically significant due to the limited sample size (see Supplementary Figure S11 and Table S7). Second, a large number of clients were excluded due to the absence of their baseline severity scores, which are essential to adjust for confounding. Clients who were excluded were, on average, older, but did not differ in other available demographics. The correlation between baseline severity and treatment intensity and duration, as confirmed by the results of entropy balancing weights, aligns with previous research [Reference Melartin, Rytsala, Leskela, Lestela-Mielonen, Sokero and Isometsa10, Reference Spijker, De Graaf, Bijl, Beekman, Ormel and Nolen15]. The outcomes of our sensitivity analysis on the imputed dataset are consistent with our primary analysis, suggesting that the selection bias resulting from the absence of baseline severity scores may not have significantly impacted our findings. It is important to note that we only employed simple imputation to address missing data, as further steps such as confounder correction and cluster identification, were also necessary before modeling effects.

Third, the main analysis may not accurately pinpoint the turning point for each individual within clusters, leading to relatively wide confidence intervals in the low-intensity group. This issue likely arises from the small sample sizes within each cluster. To address this concern, we conducted sensitivity analyses using a larger imputed dataset, which not only helped narrow the confidence intervals but also further confirmed the robustness of our model. However, this limitation highlights the need for further research employing more sophisticated methods to determine optimal treatment duration and intensity on an individual basis. Furthermore, residual confounding by baseline depression severity may exist despite OQ-45 adjustment. The low-intensity group could consist of a mix of mild cases, non-adherent patients, and fast responders. Future research should use comprehensive severity measures to separate true intensity effects from selection bias. Additional unmeasured confounders, including genetic factors and neurocognitive functioning, may also have influenced our results. Finally, our recurrence definition, based on 6-month treatment gaps, may misclassify some dropouts or non-adherent patients as remitted, potentially biasing recurrence estimates in either direction.

Strong points of our study include the unique dataset with a reasonably large sample size of nearly 7,000 individuals, with at least 2 years and up to 10 years of follow-up. This provides insights into long-term recurrence patterns in a real-world context. We observed that recurrence rates and the effects of treatment duration and intensity varied across different clusters after adjusting for confounding, enriching our understanding of the impact of treatment intensity and duration on the time to recurrence. It is noteworthy that, at least in the high-intensity group, further increasing the intensity or duration of treatment may not yield additional benefits and could even be harmful. This insight is helpful for decision-makers aiming to optimize treatment strategies in a cost-effective manner. Nonetheless, these results should be interpreted with caution due to the potential presence of other residual confounding factors. Finally, the generalized gamma distribution for time to recurrence offers relevant input for future studies that need detailed information about the time until depression re-occurs, such as in health economic decision models.

Conclusion

Higher treatment intensity was associated with longer time to recurrence in the low-intensity treatment group, even after accounting for confounding factors, suggesting potential value in more intensive treatment. Conversely, in the high-intensity treatment group, greater treatment intensity was associated with significantly shorter time to recurrence, which could indicate that intensity increases beyond this threshold did not offer additional benefits. These observations highlight the importance of matching treatment intensity to suit the specific needs of each client. Moreover, cluster analyses showed variation in how treatment intensity affects time to recurrence across patient subgroups, suggesting that individualized treatment approaches warrant further investigation. These findings should be interpreted with caution, as this is an observational study. Despite our efforts to control for all potential confounders, some residual confounding may still be present.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2025.10145.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The programming code will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

We thank Yiling Zhou, Maarten Brilman, and Stijn de Vos for their constructive suggestions for this study.

Funding statement

The development of the data infrastructure for this study was supported by Stichting De Friesland, Leeuwarden, the Netherlands (grant number DS29). Stichting De Friesland had no role in the study design, analysis, and interpretation of the data; report writing; or the decision to submit the article for publication. FL was awarded a personal scholarship from the China Scholarship Council (CSC) under the file number 202006050038, while conducting this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.