Conflict and political insecurity are significant drivers of biodiversity loss, particularly in conservation hotspots (Hanson et al., Reference Hanson, Brooks, Da Fonseca, Hoffmann, Lamoreux and Machlis2009; Daksin & Pringle, Reference Daskin and Pringle2018). Since the political change in February 2021, the majority of conservation programmes across Myanmar, delivered by both government and international civil society, have been halted and much of the environmental progress made over the previous decade is in danger of reversal (Feurer et al., Reference Feurer, Hunt, Maung and Rueff2024). Overexploitation of species and habitat degradation appear to have escalated because of a lack of law enforcement and increased insecurity, as well as wider economic problems (WWF, 2022). Limited international funding to support the sustainable protection of species, habitats and natural resources is also hampering conservation. The increasing threats to Myanmar’s wildlife are particularly concerning as the country harbours important populations of many of Asia’s most threatened species including the Critically Endangered white-bellied heron Ardea insignis (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Keith, Duncan, Tizard, Ferrer-Paris and Worthington2020). This species is a specialist of undisturbed rivers adjacent to subtropical broadleaved forest and restricted to rapidly declining populations in Bhutan, north-east India and northern Myanmar (BirdLife International, 2018; Dema et al., Reference Dema, Towsey, Sherub, Sonam, Kinley and Truskinger2020). Historically, white-bellied herons were recorded across Myanmar as far south as Rakhine State and Bago Yamo and west into northern Chin State, and they were regarded as locally common in northern Myanmar (Smythies, Reference Smythies1986). The species faces numerous threats including habitat loss and degradation, water pollution, impact from human settlements, dynamite fishing, logging, sand/gravel mining and agricultural expansion (Khandu et al., Reference Khandu, Gale and Bumrungsri2021; Menzies et al., Reference Menzies, Rao and Naniwadekar2021).

Given the challenges for species conservation in contemporary Myanmar, new conservation approaches are required. In the absence of strong governance or international support, it is critical to empower and support local biodiversity stewards and governance systems, with both technical capacity and financial resources, to conserve species and the environment. To catalyse such action, WWF-Myanmar established a small grant mechanism to directly support civil society with targeted funds for locally-driven, place-based conservation efforts. Capacity building was delivered to local organizations and communities before offering the small grants. This included training in basic biodiversity conservation, species survey techniques, impact of illegal wildlife trade, habitat management and organizational development. Since 2021 local communities across the country have been awarded 26 grants through this programme.

The small grants programme was developed in response to the political crisis, which had led to a number of international conservation NGOs ceasing operations in Myanmar, resulting in loss of access to international conservation funding for local civil society organizations. A grant under the new scheme was provided to Northern Wildlife Rangers, a local civil society organization in Kachin State, to survey the white-bellied heron Ardea insignis and to identify current threats to the species and its habitat. The Northern Wildlife Rangers had previously identified the white-bellied heron as a species of local importance that required conservation action, but they lacked the resources and technical capacity to conduct surveys and carry out conservation activities. The two river catchments selected by Northern Wildlife Rangers, at Putao–Wai Lang Dam in the west of the study area and at Nawngmung in the east (Fig. 1), represented suitable habitat for the white-bellied heron and were in locations where community-led conservation activities remain feasible even during the ongoing political crisis.

Fig. 1 Location of sightings of the white-bellied heron Ardea insignis during surveys in northern Myanmar during this study (2022–2023) and during earlier surveys (2000–2011; Naing et al. Reference Naing, Lin and Tizard2011). The route of the surveys in this study are Putao–Wai Lang Dam in the west of the study area and Nawngmung in the east. Most sightings in this study were along Nam Lang stream.

Northern Wildlife Rangers conducted surveys along all rivers and streams in the two river catchments during three periods (June–August 2022; January–June 2023; October–December 2023) using three teams of two observers. During each survey period, teams walked along every river or stream for 2 days per week and counted direct sightings of white-bellied herons. The survey teams used GPS devices and data sheets to record the exact locations of white-bellied heron sightings, along with other relevant information such as transect distances, associated species, potential threats and notable geographical features. In each survey, the teams followed the same routes along the rivers, using the same observers. The teams also searched for evidence of breeding such as nests, either occupied or empty. In addition, we collated anecdotal information on threats to white-bellied herons that was provided by communities from Wai Lang Dam village, located near Nam Lang stream.

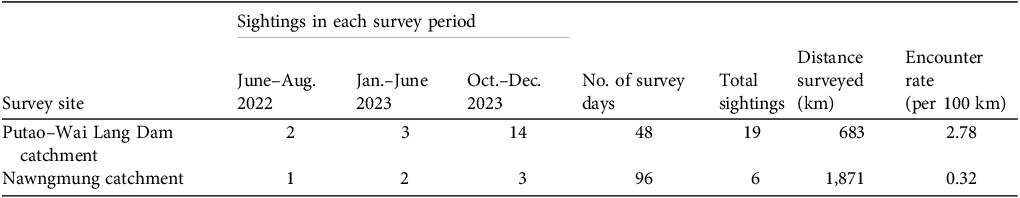

We surveyed 2,554 km across both river catchments over 144 surveys days and recorded 25 sightings of white-bellied herons, at elevations between 550 and 1,000 m. All sightings were of single individuals, mostly standing on the riverbank, with a smaller number detected in flight (Table 1; Plate 1). Based on the sighting records, we concluded that many were repeat detections of the same individuals: two individuals from the Putao–Wai Lang Dam catchment were frequently observed simultaneously near Wail Lang Dam village and upstream of the Nam Lang stream during multiple survey days. We estimated a minimum population on f 2–3 individuals in the river catchment at Putao–Wai Lang Dam and 1–2 individuals in the catchment at Nawngmung (Fig. 1). We did not record any evidence of breeding although the species is believed to breed in northern Myanmar. Local communities provided evidence of at least two white-bellied herons shot in the area during 2019–2020 (Plate 2a), which we believe to be the first photographic evidence of hunting of the species. We also identified threats including abandoned fishing nets (ghost nets), which could accidentally ensnare birds, and widespread use of home-made air-pressured guns by local opportunistic hunters (Plate 2b).

Plate 1 A white-bellied heron Ardea insignis photographed during surveys along the Nawngmung river in northern Myanmar in October 2023. Photo: Northern Wildlife Rangers.

Plate 2 Evidence of hunting in the survey area in Kachin state, northern Myanmar. (a) A white-bellied heron shot by a member of the local community in 2019. (b) A home-made air-pressurized gun used by hunters from the local community. Photos: Northern Wildlife Rangers.

Table 1 White-bellied heron Ardea insignis sightings and encounter rate during surveys of two river catchments in Kachin State in northern Myanmar during 2022–2023.

The white-bellied heron is one of the world’s most threatened bird species, with an estimated global population of only 60 individuals remaining (BirdLife International, 2018; Dema et al., Reference Dema, Towsey, Sherub, Sonam, Kinley and Truskinger2020). During 2009–2011, surveys were conducted across a large area of Kachin State, northern Myanmar, recording an estimated population size of 16 individuals (Naing et al., Reference Naing, Lin and Tizard2011). The majority of the population was within Hukaung Valley Wildlife Sanctuary, a site no longer safe to survey (Naing et al., Reference Naing, Lin and Tizard2011). In 1998 and 1999, King et al. (Reference King, Buck, Ferguson, Fisher, Goblet, Nickel and Suter2001) observed seven white-bellied herons in our survey area but Naing et al. (Reference Naing, Lin and Tizard2011) observed only two individuals in their more recent survey. The survey efforts were not comparable and the methodology differed, therefore it is difficult to draw any conclusions about species decline in the area.

We are able to confirm the continued presence of a small number of white-bellied herons across the two river catchments in our survey area, with a similar population size to earlier surveys. Nineteen out of a total 25 sightings were from the upper reaches of the Putao–Wai Lang Dam catchment (along the Nam Lang stream), in an area of high-quality habitat with low anthropogenic disturbance and denser canopy cover compared to other areas surveyed.

A recent study reported that the population of white-bellied herons in Namdapha Tiger Reserve, a stronghold in India, has declined over the past 6 years (Menzies et al., Reference Menzies, Suryawanshi and Naniwadekar2024). This raises serious concern for the survival of the remaining global population of the heron. Regular monitoring, along with the conservation of its remaining critical stronghold areas, is essential to address its alarming population decline (Menzies et al., Reference Menzies, Suryawanshi and Naniwadekar2024).

We identified several threats to the white-bellied heron in northern Myanmar, including hunting (Plate 2). We documented two cases of white-bellied herons being shot in our survey area but believe the birds were shot opportunistically rather than being targeted, given that shooting large birds is prevalent in the area. However, given the very small global population, any incidents of hunting are of great concern. Unfortunately, the threats to white-bellied herons in northern Myanmar, and to biodiversity in general, are increasing under the current political situation. The white-bellied heron is totally protected under Myanmar law but wildlife law is not currently enforced in the area. Furthermore, local people are highly dependent on natural resources for their livelihoods and thus hunting pressure on all species of wildlife, including the white-bellied heron, is increasing.

Our surveys confirm the continued presence of the white-bellied heron in northern Myanmar, and by involving local biodiversity stewards, we have paved the way for the essential community outreach activities that are crucial to reduce incidental killings in future. These outreach activities should be designed and delivered by local communities with technical support from the wider conservation community. The Northern Wildlife Rangers and Naga Biodiversity Conservation Association are undertaking site-based species conservation in northern Myanmar and the adjacent state of Nagaland in India but they need financial support to continue their efforts. Community-led conservation and outreach are invaluable in addressing the global biodiversity crisis and are essential in contexts such as contemporary Myanmar. Providing funding and capacity building to local biodiversity guardians could catalyse support for the protection of species, habitats and natural resources by local communities. This includes iconic species such as the white-bellied heron, which are on the verge of global extinction.

Author contributions

Project design: NZS, BS, SND, SSY, NMS; data collection: BS, SND; data analysis and writing: all authors.

Acknowledgements

We thank the teams of Northern Wildlife Rangers for survey work; San Naing Sin and Zargon Hti Na who accompanied the survey team; Thet Zaw Naing and Than Zaw for survey information; Kyaw Zay Ya for preparing maps; two anonymous reviewers for their critiques; and local communities for support during the survey and for sharing information. Funding was provided by the J. Bishop Fund through WWF-US.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.

Data availability

The data supporting our findings are available from the corresponding author on request.