Non-technical Summary

A recently discovered fossil site in southern Mississippi, approximately 27–28 million years old, represents the first of this age from the Gulf Coastal Plain outside of Florida. The fossils, which include well-preserved plant material as well as reptiles, amphibians, fishes, land mammals, and marine mammals, were found in deltaic deposits near the base of the Catahoula Formation – a geologic unit broadly distributed across the Gulf Coastal Plain. Interestingly, the land mammals are represented primarily by species previously known almost exclusively from the Great Plains, the northern Rocky Mountains (Montana), and the John Day region of Oregon, with only a few apparently endemic to the Gulf Coast. They include a possum, a shrew, a squirrel, a “mountain beaver,” a small true beaver, and several other rodents, as well as weasel- and badger-like carnivores, a small primitive dog-like carnivore, a tapir, a “hippo-like” species, a small horse, a rhinoceros, and a giant wild-boar-like omnivore. Marine mammals are represented by a small “sea-cow” and a small dolphin-like whale. The close association of the land mammals from this site in Mississippi with those from so much farther north and west provides important new information on the geographic ranges of these animals across North America at this time, because by about 23 million years ago, the mammals of the Midcontinent and those of the Coastal Plain were much different. This, in large part, likely reflects the changing climate of the interior of the continent, which was becoming more arid, relative to that along the southern and southeastern coasts, which remained subtropical coastal forests.

Introduction

Fossil mammal assemblages representative of the Arikareean North American Land Mammal Age (ca. 18–30 Ma) are known primarily from the Great Plains, where this age was typified (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Chaney, Clark, Colbert, Jepsen, Reeside and Stock1941; Tedford et al., Reference Tedford, Skinner, Fields, Rensberger, Whistler, Galusha, Taylor, Macdonald, Webb and Woodburne1987, Reference Tedford, Swinehart, Swisher, Prothero, King, Tierney, Prothero and Emry1996, Reference Tedford, Albright, Barnosky, Ferrusquia-Villafranca, Hunt, Storer, Swisher, Voorhies, Webb, Whistler and Woodburne2004), but also from the John Day Formation, Oregon (e.g., Fremd et al., Reference Fremd, Bestland and Retallack1994; Hunt and Stepleton, Reference Hunt and Stepleton2004; Albright et al., Reference Albright, Woodburne, Fremd, Swisher, MacFadden and Scott2008), and the Renova Formation, Montana (Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen1977; Calede, Reference Calede2016, Reference Calede2020). Figure 1 shows the general location of various sites in these areas, which are mentioned often throughout the text. There are also, however, a few rare and isolated sites known from the Gulf Coastal Plain. Notable among these, also shown in Figure 1, are the White Springs, Cowhouse Slough, SB-1A, Brooksville 2, and Buda local faunas of Florida, and the Toledo Bend Fauna of easternmost Texas (Patton, Reference Patton1969; Frailey, Reference Frailey1979; Morgan, Reference Morgan and Morgan1989, Reference Morgan1993, Reference Morgan1994; Albright, Reference Albright1991, Reference Albright1994, Reference Albright1996, Reference Albright, Terry, LaGarry and Hunt1998a, Reference Albrightb, Reference Albright1999; Hayes, Reference Hayes2000; MacFadden and Morgan, Reference MacFadden and Morgan2003; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Czaplewski and Simmons2019). Additionally germane to this discussion is the fauna from Florida’s I-75 locality. Originally considered Whitneyan in age by Patton (Reference Patton1969), then later placed near the Whitneyan/Arikareean boundary by Hulbert (Reference Hulbert2001), more recent analysis estimates its age as late Whitneyan (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Czaplewski and Simmons2019).

Figure 1. (1) Index map of the contiguous USA, plus Saskatchewan, Canada, showing the general location of Arikareean-aged sites across the Great Plains and western U.S. mentioned throughout the text. Saskatchewan: Kealey Springs LF; Montana: faunas from the Cabbage Patch beds (Renova Formation), including the Tavenner Ranch LF; South Dakota: Wounded Knee-Sharps and Blue Ash (late Whitneyan) faunas; Nebraska: faunas from Ridgeview, Wagner, Agate, and Pine Ridge sites; California: Kew Quarry LF; and Oregon: faunas from the John Day Formation. (2) Sites of Arikareean age in the Gulf Coast region plus Florida (numbered); star denotes Jones Branch locality.

Several taxa from these localities are apparently endemic to the Gulf Coastal Plain region and support the view that it represented a unique biogeographic province separate from the central and northern Great Plains region during the late Oligocene–Early Miocene (Quinn, Reference Quinn1955; Wilson, Reference Wilson1956; Patton, Reference Patton1969; Webb, Reference Webb1977; Frailey, Reference Frailey1979; Albright, Reference Albright, Terry, LaGarry and Hunt1998a; Hayes, Reference Hayes2000; MacFadden and Morgan, Reference MacFadden and Morgan2003). On the other hand, the presence of numerous additional taxa that were originally described from the more northern localities indicates that a faunal link between that region and the Gulf Coastal Plain was never entirely severed (Albright, Reference Albright, Terry, LaGarry and Hunt1998a). Such taxa include, at the generic level, Miohippus, Diceratherium, Moropus, Nexuotapirus, Daphoenodon, Daeodon, and Arretotherium, all of which are members of the late Arikareean Toledo Bend Fauna. The known ranges of these taxa as determined through geochronological and chronostratigraphic techniques (radioisotopic dating of volcanic horizons and magnetostratigraphy) at their Great Plains and John Day localities provide the primary means of dating Arikareean sites in the Gulf Coastal Plain (and Florida) where high-resolution temporal control is, in most cases, lacking (see discussions in Tedford and Hunter, Reference Tedford and Hunter1984; Albright, Reference Albright, Terry, LaGarry and Hunt1998a).

This report adds several more taxa to that list, but from even farther back in time—the early Arikareean (Ar1 and Ar2). These additions are from an important new locality in the Gulf Coastal Plain discovered by avocational fossil collectors (A. Weller and R. Rains of Waynesboro, Mississippi) yielding an assemblage of taxa that constitutes the Jones Branch Local Fauna (LF) (Albright et al., Reference Albright, Phillips, Starnes, Stringer and Weller2016a, Reference Albright, Starnes and Phillipsb). As with those faunas noted above, the Jones Branch LF includes new species apparently endemic to the Gulf Coastal Plain, but also shares several taxa known previously from Midcontinental Arikareean (and pre-Arikareean) localities. These include Miohippus, Diceratherium, Protapirus, and Elomeryx, all of which lend further support for at least some level of faunal continuity between these two regions during this time. Interestingly, however, are several small mammals previously known only from the Midcontinent and Pacific Northwest such as Mesoscalops, Hesperopetes, Downsimus, Apeomys, Kirkomys, and Leptochoerus, that also indicate at least some level of faunal continuity between these two regions and the Gulf Coastal Plain during this time. The occurrence of these taxa in the Gulf Coastal Plain is somewhat surprising given the difference in paleoenvironments that existed during the Oligocene between this region and the more northern localities. Thus, the endemism noted above inferring that these regions represented different biogeographic provinces by the late Oligocene–Early Miocene was not yet as strongly apparent during the early to mid-Oligocene. This will be discussed further throughout the paper.

Sedimentological and stratigraphic work at the site has determined that the fossils are derived from a distributary channel lag at the base of the Catahoula Formation, which rests unconformably on interbedded marine marl/clay beds of the subjacent, Oligocene, Paynes Hammock Formation. An abundance of teleostean otoliths dominated by sciaenids (drums and croakers; Stringer, Reference Stringer2016), together with the muddy ‘shell-hash’ nature of the matrix from which the fossils are recovered (Fig. 2), which includes the bivalve Donax sp., provides strong indicators of a tidally influenced, estuarine paleoenvironmental setting—exactly that expected given the inferred coastal location of the Jones Branch site during the mid-Oligocene (Fig. 3). The remains of terrestrial and marine-adapted mammals, in addition to remains of reptiles, amphibians, fishes, and terrestrial plants, washed into this setting. Studies on the latter groups will be addressed elsewhere (e.g., Cicimurri et al., Reference Cicimurri, Ebersole, Stringer, Starnes and Phillips2025).

Figure 2. Image showing the ‘shell-hash’ lithology of the deposit from which fossils at the Jones Branch site were recovered. Note crocodilian osteoderm among oyster shells.

Figure 3. Inferred Oligocene shoreline for the southeastern United States based on mapped surface geology (Ebersole, Reference Ebersole2016).

Originally thought to be temporally equivalent with the Toledo Bend Fauna because of the presence of rhinoceros, tapir, and anthracothere material, which are common mammalian components at Toledo Bend (Albright, Reference Albright1999), more detailed study revealed that the representatives of these groups at Jones Branch are earlier occurring species and that few, if any, taxa are shared. Like the Toledo Bend Fauna, but in contrast to faunas inferred to be of similar age in Florida, the Jones Branch LF apparently lacks camels and oreodonts. However, a single lower molar of an oreodont was recently identified by LBA in the collection of material from Toledo Bend at the South Carolina State Museum. This specimen will be noted in more detail in another report. Also, out of hundreds of specimens from Toledo Bend, only two, a ramal fragment with m2–3 and an isolated m1, represent the occurrence of a camel there. The Jones Branch LF currently represents the only assemblage of early Arikareean age yet known from the Gulf Coastal Plain outside of Florida, and greatly adds to our understanding of this region during the Oligocene.

Geologic setting, stratigraphy, and age of the Jones Branch Local Fauna

The Catahoula Formation (mid-Oligocene–Upper Miocene in Mississippi) extends from Texas to Alabama with a maximum thickness exceeding 245 meters in central Louisiana (Dockery and Thompson, Reference Dockery and Thompson2016). Exposures are common throughout its outcrop belt, except where it is masked by younger units, such as extensive terraces and the alluvium of modern stream courses. In eastern Mississippi, it unconformably overlies the Paynes Hammock and Chickasawhay formations, and, in places, the Vicksburg Group stratigraphically below the Chickasawhay, and it underlies the Hattiesburg Formation. In this area, the Catahoula Formation is composed of unweathered gray-/green-colored, fissile clays interspersed with interbedded distributary channel and thick fine-grained to coarse graveliferous sands of an emergent delta with marginal marine, brackish water, and terrestrial influences.

At the Jones Branch locality, the basal clays of the siliciclastic sequence of the Catahoula Formation are interrupted by a series of thin syndepositional channel lenses along a narrow horizon. These fissile clays preserve an excellent macroflora of lignitized broadleaf and palmetto fossils and grade upward into massive, more uniform, non-fossiliferous freshwater clays. The fossil fauna, however, appears to be derived from a single horizon consisting of a tidally influenced, estuarine, muddy ‘shell-hash’ lag within one of these distributary channels that rests directly on the subjacent glauconitic, sandy clay marl, and soft limestones of the Paynes Hammock Formation. This phosphate nodule-bearing lag contains a rich assortment of fossil mollusks, plus marine and terrestrial vertebrates, and appears to be somewhat bimodal in distribution. The larger marine vertebrate and invertebrate fauna, such as the oysters and dugong ribs, show signs of abrasion from reworking, whereas, in contrast, the terrestrial vertebrate assemblage is nearly pristine and suggests less post-depositional reworking or transportation. Vertebrate fossils include numerous rodents, carnivores, perissodactyls, artiodactyls, sirenians, reptiles, amphibians, sharks, and teleostean fish remains.

At the site, the Paynes Hammock/Catahoula Formation boundary is marked by a thin, fine-grained, sandy, indurated ledge, with well-preserved primary structures of ripple marks on its upper surface interpreted as once belonging to a sandy tidal flat. Based on the mapping of the geology of Wayne County (May et al., Reference May, Baughman, McCarty, Glenn and Hall1974), the fossil horizon lies well below the last regional occurrence of the benthic foraminifera Heterostegina, which marks the uppermost beds of the Catahoula Formation in the shallow subsurface. Important with respect to determining the age of the Jones Branch LF, therefore, is the age of the top of the Paynes Hammock Formation, which is much more amenable to dating due to its deposition in a marine environment than is the fluvial and deltaic Catahoula Formation. Additionally, many of the mammals from the site are also biochronologically diagnostic and therefore provide data that further refine its age.

In Dockery and Thompson (Reference Dockery and Thompson2016, fig. 343; reproduced from Dockery, Reference Dockery1996, fig. 7), the Paynes Hammock Formation and the Chickasawhay Limestone are shown to be correlative with calcareous nannoplankton zone NP24 and with the Ciperoella ciperoensis (previously Globigerina; see Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Hemleben, Coxall and Wade2018) and Globorotalia [=Paragloborotalia] opima planktonic foraminiferal zones, respectively (also see Siesser, Reference Siesser1983). These are the zones to which Poag (Reference Poag1966, p. 399; 1972) correlated the two formations, which he considered “a single biostratigraphic unit” based on “the apparent absence of a distinct faunal change” between them (i.e., C. ciperoensis was found in both units). More recent work since these earlier publications (e.g., Poag, Reference Poag1966, Reference Poag1972; Dockery, Reference Dockery1996) has refined the boundaries and bounding ages of Oligocene calcareous nannofossil and planktonic foraminiferal zones (Berggren and Pearson, Reference Berggren and Pearson2005; Wade et al., Reference Wade, Pearson, Berggren and Pälike2011; Agnini et al., Reference Agnini, Fornaciari, Raffi, Catanzariti, Pälike, Backman and Rio2014; Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Hemleben, Coxall and Wade2018; and especially Coccioni et al., Reference Coccioni, Montanari, Bice, Brinkhuis and Deino2018). For example, as seen in Figure 4, the Ciperoella ciperoensis Partial-Range Zone (PRZ), equivalent to Oligocene Planktonic Foraminifera Zone O6, correlates with the lower part of NP25 (Chattian), the latter of which has a basal age of 26.8 Ma (from Gradstein et al., Reference Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012, tables A3.1, A3.4; Agnini et al., Reference Agnini, Fornaciari, Raffi, Catanzariti, Pälike, Backman and Rio2014; Coccioni et al., Reference Coccioni, Montanari, Bice, Brinkhuis and Deino2018; Speijer et al., Reference Speijer, Pälike, Hollis, Hooker, Ogg, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020). It is important to note, however, that C. ciperoensis ranges from about mid-Rupelian to early Aquitanian (Zone O3 to within Zone M1a, Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Hemleben, Coxall and Wade2018). Similarly, the Paragloborotalia opima Highest-Occurrence Zone (HOZ), equivalent to Zone O5 with a basal age of 27.4 Ma, correlates with the upper part of NP24 (lower Chattian), although the total range of this taxon is from early Rupelian to early Chattian (about 32.3 to 26.9 Ma; Coccioni et al., Reference Coccioni, Montanari, Bice, Brinkhuis and Deino2018).

Figure 4. Biochronologic range of selected mammalian taxa recovered from the Jones Branch site. Data mainly from Tedford et al. (Reference Tedford, Swinehart, Swisher, Prothero, King, Tierney, Prothero and Emry1996, Reference Tedford, Albright, Barnosky, Ferrusquia-Villafranca, Hunt, Storer, Swisher, Voorhies, Webb, Whistler and Woodburne2004) and various chapters in Janis et al. (Reference Janis, Scott and Jacobs1998, Reference Janis, Gunnell and Uhen2008). The Jones Branch horizon (star) is within a distributary channel lag of the Catahoula Formation that rests immediately above the Paynes Hammock Formation. The basic stratigraphy from Dockery and Thompson (Reference Dockery and Thompson2016, fig. 343) is correlated to NALMAs, planktonic foraminifer zones, calcareous nannoplankton zones, and to the GPTS based on the most recent interpretations of those zones as follows: GPTS base from GTS2020 (Speijer et al., Reference Speijer, Pälike, Hollis, Hooker, Ogg, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020); planktonic foraminifer zones (but not boundary dates) from Wade et al. (Reference Wade, Pearson, Berggren and Pälike2011); boundary dates for planktonic foraminifer and calcareous nannoplankton zones from Agnini et al. (Reference Agnini, Fornaciari, Raffi, Catanzariti, Pälike, Backman and Rio2014), Coccioni et al. (Reference Coccioni, Montanari, Bice, Brinkhuis and Deino2018), and GTS2020; boundary dates for the Arikareean from Albright et al. (Reference Albright, Woodburne, Fremd, Swisher, MacFadden and Scott2008); base of Chickasawhay and Bucatunna formations from magnetostratigraphy of Miller et al. (Reference Miller, Thompson and Kent1993). Ar1 = early early Arikareean; Ar2 = late early Arikareean; Ar3 = early late Arikareean; Ar4 = late late Arikareean; Wt, Whitneyan; Or, Orellan. Dotted line represents the absence of Sinclairella beyond Ar1 with the exception of its presence in Florida’s Ar3 Buda LF.

Poag (Reference Poag1972, text-fig. 3) noted the presence of the following biochronologically important foraminifera in the Paynes Hammock Formation: Ciperoella ciperoensis, Ciperoella angulisuturalis, and Chiloguembelina cubensis. The first two were also found in the underlying Chickasawhay Limestone. As noted above, the range of C. ciperoensis spans most of the Oligocene into the lowest Miocene, but the latter two taxa constrain the age of the Paynes Hammock/Chickasawhay formations to between 29 Ma and 27.41 Ma (i.e., the LO of C. angulisuturalis and HCO of Chiloguembelina cubensis, respectively = Oligocene Planktonic Foraminifera Zone O4 of Wade et al., Reference Wade, Pearson, Berggren and Pälike2011; also see GTS2012, Appendix 3; Coccioni et al., Reference Coccioni, Montanari, Bice, Brinkhuis and Deino2018; Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Hemleben, Coxall and Wade2018). Although C. cubensis was not recorded from Poag’s section PH2 (Reference Poag1966, text-fig. 7), he did note its occurrence in the lowest level of section S19 and in a lower and upper level of section CX; C. angulisuturalis was noted from only the lower part of section S19. With a 91% faunal resemblance across sections PH2, S19, and CX, Poag (Reference Poag1966) surmised that the differences may have been due to deposition of each of these sections in somewhat different environments.

Coccioni et al. (Reference Coccioni, Montanari, Bice, Brinkhuis and Deino2018) provided two solutions for the Rupelian/Chattian boundary, which they placed at the HCO of Chiloguembelina cubensis and within the lower part of magnetochron C9n in the Monte Cagnaro, Italy, location chosen for the base Chattian GSSP, those dates being 27.82 Ma and 27.41 Ma. In the most recent time scale, GTS2020, 27.82 Ma falls below chron C9n, within C9r; hence the use herein of 27.41 Ma, which falls within C9n (Fig. 4). Although these revisions preclude earlier correlations of the Paynes Hammock/Chickasawhay formations to the Ciperoella ciperoensis PRZ and Paragloborotalia opima HOZ planktonic foraminiferal zones, the new correlations are still consistent with the calcareous nannoplankton zone NP24 correlation of Siesser (Reference Siesser1983) and Dockery (Reference Dockery1996), the planktonic foraminifera zone P21 correlation of Poag (Reference Poag1972), and the P20–P21a correlation of Miller et al. (Reference Miller, Thompson and Kent1993). These data, including the placement of the HCO of Chiloguembelina cubensis at 27.41 Ma, provide a revised correlation of the Paynes Hammock/Chickasawhay formations with the Ciperoella angulisuturalis/Chiloguembelina cubensis Concurrent Range Zone of late Rupelian age (Wade et al., Reference Wade, Pearson, Berggren and Pälike2011), in turn inferring that the top of the Paynes Hammock Formation is essentially coincident with the Rupelian/Chattian boundary.

Magnetostratigraphic analysis of the Paynes Hammock and Chickasawhay formations further supports this correlation. Miller et al. (Reference Miller, Thompson and Kent1993) determined that the Paynes Hammock Formation possibly spanned chrons C10r through C10n and that the underlying Chickasawhay Limestone ranged from uppermost C11r at its base (30 Ma, Vandenberghe et al., Reference Vandenberghe, Hilgen, Speijer, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012, table 28.3; 29.97 Ma, Speijer et al., Reference Speijer, Pälike, Hollis, Hooker, Ogg, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020, table 28.1) through C10r. These correlations also indicate a late Rupelian age for the Paynes Hammock and Chickasawhay formations (Fig. 4). Additionally, Miller et al. (Reference Miller, Thompson and Kent1993, table 1) reported several 87Sr/86Sr isotope values that further support this age assignment. Values that range from 0.707927 to 0.708075 for the Chickasawhay Limestone (plus a value of 0.707788 by Denison et al., Reference Denison, Koepnick, Fletcher, Dahl and Baker1993) fall within the Rupelian section of the 87Sr/86Sr curve of MacArthur et al. (Reference MacArthur, Howarth, Shields, Zhou, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020, fig. 7.2, LOESS 6 Look-up table). Dockery and Thompson (Reference Dockery and Thompson2016) also noted that Denison et al. (Reference Denison, Koepnick, Fletcher, Dahl and Baker1993) reported 87Sr/86Sr isotope values for the Paynes Hammock Formation of 0.707865 derived from samples of Ostrea blandpiedi Howe, Reference Howe1937, also indicative of the Rupelian (McArthur et al., Reference MacArthur, Howarth and Bailey2001, Reference MacArthur, Howarth, Shields, Zhou, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020). These values are consistent with Coccioni et al.’s (Reference Coccioni, Montanari, Bice, Brinkhuis and Deino2018) reported value of 0.708105 ± 0.00001 for the base of the Chattian (0.708040 in MacArthur et al., Reference MacArthur, Howarth, Shields, Zhou, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020, LOESS 6 Look-up table).

To the extent that the top of the Paynes Hammock Formation must be very near the Rupelian/Chattian boundary (27.41 Ma, solution 2 of Coccioni et al., Reference Coccioni, Montanari, Bice, Brinkhuis and Deino2018), the stratigraphic level of the Jones Branch site near the base of the overlying Catahoula Formation suggests a very earliest Chattian age, especially in consideration of the global regression noted to have occurred at that boundary (Van Simaeys et al., Reference Van Simaeys, De Man, Vandenberghe, Brinkhuis and Steurbaut2004), which may be responsible for the unconformity between the Paynes Hammock and Catahoula formations. Albright et al.’s (Reference Albright, Woodburne, Fremd, Swisher, MacFadden and Scott2008, p. 230) biostratigraphic work in the John Day Formation, Oregon, resulted in an estimated age of “about 28 Ma” for the Ar1–Ar2 boundary, as did the more recent work by Calede (Reference Calede2020) in the Cabbage Patch beds in the northern Rocky Mountains, Montana (ca. 28.1 Ma). This, together with all the data noted above, supports an estimated age for the Jones Branch LF very near the Rupelian/Chattian boundary and within the early Arikareean. The mammals described and discussed in detail below will bear substantially on, and help refine, the age of the Jones Branch LF site.

Materials and methods

Fossils were recovered from a site near the town of Waynesboro, Mississippi, within a small tributary of Jones Branch, which in turn is a tributary of the Chickasawhay River. The fossil-bearing horizon extends for approximately 10–15 meters along the creek bottom, and specimens were recovered primarily by shoveling matrix into screens that were simultaneously washed in the creek and sorted. Small specimens, such as rodent teeth, shark teeth, snake vertebrae, and otoliths, were recovered by sieving matrix through fine-mesh screens (see Cicimurri et al., Reference Cicimurri, Ebersole, Stringer, Starnes and Phillips2025, for further details). Most of the specimens reported herein are curated at the Mississippi Museum of Natural Science, although a few are in the collections of the South Carolina State Museum. Detailed information regarding the location of the site can be found at those institutions.

Geochronology/chronostratigraphy

The version of the global Geomagnetic Polarity Time Scale (GPTS) used for the temporal framework in this contribution is the Paleogene portion of both GTS2012 (Vandenberghe et al., Reference Vandenberghe, Hilgen, Speijer, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012) and GTS2020 (Speijer et al., Reference Speijer, Pälike, Hollis, Hooker, Ogg, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020), as well as the work of Coccioni et al. (Reference Coccioni, Montanari, Bice, Brinkhuis and Deino2018). The terms “Fauna” and “Local Fauna” (LF) follow Tedford (Reference Tedford1970) and definitions in Woodburne (Reference Woodburne1987, Reference Woodburne2004). The Ar1 (early early), Ar2 (late early), Ar3 (early late), and Ar4 (late late) divisions of the Arikareean North American Land Mammal Age (NALMA) follow Tedford et al. (Reference Tedford, Skinner, Fields, Rensberger, Whistler, Galusha, Taylor, Macdonald, Webb and Woodburne1987, Reference Tedford, Swinehart, Swisher, Prothero, King, Tierney, Prothero and Emry1996, Reference Tedford, Albright, Barnosky, Ferrusquia-Villafranca, Hunt, Storer, Swisher, Voorhies, Webb, Whistler and Woodburne2004), with revised temporal boundaries of these divisions following Albright et al. (Reference Albright, Woodburne, Fremd, Swisher, MacFadden and Scott2008). Bioevent terminology follows definitions in Woodburne (Reference Woodburne2004), Wade et al. (Reference Wade, Pearson, Berggren and Pälike2011), and Bergen et al. (Reference Bergen, Truax, Kaenel, Blair, Browning, Lundquist, Boesiger, Bolivar and Clark2019): first appearance datum (FAD); last appearance datum (LAD); highest common stratigraphic occurrence (HCO); highest stratigraphic occurrence (HO); highest occurrence zone (HOZ); lowest stratigraphic occurrence (LO); Concurrent Range Zone (CRZ); partial range zone (PRZ); mega-annum (million years), a radioisotopically calibrated numerical age (Ma); millions of years, elapsed time or duration (Myr); thousands of years, elapsed time or duration (Kyr).

Anatomical abbreviations

AP and TR, antero-posterior (length) and transverse (width) measurements, respectively; P or M, upper premolars and molars, respectively; p or m, lower premolars and molars, respectively. Measurements were taken with a Kobalt electronic caliper with digital display (to the nearest 0.01 mm) or using a reticule in the eyepiece of a microscope.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

Amherst College Museum (ACM), Amherst, Massachusetts; American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), New York; Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CM), Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; College of Charleston Natural History Museum (CCNHM), also known as the Mace Brown Museum of Natural History, South Carolina; Frick: American Mammals Collection (F:AM) at the AMNH; Florida Museum of Natural History (FLMNH), University of Florida, Gainesville; Field Museum of Natural History (FM), Chicago, Illinois; John Day Fossil Beds National Monument (JODA), Kimberly, Oregon; Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (LACM), California; Mississippi Museum of Natural Science (MMNS), Jackson; South Carolina State Museum (SCSM), Columbia (note: only “SC” is used as the prefix in catalogue numbers for specimens at the SCSM); University of Florida/Florida Geological Survey (UF/FGS), Gainesville; University of Nebraska State Museum (UNSM), Lincoln; United States Geological Survey (USGS); Yale Peabody Museum, Princeton University Collection (YPM PU), New Haven, Connecticut.

Systematic paleontology

Mammalia Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1758

Metatheria Huxley, Reference Huxley1880

Herpetotheriidae Trouessart, Reference Trouessart1879

Herpetotherium Cope, Reference Cope1873

Type species

Herpetotherium fugax (Cope, Reference Cope1873).

Herpetotherium sp.

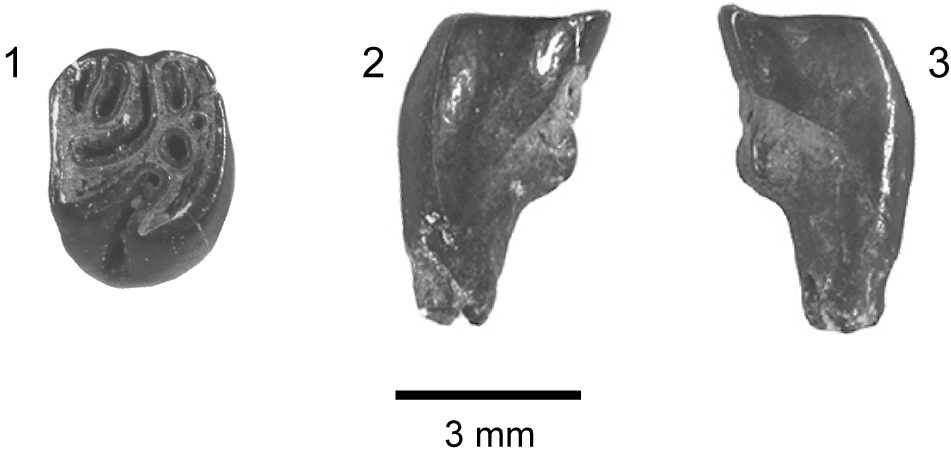

Figure 5. Marsupials, apatemyids, talpoids, lagomorphs, sciurids, aplodontiids, and Eutypomys from the Jones Branch LF, lower Catahoula Formation, Mississippi: (1) Herpetotherium sp., MMNS VP-11645, right m2; (2) ?Sinclairella sp., MMNS VP-6629, left ?dP4; (3) Mesoscalops irwini n. sp., MMNS VP-8239, left m2, (holotype); (4–6) Oligolagus welleri n. gen. n. sp., MMNS VP-6604, left ramal fragment with p4–m1, (holotype); (4) labial view, (5) lingual view, (6) occlusal view; (7) ?Hesperopetes sp., MMNS VP-7715, left m2; (8) Downsimus rainsi n. sp., MMNS VP-7334, right m2, (holotype); (9–18) Eutypomys sp., (9) MMNS VP-7481, left maxilla fragment with M1, (10) MMNS VP-8632, left dP4, (11) MMNS VP-8326, right P3, (12) MMNS VP-8705, right P3, (13) MMNS VP-6943, right P4, (14) MMNS VP-7782, left M1 or M2, (15) MMNS VP-6584, left p4, (16) MMNS VP-7482, left m1, (17) MMNS VP-6945, right m2, (18) SC2013.28.1, left m3.

Referred specimen

MMNS VP-11645, right m2.

Description

MMNS VP-11645, an m2, measures 1.5 mm AP × 1.0 mm TR. The trigonid is higher and slightly narrower transversely than the talonid. The paraconid is broken and missing, but an anterior cingulid is apparent and it extends to the labial surface of the protoconid. The metaconid is worn. The protocristid extends nearly transversely across the crown. The twinned entoconid and hypoconulid are separated by a distinct sulcus, and the somewhat anteroposteriorly compressed entoconid is connected to the posterior surface of the metaconid via an entocristid. A posterior cingulid extends “from the hypoconulid along the posterior wall of the talonid to the base of the crown at the posterobuccal corner of the hypoconid” just as described for lower molars of Herpetotherium by Korth (Reference Korth1994, p. 380). There is no lingual cingulid.

Remarks

Herpetotherium is an extremely long-ranging genus spanning over 30 million years and at least eight NALMAs, from the Uintan through the Barstovian (Korth and Cavin, Reference Korth and Cavin2016). Based on measurements of m2 length, Korth (Reference Korth1994, fig. 2) and Korth and Cavin (Reference Korth and Cavin2016, fig. 5) showed that (1) the Chadronian-aged species, H. marsupium (Troxell, Reference Troxell1923a) and H. valens (Lambe, Reference Lambe1908), were the largest; (2) the late Chadronian specimens of the type species, H. fugax, averaged the smallest; and (3) size somewhat stabilized with a slightly larger m2 in the Orellan through early Arikareean H. fugax (the Arikareean occurrence of the latter was reported by Hayes [Reference Hayes2005, Reference Hayes2007] from Nebraska and Florida) and in another Arikareean species, H. youngi (McGrew, Reference McGrew1937). The later Arikareean Herpetotherium merriami (Stock and Furlong, Reference Stock and Furlong1922) was distinguished from H. youngi and H. fugax by its larger size. The tiny tooth from Jones Branch is similar in size to the small late Chadronian specimens of H. fugax.

Identification of the Jones Branch species is somewhat equivocal because differentiation depends largely on the arrangement, size, and presence/absence of the stylar cusps on the upper molars (e.g., Korth and Cavin, Reference Korth and Cavin2016)—elements not yet recovered from Jones Branch. The Jones Branch tooth is only slightly smaller than m2s from the mid-Arikareean age Brooksville 2 LF (1.56–1.81 mm, n = 3), which, based on the variable stylar cusp morphologies, Hayes (Reference Hayes2005) referred to H. fugax. Herpetotherium sp. cf. H. merriami from Florida’s I-75 LF is much larger than the species from Jones Branch based on measurements in Hayes (Reference Hayes2005). Until upper molars are recovered from Jones Branch, which may shed light on which species is represented, referral beyond Herpetotherium sp. is deferred.

Placentalia Owen, Reference Owen1837

Apatotheria Scott and Jepsen, Reference Scott and Jepsen1936

Apatemyidae Matthew, Reference Matthew1909

Sinclairella Jepsen, Reference Jepsen1934

Referred specimen

MMNS VP-6629, left ?dP4.

Description

MMNS VP-6629 is a small, odd, triangularly shaped tooth, measuring 3.43 mm AP × 2.80 mm TR. Its cap-like morphology, absence of roots, and very slight degree of wear on the principal cusps suggest that it may be deciduous. It has a large, prominent parastyle occupying the anterolabial corner. Between the parastyle and paracone is a weak cingulum. The paracone and metacone are similar in size, larger than the parastyle, slightly transversely compressed, connected by a centrocrista, with a small, shelf-like labial cingulum between them; the paracone is taller than the metacone. The protocone is larger than the paracone and metacone, but not as tall. The peak of the protocone lies directly lingual to the paracone (i.e., it is in line with the paracone transversely). However, rather than cusp-like, the protocone is transversely compressed, forming more of a ridge than a cusp due to a posterolingual extension from its peak that ends at the posterolingual point of the tooth (Fig. 5.2). An anterior cingulum extends from the parastyle along this entire ridge to the posterolingual point of the tooth. Between the paracone and protocone, and anterior to the peaks of those cusps, is a prominent, distinctly isolated, paraconule. There is also a slightly smaller, but similarly prominent metaconule anterolingual to the metacone. The posterior cingulum is broad and shelf-like.

MMNS VP-6629 resembles the M1 of Sinclairella dakotensis Jepsen, Reference Jepsen1934, and S. simplicidens Czaplewski and Morgan, Reference Czaplewski and Morgan2015, in size, in the presence of a prominent parastyle, and in the connection of the paracone and metacone by a centrocrista; but it differs in several other aspects. First, the M1s of Sinclairella are more quadrangular than triangular primarily due to the presence of a hypocone, which is absent in the Jones Branch tooth (see Czaplewski and Morgan, Reference Czaplewski and Morgan2015, fig. 3B). Next, the Jones Branch tooth has a particularly prominent paraconule and metaconule; the M1 of Sinclairella has only a very weak paraconule and no metaconule. And finally, the Jones Branch tooth has a transversely compressed, ridge-like protocone, rather than the typical cusp-like morphology on the M1 of Sinclairella. The tooth’s distinctly triangular shape resembles the M1 of the Uintan-aged Apatemys uintensis (Matthew, Reference Matthew1921) based on a comparison with Matthew (Reference Matthew1921, fig. 2) and Czaplewski and Morgan (Reference Czaplewski and Morgan2015, fig. 4C, redrawn from Matthew, Reference Matthew1921, fig. 2), but it too appears (based on Matthew, Reference Matthew1921, fig. 2) to lack the prominent paraconule and metaconule present in MMNS VP-6629. The tooth in no way resembles the non-molariform, transversely compressed P4 of Sinclairella illustrated by Jepsen (Reference Jepsen1934, pl. 1, fig. 2), Clemens (Reference Clemens1964, fig. 1), and Tornow and Arbor (Reference Tornow and Arbor2017, fig. 6).

Remarks

Apatemyids constitute a unique family of small, rare, purportedly arboreal insectivorous mammals from the Paleogene of Europe and North America thought to have occupied a niche similar to that of the extant lemuroid primate Daubentonia, the aye-aye of Madagascar (e.g., Silcox et al., Reference Silcox, Bloch, Boyer and Houde2010; Czaplewski and Morgan, Reference Czaplewski and Morgan2015). Ranging from the early Tiffanian to early Arikareean in North America, the only member of the family known to have extended into the early Arikareean is Sinclairella. Sinclairella dakotensis is known from the Duchesnean through early early Arikareean of western North America, including Oregon (West, Reference West1973; Cavin and Samuels, Reference Cavin and Samuels2012; Samuels, Reference Samuels2021). A second species, S. simplicidens, was described by Czaplewski and Morgan (Reference Czaplewski and Morgan2015, p. 1) from Florida’s early late Arikareean (Ar3) Buda LF, who concluded that “this late occurrence probably represents a retreat of this subtropically adapted family into the Gulf Coastal Plain subtropical province at the end of the Paleogene and perhaps the end of the apatemyid lineage in North America.”

To the extent that deciduous teeth are unknown for Sinclairella, it still seems reasonable that MMNS VP-6629 is a dP4, given its size and general similarity to M1s of that taxon (and Apatemys uintensis). However, it is equally important to note that the presence on this tooth of such a prominent paraconule and metaconule is anomalous, thus suggesting that the specimen might represent a heretofore unknown, early Arikareean, Gulf Coastal Plain endemic apatemyid; hence the “?” in the taxonomic heading (see Kornicker, Reference Kornicker1979). Although it is possible that the Jones Branch specimen belongs to one of the two species of Sinclairella noted above, only the recovery of additional specimens amenable to such a diagnosis (upper molars of the Jones Branch species or a dP4 of the two known species) can confirm this. Regardless of its identity, the Jones Branch specimen provides only the second Oligocene record of an apatemyid beyond the Great Plains and Oregon, and east of the Mississippi River, and further supports the conclusion reached by Czaplewski and Morgan (Reference Czaplewski and Morgan2015) regarding a late Paleogene Gulf Coastal Plain refugium for this taxon. Figure 4 shows the absence of any record of Sinclairella between Ar1 levels in the Great Plains and Oregon and the later Ar3 occurrence in Florida.

Eulipotyphla Waddell et al., Reference Waddell, Cao, Hauf and Hasegawa1999

Talpoidea Fischer von Waldheim, Reference Fischer von Waldheim1817

Proscalopidae Reed, Reference Reed1961

Mesoscalops Reed, Reference Reed1960

Holotype

MMNS VP-8239, left m2.

Diagnosis

Narrow, V-shaped trigonid and talonid, with talonid slightly wider anteroposteriorly; differs from Proscalops in absence of labial cingulid, absence of accessory cupids at lingual termination of anterior and posterior cingula, absence of lingual invagination of talonid, and smaller size; resembles Mesoscalops in narrow, V-shaped trigonid and talonid, in absence of labial cingulid, absence of accessory cupids at lingual termination of anterior and posterior cingula, and absence of lingual invagination of talonid (= presence of entocristid and metacristid); differs from Mesoscalops scopelotemos K. Reed, Reference Reed1960, and M. montanensis Barnosky, Reference Barnosky1981, in much smaller size (measurements below) and distinct difference in height between trigonid and talonid (trigonid about twice the height of talonid).

Description

Dental terminology follows Barnosky (Reference Barnosky1981, fig. 6). This tiny m2 measures 1.8 mm AP × 1.44 mm TR at the trigonid. Respective measurements for 25 m2s of M. scopelotemos are 2.45–3.05 mm AP × 1.65–2.25 mm TR (K. Reed, Reference Reed1960, table 1) and for one m2 of M. montanensis is 2.8 mm AP × 1.9 mm TR (Barnosky, Reference Barnosky1981). The trigonid is strongly V-shaped and very narrow anteroposteriorly. The talonid is similarly sharply V-shaped, just slightly broader anteroposteriorly than the trigonid, and only half its height. The trigonid and talonid are entirely separate (i.e., the anterior surface of the talonid [the cristid obliqua] does not abut the posterior surface of the trigonid [the protocristid]—it extends all the way lingually, terminating in a metastylid). The paraconid and metaconid are of similar size and there is only a slight, shallow invagination between them; this may be a function of wear. The metaconid and metastylid are worn, but the metastylid is still distinguishable as a separate cusp. The entoconid is the most robust of the lingual cusps, and there is no lingual invagination between it and the metastylid (i.e., the talonid shows no lingual invagination because of the presence of an entocristid and metacristid). When viewed from the posterior aspect, both the trigonid and talonid have been worn into a transversely concave morphology. There is no labial or lingual cingulid, but the anterior and posterior cingula, although not shelf-like, extend along the entire base of the crown. They do not terminate lingually into distinct accessory cuspids. Instead, the lingual termination of both cingula appears as simple, subtle swellings—the posterior swelling (not a true entostylid) slightly more prominent than the anterior.

Etymology

Named for Mr. Kelly J. Irwin, herpetologist with the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, who found MMNS VP-8239 while sorting screen-washed matrix from the Jones Branch site.

Remarks

The Proscalopidae are mole-like eulipotyphlans that were originally considered endemic to the North American northern Great Plains (Barnosky, Reference Barnosky1981) until Geisler (Reference Geisler2004) described four humeri of Oligoscalops from Mongolia. The Jones Branch specimen, therefore, represents the first and only Paleogene talpoid in North America beyond the northern Great Plains, northern Rocky Mountains, and Oregon. Like the true moles (Talpidae), the Proscalopidae have highly specialized adaptations for burrowing (Barnosky, Reference Barnosky1982).

According to Barnosky (Reference Barnosky1981), the Proscalopidae are represented by four genera: the Chadronian Cryptoryctes C. Reed, Reference Reed1954; the Chadronian and Orellan Oligoscalops K. Reed, Reference Reed1961; the Whitneyan and mainly Arikareean Proscalops Matthew, Reference Matthew1901; and the Hemingfordian to early Barstovian Mesoscalops K. Reed, Reference Reed1960. Gunnell et al. (Reference Gunnell, Bown, Hutchison, Bloch, Janis, Gunnell and Uhen2008), however, considered Cryptoryctes a micropternodontid soricomorph—an insectivore group entirely unrelated to Talpoidea. Based on measurements in Gunnell et al. (Reference Gunnell, Bown, Hutchison, Bloch, Janis, Gunnell and Uhen2008), the average length of m2 increases in size, respectively, for Oligoscalops (approx. 2 mm), Proscalops (2.8 mm), and Mesoscalops (approx. 3 mm). The Jones Branch tooth is smaller than any of them (1.8 mm).

Mesoscalops and Proscalops resemble the Jones Branch species in having narrow trigonids and talonids (Macdonald, Reference Macdonald1963; Barnosky, Reference Barnosky1981, Reference Barnosky1982). However, Proscalops differs from Mesoscalops and the Jones Branch species in several traits. First, Mesoscalops and the Jones Branch species lack the deep lingual invagination, particularly on the talonid, seen so prominently in species of Proscalops (e.g., Reed, Reference Reed1961, pl. 1, fig. 4; Barnosky, Reference Barnosky1982, pl. 1, fig. 5) due to the absence of an entocristid and metacristid in Proscalops. The morphology of the anterior and posterior cingula also differs. In Proscalops tertius K. Reed, Reference Reed1961, the anterior and posterior cingula are shelf-like, and both terminate lingually into prominent anterior and posterior accessory cuspids (Hutchison, Reference Hutchison1968, fig. 6). In Proscalops evelynae (Macdonald, Reference Macdonald1963) (based on specimens examined at the UNSM, e.g., UNSM 20500) the anterior cingulid starts about half-way along the anterior surface of the tooth and continues around the anterolingual corner (around the paraconid), and the posterior cingulid is shelf-like. In Mesoscalops and the Jones Branch tooth, the anterior and posterior cingula extend along the entire base of the crown, they do not wrap around onto the lingual surface, they are not shelf-like, and they do not terminate lingually into prominent accessory cuspids.

Mesoscalops irwini n. sp. is similar in size to the mainly Hemingfordian to Barstovian talpid Mystipterus Hall, Reference Hall1930. But the latter has a prominent labial cingulid, the trigonid and talonid are wider anteroposteriorly than in the Jones Branch species, and they are not entirely separate (i.e., the cristid obliqua [or entocristid] abuts the posterior surface of the trigonid [the protocristid], whereas in Mesoscalops irwini n. sp., it extends all the way lingually, terminating in a metastylid) (see Hutchison, Reference Hutchison1968, fig. 20; Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen1977). Another talpid, Mioscalops Ostrander et al., Reference Ostrander, Mebrate and Wilson1960 (previously Scalopoides Wilson, Reference Wilson1960, but see Korth and Evander, Reference Korth and Evander2016) resembles the Jones Branch species in having a cristid obliqua that extends lingually to a metastylid, but differs in its larger size, in having a prominent labial cingulid, and anterior and posterior cingula with accessory cuspids at their lingual termination (Hutchison, Reference Hutchison1968).

Although Mesoscalops is known primarily from the Hemingfordian to Barstovian of Montana, Wyoming, and South Dakota (Barnosky, Reference Barnosky1981), the Jones Branch species much more closely resembles that taxon than the mainly Arikareean Proscalops. This older age of the Jones Branch species does not, however, preclude assignment to Mesoscalops. As Barnosky (Reference Barnosky1981, p. 330) concluded, Mesoscalops was “most closely related either to a P[roscalops] miocaenus-like form or P. tertius, both Whitneyan species.” It is hoped that additional screening of matrix from the Jones Branch site will eventually yield further remains of this talpoid, in turn providing a more detailed assessment of its affinities with the known species from the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains regions.

Lagomorpha Brandt, Reference Brandt1855

Oligolagus new genus

Type species

Oligolagus welleri new genus new species

Diagnosis

As for species.

Etymology

See below.

Holotype

MMNS VP-6604, left ramal fragment with p4–m1.

Diagnosis

Small size; non-rooted, ever-growing, high-crowned lower cheek teeth; prominent lingual and labial reentrants extend along entire length of teeth with minimal cement; no “lingual bridge” (Dawson, Reference Dawson1958) as seen in Palaeolagus haydeni Leidy, Reference Leidy1856, P. philoi Dawson, Reference Dawson1958, and P. hemirhizis Korth and Hageman, Reference Korth and Hageman1988 (note: Prothero and Whittlesey [Reference Prothero, Whittlesey, Terry, LaGarry and Hunt1998, p. 50] suggested that P. hemirhizis is more likely an “artificial construct of two different species [P. temnodon Douglass, Reference Douglass1902, and P. haydeni] …. lumped together…”); enamel of lingual surface of talonid abuts posterior surface of trigonid slightly labial to its lingual-most point (resulting in prominent lingual reentrant); trigonid and talonid joined by cement; thick enamel with thinning apparent only along lingual half of anterior surface of trigonid; no crenulations on posterior edge of trigonid or anterior edge of talonid; no posterolophid.

Differs from Oligocene ochotonids (e.g., Desmatolagus dicei Burke, Reference Burke1936, and D. gazini Burke, Reference Burke1936, but note that Fostowicz-Frelik and Meng, Reference Fostowicz-Frelik and Meng2013, considered Desmatolagus a paraphyletic stem group of lagomorphs) in absence of rooted cheek teeth (Burke, Reference Burke1936; Dawson, Reference Dawson1965; Erbajeva, Reference Erbajeva, Tomida, Li and Setoguchi1994); differs from Megalagus Walker, Reference Walker1931, in much smaller size and absence of low-crowned, rooted cheek teeth; differs from Archaeolagus Dice, Reference Dice1917, in having prominent lingual reentrant between trigonid and talonid along entire length of tooth and in absence of lingual bridge; smaller than Palaeolagus intermedius Matthew, Reference Matthew1899, and P. philoi; similar in size to P. haydeni, P. hypsodus Schlaikjer, Reference Schlaikjer1935, and P. burkei Wood, Reference Wood1940; differs from P. haydeni (abundantly represented in the Brule Formation) in the absence of the prominent, anteroposteriorly extending swelling seen low on the lingual surface of the ramus below the p3–m1 into which the posterior portion of the incisor resides and in the anteriormost point of the V-shaped masseteric fossa. In P. haydeni, it extends to a point between m1 and m2, whereas in Oligolagus welleri n. gen. n. sp. it extends slightly farther forward, to a point even with the talonid of m1. The Chadronian-aged Chadrolagus Gawne, Reference Gawne1978, Limitolagus Fostowicz-Frelik, Reference Fostowicz-Frelik2013, and the rare early Orellan-aged Litolagus Gawne, Reference Gawne1978, all have prominent lingual bridges that develop in early wear stages (Fostowicz-Frelik, Reference Fostowicz-Frelik2013).

Description

The teeth in MMNS VP-6604 are considered to be the p4 and m1 based on the opposing angles they show as they extend down into the jaw fragment (Fig. 5.4; also see Wolniewicz and Fostowicz-Frelik, Reference Wolniewicz and Fostowicz-Frelik2021, fig. 12H) and on comparisons with numerous specimens of P. haydeni from the Brule Formation. The p4 of MMNS VP-6604 measures 2.3 mm AP × 2.1 mm TR (max); m1 measures 2.4 mm AP × 2.2 mm TR (max). A break in the lower part of the lingual surface of the dentary shows that they are non-rooted and apparently ever-growing, resulting in their very high-crowned morphology. The trigonid is higher than the talonid, and the two columns are joined by cement; but there is very little cement in the prominent reentrants, both lingual and labial, that separate the trigonid from the talonid, especially for teeth this high-crowned, compared with species of Palaeolagus. The enamel on both teeth is thick with little thinning anywhere around the tooth except along the lingual half of the anterior surface of the trigonid. Although there is an enamel connection lingually between the talonid and trigonid, it does not form the lingual bridge resulting from wear noted by Dawson (Reference Dawson1958), and particularly characteristic of P. hemirhizis, P. haydeni, and P. philoi, due in large part to the paucity of cement in the lingual reentrant. In Palaeolagus, once the lingual bridge forms, all evidence of a lingual reentrant is lost. In Oligolagus welleri n. gen. n. sp., the lingual reentrant extends along the entire length of the tooth due, in part, to the nature of the lingual trigonid–talonid connection (the enamel of the lingual surface of the talonid connects to, or abuts, the posterior surface of the trigonid slightly labial to its lingual-most point) and to the minimal amount of cement in the lingual reentrant, as noted above (Fig. 5.5). There are no crenulations on the posterior edge of the trigonid or anterior edge of the talonid, and the teeth show no posterolophid.

Etymology

Named for the Oligocene age of the Jones Branch LF and for Andy Weller of Waynesboro, MS, who discovered the Jones Branch site, who alerted GEP to its fossils, and who donated numerous specimens utilized in this study, including this one.

Remarks

Dawson (Reference Dawson, Janis, Gunnell and Uhen2008) recognized the two traditional families of North American lagomorphs, the Leporidae and the Ochotonidae, and in her figure 17.4 she showed three leporid genera spanning the early Arikareean: Palaeolagus, Megalagus, and Archaeolagus. More recent analysis based on detailed study of the cranial morphology has found that Palaeolagus (specifically P. haydeni) shares a mixture of characters associated with both leporids and ochotonids, thus supporting its phylogenetic status as a stem lagomorph (e.g., Wolniewicz and Fostowicz-Frelik, Reference Wolniewicz and Fostowicz-Frelik2021). Megalagus, also considered a stem lagomorph by Fostowicz-Frelik and Meng (Reference Fostowicz-Frelik and Meng2013), is larger than Oligolagus welleri n. gen. n. sp. with lower crowned, rooted teeth. Archaeolagus differs from O. welleri in having the development of the enamel bridge that connects the trigonid and talonid lingually, and in having the typical leporid enamel pattern in which it is thicker labially than lingually, thin to absent lingually, and often absent on the anterior surface of the trigonid and posterior surface of the talonid.

Several species of Palaeolagus, a long ranging group known primarily from the Chadronian through Arikareean of the Great Plains (Dawson, Reference Dawson1958; Emry and Gawne, Reference Emry and Gawne1986; Korth and Hageman, Reference Korth and Hageman1988), have been described, including the Chadronian-aged P. temnodon and P. primus Emry and Gawne, Reference Emry and Gawne1986, the early Orellan-aged P. hemirhizis (but see note above regarding the validity of this taxon), the common late Orellan–early Whitneyan-aged P. haydeni, the late Orellan–Whitneyan-aged P. intermedius and P. burkei, and the early Arikareean-aged P. hypsodus and P. philoi. Palaeolagus hypsodus and P. philoi are known from deposits considered “approximately equivalent to Gering-Monroe Creek beds of Nebraska” according to Dawson (Reference Dawson1958, p. 29), and Bailey (Reference Bailey2004) noted both species from the Ar1-aged Ridgeview LF, Nebraska, as did Hayes (Reference Hayes2007) from the Wagner Quarry LF.

Oligolagus welleri n. gen. n. sp. is similar in size to P. hypsodus, and both lack the lingual bridge trigonid–talonid connection—a feature present in and characteristic of P. temnodon, P. haydeni, P. hemirhizis, P. intermedius, and P. philoi, in which the enamel on the lingual surfaces of the trigonid and talonid merge upon wear. Palaeolagus burkei also lacks the lingual bridge, and together with P. hypsodus comprise Dawson’s (Reference Dawson1958) “P. burkei group” in which the trigonid and talonid are united “solely by cement during most of life” and which have inflated auditory bullae relative to the other species (Dawson, Reference Dawson1958, p. 19; Dawson, Reference Dawson, Janis, Gunnell and Uhen2008; Fostowicz-Frelik, Reference Fostowicz-Frelik2013).

Oligolagus welleri n. gen. n. sp. differs from P. hypsodus in showing generally thicker enamel and thinning enamel only on the lingual portion of the anterior surface of the trigonid. Palaeolagus hypsodus and P. philoi lack enamel on the anterior surface of the trigonid, but the former also lacks enamel on the lingual surface of the trigonid and talonid (Dawson, Reference Dawson1958). Oligolagus welleri n. gen. n. sp. differs from P. philoi in slightly smaller size, in its absence of a posterolophid, and in the absence of enamel crenulations on the anterior wall of the talonid (Dawson, Reference Dawson1958).

The thick enamel on the teeth of the Jones Branch specimen, the degree of hypsodonty, the nature of the talonid–trigonid lingual connection, the prominent lingual reentrant and paucity of cement within resulting in the absence of a lingual bridge even upon wear, the absence of ventro-medial swelling along the ramus for the posterior incisor, and the anterior extension of the ridge of the masseteric fossa to the m1 preclude referral of the Jones Branch species to Palaeolagus, and support its referral to a genus other than those known from the Arikareean of the Midcontinent. Although additional material, particularly the p3 and upper cheek teeth, would help support this, the presence of a previously unknown genus in the Gulf Coastal Plain seems reasonable given the different paleoecological setting that existed there relative to that of the Midcontinent during mid-Oligocene time.

Rodentia Bowdich, Reference Bowdich1821

Sciuridae Fischer de Waldheim, Reference Fischer von Waldheim1817

Hesperopetes Emry and Korth, Reference Emry and Korth2007

Type species

Hesperopetes thoringtoni Emry and Korth, Reference Emry and Korth2007.

?Hesperopetes sp.

Referred specimens

MMNS VP-7539, left p4; MMNS VP-7715, left m2.

Description

The p4, MMNS VP-7539, measures 1.98 mm AP × 1.71 mm TR. The metaconid and hypoconid are the largest cusps, the protoconid is nearly the size of the metaconid, and the entoconid is the smallest; but all are highly worn. The wear of the metaconid and protoconid precludes a determination as to the nature of the trigonid and to metalophulids I and II (tooth morphology follows Bell, Reference Bell2004). The small but prominent mesostylid is connected to the posterior surface of the metaconid, but entirely separated from the entoconid. There is also a worn mesoconid between the protoconid and hypoconid. The crenulations of the talonid are also worn to the extent that they are nearly indistinguishable relative to those of the better preserved m2, MMNS VP-7715.

The m2, which measures 2.04 mm AP × 2.19 mm TR, is parallelogram-shaped, with four robust cuspids and two long, prominent roots (Fig. 5.7). The anterolingually located metaconid is the largest, highest, and most prominent cusp and slightly anterior to the protoconid. Extending labially from the metaconid, and forming the anterior margin of the tooth, is a lophid, likely metalophulid I; but there is no metalophulid II. In other described species of Hesperopetes (and Sciurion), there is typically a small, oval, trigonid basin enclosed between the metalophulid I and II (see below). This anterior lophid does not connect to the protoconid; instead, it terminates labially as a small, subtle cuspid that might be considered an anteroconid. This cuspid-like structure is appressed to, but distinctly separate from, the anterior surface of the protoconid. The protoconid and posterolabially located hypoconid are similar in size, and between them is a small, but distinct mesoconid, which is more closely appressed to the hypoconid than to the protoconid. A prominent, arcuate posterolophid connects the hypoconid to the posterolingually located entoconid. Between the entoconid and the metaconid is a small mesostylid more distinctly separated from the entoconid than from the metaconid. The talonid basin is crenulated.

Remarks

Hesperopetes Emry and Korth, Reference Emry and Korth2007, and Sciurion Skwara, Reference Skwara1986, are small, rare “flying squirrels” with crenulated enamel on the surfaces of the cheek teeth and heretofore known primarily from the northern Great Plains, although Sciurion has also been reported from the Cabbage Patch beds within the Rocky Mountains of Montana (Calede, Reference Calede2020). Originally, three species of Hesperopetes were described, H. thoringtoni, H. jamesi Emry and Korth, Reference Emry and Korth2007, and H. blacki Emry and Korth, Reference Emry and Korth2007, ranging from the Chadronian of Wyoming, the Orellan of Nebraska, through the Whitneyan of North and South Dakota and Saskatchewan (Korth, Reference Korth2017; Korth et al., Reference Korth, Emry, Boyd and Person2019; Bell et al., Reference Bell, Meyer and Storer2023). Recent work by Bell et al. (Reference Bell, Meyer and Storer2023) resulted in reassignment of H. jamesi and H. blacki to Sciurion, thus Sciurion jamesi (Emry and Korth, Reference Emry and Korth2007) and S. blacki (Emry and Korth, Reference Emry and Korth2007).

Bell et al., Reference Bell, Meyer and Storer2023, additionally described two new species from the Orellan of Saskatchewan, S. oligcaenicus Bell, Meyer, and Storer, Reference Bell, Meyer and Storer2023, and S. ikimekooyensis Bell, Meyer, and Storer, Reference Bell, Meyer and Storer2023, as well as a new species of Hesperopetes, H. mccorquodalei Bell, Meyer, and Storer, Reference Bell, Meyer and Storer2023, from material originally referred by Storer (Reference Storer2002) to Nototamias and Protosciurus from the early Arikareean Kealy Springs LF. According to Bell et al. (Reference Bell, Meyer and Storer2023, p. 87; also see Korth, Reference Korth2009a), Sciurion has an open trigonid basin, an anteroconid, and a distinct mesostylid separated from the entoconid, whereas Hesperopetes has “consistently more robust and rounded features,” the absence of an anteroconid (in the type species), and “a mesostylid confluent with the entoconid.” Contrasting with this characterization, however, Bell et al. (Reference Bell, Meyer and Storer2023, p. 92) described the p4 of H. mccorquodalei as having a mesostylid “separated from the entoconid and weakly connected to the metaconid,” and m1 or m2 with a “small, rounded trigonid basin.”

The sciurid teeth from Jones Branch differ somewhat from those described from the more northern localities, primarily in their larger size (although a single M3 from the Orellan of Nebraska referred to Hesperopetes sp. [CM89325] by Korth, Reference Korth2017, is of similar size) and in the structure of the anterior lophid of the m2 (absence of metalophulid II and the consequent absence of an enclosed trigonid basin). But they also share features with both Sciurion and Hesperopetes. Like Sciurion, the m2 has an anteroconid and a distinct mesostylid separated from the entoconid; but like Hesperopetes, it has more robust and rounded cusps. Of these two genera, apparently only Hesperopetes ranges into the Arikareean as H. mccorquodalei.

Until further material is collected from Jones Branch, we provisionally refer these teeth to Hesperopetes. Although assignment to Sciurion is not inadmissible, it would represent a temporal (and geographic) range extension for the genus. The presence of Hesperopetes (or Sciurion) in the Jones Branch LF represents the only known Paleogene record of a “flying squirrel” beyond the Great Plains and northern Rocky Mountains region, although Pratt and Morgan (Reference Pratt and Morgan1989) reported Petauristodon from the Neogene (Hemingfordian) of Florida. The Jones Branch record provides further documentation of the faunal link between the Midcontinent and the Gulf Coastal Plain during the Oligocene.

Aplodontiidae Brandt, Reference Brandt1855

Downsimus Macdonald, Reference Macdonald1970

Holotype

MMNS VP-7334, right m2.

Diagnosis

Differs from the type species, Downsimus chadwicki Macdonald, Reference Macdonald1970, and D. montanus Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen1977, from Montana, in smaller size, more labially shifted metaconid, much less prominent mesostylid, less robust principal cuspids, absence of lophid extending anteriorly from hypoconulid, and more circular posterior labial fossettid; differs from Haplomys in smaller size, in having a labially shifted metaconid, in lacking a hypolophid and a triangularly shaped hypoconulid and mesoconid, and in having a circular and enclosed posterior fossettid versus a transversely elongate and often open one; differs from Disallomys (originally Allomys storeri Tedrow and Korth, Reference Tedrow and Korth1997; see also Korth, Reference Korth2009b, and discussion below) in its smaller size, more nearly rectangular occlusal shape versus the “parallelogram” shape of Disallomys (Tedrow and Korth, Reference Tedrow and Korth1997, p. 87), in having a labially shifted metaconid versus the anteroposteriorly compressed metaconid positioned at the antero-lingual corner of the tooth in Disallomys, in its diminutive mesostylid and absence of a metastylid crest, in its absence of a hypolophid, and in having a round versus transversely elongate-shaped posterior labial fossettid; differs from Ansomys, Allomys, and Parallomys in its smaller size, in lacking a prominent, blade-like metastylid crest, in lacking an antero-posteriorly compressed hypoconulid, and in lacking a prominent hypolophid and other internal crests.

Description

Aplodontiid tooth morphology follows Bell (Reference Bell2004). This single, small lower molar measures 1.72 mm AP × 1.44 mm TR, somewhat smaller than the m2 of the genoholotype, LACM 17031, at 1.90 mm × 1.70 mm, and that of LACM 9374, at 2.03 mm × 1.50 mm (Macdonald, Reference Macdonald1970). Downsimus montanus is also larger; two m2s measure 2.33 mm and 2.06 mm AP × 1.93 mm and 1.88 mm TR, respectively (Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen1977, table 13). The metaconid is the largest cusp, occupying the entire anterolingual corner of the tooth, but extending labially approximately half-way across the anterior surface (i.e., the peak of the cusp is not at the antero-lingual corner but has been shifted labially). There is a short anterior cingulid (metalophulid I) between the metaconid and protoconid, and a small, but distinct protrusion on its anterior surface. This protrusion is not an anteroconid, because it is not within the anterior cingulid—it is anterior to the metalophulid I on the anterior surface of the tooth. It may be the structure that Rensberger (Reference Rensberger1975, p. 9) referred to as “a cingulid on the anterior face of the protoconid” as well as what Korth (Reference Korth1989, p. 401) noted as “a basal anterior cingulid below the protoconid.” Based on examination of two p4s assigned to Downsimus from UNSM locality Dw-121 (UNSM 48505 and 48512), the site from which the Ridgeview LF is derived (Bailey, Reference Bailey2004), this protrusion appears to be what was originally a paraconid. Posterior to the metaconid, and at a level just slightly posterior to the peak of the protoconid, is a low, diminutive, barely noticeable mesostylid (Fig. 5.8); too small, in fact, to result in the prominent metastylid crest that forms upon wear and merger of the metaconid and mesostylid so diagnostic of Allomys (including “Alwoodia,” see Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2008) and Parallomys.

The entoconid, a bit smaller than the protoconid, is positioned slightly anterior to the posterolingual corner of the tooth. It is connected to a prominent, but smaller, very slightly anteroposteriorly compressed hypoconulid by a small, subtle, cingular segment; but this cingulid is not so prominent as to block an open inflection between these two cusps. There is a small, short, subdued lophid extending anteriorly from the labial portion of the hypoconulid, but there is no hypolophid so prominent in most other aplodontiids. Another cingular segment (the posterior cingulid or posterolophid) connects the hypoconulid to the slightly larger hypoconid located at the posterolabial corner of the tooth and situated well posterior to the entoconid. Extending anteriorly from the hypoconid are two lophids, one anterolingually and one anterolabially, that connect to the mesoconid, but which also enclose the prominent circular fossettid that lies between the hypoconid and mesoconid (the “posterior labial fossettid” of Rensberger, Reference Rensberger1983, fig. 2, and “posterior buccal fossettid” of Bell, Reference Bell2004, fig. 5.2). The valley between the fossettid and the protoconid is blocked from the interior basin by the mesoconid.

Etymology

Named for Roger Rains of Waynesboro, MS, who, together with Andy Weller, collected and made available to the MMNS so many of the specimens reported herein.

Remarks

The tooth of Downsimus rainsi n. sp. with its brachydont crown height, absence of prominent internal crests or lophids (particularly the hypolophid), and diminutive mesostylid with a consequent absence of a metastylid crest, appears less derived than those of other aplodontiids, such as Haplomys, Ansomys, Allomys, Disallomys, or Parallomys. In these features and others, it most closely resembles Downsimus chadwicki Macdonald, Reference Macdonald1970, and Allomys sharpi Macdonald, Reference Macdonald1970, from the Ar1-aged Sharps Formation of South Dakota and D. montanus from the early Arikareean-aged lower Cabbage Patch beds (Renova Formation) of Montana (Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen1977; Calede, Reference Calede2020). Allomys sharpi, however, was excluded from that genus by Rensberger (Reference Rensberger1975, Reference Rensberger1983), who considered this species likely congeneric with Downsimus, then later reassigned by Storer (Reference Storer2002) to Downsimus chadwicki on the basis of several specimens from the Ar2 Kealey Springs LF, Saskatchewan. Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2008) also considered Allomys sharpi congeneric with Downsimus, with a consequent referral of the Sharps material to Downsimus sharpi. Downsimus is also recorded from the (late?) Whitneyan-aged Blue Ash LF of South Dakota (Korth, Reference Korth2009b, Reference Korth2010) and the Ar1-aged Ridgeview and Wagner Quarry local faunas, Nebraska (Bailey, Reference Bailey2004; Hayes, Reference Hayes2007, respectively).

Noted in Macdonald’s (Reference Macdonald1970) description of specimens of D. chadwicki (including Allomys sharpi) is the presence of a distinctive mesostylid. Of the m2, he stated “mesostylid larger [than on m1], partially separated from metaconid by notch” (Macdonald, Reference Macdonald1970, p. 29). Several teeth assigned to Downsimus from UNSM locality Dw-121, the site from which the Ridgeview LF is derived (Bailey, Reference Bailey2004), match this description, suggesting that the specimens from Nebraska may be referrable to D. chadwicki. This is further supported by the matching age and geographic proximity of site Dw-121 and Macdonald’s (Reference Macdonald1970) Sharps Formation localities. The specimen from Jones Branch, as noted previously, represents a slightly smaller species with a much smaller, more subtle mesostylid, supporting referral to the new species D. rainsi.

Variably and questionably considered a prosciurine (Macdonald, Reference Macdonald1970; Korth, Reference Korth1989, Reference Korth2009b) or an allomyine (Rensberger, Reference Rensberger1975), the subfamily to which Downsimus belongs is still unresolved. Rensberger (Reference Rensberger1983, p. 35) noted that Downsimus (and ‘Allomys’ sharpi) “were probably not members of a lineage leading toward the allomyines.” Similarly, Storer (Reference Storer2002, p. 112) concluded that Downsimus could not be assigned to the Prosciurinae or the Allomyinae. Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2008, p. 784, 785, 789, 792) considered the Prosciurinae a paraphyletic group encompassing “the species at the base of the aplodontiid radiation,” but noted that Downsimus apparently constitutes a monophyletic clade “placed either just before or just after the divergence of Ansomys” (species of which she placed in a monophyletic Ansomyinae; also see Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2004).

Morphologically the tooth from Jones Branch is less derived than those of any described species of Allomys in its near absence of prominent internal crests or lophids and in the absence of a metastylid crest that forms upon wear and merger of the metaconid and mesostylid. The internal crests of the Jones Branch tooth include only a short, poorly developed lophid off the entoconid that trends posteriorly toward (but not connecting with) the small poorly developed lophid extending anteriorly from the labial portion of the hypoconulid noted above; but there is no true hypolophid between the entoconid and mesoconid seen so prominently in nearly every other species, nor is there a prominent crest extending anteriorly from the hypoconulid, a defining character for Allomys according to Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2008).

Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2008) considered the following species as members of a monophyletic Allomys: A. nitens Marsh, Reference Marsh1877; A. simplicidens Rensberger, Reference Rensberger1983; A. reticulatus Rensberger, Reference Rensberger1983; A. tessellatus Rensberger, Reference Rensberger1983; A. magnus (Rensberger, Reference Rensberger1983); A. harkseni Macdonald, Reference Macdonald1963; and the poorly known A. cristabrevis Barnosky, Reference Barnosky1986—all but the latter two are from various levels within the John Day Formation, Oregon (Rensberger, Reference Rensberger1983). Allomys harkseni is known from the Monroe Creek Formation of South Dakota (R. Macdonald, Reference Macdonald1963, Reference Macdonald1970; L. Macdonald, Reference Macdonald1972) and the Harrison Formation of Nebraska (Korth, Reference Korth1992); A. cristabrevis from the early Arikareean Emerald Lake Fauna, Colter Formation, Jackson Hole, Wyoming (Barnosky, Reference Barnosky1986). All are larger than D. rainsi n. sp., and they have a highly complex occlusal morphology due to “extensive development of accessory crests” (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2008, p. 790), including the prominent metastylid crest, hypolophid, and anterior extension off the hypoconulid. The same is true for A. stirtoni Klingener, Reference Klingener1968, from the Barstovian-age Norden Bridge LF, Valentine Formation, Nebraska, which, together with Allomys cavatus (Cope, Reference Cope1881a), Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2008) placed in a paraphyletic “Parallomys.”

Allomys storeri, considered ancestral “to all later North American allomyines” by Tedrow and Korth (Reference Tedrow and Korth1997, p. 87) on the basis of its Whitneyan age and on its less-derived morphology, was placed outside the Allomyinae by Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2008) and within a putative monophyletic Ansomyinae. She did not, however, reassign the species to Ansomys, noting that it was “distinct enough from the species previously placed in Ansomys by Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2004) to merit a genus of its own” (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2008, p. 793). Korth (Reference Korth2009b) apparently agreed with Hopkins’ (2008) assessment and, citing several features distinguishing it from Ansomys, erected Disallomys within the subfamily Prosciurinae for the species—hence Disallomys storeri. The lower molar of the Jones Branch species differs from those of D. storeri in several features including: (1) its smaller size; (2) its more nearly rectangular shape versus the “parallelogram” shape in Disallomys; (3) having a metaconid that is not anteroposteriorly compressed and that has been shifted somewhat labially versus a position at the antero-lingual corner of the tooth; (4) its diminutive mesostylid; (5) its lack of a hypolophid; and (6) having a round versus transversely elongate-shaped posterior labial fossettid.

The appearance of Downsimus in the Jones Branch LF, a form previously known only from the Great Plains and northern Rocky Mountains regions, provides the first record of a North American aplodontiid in the southeastern United States.

Eutypomyidae Miller and Gidley, Reference Miller and Gidley1918

Eutypomys Matthew, Reference Matthew1905

Referred specimens

MMNS VP-8319, left P3; MMNS VP-8326, right P3; MMNS VP-8705, right P3; MMNS VP-8632, left dP4; MMNS VP-6943, right ?P4; MMNS VP-7480, right maxilla fragment with M1–2; MMNS VP-7481, left maxilla fragment with M1; MMNS VP-7782, left M1 or M2; MMNS VP-6584, left p4; MMNS VP-7482, left m1; MMNS VP-6945, right m2; MMNS VP-7283, left m3; SC2013.28.1, left m3.

Description

The dP4 (MMNS VP-8632) is similar to P4 and M1, but much smaller (Fig. 5.10; Table 1), and it closely resembles the dP4 illustrated for E. parvus by Kihm (Reference Kihm2011, fig. 1). As in the P4, there is no labial valley between the metacone and posterior cingulum. The labial terminus of the posterior cingulum joins the posterior surface of the metacone; the M1 has a prominent valley separating the posterior cingulum from the metacone. The valley between the labial terminus of the anterior cingulum and the paracone is narrow relative to that of M1s. There is a small but prominent style anterior to the mesostyle and appressed to the posterior surface of the paracone.

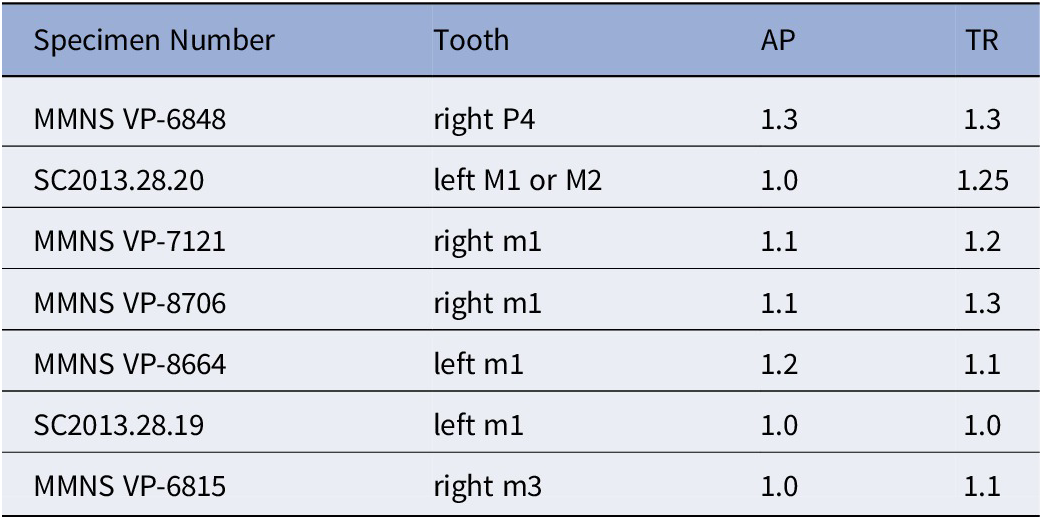

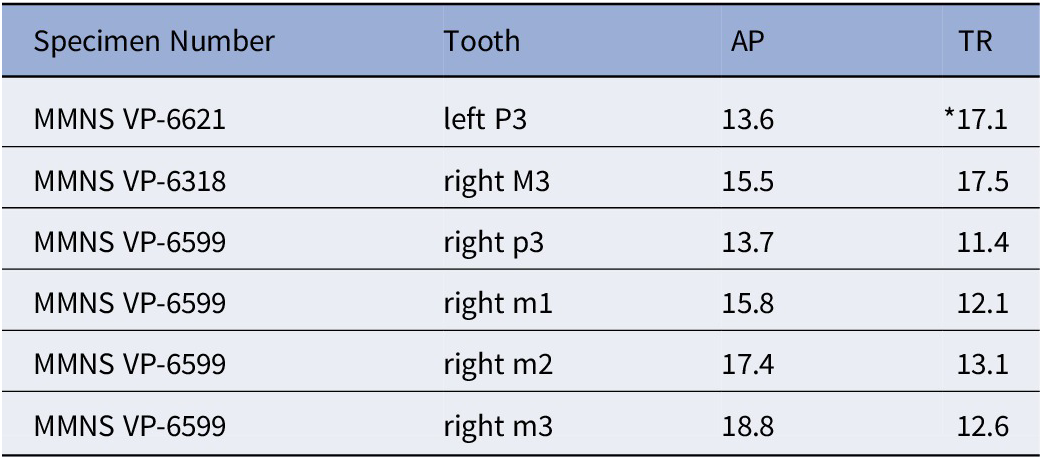

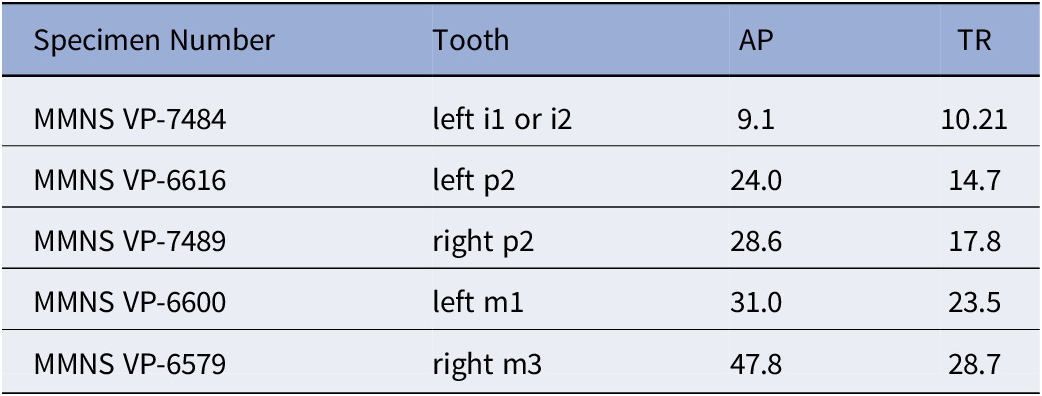

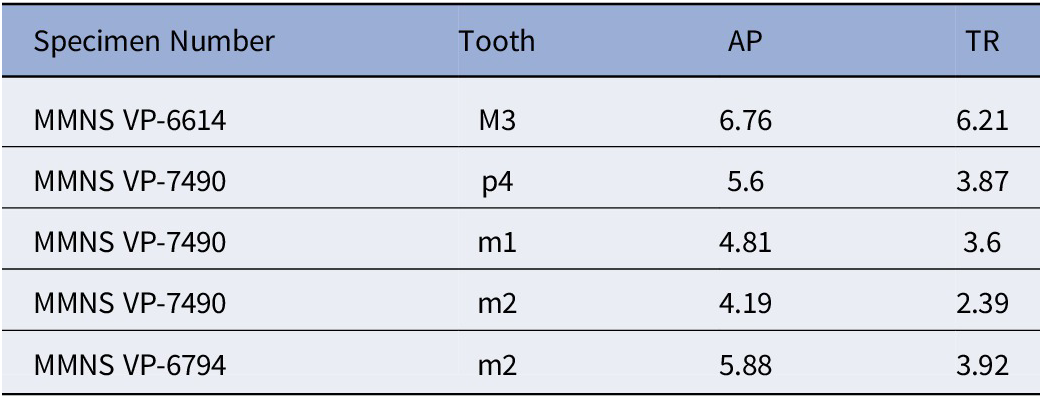

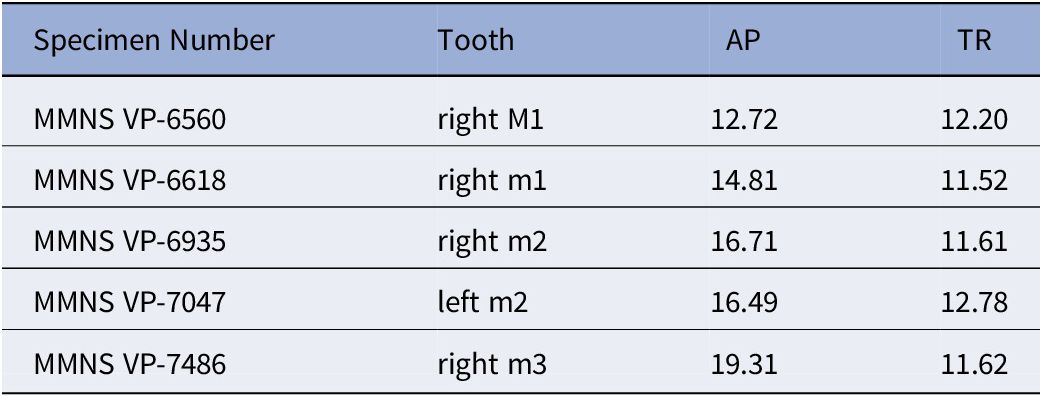

Table 1. Measurements of teeth (in mm) of Eutypomys sp.

The P3s are identified as such on the basis of their matching resemblance to specimens of Eutypomys from Florida’s I-75 LF labeled as P3s (UF 209963, UF 209964, UF 209965), although the I-75 specimens are smaller. P3s are much smaller than the P4s–M2s (Table 1), and they show only a single prominent cusp, here considered the paracone, in an antero-labial position (Fig. 5.11, 5.12). MMNS VP-6943, thought to be a P4, is distinctly elongate anteroposteriorly and shows unilateral hypsodonty, but not nearly to the extent seen in the castorid Microtheriomys brevirhinus Korth and Samuels, Reference Korth and Samuels2015. The elongation and unilateral hypsodonty are traits not seen in other species of Eutypomys, nor in other teeth of this species from Jones Branch. The anterior cingulum, or anteroloph, is widely separated from the paracone by a prominent labial valley that extends approximately halfway across the occlusal surface (Fig. 5.13). At the stage of wear of MMNS VP-6943, there are four enamel lakes, or fossettes, within the anteroloph, and another larger fossette immediately lingual to the valley separating the anteroloph from the paracone. The paracone is slightly anterior to the protocone. Labial to the anterolabially angled lingual valley (the hypoflexus; terminology follows Wu et al., Reference Wu, Meng, Ye and Ni2004) that separates the protocone from the hypocone is a prominent enamel lake, larger than the four anterior to it. Extending lingually from the labial surface of the tooth toward the hypoflexus is a narrow mesoflexus, and between it and the hypoflexus is a mure (= endoloph of Wu et al., Reference Wu, Meng, Ye and Ni2004, fig. 1) that connects the anterior and posterior parts of the tooth. The mesoflexus separates the paracone from the mesostyle, which is found at the labial termination of a mesoloph that originates from the posterior portion of the mure. The mesostyle and mesoloph are entirely isolated from the paracone and metacone by the mesoflexus anteriorly and by a postmesoflexus posteriorly. Between the mesoflexus and the paracone are two prominent fossettes in line with and labial to the prominent fossette noted above anterolabial to the hypoflexus. The mesoloph is parallel to the anterior and posterior surfaces of the tooth. There is no metaloph to connect the hypocone to the metacone, and there is no labial valley separating the metacone from the posterior cingulum. The labial terminus of the posterior cingulum joins the posterior surface of the metacone.