1. Introduction

Uncertainty spikes such as the 2008 financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine have led to protectionist reactions in many countries (Evenett, Reference Evenett2019). Instead of raising the impetus for international cooperation, heightened uncertainty can amplify calls for unilateral measures to protect national interests and buffer against negative international spillovers (Bagwell and Staiger, Reference Bagwell and Staiger2002). As a result, governments often seem reluctant to enter international institutions that may constrain their sovereignty further when faced with uncertainty. However, in the case of preferential trade agreements (PTAs), evidence suggests that, in fact, uncertainty may lead governments to sign into deeper international commitments. For instance, at the end of 2008, Japan and Vietnam signed a comprehensive PTA in a time marked by high economic uncertainty for both countries, with Japan suffering from a severe negative trade shock and Vietnam struggling with mounting inflation, twin deficits, and rising unemployment. Similarly, China and Costa Rica signed a comprehensive trade and investment agreement in April 2010 after the election of a new president in the Latin American country who had pledged to constrain significantly the operations of international mining corporations. In 2015, Turkey signed a deep PTA with Singapore while facing significant economic and political uncertainty caused by capital outflows, weakening export markets, failed attempts to form a new government, and a number of terrorist attacks. It is unsurprising that governments may sign PTAs during times of economic or political hardship to appeal to voters (Mansfield and Milner, Reference Mansfield and Milner2018). Yet, it is puzzling that the agreements they sign contain an exceptionally large number of hand-tying provisions.

Existing literature on the rational design of international institutions has pointed out how uncertainty positively predicts countries’ resort to institutional flexibility. The latter allows governments to deviate from specific commitments to meet contingent domestic demands while preserving overall compliance (Rosendorff and Milner, Reference Rosendorff and Milner2001; Koremenos, Reference Koremenos2005). In PTAs, prominent flexibility provisions include escape options such as antidumping and countervailing duties. Yet, the evidence above suggests that when countries are exposed to sharp rises in uncertainty,Footnote 1 rather than increasing flexibility, they seek to maximize institutional depth, that is the number and stringency of liberalization commitments international agreements contain. By providing information and legal certainty through provisions on the protection of investment, intellectual property rights (IPRs), domestic competition rules, and regulatory cooperation, deep PTAs can act as important uncertainty-mitigating tools in addition to liberalizing trade (Mansfield and Reinhardt, Reference Mansfield and Reinhardt2008). Thus, it is not clear whether governments would sign deeper or more flexible agreements when faced with uncertainty. In this light, this paper seeks to answer the following question: What are the effects of uncertainty spikes on the design of PTAs?

We argue that, rather than entailing more flexibility provisions, PTAs signed after dramatic increases in uncertainty are on average deeper, containing stronger institutional commitments. Sharp rises in uncertainty can alter the regular modes in which political actors operate and shape international institutions. Following Koremenos, Lipson, and Snidal, we understand uncertainty as ‘the extent to which actors are not fully informed about others’ behavior [and] the state of the world’ (2001, 778). During PTA negotiations, we specifically understand uncertainty as a private actors’ lack of reliable information about the present or future policies of negotiating governments that could impact their economic interests. As countries experience unforeseen events, such as economic downturns, political crises, coups, pandemics, or natural calamities, the uncertainty experienced by firms about the policies that governments might adopt increases. In this context, PTAs can act as important uncertainty-mitigating tools as they establish obligations for governments and enhance the predictability of their actions. For example, governments bound by stronger PTA obligations towards investment protection, or regulatory harmonization, will find it harder to respond to domestic economic downturns with expropriations or discriminatory non-tariff measures (NTMs). Thus, we expect firms’ calls for deeper PTAs to be particularly vocal as two countries negotiate under conditions of severe uncertainty. As a result of the increased corporate pressure, governments will be prompted more to conclude deeper agreements when faced with uncertainty spikes than they would in less uncertain times.

We test our argument by analyzing the effect of sharp rises in uncertainty during the negotiations of 251 PTAs on the design of these agreements. Relying on a series of multivariate regressions, we find that PTAs signed by countries that faced with uncertainty spikes are on average deeper. In contrast, we do not find any robust results for the expectation that governments would enhance PTA flexibility under conditions of severe uncertainty. These findings suggest that governments tend to tighten their international commitments rather than loosening them when faced with uncertainty. Our results are novel considering how the existing literature has focused on the positive effect of uncertainty on institutional flexibility.

This paper contributes to furthering our understanding of the drivers behind the design of PTAs and includes important implications for advancing the institutionalist debate. First, existing research on the design of international institutions has mainly explored the structural drivers of PTA design choices, such as democratic institutions, electoral systems, or industry preferences (Allee and Elsig, Reference Allee and Elsig2017; Baccini, Dür, and Elsig, Reference Baccini, Dür and Elsig2018; Baccini, Reference Baccini2019, 19; Lechner, Reference Lechner2016). Yet, the literature has largely overlooked the effects that time-varying factors, such as uncertainty, have on treaty-design preferences. While electoral institutions and industry preferences are relatively stable, uncertainty can rise abruptly and unexpectedly. In doing so, it could affect the trust and risk perception of economic actors, which would demand stronger commitments to mitigate the uncertainty-induced risks. Second, scholarly attention to PTA design preferences has mainly modelled uncertainty as negotiators’ imperfect information about future gain distributions from an agreement (Rosendorff and Milner, Reference Rosendorff and Milner2001; Koremenos, Reference Koremenos2005). In contrast, we focus on exploring the effects of unpredictability as countries negotiate international agreements. Third, a focus on uncertainty and the PTA design nexus fills an important gap in the literature. While a few existing studies have looked at how uncertainty impacts countries’ willingness to enter new trade agreements (Fernandez and Rodrik, Reference Fernandez and Rodrik1991; Hollyer and Rosendorff, Reference Hollyer and Rosendorff2012; Mansfield and Milner, Reference Mansfield and Milner2018), the effects of uncertainty on how PTAs are designed are still unexplored.

2. Preferences on Institutional Design

Today, the economic gains from PTAs originate less from tariff concessions than from the harmonization of domestic regulations, the removal of NTMs, and the protection of foreign investment (Rodrik, Reference Rodrik2018). As a result, the depth of PTAs has emerged as the main indicator of countries’ ambition to liberalize (Maggi and Ossa, Reference Maggi and Ossa2021). PTA depth is defined as the extent to which an agreement constrains countries’ behavior by removing domestic trade obstacles such as ‘burdensome technical standards, discriminatory food safety and animal and plant health measures, inadequate protection of IPRs, and competition rules that discriminate against foreign traders’ (Baccini, Dür, and Elsig, Reference Baccini, Dür and Elsig2015, 766). To be clear, we do not consider, as part of our definition of PTA depth, non-trade provisions related to issues such as labour or the environment. Deep PTAs can also contain sophisticated ex-post mechanisms to monitor compliance, such as ad hoc joint implementation bodies (Dür, Baccini, and Elsig, Reference Dür, Baccini and Elsig2014; Dür and Gastinger, Reference Dür and Gastinger2023). Thus, PTA depth entails long-term commitments to regulatory harmonization that can be costly for countries to bear. First, certain domestic standards may be in place to meet the protectionist demands of certain industries, which makes it difficult for governments to rollback on them (Gulotty, 2020). Second, reforming national regulations can also be contentious as domestic consumers oppose harmonization with foreign standards, especially in sensitive fields such as product and food safety (Laursen and Roederer-Rynning, Reference Laursen and Roederer-Rynning2017). For instance, the negotiations of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) agreement faced severe opposition by consumers concerned about environmental, food, and health regulations (Young, Reference Young2016).

Studies have shown that deep PTAs also tend to include flexibility provisions (Baccini, Dür, and Elsig, Reference Baccini, Dür and Elsig2015). We define flexibility as clauses allowing parties to temporarily suspend specific treaty commitments on certain conditions. The broader literature on the rational design of international institutions has widely explored the institutional coexistence of depth and flexibility (Koremenos, Lipson, and Snidal, Reference Koremenos, Lipson and Snidal2001; Kucik and Reinhardt, Reference Kucik and Reinhardt2008; Rosendorff, Reference Rosendorff2005). The presence of two opposing design features, such as depth and flexibility, is shaped by political trade-offs. While deeper commitments provide a clearer rulebook for cooperation in the long-term, contracts that include deep hand-tying commitments is costly both from an administrative viewpoint and politically. One can expect the demand for more flexible institutions to increase for two sets of reasons. First, agreements that are more flexible are administratively easier to negotiate, as their agenda is less extensive. Second, a more flexible agreement can ease domestic political costs by allowing obligations to be suspended, which can meet the needs of constituents who face losses from unconditional liberalization. As a result, flexibility provisions feature prominently in international agreements to ease the negotiation and implementation of deep commitments (Rosendorff and Milner, Reference Rosendorff and Milner2001; Downs and Rocke, Reference Downs and Rocke1995). During negotiations, contemplating flexibility provisions can ease bargaining costs as parties grant themselves the right to temporarily suspend some obligations in the future (Kucik and Reinhardt, Reference Kucik and Reinhardt2008). At the implementation stage, flexibility provisions make stringent commitments compatible with selective and temporary suspensions, a trade off that fosters the long-term stability of institutions. Rosendorff (Reference Rosendorff2005), for example, formalizes the intuition that delegation to the WTO Dispute Settlement Procedure (DSP) helps to strike a balance between agreement rigidity and flexibility that preserves the overall stability of the trade regime. In PTAs, flexibility provisions include general safeguard mechanisms, balance of payments exceptions, and the possibility to temporarily impose anti-dumping and countervailing duties to counter foreign predatory pricing (Baccini, Dür, and Elsig, Reference Baccini, Dür and Elsig2015). In sum, flexibility clauses emerge as an inherent feature of deep PTAs.

While governments value flexibility when committing to international institutions, market actors generally value deep agreements, which can serve as institutional safety nets facilitating global trade and investment. In a world of globally fragmented production and consumption, the operations of firms can be heavily disrupted if uncertainty arises in a preferential trade relation. In this context, PTAs can benefit firms by significantly reducing the volatility in international trade and investment relations (Mansfield and Reinhardt, Reference Mansfield and Reinhardt2008). In particular, PTAs containing provisions on regulatory convergence, investment protection, and IPRs are beneficial to firms as they reduce the risks associated with operating in different jurisdictions and regulatory environments.

Firms’ and industry preferences are particularly important when analyzing the design of PTAs since corporate actors play a powerful role in shaping trade policy outcomes. Highly productive firms and multinational corporations (MNCs) have emerged as both the largest beneficiaries from preferential trade liberalization and as the key players in lobbying on PTAs (Madeira, Reference Madeira2016; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Milner, Bernauer, Osgood, Spilker and Tingley2019). In the US, large MNCs have been shown to dominate public coalitions in support of PTAs and account for the largest share of lobbying expenditure related to PTAs (Osgood, Reference Osgood2021). The extensive lobbying efforts of large MNCs in this context can be primarily explained by the fact that the economic gains from PTAs are concentrated in the hands of few globalized firms, thereby facilitating individual and collective action on their part. Indeed, PTAs are suspected to ‘empower … politically well-connected firms, such as international banks, pharmaceutical companies, and multinational corporations’ at the expense of less organized interests (Rodrik, Reference Rodrik2018, 75).

As a result, deep PTAs reflect particularly the interests of globalized firms. A survey among MNCs has shown that these corporations prioritize foreign investment protection over traditional PTA features such as tariff reductions (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Milner, Bernauer, Osgood, Spilker and Tingley2019). Treaty provisions on investment protection can reduce firms’ perceived risk of nationalization or discriminatory taxation (Elkins, Guzman, and Simmons, Reference Elkins, Guzman and Simmons2006). Deep PTAs can mitigate business concerns that economic or political developments may suddenly make governments more likely to expropriate foreign investment. Moreover, deep PTAs are supported by the broader business community beyond MNCs. Surveys have shown, for example, that representatives of business interests from virtually all sectors strongly support deep agreements with IPR provisions (Dür et al., Reference Dür, Huber, Mateo and Spilker2023). Similarly, regulatory convergence under a PTA can mitigate the risk that a trading counterpart will leverage domestic product regulation in order to place unnecessary market barriers (Hoekman and Mavroidis, Reference Hoekman and Mavroidis2015). In sum, deep PTAs can be important in mitigating uncertainty functions for firms as they limit the political risk involved in operating in foreign jurisdiction by imposing substantial policy constraints on treaty members.

3. Deep PTAs: Credibility and Uncertainty Mitigation in Hard Times

Having established the institutional design preferences of firms, we now turn to the question of how sharp rises in uncertainty might amplify the calls by corporate actors for deeper PTAs. We generally assume the design of PTAs to be the aggregate result of the interplay between government and corporate interests in each of the contracting parties. In this context, we argue that uncertainty spikes might critically affect the outcome of this interplay. Specifically, uncertainty can increase the risks associated with operating in a particular country and act as a trade and investment disincentive.

We understand uncertainty to be political, economic, or a combination of both. For example, political uncertainty can affect capital flows, which in turn might impact employment and domestic demand, hence acquiring genuinely economic contours. Moreover, dramatic increases in uncertainty can be the result of both endogenous and exogenous events. For example, uncertainty surrounding the outfall of the 2008 financial crisis was rooted in endogenous phenomena such as excessive lending that originated within the US economy. In contrast, exogenous sources of uncertainty can also prompt negotiators to scale up their institutional commitments. For example, during the negotiations of the EU–Ukraine Association Agreement in 2014, Russia’s annexation of Crimea led negotiators to deepen the treaty commitments they were contracting on by boosting Ukraine’s access to the Single Market (Dimitrova and Dragneva, Reference Dimitrova and Dragneva2023). The risk perception of firms is typically affected by both political and economic uncertainty. For example, Julio and Yook (2012) show that firms significantly reduce their investment in the face of both perceived political instability and uncertainty about economic outcomes. A recent prominent example of a dramatic increase in uncertainty is the COVID-19 pandemic, which found world economies unprepared to tackle their short-term sanitary externalities, and the medium-term implications have had systemic impacts on economies, employment, and society. We suggest that uncertainty spikes consist of a complex conundrum of political, social, economic, or natural developments, all characterized by one key implication for globally operating firms: increased unknowns about governments’ credible commitments to refrain from adopting trade-restrictive measures (such as tariffs, discriminatory subsidies or NTMs), and/or from expropriating or harming foreign investors’ assets. Thus, uncertainty spikes can significantly increase the political risk faced by corporate actors operating in the respective markets.Footnote 2

The literature has shown that uncertainty spikes, be they endogenous or exogenous, are connected to trade policy in important ways. Some scholars have argued that these shocks are associated with increased protectionism (Simmons, Reference Simmons1997; Rogowski, Reference Rogowski1989). Other studies have reached opposite conclusions, positing that shocks (especially economic ones) give governments an urgency that allows them to adopt unpopular policies, such as liberalizing sectors and even concluding new PTAs (Olson, Reference Olson1982; Mansfield and Milner, Reference Mansfield and Milner2018). For example, in the aftermath of Brexit, the UK rushed to conclude new PTAs with a number of global counterparts to make up for the exit from the EU single market. The UK was keen on making costly concessions in the interest of market stability, including granting better access conditions to Japanese car companies than those that existed under the EU–Japan Economic Partnership Agreement, and by expanding the tariff quota for imports of Chilean sheep meat (Garcia, Reference Garcia2023).

We emphasize how uncertainty can severely affect firms engaged in international trade (Taglioni and Zavacka, Reference Taglioni and Zavacka2013) and directly affect their business decisions.Footnote 3 MNCs are particularly affected by uncertainty spikes given their reliance on just-in-time production, decentralized sourcing, and global operations. Economists have long established that uncertainty can substantially decrease international investment flows (Bloom, Reference Bloom2009; Bernanke, Reference Bernanke1983; Caldara et al., Reference Caldara, Fuentes-Albero, Gilchrist and Zakrajšek2016). This is particularly relevant since modern PTAs are as much about trade as they are about investment, regulatory harmonization, and IPRs (Baccini, Reference Baccini2019). In addition, uncertainty rises can have severe consequences for the functioning of global value chains (GVCs) through which the majority of today’s trade is conducted (WTO, 2021). Uncertainty arising from economic, social, or natural events in one country can quickly affect the functioning of entire global production networks as governments might implement actions that restrict the free flow of goods, services, or people. Moreover, uncertainty related to environmental or health crises might prompt governments to impose new NTMs such as sanitary and phytosanitary measures (SPS) or technical barriers to trade (TBTs) which can be trade restrictive (Crivelli and Groeschl, 2016). As a result, production and investment decisions of globally operating firms hinge heavily on the uncertainty related to a country. In conditions perturbed by high uncertainty, business lobbies have therefore strong incentives to push governments even more to negotiate deep PTAs. The underpinning mechanism considers three main types of incentives.

First, deep PTAs signal a stronger commitment to international economic institutions and the rule of law. Importantly, deep PTAs contain provisions on investment protection, enforcement of IPRs, and the rule of law, all of which are particularly important to globally operating firms (Zeng, Sebold, and Lu, 2020). Uncertainty linked to regulatory risks and political instability have long been identified as a major hurdle for investment by these firms (Tuman and Emmert, Reference Tuman and Emmert2004; Vadlamannati, Reference Vadlamannati2012). Deep PTAs can ‘step in’ when heightened uncertainty amplifies domestic economic, judicial, and institutional shortcomings that prevent countries from gaining the trust of corporate actors (Büthe and Milner, Reference Büthe and Milner2008, Reference Büthe and Milner2014). Indeed, deep PTAs have been shown to increase the trustworthiness of countries in the eyes of globalized firms (Baccini and Urpelainen, Reference Baccini and Urpelainen2014).

Second, deep PTAs can improve regulatory cooperation and prevent new NTMs, especially when uncertainty spikes incentivize regulatory action by governments. In contrast to shallow agreements, PTAs that are more comprehensive mandate cooperative regulatory choices, for instance through SPS or TBT committees that facilitate the reduction or elimination of regulatory barriers (Grossman, McCalman, and Staiger, 2021). This cooperative function of PTAs is particularly important for MNCs whose business operations might be severely affected by trade frictions arising from new regulatory barriers prompted by increased uncertainty. Indeed, deep PTAs have been shown to reduce trade costs caused by NTMs and to increase trade flows (Santeramo and Lamonaca, 2022). Therefore, deep PTAs can act as an important safeguard against the introduction of new NTMs that could impose significant costs on globally active firms.

Third, deep PTAs can counter some of the ramifications of dramatic increases in uncertainty such as fragmented supply chains. Uncertainty spikes can severely impact the smooth functioning of GVCs and, thus, lead to substantial economic losses for firms (Baldwin and Freeman, 2022). In this context, deep PTAs can play an important role in enhancing the resilience of GVCs when uncertainty is high (Hauser, Gutierrez, and Winkler, Reference Hauser, Gutierrez, Winkler, Elsig, Claussen and Lazo2024). Deep PTAs can provide information and help firms diversify their supply chains, thus decreasing the risks associated with operating within global production networks (Grossman, Helpman, and Lhuillier, 2021).

As deep PTAs can be an important tool in mitigating the effects of uncertainty spikes, by providing information and legal certainty, we expect globally operating firms to increase their lobbying efforts to strengthen commitments entailed in PTAs when confronted with heightened uncertainty. Indeed, recent evidence suggests that firms increase their lobbying activity when confronted with uncertainty. Specifically in the context of high uncertainty, lobbying becomes an even more important tool for firms to manage political risk, to access information, to gain an understanding of current policy-making processes, and to influence policy to extract economic rents (Hassan et al., Reference Hassan, Hollander, van Lent and Tahoun2019). In the US context, scholars have shown that during the COVID-19 crisis, policymakers granted privileged access to business interests (Eady and Rasmussen, Reference Eady and Rasmussen2024) with MNCs and other large firms increasing their lobbying spending (Wilson, Reference Wilson2021). Moreover, Ban, Palmer, and Schneer (Reference Ban, Palmer and Schneer2019) observe that in times of increased uncertainty, lobbyists file more reports and earn higher salaries.

Importantly, one might expect that uncertainty spikes could also trigger increased lobbying by protectionist corporate firms that oppose deep PTAs. However, firms that self-select into lobbying on PTAs are generally supportive of more liberalization. The occurrence of sharp rises in uncertainty will cause these pro-liberalization firms to double-down on their lobbying efforts. Successful lobbying is often associated with substantial up-front costs. Entry barriers to lobbying, such as hiring the right lobbyist, developing a lobbying agenda, searching for the right political access-points as well as lacking experience in influencing policy making, limit the political action of non-lobbying firms. As a result, it has been found that non-lobbying firms, i.e. firms which have not lobbied before, are less likely to start lobbying when faced with high uncertainty (Shang, Lin, and Saffar, Reference Shang, Lin and Saffar2021), while already politically active firms will scale up their lobbying efforts (Grossman and Helpman, Reference Grossman and Helpman2001; Bombardini, Reference Bombardini2008; Shang, Lin, and Saffar, Reference Shang, Lin and Saffar2021). With regard to trade policy, the political economy of trade agreements is mainly shaped by exporting and import-dependent companies, rather than protectionist interests (Rodrik, Reference Rodrik2018; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Milner, Bernauer, Osgood, Spilker and Tingley2019). For instance, in the case of US PTAs, firms lobbying for these agreements supported them in 99.25% of cases over the last two decades (Blanga-Gubbay, Conconi, and Parenti, 2024). In summary, we can expect that when faced with uncertainty spikes, pro-trade firms that are already lobbying are more likely to step up their efforts than protectionist firms, which in most cases do not lobby on PTAs and are unlikely to start lobbying when faced with uncertainty.

We contend that globally operating firms represent a key channel between uncertainty spikes and PTA depth during negotiations. Therefore, in a lobbying environment dominated by pro-liberalization firms, we expect sharp rises in uncertainty to generate higher demand for deep institutions countering the increase in uncertainty in a given trade relationship. To be more precise, we expect lobbying firms to demand stronger commitments and more transparency in the agreement to mitigate the rise in uncertainty. The stronger calls for deeper integration of firms, in turn, make them more likely to shape government preferences and PTA design. As a result, governments enter ambitious commitments that can structure a trade relationship beyond the status quo ante that was exposed to uncertainty in the first place. Therefore, we expect PTAs negotiated by countries experiencing an uncertainty spike to be deeper, all else equal.

4. Empirical Analysis

We deploy a series of multivariate regressions to test our hypothesis on the link between uncertainty rises and PTA design. Our analysis focuses on the period between 1990 and, 2020. The main reason behind this choice is that the end of the Cold War marked a pivotal shift in the global political and economic order, which makes comparisons of uncertainty levels before and after this shift problematic. Given that our hypothesis focuses on the impact of sharp rises in uncertainty on PTA design, we choose the PTA as the unit of analysis. The use of the PTA instead of dyad-year or country-PTA as the unit of analysis has become the predominant approach in the literature on the design of trade agreements (Lechner, Reference Lechner2016; Allee and Elsig, Reference Allee and Elsig2017). First, the design of a particular PTA does not usually differ between members and is consistent over time. Second, the inclusion of separate observations for all members would lead to artificially reduced standard errors and violate the assumption of non-independence. Moreover, following previous studies, we focus on bilateral PTAs since valid inference can be more accurately drawn from comparing two-actor agreements than from multilateral PTAs that often entail dozens of members and, thus, require difficult measurement choices. To identify the design features of PTAs signed in our observation period, we rely on the Design of Trade Agreements Database (DESTA) (Dür, Baccini, and Elsig, Reference Dür, Baccini and Elsig2014). According to DESTA, which is widely regarded as the most comprehensive source of trade agreements, there were 444 bilateral PTAs concluded between 1990 and 2020.

4.1 Measuring Uncertainty Spikes

Measuring uncertainty is an inherently difficult endeavour due to its amorphous nature. Researchers have deployed different strategies and relied on various proxies to estimate uncertainty across space and time. One common approach to measure uncertainty, especially among economists interested in its effects on macroeconomic outcomes, is the volatility in stock markets and other key financial variables (Altig et al., Reference Altig, Baker, Barrero, Bloom, Bunn, Chen and Davis2020; Bloom, Reference Bloom2009). Other approaches include references to policy-related uncertainty in newspapers (Alexopoulos and Cohen, Reference Alexopoulos and Cohen2015; Baker, Bloom, and Davis, Reference Baker, Bloom and Davis2016), perceived uncertainty reflected in surveys of forecasters and economic agents (Ozturk and Sheng, Reference Ozturk and Sheng2017; Rossi and Sekhposyan, Reference Rossi and Sekhposyan2015), or the perceptions of uncertainty contained in Twitter posts (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Bloom, Davis and Renault2021). However, these uncertainty measures often do not allow for country-level differentiation or are limited to a small set of units and, thus, are not particularly well suited for measuring uncertainty in our case.

The best available measure of uncertainty for our purpose is the World Uncertainty Index (WUI) by Ahir, Bloom, and Furceri (Reference Ahir, Bloom and Furceri2022). The WUI captures uncertainty across the globe by tracking critical political and economic trends in over 140 countries. Specifically, the WUI is created by text mining the country reports of the Economist’s Intelligence Unit (EIU). The word ‘uncertain’ (or its variant) is counted for every country report and then normalized according to the total number of words in each report. While the WUI, as a second-order measure, has limitations, the systematic and standardized process in which the EIU country reports are produced helps to allay concerns about the accuracy, ideological bias, and coherence of the WUI. Moreover, the WUI is widely used in academia by the International Monetary Fund, the WTO, and other international organizations. Lastly, the WUI has been shown to be associated with financial flows, gross domestic product (GDP) growth, and political elections (Choi, Ciminelli, and Furceri, Reference Choi, Ciminelli and Furceri2023; Kranz, Reference Kranz2019; WTO, 2021).

In analyzing PTA design, the WUI has three main advantages. Primarily, the index is suitable for the purpose of our analysis since it reflects and shapes the uncertainty perception of globally operating firms. Most of these firms inform their production and investment decisions by consulting expert-based risk-assessment and country reports supplied by private data providers or rating agencies. The EIU country reports underlying the WUI are particularly geared towards commercial and financial actors and utilized in the analyses and risk assessments provided by corporations such as Bloomberg, Haver, and Reuters (Ahir, Bloom, and Furceri, Reference Ahir, Bloom and Furceri2022). Thus, the uncertainty captured by the WUI is likely to feed directly into the decision making of commercial and financial actors worldwide. As theorized above, one crucial driver behind ambitious PTAs is the need to address the concerns and uncertainty perceptions of commercial and financial actors about the state of the world and the behavior of other private and state actors. Therefore, the WUI presents a reasonably good proxy for the kind of uncertainty we expect firms to act on. Second, the WUI is particularly well-suited to capture country-specific uncertainty as the underlying EIU country reports, used in the construction of the index, look exclusively at national developments and, thus, measure the uncertainty specific to individual countries.Footnote 4 Third, with coverage of 143 countries over a 30-year period, the WUI covers all geographic regions in the world and about 99% of global GDP, facilitating our large-N statistical analysis.

Based on the WUI, we create our main explanatory variable, Uncertainty spike, which captures whether at least one of the PTA member countries has experienced a sharp rise in uncertainty. Since we expect only substantial increases to elicit a reaction by firms and have a measurable impact on PTA design, we define an Uncertainty spike as a two-standard-deviation increase in the level of uncertainty between t–1 and t in a given country. We focus on sharp uncertainty rises, as it has been shown that uncertainty becomes particularly relevant for economic agents when it is exceptionally high (Taglioni and Zavacka, Reference Taglioni and Zavacka2013). Importantly, we focus on operationalizing uncertainty rises as increases in the mean level of uncertainty rather than increases in its variance. Unlike other measures commonly used in the literature that derive uncertainty levels from stock market volatility or the variance of macroeconomic variables (Altig et al., Reference Altig, Baker, Barrero, Bloom, Bunn, Chen and Davis2020; Bloom, Reference Bloom2009), the WUI directly measures uncertainty as captured by experts writing the EIU country reports. Moreover, we focus on uncertainty rises measured as the relative inter-annual difference of uncertainty instead of the absolute level of uncertainty in a given year. It is theoretically more insightful to examine whether a sudden surge in uncertainty levels affects PTA design than it is to look at a country’s overall uncertainty level, which might be correlated with structural factors such as its development level or institutional capabilities. Yet, we test alternative specifications of the variable Uncertainty spike in the robustness section, including a measure looking at increases in the absolute level of uncertainty.

4.2 Control Variables

We include a list of control variables in our models that previous studies have linked to the design of PTAs. First, and most importantly, we control for the stickiness of PTA design by accounting for the maximum depth level of past agreements concluded by the individual member countries. Previous research has shown that PTAs often follow an existing template with many provisions being copied and pasted from previous agreements (Allee and Elsig, Reference Allee and Elsig2019, 19; Peacock, Milewicz, and Snidal, Reference Peacock, Milewicz and Snidal2019). To make sure that our results are not driven by this ‘boilerplate’ effect, we include the average of the maximum depth levels of all PTAs signed in the past by each agreement party. Adding this control allows us to capture the actual effect of uncertainty spikes on PTA design and not of any other diffusion dynamics. An alternative approach to control for any time trends with regard to the design of PTAs is to include time dummies. Thus, we also estimate all models using five-year dummies instead of the maximum past-level approach.

Second, we include the control variable Veto players for which we use Henisz’s Polcon measure, which ranges from 0 to 1 and indicates the number of effective government entities holding veto power, the alignment of these entities with the executive, and to what extent their preferences diverge (Henisz, Reference Henisz2002). Many studies have shown the importance of veto players for the formation and design of PTAs (Mansfield and Milner, Reference Mansfield and Milner2012; Allee and Elsig, Reference Allee and Elsig2017). Given the dyadic nature of our data, we calculate the average level across the PTA dyad for Veto players and all other covariates. Third, we add the variable Regime, which comprises a score for regime type derived from the Polity IV measure (Marshall, Gurr, and Jaggers, Reference Marshall, Gurr and Jaggers2017). Controlling for the regime type is important since the literature suggests that more democratic countries are more open to trade, pursue deeper integration, and use trade agreements as a signalling tool to their voters (Mansfield, Milner, and Rosendorff, Reference Mansfield, Milner and Rosendorff2000; Mansfield and Milner, Reference Mansfield and Milner2018, 18). Fourth, we include the variable WTO, which captures whether both contracting parties are members of the GATT or WTO. Moreover, we control for whether two countries are in a strategic alliance in any given year with the variable Ally. We use the data points provided by the Alliance Treaty Obligations and Provisions (ATOP) project (Leeds et al., Reference Leeds, Ritter, Mitchell and Long2002).

We also insert the logged value of bilateral trade in constant, 2015 USD between the PTA partners. We take the data from the COMTRADE database (United Nations, 2023). Following previous studies, we expect that stronger trade links may increase the demand for more comprehensive and ambitious agreements. To control for any economic-power asymmetries between the contracting parties, we include the variable GDP gap, which captures the gap of logged GDP between the signatories. In addition, we include the controls GDP measured in constant, 2015 USD as a proxy for market size and GDPpc measured in constant, 2015 USD as a proxy for development level. The data are derived from the World Bank. The control foreign direct investment (FDI) stock is a measure of the total level of direct investment in US dollars at current prices provided by UNCTAD and indicates the attractiveness of a country as an investment destination. Finally, we also control for the overall level of uncertainty in the world by including the variable World uncertainty using the weighted annual average of global uncertainty across all 143 countries derived from the WUI.

4.3 Model Specification

To test our hypothesis about the link between uncertainty rises and PTA design, we use a range of multivariate regressions and include a Heckman selection model to account for any selection bias in our sensitivity checks. Since the terms of a PTA are unlikely to be altered retrospectively, variation in PTA design is cross-sectional rather than temporal. Hence, we use a cross-sectional set-up regarding PTA design as a function of the existence or absence of uncertainty spikes in member countries prior to signing an agreement. The baseline specification for our analysis is formalized by the following equation:

where the dependent variable Depth indicates the level of ambition of a given PTA k, respectively (Baccini, Dür, and Elsig, Reference Baccini, Dür and Elsig2015, 15). As a proxy for the depth of an agreement, we use the ‘depth index’ from the DESTA dataset, which is a function of tariff cuts and provisions concerning investments, standards, IPRs, services, government procurement, and competition (Dür, Baccini, and Elsig, Reference Dür, Baccini and Elsig2014). These types of provisions are indicative of deep PTAs whereby agreement partners not only coordinate on at-the-border policies such as tariffs, they also seek to ensure that their domestic regulatory environments are compatible, thereby easing trade and investment flows. For example, on product standards, deep PTAs seek to ensure that members harmonize their regulations to minimize NTMs resulting from differing safety, testing, and labelling requirements. These types of costs are irrespective of applying tariff levels, and particularly affect smaller exporters facing relatively higher compliance costs. To increase the robustness of our results, we also use an alternative proxy for agreement depth: the DESTA depth rasch index. This index is built through latent trait analysis of 49 PTA design variables that are theoretically related to depth (range –1.5–2.10) (Baccini, Dür, and Elsig, Reference Baccini, Dür and Elsig2015).

Our main explanatory variable is Uncertainty spike, which indicates whether at least one of the two PTA members has experienced an uncertainty spike. Again, we test different specifications of this variable in the section on sensitivity checks. The vector X contains the set of control variables described above. Robust standard errors are calculated and clustered at the country-dyad level.

5. Discussion of the Results

Table 1 displays the results for our baseline models testing our hypothesis. In particular, Model 1 and Model 2 test the effect of uncertainty spikes on the DESTA additive Depth Index, while Model 3 and Model 4 test it for DESTA’s depth rasch index. Institutional design can be sticky over time (see Lechner, Reference Lechner2016). For this reason, Model 1 and Model 3 control for the average maximum value of depth (as measured by the above two indices) for PTAs previously negotiated by the PTA members. This helps account for simple path dependency whereby negotiators might use previously defined PTA templates, which can act as a confounding variable when measuring the impact of uncertainty on the depth or scope of agreements.Footnote 5 Moreover, Model 2 and Model 4 control for unobserved time trends by incorporating five-year time dummies. Controlling for time is particularly important since there has been a general trend towards deeper agreements over the years. All four models incorporate a range of economic and institutional controls, while also controlling for mean world uncertainty at the time of signing (t).

Table 1. Effect of uncertainty spike on PTA depth – baseline models

Notes. All specifications are estimated using OLS. Standard errors clustered by country-dyad are in parentheses.

* p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, and *** p < 0.01.

The models yield robust support for our expectation that sharp rises in uncertainty lead countries to negotiate deeper PTAs. All coefficients are positive and statistically significant. Specifically, Model 1 shows that country dyads, having experienced an uncertainty spike, negotiate on average, around 12% (OLS coefficient: 0.817) deeper PTAs relative to untreated dyads. Model 2 shows an analogous effect of around 16% (OLS coefficient: 1.089) on agreement depth. When replacing the outcome variable in Models 3 and 4, the effects of an uncertainty spike on PTA depth are consistently positive and statistically significant, being around 11% and 14% respectively.

The results for the control variables are also theoretically insightful. The positive coefficient of World uncertainty is only significant in Model 1, which suggests that PTA depth is a design response to the levels of uncertainty specifically experienced by a negotiating dyad rather than a general institutional response to global uncertainty. As consistently suggested by the coefficient for Veto players, the level of domestic veto-playing as two countries negotiate a PTA does not seem to have a significant effect on depth levels. This complements existing findings in the literature on the negative effect of domestic veto players on the levels of PTA depth (Allee and Elsig, Reference Allee and Elsig2017), which we do not observe in the event of a sharp uncertainty rise. Moving to economic controls, levels of wealth (GDP per capita) in a negotiating dyad are a positive predictor of depth, while GDP gap as a measure of economic asymmetry is only positive and significant in Models 3 and 4. The effect of FDI stock is also positive but only significant in Model 2. This suggests that the effect of being a richer economy on PTA depth is less straightforward than it has been shown for flexibility provisions, which are stronger for PTAs negotiated by high-income countries (Baccini, Dür, and Elsig, Reference Baccini, Dür and Elsig2015). Moving to controls for international factors, trade flows (Trade), shared WTO membership (WTO), and military alliances (Ally) between dyad members do not have significant and consistent effects on PTA depth.

In sum, our results support our argument that the experience of an uncertainty spike leads countries to introduce deeper institutional commitments into PTAs. These findings complement existing literature on institutional responses to uncertainty, which has been largely centered on flexibility as the most natural tool for parties to use as a buffer against the prospect of uncertainty about the state of the world. In so doing, they help re-contextualize the uncertainty-depth nexus into a functional theory of the demand for international institutions (Keohane, Reference Keohane1984). Experiencing comparatively higher levels of uncertainty enhances the demand for more stringent institutions to enhance predictability in countries’ commercial relations. From an institutional perspective, these findings build on research which has shown that domestic shocks, such as economic downturns, enhance governments’ demand for PTAs (Mansfield and Milner, Reference Mansfield and Milner2018). They suggest that as uncertainty exacerbates collective-action problems, the institutional ‘cure’ is found in crafting more stringent institutional commitments, rather than lowering the costs of non-cooperation.

6. Sensitivity Checks

We conduct a range of sensitivity checks to our baseline models to verify the robustness of our findings, including modifications of our uncertainty measure, additional control variables, and the exploration of potential sample selection dynamics. Overall, our results remain robust across different modifications and sensitivity checks.

6.1 North–South Dynamics

First, one concern might be that our findings are driven by a general trend of countries from the Global South signing deep trade agreements with countries from the Global North. To address this concern, we compare two specific categories of North–South agreements – those in which members faced negotiations with uncertainty spikes and those without while still controlling for time trends and past levels of agreement depth. In this way, we seek to exclude the potentially confounding role the agreement type might play and further isolate the effect of uncertainty rises on agreement depth. Running our baseline models again on the restricted sample, we find no difference in our results with the coefficient of Uncertainty spike being still highly significant across all model specifications. This suggests that the increase in levels of agreement depth is not just a function of countries signing deeper agreements with more advanced economies but conditioned on the presence of a dramatic increase in uncertainty.

Moreover, perceptions of uncertainty may differ for South–South PTAs compared to other types of agreements. Recent research suggests that PTAs between countries in the Global South are, on average, becoming deeper (Gamso and Postnikov, Reference Gamso and Postnikov2022). To examine whether uncertainty shocks affect these agreements differently, we include a South–South variable, capturing whether both signatories are from the Global South. We found that South–South agreements are, on average, shallower than those involving at least one Global North country. The relative depth of South–South agreements may still be low due to the presence of numerous shallow treaties concluded in the 1990s. To test whether uncertainty has a differential effect on the depth of South–South PTAs, we also include an interaction term between the Uncertainty spike and the South–South variable. However, the interaction is not statistically significant, indicating that the positive effect of uncertainty spikes on PTA depth does not differ systematically across agreement types.

In addition, we exclude PTAs that have the US and/or EU member countries as contracting parties from our sample. We perform this additional check as US and European PTAs are often regarded as the most comprehensive type of trade agreements. Again, the exclusion of the US and EU from our sample has little influence on our findings. Size effect and statistical significance hardly change, indicating that the relationship between sharp uncertainty rises and the depth of PTAs is a broader phenomenon.

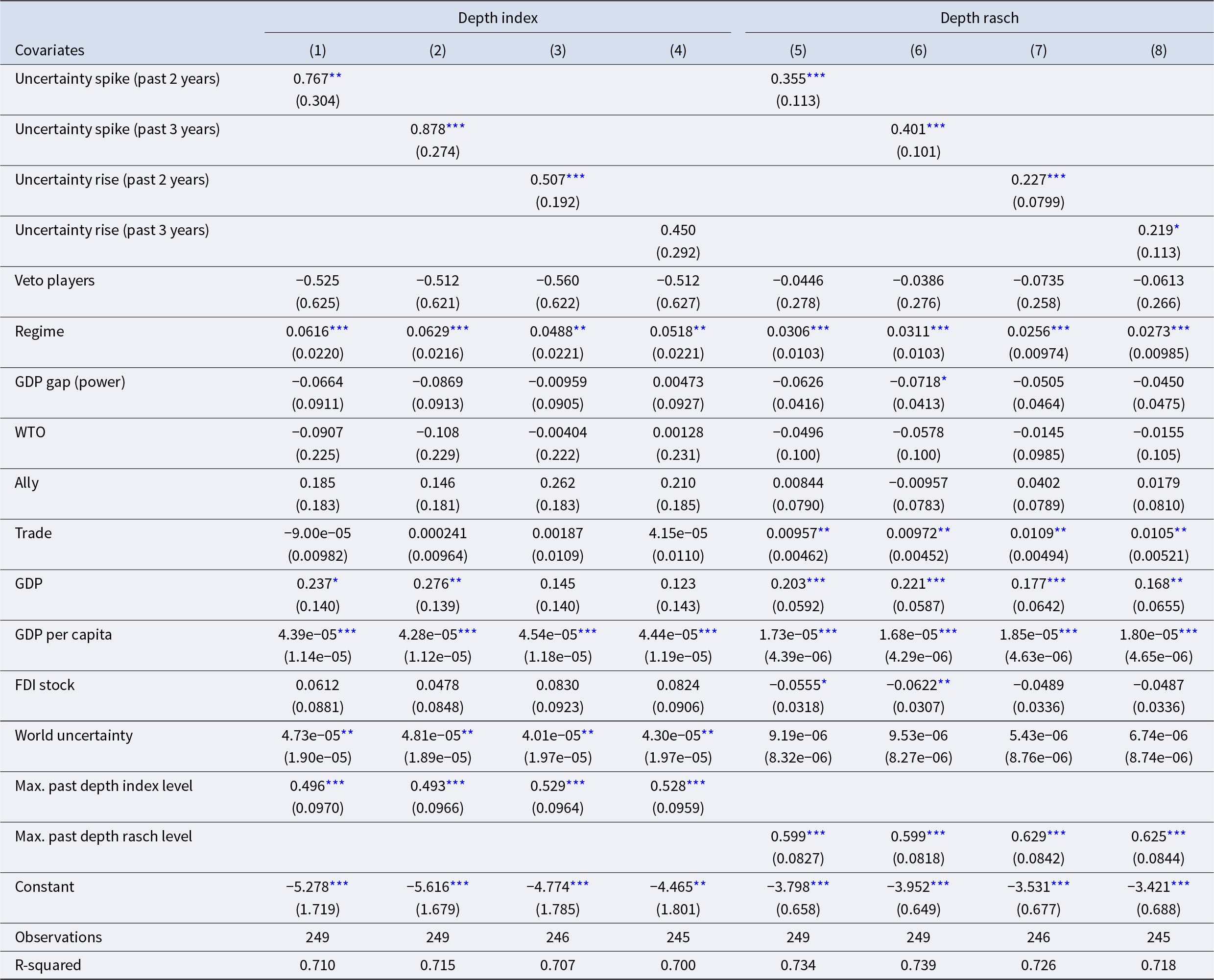

6.2 Different Uncertainty Specifications

We undertake a range of modifications of our main predictor using the Model 1 specification of our baseline models with all control variables. In a first step, we test whether increasing the time window in which an uncertainty spike can occur changes the outcome of our estimations. One might argue that even though the impact of an uncertainty rise might be greatest towards the end of the negotiations, there is the possibility of an effect during the entire duration of negotiations. While some PTA negotiations can last several years or even decades, such as the EU–Mercosur negotiations, most trade agreements are concluded in between two and three years (Moser, Rose, and Zurich, Reference Moser, Rose and Zurich2012). Therefore, we create two new predictors that capture whether one of the PTA partners has experienced an uncertainty spike in the last two or three years, respectively. As shown in Table 2, our results show slightly stronger effects of uncertainty on the level of depth when considering uncertainty spikes having occurred during a larger time-window. In a second step, we test whether having experienced a more gradual increase in uncertainty during PTA negotiations has any effect on the depth of PTAs. For this purpose, we create the dummy variable Uncertainty rise, which indicates whether one or more of the PTA partners had been facing a constant rise in uncertainty over the last two or three consecutive years, respectively. As shown in columns 3 and 4 as well as 7 and 8 in Table 2, the results we obtain after replacing our main predictor with these modifications are consistent with our previous findings, corroborating that uncertainty is positively linked to the depth of PTAs.

Table 2. Effect of uncertainty spike on PTA depth – alternative specifications of uncertainty spike

Notes. All specifications are estimated using OLS. Standard errors clustered by country-dyad are in parentheses.

* p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, and *** p < 0.01.

We also seek to test whether including measures of agreement flexibility affect our results. Thus, we add the DESTA ‘flexescape’ measure to our baseline models estimating PTA depth. Our results are robust to the inclusion of the other design measure. It is worth highlighting that the size of the coefficient of Uncertainty rise is more than twice the size of the coefficient of Flexescape. Overall, the occurrence of uncertainty spikes seem to break the depth-flexibility nexus observed in PTAs negotiated in the absence of uncertainty – which we will further analyze below. Moreover, one might argue that uncertainty spikes might not necessarily translate into protectionist policies on trade and investment. Specifically, domestic institutional and political constraints might mediate the threats of policies aimed at restricting economic freedom in reaction to uncertainty. To address this potential concern, we include the variable Rule of law in our baseline models. We derive a measure for rule of law from the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators database. Our results remain robust to including this additional control.

6.3 Addressing Selection Bias

Third, we explore whether our findings are sensitive to sample selection dynamics. Given that we find robust evidence that uncertainty rises affect PTA design, one might also expect them to affect the formation of PTAs in the first place. To account for any sample selection dynamics, we estimate a Heckman selection model. While the Heckman approach is relatively sensitive to the assumptions of joint normal errors and homoscedasticity, it can help detect possible biases in our results from non-random selection of countries into PTAs. Specifically, we estimate both the selection and the outcome equations simultaneously using a 2-step estimation technique. Both equations include the same set of covariates, except the selection variable, which helps to identify the model. The selection variable is expected to have an influence on the probability of concluding a PTA but not on its design. Following previous studies, we use the distance (log) in kilometres between the two countries as the selection variable (Allee and Elsig, Reference Allee and Elsig2017). We estimate a selection equation of the following form:

\begin{equation}\Pr \left( {PT{A_{ijk,t}} \gt 0} \right) = {\text{ }}\varphi [{\text{ }}{\alpha _1}Uncertainty{\text{ }}spik{e_{ij,t}} + X'\theta{ + \alpha_2}{\text{ }}Distanc{e_{ij}} + { \varepsilon _{ijk,t}}]\end{equation}

\begin{equation}\Pr \left( {PT{A_{ijk,t}} \gt 0} \right) = {\text{ }}\varphi [{\text{ }}{\alpha _1}Uncertainty{\text{ }}spik{e_{ij,t}} + X'\theta{ + \alpha_2}{\text{ }}Distanc{e_{ij}} + { \varepsilon _{ijk,t}}]\end{equation}where Φ(.) is a standard normal distribution function, and an outcome equation of the form:

\begin{equation}\ln \left( {Dept{h_{ijk}}\big|PT{A_{ijk,t}} \gt 0} \right) = \beta {{\text{ }}_1}Uncertainty{\text{ }}spik{e_{ij,t}} + {\text{ }}X'\theta + {\beta _\lambda }\lambda (\alpha ) + { \varepsilon _{ijk,t}}]\end{equation}

\begin{equation}\ln \left( {Dept{h_{ijk}}\big|PT{A_{ijk,t}} \gt 0} \right) = \beta {{\text{ }}_1}Uncertainty{\text{ }}spik{e_{ij,t}} + {\text{ }}X'\theta + {\beta _\lambda }\lambda (\alpha ) + { \varepsilon _{ijk,t}}]\end{equation}where PTAijk,t denotes whether country i and country j have concluded a PTA k at time t, we observe 1 if this occurs and 0 otherwise. As a sample, we create a panel dataset with all possible dyad combinations for our observation period from 1990 to 2020. We derive information about whether dyads have concluded a PTA in a given year from the DESTA database. The dependent variable Depthijk in the outcome equation indicates the level of ambition of a given PTA k between country i and j. As a proxy for the depth of an agreement, we again use the DESTA depth index and depth rasch indices.

As shown in Table 3, the Heckman models return similar results to our baseline models with strong support for our expectation on the positive effects of uncertainty spikes on agreement depth. Interestingly, while dramatic increases in uncertainty seem to also have a significant effect on the signing of PTAs – an uncertainty spike slightly increases the likelihood of PTA formation – there is no evidence of selection bias in our model as indicated by the insignificance of lambda, which represents the coefficient associated with the inverse Mills ratio. The results of the selection equation indicating a positive effect of uncertainty spikes on the probability of PTAs formation mirror previous findings in the literature, such as Mansfield and Milner (Reference Mansfield and Milner2018), who show that governments’ propensity to enter new economic agreements might increase during economic downturn shocks. Overall, the results emphasize the stability of our findings after accounting for sample selection.

Table 3. Effect of uncertainty spike on PTA depth – Heckman selection model

Notes. All specifications are estimated using the 2-stage Heckman selection model. Standard errors clustered by country-dyad are in parentheses.

* p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, and *** p < 0.01.

7. What about the Uncertainty–Flexibility Nexus?

While the empirical findings above suggest that countries exposed to uncertainty spikes seek to maximize institutional depth, extensive literature on the rational design of institutions suggest that governments resort to flexibility provisions when faced with uncertainty (Rosendorff and Milner, Reference Rosendorff and Milner2001; Koremenos, Reference Koremenos2005; Abbott and Snidal, Reference Abbott, Keohane, Moravcsik, Slaughter and Snidal2000). Therefore, we also test whether sharp rises in uncertainty also lead to more institutional flexibility. In PTAs, flexibility often takes the form of escape provisions or safeguards that allow a regime to survive the shocks of unforeseeable contingencies and prevent its overall breakdown. Thus, we test the effects of uncertainty shocks on the extent of flexibility provisions in a PTA.

Governments are typically engaged on two fronts to mitigate the adverse effects of rising uncertainty. Internationally, they need to reassure other countries and market actors that they will not renege on their commitments to international institutions, upholding their reputation as reliable partners. Domestically, they are called upon to use their policy and regulatory powers to offset the negative consequences of the uncertainty experienced by constituents. This often consists of enhancing domestic protection by discriminating against imports (Evenett, Reference Evenett2019; Biffi, Kucheriava, and Singh, Reference Biffi, Kucheriava, Singh, Elsig, Lazo and Claussen2024). One option is to deploy unilateral trade-restrictive measures to cater to traditionally protected groups, workers, and voters. Yet, such measures can also encounter opposition from globally connected actors such as MNCs, as in the case of globalized US firms criticizing Trump’s steel tariffs (Lee and Osgood, Reference Osgood2021). Moreover, the existence of sanction mechanisms, such as the WTO dispute settlement body, and the possibility of retaliatory tariffs increase the costs of unilateral defection. Thus, governments might choose a different option to respond to domestic pressure, which is to increase the flexibility of their international commitments.

Flexibility is an important treaty-design resource allowing trade-restrictive emergency measures to be still compatible with long-term institutional commitments to liberalization (Rosendorff, Reference Rosendorff2005). Common flexibility provisions include antidumping and countervailing duties, which are designed to respond to unforeseen import pressure resulting from predatory pricing and discriminatory subsidies. It also comprises extended timelines to bring tariffs down for specific products or for complying with given international product standards or IPRs. For example, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which was signed in the midst of the second wave of COVID-19, includes an important discretionary option encouraging full flexibility with respect to the compulsory licensing mechanism for medicines under the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) (Kuhlmann, Reference Kuhlmann2021). The occurrence of uncertainty shocks can be a powerful learning event for policymakers, enhancing their support for institutional flexibility. Rational negotiators have been shown to take stock of information they possess up until the time of contracting and to reflect such information as they design or update their treaty commitments (Koremenos, Lipson, and Snidal, Reference Koremenos, Lipson and Snidal2001). Thus, we might also expect an increase in flexibility provisions when countries are faced with dramatic rises in uncertainty during PTA negotiations.

To test the relationship between uncertainty spikes and PTA flexibility, we run our baseline model described above with the extent of flexibility in a PTA as outcome variable. We use the DESTA Flexescape index as a proxy for the degree of flexibility of a given PTA which captures whether the parties include the following opt-outs into a PTA: the possibility to suspend agreed tariff cuts in the event of balance of payments issues, to impose countervailing duties, to impose anti-dumping duties, and a general safeguard provision. To increase the robustness of our results, we also use DESTA’s Flexrigid index as an alternative proxy for PTA flexibility. Flexrigid captures how rigid flexibility provisions are (range 0–8). The index helps better qualify our understanding of the effect of uncertainty rises on flexibility by checking for the number of requirements and ‘strings’ that are attached to parties’ possibility to invoke escape provisions. Table 4 presents the results of our models with Model 1 and Model 2 testing the effect of uncertainty spikes on the DESTA additive Flexescape index, which conceives flexibility as the intensity of long-term escape provisions within a PTA (range 0–4). Model 3 and Model 4 test for the same effect on DESTA’s Flexrigid index, which captures how rigid flexibility provisions are (range 0–8). To account for possible path dependency, Model 1 and Model 3 control for the maximum levels of flexibility in PTAs previously negotiated by the dyad (as respectively measured by the two above indices). All four models incorporate a range of economic and institutional controls, as well as the overall level of World uncertainty at the time of signing (t).

Table 4. Effect of uncertainty spike on PTA flexibility – baseline models

Notes. All specifications are estimated using OLS. Standard errors clustered by country-dyad are in parentheses.

* p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, and *** p < 0.01.

In contrast to arguments emphasizing the uncertainty–flexibility nexus, our findings do not show robust support for the expectation that uncertainty leads countries to negotiate PTAs that are more flexible. The effect of Uncertainty spike is positive and statistically significant in Model 1, but loses its statistical significance after controlling for time trends.Footnote 6

Moreover, while the coefficient for Model 1 suggests that facing an uncertainty spike leads a dyad to negotiate around 9% more flexible PTAs relative to untreated dyads (coefficient: 0.372), the level of flexibility in past agreements has a stronger and more significant effect of around 16% on flexibility of the negotiated agreement. We also include as outcome variable the DESTA Flexrigid index, which captures whether negotiators agree on GATT/WTO safeguards, if they extend safeguard duty duration beyond GATT/WTO timings, and whether they agree on de minimis dumping margins different from GATT/WTO ones (Baccini, Dür, and Elsig, Reference Baccini, Dür and Elsig2015). This index also does not appear to be significantly impacted by dramatic uncertainty rises.

We contend that these inconsistencies between results for depth and flexibility speak to the special conditions unlocked by uncertainty spikes in the context of PTA contracting. While existing studies have found an average positive relationship between levels of depth and flexibility (Baccini, Dür, and Elsig, Reference Baccini, Dür and Elsig2015), they have done so without testing for the effect that sharp rises in a dyad’s uncertainty can have on bargaining outcomes relative to less uncertain dyads. Based on our results for PTA flexibility, we suggest that the event of an uncertainty spike alters the usual balance between depth and flexibility provisions as complementary design features. At both the international level and the domestic level, uncertainty increases incentives for firms and governments to prioritize depth, which enhances the solidity of their institutional commitments, over the possibility of suspending those commitments – i.e., flexibility (Hassan et al., Reference Hassan, Hollander, van Lent and Tahoun2019). Furthermore, governments are also keen to commit to open trade in times of economic hardship to showcase their ability to improve the living conditions of their voters (Mansfield and Milner, Reference Mansfield and Milner2018). Thus, governments’ need to appeal to their constituents aligns with firms’ preferences for depth as the optimal design solution in PTAs.

8. Conclusion

It is often assumed that uncertainty incentivizes countries to negotiate ample flexibility provisions. By contrast, our findings reveal that when faced with uncertainty spikes, countries tend to prioritize PTA depth, not flexibility, as the preferred institutional solution to mitigate uncertainty. Depth enhances parties’ commitments to market liberalization, which can be threatened under uncertainty by unilateral and protectionist policies. It also helps structure and clarifies international investment commitments. This dynamic has been prevalent in the case of multiple PTAs negotiated in recent years. In 2018, the EU and Japan entered the largest bilateral PTA concluded to date amid uncertainty caused by US unilateral trade measures, agreeing on deep liberalization commitments in even sensitive sectors like agriculture and cars (Inagaki and Lewis, Reference Inagaki and Lewis2018). In 2025, the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and Mercosur concluded a deep PTA after eight years of negotiations in the face of global trade being under strain due to US tariffs.

Our vast range of multivariate regressions and sensitivity checks consistently demonstrate the positive nexus between uncertainty spikes and deep PTAs. By contrast, we find inconsistent evidence for the claim that uncertainty would lead countries to make PTAs more flexible. Overall, our findings complement existing theories about the rational design of international institutions under conditions of uncertainty. Rather than using institutional flexibility as a tool to cope with uncertainty, our findings reveal that countries rather demand credible commitments in turbulent times, which is reflected in their institutional design choices.

By doing so, our findings echo the focus in early institutionalist arguments on credible commitments as the fundamental currency of international cooperation (Keohane, Reference Keohane1984) and point to a potentially optimistic development in times of global turmoil. While multilateral trade cooperation has come under increased strain and institutions such as the WTO are in deep crisis, our findings show that countries might pursue deeper bilateral integration in response. Both firms and countries continue to strive for predictability and continuity. Hence, we might observe that many countries around the globe will still pursue deeper PTAs in the future. Recently negotiated agreements by the EU, EFTA, and the UK point to this direction. Our study focuses on the case of trade and investment governance, however, we believe the relationship between uncertainty and institutional depth is a promising nexus to be explored in other timely domains of international cooperation, such as the environment, public health, and security.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474745625101419.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following individuals for their comments which helped improve this paper: Gal Bitton, Lawrence Broz, Christina Davis, Cédric Dupont, Manfred Elsig, Colette Fogarty, David Lake, Noémie Laurens, Jialu Li, Tim Meyer, Sung Min Rho, Camilla Sante. We are also grateful for all the feedback received from participants in the PEIO Conference, San Diego, 2023, the Brown Bag Seminar, World Trade Institute, Bern, and the Work-in-Progress Seminar Series at the Geneva Graduate Institute in the fall of 2022.

Funding

This research was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation, grant numbers: 200594; 205796.