1. Introduction

Rough walls are commonplace in practical combustion devices such as internal combustion engines, gas turbines and furnaces (Bons Reference Bons2010). The presence of wall roughness can modify boundary layer turbulence (Krogstad & Antonia Reference Krogstad and Antonia1994; Chan et al. Reference Chan, MacDonald, Chung, Hutchins and Ooi2015; MacDonald et al. Reference MacDonald, Chan, Chung, Hutchins and Ooi2016). When flames interact with a boundary layer, the combustion characteristics near the wall are likely influenced, which impacts heat transfer, combustion efficiency and pollutant emission in combustors. The upstream flame propagation within the near-wall low-velocity region of the flow is referred to as boundary layer flashback, which is considered a primary concern in the design of advanced combustion systems, particularly those burning fuels with a fast reaction rate, such as hydrogen (Kalantari & McDonell Reference Kalantari and McDonell2017). It is expected that the characteristics of boundary layer flashback over rough walls would be different from those over smooth walls. However, existing understanding of flashback over rough walls is largely lacking.

The effects of wall roughness on non-reacting turbulent boundary layers have been widely studied in the literature (Schlichting Reference Schlichting1936; Nikuradse Reference Nikuradse1950; Kline et al. Reference Kline, Reynolds, Schraub and Runstadler1967; Grass Reference Grass1971; Townsend Reference Townsend1976; Krogstad & Antonia Reference Krogstad and Antonia1994; Jiménez Reference Jiménez2004; Volino, Schultz & Flack Reference Volino, Schultz and Flack2007; Napoli et al. Reference Napoli, Armenio and De Marchis2008; Lee, Sung & Krogstad Reference Lee, Sung and Krogstad2011; Yuan & Piomelli Reference Yuan and Piomelli2014; Chan et al. Reference Chan, MacDonald, Chung, Hutchins and Ooi2015; Chung et al. Reference Chung, Chan, MacDonald, Hutchins and Ooi2015; MacDonald et al. Reference MacDonald, Chan, Chung, Hutchins and Ooi2016; Squire et al. Reference Squire, Morrill-Winter, Hutchins, Schultz, Klewicki and Marusic2016; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Xu, Sung and Huang2020; Chung et al. Reference Chung, Hutchins, Schultz and Flack2021; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Stroh, Chung and Forooghi2022; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Xu, Sung and Huang2023). These studies have mainly focused on the parameterisation of wall roughness, the prediction of rough-wall friction resistance, the modification of near-wall turbulent coherent structures by roughness and the verification of the outer-layer similarity hypothesis. The parameterisation of rough surfaces is fundamental for predicting the effects of rough walls on flow fields. Selecting appropriate roughness parameters allows for the construction of meaningful predictive models. Nikuradse (Reference Nikuradse1950) experimentally investigated turbulent flows in rough circular tubes and introduced the concept of equivalent sand grain roughness height as a characteristic parameter for the fully rough regime. Various types of roughness elements, such as spherical, square and wedge shaped, can possess equivalent sand grain roughness height values. Additional roughness parameters have been proposed, including the roughness solidity (Schlichting Reference Schlichting1936), the effective slope (Napoli et al. Reference Napoli, Armenio and De Marchis2008), the root mean square of the local surface slope angle (Yuan & Piomelli Reference Yuan and Piomelli2014) and the roughness steepness (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Xu, Sung and Huang2020).

Rough-wall friction resistance is a key quantity that can be predicted using roughness parameterisation. In most engineering systems, turbulent flows over rough walls experience a higher friction resistance compared with those over smooth walls. The increase in wall friction resistance caused by the surface roughness is manifested in the streamwise mean velocity profile as a downward shift in the logarithmic region. Consequently, the efficiency of the system is reduced, as additional energy is required to overcome the increased drag. It is worth noting that the wall friction resistance on rough walls consists of viscous and pressure components. Chan et al. (Reference Chan, MacDonald, Chung, Hutchins and Ooi2015) investigated turbulent flow through pipes with three-dimensional sinusoidal roughness using direct numerical simulations (DNS). They found that the maximum viscous drag occurs at the crest of the roughness element due to the large streamwise velocity gradient in the wall-normal direction, while the maximum pressure drag is located on the slope of the forward face of the roughness element. Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Stroh, Chung and Forooghi2022) explored wall drag on irregular rough walls using DNS. They found that the peaks in surface force generally coincide with the peaks in roughness height. The surface force experiences a sudden increase when the flow impinges on the windward side of the roughness element, followed by a sharp decrease on the leeward side.

The near-wall structure of boundary layer turbulence is strongly influenced by the wall roughness. The spacing of near-wall streaks in the turbulent boundary layer over a smooth wall and their extent in the wall-normal direction are typically of the order of 100 wall units (Kline et al. Reference Kline, Reynolds, Schraub and Runstadler1967). Roughness structures at this size or larger will undoubtedly disrupt the streaks. When turbulence events induced by roughness extend far from the wall, the turbulent structure of the entire boundary layer may be affected. However, if the events induced by roughness are confined to the vicinity of the wall, the turbulent structure in the outer layer of the boundary layer will remain unaffected, similar to the outer-layer structure of the boundary layer over a smooth wall. This is known as the outer-layer similarity hypothesis (Townsend Reference Townsend1976; Jiménez Reference Jiménez2004; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Sung and Krogstad2011; Squire et al. Reference Squire, Morrill-Winter, Hutchins, Schultz, Klewicki and Marusic2016; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Xu, Sung and Huang2020).

In recent decades, many studies have been conducted to understand the impact of wall roughness on turbulent structures. Grass (Reference Grass1971) observed ejections from the near-wall region that extended into the outer layer in the turbulent boundary layer over both smooth and rough walls. These ejections are found to dominate momentum transport and provide a structural connection between the inner and outer layers. In the smooth-wall case, the viscous sublayer is the source of the ejected fluid, whereas in the rough-wall case, the ejections originate from the gaps between roughness elements. Krogstad & Antonia (Reference Krogstad and Antonia1994) conducted experiments in a wind tunnel using a woven stainless steel mesh screen as a rough wall. They found that roughness primarily tilts turbulence structures towards the wall-normal direction. Volino et al. (Reference Volino, Schultz and Flack2007) compared the turbulent boundary layer structures on smooth and rough walls through experimental measurements. They found that the turbulent structures on both rough and smooth walls are qualitatively similar in the outer region, with hairpin packets being a prominent feature in both cases. Quantitatively, the two-point spatial correlation coefficient of velocity fluctuations is 10 % to 20 % lower on rough walls. Chan et al. (Reference Chan, MacDonald, Chung, Hutchins and Ooi2015) conducted DNS for turbulent flow through pipes with three-dimensional sinusoidal roughness, investigating the effects of roughness height and wavelength on pipe flow turbulence. A collapse of first- and second-order statistics in the outer layer of the flow was observed for cases in both the transitionally rough and fully rough regimes. MacDonald et al. (Reference MacDonald, Chan, Chung, Hutchins and Ooi2016) compared turbulent flows over rough walls with varying roughness densities. They showed that the velocity reduction caused by roughness is less noticeable in the roughness-dense regime due to a reduction in the Reynolds shear stress. Ma et al. (Reference Ma, Xu, Sung and Huang2023) investigated the roughness effects on the statistical properties and large-scale coherent structures in turbulent channel flow over three-dimensional sinusoidal rough walls using DNS. They found that the roughness Reynolds number, which is the ratio of roughness height to the wall viscous length scale, has a strong influence on turbulence statistics. As the roughness Reynolds number increases, the shift of the mean streamwise velocity profile in the logarithmic region becomes larger, while the peak intensities of turbulent Reynolds stresses decrease. Notably, these investigations were conducted in non-reacting flows. A comprehensive understanding of the turbulent boundary layer over rough walls in non-reacting flows has been achieved. However, it remains unclear how wall roughness influences boundary layer turbulence in reacting flows.

Boundary layer flashback is a key issue in reacting boundary layer flows and is crucial for the design of advanced combustion systems. The predictions of the occurrence of boundary layer flashback and the flashback speed are directly linked to the safety of combustion systems. The study of boundary layer flashback dates back to the experiments by Lewis & Von Elbe (Reference Lewis and von Elbe1943), who proposed the ‘critical velocity gradient’ model to predict boundary layer flashback. This model is based on the competition between the undisturbed boundary layer velocity and the burning velocity near the wall at the flame quenching distance, while neglecting the flame–flow interaction. It predicts the occurrence of upstream flame propagation when the burning velocity exceeds the flow velocity at the quenching distance from the wall, otherwise, the flame is either statistically stationary or advected downstream by the flow. Since then, extensive experimental and numerical studies have been conducted to investigate the boundary layer flashback mechanism (Lewis & Von Elbe Reference Lewis and von Elbe1943; Gruber et al. Reference Gruber, Chen, Valiev and Law2012; Ebi & Clemens Reference Ebi and Clemens2016; Endres & Sattelmayer Reference Endres and Sattelmayer2018; Ahmed et al. Reference Ahmed, Pillai, Chakraborty and Kurose2019; Bailey & Richardson Reference Bailey and Richardson2021; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023). Kalantari & McDonell (Reference Kalantari and McDonell2017) reviewed the application of the ‘critical velocity gradient’ model and its modified versions for predicting boundary layer flashback. Endres & Sattelmayer (Reference Endres and Sattelmayer2018) analysed turbulent boundary layer flashback using large eddy simulations (LES) and found that flashback is initiated when the size of the flow separation region exceeds the flame quenching distance. Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Wang, Chen, Luo and Fan2023) investigated turbulent boundary layer flashback on isothermal and adiabatic walls using DNS and discovered that the flashback speed is higher on the adiabatic wall due to the increased flame displacement speed near the adiabatic wall.

The above-mentioned studies focused on smooth walls. In recent years, the investigation of boundary layer flashback over rough walls has received increased attention. Hatem et al. (Reference Hatem, Alsaegh, Al-Faham, Valera-Medina, Chong and Hassoni2018) conducted experiments to explore methods for preventing boundary layer flashback in swirl burners. They found that increasing the nozzle wall surface roughness altered the boundary layer characteristics, effectively attenuating the occurrence of flashback. In a numerical study, Ding et al. (Reference Ding, Huang, Han and Valiev2021) conducted an in-depth analysis on boundary layer flashback of laminar flames on rough walls. They found that, on an adiabatic wall, wall roughness can promote boundary layer flashback by increasing stagnation layer thickness. However, on an isothermal wall, wall roughness can reduce the tendency of flashback due to enhanced heat loss to the boundary. These studies improved our fundamental understanding of flame flashback over rough walls.

There are significant interactions of the flame and boundary layer turbulence during boundary layer flashback. The experiment of flashback in a swirling bluff-body flame performed by Heeger et al. (Reference Heeger, Gordon, Tummers, Sattelmayer and Dreizler2010) showed that the rise of static pressure in the streamwise direction induces boundary layer separation and enables the flame to propagate upstream. Clemens et al. (Ebi & Clemens Reference Ebi and Clemens2016; Ranjan, Ebi & Clemens Reference Ranjan, Ebi and Clemens2019) conducted experiments of boundary layer flashback of a swirling flame in a mixing tube with a bluff body, and observed the reverse-flow pockets associated with positively curved portions of the flame front (bulges). Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Chen, Valiev and Law2012) performed DNS of boundary layer flashback in fully developed turbulent channel flows. The DNS data clearly revealed the causal relationship between the low-velocity streaks of the turbulent boundary layer and the backflow regions that occur immediately upstream of flame bulges. Xia et al. (Reference Xia, Han, Wei, Zhang, Wang, Huang and Hasse2023) performed LES of boundary layer flashback in a bluff-body swirl burner and identified two distinct modes of flashback, i.e. the upstream propagation of a swirling flame tongue and the upstream propagation of non-swirling flame bulges. In the first mode, the large-scale flame tongue induces the deflection of streamlines upstream of the flame sheet, which dominates the swirling motion of the flame tongue. In the second mode, small-scale flame bulges lead to the formation of backflow regions and facilitate flashback. Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023) conducted DNS of boundary layer flashback over a smooth plate and found that the near-wall mean velocity and skin-friction coefficient are reduced due to the adverse pressure gradient near the leading edge of the flame bulges induced by combustion. The coherent vortical structures of the boundary layer turbulence are lifted by the adverse pressure gradient. Combustion enhances the ejection event while attenuating the sweep event, which facilitates the occurrence of flame flashback. Notably, the studies of boundary layer flashback mentioned above considered only smooth walls, and the effect of wall roughness on turbulent boundary layer flashback is not yet well understood.

The flame/wall interaction is crucial in boundary layer flashback. The characteristics of combustion are affected when bounded with walls, which might cause flame quenching, and influence quantities of practical interest, such as wall heat flux. Numerous experimental and numerical studies have investigated the interaction between flames and smooth walls. Vosen, Greif & Westbrook (Reference Vosen, Greif and Westbrook1985) measured unsteady heat transfer to a wall during premixed flame quenching and found that the maximum heat flux is correlated with the quenching distance, with the maximum wall heat flux accounting for one third of the steady laminar flame heat release rate (Huang, Vosen & Greif Reference Huang, Vosen and Greif1988). Poinsot, Haworth & Bruneaux (Reference Poinsot, Haworth and Bruneaux1993) pioneered the DNS-based analysis of flame/wall interactions by conducting two-dimensional simulations of premixed turbulent flames propagating head on towards a wall. They provided a quantification of the maximum wall heat flux and the minimum wall Péclet number (i.e. normalised quenching distance), which was later confirmed in three-dimensional DNS studies by Lai & Chakraborty (Reference Lai and Chakraborty2016). Bruneaux et al. (Reference Bruneaux, Akselvoll, Poinsot and Ferziger1996, Reference Bruneaux, Poinsot and Ferziger1997) conducted three-dimensional DNS of premixed flame/wall interactions in turbulent channel flows. They observed that the quenching distance decreases and the maximum heat flux increases compared with their values in the corresponding laminar flame, which are attributed to the large coherent structures that push flame elements towards the wall. Similar conclusions were reported by Alshaalan & Rutland (Reference Alshaalan and Rutland1998, Reference Alshaalan and Rutland2002) in their DNS of turbulent V-flames interacting with an isothermal inert wall. Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010) studied flame behaviour near the wall in turbulent channel flows, revealing how streak structures in the turbulent boundary layer interact with the flame and influence convective wall heat transfer. Despite the above-mentioned studies, the flame quenching characteristics over rough walls have not been reported in the literature.

In this context, turbulent boundary layer premixed flame flashback over rough walls is studied using DNS in the present work for the first time. Particularly, the features of boundary layer flashback over walls with various roughness are explored by analysing the flame morphology and flashback speed. The effects of wall roughness and combustion on the boundary layer turbulence are explored using the two-point correlations of the fluctuating velocity and wall friction resistance. The flame/wall interactions are examined in terms of the flame quenching distance and wall heat flux. The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. First, the DNS configuration featuring turbulent boundary layer premixed flame flashback over smooth and rough walls is described in § 2. Second, the results and discussion are presented in § 3. Finally, the conclusions are drawn in § 4.

2. Configuration and numerical methods

In the present work, the configuration of turbulent boundary layer premixed

![]() $\mathrm{H_2}$

/air combustion over smooth and rough walls is considered. The equivalence ratio of the reactant is

$\mathrm{H_2}$

/air combustion over smooth and rough walls is considered. The equivalence ratio of the reactant is

![]() $\phi =0.8$

, the temperature is

$\phi =0.8$

, the temperature is

![]() $T_u=500\ \mathrm{K}$

and the ambient pressure is

$T_u=500\ \mathrm{K}$

and the ambient pressure is

![]() $p_0=2\ \mathrm{atm}$

, consistent with previous experiments (Kalantari et al. Reference Kalantari, Sullivan-Lewis and McDonell2016, Reference Kalantari, Auwaijan and McDonell2019). The corresponding laminar flame speed is

$p_0=2\ \mathrm{atm}$

, consistent with previous experiments (Kalantari et al. Reference Kalantari, Sullivan-Lewis and McDonell2016, Reference Kalantari, Auwaijan and McDonell2019). The corresponding laminar flame speed is

![]() $S_L = 3.84\ \mathrm{m\,s^{-1}}$

and flame thickness is

$S_L = 3.84\ \mathrm{m\,s^{-1}}$

and flame thickness is

![]() $\delta _L = 0.202\ \mathrm{mm}$

, which are respectively calculated as

$\delta _L = 0.202\ \mathrm{mm}$

, which are respectively calculated as

![]() $S_L=-\int _{-\infty }^{+\infty } \dot \omega _F\mathrm{d}x /(\rho _u Y_F^u)$

and

$S_L=-\int _{-\infty }^{+\infty } \dot \omega _F\mathrm{d}x /(\rho _u Y_F^u)$

and

![]() $\delta _L=(T_b-T_u)/|\boldsymbol{\nabla }T|_{\textit{max}}$

(Poinsot & Veynante Reference Poinsot and Veynante2001), where

$\delta _L=(T_b-T_u)/|\boldsymbol{\nabla }T|_{\textit{max}}$

(Poinsot & Veynante Reference Poinsot and Veynante2001), where

![]() $\dot \omega _F$

is the fuel reaction rate,

$\dot \omega _F$

is the fuel reaction rate,

![]() $\rho _u$

is the density of the reactant,

$\rho _u$

is the density of the reactant,

![]() $Y_F^u$

is the fuel mass fraction of the reactant and

$Y_F^u$

is the fuel mass fraction of the reactant and

![]() $T_b$

is the product temperature. The free-stream velocity of the boundary layer is

$T_b$

is the product temperature. The free-stream velocity of the boundary layer is

![]() $U_\infty =40\ \mathrm{m\,s^{-1}}$

, which is similar to that in the near-wall region of a combustion chamber (Heitor & Whitelaw Reference Heitor and Whitelaw1986; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023).

$U_\infty =40\ \mathrm{m\,s^{-1}}$

, which is similar to that in the near-wall region of a combustion chamber (Heitor & Whitelaw Reference Heitor and Whitelaw1986; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023).

A schematic of the DNS is presented in figure 1. Two auxiliary simulations were conducted to obtain the inflow turbulence for the main simulation. In the first auxiliary simulation, the boundary layer over a flat plate transitions from laminar to turbulent flow with the trip-wire method (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang, Luo, Hawkes, Chen and Fan2021). The spatially developing turbulent boundary layer was temporally sampled at a fixed streamwise location and served as the inflow turbulence for the second auxiliary simulation. In the second auxiliary simulation, the boundary layer turbulence is modified by a rough wall. The flow was temporally sampled at a fixed streamwise location where the boundary layer turbulence reaches a quasi-steady state, which was then used as the inflow turbulence for the main DNS.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the simulation procedure for turbulent boundary layer flashback over a rough wall.

The domain size of the main DNS is

![]() $L_x\times L_y\times L_z=19.8\times 10\times 15\ \mathrm{mm^3}$

, where

$L_x\times L_y\times L_z=19.8\times 10\times 15\ \mathrm{mm^3}$

, where

![]() $L_x$

,

$L_x$

,

![]() $L_y$

and

$L_y$

and

![]() $L_z$

are the domain lengths in the streamwise,

$L_z$

are the domain lengths in the streamwise,

![]() $x$

, wall-normal,

$x$

, wall-normal,

![]() $y$

, and spanwise,

$y$

, and spanwise,

![]() $z$

, directions, respectively. The boundary conditions are non-reflecting in the

$z$

, directions, respectively. The boundary conditions are non-reflecting in the

![]() $x$

direction and periodic in the

$x$

direction and periodic in the

![]() $z$

direction. The non-reflecting outflow boundary is used at

$z$

direction. The non-reflecting outflow boundary is used at

![]() $y=L_y$

, while a no-slip condition is applied on the walls. The wall is isothermal and inert with a wall temperature of

$y=L_y$

, while a no-slip condition is applied on the walls. The wall is isothermal and inert with a wall temperature of

![]() $T_w = 500\ \mathrm{K}$

. The wall surface is described using a sinusoidal function

$T_w = 500\ \mathrm{K}$

. The wall surface is described using a sinusoidal function

where

![]() $k_w$

is the amplitude of the roughness,

$k_w$

is the amplitude of the roughness,

![]() $\alpha =2\pi x /\lambda _w$

and

$\alpha =2\pi x /\lambda _w$

and

![]() $\beta =2\pi z /\lambda _w$

are respectively the phase angles in the streamwise and spanwise directions and

$\beta =2\pi z /\lambda _w$

are respectively the phase angles in the streamwise and spanwise directions and

![]() $\lambda _w$

is the wavelength of the roughness. The present study features one smooth-wall case and two rough-wall cases. In the smooth-wall case,

$\lambda _w$

is the wavelength of the roughness. The present study features one smooth-wall case and two rough-wall cases. In the smooth-wall case,

![]() $i.e.$

case 1,

$i.e.$

case 1,

![]() $k_w$

is set to zero, while in the rough-wall cases,

$k_w$

is set to zero, while in the rough-wall cases,

![]() $\lambda _w=300\ \unicode{x03BC} \mathrm{m},\ k_w=100\ \unicode{x03BC} \mathrm{m}$

(case 2) and

$\lambda _w=300\ \unicode{x03BC} \mathrm{m},\ k_w=100\ \unicode{x03BC} \mathrm{m}$

(case 2) and

![]() $\lambda _w=600\ \unicode{x03BC} \mathrm{m},\ k_w=200\ \unicode{x03BC} \mathrm{m}$

(case 3) are considered, which are close to the characteristic scale of wall roughness caused by fuel deposition in gas turbines (Bons Reference Bons2010). The physical and numerical parameters of various cases are summarised in table 1. The grids are uniform in the streamwise and spanwise directions with

$\lambda _w=600\ \unicode{x03BC} \mathrm{m},\ k_w=200\ \unicode{x03BC} \mathrm{m}$

(case 3) are considered, which are close to the characteristic scale of wall roughness caused by fuel deposition in gas turbines (Bons Reference Bons2010). The physical and numerical parameters of various cases are summarised in table 1. The grids are uniform in the streamwise and spanwise directions with

![]() $\Delta x^+=\Delta z^+=1.6$

for all cases. The superscript ‘+’ indicates normalisation by the viscous length scale of the inflow turbulence. Stretched grids are used in the

$\Delta x^+=\Delta z^+=1.6$

for all cases. The superscript ‘+’ indicates normalisation by the viscous length scale of the inflow turbulence. Stretched grids are used in the

![]() $y$

direction with

$y$

direction with

![]() $\Delta y^+_{\textit{min}}=0.6$

near the wall. There are 15 points within

$\Delta y^+_{\textit{min}}=0.6$

near the wall. There are 15 points within

![]() $y^+\lt 10$

to satisfy the requirements for resolving boundary layer turbulence (Moser, Kim & Mansour Reference Moser, Kim and Mansour1999; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Luo and Fan2021; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang, Luo, Hawkes, Chen and Fan2021). The grid is gradually stretched in the wall-normal direction. For the rough-wall cases, a body-fitted grid is employed near the sinusoidal roughness, as shown in figure 1. There are 15 and 30 grids within each wavelength in both the streamwise and spanwise directions for case 2 and case 3, respectively. The resultant grid number is

$y^+\lt 10$

to satisfy the requirements for resolving boundary layer turbulence (Moser, Kim & Mansour Reference Moser, Kim and Mansour1999; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Luo and Fan2021; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang, Luo, Hawkes, Chen and Fan2021). The grid is gradually stretched in the wall-normal direction. For the rough-wall cases, a body-fitted grid is employed near the sinusoidal roughness, as shown in figure 1. There are 15 and 30 grids within each wavelength in both the streamwise and spanwise directions for case 2 and case 3, respectively. The resultant grid number is

![]() $N_x\times N_y\times N_z=990\times 480\times 750$

. The flame structures are well resolved with the grids as shown in Appendix A. Three non-reacting DNS cases were also performed for comparison by turning off the chemical reaction, denoted as cases NR1, NR2 and NR3.

$N_x\times N_y\times N_z=990\times 480\times 750$

. The flame structures are well resolved with the grids as shown in Appendix A. Three non-reacting DNS cases were also performed for comparison by turning off the chemical reaction, denoted as cases NR1, NR2 and NR3.

Table 1. The physical and numerical parameters of various cases.

The domain size of the first auxiliary simulation is

![]() $L_x^{a1}\times L_y^{a1}\times L_z^{a1}=160\times 15\times 15\ \mathrm{mm^3}$

. The boundary conditions are similar to those in the main DNS, which, however, employs a smooth wall. The grids are uniform in the streamwise and spanwise directions with

$L_x^{a1}\times L_y^{a1}\times L_z^{a1}=160\times 15\times 15\ \mathrm{mm^3}$

. The boundary conditions are similar to those in the main DNS, which, however, employs a smooth wall. The grids are uniform in the streamwise and spanwise directions with

![]() $\Delta x^+=7.8$

and

$\Delta x^+=7.8$

and

![]() $\Delta z^+=5.8$

. Stretched grids with

$\Delta z^+=5.8$

. Stretched grids with

![]() $\Delta y_{\textit{min}}^+=0.9$

at the wall are used in the

$\Delta y_{\textit{min}}^+=0.9$

at the wall are used in the

![]() $y$

direction. There are 11 points within

$y$

direction. There are 11 points within

![]() $y^+\lt 10$

. The resultant grid number is

$y^+\lt 10$

. The resultant grid number is

![]() $N_x^{a1}\times N_y^{a1}\times N_z^{a1}=1600\times 256\times 200$

. The axial plane with a friction Reynolds number of

$N_x^{a1}\times N_y^{a1}\times N_z^{a1}=1600\times 256\times 200$

. The axial plane with a friction Reynolds number of

![]() $Re_\tau = 360$

was temporally sampled at a streamwise location of

$Re_\tau = 360$

was temporally sampled at a streamwise location of

![]() $x = 120\ \mathrm{mm}$

to provide the inflow for the second auxiliary simulation. The sampled turbulence has been validated in our previous studies (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023).

$x = 120\ \mathrm{mm}$

to provide the inflow for the second auxiliary simulation. The sampled turbulence has been validated in our previous studies (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023).

The second auxiliary simulation has the same boundary conditions and grid resolution as the main DNS. The domain size and grid number of the second auxiliary simulations are

![]() $L_x^{a2}\times L_y^{a2}\times L_z^{a2}=21\times 10\times 15\ \mathrm{mm^3}$

and

$L_x^{a2}\times L_y^{a2}\times L_z^{a2}=21\times 10\times 15\ \mathrm{mm^3}$

and

![]() $N_x^{a2}\times N_y^{a2}\times N_z^{a2}=1050\times 480\times 750$

, respectively. The axial plane of

$N_x^{a2}\times N_y^{a2}\times N_z^{a2}=1050\times 480\times 750$

, respectively. The axial plane of

![]() $x = 17.4\ \mathrm{mm}$

was temporally sampled to provide the inflow for the main DNS. The profiles of the mean streamwise velocity for the inflow of the main DNS are shown in figure 2. The classical wall law and the DNS data of incompressible turbulent boundary layer over a smooth wall at the same friction Reynolds number as Schlatter & Örlü (Reference Schlatter and Örlü2010) are also presented for comparison. As can be seen, the streamwise velocity profile from the present DNS with a smooth wall aligns well with that in Schlatter & Örlü (Reference Schlatter and Örlü2010). In the rough-wall cases, the presence of roughness results in a downward shift of the viscous-scaled mean velocity profile, and the velocity defect increases with increasing roughness amplitude. The mean velocity profiles follow the logarithmic law beyond a certain position. These observations are consistent with previous studies of incompressible boundary layers over rough walls (Chan et al. Reference Chan, MacDonald, Chung, Hutchins and Ooi2015; MacDonald et al. Reference MacDonald, Chan, Chung, Hutchins and Ooi2016; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Xu, Sung and Huang2020; Abdelaziz et al. Reference Abdelaziz, Djenidi, Ghayesh and Chin2022).

$x = 17.4\ \mathrm{mm}$

was temporally sampled to provide the inflow for the main DNS. The profiles of the mean streamwise velocity for the inflow of the main DNS are shown in figure 2. The classical wall law and the DNS data of incompressible turbulent boundary layer over a smooth wall at the same friction Reynolds number as Schlatter & Örlü (Reference Schlatter and Örlü2010) are also presented for comparison. As can be seen, the streamwise velocity profile from the present DNS with a smooth wall aligns well with that in Schlatter & Örlü (Reference Schlatter and Örlü2010). In the rough-wall cases, the presence of roughness results in a downward shift of the viscous-scaled mean velocity profile, and the velocity defect increases with increasing roughness amplitude. The mean velocity profiles follow the logarithmic law beyond a certain position. These observations are consistent with previous studies of incompressible boundary layers over rough walls (Chan et al. Reference Chan, MacDonald, Chung, Hutchins and Ooi2015; MacDonald et al. Reference MacDonald, Chan, Chung, Hutchins and Ooi2016; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Xu, Sung and Huang2020; Abdelaziz et al. Reference Abdelaziz, Djenidi, Ghayesh and Chin2022).

Figure 2. Profiles of the mean streamwise velocity along

![]() $y^+$

for the inflow in the three main DNS cases.

$y^+$

for the inflow in the three main DNS cases.

In the main DNS, the scalar fields were superimposed on top of the boundary layer turbulence with the solutions of a premixed flame in a two-dimensional laminar boundary layer, characterised by a free-stream velocity of

![]() $40\ \mathrm{m\,s^{-1}}$

and a boundary layer thickness of

$40\ \mathrm{m\,s^{-1}}$

and a boundary layer thickness of

![]() $\delta =0.2\ \mathrm{mm}$

, as illustrated in figure 3. The details of the two-dimensional laminar flame have been described in our previous work (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023). The two-dimensional scalar fields are mapped in the spanwise direction to generate the three-dimensional scalar fields, which are then interpolated onto the grid of the main DNS at

$\delta =0.2\ \mathrm{mm}$

, as illustrated in figure 3. The details of the two-dimensional laminar flame have been described in our previous work (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023). The two-dimensional scalar fields are mapped in the spanwise direction to generate the three-dimensional scalar fields, which are then interpolated onto the grid of the main DNS at

![]() $t^*=0$

. Here,

$t^*=0$

. Here,

![]() $t^*=t/(\delta _L/S_L)$

represents the non-dimensional time. Flashback occurs due to the thickening of the boundary layer and the increase in flame speed caused by turbulence. After

$t^*=t/(\delta _L/S_L)$

represents the non-dimensional time. Flashback occurs due to the thickening of the boundary layer and the increase in flame speed caused by turbulence. After

![]() $t^*=3.8$

, the turbulent flame propagates upstream in a quasi-stationary manner. The difference in the mean flame between

$t^*=3.8$

, the turbulent flame propagates upstream in a quasi-stationary manner. The difference in the mean flame between

![]() $t^*=3.8$

to

$t^*=3.8$

to

![]() $11.4$

is small as shown in Appendix B. Therefore, the flame statistics presented in this paper are collected within this range of time.

$11.4$

is small as shown in Appendix B. Therefore, the flame statistics presented in this paper are collected within this range of time.

Figure 3. Distributions of (a) temperature, mass fraction of (b) hydrogen and (c) oxygen for the two-dimensional boundary layer flame.

The simulations were performed using the DNS code EBIdnsFoam (Zirwes et al. Reference Zirwes, Sontheimer, Zhang, Abdelsamie, Pérez, Stein, Im, Kronenburg and Bockhorn2023), which was developed based on the open-source code OpenFOAM (Weller et al. Reference Weller, Tabor, Jasak and Fureby1998) and Cantera (Goodwin, Moffat & Speth Reference Goodwin, Moffat and Speth2018). A mixture-averaged model was employed for calculating transport properties, which accounts for the differential diffusion through the disparity of heat and species diffusion. The mixture-averaged model has also been widely used in DNS of turbulent combustion (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Pérez, Guo, Im and Wang2022; Rieth, Gruber & Chen Reference Rieth, Gruber and Chen2023). EBIdnsFoam has been extensively validated through comparisons with data from experiments and other state-of-the-art DNS codes (Zirwes et al. Reference Zirwes, Zhang, Habisreuther, Hansinger, Bockhorn, Pfitzner and Trimis2020, Reference Zirwes, Sontheimer, Zhang, Abdelsamie, Pérez, Stein, Im, Kronenburg and Bockhorn2023; Chang et al. Reference Chang, Wang, Hawkes, Luo and Fan2024). Spatial gradients are discretised using a fourth-order interpolation method and time is discretised implicitly using the second-order backward Euler method. The maximum convective Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy number remains below

![]() $0.1$

. A 9 species and 19-step mechanism for hydrogen combustion proposed by Li et al. (Reference Li, Zhao, Kazakov and Dryer2004) has been adopted as the chemistry model.

$0.1$

. A 9 species and 19-step mechanism for hydrogen combustion proposed by Li et al. (Reference Li, Zhao, Kazakov and Dryer2004) has been adopted as the chemistry model.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. General characteristics of the boundary layer flashback

The temporal evolution of the flame and boundary layer turbulence is illustrated in figure 4. The flame front is denoted by the isosurface of

![]() $c=0.7$

, where

$c=0.7$

, where

![]() $c$

is the progress variable defined as

$c$

is the progress variable defined as

![]() $c= (Y_{H_2}-Y_{H_2,u} )/ (Y_{H_2,b}-Y_{H_2,u} )$

. Here,

$c= (Y_{H_2}-Y_{H_2,u} )/ (Y_{H_2,b}-Y_{H_2,u} )$

. Here,

![]() $Y_{H_2,b}$

and

$Y_{H_2,b}$

and

![]() $Y_{H_2,u}$

represent the mass fractions of hydrogen in the products and reactants, respectively. Coherent vortical structures are identified using the isosurface of

$Y_{H_2,u}$

represent the mass fractions of hydrogen in the products and reactants, respectively. Coherent vortical structures are identified using the isosurface of

![]() $\lambda _2=-2.0\times 10^8\ \mathrm{s^{-2}}$

, where

$\lambda _2=-2.0\times 10^8\ \mathrm{s^{-2}}$

, where

![]() $\lambda _2$

represents the second eigenvalue of

$\lambda _2$

represents the second eigenvalue of

![]() $\boldsymbol{S}^2+\boldsymbol{\varOmega }^2$

(Jeong & Hussain Reference Jeong and Hussain1995), with

$\boldsymbol{S}^2+\boldsymbol{\varOmega }^2$

(Jeong & Hussain Reference Jeong and Hussain1995), with

![]() $\boldsymbol{S}$

and

$\boldsymbol{S}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{\varOmega }$

representing the symmetric and antisymmetric parts of the velocity gradient tensor

$\boldsymbol{\varOmega }$

representing the symmetric and antisymmetric parts of the velocity gradient tensor

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{u}$

, respectively. It is seen that the flame propagates upstream along the low-velocity region near the wall, indicating the occurrence of boundary layer flashback. Due to the much higher streamwise flow velocity outside the boundary layer compared with the laminar flame speed, the flame front is tilted. Complex interactions between the flame and boundary layer turbulence can be observed in all cases. Specifically, the flame front is significantly wrinkled by the boundary layer turbulence, while turbulence is also modified by the flame. The coherent vortical structures near the flame are lifted compared with those in the fresh gas, consistent with previous studies (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023). In the rough-wall cases, more small-scale coherent vortical structures are observed compared with the smooth-wall case.

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{u}$

, respectively. It is seen that the flame propagates upstream along the low-velocity region near the wall, indicating the occurrence of boundary layer flashback. Due to the much higher streamwise flow velocity outside the boundary layer compared with the laminar flame speed, the flame front is tilted. Complex interactions between the flame and boundary layer turbulence can be observed in all cases. Specifically, the flame front is significantly wrinkled by the boundary layer turbulence, while turbulence is also modified by the flame. The coherent vortical structures near the flame are lifted compared with those in the fresh gas, consistent with previous studies (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023). In the rough-wall cases, more small-scale coherent vortical structures are observed compared with the smooth-wall case.

Figure 4. Temporal evolution of the premixed flame in (a) case 1, (b) case 2 and (c) case 3. The flame front is represented by the red isosurface. The boundary layer turbulence (characterised by

![]() $\lambda _2=-2.0\times 10^8\ \mathrm{s^{-2}}$

) is shown and coloured by the streamwise velocity.

$\lambda _2=-2.0\times 10^8\ \mathrm{s^{-2}}$

) is shown and coloured by the streamwise velocity.

Figure 5 presents a top view of the flame front at

![]() $t^*=7.6$

, superimposed with the distribution of streamwise velocity in the plane of

$t^*=7.6$

, superimposed with the distribution of streamwise velocity in the plane of

![]() $y^+=20$

. High- and low-speed streaks are evident in the near-wall region in all cases. It is seen that, as the near-wall turbulence is disrupted by the wall roughness, the spatial scale of the streaks is significantly reduced in the rough-wall cases compared with the smooth-wall case, particularly in case 3 with the largest roughness height. Regions of backflow with negative streamwise velocity appear upstream of the flame in all cases, as observed in previous studies (Heeger et al. Reference Heeger, Gordon, Tummers, Sattelmayer and Dreizler2010; Eichler & Sattelmayer Reference Eichler and Sattelmayer2012; Gruber et al. Reference Gruber, Chen, Valiev and Law2012; Ebi & Clemens Reference Ebi and Clemens2016; Schneider & Steinberg Reference Schneider and Steinberg2020; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023). These are caused by the combustion-induced adverse pressure gradient near the leading edge of the flame bulges. Additionally, influenced by small-scale coherent vortical structures, the flame in the rough-wall cases becomes more wrinkled compared with the smooth-wall case, particularly in the near-wall region.

$y^+=20$

. High- and low-speed streaks are evident in the near-wall region in all cases. It is seen that, as the near-wall turbulence is disrupted by the wall roughness, the spatial scale of the streaks is significantly reduced in the rough-wall cases compared with the smooth-wall case, particularly in case 3 with the largest roughness height. Regions of backflow with negative streamwise velocity appear upstream of the flame in all cases, as observed in previous studies (Heeger et al. Reference Heeger, Gordon, Tummers, Sattelmayer and Dreizler2010; Eichler & Sattelmayer Reference Eichler and Sattelmayer2012; Gruber et al. Reference Gruber, Chen, Valiev and Law2012; Ebi & Clemens Reference Ebi and Clemens2016; Schneider & Steinberg Reference Schneider and Steinberg2020; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023). These are caused by the combustion-induced adverse pressure gradient near the leading edge of the flame bulges. Additionally, influenced by small-scale coherent vortical structures, the flame in the rough-wall cases becomes more wrinkled compared with the smooth-wall case, particularly in the near-wall region.

Figure 5. A top view of the flame front at

![]() $t^*=7.6$

in (a) case 1, (b) case 2 and (c) case 3. The distribution of streamwise velocity in the plane

$t^*=7.6$

in (a) case 1, (b) case 2 and (c) case 3. The distribution of streamwise velocity in the plane

![]() $y^+=20$

is overlaid.

$y^+=20$

is overlaid.

The wrinkling of the flame front can be characterised by the flame curvature

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol {n}$

. The conditional mean of

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol {n}$

. The conditional mean of

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol {n}$

along the

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol {n}$

along the

![]() $y$

direction and its probability density function (PDF) at several specific

$y$

direction and its probability density function (PDF) at several specific

![]() $y$

values are shown in figure 6. Here,

$y$

values are shown in figure 6. Here,

![]() $\boldsymbol {n}$

is the flame normal vector defined on the flame surface as

$\boldsymbol {n}$

is the flame normal vector defined on the flame surface as

![]() $\boldsymbol {n} = -{\boldsymbol{\nabla }c}/{|\boldsymbol{\nabla }c|}$

, which points toward the reactant mixture. A schematic of the flame normal vector is presented in figure 7(a). Note that the flame normal is a vector, and the value of its component varies in the range of −1 and 1. The flame curvature

$\boldsymbol {n} = -{\boldsymbol{\nabla }c}/{|\boldsymbol{\nabla }c|}$

, which points toward the reactant mixture. A schematic of the flame normal vector is presented in figure 7(a). Note that the flame normal is a vector, and the value of its component varies in the range of −1 and 1. The flame curvature

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol {n}$

is positive (negative) when the centre of curvature is in the products (reactants). In the smooth-wall case, positive curvature predominates in the region from

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol {n}$

is positive (negative) when the centre of curvature is in the products (reactants). In the smooth-wall case, positive curvature predominates in the region from

![]() $y=0.06\ \mathrm{mm}$

to

$y=0.06\ \mathrm{mm}$

to

![]() $y=0.4\ \mathrm{mm}$

, which corresponds to the buffer layer of the turbulent boundary layer (

$y=0.4\ \mathrm{mm}$

, which corresponds to the buffer layer of the turbulent boundary layer (

![]() $5\lt y^+\lt 30$

), with the mean curvature being the highest at

$5\lt y^+\lt 30$

), with the mean curvature being the highest at

![]() $y=0.13\ \mathrm{mm}$

(

$y=0.13\ \mathrm{mm}$

(

![]() $y^+=10$

). In the outer layer, the mean curvature levels off and becomes zero. In the rough-wall cases, the maximum mean curvature is lower compared with the smooth-wall case, and its corresponding location is further away from the wall. The PDF shows that the distribution of curvature in the rough-wall cases is wider than that in the smooth-wall case, which is more evident in regions with low

$y^+=10$

). In the outer layer, the mean curvature levels off and becomes zero. In the rough-wall cases, the maximum mean curvature is lower compared with the smooth-wall case, and its corresponding location is further away from the wall. The PDF shows that the distribution of curvature in the rough-wall cases is wider than that in the smooth-wall case, which is more evident in regions with low

![]() $y$

values. This is due to the presence of more small-scale structures of the turbulence and flame near the wall in the rough-wall cases.

$y$

values. This is due to the presence of more small-scale structures of the turbulence and flame near the wall in the rough-wall cases.

Figure 6. (a) Conditional mean of the flame curvature as a function of

![]() $y$

in the three main cases, and the PDF of the flame curvature at (b)

$y$

in the three main cases, and the PDF of the flame curvature at (b)

![]() $y=0.06\ \mathrm{mm}$

, (c)

$y=0.06\ \mathrm{mm}$

, (c)

![]() $y=0.26\ \mathrm{mm}$

and (d)

$y=0.26\ \mathrm{mm}$

and (d)

![]() $y=1.03\ \mathrm{mm}$

.

$y=1.03\ \mathrm{mm}$

.

Figure 7. (a) Schematic of the flame normal vector. (b) The components of mean flame normal vector

![]() $\overline {n}_i$

as a function of

$\overline {n}_i$

as a function of

![]() $y$

in the three cases. (c) Schematic of the leading point and penetration distance. The mean flame front is denoted by

$y$

in the three cases. (c) Schematic of the leading point and penetration distance. The mean flame front is denoted by

![]() $\overline {c}$

= 0.7.

$\overline {c}$

= 0.7.

It is interesting to observe that the inclination angle of the flame front in the rough-wall cases is slightly larger than that in the smooth-wall case, which is further analysed thorough the flame normal vector

![]() $\boldsymbol {n}$

. The mean values of flame normal vector components (

$\boldsymbol {n}$

. The mean values of flame normal vector components (

![]() $\overline {n}_i$

) along the

$\overline {n}_i$

) along the

![]() $y$

direction are shown in figure 7(b). It can be seen that

$y$

direction are shown in figure 7(b). It can be seen that

![]() $\overline {n}_y$

in case 2 and case 3 is always lower than that in case 1 when away from the wall, indicating a larger inclination angle of the mean flame in the rough-wall cases, which can be estimated as

$\overline {n}_y$

in case 2 and case 3 is always lower than that in case 1 when away from the wall, indicating a larger inclination angle of the mean flame in the rough-wall cases, which can be estimated as

![]() $\alpha = \arccos (\overline {n}_y)$

. In the near-wall region, as

$\alpha = \arccos (\overline {n}_y)$

. In the near-wall region, as

![]() $y$

increases,

$y$

increases,

![]() $\overline {n}_y$

changes from negative to positive around

$\overline {n}_y$

changes from negative to positive around

![]() $y=0.2\ \mathrm{mm}$

in all cases. Notably,

$y=0.2\ \mathrm{mm}$

in all cases. Notably,

![]() $\overline {n}_x$

reaches a minimum value of −1 when

$\overline {n}_x$

reaches a minimum value of −1 when

![]() $\overline {n}_y$

is zero, so that the mean flame normal is parallel to the streamwise direction and points towards the negative

$\overline {n}_y$

is zero, so that the mean flame normal is parallel to the streamwise direction and points towards the negative

![]() $x$

direction. The location on the mean flame front featured by

$x$

direction. The location on the mean flame front featured by

![]() $\overline {n}_x$

= −1 is referred to as the leading point in the average sense, and its distance from the wall is called the penetration distance (Lewis & Von Elbe Reference Lewis and von Elbe1943; Von Elbe & Mentser Reference Von Elbe and Mentser1945; Kalantari, Sullivan-Lewis & McDonell Reference Kalantari, Sullivan-Lewis and McDonell2016), as illustrated in figure 7(c). It can be seen from figure 7(b) that case 1 has the lowest penetration distance, followed by case 2, and case 3 features the highest value of penetration distance.

$\overline {n}_x$

= −1 is referred to as the leading point in the average sense, and its distance from the wall is called the penetration distance (Lewis & Von Elbe Reference Lewis and von Elbe1943; Von Elbe & Mentser Reference Von Elbe and Mentser1945; Kalantari, Sullivan-Lewis & McDonell Reference Kalantari, Sullivan-Lewis and McDonell2016), as illustrated in figure 7(c). It can be seen from figure 7(b) that case 1 has the lowest penetration distance, followed by case 2, and case 3 features the highest value of penetration distance.

To quantify the flashback behaviour, we examined the time evolution of the mean streamwise coordinate of the most upstream position of the flame front,

![]() $P_x$

, as shown in figure 8. It is seen that,

$P_x$

, as shown in figure 8. It is seen that,

![]() $P_x$

monotonically decreases over time in all cases, indicating upstream propagation of the flame. The slope of the curve characterises the flame propagation velocity. Notably, the propagation velocity is the highest in case 1 and the lowest in case 3.

$P_x$

monotonically decreases over time in all cases, indicating upstream propagation of the flame. The slope of the curve characterises the flame propagation velocity. Notably, the propagation velocity is the highest in case 1 and the lowest in case 3.

Figure 8. Time evolution of the streamwise position of the average leading point of the flame front.

Next, the flame flashback speed is analysed, which is consistent with the absolute flame speed relative to the laboratory flame (Poinsot & Veynante Reference Poinsot and Veynante2001; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Wang, Chen, Luo and Fan2023), and is defined as

![]() $S_f=S_d+\boldsymbol {u}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol {n}$

. The displacement speed

$S_f=S_d+\boldsymbol {u}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol {n}$

. The displacement speed

![]() $S_d$

represents the speed of the flame front relative to the flow in the flame normal direction and is defined as (Chen & Im Reference Chen and Im1998; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Hawkes and Chen2017a

,

Reference Wang, Hawkes, Chen, Zhou, Li and Aldénb

)

$S_d$

represents the speed of the flame front relative to the flow in the flame normal direction and is defined as (Chen & Im Reference Chen and Im1998; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Hawkes and Chen2017a

,

Reference Wang, Hawkes, Chen, Zhou, Li and Aldénb

)

where

![]() ${\dot \omega }_c$

and

${\dot \omega }_c$

and

![]() $D_c$

denote the reaction rate and mass diffusivity of the progress variable, respectively, and

$D_c$

denote the reaction rate and mass diffusivity of the progress variable, respectively, and

![]() $\boldsymbol {u}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol {n}$

represents the flow velocity in the flame normal direction. The mean values of the flame flashback speed at the penetration distance for various cases are shown in table 2. The values of

$\boldsymbol {u}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol {n}$

represents the flow velocity in the flame normal direction. The mean values of the flame flashback speed at the penetration distance for various cases are shown in table 2. The values of

![]() $S_f$

,

$S_f$

,

![]() $S_d$

and

$S_d$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol { u}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol {n}$

are all density weighted to account for thermal expansion effects across the flame, and normalised by

$\boldsymbol { u}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol {n}$

are all density weighted to account for thermal expansion effects across the flame, and normalised by

![]() $S_L$

. The statistics were collected in the flame region. It can be seen that the flame displacement speed at the penetration distance is similar in all cases and that

$S_L$

. The statistics were collected in the flame region. It can be seen that the flame displacement speed at the penetration distance is similar in all cases and that

![]() $\boldsymbol {u} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol {n}$

is the largest in case 1, followed by case 2, and is the smallest in case 3, resulting the highest flashback speed in case 1, and the lowest in case 3.

$\boldsymbol {u} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol {n}$

is the largest in case 1, followed by case 2, and is the smallest in case 3, resulting the highest flashback speed in case 1, and the lowest in case 3.

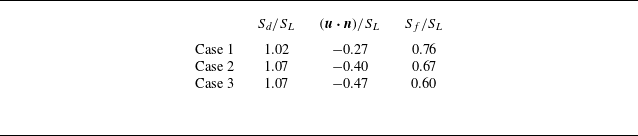

Table 2. Mean value of

![]() $S_d/S_L$

,

$S_d/S_L$

,

![]() $ ( \boldsymbol {u} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol {n} )/S_L$

and

$ ( \boldsymbol {u} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol {n} )/S_L$

and

![]() $S_f/S_L$

at the penetration distance.

$S_f/S_L$

at the penetration distance.

Note that, although the streamwise velocity near the rough wall is reduced compared with the smooth wall in the non-reacting boundary layer, the penetration distance is larger in the rough-wall case, resulting in a higher local flow velocity at the leading point of the flame. To compare the penetration distance of various cases intuitively, the contour lines of the mean flame front denoted as

![]() $\bar {c}$

= 0.7 are presented in figure 9. The mean progress variable

$\bar {c}$

= 0.7 are presented in figure 9. The mean progress variable

![]() $\bar {c}$

is obtained through spanwise and time averaging. Prior to time averaging, the streamwise coordinates were shifted at each time instant, i.e.

$\bar {c}$

is obtained through spanwise and time averaging. Prior to time averaging, the streamwise coordinates were shifted at each time instant, i.e.

![]() $x^\prime =x-P_x$

, to ensure that the mean position of the flame leading point remains at

$x^\prime =x-P_x$

, to ensure that the mean position of the flame leading point remains at

![]() $x^\prime = 0$

. It can be observed that the penetration distance is the lowest in case 1, and the highest in case 3. It is speculated that heat loss is the primary factor affecting the penetration distance. In the near-wall region, the fuel reaction rate decreases due to wall heat loss, causing a reduction in the flame propagation speed. As a result, the flame front is bent and a leading point is formed near the wall. In this study, wall heat loss increases with wall roughness, which will be discussed in § 3.3. Therefore, the flame is further weakened near the wall and the penetration distance is increased as the wall roughness increases.

$x^\prime = 0$

. It can be observed that the penetration distance is the lowest in case 1, and the highest in case 3. It is speculated that heat loss is the primary factor affecting the penetration distance. In the near-wall region, the fuel reaction rate decreases due to wall heat loss, causing a reduction in the flame propagation speed. As a result, the flame front is bent and a leading point is formed near the wall. In this study, wall heat loss increases with wall roughness, which will be discussed in § 3.3. Therefore, the flame is further weakened near the wall and the penetration distance is increased as the wall roughness increases.

Figure 9. The contour lines of the mean flame front with

![]() $\bar {c}$

= 0.7 for various cases.

$\bar {c}$

= 0.7 for various cases.

Concluding this subsection, it is noted that the characteristics of boundary layer turbulence is influenced by wall roughness. Particularly, the scales of the vortical structures and the near-wall streaks in the rough-wall cases are reduced compared with those in the smooth-wall case. The change in turbulent structures also impacts the flame flashback behaviour. It was found that the penetration distance over rough walls is generally larger than that over smooth walls, so that the flashback propensity is attenuated in the rough-wall cases, consistent with the work of laminar flashback over rough walls by Ding et al. (Reference Ding, Huang, Han and Valiev2021). The results also have significant implications for modelling practical combustion devices, where the presence of wall roughness is inevitable. Obviously, modelling approaches that do not resolve the wall roughness structures will likely predict the wrong behaviour of flame flashback in turbulent boundary layer.

3.2. The effects of wall roughness and combustion on the turbulent boundary layer

The turbulent boundary layer is influenced by wall roughness and combustion, which is examined in this subsection. Figure 10 shows the instantaneous streamwise velocity distribution in a typical

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $y$

plane, with the white line indicating the flame front. The mean streamwise velocity distribution is also presented. Backflow regions with negative streamwise velocity were observed upstream of the flame front in all cases, which is attributed to the adverse pressure gradient induced by combustion, leading to boundary layer separation. This is consistent with the previous studies by Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Chen, Valiev and Law2012) and Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023). On the product side, flow acceleration occurs due to thermal expansion. In the rough-wall cases, the flame front becomes more wrinkled due to the interaction with boundary layer turbulence, which is consistent with the observation in figure 5.

$y$

plane, with the white line indicating the flame front. The mean streamwise velocity distribution is also presented. Backflow regions with negative streamwise velocity were observed upstream of the flame front in all cases, which is attributed to the adverse pressure gradient induced by combustion, leading to boundary layer separation. This is consistent with the previous studies by Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Chen, Valiev and Law2012) and Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023). On the product side, flow acceleration occurs due to thermal expansion. In the rough-wall cases, the flame front becomes more wrinkled due to the interaction with boundary layer turbulence, which is consistent with the observation in figure 5.

Figure 10. (a) Instantaneous distribution of the streamwise velocity in a typical

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $y$

plane at

$y$

plane at

![]() $t^*=7.6$

for the various cases. The purple line represents the flame front. (b) The mean streamwise velocity distribution.

$t^*=7.6$

for the various cases. The purple line represents the flame front. (b) The mean streamwise velocity distribution.

Figure 11 shows the profiles of the mean streamwise velocity along the

![]() $y$

direction for various cases. Three streamwise positions were considered: upstream of the flame front (

$y$

direction for various cases. Three streamwise positions were considered: upstream of the flame front (

![]() $x^\prime =-2\ \mathrm{mm}$

), at the average leading point of the flame front (

$x^\prime =-2\ \mathrm{mm}$

), at the average leading point of the flame front (

![]() $x^\prime =0$

) and downstream of the flame front (

$x^\prime =0$

) and downstream of the flame front (

![]() $x^\prime =2\ \mathrm{mm}$

). The mean streamwise velocity in the upstream region of

$x^\prime =2\ \mathrm{mm}$

). The mean streamwise velocity in the upstream region of

![]() $x^\prime =-2\ \mathrm{mm}$

is negative near the wall for all cases, where the phenomenon of backflow occurs. Note that the presence of backflow regions is related to flame flashback. Therefore, when predicting turbulent boundary layer flashback, the interaction between the flame and boundary layer turbulence cannot be neglected. In the downstream region of

$x^\prime =-2\ \mathrm{mm}$

is negative near the wall for all cases, where the phenomenon of backflow occurs. Note that the presence of backflow regions is related to flame flashback. Therefore, when predicting turbulent boundary layer flashback, the interaction between the flame and boundary layer turbulence cannot be neglected. In the downstream region of

![]() $x^\prime =2\ \mathrm{mm}$

, the mean velocity increases due to the flow acceleration by combustion.

$x^\prime =2\ \mathrm{mm}$

, the mean velocity increases due to the flow acceleration by combustion.

Figure 11. The profiles of the mean streamwise velocity along the

![]() $y$

direction for at (a)

$y$

direction for at (a)

![]() $x^\prime$

= −2 mm, (b)

$x^\prime$

= −2 mm, (b)

![]() $x^\prime$

= 0 and (c)

$x^\prime$

= 0 and (c)

![]() $x^\prime$

= 2 mm for various cases.

$x^\prime$

= 2 mm for various cases.

The boundary layer over a smooth wall is characterised by packets of hairpin vortices occurring in groups with characteristic inclination angles, which induce low-speed streaks with regular spanwise spacing (Townsend Reference Townsend1976; Head & Bandyopadhyay Reference Head and Bandyopadhyay1981). Volino et al. (Reference Volino, Schultz and Flack2007) found that hairpin packets are a prominent feature in both smooth- and rough-wall flows. The properties of hairpin packets and streak structures can be quantified by the two-point correlation coefficients of the fluctuation velocity. The two-point correlation coefficient in the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $y$

plane at the wall-normal position

$y$

plane at the wall-normal position

![]() $y_{\textit{ref}}$

can be defined as (Volino et al. Reference Volino, Schultz and Flack2007)

$y_{\textit{ref}}$

can be defined as (Volino et al. Reference Volino, Schultz and Flack2007)

\begin{align} R_{\phi \psi }\left ( y_{\textit{ref}} \right ) =\frac {\overline { \phi \left ( x,y_{\textit{ref}}\right )\psi \left ( x+\Delta x,y_{\textit{ref}}+\Delta y\right ) } }{\sigma _\phi \left (y_{\textit{ref}}\right )\sigma _\psi \left ( y_{\textit{ref}}+\Delta y\right )}, \end{align}

\begin{align} R_{\phi \psi }\left ( y_{\textit{ref}} \right ) =\frac {\overline { \phi \left ( x,y_{\textit{ref}}\right )\psi \left ( x+\Delta x,y_{\textit{ref}}+\Delta y\right ) } }{\sigma _\phi \left (y_{\textit{ref}}\right )\sigma _\psi \left ( y_{\textit{ref}}+\Delta y\right )}, \end{align}

where

![]() $\phi$

and

$\phi$

and

![]() $\psi$

are the quantities of interest at two locations separated respectively in the streamwise and wall-normal directions by

$\psi$

are the quantities of interest at two locations separated respectively in the streamwise and wall-normal directions by

![]() $\Delta x$

and

$\Delta x$

and

![]() $\Delta y$

, and

$\Delta y$

, and

![]() $\sigma _\phi$

and

$\sigma _\phi$

and

![]() $\sigma _\psi$

are the standard deviations of

$\sigma _\psi$

are the standard deviations of

![]() $\phi$

and

$\phi$

and

![]() $\psi$

at

$\psi$

at

![]() $y_{\textit{ref}}$

and

$y_{\textit{ref}}$

and

![]() $y_{\textit{ref}}+\Delta y$

, respectively. The overbar indicates the correlations were averaged among location pairs with the same

$y_{\textit{ref}}+\Delta y$

, respectively. The overbar indicates the correlations were averaged among location pairs with the same

![]() $\Delta x$

and

$\Delta x$

and

![]() $\Delta y$

. Correlations of the fluctuation velocity in the streamwise direction (

$\Delta y$

. Correlations of the fluctuation velocity in the streamwise direction (

![]() $R_{uu}$

) at three wall-normal positions i.e.

$R_{uu}$

) at three wall-normal positions i.e.

![]() $y_{\textit{ref}}^+$

= 20, 40 and 80 are considered. In the non-reacting cases, the statistics are obtained from the entire streamwise region and averaged both in the spanwise direction and temporally. In the reacting cases, the statistics are taken at

$y_{\textit{ref}}^+$

= 20, 40 and 80 are considered. In the non-reacting cases, the statistics are obtained from the entire streamwise region and averaged both in the spanwise direction and temporally. In the reacting cases, the statistics are taken at

![]() $2\ \mathrm{mm}$

upstream of the average leading point of the flame front, i.e.

$2\ \mathrm{mm}$

upstream of the average leading point of the flame front, i.e.

![]() $x^\prime = -2\ \mathrm{mm}$

, and are also averaged in the spanwise direction and temporally.

$x^\prime = -2\ \mathrm{mm}$

, and are also averaged in the spanwise direction and temporally.

Contours

![]() $R_{uu}$

are shown in figures 12 and 13 for the non-reacting and reacting cases, respectively. The non-reacting smooth-wall turbulent boundary layer has been the subject of extensive studies, in which ejections originating from the viscous sublayer promote the formation of high- and low-speed streaks that dominate momentum transport. Therefore, the contour of

$R_{uu}$

are shown in figures 12 and 13 for the non-reacting and reacting cases, respectively. The non-reacting smooth-wall turbulent boundary layer has been the subject of extensive studies, in which ejections originating from the viscous sublayer promote the formation of high- and low-speed streaks that dominate momentum transport. Therefore, the contour of

![]() $R_{uu}$

is narrow and elongated in the streamwise direction at

$R_{uu}$

is narrow and elongated in the streamwise direction at

![]() $y_{\textit{ref}}^+=20$

. As

$y_{\textit{ref}}^+=20$

. As

![]() $y_{\textit{ref}}$

moves away from the wall, the contours of

$y_{\textit{ref}}$

moves away from the wall, the contours of

![]() $R_{uu}$

shorten in the streamwise direction and lengthen in the wall-normal direction. Near the wall (

$R_{uu}$

shorten in the streamwise direction and lengthen in the wall-normal direction. Near the wall (

![]() $y_{\textit{ref}}^+=20$

), the contours of

$y_{\textit{ref}}^+=20$

), the contours of

![]() $R_{uu}$

significantly shorten in the streamwise direction as the roughness height increases. This is due to the disturbance of near-wall turbulent streaks by the wall roughness. It is noteworthy that, on the smooth wall,

$R_{uu}$

significantly shorten in the streamwise direction as the roughness height increases. This is due to the disturbance of near-wall turbulent streaks by the wall roughness. It is noteworthy that, on the smooth wall,

![]() $R_{uu}$

maintains relatively high values within

$R_{uu}$

maintains relatively high values within

![]() $y^+\lt 5$

, which can be attributed to the interaction between the large hairpin vortical structures in the outer flow and the small vortices associated with the low-speed streaks very near the wall (Adrian, Meinhart & Tomkins Reference Adrian, Meinhart and Tomkins2000). However, in the rough-wall cases,

$y^+\lt 5$

, which can be attributed to the interaction between the large hairpin vortical structures in the outer flow and the small vortices associated with the low-speed streaks very near the wall (Adrian, Meinhart & Tomkins Reference Adrian, Meinhart and Tomkins2000). However, in the rough-wall cases,

![]() $R_{uu}$

rapidly decreases to zero at the wall due to the destruction of the near-wall streaks by the roughness, which is consistent with the observations of Volino et al. (Reference Volino, Schultz and Flack2007). As

$R_{uu}$

rapidly decreases to zero at the wall due to the destruction of the near-wall streaks by the roughness, which is consistent with the observations of Volino et al. (Reference Volino, Schultz and Flack2007). As

![]() $y_{\textit{ref}}$

increases, the differences in the

$y_{\textit{ref}}$

increases, the differences in the

![]() $R_{uu}$

contours between different cases decrease. In the outer layer (

$R_{uu}$

contours between different cases decrease. In the outer layer (

![]() $y_{\textit{ref}}^+=80$

), the

$y_{\textit{ref}}^+=80$

), the

![]() $R_{uu}$

contours are nearly identical in all cases. This is consistent with previous studies (Volino et al. Reference Volino, Schultz and Flack2007) and supports the outer-layer similarity hypothesis.

$R_{uu}$

contours are nearly identical in all cases. This is consistent with previous studies (Volino et al. Reference Volino, Schultz and Flack2007) and supports the outer-layer similarity hypothesis.

Figure 12. Contours of

![]() $R_{uu}$

centred at (a)

$R_{uu}$

centred at (a)

![]() $y_{\textit{ref}}^+=20$

, (b)

$y_{\textit{ref}}^+=20$

, (b)

![]() $y_{\textit{ref}}^+=40$

and (c)

$y_{\textit{ref}}^+=40$

and (c)

![]() $y_{\textit{ref}}^+=80$

in the non-reacting cases. The values marked in the figure represent the inclination angles of the

$y_{\textit{ref}}^+=80$

in the non-reacting cases. The values marked in the figure represent the inclination angles of the

![]() $R_{uu}$

contours.

$R_{uu}$

contours.

Figure 13. Contours of

![]() $R_{uu}$

centred at (a)

$R_{uu}$

centred at (a)

![]() $y_{\textit{ref}}^+=20$

, (b)

$y_{\textit{ref}}^+=20$

, (b)

![]() $y_{\textit{ref}}^+=40$

and (c)

$y_{\textit{ref}}^+=40$

and (c)

![]() $y_{\textit{ref}}^+=80$

in the reacting cases. The values marked in the figure represent the inclination angles of the

$y_{\textit{ref}}^+=80$

in the reacting cases. The values marked in the figure represent the inclination angles of the

![]() $R_{uu}$

contours.

$R_{uu}$

contours.

In all reacting cases, combustion disrupts the boundary layer turbulence structures. In the region upstream of the flame, the coherent vortical structures of the boundary layer turbulence are lifted upward by the adverse pressure gradient (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023). The angle of inclination of

![]() $R_{uu}$

is related to the inclination angle of the hairpin packets. In the present study, the angle was determined using a least-squares method by fitting a line through the points farthest from the self-correlation peak at each of the five contour levels (0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8 and 0.9) both upstream and downstream of the self-correlation peak (Volino et al. Reference Volino, Schultz and Flack2007). The inclination angle of each

$R_{uu}$

is related to the inclination angle of the hairpin packets. In the present study, the angle was determined using a least-squares method by fitting a line through the points farthest from the self-correlation peak at each of the five contour levels (0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8 and 0.9) both upstream and downstream of the self-correlation peak (Volino et al. Reference Volino, Schultz and Flack2007). The inclination angle of each

![]() $R_{uu}$

contour was calculated and provided in figures 12 and 13. It can be observed that, under the non-reacting condition, wall roughness increases the inclination angle near the wall, while in the outer layer of the boundary layer, the inclination angles remain similar for all cases. Under the reacting condition, combustion leads to an increase in the inclination angle for all cases, with the increase being more pronounced in the rough-wall cases. The change of inclination angle is mainly due to the pressure gradient of the flow field. In a DNS study of non-reacting turbulent boundary layers subjected to adverse pressure gradients, Lee & Sung (Reference Lee and Sung2009) found that the adverse pressure gradient increases the inclination angle of the vortical structures. In the present work, a combustion-induced local high-pressure zone appears in the near-wall reaction region, which creates an adverse pressure gradient upstream of the flame. The combustion-induced adverse pressure gradient is more significant in the rough-wall cases, as shown in figure 14, which results in a larger inclination angle of the two-point correlations.

$R_{uu}$

contour was calculated and provided in figures 12 and 13. It can be observed that, under the non-reacting condition, wall roughness increases the inclination angle near the wall, while in the outer layer of the boundary layer, the inclination angles remain similar for all cases. Under the reacting condition, combustion leads to an increase in the inclination angle for all cases, with the increase being more pronounced in the rough-wall cases. The change of inclination angle is mainly due to the pressure gradient of the flow field. In a DNS study of non-reacting turbulent boundary layers subjected to adverse pressure gradients, Lee & Sung (Reference Lee and Sung2009) found that the adverse pressure gradient increases the inclination angle of the vortical structures. In the present work, a combustion-induced local high-pressure zone appears in the near-wall reaction region, which creates an adverse pressure gradient upstream of the flame. The combustion-induced adverse pressure gradient is more significant in the rough-wall cases, as shown in figure 14, which results in a larger inclination angle of the two-point correlations.

Figure 14. Instantaneous distribution of pressure in the plane of

![]() $y$

= 0.4 mm for various cases at

$y$

= 0.4 mm for various cases at

![]() $t^*$

= 7.6.

$t^*$

= 7.6.

The presence of wall roughness and combustion modifies the near-wall turbulence structures, and impacts the mean skin-friction coefficient

![]() $C_{\kern-2pt f}$

(Spalart & Watmuff Reference Spalart and Watmuff1993; Aubertine & Eaton Reference Aubertine and Eaton2005; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023), which is given as

$C_{\kern-2pt f}$

(Spalart & Watmuff Reference Spalart and Watmuff1993; Aubertine & Eaton Reference Aubertine and Eaton2005; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Gruber, Luo and Fan2023), which is given as

\begin{align} C_{\kern-2pt f} = \frac {\tau _w}{\dfrac {1}{2}\rho _w U_\infty ^2}, \end{align}

\begin{align} C_{\kern-2pt f} = \frac {\tau _w}{\dfrac {1}{2}\rho _w U_\infty ^2}, \end{align}

where

![]() $\tau _w$

is the mean wall stress defined as

$\tau _w$

is the mean wall stress defined as

\begin{align} \tau _w=-\frac {\int _{0}^{\lambda _w}\int _{0}^{\lambda _w} \left ( f_{\!p}+f_{\nu } \right )\mathrm{d}S}{\lambda _w^2}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \tau _w=-\frac {\int _{0}^{\lambda _w}\int _{0}^{\lambda _w} \left ( f_{\!p}+f_{\nu } \right )\mathrm{d}S}{\lambda _w^2}, \end{align}

where

![]() $f_{\!p}=-p (\boldsymbol {n}_{\boldsymbol {w}} )_x$

and

$f_{\!p}=-p (\boldsymbol {n}_{\boldsymbol {w}} )_x$

and

![]() $f_\nu =\mu (\boldsymbol {n}_{\boldsymbol {w}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol {u} )_x$

are the viscous and pressure components of wall friction resistance, respectively. The subscript ‘

$f_\nu =\mu (\boldsymbol {n}_{\boldsymbol {w}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol {u} )_x$

are the viscous and pressure components of wall friction resistance, respectively. The subscript ‘

![]() $x$

’ indicates the vector component in the

$x$