1. Introduction

The controlled steering of microscale and nanoscale objects in fluidic environments by external driving has received significant attention in recent years as an emergent topic of ‘driven matter’ in physics (Witten & Diamant Reference Witten and Diamant2020) and due to their prospective biomedical applications, such as targeted drug delivery and microsurgery (Li et al. Reference Li, de Á vila, Zhang and Wang2017; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Kostarelos, Nelson and Zhang2021; Ruiz-González et al. Reference Ruiz-González, Esporrín-Ubieto, Kim, Wang and Sánchez2025). Among the array of actuation mechanisms, magnetic-field-driven steering of microbots is one of the extensively studied techniques for in vivo applications (Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Mayorga-Martinez, Pané, Zhang and Pumera2021; Oral & Pumera Reference Oral and Pumera2023). The conventional technique employs the magnetic field gradient, which applies a force on magnetic colloids; typically this method requires strong (tesla) fields to generate appreciable gradient over the size of the colloidal particle for its efficient steering. An alternative methodology (Ghosh & Fischer Reference Ghosh and Fischer2009; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Abbott, Dong, Kratochvil, Bell and Nelson2009) employs steering driven by a weak (millitesla) uniform rotating magnetic field. This approach enables efficient steering of shaped magnetic micromotors and relies on viscous rotation–translation coupling. A most obvious choice of the propeller geometry is inspired by the helical bacterial flagellum, which enables bacterial mobility through efficient rotation–translation coupling due to its geometric chirality (Berg Reference Berg2003; Lauga & Powers Reference Lauga and Powers2009). Similarly to bacteria propelled by a rotating flagellum, the magnetic microhelix rotates and propels due to the magnetic torque applied by the rotating magnetic field.

Various fabrication methodologies, including the ‘top-down’ approach (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Abbott, Dong, Kratochvil, Bell and Nelson2009), glancing angle deposition (Ghosh & Fischer Reference Ghosh and Fischer2009), delamination of magnetic stripes (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Makarov, Sanchez, Fomin and Schmidt2011), direct laser writing (Tottori et al. Reference Tottori, Zhang, Qiu, Krawczyk, Franco-Obregón and Nelson2012), template-assisted deposition (Li et al. Reference Li, Sattayasamitsathit, Dong, Gao, Tam, Feng, Ai and Wang2014), biotemplating (Gao et al. Reference Gao, Feng, Pei, Kane, Tam, Hennessy and Wang2014; Yan et al. Reference Yan2015), photopolymerization of magnetic polymer composites (Peters et al. Reference Peters, Ergeneman, Nelson and Hierold2013) and spiralling microfluidic flow lithography (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Shang, Gao, Zhao, Wang and Zhao2017), have been developed for fabricating magnetic microhelices. The obvious bioinspired design of microhelices was later extended to simpler geometrically achiral planar (two-dimensional) micropropellers (Cheang et al. Reference Cheang, Meshkati, Kim, Kim and Fu2014), which can be mass-fabricated using photolithography (Tottori & Nelson Reference Tottori and Nelson2018; Duygu et al. Reference Duygu, Cheang, Leshansky and Kim2024), flexible (one-dimensional) magnetic nanowires that acquire shape requited for rotation–translation coupling dynamically due to the competition of viscous and elastic forces (Gao et al. Reference Gao, Sattayasamitsathit, Manesh, Weihs and Wang2010; Pak et al. Reference Pak, Gao, Wang and Lauga2011), and spontaneously aggregated clusters of magnetic nanoparticles (Vach et al. Reference Vach, Brun, Bennet, Bertinetti, Widdrat, Baumgartner, Klumpp, Fratzl and Faivre2013, Reference Vach, Fratzl, Klumpp and Faivre2015) exhibiting random shape anisotropy.

Most previous theoretical and computational studies focused almost exclusively on driven dynamics of non-Brownian magnetic microbots, including actuation regimes (i.e. synchronous versus asynchronous), the role of geometry (e.g. chiral, achiral or random shaped) and magnetization orientation, types of magnetization (i.e. permanently magnetized versus magnetically polarizable), configuration of the actuating field (i.e. uniform and amplitude-modulated in-plane rotating, conically rotating, etc.), collective dynamics and other topics (see the recent review Pumera et al. (Reference Pumera2025) for details). In particular, the dynamics of a slender ferromagnetic microhelix in a viscous liquid driven by the uniform in-plane rotating magnetic field was first studied by Ghosh et al. (Reference Ghosh, Mandal, Karmakar and Ghosh2013) and Morozov & Leshansky (Reference Morozov and Leshansky2014a ) assuming cylindrical rotational anisotropy. The analogous theory for magnetically polarizable (i.e. superparamagnetic) microhelices (e.g. Peters et al. Reference Peters, Ergeneman, Nelson and Hierold2013) was developed by Morozov & Leshansky (Reference Morozov and Leshansky2014b ). Later Morozov et al. (Reference Morozov, Mirzae, Kenneth and Leshansky2017) developed a general hydrodynamic theory for the torque-driven actuation of arbitrarily shaped and magnetized propeller, establishing the dependence of its dynamic orientation and propulsion on the geometry and magnetization; the theory was recently extended to arbitrary superparamagnetic microbots (Morozov et al. Reference Morozov, Zusmanovich, Rubinstein and Leshansky2025). This general theory confirmed the experimental observations for a propeller made from three interconnected magnetic microbeads (Cheang et al. Reference Cheang, Meshkati, Kim, Kim and Fu2014) and showed that depending on orientation of the magnetic dipolar moment, individual geometrically achiral objects exhibit net propulsion. In particular, it was demonstrated that magnetization of the three-bead propeller in the plane of the beads’ centres resulted in bidirectional propulsion, whereas individual propellers can move in diametrically opposite directions (i.e. parallel and antiparallel to the field rotation axis) with equal speeds. It was also predicted that a specific off-plane magnetization yields unidirectional propulsion of the three-bead propeller, being typically associated with geometrically chiral (e.g. helical) propellers. Notice that the fastest random computer-generated magnetic clusters actually resembled a planar arc, rather than a helix (Mirzae et al. Reference Mirzae, Dubrovski, Kenneth, Morozov and Leshansky2018). Moreover, geometric optimization revealed that the optimal planar propellers are arc-shaped and they fall short (approximately 30 %) of the optimal three-dimensional structures with skew symmetry (Mirzae et al. Reference Mirzae, Dubrovski, Kenneth, Morozov and Leshansky2018). A formal symmetry analysis (involving parity and charge conjugation) was put forward by Sachs et al. (Reference Sachs, Morozov, Kenneth, Qiu, Segreto, Fischer and Leshansky2018) to establish a correspondence between the magnetization orientation and propulsion gaits of torque-driven microbots. In particular, it was predicted that a symmetric two-dimensional propeller magnetized along either of the principal rotation axes exhibits no net propulsion. Individual less symmetric in-plane magnetized microbots exhibit bidirectional propulsion due to a spontaneous symmetry breaking, so that their ensemble average velocity vanishes. Off-plane magnetization can render the symmetric V-shape propeller chiral, whereas the intrinsically broken symmetry results in its unidirectional motion. These theoretical predictions were supported by experiments with a 3D-printed (centimetre-sized) arc-shaped propeller and microscopic V-shaped microbots driven by a rotating magnetic (and electric) field (Sachs et al. Reference Sachs, Morozov, Kenneth, Qiu, Segreto, Fischer and Leshansky2018). In reality, planar magnetic microbots (e.g. fabricated by photolithography) are prone to magnetize in their own plane, leading to bidirectional propulsion, posing a limitation on the controllable steering of their swarms. However, it was predicted theoretically (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Rubinstein, Kenneth and Leshansky2019) and confirmed experimentally (Duygu et al. Reference Duygu, Cheang, Leshansky and Kim2024), that adding a static magnetic field component along the field rotation axis reduces the symmetry of the problem, resulting in unidirectional propulsion of highly symmetrical planar and in-plane magnetized microbots. Similarly, adding a static field component perpendicular to the field rotation axis, results in propulsion accompanied by a net drift in plane of the field (Morozov & Leshansky Reference Morozov and Leshansky2020).

Although the above theories concern actuation and propulsion of non-Brownian microbots, current microfabrication techniques (such as ‘glancing angle deposition’) can be readily used to fabricate magnetic nanobots capable of steering through submicrometre interstitial spaces of crowded biomimetic (Schamel et al. Reference Schamel, Mark, Gibbs, Miksch, Morozov, Leshansky and Fischer2014) or biological (Dasgupta et al. Reference Dasgupta, Pally, Saini, Bhat and Ghosh2020) environments and even navigate within living biological cells (Pal et al. Reference Pal, Somalwar, Singh, Bhat, Eswarappa, Saini and Ghosh2018). At submicron scale, thermal noise becomes increasingly significant, and may become comparable in magnitude to the magnetic driving, thereby hindering the actuation and impairing propulsion. This raises an important question: How small a nanopropeller can be? Despite growing experimental interest in achieving controllable propulsion at nanoscale and a few previous ad hoc efforts to address this question qualitatively (Schamel et al. Reference Schamel, Mark, Gibbs, Miksch, Morozov, Leshansky and Fischer2014; Ghosh et al. Reference Ghosh, Paria, Rangarajan and Ghosh2014), a rigorous quantitative investigation of the role of thermal fluctuations on magnetically driven actuation and propulsion of magnetic nanobots was still lacking. It is also worth mentioning that this question is showing on top of the list of 10 most critical problems for the advancement of micro/nanorobots in the next decade, ‘serving as a foundation for a technology roadmap’ (Pumera et al. Reference Pumera2025).

The present paper aims to study the impact of thermal noise on torque-driven actuation and propulsion of magnetic nanohelices in a viscous fluid using numerical simulations of the Langevin equation and Fokker–Planck theory. At the nanoscale the general theoretical formalism of ‘fluctuating hydrodynamics’ reduces to a classical Langevin equation, provided that the Brownian particle is much larger compared with the fluid particle (Hauge & Martin-Löf Reference Hauge and Martin-Löf1973), and implying that the dynamics of the magnetic Brownian nanobot is governed by Stokes hydrodynamics, whereby the viscous and thermal forces and torques are counterbalanced by external forcing. The relative importance of the magnetic driving with respect to thermal noise is measured by the rotational Péclet number,

![]() $ \textit{Pe} = \textit{mH}/(k_{B} T)$

(otherwise known as Langevin parameter,

$ \textit{Pe} = \textit{mH}/(k_{B} T)$

(otherwise known as Langevin parameter,

![]() $\xi$

), where

$\xi$

), where

![]() $k_{B}$

is the Boltzmann constant,

$k_{B}$

is the Boltzmann constant,

![]() $T$

is the temperature,

$T$

is the temperature,

![]() $H$

stands for the magnitude of the rotating field and

$H$

stands for the magnitude of the rotating field and

![]() $m$

for the magnetic moment of the propeller. Qualitatively speaking, the thermal noise affects the dynamics of the torque-driven nanobot in three distinct ways: (i) by impeding its forced rotations, thereby reducing its angular velocity; (ii) perturbing its steady orientation with respect to the actuating field; (iii) obstructing its linear motion (i.e. propulsion) (Schamel et al. Reference Schamel, Mark, Gibbs, Miksch, Morozov, Leshansky and Fischer2014). The first two mechanisms rely on rotational diffusion about the propellers’ long and short axes, whereas the third mechanism stems from translational diffusion.

$m$

for the magnetic moment of the propeller. Qualitatively speaking, the thermal noise affects the dynamics of the torque-driven nanobot in three distinct ways: (i) by impeding its forced rotations, thereby reducing its angular velocity; (ii) perturbing its steady orientation with respect to the actuating field; (iii) obstructing its linear motion (i.e. propulsion) (Schamel et al. Reference Schamel, Mark, Gibbs, Miksch, Morozov, Leshansky and Fischer2014). The first two mechanisms rely on rotational diffusion about the propellers’ long and short axes, whereas the third mechanism stems from translational diffusion.

We have organized the paper as follows. In § 2 we formulate the Langevin dynamics of an arbitrarily shaped and magnetized propeller in presence of thermal fluctuations. The alternative formalism based on Fokker–Planck equation is derived in § 3. In § 4.1, we present the results of the reduced model, whereas we assume that thermal fluctuations contribute solely to the random torque, while the effect of the stochastic force is entirely neglected. This reduced model accounts for the mechanisms (i) and (ii) above which affect the angular dynamics and dynamic orientation of the nanobot with respect to the actuating field. The results of the Langevin simulations reported in § 4.1 are first presented under the simplifying assumption of cylindrical rotational anisotropy and then for an arbitrary geometry of the nanobot; the results in the former case are compared with corresponding solution of the Fokker–Planck equation. In § 4.2 we study the effect of the thermal noise on the actuation and propulsion of the torque-driven helical magnetic nanobots. In § 4.3, we consider the full model, introducing the random thermal force, and investigate its effect on the steerability of the helical nanobots. Finally, we summarize our results and draw conclusions in § 5.

2. Langevin formalism

For externally driven matter, the particle’s motion is generated by either the external force

![]() $\boldsymbol F$

or torque

$\boldsymbol F$

or torque

![]() $\boldsymbol L$

. In the Stokes approximation of incompressible Newtonian fluid, translation and rotational velocities

$\boldsymbol L$

. In the Stokes approximation of incompressible Newtonian fluid, translation and rotational velocities

![]() $\boldsymbol U$

and

$\boldsymbol U$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol \varOmega$

of the propeller are obtained from the force and torque balance, given by (Kim & Karrila Reference Kim and Karrila1991)

$\boldsymbol \varOmega$

of the propeller are obtained from the force and torque balance, given by (Kim & Karrila Reference Kim and Karrila1991)

Here,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{E}}$

and

$\boldsymbol{\mathcal{E}}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}$

are the symmetric translation and rotation mobility tensors, respectively. Here

$\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}$

are the symmetric translation and rotation mobility tensors, respectively. Here

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{G}}$

is the coupling mobility tensor. Note that the translation and rotation mobility tensors are symmetric in any coordinate frame, whereas the coupling tensor

$\boldsymbol{\mathcal{G}}$

is the coupling mobility tensor. Note that the translation and rotation mobility tensors are symmetric in any coordinate frame, whereas the coupling tensor

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{G}}$

is not symmetric in general (Kim & Karrila Reference Kim and Karrila1991). However,

$\boldsymbol{\mathcal{G}}$

is not symmetric in general (Kim & Karrila Reference Kim and Karrila1991). However,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{G}}$

can always be symmetrized by choosing the centre of hydrodynamic mobility as the origin of the reference frame (Morozov et al. Reference Morozov, Mirzae, Kenneth and Leshansky2017). In this work, we study the dynamics of the magnetized nanohelices actuated by a uniform in-plane rotating magnetic field (see figure 1

a). Two different coordinate systems are employed throughout the paper, the laboratory frame

$\boldsymbol{\mathcal{G}}$

can always be symmetrized by choosing the centre of hydrodynamic mobility as the origin of the reference frame (Morozov et al. Reference Morozov, Mirzae, Kenneth and Leshansky2017). In this work, we study the dynamics of the magnetized nanohelices actuated by a uniform in-plane rotating magnetic field (see figure 1

a). Two different coordinate systems are employed throughout the paper, the laboratory frame

![]() $[\hat {\boldsymbol x}\hat {\boldsymbol y}\hat {\boldsymbol z}]$

fixed in space and the body frame

$[\hat {\boldsymbol x}\hat {\boldsymbol y}\hat {\boldsymbol z}]$

fixed in space and the body frame

![]() $[\hat {\boldsymbol e}_1\hat {\boldsymbol e}_2\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3]$

, affixed with the propeller (see figure 1

b,c). We assume the uniform magnetic field rotates in the

$[\hat {\boldsymbol e}_1\hat {\boldsymbol e}_2\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3]$

, affixed with the propeller (see figure 1

b,c). We assume the uniform magnetic field rotates in the

![]() $xy$

-plane in the laboratory frame,

$xy$

-plane in the laboratory frame,

where

![]() $H$

and

$H$

and

![]() $\omega$

are the magnetic field’s amplitude and angular frequency, respectively. The permanent magnetic moment is

$\omega$

are the magnetic field’s amplitude and angular frequency, respectively. The permanent magnetic moment is

![]() $\boldsymbol m$

affixed with the propeller and given by

$\boldsymbol m$

affixed with the propeller and given by

where

![]() $m=|\boldsymbol m|$

, and

$m=|\boldsymbol m|$

, and

![]() $\varPhi$

and

$\varPhi$

and

![]() $\alpha$

are the spherical polar and azimuthal magnetization angles in the body frame, respectively (see figure 1

b,c).

$\alpha$

are the spherical polar and azimuthal magnetization angles in the body frame, respectively (see figure 1

b,c).

Figure 1. (a) Schematic drawing of the magnetic nanohelix with a magnetic moment

![]() $\boldsymbol m$

in laboratory-frame

$\boldsymbol m$

in laboratory-frame

![]() $[\hat {\boldsymbol x}\hat {\boldsymbol y}\hat {\boldsymbol z}]$

actuated by a uniform magnetic field

$[\hat {\boldsymbol x}\hat {\boldsymbol y}\hat {\boldsymbol z}]$

actuated by a uniform magnetic field

![]() $\boldsymbol H$

rotating in the

$\boldsymbol H$

rotating in the

![]() $xy$

-plane with angular frequency

$xy$

-plane with angular frequency

![]() $\omega$

. The propeller turns with angular velocity

$\omega$

. The propeller turns with angular velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{{\varOmega }}$

with precession angle

$\boldsymbol{{\varOmega }}$

with precession angle

![]() $\theta$

and propels with linear velocity

$\theta$

and propels with linear velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol U$

. (b) Schematic drawing of a one-turn helical propeller with the principal rotation axes

$\boldsymbol U$

. (b) Schematic drawing of a one-turn helical propeller with the principal rotation axes

![]() $[\hat {\boldsymbol e}_1\hat {\boldsymbol e}_2\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3]$

with origin at the mobility centre;

$[\hat {\boldsymbol e}_1\hat {\boldsymbol e}_2\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3]$

with origin at the mobility centre;

![]() $\varPhi = \pi /4$

and

$\varPhi = \pi /4$

and

![]() $\alpha = \pi /4$

are, respectively, spherical polar and azimuthal magnetization angles describing the orientation of the magnetic moment

$\alpha = \pi /4$

are, respectively, spherical polar and azimuthal magnetization angles describing the orientation of the magnetic moment

![]() $\boldsymbol m$

. (c) The same as in (b) for a two-turn helical propeller with

$\boldsymbol m$

. (c) The same as in (b) for a two-turn helical propeller with

![]() $\varPhi =\pi /4$

and

$\varPhi =\pi /4$

and

![]() $\alpha =\pi$

.

$\alpha =\pi$

.

Under the uniform external field the propeller is subjected to a magnetic torque

![]() $\boldsymbol L_m = {\boldsymbol m}\times {\boldsymbol H}$

. Due to its small size, the nanopropeller is also subjected to thermal fluctuations from the solvent molecules, imposing force and torque on the propeller. However, unlike magnetic torque, these forces are stochastic, resulting in Brownian (diffusive) transport of the nanobot. The Brownian force,

$\boldsymbol L_m = {\boldsymbol m}\times {\boldsymbol H}$

. Due to its small size, the nanopropeller is also subjected to thermal fluctuations from the solvent molecules, imposing force and torque on the propeller. However, unlike magnetic torque, these forces are stochastic, resulting in Brownian (diffusive) transport of the nanobot. The Brownian force,

![]() $\boldsymbol F_{\kern-1pt B}$

, and torque,

$\boldsymbol F_{\kern-1pt B}$

, and torque,

![]() $\boldsymbol L_B$

, are given in the body reference frame by, respectively,

$\boldsymbol L_B$

, are given in the body reference frame by, respectively,

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{X}_{F}$

and

$\boldsymbol{X}_{F}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{X}_{L}$

are the uncorrelated random processes of zero mean and unit variance, both satisfying

$\boldsymbol{X}_{L}$

are the uncorrelated random processes of zero mean and unit variance, both satisfying

where

![]() $\delta _{\textit{ij}}$

the Kronecker delta,

$\delta _{\textit{ij}}$

the Kronecker delta,

![]() $\delta (t)$

is the Dirac delta and the ‘square root’ of the inverse mobilities is defined via

$\delta (t)$

is the Dirac delta and the ‘square root’ of the inverse mobilities is defined via

![]() ${\boldsymbol{\mathcal{E}}}^{-1/2}\boldsymbol{\cdot }( {\boldsymbol{\mathcal{E}}}^{-1/2} )^T={\boldsymbol{\mathcal{E}}}^{-1}$

(Delong, Balboa Usabiaga & Donev Reference Delong, Balboa Usabiaga and Donev2015).

${\boldsymbol{\mathcal{E}}}^{-1/2}\boldsymbol{\cdot }( {\boldsymbol{\mathcal{E}}}^{-1/2} )^T={\boldsymbol{\mathcal{E}}}^{-1}$

(Delong, Balboa Usabiaga & Donev Reference Delong, Balboa Usabiaga and Donev2015).

Since the zero-mean Brownian force

![]() $\boldsymbol F_{\kern-1pt B}$

is not expected to affect the torque-driven dynamics of the nanobot on average, we shall first assume

$\boldsymbol F_{\kern-1pt B}$

is not expected to affect the torque-driven dynamics of the nanobot on average, we shall first assume

![]() ${\boldsymbol F}_B=0$

and only consider the effect of the random torque,

${\boldsymbol F}_B=0$

and only consider the effect of the random torque,

![]() $\boldsymbol L_B$

on actuation and propulsion. The combined action of the random thermal force and torque will be studied later in § 4.3. Therefore, assuming that the uniform magnetic field applies no magnetic force, the propeller is force-free and driven by the combined action of magnetic and Brownian torques,

$\boldsymbol L_B$

on actuation and propulsion. The combined action of the random thermal force and torque will be studied later in § 4.3. Therefore, assuming that the uniform magnetic field applies no magnetic force, the propeller is force-free and driven by the combined action of magnetic and Brownian torques,

The translation and the rotational velocities can be readily obtained from (2.1) as

We now choose the principal axes of rotation as the body-frame axes, with the basis unit vectors

![]() $[\hat {\boldsymbol e}_1\hat {\boldsymbol e}_2\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3]$

being the eigenvectors of rotational mobility tensor

$[\hat {\boldsymbol e}_1\hat {\boldsymbol e}_2\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3]$

being the eigenvectors of rotational mobility tensor

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}$

. In this body-frame,

$\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}$

. In this body-frame,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}$

assumes a diagonal form, and the angular dynamics of an arbitrary-shaped object is isomorphic to that of a triaxial ellipsoidal particle. Following Morozov et al. (Reference Morozov, Mirzae, Kenneth and Leshansky2017) we fix the eigenvalues in the ascending order,

$\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}$

assumes a diagonal form, and the angular dynamics of an arbitrary-shaped object is isomorphic to that of a triaxial ellipsoidal particle. Following Morozov et al. (Reference Morozov, Mirzae, Kenneth and Leshansky2017) we fix the eigenvalues in the ascending order,

![]() $\mbox{${\mathcal F}_1$} \le \mbox{${\mathcal F}_2$} \le \mbox{${\mathcal F}_3$}$

, such that the rotation-easy axis coincides with the eigenvector

$\mbox{${\mathcal F}_1$} \le \mbox{${\mathcal F}_2$} \le \mbox{${\mathcal F}_3$}$

, such that the rotation-easy axis coincides with the eigenvector

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol e}_{\small {{3}}}$

corresponding to the largest eigenvalue

$\hat {\boldsymbol e}_{\small {{3}}}$

corresponding to the largest eigenvalue

![]() $\mbox{${\mathcal F}_3$}$

and so on.

$\mbox{${\mathcal F}_3$}$

and so on.

We characterize the orientation of propeller in laboratory frame by the rotation matrix

![]() $\boldsymbol R$

parameterized by the four-dimensional quaternion vector

$\boldsymbol R$

parameterized by the four-dimensional quaternion vector

![]() $\boldsymbol q= \{ q_0, q_1, q_2, q_3\}$

of unit lenth,

$\boldsymbol q= \{ q_0, q_1, q_2, q_3\}$

of unit lenth,

![]() $|\boldsymbol q|=1$

. The magnetic torque in the body reference frame is then given by

$|\boldsymbol q|=1$

. The magnetic torque in the body reference frame is then given by

![]() $\boldsymbol L_m = \boldsymbol m\times {\boldsymbol H}^{{\small {{b}}}} = {\boldsymbol m}\times ({\boldsymbol R\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol H})$

, where the superscript ‘b’ stands for the body-frame of reference and the rotation matrix

$\boldsymbol L_m = \boldsymbol m\times {\boldsymbol H}^{{\small {{b}}}} = {\boldsymbol m}\times ({\boldsymbol R\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol H})$

, where the superscript ‘b’ stands for the body-frame of reference and the rotation matrix

![]() $\boldsymbol R$

is defined as (Rapaport Reference Rapaport1985)

$\boldsymbol R$

is defined as (Rapaport Reference Rapaport1985)

\begin{align} {\boldsymbol R} = \begin{pmatrix} q_0^2 +q_1^2-q_2^2-q_3^2 & 2(q_1q_2+q_0q_3) & 2(q_1q_3-q_0q_2) \\ 2(q_1q_2-q_0q_3) & q_0^2+q_2^2-q_1^2-q_3^2 & 2(q_2q_3+q_0q_1) \\ 2(q_1q_3+q_0q_2) & 2(q_2q_3-q_0q_1) & q_0^2+q_3^2-q_1^2-q_2^2 \end{pmatrix}\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} {\boldsymbol R} = \begin{pmatrix} q_0^2 +q_1^2-q_2^2-q_3^2 & 2(q_1q_2+q_0q_3) & 2(q_1q_3-q_0q_2) \\ 2(q_1q_2-q_0q_3) & q_0^2+q_2^2-q_1^2-q_3^2 & 2(q_2q_3+q_0q_1) \\ 2(q_1q_3+q_0q_2) & 2(q_2q_3-q_0q_1) & q_0^2+q_3^2-q_1^2-q_2^2 \end{pmatrix}\!. \end{align}

Combining (2.6) and (2.7) we obtain the expression for the angular velocity as

where

![]() $\boldsymbol h = {\boldsymbol H}/H = \hat {\boldsymbol x}\cos {\omega t}+ \hat {\boldsymbol y}\sin {\omega t}$

. Now, we obtain the equation of motion in quaternion formulation as

$\boldsymbol h = {\boldsymbol H}/H = \hat {\boldsymbol x}\cos {\omega t}+ \hat {\boldsymbol y}\sin {\omega t}$

. Now, we obtain the equation of motion in quaternion formulation as

where

![]() $\boldsymbol M$

is a

$\boldsymbol M$

is a

![]() $4\times 3$

matrix defined as (Ilie, Briels & den Otter Reference Ilie, Briels and den Otter2015; Delong et al. Reference Delong, Balboa Usabiaga and Donev2015)

$4\times 3$

matrix defined as (Ilie, Briels & den Otter Reference Ilie, Briels and den Otter2015; Delong et al. Reference Delong, Balboa Usabiaga and Donev2015)

\begin{align} {{\boldsymbol M}(\boldsymbol q)} = \frac {1}{2}\begin{pmatrix} -q_1 & -q_2 & -q_3 \\ q_0 & -q_3 & q_2 \\ q_3 & q_0 & -q_1 \\ -q_2 & q_1 & q_0 \\ \end{pmatrix}\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} {{\boldsymbol M}(\boldsymbol q)} = \frac {1}{2}\begin{pmatrix} -q_1 & -q_2 & -q_3 \\ q_0 & -q_3 & q_2 \\ q_3 & q_0 & -q_1 \\ -q_2 & q_1 & q_0 \\ \end{pmatrix}\!. \end{align}

We now introduce the dimensionless variables, such as time

![]() $\tilde {t} = \omega t$

and frequency

$\tilde {t} = \omega t$

and frequency

![]() $\widetilde {\omega } = \omega /\omega _0$

, where

$\widetilde {\omega } = \omega /\omega _0$

, where

![]() $\omega _0 = \textit{mH}{\mathcal F}_{\small {\perp }}$

, with

$\omega _0 = \textit{mH}{\mathcal F}_{\small {\perp }}$

, with

![]() ${\mathcal F}_{\small {\perp }}$

being the harmonic mean of the minor (transverse) rotational mobilities,

${\mathcal F}_{\small {\perp }}$

being the harmonic mean of the minor (transverse) rotational mobilities,

![]() ${\mathcal F}_{\small {\perp }}^{-1} = (\mbox{${\mathcal F}_1$}^{-1}+\mbox{${\mathcal F}_2$}^{-1})/2$

; the rotational anisotropy of the propeller is characterized by the longitudinal and transverse anisotropy parameters, respectively,

${\mathcal F}_{\small {\perp }}^{-1} = (\mbox{${\mathcal F}_1$}^{-1}+\mbox{${\mathcal F}_2$}^{-1})/2$

; the rotational anisotropy of the propeller is characterized by the longitudinal and transverse anisotropy parameters, respectively,

![]() $p = \mbox{${\mathcal F}_3$}/{\mathcal F}_{\small {\perp }}$

and

$p = \mbox{${\mathcal F}_3$}/{\mathcal F}_{\small {\perp }}$

and

![]() $\varepsilon = (\mbox{${\mathcal F}_2$}-\mbox{${\mathcal F}_1$})/(\mbox{${\mathcal F}_2$}+\mbox{${\mathcal F}_1$})$

. Thus, we rewrite the scaled angular velocity of the propeller as a sum of magnetic and Brownian contributions,

$\varepsilon = (\mbox{${\mathcal F}_2$}-\mbox{${\mathcal F}_1$})/(\mbox{${\mathcal F}_2$}+\mbox{${\mathcal F}_1$})$

. Thus, we rewrite the scaled angular velocity of the propeller as a sum of magnetic and Brownian contributions,

where

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}_m=\begin{pmatrix} \dfrac {1}{\widetilde {\omega }(1+\varepsilon )} ({\boldsymbol n} \times ({\boldsymbol R}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol h) )_{\small {{1}}} \\[11pt] \dfrac {1}{\widetilde {\omega }(1-\varepsilon )} ({\boldsymbol n} \times ({\boldsymbol R}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol h))_{\small {{2}}} \\[11pt] \dfrac {p}{\widetilde {\omega }}({\boldsymbol n} \times ({\boldsymbol R}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol h))_{\small {{3}}} \end{pmatrix}\!,\,\,\,\,\,\, \boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}_B = \begin{pmatrix} \sqrt {\dfrac {2}{\widetilde {\omega }\,\textit{Pe}\,(1+\varepsilon )}}\,X_{\small {{1}}}\\[11pt] \sqrt {\dfrac {2}{\widetilde {\omega }\,\textit{Pe}\,(1-\varepsilon )}}\,X_{\small {{2}}}\\[11pt] \sqrt {\dfrac {2\,p}{\widetilde {\omega }\,\textit{Pe}}}\,X_{\small {{3}}} \end{pmatrix}\!, \end{align}

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}_m=\begin{pmatrix} \dfrac {1}{\widetilde {\omega }(1+\varepsilon )} ({\boldsymbol n} \times ({\boldsymbol R}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol h) )_{\small {{1}}} \\[11pt] \dfrac {1}{\widetilde {\omega }(1-\varepsilon )} ({\boldsymbol n} \times ({\boldsymbol R}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol h))_{\small {{2}}} \\[11pt] \dfrac {p}{\widetilde {\omega }}({\boldsymbol n} \times ({\boldsymbol R}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol h))_{\small {{3}}} \end{pmatrix}\!,\,\,\,\,\,\, \boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}_B = \begin{pmatrix} \sqrt {\dfrac {2}{\widetilde {\omega }\,\textit{Pe}\,(1+\varepsilon )}}\,X_{\small {{1}}}\\[11pt] \sqrt {\dfrac {2}{\widetilde {\omega }\,\textit{Pe}\,(1-\varepsilon )}}\,X_{\small {{2}}}\\[11pt] \sqrt {\dfrac {2\,p}{\widetilde {\omega }\,\textit{Pe}}}\,X_{\small {{3}}} \end{pmatrix}\!, \end{align}

and

![]() $\boldsymbol X_L = (X_{\small {{1}}}, X_{\small {{2}}}, X_{\small {{3}}})$

is the random processes of zero mean and unit variance. The rotational Péclet number,

$\boldsymbol X_L = (X_{\small {{1}}}, X_{\small {{2}}}, X_{\small {{3}}})$

is the random processes of zero mean and unit variance. The rotational Péclet number,

![]() $ \textit{Pe} = \textit{mH}/(k_{B}T)$

(also known as Langevin parameter,

$ \textit{Pe} = \textit{mH}/(k_{B}T)$

(also known as Langevin parameter,

![]() $\xi$

) determines the relative strength of the magnetic driving and thermal noise and compares the rotation velocity of the nanobot driven by the magnetic torque,

$\xi$

) determines the relative strength of the magnetic driving and thermal noise and compares the rotation velocity of the nanobot driven by the magnetic torque,

![]() ${\varOmega }_m$

, with the rotational diffusion coefficient of the nanobot,

${\varOmega }_m$

, with the rotational diffusion coefficient of the nanobot,

![]() $D_{r}$

. Since

$D_{r}$

. Since

![]() $\boldsymbol{{\varOmega }}_m={\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }[{\boldsymbol m}\times {\boldsymbol H}]$

and the rotational diffusivity tensor

$\boldsymbol{{\varOmega }}_m={\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }[{\boldsymbol m}\times {\boldsymbol H}]$

and the rotational diffusivity tensor

![]() $\boldsymbol{D}_r={\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}} k_{B}T$

, we readily obtain that

$\boldsymbol{D}_r={\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}} k_{B}T$

, we readily obtain that

![]() ${\varOmega }_m/D_r\!\propto \! \textit{mH}/(k_{B}T)$

.

${\varOmega }_m/D_r\!\propto \! \textit{mH}/(k_{B}T)$

.

Substituting the expression of angular velocity in (2.10), we obtain the equations of motion in quaternion formulation,

under the constraint

![]() $|\boldsymbol q| = 1$

. We solve these equations using the explicit Euler scheme, whereas at the first step the propagator for quaternion at time

$|\boldsymbol q| = 1$

. We solve these equations using the explicit Euler scheme, whereas at the first step the propagator for quaternion at time

![]() ${\tilde t}+\delta {\tilde t}$

is computed as

${\tilde t}+\delta {\tilde t}$

is computed as

where

![]() $\widehat {\varOmega }^{(m)}_{j}$

and

$\widehat {\varOmega }^{(m)}_{j}$

and

![]() $\widehat {{\varOmega }}^{(B)}_{j}$

are the respective components of

$\widehat {{\varOmega }}^{(B)}_{j}$

are the respective components of

![]() $\boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}_m$

and

$\boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}_m$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}_B$

, and repeated indices imply summation. Then we add to

$\boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}_B$

, and repeated indices imply summation. Then we add to

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol q}({\tilde t}+\delta \tilde {t})$

the term

$\hat {\boldsymbol q}({\tilde t}+\delta \tilde {t})$

the term

![]() $\lambda _{\small {q}} {\boldsymbol q}({\tilde t})$

, where the Lagrange multiplier

$\lambda _{\small {q}} {\boldsymbol q}({\tilde t})$

, where the Lagrange multiplier

![]() $\lambda _{\small {q}}$

is calculated by imposing the condition

$\lambda _{\small {q}}$

is calculated by imposing the condition

![]() $|{\boldsymbol q}({\tilde t}+\delta {\tilde t})| = 1$

. This leads to a quadratic equation for

$|{\boldsymbol q}({\tilde t}+\delta {\tilde t})| = 1$

. This leads to a quadratic equation for

![]() $\lambda _{\small {q}}$

:

$\lambda _{\small {q}}$

:

Taking the larger root of (2.16) we complete the propagation step:

We generate the

![]() $10^4$

random ensembles of initial conditions (orientations) of the quaternion vector, uniformly distributed on the surface of a four-dimensional unit sphere,

$10^4$

random ensembles of initial conditions (orientations) of the quaternion vector, uniformly distributed on the surface of a four-dimensional unit sphere,

![]() $|\boldsymbol q| = 1$

. For each ensemble, we ignore the transient evolution for each initial orientation (typically tens of dimensionless time units) and collect data at

$|\boldsymbol q| = 1$

. For each ensemble, we ignore the transient evolution for each initial orientation (typically tens of dimensionless time units) and collect data at

![]() ${\tilde t}\!\gt \!100$

. The mean values of the dynamic variables were determined upon time-averaging over the ensembles of random initial orientations.

${\tilde t}\!\gt \!100$

. The mean values of the dynamic variables were determined upon time-averaging over the ensembles of random initial orientations.

Since the solution for the angular dynamics of non-Brownian propellers (i.e.

![]() $ \textit{Pe}=\infty$

) was previously obtained (Morozov & Leshansky Reference Morozov and Leshansky2014a

; Morozov et al. Reference Morozov, Mirzae, Kenneth and Leshansky2017) using the Euler angles

$ \textit{Pe}=\infty$

) was previously obtained (Morozov & Leshansky Reference Morozov and Leshansky2014a

; Morozov et al. Reference Morozov, Mirzae, Kenneth and Leshansky2017) using the Euler angles

![]() $\varphi$

,

$\varphi$

,

![]() $\theta$

and

$\theta$

and

![]() $\psi$

(via standard ‘ZXZ’ parametrization), we rewrite the quaternions as

$\psi$

(via standard ‘ZXZ’ parametrization), we rewrite the quaternions as

\begin{align} q_{{\small {{0}}}} = \cos \frac {\theta }{2}\cos \left (\frac {\varphi +\psi }{2}\right )\!, \,\,\,\,\,\,\, q_{\small {{1}}} = \sin \frac {\theta }{2}\cos \left (\frac {\varphi -\psi }{2}\right )\!, \nonumber \\ q_{\small {{2}}} = \sin \frac {\theta }{2}\sin \left (\frac {\varphi -\psi }{2}\right )\!, \,\,\,\,\,\,\, q_{\small {{3}}} = \cos \frac {\theta }{2}\sin \left (\frac {\varphi +\psi }{2}\right )\!. \\[8pt] \nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} q_{{\small {{0}}}} = \cos \frac {\theta }{2}\cos \left (\frac {\varphi +\psi }{2}\right )\!, \,\,\,\,\,\,\, q_{\small {{1}}} = \sin \frac {\theta }{2}\cos \left (\frac {\varphi -\psi }{2}\right )\!, \nonumber \\ q_{\small {{2}}} = \sin \frac {\theta }{2}\sin \left (\frac {\varphi -\psi }{2}\right )\!, \,\,\,\,\,\,\, q_{\small {{3}}} = \cos \frac {\theta }{2}\sin \left (\frac {\varphi +\psi }{2}\right )\!. \\[8pt] \nonumber \end{align}

For example, the precession (wobbling) angle

![]() $\theta$

, defined as angle between the field’s rotation axis and the rotation-easy axis of the propeller as shown in figure 1(a), is obtained as

$\theta$

, defined as angle between the field’s rotation axis and the rotation-easy axis of the propeller as shown in figure 1(a), is obtained as

![]() $\cos {\theta } = q^2_{{\small {{0}}}}+q^2_{\small {{3}}}-q^2_{\small {{1}}}-q^2_{\small {{2}}}$

.

$\cos {\theta } = q^2_{{\small {{0}}}}+q^2_{\small {{3}}}-q^2_{\small {{1}}}-q^2_{\small {{2}}}$

.

To validate the numerical approach, we first solve the equations of motion (2.10) in the non-Brownian limit, i.e. with

![]() $\boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}_B=\boldsymbol{0}$

in (2.12). The comparison with the previous analytical and numerical results for the angular dynamics in the limit of infinite Pe shows an excellent agreement. When the thermal noise was included, the initial orientation of the thermally averaged quaternion vector

$\boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}_B=\boldsymbol{0}$

in (2.12). The comparison with the previous analytical and numerical results for the angular dynamics in the limit of infinite Pe shows an excellent agreement. When the thermal noise was included, the initial orientation of the thermally averaged quaternion vector

![]() $\langle \boldsymbol q\rangle$

showed exponential decay with time (over

$\langle \boldsymbol q\rangle$

showed exponential decay with time (over

![]() $\sim \!100$

time units) as anticipated, as the memory of the initial orientation is lost due to thermal diffusion.

$\sim \!100$

time units) as anticipated, as the memory of the initial orientation is lost due to thermal diffusion.

Employing the solution for the angular velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{{\varOmega }}^{{\small {{b}}}}$

in (2.12), the linear (or propulsion) velocity can be readily found in the body frame (in which the viscous mobility tensors are constant) from (2.7) as

$\boldsymbol{{\varOmega }}^{{\small {{b}}}}$

in (2.12), the linear (or propulsion) velocity can be readily found in the body frame (in which the viscous mobility tensors are constant) from (2.7) as

Finally, the propulsion velocity in the laboratory frame reads

where

![]() $\boldsymbol R$

is given in (2.8). Equation (2.20) can be readily rewritten in the dimensionless form as

$\boldsymbol R$

is given in (2.8). Equation (2.20) can be readily rewritten in the dimensionless form as

where

![]() ${\boldsymbol{Ch}} = \boldsymbol{\mathcal{G}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }(\ell {\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}})^{-1}$

, is the dimensionless chirality matrix with

${\boldsymbol{Ch}} = \boldsymbol{\mathcal{G}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }(\ell {\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}})^{-1}$

, is the dimensionless chirality matrix with

![]() $\ell$

being the characteristic size of the propeller. (Notice that a difference in the definition of

$\ell$

being the characteristic size of the propeller. (Notice that a difference in the definition of

![]() ${\boldsymbol{Ch}}$

here and in Morozov et al. (Reference Morozov, Mirzae, Kenneth and Leshansky2017) and Mirzae et al. (Reference Mirzae, Dubrovski, Kenneth, Morozov and Leshansky2018), where it was defined as the symmetric part of

${\boldsymbol{Ch}}$

here and in Morozov et al. (Reference Morozov, Mirzae, Kenneth and Leshansky2017) and Mirzae et al. (Reference Mirzae, Dubrovski, Kenneth, Morozov and Leshansky2018), where it was defined as the symmetric part of

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{G}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }({\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}} \ell )^{-1}$

in the equation for the propulsion velocity of non-Brownian magnetic propeller rotating in-sync with the field,

$\boldsymbol{\mathcal{G}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }({\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}} \ell )^{-1}$

in the equation for the propulsion velocity of non-Brownian magnetic propeller rotating in-sync with the field,

![]() $U_z/\omega \ell =\boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }{\boldsymbol{Ch}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}$

, where

$U_z/\omega \ell =\boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }{\boldsymbol{Ch}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}$

, where

![]() $\boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}=\omega \hat {\boldsymbol z}$

.)

$\boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}=\omega \hat {\boldsymbol z}$

.)

3. Fokker–Planck formalism

Alternatively to the Langevin formalism of § 2, one can also apply the Fokker–Planck formalism. Denote

![]() $W(\varphi , \theta , \psi , t)$

the distribution function of the particle orientation characterized by the Euler angles. The dynamic Fokker–Planck equation governing the orientations of an arbitrary shaped particle can be found as generalization of the uniaxial problem by Mazo (Reference Mazo2002),

$W(\varphi , \theta , \psi , t)$

the distribution function of the particle orientation characterized by the Euler angles. The dynamic Fokker–Planck equation governing the orientations of an arbitrary shaped particle can be found as generalization of the uniaxial problem by Mazo (Reference Mazo2002),

\begin{align} \frac {\partial W}{\partial t}=\sum _{j=1}^3 \left [D_j \frac {\partial ^2 W}{\partial \eta _j^2}-\frac {D_j}{k_{B}T}\frac {\partial }{\partial \eta _j}(L_j^{(m)}W)\right ]\!, \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial W}{\partial t}=\sum _{j=1}^3 \left [D_j \frac {\partial ^2 W}{\partial \eta _j^2}-\frac {D_j}{k_{B}T}\frac {\partial }{\partial \eta _j}(L_j^{(m)}W)\right ]\!, \end{align}

where

![]() $D_j = {\mathcal F}_jk_{B}T$

are the eigenvalues of the rotational diffusivity tensor

$D_j = {\mathcal F}_jk_{B}T$

are the eigenvalues of the rotational diffusivity tensor

![]() $\boldsymbol{D}_r$

corresponding to rotations about

$\boldsymbol{D}_r$

corresponding to rotations about

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol e}_{\kern-1pt j}$

axes,

$\hat {\boldsymbol e}_{\kern-1pt j}$

axes,

![]() $L_j^{(m)} = \hat {\boldsymbol e}_{\kern-1pt j}\boldsymbol{\cdot }[\boldsymbol{m}\times \boldsymbol{H}]$

are the projections of the magnetic torque

$L_j^{(m)} = \hat {\boldsymbol e}_{\kern-1pt j}\boldsymbol{\cdot }[\boldsymbol{m}\times \boldsymbol{H}]$

are the projections of the magnetic torque

![]() $\boldsymbol L_m$

onto these axes and

$\boldsymbol L_m$

onto these axes and

![]() $\partial /\partial \eta _j$

stand for infinitesimal rotations about the axes

$\partial /\partial \eta _j$

stand for infinitesimal rotations about the axes

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol e}_{\kern-1pt j}$

,

$\hat {\boldsymbol e}_{\kern-1pt j}$

,

\begin{eqnarray} &\displaystyle \frac {\partial }{\partial \eta _1}=\frac {s_{\psi }}{s_{\theta }}\left (\frac {\partial }{\partial \varphi } -c_{\theta }\frac {\partial }{\partial \psi }\right )+c_{\psi }\frac {\partial }{\partial \theta }\,,\nonumber \\ &\displaystyle \frac {\partial }{\partial \eta _2}=\frac {c_{\psi }}{s_{\theta }}\left (\frac {\partial }{\partial \varphi } -c_{\theta }\frac {\partial }{\partial \psi }\right )-s_{\psi }\frac {\partial }{\partial \theta }\,,\nonumber \\ &\displaystyle \frac {\partial }{\partial \eta _3}=\frac {\partial }{\partial \psi }\,, \end{eqnarray}

\begin{eqnarray} &\displaystyle \frac {\partial }{\partial \eta _1}=\frac {s_{\psi }}{s_{\theta }}\left (\frac {\partial }{\partial \varphi } -c_{\theta }\frac {\partial }{\partial \psi }\right )+c_{\psi }\frac {\partial }{\partial \theta }\,,\nonumber \\ &\displaystyle \frac {\partial }{\partial \eta _2}=\frac {c_{\psi }}{s_{\theta }}\left (\frac {\partial }{\partial \varphi } -c_{\theta }\frac {\partial }{\partial \psi }\right )-s_{\psi }\frac {\partial }{\partial \theta }\,,\nonumber \\ &\displaystyle \frac {\partial }{\partial \eta _3}=\frac {\partial }{\partial \psi }\,, \end{eqnarray}

where we used the compact notation

![]() $c_{\psi }\equiv \cos {\psi }$

,

$c_{\psi }\equiv \cos {\psi }$

,

![]() $s_{\theta }\equiv \sin {\theta }$

, etc.

$s_{\theta }\equiv \sin {\theta }$

, etc.

We are interested in the steady solution of the Fokker–Planck equation (3.1) in the rotating magnetic field

![]() $\boldsymbol H$

in (2.2). It is convenient to pass to a laboratory frame corotating with frequency

$\boldsymbol H$

in (2.2). It is convenient to pass to a laboratory frame corotating with frequency

![]() $\boldsymbol \omega$

with the driving field, which then becomes time independent,

$\boldsymbol \omega$

with the driving field, which then becomes time independent,

such that the Fokker–Planck equation takes the form

\begin{align} \frac {\partial W}{\partial t}= \sum _{j=1}^3 \left [D_j \frac {\partial ^2 W}{\partial \eta _j^2}-\frac {D_j}{k_{B}T}\frac {\partial }{\partial \eta _j}(L_j^{(m)}W)+\omega _j\frac {\partial W}{\partial \eta _j}\right ]\!, \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial W}{\partial t}= \sum _{j=1}^3 \left [D_j \frac {\partial ^2 W}{\partial \eta _j^2}-\frac {D_j}{k_{B}T}\frac {\partial }{\partial \eta _j}(L_j^{(m)}W)+\omega _j\frac {\partial W}{\partial \eta _j}\right ]\!, \end{align}

where

![]() $\omega _j$

is the

$\omega _j$

is the

![]() $j$

th component of the angular velocity of the field rotation in the body frame:

$j$

th component of the angular velocity of the field rotation in the body frame:

Substituting (3.2) and (3.5) into the last term of (3.4) yields

\begin{align} \sum _{j=1}^3 \omega _j\frac {\partial W}{\partial \eta _j}=\omega \frac {\partial W}{\partial \varphi }\,. \end{align}

\begin{align} \sum _{j=1}^3 \omega _j\frac {\partial W}{\partial \eta _j}=\omega \frac {\partial W}{\partial \varphi }\,. \end{align}

The dimensionless projections of the magnetic torque,

![]() $\hat {L}_{\kern-1.5pt j}^{(m)} = L_j^{(m)}/(\textit{mH})$

, read

$\hat {L}_{\kern-1.5pt j}^{(m)} = L_j^{(m)}/(\textit{mH})$

, read

\begin{eqnarray} \hat {L}_1^{(m)}&=&n_{2}(\boldsymbol{h}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3)-n_{3}(\boldsymbol{h}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {\boldsymbol e}_2)\,, \nonumber \\ \hat {L}_2^{(m)}&=&-n_{1}(\boldsymbol{h}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3)+n_{3}(\boldsymbol{h}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {\boldsymbol e}_1)\,,\nonumber \\ \hat {L}_3^{(m)}&=&n_{1}(\boldsymbol{h}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {\boldsymbol e}_2)+n_{2}(\boldsymbol{h}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {\boldsymbol e}_1)\,, \end{eqnarray}

\begin{eqnarray} \hat {L}_1^{(m)}&=&n_{2}(\boldsymbol{h}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3)-n_{3}(\boldsymbol{h}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {\boldsymbol e}_2)\,, \nonumber \\ \hat {L}_2^{(m)}&=&-n_{1}(\boldsymbol{h}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3)+n_{3}(\boldsymbol{h}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {\boldsymbol e}_1)\,,\nonumber \\ \hat {L}_3^{(m)}&=&n_{1}(\boldsymbol{h}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {\boldsymbol e}_2)+n_{2}(\boldsymbol{h}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {\boldsymbol e}_1)\,, \end{eqnarray}

where

![]() $n_i$

are the corresponding components of the magnetic moment director,

$n_i$

are the corresponding components of the magnetic moment director,

![]() ${\boldsymbol n}=n_1\hat {\boldsymbol e}_1+n_2\hat {\boldsymbol e}_2+n_3\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3$

in (2.3).

${\boldsymbol n}=n_1\hat {\boldsymbol e}_1+n_2\hat {\boldsymbol e}_2+n_3\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3$

in (2.3).

Using the dimensionless frequency

![]() $\widetilde {\omega }$

, the Péclet number, the longitudinal

$\widetilde {\omega }$

, the Péclet number, the longitudinal

![]() $p$

and transverse

$p$

and transverse

![]() $\varepsilon$

rotational anisotropy parameters introduced in § 2, we arrive at the final form of the Fokker–Planck equation for the steady-state orientation of the magnetic nanobot:

$\varepsilon$

rotational anisotropy parameters introduced in § 2, we arrive at the final form of the Fokker–Planck equation for the steady-state orientation of the magnetic nanobot:

\begin{align} \widetilde {\omega }\,\textit{Pe}\frac {\partial W}{\partial \varphi }+\frac {1}{1+\varepsilon }\frac {\partial ^2 W}{\partial \eta _1^2}+ \frac {1}{1-\varepsilon }\frac {\partial ^2 W}{\partial \eta _2^2}+p\frac {\partial ^2 W}{\partial \psi ^2}= \textit{Pe} \sum _{j=1}^3 \frac {\partial }{\partial \eta _{j}} \big(\hat {L}_{j}^{(m)}W \big). \end{align}

\begin{align} \widetilde {\omega }\,\textit{Pe}\frac {\partial W}{\partial \varphi }+\frac {1}{1+\varepsilon }\frac {\partial ^2 W}{\partial \eta _1^2}+ \frac {1}{1-\varepsilon }\frac {\partial ^2 W}{\partial \eta _2^2}+p\frac {\partial ^2 W}{\partial \psi ^2}= \textit{Pe} \sum _{j=1}^3 \frac {\partial }{\partial \eta _{j}} \big(\hat {L}_{j}^{(m)}W \big). \end{align}

We solve (3.8) as the series expansion over the Wigner

![]() $D$

-matrix (Landau & Lifshitz Reference Landau and Lifshitz1977):

$D$

-matrix (Landau & Lifshitz Reference Landau and Lifshitz1977):

\begin{align} W(\varphi ,\theta ,\psi )=\sum _{j=0}^{\infty }\sum _{m=-j}^j\sum _{k=-j}^j b^j_{mk} D^j_{mk}(\varphi ,\theta ,\psi )\,. \end{align}

\begin{align} W(\varphi ,\theta ,\psi )=\sum _{j=0}^{\infty }\sum _{m=-j}^j\sum _{k=-j}^j b^j_{mk} D^j_{mk}(\varphi ,\theta ,\psi )\,. \end{align}

The representation (3.9) reduces the Fokker–Planck equation to an infinite set of coupled three-index recurrence equations for the complex amplitudes

![]() $b^j_{mk}$

. To solve this set of equations, we truncate all amplitudes with

$b^j_{mk}$

. To solve this set of equations, we truncate all amplitudes with

![]() $j\ge 11$

and solve numerically the resulting linear system of

$j\ge 11$

and solve numerically the resulting linear system of

![]() $1771$

equations. The computed amplitudes

$1771$

equations. The computed amplitudes

![]() $b^{j}_{mk}$

determine the distribution function

$b^{j}_{mk}$

determine the distribution function

![]() $W$

in (3.9).

$W$

in (3.9).

Next, we can now compute the average values of various dependent variables as

For example, the average nanobot orientations (i.e. projections of the body axes on laboratory frame axes)

![]() $\langle \hat {\boldsymbol e}_i\rangle$

, after long but straightforward calculations (see Tripathi et al. (Reference Tripathi, Morozov, Rubinstein and Leshansky2025) for details), yield

$\langle \hat {\boldsymbol e}_i\rangle$

, after long but straightforward calculations (see Tripathi et al. (Reference Tripathi, Morozov, Rubinstein and Leshansky2025) for details), yield

The mean value of the sine of the wobbling angle,

![]() $\sin {\theta }$

can be expanded in series in terms of Legendre polynomials,

$\sin {\theta }$

can be expanded in series in terms of Legendre polynomials,

![]() $P_l(\cos {\theta })\!\equiv \!D^{l}_{00}$

(Ryzhik & Gradstein Reference Ryzhik and Gradstein2007),

$P_l(\cos {\theta })\!\equiv \!D^{l}_{00}$

(Ryzhik & Gradstein Reference Ryzhik and Gradstein2007),

\begin{align} \sin {\theta }=\frac {\pi }{2}\left [\frac {1}{2}-\sum _{k=1}\frac {4k+1}{2^{2k+1}(2k-1)(k+1)}\left (\frac {(2k-1)!!}{k!}\right )^2P_{2k}(\cos {\theta })\right ]\!, \end{align}

\begin{align} \sin {\theta }=\frac {\pi }{2}\left [\frac {1}{2}-\sum _{k=1}\frac {4k+1}{2^{2k+1}(2k-1)(k+1)}\left (\frac {(2k-1)!!}{k!}\right )^2P_{2k}(\cos {\theta })\right ]\!, \end{align}

with the mean value

\begin{align} \langle \sin {\theta }\rangle =\frac {\pi }{2}\left [\frac {1}{2}-\sum _{k=1}\frac {b^{2k}_{00}}{2^{2k+1}(2k-1)(k+1)}\left (\frac {(2k-1)!!}{k!}\right )^2\right ]\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} \langle \sin {\theta }\rangle =\frac {\pi }{2}\left [\frac {1}{2}-\sum _{k=1}\frac {b^{2k}_{00}}{2^{2k+1}(2k-1)(k+1)}\left (\frac {(2k-1)!!}{k!}\right )^2\right ]\!. \end{align}

Let us determine now the average angular velocity

![]() $\langle {\varOmega }_z\rangle$

of the nanobot subject to thermal noise. To simplify the derivation, we shall assume negligible transverse rotational anisotropy with

$\langle {\varOmega }_z\rangle$

of the nanobot subject to thermal noise. To simplify the derivation, we shall assume negligible transverse rotational anisotropy with

![]() $\varepsilon = 0$

. In such case, the lower amplitudes

$\varepsilon = 0$

. In such case, the lower amplitudes

![]() $b^j_{mk}$

with indices

$b^j_{mk}$

with indices

![]() $j\! \le \!2$

of the Fokker–Plank (3.1) satisfy the following relations:

$j\! \le \!2$

of the Fokker–Plank (3.1) satisfy the following relations:

where the star implies complex conjugate. Then the angular velocity in the body reference frame reads

Substituting the projections of the magnetic torque

![]() ${L}_{\kern-1.5pt j}^{(m)}=\textit{mH}\hat {L}_{\kern-1.5pt j}^{(m)}$

and

${L}_{\kern-1.5pt j}^{(m)}=\textit{mH}\hat {L}_{\kern-1.5pt j}^{(m)}$

and

![]() $\omega _0=\textit{mH}{\mathcal F}_{\perp }$

into (3.23) gives

$\omega _0=\textit{mH}{\mathcal F}_{\perp }$

into (3.23) gives

Under the assumption of cylindrical rotational anisotropy we substitute

![]() $n_2 = 0$

,

$n_2 = 0$

,

![]() $n_1\! \equiv \! n_{\perp } = s_{\varPhi }$

and

$n_1\! \equiv \! n_{\perp } = s_{\varPhi }$

and

![]() $n_3 \! \equiv \! n_{\|} = c_{\varPhi }$

into (3.7), so that the expressions for

$n_3 \! \equiv \! n_{\|} = c_{\varPhi }$

into (3.7), so that the expressions for

![]() $\hat {L}_{\kern-1.5pt j}^{(m)}$

reduce to

$\hat {L}_{\kern-1.5pt j}^{(m)}$

reduce to

In the laboratory frame the angular velocity can be found from

![]() $\boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}={\boldsymbol R}^T\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}{}^{{b}}$

, where the rotation matrix in terms of the Euler angles reads

$\boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}={\boldsymbol R}^T\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{{\widehat {\varOmega }}}{}^{{b}}$

, where the rotation matrix in terms of the Euler angles reads

\begin{align} {\boldsymbol R}^T = \begin{pmatrix} c_{\varphi }c_{\psi }-s_{\varphi }s_{\psi }c_{\theta } & -c_{\varphi }s_{\psi }-s_{\varphi }c_{\psi }c_{\theta } & s_{\varphi }s_{\theta } \\ s_{\varphi }c_{\psi }+c_{\varphi }s_{\psi }c_{\theta } & {-s_{\varphi }s_{\psi }+c_{\varphi }c_{\psi }c_{\theta }} & -c_{\varphi }s_{\theta } \\ s_{\psi }s_{\theta } & c_{\psi }s_{\theta } & c_{\theta } \end{pmatrix}\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} {\boldsymbol R}^T = \begin{pmatrix} c_{\varphi }c_{\psi }-s_{\varphi }s_{\psi }c_{\theta } & -c_{\varphi }s_{\psi }-s_{\varphi }c_{\psi }c_{\theta } & s_{\varphi }s_{\theta } \\ s_{\varphi }c_{\psi }+c_{\varphi }s_{\psi }c_{\theta } & {-s_{\varphi }s_{\psi }+c_{\varphi }c_{\psi }c_{\theta }} & -c_{\varphi }s_{\theta } \\ s_{\psi }s_{\theta } & c_{\psi }s_{\theta } & c_{\theta } \end{pmatrix}\!. \end{align}

Therefore, the scaled

![]() $z$

-component of the angular velocity in the laboratory frame reads

$z$

-component of the angular velocity in the laboratory frame reads

Substituting the expressions for

![]() $\hat {L}_{\kern-1.5pt j}^{(m)}$

in (3.25) and projecting the equation onto the Wigner functions yields, after some algebra,

$\hat {L}_{\kern-1.5pt j}^{(m)}$

in (3.25) and projecting the equation onto the Wigner functions yields, after some algebra,

\begin{eqnarray} \widehat {\varOmega }_z&=& \frac {{i}(p+1)}{4}{n_\perp }\big(D^1_{11}+D^1_{1-1}-D^1_{-11}-D^1_{-1-1} \big)+ \nonumber \\ && \frac {{i}(p-1)}{4}{n_\perp } \big(D^2_{11}-D^2_{1-1}+D^2_{-11}+D^2_{-1-1} \big) -\frac {{i}}{\sqrt {2}} {n_\|}\big(D^1_{01}+D^1_{0-1} \big). \end{eqnarray}

\begin{eqnarray} \widehat {\varOmega }_z&=& \frac {{i}(p+1)}{4}{n_\perp }\big(D^1_{11}+D^1_{1-1}-D^1_{-11}-D^1_{-1-1} \big)+ \nonumber \\ && \frac {{i}(p-1)}{4}{n_\perp } \big(D^2_{11}-D^2_{1-1}+D^2_{-11}+D^2_{-1-1} \big) -\frac {{i}}{\sqrt {2}} {n_\|}\big(D^1_{01}+D^1_{0-1} \big). \end{eqnarray}

Upon thermal averaging over the distribution function in (3.10) we finally obtain

\begin{eqnarray} \langle \widehat {\varOmega }_z\rangle &=&-\frac {{i}(p+1)}{12}{n_\perp } \big(b^1_{11}+b^1_{1-1}-b^1_{-11}-b^1_{-1-1} \big) \nonumber \\ && -\frac {{i}(p-1)}{20}{n_\perp }\big(b^2_{11}-b^2_{1-1}+b^2_{-11}-b^2_{-1-1} \big) +\frac {{i}\sqrt {2}}{6} {n_\|}\big(b^1_{01}+b^1_{0-1} \big), \end{eqnarray}

\begin{eqnarray} \langle \widehat {\varOmega }_z\rangle &=&-\frac {{i}(p+1)}{12}{n_\perp } \big(b^1_{11}+b^1_{1-1}-b^1_{-11}-b^1_{-1-1} \big) \nonumber \\ && -\frac {{i}(p-1)}{20}{n_\perp }\big(b^2_{11}-b^2_{1-1}+b^2_{-11}-b^2_{-1-1} \big) +\frac {{i}\sqrt {2}}{6} {n_\|}\big(b^1_{01}+b^1_{0-1} \big), \end{eqnarray}

which can be further simplified with the help of (3.22):

Finally, to determine the propulsion velocity, we assume that the coupling mobility tensor

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{G}}$

is dominated by its diagonal component

$\boldsymbol{\mathcal{G}}$

is dominated by its diagonal component

![]() ${\mathcal G}_{33}=\mathcal{G}_\|$

associated with chirality along the easy rotation axes

${\mathcal G}_{33}=\mathcal{G}_\|$

associated with chirality along the easy rotation axes

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3$

. Substituting (3.24) and (3.26) into (2.21) we obtain

$\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3$

. Substituting (3.24) and (3.26) into (2.21) we obtain

where

![]() ${\textit{Ch}}_\| = {\mathcal G}_\|/({\mathcal F}_\| \ell )$

. Integrating over the distribution function in (3.10) we finally arrive at

${\textit{Ch}}_\| = {\mathcal G}_\|/({\mathcal F}_\| \ell )$

. Integrating over the distribution function in (3.10) we finally arrive at

4. Results

4.1. Effect of thermal noise on the angular dynamics

Recall that under the assumption

![]() ${\boldsymbol F}_B=0$

the angular dynamics decouples from propulsion and is governed solely by the rotational mobility

${\boldsymbol F}_B=0$

the angular dynamics decouples from propulsion and is governed solely by the rotational mobility

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}$

. Since

$\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}$

. Since

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}$

has a diagonal form in the principal rotation body frame, the solution for driven angular dynamics of an arbitrarily shaped propeller depends on just two scalar anisotropy parameters

$\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}$

has a diagonal form in the principal rotation body frame, the solution for driven angular dynamics of an arbitrarily shaped propeller depends on just two scalar anisotropy parameters

![]() $p$

and

$p$

and

![]() $\varepsilon$

defined above in § 2, and the magnetization via the orientation (i.e. the angles

$\varepsilon$

defined above in § 2, and the magnetization via the orientation (i.e. the angles

![]() $\varPhi$

and

$\varPhi$

and

![]() $\alpha$

) and magnitude of the magnetic moment

$\alpha$

) and magnitude of the magnetic moment

![]() $\boldsymbol m$

(see figure 1

b).

$\boldsymbol m$

(see figure 1

b).

Although the general solution of the torque-driven actuation of the non-Brownian propeller is available for arbitrary geometry and magnetization (Morozov et al. Reference Morozov, Mirzae, Kenneth and Leshansky2017), the transverse rotational anisotropy of an arbitrary rigid object is quite small,

![]() $\varepsilon \ll 1$

. For example, for a one-turn helical propeller in figure 1(b),

$\varepsilon \ll 1$

. For example, for a one-turn helical propeller in figure 1(b),

![]() $\varepsilon \simeq 0.03$

, while for a two-turn helix in figure 1(c) it is already

$\varepsilon \simeq 0.03$

, while for a two-turn helix in figure 1(c) it is already

![]() $\varepsilon \simeq 0.006$

(Morozov et al. Reference Morozov, Mirzae, Kenneth and Leshansky2017). More generally, for random fractal-like clusters the average transverse rotational anisotropy was found to be

$\varepsilon \simeq 0.006$

(Morozov et al. Reference Morozov, Mirzae, Kenneth and Leshansky2017). More generally, for random fractal-like clusters the average transverse rotational anisotropy was found to be

![]() $\varepsilon \approx 0.07$

(Mirzae et al. Reference Mirzae, Dubrovski, Kenneth, Morozov and Leshansky2018), with some exotic structures reaching

$\varepsilon \approx 0.07$

(Mirzae et al. Reference Mirzae, Dubrovski, Kenneth, Morozov and Leshansky2018), with some exotic structures reaching

![]() $\varepsilon \approx 0.3$

. We therefore first consider the effect of thermal fluctuations on torque-driven dynamics assuming cylindrical anisotropy of the helical nanobot,

$\varepsilon \approx 0.3$

. We therefore first consider the effect of thermal fluctuations on torque-driven dynamics assuming cylindrical anisotropy of the helical nanobot,

![]() ${\mathcal F}_1 = {\mathcal F}_2 \lt {\mathcal F}_3$

, i.e. for

${\mathcal F}_1 = {\mathcal F}_2 \lt {\mathcal F}_3$

, i.e. for

![]() $\varepsilon =0$

. This approximation simplifies the general solution considerably, as the angular dynamics is now controlled by a single hydrodynamic parameter

$\varepsilon =0$

. This approximation simplifies the general solution considerably, as the angular dynamics is now controlled by a single hydrodynamic parameter

![]() $p={\mathcal F}_3/{\mathcal F}_1$

and a single (polar) magnetization angle,

$p={\mathcal F}_3/{\mathcal F}_1$

and a single (polar) magnetization angle,

![]() $\varPhi$

. In the next section we first consider this useful approximation, while the general case corresponding to finite

$\varPhi$

. In the next section we first consider this useful approximation, while the general case corresponding to finite

![]() $\varepsilon$

will be studied later.

$\varepsilon$

will be studied later.

4.1.1. Cylindrical rotational anisotropy

In this section, we consider the angular dynamics of the propeller whose torque-driven rotation is approximated by that of a cylinder with

![]() $\varepsilon = 0$

. The angular dynamics of non-Brownian propellers has been extensively studied (Ghosh et al. Reference Ghosh, Mandal, Karmakar and Ghosh2013; Morozov & Leshansky Reference Morozov and Leshansky2014a

; Morozov et al. Reference Morozov, Mirzae, Kenneth and Leshansky2017; Mirzae et al. Reference Mirzae, Dubrovski, Kenneth, Morozov and Leshansky2018). It gives rise to two distinct regimes of synchronous (i.e. in-sync with the rotating field) driven rotations: tumbling and wobbling. Tumbling corresponds to a low-frequency rotation in which the magnetic moment follows the applied magnetic field, while the propeller easy rotation axis

$\varepsilon = 0$

. The angular dynamics of non-Brownian propellers has been extensively studied (Ghosh et al. Reference Ghosh, Mandal, Karmakar and Ghosh2013; Morozov & Leshansky Reference Morozov and Leshansky2014a

; Morozov et al. Reference Morozov, Mirzae, Kenneth and Leshansky2017; Mirzae et al. Reference Mirzae, Dubrovski, Kenneth, Morozov and Leshansky2018). It gives rise to two distinct regimes of synchronous (i.e. in-sync with the rotating field) driven rotations: tumbling and wobbling. Tumbling corresponds to a low-frequency rotation in which the magnetic moment follows the applied magnetic field, while the propeller easy rotation axis

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3$

rotates in the

$\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3$

rotates in the

![]() $xy$

-plane of the field. When the magnetic field reaches a critical frequency

$xy$

-plane of the field. When the magnetic field reaches a critical frequency

![]() $\widetilde {\omega }_{\small {{t-w}}} = \cos {\varPhi }$

, the tumbling solution becomes unstable and bifurcates into the high-frequency wobbling rotation, where the easy rotation axis lifts off the

$\widetilde {\omega }_{\small {{t-w}}} = \cos {\varPhi }$

, the tumbling solution becomes unstable and bifurcates into the high-frequency wobbling rotation, where the easy rotation axis lifts off the

![]() $xy$

-plane and precesses around the field rotation

$xy$

-plane and precesses around the field rotation

![]() $z$

-axis. There are two symmetric steady in-sync rotations of the propeller with complementary to

$z$

-axis. There are two symmetric steady in-sync rotations of the propeller with complementary to

![]() $\pi$

precession or wobbling angles (defined as the angle between

$\pi$

precession or wobbling angles (defined as the angle between

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3$

and the

$\hat {\boldsymbol e}_3$

and the

![]() $z-$

axis),

$z-$

axis),

![]() $\theta$

and

$\theta$

and

![]() $\pi -\theta$

. The wobbling angle

$\pi -\theta$

. The wobbling angle

![]() $\theta$

diminishes with the driving frequency

$\theta$

diminishes with the driving frequency

![]() $\omega$

as

$\omega$

as

![]() $\sin \theta = \widetilde {\omega }^{-1} \cos \varPhi$

due to an intricate balance of magnetic and viscous torques (Morozov & Leshansky Reference Morozov and Leshansky2014a

). Beyond the so-called step-out frequency,

$\sin \theta = \widetilde {\omega }^{-1} \cos \varPhi$

due to an intricate balance of magnetic and viscous torques (Morozov & Leshansky Reference Morozov and Leshansky2014a

). Beyond the so-called step-out frequency,

![]() $\widetilde {\omega }_{\small {{s-o}}} = \sqrt {\cos ^2{\varPhi } + p^2\sin ^2{\varPhi }}$

, the viscous torque can no longer balance the magnetic torque and the in-sync wobbling solution breaks down and bifurcates into asynchronous twirling, whereas the Euler angles

$\widetilde {\omega }_{\small {{s-o}}} = \sqrt {\cos ^2{\varPhi } + p^2\sin ^2{\varPhi }}$

, the viscous torque can no longer balance the magnetic torque and the in-sync wobbling solution breaks down and bifurcates into asynchronous twirling, whereas the Euler angles

![]() $\theta , \psi , \widetilde {\varphi }={\varphi }\!-\!\omega t$

oscillate about their mean values (via Hopf bifurcation) (Morozov & Leshansky Reference Morozov and Leshansky2014a

). Notice that the transition from in-sync wobbling to asynchronous twirling is not sharp and occurs prior to the step out, at

$\theta , \psi , \widetilde {\varphi }={\varphi }\!-\!\omega t$

oscillate about their mean values (via Hopf bifurcation) (Morozov & Leshansky Reference Morozov and Leshansky2014a

). Notice that the transition from in-sync wobbling to asynchronous twirling is not sharp and occurs prior to the step out, at

![]() $\widetilde {\omega } \lt \widetilde {\omega }_{\small {{s-o}}}$

. This happens owing to fact that the basin of attraction of the steady-state wobbling narrows in the vicinity of the step-out and there are a sizable number of initial orientations for which the propeller asynchronously meanders without converging towards an attractor corresponding to the wobbling solution.

$\widetilde {\omega } \lt \widetilde {\omega }_{\small {{s-o}}}$

. This happens owing to fact that the basin of attraction of the steady-state wobbling narrows in the vicinity of the step-out and there are a sizable number of initial orientations for which the propeller asynchronously meanders without converging towards an attractor corresponding to the wobbling solution.

Figure 2. Thermal transition between the two symmetric branches of the wobbling solution at frequency

![]() $\widetilde \omega = 1.7$

for elongation

$\widetilde \omega = 1.7$

for elongation

![]() $p = 3$

and magnetization angle

$p = 3$

and magnetization angle

![]() $\varPhi = \pi /4$

, assuming cylindrical anisotropy,

$\varPhi = \pi /4$

, assuming cylindrical anisotropy,

![]() $\varepsilon = 0$

. The individual plots show the cosine of the wobbling angle,

$\varepsilon = 0$

. The individual plots show the cosine of the wobbling angle,

![]() $\cos {\theta }$

, versus the dimensionless time

$\cos {\theta }$

, versus the dimensionless time

![]() $\tilde t$

for (a)

$\tilde t$

for (a)

![]() $ \textit{Pe} = 100$

, (b)

$ \textit{Pe} = 100$

, (b)

![]() $ \textit{Pe} = 50$

, (c)

$ \textit{Pe} = 50$

, (c)

![]() $ \textit{Pe} = 20$

and (d)

$ \textit{Pe} = 20$

and (d)

![]() $ \textit{Pe} = 10$

. The dashed–dotted lines mark the steady-state wobbling angles of the non-Brownian propeller (with

$ \textit{Pe} = 10$

. The dashed–dotted lines mark the steady-state wobbling angles of the non-Brownian propeller (with

![]() $\cos {\theta } = \pm 0.91$

) .

$\cos {\theta } = \pm 0.91$

) .

Subject to thermal fluctuations, the rotation of the propeller becomes stochastic, with its orientation diffusing around the mean. We characterize this by measuring the average wobbling angle

![]() $\theta$

as a function of the dimensionless frequency,

$\theta$

as a function of the dimensionless frequency,

![]() $\widetilde {\omega } = \omega /\omega _0$

. Depending on the value of

$\widetilde {\omega } = \omega /\omega _0$

. Depending on the value of

![]() $ \textit{Pe}$

, the wobbling solutions can ‘jump’ from one branch of the orientational solution (

$ \textit{Pe}$

, the wobbling solutions can ‘jump’ from one branch of the orientational solution (

![]() $\theta$

) to a dual branch (

$\theta$

) to a dual branch (

![]() $\pi \!-\!\theta$

) similar to the thermal barrier crossing in bistable systems (Hänggi et al. Reference Hänggi, Talkner and Borkovec1990), as shown in figure 2. For low magnitude of the noise (

$\pi \!-\!\theta$

) similar to the thermal barrier crossing in bistable systems (Hänggi et al. Reference Hänggi, Talkner and Borkovec1990), as shown in figure 2. For low magnitude of the noise (

![]() $ \textit{Pe} \gtrsim 100$

) such transitions are rare events and the symmetric pitchfork bifurcation is preserved on average. Upon increasing the noise amplitude, the transitions become more frequent, leading to smearing across the two branches.

$ \textit{Pe} \gtrsim 100$

) such transitions are rare events and the symmetric pitchfork bifurcation is preserved on average. Upon increasing the noise amplitude, the transitions become more frequent, leading to smearing across the two branches.

Figure 3. Angular dynamics of the nanopropellers assuming cylindrical rotation anisotropy (

![]() $\varepsilon = 0$

) with elongation

$\varepsilon = 0$

) with elongation

![]() $p = 3$

and magnetization angle

$p = 3$

and magnetization angle

![]() $\varPhi = \pi /4$

, as a function of scaled actuation frequency,

$\varPhi = \pi /4$

, as a function of scaled actuation frequency,

![]() $\widetilde {\omega } = \omega /\omega _0$

, for some values of the Péclet number,

$\widetilde {\omega } = \omega /\omega _0$

, for some values of the Péclet number,

![]() $ \textit{Pe}$

. (a) Mean (sine of the) wobbling angle,

$ \textit{Pe}$

. (a) Mean (sine of the) wobbling angle,

![]() $\langle \sin \theta \rangle$

; (b) mean angular velocity of the driven rotation about the

$\langle \sin \theta \rangle$

; (b) mean angular velocity of the driven rotation about the

![]() $z$

-axis in the laboratory frame. The black dot–dashed curve stand for the analytical solution for non-Brownian propeller (Morozov et al. Reference Morozov, Mirzae, Kenneth and Leshansky2017), and solid curves correspond to the solutions of the Fokker–Planck equation. For non-Brownian propeller the tumbling-to-wobbling transition occurs at

$z$

-axis in the laboratory frame. The black dot–dashed curve stand for the analytical solution for non-Brownian propeller (Morozov et al. Reference Morozov, Mirzae, Kenneth and Leshansky2017), and solid curves correspond to the solutions of the Fokker–Planck equation. For non-Brownian propeller the tumbling-to-wobbling transition occurs at

![]() $\widetilde {\omega }_{\small {{t-w}}}=1/\sqrt {2}$

, and the theoretical step-out frequency

$\widetilde {\omega }_{\small {{t-w}}}=1/\sqrt {2}$

, and the theoretical step-out frequency

![]() $\widetilde {\omega }_{{\small {{s-o}}}}\simeq 2.24$

.

$\widetilde {\omega }_{{\small {{s-o}}}}\simeq 2.24$

.

The effect of the rotational diffusion on orientation and driven rotation of the nanobot is shown in figure 3(a,b). Recall that in the cylindrical approximation the two symmetric branches of the orientational solution yield the same value of

![]() $\langle \sin \theta \rangle$

(see figure 3

a). At low frequency, the mean wobbling angle deviates from the value of

$\langle \sin \theta \rangle$

(see figure 3

a). At low frequency, the mean wobbling angle deviates from the value of

![]() $\theta = \pi /2$

of the tumbling rotation. (Note that the terms ‘tumbling regime’ and ‘wobbling regime’ formally correspond to in-sync rotations of non-Brownian propellers. With thermal noise, these terms refer to the respective frequency intervals of the actuating field.) The precession angle

$\theta = \pi /2$

of the tumbling rotation. (Note that the terms ‘tumbling regime’ and ‘wobbling regime’ formally correspond to in-sync rotations of non-Brownian propellers. With thermal noise, these terms refer to the respective frequency intervals of the actuating field.) The precession angle

![]() $\theta$

varies non-monotonically with frequency, decreasing initially before attaining a minimum value (optimal orientation for particular

$\theta$

varies non-monotonically with frequency, decreasing initially before attaining a minimum value (optimal orientation for particular

![]() $ \textit{Pe}$

) at some intermediate frequency and then increasing afterwards as one approaches the step-out frequency. The precession angle increases inversely with

$ \textit{Pe}$

) at some intermediate frequency and then increasing afterwards as one approaches the step-out frequency. The precession angle increases inversely with

![]() $ \textit{Pe}$

, reaching a plateau value of

$ \textit{Pe}$

, reaching a plateau value of

![]() $\langle \sin {\theta }\rangle \approx 0.8$

(i.e.

$\langle \sin {\theta }\rangle \approx 0.8$

(i.e.

![]() $\langle \theta \rangle \approx 53^\circ$

) independent of frequency for

$\langle \theta \rangle \approx 53^\circ$

) independent of frequency for

![]() $ \textit{Pe} \lesssim 2$

. Notice that for relatively weak noise with

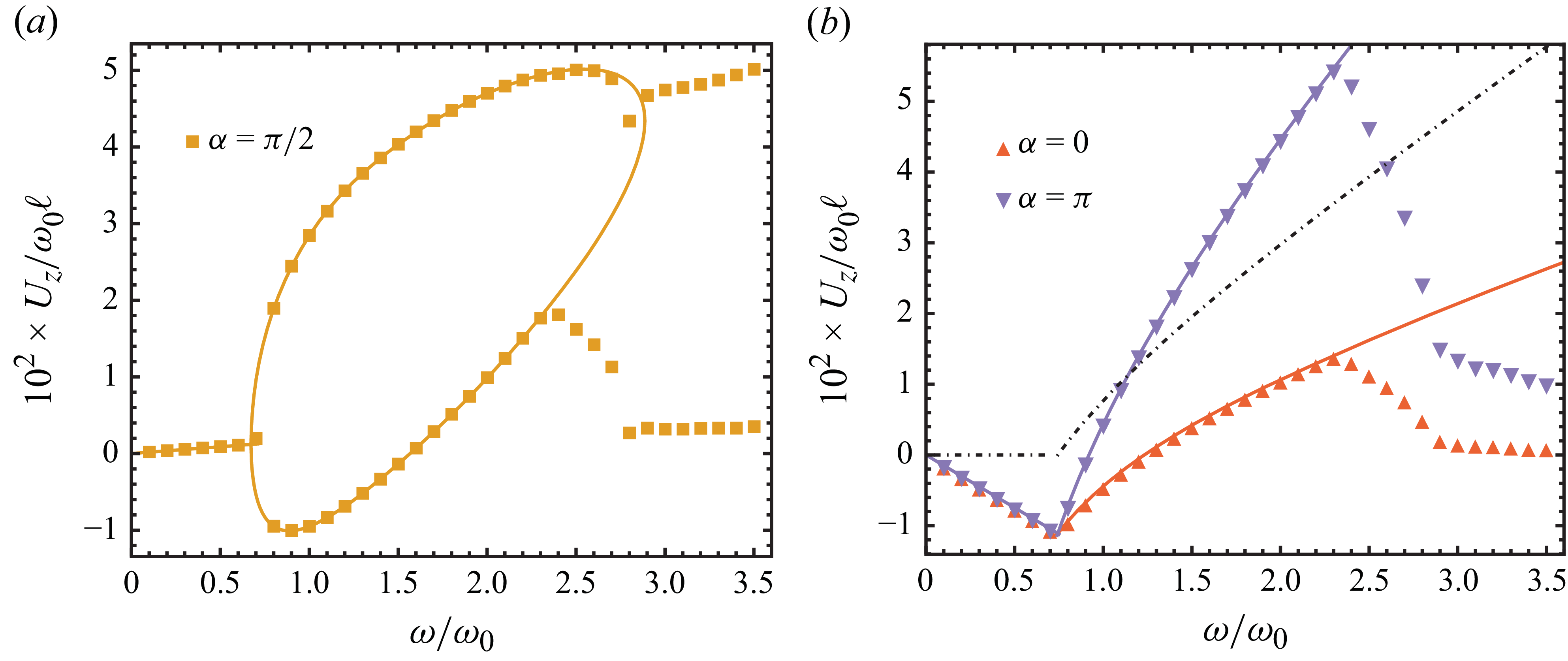

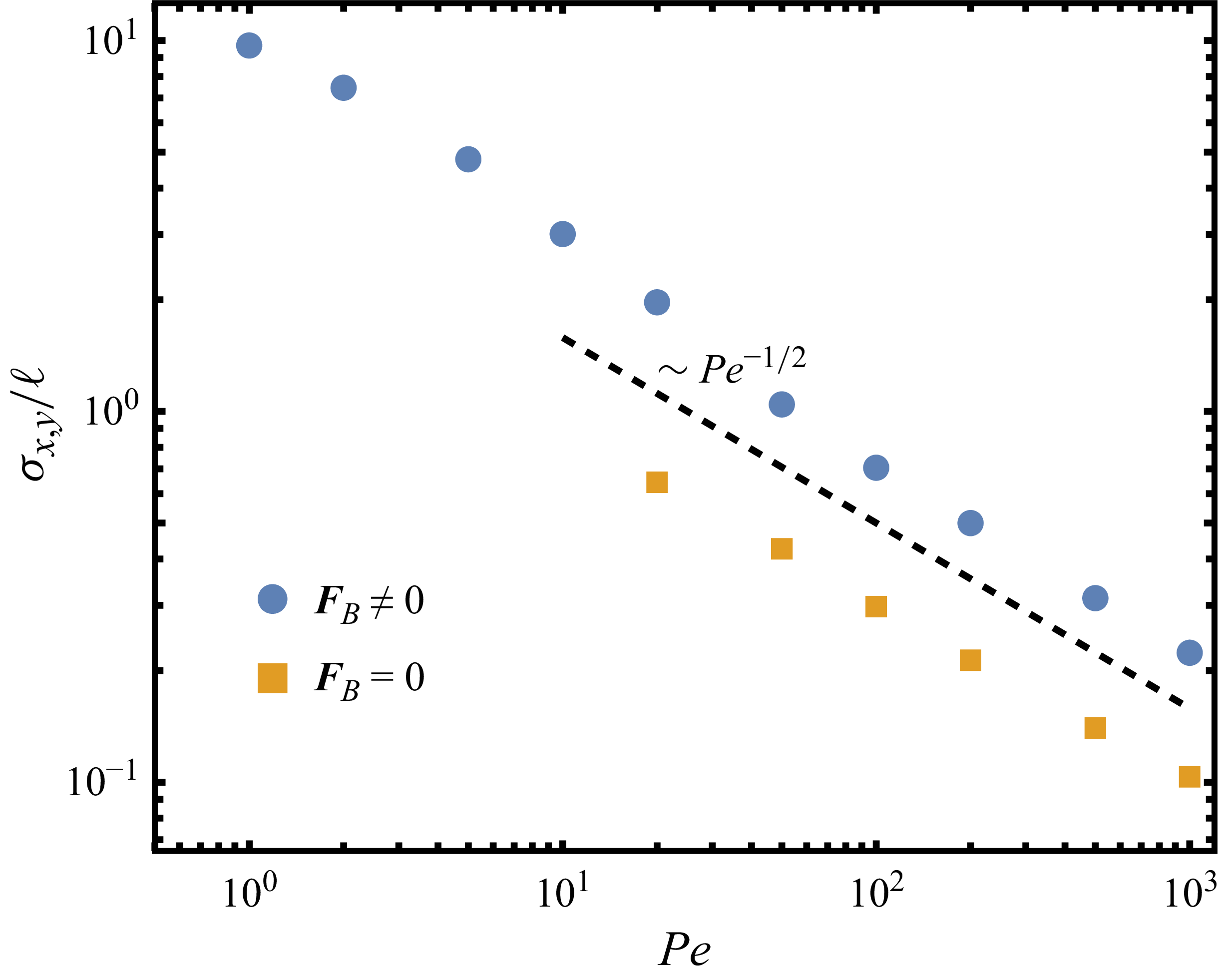

$ \textit{Pe} \lesssim 2$