Introduction

Emergency service workers such as firefighters make an enormous contribution to society’s safety by protecting citizens in case of fire, environmental disaster, or other emergency issues. In many Western countries such as Germany and Austria, volunteer fire departments support professional, paid fire departments. Professional fire departments are located in cities in most cases, whereas volunteers usually ensure safety in the wide rural areas across the country. While career firefighters are compensated for their services, volunteer firefighters perform occasional fire suppression or other emergency services on-call 24/7 on an honor basis while pursuing some other form of income. In addition to responding to calls for help (e.g., quenching a fire), many on-call firefighters volunteer for other non-emergency duties at the fire service. They spend their time and effort, for example, training young people, raising funding, or maintaining the equipment. Although these activities go beyond simple role descriptions, they are crucial for the survival of the organization, drive organizational success, and improve organizational effectiveness. In line with Schaubroeck and Ganster (Reference Schaubroeck and Ganster1991) and Somech and Drach-Zahavy (Reference Somech and Drach-Zahavy2000), these activities are characterized as extra-role behavior, defined as behavior that goes beyond specified role requirements and is geared toward fostering organizational goals.

Unfortunately, little is known about the conditions that promote the extra-role behaviors of volunteers in organizations. Although numerous studies have attempted to identify the personal characteristics of individuals that predict working extra hours (Organ Reference Organ1988; George and Bettenhausen Reference George and Bettenhausen1990; Somech and Drach-Zahavy Reference Somech and Drach-Zahavy2000), little research has focused on the extra-role behavior of volunteers (Schaubroeck and Ganster Reference Schaubroeck and Ganster1991; Millette and Gagné Reference Millette and Gagné2008; Shantz et al. Reference Shantz, Saksida and Alfes2014; Brauchli et al. Reference Brauchli, Peeters, Steenbergen, Wehner and Hämmig2017; Cady et al. Reference Cady, Brodke, Kim and Shoup2018). Consequently, this article examines the factors associated with volunteers’ extra-role behavior and questions the conditions under which volunteer firefighters go above and beyond their emergency duties (e.g., responding to 911 calls) and conduct extra work in a sense of prosocial organizational behavior.

First, extra-role behavior is proposed to be associated with the public service motivation (PSM) of volunteers, as individuals motivated by concerns for the public interest are more likely to volunteer and perform prosocial behavior (Brewer and Selden Reference Brewer and Selden1998; Houston Reference Houston2006). Second, this article aims to determine the PSM-extra-role behavior relationship by drawing on stewardship theory (Donaldson and Davis Reference Donaldson and Davis1991; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997). Stewardship theory explains individuals’ behavior based on individual motivation and provides a contrasting perspective to agency theory (Jensen and Meckling Reference Jensen and Meckling1976). This theory assumes that individuals’ behavior is driven by the interest of the organization (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997), which contradicts the model of man proposed by agency theory. Whereas “agents” are economically motivated to complete tasks, “stewards” have noneconomic motivation that makes them pursue pro-organizational behavior. This paper thus suggests that extra-role behavior is shaped by the degree to which fire departments adopt a stewardship perspective. The multi-faceted nature of a stewardship-oriented culture is captured by five characteristics (i.e., intrinsic motivation, job characteristics, commitment, organizational identification, and perceived organizational support). The link between PSM, stewardship-oriented culture, and extra-role behavior is empirically tested by quantitative data analysis using survey data collected from 475 Austrian and German volunteer firefighters.

This study contributes to the literature in multiple ways. First, it extends previous works on volunteer behaviors (e.g., van Schie et al. Reference Van Schie, Güntert, Oostlander and Wehner2015; Mayr Reference Mayr2017; Henderson and Sowa Reference Henderson and Sowa2018) by focusing on individuals who volunteer as firefighters in disaster and emergency service. It empirically examines the effect of PSM on the extra-role behavior of volunteer firefighters by arguing that altruistic beliefs relate to behavior oriented toward favoring society. Consequently, we propose that individuals with high PSM are more willing to work beyond the call of duty than those with low altruistic beliefs. We thus extend recent research that has suggested that individual beliefs and attitudes can significantly influence volunteer performance (e.g., Ertas Reference Ertas2014).

Second, this work contributes to research on PSM by questioning whether and how PSM relates to observable behavior (Bozeman and Su Reference Bozeman and Su2015) and testing the effect of PSM on volunteers’ extra-role behavior. Whereas past research has focused on the antecedents of PSM, scholars now aim to shed light on the outcomes of PSM on individual behavior (Campbell and Im Reference Campbell and Im2016; Van Loon et al. Reference Van Loon, Vandenabeele and Leisink2017; Shim and Faerman Reference Shim and Faerman2017; Kim Reference Kim2018; Leisink et al. Reference Leisink, Knies and van Loon2018). We aim to contribute to this literature.

Third, this study applies the ideas of stewardship theory in the context of volunteer emergency service and investigates how a stewardship-oriented culture might be related to extra-role behavior. Stewardship theory, in contrast to agency theory (Jensen and Meckling Reference Jensen and Meckling1976), is more appropriate and useful to explain employees’ motivation, relationships, and behaviors in a not-for-profit organization (Kluvers and Tippett Reference Kluvers and Tippett2011).

The remainder of this study is structured as follows. In second section, extra-role behavior is defined, and previous research is outlined. Thereafter, the stewardship perceptive is introduced, and hypotheses are formulated. Third section outlines the research setting. Fourth section describes the data collection and measures. Fifth section presents the results of multivariate analysis and discusses the findings. Final section outlines the implications of this research, provides directions for further research and concluding remarks.

Theory and Hypotheses

Extra-Role Behavior

Different forms of extra-role behavior are distinguished in the literature, such as organizational citizenship behavior (Organ Reference Organ1988), prosocial behavior (George and Bettenhausen Reference George and Bettenhausen1990), spontaneous behavior (George and Brief Reference George and Brief1992), and contextual behavior (Borman and Motowidlo Reference Borman, Motowidlo, Schmitt and Borman1993). Extra-role behavior can be defined as “behavior that is not a formal or informal aspect of the worker’s role but which in the aggregate promotes the organization’s goals” (Schaubroeck and Ganster Reference Schaubroeck and Ganster1991, 569). Somech and Drach-Zahavy (Reference Somech and Drach-Zahavy2000, 650) refer to extra-role behavior as “those behaviors that go beyond specified role requirements, and are directed towards the individual, the group, or the organization as a unit, in order to promote organizational goals.” Accordingly, extra-role behaviors must be voluntary, not part of the role description or formally required, and not formally rewarded or penalized if they are not performed (Van Dyne and LePine Reference Van Dyne and LePine1998; Somech and Drach-Zahavy Reference Somech and Drach-Zahavy2000). Finally, extra-role behavior must be advantageous for the organization (e.g., Turnipseed and Rassuli Reference Turnipseed and Rassuli2005).

This study defines extra-role behavior as those behaviors performed by individuals that go beyond specified role requirements and directly or indirectly benefit organizational goals and society, whereas in-role behavior is characterized by tasks in accordance with formally described roles. Extra-role behavior performed by firefighters can be seen as a specific type of extra-role work because it benefits both the organization by fulfilling organizational objectives and society at large.

Extra-role behaviors are shown to benefit organizational effectiveness and success (e.g., Podsakoff et al. Reference Podsakoff, Ahearne and MacKenzie1997). Furthermore, employees who demonstrate extra-role behavior are less likely to leave the organization (George and Bettenhausen Reference George and Bettenhausen1990). Previous research has found various antecedents of extra-role behavior, such as job satisfaction (Organ Reference Organ1988), organizational commitment (MacKenzie et al. Reference MacKenzie, Podsakoff and Ahearne1998), perceived fairness (Moorman et al. Reference Moorman, Niehoff and Organ1993), self-efficacy (Somech and Drach-Zahavy Reference Somech and Drach-Zahavy2000), collective efficacy (Somech and Drach-Zahavy Reference Somech and Drach-Zahavy2000), intrinsic and extrinsic job cognition (Williams and Anderson Reference Williams and Anderson1991), group cohesiveness and socialization experiences (George and Bettenhausen Reference George and Bettenhausen1990).

Public Service Motivation and Extra-Role Behavior

The literature on PSM, defined as “an individual’s predisposition to respond to motives grounded primarily or uniquely in public institutions and organizations” (Perry and Wise Reference Perry and Wise1990, 368), assumes that individuals who provide a public service have special motives for work engagement compared to those working in the private sector (Frederickson and Hart Reference Frederickson and Hart1985; Perry and Porter Reference Perry and Porter1982; Ritz et al. Reference Ritz, Brewer and Neumann2016). PSM helps to explain motivation and behavior in the public realm and is characterized by individuals’ intention of doing good for others and fostering the well-being of society (Perry and Hondeghem Reference Perry and Hondeghem2008). Individuals with high levels of PSM have a strong desire to help people and service society at large (Perry and Wise Reference Perry and Wise1990; Rainey and Steinbauer Reference Rainey and Steinbauer1999).

PSM is not used only to explain why public employees have a greater focus on serving the public interest than those working in the private sector (Rainey and Steinbauer Reference Rainey and Steinbauer1999). Scholars have applied the construct to capture the work motivation of private sector employees (Moulton and Feeney Reference Moulton and Feeney2011), nonprofit employees (Taylor Reference Taylor2010), and volunteers (Coursey et al. Reference Coursey, Perry, Brudney and Littlepage2008) and thus consider PSM a “behavioral predisposition of any individual, irrespective of whether or where he or she is employed rather than a characteristic specific to the public sector” (Esteve et al. Reference Esteve, Urbig, Van Witteloostuijn and Boyne2016, 178). In addition to exploring the antecedents of PSM (e.g., Moynihan and Pandey Reference Moynihan and Pandey2007), scholars call for research on the behavioral implications of PSM to test whether individuals with high levels of PSM are more prone to act in favor of communities and societies (Brewer Reference Brewer, Perry and Hondeghem2008; Bozeman and Su Reference Bozeman and Su2015).

Although empirical research on the consequences of PSM on behavior is scarce (Ritz Reference Ritz2009), previous research provides the first results of the effect of PSM on observable behavior. These studies focus on behavioral outcomes either outside or inside the organization. First, in explaining individual involvement in charitable activities, Houston (Reference Houston2006) showed that government and nonprofit employees are more likely to volunteer than for-profit workers and explain this difference in prosocial behavior based on PSM. Using a sample of undergraduates, Clerkin et al. (Reference Clerkin, Paynter and Taylor2009) found a positive effect of PSM on volunteering and donating. Esteve et al. (Reference Esteve, Urbig, Van Witteloostuijn and Boyne2016) tested the effect of PSM on prosocial behavior and found that the relationship is even stronger when the prosocial behavior of other group members is high. Recently, Leisink et al. (Reference Leisink, Knies and van Loon2018) found that public interest commitment had a positive effect on volunteering activities among Dutch public and semi-public employees.

Second, studies have focused on the influence of PSM on organizational behavior and performance. Kim (Reference Kim2006) studied the organizational citizenship behavior of Korean civil servants and found a positive effect of PSM on altruism and generalized compliance. Ritz (Reference Ritz2009) related the PSM of the Swiss federal administration to internal efficiency in terms of cost reduction, process simplification, and decision making. Findings from Pandey et al. (Reference Pandey, Wright and Moynihan2008) indicated a positive and significant effect of PSM on an individual’s helping behavior directed at co-workers. Shim and Faerman (Reference Shim and Faerman2017) and Kim (Reference Kim2018) investigated PSM in the Korean public sector and found a positive link between PSM and organizational citizenship behavior and PSM and knowledge sharing behavior.

In summary, individuals with high levels of PSM are highly concerned with serving the public interest. PSM is linked to prosocial behavior because the desire to serve the public interest is expected to relate to behavior oriented toward favoring society. Initial empirical research on the behavioral implications of PSM provides support for the notion that PSM is related to volunteering for society at large and to prosocial organizational behavior. This study thus argues that the individual predisposition to act in favor of society positively relates to extra-role behavior.

Hypothesis 1

PSM is positively associated with extra-role behavior.

Stewardship Theory

Stewardship theory, a theory derived from psychology and sociology, explains human behavior based on individual motivation and offers a contrasting perspective to agency theory (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997). Agency theory (Jensen and Meckling Reference Jensen and Meckling1976) assumes that individuals are rational beings who seek to maximize their individual utility. When principals (e.g., stakeholders, stockholders) charge agents (e.g., firms) with managing the principals’ wealth, financial incentives or monitoring instruments are used to govern principal-agency relationships to secure the principals’ interest. Agency theory, however, has its limits and is criticized due to its model of man as a self-serving utility maximizer while ignoring the complexity of human action and organizational life (e.g., Doucouliagos Reference Doucouliagos1994; Hirsch et al. Reference Hirsch, Michaels and Friedman1987; Jensen and Meckling Reference Jensen and Meckling1994).

Stewardship theory responds to the shortcomings of agency theory by studying “situations in which executives as stewards are motivated to act in the best interests of their principals” (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997, 24; Donaldson and Davis Reference Donaldson and Davis1991). In contrast to agency theory (Jensen and Meckling Reference Jensen and Meckling1976), stewardship theory assumes that individuals’ behavior is not self-interested but is driven by the interests of the organization. Although there might be a conflict between personal needs and organizational objectives, stewards are assumed to act pro-organizationally because they perceive the utility gained from pro-organizational behavior to be higher than the utility gained from individualistic, self-serving behavior (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997). In addition to psychological factors, stewardship theory assumes that the steward’s performance is influenced by the structural situation in which the behavior is performed. Accordingly, stewardship outcomes are dependent on specific organizational structures (Hernandez Reference Hernandez2008), which aligns with findings from volunteer research (Van Schie et al. Reference Van Schie, Güntert, Oostlander and Wehner2015). Whereas governance and control mechanisms are not adequate to promote stewards’ pro-organizational behavior but rather lower their motivation (Argyris Reference Argyris1964), stewardship theory promotes organizational structures that facilitate and empower (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997).

Stewardship as a Moderator of Motivation–Behavior Relationship

This article argues that the stewardship perspective helps to understand why some volunteers show more extra-role behavior than others. In addition to the hypothesized direct effect of PSM on extra-role behavior, it assumes that the strength of the motivation-behavior relationship is dependent on the organizational setting and thus formulates alternative hypotheses. According to the management and organization science literature (Barnard Reference Barnard1938; Fleming and Spicer Reference Fleming and Spicer2014), organizations shape the beliefs and behaviors of their members by a variety of formal and informal mechanisms. This study argues that PSM by itself does relate to extra-role behavior, but its interaction with variables in the organizational culture strengthens individuals’ willingness to work extra hours. Accordingly, the relationship between PSM and extra-role behavior depends on a stewardship-oriented organizational culture. If PSM-motivated individuals’ perception of the work and organizational context corresponds with the ideas of the stewardship approach, these individuals perform higher levels of extra-role behavior than those working in organizations with no stewardship orientation. A stewardship-oriented culture is thus seen as a promoting work environment.

Instead of testing the effect of a stewardship-oriented culture using a single construct, the multi-faceted nature of stewardship is illustrated by focusing on different aspects of stewardship. Drawing from previous research, we select five features of a stewardship culture that we assume influence individual decisions to work extra hours in fire service. We use two criteria in choosing each determinant: It must reflect the values espoused by stewardship theory, and previous research on volunteering indicates that it supports extra-role behavior. In the following, we develop five hypotheses on the characteristics of a stewardship-oriented culture.

Intrinsic Motivation

Stewardship theory assumes that individuals are intrinsically motivated to work on behalf of the organization. According to Deci (Reference Deci1972), intrinsically motivated individuals perform tasks for no tangible rewards but the activity itself. In fact, they perform an activity because they find it interesting and enjoyable. Research on volunteering has shown that intrinsic motivation stimulates volunteer work effort (van Schie et al. Reference Van Schie, Güntert, Oostlander and Wehner2015). Beyond that, individuals volunteer due to personal interest rather than external pressure irrespective of organizational affiliation (Bidee et al. Reference Bidee, Vantilborgh, Pepermans, Huybrechts, Willems, Jegers and Hofmans2013). Despite the comparatively high time demand of volunteer activity, volunteer firefighters, in particular, are characterized as being highly intrinsically motivated (Tõnurist and Surva Reference Tõnurist and Surva2017).

This study assumes that intrinsic motivation strengthens the positive association between PSM and extra-role behavior. This can be explained by referring to research on self-determination: According to Ryan and Connell (Reference Ryan and Connell1989), prosocial behavior can be understood by the outcomes of identification. Correspondingly, prosocial motivation is characterized by identified regulation when intrinsic motivation is high. Individuals who enjoy their work and value the outcomes of helping others perceive the work as beneficial to their own self-selected goals (Gagné and Deci Reference Gagné and Deci2005; Grant Reference Grant2008). Self-determination thus suggests that individuals with intrinsic motivation feel volition, autonomy, and free choice in their efforts to benefit others and thus perceive prosocial motivation as identified regulation (Ryan and Connell Reference Ryan and Connell1989). When intrinsic motivation is high, individuals with prosocial motivation increasingly expend efforts to provide an important outcome goal, such as extra-role behavior, for employees to pursue (Gagné and Deci Reference Gagné and Deci2005). In contrast, employees do not enjoy working when intrinsic motivation is low but feel pressured when performing extra-role behaviors. In this case, prosocial motivation is characterized as introjected regulation (Ryan and Connell Reference Ryan and Connell1989). Self-determination theory assumes that individuals are motivated by the fulfillment of their basic psychological needs for autonomy (Ryan and Deci Reference Ryan and Deci2000). If they feel pressured to work extra hours, they may reduce their level of engagement (Bazerman et al. Reference Bazerman, Tenbrunsel and Wade-Benzoni1998) to regain their sense of autonomy at the expense of organizational performance (Grant Reference Grant2008).

Grant (Reference Grant2008) tested whether intrinsic motivation moderates the effect of prosocial motivation on the persistence of firefighters and found that those with high levels of both prosocial and intrinsic motivations worked an average of more than 30 overtime hours per week, whereas those with low levels worked approximately 20 overtime hours per week on average. In this study, we hypothesize that intrinsic motivation moderates the relationship between PSM and extra-role behavior.

Hypothesis 2a

Intrinsic motivation moderates the relationship between PSM and extra-role behavior.

Job Characteristics

Stewards’ worker motivation is further stimulated by the opportunity for growth and employees’ responsibility (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997). Thus, an influence of job characteristics is assumed. Hackman and Oldham (Reference Hackman and Oldham1976) argue that the attainment of three psychological states (i.e., experienced meaningfulness of work, experienced responsibility for outcomes, and knowledge of actual results) fosters positive personal and work outcomes. Accordingly, jobs must enhance skill variety (i.e., the extent to which an individual must use different skills to perform his or her job), task identity (i.e., the extent to which an individual can complete a whole piece of work), task significance (i.e., the extent to which a job impacts others’ lives), autonomy (i.e., the freedom an individual has in performing work), and feedback from the job (i.e., the extent to which a jobs imparts information about an individual’s performance) to increase the opportunity for growth and worker responsibility (Hackman and Oldham Reference Hackman and Oldham1976). These job characteristics consequently increase an individual’s work meaningfulness because the individual feels useful and valuable (Humphrey et al. Reference Humphrey, Nahrgang and Morgeson2007). Research has linked these work characteristics with positive behavioral (e.g., job performance) and attitudinal outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction) (Fried and Ferris Reference Fried and Ferris1987). For example, job design is negatively related to turnover intentions from a voluntary organization and positively linked to time spent volunteering (Alfes et al. Reference Alfes, Shantz and Saksida2015). Furthermore, well-designed volunteer tasks serve as motivational stimuli for volunteer engagement and organizational citizenship behavior (van Schie et al. Reference Van Schie, Güntert, Oostlander and Wehner2015).

Similar to the causal mechanisms of the relationship between intrinsic motivation and extra-role behavior, this study hypothesizes that job characteristics moderate the relationship between PSM and extra-role behavior. Individuals with a strong desire to help society might be more willing to work extra hours if they evaluate their job positively in terms of the opportunity for growth and responsibility. PSM is thus expected to have a stronger effect on extra-role behavior when employees perceive a motivating work design.

Hypothesis 2b

Job characteristics that correspond with a motivating work design (i.e., autonomy, task significance, task identity, variety, and feedback) moderate the relationship between PSM and extra-role behavior.

Organizational Identification

Stewardship theory focuses on the psychological linkage between individuals and organizations. Correspondingly, stewards characterize themselves as members of their organization and consider organizational goals and mission as their own (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997). Organizational identification is defined as “a perceived oneness with an organization and the experience of the organization’s successes and failures as one’s own” (Mael and Ashforth Reference Mael and Ashforth1992, 103). Identification makes the organization an extension of the steward’s psychological structure and may determine individuals’ performance, spontaneous contribution, or related outcomes (Brown Reference Brown1969; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997). Identifying individuals (e.g., employees) experience negative comments about the organization personally and claim credit for organizational successes (e.g., Katz and Kahn Reference Katz and Kahn1978). They thereby increase their self-image and self-concept (Kelman Reference Kelman1961; Sussman and Vecchio Reference Sussman and Vecchio1982), which corresponds with the stewardship model (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997). Individuals who identify with an organization seek to increase organizational success and thus help to solve problems and overcome barriers.

In this study, we assume that organizational identification strengthens the positive association of PSM and extra-role behavior. Individuals who strongly identify with their organizations have positive feelings about their membership and perceive organizational life as their own business (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austrin and Worchel1979). Research on volunteering (Scott and Stephens Reference Scott and Stephens2009; Meisenbach and Kramer Reference Meisenbach and Kramer2014; Mayr Reference Mayr2017) and organizational citizenship behavior (van Dick et al. Reference Van Dick, Grojean, Christ and Wieseke2006) confirms this notion by indicating that individuals’ sense of oneness with an organization fosters their willingness to volunteer and help other members of the organization. Identifying organizational members might interpret extra-role behaviors positively and thus may be more willing to engage in extra work, whereby PSM is a channel to expected extra-role behavior. Organizational identification can also stimulate supportive attitudes or even “self-sacrifice” to the organization (Mael and Ashforth Reference Mael and Ashforth1992; Pratt Reference Pratt, Whetten and Godfrey1998). Accordingly, individuals who perceive organizational identification such as trust, praise, or regard are more likely to contribute to organizational performance (e.g., Van Dick et al. Reference Van Dick, Grojean, Christ and Wieseke2006). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 2c

Organizational identification moderates the relationship between PSM and extra-role behavior.

Commitment

Commitment is a characteristic of stewards that makes them believe in and accept organizational goals (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997; Mayer and Schoorman Reference Mayer and Schoorman1992). Whereas identification reflects psychological oneness, commitment is contingent on social exchange processes and refers to the relationship between separate psychological entities (Van Knippenberg and Sleebos Reference Van Knippenberg and Sleebos2006). Meyer and Allen (Reference Meyer and Allen1991) define commitment as an affective attachment to the organization, a perceived cost associated with leaving the organization, and an obligation to remain in the organization. Individuals with high levels of value commitment align with the organization, share the organization’s vision, values, and mission, and are ready to spend time and effort to improve the organization’s success (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997). Similarly, Lee and Olshfski (Reference Lee and Olshfski2002) have shown that firefighters’ commitment to the job is linked to extra-role behavior.

This study assumes a moderating effect of commitment on the positive association between PSM and extra-role behavior. Accordingly, it is suggested that a culture of high commitment has a positive effect on the association of PSM and extra-role behavior. Eddleston et al. (Reference Eddleston, Kellermanns and Sarathy2008) found that high levels of commitment to a firm can increase prosocial and pro-organizational helping behavior. Commitment represents a collectivistic motivator (Kollock Reference Kollock, Smith and Kollock1999) and thus is strongly related to work effort and the motivation to contribute additional work in the interest of the collective (Meyer and Allen Reference Meyer and Allen1997; Riketta Reference Riketta2002). For example, Mowday et al. (Reference Mowday, Porter and Steers1982, 27) state that those who are committed to an organization “are willing to give something of themselves in order to contribute to the organization’s well-being.” We thus suggest that commitment strengthens the relationship between PSM and extra-role behavior. This leads us to formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2d

Commitment moderates the relationship between PSM and extra-role behavior.

Perceived Organizational Support

Stewardship cultures are described as collectivist and with high levels of group cohesion, which is captured by organizational support. Perceived organizational support refers to employees’ beliefs concerning the extent to which an organization’s management values their contributions and cares about their well-being (Eisenberger et al. Reference Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison and Sowa1986; Rhoades et al. Reference Rhoades, Eisenberger and Armeli2001). Supportive organizations look after their employees, treat them fairly, and “‘[go] beyond the call of duty’ to benefit a worker” (Randall et al. Reference Randall, Cropanzano, Bormann and Birjulin1999, 169).

Perceived organizational support is linked to positive organizational outcomes, such as job involvement or positive mood at work (Rhoades and Eisenberger Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002). Furthermore, employees who perceive organizational support are more ready to perform citizenship behavior (Randall et al. Reference Randall, Cropanzano, Bormann and Birjulin1999; Rhoades and Eisenberger Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002). This phenomenon may be explained by job satisfaction relating to high levels of organizational support (Shore and Tetrick Reference Shore and Tetrick1991; Cropanzano et al. Reference Cropanzano, Howes, Grandey and Toth1997) or by the norm of reciprocity (Settoon et al. Reference Settoon, Bennett and Liden1996). According to the social exchange perspective (Blau Reference Blau1964; Cropanzano and Mitchell Reference Cropanzano and Mitchell2005), individuals respond to a beneficial action by returning a benefit and to a harmful action by returning harm. Consequently, it can be argued that employees who receive support from an organization perform more extra work than those who do not perceive organizational support. Organizational support may be particularly relevant to maintaining and boosting levels of self-esteem and fulfilling the need for social companionship and affiliation (Cohen and Wills Reference Cohen and Wills1985). This heightens individual willingness to spend more time in the organization and perform extra work. Research on volunteering confirms these assumptions. Accordingly, volunteers who perceive organizational support are more satisfied, more likely to remain in the volunteer organization (Walker et al. Reference Walker, Accadia and Costa2016), and spend more effort in accomplishing tasks (Cady et al. Reference Cady, Brodke, Kim and Shoup2018). Consequently, we expect organizational support to moderate the relationship between PSM and extra-role behavior and hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 2e

Perceived organizational support moderates the relationship between PSM and extra-role behavior.

Research Setting

The geographical distribution of fire services in Austria and Germany has its origin in the Prussian system. Given the similar historical roots in both countries, the principle of subsidiarity has characterized the allocation of responsibilities in terms of emergency services and has led to a local structure of fire services in both federal states. Even today, fire service is executed at the municipal level in both countries so that each city has at least one fire department (or even several) (Wolter Reference Wolter2011). In Austria, more than 4496 fire departments are located in 2098 municipalities (Austrian Society of Federal Fire Service 2017). In Germany, the number of fire stations also exceeds the number of municipalities: 11,084 municipalities own 22,795 fire departments (German Federal Fire Service 2016). Nearly all of these fire stations are staffed by volunteer firefighters. Only six fire stations in Austria and only 105 in Germany are professional ones. These stations are generally located in large cities with typically more than 100,000 inhabitants and staffed with paid workers (civil servants). Accordingly, 99% of firefighters in Austria and 94% of firefighters in Germany are volunteers (Austrian Society of Federal Fire Service 2017; German Federal Fire Service 2016). This is a comparatively high percentage in relation to other European countries (Zeilmayr Reference Zeilmayr and Rönnfeldt2003; Hilgers Reference Hilgers2008).

Consequently, volunteer firefighters are essential to ensure safety in Austria and Germany. Their duties are summarized in the principle “save–quench–rescue–protect.” In more detail, the core tasks are to save the lives of humans and animals, quench flames, rescue from accidents and protect from dangers such as high watermarks or after heavy thunderstorms. In addition to these core tasks, which are mandated by law, there are many additional activities firefighters can volunteer for. Seven additional activities can be distinguished and described as follows:

(1) Volunteer firefighters train and educate themselves. They organize basic education courses and are responsible for their own transfer of knowledge within the staff and between organizations. (2) Consequently, by organizing basic courses, volunteer firefighters care for the promotion of young fellows and new members. (3) Furthermore, volunteer firefighters are often members of firefighting associations and roundtables to develop, for example, technical or educational standards or emergency plans.

Local volunteer fire services are faced with a high degree of financial autonomy, meaning that in addition to basic funding for housing, vehicles and machinery from public budgets (taxes), additional funding can be obtained for better equipment, training, excursions, and social events that promote fellowship and team cohesion. The latter is an important issue regarding the social structure of the municipal community, where fire services offer group activities and social employment, especially for young people, and contribute by, for example, organizing village festivals. Consequently, volunteer firefighters often work voluntarily as, for example, (4) event managers for their unit or (5) cashiers responsible for accounting, procurement and spending or funding activities or (6) in administrative issues. (7) Finally, volunteer firefighters are often engaged in technical issues of the maintenance of complex machinery (e.g., fire ladder trucks or care for fire prevention issues), such as by giving basic courses for children in schools and kindergartens.Footnote 1 In other countries or in professional fire stations with paid staff in Germany and Austria, some of these duties are performed by administrative staff, outsourced to private companies or performed by non-firefighter-related staff (e.g., maintenance of machinery or education). In the Prusso-German administrative system, however, these activities are assigned to the firefighting realm and performed by volunteer firefighters.

By referring to the literature (Katz Reference Katz1964; Van Dyne and LePine Reference Van Dyne and LePine1998; Somech and Drach-Zahavy Reference Somech and Drach-Zahavy2000; Turnipseed and Rassuli Reference Turnipseed and Rassuli2005), this study defines extra-role behavior as those behaviors performed by individuals that go beyond specified role requirements and directly or indirectly benefit organizational goals and society, whereas in-role behavior is characterized as tasks in accordance with formally described roles. In accordance with the theoretical framework, in-role behavior performed by volunteer firefighters in Austria and Germany encompasses the core tasks that are mandated by law. In contrast, extra-role behavior comprises the seven additional activities outlined above, as these activities are voluntary, not part of the role description or formally required, and not formally rewarded or penalized if they are not performed. Besides, these extra activities help to maintain organizational survival and enhance organizational effectiveness.

Consequently our study uses the extra-role behavior of volunteer firefighters as a dependent variable. To operationalize extra-role behavior, we conducted interviews with an expert panel on volunteer fire services and performed a document analysis of regulations and instructions for Austrian and German volunteer fire departments. In these interviews, we obtained detailed insight that the activities mentioned in (1)–(7) are characterized as occasional activities, performed by dedicated and enthusiastic but single members of the organization or fire brigade unit, establishing an informal and often a spontaneous “extra role.”

Although employees’ extra-role behavior is valuable to all organizations, it seems particularly important to voluntary organizations in emergency service, such as volunteer fire departments, for the following reasons. First, the amount of emergency inserts for volunteer firefighters has increased in the last decades. This is especially the case for very intense inserts because the sheer number of natural disasters, such as high floods or severe thunderstorms, has increased, and the need of modern society to require or ask for help in such events has risen. Second, the range of emergency scenarios has increased because, at least in Austria and Germany, fire brigades are increasingly included in new emergency deployments concerning, for example, environmental protection, the environmental measurement of air quality (e.g., when a fire burns), or chemical assistance at accidents in industrial companies. Third, people increasingly migrate into cities and consequently quit membership in rescue services in rural areas, which is a severe problem for the remaining volunteers. Fourth, demands are continuously increasing in professional life so that individuals have less time for volunteering in fire services. Resource scarcity and a decline in membership, on the one hand, and work-intensive duties, on the other hand, challenge volunteer fire departments to sustain service quality. Consequently, these organizations are likely to feel the need for valuable extra hours for organizational survival on a large scale and must ensure extra work from their volunteers.

Against the backdrop of volunteer firefighters’ tremendous social and economic value to society (McLennan et al. Reference McLennan, Birch, Cowlishaw and Hayes2009), the literature has focused on volunteer firefighters’ specific organizational culture, attitudes, motivation, and behavior. By choosing an in-depth ethnographic research design, Desmond (Reference Desmond2006) sheds light on the practical logic of firefighting rather than the “cold logic” of rationality. That study focuses on the individual firefighter, his or her feelings when facing a fire, and organizational socialization. More specifically, it describes how individuals transform into the specific habitus of firefighters as embodied by the organization. Firefighters are described as committed to their job and taking their role in the community seriously (Lee and Olshfski Reference Lee and Olshfski2002). This commitment to the job also becomes evident in their readiness to perform extraordinary efforts. In addition, firefighters’ work engagement is explained by high levels of both prosocial and intrinsic motivation (Grant Reference Grant2008). Drawing on Kahn’s concept of engagement (Reference Kahn1990), Rich et al. (Reference Rich, Lepine and Crawford2010) show that firefighters expend enormous energy in completing tasks beyond fighting fires. They attribute this engagement to individual characteristics and organizational factors. To cope with highly demanding and stressful firefighting tasks (McLennan et al. Reference McLennan, Birch, Cowlishaw and Hayes2009), social support from family and friends is found to be particularly important for volunteer firefighters (Huynh et al. Reference Huynh, Xanthopoulou and Winefield2013). Our study contributes to previous research on firefighting by explaining different extents of extra-role behavior of volunteer firefighters in Austria and Germany.

Data and Methods

Sample and Data Collection

This study applies quantitative data analysis and follows a dyadic data approach by drawing on two data sources. First, we conduct a survey among volunteer firefighters in Austria and Germany to obtain information on their motivations, attitudes, and behaviors. Second, we use data from an online platform for hydrant reporting to measure firefighters’ engagement in equipment management (i.e., the number of hydrants reported in the platform).

To test our hypotheses, we needed access to a large number of volunteer firefighters. Unfortunately, there is no publicly accessible register of volunteers, and social media does not provide access to a sufficiently high number of volunteer fire departments. Consequently, we employed an explorative search strategy to identify Austrian and German volunteer firefighters. We contacted the developer of an online platform for reporting the location of hydrants. The platform provides an online tool for printing plans of the locations of hydrants. These plans of hydrants summarize important facts about a hydrant (e.g., amount of water, pressure, maintenance interval, GPS data and pictures) and can, for example, be used for fire-fighting operations. Because fire departments lack a comprehensive overview of the location of hydrants in their area, firefighters are the primary users of the tool. They developed a map of hydrants by entering all relevant information in the platform.

At the time of data analysis, 6734 individuals in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy were using the platform to prepare plans for hydrants. The contact addresses obtained from the platform provided access to individuals from several countries and allowed us to study different extents of extra-role behavior. We sent a mailed invitation to participate in a survey on firefighting to all registered users. Before the questionnaire was sent, it was pilot tested and revised accordingly. Unfortunately, 203 pieces of mail were undeliverable. Two reminders were sent, yielding 548 complete questionnaires and a response rate of 8.4%.Footnote 2

This study focuses on firefighters working in a volunteer fire department (96.51% of respondents) situated in Austria and Germany (98.67% of respondents). After excluding those firefighters who received pay for their work at the fire service and those working in countries other than Austria and Germany, the sample consisted of 519 firefighters. A total of 58.77% of the sample respondents were Austrians, and 41.23% were from Germany. Due to missing data, the final sample size for the regression analysis was 475. To our knowledge, this is the greatest sample of volunteer firefighters in this context studied to date.Footnote 3

Measures

Dependent Variable

The scale for extra-role behavior reflected volunteers’ statements regarding how often they engage in activities of training, the promotion of young fellows, advocacy, event management, financial management, administration, and equipment management. As outlined in the previous section, these activities captured tasks that are not part of the role description of a volunteer firefighter. Extra-role behavior was measured by asking survey participants to what extent they engaged in these seven activities. The first six items were measured on a 5-point scale from “1” indicating “never” to “5” indicating “always”. Equipment management was measured by the number of hydrants reported by the online platform.

Independent and Moderating Variables

The independent, moderating, and control variables were measured by survey data. Unless otherwise indicated, all items used 7-point Likert-type scales with anchors of 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly). If the measures included multiple items, the item scores were averaged. A full list of variables and measurements can be found in “Appendix”.

Public service motivation was measured using a short version of Perry’s (Reference Perry1996) PSM scale. German items were drawn from Hammerschmid et al. (Reference Hammerschmid, Meyer and Egger-Peitler2009). To measure intrinsic motivation, survey participants were asked, “Why are you motivated to engage in the fire service?” Motivation items were drawn from Gagné et al. (Reference Gagné2015) and adapted to the context of fire service. Job characteristics were measured by a 5-item scale adapted from Hackman and Oldham (Reference Hackman and Oldham1974). The item on skill variety was excluded from the scale on job characteristics because the factor loading was below .5. Organizational identification was measured by six items adapted from Mael and Ashforth (Reference Mael and Ashforth1992), using fire departments instead of schools. Items to measure commitment were adapted from Meyer et al. (Reference Meyer, Allen and Smith1993), resulting in a 6-item scale after the factor loadings were checked. Perceived organizational support was measured by an adapted multi-item scale developed by Eisenberger et al. (Reference Eisenberger, Cummings, Armeli and Lynch1997).

Control Variables

Based on a review of the literature, we identified six variables that could covary with our independent and dependent variables and thus could be controlled for in our analysis. The variable country controlled for cultural differences between Austria and Germany by taking Austria as a reference. To control for the education of the respondents, we asked for the highest level of completed education (1 = compulsory school (low education level); 2 = secondary school (intermediate); 3 = university degree (high)). The study controlled for the respondents’ physical ability by taking respondents’ age as a proxy, measured by the year of birth (categorical, young = 1986–2000; intermediate = 1971–1985; old = 1920–1970). Tenure was measured by the duration of membership as a firefighter (categorical, 10 years and less = 1, 11–20 years = 2, 21–30 years = 3, 31–40 years = 4, 41–50 years = 5). Respondents’ workload or time restrictions were measured by the number of operations (more than 30 operations per year = 1). Satisfaction with supervision controlled for firefighters’ satisfaction with their supervisor and was measured by the subscale on supervision of the Job Descriptive Index developed by Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Kendall and Hulin1969).

Results and Discussion

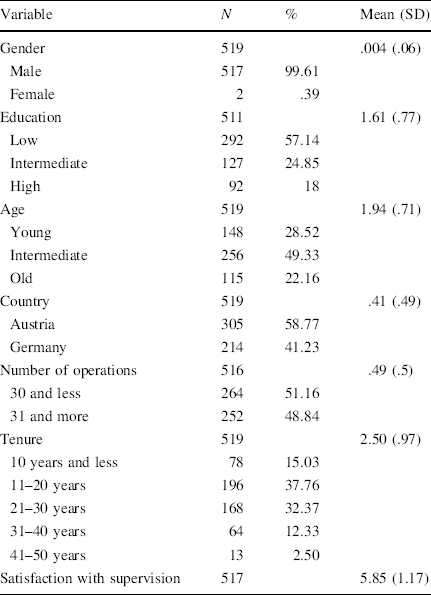

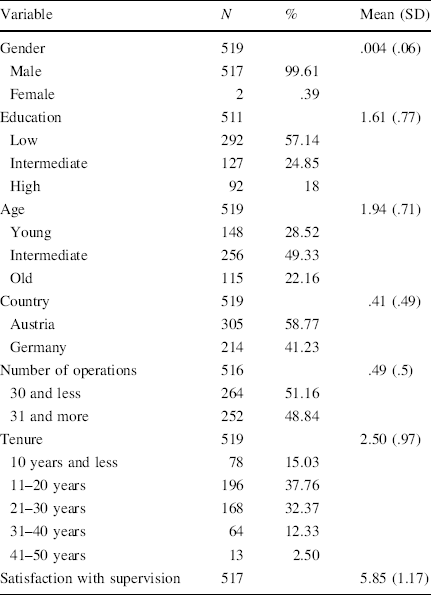

Table 1 presents an overview of the sample’s descriptives. A total of 99.61% of respondents were male, approximately 50% were aged between 31 and 45, and approximately 57% were low educated. Approximately 15% of respondents had worked as a volunteer firefighter for 10 years or less. The majority of respondents (approximately 38%) had been serving for between 11 and 20 years.

Table 1 Sample descriptives

Variable |

N |

% |

Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

Gender |

519 |

.004 (.06) |

|

Male |

517 |

99.61 |

|

Female |

2 |

.39 |

|

Education |

511 |

1.61 (.77) |

|

Low |

292 |

57.14 |

|

Intermediate |

127 |

24.85 |

|

High |

92 |

18 |

|

Age |

519 |

1.94 (.71) |

|

Young |

148 |

28.52 |

|

Intermediate |

256 |

49.33 |

|

Old |

115 |

22.16 |

|

Country |

519 |

.41 (.49) |

|

Austria |

305 |

58.77 |

|

Germany |

214 |

41.23 |

|

Number of operations |

516 |

.49 (.5) |

|

30 and less |

264 |

51.16 |

|

31 and more |

252 |

48.84 |

|

Tenure |

519 |

2.50 (.97) |

|

10 years and less |

78 |

15.03 |

|

11–20 years |

196 |

37.76 |

|

21–30 years |

168 |

32.37 |

|

31–40 years |

64 |

12.33 |

|

41–50 years |

13 |

2.50 |

|

Satisfaction with supervision |

517 |

5.85 (1.17) |

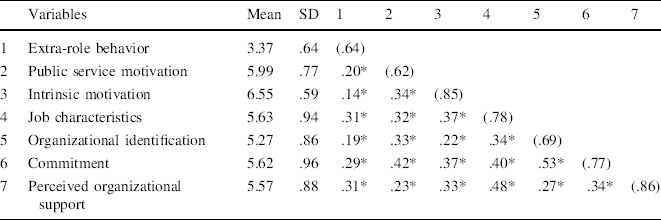

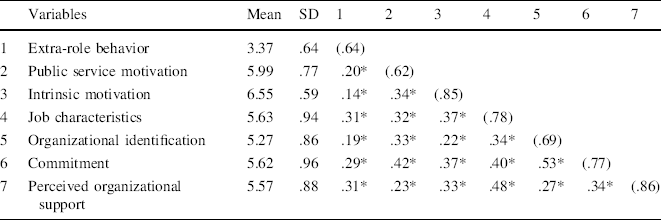

Table 2 reports the scale means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients along with the Cronbach’s alpha. The multi-item measures report alpha coefficients ranging between .62 and .88. The correlations among the variables were in the predicted directions and consistent with theoretical expectations. These correlations were moderate, with few intercorrelations approaching or exceeding .40.

Table 2 Means, standard deviations, and correlations (Cronbach’s alphas in parentheses)

Variables |

Mean |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Extra-role behavior |

3.37 |

.64 |

(.64) |

||||||

2 |

Public service motivation |

5.99 |

.77 |

.20* |

(.62) |

|||||

3 |

Intrinsic motivation |

6.55 |

.59 |

.14* |

.34* |

(.85) |

||||

4 |

Job characteristics |

5.63 |

.94 |

.31* |

.32* |

.37* |

(.78) |

|||

5 |

Organizational identification |

5.27 |

.86 |

.19* |

.33* |

.22* |

.34* |

(.69) |

||

6 |

Commitment |

5.62 |

.96 |

.29* |

.42* |

.37* |

.40* |

.53* |

(.77) |

|

7 |

Perceived organizational support |

5.57 |

.88 |

.31* |

.23* |

.33* |

.48* |

.27* |

.34* |

(.86) |

The significance levels are indicated as follows: *p < 0.05

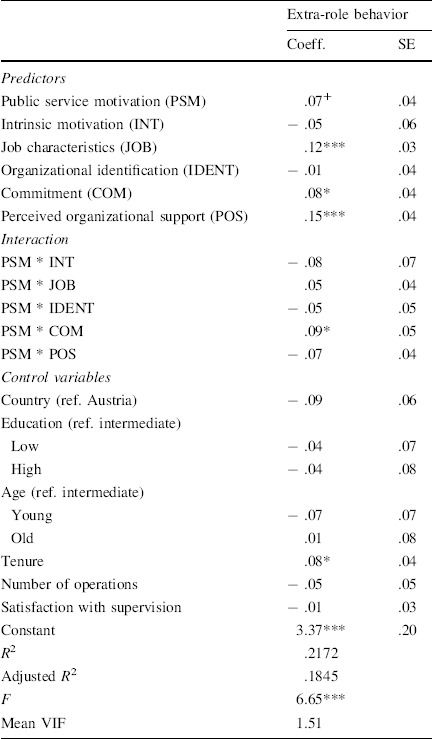

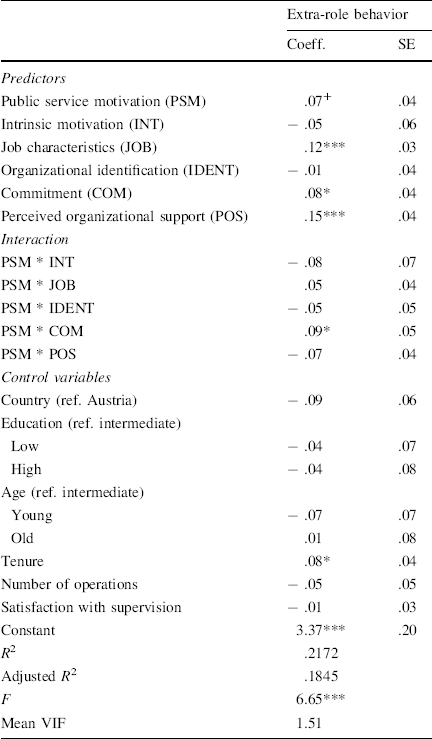

To test the research model, moderated regression analysis was conducted. Continuous predictor variables were mean-centered to reduce the occurrence of multicollinearity in the moderating analysis, and product terms were calculated to test the moderating effects. To account for any possible issues with multicollinearity in the data, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was assessed to verify the validity and reliability of our empirical approach. Multicollinearity tests dismissed the potential for problems because the mean variance inflation factor did not exceed 1.51, which is below the typical cutoff of 10 (see Table 3).

Table 3 Regression for extra-role behavior

Extra-role behavior |

||

|---|---|---|

Coeff. |

SE |

|

Predictors |

||

Public service motivation (PSM) |

.07+ |

.04 |

Intrinsic motivation (INT) |

− .05 |

.06 |

Job characteristics (JOB) |

.12*** |

.03 |

Organizational identification (IDENT) |

− .01 |

.04 |

Commitment (COM) |

.08* |

.04 |

Perceived organizational support (POS) |

.15*** |

.04 |

Interaction |

||

PSM * INT |

− .08 |

.07 |

PSM * JOB |

.05 |

.04 |

PSM * IDENT |

− .05 |

.05 |

PSM * COM |

.09* |

.05 |

PSM * POS |

− .07 |

.04 |

Control variables |

||

Country (ref. Austria) |

− .09 |

.06 |

Education (ref. intermediate) |

||

Low |

− .04 |

.07 |

High |

− .04 |

.08 |

Age (ref. intermediate) |

||

Young |

− .07 |

.07 |

Old |

.01 |

.08 |

Tenure |

.08* |

.04 |

Number of operations |

− .05 |

.05 |

Satisfaction with supervision |

− .01 |

.03 |

Constant |

3.37*** |

.20 |

R 2 |

.2172 |

|

Adjusted R 2 |

.1845 |

|

F |

6.65*** |

|

Mean VIF |

1.51 |

|

Linear regression; N = 475; the significance levels are indicated as follows: +p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Table 3 summarizes the results of the regression analysis. The model is statistically significant, and the independent variables, interaction terms, and controls explain 18.45% of the variation in the dependent variable. Regarding the control variables, the findings indicate no significant effect of citizenship, socio-demographic characteristics, time constraints, or satisfaction with supervision on extra-role behavior. However, tenure is significantly associated with extra-role behavior. This means that individuals with more years spent as firefighters show a higher level of extra-role behavior than their colleagues with lower tenure.

This finding may be explained by individuals’ internalization of additional tasks and duties. Job tenure may lead to different perceptions of what employees define as in-role and extra-role behavior (Morrison Reference Morrison1994). Firefighters who have worked for several years may feel an obligation to perform extra work due to higher levels of trust and organizational commitment. Furthermore, tenure is related to gaining experience. Thus, firefighters become more knowledgeable over time and cognitively relate more tasks to their individual activities.

Our first hypothesis examines the direct effect of PSM on extra-role behavior. The findings support this hypothesis by indicating a significant, positive influence of PSM at the 10% significance level. Firefighters with high levels of PSM perform higher levels of extra-role behavior. This result also supports previous studies testing the effect of PSM on citizenship behavior (Pandey et al. Reference Pandey, Wright and Moynihan2008) and prosocial behavior (Esteve et al. Reference Esteve, Urbig, Van Witteloostuijn and Boyne2016). Accordingly, PSM seems to be advantageous for the organization because employees with altruistic beliefs spend more time performing extra work. However, the result has to be interpreted with caution due to the low significance level.

With regard to interaction terms, the findings indicate a positive effect of PSM*COM on extra-role behavior. Consequently, the findings support Hypothesis 2d on the moderating effect of commitment. Individuals with high PSM show a higher level of extra-role behavior if they are committed to the organization and their tasks. This result indicates that individuals who expend extra-role effort are committed not only to the public interest but also to the fire department and their work. Although there is a direct effect of PSM on extra-role behavior, the interaction effect is stronger and more significant. The analysis provides no support for Hypotheses 2a, 2b, 2c, and 2e.

In addition to the moderating effect of stewardship-like factors, several direct effects significantly relate to extra-role behavior. Accordingly, job characteristics have a significant, positive effect on extra-role behavior, a result in line with previous research on volunteering (Alfes et al. Reference Alfes, Shantz and Saksida2015; van Schie et al. Reference Van Schie, Güntert, Oostlander and Wehner2015). Furthermore, commitment positively relates to firefighters’ engagement in extra work. Finally, similar to past research (Cady et al. Reference Cady, Brodke, Kim and Shoup2018), perceived organizational support has a positive association with extra-role behavior. These results indicate that some aspects of a stewardship-oriented work and organizational context influence individual workers’ performance.

Whereas a motivating work design, commitment, and perceived organizational support directly influence the level of extra-role behavior of volunteer firefighters, organizational identification and intrinsic motivation do not predict extra-role performance. The latter finding contradicts the results from Grant (Reference Grant2008), which showed that intrinsic motivation strengthens the relationship between prosocial motivation and performance. In this study, intrinsic motivation is not directly related to extra-role behavior, and the joint effect with PSM is not significant. Although other studies have shown that intrinsic motivation predicts volunteer behavior, it may not provide an explanation for behavior that exceeds role prescriptions (see Schaubroeck and Ganster Reference Schaubroeck and Ganster1991). The insignificant results might be explained by the variety and complexity of the work (Grant Reference Grant2008). Previous research has shown that completing varied and complex tasks stimulates intrinsic motivation, whereas repetitive tasks that are perceived as simple are less likely to be promoted with intrinsic motivation (Hackman and Oldham Reference Hackman and Oldham1976; Koestner and Losier Reference Koestner, Losier, Deci and Ryan2002).

Conclusion

Theoretical Implications

This paper aimed to examine the effect of individual attitudes, motivation, and perceptions of organizational culture on extra-role behavior. Many volunteer firefighters not only engage in emergency services (i.e., responding to calls for help) but also spend their time going above and beyond the call of duty and engaging in extra work that is advantageous to the fire department and, ultimately, for society. These extra-role behaviors are an important form of organizational behavior that affects organizational performance and survival. In this study, we examined how individual inner conviction and the organizational context matter in terms of individual performance. In terms of rescue and firefighting services, social cohesion seems particularly important. This study showed that firefighters perform their duties not only due to concern for serving the public interest but also because of attachment to the organization, companionship, and firefighting activities.

While the determinants of volunteer behavior have been well established, our goal was to broaden our understanding of extra-role behavior in the voluntary context. This study thus contributes to research on volunteer behavior by focusing on a very specific but crucial behavior. It adds to the existing literature by investigating behaviors that go beyond role prescriptions and that are inevitable for organizational success and effectiveness. In doing so, we examined both the simultaneous and joint effects of PSM and factors associated with stewardship on individual performance. Overall, our findings suggest that PSM has a positive effect on volunteer extra-role behavior. Furthermore, firefighters’ attachment to the organization and fellow relationships can be a source of performance advantage for fire departments. In the following, the contributions of the findings to theory are discussed.

Our finding regarding the positive effect of PSM on individual willingness to work extra hours contributes to the literature on PSM by shedding light on the outcomes of altruistic motivation. Bozeman and Su (Reference Bozeman and Su2015) questioned whether and how PSM corresponds to observable behavior, and various other studies have called for research on this issue (Brewer Reference Brewer, Perry and Hondeghem2008; Ritz Reference Ritz2009). We show that PSM influences individual volunteer behavior in that PSM-motivated volunteers are more willing to perform extra work compared with those who show lower levels of PSM. Although the effect is only significant at a 10% level and thus should be interpreted with caution, we can conclude that individuals with high PSM tend to perform higher levels of extra-role behavior. This study contributes to research on the effect of PSM on organizational behavior (e.g., Kim Reference Kim2006; Pandey et al. Reference Pandey, Wright and Moynihan2008; Ritz Reference Ritz2009) in the specific context of voluntary emergency service. Few studies have tested whether PSM can explain volunteer behavior (Coursey et al. Reference Coursey, Brudney, Littlepage and Perry2011; Ertas Reference Ertas2014; Leisink et al. Reference Leisink, Knies and van Loon2018). We contribute to these studies by showing that PSM might be linked to behavior that goes above and beyond the call of duty.

In addition to testing whether PSM influences behavior, this study investigated how PSM relates to extra-role work. We predicted and found support for our claim that individual commitment to the occupation and organization influences the relationship between PSM and extra-role behavior. Whereas extra-role behavior can be explained by an individual inner conviction to serve the public interest, individuals seem to spend even more time and effort on extra-role behavior if they are committed to both the public interest and their job and fire department. Consequently, volunteer firefighters who perform high levels of extra-role behavior have a strong desire to foster the well-being of society and are highly committed to their job and fire department.

Finally, our findings regarding the effect of some aspects of a stewardship-like culture on extra-role behavior contribute to research on stewardship theory. We contribute to the stream of literature of qualitative studies that explore stewardship in organizations by quantitatively testing the effect of stewardship on volunteer performance. We provide support for the notion that the extra-role behavior of volunteers can be stimulated by several characteristics of a stewardship culture. In line with our findings, volunteerism seems to be a cultural rather than a managerial issue. Accordingly, extra work cannot be instructed but rather is an issue of self-actualization based on motivating work, emotional attachment to the organization, and group cohesiveness. Firefighters who perceive their tasks as meaningful and valuable are willing to spend more time in the fire department and help to maintain equipment, support organizing events, and take care of financial management. In addition to positive attitudes toward tasks, commitment to the occupation and organization positively influences their willingness to perform extra work. Finally, extra-role behavior is not isolated from social relationships, but rather support from fellowship has a direct effect on the frequency of extra-work engagement.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Given the importance of extra-role behavior for many outcomes, our findings suggest multiple avenues for future studies that consider how organizations can improve the prosocial organizational behavior of their employees. Although we address several limitations of this research, we are convinced of our study’s potential to provide an impetus for further research on the antecedents of extra-role behaviors.

First, our study tested hypotheses in the context of Austrian and German voluntary emergency services. In spite of the effort to recruit a great number of volunteer firefighters in both countries in an explorative manner, we cannot ensure the representativeness of the sample with respect to Austrian and German volunteer firefighters due to a lack of statistical data for comparison. In making a first step toward recruiting a great share of volunteers to test our hypotheses, there are several directions for further research supporting the generalizability of our results. We call for further research that attempts to replicate our results in other field settings because the focus on volunteers in fire service with specific demographic characteristics (i.e., predominately male) might raise questions about generalizability with respect to other volunteer services. Furthermore, national regulations influence volunteer management practices. This study focuses on volunteer fire departments in Austria and Germany, and the findings might differ across countries due to differences in national law, culture, and community capacity (Haß and Serrano-Velarde Reference Haß and Serrano-Velarde2015; Henderson and Sowa Reference Henderson and Sowa2018). Studying extra-role behavior through the lens of institutional theory might be a fascinating area for future research.

Second, this study used cross-sectional data to test theoretical assumptions about the effect of PSM on extra-role behavior. However, Perry et al. (Reference Perry, Brudney, Coursey and Littlepage2008) argue that volunteering can generate PSM. Replicating this research by taking a longitudinal approach might be an intriguing area for future research and would allow us to comment on the direction of causality.

Third, this study measured the extent to which volunteers engage in extra work. Although the frequency of engagement is a first step to describe the extra-role behavior of volunteers, another important avenue for future research would be to extend the model by including outcome variables to draw conclusions about the consequences of extra-role behavior for organizational success and effectiveness. Accordingly, it could be asked to what extent extra-role behavior performed by volunteers is beneficial for individual employees (e.g., job satisfaction, motivation, individual performance, and team spirit), the organization (e.g., mobilization of new members, organizational survival, and organizational performance), and society at a large (e.g., trust in fire service, sense of security).

Despite the various positive connotations of extra-role behavior (Podsakoff et al. Reference Podsakoff, Whiting, Podsakoff and Blume2009), past research has also focused on the negative side of citizenship behavior. Employees might feel pressured to continuously work extra hours, which can result in stress and work overload (Bolino et al. Reference Bolino, Turnley and Niehoff2004; Bolino and Turnley Reference Bolino and Turnley2005; Vigoda-Gadot Reference Vigoda-Gadot2006). Furthermore, employees’ task performance has consequences on other employees’ feelings of pressure to work more even if they are unable to do so. Consequently, organizationally induced obligations to work extra hours can also be negatively associated with employee well-being (Bolino et al. Reference Bolino, Klotz, Turnley and Harvey2013; Huynh et al. Reference Huynh, Xanthopoulou and Winefield2013; Deery et al. Reference Deery, Rayton, Walsh and Kinnie2017). In addition to studying factors that stimulate extra-role behavior, we recommend that future research could examine the consequences of helping behavior on individual employees and the power of organizations to request extra-role performance (Fleming and Spicer Reference Fleming and Spicer2014).

Practical Implications

This study’s findings have important practical implications. First, high levels of PSM seem to have a positive influence on extra-role behavior, though the effect is only significant at the 10% level. Research recommends various strategies for increasing PSM by integrating public service values into an organization’s management systems (Paarlberg et al. Reference Paarlberg, Perry, Hondeghem, Perry and Hondeghem2008). These strategies could be considered by fire departments to improve performance. Second, various aspects of a stewardship culture positively relate to the extra work of volunteers. Individuals who feel that they are part of a supportive work environment and who perceive group cohesiveness reciprocate this behavior to their colleagues and the organization. Although extra-role performance does not seem to be a managerial issue in the voluntary realm, managers of voluntary organizations may draw on these findings and shape volunteer behaviors. Traditional human resources practices might be ill suited to influence employee behavior in the volunteer and nonprofit context because they are based on control systems and economic responses to manage employee behavior. However, concepts of transformational leadership (Paarlberg and Lavigna Reference Paarlberg and Lavigna2010; Dwyer et al. Reference Dwyer, Bono, Snyder, Nov and Berson2013; Mayr Reference Mayr2017) focus on higher ideals and moral values (Shamir, House, and Arthur Reference Shamir, House and Arthur1993; Tracey and Hinkin Reference Tracey and Hinkin1998). Transformational leaders are advised to give meaning to jobs by communicating the importance of their work and relating work activities to organizational aims and employees’ values (Paarlberg and Lavigna Reference Paarlberg and Lavigna2010), empowering employees (Park and Rainey Reference Park and Rainey2008), and acting as a prosocial role model (Shamir et al. Reference Shamir, House and Arthur1993).

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Johannes Kepler University Linz.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

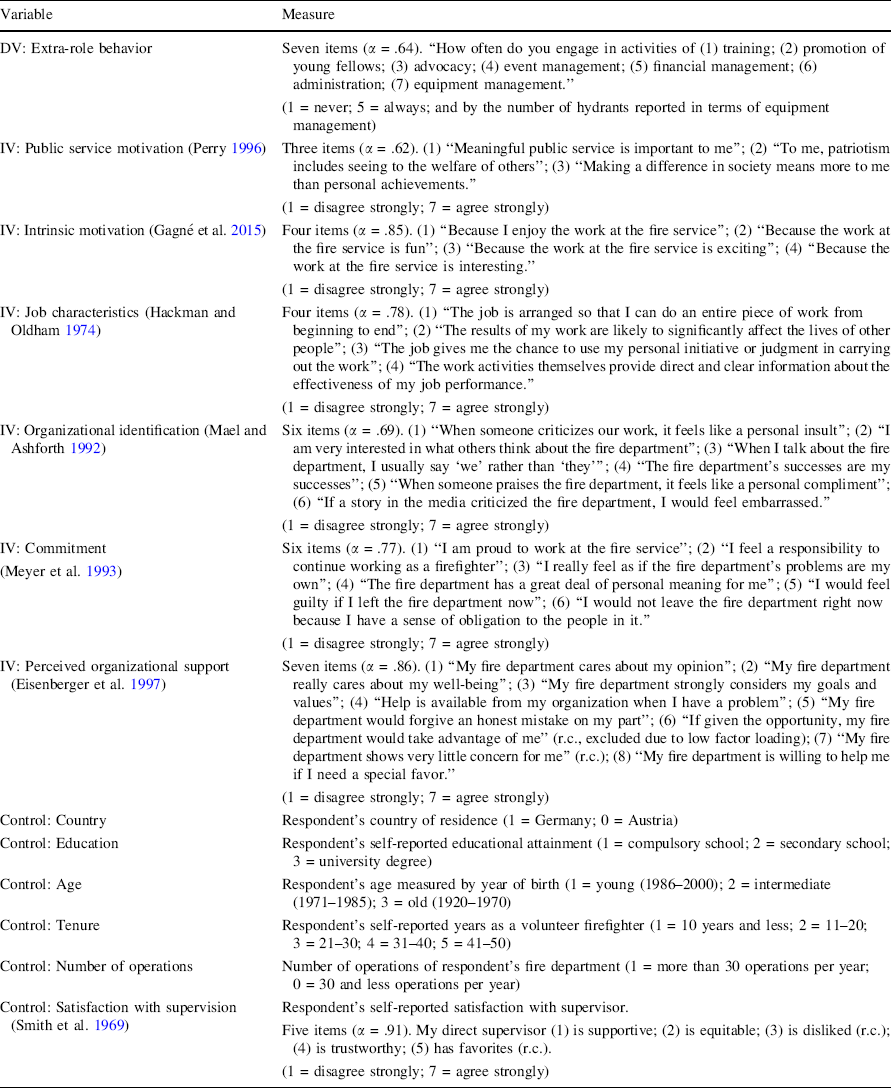

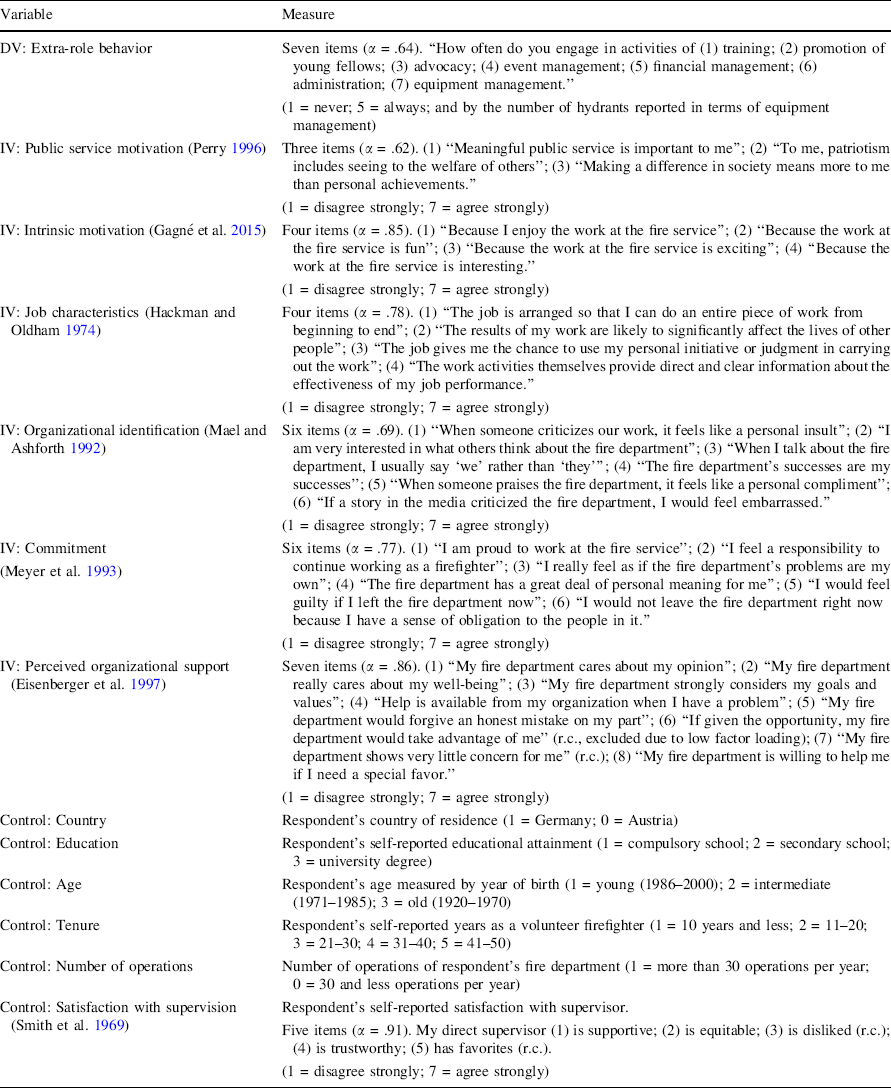

Appendix

See Table 4.

Table 4 Variables and measurement

Variable |

Measure |

|---|---|

DV: Extra-role behavior |

Seven items (α = .64). “How often do you engage in activities of (1) training; (2) promotion of young fellows; (3) advocacy; (4) event management; (5) financial management; (6) administration; (7) equipment management.” (1 = never; 5 = always; and by the number of hydrants reported in terms of equipment management) |

IV: Public service motivation (Perry Reference Perry1996) |

Three items (α = .62). (1) “Meaningful public service is important to me”; (2) “To me, patriotism includes seeing to the welfare of others”; (3) “Making a difference in society means more to me than personal achievements.” (1 = disagree strongly; 7 = agree strongly) |

IV: Intrinsic motivation (Gagné et al. Reference Gagné2015) |

Four items (α = .85). (1) “Because I enjoy the work at the fire service”; (2) “Because the work at the fire service is fun”; (3) “Because the work at the fire service is exciting”; (4) “Because the work at the fire service is interesting.” (1 = disagree strongly; 7 = agree strongly) |

IV: Job characteristics (Hackman and Oldham Reference Hackman and Oldham1974) |

Four items (α = .78). (1) “The job is arranged so that I can do an entire piece of work from beginning to end”; (2) “The results of my work are likely to significantly affect the lives of other people”; (3) “The job gives me the chance to use my personal initiative or judgment in carrying out the work”; (4) “The work activities themselves provide direct and clear information about the effectiveness of my job performance.” (1 = disagree strongly; 7 = agree strongly) |

IV: Organizational identification (Mael and Ashforth Reference Mael and Ashforth1992) |

Six items (α = .69). (1) “When someone criticizes our work, it feels like a personal insult”; (2) “I am very interested in what others think about the fire department”; (3) “When I talk about the fire department, I usually say ‘we’ rather than ‘they’”; (4) “The fire department’s successes are my successes”; (5) “When someone praises the fire department, it feels like a personal compliment”; (6) “If a story in the media criticized the fire department, I would feel embarrassed.” (1 = disagree strongly; 7 = agree strongly) |

IV: Commitment (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Allen and Smith1993) |

Six items (α = .77). (1) “I am proud to work at the fire service”; (2) “I feel a responsibility to continue working as a firefighter”; (3) “I really feel as if the fire department’s problems are my own”; (4) “The fire department has a great deal of personal meaning for me”; (5) “I would feel guilty if I left the fire department now”; (6) “I would not leave the fire department right now because I have a sense of obligation to the people in it.” (1 = disagree strongly; 7 = agree strongly) |

IV: Perceived organizational support (Eisenberger et al. Reference Eisenberger, Cummings, Armeli and Lynch1997) |

Seven items (α = .86). (1) “My fire department cares about my opinion”; (2) “My fire department really cares about my well-being”; (3) “My fire department strongly considers my goals and values”; (4) “Help is available from my organization when I have a problem”; (5) “My fire department would forgive an honest mistake on my part”; (6) “If given the opportunity, my fire department would take advantage of me” (r.c., excluded due to low factor loading); (7) “My fire department shows very little concern for me” (r.c.); (8) “My fire department is willing to help me if I need a special favor.” (1 = disagree strongly; 7 = agree strongly) |

Control: Country |

Respondent’s country of residence (1 = Germany; 0 = Austria) |

Control: Education |

Respondent’s self-reported educational attainment (1 = compulsory school; 2 = secondary school; 3 = university degree) |

Control: Age |

Respondent’s age measured by year of birth (1 = young (1986–2000); 2 = intermediate (1971–1985); 3 = old (1920–1970) |

Control: Tenure |

Respondent’s self-reported years as a volunteer firefighter (1 = 10 years and less; 2 = 11–20; 3 = 21–30; 4 = 31–40; 5 = 41–50) |

Control: Number of operations |

Number of operations of respondent’s fire department (1 = more than 30 operations per year; 0 = 30 and less operations per year) |

Control: Satisfaction with supervision (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Kendall and Hulin1969) |

Respondent’s self-reported satisfaction with supervisor. Five items (α = .91). My direct supervisor (1) is supportive; (2) is equitable; (3) is disliked (r.c.); (4) is trustworthy; (5) has favorites (r.c.). (1 = disagree strongly; 7 = agree strongly) |

DV dependent variable, IV independent variable, r.c. reversed coded