1. Introduction

In this study, we focus on reconstructing the plasma boundary, which is defined by the last closed flux surface (LCFS) of the confined plasma. The LCFS represents the transition between the closed magnetic field lines in the high-temperature, high-density confinement region of the plasma and the open field lines in the scrape-off layer of the plasma.

The position of the plasma boundary, as defined by the LCFS, is not directly measured during experiments. Instead, it is inferred through plasma equilibrium reconstruction using data collected from sensors installed in the tokamak. These calculations are performed by specialised equilibrium reconstruction codes, such as EFIT (Lao et al. Reference Lao, St. John, Stambaugh, Kellman and Pfeiffer1985), which is widely used for reconstructing equilibria in DIII-D discharges. In this work, we utilise EFIT data for training and evaluating machine learning (ML) models.

Although real-time EFIT solvers are now standard on many tokamaks, they often require a full set of calibrated magnetic diagnostics and device-specific tuning. Data-driven surrogate models offer a complementary advantage: once trained, they can deliver boundary estimates from a reduced diagnostic set and, when designed for sensor robustness, serve as a rapid fallback if individual diagnostics degrade or become temporarily unavailable.

There has been considerable progress in applying ML techniques to replace EFIT, most notably in the EFIT-AI project (Lao et al. Reference Lao2022; Madireddy et al. Reference Madireddy2024), which incorporates advanced methods and practices for reconstructing various plasma parameters, including the flux, toroidal current and the full magnetic field distribution. However, the majority of existing works rely on comprehensive magnetics datasets, including signals from probes and flux loops, as input features for plasma boundary or full magnetic field distribution reconstruction (Joung et al. Reference Joung, Kim, Kwak, Bak, Lee, Han, Kim, Lee, Kwon and Ghim2019; Wai, Boyer & Kolemen Reference Wai, Boyer and Kolemen2022; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Akçay, Bechtel Amara, Kruger, Lao, Liu, Madireddy and McClenaghan2024).

This reliance on a full set of magnetics data is common because it provides extensive constraints for plasma boundary reconstruction. Reducing the set of input parameters introduces additional challenges, as fewer constraints may lead to greater uncertainty in the reconstruction. Nevertheless, investigating models trained on limited diagnostic data is particularly relevant for data-limited environments, such as those anticipated in fusion power plants (FPP), where diagnostic capabilities are constrained by the presence of blankets and shielding.

In this work, we explore the feasibility of reconstructing the LCFS in the DIII-D tokamak using neural network (NN) models trained on reduced feature sets. What differentiates our approach is the minimal input data used to train the models. Specifically, we compare two models: one trained exclusively on coil currents and another incorporating coil currents, plasma current and loop voltage. This comparison illustrates the trade-offs between input feature complexity and reconstruction accuracy, highlighting the potential of ML algorithms to operate effectively in data-limited environments.

2. Dataset

The DIII-D discharge database encompasses a broad range of experimental data, including sensor measurements, EFIT equilibrium reconstructions, magnetic control system commands and plasma state information. These data capture diverse experimental conditions, configurations and control strategies. The data are recorded as high-resolution time series through an array of diagnostic systems installed in the tokamak, collecting key parameters such as magnetic fields, plasma temperature and density. While coil currents

![]() $\{I_k\}_{k=1}^{{{N_{\text{coils}}}}}$

, plasma current

$\{I_k\}_{k=1}^{{{N_{\text{coils}}}}}$

, plasma current

![]() ${I_{\text{p}}}$

and loop voltage

${I_{\text{p}}}$

and loop voltage

![]() ${V_{\text{loop}}}$

are measured during the discharge, the plasma geometry is automatically calculated post-shot using the EFIT equilibrium reconstruction code.

${V_{\text{loop}}}$

are measured during the discharge, the plasma geometry is automatically calculated post-shot using the EFIT equilibrium reconstruction code.

In this study, we consider the state of the plasma, which is defined by plasma shape, current and kinetic profiles, and the state of the tokamak, which we define by coil currents. For brevity, we will occasionally use the term ‘discharge state’ to refer to a state that describes both the plasma and the tokamak.

We employ NN models based on fully connected neural network (FCNN) architecture, trained on historical EFIT data. The initial dataset consisted of approximately 50 000 DIII-D discharges spanning 2004–2024, covering both positive and negative triangularities. The dataset was filtered to exclude discharges with missing EFIT equilibrium outputs, durations shorter than 1500 ms, or time gaps exceeding 100 ms.

The DIII-D database contains many duplicated shots originating from repeated experiments. To ensure unbiased evaluation, it is critical to prevent duplicates from simultaneously appearing in the training, validation or test sets. However, to our knowledge, no metadata exist that can reliably identify which shots belong to the same experiment or category, making duplicate identification challenging. To address this, we developed a data-driven method for detecting and removing duplicates. This approach involves two steps: first, each discharge is represented as a fixed-length sequence of discharge states; second, the discharges are clustered based on the similarity of these sequences. Using this method, we identified and removed approximately 30 % of the shots in the filtered dataset as duplicates, resulting in a final dataset of approximately 26 000 discharges and 3.5 million discharge states used for training and testing. The models are trained and evaluated on complete discharges, including ramp-up, flattop and ramp-down phases.

The DIII-D measurements are stored as time-series data, each typically sampled at its own temporal resolution. Although these series cover the same time interval, their discretisation rates differ. To align them on a common time base, we interpolated all measurements (i.e. coil currents,

![]() ${I_{\text{p}}}$

and

${I_{\text{p}}}$

and

![]() ${V_{\text{loop}}}$

) to match the timestamps of the plasma boundary time series for each discharge.

${V_{\text{loop}}}$

) to match the timestamps of the plasma boundary time series for each discharge.

As described earlier, the plasma boundary represents the outermost surface of the confined plasma and is typically defined as a two-dimensional curve. The DIII-D database provides a discretised version of this curve as a set of

![]() $(R, Z)$

points in the tokamak’s coordinate system for each timestamp in a discharge. Since the plasma boundaries from different discharges are described by varying numbers of points in the DIII-D database, we interpolated all boundaries to a fixed number of points using a temporary polar representation of the plasma shape. Specifically, we converted the

$(R, Z)$

points in the tokamak’s coordinate system for each timestamp in a discharge. Since the plasma boundaries from different discharges are described by varying numbers of points in the DIII-D database, we interpolated all boundaries to a fixed number of points using a temporary polar representation of the plasma shape. Specifically, we converted the

![]() $(R, Z)$

points to polar coordinates relative to the magnetic centre of the plasma. The magnetic axis coordinates

$(R, Z)$

points to polar coordinates relative to the magnetic centre of the plasma. The magnetic axis coordinates

![]() $(R_{\text{mag}}, Z_{\text{mag}})$

were taken from the EFIT equilibrium reconstruction provided in the DIII-D database at each timestamp, so the polar origin tracks the Shafranov shift dynamically. The boundary was then uniformly sampled at

$(R_{\text{mag}}, Z_{\text{mag}})$

were taken from the EFIT equilibrium reconstruction provided in the DIII-D database at each timestamp, so the polar origin tracks the Shafranov shift dynamically. The boundary was then uniformly sampled at

![]() $90$

polar angles to produce a fixed-size representation, and the sampled points were finally converted back to absolute

$90$

polar angles to produce a fixed-size representation, and the sampled points were finally converted back to absolute

![]() $(R, Z)$

vessel coordinates for each timestamp. These

$(R, Z)$

vessel coordinates for each timestamp. These

![]() $(R, Z)$

points serve as the regression targets.

$(R, Z)$

points serve as the regression targets.

The top and bottom triangularities (

![]() ${\delta _{\text{upper}}}$

and

${\delta _{\text{upper}}}$

and

![]() ${\delta _{\text{lower}}}$

) quantify how much the plasma boundary near the upper and lower regions deviates from an ideal ellipse, whereas the elongation (

${\delta _{\text{lower}}}$

) quantify how much the plasma boundary near the upper and lower regions deviates from an ideal ellipse, whereas the elongation (

![]() $\kappa$

) measures the degree of vertical stretching of that boundary. These parameters describe how much the plasma boundary deviates from an idealised elongated configuration and can be defined as

$\kappa$

) measures the degree of vertical stretching of that boundary. These parameters describe how much the plasma boundary deviates from an idealised elongated configuration and can be defined as

where

![]() ${{R_{\text{geo}}}} = {({{R_{\text{max}}}} + {{R_{\text{min}}}})}/{2}$

is the major radius of the plasma geometric centre,

${{R_{\text{geo}}}} = {({{R_{\text{max}}}} + {{R_{\text{min}}}})}/{2}$

is the major radius of the plasma geometric centre,

![]() ${R_{\text{upper}}}$

and

${R_{\text{upper}}}$

and

![]() ${R_{\text{lower}}}$

are the major radii of the highest and lowest points of the LCFS,

${R_{\text{lower}}}$

are the major radii of the highest and lowest points of the LCFS,

![]() $a = ({{{R_{\text{max}}}} - {{R_{\text{min}}}}})/{2}$

is the plasma minor radius and

$a = ({{{R_{\text{max}}}} - {{R_{\text{min}}}}})/{2}$

is the plasma minor radius and

![]() ${R_{\text{max}}}$

and

${R_{\text{max}}}$

and

![]() ${R_{\text{min}}}$

are the maximum and minimum values of the major radius along the LCFS.

${R_{\text{min}}}$

are the maximum and minimum values of the major radius along the LCFS.

The sign of

![]() ${\delta _{\text{upper}}}$

and

${\delta _{\text{upper}}}$

and

![]() ${\delta _{\text{lower}}}$

distinguishes between positive and negative triangularity regimes. A positive triangularity configuration (

${\delta _{\text{lower}}}$

distinguishes between positive and negative triangularity regimes. A positive triangularity configuration (

![]() ${{\delta _{\text{upper}}}} \gt 0, {{\delta _{\text{lower}}}} \gt 0$

) corresponds to a plasma shape where the boundary is indented inward at the top and bottom, resulting in a D-shaped cross-section, which is commonly utilised in tokamaks to enhance plasma stability and confinement properties (Urano et al. Reference Urano, Kamada, Shirai, Takizuka, Kubo, Hatae and Fukuda2001). Conversely, a negative triangularity configuration (

${{\delta _{\text{upper}}}} \gt 0, {{\delta _{\text{lower}}}} \gt 0$

) corresponds to a plasma shape where the boundary is indented inward at the top and bottom, resulting in a D-shaped cross-section, which is commonly utilised in tokamaks to enhance plasma stability and confinement properties (Urano et al. Reference Urano, Kamada, Shirai, Takizuka, Kubo, Hatae and Fukuda2001). Conversely, a negative triangularity configuration (

![]() ${{\delta _{\text{upper}}}} \lt 0, {{\delta _{\text{lower}}}} \lt 0$

) features outward-extending top and bottom regions, yielding a D-shaped cross-section. Recent studies suggest that negative triangularity plasmas may exhibit reduced turbulence and improved confinement under certain operational conditions (Austin et al. Reference Austin2019).

${{\delta _{\text{upper}}}} \lt 0, {{\delta _{\text{lower}}}} \lt 0$

) features outward-extending top and bottom regions, yielding a D-shaped cross-section. Recent studies suggest that negative triangularity plasmas may exhibit reduced turbulence and improved confinement under certain operational conditions (Austin et al. Reference Austin2019).

3. Models

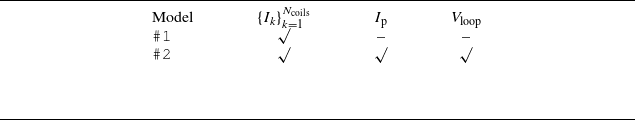

To investigate the feasibility of reconstructing the plasma boundary using a reduced set of input features, we compared the performance of two ML models trained on the same set of discharge states but with different input features (table 1). Each model’s task is to reconstruct the plasma boundary using the corresponding set of input features at the same timestamp. The models do not rely on information from prior states of the plasma or device and thus perform the same function as the EFIT code.

Table 1. Correspondence between models and the input feature sets they were trained on. Here,

![]() $k$

represents the magnetic coil index, and

$k$

represents the magnetic coil index, and

![]() ${{N_{\text{coils}}}} = 20$

in this work for DIII-D.

${{N_{\text{coils}}}} = 20$

in this work for DIII-D.

Model #1 was trained to reconstruct the plasma boundary using only the coil-current values as input. Model #2 extended the input feature set to include two additional parameters: the plasma current

![]() ${I_{\text{p}}}$

and the loop voltage

${I_{\text{p}}}$

and the loop voltage

![]() ${V_{\text{loop}}}$

.

${V_{\text{loop}}}$

.

The DIII-D tokamak has 18 shaping coils (F-coils) and 6 ohmic heating coils (E-coils). In this work, we use only two of the E-coils, ‘ECOILA’ and ‘ECOILB’, which together form the centre solenoid. The remaining four E-coils share the same power supply as these two and thus exhibit highly correlated values. As a result, we have a total of 20 coil-current values, denoted as

![]() $\{I_k\}_{k=1}^{20}$

, which form the input vector for model #1. The input for model #2 consists of 22 values,

$\{I_k\}_{k=1}^{20}$

, which form the input vector for model #1. The input for model #2 consists of 22 values,

![]() $\{I_k\}_{k=1}^{20} \cup \{{{I_{\text{p}}}}, {{V_{\text{loop}}}}\}$

.

$\{I_k\}_{k=1}^{20} \cup \{{{I_{\text{p}}}}, {{V_{\text{loop}}}}\}$

.

Both models predict the geometry of the plasma boundary as a vector of size

![]() ${{N_{\text{c}}}} = 2 \times {{N_{\text{p}}}}$

. This vector represents a flattened matrix of shape

${{N_{\text{c}}}} = 2 \times {{N_{\text{p}}}}$

. This vector represents a flattened matrix of shape

![]() $({{N_{\text{p}}}}, 2)$

, where

$({{N_{\text{p}}}}, 2)$

, where

![]() ${N_{\text{p}}}$

corresponds to the number of two-dimensional points describing the plasma boundary at a given timestamp, which is set to

${N_{\text{p}}}$

corresponds to the number of two-dimensional points describing the plasma boundary at a given timestamp, which is set to

![]() $90$

in our experiments.

$90$

in our experiments.

The models are designed to receive the state of a discharge at a specific moment in time and compute the corresponding plasma boundary for that moment. Consequently, the training dataset comprises individual discharge states and is represented as a matrix of shape

![]() $(N, D + {{N_{\text{c}}}})$

, where

$(N, D + {{N_{\text{c}}}})$

, where

![]() $N$

is the total number of discharge states,

$N$

is the total number of discharge states,

![]() $D = 20 \text{ or } 22$

corresponds to the dimensionality of the input feature space and

$D = 20 \text{ or } 22$

corresponds to the dimensionality of the input feature space and

![]() ${{N_{\text{c}}}} = 180$

represents the dimensionality of the plasma boundary vectors. Before being used for training, both the input features and the target outputs are standardised separately by subtracting their respective means and dividing by their standard deviations.

${{N_{\text{c}}}} = 180$

represents the dimensionality of the plasma boundary vectors. Before being used for training, both the input features and the target outputs are standardised separately by subtracting their respective means and dividing by their standard deviations.

Figure 1. Left: heatmap of the correlation matrix between dataset features (model inputs, left) and target plasma boundary points (model outputs, top). The left part of the matrix corresponds to the

![]() $R$

coordinates of the boundary points, the right part corresponds to the

$R$

coordinates of the boundary points, the right part corresponds to the

![]() $Z$

coordinates. For clarity, each boundary point is labelled by its polar angle (in degrees) relative to the plasma centre and the positive direction of the

$Z$

coordinates. For clarity, each boundary point is labelled by its polar angle (in degrees) relative to the plasma centre and the positive direction of the

![]() $R$

axis. Right: poloidal cross-section of the DIII-D magnet system shown for geometric reference.

$R$

axis. Right: poloidal cross-section of the DIII-D magnet system shown for geometric reference.

Figure 1 shows a correlation matrix between the dataset features (model inputs) and the target plasma boundary points (model outputs). The matrix highlights small but noticeable correlations, ranging from approximately

![]() $0.2$

to

$0.2$

to

![]() $0.4$

, between certain coil currents and specific boundary points (both

$0.4$

, between certain coil currents and specific boundary points (both

![]() $R$

and

$R$

and

![]() $Z$

coordinates), providing insights into how variations in input features correspond to changes in the plasma boundary.

$Z$

coordinates), providing insights into how variations in input features correspond to changes in the plasma boundary.

Both models share the same FCNN architecture, consisting of two hidden layers with 150 and 80 neurons, respectively. To stabilise training and prevent overfitting, we apply batch normalisation (Ioffe & Szegedy Reference Ioffe and Szegedy2015) and dropout (probability

![]() $0.2$

) (Srivastava et al. Reference Srivastava, Hinton, Krizhevsky, Sutskever and Salakhutdinov2014). Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) is used as the activation function.

$0.2$

) (Srivastava et al. Reference Srivastava, Hinton, Krizhevsky, Sutskever and Salakhutdinov2014). Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) is used as the activation function.

To train the models, we employed the mean squared error (MSE) loss function, which has demonstrated strong performance in predicting plasma parameters (Abbate, Conlin & Kolemen Reference Abbate, Conlin and Kolemen2021; Wan et al. Reference Wan, Bai, Yu, Yuan, Huang, Liu, Hu and Li2024)

\begin{align} \text{MSE Loss} = \frac {1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^N \left \|b_i - \hat {b}_i\right \|^2\text{,} \end{align}

\begin{align} \text{MSE Loss} = \frac {1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^N \left \|b_i - \hat {b}_i\right \|^2\text{,} \end{align}

where

![]() $b_i$

is the ground truth boundary vector,

$b_i$

is the ground truth boundary vector,

![]() $\hat {b}_i$

is the predicted boundary vector,

$\hat {b}_i$

is the predicted boundary vector,

![]() $i$

is the sample index and

$i$

is the sample index and

![]() $N$

is the size of the training dataset. We used a learning rate of

$N$

is the size of the training dataset. We used a learning rate of

![]() $1 {\times }10^{-4}$

and the Adam (Kingma & Ba Reference Kingma and Ba2014) optimiser for training.

$1 {\times }10^{-4}$

and the Adam (Kingma & Ba Reference Kingma and Ba2014) optimiser for training.

To prevent data leaks, we adopted a shape-based cross-validation approach. Discharge states were first divided into three main groups based on top and bottom triangularity; each group was then further subdivided into four subgroups according to median values. This process produced 12 distinct sets of plasma shapes. At each cross-validation stage, the training–validation set consisted of 11 of these groups, while the remaining group was used for testing (figure 2). The validation set at each step was drawn from states belonging to discharges in 2020, 2021 and 2022. To prevent overfitting, we balanced the number of states in each group by subsampling, ensuring that every plasma shape group contained the same number of states. As a result, the training–validation–test ratio was approximately 80–10–10 at each cross-validation stage.

Figure 2. Centre plot: distribution of plasma states in the training dataset based on top and bottom triangularity. All states are divided into three main groups, producing 12 subgroups for cross-validation. At each cross-validation stage, the training set is composed of data from 11 groups, while the remaining group is used for testing. The left and right plots show examples of plasma shapes with ‘negative–positive’ and ‘negative–negative’ triangularity, respectively, illustrating the models’ accuracy on previously unseen cases (orange – true boundary, blue – model #1 reconstruction, green – model #2).

4. Results

To evaluate model performance during cross-validation and on the test set, three metrics were used:

-

– Maximum point displacement (MXD) and mean point displacement (MND)

(4.1) \begin{align} \text{MXD} = \frac {1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^{N} \max _{j=1}^{{{N_{\text{p}}}}}\left \|p_{ij} - \hat {p}_{ij}\right \|,\end{align}

(4.2)

\begin{align} \text{MXD} = \frac {1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^{N} \max _{j=1}^{{{N_{\text{p}}}}}\left \|p_{ij} - \hat {p}_{ij}\right \|,\end{align}

(4.2) \begin{align} \text{MND} = \frac {1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^{N} \frac {1}{{{N_{\text{p}}}}} \sum _{j=1}^{{{N_{\text{p}}}}} \left \|p_{ij} - \hat {p}_{ij}\right \|,\end{align}

\begin{align} \text{MND} = \frac {1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^{N} \frac {1}{{{N_{\text{p}}}}} \sum _{j=1}^{{{N_{\text{p}}}}} \left \|p_{ij} - \hat {p}_{ij}\right \|,\end{align}

where

$p_{ij}$

and

$p_{ij}$

and

$\hat {p}_{ij}$

are the

$\hat {p}_{ij}$

are the

$j$

th true and predicted two-dimensional boundary points for the

$j$

th true and predicted two-dimensional boundary points for the

$i$

th sample,

$i$

th sample,

${N_{\text{p}}}$

is the number of boundary points and

${N_{\text{p}}}$

is the number of boundary points and

$N$

is the total number of samples. Hereafter, all MXD and MND values are reported in metres and calculated in the original scale of the quantities.

$N$

is the total number of samples. Hereafter, all MXD and MND values are reported in metres and calculated in the original scale of the quantities. -

– Coefficient of determination

$R^2$

(4.3)where

$R^2$

(4.3)where \begin{align} R^2 = \frac {\sum _{i=1}^{{{N_{\text{c}}}}}\left (V_i \boldsymbol{\cdot }R_i^2\right )}{\sum _{i=1}^{{{N_{\text{c}}}}} V_i}\text{,}\quad V_i = \frac {1}{N} \sum _{j=1}^{N} \left (y_{ij} - \overline {y_{i}}\right )^2\text{,}\quad R_i^2 = 1 - \frac {\sum _{j=1}^{N}\left (y_{ij} - \hat {y}_{ij}\right )^2}{\sum _{j=1}^{N}\left (y_{ij} - \overline {y_{i}}\right )^2}\text{,} \end{align}

\begin{align} R^2 = \frac {\sum _{i=1}^{{{N_{\text{c}}}}}\left (V_i \boldsymbol{\cdot }R_i^2\right )}{\sum _{i=1}^{{{N_{\text{c}}}}} V_i}\text{,}\quad V_i = \frac {1}{N} \sum _{j=1}^{N} \left (y_{ij} - \overline {y_{i}}\right )^2\text{,}\quad R_i^2 = 1 - \frac {\sum _{j=1}^{N}\left (y_{ij} - \hat {y}_{ij}\right )^2}{\sum _{j=1}^{N}\left (y_{ij} - \overline {y_{i}}\right )^2}\text{,} \end{align}

$R_i^2$

is the coefficient of determination for the

$R_i^2$

is the coefficient of determination for the

$i$

th network output (corresponding to the

$i$

th network output (corresponding to the

$R$

or

$R$

or

$Z$

coordinate of a boundary point),

$Z$

coordinate of a boundary point),

${{N_{\text{c}}}} = 180$

(as

${{N_{\text{c}}}} = 180$

(as

$90$

points are represented by both

$90$

points are represented by both

$R$

and

$R$

and

$Z$

coordinates),

$Z$

coordinates),

$y_{ij}$

and

$y_{ij}$

and

$\hat {y}_{ij}$

are the true and predicted values of the

$\hat {y}_{ij}$

are the true and predicted values of the

$i$

th coordinate for the

$i$

th coordinate for the

$j$

th sample,

$j$

th sample,

$\overline {y_i}$

is the mean true value of the

$\overline {y_i}$

is the mean true value of the

$i$

th coordinate,

$i$

th coordinate,

$N$

is the number of samples and

$N$

is the number of samples and

$V_i$

reflects variance in

$V_i$

reflects variance in

$y_i$

.

$y_i$

.

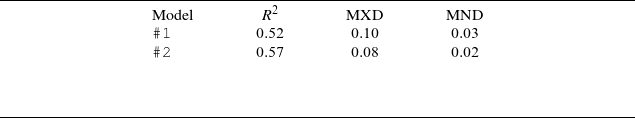

The results of cross-validation are presented in table 2, which summarises the performance of the two models across all splits. For each split, the testing set contained unseen plasma shapes, ensuring that the models were evaluated on data outside their training subsets. In our experiments, the trained models #1 and #2 achieved cross-validated

![]() $R^2$

scores of

$R^2$

scores of

![]() $0.52$

and

$0.52$

and

![]() $0.57$

respectively. Although these coefficients of determination indicate that the models capture some variability in the shape, they also indicate that a significant amount of the underlying relationship remains unexplained, in part due to the reduced set of features used. The metrics show that model #2, which incorporates coil currents,

$0.57$

respectively. Although these coefficients of determination indicate that the models capture some variability in the shape, they also indicate that a significant amount of the underlying relationship remains unexplained, in part due to the reduced set of features used. The metrics show that model #2, which incorporates coil currents,

![]() ${I_{\text{p}}}$

and

${I_{\text{p}}}$

and

![]() ${V_{\text{loop}}}$

, achieves higher accuracy compared with the coil-current-only model, highlighting the added value of including additional input features.

${V_{\text{loop}}}$

, achieves higher accuracy compared with the coil-current-only model, highlighting the added value of including additional input features.

Table 2. Performance of the models during cross-validation. The metric values are averaged across cross-validation splits.

Figure 3. Dynamics of the MSE loss during training of the model #2 for the training set (blue) and the validation set (orange).

The test subset included discharges conducted in 2024. To ensure that no internal plasma state is over- or under-represented in the final training and test datasets, we include histograms of key plasma parameters showing coverage across a wide range of values and consistency of their distributions between the training and test sets (figure 4). Similar to the cross-validation procedure, the validation set for the final models was drawn from states belonging to discharges in 2020, 2021 and 2022. To prevent overfitting and ensure accurate model evaluation, we balanced the number of states corresponding to different plasma shapes in the training and testing sets using a subsampling approach similar to that used for cross-validation. As a result, the training–validation–test ratio was approximately 75–10–15. The dynamics of the loss functions during the training of the model #2 is shown in figure 3.

Figure 4. Probability density histograms of key plasma parameters in the training and test sets. The toroidal field is evaluated at the magnetic axis. Counts are normalised by the total number of samples and the bin width, yielding an estimate of the probability density function (PDF) and facilitating comparison between datasets of different sizes.

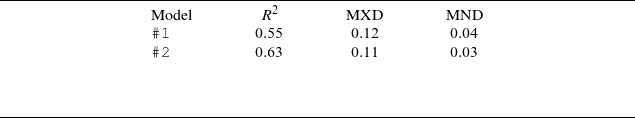

The performance of both models on the test subset is summarised in table 3. The results show that the models differ in performance by approximately

![]() $0.01$

m in favour of model #2 based on the MXD and MND metrics. Model #2, which used coil currents,

$0.01$

m in favour of model #2 based on the MXD and MND metrics. Model #2, which used coil currents,

![]() ${I_{\text{p}}}$

, and

${I_{\text{p}}}$

, and

![]() ${V_{\text{loop}}}$

as input, achieved an MND of

${V_{\text{loop}}}$

as input, achieved an MND of

![]() $0.03$

m, demonstrating the feasibility of reconstructing the LCFS with a reduced diagnostic set.

$0.03$

m, demonstrating the feasibility of reconstructing the LCFS with a reduced diagnostic set.

A more detailed assessment of the model #2 performance on the test subset can be obtained from the distribution of the

![]() $R^2$

metric across all plasma boundary points. As shown in figure 5,

$R^2$

metric across all plasma boundary points. As shown in figure 5,

![]() $R^2$

values are distributed unevenly across different regions of the plasma boundary. The most likely explanation for this behaviour is that, due to the use of a reduced set of input features, some regions of the plasma boundary exhibit very weak dependence on the available inputs. As a result, the model struggles to achieve significantly better performance than the mean model in these areas. This uneven relationship between the input features and different regions of the plasma boundary is also evident from the correlation matrix shown in figure 1.

$R^2$

values are distributed unevenly across different regions of the plasma boundary. The most likely explanation for this behaviour is that, due to the use of a reduced set of input features, some regions of the plasma boundary exhibit very weak dependence on the available inputs. As a result, the model struggles to achieve significantly better performance than the mean model in these areas. This uneven relationship between the input features and different regions of the plasma boundary is also evident from the correlation matrix shown in figure 1.

Table 3. Performance of the models on the test set.

The distribution of model errors across the entire test subset is shown in figure 6. To further evaluate model performance on the test subset, we plotted histograms of the MXD and MND metrics across all test samples in figure 7. These histograms show that the error distribution for model #2 is shifted towards lower values compared with the model #1.

Because identical coil-current vectors can correspond to different plasma states, the mapping from these inputs to boundary shape is inherently non-unique; Our coil-current-only model therefore reconstructs the shape most consistent with the control scenarios represented in the training data. This highlights the need for training datasets that capture the full diversity of control strategies and plasma states when applying ML methods to boundary reconstruction. The coil-current–only experiment was not intended to produce a fully deployable model for FPP; its purpose was to establish a quantitative baseline and a diagnostic gap analysis.

Figure 5. Distribution of the

![]() $R^2$

metric for the

$R^2$

metric for the

![]() $R$

and

$R$

and

![]() $Z$

coordinates of plasma boundary points for the model #2 on the test set. Plasma boundary points are labelled by their polar angle (in degrees) relative to the plasma centre and the positive direction of the

$Z$

coordinates of plasma boundary points for the model #2 on the test set. Plasma boundary points are labelled by their polar angle (in degrees) relative to the plasma centre and the positive direction of the

![]() $R$

axis.

$R$

axis.

Figure 6. Centre plot: distribution of the MXD metric across plasma states in the test subset (model #2). Examples of plasma shapes are shown for ‘positive–negative’ triangularity (left plot) and ‘positive–positive’ triangularity (right plot), with orange indicating the true boundary, blue – model #1 reconstruction, and green – model #2. These examples are taken from regions (highlighted in red) far from the majority of training samples (see figure 2) and represent challenging cases for the models (MXD values of

![]() $0.25$

–

$0.25$

–

![]() $0.3$

m).

$0.3$

m).

Standard DIII-D equilibrium reconstruction techniques and the plasma control system ensure accuracies of approximately

![]() $10^{-2}$

m required for experimental programs Eldon et al. (Reference Eldon, Hyatt, Covele, Eidietis, Guo, Humphreys, Moser, Sammuli and Walker2020). With the reduced 22-channel input set our model’s MND increases by only

$10^{-2}$

m required for experimental programs Eldon et al. (Reference Eldon, Hyatt, Covele, Eidietis, Guo, Humphreys, Moser, Sammuli and Walker2020). With the reduced 22-channel input set our model’s MND increases by only

![]() $0.01$

–

$0.01$

–

![]() $0.02$

m; but more importantly, the MXD distribution exhibits a long tail, with

$0.02$

m; but more importantly, the MXD distribution exhibits a long tail, with

![]() $0.1$

–

$0.1$

–

![]() $0.3$

m errors (figure 7). Such excursions are unacceptable for first-wall protection in an FPP environment, even though the underlying approach remains promising. Eliminating this high-error tail is therefore essential. One promising way to reduce these outliers is to embed coil-current and diagnostic measurements on a two-dimensional

$0.3$

m errors (figure 7). Such excursions are unacceptable for first-wall protection in an FPP environment, even though the underlying approach remains promising. Eliminating this high-error tail is therefore essential. One promising way to reduce these outliers is to embed coil-current and diagnostic measurements on a two-dimensional

![]() $(R, Z)$

grid, similar to EFIT-Prime (Madireddy et al. Reference Madireddy2024), and then compress this map with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or a convolutional encoder. Such a representation would link each measurement to its physical location, potentially reducing the angle-dependent errors seen in figure 5. We regard the present 22-channel model as a lower-bound benchmark; exploration of spatial embeddings, physics-based constraints, and additional FPP-relevant diagnostic sets is reserved for future work.

$(R, Z)$

grid, similar to EFIT-Prime (Madireddy et al. Reference Madireddy2024), and then compress this map with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or a convolutional encoder. Such a representation would link each measurement to its physical location, potentially reducing the angle-dependent errors seen in figure 5. We regard the present 22-channel model as a lower-bound benchmark; exploration of spatial embeddings, physics-based constraints, and additional FPP-relevant diagnostic sets is reserved for future work.

To assess suitability for real-time applications, we measured the model’s inference time in sequential mode, where samples are processed individually, consistent with real-time plasma control scenarios. On an AMD EPYC 7402P 24-Core Processor, the

![]() $95$

th percentile inference time was approximately

$95$

th percentile inference time was approximately

![]() $0.15$

milliseconds per sample.

$0.15$

milliseconds per sample.

Figure 7. Comparison of MXD (left) and MND (right) metric distributions for models #1 (blue) and #2 (green) on samples from the entire test subset. Histogram values are computed for individual samples. Vertical red lines indicate quantiles for model #2, with the top number representing the quantile and the bottom number showing the corresponding quantile value.

5. Conclusion and discussion

This study investigates the performance of reconstructing the plasma boundary using NN models trained on reduced input feature sets. Specifically, we compare two models: one relying solely on coil currents, and another that also incorporates plasma current and loop voltage. The coil-current-only model achieves a MND of 0.04 m on a held-out test set, while adding plasma current and loop voltage reduces the error to 0.03 m, demonstrating the impact of these features on reconstruction quality. The results also show that even with minimal diagnostics, it is feasible to reconstruct the plasma boundary, although the models capture only part of the plasma shape’s variability. These results are promising for future applications in FPP, where diagnostic capabilities will be constrained by the presence of blankets and shielding.

Future work will focus on evaluating the generalisability of these models to out-of-distribution data and further exploring their applicability to FPP environments. This includes extending the feature set with additional diagnostics, embedding spatial information for coils and sensors, exploring physics-based constraints and testing the models. Significant support for these studies can be provided by synthetic datasets that emulate the conditions expected in next-generation fusion devices. By generating datasets that capture a wide range of physical phenomena, it becomes possible to investigate how errors in shape reconstruction arise from different sources. This, in turn, can guide the selection of required diagnostics and inform the design of appropriate model architectures. However, such modelling efforts must evolve in parallel with the design of the FPP itself, with the ultimate goal of developing a digital model that can be calibrated on the actual device and continuously updated throughout its operational lifetime.

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation or favouring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof.

Editor Eleonora Viezzer thanks the referees for their advice in evaluating this article.

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Fusion Energy Sciences, using the DIII-D National Fusion Facility, a DOE Office of Science user facility, under Award(s) DE-FC02-04ER54698 and by Next Step Fusion funding. The authors would like to thank Dr. Cihan Akçay and Dr. Scott E. Kruger for helpful discussions and valuable insights, which greatly contributed to this work.

Declaration of interests

The authors report no conflict of interest.