Overview of poverty and nutrition situation in Ghana

The republic of Ghana is a relatively stable democracy in sub-Saharan Africa. The national population is estimated at 26 million with an annual growth rate just above 2 %( 1 ). Literacy rate within the youth population is approximately 70 and 60 % among males and females, respectively( 2 ). With a per capita gross domestic product of US$1652·00 in 2011( 3 ) the World Bank ranks Ghana as a lower-middle income country. During the past 10 years, Ghana has halved its poverty rate from 52 to 28 %( 4 ), and is recognised among the few sub-Saharan Africa countries that achieved the poverty reduction targets of the millennium development goals. Nevertheless, almost a quarter of Ghanaians still live below the poverty line( 4 ). Despite the growing economy and some improvements in social and human development outcomes, wide disparities exist in wealth distribution( 5 ). Regional disparities in poverty are most apparent, with the northern regions having poverty rates nearly twice that of regions in the South( 4 ).

Key health challenges facing Ghana include maternal and child undernutrition, maternal morbidity and mortality. Poverty and vulnerability have been identified as underlying causes of malnutrition in the National Nutrition Policy( 6 ). The most recent Demographic and Health Survey reported that 6 % of Ghanaian women of reproductive age are undernourished (BMI <18·5 kg/m2), with higher rates among those in the lowest wealth quintiles and in the three northern regions( 7 ). Micronutrient malnutrition is highly prevalent and persistent; 66 % of children aged 6–59 months are anaemic while 42 % of Ghanaian women aged 15–49 years are anaemic( 7 ). Iodine deficiency disorders are still prevalent and the majority of households (61 %) do not use adequately iodised salt in meal preparation( 7 ). Among Ghanaian children aged 5 years or younger, 19 % are stunted (too short for their age), 5 % are wasted (too thin for their height), and 11 % are underweight (too thin for their age). Although almost all children in Ghana (98 %) are breastfed at some point in their life, only 52 % of them are breastfed exclusively for 6 months( 7 ).

Desirous of addressing the unacceptably high rates of undernutrition among vulnerable Ghanaian populations, the Government of Ghana signed up with the global scaling up nutrition movement in 2011. The purpose was to stimulate scale up of both nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions. Subsequently a multi-stakeholder platform known as the scaling up nutrition cross-sectoral planning group was established in 2012. The cross-sectoral planning group was tasked to harmonise planning, implementation and monitoring of nutrition actions to achieve reduction in stunting. The scaling up nutrition cross-sectoral planning group convenes and coordinates government and non-government agencies to mainstream nutrition into existing policies and programmes linked either directly or indirectly with nutrition.

Defining and conceptualising social protection

The International Labour Organization defines social protection (SP) as security in the face of vulnerabilities and contingencies, including having access to health care( Reference Garcia and Gruat 8 ). This definition emphasises protection from chronic poverty, food and nutrition insecurity and other risks, which engenders vulnerability. To achieve this security, Handa & Park( Reference Handa and Park 9 ) point to a focus on interventions (by public, private and voluntary organisations, as well as informal networks) designed to support communities, households and individuals to prevent, manage and overcome risks and vulnerabilities. Devereux and Sabates-Wheeler( Reference Devereux and Sabates-Wheeler 10 )) offer an additional dimension, noting that all SP actions ought to be protective, preventative, promotional and transformative. Kaplan and Jones( Reference Kaplan and Jones 11 ) also argue for a rights-based approach in SP programming. The rights-based dimension is premised on the fundamental principles of the universal right to accountability, non-discrimination and participation as indicated by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 25), as well as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child also identifies (in Articles 20, 26 and 27) the right of all children to social security and insurance alongside an adequate standard of living. In the African context, Article 25 of the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child underscores the rights dimension of SP. The rights-based dimension therefore obligates governments to provide the necessary institutional capacity and accountability to provide SP to citizens.

A review of SP efforts across Africa reveals a diversity of programme focus, ranging from those which address vulnerabilities due to general chronic poverty( Reference Omilola and Kaniki 12 ), to those which focus on specific vulnerabilities, such as orphans of HIV/AIDS( Reference Greenblott 13 ), or food insecurity( Reference Slater, Holmes and Mathers 14 ). In Ghana, a less targeted conceptualisation of social protection, is adopted by the national SP strategy( 15 ). The national SP strategy is primarily designed to respond to risks and shocks in a rapid manner; and assures access to basic services such as health, education, water and energy for all sections of the population.

On the basis of the background provided, the present paper discusses the existing SP framework in Ghana and how it responds to nutrition vulnerabilities. Such a discussion helps to identify how SP interventions promote nutrition. It also helps to identify gaps in the present SP programming.

The evidence presented here draws on a desk review of available literature on SP in Ghana and elsewhere. The desk review included peer-reviewed journal articles, programme reports, evaluation reports, policy and guidance documents as well as programmatic document. The evidence from literature was supplemented by personal communications with key staff of national-level nutrition and SP institutions (Ghana School Feeding Programme, the Livelihood Empowerment against Poverty Programme (LEAP), the Ghana Social Opportunity Programme and the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS)).

Nutrition and social protection: the linkages

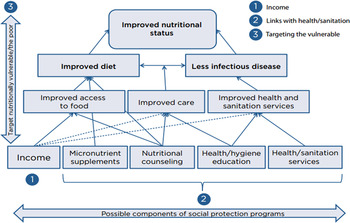

Over a decade of research has demonstrated the direct and indirect linkages between nutrition and SP( 16 – Reference Hewitt and Gillson 23 ). With consideration for the UNICEF framework on malnutrition, it has been shown that SP addresses vulnerabilities linked with loss of livelihood, shocks and stresses that result in food insecurity. Slater et al.( Reference Slater, Holmes and Mathers 14 ) examined the available evidence across a range of SP instruments with a focus on food security and practical programming experience. They show that across a range of both productivity-focused and protection-focused programmes, increased household income is spent on increasing the quantity and also the quality of food consumed( Reference Slater, Holmes and Mathers 14 ). They further show that some SP interventions also have an important role in mitigating the effects of shocks or seasonal stresses on household food insecurity, through smoothing consumption and/or income. Presented in Fig. 1 are the potential pathways by which SP programmes mitigate malnutrition.

Fig. 1. (Colour online) Pathways to impact: Social protection programmes' impact on nutrition. Source: Slater et al.( Reference Slater, Holmes and Mathers 14 ).

Earlier studies focusing on food transfers reported an association between SP actions and improved food consumption as well as nutritional outcomes. Ahmed( Reference Ahmed 24 ) and Jacoby( Reference Jacoby 25 ) respectively, reported that school snack programmes in Philippines and Bangladesh increased energy consumption of primary school children by 1255·2 kJ (300 kcal)/child per d, if parents did not reduce the amount of food served to children at home. In Uganda, school feeding reportedly led to the decline in the prevalence of mild anaemia among adolescent girls aged 10–13 years while a take-home ration component showed a decline in mild anaemia prevalence of adult women living in households that received these rations( Reference Alderman, Gilligan and Lehrer 26 ). Kazianga et al.( Reference Kazianga, de Walque and Alderman 27 ) report positive spill-over effects to other household members, most notably younger siblings. Other evaluations of cash transfers (CT) interventions reported improved dietary consumption. The Department for International Development’s review of CT programmes focused on hunger reduction and food insecurity found that, households receiving CT had significantly higher spending and consumption of food compared with non-transfer households( 28 ). In Malawi, Vincent and Cull( Reference Vincent and Cull 29 ) reported that 75 % of a CT was spent on groceries. In Zambia, CT significantly improved diets and nutritional status of beneficiaries: consumption of fats, proteins and vitamins-rich foods increased; percent of households living on one meal daily fell from 19 to 13 %( 30 ). de Groot et al. ( Reference de Groot, Palermo and Handa 31 ) provide a comprehensive overview of the impacts of CT programmes on the immediate and underlying determinants of child nutrition. They conclude that while an increasing number of studies have stressed the positive role of CT programmes in increasing resources for food, health and care, the evidence to date on the immediate determinants of child nutrition is mixed with regard to whether CT can positively impact growth-related outcomes among children, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa (see Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of impacts of social protection programmes on child nutrition, and immediate determinants and underlying determinants of child nutritional status

Source: de Groot et al.( Reference de Groot, Palermo and Handa 31 ).

Social protection in Ghana

In Ghana, SP interventions aimed at addressing the needs of the poor and vulnerable in society have been implemented since 1965. The first recorded intervention is the national social security law of 1965. Thereafter other SP programmes have included the national HIV/AIDS response programme in 2001, NHIS in 2003, the School Feeding Programme in 2003 and the LEAP initiative, a CT programme. Outlined in the next section are the flagship SP programmes in Ghana.

The National Health Insurance Scheme

The National Health Insurance Act, 2003 (Act 650) established the NHIS with the aim of increasing access to health care and improving the quality of basic health care services for all citizens, but especially for the poor and the vulnerable. Hitherto, majority of health care costs was paid from out of pocket by individuals and families, a system that was referred to as cash-and-carry. The benefit package covers about 95 % of diseases in Ghana such as malaria, cervical and breast cancer, surgical operations, physiotherapy, maternity care (antenatal, deliveries, postnatal), dental care, and eye care. Presently, NHIS is available countrywide through both public and private health care providers, including chemical stores and laboratories( Reference Witter and Garshong 32 ). Witter and Garshong( Reference Witter and Garshong 32 ) summarise the main features of the NHIS in Ghana (see Table 2).

Table 2. Main features of Ghana National Health Insurance Scheme

DHMIS, District Health Mutual Insurance Scheme; SSNIT, Social Security and National Insurance Trust.

Source: Summarised from Act 650 (2003) and LI 1809 (2004) by Witter and Garshong( Reference Witter and Garshong 32 ).

The Ghana School Feeding Programme

In September 2005, the government of Ghana in collaboration with her bilateral partners (The Dutch government) launched the School Feeding Programme following the African Union-New Partnership for Africa's Development model to use home-grown school feeding model. The basic concept of the Home Grown School Feeding Programme is to provide children in public basic schools one hot nutritious meal daily, using locally grown foodstuff. The programme has dual objectives: first to address acute hunger among young children in school, and secondly, to stimulate rural agricultural development. The long-term objective of the programme is to contribute to poverty reduction and food security in Ghana, then in line with Ghana's efforts towards realising the UN millennium development goals on hunger, poverty and primary education. The programme is administered by the National School Feeding programme and presently being overseen by the Ministry of Gender, Children and SP in collaboration with other government ministries including and Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development (the lead agency prior to August 2015), Food and Agriculture, Finance and Education Ministries. A number of non-governmental organisations and bilateral agencies provide technical support.

Livelihood empowerment against poverty

LEAP is a social CT programme which seeks to alleviate short-term poverty and encourage long-term human capital development( Reference Handa, Park and Darko 33 ). The programme was piloted in 1654 beneficiary households in twenty-one selected districts across the country. As at 2013, LEAP had extended to 70 191 beneficiary households across 100 districts nationwide as reported by Department of Social Welfare with an annual expenditure of US$20 million. Households with orphan or vulnerable child, elderly poor, or person with extreme disability are eligible to benefit under the programme( Reference Handa, Park and Darko 33 ). The receipt of the LEAP transfer is unconditional for people aged over 65 and people with disability. Launched in 2016, the ‘LEAP 1000 programme’ targets pregnant women and children aged less than 2 years in the northern and upper West regions of Ghana due to the high prevalence of stunting and malnutrition in these regions. The nutrition-sensitivity of LEAP, and the other SP programme presented earlier, their weaknesses and challenges are discussed later.

Nutrition sensitivity of the flagship social protection programmes in Ghana

The concepts and underlining motivators of the three major national level SP efforts (NHIS, School Feeding Programme and LEAP) in principle make them nutrition-sensitive. As indicated earlier, the School Feeding Programme aims to among others, provide children in public basic schools one hot nutritious meal each school day, using locally grown foodstuff. Its objectives of reducing hunger and malnutrition, boosting domestic food production and increasing school enrolment, attendance and retention; and the long-term goal of contributing to poverty reduction and food security in Ghana, are all nutrition promoting. Presently, the programme is implemented nationwide, covering about 4877 public basic schools in 216 districts with total enrolment of over 1 728 681 pupils in the country. The programme also employs 5365 caterers and engages 1170 farmer organisations. In addition to improving enrolment, school feeding programmes have a range of food and nutrition benefits for vulnerable families. For children, it has potential to diversify dietary intake, increase frequency of meals and improve food security of household. Quaye et al.( Reference Quaye, Essegbey and Frempong 34 ) aimed to deepen the present understanding of the emerging food sovereignty concept using a case study of the Ghana home-grown school feeding programme. Deploying a combination of quantitative and qualitative methodological approaches, they showed a significant improvement in household food access, one of many proxies for measuring food sovereignty. A comparative study by Danquah et al.( Reference Danquah, Amoah and Steiner-Asiedu 35 ) showed that participating schools served about the same meals using local foodstuff compared with schools not participating in the school feeding programme. Informed by their assessments of meal quantity and quality, the researchers called for fortification of the meals in order to improve their nutrient profile. Gelli et al.( Reference Gelli, Masset and Folson 36 ) are presently evaluating alternative school feeding models on nutrition, education, agriculture and other social outcomes in Ghana. An innovative capacity-building component is being integrated alongside the traditional Home Grown School Feeding Programme.

Presented in this review are CT programmes with proven impact on public health interventions( 20 , Reference Kazianga, de Walque and Alderman 27 ). Further, SP impact on prevention and management of domestic violence, and access to safe water and sanitation have been reported( Reference Jones and Holmes 37 ). In Ghana, Amuzu et al.( Reference Amuzu, Jones and Pereznieto 38 ) provide data on whether or not the LEAP CT Programme is making a difference in gendered risks, poverty and vulnerability in Ghana. Over time, the Ghanaian governments commitment to SP has reflected growing attention to sex issues. The Ghana National SP Strategy( 15 ) includes an explicit sex-sensitive approach, highlighting that women suffer disproportionately from extreme poverty in their role as caregivers, and this in turn is reflected in the LEAP programme design. Not only are caregivers of orphans and vulnerable children (predominantly women) a key target group, but also transfers are allocated to a reasonable balance of men and women aged 65 years and above. There is also specific attention paid to girls’ vulnerability to child labour, especially exploitative forms of domestic work. Overall, LEAP is making a useful contribution to costs faced by poor households for basic consumption and basic services, many of which are viewed as women's responsibilities( Reference Amuzu, Jones and Pereznieto 38 ). The data also suggest that LEAP is helping households to meet a range of practical sex needs, including covering the costs of essential food items, school supplies and the national health insurance card( Reference Amuzu, Jones and Pereznieto 38 ). Such efforts have nutrition promotion implications. The Government of Ghana in 2016 introduced LEAP 1000, an extension of LEAP. LEAP 1000 targets pregnant women and mothers with children under 2 years. Households enrolled into LEAP 1000 receive a bimonthly transfer of 60–100 Ghana cedi (US$15–24), based on the number of beneficiaries in the household. The evaluation of this initiative is presently underway( Reference de Groot 39 ).

The introduction of NHIS, has resulted in increasing levels of utilisation of health services. Witter and Garshong praises the increasing access to free out-patient, in-patient, dental and maternal health services( Reference Witter and Garshong 32 ). It is worth noting however, that the scheme is designed predominantly as a standalone health service provision programme with no nutrition-specific objectives. Although implementation of the NHIS has positive externalities on nutrition, its design, its stated objectives and modus operandi make it not sensitive to nutrition.

Challenges of social protection programming

Across the wide range of social assistance programming reviewed and presented in the present paper, various challenges including governance, administrative and financial capacity limitations, lack of coordination and human resource are recognised. Generally, social protection-oriented services are often overseen by under-resourced agencies severely limited in terms of human, administrative and technical capacities. In Ghana for example, Yuster( Reference Yuster 40 ) assessed the Department of Social Welfare as lacking administrative capacity to implement and oversee aspects of its SP programming mandate. These challenges are exacerbated by transparency, accountability issues and allegations of corruption in institutions managing social transfers. A much more mulish challenge is the lack of coordination within the range of agencies, ministries and other stakeholders tasked with designing and implementing SP programmes( Reference Kaplan and Jones 11 ). Similar barriers are posed by poor communication and awareness, raising between national level officials and local programme and service providers. More importantly, designing and coupling SP programmes with nutrition, and other cognate programmes remains a challenge. In Ghana for example, SP interventions are predominantly designed as standalone services and therefore are implemented independent of each other. Abebrese( Reference Abebrese 41 ) identified lack of alignment of the different social programmes like LEAP and the School Feeding Programme and effective integration of the marginalised groups as challenges. Lack of robust national systems for monitoring and evaluating delivery of SP programmes and their impacts on nutrition is another challenge.

Local evidence of the implementation of Ghana's CT programme (LEAP) has reported implementation and disbursement inconsistencies, including payment delays over long periods, and non-payment of all expected transfers( Reference Handa, Park and Darko 33 ). This results in poor predictability of cash receipt by families. Amuzu et al.( Reference Amuzu, Jones and Pereznieto 38 ) report on the sex sensitivity of the programme stressing the need to strengthen programme design features so as to enhance sex equality. Gelli et al.( Reference Gelli, Masset and Folson 36 ) report on the challenges in linking agriculture to other components of the Ghana School Feeding Programme. An evaluation of the programme, undertaken in 2012 identified the need for a more strategic approach in linking farmers to the programme( 42 ).

Opportunities for linking nutrition to social protection actions

Although the challenges described earlier of SP programming are real, there exist opportunities. Recent local and interactional actions provide real opportunities for cementing the relationship between nutrition and SP in Ghana. Internationally, the present high level of attention and recognition that nutrition enjoys from donors, national governments, civil society organisation, academia and the private sector provide a conducive environment for discourses and actual coupling of nutrition to SP actions. Some of the relevant international actions or commitments include the Lancet Series on Maternal and Child Nutrition 2008 and 2013( Reference Black, Allen and Bhutta 43 ), the Global Nutrition Report( 44 ), the Challenge Paper on Hunger and Malnutrition from the Third Copenhagen Consensus( Reference Hoddinott, Rosegrant and Torero 45 ), together with high-level meetings such as the Nutrition for Growth Summit in London, 2013 and the Second International Conference on Nutrition held in Rome, 2014. The global political support for the Sustainable Development Goals( 46 ) further provides an opportunity to advocate for the linkage of nutrition to SP actions and vice versa have provided consensus on the importance of alleviating malnutrition and the means to do so. Locally, Ghana is presently drafting a 40-year development plan with a major emphasis on nutrition; the national nutrition policy is being finalised. There is a real opportunity to have the recommendations delineated in the present paper carried in these national policy and strategic documents.

Conclusions

The present paper provides evidence in support of the argument that SP can be an effective tool for nutrition promotion. The evidence shows that SP schemes such as social transfers can support improved nutrition. However, designing and coupling SP programmes with nutrition programmes remains a challenge in Ghana. Local SP interventions are predominantly designed as standalone services and therefore are implemented independent of each other. There is presently the lack of robust national systems for monitoring and evaluating delivery, and nutrition-related impacts of social protection. To increase synergy between SP and nutrition, the present paper suggests the following recommendations. First, at the policy level, the paper recommends linking social protection, nutrition, agriculture and health policies so as to promote increased policy coherence and integrated actions. Second, the paper recommends the inclusion of nutrition as an explicit objective of every SP programme, as it is difficult to hold SP programmes accountable for nutritional impact if nutrition is not one of the designated programme objectives. Finally, social transfer sessions should contain nutrition and health education interventions.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Ernest Amoah Ampah, James Abugri, and Akua Tandoh for their inputs to the desk review and manuscript preparation.

Financial Support

The Issues Paper from which this article metamorphoses was commissioned by the National Development Planning Commission and funded by the UN Children's Fund.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Authorship

A. K. L. led in designing the study and in drafting the manuscript. R. N. O. A. and F.B. Z. contributed to design, drafting and editing of the manuscript; M. M. provided inputs during the project design and in drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.